2. Notional Combined Approach of the EEZ and the Continental Shelf

According to UNCLOS, the EEZ is a maritime zone which can extend up to 200 nm. Hereinto, the coastal state can exercise its sovereign rights upon the continental shelf up to 200 nautical miles (nm) for research and exploitation purposes [

1], except when the Continental Shelf extends beyond 200 nm [

2]. Furthermore, it can exercise a series of exclusive rights, such as fishing and preservation of the natural resources of the EEZ waters, as well as the production of energy by water tides, currents and winds [

3]. It is noted however that, despite the advantages coastal states gained with the introduction of the EEZ, all third states, coastal and landlocked maintained the rights dictated by articles 58(1) and 87, namely the freedom of navigation, right of over-flight, laying of submerged cables, fishing and conducting scientific research. It is noteworthy that the extension of coastal state jurisdiction in the EEZ limited by 36% the open sea, accumulating in their favor 95% of world fishery [

4]. Along with the adoption of the EEZ came the problem of its delimitation, given the close linkage of the Continental Shelf and the EEZ. According to UNCLOS article 74(1), the EEZ delimitation between states with adjacent or opposite coasts, is regulated following an agreement, aiming to achieve a fair solution (equitable result). In cases where reaching an agreement is not possible, according to UNCLOS Part XV, the interested parties must resort to conciliation for the settlement of the difference (article 74(2)).

The EEZ delimitation line needs to identify with the corresponding line of the Continental Shelf (CS), to the degree that the same sovereign rights in the seabed and the submerged lands of the continental shelf are recognized in favor of the coastal state [

5]. Self-evidently, having in mind the obscurity of the clauses concerning the EEZ delimitation and given the overlap of the CS zone and the EEZ, the international application and the corresponding case-law, the clauses on the CS delimitation are applied

mutatis mutandis for the EEZ, with the following highlights: the equity provided by UNCLOS for the delimitation of overlapping CSs [

6], results in the median line being the main delimitation line (as a general customary delimitation rule). It is also necessary to point out that the principle of equity as a delimitation method has a technical character, when compared to the median line or to equidistance [

7]. The above are much more valid in the case of the EEZ; to the degree the standard of the distance from the land deadens the corresponding geological standard (natural prolongation) of the CS. At this point, it is reminded that the Geneva Convention (1958) on the Continental Shelf (CSC) defines the legal CS by emphasizing on the geological standard, an emphasis based on the Truman Declaration influence, particularly for the point referring to the geological linkage of the coastal state and the bottom of the sea [

8]. On the other hand, UNCLOS by introducing invariable standards for the EEZ and Continental Shelf delimitation (in particular the equidistance standard), limited to a minimum any controversies its estimation could cause [

9], while fortifying the equidistance rationale during delimitation [

10]. In favor of this reasoning is the fact that the distance standard is the decisive one for the CS measurements well until the 200 nm, whereas the geological standard maintains its importance only for the CS extending beyond the 200 nm margin [

11].

3. The Continental Shelf/EEZ Issue between Greece and Turkey and the Respective National Positions

The particular dispute issue has come into question since November 1973, when the Turkish government allotted fuel research zones to the Turkish State Petroleum Company in the area located among the Greek islands of Lesbos, Skiros, Limnos and (west of) Samothrace. In July 1974, it issued new permits extending this zone to the West and claimed a new narrow portion of the continental shelf located between the Greek island clusters of the Dodecanese and the Cyclades. Greece strongly protested against these two decisions. The positions of the two countries concerning the issue in question are of significant interest for the maritime delimitation law.

Greece’s positions on the Continental Shelf issue are claimed to be based on the following applicable provisions of the Law of the Sea, both Conventional and Customary:

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provides for exclusive rights ipso facto and ab initio of a coastal state on its continental shelf which has a minimum breadth of 200 nm, provided the distance between opposing coasts allows for this. Greece ratified this Treaty in 1995 (Law 2321/1995), which according to the Constitution supersedes any provision to the contrary and as the newest law takes precedence over the older.

In accordance with the UNCLOS all islands have a right to territorial waters, a contiguous zone, an Exclusive Economic Zone and a Continental Shelf [

12]. These zones are determined in accordance with the general provisions of UNCLOS, as those are implemented in mainland regions. This general rule is customary law as well and is thus binding even for non-signatory states to the Convention. Therefore, all Greek islands are entitled to a continental shelf according to the Law of the Sea.

Within this framework, a Continental Shelf delimitation issue can only be raised between the coast of Greek islands across Turkey and the Turkish coast.

With regard to the delimitation method, Greece has firmly argued that this delimitation must be based on international law, governed by the

principle of equidistance/median line [

13].

The above stance for the delimitation principle is in accordance with the Hellenic position well before the ratification of the UNCLOS by her side, since it is relied on Article 6(1), (2) of the Continental Shelf Convention (CSC) of 1958 (in which Greece has also been a party), which states that:

‘Where the same continental shelf is adjacent to the territories of two or more States whose coasts are opposite each other, the boundary of the continental shelf appertaining to such States shall be determined by agreement between them. In the absence of agreement, and unless another boundary line is justified by special circumstances, the boundary is the median line, every point of which is equidistant from the nearest points of the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea of each State is measured.

Where the same continental shelf is adjacent to the territories of two adjacent States, the boundary of the continental shelf shall be determined by agreement between them. In the absence of agreement, and unless another boundary line is justified by special circumstances, the boundary shall be determined by application of the principle of equidistance from the nearest points of the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea of each State is measured.’

The above argument is depicted in

Figure 1. According to Turkey, Greek islands do not have rights to exert jurisdiction on the continental shelf, because they are located on the

Turkish continental shelf. The

special circumstances mentioned by the CSC (which Turkey has never signed) [

15] justified, according to the Turkish opinion (See

Figure 1), the non-application of the median line method. Noting that the different positions were not being bridged, Greece submitted the controversy to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in August 1976, but Turkey refused to recognize the jurisdiction of the Court, leading the latter to declare itself incompetent. Since then, the maritime issue has remained unsolved and has been aggravated by certain arguments on territoriality [

16]. The contemporary Turkish positions on the issue in question comprise a composite agenda [

17] as follows:

The dispute according to the Turkish view concerns continental shelf areas beyond the 6 mile territorial sea in the Aegean.

Turkey claims to stand ready to engage in a dialogue with Greece aiming to achieve an equitable settlement to the best interest of both countries.

Turkey highlights the arguably ‘binding’ character of the Bern Agreement on November 11, 1976 with Greece, where the parties decided to hold negotiations with a view to reaching an agreement on the delimitation of the Continental Shelf. Under the terms of this Agreement, the two governments have, inter alia, assumed the obligation to refrain from any initiative or act concerning the Aegean Continental Shelf.

Furthermore, despite her denial of the ICJ jurisdiction in 1976, Turkey claims to positively examine the solution of the ICJ, by invoking its decision taken in 1982 in the Tunisia-Libya case, stating that ‘

delimitation is to be effected by agreement in accordance with equitable principles and taking into account all relevant circumstances’ [

18].

Figure 1.

The Turkish Continental Shelf according to the Greek view (in orange) and the Turkish view (intermittent line).

Figure 1.

The Turkish Continental Shelf according to the Greek view (in orange) and the Turkish view (intermittent line).

Source: Hellenic National Hydrographical Service.

In order to justify her claimed delimitation line of

Figure 1 as equitable, Turkey has argued that the Aegean Sea is a semi-enclosed sea with many Greek islands located all around a small area, with many of them located very near the Turkish mainland, some just 3 miles off it [

19]. It is apparent that attributing them continental shelf areas would, according to Turkey, create an inequitable result as it would deprive the Turkish mainland almost completely of a continental shelf area of its own. In addition, many other factors have been reported by Turkish officials as further justification of their official position. It was argued that the balance of interests which was established between Turkey and Greece in the Aegean Sea by the Lausanne Peace Treaty [

20] should not be disturbed by granting continental shelf areas to the said Greek islands. In fact, the term ‘balance of interests’ implies a comprehensive list of relevant circumstances such as security, navigational and commercial interests. Moreover, geomorphologic factors, as analysed further down, are considered by Turkey as another justification for its suggested delimitation line.

Over and above, according to the Turkish approach, the CS issue in the Aegean constitutes only a part of the Aegean Issue. In this way, Turkey seems to implement a diplomatic maneuver in order to present a number of extra dispute issues of a debatable legal nature, such as territorial arguments and ‘grey-zones’, along with the CS issue for which, as she claims, is ready to either negotiate with Greece or to mutually resort to an international court [

21].

As previously highlighted, the concept of the Continental Shelf is closely connected to the one of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), with the latter referring to a littoral state’s control over fishery and other similar rights [

22]. Thus, the essence of the dispute between Turkey and Greece refers to the degree that the Greek islands off the Turkish coast should be taken into account for determining the Greek and the Turkish Economic Zone.

Turkey argues that the notion of the Continental Shelf, by its very definition, implies that distances should be measured from the continental mainland, meaning that the

sea-bed of the Aegean geographically forms a

natural prolongation of the Anatolian land mass [

23]. In the same context, according to the Turkish aspect the delimitation of the EEZs in the Eastern Mediterranean should follow the principle of natural prolongation, thus not awarding any EEZ effect or CS effect to the islands of the Eastern Aegean and especially to the Dodecanesian small island of Kastelorizo, which is vital for the Greek national interests, as its influence, if recognized, can connect the Hellenic EEZ to the Cypriot EEZ (See

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Turkish view with regard to the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) delimitations in the Eastern Mediterranean [

24].

Figure 2.

The Turkish view with regard to the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) delimitations in the Eastern Mediterranean [

24].

Greece, on the other hand, claims that all islands must be taken into account on an equal basis for a full effect when it comes to maritime economic zones (See

Figure 3) [

25]. In this matter, Greece claims to have the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) on its side, as mentioned above at the introduction of her official position. Indeed, UNCLOS provides that islands (with the exception of ‘rocks’) have the right to generate all the maritime zones recognized under international law regardless of their size [

26]. However, this capacity to generate their own maritime zones should not be confused with the effect accorded to them in maritime delimitation cases judged by the international competent tribunals. In the latter case, the impact of an island will usually depend on various factors, such as the special circumstances of a case and the achievement of an equitable result through the drawing of the maritime boundary between the States concerned [

27]. In this context, the Law of the Sea Convention seems to have kept a certain degree of silence as far as the methods of delimiting maritime spaces are concerned. UNCLOS provisions on maritime delimitation issues offer predictability and flexibility up to a certain degree. The Convention provides some basic principles, such as the achievement of an equitable result and leaves to the judges to deal with the particularities of each case.

Figure 3.

The Greek view for a speculative Greek EEZ with full effect of the Greek Islands.

Figure 3.

The Greek view for a speculative Greek EEZ with full effect of the Greek Islands.

Source: Sea around Us Project.

Moreover, the fact that Turkey is not a signatory party of the UNCLOS further complicates the situation. Turkey decided to vote UNCLOS down because she failed to pass her positions during the Third Conference of the United Nations, which took place before the final formulation of UNCLOS provisions. In detail, Turkey’s stance at the Third Conference reflected its anxiety to validate its fixed geopolitical claims at the Aegean Sea. At first, Turkish diplomats attempted to pass at the conference specific ad hoc regulations for the semi-closed seas. When they failed, they focused their arguments on the Aegean Sea. According to Turkey, as already mentioned above, the Aegean Sea is a semi-closed sea [

28] with particular geographic and geologic features, a large number of islands, islets androcks very close to the Asia Minor shores in addition to the shape of the sea bottom in general [

29]. The combination of all these characteristics constituted according to the Turkish view a ‘special circumstance’ which necessitated special treatment which in turn dictated that Turkey should be excluded from all general regulations of the Law of the Sea. Any issues had to be tackled by applying

ad hoc agreements, which would take under consideration this ‘special circumstance’. For Turkey, the ideal solution based on the aforementioned circumstances was and still remains, the median line between the Greek shores (Thessaly, Central Greece and Peloponnesus) and the Turkish shores, which would mean splitting the Aegean along the 25th meridian. [

30].

4. Principles and Factors Influencing Maritime Delimitations with Regard to the Greek-Turkish Case

The silence of the Convention on the methods of delimiting maritime spaces has been progressively covered by the jurisprudence of the ICJ and more recently of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), which have established applicable principles; the Courts have thus defined the notions of equidistance/special circumstances for the delimitation of the territorial sea, and of equitable principles/relevant circumstances for the continental shelf and the EEZ, which involve—to simplify matters—tracing a provisional median line to check if the result is equitable. Considering the many special circumstances presented by the Turkish claims for the Aegean Sea, an analyst may suppose that the result in this case would not be equitable. However, several decisions regarding contentious cases highlight useful guidelines for the delimitation of the maritime spaces. In that sense, the applicable law and jurisprudence developed in recent years may thus determine the main principles in delimiting the maritime space of the Aegean Sea, while taking into consideration the fundamental concerns of the two states (equity, security).

In more detail, according to UNCLOS, in the absence of agreement to the contrary, states may not extend their territorial seas beyond the median, or equidistance line, unless there are historic or other ‘

special’ circumstances that dictate otherwise’[

31]. This ‘equidistance [

32] / special circumstances’ [

33] rule has been accepted by the ICJ as customary international law within the judgments produced throughout its recent judicial history [

34] and it seems clear that only in exceptional cases will the equidistance line not form the basis and the starting point of the boundary between overlapping territorial seas. The emergence of the distance principle gives pertinence in normal situations to the equitable method of the equidistance/median line. However, the terms

equidistance and

median line have disappeared from the text of the Articles 74 and 83 of UNCLOS (1982), which concern the delimitation basic provisions for the EEZ and CS, respectively, and state that:

‘The delimitation of the exclusive economic zone/(continental shelf) between States with opposite or adjacent coasts shall be effected by agreement on the basis of international law, as referred to in Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, in order to achieve an equitable solution’.

‘If no agreement can be reached within a reasonable period of time, the States concerned shall resort to the procedures provided for in Part XV’ (UNCLOS provisions for dispute settlement).

The aforementioned terms have remained only in Article 15 of UNCLOS, which concerns the delimitation of the Territorial Sea, as previously mentioned. Nevertheless, in spite of its diminishing role, equidistance found its way into State practice. The majority of bilateral treaties on maritime delimitation still use a line based on simplified or modified equidistance. In fact, in most ICJ cases and arbitral awards, judges found it convenient to use the equidistance line as the starting point of the delimitation process [

35]. The same approach had been adopted by the Geneva Convention for the Continental Shelf (CSC) (1958) [

36] concerning the delimitation of overlapping continental shelves, but its application in this context has been proven blurred, debatable and prone to modification during the relevant cases of the following years [

37]. To start with, in the

North Sea case, Denmark and the Netherlands argued that Article 6 CSC represented customary law and that should have been the reason for legally binding Germany, a non-state party to the Convention. The result of that claim, if applied, would have meant that Germany’s concave coastline, trapped between Denmark and Norway, would have restricted Germany to a modest area of continental shelf. Therefore, the ICJ decided that Article 6 did not reflect customary law and the delimitation of the Continental Shelf had to be conducted on the basis of equitable principles, taking account of the relevant circumstances [

38].

Thus, a period of confrontation started between the supporters of the more formulaic

equidistance/special circumstances approach and the supporters of the arguably more flexible ‘

equitable principles/relevant circumstances’ [

39] view. However, relevant circumstances have never been the sole disseminator and self-sufficient factor in delimitation. They often appeared to operate only within a framework of equitable principles or equidistance [

40]. This led, at a premature stage, to a first consideration that although Article 6 CSC and custom were different, the practical result of their application would be the same [

41]. That confrontation continued during the sessions of the Third United Conference on the Law of The Sea (1973–1982), where groups of states championed the approach they considered best suited for their interests. The last days of the Conference, as no consensus could be found, thanks to the head of the Greek government delegation [

42], an anodyne formula (short formula) was adopted, applicable to both EEZ and Continental Shelf: such delimitations are to be ‘…

effected by agreement on the basis of international law, as referred to in Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, in order to achieve an ‘equitable solution’ [

43]. This provision, which is included in Article 83(1) UNCLOS III, defines the three cornerstones of the continental shelf delimitation basic rule between states with opposite or adjacent coasts: a) delimitation by agreement, b) delimitation based on international law and finally c) delimitation which constitutes (aiming at) an equitable (fair) solution. By the formulation of the third element—delimitation which constitutes an equitable solution—it is becoming evident that the equitable solutions do not constitute a shelf-inclusive (

autotelic) principle, but only a final result which must be attained

infra (secundum) legem, as it is proclaimed by the reference of the aforementioned provisions to Article 38(1) ICJ Statute. In that sense, and, avoiding mentioning the notions equidistance, equitable principles and special or relevant circumstances, a widely accepted provision has been established. This however seems to be devoid of content, emphasizing the result and its equitableness rather than the method, the principles or the judicial methodology, when there is no agreement in place [

44].

However, in 1993 and 1999 in the

Jan Mayen and

Eritrea-Yemen cases, respectively, the ICJ ended up in a very important statement: ‘

Prima facie, a median line delimitation between opposite coasts results in general in an equitable solution’ [

45]. As for the adjacent coasts, although the above mentioned position is not quite clear concerning the use, in analogy, of the equidistance as the starting point for the delimitation, however, the relatively recent judgments of the ICJ in the

Qatar v Bahrain ([

34], p. 230) and the

Cameroun v Nigeria [

46] cases suggest that this has been thereafter the most common position. This position, concerning the equidistance as the sole starting method, was further solidified in the 2006 Arbitration Award of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) concerning the case of

Barbados v. Trinidad and Tobago, when it stated that

‘[W]hile no method of delimitation can be considered of and by itself compulsory, and no court or tribunal has so held, the need to avoid subjective determinations requires that the method used start with a measure of certainty that equidistance positively ensures, subject to its subsequent correction if justified’ [

47].

Nevertheless, despite the view that equidistance should provide the starting point, this does not necessarily mean it will be the finishing line as well. The whole field of formulations of that rule suggests that it can be modified to take into account certain other factors. That was also noted in the aforementioned PCA Award by stating that ‘

The determination of the line of delimitation thus normally follows a two-step approach. First, a provisional line of equidistance is posited as a hypothesis and a practical starting point. While a convenient starting point, equidistance alone will in many circumstances not ensure an equitable result in the light of the peculiarities of each specific case. The second step accordingly requires the examination of this provisional line in the light of relevant circumstances, which are case-specific, so as to determine whether it is necessary to adjust the provisional equidistance line in order to achieve an equitable result’ ([

47], para. 242). Among the relevant factors whose categories may vary accordingly to the specific case, close attention is usually paid to setting clear that areas appertaining to each state are not disproportionate to the ratio between the lengths of their relevant coasts adjoining the area. In addition, the existence of islands that can generate claims to maritime economic zones of sovereign rights, such as the continental shelf or the EEZ, constitutes a complicating factor and their impact upon the equidistance line can be reduced or discounted in numerous ways [

48]. In general, along the whole field of relevant circumstances, the quest for neutral criteria of a geographical character has eventually prevailed over area-specific criteria such as geomorphologic aspects or other factors of economic nature such as resource-specific criteria (i.e. distribution of fish stocks), with some exceptions ([

47], para. 228). Therefore, judicial practice has shown that non-geographical factors, such as economic factors, state-practice of the Parties or historic rights [

49], security concerns,

etc. have played so far a modest role in maritime delimitation cases [

50]. Additionally, the geological factor, which used to be considered relevant when the distance between the coasts was more than 400 nm, for distances less than this limit, it is not consider relevant lately [

51].

Consequently, the aforementioned evolution of the maritime delimitation law, has resulted in the genesis of a contemporary

formulaic concept of maritime delimitations between opposite and adjacent states, arguably creating a kind of a

step-based methodology and a clearer, as much as possible, aspect of the factors affecting delimitation—yet not a common applicable rule [

52]. The very recent cases of ICJ and ITLOS (International Tribunal for the Law Of the Sea), namely the cases

Nicaragua v. Honduras (ICJ) in 2007,

Romania v Ukraine (ICJ) in 2009,

Nicaragua v Colombia (ICJ) in 2012 and

Bangladesh v Myanmar (ITLOS) in 2012, are characteristic examples for the aforementioned evolution. Three of them will be shortly analyzed further down. These case-studies have been intentionally selected to be analyzed and then linked to the

Greek case due to their relevance and applicability to the general legal context of a potential maritime delimitation in the Aegean (applicable law, maritime zones to be delimited, impact of geography and islands, potential relevant circumstances, type of methodology to be used etc) as well as due to the relevant disputing positions and arguments of Greece and Turkey. The general aim is to link the Greek-Turkish maritime dispute and the prospect of maritime zone delimitation between Greece and Turkey to the contemporary legal regime for maritime delimitations.

5. First Case-Study: The ICJ Decision in the Black Sea (Romania v Ukraine) and the Effect of Serpent Island

An issue of great interest as far as delimitations are concerned [

53] is the one related with the Ukrainian island of Serpent, which lies in a distance of approximately 30 nm from the Ukrainian-Romanian land borders, in a way that significantly affects the median line between the two states (see

Figure 4). Because of this island, in September 2004, Romania appealed to the ICJ against Ukraine for the delimitation of their maritime border. The Court stressed that the dispute between the two countries concerned the establishment of a single maritime boundary delimiting the CSs and EEZs of the two states in the Black Sea [

54]. As for the applicable law and relevant delimitation principles, the Court stated that ‘

The entry into force of UNCLOS as between the Parties in 1999 means that the principles of maritime delimitation to be applied by the Court in this case are determined by paragraph 1 of Articles 74 and 83 thereof” [

55]. The Court also noted that on the basis of determining what constitutes the relevant coasts, the ratio for the coastal lengths between Romania and Ukraine is approximately 1:2.8 and that the coast of Serpent Island is so short that it makes no difference to the overall length of the relevant coasts of the Parties ([

55], para. 77–105).

Figure 4.

The maritime zones claimed around Serpent Island ([

55], p. 69).

Figure 4.

The maritime zones claimed around Serpent Island ([

55], p. 69).

Concerning the exact delimitation methodology to be followed by the Court, the ICJ stated that when called upon to delimit the Continental Shelf or Exclusive Economic Zones, or to draw a single delimitation line, the Court proceeds in defined stages. Thus, at first the Court would establish a provisional delimitation line, using methods that are geometrically objective and also appropriate for the geography of the area in which the delimitation is to take place. As for the delimitation between adjacent coasts, an equidistance line would be drawn unless there were compelling reasons that make it unfeasible in the particular case [

56]. As far as opposite coasts are concerned, the provisional delimitation line would consist of a median line between the two coasts. No legal consequences would follow from the use of the terms ‘median line’ and ‘equidistance line’ since the delimitation method is the same for both ([

55], para. 115–22).

Following the first stage, the course of the final line should result in an equitable solution according to Articles 74 and 83 of UNCLOS. Therefore, the Court considered at a second stage whether there were factors calling for the adjustment or shifting of the provisional equidistance line in order to achieve an equitable result as in previous cases ([

46], p. 441). The Court also made clear that when the line to be drawn covers several zones of coincident jurisdictions, ‘

the so-called equitable principles/relevant circumstances method may usefully be applied, as in these maritime zones this method is also suited to achieving an equitable result’ [

57]. Hence, this was the second part of the delimitation exercise to which the Court turned, having first established the provisional equidistance line. Finally, at a third stage, the Court checked if the line (a provisional equidistance line which may or may not be adjusted by taking into account the relevant circumstances) leads to an inequitable result because of any marked disproportion between the ratio of the respective coastal lengths and the ratio between the relevant maritime area of each State compared to the delimitation line [

58].

Regarding the effect of Serpent Island in the delimitation procedure, the issue was rather complex, given the size and the position of Serpent off the Romanian coast (Serpents’ island extents to an area of 0.17 square kilometers, it is 662 meters long and 440 meters wide, populated for the first time in 2004 by 100 inhabitants. What is very interesting is that ICJ, to which both countries appealed, did not proceed to the legal characterization of the small feature as an island or a rock. It is noted that in the first case (island) Serpent would have been entitled, according to UNCLOS, to full rights concerning the maritime zones, as provided by the Convention, whereas in the second case (rock) it would have been entitled only to a territorial zone. In its decision, the Court did not characterize it by merely referring to it as a ‘natural feature called Serpents’ Island’. However, it attributed to it the right of a 12 nm territorial zone without awarding any effect to the shift of the single maritime boundary line of EEZ and CS (see

Figure 5). The philosophy behind this is simple: should it be explicitly characterized as an island, it would potentially translate this status into economic zones. On the other hand, it could not be characterized as a rock, given that a permanent human population resides on it.

In detail, during the selection phase of base points the Court made clear that Serpent Island’s calls for specific attention to determine the provisional equidistance line. In connection with the selection of base points, the Court observed that there have been instances when coastal islands have been considered to be parts of a State’s coast and in particular when a coast is made up of the fringe islands’ cluster [

59]. Nevertheless, the important statement of the Court was that ‘

Serpents’ Island, lying alone and some 20 nautical miles away from the mainland, is not one of a cluster of fringe islands constituting ‘the coast’ of Ukraine. To count Serpent Island as a relevant part of the coast would amount to grafting an extraneous element onto Ukraine’s coastline; the consequence would be a judicial refashioning of geography, which neither the law nor practice of maritime delimitation authorizes’ [

60]. The Court thus decided that Serpent cannot be taken to form part of Ukraine’s coastal configuration, considering it inappropriate to select any base points on Serpent Island for the construction of a provisional equidistance line between the coasts of Romania and Ukraine. ([

55], para. 123–49). Moreover, checking for the relative circumstances that may call for the shifting of the provisional equidistance line in order to achieve an ‘equitable solution’ as required by Articles 74, paragraph 1, and 83, paragraph 1, of UNCLOS, neither the disproportion between the lengths of relevant coasts nor the enclosed nature of the Black Sea or the presence of any cutting off effect justified any such of a shifting. In addition, neither the conduct of the Parties (oil and gas concessions, fishing activities and naval patrols) nor their security considerations justified for an adjustment of the provisional equidistance line ([

55], para. 155–204). Finally, ascertaining whether the presence of Serpent Island in the delimitation area constitutes a relevant circumstance calling for an adjustment of the provisional equidistance line or not, the Court decided that it does not, due to the fact that Serpent could not serve as a base point for the construction of that line between the coasts of the Parties, which was drawn in the first stage of this delimitation process, since it did not constitute part of the general configuration of the coast. Hence, it concluded that ‘

in the context of the present case, Serpents’ Island should have no effect on the delimitation in this case, other than that stemming from the role of the 12-nautical-mile arc of its territorial sea’ ([

55], para. 179–88).

Figure 5.

The ICJ decision for the Serpent Island case ([

55], p. 133).

Figure 5.

The ICJ decision for the Serpent Island case ([

55], p. 133).

6. Second Case-Study: The ITLOS Decision in the Bay of Bengal (Bangladesh v Myanmar) and the Methodology Followed by the Tribunal for a Single Maritime Boundary

In March 2012, the ITLOS delivered a judgment in its first maritime delimitation case:

Dispute concerning delimitation of the maritime boundary between Bangladesh and Myanmar in the Bay of Bengal (Bangladesh/Myanmar). That case is part of a couple of maritime delimitation cases involving Bangladesh and its neighboring countries [

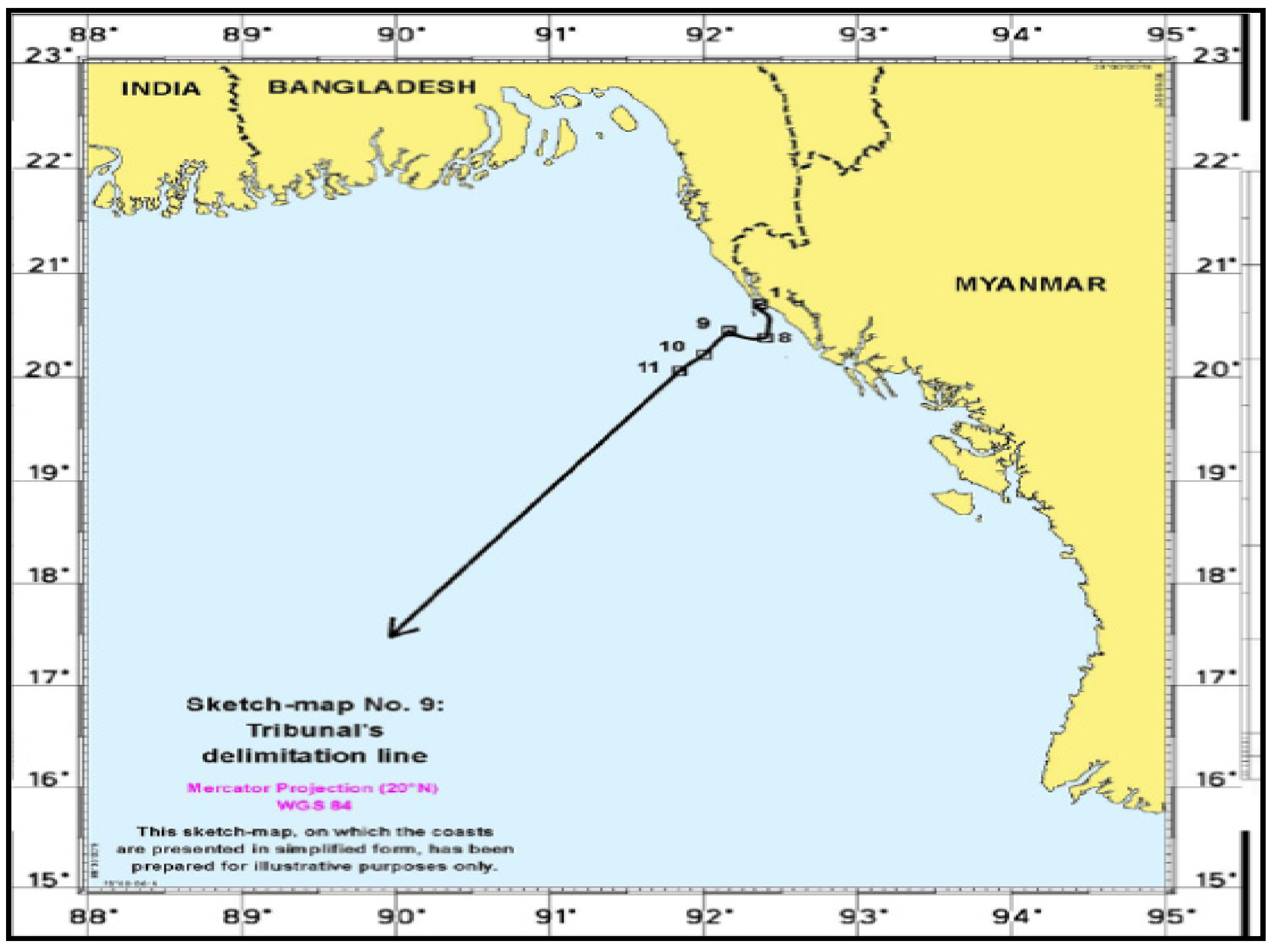

61]. It may be noted that ITLOS set out a single maritime boundary delimiting the territorial seas, exclusive economic zones and continental shelves of the abovementioned States. Thus, both parties had something to gain from the decision. A short view at the map of the region (See

Figure 6) will bring immediately in the reader’s mind the geographical context of the

North Sea continental shelf case, decided by the ICJ in 1969. In fact, there are at least three similarities between the two cases. The first is the concavity of the coast of one of the litigant parties. In the

North Sea case it was Germany, in this case it is Bangladesh. The second is the role of geology and the relevance of the

natural prolongation concept. The third is the necessity for the judge assigned to the dispute to exercise

law-making functions, something absent from any judicial precedent [

62]. Moreover, one of the most important denotations made by the Tribunal was the prevalence of one maritime zone on another. The Tribunal made clear that the territorial sea will prevail upon the EEZ: ‘…

the Tribunal recognizes that Bangladesh has the right to a 12 nautical miles territorial sea around St. Martin’s Island in the area where such territorial sea no longer overlaps with Myanmar’s territorial sea. A conclusion to the contrary would result in giving more weight to the sovereign rights and jurisdiction of Myanmar in its exclusive economic zone and continental shelf than to the sovereignty of Bangladesh over its territorial sea…’ [

63] and that a state may exercise rights in an overlapping area that does not pose impediments to the other state rights exercised [

64].

Figure 6.

Geography of the area between Bangladesh and Myanmar in the Bay of Bengal ([

63], p.20).

Figure 6.

Geography of the area between Bangladesh and Myanmar in the Bay of Bengal ([

63], p.20).

As far as it concerns the sequence of delimitation, the above is in full accordance to the methodology followed by ICJ in the Black Sea, plus the delimitation of CSs beyond 200 nm. Accordingly, the Tribunal first divided the boundary line to be drawn into three parts [

65]: the first delimited the territorial seas of the parties; the second designated their exclusive economic zones and their continental shelves up to 200 nm, while the third mapped out the continental shelves beyond 200 nm. The reasons for doing this clearly differ. In the case of the territorial sea, the applicable rule is different from the one applied to the delimitation of the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf [

66]. Thereupon, the stages of the ITLOS judicial procedure were the following ones:

At first, the ITLOS delimited the territorial sea between the parties. This delimitation took place according to Article 15 UNCLOS, which requires that an

equidistance line be adopted, unless there are

special circumstances or

historic title justifying another delimitation line, thus causing deviation from the common rule [

67]. This first

provisional equidistance line became the final boundary for this area, since according to ITLOS’ view there were no special circumstances to justify divergence from it (see

Figure 7). St Martin’s Island, part of Bangladesh, was afforded full effect and was suitably used for plotting the equidistance line ([

63], para. 169). This upshot is in analogy with previous decisions of the ICJ more specifically and with the established State practice, which in its turn generates customary law. Thus, both customary and conventional international law favors equidistance in the delimitation of the territorial sea and grants full effect when it comes to islands’ territorial sea rights.

Figure 7.

The Tribunal’s territorial sea delimitation ([

63], p.57).

Figure 7.

The Tribunal’s territorial sea delimitation ([

63], p.57).

Secondly, concerning the delimitation of the single boundary for the EEZ and the Continental Shelf within 200 nm, the applicable law according to the Tribunal denotation, is to be found in the UNCLOS [

68], the customary international law ([

63], para. 183) and the respective case-law (judicial decisions) ([

63], para.184). Therefore, the ITLOS adopted the three-step method recently used by the ICJ in the Black Sea [

69], according to which it first drew an equidistance line, it then checked its equitableness in the light of relevant circumstances and finally assessed the result on the basis of

proportionality. The provisional line actually is a

modified equidistance line, (see

Figure 8) since ITLOS selected and treated accordingly certain base points to be used ([

63], para. 241). Nevertheless, an issue of great importance is that the Tribunal decided (in analogy with ICJ and the Serpent Island) not to use St Martin’s Island as a base point, because of the alleged

cut-off effect on the projection of Myanmar’s coast ([

63], para. 265). Then, turning to relevant circumstances, the Tribunal accepted Bangladesh’s contention that its concave coast is relevant [

70].

Figure 8.

The ITLOS’ provisional equidistance line for the delimitation of EEZ/Continental Shelf ([

63], p. 86).

Figure 8.

The ITLOS’ provisional equidistance line for the delimitation of EEZ/Continental Shelf ([

63], p. 86).

Therefore, it decided to revise accordingly the provisional line, by drawing a

geodetic line starting at an azimuth of 215 from a point on the provisional line close to the coast ([

63], para. 331–34). While this was in principle considered as a relevant circumstance for the purpose of the international law on maritime delimitations, ITLOS did not attribute any effect with regard to EEZ or Continental Shelf to St Martin’s Island in the end, asserting

practical reasons, namely the alleged cut-off effect ([

63], para. 318–19).

Geology of the seabed, on the other hand, was considered to be irrelevant both in law and practice [

71]. Favoring this reasoning, the ICJ in the

Continental Shelf (Libyan Arab Jamahiriya/Malta) Judgment stated that the

distance standard is the decisive one for the continental shelf measurements well until the 200 nm limit, whereas the

geological standard maintains its importance only for the continental-self extending beyond the 200 nm margin [

51]. This is because the delimitation of a single maritime boundary is to ‘

be determined on the basis of geography and not

geology or

geomorphology’ ([

63], para. 322). The resulting final line is depicted in

Figure 9.

The next assignment of the Tribunal concerned the delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nm (extended continental shelf). It was the first time that an international court or tribunal had to address the law and practice for delimiting such an area. Therefore, ITLOS set the principles and rules not only for this case, but also for future use. Firstly, it made clear that a court or tribunal having jurisdiction on the basis of UNCLOS XV (1982) can delimit the continental shelf beyond 200 nm even in the absence of recommendations by the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) and that there are no reasons to abstain from exercising its jurisdiction ([

63], para. 363–94). Secondly, the ITLOS defined that natural prolongation for the purposes of Article 76 UNCLOS [

72] is very much the same as the continental margin, as defined in the same article. Thus, only geomorphology (which describes the seabed) and not geology (which describes the composition of the subsoil) is relevant in determining whether there is an overlapping of entitlements and thus there is the need to draw a boundary. This is essentially a confutation of natural prolongation as a geological concept. In that way and with respect to relevant circumstances, the Tribunal did not accept Bangladesh’s argument on the

most natural prolongation. The Tribunal concluded as well that a

significant geological discontinuity is not relevant for determining entitlement ([

63], para. 434–38) and that the geographic origin of the sedimentary rocks is similarly irrelevant ([

63], para. 447). On the contrary, concavity of the coast was considered to be a relevant circumstance ([

63], para. 460–61). A worth mentioning part of the ITLOS judgment is that entitlement to the continental shelf does not rely on any procedural requirements [

73]. Thirdly, the method to be applied for the delimitation of this area was the same as for the single boundary (equidistance/special circumstances) ([

63], para.455). This part of the delimitation is suitably completed by a reference to the notorious

grey area issue. Regarding this, the ITLOS authoritatively affirmed that when, by reason of the employment of a delimitation method other than the equidistance line, the extended continental shelf of a state, as delimited by a boundary line, is beneath the EEZ of the other, the latter still exercises all its rights over the water column. In such a situation, each state, in exercising its rights and obligations, is under an obligation to have due regard to the rights and obligations of the other ([

63], para. 474–76) (see

Figure 10).

Figure 9.

The ITLOS’ final delimitation line for the EEZ/Continental Shelf ([

63], p. 146).

Figure 9.

The ITLOS’ final delimitation line for the EEZ/Continental Shelf ([

63], p. 146).

Figure 10.

The EEZ/Continental Shelf ‘

grey area’ ([

63], p. 138).

Figure 10.

The EEZ/Continental Shelf ‘

grey area’ ([

63], p. 138).

Finally, in the concluding

proportionality test, appropriately stated in the Court’s decision as

‘disproportionality test’, the Tribunal measured the relevant coasts and the relevant area to be delimited and remarked that mathematical precision is not needed in delivering the concrete task. Consequently, it supplemented the delimitation case stating that a ratio of 1:1.42, which is the length of the coasts of each party, to 1:1.54, which is the attributed area to each one, is not essentially disproportionate ([

63], para. 477).

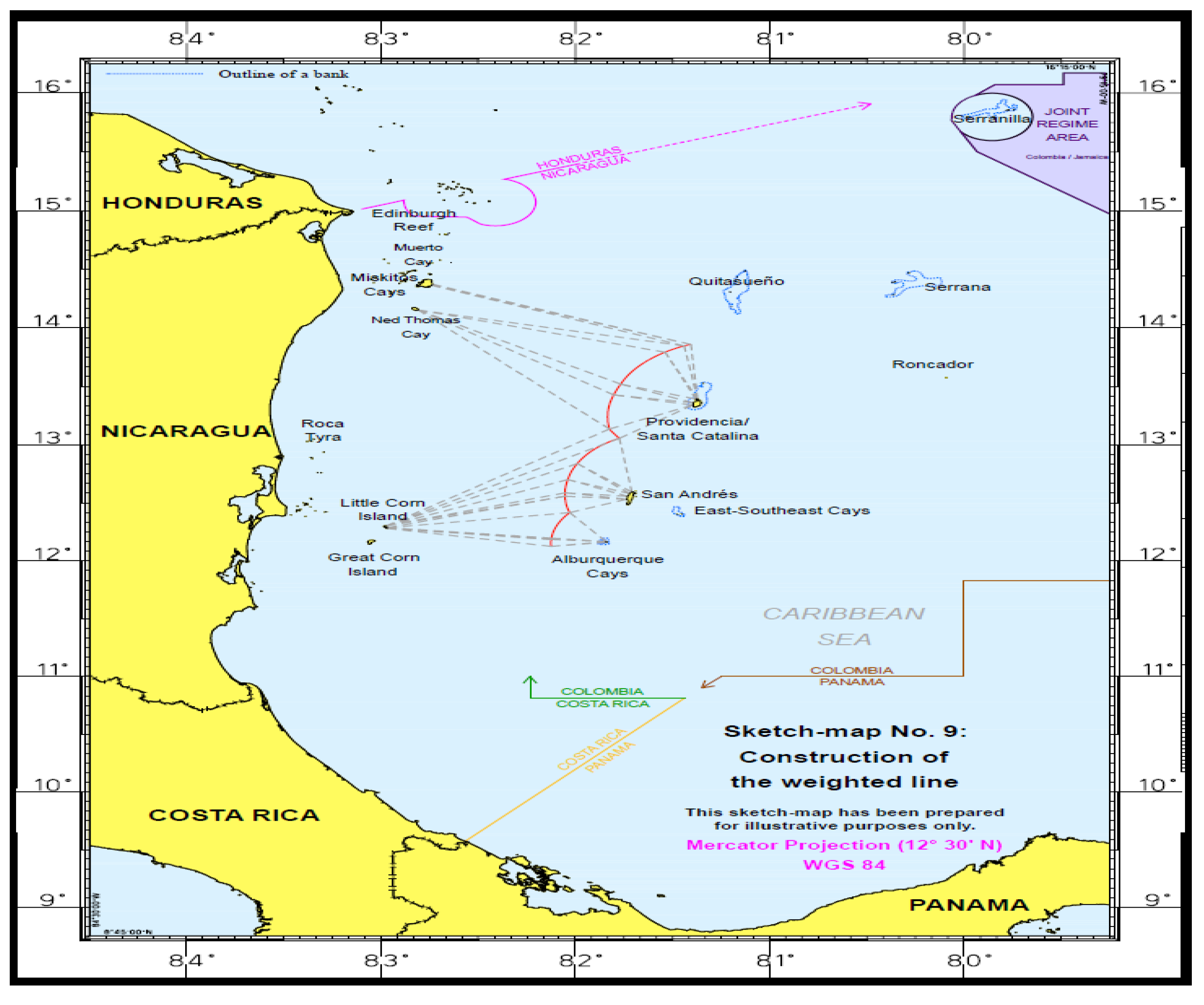

7. Third Case-Study: The ICJ Decision in the Nicaragua v Colombia Case and the ‘Bizarre’ Final Boundary Line

Following the same concept as in the Black Sea decision, the ICJ reached in November 2012 a decision for the

Nicaragua v Colombia maritime delimitation case. The decision concerned the simultaneous delimitation of the EEZ and the Continental Shelf between the two states. Nicaragua had appealed to the ICJ against Colombia with the demand to acquire the sovereignty rights over some islands allegedly claimed to be under Colombia’s sovereignty, and consequently to proportionately expand its maritime boundaries. The Court finally decided that Colombia would be the state to have total sovereignty rights over the islands in question (islands Alburquerque, East-Southeast Cays, Roncador, Serrana, Quitasueño, Serranilla and Bajo Nuevo), while at the same time it refused to give to the majority of them any EEZ or Continental Shelf rights, thus enclaving them in the EEZ of Nicaragua. However, those islands were eligible to claim territorial sea up to 12 nm [

74].

Figure 11 reflects the relevant maritime area as identified by the Court. The lengths of the relevant coasts were 531 km (Nicaragua) and 65 km (Colombia), a ratio of approximately 1:8:2 in favor of Nicaragua [

75].

Figure 11.

Relevant maritime area in the

Nicaragua v Colombia case as identified by the Court [

76].

Figure 11.

Relevant maritime area in the

Nicaragua v Colombia case as identified by the Court [

76].

In detail, the evidence regarding Colombia’s administration acts with respect to the islands and the absence of any evidence for acts

à titre de souverain on the part of Nicaragua provided very strong support for Colombia’s sovereignty claim over the maritime features in the dispute. The Court also noted that, while not having evidence of sovereignty, Nicaragua’s conduct with regard to the disputed maritime features, the practice of third states and maps afford some support to Colombia’s claim. Thus, the Court concluded that Colombia, and not Nicaragua, has sovereignty over the islands of Albuquerque, Bajo Nuevo, East-Southeast Cays, Quitasueño, Roncador, Serrana and Serranilla [

76].

With regard to the next task of the Court, ICJ noted that there was an overlap between Nicaragua’s entitlement to a continental shelf and exclusive economic zone extending up to 200 nm from its mainland coast and adjacent islands and Colombia’s entitlement to a continental shelf and exclusive economic zone due to the islands over which the Court has held that Colombia has sovereignty. Thus, the Court was called upon to effect delimitation between the overlapping maritime entitlements of Colombia and Nicaragua within 200 nautical miles of the Nicaraguan coast ([

75], p. 4). The law applicable to that delimitation was customary international law since Colombia was not a UNCLOS party. The Court considered that the principles of maritime delimitation enshrined in Articles 74 and 83 of UNCLOS and the legal regime of islands set out in UNCLOS Article 121 reflect customary international law ([

75], p. 4).

With respect to the entitlements generated by the maritime features, the Court found that Colombia was entitled to a territorial sea of 12 nautical miles around QS 32 at Quitasueño. At the same time, it observed that it had not been suggested by either Party that QS 32 was anything other than a rock thus incapable of sustaining human habitation or economic life of its own under Article 121, paragraph 3, of UNCLOS and therefore this feature generated no entitlement to a continental shelf or exclusive economic zone ([

75], p. 7). Accordingly, as for the selection of base points for the determination of the provisional delimitation line the, the Court held that Quitasueño Island was unsuitable to be used for the construction of the provisional median line. As stated:

‘The part of Quitasueño which is undoubtedly above water at high tide is a minuscule feature, barely 1 sq m in dimension. When placing base points on very small maritime features would distort the relevant geography, it is appropriate to disregard them in the construction of a provisional median line’ ([

75], p. 7). Moreover, it decided not to place a base point on Serrana or Low Cay Islands. The base points on the Colombian side were therefore located on Santa Catalina, Providencia and San Andrés islands and on Albuquerque Cays ([

75], p. 7).

Although the Court touched upon the issues raised by the Article 121(3) UNCLOS regarding the distinction between rocks which are entitled only to a territorial sea and all other islands, which are entitled to an EEZ and a continental shelf, the decision does not fully engage with the distinction as one might have hoped. For example, in the case of the Serrana Island feature, the Court held that it was unnecessary to determine whether it was an Article 121(3) rock, since it lay within 200 nm of Providencia Island (a non-rock island) and its entitlements, if any, beyond a territorial sea would entirely overlap with those of Providencia [

77]. While the continental shelves of Providencia and Serrana islands would overlap if both were given a 200nm entitlement, the Court did not award Providencia a full 200 nm entitlement. It is suggested that this should have brought the status of the feature of Serrana back into play; instead the Court concluded that ‘…

its small size, remoteness and other characteristics mean that, in any event, the achievement of an equitable result requires that the boundary line follow the outer limit of the territorial sea around the island’([

77], para. 238). Thus, although the Court cites its decision in

Qatar v Bahrain case that islands, regardless of their size, generate the same maritime rights as other land territory [

34], it relies on the size and

other characteristics of Serrana to deny it any entitlements beyond a territorial sea, whilst at the same time it avoids the question of whether it is in fact a rock, and thus is only entitled to a territorial sea.

As for the delimitation of the Outer Continental Shelf, Nicaragua had requested in its final submission that the Court delimited the continental shelf including areas beyond 200 nm off the Nicaraguan coast, meaning an extended or outer continental shelf. As Colombia is not a UNCLOS party, the case had to be decided in accordance with customary international law. The parties disagreed on the customary law nature of rules regarding the continental shelf beyond 200 nm [

78]. The Court concluded that the claim contained in the final submission by Nicaragua was admissible ([

77], p. 3). However, the court held a neutral half-stance. According to its statement, as the Court was not presented from the Nicaraguan side with any further official information, except a preliminary one to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), it found that, in the proceedings, Nicaragua had not established that it had a continental margin extending far enough to overlap with Colombia’s 200-nm entitlement to continental shelf, measured from Colombia’s mainland coast. The Court thus stated it was not in a position to delimit the boundary between an extended continental shelf for Nicaragua and a Continental Shelf for Colombia [

79]. Nevertheless, while the Court avoided handling the issue of Nicaragua’s extended continental shelf, if the recommendations of the CLCS eventually indicate that Nicaragua has a continental shelf extending beyond 200 nm, the status of the line indicated by the Court as the eastern limit of the relevant area will have to be reevaluated.

Regarding the methodology for the maritime zone delimitation followed by the Court, the recent jurisprudence both of the ICJ (

Romania v Ukraine case) and of the ITLOS (

Bangladesh v Myanmar case) suggest that the overlapping continental shelf and EEZ entitlements are to be delimited using a single maritime boundary through the previously mentioned three-step approach, More analytically, at a first stage, the Court selected the base points and constructed a provisional median line between the Nicaraguan coast and the western coasts of the relevant Colombian islands, which are opposite the Nicaraguan coast ([

77], pp. 184–204) (see

Figure 12).

Secondly, the Court examined the relevant circumstances which may require an adjustment or shifting of the provisional median line to produce an equitable result. It noted that the substantial disparity between the relevant Colombian coast and the Nicaraguan one (1:8), as well as the need to avoid any cut-off effect caused by the delimitation line vis-à-vis the Parties’ coastal projections, were such circumstances. The Court further noted that, while legitimate security concerns will be borne in mind in determining whether the provisional median line should be adjusted or shifted, the conduct of the parties, issues of access to natural resources and delimitations already effected in the area, were not relevant circumstances in the present case. Having thus identified the relevant circumstances applicable in the specific case, the Court proceeded by way of shifting the provisional median line. In this context, the Court drew a distinction between that part of the relevant area which lies between the Nicaraguan mainland and the western coasts of Alburquerque Cays, San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina (opposite coasts) and the part which lies to the east of those islands (more complex relationship). In the first western part of the area, the relevant circumstances called for the provisional median line to be shifted eastwards. For this purpose, the base points located on the Nicaraguan and Colombian islands respectively should have had different weights, namely, one to one for the Colombian base points and three to one for the Nicaraguan base points. The weighted line, constructed on this basis, had a curved shape with a large number of turning points ([

77], pp. 205–38) (see

Figure 13).

Figure 12.

The provisional median line in the

Nicaragua v Colombia case ([

77], p. 76).

Figure 12.

The provisional median line in the

Nicaragua v Colombia case ([

77], p. 76).

Figure 13.

The weighed line in the

Nicaragua v Colombia case ([

77], p. 86).

Figure 13.

The weighed line in the

Nicaragua v Colombia case ([

77], p. 86).

The Court considered, however, that to extend that line further north and south would not lead to an equitable result because it would still leave Colombia with a significantly larger share of the relevant area compared to Nicaragua, notwithstanding the fact that Nicaragua’s relevant coast is more than eight times the length of Colombia’s one. This would cut Nicaragua off from areas east of the principal Colombian islands into which the Nicaraguan coast projects. The Court considered that an equitable result can be achieved by continuing the boundary line along the parallels of latitude to 200 nm from the Nicaraguan coast. In the north, this line follows the parallel passing through the northernmost point of the 12-nm territorial sea of Roncador. In the south, the maritime boundary first follows the 12 nm territorial sea of Albuquerque Cays and East-Southeast Cays and then, from the most eastward point of the latter’s territorial sea, the parallel of latitude. As Quitasueño and Serrana would consequently be left on the Nicaraguan side of the boundary line, the line of the maritime boundary around each of these features follows the 12 nm territorial sea around them ([

77], pp. 229–38) (see

Figure 14 and

Figure 15).

Figure 14.

The simplified weighed line in the

Nicaragua v Colombia case ([

77], p. 87).

Figure 14.

The simplified weighed line in the

Nicaragua v Colombia case ([

77], p. 87).

The Court, therefore, reduced the number of turning points and connected them by geodetic lines ([

77], pp. 229–38) (see

Figure 15).

Figure 15.

The final result of the maritime boundary in the

Nicaragua v Colombia case ([

77], p. 89).

Figure 15.

The final result of the maritime boundary in the

Nicaragua v Colombia case ([

77], p. 89).

At the end, the Court noted that the boundary line divided the relevant area between the parties in a ratio of approximately 1:3.44 in Nicaragua’s favor, while the ratio of relevant coasts is approximately 1:8.2. The question therefore is whether, in the circumstances of the present case, this disproportion was great enough to render the result inequitable. The Court concluded that, taking account of all the circumstances of the case in question, the result achieved by the maritime delimitation does not entail such a disproportionality so as to create an inequitable result ([

77], pp. 239–47).

The final result is that in shifting the median line, the Court effectively introduced two parallel lines, enclosing the larger Colombian islands and enclaving Quitasueño and Serrana islands, with the areas falling outside these lines awarded to Nicaragua. Consequently, Colombia was granted significantly less maritime entitlements than the ones it had claimed [

80].

8. The Linkages of the Recent ICJ and ITLOS Decisions to the Greek-Turkish Dispute for the EEZ/Continental Shelf

The aforementioned ICJ and ITLOS decisions have drawn the attention of the Hellenic law and foreign affairs community due to the Greek-Turkish dispute concerning the impact of the Greek Islands to the Continental Shelf/EEZ of the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean Sea. Nevertheless, the parallelism between the three cases and the Greco-Turkish case sets off some common points as well as significant particularities and differences in case the dispute is ever judged before an international jurisdictional institution. Firstly, concerning the applicable law, this would be found in international custom, given that Turkey is not a UNCLOS signatory party. However, due to the fact that the vast majority of the UNCLOS provisions have assimilated custom and state practice, thus constituting customary law, the applicable law may also be found in this global Convention, favoring up to a certain degree a signatory party that complies with its provisions. Secondly, concerning the applicable principles to be taken into account, the recent judicial practice favors the application of equitable principles/relevant circumstances rather than the principle of equidistance/special circumstances for the delimitation of CS and EEZ following the general provisions of UNCLOS Articles 74 and 83. In that sense, the Greek claim for the application of equidistance principle seems to be more difficulty accepted compared to the respective Turkish claim. However, it is almost certain that the delimitation process will start with the equidistance/median line rule for the construction of the provisional line for all maritime zones between Greece and Turkey.

In addition, in relation to the islands’ impact issue, the majority of the islands of the abovementioned cases had the characteristics of very small maritime features or rocks. For example, Serpent, or some of the

rock-shape islands of Colombia are tiny (Serpent for example is 10 times smaller than the most southeastern Greek island, Kastelorizo, which may play an important role regarding the extent of Greek and Turkish EEZ and CS in South-Eastern Med.). Thus, Kasterolizo itself, being a relatively small island, compared to other islands in the Aegean, overtops Serpent and some of the Colombian islands by much [

81]. Similarly, it hardly justifies the same criteria with Serrana Island (small size and remoteness) not to be selected as a base point for the construction of a provisional equidistance line. Nevertheless, it may be argued by the Turkish side that Kastelorizo causes a cut-off effect to the opposite coast and therefore there is the possibility that it is not selected as a base point and potentially awarded with a reduced effect concerning the economic zones since it could seem to be situated relatively far from the main volume of Dodecanesian Islands—but in a significantly shorter distance than the ‘wronged’ islands of the aforementioned cases’. However, such a reduced effect will probably be partially covered by the effect produced by the arc of Crete and Dodecanese. All the same, the majority of the abovementioned cases’ islands was sparsely populated (Serpent for example is inhabited by 100 residents), whereas the grand majority of the Greek islands is much larger in terms of size and population (even the ‘small’ Kastelorizo has the quadruple number of residents since antiquity). Furthermore, the position of the Greek Islands in the Aegean Sea calls forth a stronger effect due to their projection on the opposite Turkish coast because of the archipelagic form of the Aegean. Furthermore, this stands true because although the Aegean is not an archipelago according to the definition of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), so Greece is not considered to be an archipelagic state; however, the archipelagic shape of the Aegean Sea is a reality which needs to be taken under consideration in favor of the coastal state which has this archipelago. This is much more the case since this archipelagic form ensures the political and economic unity of the insular space with the mainland which lay in a very close distance leaving small spaces of open seas [

82]. This is particularly evident in comparison to the

Nicaragua v Colombia case where the small islands of Colombia are completely cut-off the mainland in a comparatively long distance from it. Consequently, there is no room for great similarities in that sense.

It could generally be said that the ICJ recognition of a 12 nm territorial zone for the tiny Serpent Island combined to its small population, offers some gratification to the Greek arguments. This gratification however is not great for Greece, given that there was a permanently situated population on the island, it was thus proven that it can sustain human population and therefore is an island. Consequently, it should arguably be selected as a base point for the construction of the provisional equidistance line as well as be entitled to economic zones in a certain degree.

Besides, the fact that the ICJ did not link its decision to refuse the establishment of an EEZ for Serpent on the reasoning that the Black Sea is a semi-enclosed sea, is of great interest for Greece, given that if that was the case, it could create in a way res judicata in favor of the Turkish position in the Aegean Sea. A position which does not recognize EEZ rights or continental shelf zones for the Greek Islands due to the alleged semi-enclosed character of the Aegean Sea, despite the fact that the Aegean is not a semi-enclosed sea per se but belongs to the Mediterranean, which in its turn is a semi-enclosed one. Nevertheless, the Court did not deviate from the general provisions of UNCLOS, which handles semi-enclosed seas with no differentiation when it comes to the economic zones’ rights of the islands. However, the claim by the Turkish side for consideration of its alleged security and legitimate concerns in the Aegean might reflect a relevant circumstance in the opinion of a Court. Nevertheless, the degree of the respective effect in the construction of a boundary line will probably be low as it derives from the treatment of this particular factor in the majority of the relevant recent judicial cases.

Moreover, the very concise treatment of relevant circumstances issue in the Bangladesh v Myanmar case by ITLOS is surprising. Relevance of concavity is discussed in the light of previous case law for the purpose of the respective effect made by the coastal projection, although the conclusion of the Tribunal on this point is very terse. On the other hand, geology and the argument of natural prolongation are very hurriedly dismissed. This is justified since the majority of the recent judicial cases’ geography overtops geology or other geomorphologic factors in terms of their determination as relevant circumstances, at least up to the limit of the 200 nm from the baselines. In that sense, the argument of natural prolongation, raised by the Turkish side may not be consider to be a relevant circumstance.

Finally, both the ITLOS

Bangladesh v Myanmar case and the ICJ

Nicaragua v Colombia cases have generally highlighted that concerning the single maritime boundary for the delimitation of the EEZ and the Continental Shelf up to 200 nm, the line finally drawn does appear to be somewhere in between the claims of the two parties and does not seem particularly inequitable for either. However, that practice might not be the rule in a potential delimitation of a Greek-Turkish EEZ since the Aegean Islands together with the mainland constitute a length of coasts that by far outflanks the length of the opposite Turkish coast. However, if there was a likelihood to be applied in proportion, the 12 nm territorial sea—instead of 6 nm which is currently the boundary—that the Greek Islands should be legitimately be entitled to, would create a large ‘Greek Aegean territorial sea’ (see

Figure 16) and EEZ/CS, respectively.

Figure 16.

Greek and Turkish territorial sea width in the Aegean in the context of 6 and 12 nm Greek territorial sea limit, respectively [

83].

Figure 16.

Greek and Turkish territorial sea width in the Aegean in the context of 6 and 12 nm Greek territorial sea limit, respectively [

83].

Notes: 6 nm Greek Territorial Sea Width (present);12 nm Greek Territorial Sea Width (UNCLOS).

Nevertheless, these recent cases pointed out that although the delimitation of the territorial sea seems to follow the provisions of Article 15 UNCLOS in almost every recent judicial case, at the same time every delimitation case concerning the Continental Shelf or the EEZ (or the total package of EEZ-CS) is unique, rendering the formulation of a general applicable rule impossible, thus leaving no room for a confident prediction regarding the Greek-Turkish case.

9. The Prospect of a Greek Exclusive Economic Zone and its Delimitation Aspects

Taking into account the previously noted international jurisprudence details for maritime delimitations, it is reasonable to think that Greece arguably has a strong legal position concerning the delimitation of its Continental Shelf and that the delimitation of an EEZ and the Continental Shelf in a single maritime boundary basis is a viable method of resolving its dispute with Turkey in the Aegean Sea. A Greek EEZ in the Aegean Sea is favored by the fact that Greece has a total of 3,100 islands, of which 2,463 are in the Aegean. By comparison, Turkey only has three islands in the Aegean. A reason that most coastal states have unilaterally adopted the 200 nm EEZ is to counteract overexploitation of their coastal fish stocks. A large part of the Greek fishing fleet has traditionally operated in waters outside the Greek coasts and especially in the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. Now that many states are establishing EEZs of their own, Greek fishermen have lost access to traditional fishing grounds. A Greek EEZ, therefore, would be beneficial to the fishing sector of the country as well [

84]. Moreover, up to date, there are 127 nations that already possess either an EEZ or an Exclusive Fishing Zone (EFZ) of 200 nm, while UNCLOS provides for an EEZ regime in which there are no restrictions prohibiting islands from having such a zone [

85].

Over and above, at the end of 1986, Turkey unilaterally proclaimed a 200 nm EEZ in the Black Sea. This move was in accordance with the provisions of the UNCLOS, which Turkey has not signed so far. Concurrently, Turkey reached an agreement on the delimitation of the EEZ with the Soviet Union. Ankara agreed that the CS boundary, which was established by the Soviet-Turkish Delimitation Agreement of 1978, was also valid for delimitation of their EEZs [

86]. This agreement used the equidistance method; there were no provisions of special circumstances or any reference to enclosed or semi-enclosed seas. Thus Turkey, by accepting through this practice the concept of the EEZ, as developed through UNCLOS, has complicated its position vis-a-vis Greece, because the Black Sea is a semi-enclosed sea with many similarities to the Aegean. [

87]. Turkey reached similar agreements with Bulgaria and Romania concerning the delimitation of their respective EEZs in the Black Sea (see

Figure 17). In the discussions between Turkey and Bulgaria, the Turkish side argued that no special circumstances apply to the Black Sea [

88]. Turkey appears to implement a double standard position regarding the treatment of two seas (Black and Aegean), which is probably difficult to defend; it is rather an attempt to make a clear differentiation between delimitation of its maritime boundaries in the Black Sea and the Aegean Sea according to national interest commands and the alleged ‘security concerns’ [

89]. The same stands for the territorial sea limit of Turkey, which extends up to 12 nm in the Black Sea region as well as in South-Eastern Mediterranean, while it is 6 nm in the Aegean in order to ground the threat of war (

casus-belli) against Greece, should the latter state extent its territorial sea limit from 6–12 nm [

90]. However, it is hard for a state to construct a convincing argument by selectively choosing parts of the UNCLOS according to its liking, combined with implied acts of aggression against a state which merely wants to apply the provisions of the Convention regarding its legitimate right to territorial sea.

Figure 17.

The EEZ delimitations in the Black Sea among Turkey and the neighboring countries based on the equidistance method.

Figure 17.

The EEZ delimitations in the Black Sea among Turkey and the neighboring countries based on the equidistance method.

Source: Sea Around Us Project.

However, if the issue of the expansion of Greek territorial waters is raised before an International Court of Law, the Court would probably follow the pattern of arbitration applied between France and the United Kingdom, in which it awarded a zone of 12 nm around the Channel Islands even though the UK had maintained a 3 nm territorial sea since 1878 [

91]. Although one cannot conclude that a 12 nm zone around islands is the rule of thumb for further delimitations, it is clear that the Continental Shelf or EEZ of an island cannot be less than the internationally recognized

maximum territorial sea [

92]. If a zone of 12 miles is awarded to the eastern Greek Islands, Turkey’s Continental Shelf would also be limited. Turkey would approximately receive only 2–4 percent of the total area of the Aegean continental shelf under the 1982 Convention. However, since the ICJ has lately given emphasis to equity principles, the maximum area that Turkey could receive would arguably be 10–15 percent of the total Continental Shelf area of the Aegean, assuming that the Greek islands are entitled at least to a 12 nm zone, which should be the case.

10. Conclusions

As it derives from the analysis, a single maritime boundary is a very reasonable solution for most states, thus for Greece and Turkey as well. In reality, it could prove to be a negotiation nightmare to first reach a settlement through a difficult process of compromises for one maritime boundary and then start another process in order to negotiate a settlement for the next maritime boundary/zone. Therefore, the

single maritime boundary solution seems to be a reasonable outcome of the coastal state jurisdiction extension over the resources of the EEZ and the alignment of the jurisdiction with preexisting rights over the continental shelf. Also, the ICJ in its judgment in the Libya-Malta case asserted that ‘…the two institutions—continental shelf and exclusive economic zone—are linked together in modern law. Since the rights enjoyed by a state over its continental shelf would also include the seabed and subsoil of any exclusive economic zone which it might proclaim, one of the relevant circumstances to be taken into account for the delimitation of the continental shelf is the legally permissible extent of the exclusive economic zone appertaining to that same state’ [

93]. Furthermore, the court stated: ‘…

it follows that, for juridical and practical reasons, the distance criterion must now apply to the continental shelf as well as to the exclusive economic zone; and this quite apart from the provision as to distance in paragraph 1 of Article 76 UNCLOS’ [

51].

Unlike the continental shelf, the EEZ does not exist

ipso facto but has to be proclaimed and a request to delimit the EEZ entails the delimitation of both elements [

94]. Therefore, if the

Aegean dispute finally reaches the ICJ, a request has to be made by Greece that the court’s judgment should be directed to the delimitation of both the continental shelf and the EEZ. This prerequisite should be put in a future agenda for the delimitation of maritime zones between Greece and Turkey, either through a bilateral agreement, arbitration or better through resorting to the jurisdiction of the respective International Tribunals; the latter being the designated choice of the authors. Hence, assuming that the Greco-Turkish differences are of a legal context—and that is the reality—then, according to the international experience, practice and, moreover, according to the international law, their settlement should take place before a jurisdictional Court of Justice or another relevant institution [

95].

Political methods like negotiations may lead to deviations from the implementation of international law regulations. The history of such negotiations, like the Continental Shelf agreement between Italy and Greece, does not apply in the Aegean case due to the long-term tension between Greece and Turkey. Tension that has been triggered not only by maritime zones issues but perhaps more importantly due to sovereignty claims concerning some of the Aegean islands Turkey unduly contests. Moreover, the contribution of ICJ in international peace and security is worth noting, notwithstanding the critique it has received for its questionable decisions enhanced by the suspiciousness by many states regarding political motivation. Therefore, the national interest of Greece lines up with the support of the international justice and its institutions [

96]. On the other hand, the persistent, denial of Turkey, counting almost 40 years, to consent to the resolution of the Continental Shelf dispute with Greece before the ICJ arguably shows an unaccountable state practice in legal and diplomatic terms. The continuant slides into negotiations that

may lead to an agreement for the resolution of the difference in Hague, may demonstrate desire on behalf of Turkey to enclose Greece in endless dialogues and negotiations as well as in an increasingly widening agenda of differences, so as to gain numerous collateral profits [

97].