Abstract

This study explores the Potaxie, Fifes, and Tilinx subcultures on TikTok, examining their origins, characteristics, and cultural significance. Originating from a viral video in 2020, the Potaxie subculture emerged within the Spanish-speaking LGBTQ+ community and evolved to symbolise inclusivity and gender equality. Potaxies use vibrant aesthetics influenced by Japanese and Korean pop culture to express their identities and resistance. In contrast, Fifes, associated with cisgender heterosexual men, embody traditional patriarchal values, often sexist and homophobic, creating a narrative of resistance between the groups. The Tilinx, symbolic descendants of the Potaxies, are inspired by ballroom culture and drag houses, with “Potaxie mothers” continuing the fight for inclusion and diversity. Using a mixed-methods approach, including quantitative analysis through the TikTok API and qualitative content analysis via MAXQDA and Python, this study provides a comprehensive understanding of the subculture that accumulates over 2.3 billion interactions. The findings highlight how TikTok serves as a platform for identity construction, cultural resistance, and the redefinition of social norms. Additionally, the study examines how digital platforms mediate intersectional experiences, favouring certain types of content through algorithms, and how participants navigate these opportunities and constraints to express their intersecting identities. The implications for communication strategies, youth policies, educational plans, and research on the commercialization of these subcultures are profound, offering insights into the transformative potential of social media in shaping contemporary cultural and social narratives.

1. Introduction

The digital era has radically transformed the landscape of cultural expression and community formation. Platforms such as TikTok have played a crucial role in these changes, emerging as dominant spaces where various subcultures thrive and interact. Among these subcultures, the Potaxies, Fifes, and Tilinx offer a fascinating study of digital identity, resistance, and community dynamics.

The term “Potaxie” gained popularity from a viral TikTok video in 2020, where Cristina González, a Puerto Rican woman, humorously referred to avocados as “potaxio”. This term was quickly adopted by the LGBTQ+ community in Spain, Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, and beyond, evolving into “Potaxie” to incorporate an inclusive suffix in Spanish.

The Potaxie subculture is defined by its vibrant and visually dynamic aesthetics, which draw heavily from the pop cultures of Japan and Korea. It also demonstrates a strong commitment to advancing gender equality and advocating for LGBTQ+ rights. This subculture serves as a creative and inclusive space where its members embrace diverse expressions of identity, reflecting a progressive stance on social issues [1]. The fusion of these aesthetic and political elements makes Potaxies a unique digital community that challenges conventional norms and fosters inclusivity.

The rise in the Potaxie subculture mirrors the emergence of other notable subcultures that have found their place and flourished through social media. For example, the Gothic subculture, which began in the late 1970s and 80s, experienced a resurgence and new interpretations on platforms like MySpace and later Instagram, where aesthetics, music, and fashion could be widely shared. Similarly, the vaporwave movement, which began as an internet meme genre in the early 2010s, used platforms like Tumblr and YouTube to cultivate a global following through its distinctive visuals and retro-futuristic music.

Typically composed of cisgender heterosexual men who play the video game FIFA, Fifes symbolise traditional patriarchal values and are often perceived as sexist, homophobic, and misogynistic. This group is also frequently associated with bullying and cyberbullying behaviours, particularly targeting members of more inclusive and progressive subcultures, such as Potaxies. The dynamics of online harassment often manifest in the form of cyberbullying, where Fifes, adhering to conventional gender roles and values, engage in hostile actions against those who challenge or differ from their worldview [2]. This aligns with broader patterns of digital abuse where toxic masculinity is often expressed through online platforms, fostering environments where marginalised groups become targets of harassment.

This dynamic establishes a narrative of resistance and opposition between the two groups, reflecting broader social tensions and ideological conflicts. Moreover, the Tilinx, regarded as the symbolic “children” of the Potaxies, draw inspiration from ballroom culture and the tradition of drag houses. Their name, derived from an Argentine meme about a boy named Tilín, represents the next generation within the Potaxie subculture, continuing the fight for inclusion and diversity.

The tension between idealised images and reality is prominently displayed through social media influencers [3]. Drawing on Bandura’s [4] social cognitive theory and Festinger’s social comparison theory, which has previously been applied to analyse the relationship between media exposure and body image perception [5], it is plausible to argue that the content shared by influencers significantly shapes their followers’ body image construction [6,7]. The essence of this influence lies in the fact that, within the influencer universe, all content revolves around a central figure, whose physical appearance becomes crucial for community building, according to the concept of media opinion leadership [6].

Additionally, considering the commercial purposes behind some influencer-generated content, concerns about their impact become even more amplified. The commercial appeal of influencers is undeniable: despite a 23% drop in advertising investment in Spain in 2022, influencer marketing saw notable growth [8]. Previous research [9,10,11,12] has shown that exposure to influencer content can negatively affect users’ body satisfaction, but it is also important to recognise the potential positive effects. For example, Durau et al. [13] found that fitness influencer content can effectively promote physical activity among followers. At the same time, Dohnt and Tiggemann [14], and Orth and Robins [15], highlighted that the aim of these profiles is to inspire self-care movements and healthy self-esteem.

To understand contemporary digital subcultures, it is essential to explore their origins and evolution. In the post-World War II context of the 1950s and 1960s, youth subcultures emerged with significant force. Movements such as the beatniks and hippies in the United States, and the mods and rockers in the United Kingdom, represented cultural resistances to established norms while seeking new identities [16]. The beatniks focused on literary self-expression and rejection of materialism, while the hippies advocated for peace, love, and communal living [17,18]. In the UK, mods, known for their stylish clothing and affinity for soul and R&B music, contrasted with the rockers, who adopted a rebellious aesthetic inspired by rock and roll [19,20].

During the 1970s and 1980s, subcultures such as punk and hip-hop emerged as forms of resistance to economic crises and social exclusion. Punk, with its DIY ethos and aggressive style, challenged the status quo through music and fashion [19]. In a different context, but with an equally rebellious spirit, hip-hop emerged in the Bronx as an expressive outlet for African American and Latino youth. This subculture used rap, graffiti, and breakdancing to comment on and resist social and racial injustices [21,22].

The arrival of the internet in the 1990s began to dramatically transform the dynamics of youth subcultures. Access to information and global communities allowed young people to connect and share ideas beyond geographical barriers [23]. This digital connectivity facilitated the formation of transnational identities and communities, expanding the reach and influence of subcultures. Platforms such as discussion forums, and later social media, provided new spaces for self-expression and collective organisation [24]. This reconfiguration of traditional subcultural interaction gave rise to emerging cultural phenomena that continue to evolve in the 21st century. The internet has played a crucial role in amplifying subcultural voices, allowing them to influence broader cultural narratives in unprecedented ways [25].

In the 2000s, the expansion of social media platforms like MySpace, YouTube, and later Facebook facilitated the emergence of new digital subcultures. These platforms enabled the creation and diffusion of user-generated content, allowing the formation of new youth identities. MySpace, for example, became a hub for musical subcultures, while YouTube provided a platform for diverse content creators to build communities around shared interests [24,26]

The 2010s marked a new phase in the evolution of youth subcultures with the emergence of platforms like Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok, and Discord. These platforms not only supported the creation and sharing of content but also fostered the formation of communities around memes, viral videos, and shared aesthetics. Instagram and Snapchat introduced visual storytelling and ephemeral content, which became central to identity performance for younger generations [27]. TikTok’s algorithm-driven content delivery system allowed for rapid viral dissemination, making it fertile ground for new subcultural trends [28]. Discord facilitated community building through topic-specific servers, allowing users to engage in real-time communication [29]. These developments have significantly influenced how youth subcultures form, interact, and evolve in the digital age, highlighting the role of social media in shaping contemporary cultural landscapes.

Today, some digital subcultures, like Potaxies and Tilinx, use digital tools to organise, mobilise, and spread their messages of equality and inclusion. Platforms like TikTok and Discord facilitate these efforts by providing spaces for community building and activism, as seen during significant social movements like #MeToo and Black Lives Matter [30,31]. These digital subcultures, by promoting values of inclusivity and social justice, offer a model for how institutions can address issues of diversity and equity.

In the current context, studying digital subcultures is crucial due to the dominant role social media play in everyday life. These platforms not only facilitate the creation and diffusion of subcultural identities and communities but also act as spaces of cultural resistance and redefinition of social norms. Understanding these dynamics allows us to appreciate the profound impact they have on identity formation, social interaction, and the shaping of contemporary cultural discourses, highlighting the importance of these subcultures in the transformation of digital society.

2. Research Hypotheses

Although grounded theory typically does not rely on predefined hypotheses, we have opted to include them in this study to align with the specific objectives of our research. These hypotheses serve as guiding constructs that allow us to explore the nuanced dynamics of identity formation, cultural resistance, and algorithmic influence within TikTok subcultures. They are not intended to constrain the inductive nature of our qualitative approach but rather to complement it by providing a framework for integrating theoretical insights with empirical observations. This approach reflects a pragmatic adaptation to the interdisciplinary scope of our study, where grounded theory is enriched with elements of deductive inquiry to address the complexity of digital subcultures.

Based on our objectives to investigate the identity formation processes, cultural dynamics, and the role of TikTok’s algorithm in shaping subcultural interactions, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

Emerging subcultures such as Potaxie and Fifes on TikTok exhibit unique identity markers—such as specific aesthetics, language, and behaviours—that reinforce group boundaries, providing insights into new modes of identity formation among youth in digital spaces and highlighting the relevance of social identity theory.

Hypothesis 2.

The visibility and interaction patterns of these subcultures are shaped by TikTok’s algorithm, which selectively promotes content based on engagement metrics—a phenomenon that may also occur on other platforms such as YouTube, Instagram, and Twitch. This selective promotion has the potential to amplify particular values within these subcultures, highlighting the algorithm’s role in shaping the cultural influence and reach of emerging youth communities online. However, our research focuses specifically on TikTok and does not examine algorithmic effects on these other platforms.

Hypothesis 3.

The Potaxie subculture’s focus on inclusivity and self-deprecating humour represents a shift towards anti-normative social values that challenge traditional norms, particularly in Spanish-speaking communities. This shift has implications for social scientists, educators, and policymakers as it reflects new youth priorities and cultural dynamics that influence identity, inclusivity, and social cohesion.

These hypotheses guide the subsequent analysis, allowing us to investigate the nuanced dynamics of identity, resistance, and algorithmic impact within TikTok subcultures.

3. Method

Our study uses a mixed-methods approach to explore the Potaxie, Fifes, and Tilinx subcultures, combining both quantitative and qualitative analyses. For the quantitative data, we utilised the TikTok API to analyse metrics such as views, “likes”, comments, and shares associated with specific hashtags, identifying trends and geographical distribution. To collect data from TikTok, we obtained access to TikTok’s Research API, a resource that provides authorised academic researchers with tools to gather publicly available data. The application process required us to create a TikTok for Developers account with our university-affiliated email and submit a detailed application, which included a comprehensive research proposal outlining the study’s objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes. Additionally, we provided an endorsement letter from our university, along with a signed code of ethics from our institution’s Ethics Committee, ensuring adherence to data privacy and ethical standards. TikTok’s review process typically takes four weeks; in our case, approval was granted without the need for additional information.

We used QGIS to create a map that visualises the impact of these subcultures across different countries.

Qualitative data were gathered through content analysis, examining themes, narratives, and aesthetics in user-generated videos. This helps to understand how these subcultures build and express their identities [32,33]. Our methodology combines quantitative metrics with qualitative insights to capture the dynamics of online communities [34,35]. Grounded theory techniques ensure a comprehensive analysis of the qualitative data [36].

Research Questions:

- What are the central characteristics and values of the Potaxie and Fife subcultures, and how do they use TikTok to build their identities?

- How do these subcultures resist or conform to dominant cultural norms, and what impact do they have on cultural trends and discourses on TikTok?

Since July 2023, we have conducted digital ethnography on social media, observing dynamics, language, and cultural practices within the Potaxie and Fife communities. For video selection, we used the TikTok API to collect a dataset of 165,000 videos tagged with the hashtags #Potaxie, #Fifes, #Tilinx, #Floptropic, and #Puchaina, gathered between July 2023 and July 2024. From this dataset, we performed stratified sampling to select 2506 videos, ensuring equitable representation of each hashtag and various demographic characteristics. Subsequently, 200 videos were chosen for detailed qualitative analysis in MAXQDA. Selection criteria included thematic relevance, content diversity (gender, sexuality, activism, humour, and cultural critique), popularity as measured by the number of views and “likes”, and geographical representation. This approach allowed for a thorough analysis of the narratives, aesthetics, and identity dynamics present in the videos, providing a deep understanding of how these digital subcultures express themselves and evolve on TikTok.

Also using grounded theory [37], we conducted a thematic analysis, aligned with queer [38] and feminist methodologies that prioritise marginalised voices [39]. We conducted informal interviews with Potaxie influencers and users to understand their motivations and experiences.

The dataset analysed in this study focuses on specific hashtags that represent distinct subcultural identities on TikTok. The hashtags selected for analysis—#Potaxie, #Puchaina, #Fife, #potaxies, and #tilinx—were those submitted in our application to TikTok for Research API access, ensuring our data collection adhered to the approved parameters. These hashtags are documented in detail in the dataset file “TikTok Video’s Quantitative Analysis”, with the “code table” on page 1 listing each hashtag and page 2, “Video Metrics”, presenting engagement metrics. This alignment with TikTok’s approval criteria reinforces the study’s commitment to transparency and replicability in social media research. In accordance with our agreement with TikTok, we did not commit to providing an open-access dataset; instead, we ensured full compliance with ethical standards, including data privacy and confidentiality, with all data made available in anonymized form through a secure link.

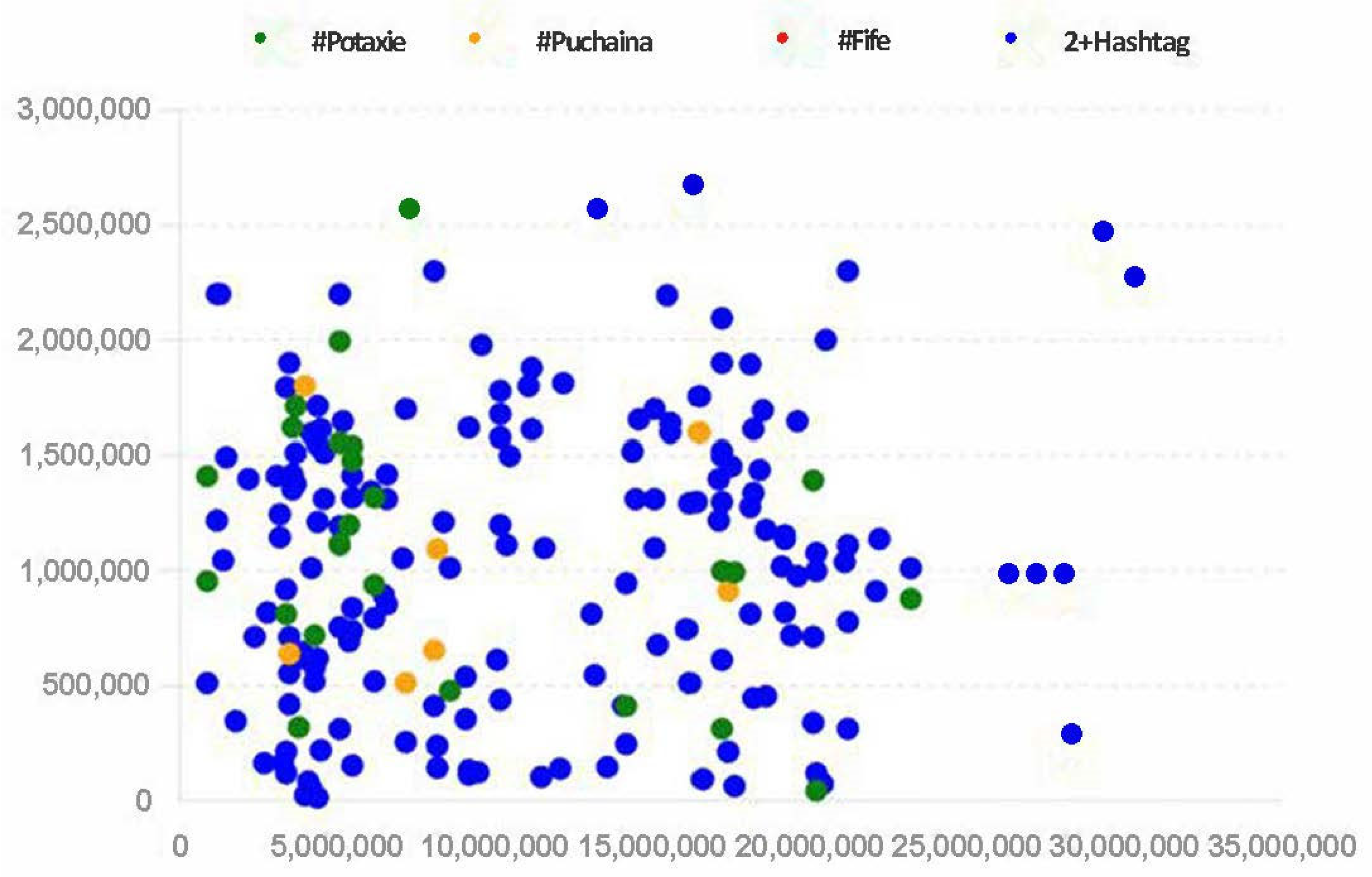

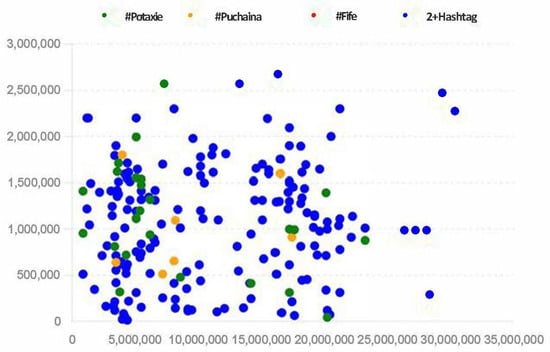

All study data are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26362672. After obtaining TikTok’s approval, we used Python PykTok to collect data from videos with the hashtags #Potaxie, #Fifes, #Tilinx, #Floptropic, and #Puchaina, resulting in 165,000 videos analysed between July 2023 and July 2024. The scatterplot shows the relationship between “likes” and views for the hashtags #potaxies, #fifes, and #puchaina.

4. Results

All study data, including code tables, videos, metrics, and analyses, are available at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26362672. This repository enhances transparency and facilitates further research on the Potaxie subculture. After receiving TikTok’s approval, we used the Python PykTok module to collect data from videos tagged with #Potaxie, #Fifes, #Tilinx, #Floptropic, and #Puchaina, resulting in a dataset of 165,000 videos analysed between July 2023 and July 2024. This data collection process adhered strictly to the methodological framework outlined in the study, with each data point—such as engagement metrics and thematic categorizations—directly stemming from the structured approach and tools employed (e.g., Python PykTok for data extraction and MAXQDA for thematic analysis).

From this comprehensive dataset, 200 videos were selected from a focused sample of 2506 for detailed quantitative analysis, examining metrics such as views, comments, “likes” per hashtag, geographic distribution, and language. Videos were classified by theme (e.g., music, dance, storytelling, humour, and advertisements) and represented contributions from 134 unique creators, demonstrating the methodological consistency in categorising and analysing subcultural expressions on TikTok.

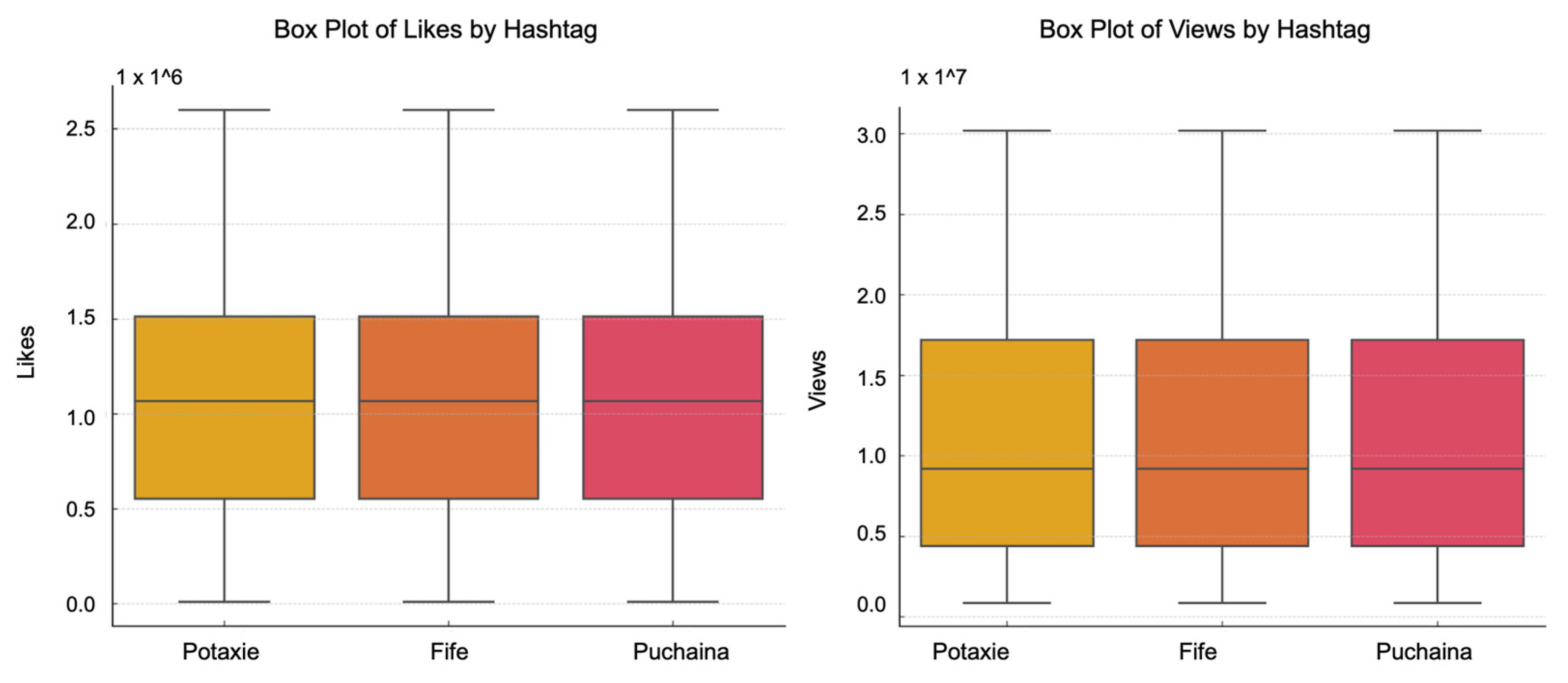

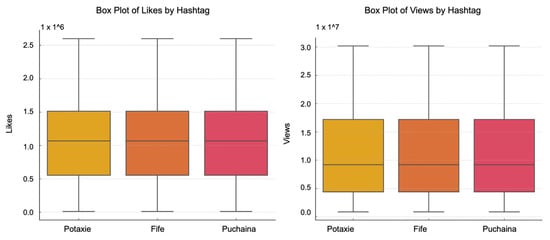

The boxplot (Figure 1) summarises the distribution of “likes” and views of a reference word (hashtag): #Potaxie; #Fife; #Puchaina. Further details are available at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26362693 (p. 1).

Figure 1.

Boxplot of “Likes” vs. views by Hashtag.

Additionally, a scatterplot (Figure 2) displays the relationship between “likes” and views for #Potaxie, #Fifes, and #Puchaina, revealing high variability in “likes” for videos with similar view counts. This finding highlights that user engagement is influenced by factors beyond view count alone, such as content quality and interaction style.

Figure 2.

Scatterplot of the distribution and correlation between “Likes” and views by hashtag.

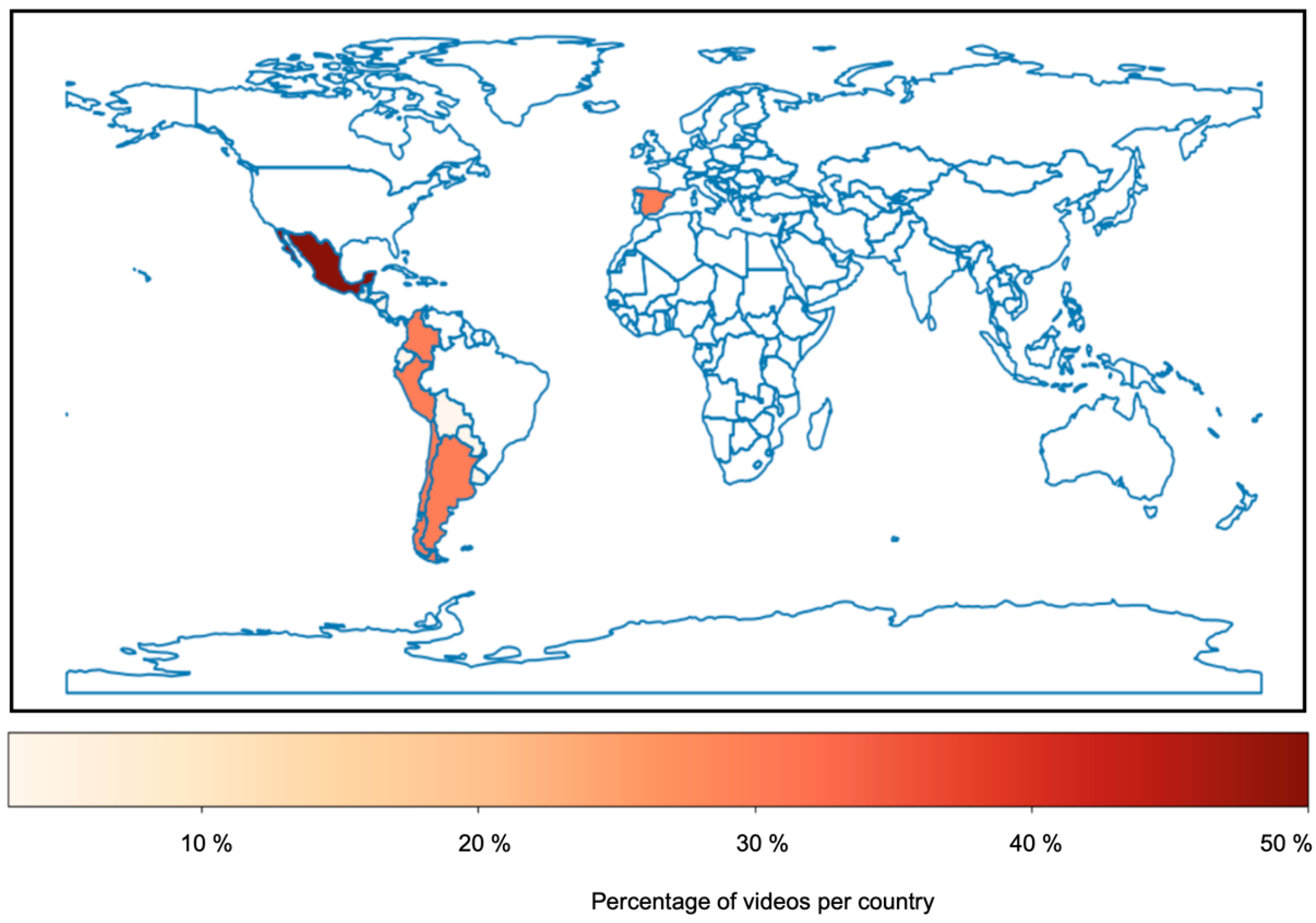

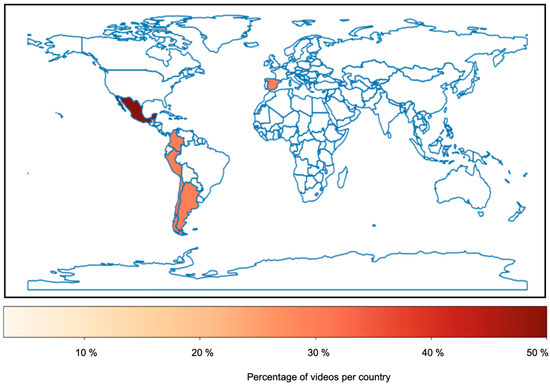

Geographical data (Figure 3) show that video creators using these hashtags predominantly come from Spanish-speaking regions, with Mexico accounting for 45%, Spain 15%, Colombia 12%, Argentina 11%, and Chile 10%, while the United States contributes 5%. The remaining videos are from other Latin American countries. The language analysis revealed that 97.8% of these videos are in Spanish, underscoring the subculture’s strong connection to Spanish-speaking communities. This regional focus supports the concept of ‘glocalization,’ where local cultural expressions adapt to global platforms.

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of videos.

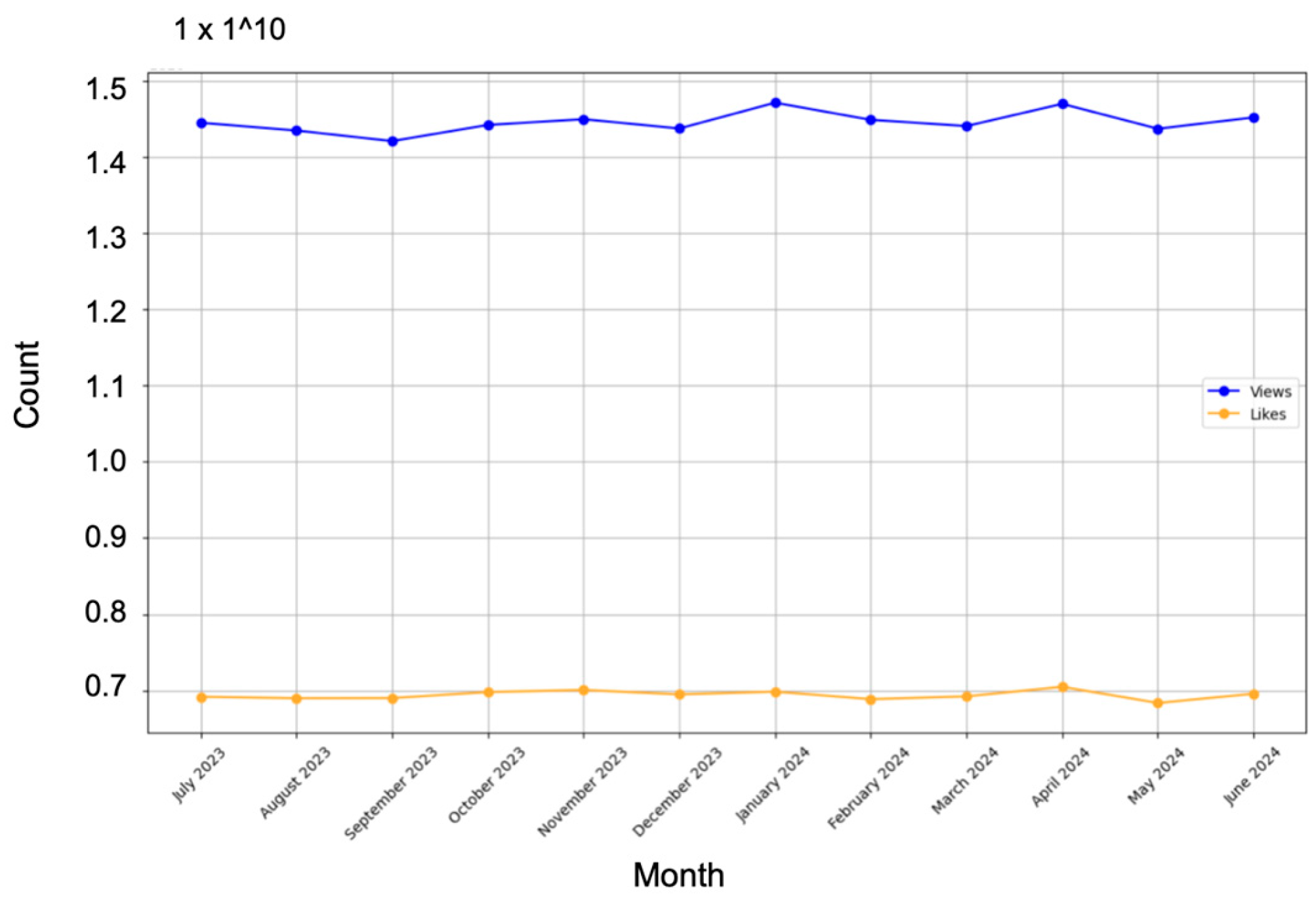

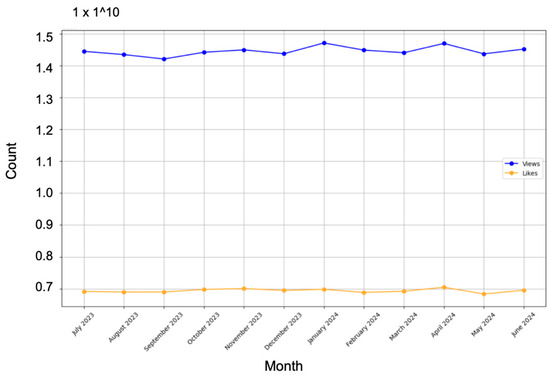

An engagement timeline (Figure 4) illustrates a stable trend in views (around 1.4 billion) and likes (approximately 700 million) from July 2023 to June 2024. This stability suggests that, while Potaxie content consistently attracts a large audience, the “likes” metric reflects variable levels of user interaction, possibly influenced by content style and its resonance with specific audiences.

Figure 4.

Timeline of engagement metrics over time (July 2023–June 2024).

The analysis also reveals a notable trend in collaborative videos across subcultures, where users from different countries engage through shared hashtags, promoting intercultural exchange. The Potaxie community, in particular, uses #fifes as humorous counter-content, which introduces a playful dynamic to subcultural interactions. Brand collaborations are also prominent, emphasising the commercial appeal of these digital subcultures and their impact on consumer behaviour [27].

Our focused analysis of the 200 videos highlights the Potaxie subculture’s prevalence, with an average of 70,000 “likes” per video. This popularity underscores Potaxie’s influence among Spanish-speaking users, indicating a growing subcultural movement. Qualitative analysis complements these quantitative insights by exploring the unique aesthetics, identity construction, and social norms within Potaxie. This transition to qualitative analysis deepens the narrative, showcasing how Potaxie content both aligns with and challenges established societal expectations.

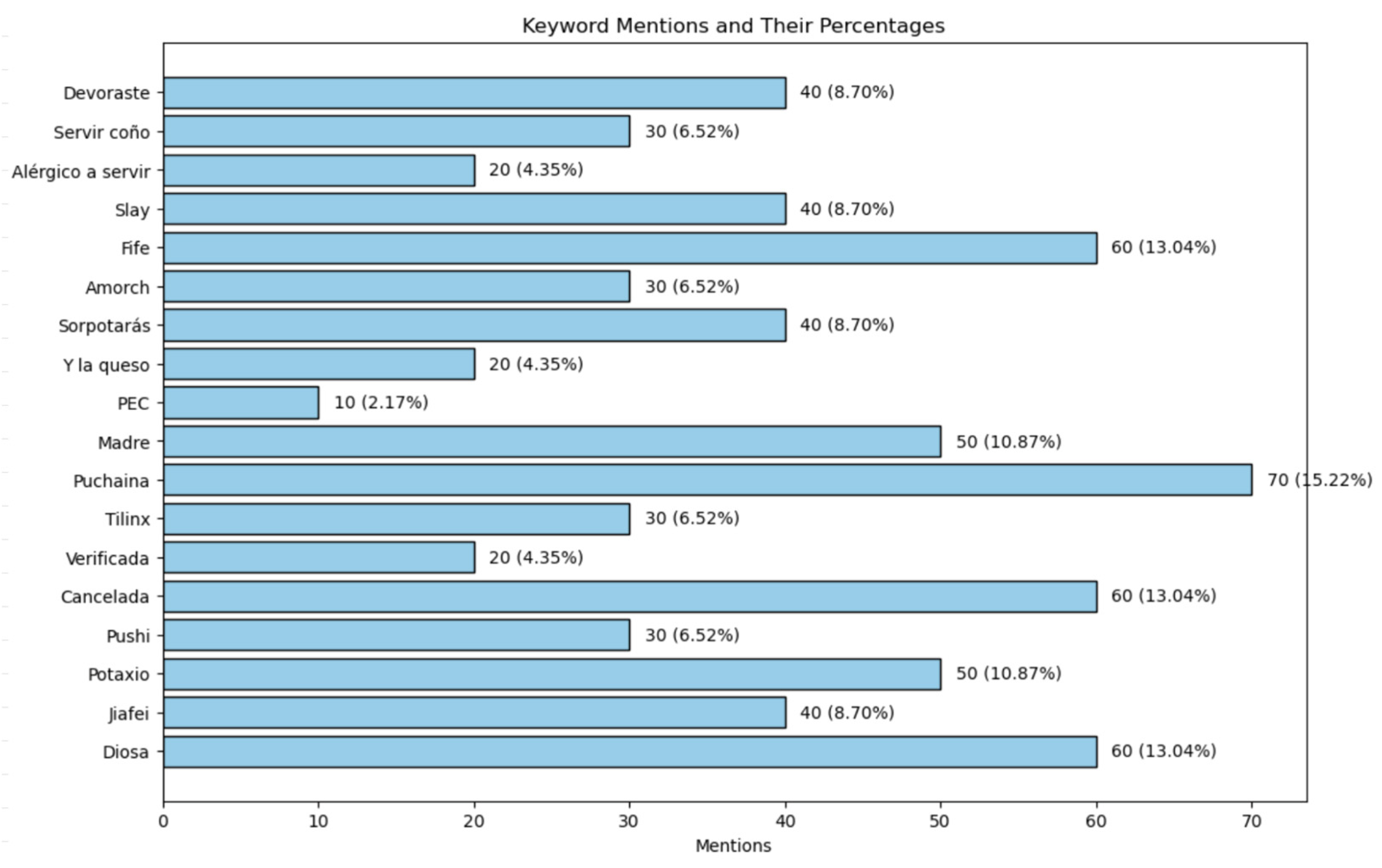

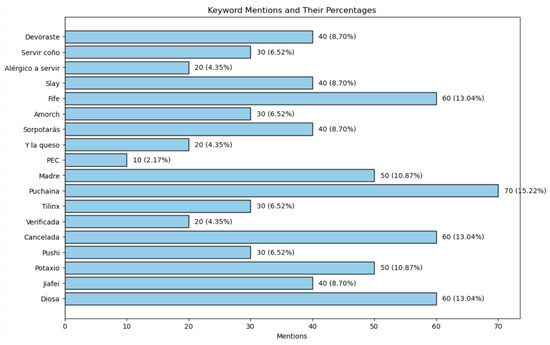

Figure 5 shows the most frequently mentioned keywords, illustrating recurring themes within the Potaxie, Fifes, and Tilinx subcultures. A complete breakdown is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26362693 (accessed on 24 July 2024) (pp. 5–6). All coded data, raw metrics, and Python scripts used in the analysis are accessible at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26362960 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

Figure 5.

Mentions of keywords and their percentages.

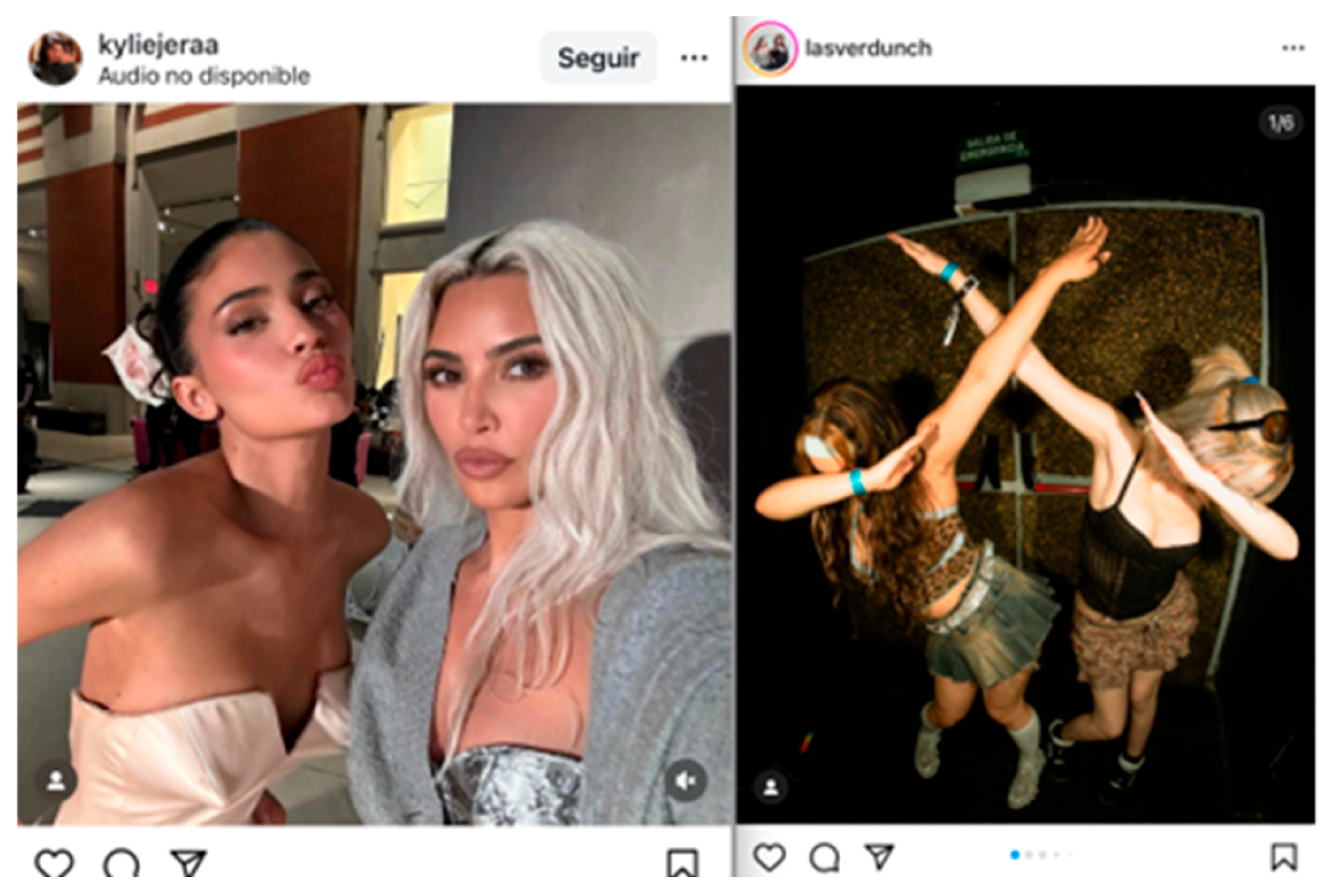

Figure 6 provides examples of Potaxie content, demonstrating how humour, memes, and cultural references help construct a distinctive identity that celebrates imperfection. This approach contrasts with the idealised image culture of platforms like Instagram. Being part of the “Flop Tropika” aesthetic, this self-deprecating humour illustrates the subculture’s commitment to diversity and resistance against unrealistic portrayals.

Figure 6.

Examples of Potaxie subculture content on TikTok.

These subcultures embrace a tropical aesthetic and self-deprecating humour, celebrating imperfection and the “loser” identity. Through memes and digital content, they create a unique identity that rejects the aspirational ideals often associated with Millennials and Generation X, signalling a shift in generational values. Flop Tropika serves as cultural resistance, challenging social norms and promoting inclusivity [27], aligning with the global shift towards authenticity across regions.

This generational divide is further illustrated in Figure 7, which contrasts Millennial and Generation Z content. Millennial posts often feature polished, aspirational content, while Gen Z’s, exemplified by Potaxie, emphasise authenticity, spontaneity, and embracing imperfection as part of digital identity. This shift reflects evolving social media values and user engagement strategies across generations [25].

Figure 7.

Millennial Generation post (left) vs. Gen Z post (right).

Our analysis reveals distinct patterns in content creation, engagement metrics, and cultural expressions within these subcultures, affirming TikTok as a space for identity formation and resistance to social norms. By combining quantitative metrics and qualitative narratives, we gain a holistic understanding of the dynamics shaping these communities. These findings set the stage for a more extensive exploration of broader theoretical and social implications in the following Section 5.

5. Discussion

The data analysis reveals that TikTok serves as a significant medium for identity formation and boundary-setting within digital subcultures, particularly among the Potaxie, Fifes, and Tilinx communities. The Potaxie subculture, characterised by its vibrant aesthetics and inclusive language, resonates strongly with social identity theory, which posits that subcultures provide a space for members to assert identity and establish group boundaries. This is evident in how Potaxies use distinct visual and thematic elements to differentiate themselves from the more conservative Fife subculture, which often embodies resistance to these inclusive values. Quantitative data indicate that videos tagged with #Potaxie and #Tilinx receive significantly higher engagement within Spanish-speaking regions, suggesting a robust local resonance. This trend aligns with the concept of ‘glocalization’ in cultural theory, wherein global platforms like TikTok support local identity expressions that reflect regional values and social norms.

The pronounced antagonism between Potaxie and Fife subcultures also highlights Bourdieu’s theory of cultural capital, as these groups create contrasting identities rooted in shared but opposing values. These dynamic echoes historical subcultural theories, which have long interpreted youth cultures as responses to social or cultural conditions. The Chicago School, for example, viewed subcultures as responses to social disorganisation in marginalised spaces [40,41,42], while the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) interpreted them as symbolic acts of resistance to cultural hegemony [42,43]. The Potaxie and Fife communities reflect this tradition of opposition, mirroring the “urban tribes” described by Maffesoli in the 1990s: groups marked by fluid identities and a collective search for belonging in postmodernity [42,44].

However, while traditional theories provide a strong foundation, our findings suggest the need to expand these frameworks to account for TikTok’s algorithmic influence. As TikTok actively shapes the visibility of content, it also affects the reach and engagement of subcultural identities, reinforcing some voices while limiting others. This algorithm-driven visibility suggests a need for an updated digital subcultural theory that considers how platform dynamics impact identity construction, maintenance, and the distribution of cultural capital within online communities. Thus, while Potaxie, Fife, and Tilinx reflect long-standing patterns of subcultural boundary-setting, the algorithmic forces on TikTok create a distinct environment where digital identities are both constructed and constrained by platform mechanics.

These distinct theories highlight how young people negotiate their identity and place in society, ranging from cultural resistance and adaptation to the creation of new social spaces. These approaches reflect the complexity of urban tribes and youth cultures, which emerge globally and then localise.

5.1. Culture of Resistance and Identity Expression in Digital Subcultures

In the contemporary context, digital subcultures have emerged as crucial forms of cultural resistance and expressions of diverse identities. These subcultures challenge dominant cultural norms and provide platforms for self-expression and the creation of communities based on alternative interests and values. Unlike physical urban tribes, digital subcultures operate globally, connecting young people from different locations who share social and political concerns [45].

Digital subcultures manifest on online platforms such as forums, social networks, and virtual communities, where young people can express their identities and challenge social norms. According to Valderrama and Jimenez [46], technology has facilitated new forms of cultural resistance by providing tools for local communities to reinterpret and adapt technological innovations to their specific contexts. This phenomenon is evident in how digital subcultures use platforms to create and disseminate content that challenges hegemonic narratives. For example, social networks, like TikTok and Twitter, enable young people to question and resist dominant cultural norms through the creation and sharing of content that reflects their unique experiences and perspectives. Castells [47] emphasises that the internet and new information technologies have been crucial in forming resistance movements and creating mutual support networks. However, Wilson [48] points out that these approaches do not always encompass the emerging global and political forms of cultural resistance around social issues such as the environment, globalisation, and gender and racial inequality [49,50,51,52,53].

Identity expression is central to digital subcultures. Communities like the Potaxies exemplify how online spaces allow individuals to explore and assert their identities in an environment that celebrates diversity and creativity. McLaren [54] argues that contemporary youth resistance culture fights against capitalist structures that seek to homogenise identities and suppress diversity. Gitte Stald [55] explores how digital subcultures enable young people to articulate their identities in ways that challenge established social norms. An example is the online LGBTQ+ community, which uses digital platforms to share experiences, organise events, and mobilise political actions, providing a safe space for self-expression and identity affirmation [56,57]. The ability to connect with others who share similar experiences strengthens a sense of belonging and support, which is crucial for maintaining a positive and resilient identity.

Peter McLaren’s theory of cultural resistance holds that youth subcultures emerge as responses to capitalist oppression and exploitation, creating new forms of social and cultural organisation that challenge established norms. Soler-i-Martí and Carles Feixa [58] examines how heterogeneous social movements, with diverse economic, social, and cultural capital, express themselves through different repertoires of protest and opposing discourses, all of which share a marginal position. This framework applies to digital subcultures, where online communities not only resist cultural hegemony but also build new identities and forms of social interaction, often from peripheral positions.

Identity theory suggests that identity construction is a dynamic process that involves constant negotiation between the individual and the social environment. In digital subcultures, this theory highlights how young people use digital technologies to explore and affirm their identities, challenging and redefining cultural norms. Valderrama and Jimenez argue that technological innovations are re-signified by local communities to reflect and support their own values and goals.

The growth of digital subcultures has significant implications for cultural resistance and identity expression. In the first decade of the 2000s, Buckingham [59] observed a shift towards a positive view of technology as liberating for young people, creating a more creative and democratic generation. Prensky [60] highlighted the differences between “digital natives” and “digital immigrants” in terms of learning styles and brain structures. Crovi [61] argued that although young people are considered digitally competent, they often use technology for private purposes rather than for activism. However, García Galera et. al. [62] found that a quarter of young people use social media to participate in solidarity campaigns and social protests, showing a commitment to online civic action. Bennett [63] observed that social media not only drive ideological and educational transformations but also impact DIY cultural practices, offering alternative employment opportunities in economically precarious contexts. As Mina [64] points out, this shift can take communities from publishing memes to generating social movements.

In our study, we observed that online content creation, such as live broadcasts and brand collaborations, is crucial for creators. However, the process of creation and how content is presented are equally important. Critique and advocacy within these spaces reflect the normalisation of discourses that, while becoming mainstream, remain significant.

The identity within the Potaxie universe, for example, is not limited to language or fashion; it seeks to generate a complete culture with its own mythology, social structure, and political organisation. These online communities offer alternative models of organisation that challenge dominant structures and promote diversity and inclusion. Digital natives create identities around digital subcultures that can influence global cultural practices, as ideas and movements within these spaces can spread quickly and gain international support. The “generational consciousness” [65] has driven demand in new markets, where the cultural industry acts as a provider of specific products and experiences for contemporary youth. Hebdige [19] argues that subcultures express this consciousness sharply, existing on cultural margins and being anti-establishment. The cultural industry quickly adapts to these countercultural movements, evidencing the relationship between youth and dominant culture.

Pierre Bourdieu’s extensive theory of cultural capital is key to understanding how individuals accumulate and use capital to gain recognition and power. On social media, cultural capital is manifested through the creation and curation of content that demonstrates cultural and technical competence. Goggin [66] highlights that young people use mobile devices to build and showcase their cultural identity through digital content, gaining followers and increasing their social and cultural capital.

Social networks reconfigure cultural and social capital. Hwang and Kim [67] show that social media use enhances social capital, moderating the relationship between network use and participation in social movements. McEwan and Sobre-Denton [68] introduce the concept of “virtual cosmopolitanism”, describing how computer-mediated communication enables the construction of hybrid cultures and the transmission of cultural and social capital. This is evident in the formation of “third virtual cultures”, where individuals from different backgrounds create digital communities that transcend cultural borders. In online fan communities, for example, content creation related to shared interests contributes to building a cultural identity and recognition within the community. Social networks offer a horizontal civic space that promotes the participation of those often excluded from public engagement [69].

Visibility and recognition on social media are linked to the cultural capital that individuals possess and display. McEwan and Sobre-Denton [68] argue that participation in digital spaces depends on access to technological resources and cultural skills, which can create barriers. However, for those who can participate, social networks offer a platform to amplify their voices and gain recognition.

Goggin’s [66] study shows how young people use mobile technologies to negotiate and redefine their social relationships, acquiring cultural and social capital. Compared to Bourdieu’s theory [70], cultural capital on social networks is dynamic and evolving, continuously adapting and reconfiguring through online interactions. This resonates with Hannerz’s [71] notion of decontextualised cultural capital, where knowledge and skills are adapted and used in multiple cultural contexts.

5.2. Intersectionality and Digital Activism

Intersectionality, a central concept in gender studies and critical race theory, refers to how identity categories (such as gender, ethnicity, social class, and others) intersect to create systems of discrimination or advantage [72]. In the context of digital activism, these intersectional identities find new forms of expression and articulation, leveraging the unique capacities of online platforms to amplify marginalised voices and coordinate collective efforts [73].

Digital subcultures offer spaces where intersectional identities can be expressed and made visible in more dynamic and accessible ways than in traditional media. According to Kaun and Uldam [74], digital activism enables individuals and groups to use digital technologies to challenge hegemonic narratives and create safe spaces for self-expression and mutual support. Platforms such as Twitter and Facebook have been crucial for movements like Black Lives Matter and #MeToo, where experiences of racial and gender discrimination are shared and amplified globally, highlighting the intersections between race and gender in systemic oppression.

Digital activism has been particularly influential in mobilising and organising feminist movements. Clark-Parsons and Lingel [39] analyse how safe online spaces, such as secret Facebook groups, provide supportive environments for women and non-binary people to discuss sensitive topics and coordinate collective actions. Sivitanides and Shah [75] investigated how these spaces not only allow for the visibility of diverse gender identities but also facilitate the real-time organisation of campaigns and protests, taking advantage of the instant mobilisation capabilities offered by digital platforms, as explained by Castillo de Mesa et. al. [73]

Digital activism also plays a crucial role in the visibility and resistance of marginalised ethnic identities. Yang [76] highlights how digital platforms allow Chinese activists to overcome state censorship and organise protest movements. In this context, intersectionality manifests in how ethnic identities intertwine with political and social struggles, using digital activism to challenge official narratives and promote social justice [77].

While digital activism offers new opportunities for organisation and protest, it is also important to recognise the limitations imposed by class inequalities. Sivitanides and Shah note that access to digital technologies and the ability to use them effectively can be significantly influenced by economic factors. People from lower social classes may face barriers to fully participating in digital activism due to a lack of access to suitable devices and reliable internet connections. This highlights the need for intersectional approaches that address these inequalities in order to create more inclusive digital activism.

Intersectional identities are not only expressed but also articulated and empowered within digital subcultures. Marcos Sivitanides and Vivek Shah [75] further discuss how digital infrastructure enables the coordination of movements on an unprecedented scale, which is essential for the success of intersectional campaigns that seek to address multiple forms of oppression simultaneously. Anne Kaun and Julie Uldam [74] argue that digital activism must be understood in its specific context, taking into account the political, economic, and social norms that shape its development. This contextualised approach is crucial to understanding how intersectional identities influence, and are influenced by, the dynamics of digital activism.

5.3. Aesthetics and Commercialisation of Subcultures

Aesthetic is a central element in the construction of subcultural identities. According to Hebdige, subcultures use style as a form of symbolic resistance against dominant culture. This includes choices in clothing, hairstyles, and behaviours that challenge prevailing aesthetic norms [78]. In the digital context, this resistance is translated into the creation of profiles and content that reflect a distinctive aesthetic identity. Platforms such as Instagram and TikTok allow users to express and disseminate their subcultural aesthetics to a global audience, amplifying both their visibility and cohesion.

Social media has transformed how aesthetics are perceived and valued [78,79]. Kaye, Chen and Zeng [28] argue that platforms like TikTok have standardised and vulgarised aesthetic preferences, driven by algorithms that promote popular, yet often superficial, content. This can lead to the homogenisation of subcultural aesthetics, where individual differences are smoothed over in favour of broader, more marketable trends. However, these platforms also offer new avenues for the preservation and dissemination of traditional cultures, providing a space for diverse aesthetic expressions.

The commercialisation of subcultures is not a new phenomenon, but it has taken on new dimensions in the digital age. Adorno and Horkheimer’s [80] concept of the “culture industry” describes how cultural forms are mass-produced and commercialised, losing their authenticity in the process. In the digital context, this is seen in how subcultures are exploited by brands and companies to sell products. Fashion brands, for example, often co-opt subcultural styles to create products that appeal to a broader market.

As we have observed, subcultural aesthetics have found a conducive space on TikTok for their proliferation and visibility, especially among young people. According to Helga Mariel Soto [81], TikTok has propelled the popularity of aesthetics like Dark Academia and Cottagecore, which function as identity brands for centennials and millennials, combining stylistic and clothing elements with specific interests and historical inspirations. Melanie Kennedy [82] highlights that TikTok’s rise during the Coronavirus crisis transformed teenage bedroom culture, turning these private spaces into public stages of visibility and evaluation, celebrating youth culture amid the pandemic. Moreover, the popularity of aesthetics like the e-girl demonstrates how teenage girls dominate the internet today, using the platform to express themselves and showcase their talents. These subcultural developments on TikTok not only reflect current content consumption trends but also underscore the platform’s ability to transform and amplify youth identities in the digital realm [83].

The study by Eggerstedt et al. [84] on facial aesthetics in the age of social media highlights how traditional beauty standards adapt to new digital platforms. Influences from Instagram and other platforms have shaped perceptions of beauty and aesthetics, affecting both consumers and content creators. This reflects a trend towards the commercialisation of aesthetics, where individuals modify their appearance to align with popular aesthetic norms, thereby increasing their visibility and success on commercial platforms. Comparing these ideas with Walter Benjamin’s [85] theory of aesthetics, we find that the technical reproducibility of works of art has led to a democratisation of aesthetics, allowing more people to access and participate in cultural production. However, this same reproducibility can lead to the loss of the “aura” of the artwork, a phenomenon also observed in the commercialisation of digital subcultures. Authenticity and originality can be compromised when subcultural aesthetics are co-opted and mass commercialised.

The commercialisation of subcultures has both positive and negative consequences. On the one hand, it can lead to greater visibility and recognition of these subcultures, providing resources and platforms for cultural expression. On the other hand, it can result in the dilution of the subculture’s original values and meanings, reducing it to a mere commercial product. The co-option of subcultural aesthetics by brands and companies can strip these subcultures of their subversive power, turning them into just another consumer trend.

5.4. Generational Comparison in Social Media Use

Generational differences in the use of social media between Millennials and Generation Z reveal significant changes in identity construction, presentation, and the formation of subcultures. Millennials, born between 1981 and 1996, grew up during a period of digital transition. This generation adopted platforms like Instagram to curate an idealised image of themselves. According to Bourdieu, this curation process relates to the accumulation of cultural capital, where the presentation of an idealised self on visual platforms accumulates social capital in the digital space. Millennials tend to use beauty filters and meticulously planned posts to create a polished and aesthetically appealing digital presence, standing out in a highly visual and competitive environment. This behaviour reflects a desire to excel in a space where appearance is key to social acceptance and success [86].

In contrast, Generation Z, born from 1997 onwards, shows a preference for authenticity and imperfection, using platforms like TikTok to share unfiltered moments that reflect their real lives and genuine identities. Foucault [87] suggests that this preference for authenticity can be interpreted as resistance to the normative pressures of digital self-presentation. Generation Z challenges established norms of beauty, gender [88,89], and normativity [90], redefining what is valued in digital spaces. This approach promotes the deconstruction of traditional hierarchies and norms, fostering inclusivity and diversity [91].

Dominant society and educational institutions often criticise and demonise these subcultures due to a lack of understanding and fear of the changes they represent [92,93]. The hyperconnectivity of young people, facilitated by digital technologies, is viewed with suspicion, despite being a natural adaptation to the digital era [94]. This suspicion arises from concerns about the impact of digital environments on social structures and traditional norms. Potaxies and their symbolic “children”, the Tilinx, with their emphasis on inclusivity and progressive values, are often seen as disruptive forces challenging traditional norms. Their language, as being seen in Figure 5, and in its quasi-dictionary analysis, breaks with traditional language norms. These subcultures advocate for gender equality, LGBTQ+ rights, and social justice, using digital platforms to promote these values. In contrast, the Fifes aim to uphold regressive and conservative values, embodying traditional patriarchal attitudes.

The formative experiences of each generation have also influenced their behaviours on social media. Millennials came of age during a period of economic prosperity, before the Great Recession, which shaped their use of social media as platforms for aspiration and idealised experiences. In contrast, Generation Z grew up during the economic downturn and has witnessed numerous global crises, instilling in them a sense of realism and pragmatism in their social media use. This generation not only adapts to new technologies but also uses them to question and transform existing social structures [95].

Jamie Gutfreund observes that Generation Z values efficiency and personalisation in their interactions with brands, preferring products that offer practical value and help achieve personal goals. This generation is more sceptical of traditional advertising and gravitates towards authentic, unmanipulated content. In contrast, Millennials tend to value experiences and are willing to pay for products that enhance their cultural and social capital on digital platforms [96].

According to Leite et. al. [97], the differences in social media use between generations are significantly shaped by socio-economic backgrounds, which also influence the formation of subcultures. Their research highlights how sociodemographic factors, such as formal education and the amount of time spent online, play a crucial role in shaping online behaviours and the adoption of digital trends. This framework helps explain why the subcultural dynamics between generations like Millennials and Gen Z diverge, as each group’s engagement with online platforms reflects broader socio-economic patterns.

The curation and idealisation characteristics of Millennials have given rise to subcultures that value aesthetics and aspiration. Generation Z, with its focus on authenticity and diversity, has fostered subcultures that celebrate inclusivity and unfiltered individual expression. This generation uses social media to mobilise around social and political causes, promoting inclusive, dialogue-based digital activism while also nurturing different types of personal identities. As noted by Tracy Francis and Fernanda Hoefel [98], “For Gen Zers, the key point is not to define themselves through only one stereotype but rather for individuals to experiment with different ways of being themselves and to shape their individual identities over time. In this respect, you might call them ‘identity nomads’” (p. 4).

These dynamics underscore the tension between the innovative, inclusive ethos of the Potaxies and Tilinx, and the traditionalist, exclusionary stance of the Fifes, reflecting broader social struggles over the acceptance and integration of digital subcultures into mainstream culture [24,99].

5.5. Implications for Understanding New Subcultural Formations in the Digital World

The analysis of generational differences in social media use between Millennials and Generation Z offers valuable insights for youth policies and educational strategies. Understanding how these generations interact with platforms like TikTok is essential for developing effective approaches that meet their specific needs.

Millennials, active on Instagram and TikTok, tend to create posts and tag brands, promoting participatory communication [24,25]. Generation Z responds positively to dynamic and personalised advertisements, highlighting the importance of data analysis for effective communication [100]. Fashion, a significant component of these advertisements, reflects a trend in subcultures. “Aesthetic fashion” includes clothing, accessories, and visual elements, creating a cohesive subcultural identity. Generation Z and Generation X prefer relaxed clothing, emphasising comfort and self-expression, unlike Millennials, who favour more fitted styles [99].

Fashion advertisements are prevalent and reflect self-expression and identity formation in youth subcultures [96]. This underscores the importance of aesthetic presentation and the influence of the market in shaping subcultures, with greater representation on social media [101]. For policymakers, these differences highlight the need to support digital inclusion, media literacy, and youth engagement. TikTok offers opportunities to engage younger generations, collect feedback, and foster civic participation, ensuring equitable access to digital platforms and media literacy programmes.

The use of TikTok for educational purposes among Generation Z suggests that institutions should adopt “edutainment” models to increase engagement and learning outcomes [102]. Integrating digital literacy into curricula can help students critically evaluate information on social media, fostering critical thinking skills [100]. Differences in social media use also have implications for education in identity formation and cultural consumption, with a new preference for authenticity as a form of resistance to the normative pressures of digital self-presentation [87].

It is important to expand the discussion on the limitations of the study, acknowledging that while this analysis provides a deep view of digital subcultures on TikTok, it focuses on public data and may not capture all the internal dynamics of these communities. Additionally, the ever-changing nature of digital platforms implies that findings can quickly become outdated. Future research could explore more deeply how the market influences the creation and evolution of subcultures. Previously, subcultures emerged as movements of resistance against the dominant culture and the market; however, today, the market plays an active role in generating and commercialising subcultures, shaping identities and cultural practices. This paradigm shift raises critical questions about the authenticity, resistance, and commercialisation of youth identities in the contemporary digital environment.

6. Conclusions

This study provides an in-depth understanding of the digital subcultures Potaxie, Fifes, and Tilinx on TikTok, highlighting their cultural and social importance in the digital age. Through a mixed-methods approach, we have explored how these subcultures use digital platforms to construct identities, resist dominant cultural norms, and create inclusive communities.

The Potaxie subculture originates from the LGBTQ+ community and heterosexual Spanish-speaking women, characterised by its commitment to gender equality and LGBTQ+ rights, with feminists using vibrant aesthetics influenced by Japanese and Korean pop culture, as well as Latin symbols and music. The popularity and reach of this subculture, with over 2.3 billion interactions, underscore TikTok’s ability to amplify marginalised, oppressed, and minimised voices in promoting inclusivity.

In contrast, the Fifes represent traditional patriarchal values and are often perceived as macho and homophobic, creating a narrative of resistance between the two groups. This tension reflects broader ideological conflicts in society, showcasing the platform as a cultural battleground where social norms are contested and redefined. However, the Tilinx, as symbolic descendants of the Potaxies, continue the fight for inclusion and diversity, drawing inspiration from the ballroom culture and drag houses. This subculture emphasises the role of the Potaxie “mothers”, who guide and support the new generation, reinforcing values of community, struggle, and cultural resistance.

The qualitative analysis of 200 videos reveals how these subcultures use distinctive narratives and aesthetics to express their identities and challenge social norms. Potaxies and Tilinx, for instance, subvert traditional expectations through humour and cultural critique, while the Fifes represent a conservative reaction to these progressive movements.

Our findings also highlight how TikTok acts as a crucial mediator of intersectional experiences, favouring certain types of content through algorithms that can create visibility biases. Users navigate these limitations and opportunities to express their identities authentically, though they may sometimes face pressure to conform to algorithmic trends, which can lead to a homogenisation of content.

The implications of this study for communication strategies and youth policies are significant. Brands and content creators must understand the complexities of these subcultures to engage effectively and meaningfully with diverse audiences. Moreover, the rapid commercialisation of these subcultures raises important questions about authenticity and resistance, as the market plays an active role in generating and shaping cultural identities.

The study also highlights the importance of exploring how digital subcultures are influenced and commercialised by the market. Traditionally, subcultures emerged as movements of resistance against the dominant culture, but today, the market has an active role in their creation and evolution. This dynamic raises questions about the authenticity and commercialisation of youth identities in the contemporary digital environment.

Finally, the study underscores the importance of continuing research on digital subcultures to better understand their cultural and social impacts. Future research could focus on how the market influences the creation of subcultures and how these, in turn, shape cultural and consumer practices. Additionally, it would be valuable to investigate how digital subcultures can maintain their authenticity and resistance in an increasingly commercialised environment.

This study demonstrates that the Potaxie subculture is not only reshaping cultural practices and identities but is also challenging traditional social structures. Furthermore, it provides a solid foundation for future research and highlights the need for nuanced and informed approaches in academic research and practical applications. Digital subcultures will continue to be a transformative force in shaping contemporary cultural and social narratives.

7. Research Limitations and Future Directions

While this study provides valuable insights into the dynamics of Potaxie, Fifes, and Tilinx subcultures on TikTok, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations. First, the reliance on publicly available data from TikTok means our analysis is shaped by the platform’s algorithm, which influences content visibility and user interaction. This can introduce biases, as the algorithm may promote specific types of content, affecting our dataset’s representativeness. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of this study captures a single period of analysis; future longitudinal research could explore how these subcultures evolve over time, particularly in response to shifting social trends and platform policies.

Another limitation relates to platform specificity. While TikTok serves as a key site for these subcultures, expanding the study to include data from other platforms (e.g., Instagram, Twitch, X…) could provide a more comprehensive view of digital subcultural dynamics. Finally, future research could delve deeper into the impact of TikTok’s commercial partnerships on subcultural content, examining how brand collaborations affect authenticity and engagement within these communities. Addressing these areas in future research will deepen our understanding of the interplay between digital subcultures, platform algorithms, and broader cultural narratives.

Author Contributions

P.S.-R. and C.F.-M.; methodology, P.S.-R.; software, P.S.-R.; validation, P.S.-R. and C.F.-M.; formal analysis, P.S.-R.; investigation, P.S.-R.; resources, C.F.-M.; data curation, P.S.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S.-R.; writing—review and editing, P.S.-R. and C.F.-M.; visualization, P.S.-R.; supervision, C.F.-M.; project administration, P.S.-R. and C.F.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research was approved by the ethics committee of Universidad Complutense de Madrid (UCM).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the reported results in this study are available at Figshare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26362672.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Albarracín-Vivo, D.; Encabo-Fernández, E.; Jerez-Martínez, I.; Hernández-Delgado, L. Gender Differences and Critical Thinking: A Study on the Written Compositions of Primary Education Students. Societies 2024, 14, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegmair, J.; Prybutok, V. Cyberbullying and Resilience: Lessons Learned from a Survey. Societies 2024, 14, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Social Comparison Processes. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmank, J.; Buchkremer, R. Navigating the Digital Public Sphere: An AI-Driven Analysis of Interaction Dynamics across Societal Domains. Societies 2024, 14, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickse, J.; Arpan, L.M.; Clayton, R.B.; Ridgway, J.L. Instagram and college women’s body image: Investigating the roles of appearance-related comparisons and intrasexual competition. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 74, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Valle, M.K.; Gallego-García, M.; Williamson, P.; Wade, T.D. Social media, body image, and the question of causation: Meta-analyses of experimental and longitudinal evidence. Body Image 2021, 39, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, C.B.; Kwitowski, M.A.; Mazzeo, S.E. “I don’t need people to tell me I’m pretty on social media”: A qualitative study of social media and body image in early adolescent girls. Body Image 2017, 23, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- InfoAdex. InfoAdex Study on Advertising Investment in Spain 2023. Available online: https://bit.ly/3OIsi0R (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Ameen, N.; Cheah, J.H.; Kumar, S. It’s all part of the customer journey: The impact of augmented reality, chatbots, and social media on the body image and self-esteem of Generation Z female consumers. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 2110–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe-Calverley, E.; Grieve, R. Do the metrics matter? An experimental investigation of Instagram influencer effects on mood and body dissatisfaction. Body Image 2021, 36, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M.; Anderberg, I.; Brown, Z. Uploading your best self: Selfie editing and body dissatisfaction. Body Image 2020, 33, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durau, J.; Diehl, S.; Terlutter, R. Motivate me to exercise with you: The effects of social media fitness influencers on users’ intentions to engage in physical activity and the role of user gender. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 20552076221102769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohnt, H.; Tiggemann, M. The contribution of peer and media influences to the development of body satisfaction and self-esteem in young girls: A prospective study. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 42, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orth, U.; Robins, R.W. The development of self-esteem. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 23, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.; Greek, C. Mods and rockers, drunken debutants, and sozzled students: Moral panic or the British silly season? Sage Open 2012, 2, 2158244012455177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszak, T. The Making of a Counter Culture: Reflections on the Technocratic Society and Its Youthful Opposition; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1968; Available online: https://archive.org/details/themakingofacult0000unse/page/n7/mode/2up (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- Cohen, S. Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and Rockers; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1972; Available online: https://bit.ly/3ZrQgUP (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Hebdige, D. Subculture: The Meaning of Style; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1979; Available online: https://www.erikclabaugh.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/181899847-Subculture.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Muggleton, D. Inside Subculture: The Postmodern Meaning of Style; Berg: Oxford, UK, 2000; Available online: https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/inside-subculture-9781859733523/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Rose, T. Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America; Wesleyan University Press: Middletown, CT, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J. Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Available online: https://bit.ly/3Mqyt8G (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Bennett, A. Virtual subcultures? Youth, identity and the internet. In After Subculture: Critical Studies in Contemporary Youth Culture; Bennett, A., Kahn-Harris, K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2004; pp. 162–176. Available online: https://bit.ly/4cStI2v (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Boyd, D. It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2014; Available online: https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300166316/its-complicated/ (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Jenkins, H.; Ford, S.; Green, J. Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qfk6w (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- Burgess, J.; Green, J. YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2009; Available online: https://bit.ly/3Mus7oQ (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- Lushey, C. Leaver, T., Highfield, T., & Abidin, C. (2020). Instagram: Visual social media cultures. Cambridge: Polity Press. 264 pp. Communications 2021, 46, 613–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, D.B.V.; Chen, X.; Zeng, H. The Co-evolution of Two Chinese Mobile Short Video Apps: Parallel Platformization of Douyin and TikTok. Mob. Media Commun. 2020, 8, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.A.; Kiene, C.; Middler, S.; Brubaker, J.R.; Fiesler, C. Moderation Challenges in Voice-based Online Communities on Discord. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 2019, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Galera, M.C.; del-Hoyo-Hurtado, M.; Fernandez-Munoz, C. Jóvenes comprometidos en la Red: El papel de las redes sociales en la participación social activa. Comunicar 2014, 22, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, V. Who Cares About Ballroom Dancing? In The Sexual Politics of Ballroom Dancing; Genders and Sexualities in the Social Sciences; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.D.; Marsh, E.E. Content Analysis: A Flexible Methodology. Libr. Trends 2006, 55, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.; Baker, J. Muscles, makeup, and femboys: Analyzing TikTok’s “radical” masculinities. Soc. Media Soc. 2022, 8, 20563051221126040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, S.; Eriksson Krutrök, M. Researching Digital Media and Society. 2024. Available online: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-220689 (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2014; Available online: https://collegepublishing.sagepub.com/products/constructing-grounded-theory-2-235960 (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Gentleman, R. The Promiscuity of Network Culture: Queer Theory and Digital Media [Review of The Promiscuity of Network Culture: Queer Theory and Digital Media, by Robert Payne]. QED A J. GLBTQ Worldmaking 2016, 3, 144–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBean, S. 9. Digital Intimacies and Queer Narratives. In The Edinburgh Companion to Contemporary Narrative Theories; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2018; pp. 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark-Parsons, R.; Lingel, J. Margins as Methods, Margins as Ethics: A Feminist Framework for Studying Online Alterity. Soc. Media Soc. 2020, 6, 2056305120913994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrasher, F.M. Social Backgrounds and School Problems. J. Educ. Sociol. 1927, 1, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, H. Der Aufgang der Menschheit: Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der Religion, Symbolik und Schrift der Atlantisch-Nordischen Rasse, 2nd ed.; Diederichs: Jena, Germany, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Vásconez Merino, G.X.; Carpio, A.; Carpio, J. Representación de la mujer en filmes de comedia negra: Un análisis a través de la Teoría del sexismo ambivalente. Investig. Fem. 2022, 13, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.; Jacques, M. New times. In The Changing Face of Politics in the 1990s; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Maffesoli, M. The Contemplation of the World: Figures of Community Style; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Carpio Ulloa, M.J. Élites neopentecostales trasnacionales: Imaginario geoestratégico del discurso de las superestrellas. Rev. Rupturas 2022, 12, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderrama, A.; Jimenez, J. Tecnología, cultura y resistencia. Rev. Estud. Soc. 2005, 22, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. Internet y la sociedad red. La Factoría 2001, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, B. Fight, Flight, or Chill: Subcultures, Youth, and Rave into the 21st Century; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada; Kingston, ON, Canada, 2006; Available online: https://www.mqup.ca/fight--flight--or-chill-products-9780773530614.php (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Barlow, M.; Clarke, T. Global Showdown: How the New Activists Are Fighting Global Corporate Rule; Stoddart: Mishawaka, IN, USA, 2002; Available online: https://www.amazon.com/-/es/Maude-Barlow/dp/0773732640 (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Klein, N. No Logo: Taking Aim at Brand Bullies; Vintage Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedzviecki, H. We Want Some Too: Underground Desire and the Reinvention of Mass Culture; Penguin: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, G. Justice Do It! The Nike Transnational Advocacy Network: Organization, Collective Actions, and Outcomes. Sociol. Sport J. 1999, 16, 206–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B. Ethnography, the Internet, and Youth Culture: Strategies for Examining Social Resistance and “Online-Offline” Relationships. Can. J. Educ./Rev. Can. L’éducation 2006, 29, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, P. Contemporary youth resistance culture and the class struggle. Crit. Arts 2014, 28, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stald, G. Mobile Identity: Youth, Identity, and Mobile Communication Media. In Youth, Identity, and Digital Media; Buckingham, D., Ed.; The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 143–164. [Google Scholar]

- Best, A. Prom Night: Youth, Schools, and Popular Culture; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Available online: https://bit.ly/3zegGhP (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Bennett, A. Music, Style, and Aging: Growing Old Disgracefully? Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA; JSTOR: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt14bt9rd (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Soler-i-Martí, R.; Ballesté, E.; Feixa, C. Desde la periferia: La noción de espacio social en la movilización sociopolítica de la juventud. Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Soc. Niñez Juv. 2021, 19, 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, D. Youth, Identity, and Digital Media; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; Available online: https://mitpressbookstore.mit.edu/book/9780262524834 (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Prensky, M. Don’t Bother Me, Mom—I’m Learning! Paragon House: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2006; Available online: https://archive.org/details/dontbothermemomi0000pren (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Crovi, D. La apropiación de las tecnologías. El Placer de Navegar. TELOS 2016, 104, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- García Galera, M.d.C.; del Hoyo Hurtado, M.; Fernández Muñoz, C. Las redes sociales en la cultura digital: Percepción, participación, movilización. Rev. Asoc. Española Investig. Comun. 2014, 1, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.J. Basic Concepts of Intercultural Communication, 2nd ed.; Intercultural Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mina, X. Memes to Movements: How the World’s Most Viral Media Is Changing Social Protest and Power; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Memes-Movements-Worlds-Changing-Protest-ebook/dp/B07C6H7BYH (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Balon, R. An Explanation of Generations and Generational Changes. Acad. Psychiatry 2024, 48, 280–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goggin, G. Global Mobile Media; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.; Kim, K.-O. Social media as a tool for social movements: The effect of social media use and social capital on intention to participate in social movements. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwan, B.; Sobre-Denton, M. Virtual Cosmopolitanism: Constructing Third Cultures and Transmitting Social and Cultural Capital Through Digital Media. J. Int. Intercult. Commun. 2011, 4, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, P. Neighbourhood belonging, social class and social media—Providing ladders to the cloud. Hous. Stud. 2015, 30, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Hannerz, U. Other Transnationals: Perspectives Gained from Studying Sideways. Paideuma 1998, 44, 109–123. [Google Scholar]

- Santaolalla Rueda, P. Lograr la equidad en educación a través de competencias interculturales e intersociales. Rev. Fuentes 2019, 21, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo de Mesa, J.; Marcuello-Servós, C.; López Peláez, A.; Méndez Domínguez, P. Social Work and Digital Activism: Sorority, Intersectionality, Homophily and Polarisation in #MeToo. Alternativas. Cuad. De Trab. Soc. 2021, 28, 351–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaun, A.; Uldam, J. Digital activism: After the hype. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 2099–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivitanides, M.; Shah, V. The era of digital activism. In Proceedings of the Conference for Information Systems Applied Research, Wilmington, NC, USA, October 2011; Volume 4, No. 1842. pp. 1–8. Available online: https://bit.ly/3B9Rkmr (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- Yang, G. The Red Guard Generation and Political Activism in China; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stornaiuolo, A.; Thomas, E.E. Disrupting Educational Inequalities Through Youth Digital Activism. Review of Research in Education. 2015. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44668698 (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- Berard, A.A.; Smith, A.P. Post your journey: Instagram as a support community for people with fibromyalgia. Qual. Health Res. 2019, 29, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazi, S.; Filieri, R.; Gorton, M. Social media content aesthetic quality and customer engagement: The mediating role of entertainment and impacts on brand love and loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 160, 113778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horkheimer, M.; Adorno, T.W. Dialéctica de la Ilustración: Fragmentos Filosóficos; Trotta: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, H.M. Estéticas en Tik Tok: Entre lo Histórico y lo Digital. Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Diseño y Comunicación (152). 2022. Available online: https://dspace.palermo.edu/ojs/index.php/cdc/article/download/6688/10521 (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Kennedy, M. ‘If the rise of the TikTok dance and e-girl aesthetic has taught us anything, it’s that teenage girls rule the internet right now’: TikTok celebrity, girls and the Coronavirus crisis. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 2020, 23, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, L.N.; Vollmer Mateus, A.M. Contemporary Ethnographic Aesthetics: The TikTok Turn. Vis. Anthropol. 2024, 37, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggerstedt, M.; Rhee, J.; Urban, M.J.; Mangahas, A.; Smith, R.M.; Revenaugh, P.C. Beauty is in the eye of the follower: Facial aesthetics in the age of social media. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2020, 41, 102643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, W. Obras Walter Benjamin; Abada: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gutfreund, J. Move over, Millennials: Generation Z is changing the consumer landscape. J. Brand Strategy 2016, 5, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1979; Gordon, C., Ed.; Pantheon: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1990; Available online: https://bit.ly/3XhCWj8 (accessed on 7 February 2024).

- Butler, J. Undoing Gender; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004; Available online: https://bit.ly/3XuEOq1 (accessed on 7 February 2024).

- Foucault, M. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison; Sheridan, A., Translator; Random House Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Rue, P. Make way, millennials, here comes Gen Z. About Campus 2018, 23, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debies-Carl, J.S. Are the kids alright? A critique and agenda for taking youth cultures seriously. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2013, 52, 110–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.; Lööw, H. (Eds.) The Cultic Milieu: Oppositional Subcultures in an Age of Globalization. Rowman Altamira. 2002. Available online: https://bit.ly/3ZClGqT (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Brubaker, R. Hyperconnectivity and Its Discontents; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; Available online: https://bit.ly/3XroGVX (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Dimock, M. Defining Generations: Where Millennials End and Generation Z Begins; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://bit.ly/3XquDCJ (accessed on 7 February 2024).

- Barbery Montoya, D.C.; Pastor López, B.A.; Idrobo Zambrano, D.E.; Sempértegui Del Pozo, L.C. Análisis comparativo generacional del comportamiento de compra online. Rev. Espac. 2018, 39, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, Â.M.T.; Azevedo, Â.S.; Rodrigues, A. Influence of Sociodemographic and Social Variables on the Relationship between Formal Years of Education and Time Spent on the Internet. Societies 2024, 14, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, T.; Hoefel, F. True Gen’: Generation Z and its implications for companies. McKinsey Co. 2018, 12. Available online: https://www.drthomaswu.com/uicmpaccsmac/Gen%20Z.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Jenkins, H. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2006; Available online: https://www.dhi.ac.uk/san/waysofbeing/data/communication-zangana-jenkins-2006.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Livingstone, S. Digital and Media Literacy: A Plan of Action; Aspen Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED523244 (accessed on 7 April 2024).