Abstract

Background: Medical anthropology is a subfield that examines the various factors influencing health, disease, illness, and sickness. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) encompasses a range of disorders affecting the heart, arteries, and veins. Patients with CVD face significant, unique health challenges, including functional decline, repeated hospitalizations, and psychological and social issues, which contribute to a global decline in health and escalate health system costs. Medical anthropologists have explored this extensive category of diseases in numerous ways, including cross-cultural studies that enhance our understanding of these conditions. Therefore, building on these preliminary insights, this article posed the following research question: How does medical anthropology enhance our understanding, prevention, and management of cardiovascular diseases through cultural, social, and behavioral lenses? Methods: This study examined the research question through a narrative literature review. Results: The literature analysis revealed connections between medical anthropology and specific CVDs: heart disease, hypertension, arterial disease, venous disease, and wound care. Conclusions: The findings from the literature analysis indicate what could be described as the cultural “blood ties” between medical anthropology and cardiovascular disease. In this manner, in the spirit of integration, inter-, and transdisciplinarity, it is increasingly necessary to incorporate mixed-method approaches drawing from both the anthropological and medical fields to better deliver tailored care.

1. Introduction

Medical anthropology is a subfield that analyzes the variables that influence health, disease, illness, or sickness [1,2,3], and the practices and strategies that several social groups have structured to respond to sickness, illness, or disease [1,3]. This discipline uses social sciences and anthropological methods to study illness, healing, and health [1,2]. From a theoretical point of view, medical anthropology includes (but is not limited to) political–economic, biocultural, and interpretive orientations.

For these reasons, “Medical anthropology sits at the intersection of the humanities, social sciences, and biological sciences, seeking to transform our understanding of what matters for people in terms of health and wellbeing. Embracing far-ranging interests generates in-depth knowledge about how people understand health and frame health-related decisions. It also provides a cross-cultural, historical, and developmental lens on health concerning the body and society” [4] (p. 237).

From a historical point of view, over the past 130 years, medical anthropologists have worked in the biomedical dimensions such as research, education, administration, management, and development of community projects, with the scope of training healthcare professionals and changing health results [5].

1.1. The Historical Development of Medical Anthropology: A Cross-Study

Medical anthropology originated within a biomedical context [5], with Havelock Ellis introducing early concepts, emphasizing anthropometric methods for diagnosing diseases, and linking medical anthropology to colonial medicine, madness, and criminality [6,7]. His evolutionary views later influenced eugenics [8]. In contrast, Franz Boas rejected evolutionism, defining culture as a learned and shared system, and establishing four key anthropological areas—cultural, physical, linguistic, and archeological—that shaped medical anthropology [9,10].

Rudolf Virchow, a pioneer in social medicine, analyzed the social determinants of health and advanced vascular medicine [11,12,13,14,15,16]. William Halse Rivers contributed experimental psychological methods and comparative research on diagnosis and disease beliefs [5,17,18]. Until the 1960s, medical anthropologists were primarily physical anthropologists studying disease etiology [5]. A shift toward cultural anthropology occurred in the 1960s–1970s, incorporating multidimensional health definitions and recognizing social and behavioral health influences [1,5]. Hasan and Prasad defined medical anthropology as bridging biological, social, and health sciences [19], while Thomas Weaver distinguished between “anthropology of medicine” (academic research on sociocultural health factors) and “anthropology in medicine” (applied work in medical settings) [20].

Between the 1970s and 1980s, medical anthropology solidified its theoretical foundations within biomedicine [5]. Horacio Fabrega distinguished between “illness” as a social construct and “disease” as a biological condition [21]. Arthur Kleinman framed biomedicine as a cultural system and introduced explanatory models for illness narratives [22,23,24,25], and George Engel developed the biopsychosocial model, integrating social and psychological determinants of disease into medical training [26,27]. By the 1980s, medical anthropology had gained academic recognition, expanding into clinical anthropology, which integrated anthropological perspectives into healthcare training [5,28].

Key contributions since then include Hazel Weidman’s “Transcultural and Health Culture” models [29], James Dow’s “Symbolic Healing” [30], Mark Nichter’s “Idioms of Distress” [31], and Sue Estroff’s “Chronicity” [32]. Howard Stein explored countertransference in physician–patient dynamics [33], Mattingly analyzed narratives in treatment [34], and William Dressler’s “Cultural Consonance Theory” linked culture to conditions like depression and hypertension [35].

Recent topics of interest include the following:

- Culture of Medicine—examining values, metaphors, decision-making, and socialization within medical training [36,37].

- Cultural Competence and Humility—debated by Taylor, who advocates for lifelong learning rather than rigid competence [38,39].

- Social Determinants of Health—pioneered by Michael Marmot, highlighting social class disparities in health outcomes [40,41].

- Structural Violence—Paul Farmer’s work on systemic inequities in healthcare access and outcomes [42].

- Syndemics—Merrill Singer’s framework for analyzing intersecting epidemics shaped by sociopolitical factors, gaining prominence with COVID-19 [43,44,45,46].

1.2. Cardiovascular Disease and Its Socio-Anthropological Impacts: A Brief Overview

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) refers to diseases concerning the heart and/or the arteries and/or the veins [47]. CVD is the leading cause of death globally and is also associated with high rates of morbidity. Patients with CVD deal with significant and unique health issues such as functional decline, recurrent hospitalization, and psychological and social difficulties, thus contributing to global loss of health and essential health system costs [48,49]. Medical anthropologists have studied this broad category of diseases in several ways, such as through cross-cultural studies that improved our understanding of these diseases under the anthropological lens that revealed how culture and social structures may generate obstacles and barriers and the subsequent need to create support and resources to improve the delivery of care for the affected patients. Moreover, medical anthropology studying CVD may help in understanding how macro-level change may have measurable effects at the level of the individual patient and their health status. Medical anthropology studies in CVD are moving toward a research direction aimed at building new theories to discover new dimensions of human health also linked to the biological dimension [50].

Starting from all these preliminary and introductory considerations, this article starts with a research question: how does medical anthropology contribute to the understanding, prevention, and management of cardiovascular diseases through cultural, social, and behavioral perspectives?

In more detail, this narrative review of the literature aims to detect, analyze, and explain the cultural and founding “relationships” of medical anthropology with the field of cardiovascular diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

This article was structured as a narrative literature review. A focused search of international bibliographic sources was conducted using the electronic databases WoS, PubMed, and Scopus, tailored to the objectives of a narrative review. As an additional source, we also used Google Scholar. The aim was to facilitate the analytical integration of studies that highlight the relationship between medical anthropology and cardiovascular disease.

2.2. Search Strategy

The Boolean operator AND was employed to refine the search. The keywords used in the search were as follows: “medical anthropology” AND “cardiovascular disease*”; “medical anthropology” AND “heart”; “medical anthropology” AND vascular; “medical anthropology” AND “vein*”; “medical anthropology” AND “artery”; “medical anthropology” AND “wound*”; “medical anthropology” AND “venous”; “medical anthropology” AND “arterial”; “medical anthropology” AND “blood pressure”. The symbol * represents any number of characters, even zero.

The specific expression was applied to the title, abstract, and keyword fields. The articles included in the search were published without time limits. The search was conducted from 1 November 2024 to 15 January 2025.

2.3. Screening and Selection

The retrieved records were evaluated based on their titles and abstracts. The criteria shown in Table 1 were used for the selection or exclusion of articles.

Table 1.

Inclusion–exclusion criteria.

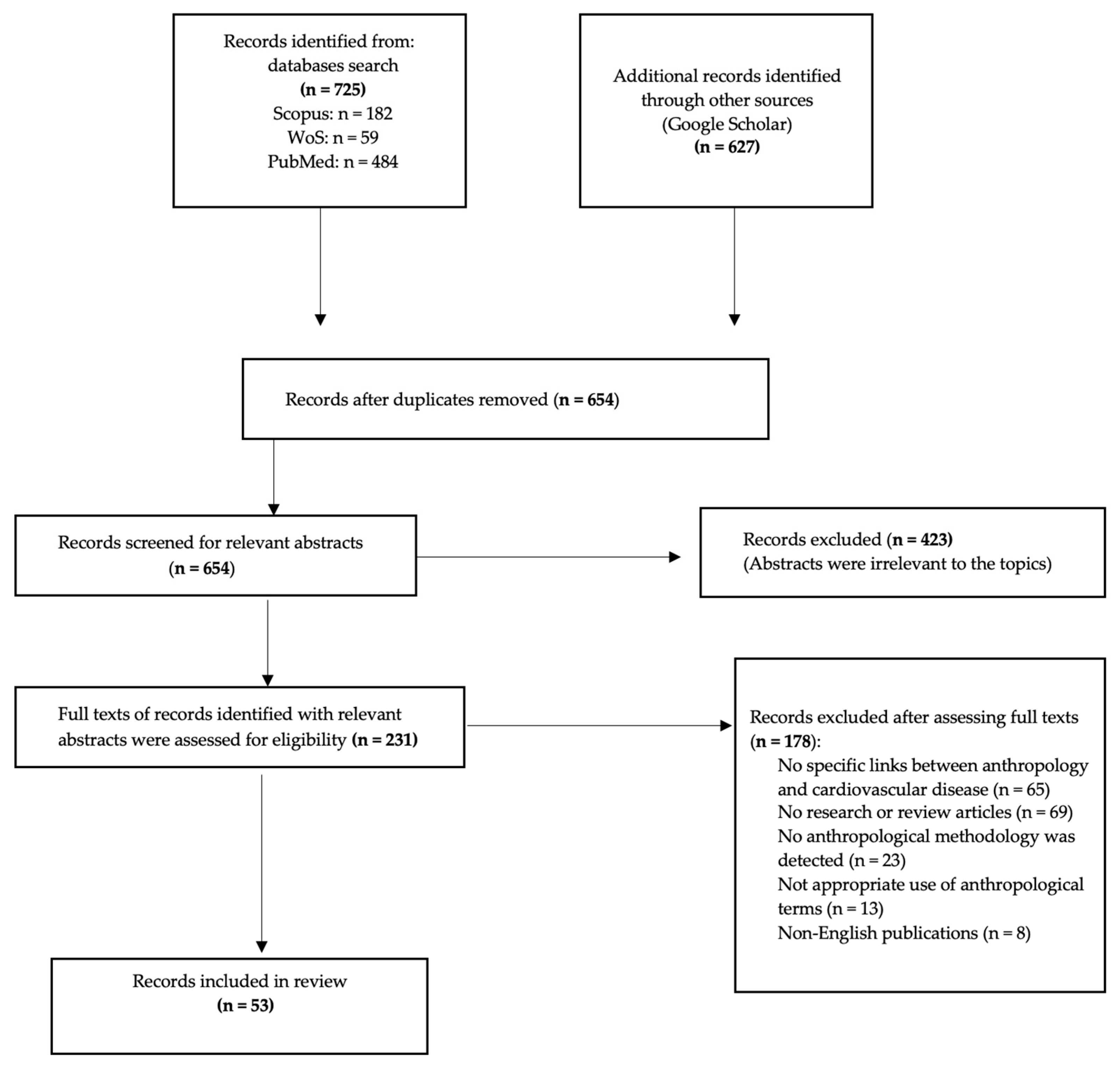

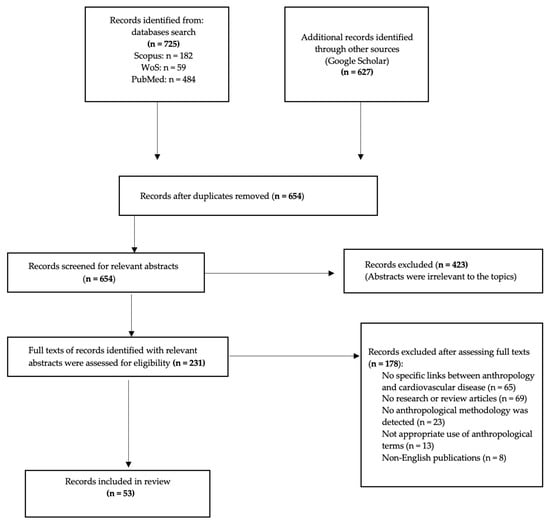

The search strategy is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of article inclusion.

3. Results

The findings related to the most common CVD, structured in themes from clusters of studies, are reported below.

3.1. Coronary Heart Disease and Congestive Heart Failure: Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Coronary heart disease (CHD), also referred to as ischemic heart disease or coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure (CHF), a frequent complication of CHD, are among the most common clinical conditions in patients with heart disease (HD). CHD is a leading cause of mortality, responsible for approximately one-third of all deaths in individuals over 35 in developed countries and accounting for an estimated 1.9 million deaths annually in the European Union. CHF, with a lifetime prevalence of 20% to 45% after the age of 45, significantly contributes to emergency department (ED) visits and is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality [51,52]. Despite advancements in treatment, CHF remains a primary cause of death and disability, with a median survival of 1.66 years in men and 3.17 years in women following disease onset [53].

The rise in HD is influenced by multiple factors, including aging, comorbidities such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, as well as lifestyle choices like tobacco use, alcohol consumption, poor diet, and physical inactivity. Additionally, psychosocial risk factors such as anger, depression, isolation, social inhibition, and a lack of social support are critical in HD onset. Certain personality traits, such as hostility and excessive competitiveness, have also been linked to increased distress and higher morbidity and mortality in cardiac patients [54].

3.1.1. Medical Anthropology and Heart Disease: Ethnographic Insights

Anthropological studies provide valuable insights into the meanings that specific social groups attribute to illness, enhancing the understanding of behaviors, beliefs, and values related to HD and its treatment processes [55]. An ethnographic study by Vila et al. [55] concerning patients undergoing rehabilitation following coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery—a procedure intended to improve cardiac function and symptoms—revealed that HD is often perceived as a biographical rupture. Patients described the condition as a liminal state between life and death, accompanied by feelings of disability, loss of autonomy, and inability to work. These experiences extend beyond the biomedical model, emphasizing the necessity of integrating cultural, economic, moral, and spiritual dimensions into healthcare approaches [55].

One of the most influential contributions to the intersection of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and medical anthropology is Good’s seminal study on the semantics of the heart in Iran [56]. Good argued that prior research had inadequately examined the integration of illness within the language of high medical traditions and distinctive social–symbolic contexts. Using semantic network analysis, he demonstrated that illness categories are structured not merely by their biomedical definitions but through symbolic and experiential associations. Good identified core symbolic elements in Iranian cultural conceptions of heart disease, linking “heart distress” to diverse themes such as old age, sorrow, ritual mourning, poverty-related anxieties, interpersonal conflicts, and emotional distress. His work introduced the concept of core symbols—polysemic elements that structure illness experiences and medical discourse in non-Western societies [56].

3.1.2. Ethnographic Approaches in Cardiac Rehabilitation

For patients undergoing cardiac rehabilitation, an ethnographic approach to healthcare delivery can be beneficial in achieving better social reintegration. This approach broadens the traditional medical history by incorporating cultural understandings of disease, illness, and sickness [57]. Mahoney et al. [53] demonstrated that ethnographic research could aid in understanding CHF patients’ illness experiences, as well as those of their family members. This understanding allows for the development of patient- and family-centered interventions, including improved treatment management, case management support, spiritual care, and targeted educational strategies [53].

A particularly compelling study by Mitola [58] applied ethnographic methods to examine heart transplant patients’ experiences. The author explored the transition from being chronically ill to becoming a “reborn” individual with a transplanted heart. Many transplant recipients struggle with the concept of having received an organ as a “gift” from a deceased donor, leading to what Mitola termed the “tyranny of the gift”—a psychological burden where recipients feel obligated to repay an unreciprocated gesture. Some overcome this by channeling their gratitude into acts of altruism, thus perpetuating the cycle of giving initiated by the donor’s family [58].

3.1.3. Social Determinants of Heart Diseases

The relationship between social and cultural factors and heart diseases has been explored in pioneering studies by Marmot [59,60]. His research demonstrated that social environments could act as triggers for cardiovascular diseases, either by exacerbating stress-related responses or by influencing susceptibility through factors such as social support. For example, the lower prevalence of heart disease in Japan and among Japanese Americans maintaining traditional lifestyles suggests a protective effect of cultural practices. Conversely, in Britain, higher heart disease rates among low-income populations correlate with lower social support and the increased prevalence of conventional coronary risk factors, such as smoking and obesity [59,60].

Helman [61] expanded on these findings, linking personality traits to heart disease risk. He argued that Type A behavior—characterized by ambition, competitiveness, hostility, and social withdrawal—could be viewed as a “culture-bound syndrome” particularly prevalent among middle-aged, middle-class men. This behavioral pattern, shaped by the demands of industrialized society, may significantly contribute to coronary disease development [61].

Preston [62] further applied an ethnographic approach, introducing the concept of the “mindful body” to examine the lived experience of lifestyle changes after coronary artery bypass surgery. Her study underscored the importance of understanding how prescribed medical interventions intersect with patients’ social and cultural contexts, ultimately influencing their adherence to treatment regimens and long-term wellbeing.

3.2. Hypertension: Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Hypertension, defined as elevated arterial blood pressure, affects approximately 1 billion people globally and is the leading risk factor for mortality worldwide. According to World Health Statistics, the prevalence of hypertension is 29.2% in men and 24.8% in women, with an estimated 90% of individuals who are normotensive at age 55 or 65 expected to develop hypertension by age 80–85. Hypertension is responsible for 12.8% of total global deaths, contributing to 51% of cerebrovascular diseases and 45% of deaths due to CHD [63].

While conventional risk factors such as diet, physical activity, and biomedical conditions are well recognized, hypertension also varies substantially based on social and cultural variables [64]. The availability of global population blood pressure data has allowed researchers to correlate hypertension prevalence with societal characteristics, providing valuable insights into how sociocultural complexity influences cardiovascular health [64].

3.2.1. Sociocultural Complexity and Hypertension

One of the most significant findings in cross-cultural research on hypertension is the relationship between societal development and blood pressure levels. Waldron et al. [65] observed that population mean blood pressure tends to be lowest in technologically simple societies—such as those based on hunting, gathering, simple horticulture, and pastoralism—while increasing in sedentary agricultural societies and peaking in complex industrialized societies. Notably, this association remains independent of population-level factors such as age, gender, and body mass index (BMI). The transition from less complex to more modernized societies often leads to increased blood pressure, as seen in migrant populations adapting to urbanized environments [64,66].

This pattern highlights the importance of sociocultural models in understanding disease risk. Cultural changes linked to economic development—often accompanied by shifts in diet, physical activity, smoking habits, and stress levels—can significantly influence hypertension prevalence [67,68]. According to this perspective, modernization-induced lifestyle changes and the stressful nature of cultural transitions contribute to rising hypertension rates in newly industrialized societies [64].

3.2.2. The Role of Psychosocial Stress in Hypertension

Psychosocial stress has been identified as a major determinant of cross-cultural variations in blood pressure. Cultural disruption—defined as the breakdown of cooperative relationships and traditional cultural patterns during modernization—can generate stress that increases hypertension risk [65]. This stress often arises from dissonance between an individual’s early-life social environment and the expectations of later life, particularly in rapidly changing societies.

In Westernized societies, blood pressure tends to rise with age, whereas in many traditional societies, there is no significant correlation between aging and hypertension [65]. Additional psychosocial stressors such as income disparities, education levels, unemployment, home ownership, occupational stress, marital instability, and residential mobility further shape behavioral responses to chronic illness, including hypertension [69]. These factors influence an individual’s adaptive resources in managing chronic diseases and are embedded within the larger cultural context of health and illness [70].

Dow [71] introduced the concepts of “behavioral environment” and “mythic world” to explore how individuals experience chronic illnesses like hypertension within their cultural and social settings. By applying these frameworks, anthropologists can examine how symbolic health phenomena shape illness perceptions and treatment adherence. Moreover, explanatory models, which bridge individual self-perceptions with culturally constructed beliefs, further contribute to understanding how hypertension is experienced and managed across different societies [70,72]. Given its sensitivity to sociocultural factors, hypertension represents a unique focus for medical anthropological research [69].

3.2.3. Ethnographic Perspectives on Hypertension Beliefs and Treatment Adherence

Ethnographic research has provided valuable insights into how individuals perceive hypertension and their adherence to antihypertensive treatments [73]. Blumhagen [74] conducted a seminal study demonstrating that individuals construct personal models of hypertension causation, bodily responses, symptoms, and risks. Despite individual variations, he found commonalities among patients’ beliefs, leading him to develop a visual map of the “folk illness” concept of hypertension. This model linked together fifty-seven different elements, including heart attack, acute stress, and narrowed blood vessels. Blumhagen argued that these lay illness beliefs not only shape personal health perceptions but also serve as a means for individuals to justify social behaviors and assume aspects of the “sick role”. He contrasted this folk model with the biomedical understanding of hypertension, revealing significant differences in how the condition is conceptualized in clinical settings versus patient communities [74].

3.2.4. Cultural Consonance and Hypertension

Expanding on Blumhagen’s findings, Dressler and Bindon [75] introduced the concept of “cultural consonance”—the degree to which individuals align their behaviors with culturally shared beliefs and expectations. Their research examined how cultural consonance in social capital and lifestyle influences blood pressure trends. They found that individuals who conformed more closely to societal models of health-related behaviors exhibited lower blood pressure levels, suggesting a synergistic relationship between cultural adaptation and hypertension risk. Importantly, these associations remained robust even when controlling for other health and socioeconomic variables, reinforcing the idea that cultural dimensions of behavior independently affect health outcomes [75].

3.3. Epidemiology and Clinical Impact of Arterial Disease

Arterial diseases (ADs), including carotid stenosis (CS), peripheral artery disease (PAD), and abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), are significant contributors to morbidity and mortality, representing a major public health burden [76]. These conditions are strongly associated with systemic atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), requiring a multidisciplinary approach to understanding their etiology, risk factors, and disparities in healthcare outcomes.

CS, characterized by the narrowing of carotid arteries due to atherosclerotic plaque buildup, affects approximately 5–7% of individuals over 50 years old. It is a major risk factor for cerebrovascular events such as ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attacks, and it correlates strongly with coronary heart disease (CHD) [76]. PAD, a condition resulting from narrowed or blocked lower limb arteries, impacts over 200 million people worldwide. Clinically, PAD can manifest as intermittent claudication, critical limb ischemia, or acute limb ischemia, which may lead to severe complications such as limb amputation and increased cardiovascular mortality [76]. AAA, defined by the dilation of the abdominal aorta, poses a significant risk of rupture, with fatality rates ranging between 53% and 63% when this occurs [76]. Despite advancements in medical and surgical interventions, ADs remain complex and multifactorial diseases, with several contributing elements that are yet to be fully elucidated.

3.3.1. Social Determinants of Health and Disparities in Arterial Disease

Beyond biomedical factors, the onset and progression of ADs are also influenced by SDHs, which contribute to health inequities and shape clinical outcomes. Key SDHs impacting vascular diseases include socioeconomic status (SES), ethnicity, and gender, all of which interact with other stratification variables that can modify disease prevalence, severity, and treatment accessibility [77].

For both CS and AAA, SES plays a critical role. Lower SES is associated with an increased risk of disease onset due to factors such as poor dietary habits, limited access to preventive healthcare, and inadequate screening measures [77]. Moreover, ethnicity influences mortality outcomes in AAA cases. Studies indicate that black patients tend to receive lower-quality hospital care, often undergoing procedures performed by less experienced surgeons and experiencing poorer postoperative outcomes compared to white patients [77,78,79,80,81].

Ethnic and socioeconomic disparities are also pronounced in PAD. The incidence of PAD is 1.6 times higher in black populations than in white populations, and black patients with PAD are more likely to develop comorbidities and undergo limb amputation [77,82]. Additionally, low SES and rural residency are independent risk factors for worse PAD outcomes, likely due to financial barriers and logistical challenges in accessing healthcare services compared to patients in urban environments [77,82].

3.3.2. Integrating Sociomarkers and Biomarkers in Arterial Disease Management

The relationship between SDHs and biological processes underlying vascular diseases suggests that social factors function as sociomarkers, influencing disease risk, progression, and management. Integrating sociomarkers with traditional biomarkers could enhance predictive models for disease onset, evolution, and patient follow-up, offering a more comprehensive framework for vascular disease management [77,83,84].

3.3.3. Cultural Competence in Arterial Disease Care

Given the strong link between ADs and disadvantaged social, ethnic, and economic backgrounds, cultural competence in medicine plays a crucial role in addressing healthcare disparities [85,86,87]. Cultural competence refers to the ability of healthcare providers to offer care that is tailored to the values, beliefs, and behaviors of diverse patient populations [87]. This is particularly relevant for arterial diseases, as these conditions disproportionately affect marginalized groups, who often experience barriers to effective treatment and preventive care [86,87]. Despite significant advancements in vascular procedures, ethnic disparities persist in treatment outcomes, emphasizing the need for culturally informed healthcare strategies to ensure equitable patient care [87].

3.4. Medical Anthropology and Venous Disease

Venous diseases encompass a diverse range of conditions, with chronic venous disease of the lower extremities (LECVD) being the most prevalent. LECVD refers to pathological and hemodynamic alterations in the leg veins, leading to a spectrum of clinical manifestations. These range from mild symptoms such as telangiectasias, reticular veins, and varicose veins (VVs) to more severe forms of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI), including skin changes and chronic venous leg ulcers (CVLUs). The prevalence of LECVD is notably high, affecting up to 57% of men and 77% of women in the general adult population [88,89,90].

The economic burden of LECVD is significant worldwide. In the United States alone, CVI-related disability leads to an estimated annual loss of two million workdays, while the cost of treating CVLUs exceeds USD 15 billion annually. Research indicates that male sex and low SES are strong predictors of CVI, underscoring the need for tailored treatment approaches that consider gender, ethnicity, and SES disparities [77,91,92]. Additionally, LECVD’s widespread prevalence can impact multiple aspects of an individual’s life [93,94].

A key issue in venous disease management is the general lack of awareness among patients. Many individuals are more likely to recognize arterial conditions than venous diseases, leading to an underestimation of LECVD and its complications [95]. Studies using explanatory models [22] have helped capture these patient experiences and highlight the need for better education and awareness [95]. Despite its prevalence, venous disease remains under-researched compared to arterial diseases, contributing to gaps in knowledge and treatment approaches [77].

Ethnographic research has provided valuable insights into the social dimensions of LECVD. Costa et al. [96] conducted a study on 16 patients with LECVD, exploring the role of social capital in disease management. Their findings revealed that bridging social capital (friend networks) was perceived as more supportive in managing LECVD than bonding social capital (family networks). Additionally, the study highlighted a complete lack of awareness among patients regarding associations or support groups for LECVD. This underscores the importance of ethnographic approaches in uncovering lesser-known aspects of venous disease management, which may not be captured through conventional research methods [96].

3.5. Medical Anthropology and Wound Care

Vascular ulcers (VUs) are advanced complications of major vascular diseases such as chronic venous disease of the lower extremities (LECVD), peripheral artery disease (PAD), and diabetic foot (DF). Chronic venous leg ulcers (CVLUs), which develop in the later stages of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI), affect approximately 1% to 2% of the global population, with prevalence increasing to 4% among individuals over 65 years old [89,97]. Meanwhile, critical limb ischemia (CLI), the most severe form of PAD, affects 1.3% of the adult population, with up to 40% of patients requiring amputation due to arterial or ischemic ulcers [98]. Diabetic foot (DF) is also a significant global concern, affecting around 6% of the population. Among those diagnosed, one in six will develop a diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) [99]. Research highlights that factors such as gender disparities, socioeconomic status (SES), social capital, cultural beliefs, healthcare barriers, the lack of education, fear, and disease acceptance all influence wound care choices and outcomes for vascular ulcers [99,100]. From an anthropological perspective, wounds are not merely physical conditions but relational and social phenomena. The terms “wound”, “wounding”, and “wounded” serve as markers of an individual’s status, actions, and experiences, making them both clinical and social constructs [101]. Medical anthropology frequently engages with these concepts due to its close connection with medicine, and wounds have become a focal point for exploring the intersection of suffering, identity, and healthcare [101].

A recent ethnographic study by Costa et al. [100] applied Turner’s concept of “social skin” [102] to the experience of DFUs. The study suggests that the social skin represents the boundary between an individual and others, as well as the internal divide between personal desires and socially constructed identities. When a person develops a DFU, their altered physical state can reshape their relationships with family members and healthcare providers [100]. Additionally, the study underscores the cultural perception of odors associated with DFUs, as smell plays a critical role in shaping human cognition, behavior, and social interactions. Beyond the biomedical perspective, cultural and social dimensions influence how societies perceive illness, value systems, and psychological responses to disease [100]. Lastly, this research highlights another key area of interest in medical anthropology: the role of traditional and alternative medicine in managing DFUs [100].

4. Conclusions

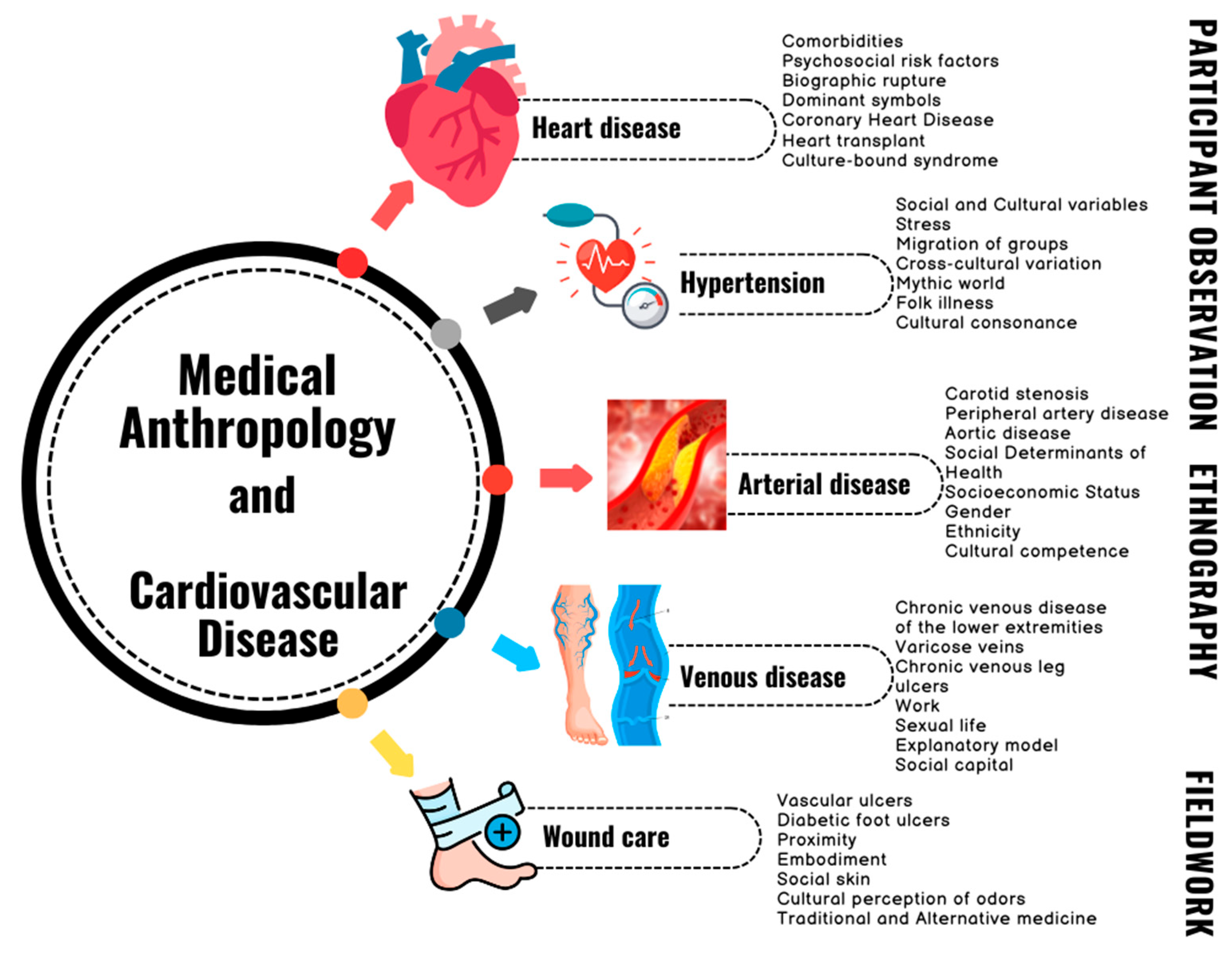

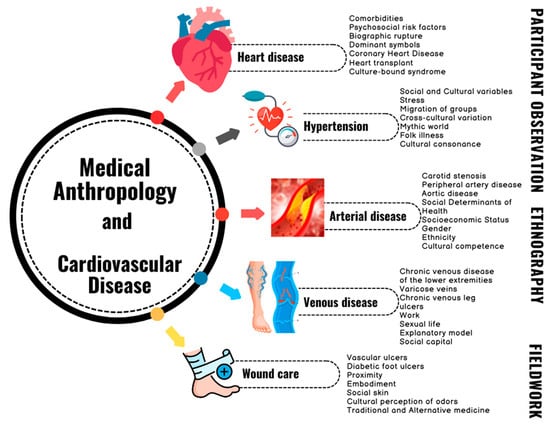

The results obtained from the literature analysis show what could be defined as the cultural “blood ties” between medical anthropology and cardiovascular disease, and Figure 2 shows an overview of the main findings.

Figure 2.

Overview of the main findings.

Thus, medical anthropology, akin to the broader field of medical humanities, seeks to bridge the often stark divide between the social and biomedical sciences, offering a holistic lens through which to explore health issues. Its aim is not merely to understand the biological processes underpinning diseases but to consider the broader social, cultural, and environmental contexts that shape human health. Originating within the confines of the biomedical framework, medical anthropology has gradually evolved into a dynamic, transdisciplinary field, one that emphasizes the intricate interplay between biology, culture, and society [103]. Over the decades, it has come to intersect significantly with the study of CVD, an area where anthropologists have made critical contributions to both theory and practice. These contributions have not only advanced our understanding of health disparities but also reshaped approaches to treatment and prevention within the cardiovascular domain.

Historically, medical anthropology has been pivotal in challenging the limitations of scientific reductionism, which tends to simplify the complex and multifaceted nature of health issues by focusing solely on biological factors [104]. By introducing key concepts such as social context, culture, explanatory models, cultural competence, and the SDHs, medical anthropologists have broadened the scope of cardiovascular research. These concepts have prompted a deeper exploration of how societal factors, beyond individual lifestyle choices or genetic predisposition, influence the risk, onset, and progression of CVD. This more nuanced approach recognizes that health is not simply a product of biology but also of the social, cultural, and economic environments in which individuals live [105].

Incorporating the insights of medical anthropology into cardiovascular research and care provides an opportunity to enhance both the understanding and treatment of CVD. By forming interdisciplinary teams that draw on cultural, social, and economic perspectives, healthcare professionals can better understand the diverse ways in which CVD manifests across different populations. Such teams can develop more personalized care strategies, ensuring that treatments are not only medically sound but also culturally appropriate and socially sensitive. This would enable healthcare providers to tailor their approaches to the specific needs of patients, considering their social contexts and cultural backgrounds, which can significantly influence health outcomes [106].

Looking ahead, the future of cardiovascular research and treatment would benefit from further collaboration between the fields of medical anthropology and biomedicine. This partnership could foster a more integrated approach to health, one that recognizes the complexity of CVD as both a medical and a social phenomenon. Future studies could place greater emphasis on mixed-methods research, combining qualitative insights from anthropology with quantitative data from medical research to provide a fuller understanding of cardiovascular health. Such an approach would promote more comprehensive, personalized care, ensuring that interventions not only address the biological factors of disease but also consider the lived experiences and social realities of patients. In doing so, the collaboration between medical anthropology and cardiovascular health holds the potential to revolutionize how we understand, prevent, and treat CVD, leading to more effective and equitable healthcare practices [107].

In conclusion, the relationship between medical anthropology and CVD has paved the way for a more inclusive and context-sensitive approach to health. By blending the biological and social dimensions of health, medical anthropology enriches our understanding of CVD, particularly in marginalized populations. As the field continues to evolve, it is crucial that future research and clinical practice continue to integrate cultural and social factors into cardiovascular care, ensuring that health interventions are as diverse and individualized as the people they are designed to serve. The continued development of interdisciplinary and mixed-methods approaches will be essential in fostering a more just and comprehensive healthcare system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C. and R.S.; methodology, D.C. and R.S.; validation, D.C. and R.S.; formal analysis, D.C. and R.S.; investigation, D.C. and R.S.; resources, D.C. and R.S.; data curation, D.C. and R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.C. and R.S.; writing—review and editing, D.C. and R.S.; visualization, D.C. and R.S.; supervision, D.C. and R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Costa, D.; Serra, R. Implementing Twaddle Triad to Reach a New Framework for an Integrative and Innovative Medicine. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 4907–4923. [Google Scholar]

- Bhasin, V. Medical anthropology: A review. Stud. Ethno-Med. 2007, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, H.A.; Singer, M.; Susser, I. Medical Anthropology and the World System: Critical Perspectives; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Panter-Brick, C.; Eggerman, M. The field of medical anthropology in Social Science & Medicine. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 196, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martinez, I.; Wiedman, D.W. (Eds.) Anthropology in Medical Education: Sustaining Engagement and Impact; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, D.; Serra, R. What Role Does Medical Anthropology Play in Medical Education? A Scoping Review. Societies 2024, 14, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, H. The place of anthropology in medical education. Lancet 1892, 140, 365–366. [Google Scholar]

- Crozier, I. Havelock Ellis, Eugenicist. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. C Stud. Hist. Philos. Biol. Biomed. Sci. 2008, 39, 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Stocking, G.W., Jr. Franz Boas and the culture concept in historical perspective 1. Am. Anthropol. 1966, 68, 867–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, P.A.; Murphy, L.D. A History of Anthropological Theory, 5th ed.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, K.W. Rudolf Virchow as a pioneer of both biomedicine and social medicine. Scand. J. Public Health 2022, 50, 873–874. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, E.; Scott, M. The life and work of Rudolf Virchow 1821–1902: “Cell theory, thrombosis and the sausage duel”. J. Intensive Care Soc. 2017, 18, 234–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, H.A. Rudolf Virchow, not just a pathologist: A re-examination of the report on the typhus epidemic in Upper Silesia. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 1997, 1, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Safavi-Abbasi, S.; Reis, C.; Talley, M.C.; Theodore, N.; Nakaji, P.; Spetzler, R.F.; Preul, M.C. Rudolf Ludwig Karl Virchow: Pathologist, physician, anthropologist, and politician. Implications of his work for the understanding of cerebrovascular pathology and stroke. Neurosurg. Focus 2006, 20, E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagot, C.N.; Arya, R. Virchow and his triad: A question of attribution. Br. J. Haematol. 2008, 143, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rivers, W.H.R. Kinship and Social Organization; Athlone Press: London, UK, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Rivers, W.H.R. Medicine, Magic and Religion; Lancet XCIV 59–65; Routledge: London, UK, 1916; pp. 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, A. History and Theory in Anthropology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, K.A.; Prasad, B.G. Place of anthropology in medical education. J. Med. Educ. 1961, 36, 940–942. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, T. Medical Anthropology: Trends in Research and Medical Education. In Essays on Medical Anthropology; University of Georgia Press: Athens, GA, USA, 1968; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Fabrega, H., Jr. Toward a model of illness behavior. Med. Care 1973, 11, 470–484. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman, A.M. Some issues for a comparative study of medical healing. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 1973, 19, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kleinman, A. Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture: An Exploration of the Borderland Between Anthropology, Medicine, and Psychiatry; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman, A.; Eisenberg, L.; Good, B. Culture, illness, and care: Clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Ann. Intern. Med. 1978, 88, 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman, A.; Benson, P. Anthropology in the clinic: The problem of cultural competency and how to fix it. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, e294. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, G.L. The biopsychosocial model and medical education: Who are to be the teachers? N. Eng. J. Med. 1982, 306, 802–805. [Google Scholar]

- Maretzki, T.W. Reflections on clinical anthropology. Med. Anthropol. Newsl. 1980, 12, 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Weidman, H.H. Concepts as strategies for change. Psychiatr. Ann. 1975, 5, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dow, J. Universal aspects of symbolic healing: A theoretical synthesis. Am. Anthropol. 1986, 88, 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Nichter, M. Idioms of distress revisited. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 2010, 34, 401–416. [Google Scholar]

- Estroff, S.E. Transformations and reformulations: Chronicity and identity in politics, policy, and phenomenology. Med. Anthropol. 2001, 19, 411–413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stein, H.F. Clinical anthropology and medical anthropology. Med. Anthropol. Newsl. 1980, 12, 18–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, C. Healing Dramas and Clinical Plots: The Narrative Structure of Experience; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, W.W. Cultural consonance: Linking culture, the individual and health. Prev. Med. 2012, 55, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.S. The story catches you and you fall down: Tragedy, ethnography, and “cultural competence”. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2003, 17, 159–181. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A. Listening-touch, affect and the crafting of medical bodies through percussion. Body Soc. 2016, 22, 31–61. [Google Scholar]

- White, A.A., 3rd; Logghe, H.J.; Goodenough, D.A.; Barnes, L.L.; Hallward, A.; Allen, I.M.; Green, D.W.; Krupat, E.; Llerena-Quinn, R. Self-Awareness and Cultural Identity as an Effort to Reduce Bias in Medicine. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparit. 2018, 5, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.S. Confronting “culture” in medicine’s “culture of no culture”. Acad. Med. 2003, 78, 555–559. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M.G.; Smith, G.D.; Stansfeld, S.; Patel, C.; North, F.; Head, J.; White, I.; Brunner, E.; Feeney, A. Health Inequalities among British Civil Servants: The Whitehall II Study. In Stress and the Brain; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, R. Social Determinants of Health: The Solid Facts; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, P. Infections and Inequalities: The Modern Plagues; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, M. AIDS and the health crisis of the US urban poor; the perspective of critical medical anthropology. Soc. Sci. Med. 1994, 39, 931–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, M. Introduction to Syndemics: A Critical Systems Approach to Public and Community Health; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gandra, S.; Ram, S.; Levitz, S.M. The “Black Fungus” in India: The emerging syndemic of COVID-19–associated mucormycosis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 1301–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamorro Garcia, K.; Gonzalez, B.; Healey, J.A.; Gordon, L.; Brault, M.P.; Barreto, E.A.; Torres, C.G. Moving Beyond Mandatory Modules: Authentic Discussions About Racism and Health Equity at a Large Academic Medical Center. Health Equity 2025, 9, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, R.; Ielapi, N.; Barbetta, A.; Andreucci, M.; de Franciscis, S. Novel biomarkers for cardiovascular risk. Biomark. Med. 2018, 12, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osokpo, O.; Riegel, B. Cultural factors influencing self-care by persons with cardiovascular disease: An integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 116, 103383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaduganathan, M.; Mensah, G.A.; Turco, J.V.; Fuster, V.; Roth, G.A. The Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk: A Compass for Future Health. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 2361–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, W.W. Culture, stress, and cardiovascular disease. In Encyclopedia of Medical Anthropology; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 328–334. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira-González, I. The epidemiology of coronary heart disease. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2014, 67, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottlieb, M.; Moyer, E.; Bernard, K. Epidemiology of heart failure presentations to United States emergency departments from 2016 to 2023. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 86, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, J.S. An ethnographic approach to understanding the illness experiences of patients with congestive heart failure and their family members. Heart Lung J. Critical Care 2001, 30, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shruti, C.; Krishan, S.; Sharma, Y.P. Biopsychosocial experiences based on perception of coronary artery disease patients: A medical anthropological study. Res. J. Recent Sci. 2015, 4, 240–245. [Google Scholar]

- Vila, V.D.S.C.; Rossi, L.A.; Costa, M.C.S. Heart disease experience of adults undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Rev. Saúde Pública 2008, 42, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Good, B.J. The Heart of What’s the Matter: The Semantics of Illness in Iran 1. In Medical Anthropology; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 89–122. [Google Scholar]

- Free, M.M. An anthropological perspective on some cultural aspects of cardiac rehabilitation. In Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings; Taylor & Francis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1990; Volume 3, pp. 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mitola, M.E. Frammenti di corpi: Un’indagine antropologica sui trapianti di cuore. AM. Riv. Della Soc. Ital. Antropol. Med. 2013, 15, 309–326. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M.G.; Syme, S.L. Acculturation and coronary heart disease in Japanese-Americans. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1976, 104, 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmot, M.G. Stress, social and cultural variations in heart disease. J. Psychosom. Res. 1983, 27, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helman, C.G. Heart disease and the cultural construction of time: The type A behaviour pattern as a Western culture-bound syndrome. Soc. Sci. Med. 1987, 25, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preston, R.M. Ethnography: Studying the fate of health promotion in coronary families. J. Adv. Nurs. 1997, 25, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J. Epidemiology of hypertension. Clin. Queries Nephrol. 2013, 2, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, W.W.; Santos, J.E.D. Social and cultural dimensions of hypertension in Brazil: A review. Cad. Saúde Pública 2000, 16, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, I.; Nowotarski, M.; Freimer, M.; Henry, J.P.; Post, N.; Witten, C. Cross-cultural variation in blood pressure: A quantitative analysis of the relationships of blood pressure to cultural characteristics, salt consumption and body weight. Soc. Sci. Med. 1982, 16, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.P.; Cassel, J.C. Psychosocial factors in essential hypertension recent epidemiologic and animal experimental evidence. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1969, 90, 171–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, W.W. Psychosomatic symptoms, stress, and modernization: A model. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 1985, 9, 257–286. [Google Scholar]

- Cassel, J.; Patrick, R.; Jenkins, D. Epidemiological analysis of the health implications of culture change: A conceptual model. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1960, 84, 938–949. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dressler, W.W. Part three: “Disorganization”, adaptation, and arterial blood pressure. Med. Anthropol. 1979, 3, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heurtin-Roberts, S. ‘High-pertension’—The uses of a chronic folk illness for personal adaptation. Soc. Sci. Med. 1993, 37, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dow, J. Symbols, Soul, and Magical Healing among the Otomí Indians. J. Lat. Am. Lore 1984, 10, 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Blumhagen, D.W. On the nature of explanatory models. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 1981, 5, 337–340. [Google Scholar]

- Sarradon-Eck, A.; Egrot, M.; Blance, M.A.; Faure, M. Anthropological approach of adherence factors for antihypertensive drugs. Healthc. Policy 2010, 5, e157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blumhagen, D. Hyper-tension: A folk illness with a medical name. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 1980, 4, 197–227. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, W.W.; Bindon, J.R. The health consequences of cultural consonance: Cultural dimensions of lifestyle, social support, and arterial blood pressure in an African American community. Am. Anthropol. 2000, 102, 244–260. [Google Scholar]

- Scalise, E.; Costa, D.; Gallelli, G.; Ielapi, N.; Turchino, D.; Accarino, G.; Faga, T.; Michael, A.; Bracale, U.M.; Andreucci, M.; et al. Biomarkers and Social Determinants in atherosclerotic Arterial Diseases: A Scoping Review. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.; Ielapi, N.; Bevacqua, E.; Ciranni, S.; Cristodoro, L.; Torcia, G.; Serra, R. Social Determinants of Health and Vascular Diseases: A Systematic Review and Call for Action. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, N.H.; Upchurch, G.R., Jr.; Mathur, A.K.; Dimick, J.B. Explaining racial disparities in mortality after abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009, 50, 709–713. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Osborne, N.H.; Upchurch, G.R., Jr.; Mathur, A.K.; Dimick, J.B. Understanding the racial disparity in the receipt of endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Arch. Surg. 2010, 145, 1105–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Sandiford, P.; Damien, M.; Dale, B. Ethnic inequalities in incidence, survival and mortality from abdominal aortic aneurysm in New Zealand. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2012, 66, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Jacomelli, J.; Lisa, S.; Anne, S.; Timothy, L.; Jonathan, E. Editor’s Choice—Inequalities in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening in England: Effects of Social Deprivation and Ethnicity. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. J. Eur. Soc. Vasc. Surg. 2017, 53, 837–843. [Google Scholar]

- Demsas, F.; Joiner, M.M.; Telma, K.; Flores, A.M.; Alyssa, M.; Teklu, S.; Ross, E.G. Disparities in peripheral artery disease care: A review and call for action. Semin. Vasc. Surg 2022, 35, 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, D.; Scalise, E.; Ielapi, N.; Bracale, U.M.; Andreucci, M.; Serra, R. Metalloproteinases as Biomarkers and Sociomarkers in Human Health and Disease. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.; Scalise, E.; Ielapi, N.; Bracale, U.M.; Faga, T.; Michael, A.; Andreucci, M.; Serra, R. Omics Science and Social Aspects in Detecting Biomarkers for Diagnosis, Risk Prediction, and Outcomes of Carotid Stenosis. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, C.C. Developing cultural competency and maximizing its effect in vascular surgery. J. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 74, 76S–85S. [Google Scholar]

- Alnahhal, K.I.; Wynn, S.; Gouthier, Z.; Sorour, A.A.; Damara, F.A.; Baffoe-Bonnie, H.; Walker, C.; Sharew, B.; Kirksey, L. Racial and ethnic representation in Peripheral Artery Disease Randomized clinical trials. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2024, 108, 355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Kudzma, E.C. Cultural competence: Cardiovascular medications. Prog. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2001, 16, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Serra, R.; Grande, R.; Butrico, L.; Fugetto, F.; de Franciscis, S. Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of chronic venous disease: A Systematic Review. Chirurgia 2016, 29, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Serra, R.; Butrico, L.; Ruggiero, M.; Rossi, A.; Buffone, G.; Fugetto, F.; De Caridi, G.; Massara, M.; Falasconi, C.; Rizzuto, A.; et al. Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of chronic leg ulcers: A Systematic Review. Acta Phlebolol. 2015, 16, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Baylis, R.A.; Smith, N.L.; Klarin, D.; Fukaya, E. Epidemiology and Genetics of Venous Thromboembolism and Chronic Venous Disease. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 1988–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiguchi, M.M.; Fallentine, J.; Oh, J.H.; Cutler, B.; Yan, Y.; Patel, H.R.; Shao, M.Y.; Agrawal, N.; Carmona, E.; Hager, E.S.; et al. Race, sex, and socioeconomic disparities affect the clinical stage of patients presenting for treatment of superficial venous disease. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2023, 11, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O’Banion, L.A.; Ozsvath, K.; Cutler, B.; Kiguchi, M. A review of the current literature of ethnic, gender, and socioeconomic disparities in venous disease. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2023, 11, 682–687. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M.; Piechota, D.; Baranska-Rybak, W. Gdansk Wound-QoL Questionnaire: Pilot Study on Health-Related Quality of Life of Patients with Chronic Ulcers with Emphasis on Professional Physician-Patient Relations. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2024, 14, e2024138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaran, R.R.; Babapour, G.; Mena-Hurtado, C.; Ochoa Chaar, C.I. Chronic Venous Insufficiency and Management. Interv. Cardiol. Clin. 2025, 14, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnelee, J.D.; Spaner, S.D. Explanatory model of chronic venous disease in the rural Midwest—A factor analysis. J. Vasc. Nurs. Plubic. Soc. Peripher. Vasc. Nurs. 2000, 18, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.; Andreucci, M.; Ielapi, N.; Bracale, U.M.; Serra, R. Social capital in chronic disease: An ethnographic study. Sci. Philos. 2023, 11, 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Schul, M.W.; Melin, M.M.; Keaton, T.J. Venous leg ulcers and prevalence of surgically correctable reflux disease in a national registry. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2023, 11, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dua, A.; Lee, C.J. Epidemiology of peripheral arterial disease and critical limb ischemia. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2016, 19, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, D.; Ielapi, N.; Caprino, F.; Giannotta, N.; Sisinni, A.; Abramo, A.; Ssempijja, L.; Andreucci, M.; Bracale, U.M.; Serra, R. Social aspects of diabetic foot: A scoping review. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.; Gallelli, G.; Scalise, E.; Ielapi, N.; Bracale, U.M.; Serra, R. Socio-Cultural Aspects of Diabetic Foot: An Ethnographic Study and an Integrated Model Proposal. Societies 2024, 14, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, H. Wound Culture. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2022, 51, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, T.S. The social skin. HAU J. Ethnogr. Theory 2012, 2, 486–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, T.E.; Borgerhoff Mulder, M.; Fogarty, L.; Schlüter, M.; Folke, C.; Haider, L.J.; Caniglia, G.; Tavoni, A.; Jansen, R.R.V.; Jørgensen, P.S.; et al. Integrating evolutionary theory and social–ecological systems research to address the sustainability challenges of the Anthropocene. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2024, 379, 20220262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trundle, C.; Phillips, T. Defining focused ethnography: Disciplinary boundary-work and the imagined divisions between ‘focused’and ‘traditional’ethnography in health research—A critical review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 332, 116108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasulo, A.; Simionati, B.; Facchin, S. Microbiome One Health model for a healthy ecosystem. Sci. One Health 2024, 3, 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tringale, M.; Stephen, G.; Boylan, A.M.; Heneghan, C. Integrating patient values and preferences in healthcare: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e067268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias-Konstantopoulos, W.L.; Collins, K.A.; Diaz, R.; Duber, H.C.; Edwards, C.D.; Hsu, A.P.; Ranney, M.L.; Riviello, R.J.; Wettstein, Z.S.; Sachs, C.J. Race, healthcare, and health disparities: A critical review and recommendations for advancing health equity. West. J. Emerh. Med. 2023, 24, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).