Kinesiology, Physical Activity, Physical Education, and Sports through an Equity/Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) Lens: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Topic of Equity/Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI)

1.2. The Individual Concepts of Equity, Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion in Sport

1.3. The Individual Concepts of Equity, Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion in Kinesiology

1.4. The Individual Concepts of Equity, Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion in Physical Education

1.5. The Individual Concepts of Equity, Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion in Physical Activity

1.6. The Individual Concepts of Equity, Equality, Diversity and Inclusion in Sports, Kinesiology, Physical Education, and Physical Activity: The Case of Disabled People

The Issue of Ableism

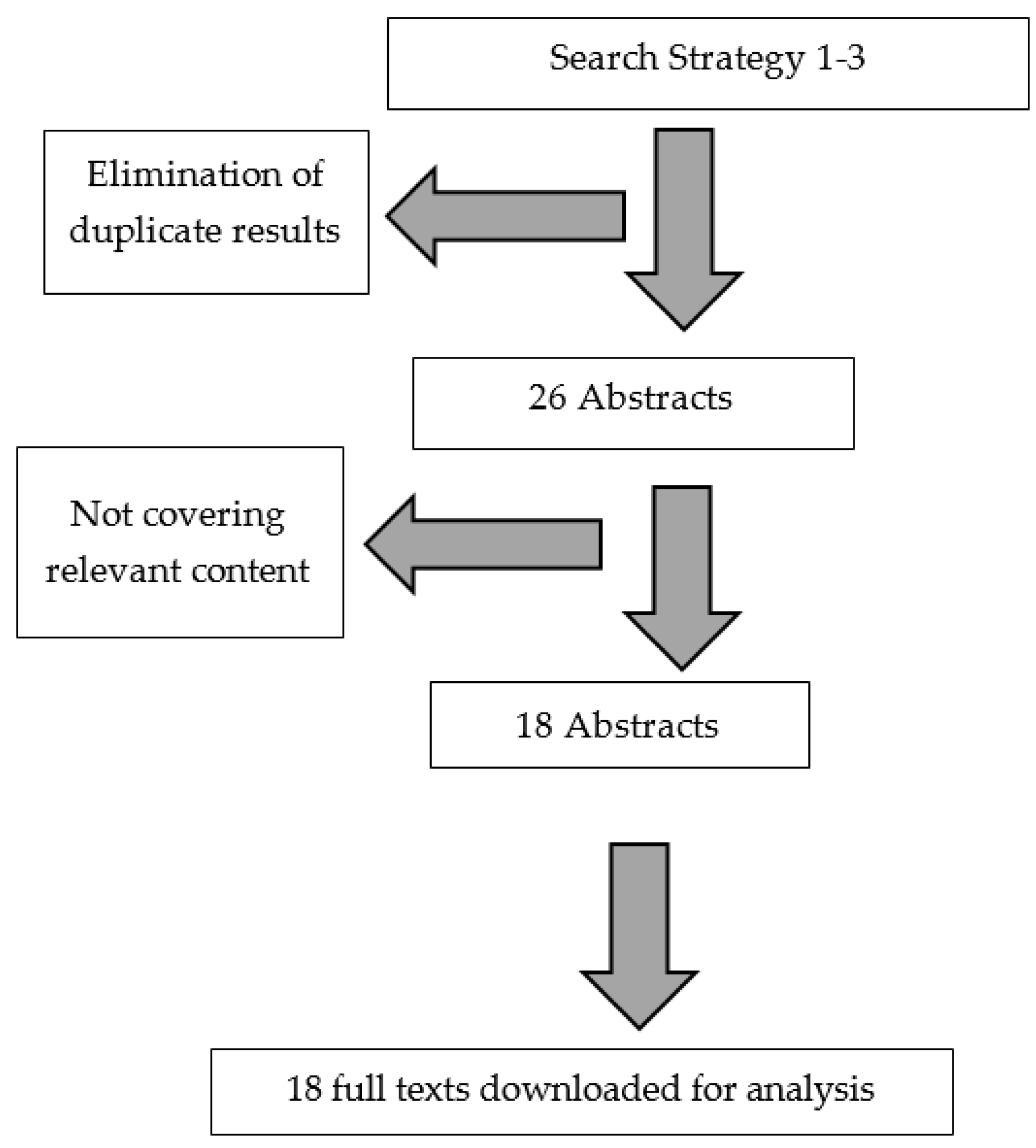

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Data Sources and Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Trustworthiness Measure

3. Results

- (a)

- The first one being academic/educational setting, but not university, which was classified as anything that is related to academics (but not specifically to a university) setting; for example, research conferences that are open to all fields of studies and careers, K to 12 education, and other academic organizations.

- (b)

- Non-academic settings, which primarily looked at sport facilities and organizations, recreational facilities and organizations, and general physical activity.

- (c)

- University setting, consisting of discussions around different university institutions and, specifically, different areas of the faculty of kinesiology.

3.1. Academic/Educational Setting

- -

- 0 results on physical education, in terms of EDI study results;

- -

- 0 results on sport, in terms of EDI curriculum and educators and mentor’s role in EDI;

- -

- 0 results on physical activity, in terms of EDI recommendations/EDI needs;

- -

- 0 results on physical activity, in terms of EDI curriculum and educators and mentor’s role in EDI;

- -

- 0 results on physical activity, in terms of EDI literacy/EDI narrative;

- -

- 0 results on physical activity, in terms of EDI study result;

- -

- 0 results on kinesiology, in terms of ALL the EDI-related themes.

3.1.1. Academic Setting and Physical Education

EDI Recommendation/EDI Needs

EDI Curriculum and Teacher/Educators/Mentors Role in EDI

3.1.2. Academic Setting and Sports

EDI Recommendation/EDI Needs

EDI Literacy/EDI Narrative

EDI Study Result

3.2. Non-Academic Setting

- -

- 0 results on physical education, in terms of all the EDI-related themes;

- -

- 0 results on sports, in terms of EDI curriculum and educator/mentor’s role in EDI;

- -

- 0 results on sports, in terms of EDI literacy/EDI narrative;

- -

- 0 results on physical activity, in terms of EDI curriculum and educators/mentor’s role in EDI;

- -

- 0 results on physical activity, in terms of EDI literacy/EDI narrative;

- -

- 0 results on physical activity, in terms of EDI study results;

- -

- 0 results on kinesiology, in terms of ALL the EDI-related themes.

3.2.1. Non-Academic Setting and Physical Activity

EDI Recommendation/EDI Needs

3.2.2. Non-Academic Setting and Sports

EDI Recommendation/EDI Needs

EDI Study Result

3.3. University Setting

- -

- 0 results on physical education, in terms of ALL the EDI-related themes;

- -

- 0 results on sports, in terms of EDI curriculum and educator/mentor’s role in EDI;

- -

- 0 results on sports, in terms of EDI literacy/EDI narrative;

- -

- 0 results on sports, in terms of EDI study result;

- -

- 0 results on physical activity, in terms of ALL the EDI-related themes;

- -

- 0 results on kinesiology, in terms of EDI curriculum and Educators/mentors role;

- -

- 0 results on kinesiology, in terms of EDI/EDI narrative.

3.3.1. University Setting and Sports

EDI Recommendation/EDI Needs

3.3.2. University Settings and Kinesiology

4. Discussion

4.1. The EDI Policy Frameworks

4.2. Individual EDI Terms in Sport, Physical Education, Physical Activity, and Kinesiology

4.3. The Issue of Ableism

Ableism beyond Disabled People

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wolbring, G.; Lillywhite, A. Equity/Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) in Universities: The Case of Disabled People. Societies 2021, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikus, J.; Grant-Smith, D.; Rieger, J. Cultural Probes as a Carefully Curated Research Design Approach to Elicit Older Adult Lived Experience. In Social Justice Research Methods for Doctoral Research; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 182–207. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, A. The Sovereignty of Critique. South Atl. Q. 2020, 119, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Klink, S. 3 Wellness Initiatives to Improve Your DEIB Recruiting and Retention Efforts. HR News Mag. 2021, 87, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- National Science Foundation. Geoscience Opportunities for Leadership in Diversity (NSF). Available online: https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=151210247&site=ehost-live (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Newswire, P.R. GXG Human Capital Practice Launches DEIB Growth Accelerator; a Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging Advisory Service, to Enable Sustainable Change and Growth for Organizations. Available online: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/gxg-human-capital-practice-launches-deib-growth-accelerator-a-diversity-equity-inclusion-and-belonging-advisory-service-to-enable-sustainable-change-and-growth-for-organizations-301341292.html (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Henry, F.; Dua, E.; Kobayashi, A.; James, C.; Li, P.; Ramos, H.; Smith, M.S. Race, racialization and Indigeneity in Canadian universities. Race Ethn. Educ. 2017, 20, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P. #MeToo in Surgery: Narratives by Women Surgeons. Narrat. Inq. Bioeth. 2019, 9, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, D. IDEAL ’19: Advancing Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Accessibility in Libraries and Archives, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA. Coll. Res. Libr. News 2019, 80, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlangu, V.P. Rethinking student admission and access in higher education through the lens of capabilities approach. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2020, 34, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zallio, M.; Clarkson, P.J. Inclusion, diversity, equity and accessibility in the built environment: A study of architectural design practice. Build. Environ. 2021, 206, 108352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, A.E.; Coe, I.R.; Gooden, E.A.; Tunde-Byass, M.; Wiley, R.E. Inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility: From organizational responsibility to leadership competency. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2021, 34, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotto-Santiago, S.; Mac, J.; Duncan, F.; Smith, J. “I Didn’t Know What to Say”: Responding to Racism, Discrimination, and Microaggressions with the OWTFD Approach. MedEdPORTAL J. Teach. Learn. Resour. 2020, 16, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayford, M. Performing arts in the service of others: The common good players and experiential learning in social justice theatre. In Diverse Pedagogical Approaches to Experiential Learning: Multidisciplinary Case Studies, Reflections, and Strategies; Palgrave McMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, R.B.; Benjamin, E.J. Diversity 4.0 in the cardiovascular health-care workforce. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 751–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afolabi, T. Theatre as Service … My Experience during the Global Pandemic in Canada. CTR 2021, 188, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.W.; Putnam, H.M.; Ainsworth, T.; Baum, J.K.; Bove, C.B.; Crosby, S.C.; Cote, I.M.; Duplouy, A.; Fulweiler, R.W.; Griffin, A.J.; et al. Promoting inclusive metrics of success and impact to dismantle a discriminatory reward system in science. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.C. Does intra-disciplinary historic preservation scholarship address the exigent issues of practice? Exploring the character and impact of preservation knowledge production in relation to critical heritage studies, equity, and social justice. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2021, 27, 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, T. Responsibilities of theorists: The case of communicative planning theory. Prog. Plan. 2009, 72, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goez, H.; Lai, H.; Rodger, J.; Brett-MacLean, P.; Hillier, T. The DISCuSS model: Creating connections between community and curriculum—A new lens for curricular development in support of social accountability. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, M.; Lerback, J.C.; St. Pierre, G.A.E. A Vision for a Diverse and Equitable Environment through the Lens of Inclusive Earth; Abstracts with Programs; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2020; Volume 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congress Advisory Committee on Equity Diversity Inclusion and Decolonization (AC-EDID) Canada. Igniting Change: Final Report and Recommendations. Available online: http://www.ideas-idees.ca/about/CAC-EDID-report (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Advance, H.E. Athena Swan Charter Encouraging and Recognising Commitment to Advancing Gender Equality. Available online: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/equality-charters/athena-swan-charter (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Science in Australia Gender Equity. Science in Australia Gender Equity. Available online: https://www.sciencegenderequity.org.au/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- AAAS. See Change with STEMM Equity Achievement. Available online: https://seachange.aaas.org/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- National Science Foundation. ADVANCE at a Glance. Available online: https://www.nsf.gov/crssprgm/advance/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Government of Canada. Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Dimensions Charter. Available online: http://www.nserc-crsng.gc.ca/NSERC-CRSNG/EDI-EDI/Dimensions-Charter_Dimensions-Charte_eng.asp (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Canadian Kinesiology Alliance. Inclusion Statrement. Available online: https://www.cka.ca/en/cka-inclusion (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- American Council on Exercise. Equity, Diversity and Inclusion in the Fitness Industry. Available online: https://www.acefitness.org/education-and-resources/professional/expert-articles/7918/equity-diversity-and-inclusion-in-the-fitness-industry/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Physical and Health Education Canada. Strategic Plan 2021–2024. Available online: https://phecanada.ca/sites/default/files/content/docs/phe-strategic%20-plan-2021-2024-final-24feb2021.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Youth Sport Trust. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion. Available online: https://www.youthsporttrust.org/about/equality-diversity-and-inclusion (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- US Ski and Snowboard. Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Action Plan. Available online: https://usskiandsnowboard.org/sites/default/files/files-resources/files/2021/DEI%20Action%20Plan%20July%2014%2C%202021_0.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Team USA. USA Diving Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. Available online: https://www.teamusa.org/usa-diving/diversity-equity-and-inclusion (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Office of Equity Diversity and Inclusion. Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion. Available online: https://www.ucalgary.ca/equity-diversity-inclusion (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Government of Canada. Equity, Diversity and Inclusion: Dimensions. Available online: https://www.nserc-crsng.gc.ca/NSERC-CRSNG/EDI-EDI/Dimensions_Dimensions_eng.asp (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Government of Canada. Best Practices in Equity, Diversity and Inclusion in Research: A Guide for Applicants to New Frontiers in Research Fund Competitions. Available online: https://www.sshrc-crsh.gc.ca/funding-financement/nfrf-fnfr/edi-eng.aspx (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- United States Government Printing Office. Intercollegiate Sports (Part 2). Hearing on Title IX Impact on Women’s Participation in Intercollegiate Athletics and Gender Equity before the Subcommittee on Commerce, Consumer Protection, and Competitiveness of the Committee on Energy and Commerce. House of Representatives, One Hundred Second Congress, Second Session. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED359091 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Soler, S.; Prat, M.; Puig, N.; Flintoff, A. Implementing Gender Equity Policies in a University Sport Organization: Competing Discourses from Enthusiasm to Resistance. Quest 2017, 69, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-Ching, W.; Yu-Hsien, T.; Keng-Yu, C.; Cheng-Ting, W.; Yi-Chia, L. The Shadow Report for the “Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)” with Topics on Gender Diversity Education, Sex Education, and Female Participation in Exercise and Sports. Chin. Educ. Soc. 2014, 47, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karr-Kidwell, P.J.; Sorenson, K. The Gender Equity Movement in Women’s Sports: A Literature Review and Recommendations. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED362471 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Congress of the U.S Washington D.C. House Committee on Energy Commerce. Intercollegiate Sports. Hearing on Title IX Impact on Women’s Participation in Intercollegiate Athletics and Gender Equity before the Subcommittee on Commerce, Consumer Protection, and Competitiveness of the Committee on Energy and Commerce. House of Representatives, One Hundred Third Congress, First Session. Available online: https://books.google.ca/books/about/Intercollegiate_Sports.html?id=Rcw0AAAAIAAJ&redir_esc=y (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Pollock, E.R.; Young, M.D.; Lubans, D.R.; Coffey, J.E.; Hansen, V.; Morgan, P.J. Understanding the impact of a teacher education course on attitudes towards gender equity in physical activity and sport: An exploratory mixed methods evaluation. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 105, 103421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.N. Excellence beyond athletics: Best practices for enhancing black male student athletes’ educational experiences and outcomes. Equity Excell. Educ. 2016, 49, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, M.R.; Whigham, S. Reflections on Redressing Racial Inequalities, When Teaching Race in the Sociology of Sport and Physical Education. In Doing Equity and Diversity for Success in Higher Education; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Nesseler, C.; Gomez-Gonzalez, C.; Gasparetto, T. Head coach tenure in college women’s soccer. Do race, gender, and career background matter? Sport Soc. 2021, 24, 972–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hylton, K. Race equality and sport networks: Social capital links. In Sport and Social Capital; Routledge Milton Park: Oxfordshire, UK, 2008; pp. 277–304. [Google Scholar]

- Westman, R.J. Investigating Equity: An Evaluation of the Relationship of the NCAA’s APR Metric on Similarly Resourced Historically Black and Predominantly White NCAA Division-I Colleges and Universities; Seton Hall University: South Orange, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Trussell, D.E.; Kovac, L.; Apgar, J. LGBTQ parents’ experiences of community youth sport: Change your forms, change your (hetero) norms. Sport Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melton, E.N.; MacCharles, J.D. Examining sport marketing through a rainbow lens. Sport Manag. Rev. 2021, 24, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krane, V.; Waldron, J.J. A renewed call to queer sport psychology. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2021, 33, 469–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, M. Straight Kits F/or Queer Bodies? An Inter-Textual Study of the Spatialization and Normalization of a Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer (LGBTQ) Soccer League Sport Space. Available online: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/29629 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Cunningham, G.B.; Wicker, P.; Walker, N.A. Gender and Racial Bias in Sport Organizations. Front. Sociol. 2021, 6, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.D.; Lucas, C.B.; Tibbetts, E.; Carter, L. Mandating intersectionality in sport psychology: Centering LGBTQ women of color athletes. In Feminist Applied Sport Psychology; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sauder, M.H.; DeLuca, J.R.; Mudrick, M.; Taylor, E. Conceptualization of diversity and inclusion: Tensions and contradictions in the sport management classroom. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2021, 29, 100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinan, C.J. The Presentation of Human Biological Diversity in Sport and Exercise Science Textbooks: The Example of “Race”. J. Sport Behav. 1994, 17, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Adair, D. Conformity, diversity, and difference in antipodean physical culture: The indelible influence of immigration, ethnicity, and race during the formative years of organized sport in Australia, c. 1788–1918. Immigr. Minorities 1998, 17, 14–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adair, D.; Taylor, T.; Darcy, S. Managing ethnocultural and ‘racial’ diversity in sport: Obstacles and opportunities. Sport Manag. Rev. 2010, 13, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cunningham, G.; Hussain, U. The case for LGBT diversity and inclusion in sport business. Sport Entertain. Rev. 2020, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, S.; Cunningham, G.B. The rainbow connection: A scoping review and introduction of a scholarly exchange on LGBTQ+ experiences in sport management. Sport Manag. Rev. 2021, 24, 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, G.B. Creating and sustaining gender diversity in sport organizations. Sex Roles 2008, 58, 136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Elling, A.; Hovden, J.; Knoppers, A. Gender Diversity in European Sport Governance; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, A. Sport, physical activity and urban Indigenous young people. Aust. Aborig. Stud. 2009, 2, 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.; Georgakis, S.; Wilson, R. Indigenous Games and Sports in the Australian National Curriculum: Educational Benefits and Opportunities? Ab-Orig. J. Indig. Stud. First Nations First Peoples’ Cult. 2018, 1, 195–213. [Google Scholar]

- Shehu, J. Sport for all in postcolony: Is there a place for indigenous games in physical education curriculum and research in Africa. Afr. Educ. Rev. 2004, 1, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapeta, J.; Stewart-Withers, R.; Palmer, F. Sport for Social Change with Aotearoa New Zealand Youth: Navigating the Theory–Practice Nexus through Indigenous Principles. J. Sport Manag. 2019, 33, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hodge, K.; Sharp, L.-A.; Heke, J.I. Sport Psychology Consulting with Indigenous Athletes: The Case of New Zealand Māori. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 2011, 5, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.; Forsyth, J. A Good Fight: How Indigenous Women Approach Boxing as a Mechanism for Social Change. J. Sport Soc. Iss. 2020, 45, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajwani, Y.; Giles, A.R.; Forde, S. Canadian National Sport Organizations’ Responses to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Calls to Action and Settler Silence. Sociol. Sport J. 2021, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takyi, S.A.; Amponsah, O.; Asibey, M.O.; Ayambire, R.A. An overview of Ghana’s educational system and its implication for educational equity. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2021, 24, 157–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J. Where Are All the Women? Diversity, the Sports Media, and Sports Journalism Education. Int. J. Organ. Divers. 2015, 14, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaston, L.; Blundell, M.; Fletcher, T. Gender diversity in sport leadership: An investigation of United States of America National Governing Bodies of Sport. Manag. Sport Leis. 2020, 25, 402–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartzell, A.C.; Dixon, M.A. A holistic perspective on women’s career pathways in athletics administration. J. Sport Manag. 2019, 33, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnick, M.J. Racial segregation by playing position in the English football league: Some preliminary observations. J. Sport Soc. Iss. 1988, 12, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, M.; Coleman, T.; Eys, M. Ethnic diversity and cohesion in interdependent youth sport contexts. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2021, 53, 101881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, N.; Chanteau, O.; Benoît, M.; Dumas, M.P.; Laurin-lamothe, A.; Parlavecchio, L.; Lester, C. Sports activities in a psychosocial perspective: Preliminary analysis of adolescent participation in sports challenges. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2014, 49, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dagkas, S. “Is social inclusion through PE, Sport and PA still a rhetoric?” Evaluating the relationship between physical education, sport and social inclusion. Educ. Rev. 2018, 70, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballas, J.; Buultjens, M.; Murphy, G.; Jackson, M. Elite-level athletes with physical impairments: Barriers and facilitators to sport participation. Disabil. Soc. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarmby, T.; Pickering, K. Physical activity and children in care: A scoping review of barriers, facilitators, and policy for disadvantaged youth. J. Phys. Act. Health 2016, 13, 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaarsma, E.A.; Dijkstra, P.U.; Geertzen, J.; Dekker, R. Barriers to and facilitators of sports participation for people with physical disabilities: A systematic review. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2014, 24, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meier, M. Gender Equity, Sport and Development; Swiss Academy for Development, 2000; Available online: https://www.sportanddev.org/sites/default/files/downloads/59__gender_equity__sport_and_development.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Sotiriadou, P.; de Haan, D. Women and leadership: Advancing gender equity policies in sport leadership through sport governance. Int. J. Sport Policy 2019, 11, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culver, D.M.; Kraft, E.; Din, C.; Cayer, I. The alberta women in sport leadership project: A social learning intervention for gender equity and leadership development. Women Sport Phys. Act. J. 2019, 27, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reifsteck, E.J. Feminist scholarship: Cross-disciplinary connections for cultivating a critical perspective in kinesiology. Quest 2014, 66, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.A.; Johnson, A.; Hardin, R.; Dzikus, L. Kinesiology students’ perceptions of ambivalent sexism. NASPA J. Women High. Educ. 2018, 11, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munt, G.C. Gender Bias in Textbooks in Selected Kinesiology Courses in Texas Colleges and Universities. Available online: https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc332557/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Ransdell, L.B.; Toevs, S.; White, J.; Lucas, S.; Perry, J.L.; Grosshans, O.; Boothe, D.; Andrews, S. Increasing the number of women administrators in kinesiology and beyond: A proposed application of the Transformational Leadership Model. Women Sport Phys. Act. J. 2008, 17, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, V.S.; Joseph, J.; Fusco, C. Lessons from Critical Race Theory: Outdoor Experiential Education and Whiteness in Kinesiology. J. Exp. Educ. 2021, 44, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachman, J.; Joseph, J.; Fusco, C. ‘What if what the professor knows is not diverse enough for us?’: Whiteness in Canadian kinesiology programs. Sport Educ. Soc. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, B.A. Supporting LGBTQ students in physical education: Changing the movement landscape. Quest 2014, 66, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochstetler, D.R. Identity Politics and Kinesiology. Int. J. Kinesiol. High. Educ. 2018, 2, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Kriger, D. Towards a Decolonizing Kinesiology Ethics Model. Quest 2021, 73, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culp, B. Social justice and the future of higher education kinesiology. Quest 2016, 68, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzarito, L. Ways of seeing the body in kinesiology: A case for visual methodologies. Quest 2010, 62, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M.; Meaney, K.; Martinez, M. See, reflect, and act: Using equity audits to enhance student success. Kinesiol. Rev. 2020, 9, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, J.A. A Review of Research and Organizational Efforts for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Kinesiology. Int. J. Kinesiol. High. Educ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.; Hodge, S.R.; Frank, A.M.; Vaughn, M. Academic administrators’ beliefs about diversity. Quest 2019, 71, 66–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGiacinto, K. Diversifying kinesiology: Untapped potential of historically Black colleges and universities. Quest 2014, 66, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClain, Z.; Bridges, D.; Bridges, E. Mentoring in higher education: Women, diversity and kinesiology. Chron. Kinesiol. Phys. Educ. High. Educ. 2014, 25, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K.L. Teaching for gender equity in physical education: A review of the literature. Women Sport Phys. Act. J. 2003, 12, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, S. Gender equality and opportunities in physical education and sport for women in China. In Women and Sport in Asia; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, M.; Boyd, K. Cracks in the narrative: Black and Latinx pre-service PE teachers in predominantly white PETE programs. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaughey, C.; Fletcher, T. Pre-service teachers’ experiences of learning to teach LGBTQ students in health and physical education. Rev. Phéneps/PHEnex J. 2020, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Landi, D.; Flory, S.B.; Safron, C.; Marttinen, R. LGBTQ Research in physical education: A rising tide? Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2020, 25, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flintoff, A.; Fitzgerald, H.; Scraton, S. The challenges of intersectionality: Researching difference in physical education. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 2008, 18, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thorjussen, I.M.; Sisjord, M.K. Inclusion and exclusion in multi-ethnic physical education: An intersectional perspective. Curric. Stud. Health Phys. Educ. 2020, 11, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dagkas, S. Problematizing social justice in health pedagogy and youth sport: Intersectionality of race, ethnicity, and class. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2016, 87, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, S.R.; Lieberman, L.J.; Murata, N.M. Essentials of Teaching Adapted Physical Education: Diversity, Culture, and Inclusion; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tripp, A.; Rizzo, T.L.; Webbert, L. Inclusion in physical education: Changing the culture. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2007, 78, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, D.; Jeanes, R.; O’Connor, J.; Alfrey, L. Re-theorising inclusion and reframing inclusive practice in physical education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2018, 22, 1062–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lleixà, T.; Nieva, C. The social inclusion of immigrant girls in and through physical education. Perceptions and decisions of physical education teachers. Sport Educ. Soc. 2018, 25, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagkas, S. Exploring teaching practices in physical education with culturally diverse classes: A cross-cultural study. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2007, 30, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Rossi, T. Diversity, Difference and Social Justice in Physical Education: Challenges and Strategies in a Translocated World; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, S.; Raab, A.; Höger, B.; Diketmüller, R. ‘Same, same, but different?!’ Investigating diversity issues in the current Austrian National Curriculum for Physical Education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariana, A.; Neagu, N.E.; Szabo, D.A. The Impact of Educational Policies in High Schools with a Sports Profile. Rev. Rom. Pentru Educ. Multidimens. 2021, 13, 177–194. [Google Scholar]

- Whatman, S.L.; Singh, P. Constructing health and physical education curriculum for indigenous girls in a remote Australian community. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2015, 20, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, G. Culturally responsive pedagogy and the renaissance of a Maori dimension in physical education: Te reo kori as cultural taonga. N. Z. Phys. Educ. 2000, 33, 42–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sharyn, H. The co-opting of “hauora” into curricula. Curric. Matters 2011, 7, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, D.D.; Halas, J.M. The wages of whiteness: Confronting the nature of ivory tower racism and the implications for physical education. Sport Educ. Soc. 2013, 18, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina, R.; Santana, A.; Montesdeoca, R.; Roldan, A. Improving self-efficacy towards inclusion in in-service physical education teachers: A comparison between insular and peninsular regions in Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valencia-Peris, A.; Mínguez-Alfaro, P.; Martos-García, D. Pre-service physical education teacher education: A view from attention to diversity. Retos 2019, 40, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukavina, P.; Langdon, J.; Greenleaf, C.; Jenkins, J.; Diversity Attitude Associations in Pre-Service Physical Education Teachers. JTRM Kinesiol. 2019. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1203187 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Brooks, D.D.; Althouse, R. The legacy of Brown: Commodification of the African American student-athlete? In Reversing Field: Examining Commercialization, Labor, Gender, and Race in 21st Century Sports Law; West Virginia University Press, West Virginia University: Morgantown, WV, USA, 2010; pp. 301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, M.B.; Cunningham, G. Examining the associations of perceived community racism with self-reported physical activity levels and health among older racial minority adults. J. Phys. Act. Health 2013, 10, 932–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y. Understanding the Challenges of Pursuing Physical Activity. Phys. Health Educ. J. 2009, 75, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, E.R.; Burton, E.T.; Cadieux, A.; Getzoff, E.; Santos, M.; Ward, W.; Beck, A.R. Addressing Structural Racism Is Critical for Ameliorating the Childhood Obesity Epidemic in Black Youth. Child. Obes. 2022, 18, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flory, S.B.; Landi, D. Equity and diversity in health, physical activity, and education: Connecting the past, mapping the present, and exploring the future. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2020, 25, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abichahine, H.; Veenstra, G. Inter-categorical intersectionality and leisure-based physical activity in Canada. Health Promot. Int. 2017, 32, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, R. An intersectional analysis to explaining a lack of physical activity among middle class black women. Sociol. Compass 2014, 8, 780–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrick, S.S.; Duncan, L.R. A qualitative exploration of LGBTQ+ and intersecting identities within physical activity contexts. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2018, 40, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, H.; Jung, E.; Jodoin, K.; Du, X.; Airton, L.; Lee, E.-Y. Operationalization of intersectionality in physical activity and sport research: A systematic scoping review. SSM-Popul. Health 2021, 14, 100808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löllgen, H. Importance and evidence of regular physical activity for prevention and treatment of diseases. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 2013, 138, 2253–2259. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack Porter, K.M.; Prochnow, T.; Mahoney, P.; Delgado, H.; Bridges Hamilton, C.N.; Wilkins, E.; Umstattd Meyer, M.R. Transforming city streets to promote physical activity and health equity. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 1475–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekelman, T.A.; Sauder, K.A.; Rockette-Wagner, B.; Glueck, D.H.; Dabelea, D. Sociodemographic Predictors of Adherence to National Diet and Physical Activity Guidelines at Age 5 Years: The Healthy Start Study. Am. J. Health Promot. 2021, 35, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, S.N.; Lindsey, I. Gendered trends in young people’s participation in active lifestyles: The need for a gender-neutral narrative. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2020, 26, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272722/9789241514187-eng.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Azzarito, L. Re-thinking disability and adapted physical education: An intersectionality perspective. In Routledge handbook of Adapted Physical Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 252–265. [Google Scholar]

- Haegele, J.A.; Yessick, A.; Zhu, X. Females with visual impairments in physical education: Exploring the intersection between disability and gender identities. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2018, 89, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, H.; Jobling, A.; Kirk, D. Valuing the voices of young disabled people: Exploring experience of physical education and sport. Eur. J. Phys. Educ. 2003, 8, 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutzler, Y.; Meier, S.; Reuker, S.; Zitomer, M. Attitudes and self-efficacy of physical education teachers toward inclusion of children with disabilities: A narrative review of international literature. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2019, 24, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, B.A.; Weatherford, G.M. Embodied identities: Using kinesiology programming methods to diminish the hegemony of the normal. Quest 2013, 65, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, C.; Haegele, J.A.; Pérez-Torralba, A. ‘My perspective has changed on an entire group of people’: Undergraduate students’ experiences with the Paralympic Skill Lab. Sport Educ. Soc. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricoy-Cano, A.J.; Hernández-Fernández, A.; Barros-Camargo, C.D. The Educational Inclusion in Physical Education, Design and Validation of the EF-IDAN2019 Questionnaire. Available online: https://rua.ua.es/dspace/bitstream/10045/97111/6/JHSE_2020_15-3_16.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Richardson, E.V.; Barber, L. A Dilemma of Disability Sport: Paralympic Ideology of ‘Legacy’ and Inclusive Physical Education in the United Kingdom. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Emma-Richardson-9/research (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Bulger, S.; Jones, E.M.; Taliaferro, A.R.; Wayda, V. If you build it, they will come (or not): Going the distance in teacher candidate recruitment. Quest 2015, 67, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.; Mesch, J. A global perspective on disparity of gender and disability for deaf female athletes. Sport Soc. 2018, 21, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, R.C.; Huntley, T.D.; Cushion, C.J.; Culver, D. Infusing disability into coach education and development: A critical review and agenda for change. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2021, 27, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carty, C.; van der Ploeg, H.P.; Biddle, S.J.; Bull, F.; Willumsen, J.; Lee, L.; Kamenov, K.; Milton, K. The first global physical activity and sedentary behavior guidelines for people living with disability. J. Phys. Act. Health 2021, 18, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, M.; Ruin, S. Forgotten bodies—An examination of physical education from the perspective of ableism. Sport Soc. 2018, 21, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndt, A.; Kissinger, D.B.; Messerole, M.; Noble, J.; Dinkel, D. Attitudinal beliefs towards individuals with disabilities at a metropolitan university: Insights and implications for kinesiology professionals. J. Kinesiol. Wellness 2020, 9, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, D.D.; Harrison, L.; Norris, M.; Norwood, D. Why we should care about diversity in kinesiology. Kinesiol. Rev. 2013, 2, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison Jr, L.; Azzarito, L.; Hodge, S. Social Justice in Kinesiology, Health, and Disability. Quest 2021, 73, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbring, G. Why NBIC? Why Human Performance Enhancement? Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2008, 21, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbring, G. The Politics of Ableism. Development 2008, 51, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbring, G.; Deloria, R.; Lillywhite, A.; Villamil, V. Ability Expectation and Ableism Peace. Peace Rev. 2020, 31, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbring, G. Ability Expectation and Ableism Glossary. Available online: https://wolbring.wordpress.com/ability-expectationableism-glossary/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Campbell, F.K. Contours of Ableism the Production of Disability and Abledness; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, F.K. Stalking ableism: Using disability to expose ‘abled’ narcissism. In Disability and Social Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 212–230. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, F.K. Refusing able (ness): A preliminary conversation about ableism. M/C J. 2008, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F.K. Precision ableism: A studies in ableism approach to developing histories of disability and abledment. Rethinking History 2019, 23, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodley, D. Disability studies: An Interdisciplinary Introduction; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Goodley, D.; Lawthom, R.; Liddiard, K.; Runswick-Cole, K. Provocations for critical disability studies. Disabil. Soc. 2019, 34, 972–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wolbring, G. Ability Expectation and Ableism Literature. Available online: https://wolbring.wordpress.com/ability-expectationableism-literature/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Goodley, D. Dis/Ability Studies: Theorising Disablism and Ableism; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Goodley, D.; Runswick-Cole, K. Becoming dishuman: Thinking about the human through dis/ability. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2016, 37, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodley, D.; Lawthom, R. Critical disability studies, Brexit and Trump: A time of neoliberal–ableism. Rethink. Hist. 2019, 23, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campbell, F.K. Ableism as transformative practice. In Rethinking Anti-Discriminatory and Anti-Oppressive Theories for Social Work Practice; Cocker, C., Letchfield, T.H., Eds.; Palgrave: London, UK, 2014; pp. 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, F.K. Exploring internalized ableism using critical race theory. Disabil. Soc. 2008, 23, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anthony, J.N., II; Bentley, J.; Duncan, J.M. (Eds.) Earth, Animal, and Disability Liberation: The Rise of the Eco-Ability Movement; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Eco-Ability Facebook Group Members. Eco-Ability: Animal, Earth and Disability Liberation. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/ecoability/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Bentley, J.K.; Conrad, S.; Hurley, S.; Lisitza, A.; Lupinacci, J.; Lupinacci, M.W.; Parson, S.; Pellow, D.; Roberts-Cady, S.; Wolbring, G. The Intersectionality of Critical Animal, Disability, and Environmental Studies: Toward Eco-Ability, Justice, and Liberation; Lexington Books: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nocella II, A.J. Defining Eco-ability. In Disability Studies and the Environmental Humanities; Ray, S.J., Sibara, J., Eds.; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2017; pp. 141–168. [Google Scholar]

- Wolbring, G.; Lisitza, A. Justice Among Humans, Animals and the Environment: Investigated Through an Ability Studies, Eco-Ableism, and Eco-Ability Lens. In Weaving Nature, Animals and Disability for Eco-Ability: The Intersectionality of Critical Animal, Disability and Environmental Studies; Nocella, A.J., George, A.E., Schatz, J.L., Eds.; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2017; pp. 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, B.; Primack, A.J. Driving toward disability rhetorics: Narrative, crip theory, and eco-ability in Mad Max: Fury Road. Crit. Stud. Media Commun. 2017, 34, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbring, G.; Ghai, A. Interrogating the impact of scientific and technological development on disabled children in India and beyond. Disabil. Glob. South 2015, 2, 667–685. [Google Scholar]

- Kattari, S.K. Examining Ableism in Higher Education through Social Dominance Theory and Social Learning Theory. Innov. High. Educ. 2015, 40, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbring, G. Ableism and Favoritism for Abilities Governance, Ethics and Studies: New Tools for Nanoscale and Nanoscale enabled Science and Technology Governance. In The Yearbook of Nanotechnology in Society, Vol. II: The Challenges of Equity and Equality; Cozzens, S.E., Wetmore, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Liasidou, A. Intersectional understandings of disability and implications for a social justice reform agenda in education policy and practice. Disabil. Soc. 2013, 28, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, A.; Shifrer, D. Race and Disability: From Analogy to Intersectionality. Sociol. Race Ethn. 2018, 5, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderston, S. Victimized again? Intersectionality and injustice in disabled women’s lives after hate crime and rape. In Gendered Perspectives on Conflict and Violence: Part A; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2013; pp. 17–51. [Google Scholar]

- Whitesel, J. Intersections of Multiple Oppressions: Racism, Sizeism, Ableism, and the “Illimitable Etceteras” in Encounters with Law Enforcement. Sociol. Forum 2017, 32, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbring, G. Violence and Abuse through an Ability Studies Lens. Indian J. Crit. Disabil. Stud. 2020, 1, 41–67. [Google Scholar]

- Culver, D.; Shaikh, M.; Alexander, D.; Duarte, T.; Sljuka, V.; Parrott, L.; Wrona, D.; Fournier, K. Gender Equity in Disability Sport: A Rapid Scoping Review of Literature. Available online: https://ruor.uottawa.ca/handle/10393/42217 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Narasaki-Jara, M.; Carmona, C.E.; Stillwell, B.; Onofre, R.; Brolsma, D.J.; Buenavista, T.L. Exploring ableism in kinesiology curriculum through kinesiology students’ experience: A phenomenological study. Int. J. Kinesiol. High. Educ. 2020, 5, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara, M. Reconsidering Ability: Kinesiology Students’ Attitudes and Perceptions of People with Disabilities. Available online: https://scholarworks.csun.edu/handle/10211.3/205747 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Morimoto, L.S. Teaching as transgression: The meta-autoethnography of a fat, disabled, brown kinesiology professor. In Feminist Applied Sport Psychology; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-M.; Singh, G.; Wright, E.M. Using the Transtheoretical Model to Promote Behavior Change for Social Justice in Kinesiology. J. Sport Psychol. Action 2020, 12, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, S.; Cooper, J.N.; Kluch, Y. Allyship as activism: Advancing social change in global sport through transformational allyship. Eur. J. Sport Soc. 2021, 18, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannitsopoulou, S.J. Uncovering Discourses Surrounding (in) Equity in Canadian University Sport and Recreation: A Critical Policy Analysis. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/a531b022b4396340c8b3d6691078f1ed/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Sandford, R.; Beckett, A.; Giulianotti, R. Sport, disability and (inclusive) education: Critical insights and understandings from the Playdagogy programme. Sport Educ. Soc. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, D.L.; Rossow-Kimball, B.; Connolly, M. Students’ experiences of paraeducator support in inclusive physical education: Helping or hindering? Sport Educ. Soc. 2021, 27, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, P.D.; Silva, C.F. Cripping the Dis § abled Body: Doing the Posthuman Tango in, through and around Sport. Somatechnics 2021, 11, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.; Simon, M.; Maher, A. Critical pedagogies for community building: Challenging ableism in higher education physical education in the United States. Teach. High. Educ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.; Hill, J. ‘I had to pop a wheelie and pay extra attention in order not to fall:’ Embodied experiences of two wheelchair tennis athletes transgressing ableist and gendered norms in disability sport and university spaces. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2021, 13, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brittain, I.; Biscaia, R.; Gérard, S. Ableism as a regulator of social practice and disabled peoples’ self-determination to participate in sport and physical activity. Leis. Stud. 2020, 39, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storr, R.; Jeanes, R.; Spaaij, R.; Farquharson, K. “That’s where the dollars are”: Understanding why community sports volunteers engage with intellectual disability as a form of diversity. Manag. Sport Leis. 2021, 26, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, N.; Misener, L.; Howe, P.D. All for one and one for all? Integration in high-performance sport. Manag. Sport Leis. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Drey, N.; Gould, D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 1386–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wolbring, G. Auditing the ‘Social’ of Quantum Technologies: A Scoping Review. Societies 2022, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edling, S.; Simmie, G. Democracy and emancipation in teacher education: A summative content analysis of teacher educators’ democratic assignment expressed in policies for Teacher Education in Sweden and Ireland between 2000–2010. Citizsh. Soc. Econ. Educ. 2017, 17, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. In Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology; Teo, T., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1947–1952. [Google Scholar]

- Downe-Wamboldt, B. Content analysis: Method, applications, and issues. Health Care Women Int. 1992, 13, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenton, A. Strategies for Ensuring Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research Projects. Educ. Inf. 2004, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baxter, P.; Jack, S. Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual. Rep. 2008, 13, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; SAGE Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W.; Philpot, R.; Gerdin, G.; Schenker, K.; Linnér, S.; Larsson, L.; Mordal Moen, K.; Westlie, K. School HPE: Its mandate, responsibility and role in educating for social cohesion. Sport Educ. Soc. 2021, 26, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pittman, J.; Severino, L.; DeCarlo-Tecce, M.J.; Kiosoglous, C. An action research case study: Digital equity and educational inclusion during an emergent COVID-19 divide. J. Multicult. Educ. 2021, 15, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton-Fisette, J.L.; Sutherland, S. Time to SHAPE Up: Developing policies, standards and practices that are socially just. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2020, 25, 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.N.; Nwadike, A.; Macaulay, C. A Critical Race Theory Analysis of Big-Time College Sports: Implications for Culturally Responsive and Race-Conscious Sport Leadership. J. Issues Intercoll. Athl. 2017, 10, 204–233. [Google Scholar]

- French, M.T.; Cardinal, B.J. Content Analysis of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion in the Recreational Sports Journal, 2005–2019. Recreat. Sports J. 2021, 45, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culp, B. Everyone Matters: Eliminating Dehumanizing Practices in Physical Education. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2020, 92, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxel Bliven, K.C. Our Commitment to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. J. Sport Rehab. 2020, 29, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, B.; Pringle, J.K.; Giddings, L.S. Reflections from EDI conferences: Consistency and change. Equal. Divers. Incl. 2013, 32, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legg, E.; Karner, E. Development of a model of diversity, equity and inclusion for sport volunteers: An examination of the experiences of diverse volunteers for a national sport governing body. Sport Educ. Soc. 2021, 26, 966–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.Z.; Santos Silva, K.R.; Vasquez, V. Women and the country of football: Intersections of gender, class, and race in Brazil. Movimento 2021, 27, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, S.; Riches, L. Racism and homophobia in English football: The equality act, positive action and the limits of law. Int. J. Discrim. Law 2016, 16, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coletti, J.T.; Allan, V.; Martin, L.J. Reading between the Lines: Gender Stereotypes in Children’s Sport-Based Books. Women Sport Phys. Act. J. 2021, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.N.; Newton, A.C.I.; Klein, M.; Jolly, S. A Call for Culturally Responsive Transformational Leadership in College Sport: An Anti-ism Approach for Achieving Equity and Inclusion. Front. Sociol. 2020, 5, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillywhite, A.; Wolbring, G. Undergraduate disabled students as knowledge producers including researchers: A missed topic in academic literature. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lillywhite, A.; Wolbring, G. Undergraduate Disabled Students as Knowledge Producers Including Researchers: Perspectives of Disabled Students. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbring, G. Ability Privilege: A needed addition to privilege studies. J. Crit. Anim. Stud. 2014, 12, 118–141. [Google Scholar]

- Wolbring, G. Obsolescence and body technologies Obsolescencia y tecnologías del cuerpo. Dilemata Int. J. Appl. Ethics 2010, 2, 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Table 37-10-0169-01 Unfair Treatment, Discrimination or Harassment among Postsecondary Faculty and Researchers. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3710016901 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Wolbring, G. Auditing the Impact of Neuro-Advancements on Health Equity. J. Neurol. Res. 2021. online first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strategy | Sources Used | First Search |

|---|---|---|

| Strategy 1 | Scopus/EBSCO-Host | ABS (“Athena SWAN” OR “See change with STEMM Equity Achievement” OR “Dimensions: equity, diversity and inclusion” OR “Science in Australia Gender Equity” OR “NSF ADVANCE” OR “equity, diversity and inclusion” OR “equality, diversity and inclusion” OR “diversity, equity and inclusion” OR “diversity, equality and inclusion”) AND ABS (“Kinesiology” OR “physical education” OR “physical activit*” OR “sport*”) |

| Strategy 2 | Scopus/EBSCO-Host | ABS (“Belonging, Dignity, and Justice” OR “Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Belonging” OR “diversity, Dignity, and Inclusion” OR “Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Accessibility” OR “Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion” OR “Inclusion, Diversity, Equity and Accessibility” OR “Inclusion, Diversity, Equity and Accountability” OR “Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Decolonization”) AND ABS (“kinesiology” OR “physical education” OR “physical activit*” OR “sport*”) |

| Strategy 3a | Scopus/EBSCO-Host | ABS (“equity” AND “diversity” AND “inclusion”) AND ABS (“kinesiology” OR “physical education” OR “physical activit*” OR “sport*”) |

| Strategy 3b | Scopus/EBSCO-Host | ABS (“equality” AND “diversity” AND “inclusion”) AND ABS (“kinesiology” OR “physical education” OR “physical activit*” OR “sport*”) |

| Area of Coverage | Degree of Coverage | EDI-Related Theme | EDI-Related Equity Deserving Groups Mentioned | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic/educational Setting | Physical Education | EDI recommendation/EDI needs | Women | 0 |

| Disabled People | 1 | |||

| LGBTQ2S+ | 0 | |||

| Racialized Minorities | 3 | |||

| Indigenous Peoples | 0 | |||

| No group | 8 | |||

| EDI Curriculum and Educators and Mentors role in EDI | Women | 0 | ||

| Disabled People | 0 | |||

| LGBTQ2S+ | 0 | |||

| Racialized Minorities | 1 | |||

| Indigenous Peoples | 0 | |||

| No group | 8 | |||

| EDI Literacy/EDI Narrative | Women | 0 | ||

| Disabled People | 0 | |||

| LGBTQ2S+ | 0 | |||

| Racialized Minorities | 0 | |||

| Indigenous Peoples | 0 | |||

| No group | 2 |

| Area of Coverage | Degree of Coverage | EDI-Related Theme | EDI-Related Equity Deserving Groups Mentioned | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic/educational Setting | Sports | EDI recommendation/EDI needs | Women | 0 |

| Disabled People | 0 | |||

| LGBTQ2S+ | 0 | |||

| Racialized Minorities | 0 | |||

| Indigenous Peoples | 0 | |||

| No group | 3 | |||

| EDI literacy/EDI narrative | Women | 0 | ||

| Disabled People | 0 | |||

| LGBTQ2S+ | 0 | |||

| Racialized Minorities | 0 | |||

| Indigenous Peoples | 0 | |||

| No group | 1 | |||

| EDI study result | Women | 2 | ||

| Disabled People | 1 | |||

| LGBTQ2S+ | 1 | |||

| Racialized Minorities | 3 | |||

| Indigenous Peoples | 0 | |||

| No groups | 3 |

| Area of Coverage | Degree of Coverage | EDI-Related Theme | EDI-Related Equity Deserving Groups Mentioned | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-academic setting | Physical activity | EDI recommendation/EDI needs | Women | 0 |

| Disabled People | 0 | |||

| LGBTQ2S+ | 0 | |||

| Racialized Minorities | 0 | |||

| Indigenous Peoples | 0 | |||

| No group | 1 |

| Area of Coverage | Degree of Coverage | EDI-Related Theme | EDI-Related Equity Deserving Groups Mentioned | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-academic setting | Sports | EDI recommendation/EDI needs | Women | 1 |

| Disabled people | 0 | |||

| LGBTQ2S+ | 0 | |||

| Racialized Minorities | 3 | |||

| Indigenous Peoples | 0 | |||

| No group | 2 | |||

| EDI study result | Women | 3 | ||

| Disabled People | 0 | |||

| LGBTQ2S+ | 4 | |||

| Racialized Minorities | 2 | |||

| Indigenous Peoples | 0 | |||

| No groups | 0 |

| Area of Coverage | Degree of Coverage | EDI-Related Theme | EDI-Related Equity Deserving Groups Mentioned | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| University Setting | Sports | EDI recommendation/EDI needs | Women | 0 |

| Disabled people | 0 | |||

| LGBTQ2S+ | 0 | |||

| Racialized Minorities | 0 | |||

| Indigenous Peoples | 0 | |||

| No group | 4 |

| Area of Coverage | Degree of Coverage | EDI-Related Theme | EDI-Related Equity Deserving Groups Mentioned | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| University Settings | Kinesiology | EDI recommendation/EDI needs | Women | 0 |

| Disabled People | 0 | |||

| LGBTQ2S+ | 0 | |||

| Racialized Minorities | 0 | |||

| Indigenous Peoples | 0 | |||

| No groups | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arora, K.; Wolbring, G. Kinesiology, Physical Activity, Physical Education, and Sports through an Equity/Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) Lens: A Scoping Review. Sports 2022, 10, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports10040055

Arora K, Wolbring G. Kinesiology, Physical Activity, Physical Education, and Sports through an Equity/Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) Lens: A Scoping Review. Sports. 2022; 10(4):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports10040055

Chicago/Turabian StyleArora, Khushi, and Gregor Wolbring. 2022. "Kinesiology, Physical Activity, Physical Education, and Sports through an Equity/Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) Lens: A Scoping Review" Sports 10, no. 4: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports10040055

APA StyleArora, K., & Wolbring, G. (2022). Kinesiology, Physical Activity, Physical Education, and Sports through an Equity/Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) Lens: A Scoping Review. Sports, 10(4), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports10040055