Abstract

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) significantly contribute to society’s growth and welfare. Nevertheless, SMEs often experience challenges, i.e., high levels of competition and market demands. To maintain SMEs’ existence, a competitive advantage is demanded by increasing innovative work behavior. This study explores and evaluates the relationship between transformational leadership and innovative work behavior and examines the mediating role of knowledge sharing and psychological empowerment on the relationship between transformational leadership and innovative work behavior. This study uses a quantitative approach, where data were gathered from a questionnaire distributed to 190 employees of export SMEs and were further examined using Smart PLS 3.2.9. The findings demonstrate that transformational leadership does not influence innovative work behavior but significantly and positively influences psychological empowerment and knowledge sharing. Psychological empowerment and knowledge sharing significantly and positively influence innovative work behavior. Subsequently, psychological empowerment and knowledge sharing partially mediate the linkage between transformational leadership and innovative work behavior.

1. Introduction

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) make a significant contribution to development and community welfare. However, SMEs face challenges, namely high levels of competition and market demand [1,2]. To survive in the competition, SMEs need competitive advantages [3,4]. Stimulating innovation [5] and innovative work behavior (IWB) [6] are ways to achieve competitive advantages. Currently, there is an emerging interest in studying innovation, especially IWB [7,8,9], which is considered important in facilitating organizational performance [10,11,12,13]. However, SMEs cannot yet achieve innovation. In economic theory, SMEs still have several limitations, such as labor, finance, and small market scope [14]. All results in SMEs not having the ability to invest in technology as a driving factor for accelerating innovation [15]. On the other hand, SMEs must continue to strive to find ways to strengthen their competitive position and productivity [16].

In general, innovation is the ability of an organization to optimize assets and capabilities that aim to change the work results achieved [17,18]. In the development organization, innovation is emphasized in product innovation and process innovation [19]. Limited financial capacity results in reduced process innovation in SMEs [20], while product innovation is largely determined by the skill level of the workforce [21]. Previous studies have shown that TL has an impact on the development of innovation, which does not occur under traditional leadership [22]. TL substantially influences a company’s ability to be more responsive when creating products and carrying out process innovation to generate efficiency [23]. As is known, knowledge that supports organizational characteristics can be achieved through knowledge-sharing practices and the employee empowerment process. Thus, investigations continue to be carried out to examine the influencing variables [24].

In the last few decades, scholars have identified leadership success in increasing IWB, i.e., transformational leadership (TL) [25,26]. TL was initially outlined by Bruns (1978) [27], which was later extended by Bass (1985) [28] by elucidating the psychological mechanisms underlying it. TL has progressed and proven to be impactful in increasing positive organizational identification [29]; organizational commitment [30,31]; organizational culture [32,33]; knowledge sharing [26,34]; creativity [35]; and IWB [1,36]. Nonetheless, different findings were demonstrated in [37], which reports that TL does not positively affect IWB. Thus, it is crucial to investigate the linkage between TL and IWB, which remains underdeveloped in the SMEs context, given that SMEs require IWBs to deal with a dynamic environment [38].

Therefore, the investigation of the relationship between TL and IWB needs to be carried out based on several considerations. First, it is important to find out the level of understanding of TL in SMEs, because it will be difficult to improve work behavior if leaders do not support it. Second, Bednall et al. (2018) [39], in their study, proposed that TL is categorized into three levels, namely low, medium, and high. If TL is perceived as low, the impact shown tends to be negative. Therefore, this comprehensive study provides conceptual insight into the important role of leaders, especially in regard to TL, which has a good impact on organizations [40]. On the other hand, SMEs are businesses that are often managed using traditional management, which ignores the managerial aspects that apply to large businesses. This is characterized by the difficulty of distinguishing between leadership and ownership. Usually, the owner directly acts as a decision-maker. Therefore, it is very possible for absolute decisions to occur, which hurts SMEs. Like SMEs in the field of handcrafts, the owner or manager develops products by involving designers from outside the SME, and employees are only tasked with making products based on the examples given. In other words, employees are not involved in product development, meaning that IWB is only carried out on work-related technical matters. All of this influences how management practices, such as production and other operations, create ambiguity and social complexity. Employees can become more growth-oriented when they are faced with more challenging work that makes them want to develop their thinking and authority [41,42]. For this reason, it is very possible to introduce the concept of transformational leadership to owners in managing SMEs. Moreover, SMEs are currently faced with tight competition, requiring them to formulate strategies through leadership that can accommodate visions and goals.

Therefore, psychological empowerment (PE) was proposed to facilitate the relationship between TL and IWB [40,43]. Traditionally, empowerment is an opportunity to decide [44,45]. In this regard, it has been argued that IWB occurs through empowerment, as employees who are involved in the decision-making process and have the opportunity are more likely to contribute. Therefore, PE is predicted to stimulate employees’ innovative abilities [40]; when subordinates are psychologically empowered, they will be autonomously driven to display innovative behavior [44]. However, unlike what is happening in SMEs today, SME management does not provide employees with the opportunity to contribute to product and process development. Employees in this area tend to act as implementers of the development results that must be carried out. SMEs are supported by employees who are skilled in their fields. Thus, if PE is achieved by providing employees with the opportunity to contribute, it is also predicted to be able to mediate TL and IWB [44,46].

Several studies also report that knowledge sharing (KS) makes a significant contribution to increasing IWB [47,48,49,50,51]. For example, Vandavasi et al. (2020) [52] reveal that KS directly and indirectly affects leadership development and IWB. KS process produces innovative work behavior [53]. Further, organizational drive for knowledge acquisition can promote, generate, and realize innovative ideas [54]. Therefore, leaders must improve KS practices to achieve competitive advantage through IWB.

This study was conducted on export SMEs in Bali with several considerations. First, SMEs provide employment and are a source of income, especially for developing countries, such as Indonesia. In addition, export SMEs have also been proven to make important contributions to their countries in recent decades.

Second, export SMEs face increasing competition along with global economic growth, so increasing innovation capacity could be a solution for SMEs. However, measuring innovative work behavior has so far tended to be carried out in large companies. Third, a study is needed on innovation from the perspective of SME employees [55]. The achievement of employee innovative behavior can likely be carried out with TL, because of their ability to interact with subordinates [2,56]. In addition, innovative behavior requires other supporting factors, such as knowledge [57] and empowerment [43]. These reasons are the foundations for why further investigation is needed.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Social Exchange Theory

Social exchange theory (SET) is an intentional action driven by a correspondence between potentials and what they acquire [58,59]. SET has a fundamental postulate: substituting social and substantial capital is the primary form of human exchange [60]. The theory encourages people to cultivate behavior based on prospects and obliges them to be dedicated to organizations. SET becomes crucial for leaders who wish to highlight connections with subordinates [61]. Kim and Beeh (2018) [62] state that leaders who offer encouragement, discuss pivotal decisions, present more independence, and eradicate redundant administrative restraints affect subordinates’ behavior. This is to the theory of transformational leadership that has been developed by referring to the psychological approach that can influence individuals’ nature, character, and motivation as a form of transformation [63]. However, the increase in IWB is also determined by an employee’s desire to achieve a goal they are targeting, as explained in the self-determination theory (SDT) [64]. In addition, SDT can also provide the view that employees are willing to contribute because of intrinsic motivation which impacts well-being [65]. Hsieh and Wang (2015) [66] assert that empowerment strongly influences interpersonal attitudes and behavior. PE is an elemental step in communal linkage [58] and attaches employees emotionally to their leaders [67]. Empowerment leads to positive results, i.e., boosting employees’ desire for KS [68,69].

2.2. Transformational Leadership and Innovative Work Behavior

The TL approach emphasizes personal attention and support to elevate the influence of leaders on employee engrossment in creative activities. The assumption questions and contests subordinates’ reasoning while accelerating the employees’ intellectual involvement in the creative process [36]. Bednall et al. (2018) [39] report that leaders who combine organizational with individual goals increase subordinates’ motivation. Therefore, transformational leaders inspire their subordinates by bonding employees’ and organizations’ futures, and thus, employees feel compelled to demonstrate and engage in creative behavior. Several studies show that TL positively impacts IWB [70,71]. These reports demonstrate that transformational leaders elevate IWB using inspirational motivation that fosters self-confidence to continuously attain new ideas without judging the results at the implementation stage [36]. Implementing ideas is a pivotal point of IWB. Thus, social support and acceptance are vital in implementing creative behavior, where transformational leaders overcome problems that arise from implementing ideas by prioritizing collective thought, vision, and interests [72,73]. Through personal consideration, transformational leaders reach a balance between individual and organizational goals. Consequently, employees feel confident in accomplishing their goals and performing innovative processes to improve organizational performance. Hence, the first hypothesis of this study is as follows:

H1.

TL is positively related to IWB.

2.3. Transformational Leadership and Psychological Empowerment

TL affects subordinates’ personalities. Accordingly, we anticipate that positive results will also influence PE. However, evidence shows that employees have different degrees of acceptance and belief in what they perceive as an empowered process from TL [10]. To explain the expectation, we used a SET approach [58,59] to verify the concept that persons cultivate their behavior following future expectations and become devoted to organizations [74]. SET is significant for leaders concentrating on employee communication [61]. Hsieh and Wang (2015) [66] argue that empowerment is an effective way to influence employee attitudes and behavior in order to positively influences employee behavior [68,69]. Recent studies state that the empowerment process can be performed using a psychological approach [75]. Mufti et al. (2020) [76] report that psychologically empowered employees decide to bond and devote significant efforts to the organization. Studies further reveal that TL positively impacts PE [40,77,78]. From the above opinions, the second hypothesis is as follows:

H2.

TL is positively related to PE.

2.4. Transformational Leadership and Knowledge Sharing

Knowledge holds an imperative role in organizational advancement [79]. Moreover, knowledge is an essential asset that supports creating unique values [80]. Knowledge can be attained through formal processes and KS. Mittal and Dhar (2015) [35] explain KS as distributing ideas/information through employees’ interactions. Nevertheless, the quality of KS can be observed from communication quantity and individual competence [81]. Subsequently, the social interaction process involves all employees, and the role of the leader is required to facilitate this interaction. Theoretically, leadership supports employees in cultivating KS attitudes and behaviors [82,83]. However, leaders encounter various challenges, i.e., the reluctance of employees to perform KS because they consider knowledge a bargaining chip [84,85,86]. Previous studies have mentioned many factors influencing employees to carry out KS, including TL [26,34]. Following the findings from the previous studies [87,88], this study argues that TL encourages subordinates to develop values for change [89]. Therefore, the third hypothesis is as follows:

H3.

TL is positively related to KS.

2.5. Psychological Empowerment and Innovative Work Behavior

Discussing PE is crucial to provide views on an individual’s orientation towards their work. This orientation is rooted in four cognitions, i.e., meaning, competence, self-determination, and impact [90]. Employees with PE will demonstrate dedication and resilience and devote increased effort toward their work [91]. PE drives employees to accept additional responsibilities, be more independent, and simultaneously boost organizational achievements [92]. PE is a cognitive inspiration for understanding organization [93]. Positive work derived from PE is imperative in shaping IWB [94,95]. Furthermore, empowerment is about employees’ belief in their role and linkage with the organization rather than power distance that limits superiors to subordinates or delegating tasks [96]. Employees’ confidence in performing tasks will influence their success [97]. Employees will demonstrate innovative behavior through PE. Stanescu et al. (2021) [40] reported that PE encourages IWB. The sense of being empowered impacts employees’ IWB. These findings are consistent with studies that state that PE increases IWB [50,93]. Thus, the fourth developed hypothesis is as follows:

H4.

PE is positively related to IWB.

2.6. Knowledge Sharing and Innovative Work Behavior

Studies report that knowledge is a crucial part in organizational growth. Amabile and Pratt (2016) [98] state that knowledge is a critical constituent of creativity. Knowledge also positively impacts the development of innovation [79,99]. KS is paramount for employees to acquire knowledge from inside and outside the organization [50]. KS is an innovative elucidation that enables organizations to improve the latest goods and services [100,101,102]. KS is crucial in developing innovation systems and work results, i.e., productivity, learning, and innovation [103]. KS aids employees in creating and developing ideas [104]. Mura et al. (2013) [105] and Liu et al. (2011) [106] describe sharing as a best practice in producing and implementing ideas among employees. Recent studies examine the linkage between KS and IWB [49,105,107]. The studies illustrate that KS positively impacts IWB. Employees’ enthusiasm to practice KS allows organizations to introduce IWB [103] and helps them create, promote, and implement innovation [108]. The enthusiasm to exchange information/knowledge stimulates the thinking process in generating new ideas. Therefore, the fifth hypothesis is as follows:

H5.

KS is positively related to IWB.

2.7. The Role of Mediating Knowledge Sharing and Psychological Empowerment

Individual contributions should be increased to develop the organization, i.e., conducting KS, especially in generating new knowledge [90]. KS is exchanging relevant information and experiences with employees in the organization [50]. KS can be performed through documents, experiences, procedures, information, and other knowledge [109,110]. The imperative role of KS is to help employees’ IWB [1]. Furthermore, studies demonstrate that KS links variables [50,111], especially leadership [112,113]. Furthermore, Sudibjo and Prameswari (2021) [37] report that KS mediates TL and IWB. This finding is inseparable from the low level of participation in TL practices, resulting in a negative correlation with innovative behavior. Consequently, knowledge is crucial in enhancing the linkage [51,57]. Therefore, we developed the sixth hypothesis:

H6.

KS positively mediates the relationship between TL and IWB.

PE increases employees’ internal motivation toward work [114], providing stimuli for change, flexibility, and innovative behavior. Ryan and Deci (2000) [115] explain that the freedom given to employees (not restricted by regulations) tends to work more innovatively. Consequently, employees who feel empowered exhibit new and creative behaviors. Employees thus assume challenging work and generate innovative solutions and behaviors [116,117]. Researchers examine the significant role of mediating effects. The mediation test is utilized to explore the linkage under study, especially in improving IWB. Therefore, it is crucial to examine PE to mediate TL. Although the role of PE in the linkage between TL and IWB has been addressed in previous studies [40,50,92], the findings prove that PE is a mediation, yet the linkage of TL is inconsistent with IWB [37,118]. Accordingly, the seventh hypothesis is as follows:

H7.

PE positively mediates the relationship between TL and IWB.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling and Respondents

Data were collected from exporting SMEs in Bali province to examine the relationships between the constructs used. Export SMEs represent an industry active in production and export activities. The population of this research was 38 industries consisting of four industrial sectors: handicrafts (27), furniture (9), garments (2), and jewelry (4). The sample was determined using saturated sampling by utilizing the entire population. Respondents were chosen by recruiting five employees who were assumed to exhibit innovative work behavior. Based on calculations, there were 190 respondents involved in this study. Data were gathered from a questionnaire made in Google Forms that was distributed online via e-mail and other media. Google Forms was chosen for two reasons. First, people’s familiarity with technology is significant; employees can fill out questionnaires anytime. Second, Google Form’s easy operation sped up the data collection process. The study was conducted between September and December 2023.

Several considerations underlie the selection of export SMEs as research locations. First, export SMEs are dominated by businesses engaged in crafts. This makes innovative behavior very much needed to develop variations in the products produced and to find more effective methods in the production process. Second, export SMEs have stability—this can be seen from the age of the businesses, which is more than five years—and consistently carry out business activities [119]. However, if innovative work behavior is not facilitated, these export SMEs may be displaced by other producing countries supported by the latest technology. Third, although creative employees support SMEs, their opportunities to contribute to product and process development are still limited. This is because the hierarchical culture formed from local culture is still strong. All of these are further reasons why this research must be conducted.

3.2. Measurements

This study constructed four variables: TL, PE, KS, and IWB. The variables were examined using a five-point Likert scale (1 is strongly disagree and 5 is strongly agree).

- TL is measured by eight statement items adopted from Jaiswal and Dhar (2015) [120] and Jyoti and Dev (2015) [121]: leaders as change makers, articulation of visions, inspiring employees, supporting employees, generating ideas, giving freedom, and paying attention to employees’ needs.

- PE is measured through seven statements adopted from Helmy et al. (2019) [50] and Shahzad et al. (2018) [77]: the significance of work, meaningful personal, confidence, skills, making an impact, deciding, and independence.

- KS is measured by nine statements adopted from Masta and Riyanto [122] and Riana et al. (2020) [112]: sharing knowledge without being asked, receiving knowledge without asking, sharing knowledge is normal, learning from colleagues, seeking information, developing skills, desire to learn, technological support, and organizational roles.

- IWB is measured through nine statement items adopted from Vandavasi (2020) [52]: creating new ideas, seeking new methods, generating solutions, supporting innovative ideas, obtaining approval, enthusiasm, adapting ideas, introducing ideas, and evaluating ideas.

3.3. Data Analysis

Data collection was performed in two steps. First, data were collected from 30 respondents to examine the instrument’s validity and reliability. Validity was calculated using the product–moment coefficient test (r) with a cut-off of 0.3 (r > 0.3), and reliability was observed from the value of Cronbach’s alpha test with a cut-off of 0.6 (CA > 0.6), using IBM SPSS 21. Second, once the instrument was affirmed to be valid and reliable, the data collection was continued by distributing the questionnaires to the specified respondents. Subsequently, SmartPLS 3.2.9 was utilized to examine the data.

4. Results

4.1. Research Instrument Testing

Instrument testing was performed to verify that the instruments utilized described reality, and they were trusted and reliable. The validity of using the product–moment coefficient test (r) with a cut-off of 0.3 (r > 0.3) and reliability were observed from the value of Cronbach’s alpha test with a cut-off of 0.6 (CA > 0.6). Consequently, all instruments met the validity and reliability criteria.

4.2. Descriptive Analysis

Information was obtained about the demographics of the respondents (Table 1), illustrating gender, age, education, and experience.

Table 1.

Respondent demographics.

Table 1 shows that the majority of SME employees are women. This could be a result of the initial establishment of SMEs as home industries, and it is the choice of Balinese women to be flexible in their three primary activities (work, household, and socializing). Respondents’ ages ranged from 31 to 40 years. This signifies that these employees are of a mature mental age and can be assumed to be confident. Further, these data reveal that respondents graduated from high school/vocational school education. Thus, competency improvement can be conducted through education and training. Subsequently, service length indicates that most employees have 11 to 20 years of tenure. This suggests that respondents are comfortable in their positions and are unwilling to seek a new job that requires adapting to a new environment.

4.3. Measurement of Outer Model

The examination began with measuring the outer model to evaluate the data quality used to calculate the research model. First, convergent validity is observed from the outer loading value above 0.6. Second, testing was carried out by observing discriminant validity. In this study, we assessed discriminants through the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT). The Fornell–Larcker criterion is obtained by comparing the value of the average variance extracted (√AVE) root coefficient with other constructs. The AVE value is said to be valid if it has a significance that is greater than 0.5, while HTMT has a criterion below 0.85. The third step is to measure the value between items of the construct through composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha. The construct is reliable, with a greater significance than 0.7 [123].

The outer loading value is greater than 0.6, and the AVE is greater than 0.5. The HTMT ratio shows a value smaller than the threshold of 0.85. Thus, it is believed to be able to establish the discriminant validity of the reflective construct. The analysis also shows Cronbach’s alpha values range from 0.873 to 0.928, and composite reliability ranges from 0.900 to 0.940, and is greater than 0.7. Thus, the construct is free from random error problems (see Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2.

Instrument reliability test.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity.

4.4. Measurement of Inner Model

The examination continues with measuring the inner model after the criteria for the outer model are met. First, model feasibility will be evaluated by uncovering the correlation between exogenous and endogenous variables through the R-square value (R2). Hair et al. (2013) [124] assert that the R2 value has three categories: strong (value 0.67), moderate (value 0.33), and weak (value 0.19) [123]. Table 4 illustrates the analysis results.

Table 4.

Research model feasibility.

Table 4 illustrates that the R2 value of each construct is significantly greater than 0.33, indicating that the model is moderate. For an average value of 0.419, this result explains that the construct has a linkage of 41.9 percent, and 58.1 percent is influenced by other variables not discussed in this study. These findings indicate that adjusted R2 can be increased by including other variables in future research.

The next step is to measure the model’s predictive ability by quadratic predictive relevance (Q2) using the Stone–Geisser value [124]. The Q2 value is relevant if it is more than 0 and is close to 1, which is the better prediction [125]. Thus, Table 5 shows the Q2 predictive value of more than zero KS, PE, and IWB, which means that endogenous latent constructs have predictive relevance [126].

Table 5.

Quadratic predictive relevance (Q2).

The goodness of fit (GoF) value is 0.509, indicating the model has excellent measurement accuracy because it has a value of more than 0.36 [127]. Then, the effect size (f2) is assessed to make predictions between exogenous and endogenous variables [128]. Chin (1998) [123] states that the effect size has three categories: weak (0.02–0.15), moderate (0.15–0.35), and strong (more than 0.35). The results reveal an average value of 0.449 (see Table 6). Thus, a strong linkage pattern is predicted [128].

Table 6.

Effect size.

4.5. Hypotheses Testing

Table 7.

Hypotheses testing.

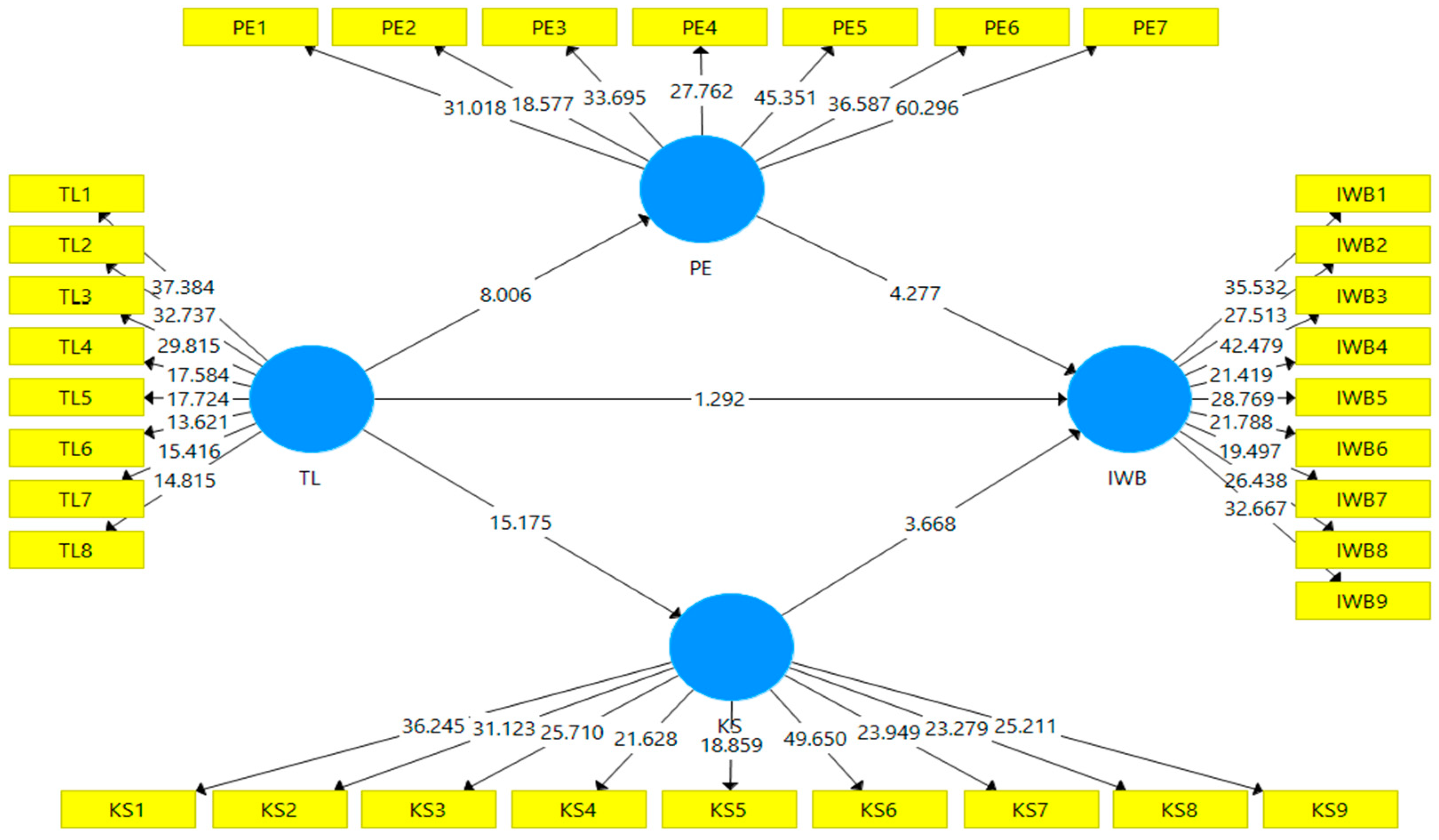

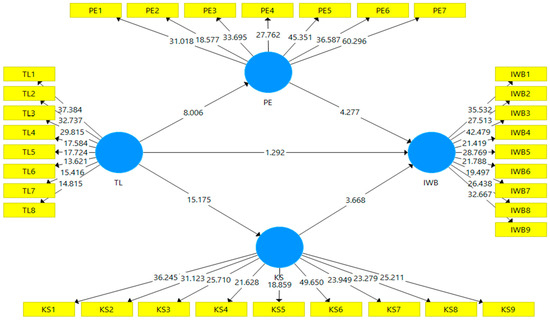

Figure 1.

Bootstrapping model, smart PLS.

The investigation reveals that TL does not affect IWB (β = 0.145, t = 1.292); therefore, H1 is not supported. However, TL significantly and positively affects PE (β = 0.495, t = 8.006) and KS (β = 0.746, t = 15.175); thus, H2 and H3 are supported. Further, the examination reveals that PE significantly and positively affects IWB (β = 0.281, t = 4.277); hence, H4 is supported. KS also significantly and positively affects IWB (β = 0.395, t = 3.668); accordingly, H5 is supported. The testing of the indirect effect shows that KS and PE are mediators (β = 0.294, t = 3.456; β = 0.139, t = 3.859); thus, H6 and H7 are supported. Calculations are performed to ascertain the mediating role of each variable using variance accounted for (VAF) [124], showing KS and PE as partial mediations.

5. Discussion

Organizations require leaders to empower and practice KS to advance economic growth in developing countries like Indonesia. This study scrutinizes whether TL can encourage empowerment, knowledge, and enhance innovative behavior. Through improving innovative behavior, organizations can attain a sustainable competitive advantage. This study examines the linkage between TL and IWB in SMEs. The findings of this study are explained as follows.

First, the findings report that TL does not affect IWB. The finding explains that the increase in TL practices does not increase IWB. These findings support previous studies [37,39,129,130], confirming that SMEs do not adopt modern management practices, unlike large companies. Thus, practices related to management, i.e., leadership, have yet to show a significant impact because SMEs adhere to the kinship principle. Consequently, the closeness factor is established from the start, influencing task delegation and accountability. The industrial scale also does not regulate bureaucratic distance between leaders and subordinates—considering SMEs with talented employees. Moreover, the craft industry employees’ skills are adequate for establishing IWB. Therefore, IWB is well accommodated without the demand for a specific type of leadership. Bednall et al. (2018) [39] report that TL may not affect IWB since the implementation of TL still requires improvement.

These findings show that innovation in SMEs must maximize external factors through an open innovation system [131]. Through open innovation activities, it is related to innovation performance [132]. Open innovation can be a solution for SMEs to overcome the limitations of their resources [133]. Where this evidence has been discussed previously, such as by Mount and Martinez (2014) [134], it can be seen that companies involved in open innovation directly gain knowledge from external partnerships and alliances from the results of the innovation that are carried out. Open innovation is another step for leaders to increase innovative behavior. In other words, open innovation can be facilitated by involving potential partners and creating a development and training program for SMEs. Similarly, open innovation provides a framework that allows for the comparison of social interventions across sectors in socio-economic and institutional contexts [135].

In addition, the application of open innovation can be a step in encouraging traditional management to be more innovative, so that organizational management becomes better [136,137]. Open innovation practices can also provide SMEs with the opportunity to overcome the limitations they have, i.e., related to resources, finance, and business [138].

The inability of TL to increase innovation is inseparable from the organizational structure of SMEs, which is relatively simple, unlike that of large businesses. This can be seen from the absence of an HR management system [139], resulting in the innovative behavior designed by TL receiving less attention. All of this is inseparable from ownership, which often ignores how TL efforts can contribute to increasing innovative behavior. Previous findings have stated that the decision to invest in HR is an important factor in increasing organizational capacity [140].

Second, TL significantly increases PE and KS, which indicates that the better TL is, the more PE and KS is present in SMEs. To survive increasingly fierce competition, joint efforts are required. This result supports previous studies that mention that TL increases PE [84,87,88] and elevates KS practices [26,34,82,83]. Leaders can optimize subordinates’ roles by performing PE and encouraging KS. Therefore, leaders who empower employees and facilitate KS help SMEs survive amid competition.

Third, KS and PE significantly and positively affect IWB. This finding demonstrates that the better the empowerment and the higher the KS, the more IWB increases. This study confirms the results of previous studies that reveal that PE increases IWB [44,50,93,96]. KS similarly impacts IWB [1]. Efforts to increase IWB in SMEs must include empowerment and knowledge. PE can be an intrinsic motivation for employees [114], while KS is vital to acquiring new knowledge [141]. Both are able to increase innovative behavior.

Fourth, the proposed research model includes the mediation of KS and PE. Our research discovered that PE mediates TL and IWB. This finding confirms the results of previous studies that report that PE intervenes in the linkage between TL and IWB [40,74,142], especially regarding employees’ way of thinking [10]. These findings expand on previous studies by Sudibjo and Prameswari (2021) [37] and Bednall et al. (2018) [39] by incorporating PE in the linkage between TL and IWB. Moreover, these findings demonstrate that employees must be adequately empowered beyond their roles as recipients and operational executors. Thus, PE drives them to be more motivated when improving their performance by showing innovative behavior.

Subsequently, our research demonstrates that KS mediates TL and IWB. These findings confirm the results of previous studies [1,26,37].

This verifies that leaders need to facilitate KS to be more innovative in their work. Moreover, KS regulates IWB in SMEs, especially in developing countries like Indonesia. Leadership with a transformational approach encourages subordinates to share more knowledge, information, skills, and expertise, which impacts the increase in innovation [87]. Moreover, knowledge supports leaders when encountering environmental changes and acquiring new information to seize opportunities efficiently [38]. Thus, this study fills in the gaps in the findings of Sudibjo and Prameswari (2021) [37] and Bednall et al. (2018) by revealing when, how, and why TL can be linked to IWB.

The success of an organization in achieving innovation is certainly determined by the characteristics of the organization itself. Like start-ups, they need supporting factors for innovation, i.e., leadership, technology, knowledge, and support from the environment [143,144,145]. Similar factors are also found in innovative companies that prioritize leadership to solve existing problems, although they do not completely ignore other aspects that support business development [146]. In addition, employee development policies and procedures are an investment for innovation [147]. In contrast, spin-off companies need innovation to explore opportunities [148], and leadership is needed to build a team to achieve this [149]. Looking at the comparison of innovative companies, spin-offs and start-ups have different orientations towards innovation and leadership. However, in general, all types of companies need innovation and leadership to improve their business performance. Thus, if SMEs want to remain competitive, they must separate management and ownership. The goal is to increase competitiveness and achieve business sustainability. Although SMEs currently have various limitations, innovation can be achieved through open innovation involving partnership programs.

6. Conclusions

First, TL does not encourage IWB. This finding indicates that SMEs’ adoption of TL remains low. Second, TL supports employees KSe and has been proven to be successful in PE through increasing intrinsic motivation. Third, KS and empowerment influence IWB. This indicates that employees’ KS practices help them to be more innovative at work. Empowered employees are more motivated and tend to demonstrate innovative behavior at work. Fourth, KS and PE mediate TL and IWB. Thus, KS and PE bridge transformational leaders in incorporating IWB. Consequently, SME leaders must contribute to KS and PE to influence employees, especially in terms of advancing work behavior.

This study also has several limitations. First, the sample size was limited to export SMEs in Bali, Indonesia. When considering the number of export SMEs in Indonesia, the sample size of 38 is relatively small. As Indonesia has a variety of cultures and regional potentials, this results in existing SMEs having their own uniqueness that influences their type of business. Several regions in Indonesia have agricultural potential, so the products produced are often natural. Meanwhile, craft SMEs in other provinces prioritize the production of ornaments, as a result of local skills and capabilities. These differences determine how the routine and strategic processes are implemented by leaders/owners in management [150]. So, this requires researchers to be careful in generalizing these results. Therefore, the number of samples is our main limitation and allows us to only analyze certain sectors under the conditions that occur. It is thus important to conduct similar studies involving other sectors in order to offer broader results with larger sample sizes or in other domains. Second, this study is cross-sectional; thus, the information obtained over a certain period and the contingent effects cannot be confirmed. Therefore, future research should be carried out as longitudinal studies [151]. This is because longitudinal research can test the dynamic nature of constructs, and thus researchers can focus on changes that occur in the observed construct, not only on the representation of the measured construct [152]. In this way, researchers can gain knowledge related to changes that occur over time and changes following the predictions made [153]. This is a gap that can be filled by future research through longitudinal studies. Third, TL does not affect IWB. Therefore, these findings can be used to underpin future studies in order to explore the role of TL in enhancing SME employees’ IWB.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This study examines the role of TL in KS, PE, and IWB. Thus, this study provides several theoretical contributions. First, TL does not directly affect IWB. However, TL mediates KS and PE. It is inseparable from KS and PE, which directly increase IWB. These results provide an altered perspective of SET. These findings indicate that TL does not determine IWB because employees perceive that social exchange is a driving force for deciding work behaviors. Second, KS and PE mediate the linkage between TL and IWB. These results indicate that leaders can encourage KS practices and foster psychological empowerment in employees to increase IWB.

6.2. Practical Implications

There are several managerial implications for managers and employees. First, managers must better understand and develop TL in business management, especially in export SMEs, in order to produce IWB. All of this is in accordance with the theory of social exchange, where social interactions that are built into the company can connect managers with their subordinates. Second, leaders are required to facilitate KS so that employees become more innovative when carrying out their jobs. Knowledge can be achieved by providing training and development, forming work groups, and undertaking other activities that make it easy for them to exchange information. Third, a manager must improve PE. The empowerment that is achieved can increase employee confidence so that they become more effective in their work. In addition, they may seek and find innovative steps in the completion of their work. Finally, based on the employee perspectives, KS and PE are needed and can be a strategic step in increasing employee competence and trust in managers and the company.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.N.A.; methodology V.K.; software, N.M.D.P. and P.P.P.S.; validation, V.K. and I.N.A.; formal analysis, I.N.A. and T.P.; investigation, I.N.A. and V.K.; resources, P.P.P.S., T.P. and N.M.D.P.; data curation, O.K. and V.K.; writing—original draft preparation, I.N.A.; writing—review and editing, V.K. and O.K.; visualization, N.M.D.P. and P.P.P.S.; supervision, V.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Universitas Mahasaraswati Denpasar for organizing the 2023 Internal Research Grant with decree number: K. 637/C.13.02/Unmas/IV/2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is a non-interventional study which does not require approval from the ethics committee. This statement was made by the dean of the faculty of economics and business with the number: K.0511/A-17.01/FEB/IX/2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Thank to Thank you for reviewer (s) for very constructive and valuable reviews and comments for enhancement of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

There were no conflicts of interest in the writing or publication of this article.

References

- Arsawan, I.W.E.; Koval, V.; Rajiani, I.; Rustiarini, N.W.; Supartha, W.G.; Suryantini, N.P.S. Leveraging knowledge sharing and innovation culture into SMEs sustainable competitive advantage. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2022, 71, 405–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knezović, E.; Drkić, A. Innovative work behavior in SMEs: The role of transformational leadership. Empl. Relat. 2021, 43, 398–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elidemir, S.N.; Ozturen, A.; Bayighomog, S.W. Innovative behaviors, employee creativity, and sustainable competitive advantage: A moderated mediation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryantini, N.P.S.; Arsawan, I.W.E.; Darmayanti, N.P.A.; Moskalenko, S.; Gorokhova, T. Circular economy: Barrier and opportunities for SMEs. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 255, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisjah, S.; Arsawan, I.W.E.; Suhartanto, D. Predicting SME’s business performance: Integrating stakeholder theory and performance based innovation model. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsawan, I.W.E.; Koval, V.; Suhartanto, D.; Hariyanti, N.K.D.; Polishchuk, N.; Bondar, V. Circular economy practices in SMEs: Aligning model of green economic incentives and environmental commitment. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2023, 73, 775–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, T.; Lei, S.; Haider, M.J. The impact of relational leadership on employee innovative work behavior in IT industry of China. Arab. Econ. Bus. J. 2016, 11, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.A.; Yasir, M.; Majid, A.; Ahmad, S. Talent Management Practices, Psychological Empowerment and Innovative Work Behavior: Moderating Role of Knowledge Sharing. City Univ. Res. J. 2015, 19, 567–585. [Google Scholar]

- Qalati, S.A.; Zafar, Z.; Fan, M.; Sánchez Limón, M.L.; Khaskheli, M.B. Employee performance under transformational leadership and organizational citizenship behavior: A mediated model. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Badir, Y.; Saeed, B. Transformational leadership and innovative work behavior. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2014, 114, 1270–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alosani, M.S.; Yusoff, R.; Al-Dhaafri, H. The effect of innovation and strategic planning on enhancing organizational performance of Dubai Police. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2019, 17, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milbratz, T.C.; Gomes, G.; De Montreuil Carmona, L.J. Influence of learning and service innovation on performance. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2020, 17, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.T.A. Does organizational innovation always lead to better performance? A study of firms in Vietnam. J. Econ. Dev. 2019, 21, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunila, M. Performance measurement approach for innovation capability in SMEs. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2016, 65, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalil, M.F.; Ali, A.; Kamarulzaman, R. Does innovation capability improve SME performance in Malaysia? The mediating effect of technology adoption. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2022, 23, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M.; Hong, T.S.; Sabouri, M.S.; Zulkifli, N. Strategies for successful information technology adoption in small and medium-sized enterprises. Information 2012, 3, 36–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.M.; Styles, C.; Lages, L.F. Breakthrough innovation in international business: The impact of tech-innovation and market-innovation on performance. Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 26, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojnik, J.; Ruzzier, M. The driving forces of process eco-innovation and its impact on performance: Insights from Slovenia. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 812–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid-Guijarro, A.; Garcia, D.; Van Auken, H. Barriers to innovation among spanish manufacturing SMEs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2009, 47, 465–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutahayan, B.; Yufra, S. Innovation speed and competitiveness of food small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) in Malang, Indonesia: Creative destruction as the mediation. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2019, 10, 1152–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Husseini, S.; Elbeltagi, I. Transformational leadership and innovation: A comparison study between Iraq’s public and private higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2016, 41, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Martins, J.M.; Mata, M.N.; Naz, S.; Akhtar, S.; Abreu, A. Linking entrepreneurial orientation with innovation performance in smes; the role of organizational commitment and transformational leadership using smart PLS-SEM. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.J.; Choi, J.N. Overtime work as the antecedent of employee satisfaction, firm productivity, and innovation. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.; Miller, A.F. Innovative work behavior through high-quality leadership. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2020, 12, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Husseini, S.; El Beltagi, I.; Moizer, J. Transformational leadership and innovation: The mediating role of knowledge sharing amongst higher education faculty. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2021, 24, 670–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.M. Leadership; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership and Performance; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Buil, I.; Martínez, E.; Matute, J. Transformational leadership and employee performance: The role of identification, engagement and proactive personality. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiar, A.; Wang, Y. The effects of transformational leadership and organizational commitment on hotel departmental performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 586–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Moorman, R.H.; Fetter, R. Relationship among leadership, organizational commitment, and OCB in Uruguayan. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 1990, 1, 107–142. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, E.; Zamani-Miandashti, N. The role of transformational leadership, organizational culture and organizational learning in improving the performance of Iranian agricultural faculties. High. Educ. 2013, 66, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.K. The Effects of Transformation Leadership, Organizational Culture, Job Satisfaction on the Organizational Performance in the Non-profit Organizations. Transformation 2008, 4, 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.J.; Park, S. Transformational leadership, knowledge sharing, organizational climate and learning: An empirical study. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 761–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Dhar, R.L. Transformational leadership and employee creativity: Mediating role of creative self-efficacy and moderating role of knowledge sharing. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 894–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Masood, M.; Umrani, W.A. The role of job crafting and knowledge sharing on the effect of transformational leadership on innovative work behavior. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 1186–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudibjo, N.; Prameswari, R.K. The effects of knowledge sharing and person–organization fit on the relationship between transformational leadership on innovative work behavior. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.B.; Kim, K.; Ullah, S.M.E.; Kang, S.W. How transformational leadership facilitates innovative behavior of Korean workers. Pers. Rev. 2016, 45, 459–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednall, T.C.; Rafferty, A.E.; Shipton, H.; Sanders, K.; Jackson, C.J. Innovative Behaviour: How Much Transformational Leadership Do You Need? Br. J. Manag. 2018, 29, 796–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanescu, D.F.; Zbuchea, A.; Pinzaru, F. Transformational leadership and innovative work behaviour: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Kybernetes 2021, 50, 1041–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepak, D.P.; Snell, S.A. The human resource architecture: Toward a theory of human capital allocation and development. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullen, A.; Simpson, R. Managing difference in feminized work: Men, otherness and social practice. Hum. Relat. 2009, 62, 561–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S. Transformational leadership and psychological empowerment. S. Asian J. Glob. Bus. Res. 2014, 3, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grošelj, M.; Černe, M.; Penger, S.; Grah, B. Authentic and transformational leadership and innovative work behaviour: The moderating role of psychological empowerment. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 24, 677–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhawi, A.K.; Cek, K. The Impact of Ethical Leadership on Environmental Performance in the Construction Industry: Mediating Role of Environmental Innovation and Innovation Climate. Manag. Account. Rev. 2024, 23, 85–132. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, V.R. Transformational leadership and personal outcomes: Empowerment as mediator. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2012, 33, 550–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abukhait, R.M.; Bani-Melhem, S.; Zeffane, R. Empowerment, knowledge sharing and innovative behaviours: Exploring gender differences. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 23, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B. The impact of person-organization fit on innovative work behavior: The mediating effect of knowledge sharing behavior. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2016, 29, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsawan, I.W.E.; Hariyanti, N.K.D.; Atmaja, I.M.A.D.S.; Suhartanto, D.; Koval, V. Developing Organizational Agility in SMEs: An Investigation of Innovation’s Roles and Strategic Flexibility. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmy, I.; Adawiyah, W.R.; Banani, A. Linking psychological empowerment, knowledge sharing, and employees’ innovative behavior in Indonesian SMEs. J. Behav. Sci. 2019, 14, 66–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rafique, M.A.; Hou, Y.; Chudhery, M.A.Z.; Waheed, M.; Zia, T.; Chan, F. Investigating the impact of pandemic job stress and transformational leadership on innovative work behavior: The mediating and moderating role of knowledge sharing. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandavasi, R.K.K.; McConville, D.C.; Uen, J.F.; Yepuru, P. Knowledge sharing, shared leadership and innovative behaviour: A cross-level analysis. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 1221–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidler-de Alwis, R.; Hartmann, E. The use of tacit knowledge within innovative companies: Knowledge management in innovative enterprises. J. Knowl. Manag. 2008, 12, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venketsamy, A.; Lew, C. Intrinsic and extrinsic reward synergies for innovative work behavior among South African knowledge workers. Pers. Rev. 2022, 53, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, C.T.; Garavan, T.N. Human Resource Development in SMEs: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. Transformational Leader Behaviors and Substitutes for Leadership as Determinants of Employee Satisfaction, Commitment, Trust, and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. J. Manag. 1996, 22, 259–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Umrani, W.A. Transformational leadership and innovative work behavior: The role of motivation to learn, task complexity and innovation climate. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 23, 402–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P.M. Social Exchange Theory; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, M.; Garavan, T.N.; Carbery, R. Innovation and human resource development (HRD). Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2013, 38, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann-Willenbrock, N.; Meinecke, A.L.; Rowold, J.; Kauffeld, S. How transformational leadership works during team interactions: A behavioral process analysis. Leadersh. Q. 2015, 26, 1017–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Beehr, T.A. Empowering leadership: Leading people to be present through affective organizational commitment? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 31, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, S.A.; Dani, S.S.; Burns, N.D.; Backhouse, C.J. Transformational Leadership and Organizational Culture: The Situational Strength Perspective. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. B J. Eng. Manuf. 2006, 220, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory, Organizational Behaviour and Human Performance. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1976, 16, 250–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.C.; Wang, D.S. Does supervisor-perceived authentic leadership influence employee work engagement through employee-perceived authentic leadership and employee trust? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 26, 2329–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennis, W.; Nanus, B. Leaders: The Strategies for Taking Charge; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Dirks, K.T.; Ferrin, D.L. Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edú-Valsania, S.; Moriano, J.A.; Molero, F. Authentic leadership and employee knowledge sharing behavior. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2016, 37, 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Willis, S.; Tian, A.W. Empowering leadership: A meta-analytic examination of incremental contribution, mediation, and moderation. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria Stock, R.; Zacharias, N.A.; Schnellbaecher, A. How Do Strategy and Leadership Styles Jointly Affect Co-development and Its Innovation Outcomes? J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2017, 34, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M.; Zhou, J. Dual tuning in a supportive context: Joint contributions of positive mood, negative mood, and supervisory behaviors to employee creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.; Kim, T. An integrative literature review of employee engagement and innovative behavior: Revisiting the JD-R model. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saira, S.; Mansoor, S.; Ali, M. Transformational leadership and employee outcomes: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 42, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minai, M.H.; Jauhari, H.; Kumar, M.; Singh, S. Unpacking transformational leadership: Dimensional analysis with psychological empowerment. Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 1419–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mufti, M.; Xiaobao, P.; Shah, S.J.; Sarwar, A.; Zhenqing, Y. Influence of leadership style on job satisfaction of NGO employee: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. J. Public. Aff. 2020, 20, e1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, I.A.; Farrukh, M.; Ahmed, N.O.; Lin, L.; Kanwal, N. The role of transformational leadership style, organizational structure and job characteristics in developing psychological empowerment among banking professionals. J. Chin. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 9, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamin, M.A.Y. Examining the effect of organisational innovation on employee creativity and firm performance: Moderating role of knowledge sharing between employee creativity and employee performance. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2020, 22, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, N. Knowledge sharing, innovation and firm performance. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 8899–8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soniewicki, M.; Paliszkiewicz, J. The Importance of Knowledge Management Processes for the Creation of Competitive Advantage by Companies of Varying Size. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2019, 7, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.F. A learning organization perspective on knowledge-sharing behavior and firm innovation. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2006, 25, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, M.; Koval, V.; Tepavicharova, M.; Zerkal, A.; Radchenko, A.; Bondarchuk, N. The interaction between the human resources motivation and the commitment to the organization. J. Secur. Sustain. Issues 2020, 9, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Ma, Z.; Yu, H.; Jia, M.; Liao, G. Transformational leadership and employee knowledge sharing: Explore the mediating roles of psychological safety and team efficacy. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 150–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Shang, Y.; Liu, H.; Xi, Y. Differentiated transformational leadership and knowledge sharing: A cross-level investigation. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Huang, Y.; Wu, J.; Dong, W.; Qi, L. What matters for knowledge sharing in collectivistic cultures? empirical evidence. J. Knowl. Manag. 2014, 18, 1004–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.U.; Bresciani, S.; Ashfaq, K.; Alam, G.M. Intellectual capital, knowledge management and competitive advantage: A resource orchestration perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 26, 1705–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, P.B.; Lei, H. Determinants of innovation capability: The roles of transformational leadership, knowledge sharing and perceived organizational support. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 527–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Choudhary, S.; Jain, S. Transformational leadership and knowledge sharing behavior in freelancers: A moderated mediation model with employee engagement and social support. J. Glob. Oper. Strateg. Sourc. 2019, 12, 202–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Paulus, P.B. CEO ideational facilitation leadership and team creativity: The mediating role of knowledge sharing. J. Creat. Behav. 2015, 49, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Zhang, L.; Shah, S.J.; Khan, S.; Shah, A.M. Impact of humble leadership on project success: The mediating role of psychological empowerment and innovative work behavior. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.E.; Wang, G.; Courtright, S.H. Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations: A meta-analytic review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 981–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Sarkar, A. Role of psychological empowerment in the relationship between structural empowerment and innovative behavior. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 42, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Yang, S.; Lv, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, S. Organisational innovation climate and innovation behaviour among nurses in China: A mediation model of psychological empowerment. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 2225–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottman, J.M.; Coan, J.; Carrere, S.; Swanson, C. Predicting Marital Happiness and Stability from Newlywed Interactions Published by: National Council on Family Relations Predicting Marital Happiness and Stability from Newlywed Interactions. J. Marriage Fam. 1998, 60, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermuly, C.C.; Meyer, B. Transformational leadership, psychological empowerment, and flow at work. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2020, 29, 740–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.U.; Zada, M.; Ullah, A.; Khattak, A.; Han, H.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Araya-Castilo, L. Servant Leadership and Followers Prosocial Rule-Breaking: The Mediating Role of Public Service Motivation. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 848531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A.; Freeman, W.H.; Lightsey, R. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. J. Cogn. Psychother. 1999, 13, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Pratt, M.G. The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations: Making progress, making meaning. Res. Organ. Behav. 2016, 36, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, S.H.; Zakariya, R.; Vrontis, D.; Santoro, G.; Christofi, M. High-performance work systems, innovation and knowledge sharing: An empirical analysis in the context of project-based organizations. Empl. Relat. 2021, 43, 438–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahaidak, M.; Tepliuk, M.; Dykan, V.; Popova, N.; Bortnik, A. Comprehensive Assessment of Influence of The Innovative Development Asymmetry on Functioning of The Industrial Enterprise. Nauk. Visnyk Natsionalnoho Hirnychoho Universytetu 2020, 6, 162–167. Available online: http://nvngu.in.ua/index.php/en/archive/on-the-issues/1854-2020/content-6-2020/5612-23(29) (accessed on 9 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Zavidna, L.; Makarenko, P.M.; Chepurda, G.; Lyzunova, O.; Shmygol, N. Strategy of Innovative Development as an Element to Activate Innovative Activities of Companies. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 18, 162–167. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Noe, R.A. Knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2010, 20, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, R.; Beh, L.S. Measuring and enhancing organisational creative climate, knowledge sharing, and innovative work behavior in startups development. Bottom Line 2019, 32, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.A.; Asif, J.; Waqar, N.; Khalid, S.; Abbas, S.K. The Impact of Knowledge Sharing on Innovative Work Behavior. Asian J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2018, 6, 2348–7186. [Google Scholar]

- Mura, M.; Lettieri, E.; Radaelli, G.; Spiller, N. Promoting professionals’ innovative behaviour through knowledge sharing: The moderating role of social capital. J. Knowl. Manag. 2013, 17, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Phillips, J.S. Examining the antecedents of knowledge sharing in facilitating team innovativeness from a multilevel perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2011, 31, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.H.; Nguyen, D.; Vo, N.; Tuan, L.T. Fostering Public Sector Employees’ Innovative Behavior: The Roles of Servant Leadership, Public Service Motivation, and Learning Goal Orientation. Adm. Soc. 2022, 55, 30–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaelli, G.; Lettieri, E.; Mura, M.; Spiller, N. Knowledge sharing and innovative work behaviour in healthcare: A micro-level investigation of direct and indirect effects. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2014, 23, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Leung, K.; Koch, P.T. Managerial Knowledge Sharing: The Role of Individual, Interpersonal, and Organizational Factors. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2006, 2, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T.; Tummers, L.; Teo, S.; Brunetto, Y. How servant leadership nurtures knowledge sharing. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2016, 29, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmieciak, R. Trust, knowledge sharing, and innovative work behavior: Empirical evidence from Poland. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 24, 1832–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riana, I.G.; Aristana, I.N.; Rihayana, I.G.; Wiagustini, N.L.P.; Abbas, E.W. High-Performance Work System in Moderating Entrepreneurial Leadership, Employee Creativity and Konwledge Sharing. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 21, 328–341. [Google Scholar]

- Tung, H.L.; Chang, Y.H. Effects of empowering leadership on performance in management team: Mediating effects of knowledge sharing and team cohesion. J. Chin. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 2, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological, Empowerment in the Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement and Validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. The Darker and Brighter Sides of Human Existence: Basic Psychological Needs as a Unifying Concept. Psychol. Inq. 2010, 11, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.I.; Chow, C.; Wu, A. The role of transformational leadership in enhancing organizational innovation: Hypotheses and some preliminary findings. Leadersh Q. 2003, 14, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Finegan, J.E.; Shamian, J.; Wilk, P. A longitudinal analysis of the impact of workplace empowerment on work satisfaction. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskyte, K. Transformational leadership, organizational culture, and innovativeness in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2004, 15, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BPS-Statistics. Statistical Yearbook of Indonesia. In Statistik Indonesia; BPS-Statistics: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, N.K.; Dhar, R.L. Transformational leadership, innovation climate, creative self-efficacy and employee creativity: A multilevel study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 51, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti, J.; Dev, M. The impact of transformational leadership on employee creativity: The role of learning orientation. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2015, 9, 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masta, N.; Riyanto, S. The Effect of Transformational Leadership, Perceived Organizational Support and Workload on Turnover Intention Sharia Banking Company in Jakarta. Saudi J. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2020, 5, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and Opinion on Structural Equation Modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, vii–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Editorial—Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance. Long Range Plann. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. Cross-Validatory Choice and Assessment of Statistical Predictions. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1974, 36, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Sarstedt, M. Goodness-of-fit indices for partial least squares path modeling. Comput. Stat. 2013, 28, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.D.; Usher, M.; McClelland, J.L. A PDP approach to set size effects within the Stroop task: Reply to Kanne, Balota, Spieler, and Faust. Psychol. Rev. 1998, 105, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaussi, K.S.; Dionne, S.D. Leading for creativity: The role of unconventional leader behavior. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 14, 475–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethibe, T.; Steyn, R. The impact of leadership styles and the components of leadership styles on innovative behaviour. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2017, 21, 1750015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Gong, C. Impact of open innovation communities on enterprise innovation performance: A system dynamics perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.C.J.; Huizingh, E.K.R.E. When is open innovation beneficial? The role of strategic orientation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 1235–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freixanet, J.; Braojos, J.; Rialp-Criado, A.; Rialp-Criado, J. Does international entrepreneurial orientation foster innovation performance? The mediating role of social media and open innovation. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2021, 22, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, M.; Martinez, M.G. Social Media: A Tool for Open Innovation. Muto, A., editor. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2014, 56, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroeger, A.; Weber, C. Developing a Conceptual Framework for Comparing Social Value Creation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2014, 39, 513–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. The future of open innovation. Res. Technol. Manag. 2017, 60, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Open Innovation: A New Paradigm for Understanding Industrial Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Spithoven, A.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; Roijakkers, N. Open innovation practices in SMEs and large enterprises. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 41, 537–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Wang, L.; Bi, Z.; Li, Y.Y.; Xu, Y. Cloud computing in human resource management (HRM) system for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 84, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Jones, B.M.; Kakabadse, N. Does strategic human resource management matter in high-tech sector? Some learning points for SME managers. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2008, 8, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, P.H. Knowledge sharing: Moving away from the obsession with best practices. J. Knowl. Manag. 2007, 11, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, M.; Afsar, B. Transformational leadership and innovative work behavior among nursing staff. Nurs. Inq. 2017, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminova, M.; Marchi, E. The Role of Innovation on Start-Up Failure vs. its Success. Int. J. Bus. Ethics Gov. 2021, 4, 41–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarysse, B.; Wright, M.; Van de Velde, E. Entrepreneurial Origin, Technological Knowledge, and the Growth of Spin-Off Companies. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 1420–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, R.; Liu, J. Can CEO’s humble leadership behavior really improve enterprise performance and sustainability? A case study of Chinese start-up companies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertxundi, A.; Barrutia, J.; Landeta, J. Relationship between innovation, HRM and work organisation. An exploratory study in innovative companies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2019, 19, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervishaj, V. Measuring IT Sector Innovations Capabilities through the Company Innovative Leadership Model. Econ. Altern. 2022, 28, 809–820. [Google Scholar]

- Kohtamäki, M.; Kekäle, T.; Viitala, R. Trust and Innovation: From Spin-Off Idea to Stock Exchange. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2004, 13, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turunen, P.; Hiltunen, E. Empowering Leadership in a University Spin-off Project: A Case Study of Team Building. S. Asian J. Bus. Manag. Cases 2019, 8, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; George, G. Absorptive Capacity: A Review Reconceptualization and Extension. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsawan, I.W.E.; Rajiani, I.; Suryantini, N.P.S. Investigating Knowledge Transfer Mechanism in Five Star Hotels. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 18, 22–32. Available online: https://pjms.zim.pcz.pl/resources/html/article/details?id=183867 (accessed on 9 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ployhart, R.E.; Vandenberg, R.J. Longitudinal research: The theory, design, and analysis of change. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 94–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, J.D.; Willett, J.B. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).