Reform of the Belgian Justice System: Changes to the Role of Jurisdiction Chief, the Empowerment of Local Managers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Contextual Setting

2.1. First Period of Managerialization: Big Demands for Small Reforms

2.2. The Reform of 2014: A Change in the Management Paradigm for Jurisdiction Chiefs

2.3. The Law of 18 February 2014

3. The Methodological Approach: Qualitative Empirical Research

4. Developments in the Role and Function of the Jurisdiction Chiefs

4.1. Collegial Management through the Executive Committee

4.2. Management of Staff Deficits by Ingenuity and Creativity

4.3. Integration of the Rationalisation Objectives

“I think we are being tricked. Things are [well] presented to us. An acidic sweet has been added to the chocolate. At the moment, we are tasting the chocolate but soon you will see a grimace […]. It is urgent that we wake up to this fact”.(a Jurisdiction chief of the bench).

4.4. The Jurisdictional Aspect of the Function of Jurisdiction Chiefs

4.5. The Many Hats Worn by the Jurisdiction Chiefs

5. Concluding Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ackerman, Werner, and Benoît Bastard. 1988. Efficacité et gestion dans l’institution judiciaire. Revue Interdisciplinaire d’Etudes Juridiques 20: 19–48. [Google Scholar]

- Chappuis, Raymond, and Raymond Thomas. 1995. Rôle et Statut. Paris: PUF. [Google Scholar]

- Daems, Tom, Eric Maes, and Luc Robert. 2013. Crime, criminal justice and criminology in Belgium. European Journal of Criminology 10: 237–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvaux, David, and Frédéric Schoenaers. 2009. La mesure de la charge de travail des magistrats: Analyse d’un dispositif de modernisation de la Justice. Performance Publique Larcier 2: 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Di Maggio, Paul J., and Walter W. Powell. 1983. The iron-cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational field. American Sociological Review 48: 147–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunleavy, Patrick, and Christopher Hood. 1994. From old public administration to new public management. Public Money and Management 14: 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabri, Marco, and Philip M. Langbroek. 2000. The Challenge of Change for Judicial Systems. Amsterdam: IOS Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ficet, Joël. 2010. Entre efficience et indépendance. Le projet de ‘reconfiguration du paysage judiciaire’. Journal du Droit des Jeunes 295: 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Fijnaut, Cyrille. 2001. Crisis and reform in Belgium: The Dutroux affair and the criminal justice system. In Managing Crises, Threats, Dilemmas, Opportunities. Edited by Rosenthal Uriel, Arjen Boin and Louise Kloos Comfort. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas, pp. 235–50. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, Barney G. 2001. The Grounded Theory Perspective: Conceptualization Contrasted with Description. Mill Valley: Sociology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guarnieri, Carlos, and Patrizia Pederzoli. 1996. La Puissance de Juger. Paris: Michalon. [Google Scholar]

- Guillemette, François. 2006. L’approche de la Grounded Theory; pour innover. Recherches Qualitatives 26: 32–50. [Google Scholar]

- Heughebaert, P. 2012. Avocat et Juge Suppléant, ou l’art de Retourner sa Toge. Available online: http://www.justice-en-ligne.be/article504.html (accessed on 25 June 2017).

- Hondeghem, Annie, and Bruno Broucker. 2016. From octopus to the reorganization of the judicial landscape in Belgium. In Modernization of the Criminal Justice Chain and the Judicial System. New Insights on Trust. Edited by Hondeghem Annie, Xavier Rousseaux and Frédéric Schoenaers. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Marchandise, Thierry. 2013. Concilier le management avec les valeurs du judiciaire. In Quel Management Pour Quelle Justice. Bruxelles: Larcier, pp. 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Mattijs, Jan. 2006. Implications managériales de l’indépendance de la Justice. Pyramides 11: 65–102. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, Pierre. 2015. Les Politiques Publiques. Paris: PUF. [Google Scholar]

- Peretz, Henri. 2004. Les Méthodes en Sociologie. L’observation. Paris: La Découverte. [Google Scholar]

- Pichault, François, and Frédéric Schoenaers. 2012. Le middle management sous pression. La difficile intégration du référentiel managérial du NPM dans les organisations au service de l’intérêt general. Revue Internationale de Psychosociologie et de Gestion des Comportements Organisationnels 18: 121–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piraux, Alexandre. 2017. La justice sous contrat de gestion avec le pouvoir exécutif. Pyramides CERAP 27: 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rouleau, Linda. 2005. Micro-practices of strategic sensemaking and sensegiving: How middle managers interpret and sell change every day. Journal of Management Studies 42: 1413–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenaers, Frédéric. 2014. Lorsque le management entre au tribunal: Évolution ou revolution. Revue de Droit de l’ULB 41: 171–209. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Anselm L., Marc-Henry Soulet, Juliet M. Corbin, Stéphanie Emery, and Marc-Henry Soulet. 2004. Les Fondements de la Recherche Qualitative. Techniques et Procédures de Développement de la Théorie Enracinée. Fribourg: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thunus, Sophie, and Frederic Schoenaers. 2012. When policy makers consult professional groups in public policy formation: Transversal consultation in the Belgian Mental Health Sector. Policy and Society 31: 145–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauchez, Antoine, and Laurent Willemez. 2007. La Justice Face à ses Réformateurs (1980–2006). Paris: PUF. [Google Scholar]

- Vigour, Cécile. 2004. Réformer la justice en Europe: Analyse comparative des cas de la Belgique, de la France et de l’Italie. Droit et Société 56: 291–325. [Google Scholar]

- Vigour, Cécile. 2017. La justice, entre institution, professions et organisation. Redéfinition des équilibres en Europe. In Justice 2020—Les Enjeux du Futur. Anvers: Maklu, pp. 49–76. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick, Donald P. 1975. A Theory of Public Bureaucracy. Boston: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, Russell R., and Howard R. Whitcomb. 1977. Judicial Administration: Texts and Readings. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | This article has been realized with the support of BELSP0 programs PAI 7/22 and BRAIN/JAM. |

| 2 | Based on the laws of 1 December 2013 for the reform of the legal districts, and the modification of the judicial code with a view to strengthening the mobility of members of the Judicial Order (M.B. 10.12.2013) and 18 February 2014 relative to the introduction of autonomous management for the Judiciary (M.B. 04.03.2014). |

| 3 | This term includes the presidents of the courts of appeal and the labour courts, the presidents of the courts of first instance, commerce, labour, peace courts and judges of the police courts, as well as general public prosecutors (appeal level), public prosecutors and labour auditors for the public ministry. They are considered as the “local managers” in the Belgian Judicial system. |

| 4 | In parentheses, we give the “official” name of the judgment levels and jurisdiction types in French language (when different than English translation). |

| 5 | Remark: The Court of Assise (dealing with the most important crimes such as murders and based on a bench composed of professional judges and a civil jury) is organised at the provincial level. There are 11 of them. Recently the criminal has been reformed and the competences of the Court of Assise were reduced. In the future, the Court of Assise referral shold be an exception. |

| 6 | In 1996, a young girl was kidnapped in Belgium. Marc Dutroux, his wife and a third person were arrested. In August 1996, the police found two girls alive in a cage in Dutroux’s house, and a few weeks later, four other girls, kidnapped in the years before, were found buried at Dutroux’s house.

In April 1998, Dutroux escaped from a courthouse due to the carelessness of a police officer. He was captured a few hours later, but both the Minister of Justice and the Minister of Internal Affairs resigned. The ‘Dutroux-case’ triggered political debates regarding failures in the Belgian criminal justice system. Since that time, the Belgian Justice System has been involved in important and deep reforms. |

| 7 | Formulated by the political class but also by the media and civil society. |

| 8 | Which could be summarised around the notion of “strengthening the profile of the public service” with the objective of improving quality, efficacy, efficiency, and transparency. |

| 9 | The Octopus Agreement was signed by the eight democratic political parties present in Parliament after a week-end of crisis meetings. These meeting followed the escape attempt on the part of Marc Dutroux. The Octopus Agreement contained a set of decisions and principles aimed at reorganizing the police and justice departments. |

| 10 | Loi du 1er décembre 2013 portant réforme des arrondissements judiciaires et modifiant le Code judiciaire en vue de renforcer la mobilité des membres de l’Ordre judiciaire (M.B. 10.12.2013). |

| 11 | Loi du 18 février 2014 relative à l’introduction d’une gestion autonome pour l’organisation judiciaire (M.B. 04.03.2014). |

| 12 | “Presentation of motives”, Document of the Bench, No. 53 3068/001. |

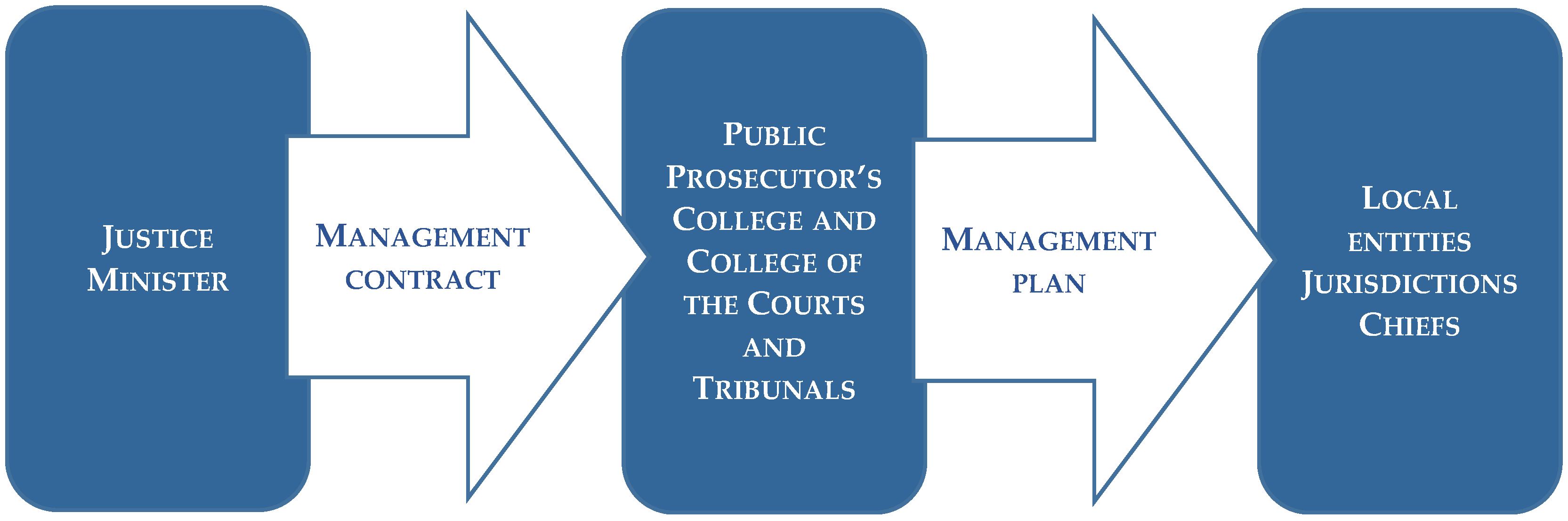

| 13 | The Public Prosecutor’s College included six members designated by law for their function of Federal Prosecutor, as well as four elected members, three of whom are public prosecutors and a work labour auditor. |

| 14 | The College of Courts and Tribunals is composed of ten elected members, three presidents of the court of appeal, a president of the labour court, three presidents of the court of first instance, a president of the labour tribunal, a president of the court of commerce, a president of the judges of the peace, and a president of the judges of the police tribunal. |

| 15 | One president of the court of appeal, one president of the labour court, one Prosecutor General, five presidents of courts of first instance, one president of the court of commerce, one president of the labour tribunal, one president of the judges of the peace and the judges of the police tribunal, three Public Prosecutors and one Labour Auditor. |

| 16 | Members of the Institute of Legal Training, the High Council of Justice, the Public Service Federal Justice, the former Commission for Modernisation of the justice system etc. |

| 17 | In this contribution, the distinction between Judges and Prosecutors will not be used as a discriminating criterion for data analysis. Conversely, we will report, through our five themes, similar experiences in terms of the role of Jurisdiction chiefs. |

| 18 | In order to preserve the anonymity of our group of interlocutors, we will use the masculine form to identify the Jurisdiction chiefs we met when relating what they said. |

| 19 | “The vice-presidents […], their main function was to judge […] but if you look at [their] job description it means being involved in the day-to-day workings […]. I made a few different attempts […], [we] created a sort of college of vice-presidents to try to distribute the tasks but this was a total failure. Because they told me […], we are prepared to do the tasks of the vice-president but we need to be relieved of the jurisdictional tasks […]. And that is a luxury” (a jurisdiction chief of the bench). |

| 20 | “I have the problem of divisional chiefs. These should be my right-hand men therefore persons of confidence […] I was supposed to suggest candidates for my General Assembly […] but the members did not follow my suggestion for one year. Was this so that they wanted that the chosen person would not be directly in my vision and [to] weaken the President, I don’t know the reasons […]. If you are given an individual you don’t want, that creates problems” (a jurisdiction chief of the bench). |

| 21 | With the exception of the Brussels-based bodies whose managerial staffing is maintained at one hundred percent. |

| 22 | A measure strongly criticised by the President of the Court of Appeal, within whose jurisdiction lies the Tribunal of First Instance, whose President favoured this option. |

| 23 | These functions of the substitute judge can be assumed by lawyers, doctors or law graduates (Heughebaert 2012). |

| 24 | The First President of the Court of Appeal within whose jurisdiction the Tribunal of First Instance in question is located, confided to us that horizontal mobility could have, and should have, constituted a favourable option when it came to making up a deficit in staff, and allow for the carrying out of planned hearings. |

| 25 | “I always say: the law doesn’t only work with volunteers’’. It is volunteerism pure and simple. The law works just like the Red Cross with all these volunteers today” (an assistant to a jurisdiction chief of the bench). |

| 26 | “Basically, I am convinced that there is a lot of saving to be made everywhere […]. I said this to the Minister: “I am convinced that savings are possible but give us time […], six months, one year, to give you some suggestions […] intelligent savings and without stabbing the members of staff” (a jurisdiction chief of the bench). |

| 27 | [continuation of the previous extract] “… perhaps it is necessary to work on the number of staff members but, in any case, not for now. Give us time to stabilize […], observe how and where we could make savings […]. This requires a review of our practices and […] success […]. Later, we could do with fewer staff but we’ll have to see” (a chief of the bench). |

| 28 | “I think that the captain must not be in the engine room but rather up on deck […]. This is why I do not want [to put my energy into] structurally [in hearing roles] but there are others who still like that” (a jurisdiction chief of the Bench). |

| 29 | Among these, accelerated procedures, abrogation’s etc. |

| 30 | “A reason for why we must remain in the jurisdictional function, […] it is [because] we can exercise management and more management, if you lose the knowledge of what we call judging, you will perhaps become a very good manager but not within the legal machine. Just like the great restaurant owners […], there is a golden rule and that is, that they [are] still capable of going into the kitchen if ever there is a problem. And I believe that that is the basis” (a jurisdiction chief of the bench). |

| 31 | The subjects of terrorism and radicalism are also the object of centralisation by the jurisdiction chiefs. |

| 32 | “The fact that we are chronically understaffed means that my first reflex is to say: “I’m going to look after myself”. Then I realise that I can’t spend enough time in jurisdictional and that I am indeed losing quality in my job as a manager because I am losing time with this sort of thing” (a Jurisdiction chief of the Office of the Public Prosecutor). |

| 33 | “There I took a decision […] to create a magistrate of reference […] which is not me […]. I will do so, [not] because I have to, but because I choose to. In this way, I will be of more use to the Institution […]. The best way to completely miss one’s managerial mission, is to continue to act operationally because, in fact, you are neither one nor the other […]. Therefore, I pass the buck […] but it’s not easy […] especially when everyone is complaining about being […] overloaded. In this case I say: I don’t care, you are overloaded? Ah well, that makes two of us” (a Jurisdiction chief of the Office of the Public Prosecutor). |

| 34 | “The daily work of the jurisdiction chief means that he is very busy, but what is difficult is to combine roles. He has the role of jurisdiction chief but there is also everything that comes with that role […]. Therefore, it doesn’t hurt […], because he has several hats” (a jurisdiction chief of the Office of the Public Prosecutor). |

| 35 | Articles 398 and 400 of Chapter I—Conditions governing hierarchy and surveillance, of Title V—Discipline, the second part: The Judicial organization, the Judicial Code of 10 October 1967. |

| 36 | “Up to the present, I have not […] organised any consultation […]. These are seminars which I have with one or other [jurisdiction chief] but I didn’t do this any more […]. The jurisdiction chief’s mission is not the mission of the Jurisdiction chief of the Court of Appeal […]. I know that some people do it but I don’t, and nor do I have the time to do it” (a jurisdiction chief of the bench). |

| 37 | Article 184, §2, paragraph 2 of the judicial code—“The College of the Office of the Public Prosecutor is presided over by the President of the College of Prosecutors [appointed for the current year]”. |

| 38 | “In the College, it is necessary […] to constantly take decisions, over a very short time period, on matters about which I am not sure to have all the information. I find that difficult. […] If we talk about the future or take decisions on the budget […]. Sorry, I don’t know […]. Therefore, I am unhappy. I find that now, we are taking important decisions, but we are doing so with amateurs who are doing their best. It is not amazing” (a Jurisdiction chief of the bench, member of the College of Courts and Tribunals). |

| 39 | “In the College […], it’s a work term […], I don’t know if I want to do it again […]. It is fascinating because we know everything and we are in the strategic decision-making process with regard to everything that happens. But when I see the time that [that] takes me […], I say to myself, can I continue like that for five years […] doing four-fifths of my work [here]?” (a Jurisdiction chief of the Office of the Public Prosecutor, and member of the College of Public Prosecutor). |

| Level of Judgment5 | Courts | Public Prosecution |

|---|---|---|

| Federal | Court of Cassation (1) (“cour de cassation”) | Prosecutor-general at the Court of Cassation (1) (“parquet general près la cour de cassation”) Federal Prosecutor (1) (parquet fédéral) |

| Second level judicial areas (“ressort” level) | Court of Appeal (5) (“cours d’appel” Labour Tribunal (5) (“cours du travail”) Court of Commerce (9) (« tribunaux de commerce ») | Prosecution-general (including public prosecutors for labor legislation) (5) (“parquet general en ce compris l’auditorat general du travail) |

| District (“arrondissement judiciaire”) | Courts of First Instance (13) (« tribunaux de première instance ») Police Courts (15) (« tribunaux de police ») Labour Court (9) (« tribunaux du travail ») | Public Prosecutor’s Office (14) (“parquet du procureur du roi) Public Prosecutor for Labour (9) (also called “Labour Auditor”) (“auditorat du travail”) |

| Canton | Peace Courts (187) (« justice de paix ») |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dupont, E.; Schoenaers, F. Reform of the Belgian Justice System: Changes to the Role of Jurisdiction Chief, the Empowerment of Local Managers. Laws 2018, 7, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws7010002

Dupont E, Schoenaers F. Reform of the Belgian Justice System: Changes to the Role of Jurisdiction Chief, the Empowerment of Local Managers. Laws. 2018; 7(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws7010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleDupont, Emilie, and Frédéric Schoenaers. 2018. "Reform of the Belgian Justice System: Changes to the Role of Jurisdiction Chief, the Empowerment of Local Managers" Laws 7, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws7010002

APA StyleDupont, E., & Schoenaers, F. (2018). Reform of the Belgian Justice System: Changes to the Role of Jurisdiction Chief, the Empowerment of Local Managers. Laws, 7(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws7010002