Abstract

Veterans living in rural areas of the United States face various health challenges that demand timely access to care to improve their well-being and quality of life. Telehealth (i.e., the use of telecommunications technology to connect people with care providers remotely) has become vital in addressing the accessibility gap for people constrained by vehicle ownership, income, geographic isolation, and limited access to specialists. This study aims to examine the current evidence on rural veterans’ use of telehealth for their healthcare needs, evaluates the cost savings associated with telehealth, as well as veterans’ use of telehealth during COVID-19. Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, a systematic search was conducted on three databases (Google Scholar, PubMed, and Scopus) to select relevant articles published from 2017 to 2023. A total of 36 articles met the inclusion criteria and were categorized into three objectives: veterans’ medical conditions managed through telehealth (n = 24), veterans’ transportation cost savings using telehealth (n = 4), and telehealth use during the COVID-19 pandemic (n = 8). The results indicated that telehealth is a viable option for managing various medical conditions of rural veterans, including complex ones like diabetes and cancer. Additionally, telemedicine was a useful platform in bridging the healthcare accessibility gap during disasters or pandemics like COVID-19 evident from its increased usage during the pandemic. Lastly, telehealth was associated with cost and time savings between USD 65.29 and USD 72.94 per visit and 2.10 and 2.60 h per visit, respectively. However, the feasibility of telehealth for veterans’ medical conditions such as rheumatism, cancer, HIV, and diabetes is underexplored and calls for further investigation post-COVID-19. Lastly, the limited literature on rural veterans’ transportation cost savings using different mobility options—taxi, Uber, public transportation, and rides from friends and family—is another critical gap.

Keywords:

rural veterans; telehealth; rural health; COVID-19; telemedicine; medical conditions; cost savings 1. Introduction

The use of telecommunications technology to deliver healthcare services and health education remotely is known as telehealth (TH). Telemedicine, which is like telehealth, allows healthcare providers to evaluate, diagnose, and treat patients from a distance without needing to visit a physical clinic or hospital. These terms have been used interchangeably in the literature. Telehealth can be traced back to the 19th century, when the telephone was used to minimize unnecessary office visits. In 1925, the cover of Science and Invention magazine depicted a doctor diagnosing a patient via radio, envisioning a device that could facilitate video examinations over long distances [1]. Since then, telehealth has undergone many improvements, and its use has been implemented worldwide, making it particularly beneficial for individuals in remote or underserved areas. Telehealth usage is not unique in the United States (U.S.), as this technology has been used over the years for medical consultations, education, and wartime communications [1]. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), for example, operates one of the largest telehealth programs in the United States, serving nearly 3 million rural veterans annually [2]. Using video conferencing, remote monitoring, and other telecommunications devices, telehealth enables healthcare providers to deliver care remotely, allowing for synchronous and asynchronous interactions. This flexibility will enable veterans to access specialists and services that may not be available locally, especially in rural areas where healthcare provider shortages are prevalent.

Studies on telehealth have been conducted across both developed and developing countries, highlighting its global impact. For instance, a study conducted in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that sociodemographic factors and previous familiarity with the technology influenced telehealth usage [3]. In the U.S. and Africa, during the COVID-19 pandemic, mobile applications were instrumental in informing patients about referrals, coordinated care and concerns, and facilitating access to routine care without the risk of exposure through close contact [4,5]. Additionally, telehealth significantly expanded its role, transforming the provision of outpatient evaluation and management services to accommodate social distancing requirements [6]. Research focused on diabetic patients emphasized the critical role of telehealth in diabetes care, noting that it reduced hospitalizations by 50% while increasing patient engagement in self-management and glycemic control [7,8]. These examples underscore the adaptability and effectiveness of telehealth in diverse healthcare settings.

Furthermore, numerous studies have explored various demographic aspects of telehealth, including ethnicity, gender, geographic location (rural, urban, or suburban), and the health of rural older adults [9,10,11,12]. Other studies have examined the potential for distance and cost savings, with evidence suggesting that telehealth reduces the average miles traveled for in-person care [13,14]. Narrative reviews that examined the recent application of telehealth in rural areas in the U.S. highlighted the acceptability and enhanced satisfaction as well as the efficiency and convenience of its use [15]. Rangachari et al. [16] established that telehealth adoption and usage vary significantly across different medical specialties in the United States. These highlight telehealth’s broader applicability and benefits in enhancing healthcare delivery.

However, while these studies provide valuable insights, they often focus on general populations or specific conditions, leaving other populations (veterans) underexplored. By focusing on the medical conditions that rural veterans prioritize telehealth for, the use of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic, and telehealth benefits of reduced transportation costs, this review seeks to fill critical gaps in the current understanding of telehealth’s impact on rural veterans’ healthcare in the U.S. and suggest ways that it could be optimized to benefit rural veterans. This review consolidates existing knowledge and offers new insights that can inform future research and healthcare policy for rural veterans.

The objectives of this study are as follows: (1) To identify the medical conditions for which rural veterans prioritize telehealth to meet their needs. This objective will shed light on veterans’ medical conditions that telehealth has effectively addressed and the ones that have not been explored with telehealth. (2) To analyze the use of telehealth by veterans in rural United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. This objective will investigate the efficiency of telehealth during COVID-19, when social distancing and quarantine restrictions were imposed alongside the transportation staff shortage. (3) To synthesize studies on transportation cost savings using telemedicine and how it improves the quality of care for rural veterans in the U.S.

The rest of this paper is organized in this order: Section 2 will cover the SLR method, which includes the Search strategy and the PRISMA flow chart. Section 3 highlights the study’s key findings. Section 4 discusses the results. Section 5 addresses the gaps in the literature and the study’s limitations. Lastly, Section 6 concludes this review and provides future research directions and potential strategies to overcome telehealth barriers.

2. The Systematic Literature Review

To meet the objectives of this study, the Systematic Literature Review (SLR) methodology was deemed appropriate. The SLR is a systematic, transparent, and repeatable approach for recognizing, analyzing, and synthesizing the literature currently published by scholars, academics, and researchers [17]. This aids researchers in gathering relevant articles, documents, and published works based on the criteria set out for this study [18]. This review repeated the guidelines outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) as shown in Supplementary Table S1.

2.1. Literature Search

The researchers downloaded peer-reviewed works from 2017 to 2023 from three databases—Scopus, Google Scholar, and PubMed—from April to December 2023. (1) Scopus contains a comprehensive collection of abstracts and citations from scientific journals, conference proceedings, and books, and it is meticulously curated and covers contents that were the focus of this review; (2) Google Scholar grants access to a vast array of the scientific literature from journals, books, conference proceedings, and covers diverse topics including telehealth; (3) PubMed is widely recognized for its high-quality, comprehensive, and relevant articles in the field of health and medical sciences. Additionally, searching specialized databases (PubMed) complemented searches conducted on multidisciplinary research platforms like Scopus and Google Scholar [19] because of their comprehensive coverage and relevance to telehealth. All these databases were chosen to ensure the feasibility and efficiency of the review process, thereby minimizing database selection biases [15,20,21].

2.2. Search Strategy

This study has three objectives; hence, three different search strategies were adopted to find relevant papers that met the inclusion criteria for this study from the three databases mentioned above. The Booleans OR/AND were joined with key terms to increase the search results and find relevant papers. The authors screened for appropriate articles that met all three objectives. During the screening process, articles were limited to the English language, focused on the United States, rural veterans, article title, abstract, and keywords (except for Google Scholar where the authors used the advanced search tool to filter anywhere in the articles for the search keywords and with at least one of the words in the title selection), and publication date (2017–2023) except for objective 2 (2020–2023). Furthermore, the selected literature for the analysis followed the SPIDER format for answering the research questions and were read fully.

Study Selection and the Booleans

For the first objective, the following keywords were used (“telehealth” OR “telemedicine”) AND (“veterans” OR “retired military officers”) AND (“United States” OR “U.S.”) AND (“rural” OR “remote”). This returned a total of 55,075 articles (Google Scholar = 54,200, PubMed = 358, and Scopus = 517) covering telehealth or telemedicine studies, rural and urban areas, the United States and across the world from three databases. Using the advanced search (included country—United States or US, location—rural in the original search terms) returned 14,000 articles and, when filtered with date custom range (2017–2023), returned 7650 articles for Google Scholar. Google Scholar singled out ProQuest, Books which were not the focus of this review and hence were not downloaded. In an instance, where the title aligned with the search terms, the authors clicked on the link to read the abstract to consider an article. From this process, the authors downloaded 423 articles from the databases using the inclusion criteria. The search terms and results from the databases can be found in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Search terms for the three objectives.

Table 2.

Search results for the objectives from the selected databases with filters.

For the second objective, the search was conducted from 2020 to 2023 since the COVID-19 pandemic started in late 2019. This generated 20,188 articles (Google Scholar = 20,100, PubMed = 57, and Scopus = 31). Using the custom date range (2020–2023) returned 5400 articles for Google Scholar. Also, Google Scholar provided Books, ProQuest information, which was easy to screen; hence, such materials were not downloaded. The authors were guided by the inclusion criteria to download relevant articles from the databases for final screening and analysis. In total, two hundred and twenty-four articles passed and were downloaded for further screening. After removing duplicates and thorough screening and discussions with the authors, 56 relevant articles remained for full-text reading. During the full-text reading, 8 articles remained for final analysis.

Using the search terms for objective 3, 30,399 articles (Google Scholar = 30,300, PubMed = 49, and Scopus = 50) were returned. Filtering using the advanced search terms and the date range (2017–2023) returned 7330 articles. The authors screened articles on the 3 databases using the inclusion criteria to download relevant articles. Two hundred and seven articles were downloaded for the final screening. The number of articles that remained for final analysis can be found in Figure 1.

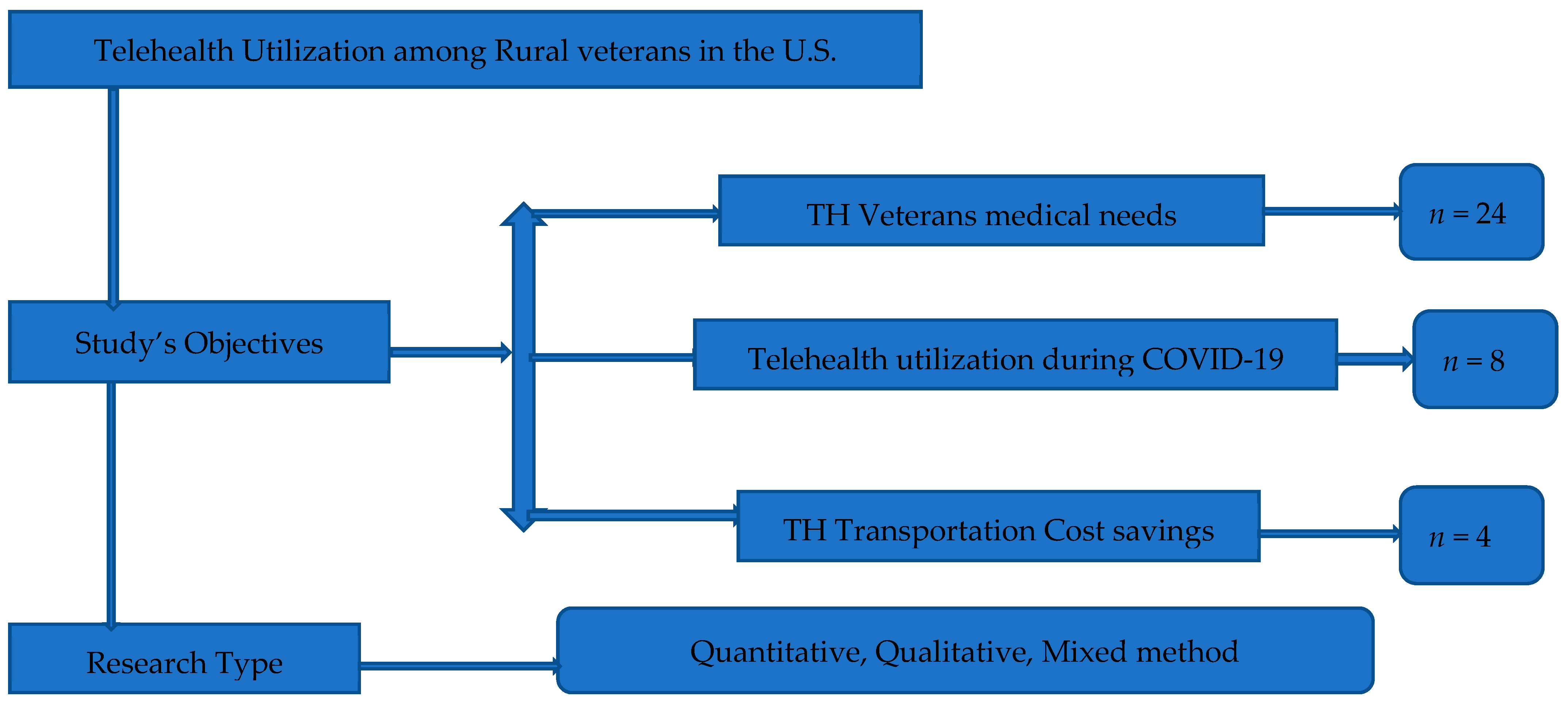

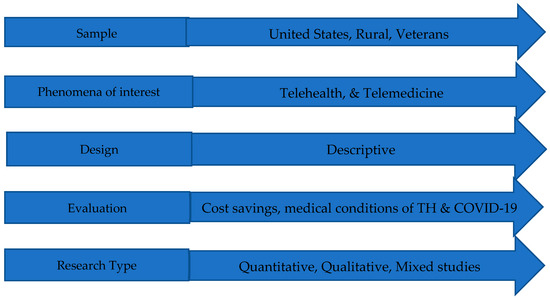

Figure 1.

Researchers’ design. Objectives from the study and the number of selected papers for objective.

2.3. Study Eligibility Criteria

The following steps were adopted to screen articles that fit the study’s objectives for analysis.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

For a study to be included in this review [22,23,24], the authors searched for studies with telehealth or telemedicine in the title, abstract and keywords, studies written in English, published between 2017 and 2023, focused on the United States, specifically on veterans in rural areas, and peer-reviewed. Figure 1 details this in the SPIDER question format for this review. Papers published before 2017 and after 2023, not focused on the U.S., or not centered on rural veterans were excluded from the screening [3,4,13]. Also, dissertations, grey literature, non-full articles, and unpublished studies were not considered for screening. Figure 2 shows the number of articles per objective that met the inclusion criteria and the research type of the selected articles.

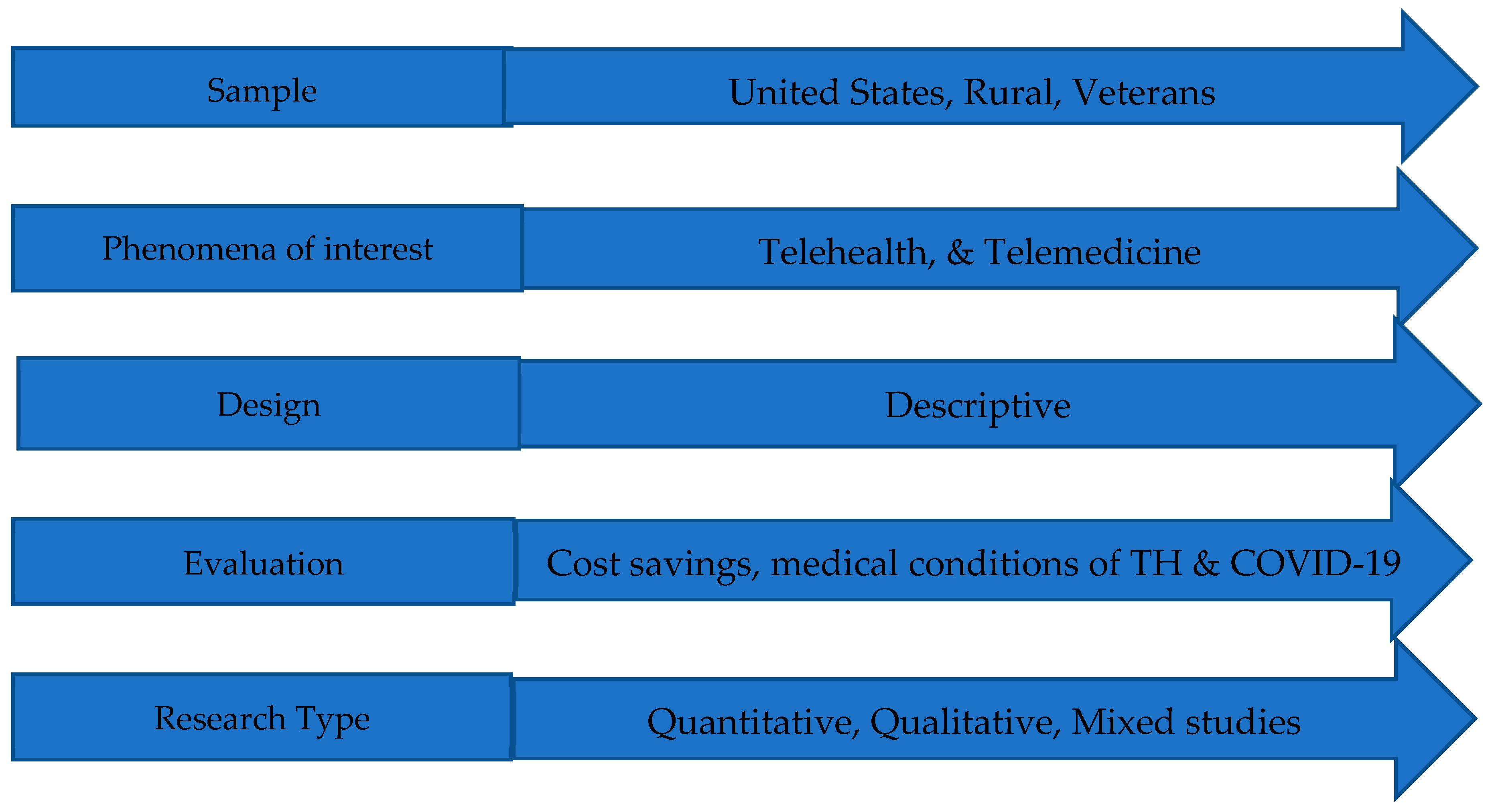

Figure 2.

SPIDER question format used for the study’s analysis.

2.4. Study Selection

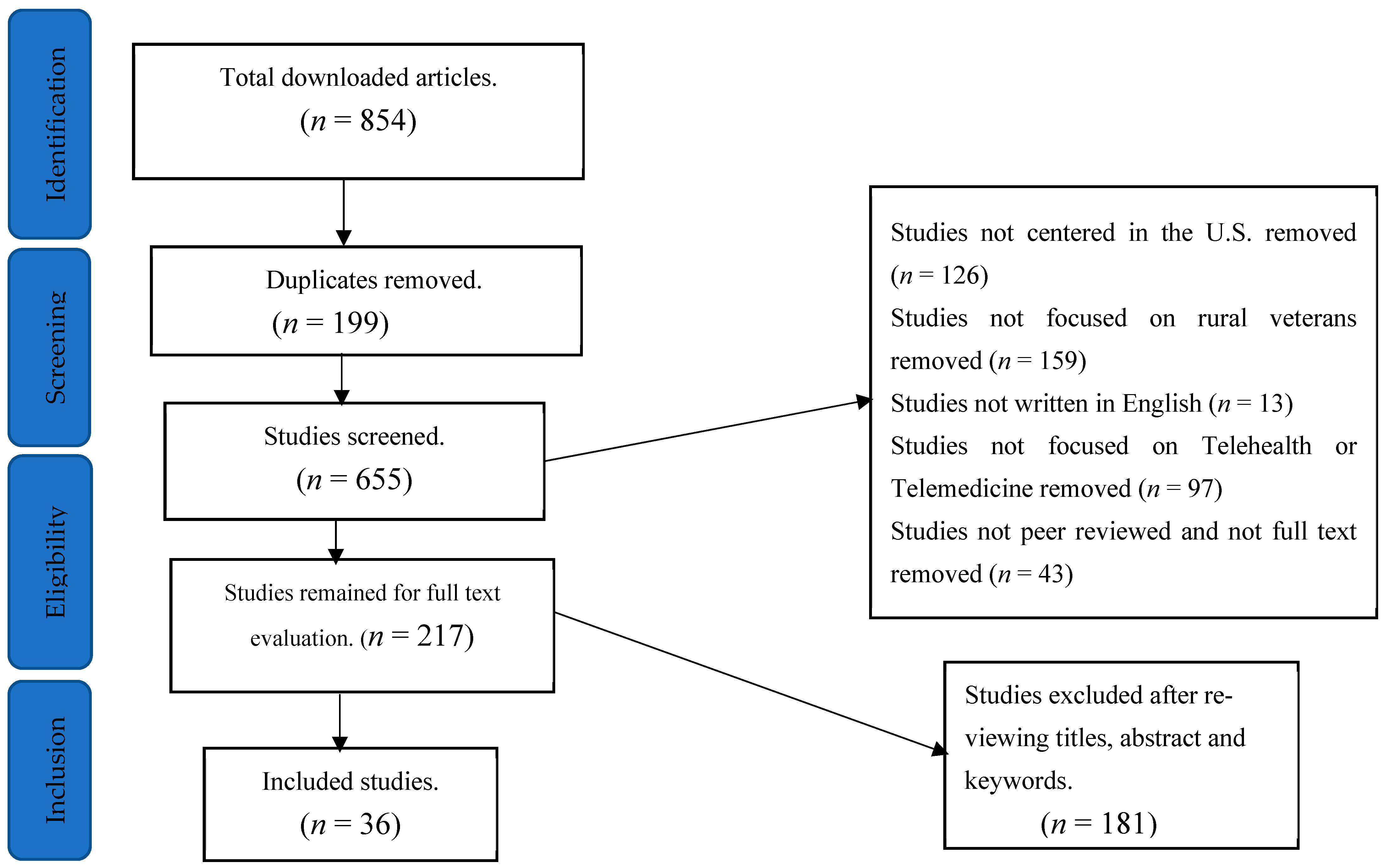

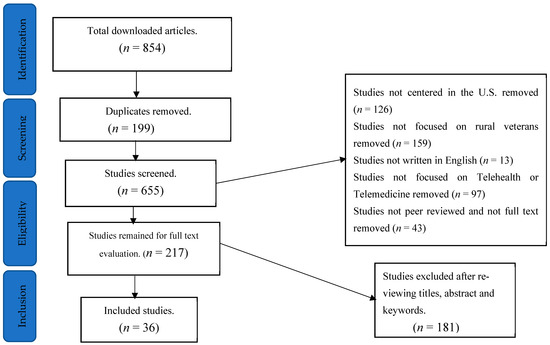

To thoroughly analyze this study, 854 articles based on the objectives were downloaded from the electronic databases (Google Scholar, PubMed, and Scopus). The PRISMA flow chart illustrated the process of selecting articles for analysis. The process included screening for titles, keywords, abstracts, and full-text reading. Using Mendeley reference manager software, 199 duplicate articles were removed. One hundred and twenty-six studies were removed because the focus was not on the United States. An additional 97 studies were deleted because they were not focused on telehealth or telemedicine, and 13 articles were deleted because they were not written in English. One hundred and fifty-nine studies were removed from the remaining articles because they were not focused on rural veterans. A total of 43 studies were not peer-reviewed and were removed. Two hundred and seventeen articles remained for full-text review. The authors thoroughly reviewed the 217 studies and discussed the final articles to be included in the analysis. First, 3 groups of two people per group were formed to screen all the remaining 217 papers. Each group worked on all the papers and categorized them to their respective objectives based on the inclusion criteria. After 2 months of full screening, each group forwarded its selected articles to BQ. Three members at North Dakota State University met and deliberated on the selection. In an instance where 2 papers were found in two groups but were not listed in the third group, JM was consulted to resolve it. BQ forwarded the final list to IDB and RB for their input. They suggested a Zoom meeting for discussion and final selection. After deliberations, a total of 181 articles were removed because they did not align with the study’s objective, title, search key terms, and abstract. Thirty-six relevant articles were deemed eligible for full-text reading and final evaluation. Figure 3 presents the PRISMA flow chart- the process for screening the relevant studies for analysis.

Figure 3.

The PRISMA flow chart.

3. Results of This Study

Based on the study’s research objectives, the following findings were discovered from the review. The findings are explained in detail in the following sections.

3.1. Medical Conditions of Veterans and Telehealth Use

Telehealth has been used to address many medical conditions. Several studies have found it effective in treating or monitoring several health conditions. This section provides insight into our first objective.

3.1.1. Geriatrics

Pimentel et al. [25] studied ways to enhance rural veterans’ access to geriatrics telemedicine specialty care and concluded that telemedicine specifically tailored for geriatric care could support rural Community-Based Outpatient Clinics (CBOCs) in managing a growing number of elderly veterans with complex medical needs. The authors mentioned the lack of clinic space, unreliable internet for telemedicine visits, and staffing challenges leading to a lack of familiarity with telemedicine services for older veterans as challenges using telemedicine. A study that focused on using telehealth to increase healthcare access for older rural veterans [26] stated that due to the aging population and rising medical complexity, ensuring access to suitable and well-coordinated healthcare, particularly in rural and remote regions, is crucial for tackling healthcare inequalities. The authors concluded that telehealth is feasible and effective in providing elderly veterans with expert geriatric consultations in remote locations. Furthermore, Lum et al. [26] mentioned telehealth’s benefits to include reducing travel times, minimizing transportation costs, improving healthcare accessibility, allowing for speedier diagnoses, and managing complex health concerns. Lastly, integrating geriatric telehealth services into current clinical workflows to transcend turnover, VHA investments in telehealth infrastructure, training, and agreed policies were some implementation strategies suggested for effectively utilizing telehealth among this population.

3.1.2. Mental Health

Several studies have focused on mental health (n = 9). Those studies found that video telehealth had the potential to improve healthcare access for both mental health patients and their providers [22,27] as well as increase the potential for treatment outside of the therapy room [28]. The authors found that less research has examined telehealth’s impact on other aspects of diversity like race, gender, and disability. In addition, telehealth’s impact has been explored in trauma-exposed veterans using a mixed-method approach [29,30]. The authors revealed that combining internet-based content and coaching was a promising solution for trauma-related problems and better social functioning, emotional regulation, and interpersonal relationships. However, to evaluate telemedicine effectiveness, the authors opined that the blended approach must be experimented with diverse veteran populations, including women and veterans residing in rural and underserved regions. Using clinical video telehealth (CVT) for dementia veterans, it was established that CVT provided dementia and long-term care services and support for rural older veterans [31,32]. Another study that focused on using telehealth-based creative arts therapy [33] concluded that using CVT could help in the successful implementation of the mental health and rehabilitation care program by ensuring that veterans receive continuous care and support even when they are not physically visiting their providers. Conversely, Levy et al. [33] stated that future research should include randomized, controlled clinical trials as well as the inclusion of creative arts therapy modules—music and drama therapies—to enrich the body of evidence.

Lastly, Campbell et al. [34] highlighted the importance of social support in influencing treatment outcomes through telemedicine-based collaborative care for PTSD.

3.1.3. Sleep Care

Recent studies reported that the telesleep program positively impacted veterans’ health and overall quality of life and has also been successful in alleviating the travel demands for veterans in need of sleep care [35,36,37]. The respondents (veterans) stated that telehealth alleviated barriers such as distance, travel time, and geographic location, which impeded healthcare access. To expand access to care, patients suggested improvements in scheduling, ensuring continuity and timeliness of communication, and streamlining the process for equipment replenishments [35].

3.1.4. Diabetes

Baum et al. [23] stated that the widespread utilization of telehealth is a testament to managing diabetes mellitus (DM) in rural communities since the first year of the pandemic. The study aimed to examine the change in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels among veterans with type 1 or type 2 diabetes who had not previously utilized telehealth services for diabetes management offered by the Community Provider Partnership (CPP) but began using them due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors found that the rapidly implemented telehealth management of DM by VA CPPs improved HbA1c control in 84.2% of patients. During the same period, a little over 10% of patients saw improvement in their conditions and were taken off metformin. Baum et al. [23] further mentioned an increase in veterans’ participation in full video consultations, owing to the provision of VA-issued tablets and enhanced technological education and support provided by VA staff. Contrary to the above findings, the authors stated the inability to account for potential confounding factors—food shortages, closing, or limited access to gymnasium or other physical recreational facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic—might have influenced the study’s outcomes.

3.1.5. Chronic Pain and Illness

Studies (n = 4) have examined chronic pain care among rural veterans and caregivers’ appraisal of chronic illness of both enrolled and non-enrolled veterans in the home telehealth (HT) program. Authors in ref. [14,38] found that using telehealth for pain care was promising in preventing suicide among veterans and enhancing opioid safety and offered the opportunity to incorporate training and support programs for chronically ill patients. In addition, telehealth converted most in-person visits to virtual encounters, increasing the number of participants for evidence-based study. Silvestrini et al. [39] examined the acceptability of receiving pain management via a telehealth program and found that patients were satisfied with receiving pain care through telehealth and that having supportive and knowledgeable providers made a difference in their conditions. They concluded that providing pain management services via telehealth suited this group of patients. Lum at al. [26] established that telehealth led to improved access to healthcare, timelier diagnosis, and the management of complex conditions, as well as reduced drive times and transportation costs. Conversely, patients indicated a strong preference for face-to-face meetings with their providers over telehealth appointments [39]. The preference for in-person care highlighted a gap in patient acceptance and satisfaction with telehealth as a substitute for traditional in-person visits.

3.1.6. Palliative Care

A focus group study aimed at exploring palliative care services for rural veterans with non-malignant respiratory diseases and their family caregivers revealed that using telemedicine platforms was beneficial for providing palliative care virtually [40]. Also, using an interactive digital platform for rural veterans might offer the best means of delivering effective, all-encompassing care to places where palliative services are scarce.

3.1.7. Antimicrobial and Fracture Prevention

Stevenson et al. [41] conducted an antimicrobial stewardship pilot study and concluded that telehealth was feasible in supporting antimicrobial stewardship, especially in rural areas with a lack of local infectious disease experts. Miller et al. [42] investigated fracture prevention services for veterans through telemedicine. They found that comparing health efforts for veterans to that for other populations, the Bone Health Team model is a feasible telehealth approach to address bone health in a rural veteran population. Furthermore, the study demonstrated a significant use of prescription drugs for care due to telehealth access. This study was limited as not all staff participated in the interviews, thereby affecting the impact of these qualitative research findings.

3.1.8. Clinical Pharmacy

Clinical pharmacy services include pharmacists who provide pharmacy services to patients and other medical professionals to improve pharmaceutical therapy and patient outcomes. The services include medication therapy management and reconciliation, patient education, adherence counseling, and drug interaction and side effect monitoring. Perdew et al. [43] used clinical video telehealth to provide clinical pharmacy services to over 1000 veterans with diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and other chronic conditions. Telehealth was found to be a cost-effective and positively accepted method for delivering pharmacy services in remote areas. Another study by Litke et al. [44] mentioned that using telehealth to provide comprehensive medication management services in primary care improved disease management and facilitated healthcare access for rural veterans. They found a significant improvement in diabetes, hypertension, lipid management, and tobacco cessation. This study used both clinical video telehealth and telephone encounters.

3.1.9. Cancer Care

Telehealth has not been extensively utilized in cancer care for veterans in general and rural veterans, despite telehealth’s advantages of reducing traveling time and cost savings for users [45]. Jiang et al. [45] mentioned the limited access to devices and the internet, as well as understanding how to operate telehealth equipment, as some of the challenges that hinder the effective use of telehealth for cancer care. They also suggested the incorporation of telehealth into oncology, evaluating the satisfaction of veterans using telehealth, and ways to overcome the challenges mentioned above as a roadmap for future research.

From the above review, telehealth has been used to address diverse medical needs, including complex conditions such as mental health, antimicrobial, and fracture prevention and it has proven to be effective in treating and managing such conditions. However, challenges such as staffing, equipment and internet access remain a challenge in using TM among rural veterans. In addition, there are other conditions, such as cancer and rheumatism [45,46], which have been successful with other populations but have not been explored much by rural veterans. Future studies should address these challenges and explore these conditions with rural veterans.

3.2. Veterans’ Use of Telehealth During COVID-19

This section addresses the second objective, which examines the impact of telehealth use during COVID-19, especially when there was a shortage of transportation staff and limited access to public transit to healthcare services. Haverhals et al. [24] used inductive and deductive approaches to assess changes to offer safe and effective healthcare to veterans living in rural Medical Foster Homes (MFHs) and non-VA homes during the early stages of the pandemic. They found that care providers and coordinators intensified their phone communication in dealing with vulnerable populations during the pandemic. Also, using the telephone, various education sessions were carried out between coordinators and home-based primary care providers to minimize the spread of the virus. This resulted in increased telehealth visits during the pandemic, as the telephone was used to create supportive connections with caregivers through communication, which minimized social isolation. Despite the valuable care provided by MFH caregivers, the lack of respite support for MFH caregivers was identified as a challenge to ensuring the sustainability and effectiveness of the MFH program. Similarly, Baum et al. [23] observed that most rural patients benefited from telehealth care provided by the Community Provider Partnership (CPP) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, a qualitative study conducted through phone interviews with rural older veterans indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic had little negative impact on their physical and mental health when veterans used telehealth [47]. They further stated that telehealth offered resilient characteristics as protection to these high-risk older veterans during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, challenges such as limited technology and internet connectivity were highlighted as constraints to using TH during the pandemic. Furthermore, this study was limited to a single VA Medical Center; hence, there is a need to extend its coverage to allow for a solid generalization of its findings.

Gujral et al. [48] evaluated the relationship between the mass distribution of video-enabled tablets during the COVID-19 pandemic and rural veterans’ mental health service and telehealth’s effectiveness for suicide-related outcomes. They found that receiving a video tablet was linked to higher utilization of mental health services through video, increased psychotherapy visits (across all modes), and a decrease in suicide attempts and visits to the emergency department. In contrast, Gujral et al. [48] underscored the importance of conducting further research to distinguish tablet interventions’ specific impact from the pandemic’s broader influences. Hale-Gallardo et al. [49] studied Whole Health coaches at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) during the pandemic. They found that the utilization of telehealth technologies by Whole Health coaches helped maintain remote connections with rural veterans, particularly during lockdowns and social distancing restrictions. The authors further stated that the swift rollout of telehealth services, including the transition from telephone to video telehealth platforms such as Veterans Video Connect (VVC), guaranteed continuous availability of Whole Health coaching for rural veterans amidst the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, Ferguson et al. [50] studied the shift from in-person to virtual care within VA during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic and found that over 50% of VA care was delivered virtually, a significant increase from the previous 14%. Also, veterans with greater clinical or social requirements were more likely to utilize virtual services during this period.

Lastly, LeBeau et al. [51] found that telehealth increased veterans’ participation rather than relying on in-person delivery during the pandemic. They also noted that telehealth overcame geographic barriers in accessing healthcare and that TM enhanced flexibility and convenience to care. Table 3 highlights the most important findings of TH’s impact during COVID-19.

Table 3.

Telehealth use during the pandemic.

Despite these studies examining telehealth’s impact during COVID-19, no study examined telehealth and transportation staff shortages during the pandemic.

3.3. Cost–Benefit Analysis

Using our outlined search criteria for objective three on the cost–benefit or cost savings analysis of telehealth in rural areas by veterans, four (n = 4) studies met the inclusion criteria. Two studies each were published before and after the pandemic. The findings were relevant to ascertain the economic implications (cost savings) of telehealth for both veterans and the VA and how telehealth usage could contribute to the overall well-being of veterans.

In a retrospective chart review of rural veterans enrolled at the Atlanta endocrinology telehealth clinic, Xu et al. [52] found that patients saved 78 min in one-way travel time per visit, and there was a VA cost savings of USD 72.94 per veteran per trip. Also, there were close to 90% of scheduled appointments via telehealth by patients. The authors concluded that using telehealth for specialty diabetes care was linked with cost savings, time savings, and high rates of healthcare appointments. Another study that examined Travel Cost Savings and Practicality for Low-Vision Telerehabilitation, Ihrig [53] found that close to a quarter (25%) of low-vision patient care was increased using local telerehabilitation. The study further revealed a median travel distance saving of 122 miles per veteran and a median travel time saving of 2.10 h, reflecting a travel cost saving of USD 65.29 per trip. Ihrig [53] concluded that future cost-saving technology can be utilized for consultations with a low-vision optometrist and blind rehabilitation therapist. In addition, Baum et al. [23] revealed that over half (52%) of patients had to travel more than 50 miles in a round trip for in-person diabetes management care before the pandemic. Furthermore, a post-COVID-19 home sleep apnea study revealed travel avoided of 21.57 miles on average over 5 years through telehealth [36]. The authors stated that further investigation is needed to understand the travel burden, changes in healthcare delivery trends, the long-term effects of the pandemic, and increased community care access on healthcare utilization.

This implies that aside from telehealth’s advantage of accessing and scheduling healthcare appointments remotely, it also provided potential benefits such as travel time savings ranging from 2.10 h to 2.60 h per visit, travel distance saving from 21.6 to 122 miles, and cost saving of USD 65.29 to USD 72.94 per visit compared to in-person appointments. Also, these studies used travel rates of USD 0.415 and USD 0.535, representing VA and IRS rates per mile, respectively. However, these analyses did not capture veterans who used other mobility options such as taxis, Uber, and rides from family and friends. A post-COVID-19 analysis could capture these options to address the cost savings and benefits of telehealth for veterans residing in rural areas.

3.4. A Comparative Analysis of Telehealth Use Pre-Pandemic and Post-Pandemic

Rural veterans have demonstrated an increased utilization of telehealth services before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies have shown a general rise in telehealth use among rural and urban veterans during the pandemic, with a notable increase observed specifically among rural veterans [47,54]. While there have been noted disparities in video telehealth usage for mental health treatment between rural and urban veterans, the pandemic has led to a surge in telehealth use among rural veterans [55]. Initiatives such as the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) Connect program have been implemented to broaden access to telehealth services for older rural veterans and enhance care delivery [56]. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has been at the forefront of expanding telehealth to enhance access to care for veterans in rural areas post-pandemic, with programs like Telesleep focusing on improving access to specialty care [37,48].

3.5. A Comparative Analysis of Rural Veterans’ Use of Telehealth in the U.S. and Other Countries

Telemedicine use started in the U.S. before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, in the context of Africa, TH was recognized during the pandemic, and few details of telehealth and modes of delivery are documented [57]. A comparative analysis of telehealth use by rural veterans in the United States and other regions is necessary to examine the progress made and barriers encountered to enhance efficient care delivery. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has pioneered telehealth adoption initiatives like the Virtual Integrated Patient-Aligned Care Teams (V-IMPACT), to increase veterans’ access to primary care, especially in rural areas [46,47,58]. Additionally, the VA, through its telehealth programs, has extended specialist services like TelePain and Tele-neurology to remote areas in the U.S. [39,59]. The Medicare telehealth before and after COVID-19 has facilitated seamless interstate and in-home telemedicine services for veterans [60]. Studies have shown an increase in telehealth utilization among rural veterans, especially for mental health services following the COVID-19 pandemic [61,62].

In comparison, the EU and other countries have also been actively exploring telemedicine for veterans and rural populations. For example, Norway has been monitoring telemedicine use in hospitals to improve healthcare delivery [63]. In Iran, mental telehealth services have improved mental healthcare accessibility for veterans [64], and in Africa, mobile applications were used to schedule routine care during COVID-19 [4]. Furthermore, the EU is using telehealth to provide palliative care for veterans with respiratory diseases in rural areas [40]. Overall, both the U.S. and other countries have recognized the potential of telemedicine in improving healthcare access for rural veterans. While the VHA in the U.S. has made significant strides in telehealth adoption and service delivery, efforts are ongoing to address disparities and enhance the sustainability of telemedicine practices. Similarly, countries in the EU and beyond are exploring telehealth solutions to bridge gaps in healthcare access for veterans in rural areas, emphasizing the importance of telemedicine in transforming healthcare delivery for the rural population.

4. Discussion

This section will highlight the major components of this review based on previous and existing studies, challenges, research gaps, and limitations. Telehealth has a long-standing history, but its application has evolved rapidly, especially in COVID-19, where it became a lifeline for many patients. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA), which operates one of the largest telehealth programs in the U.S., has demonstrated that telehealth is an alternative and a necessity for improving access to care for rural veterans who otherwise face geographical and logistical barriers.

4.1. Medical Conditions

One of the key contributions of this review is the identification of medical conditions where rural veterans benefit the most from telehealth services. This review highlights the high utilization of telehealth for geriatric care, diabetes management, chronic pain, and mental health services. These areas align with the most pressing health concerns in rural veteran populations [25,65], many of whom face transportation challenges, limited access to healthcare facilities, and disabilities that impede mobility [66,67]. Furthermore, comparing this study to other telehealth reviews, rural veterans face more health challenges than non-rural veterans [47,68]. For instance, this review found and categorized nine medical conditions compared to a similar review that identified five medical conditions, which were diabetes, HIV, mental disorder, epilepsy, and cancer [69]. Additionally, veterans’ preference for in-person visit vs. telehealth [39] warrants further investigation as the authors of [51] opined that video telehealth was insufficient in managing rural veterans’ medical conditions and suggested that varied modalities be used based on veterans’ needs and preferences. This is consistent with earlier studies that called for further comparison between face-to-face care and telehealth [70,71] to ascertain which option is most effective in meeting veterans’ needs. This study’s findings point out that telehealth is a viable option for managing various medical conditions among rural veterans, including complex ones like diabetes and cancer. Also, telehealth has successfully reduced the need for physical travel, improving health outcomes and enhancing patient satisfaction.

4.2. Telehealth Use During COVID-19

Telemedicine served as a useful platform in bridging the healthcare accessibility gap during disasters or pandemics like COVID-19, evident from its increased usage during the pandemic. This spike in utilization was critical for mitigating the risk of virus exposure while ensuring continuity of care [72,73]. The deployment of video-enabled tablets and other telehealth devices for mental healthcare allowed veterans to access psychotherapy services and medication management more readily [74,75], which was linked to a reduction in emergency department visits and suicide attempts [48]. While the pandemic catalyzed the rapid adoption of telehealth during the COVID-19 [76,77] when lockdown and social distancing restrictions were in force, there is no study that has investigated telehealth’s impact during COVID-19 and transportation staff shortage. This calls for a new study to examine this gap.

4.3. Telehealth’s Cost Savings

Another important outcome of this review is the potential for telehealth to generate significant transportation cost savings. Multiple studies demonstrated that telehealth reduced both travel distance and costs, benefiting not only the veterans but also the healthcare system [78,79], which is consistent with our findings (USD 65.29 to USD 72.94 per trip and up to 122 miles in some cases). These studies used travel rates of USD 0.415 and USD 0.535, representing VA and IRS rates per mile, respectively. However, these analyses did not capture other veterans who used mobility options such as taxis, Uber, and rides from family and friends. A post-COVID-19 analysis could capture these options to address the cost savings and benefits of telehealth for veterans residing in rural areas. Lastly, these findings reinforce the economic efficiency of telehealth, especially for rural veterans who often need to travel great distances for specialized care.

4.4. Challenges in Telehealth Implementation

Despite the significant impact telehealth has made on the lives of rural veterans, it is also confronted with some challenges.

4.4.1. Technical and Logistical Barriers

Several studies pointed out significant challenges in the adoption of telehealth, particularly for older veterans [35,39,45] in rural areas. These challenges include limited access to technology, a lack of clinic space, unreliable internet connectivity, and staffing issues that resulted in a lack of familiarity with telemedicine services and access to broadband infrastructure [22,25,44,45,47,51].

4.4.2. Patient and Provider Barriers

The review highlighted some patient and provider barriers to the effective use of telehealth for cancer care among veterans. These include access to devices and understanding how to operate telehealth equipment [45]. Additionally, the preference for in-person care remained a significant challenge, revealing a gap in patient acceptance and satisfaction with telehealth as a substitute for traditional in-person visits [39,45]. The lack of respite support for Medical Foster Home (MFH) caregivers was noted as a challenge to ensuring the sustainability and effectiveness of the MFH program [24]. Lastly, program follow-up, negative perceptions of mental healthcare for pain, and preference for in-person care were identified as barriers to telehealth use [32,39].

5. Gaps in the Literature and Limitations of the Study

This review identified several gaps in the literature. For instance, some medical conditions have been successful with telehealth in other populations, but telehealth’s role in cancer care and other chronic diseases such as diabetes, palliative care, and rheumatism is underexplored [45,46]. Additionally, the challenges surrounding the long-term sustainability of telehealth, particularly related to technological infrastructure, must be addressed. Fewer [23,36,52,53] studies have examined telehealth’s cost savings with this population. These studies highlighted telehealth’s efficiency in terms of costs, time, and travel miles savings, as well as satisfaction and acceptability by veterans. Despite the potential benefits of telehealth, they did not mention whether telehealth usage led to an increase in the number of healthcare consultations or improved the overall quality of life. Furthermore, some studies [80,81] examined telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic when there were transportation staff shortages in other populations and telehealth was found to be successful. However, there is relatively no research that has examined the shortage of transportation employees and telehealth use by rural veterans during the pandemic. Future studies could investigate transportation staff shortages during COVID-19 to ascertain whether telehealth improved veterans’ overall quality of life when transportation access was limited. Lastly, post-COVID-19, the VA has expanded telehealth to enhance access to specialty care for veterans in rural areas, with programs like Telesleep [37]. Nevertheless, there are no studies that have investigated the long-term impacts of telehealth after the pandemic, including the utilization rates and how it affects overall healthcare outcomes for veterans. Further studies are needed to understand the long-term impacts of telehealth’s overall outcomes for rural veterans after the pandemic.

This study had some limitations. Firstly, the inclusion of studies from 2017 to 2023 may have affected the inclusion of other relevant articles written before and after this period. Also, the algorithm, search history, and the time or duration used in searching for articles in the various databases is likely to generate different results and hence could limit the number of relevant papers included in this study. Additionally, this study focused on veterans residing in rural areas in the United States; therefore, studies that focused on non-veterans, urban, and rural areas outside the United States were excluded. Moreover, the three databases were selected because they were recognized for their quality and contain comprehensive and relevant articles on this topic; however, this study’s findings may not be generalized as the researchers believe other databases could have relevant articles on this topic. Future studies should consider more than three databases and veterans in the entire United States to provide concrete findings and generalizable results.

6. Conclusions

This study identified the potential benefits of using telehealth to address or manage the medical conditions of veterans residing in rural United States. This suggests that telehealth should be integrated extensively into everyday clinical practice, especially in rural and underserved areas where veterans face significant barriers to accessing healthcare due to distance, mobility issues, and limited provider availability. Also, COVID-19 projected the efficiency and increased utilization of telehealth when some restrictions were imposed to contain the spread of the virus [82,83,84].

In addition, this study revealed some challenges, such as the lack of clinic space, unreliable internet for telemedicine visits, broadband infrastructure, access to devices, and staffing issues as major barriers to the successful implementation or use of telehealth in rural areas. Also, this review mapped some gaps in the literature. Firstly, the limited literature that has examined telehealth’s impact on other aspects of diversity like race, gender, and disability warrants further investigations. Secondly, the small number of cost savings studies call for further examination using different transportation options like Uber, taxis, public transportation, and rides from friends and families. A future qualitative study should explore patients’ acceptance, satisfaction, and quality of care by comparing telemedicine with face-to-face visits to address those disparities in the literature. Furthermore, future research should explore the feasibility of telehealth for other medical conditions, such as rheumatism, cancer, HIV, and diabetes, in rural veterans since this is underexplored post-COVID-19. Lastly, further studies on mental health must use a blended approach to explore diverse veteran populations, including women and veterans residing in rural and underserved regions.

The authors have suggested ways that telehealth could be improved to meet the health needs of veterans in underserved areas. Firstly, integrating and distributing cost-effective devices like smartphones could expand telehealth services in specialized care areas. Policies must be implemented to enhance internet connectivity in rural areas by ensuring reliable and high-speed internet access for telehealth services. This could include public–private partnerships to extend broadband infrastructure to underserved regions. Thirdly, mandated regular training sessions for healthcare providers on telehealth technologies, especially for those serving older veterans with less familiarity with digital tools, could also help bridge the accessibility gap. Lastly, the VA has a travel reimbursement policy that covers veterans’ travel miles. However, introducing extra incentives for veterans to opt for telehealth visits, such as reduced copayments or faster access to care compared to in-person visits, could benefit veterans patronizing telehealth in underserved regions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/soc14120264/s1, Table S1. Reference [85] is cited in the supplementary materials.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| SLR | Systematic Literature Review |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis |

| VA | The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs |

| TH | Telehealth |

| TM | Telemedicine |

| SPIDER | Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type |

| CVT | Clinical video telehealth |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| CBOCs | Community-Based Outpatient Clinics |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| CPP | Community Provider Partnership |

| HT | Home telehealth |

| VHA | Veterans Health Administration |

| VVC | Veterans Video Connect |

References

- Lustig, T.A.; Board on Health & Institute of Medicine. The Role of Telehealth in an Evolving Health Care Environment: Workshop Summary; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Volume 20, pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- VA Rural Telehealth, Office of Rural Health Information Sheet, (12 April 2024). Available online: https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/docs/ORH_Rural-Telehealth-InfoSheet_2020_FINAL_508.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Walker, D.L.; Nouri, M.S.; Plouffe, R.A.; Liu, J.J.W.; Le, T.; Forchuk, C.A.; Gargala, D.; St Cyr, K.; Nazarov, A.; Richardson, J.D. Telehealth experiences in Canadian veterans: Associations, strengths, and barriers to care during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Mil Health 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manyati, T.K.; Mutsau, M. Exploring the effectiveness of telehealth interventions for diagnosis, contact tracing and care of coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) patients in sub-Saharan Africa: A rapid review. Health Technol. 2021, 11, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryden, E.M.; Kennedy, M.A.; Conti, J.; Boudreau, J.H.; Anwar, C.P.; Nearing, K.; Pimentel, C.B.; Hung, W.W.; Moo, L.R. Perceived benefits of geriatric specialty telemedicine among rural patients and caregivers. Health Serv. Res. 2023, 58, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brotman, J.J.; Kotloff, R.M. Providing Outpatient Telehealth Services in the United States: Before and During Coronavirus Disease 2019. Chest 2021, 159, 1548–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobe, E.A.; Lewinski, A.A.; Jeffreys, A.S.; Smith, V.A.; Coffman, C.J.; Danus, S.M.; Sidoli, E.; Greck, B.D.; Horne, L.; Saxon, D.R.; et al. Implementation of an Intensive Telehealth Intervention for Rural Patients with Clinic-Refractory Diabetes. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 3080–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chumbler, N.R.; Neugaard, B.; Kobb, R.; Ryan, P.; Qin, H.; Joo, Y. Evaluation of a care coordination/home-telehealth program for veterans with diabetes: Health services utilization and health-related quality of life. Eval. Health Prof. 2005, 28, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, S.; Amit, S.; Kafy, A.A. Gender disparity in telehealth usage in Bangladesh during COVID-19. SSM-Ment. Health 2022, 2, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, W.; Pullyblank, K.; Scribani, M.; Krupa, N.; Fink, A.; Kern, M. Determinants of telehealth technologies in a rural population. Telemed. E-Health 2023, 29, 1530–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumbler, N.R.; Chen, M.; Harrison, A.; Surbhi, S. Racial and Socioeconomic Characteristics Associated with the use of Telehealth Services Among Adults With Ambulatory Sensitive Conditions. Health Serv. Res. Manag. Epidemiol. 2023, 10, 23333928231154334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, K.L.; Singh, S.; Seaton, C.L.; Burton, L.; Li, E.; Jones, C.; Davis, J.C.; Hasan, K.; Kern, B.; Janke, R. Telehealth use for enhancing the health of rural older adults: A systematic mixed studies review. Gerontologist 2022, 62, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, J.E.; McCool, R.R.; Davies, V.A. Telemedicine: An Analysis of Cost and Time Savings. Telemed. J. E-Health 2016, 22, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glynn, L.H.; Chen, J.A.; Dawson, T.C.; Gelman, H.; Zeliadt, S.B. Bringing chronic-pain care to rural veterans: A telehealth pilot program description. Psychol. Serv. 2021, 18, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butzner, M.; Cuffee, Y. Telehealth interventions and outcomes across rural communities in the United States: Narrative review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e29575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangachari, P.; Mushiana, S.S.; Herbert, K. A narrative review of factors historically influencing telehealth use across six medical specialties in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Amo, I.F.; Erkoyuncu, J.A.; Roy, R.; Palmarini, R.; Onoufriou, D. A systematic review of augmented reality content-related techniques for knowledge transfer in maintenance applications. Comput. Ind. 2018, 103, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengist, W.; Soromessa, T.; Legese, G. Ecosystem services research in mountainous regions: A systematic literature review on current knowledge and research gaps. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 702, 134581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparyan, A.Y.; Yessirkepov, M.; Voronov, A.A.; Trukhachev, V.I.; Kostyukova, E.I.; Gerasimov, A.N.; Kitas, G.D. Specialist Bibliographic Databases. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 660–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palozzi, G.; Schettini, I.; Chirico, A. Enhancing the Sustainable Goal of Access to Healthcare: Findings from a Literature Review on Telemedicine Employment in Rural Areas. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, C.S.; Bouffard, S.; Dougherty, M.; Parro, J.S. Telemedicine Use in Rural Native American Communities in the Era of the ACA: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Med. Syst. 2016, 40, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, S.C.; Day, G.; Keller, M.; Touchett, H.; Amspoker, A.B.; Martin, L.; Lindsay, J.A. Personalized implementation of video telehealth for rural veterans (PIVOT-R). Mhealth 2021, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, S.G.; Coan, L.M.; Porter, A.K. Meeting the needs of rural veterans through rapid implementation of pharmacist-provided telehealth management of diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2023, 63, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haverhals, L.M.; Manheim, C.E.; Katz, M.; Levy, C.R. Caring for Homebound Veterans during COVID-19 in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Foster Home Program. Geriatrics 2022, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimentel, C.B.; Dryden, E.M.; Nearing, K.A.; Kernan, L.M.; Kennedy, M.A.; Hung, W.W.; Riley, J.; Moo, L.R. The role of Department of Veterans Affairs community-based outpatient clinics in enhancing rural access to geriatrics telemedicine specialty care. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 72, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lum, H.D.; Nearing, K.; Pimentel, C.B.; Levy, C.R.; Hung, W.W. Anywhere to Anywhere: Use of Telehealth to Increase Health Care Access for Older, Rural Veterans. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2020, 30, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecker, A.H.; Amspoker, A.B.; Hogan, J.B.; Lindsay, J.A. The Impact of Co-occurring Anxiety and Alcohol Use Disorders on Video Telehealth Utilization Among Rural Veterans. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2021, 6, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreck, E.; Nehrig, N.; Schneider, J.A.; Palfrey, A.; Buckley, J.; Jordan, B.; Ashkenazi, S.; Wash, L.; Baer, A.L.; Chen, C.K. Barriers and facilitators to implementing a U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Telemental Health (TMH) program for rural veterans. J. Rural Ment. Health 2020, 44, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, T.L.; Amspoker, A.B.; Wassef, M.; Hogan, J.B.; Helm, A.; Jackson, C.; Jacobs, A.; Shammet, R.; Speicher, S.; Lindsay, J.A.; et al. Increasing access to care for trauma-exposed rural veterans: A mixed methods outcome evaluation of a web-based skills training program with telehealth delivered coaching. J. Rural Health 2022, 38, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Amspoker, A.B.; Fletcher, T.L.; Jackson, C.; Jacobs, A.; Hogan, J.; Shammet, R.; Speicher, S.; Lindsay, J.A.; Cloitre, M. A Resource Building Virtual Care Programme: Improving symptoms and social functioning among female and male rural veterans. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021, 12, 1860357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Homer, M.; Rossi, M.I. Use of Clinical Video Telehealth as a Tool for Optimizing Medications for Rural Older Veterans with Dementia. Geriatrics 2018, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, J.S.; Buckner, J. Reaching Out to Rural Caregivers and Veterans with Dementia Utilizing Clinical Video-Telehealth. Geriatrics 2018, 3, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, C.E.; Spooner, H.; Lee, J.B.; Sonke, J.; Myers, K.; Snow, E. Telehealth-based creative arts therapy: Transforming mental health and rehabilitation care for rural. Arts Psychother. 2018, 57, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.B.; Erbes, C.; Grubbs, K.; Fortney, J. Social Support Moderates the Association Between Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Treatment Duration and Treatment Outcomes in Telemedicine-Based Treatment Among Rural Veterans. J. Trauma Stress 2020, 33, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicosia, F.M.; Kaul, B.; Totten, A.M.; Silvestrini, M.C.; Williams, K.; Whooley, M.A.; Sarmiento, K.F. Leveraging Telehealth to improve access to care: A qualitative evaluation of Veterans’ experience with the VA TeleSleep program. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, Z.; Hotchkiss, J.; Atwood, C.; Smith, C.; Totten, A.; Boudreau, E.; Folmer, R.; Chilakamarri, P.; Whooley, M.; Sarmiento, K. Travel Burden as a Measure of Healthcare Access and the Impact of Telehealth within the Veterans Health Administration. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2023, 38, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkora, J.K.; Ortiz DeBoque, L.; Folmer, R.L.; Totten, A.M.; Williams, K.; Whooley, M.A.; Boudreau, E.; Atwood, C.W.; Zeidler, M.; Rezayat, T.; et al. Sustainment of the TeleSleep program for rural veterans. Front. Health Serv. 2023, 3, 1214071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, B.J.; Vaughan-Sarrazin, M. Home Telehealth and Caregiving Appraisal in Chronic Illness. Telemed. J. E-Health 2017, 23, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestrini, M.; Indresano, J.; Zeliadt, S.B.; Chen, J.A. “There’s a huge benefit just to know that someone cares”: A qualitative examination of rural veterans’ experiences with TelePain. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVeigh, C.; Reid, J.; Carvalho, P. Healthcare professionals’ views of palliative care for American war veterans with non-malignant respiratory disease living in a rural area: A qualitative study. BMC Palliat. Care 2019, 18, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, L.D.; Banks, R.E.; Stryczek, K.C.; Crnich, C.J.; Ide, E.M.; Wilson, B.M.; Viau, R.A.; Ball, S.L.; Jump, R.L.P. A pilot study using telehealth to implement antimicrobial stewardship at two rural Veterans Affairs medical centers. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2018, 39, 1163–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.L.; Steffen, M.J.; McCoy, K.D.; Cannon; Seaman, A.T.; Anderson, Z.; Patel, S.; Green, J.; Wardyn, S.; Solimeo, S.L. Delivering fracture prevention services to rural US veterans through telemedicine: A process evaluation. Arch. Osteoporos. 2021, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, C.; Erickson, K.; Litke, J. Innovative models for providing clinical pharmacy services to remote locations using clinical video telehealth. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2017, 74, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litke, J.; Spoutz, L.; Ahlstrom, D.; Perdew, C.; Llamas, W.; Erickson, K. Impact of the clinical pharmacy specialist in telehealth primary care. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2018, 75, 982–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.Y.; El-Kouri, N.T.; Elliot, D.; Shields, J.; Caram, M.E.V.; Frankel, T.L.; Ramnath, N.; Passero, V.A. Telehealth for Cancer Care in Veterans: Opportunities and Challenges Revealed by COVID. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, 1, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, C.; Fernández-Ávila, D.G.; Plazzotta, F.; Soriano, E.R. Telehealth and Telemedicine in Latin American Rheumatology, a New Era After COVID-19. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2023, 29, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, P.; Echt, K.V.; Markland, A.D.; Zubkoff, L. Impacts of COVID-19 on Health and Healthcare for Rural Veterans in Home-Based Primary Care. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2023, 43, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujral, K.; Van Campen, J.; Jacobs, J.; Kimerling, R.; Blonigen, D.; Zulman, D.M. Mental Health Service Use, Suicide Behavior, and Emergency Department Visits Among Rural US Veterans Who Received Video-Enabled Tablets During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e226250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale-Gallardo, J.; Kreider, C.M.; Castañeda, G.; LeBeau, K.; Varma, D.S.; Knecht, C.; Cowper Ripley, D.; Jia, H. Meeting the Needs of Rural Veterans: A Qualitative Evaluation of Whole Health Coaches’ Expanded Services and Support during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.M.; Jacobs, J.; Yefimova, M.; Greene, L.; Heyworth, L.; Zulman, D.M. Virtual care expansion in the Veterans Health Administration during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical services and patient characteristics associated with utilization. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2021, 28, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBeau, K.; Varma, D.S.; Kreider, C.M.; Castañeda, G.; Knecht, C.; Cowper Ripley, D.; Jia, H.; Hale-Gallardo, J. Whole Health coaching to rural Veterans through telehealth: Advantages, gaps, and opportunities. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1057586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Pujara, S.; Sutton, S.; Rhee, M. Telemedicine in the Management of Type 1 Diabetes. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2018, 15, E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihrig, C. Travel Cost Savings and Practicality for Low-Vision Telerehabilitation. Telemed. J. E-Health 2019, 25, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakkalanka, J.P.; Lund, B.C.; Ward, M.M.; Arndt, S.; Field, R.W.; Charlton, M.E.; Carnahan, R.M. Telehealth Utilization Is Associated with Lower Risk of Discontinuation of Buprenorphine: A Retrospective Cohort Study of US Veterans. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 37, 1610–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheinfil, A.Z.; Day, G.; Walder, A.; Hogan, J.; Giordano, T.P.; Lindsay, J.; Ecker, A. Rural Veterans with HIV and Alcohol Use Disorder receive less video telehealth than urban Veterans. J. Rural Health 2023, 40, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nearing, K.A.; Lum, H.D.; Dang, S.; Powers, B.; McLaren, J.; Gately, M.; Hung, W.; Moo, L. National Geriatric Network Rapidly Addresses Trainee Telehealth Needs in Response to COVID-19. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1907–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittari, G.; Savva, D.; Tomassoni, D.; Tayebati, S.K.; Amenta, F. Telemedicine in the COVID-19 Era: A Narrative Review Based on Current Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, A.; Scott, J.Y.; Chow, A.W.; Jiang, H.; Dismuke-Greer, C.E.; Gujral, K.; Yoon, J. Rural and urban differences in the implementation of Virtual Integrated Patient-Aligned Care Teams. J. Rural Health 2023, 39, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, U.; Malik, P.; DeMasi, M.; Lunagariya, A.; Jani, V. Multidisciplinary Approach and Outcomes of Tele-neurology: A Review. Cereus 2019, 11, e4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, S.; Gupta, A.; Shah, I.; Mitri, J. Medicare telehealth Pre and Post-COVID-19. Telehealth Med. Today 2021, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, L.B.; Yoo, C.; Chu, K.; O’Shea, A.; Jackson, N.; Heyworth, L.; Der-Martirosian, C. Rates of Primary Care and Integrated Mental Health Telemedicine Visits Between Rural and Urban Veterans Affairs Beneficiaries Before and After the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e231864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borders, T.F. Article of the Year, Telehealth Services, and More in the Summer 2019 Issue of The Journal of Rural Health. J. Rural Health 2019, 35, 285–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanaboni, P.; Wootton, R. Adoption of routine telemedicine in norwegian hospitals: Progress over 5 years. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safdari, R.; Ahmadi, M.; Bahaadinbeigy, K.; Farzi, J.; Noori, T.; Mehraeen, E. Identifying and validating requirements of telemental health services for iranian veterans. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 1216–1221. [Google Scholar]

- Lum, J.; Sadej, I.; Pizer, S.D.; Yee, C. Telehealth access and substitution in the VHA. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2024, 39, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenzie, E.S.; Patzel, M.; Nelson, E.J.; Lovejoy, T.I.; Ono, S.S.; Davis, M.M. Long drives and red tape: Mapping rural veteran access to primary care using causal-loop diagramming. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattson, J.; Quayson, B. Impacts of Transit on Health in Rural and Small Urban Areas; North Dakota State University, Upper Great Plains Transportation Institute: Fargo, North Dakota, 2023; Volume 23, pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wierwille, J.; Pukay-Martin, N.D.; Chard, K.M.; Klump, M.C. Effectiveness of PTSD telehealth treatment in a VA clinical sample. Psychol. Serv. 2016, 13, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfan, S.; Alamoodi, A.H.; Zaidan, B.B.; Al-Zobbi, M.; Hamid, R.A.; Alwan, J.K.; Ahmaro, I.Y.Y.; Khalid, E.T.; Jumaah, F.M.; Albahri, O.S.; et al. Telehealth utilization during the Covid-19 pandemic: A Systematic Review. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 138, 104878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlander, E.; Barboza, K.C.; Jensen, A.; Skursky, N.; Bennett, K.; Sherman, S.; Schwartz, M. Veterans’ Preferences for Remote Management of Chronic Conditions. Telemed. J. E-Health 2018, 24, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.E.; Mars, M. Telehealth in the developing world: Current status and future prospects. Smart Homecare Technol. TeleHealth 2015, 3, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintzle, S.; Rivas, W.A.; Castro, C.A. Satisfaction of the use of telehealth and access to care for veterans during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemed. J. E-Health 2022, 28, 706–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsen, C.; Dilip, D.; Carter-Harris, L.; O’Brien, M.; Whitlock, C.W.; de Leon-Sanchez, S.; Ostroff, J.S. Rapid Scaling Up of Telehealth Treatment for Tobacco-Dependent Cancer Patients During the COVID-19 Outbreak in New York City. Telemed. J. E-Health 2021, 27, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, C.M.; Campen, J.V.; Hu, J.; Slightam, C.; Heyworth, L.; Zulman, D.M. Crossing the digital divide: A veteran affairs program to distribute video-enabled devices to patients in a supportive housing program. JAMIA Open 2022, 5, ooac027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.; Blonigen, D.M.; Kimerling, R.; Slightam, C.; Gregory, A.J.P.; Gurmessa, T.; Zulman, D.M. Increasing Mental Health Care Access, Continuity, and Efficiency for Veterans Through Telehealth With Video Tablets. Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, H.; Thorpe, A.; Stevens, V.; Butler, J.; Drews, F.A.; Burpo, N.; Fagerlin, A. Telehealth Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Veterans and Nonveterans: Web-Based Survey Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e42217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordasco, K.M.; Yuan, A.H.; Rollman, J.E.; Moreau, J.L.; Edwards, L.K.; Gable, A.R.; Hsiao, J.J.; Ganz, D.A.; Vashi, A.A.M.; Mehta, P.A.M.; et al. Veterans’ Use of Telehealth for Veterans Health Administration Community Care Urgent Care During the Early COVID-19 Pandemic. Med. Care 2022, 60, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajarawala, S.N.; Pelkowski, J.N. Telehealth Benefits and Barriers. J. Nurse Pract. 2021, 17, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. Telemedicine for healthcare: Capabilities, features, barriers, and applications. Sens. Int. 2021, 2, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rine, S.; Lara, S.T.; Bikomeye, J.C.; Beltrán-Ponce, S.; Kibudde, S.; Niyonzima, N.; Lawal, O.O.; Mulamira, P.; Beyer, K.M.M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care including innovations implemented in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. J. Glob. Health 2023, 13, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluyede, L.; Cochran, A.L.; Wolfe, M.; Prunkl, L.; McDonald, N. Addressing transportation barriers to health care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives of care coordinators. Transp. Res. Part A 2022, 159, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battineni, G.; Nittari, G.; Sirignano, A.; Amenta, F. Are telemedicine systems effective healthcare solutions during the COVID-19 pandemic? J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2021, 16, 305–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battineni, G.; Pallotta, G.; Nittari, G.; Amenta, F. Telemedicine framework to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2021, 16, 300–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veterans, A. How Is the VA System Doing with Access Nationally? 2021. Available online: https://www.accesstocare.va.gov/Healthcare/Overall (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).