Direct and Indirect Effects of Youth Sports Participation on Emotional Intelligence, Self-Esteem, and Life Satisfaction

Abstract

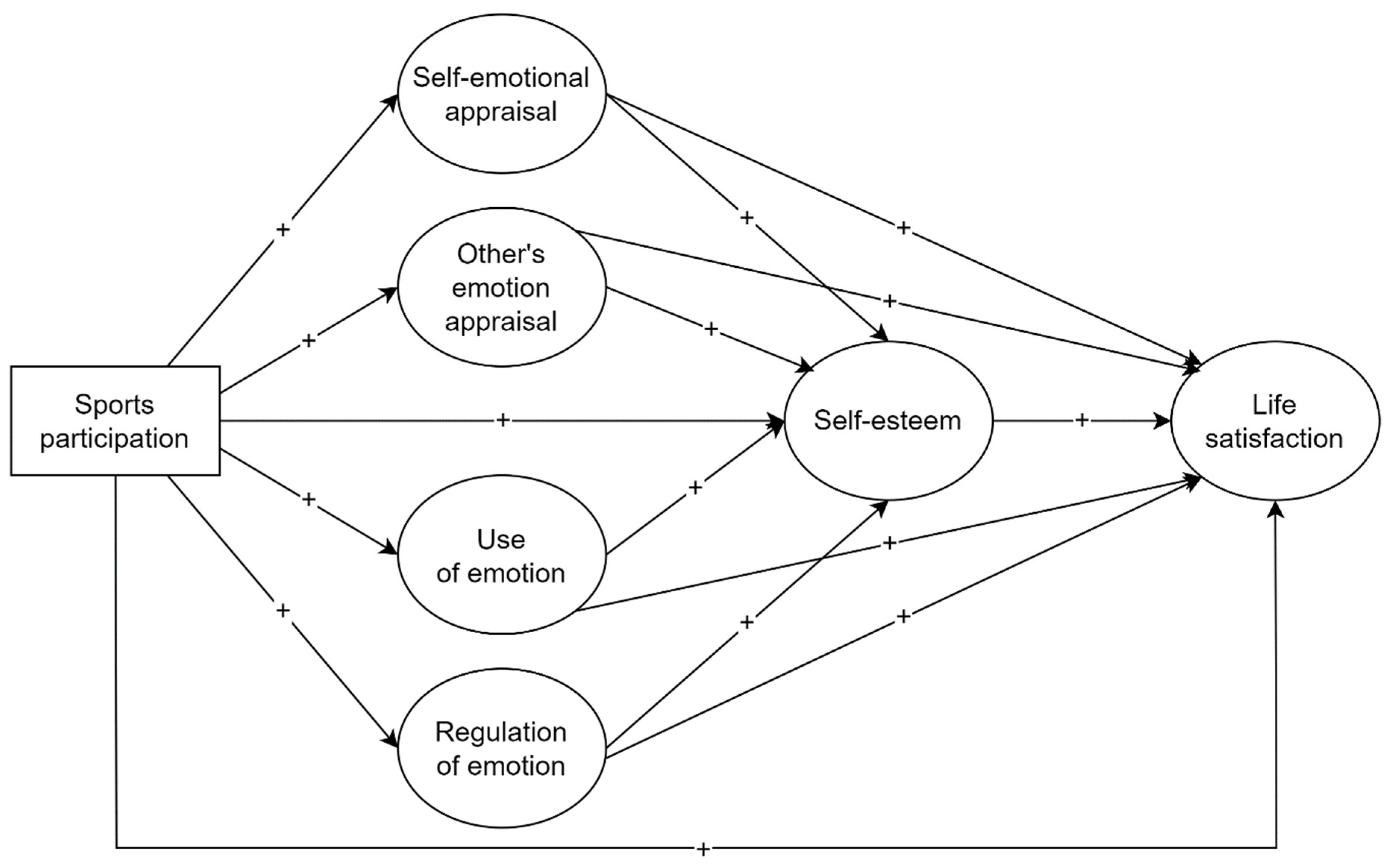

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Emotional Intelligence

2.2.2. Self-Esteem

2.2.3. Life Satisfaction

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and Correlational Analyses

3.2. Measurement Model

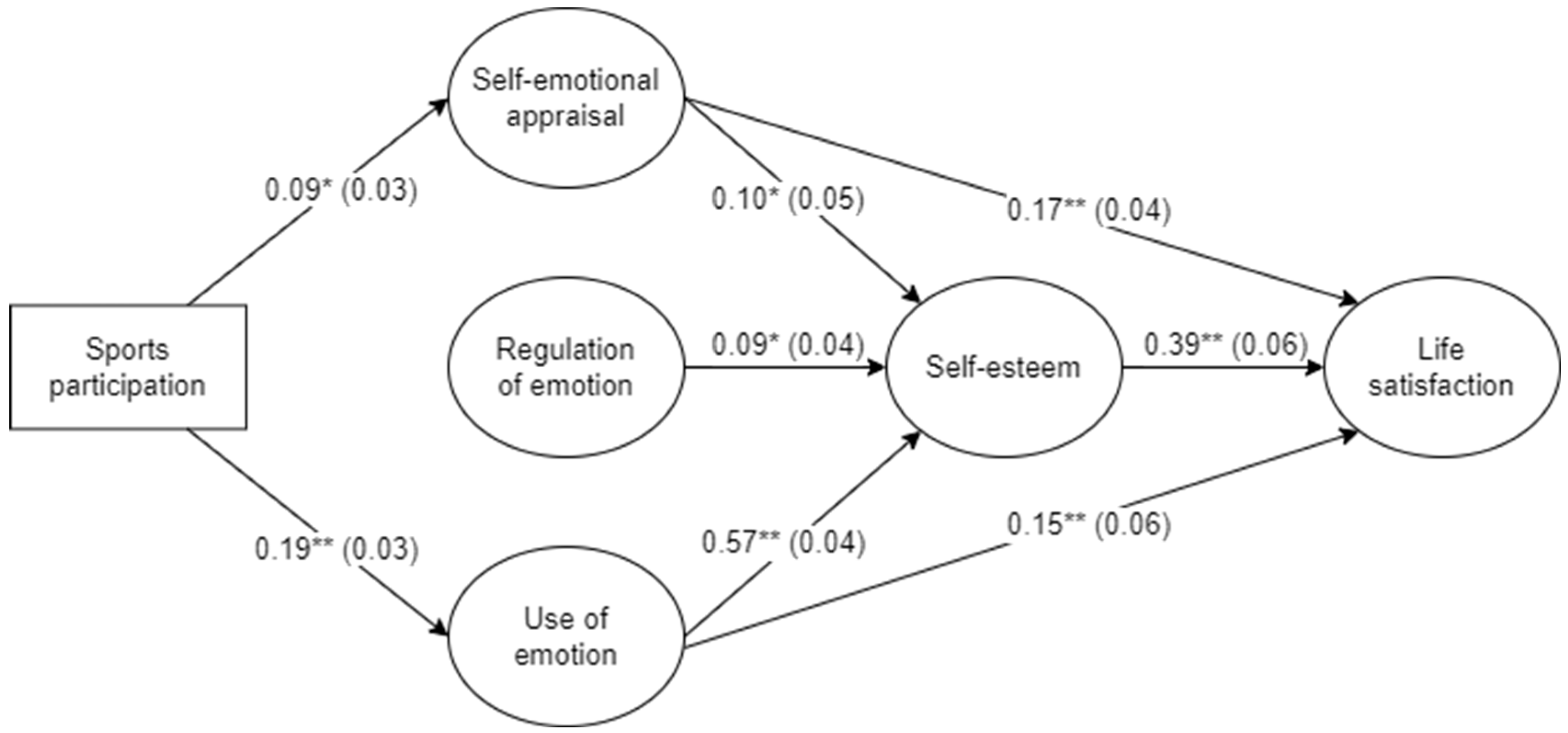

3.3. Structural Model

3.4. Indirect Effects

3.5. Effects of Sport Type on Emotional Intelligence, Self-Esteem, and Life Satisfaction

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Sports Participation on Emotional Intelligence, Self-Esteem, and Life Satisfaction

4.2. Effects of Sport Type on Emotional Intelligence, Self-Esteem, and Life Satisfaction

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.E.; Borghese, M.M.; Carson, V.; Chaput, J.-P.; Janssen, I.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Pate, R.R.; Connor Gorber, S.; Kho, M.E.; et al. Systematic Review of the Relationships between Objectively Measured Physical Activity and Health Indicators in School-Aged Children and Youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, S197–S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.Y.; Han, L.H.; Zhang, J.H.; Luo, S.; Hu, J.W.; Sun, K. The Influence of Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior on Health-Related Quality of Life among the General Population of Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd ed.; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; p. 118.

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: A pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, M.; Inchley, J.; Sigmundova, D.; Iannotti, R.J.; Tynjälä, J.A.; Hamrik, Z.; Haug, E.; Bucksch, J. Secular trends in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in 32 countries from 2002 to 2010: A cross-national perspective. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25 (Suppl. S2), 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, E.M.; Corcoran, P.; O’Regan, G.; Keeley, H.; Cannon, M.; Carli, V.; Wasserman, C.; Hadlaczky, G.; Sarchiapone, M.; Apter, A.; et al. Physical activity in European adolescents and associations with anxiety, depression and well-being. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, H.M. Physical activity levels in Portuguese adolescents: A 10-year trend analysis (2006–2016). J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2018, 21, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro, A.; Oliveira-Santos, J.M.; Santos, R.; Ribeiro, J.C.; Santos, M.P.; Coelho-e-Silva, M.; Raimundo, A.M.; Sardinha, L.B.; Mota, J. Results from Portugal’s 2022 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. J. Exer. Sci. Fit. 2023, 21, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, K.; Cuff, S.; Council on Sports Medicine And Fitness; LaBella, C.R.; Brooks, M.A.; Canty, G.; Diamond, A.B.; Hennrikus, W.; Moffatt, K.; Nemeth, B.A.; et al. Organized Sports for Children, Preadolescents, and Adolescents. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20190997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R.M.; Young, J.A.; Harvey, J.T.; Charity, M.J.; Payne, W.R. A Systematic Review of the Psychological and Social Benefits of Participation in Sport for Children and Adolescents: Informing Development of a Conceptual Model of Health through Sport. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, S.A.; Swann, C.; Allen, M.S.; Schweickle, M.J.; Magee, C.A. Bidirectional Associations between Sport Involvement and Mental Health in Adolescence. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruner, M.W.; McLaren, C.D.; Sutcliffe, J.T.; Gardner, L.A.; Lubans, D.R.; Smith, J.J.; Vella, S.A. The Effect of Sport-Based Interventions on Positive Youth Development: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2023, 16, 368–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.B.; Allan, V.; Erickson, K.; Martin, L.J.; Budziszewski, R.; Côté, J. Are All Sport Activities Equal? A Systematic Review of How Youth Psychosocial Experiences Vary across Differing Sport Activities. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, C.L.; Linley, P.A.; Maltby, J. Youth Life Satisfaction: A Review of the Literature. J. Happiness Stud. 2009, 10, 583–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, C.L.; Linley, P.A.; Maltby, J. Life Satisfaction. In Encyclopedia of Adolescence; Levesque, R., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cai, Z.; He, J.; Fan, X. Gender Differences in Life Satisfaction Among Children and Adolescents: A Meta-analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 2279–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, M. Cross-national and longitudinal evidence for a rapid decline in life satisfaction in adolescence. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Looze, M.E.D.; Huijts, T.; Stevens, G.W.J.M.; Torsheim, T.; Volleberfgh, W.A.M. The Happiest Kids on Earth. Gender Equality and Adolescent Life Satisfaction in Europe and North America. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 1073–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graupensperger, S.; Sutcliffe, J.; Vella, S.A. Prospective Associations between Sport Participation and Indices of Mental Health across Adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 1450–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guddal, M.H.; Stensland, S.Ø.; Småstuen, M.C.; Johnsen, M.B.; Zwart, J.-A.; Storheim, K. Physical Activity and Sport Participation among Adolescents: Associations with Mental Health in Different Age Groups. Results from the Young-HUNT Study: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valois, R.F.; Zullig, K.J.; Huebner, E.S.; Drane, J.W. Physical activity behaviors and perceived life satisfaction among public high school adolescents. J. Sch. Health 2004, 74, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riddervold, S.; Haug, E.; Kristensen, S.M. Sports Participation, Body Appreciation and Life Satisfaction in Norwegian Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Scand. J. Public Health 2023. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubans, D.; Richards, J.; Hillman, C.; Faulkner, G.; Beauchamp, M.; Nilsson, M.; Kelly, P.; Smith, J.; Raine, L.; Biddle, S. Physical Activity for Cognitive and Mental Health in Youth: A Systematic Review of Mechanisms. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D.R. Emotional Intelligence: New Ability or Eclectic Traits? Am. Psychol. 2008, 63, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laborde, S.; Dosseville, F.; Allen, M.S. Emotional Intelligence in Sport and Exercise: A Systematic Review. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2016, 26, 862–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Romo, G.; Blanco-Garcia, C.; Diez-Vega, I.; Acebes-Sánchez, J. Emotional Intelligence of Undergraduate Athletes: The Role of Sports Experience. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 609154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yiyi, O.; Jie, P.; Jiong, L.; Jinsheng, T.; Kun, W.; Jing, L. Research on the Influence of Sports Participation on School Bullying among College Students—Chain Mediating Analysis of Emotional Intelligence and Self-Esteem. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 874458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilhjalmsson, R.; Thorlindsson, T. The Integrative and Physiological Effects of Sport Participation: A Study of Adolescents. Sociol. Quart. 1992, 33, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monshouwer, K.; ten Have, M.; van Poppel, M.; Kemper, H.; Vollebergh, W. Possible Mechanisms Explaining the Association between Physical Activity and Mental Health: Findings from the 2001 Dutch Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Survey. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 1, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos-Raposo, J.; Fernandes, H.M.; Teixeira, C.M.; Bertelli, R. Factorial Validity and Invariance of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale Among Portuguese Youngsters. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 105, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlén, K.; Suominen, S.; Augustine, L. The association between adolescents’ self-esteem and perceived mental well-being in Sweden in four years of follow-up. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsantonis, I.; McLellan, R.; Marquez, J. Development of subjective well-being and its relationship with self-esteem in early adolescence. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2023, 41, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Wu, L.; Ming, Q. How does physical activity intervention improve self-esteem and self-concept in children and adolescents? Evidence from a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle, S.J.; Asare, M. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: A review of reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rey Peña, L.; Extremera Pacheco, N.; Pena Garrido, M. Perceived Emotional Intelligence, Self-Esteem and Life Satisfaction in Adolescents. Psy. Interv. 2011, 20, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasp, M.; Navarro-Mateu, D.; Giménez-Espert, M.D.C.; Prado-Gascó, V.J. Emotional intelligence, empathy, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in Spanish adolescents: Regression vs. QCA models. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, F.; Zhao, J.; You, X. Emotional Intelligence and Life Satisfaction in Chinese University Students: The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem and Social Support. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2012, 53, 1039–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruvalcaba-Romero, N.A.; Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Salazar-Estrada, J.G.; Gallegos-Guajardo, J. Positive emotions, self-esteem, interpersonal relationships and social support as mediators between emotional intelligence and life satisfaction. J. Behav. Health Soc. Sci. 2017, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilca-Pareja, V.; Luque Ruiz de Somocurcio, A.; Delgado-Morales, R.; Medina Zeballos, L. Emotional Intelligence, Resilience, and Self-Esteem as Predictors of Satisfaction with Life in University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doré, I.; O’Loughlin, J.L.; Beauchamp, G.; Martineau, M.; Fournier, L. Volume and Social Context of Physical Activity in Association with Mental Health, Anxiety and Depression among Youth. Prev. Med. 2016, 91, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewett, R.; Sabiston, C.M.P.D.; Brunet, J.P.D.; O’Loughlin, E.K.M.A.; Scarapicchia, T.M.A.; O’Loughlin, J.P.D. School sport participation during adolescence and mental health in early adulthood. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 55, 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buecker, S.; Simacek, T.; Ingwersen, B.; Terwiel, S.; Simonsmeier, B.A. Physical Activity and Subjective Well-Being in Healthy Individuals: A Meta-Analytic Review. Health Psychol. Rev. 2021, 15, 574–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.; Wu, Y. The More Modest You Are, the Happier You Are: The Mediating Roles of Emotional Intelligence and Self-Esteem. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 1603–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, US, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4625-2334-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, N.; Rebelo, T.; Coelho, J.V. Adaptação da Escala de Inteligência Emocional de Wong e Law (WLEIS) e análise da sua estrutura factorial e fiabilidade numa amostra portuguesa. Psychologica 2011, 55, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.-S.; Law, K.S. The Effects of Leader and Follower Emotional Intelligence on Performance and Attitude: An Exploratory Study. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, F. The Satisfaction With Life Scale: Psychometrics Properties in an Adolescent Sample. J. Youth Adolesc. 1993, 22, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-4737-5654-0. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-203-77158-7. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.; Zhong, Q. The Impact of Sports Participation on Individuals’ Subjective Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Class Identity and Health. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Junoy, G.; Gavín-Chocano, Ó.; Ubago-Jiménez, J.L.; Molero, D. Differential Magnitude of Resilience between Emotional Intelligence and Life Satisfaction in Mountain Sports Athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.D.; Barnes, J.D.; Tremblay, M.S.; Guerrero, M.D. Associations between Organized Sport Participation and Mental Health Difficulties: Data from over 11,000 US Children and Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamminen, K.A.; Kim, J.; Danyluck, C.; McEwen, C.E.; Wagstaff, C.R.; Wolf, S.A. The Effect of Self-and Interpersonal Emotion Regulation on Athletes’ Anxiety and Goal Achievement in Competition. Psychol. Sport. Exerc. 2021, 57, 102034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.; Luo, J. The Relationship among College Students’ Physical Exercise, Self-Efficacy, Emotional Intelligence, and Subjective Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.M.; Sabiston, C.M.; Doré, I.; Bélanger, M.; O’Loughlin, J.L. Association between Pattern of Team Sport Participation from Adolescence to Young Adulthood and Mental Health. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2021, 31, 1481–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Range | M ± SD | Mean 95% CI | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sports participation | 0–1 | --- | --- | --- | |||||

| 2. EI Self-emotional appraisal | 5–20 | 15.53 ± 2.46 | 15.39–15.69 | 0.08 * | --- | ||||

| 3. EI Others’ emotion appraisal | 5–20 | 15.47 ± 2.40 | 15.35–15.65 | −0.03 | 0.19 ** | --- | |||

| 4. EI Use of emotion | 5–20 | 15.34 ± 2.78 | 15.18–15.52 | 0.20 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.11 ** | --- | ||

| 5. EI Regulation of emotion | 5–20 | 13.44 ± 3.18 | 13.27–13.66 | 0.04 | 0.37 ** | 0.01 | 0.36 ** | --- | |

| 6. Self-esteem | 10–40 | 30.95 ± 4.60 | 30.70–31.27 | 0.14 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.06 | 0.57 ** | 0.32 ** | --- |

| 7. Life satisfaction | 5–35 | 27.78 ± 5.44 | 27.44–28.11 | 0.06 * | 0.33 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.49 ** |

| Parameter | Estimate (Standard Error) | Bootstrap Bias-Corrected 95% CI (Lower, Upper) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific indirect effects | |||

| Sports participation → EI SEA → Self-esteem | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.00, 0.02 | 0.025 |

| Sports participation → EI SEA → Life satisfaction | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.01, 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Sports participation → EI SEA → SE → Life satisfaction | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.00, 0.02 | 0.022 |

| Sports participation → EI UoE → Self-esteem | 0.07 (0.02) | 0.05, 0.11 | <0.001 |

| Sports participation → EI UoE → Life satisfaction | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.02, 0.12 | 0.006 |

| Sports participation → EI UoE → SE → Life satisfaction | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.05, 0.14 | <0.001 |

| Total indirect effects | |||

| Sports participation → Self-esteem | 0.08 (0.02) | 0.05, 0.11 | <0.001 |

| Sports participation → Life satisfaction | 0.19 (0.04) | 0.12, 0.26 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Non-Sport Participation M ± SD | Individual Sports Participation M ± SD | Team Sports Participation M ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| EI Self-emotional appraisal | 15.39 ± 2.50 | 15.49 ± 2.65 | 16.06 ± 2.04 |

| EI Others’ emotion appraisal | 15.53 ± 2.46 | 15.58 ± 2.37 | 15.20 ± 2.19 |

| EI Use of emotion | 14.95 ± 2.76 | 15.73 ± 2.99 | 16.39 ± 2.32 |

| EI Regulation of emotion | 13.35 ± 3.22 | 13.22 ± 3.44 | 13.99 ± 2.76 |

| Self-esteem | 30.50 ± 4.70 | 31.34 ± 4.54 | 32.21 ± 4.02 |

| Life satisfaction | 27.53 ± 5.59 | 27.81 ± 5.71 | 28.62 ± 5.44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernandes, H.M.; Costa, H.; Esteves, P.; Machado-Rodrigues, A.M.; Fonseca, T. Direct and Indirect Effects of Youth Sports Participation on Emotional Intelligence, Self-Esteem, and Life Satisfaction. Sports 2024, 12, 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports12060155

Fernandes HM, Costa H, Esteves P, Machado-Rodrigues AM, Fonseca T. Direct and Indirect Effects of Youth Sports Participation on Emotional Intelligence, Self-Esteem, and Life Satisfaction. Sports. 2024; 12(6):155. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports12060155

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernandes, Helder Miguel, Henrique Costa, Pedro Esteves, Aristides M. Machado-Rodrigues, and Teresa Fonseca. 2024. "Direct and Indirect Effects of Youth Sports Participation on Emotional Intelligence, Self-Esteem, and Life Satisfaction" Sports 12, no. 6: 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports12060155