Abstract

In recent social science debates, poverty is seen as a multidimensional phenomenon, not only economic, but also psychological, educational, moral, and relational. The empirical observation and analysis of this latter dimension and its qualities represent a sociological challenge, especially in assessing the integral effectiveness of social projects. As part of this debate, this article proposes an analytical method—based on Social Network Analysis, according to the egocentric or personal approach—and describes its use during an empirical “relational impact assessment” of a specific anti-poverty project in the Northwest region of Argentina. Analysis of the data—collected longitudinally through questionnaires—highlights the changes in the personal “relational configurations” of small entrepreneurs in the tourist area, i.e., the beneficiaries of the project, while also highlighting the emergence of “relational goods”. In this way, this article offers an analytical method to evaluate the “relational impact” of anti-poverty projects in quali–quantitative terms.

1. Introduction

In the recent scientific literature in social science, the concepts of well-being and poverty have been understood as related with economic and non-economic factors [1], and more as a problem of capability rather than a lack of income [2,3,4,5,6]. In other words, in the contemporary socio–political and economic debate, poverty [7] as well as well-being are understood and analyzed as a multidimensional phenomenon [8,9,10,11,12] that includes not just economic or material aspects but also psychological, educational, moral, and socio-relational ones. In the latter sense, poverty and well-being are associated with social exclusion/inclusion and with a lack/availability of relational resources and meaningful relationships, in an instrumental and non-instrumental sense, called “social capital” [13] or “relational goods” [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21], which are recognized today as a fundamental component of well-being and “human flourishing” [22,23,24]. In the scientific literature, the connection between poverty, well-being, and social relationships [25,26,27] is conceived in a double sense. On the one side, relationships are understood as instrumental resources that allow access to material goods or opportunities that would otherwise be impossible to obtain. On the other side, as recent studies have shown, specific typologies of non-instrumental relationships, defined as “relational goods”, are in themselves fundamental components of a good human life. In both senses, social relationships represent a fundamental dimension of human flourishing, and there is an urgent need for effective analytical methods to assess them. The empirical observation of an invisible reality such as social relationships is not easy, especially if we analyze not only the quantity but also the quality of relationships that are good for human life. In the traditional sociological paradigms—methodological holism and individualism, the cognitive perception of this object, especially in the empirical sense, is lacking, leaving it enigmatic [28] and partially invisible. In the attempts to better understand this enigma, innovative epistemological perspectives have recently emerged as a third point of view. Starting from one of the most known of these third perspectives, the Social Network Analysis (SNA) [29,30], integrated with the socio-anthropological Gift paradigm [31], this article proposes an innovative method for empirical observation of social relationships and their quality and offers an instrument to analyze this fundamental dimension of human well-being. The article is structured in three sections. In the first (§2), the innovative analytical method for observing social relationships from a quali-quantitative perspective is described. In the second (§ 3), a relational impact assessment, using a longitudinal analysis applied to an anti-poverty project in Argentina, is presented and discussed. In the third (§4), as a conclusion, the proposed method is introduced for future relational impact assessment activities.

2. An Analytical Method for Quali–Quantitative Social Relational Analysis Based on Social Network Analysis and Gift Paradigm

A quali–quantitative empirical analysis of invisible and enigmatic relational phenomena requires a specific method. This article proposes an innovative analytical method rooted in the well-known Social Network Analysis (SNA) supplemented by the socio-anthropological Gift paradigm. The integrated use of these two perspectives is possible because they present convergent assumptions at ontological and epistemological levels and complementary elements at the methodological level, as highlighted elsewhere [32,33]. A first common assumption, at the ontological level, concerns the conception of social reality and, consequently, of the primary object of analysis. Both approaches conceive social reality as a reticular structure and its fundamental element is the social relationship. A second assumption, at the epistemological level, is a logical consequence. The centrality accorded by both approaches to social relationship places them in an overlapping space between the two traditional sociological approaches (methodological holism and individualism) and integrates the qualitative observation of subjective contents—the motivations and symbolic meanings of social actors—with the quantitative–objective observation of the structure, recomposing the antithesis and highlighting the circularity between micro and macro analytical levels. In light of these elements, it becomes possible, at the methodological level, to integrate the two approaches in which SNA, predominantly understood in its role as a “technique in search of a theory” [34] (p. 397), acts as a specific methodological complement to the Gift paradigm. This integration allows us to distinguish the different relational nuances by observing the structural component (relational configurations) and, at the same time, the individual component (motivations for action) of social relationships, that identify their specific forms and contents as a whole.

2.1. Social Network Analysis: Observing the Structural Dimensions of Relationships

The Social Network Analysis (SNA) is a theoretical and methodological perspective founded on a now solid body of tools for empirical analysis, recognized as fruitful for the study of relational configurations from a structural point of view [35]. A classic definition of ‘network’ originating from the anthropologist J.A. Barnes helps move us from a metaphorical to an operational–analytical use of the concept, expressing the fundamental elements of the SNA perspective as follows:

I imagine a series of ‘points’, some connected by lines. The points represent individuals or sometimes groups, and the lines indicate that people interact with each other. We can certainly think of the whole of social life as constituting such a network.[36] (p. 43)

For each of these elements—points, called nodes; lines, called edges and relationships; and networks, as a whole—SNA lists specific properties. The nodes, i.e., the subjects without which the relationships and, consequently, the networks cannot exist, can be individuals or collective entities (groups, organizations, associations, companies, institutions). They must have specific characteristics: they must be discrete, i.e., separable from each other, belong to the same type of phenomenon, and if heterogeneous, they must be correctly chosen according to their classification [37] (pp. 48–49). In addition to individual attributes, nodes possess specifically relational or positional attributes such as centrality, related to their membership in a set of relationships [38] (p. 44), which expresses the importance of different actors in the network configuration. The edges connecting the nodes according to various contents can be of different typologies [38] (pp. 36–43). In addition to its content, an edge can be characterized by its direction, which can be univocal or bi-univocal (reciprocal), and have either a positive or negative sign, depending on the value of the bond for the nodes. A bond can have weight, to indicate its intensity, and importance; frequency, to indicate the periodicity with which it is activated; and duration, to indicate how long it has existed. These last three properties, taken together, can be considered a measure of another characteristic of the edges, namely, their strength. A set of edges then constitutes what is referred to in this approach as a social relationship. It, in fact, can be defined operationally as the bundle of different edges between couples of subjects [nodes] whose courses of action are mutually oriented [37] (p. 51). Considering the possible co-presence of edges, a relationship can be more or less multiplexity depending on how many links of different contents—which may be mutually consistent or opposite—constitute it. The different global forms that networks take can be characterized by several properties including size, given by the number of nodes composing it; homophily, which expresses the similarity between nodes concerning specific characteristics; density, given by the ratio between existing edges and possible edges; connectivity, which expresses a measure of the connectedness of the network, considering the number of nodes and lines that would be sufficient to disconnect it; and centralization, which measures whether significant variations exist within the network between the centralities of the different nodes and allows us to highlight the extent to which the network is a centralized structure around some specific node. Despite the theoretical robustness of this perspective, the critical analysis points to a limitation of SNA: the unsolved problem of understanding the why of the relationships, i.e., the causal factors of a particular relational configurations and not of others [39] (p. 87), for example, their contents in individual motivational terms. For this reason, the Gift paradigm can represent a very valid theoretical corresponding side [39] (p. 88) for the range of SNA techniques. Both are in complete consonance with a third way of understanding society, which is neither individualistic nor holistic, but a hybrid between the two, a relational one. From this perspective, to understand social phenomena, the analysis must focus not on individuals and their social actions according to a micro-level or individualistic vision, nor on the social structure according to a macro-level or holistic vision, but on the social relationship itself in its different components and qualities, according to a meso-level point of view. It means to grasp circularity, that is, the reciprocal influence between micro- and macro-levels, action, and structure. Within this third point of view is placed the Gift paradigm.

2.2. The Gift paradigm: Distinguishing Different Qualities of Relationships

The Gift paradigm, recently developed to criticize utilitarianism, offers an epistemological perspective—a Third Paradigm [31]—to understand the genesis of social relationships and distinguish in qualitative terms their different typologies. Starting from the anthropological Essay sur le don (1923–1924) of Marcel Mauss [40], the gift—not just an object given by someone to someone else, nor just an individual action of giving, but three social actions of giving, receiving, and giving back—generates a form of exchange between various social actors, called “reciprocity” [41]. In this way, the gift realizes a specific sociological function. It creates and strengthens relationships between individuals and groups. What caught the attention of the first observer of this type of exchange were the mixed motivations of the gift-givers and of the gift-receivers, which simultaneously involved obligation and freedom, gratuitousness, and interest. In other words, the gift exchange contains paradoxical motivations, making the gift a social glue by generating bonds. In this form, the gift assumes the social function of ’sociological and anthropological universal law’ and, from an epistemological point of view, could represent a “strong analytical category [...] in the social sciences” [42] (p. 206). In this sense, the sociologist Alain Caillé proposed a “small ideal-typical theory” of social action [43] (p. 32), based on the gift-exchange dynamics. As an analytical model for observing social phenomena, it suggests that different motivations be taken into account simultaneously, highlighting “how these multiple dimensions of social action, which are obligation, freedom, self-interest and interest in others, intersect” [43] (p. 32). Depending on the different combinations of these motivations, gifts can generate different relational effects, creating different types of relationships that are not always “properly human” and coinciding with “relational goods”. Depending on the dose of the different motivations encompassing social actions [43] (p. 32), the gift could also generate relationships of “power” or “self-interest” [44] (p. 175), insufficient or not entirely positive for humans and social flourishing. The language of the gift allows us to grasp this ambivalence, as shown by the word ‘gift’, which in English means ‘gift’, but in German means ‘poison’: the gift can both gratify and kill [43] (pp. 32–33). The “properly human relationship”—or, in other words, the “relational good”—is a “structure of reciprocity” [45] (p. 198), based on bidirectionality in SNA terms, and characterized by the prevalence of gratuitousness and freedom as motivations and by a predominantly unconditional logic, transforming the cycle of gift exchange into a “spiral” in time [44] (p. 169). This figure emphasizes the founding value of the ‘opening gift’ as totally unconditional and from which all the rest flows by continually reproducing the same logic, even in receiving and giving back, as in an “infinite upward game” [45] (p. 203) that continually nourishes and re-energizes a relationship. In a dynamic of gift exchange, where unconditionality predominates as logic in the action, the obligation is transformed into the Simmelian “gratitude” [46], creating a relational situation called “positive mutual debt” [44] (p. 58). In this relational situation, “the fact of giving back”—founded on reciprocity—tends to dissolve as a principle, to such an extent that, at the limit, in these relationships, a person no longer “gives back” but only “gives” or, on the contrary, a person does no more than “gives back” [44]. In other words, “the difference between giving back and giving being erased or ceasing to be significant. […] positive indebtedness is introduced when the recipient, instead of giving back, gives in turn. Furthermore, even the expression ‘in turn’ is perhaps excessive due to the reference, once again, to alternation. Person passes from the obligation to the desire to give” [44].

2.3. Towards an Integrated Perspective to Analyze Social Relationships and Their Nuances

Starting from the integration of the Social Network Analysis and the Gift paradigm, the analytical approach moves by observing, at the same time, “what circulates” and the “meaning of what circulates” [47] (p. 123), or, in other words, the motivations in individual action of the actors involved in this circulation. In this framework, the social relationships emerge as result of the interaction between two components: a structural one, linked to the form of the social relationship from the point of view of direction—which can be univocal or reciprocal—and an individual one, linked to the motivation of the actors, which can be classified according to the four polarities envisaged by the Gift paradigm, considering the dose of each one. Adopting this perspective, a properly human relationship—coinciding with a “relational good”—is distinguished by the co-presence of two characteristics. The first is that the dynamic of giving–receiving–giving back always remains in a register dominated by gratuitousness and freedom as individual motivations, keeping the exchange in a predominantly unconditional logic without the certainty that the other will accept and reciprocate. The second is that the cycle is not broken, or the spiral is not interrupted so that the form of exchange is maintained, or, in other words, reciprocity remains alive. The first may seem paradoxical if we conceive reciprocity as purely contractual and not as something fueled by unconditionality. According to the “unconditional logic” mentioned above, a relational good could be defined operationally as a relationship with a particular structural form modelled on reciprocity and individually motivated by the prevalence of freedom and gratuitousness. Apprehending this co-presence requires observing not only the level of the object “what circulates” but also going deeper to apprehend its “meaning”, the intention, the motivations of what circulates, and the ‘spirit of the gift’ for the two actors involved in the exchange, carrying out a “relational analysis” [47] (p. 147) taking into account the giver and the recipient. Through this approach, it becomes possible to observe, analyze, qualify, quantify, and grasp the evolution of these invisible realities that are so precious to human and social life and to gain a deeper understanding of the quality of what weaves social phenomena together. To demonstrate this possibility, in the next sections, an empirical application of this analytical proposal in the context of social projects against poverty, also understood as relational deprivation and social exclusion is presented. In this application, according to the theoretical and methodological analytical proposal, a “relational good” was defined as a collaborative interpersonal relationship in a personal social network, independent from the contents (in this case, three typologies were considered: economic, knowledge, facilitation in the creation of other relationships), but dependent on the co-presence of two elements, one structural and one individual (Table 1):

Table 1.

Dimensions of the “relational good”.

(a) bidirectionality (reciprocity) in relationships, undifferentiated in terms of the content of the collaboration;

(b) motivational content (prevalence of freedom and gratuitousness) in the relationships (i.e., in the reciprocal actions).

The first component was detected through a scale consisting of four statements, each indicating the degree of agreement/disagreement with respect to the four motivations of social action defined by the gift perspective (obligation, freedom, interest, gratuitousness) [43] and summarized through an index of unconditionality. The second component, relating to the direction of relationship, was observed, instead, as the percentage of bidirectional collaborative relationships in each personal network summarized as an index of direct reciprocity [48] (p. 66).

3. An Empirical Application: Relational Impact Assessment of the Turismo Sustentable y Solidario en el Nord Oveste Argentino Anti-Poverty Project

The methodological proposal presented can be useful for assessing the results of social projects against poverty in terms of “relational impact”, i.e., ability to improve in quali–quantitative terms the relational dimension of the beneficiaries. Although the proposed method can be applied to the analysis of different phenomena, here it is used to analyze anti-poverty projects and their effects in relational dimension of beneficiaries. This choice derives from the need to introduce in this field a methodological tool to evaluate a fundamental component of multi-dimensional wellbeing, namely the relational one. To demonstrate the usefulness of the methodological proposal in this regard, this article presents an analysis of a specific social project against poverty implemented in North-West Argentina by an Italian NGO, Action for a United World Association (AMU) (see website www.amu-it.eu, accessed on 10 April 2025). The decision to apply the methodological proposal to A.M.U. projects comes from this organization’s need to monitor and evaluate a dimension of well-being particularly important for human development in its vision and according with its evaluation guidelines. The project, called Turismo Sustentable y Solidario en el Nord Oveste Argentino (T.S.N.O.A.), was created in 2015 by the Fundación Comisión Católica Argentina de Migraciones (F.C.C.A.M.) and developed in collaboration with A.M.U. until 2022. T.S.N.O.A. involved communitarian enterprises (emprendimientos) i.e., territorial entrepreneurial groups made up of small entrepreneurs active in the tourist sector (restaurateurs, artisans, tourist guides, accommodation managers) in a territory of three provinces and nine municipalities in north-eastern Argentina and offered professional training and consultancy for business development.

3.1. Research Design and Methodology

In this context, the research design was developed to determine whether the project had a “relational impact” for the small entrepreneur beneficiaries, considered to be the ‘focal nodes’ of the analysis, and contributed to reinforcing the genesis of significant relationships—or relational goods—in their personal social networks. In this sense, an egocentric or personal approach [49,50]—focused on each entrepreneur as ego—was adopted. A sample of 27 entrepreneur members of four emprendimientos (communitarian enterprises)—called Brealito, El Espinal, San Josè, Yariguarenda—was chosen for the analysis according to the criterion of duration in participation in the project: 50% recent participation, 50% ancient participation. Through the use of a questionnaire, applied twice over a period of two years (2019–2021), data were collected. The questionnaire was divided into three sections: Section 1: information about the entrepreneurs and their enterprise; Section 2: information on the quantity and quality of internal relationships in each enterprise; and Section 3: information on the quantity and quality of collaborative external relationships, using tools as name generators and name interpreters [51] to build lists of others, constitutive of personal networks of entrepreneurs. The latter section of the questionnaire is the most interesting in the analysis. Here, the focus was on collaborative relationships with economic/material content but also with a knowledge content, linked to the exchange of knowledge, and with a relational content, linked to facilitation in the creation of new meaningful relationships for the development of business activity.

The interviews were carried out in two phases by trained local project workers:

(1) first phase (January–April 2019): the questionnaire was administered to 27 entrepreneurs belonging to the four communitarian enterprises according to the following territorial distribution: Brealito (3), El Espinal (9), San José (9), Yariguarenda (6).

(2) second phase (April–December 2021): due to difficulties arising from the pandemic, the questionnaire was applied to only 16 entrepreneurs, belonging to the same four communitarian enterprises, according to the same territorial distribution: Brealito (3), El Espinal (5), San José (5), Yariguarenda (3).

The data obtained were analyzed by a team of researchers, using the software Gephi 0.9 [52] and the support of Microsoft Excel 2016, to highlight from a dynamic perspective the changes that occurred in qualitative and quantitative terms in the entrepreneur’s relational configuration and to assess the project’s relational impact on them. It also highlighted the emergence of “relational goods” and identifying the strengths and weaknesses, risks, and opportunities, present or potential.

3.2. Results

From the data analysis, some relevant evidence concerning the relational dimensions of the entrepreneurs, as beneficiaries of the project, emerged and will be presented here with the aim of showing the application of the proposed method, and the awareness that the results may have been influenced by the ongoing pandemic during the time of the research.

A first highlight concerns the change in the dimension of the entrepreneurs’ collaborative networks. The data (Table 2) show that, despite the pandemic, the personal network size was not reduced between the first and second period: the average size of the social networks of the analyzed entrepreneur groups grew from 3.7 to 4.5 between the first and second period. The entrepreneurs who recorded the greatest growth in the network size were those of the emprendimiento of El Espinal and Yariguarenda, while those in Brealito and San Josè decreased.

Table 2.

Personal network size from I to II period (average in each entrepreneur’s group).

Observing the personal network size, differentiated by collaborative content, a quantitative but also qualitative change in relational resources emerges (Table 3). In the area of economic–material collaboration, the network size increased generally, especially for the entrepreneurs in El Espinal and San José; in the area of knowledge exchange or in the area of facilitating the creation of new relationships, the network size increased especially for the entrepreneurs in El Espinal.

Table 3.

Differentiated network size (average in I and II periods).

To further deepen our understanding from a qualitative point of view, it is helpful to observe other relational and network characteristics such as strength of ties. In this sense, an interesting indicator is multiplexity, which expresses the presence of one or more contents in a relationship. According to the hypothesis, a relationship is more robust when the content is more prosperous. In the analysis realized, the number of contents varies from 1 to 3, considering the three types of collaboration observed (economic-material, exchange of knowledge, facilitation in the creation of new relationships). The strength of the relationships that make up the networks of the companies participating in the project changed over the period between the first and second data collection. As Table 4 shows, relationships with a multiplexity of 1 or 2 increased over time, to the detriment of those with a multiplexity of 3, suggesting that the strength of the ties that make up the company networks observed has generally decreased over time. However, these data could also be the result of effects related to the ongoing pandemic during the survey period, so they should be evaluated with caution.

Table 4.

Multiplexity I and II periods (number and average/each communitarian enterprise).

This is true for all entrepreneurs. However, there is no shortage of entrepreneurs with relational configurations that could be described as ‘mixed’, i.e., characterized by a very varied composition in terms of the strength of the ties. This is particularly evident in the case of the Brealito. It is essential to remember that weakening ties do not unequivocally mean a qualitative worsening of ties. The greater fragility of ties over time suggests a specific diversification of the actors offering or receiving collaboration, which could counteract the emergence of dependency ties and favor access to more significant opportunities. Other indicators that express the strength of relationships are the duration of ties and the frequency of contacts. The former shows different trends depending on the communitarian entrepreneur group: it increased over time for Brealito and El Espinal and decreased for San José and Yariguarenda. In the first case, this indicates that the relationships between the entrepreneurs are long-standing and solid; in the second case, this indicates that the companies have more ephemeral relationships, suggesting that new ties have enriched them. Another characteristic of the ties observed concerns their “duration”, a measure that indicates how long the ties have existed. In this work, duration was measured through four gradations, as Table 5 shows. The data highlight that for the entrepreneurs in Brealito and El Espinal, the collaborative relationships are solid, i.e., with a duration of mostly 3 years or more. For the entrepreneurs in San Josè and Yaraguarenda, short relationships grew, suggesting the idea that their collaborative networks were enriched with new ties.

Table 5.

Duration of relationships (% average for each emprendimiento).

The frequency at which collaborative relationships are activated has generally decreased, showing that relationships have been gradually diluted over time, being activated (on average) only monthly for 52% of the ties. Another qualitative indicator involves global networks and is called homophily; in this case, the analysis observed whether the members of the collaborative networks belong to the same emprendimiento, a characteristic that would indicate openness or closedness to collaboration with external organizations and people. As Table 6 highlights, during the considered period, homophily increased, showing a transformation in the composition of the networks to the detriment of the presence of actors from outside the communitarian group (emprendimiento) and with them, the opportunities they could offer for economic development, but with the advantage of greater internal collaboration.

Table 6.

Homophily for each emprendimiento (average and %).

These data confirm that the relational configurations of the entrepreneurs in the four emprendimientos observed have increasingly developed over time a dual tendency between openness and closure towards external actors, with the consequent advantages of both orientations: the possibility of drawing on additional resources than those that could circulate within the emprendimiento itself but also strengthening internal collaboration. About observing the quality of relationships, and especially in terms of “relational goods”, two other indicators are fundamental: direct reciprocity and motivations for acting. As Table 7 shows, direct reciprocity, absent in the first period, is present in the second in two emprendimientos: San José and El Espinal. This shows that dependency has decreased in the networks observed, and the structural component necessary for the emergence of relational goods has developed, although minimally.

Table 7.

Direct reciprocity. Average percentage in each emprendimiento.

Motivations—analyzed using an index of unconditionality (Table 8) in the action that expresses a network’s potential to generate “relational goods”—have generally increased over time (especially in San José). This indicates an increase in the individual component that can favor the emergence of “relational goods”.

Table 8.

Unconditionality index.

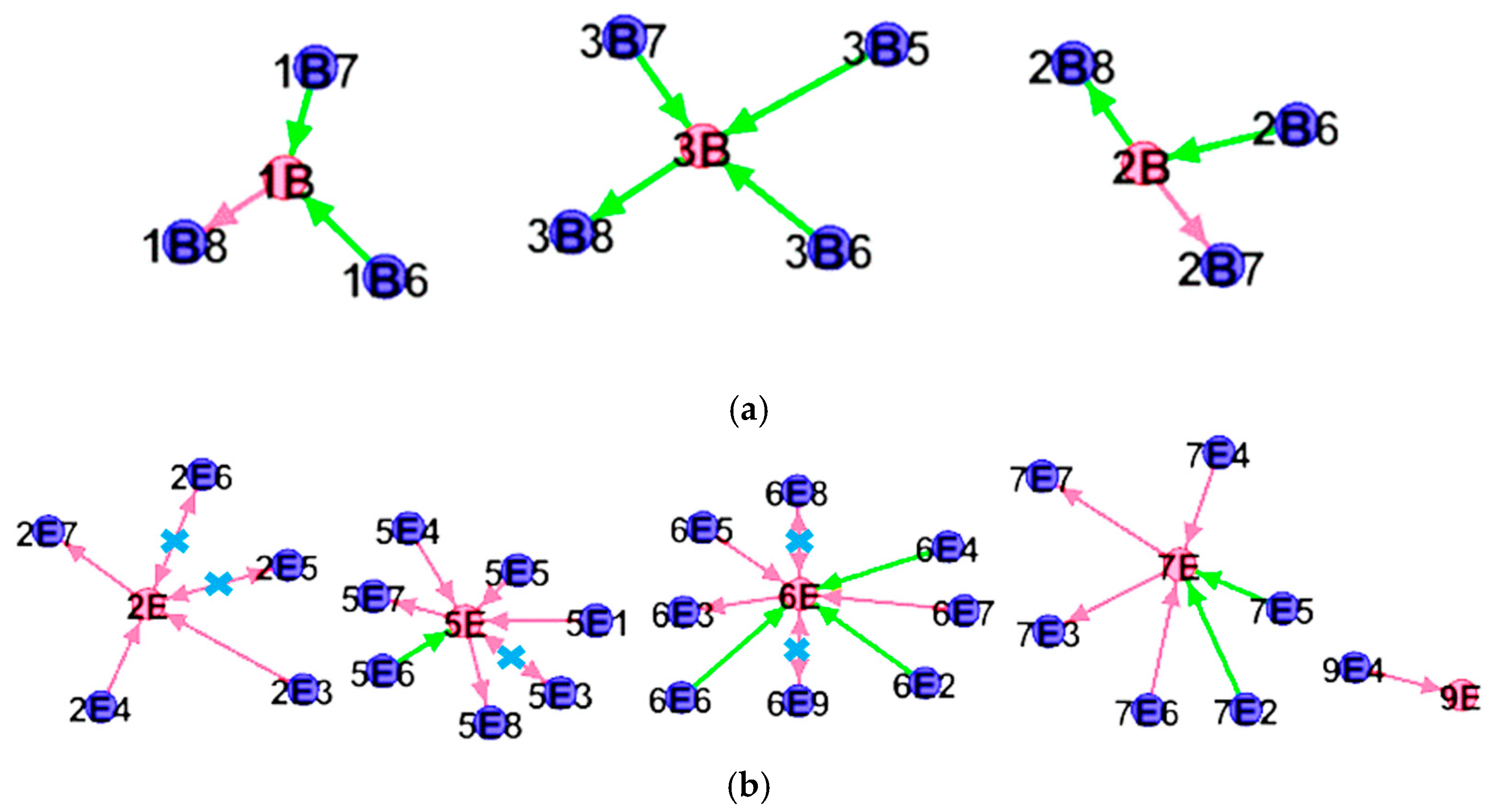

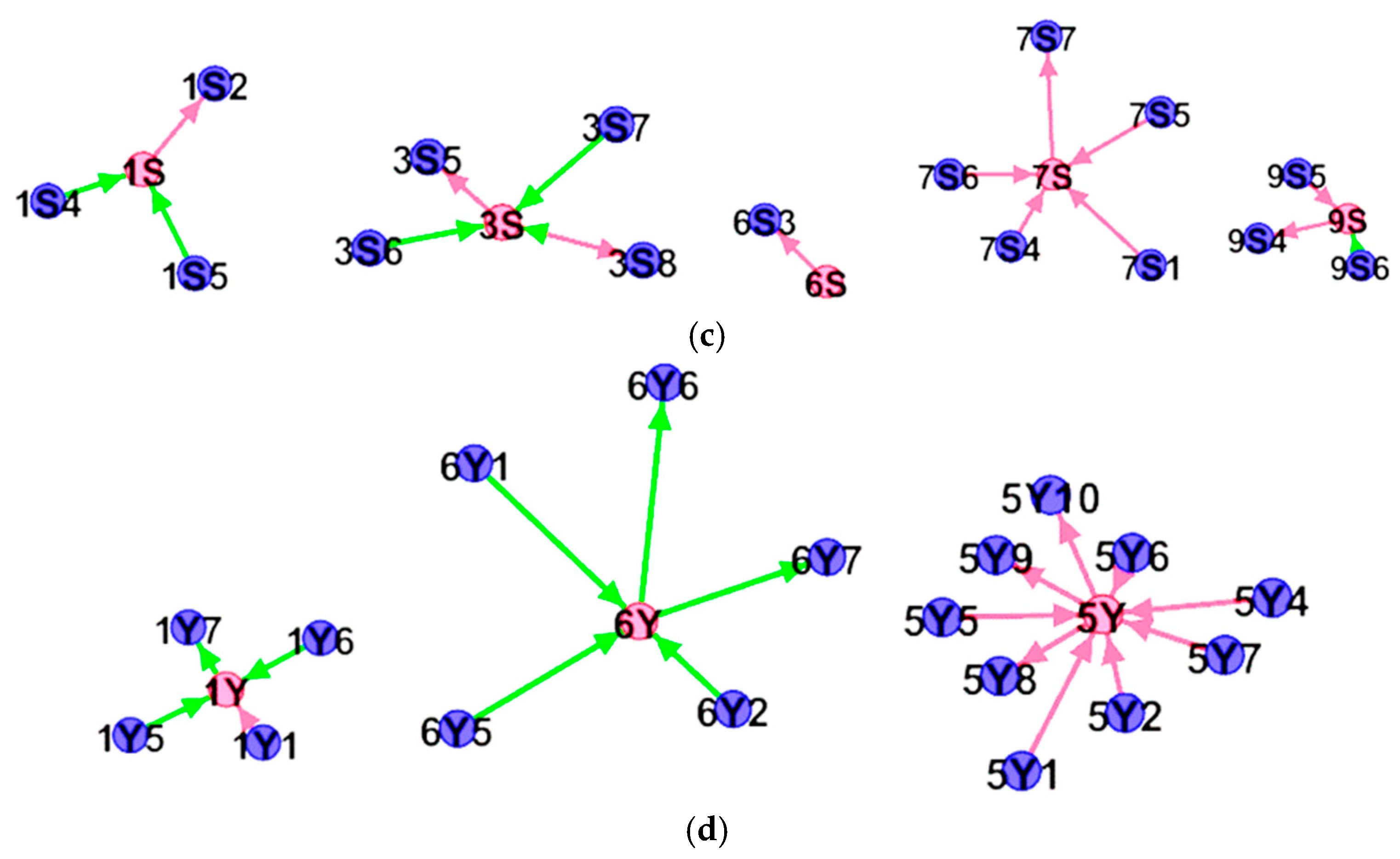

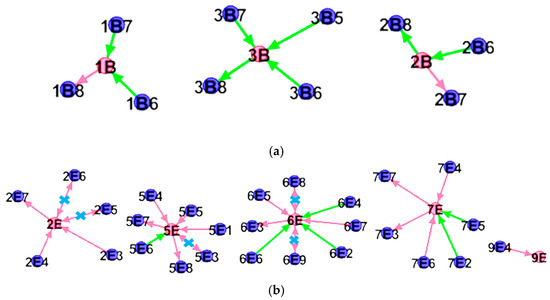

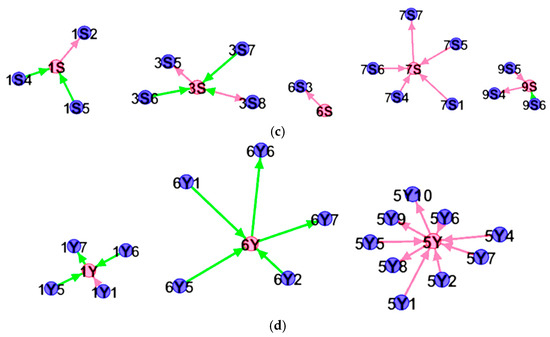

Relational goods, totally absent in the first period, began to be generated. In the second period, this typology of relationships appeared in at least El Espinal, representing 18% of all existing relationships. Figure 1. shows the relational configurations of each enterpreneur in the second period and highlights the presence of “relational goods” (X) for three enterpreneurs in El Espinal (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Relational goods in entrepreneurs’ networks (II period) in each emprendimiento. (a) Entrepreneurs in Brealito (B). (b) Entrepreneurs in El Espinal (E). (c) Entrepreneurs in San Josè (S). (d) Entrepreneurs in Yariguarenda (Y). Legenda: -------- high unconditionality; -------- middle-high unconditionality; ← → reciprocity; X relational good. Source: own elaboration.

Based on the analysis, it is possible to construct a synthetic overview of the evolution of the relational dimension of the entrepreneur beneficiaries of the project in the four emprendimientos. Over the period considered, their relational dimension—considered fundamental for their flourishing—underwent non-uniform variations, partially oriented toward improving the relational ‘stock’ in terms of “relational goods”.

3.3. Discussion

The analytical method proposed, presented in this article as a specific application for analysis of the personal social networks of small entrepreneurs, represents a possibility to make visible a fundamental but not easily observable dimension of well-being: the relational one. Through identification and analysis of its elements (individual and structural), whether in their entirety or as relevant parts, this method permits the identification, by an original operationalization, of “relational good”, a typology of relationships considered fundamental for the well-being, but still poorly analyzed empirically.

This method also permits the identification of other and different relational typologies, i.e., different relational nuances, according to the composition of individual motivations and not to the reciprocal structural form of the relationships, highlighting the emergence of “relationships of interest” or “relationships of power”. In this sense, the proposed method represents a framework of broader applicability that allows us to analyze the quality of relationships, depending on the different combination of motivational content in the relationships and depending on the presence/absence of reciprocal directionality, as Table 9 shows.

Table 9.

Framework for a relational analysis according to proposed method.

From a critical point of view, this method also offers a diagnostic perspective on some relational potentials and relational risks in personal networks that can hinder well-being, such as the creation of relationships of power and, conversely, of dependence, and some opportunities that can be taken advantage of. This method also offers information to modify the social project design. In particular, concerning the possibility of qualitatively improving the relational configuration of entrepreneurs by increasing the presence in their networks of not self-interest relationships, i.e., “relational goods”, the analysis indicates the opportunity to design social interventions aimed at stimulating, on the one hand, reciprocity dynamics and, on the other, at an individual motivational level, cultural reinforcement that encourages the capacity for gratuitousness and freedom in individual action. In the specific analyzed project, the first element was reinforced through specific agreements, Reciprocity Pacts, through which the small entrepreneurs, after receiving aid first (economic support, educational course, consulting) from A.M.U. as a sort of “opening gift”, committed to give in turn, even to third parties other than those from whom they had received. These others probably included in this gift spiral were unknown persons beyond the observation system adopted. The reinforcement of the second element was considered achievable through adequate educational actions.

Methodologically speaking, with appropriate adaptations, this method can be used to analyze other phenomena, in different contexts and integrated with other tools for different cognitive objectives.

Moreover, the analysis highlights some challenges in extending the use of this method.

For instance, the dynamic of transitive reciprocity escapes the proposed analytical approach that instead captures only the presence of direct reciprocity. It would be possible, however, through dynamic network analysis models, based on at least three data collections, to also observe the evolution of this form of extended reciprocity. This possibility represents a challenge for the extension and development of the proposed method.

Another challenge lies in extending the use of this method to analyze not only personal networks, but whole networks. In this case, it would be necessary to restructure the data collection tools and adequately choose the types of networks to analyze, based on the contents that pass through them, while leaving unchanged the classification that defines the motivational contents on the basis of the analytical proposal rooted in the perspective of the gift.

4. Conclusions: Towards an Analytical Method for Observing the (In)Visible and Its Nuances

This article offers an analytical method for observing a fundamental component of wellbeing, the relational dimensions, beyond its invisible and enigmatic nature, which is helpful in evaluating the ‘relational impact’ of anti-poverty projects in quali–quantitative terms. Through an integrated use of Social Network Analysis and the Gift paradigm, it seems possible to outline a perspective to make visible what, in the epistemological perspectives historically developed in the social sciences, would be invisible, namely social relationships and their various qualitative nuances. In particular, this method includes the operationalization of “properly human social relationships” or “relational goods” and permits to identify this typology of relationship as the emerging result of the interaction of a specific “meaning of what circulates”, i.e., a motivation to act at the individual level predominantly in freedom and gratuitousness, and a bidirectional or reciprocal form of “what circulates” between the social actors. If the dominant individual motivations tend towards obligation or interest, and if the exchange is not modelled according to a reciprocal form, they are not properly human relationships, but relationships of “power” or “self-interest” [44] (p. 175) may emerge. The analytical observation is based on a “relational analysis” including “what circulates” and its meaning for all the actors involved. This article uses this perspective to realize a relational impact assessment in a specific field: anti-poverty social projects. However, the proposed analytical method could be helpful to analyze the quality of relational dimension of well-being and the genesis of “relational goods”, a component fundamental to “human flourishing”, supporting the development of a relational impact assessment in different contexts and spheres of social life.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not need a formal ethical approval process because part of the evaluation process of social projects of A.M.U., NGO described in this article.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed not written consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges any support from local interviewers and A.M.U. members.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Leriou, E. Understanding and Measuring Child Well-being in the Region of Attica, Greece: Round four. Child Ind. Res. 2022, 15, 1967–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, A.K. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Leriou, E. Analysis of the Factors That Determine Social Welfare by Implementing an Integrated Decision-Making Framework; Panteion University: Athens, Greece, 2016; Volume 10, (In Greek). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasopoulos, A.; Leriou, E. A new multidimensional model of ethics educational impact on welfare. J. Neural Parallel Sci. Comput. 2014, 22, 595–608. [Google Scholar]

- Michalos, A.C.; Smale, B.; Labonté, R.; Muharjarine, N.; Scott, K.; Moore, K.; Swystun, L.; Holden, B.; Bernardin, H.; Dunning, B.; et al. The Canadian Index of Wellbeing; Technical Report 1.0; Canadian Index of Wellbeing and University of Waterloo: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Leriou, E. Understanding and measuring child well-being in the region of Attica, Greece: Round Five. Child Indic. Res. 2023, 16, 1395–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leriou, E. Multidimensional child poverty in Greece: Empirical findings from the longitudinal implementation of a new multiple indicator during the period 2010–2023. Greek Econ. Outlook (KEPE) 2024, 54, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI). In Unstacking Global Poverty: Data for High Impact Action; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, S. Dimensions of Human Development. World Dev. 2002, 30, 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirksen, J.; Alkire, S. Multidimensional Poverty: Measurement, Analysis, Applications. In Handbook of Labor, Human Resources and Population Economics; Zimmermann, K.F., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, S. The Measurement of Multidimensional Poverty. In Inequality, Polarization and Poverty; Chakravarty, S., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogwang, T.; Lamarche, J.-F. Hybrid measures of multidimensional poverty. Empir. Econ. 2024, 67, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaya, J.; Kelley, E.J. Returns to Relationships. Social Capital and Household Welfare. India Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, L. Relational Goods. In A Lexicon of Social Well-Being; Palgrave Pivot: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, P. Introduzione Alla Sociologia Relazionale; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Donati, P. Discovering the Relational Goods: Their Nature, Genesis and Effects. Int. Rev. Sociol. 2019, 29, 238–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, B. Elements pour une definition d’economie communautaire. Notes Et Doc. 1987, 19–20, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, B. On “Relational Goods”. Strategic Implications of Investment in Relationships. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 1996, XXIII, 260–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlaner, C. Relational goods and participation. Incorporating sociality into the theory of rational action. Public Choice 1989, 62, 253–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M.C. The Fragility of Goodness: Luck and Ethics in Greek Tragedy and Philosophy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Paglione, M.L. Incontri di Valore. I Beni Relazionali e la Loro Emergenza; Pacini Editore: Pisa, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Mill between Aristotle and Bentham. Daedalus 2004, 133, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, G.; Becchetti, L.; Londono-Bedoya, D. Income, Relational Goods and Happiness. Appl. Econ. 2011, 43, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena-Lopez, J.A.; Sanchez-Santos, J.M.; Membiela-Pollan, M. Individual Social Capital and Subjective Wellbeing: The Relational Goods. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 18, 881–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandiera, O.; Burgess, R.; Gulesci, S.; Rasul, I. Community Networks and Poverty Reduction Programmes: Evidence from Bangladesh; LSE STICERD Research Paper n. EOPP015; Suntory and Toyota International Centres for Economics and Related Disciplines: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Cribbs, J.E.; Farber, N.B. Kin Networks and Poverty among African Americans: Past and Present. Soc. Work 2008, 53, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belle, D.E. The Impact of Poverty on Social Networks and Supports. Marriage Fam. Rev. 1983, 5, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, P. L’enigma Della Relazione; Mimesis: Milano, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J. What is Social Network Analysis; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.; Carrington, P.J. The Sage Handbook of Social Network Analysis; Sage Pubblications: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Caillé, A. Il Terzo Paradigma. Antropologia Filosofica Del Dono; Bollati Boringhieri: Torino, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Paglione, M.L. Le relazioni sociali tra dono e analisi di rete: Una proposta epistemologica convergente. Sophia Ric. Su I Fondamenti e laa Correlazione Dei Saperi 2022, 1, 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Paglione, M.L. Convergenze. Beni Relazionali Tra Dono e Analisi Delle Reti Sociali; Città Nuova: Roma, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, R. Teorie Sociologiche; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Salvini, A. L’analisi Delle Reti Sociali. Teorie, Metodi, Applicazioni; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, J.A. Class and Committees in a Norwegian Island Parish. Hum. Relat. 1954, VII, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesi, A.M. L’Analisi Dei Reticoli Sociali; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Vargiu, A. Il Nodo Mancante; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Di Nicola, P. La Rete: Metafora Dell’appartenenza. Analisi Strutturale e Paradigma di Rete; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mauss, M. The Gift; HAU Books: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi, K. The Great Transformation. The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time; Farrar & Rinehart: New York, NY, USA, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini, G. Il dono: Tra economia e società. Aggiorn. Soc. 2004, 55, 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Caillé, A. Note sul paradigma del dono. In L’interpretazione Dello Spirito Del Dono; Grassatelli, P., Montesi, C., Eds.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Godbout, J.T. Lo Spirito Del Dono; Bollati Boringhieri: Torino, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pulcini, E. L’individuo Senza Passioni. Individualismo Moderno e Perdita Del Legame Sociale; Bollati Boringhieri: Torino, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Golino, A.; Paglione, M.L. Povertà e Gratitudine in Georg Simmel. Declinazioni Inedite Della Crisi Postmoderna; Mimesis: Milano, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Godbout, J.T. Quello Che Circola Tra Noi. Dare, Ricevere, Ricambiare; Vita e Pensiero: Milano, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tronca, L. Personal Network in Italia. Sociol. E Politiche Soc. 2012, XV, 55–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, B. The Network is Personal: Introduction to a Special Issue of Social Networks. Soc. Netw. 2007, XXIX, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidart, C.; Degenne, A. Introduction: The Dynamic of Personal Networks. Soc. Netw. 2005, 27, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidart, C.; Charbonneau, J. How to Generate Personal Networks: Issues and Tools for a Sociological Perspective. Field Methods 2011, XXIII, 266–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, M.; Heymann, S.; Jacomy, M. Gephi: An Open Source Software for Exploring and Manipulating Networks. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, San Jose, CA, USA, 17–20 May 2009; Volume 3, pp. 361–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).