Abstract

Gender equality at work in male-dominated industries is conditioned by intrinsic systemic issues which established policies have, to a significant extent, failed to address, as women’s participation remains under-represented. This study argues for the reappraisal of the issue through a different lens and carries out a systematic and thematic review of the literature on women in construction in Australia through a women’s empowerment framework. Despite its usual application in gender inequality at work in development studies, the concept of empowerment lacks attention in the context of developed countries, particularly regarding the construction industry. Empowerment has been proved a useful overarching framework to analyse personal, relational, and environmental factors affecting women’s ability to be or do. In the examined studies, there is significant focus on external barriers to women in construction, such ‘organisational practices’ (environmental), ‘support’ and ‘others’ attitudes and behaviour’ (relational). There is, however, limited attention to more active stances of power, such as one’s attitude (personal), control and capacity, in shifting power dynamics. The paper draws seven major findings, covering personal, relational and environmental dimensions, supported and supplemented by some international studies, and suggests the way forward for empowering women in construction.

1. Introduction

According to the Australian Industry and Skills Committee (AISC), construction is the third largest industry nationally, with a projected annual growth rate of 2.4%, being the second sector of greater expected employment growth (10%) for 2023 [1]. Women’s participation in this significant economic sector accounts for a very small proportion, with declining numbers from 17% in 2006 to 12.9% in 2020. Failing to tap into the female workforce further accentuates problems with the forecasted skill shortage in the industry [1]. The Victorian state government took the lead nationally by proposing a comprehensive strategic plan to attract, recruit and retain women in construction, particularly in trades occupations [2], approaching what is recognised as a long “leaking pipeway” [3]. The proposed strategies respond to identified barriers to the inclusion of women in construction in general, mirroring discussions in national and overseas literature [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. For instance, strategies to improve women’s attraction to the industry aims at changing the general negative perception of the work environment, its inappropriate culture for women and rigid work practice, coupled with a lack of encouragement from educational institutions [4,12]. In recruiting and advancing women’s career in construction, strategies are proposed to overcome the issue of employers’ biased decisions and informal practices [7,8,16]. Retention is strategised through defining better actions to report on harassment, create more flexible work practices and improve occupational health and safety [17].

Researchers have taken a further step to provide evidence-based on two points of intervention from the Australian Victorian State Government initiatives [18]. Findings show that companies are not tackling the issue evenly, and while some women only have had positive work experiences, a substantial number of participants still report on issues that range from discrimination to sexual assault. Holdsworth et al. [18] suggest the importance of psychological coping mechanisms, such as the support of trusted network of friends and family, among other resilience strategies also discussed in the literature [19].

The gender issue in construction is also a global concern as demonstrated by the research efforts in this area. For example, Hegarty [20] explored women’s experiences of entering, working in and leaving the construction industry in New Zealand between 2010 and 2018. Silva and Dominguez [21] carried out research in Chile on improving female construction engineering students’ experience throughout their careers. Perrenoud et al. [22] identified the attraction and retention factors for women in the U.S. electrical construction industry. Naoum et al. [23] conducted a comparative study on men’s and women’s self-perception in the UK construction industry. Thus far, all these international and Australian studies have focussed on providing external support including reducing gender discrimination, incremental changes to flexible working hours, childcare facilities, and reducing the pay gap, etc., to attract and retain women in construction. However, despite all these efforts, women remain significantly under-represented in the construction industry [24]. Therefore, a long-standing research question remains: “How to effectively attract and retain women in the construction industry?”

While most previous studies have focused on providing external supportive strategies and practices for women in construction, this research aims to use a different approach to analyse the gender issue through the lens of empowerment, and aims to provide answers to the above research question from the perspective of women’s empowerment. Empowerment is a concept used more commonly in developmental studies, being of limited consideration to the issue of women in construction.

A search on ProQuest databases resulted on 175 scholarly journals (167), reports (5), dissertations (2) and books (1) related to the topic of construction industry and women in Australia using the following keyword search function (“noft” means anywhere in the bibliographic record except full text): (noft(“construction industry” OR “building industry” OR “construction management” OR “construction company”) AND noft(female* OR women OR woman OR girl* OR gender* OR feminis*) AND noft(Australia*)). There is only one academic reference filtered after the inclusion of the keyword ‘empower*’. Yet, this study from Mahmoud et al. (2021) does not focus on gender issues, neither applies empowerment as a concept, but it is rather a general word used in the abstract. This indicates a lack of attention to examining the gender issue in construction from the angle of empowering women. This article presents a systematic review of the literature on women in construction in Australia, and the thematic analysis results through an empowerment framework. Focusing on Australia allows for in-depth analysis of the available references, and enables a meaningful discussion in the context of a developed country. Lewis and Shan [25] used a similar approach, and they carried out a literature review to identify, evaluate and integrate research findings of scholarly studies conducted within U.S. between 2010 and 2019 regarding the recruitment and retention of women in construction. While the research is based on the data and facts in a local context, due to the common nature of the issue, the research findings can be readily generalised to international context, especially developed countries. This paper presents detailed findings based on a systematic literature review in the Australian construction industry. It concludes by summarising the major findings with references and discussions of some most recent international studies. These international studies support and supplement to the findings drawn from the Australian construction industry.

Defining a Women’s Empowerment Framework

Empowerment is a concept more widely used in the social sciences, particularly in developmental debate [26]. Empowerment means a situation in which all human beings are free to develop their skills and make choices without the limitations of strict cultural views or norms, and where the different aspirations, aptitudes and needs of individuals are considered, valued, and favoured equally [27]. In a highly regarded article on empowerment theory, Zimmerman [28] explains that empowerment is a process which centres on efforts to exert control at three mutually interdependent levels of analysis: individual, organisational, and community. Zimmerman [28] further argues that participation with others to achieve goals, efforts to gain access to resources, and critical understanding of the sociopolitical environment are basic components of empowerment. Scholars and those working in developmental projects inquired on how empowerment can be achieved and what it depends on, dwelling on the root concept of power and its interdependent factors [26,29,30,31,32,33,34].

Parenti [32] explains power in three ways. One is within the self, in terms of confidence and other cognitive abilities. Another is relational, or the ability to influence others to further one’s interests. The last is political, which refers to individuals or groups determining who has what and who influences whom. Parenti [32] further contextualises self, social, and political powers in terms of access, exchange and management of resources and/or rewards. Cornwall [29] criticises that the definition of power relationships based on accessibility and exchange of resources and/or reward inherently leads to disadvantage and oppression, as not all are equal in possessions.

Pillai [35] presents a more intangible definition of power as something to be acquired and which needs to be continuously exercised, sustained, and preserved. Gilart [30] also defines power as used to further the ability of individuals, organisations or communities to take action and gain greater control over their lives, seeking greater effectiveness, personal development, and social justice. For that to happen, several factors come into play, including not only access to resources, but also self-assurance, knowledge, group identification, among others. This interpretation of power resonates with Longwe’s [36] Women’s Empowerment Framework, constituted of five elements: welfare, access, conscientisation, participation and control. The interdependence of these elements is evident in the use of the framework for the evaluation of empowerment projects. Choo and William’s [37] evaluative study using Longwe’s framework shows that welfare and access to resources have only limited and temporary reach if not followed by other transformations, particularly the cognitive elements of conscientisation and self-esteem. Thomas and Velthouse’s [38] managerial study supports the importance of the cognitive dimension to empowerment, arguing that processes of empowerment “occur within the person and refer to the task itself, rather than the context of the task or the rewards/punishments mediated by others” [38] (p. 668), highlighting the importance of personal commitment and sense of satisfaction in the action at work. There is a general view of empowerment as a multi-dimensional process. However, focusing on one dimension or the other risks overlooking the interplay of different factors and dimensions.

Critically, Rowlands [34] and Rao and Kelleher [33] explain that power has been largely interpreted from a Newtonian worldview, as a limited commodity in which the more some have, the less others will; a “zero-sum” [34] or “win-lose game” [33]. They argue for a different interpretation of power, as sharable and unlimited, consequently unifying and multiplying. Rao and Kelleher [33] (p. 76) refer to Wallace’s (1999) concurrent idea of “devolution of power” and explain that it initially requires transformative leadership coming from all levels of an organisation, not hierarchical. It depends on a commitment to learn and the establishment of open lines of dialogue, to build understanding and consensus in the drive of new directions. Such different views open grounds for new realities to be reimagined and achieved.

Oxfam, a non-profit organisation whose work focusses on the alleviation of poverty and inequality, proposes a framework for women’s empowerment in line with such views; as a multi-dimensional process, dependent on the interplay of personal, relational, and environmental factors [31], which also reflects the three levels of analysis proposed by Zimmerman [28] mentioned earlier. It also builds on Rowlands’ power structure (within, to, with, over) and the “Gender at Work” metric cluster (individual, systemic, formal, and informal), associated with Rao and Kelleher’s work [31], and consists of various factors as illustrated in Table 1. The following text presents the details of the empowerment framework from the three dimensions.

Table 1.

Women’s empowerment framework, adapted from Oxfam [21].

- (1)

- The personal dimension is “the processes that lead people to perceive themselves as able and entitled” [34] (p. 102) and refers to factors of ‘power from within’ and ‘power to’. The first is the perception of self-worth (confidence), opinion and attitude about the self-right to be or do, driven by a deep interest and passion. It relates to Rao and Kelleher’s [34] informal individual power. The second is “achieved by increasing one’s ability to resist and challenge ‘power over’”, as proposed by Liz Kelly in Rowlands [34] (p. 102). It is the formal individual capacity and skills acquired from work experience or education, raised awareness from access to information and, in developmental studies, it also includes autonomy through access to resources, which allows one’s independence [31], while also related to women’s ability to take alternative decisions and initiatives.

- (2)

- Regarding the relational dimension, Rao and Kelleher [39] (p. 77) explain that “part of the wonder of the conception of power as relational and unlimited is its potential to transform relationships, and, ultimately, human organisations and institutions”. Therefore, relational power not only enhances individual power but has the potential to influence environmental factors.Power with’ is the effect that others’ attitudes and behaviour, level of support (family, friends, mentors, supervisors), and participation in formal and informal groups or networks have on women’s empowerment. These elements are a mix of formal and informal factors in the intersect between individual and systemic dimensions. ‘Power over’ is the empowerment to make changes. Leadership is fundamental in enacting and enabling other forms of values and behaviour. Such transformative leadership takes place when there is a deep sense of commitment to a cause, generating purpose in the identification of needed actions in the relationship with others, further achieved in forms of control with others over a situation of uneven power and towards a common goal.

- (3)

- The environmental dimension refers to a larger encompassing system. It is constituted of three broad aspects: organisational procedures, policies and regulations, and culture.Organisational procedures are established traditional practices, which can be detrimental if defined by gender norms or other forms of exclusionary order. As Rao and Kelleher [39] assert, changing requires “commitment to more flexibility and responsiveness in the work of the organisation” in the “devolution of power”. These procedural changes are initiated by new policies and regulations: “the scope for individuals inside organisations to push a particular agenda is limited by the formal institutional systems and procedures—the ‘rules of the game’, and the degree to which the formal rules are enforced” [39] (p. 74). Rao and Kelleher [34] discuss that UN’s adoption of policies and regulations have showed positive impact initially; however, their capacity for in-depth change is limited. This is often due to more intrinsic cultural systems. Culture permeates and influences unspoken norms of behaviour and codes of conduct, language, symbols, myths and social customs and stereotypification [39]. To challenge this, there needs to be an organisational commitment to engage with and respond to the issue of women in construction, to see the value and establish a vision for change to occur.The change of culture may also initiate from external environment to an organisation, for example, recent technology advancements and construction industrialisation has caused widespread adoption of digital tools and prefabrication in construction [40,41]. This has made a significant impact on construction culture: physical strength is less important for trade works as more advanced machineries are available, and remote monitoring and inspection of construction sites are now possible, which reduces travel time and provides options for flexible working hours. The recent COVID-19 pandemic has also had a huge impact on the construction industry’s culture, resulting in the widespread adoption of communications via online platforms.

Together, these different factors within the three dimensions interrelate and influence each other in the process of women’s empowerment at work. In this paper, the empowerment framework is used to analyse the literature on women in the Australian construction industry. The systematic and thematic review of the literature allow for a comprehensive review and different interpretation of the existing debate, characterising them under the different dimensions and factors of empowerment. The analysis is based on the findings from the Australian construction industry, which represents a scenario of developed countries. As a pilot attempt to understand the gender issue in construction via the women’s empowerment framework, the research findings will provide good guidance to further exploration in other countries, and in global scale.

2. Methodology

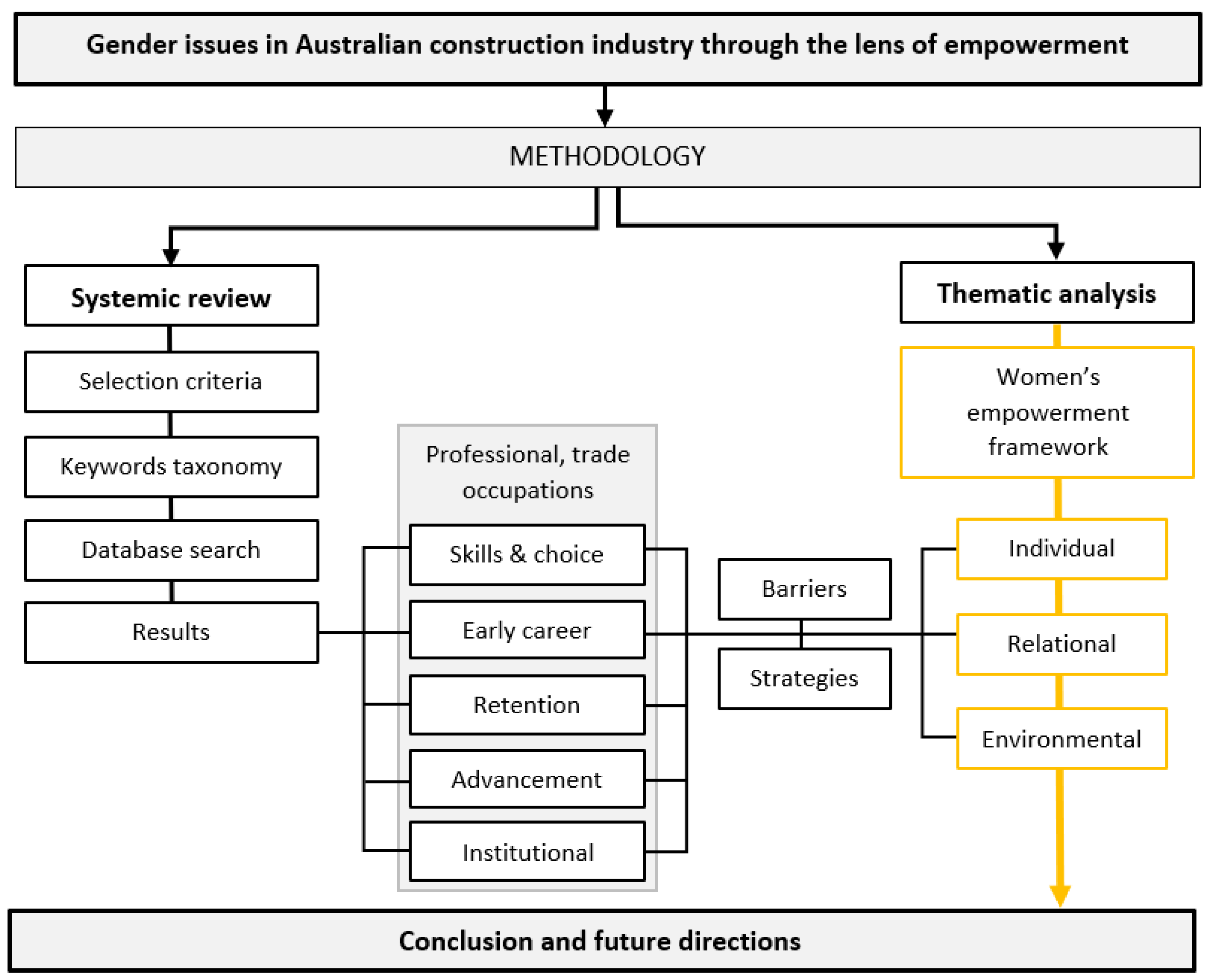

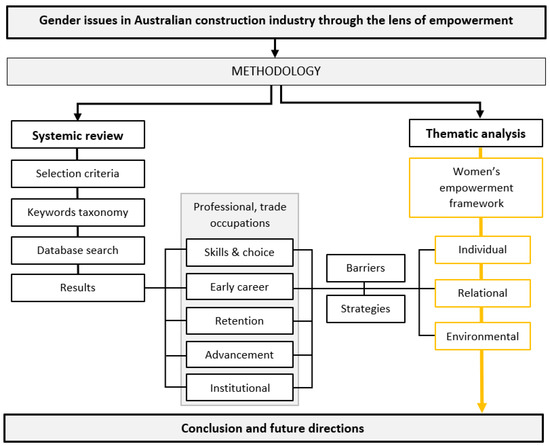

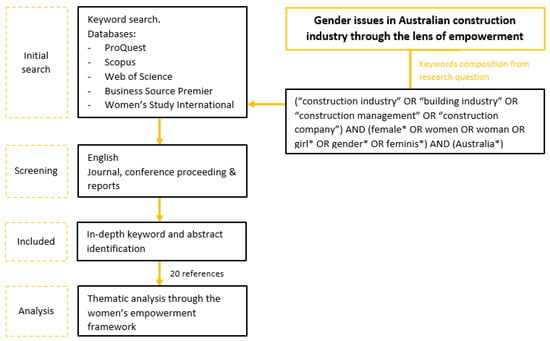

Systematic literature reviews are replicable and transparent scientific methods for the identification of relevant literature and consistent processes of review [42]. Qualitative systematic reviews were used for evidence-informed policy and practice work. They construct new knowledge from the structured interpretation of a body of existing work [42]. Reflecting this, studies on women in the construction industry are normally qualitative, and often with the end-goal of informing policy and practical initiatives. This systemic review uses a thematic analysis for the interpretation of such literature, categorising and interpreting findings from previous work under the different factors of women’s empowerment (illustrated in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Methodological approach to the analysis of women’s empowerment in construction in Australia.

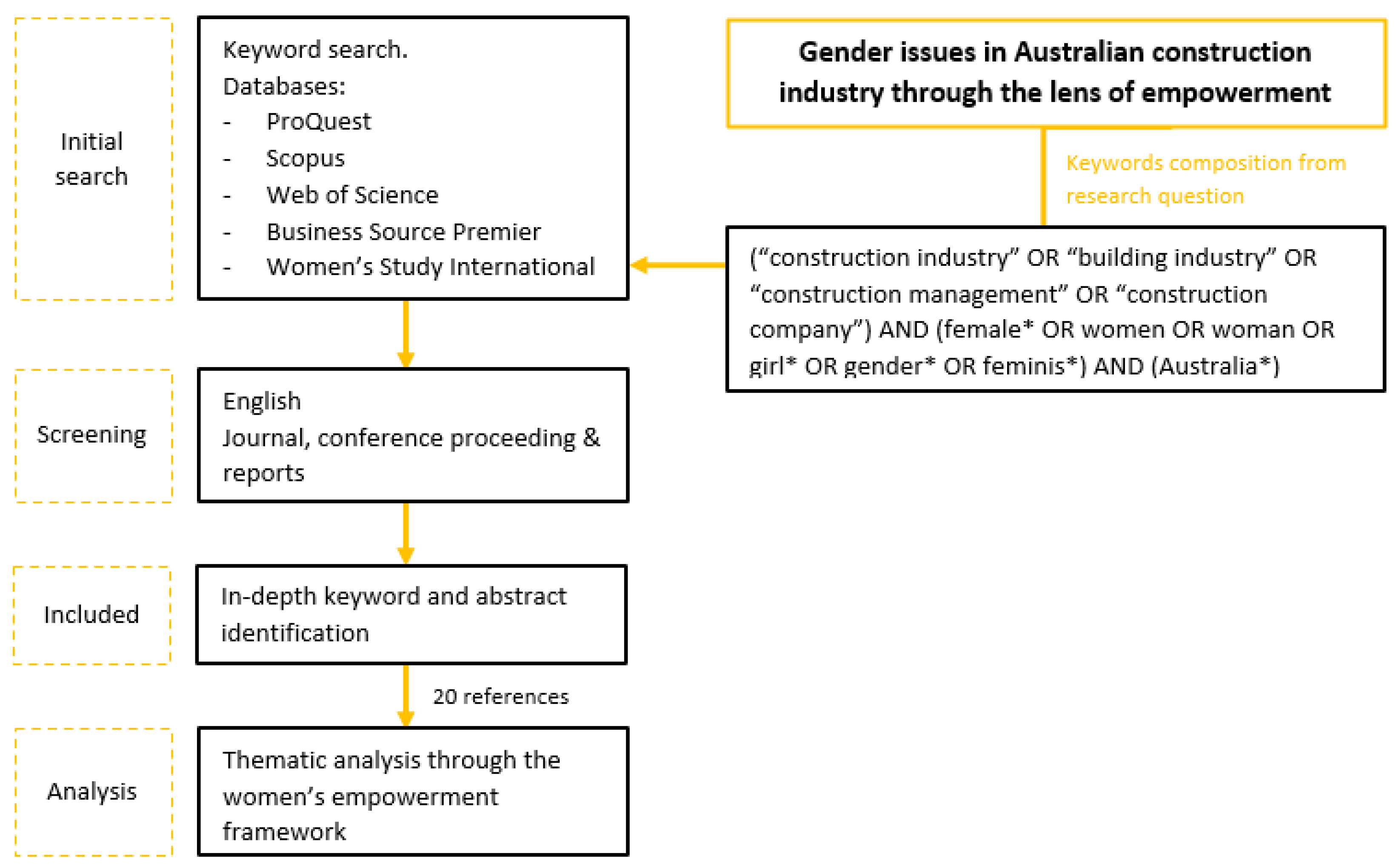

The first step of a systemic review is to define the keywords. Keywords selected in this study should be related to ‘construction industry’, ‘women’ and Australia. The established string of keywords used in the database search was: (“construction industry” OR “building industry” OR “construction management” OR “construction company”) AND (female* OR women OR woman OR girl* OR gender* OR feminis*) AND (Australia*). The search included all fields besides from the full text.

Secondly, suitable databases are considered. There are some systematic comparisons of various databases [43,44,45], and the most three widely used databases are Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar [43]. According to Gusenbauer and Haddaway’s evaluation [45], Google Scholar, though it has a large coverage of literature, provides very low-precision search results, and it does not support many of the features required for systematic searches. Therefore, Google Scholar is not used in this study. Based on the topic of this research, a list of relevant databases was selected. We first used the specific databases of Business Source Premier and Women’s Studies International. The former includes several studies on construction industry and construction management with women’s participation issues having a more business focus, and the latter a more feminist and gendered focus. We then used the broader search engines of ProQuest, Scopus and Web of Science to include work from varied disciplinary backgrounds. In all searches, keywords were defined with an intention to find relevant multi-disciplinary publications on women in construction in Australia, and the filters used were year range (2012–2021), subject (exclude medicine), and source type (academic journal, reports and conference proceedings).

Thirdly, a set of criteria was established to select the relevant articles. Given that empowerment is dependent on external factors that are highly contextual due to a multitude of cultural, religious and regulatory factors, only those studies focused on the Australian context were considered. We further filtered the search by only including studies from peer-reviewed journals, conference proceedings and reports. After these initial filters, articles were further selected by reviewing the abstracts. Articles related to general issues of social procurement, disadvantaged groups or social inequality issues were excluded. While gender inequality and women as minority groups are part of these studies, the interest of this research is only on the issue of women in construction. We also excluded studies related only to masculinity and cultural issues in general, without focusing on women in the construction industry. The replicable process for the systemic review is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Methodology of conducting the systemic literature review (note: * means the end of the word is open to all extensions).

Articles included regarded all phases of women’s participation in the industry: career choice, early career and retention and career advancement. Articles selected also concerned both trades and professional occupations in construction. Table 2 shows a breakdown of the number of references in relation to each of the steps of the systematic review process, after applying the filters and the final selection process. Lastly, the references from each database were imported to EndNote, after which duplicated references were eliminated and further filtering was applied through an initial abstract review and further in-depth review of the references, to ensure that all references followed the specified set of criteria mentioned above. The final number of references was 20. These were considered for in-depth thematic analysis, using the women’s empowerment framework adapted from Oxfam.

Table 2.

Database search results.

Before the thematic analysis, the articles were scanned for an initial understanding of the different theoretical underpins, methodologies, main findings and the focus of the studies. After, QRS Nvivo 12 was used to analyse the selected references and classify them into the themes of women’s empowerment. The personal, relational and environmental dimensions of empowerment and their related factors were entered as nodes and sub-nodes for coding the findings and discussions sections from the articles. The discussion of the findings follows the thematic structure of women’s empowerment, attending to how they influence the different phases of career choice, early career, retention and progression, as well noting differences between trades and professional occupations. The coding was limited to the third level themes, or the empowerment factors.

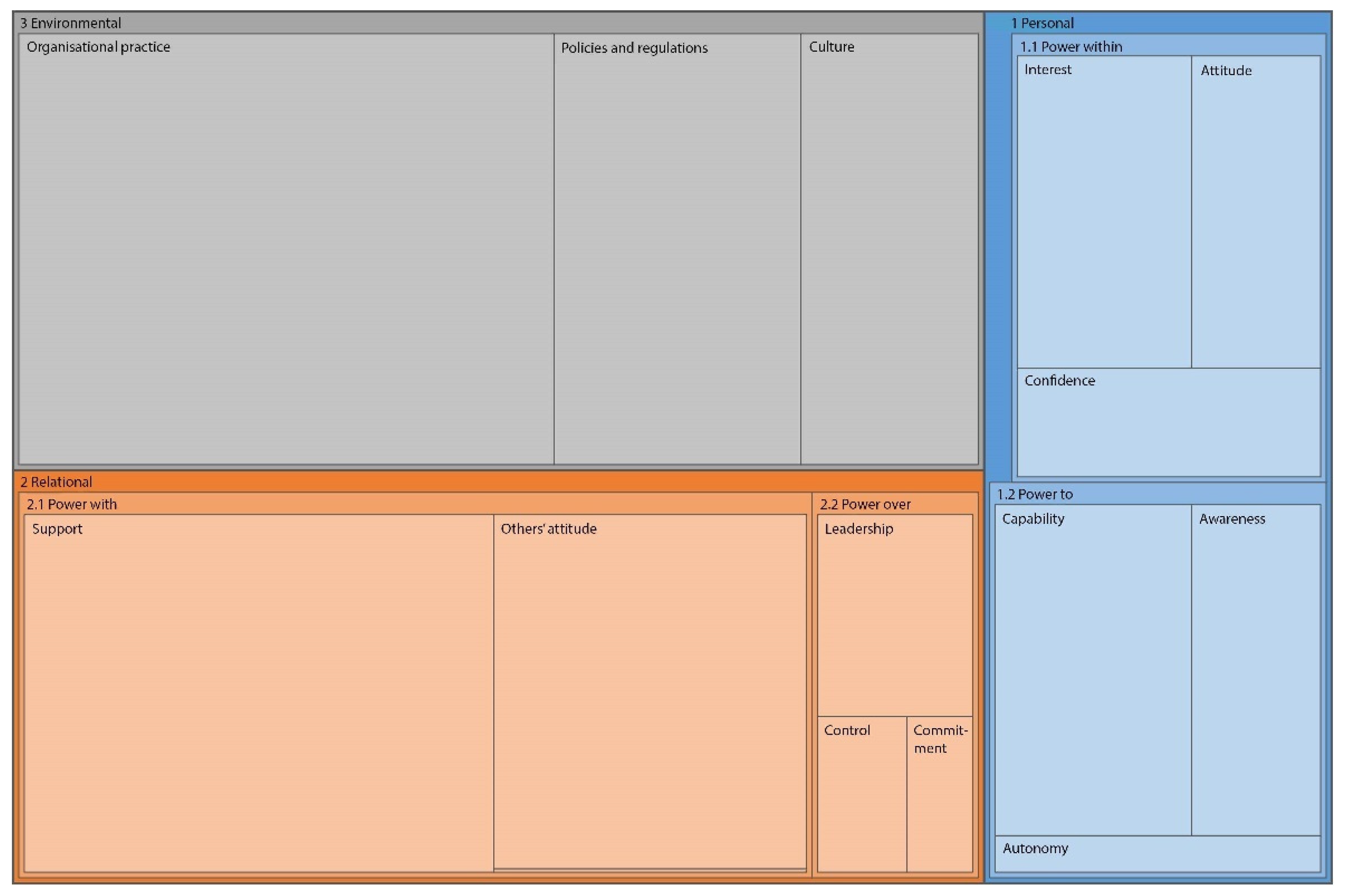

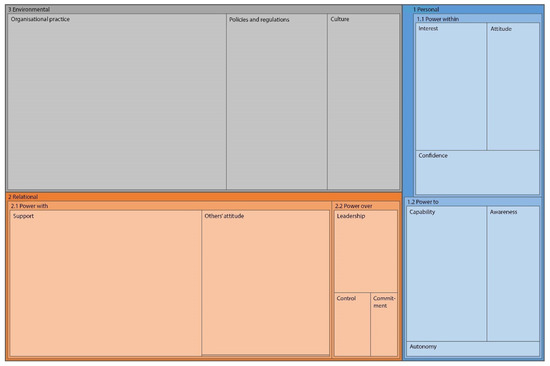

Table 3 shows the number of references and the number of articles coded under each node. The number of references were manually picked after carefully going through all 20 papers and identifying related text in the papers, and they indicate that some factors were heavily researched, while others are much less explored. To illustrate this difference more clearly, Figure 3 presents a hierarchy diagram produced by QRS Nvivo 12. The different sizes of area given to each of these factors (as shown in Figure 3) represent the number of references associated with each (as given in Table 3). It becomes visible that the factors of ‘organisational practice’ and ‘policies and regulations’, under the environmental dimension, together with the factors of ‘support’ and ‘others’ attitudes and behaviour’, under the relational dimension, are of much greater representation than the other factors. The personal dimension in itself received a much lower number of mentions in the studies, although Francis [7] highlights that it is a dimension of great importance. Our study shows how many of these factors, together with other more active relational factors under ‘power over’, have been understudied and deserve greater attention in order to define strategies to better guide women in the construction industry, in addition to the known defined strategies for the industry. The qualitative comments are discussed next.

Table 3.

Number of files and references coded at each of the nodes, or factors of empowerment.

Figure 3.

Hierarchy of nodes produced in Nvivo, illustrating the predominance of discussions under larger nodes.

3. Results

The thematic analysis involved reinterpreting the findings and discussions in the literature as personal, relational and environmental factors affecting women’s career choice, retention and progression. From the number of references in the different nodes (Table 3 and Figure 3), it becomes evident that the existing literature has a significantly greater focus on the relational and environmental dimensions of empowerment, and specifically on the factors of others’ attitudes and behaviour, support and organisational practice. These are less active stances to empowerment, looking at the barriers from others and the environment, rather than either personal or even relational factors of empowerment characterised by a more active approach (e.g., participation and engagement, motivation and control). Nonetheless, although not analysed in depth by the revised references, some of the literature points to the importance of personal factors, such as self-derived motivation, interest, proactive personality, aspirations, skill and confidence, to women’s attraction, retention and progression in the construction industry [7,46,47,48,49,50].

The following sections discusses in detail how the literature addressed each factor in three dimensions of the empowerment framework.

3.1. Personal: Power from Within

3.1.1. Interest

Some of the findings in the analysed literature indicate that having strong interest and passion for the career of choice is likely to support resilience for women in construction. Oo et al. [46] found that there is a tendency for women to “stay in trades career because of their own interests and passion for their trades, and the associated pleasure and job satisfaction” [46] (p. 10). This is supported by Smith’s [50] sociological research where participants’ narratives show the deep sense of satisfaction and accomplishment by working as tradeswomen, the completeness felt with the physical and mental demands of the work, facilitating a different understanding of their body and, consequently, overcoming gendered views of the world.

For professional roles, Oo et al. [47] survey with construction management graduates suggests that work opportunity and salary levels are decisive elements for career choice, followed by a sense of self-efficacy. Studies reveal that achieving aspirations and expectations are correlated with satisfaction in the industry [47,48]. Despite the challenges of building a career in the industry, participants reported a surprising sense of satisfaction with working in the construction industry, correlated with the above-mentioned conditions [47].

3.1.2. Attitude

Personal attitude was not a factor largely debated in the literature, but an important point was highlighted regarding women’s attitudes in the workplace. Participants in Pringle and Winning’s [49] study negatively characterised women’s shifting feminist views as ‘whinging’ or concession-seekers. It is a consensus among participants that “a good female tradesperson can work effectively in any area”, and that they should not “be overly sensitive” and be able to take criticism, jokes and “smart remarks” [49] (pp. 224–225), as also supported by others [8,46,50]. In general, it is about tuning self-attitude with a focus on the job, rather than gender issues, with participants in Oo et al. [46] discussing that this leads to fruitful relationships, respect and job satisfaction. Participants in Smith’s [50] research also held the view when women are not concerned with proving their ‘worth’ they can better navigate some challenges of the trades work and incorporate other ‘smart’ strategies. To some extent, the challenges of physically demanding work are seen by some participant in Smith’s [50] study as an “attitude”, of “being able to” do the work. Smith [50] reflects that, for some of the participants, this attitude and consequent ability to construct the physical world is in itself “empowering”.

3.1.3. Confidence

Greater self-confidence also supports the development of enabling attitudes. Oo et al. [46] study points to confidence, defined as on one’s ability to perform well, as influential to entering and remaining in the industry. From the outset, some of the schoolgirls participating in Carnemolla’s [4] study described how their defined character of not standing up for themselves is believed as inadequate in construction. This mirrors Pringle and Winning’s [49] assertion that the choice of a career in construction requires a more proactive and determined stance. Francis [7] discusses the important influence of proactivity in women’s career development in construction and career planning [7,48]. This is also an opinion shared by male participants in Galea et al.’s [8] study, for whom being proactive, or even aggressive, is important in carving women’s way through the industry. Oo et al. [48] further associated proactivity with initiatives to overcoming barriers, including seeking support from both informal and formal networks, as well as self-promoting or showcasing construction career for women.

3.2. Personal: Power to

3.2.1. Awareness

Raising awareness about not only the opportunities but also challenges of the construction industry empowers women to better navigate it by defining their career choice, retention and progression, and finding greater satisfaction in the process [7,46]. Pringle and Winning [49] showed the awareness that high-school girls have of the construction industry is “scant” and, therefore, “the industry is perceived as unattractive” (p. 226). This issue persists to date, as female students, including those in construction programs, point to the limited information about the range of roles, opportunities and earning potential [4,48]. From the lack of information, high school girls participating in Carnemolla’s [4] study stigmatise the industry as not being prestigious enough, rather characterised by attitudes of disrespect and intimidation, and the belief that there are limited opportunities to progress. They do not see high-achieving females as role models to change their rather negative view of the industry, while many also do not see construction as relevant to their interest to contribute to society. In addition, being aware of physical and behavioural challenges of the industry can support women to better navigate the environment and relationships [46,49,50,51]. Therefore, it is important for students to become more aware of the realities of the industry so they are empowered to make career choices based on their interests and realities of the workplace, which can enhance their satisfaction and permanency in the industry [47].

3.2.2. Autonomy

Awareness and other personal factors also facilitate a sense of autonomy. Most of the debate in the analysed studies discussed women’s autonomy to overcome difficulties when there were limited opportunities to advance in the industry or the organisation [7,8,18,50,52]. Francis [7] shows women’s tendency for inter-organisational movement to advance their careers once facing limited growth within an organisation, contrasting to men’s tendency for intra-organisational movement. Self-employment is another mechanism of autonomy that women use to overcome further limits within inter-organisation mobility [52], and a better lifestyle given increasing family commitments [18]. Smith [50] raises the point that while these strategies provide women with valid autonomy, they are not, however, a strategies which enable greater challenge and change in the industry itself.

3.2.3. Capacity

Capacity is another encompassing factor that influences confidence and sense of autonomy, as well as women’s ability to overcome and even challenge some of the barriers in the construction industry [18,46,48,50]. Despite its importance, capacity is another personal factor of limited attention in the literature, especially regarding how it influences a sense of empowerment or ability to overcome external barriers. Several studies discussed the importance of not only formal training and education, but other human capital variables, such as work experience, hours of work, and in- and extra-role performances [7]. Pringle and Winning [49] bring attention to women’s views about their physical ability to work in trades. Physical strength is perceived by participants as not limitative to their career in trades and the difference in physical abilities between men and women can be addressed through collaboration and the use of technologies. Smith [50] also views that construction benefits from feminine skills, and the idea of hard and tough can be overcome by alternative, smarter methods. As further argued, the demystification of strength as a requirement in construction shows “the frailty of the reasons used to justify their [women] exclusion” [50] (p. 868). Thus, being smart about the use of strength and accepting collaboration with male co-workers allow women to contribute their skills on equal footing, exposing their competence and capability across the field [53]. As pointed previously, technology advancement and wider adoption of construction machineries also provide a fairer working environment to women as physical strength is much less required.

However, despite the widely acknowledged industry trend of digitization and Construction 4.0 [33,34], none of the identified twenty papers on gender issues in the Australian construction industry discussed its impact on the requirement of new skills and knowledge, or on the industry’s culture. This gap is identified from the review and its impact on women’s empowerment will be discussed in the next section.

Another important acquired capability for women in construction is emotional skills or resilience [8,18,19]. Sunindijo and Kamardeen [19] investigated the different gendered coping strategies to manage stress and associated health issues, pointing that both men and women adopt problem-focused coping strategies. Participants in the Holdsworth et al. [18] (p. 103) study talked about “resilience” as “an essential capability to allow them to successfully navigate the negative aspects of the construction industry”, including being aware of one’s calling, living authentically, and other stances of self-importance. Indeed, Smith [50] found that giving greater focus to work itself, rather than gendered issues, empowers participants to negotiate between gendered roles and progress in their work of passion.

3.3. Relational: Power with

3.3.1. Others’ Attitudes

Much of the debate in the literature has focused on relational factors of empowerment, more so in relation to how others’ attitudes and behaviour and the existence of support empower (or not) women in the construction industry. Other’s attitudes and behaviour based on established belief systems and traditional norms towards women in construction has been discussed in length in the analysed literature, indicating the significant impact different stakeholders have on women’s career in construction, affecting their attraction, retention and career progression.

Research shows parents significantly influence their daughters’ career decision [4,47,49]. Participants in Carnemolla’s [4] study showed a common belief that, while many parents are encouraging independent career decisions, explicitly or implicitly, construction is not seen as being on their list of high aspirational career pathways.

Throughout their career pathways, from education to the workplace, studies show different nuances to others’ attitude, ranging from attitudes of respect and open mindedness to gender equality, to more rudimental exclusionary attitudes. Recent studies reveal women have predominantly positive experiences in the industry, with those in professional roles characterising the industry as welcoming and having a sense of respect from male colleagues [47]. Tradeswomen also reported a moderately positive climate [18]. The predominant perception of a positive climate is also reflected in education environments [48].

Despite some noted advancements in the area of gender equality in construction, with many showing evident “personal investment in equal opportunity that genuinely welcomes it within most areas of the construction industry” [49] (p. 224), the potential for women’s empowerment on the grounds of common respect is to some extent deterred by a persisting underlying belief that women are not fit for the job [8,16,18,49]. Different derogative attitudes in the workplace arises from this view [8,18,51], such as assumptions that women are troublemakers, that they are not a worthwhile investment as they will eventually leave, female business owners viewed in a dismissive way, among others [18] that still diminish women’s presence and power in the industry [7]. Particularly the sanctioning of women’s capability is pervasive of women’s ability to work to their skills and to progress their career. Bryce et al. [54] report that 63.9% of participants felt the need to prove themselves more than their male co-workers, whereas men were assumed capable. This issue was repeatedly discussed in other studies regarding women in professional and trades roles, as a source of women being worn out, or even undermining their self-esteem [16,18,53]. For those more open to the capabilities of women in trades, there is a filtering that certain trades are inappropriate for women [49], and attitude which is, however, “based on a limited notion of equal opportunity”, because women are welcomed “as long as they remain on the margins” (p. 223). Even those women who showcase proactivity as a way to advance their career, are not always welcomed in the industry [7,8]. Such frictions between internal and external factors have a toll on women’s wellbeing and confidence in the long run, causing them to lose interest in the industry [49].

It is also found that women’s ranking to leadership roles are rather occasional, and thus illustrative of men’s attitudes towards gender capability in construction. Lingard and Lin [52] discuss that promotion due to leadership potential is sanctioned by some employers. Women who asserted themselves as managers, such as men do, were reported as being routinely sanctioned or pulled into line “for getting ahead of themselves” [16]. Those who achieve leadership roles experience limited acceptance and questioning of orders [16].

Another component of the middle ground attitude and behaviour towards women in the construction industry emerges from a lack of ownership of or responsibility for the gender problem [18,51]. Galea et al. [8,16] discussed how this leads to a sense of obligation to having more women in the industry rather than recognising that it as a larger issue [8] (p. 380). From the lack of recognition, appropriate measures or support to approach stances of behavioural conflict are not implemented, and thus, there is the perpetuation of inappropriate attitudes on the other extreme of the spectrum, including everything from smart jokes to verbal aggression, dismissiveness, humiliation and disrespect, exclusion, as well as sexual harassment and violence. These have been discussed in extent in Holdsworth et al. [18].

3.3.2. Support

The support factor of empowerment has also been discussed extensively in the literature, at the different stages of women’s involvement in the industry. There are ongoing needs of providing more information for parents to be able to be more assertive and encouraging in their daughters’ involvement in construction [48]; with attention to how such information has a realistic connotation than politically correct [49]. Despite efforts, participants in Holdsworth et al. [18] research talked about mixed experience with teachers’ support; while some teachers were active in reprehending inappropriate behaviour from other male students, others were less supportive, ignoring female students’ complaints, showcasing actions based on assumptions or protectionism, while perpetuating problems with gender discrimination in the industry.

Women’s stories when entering the industry tells of a narrowing pathway, when there is decreasing support from within the industry. From the beginning, female students talked about the need for greater support in finding traineeship [46,48], and transition from apprenticeship to securing a permanent job is also difficult depending on employment models [18]. Many female in trades and construction professions see themselves as “lucky” when retaining permanency, in opposition to their male peers, who rather benefit from closer networking.

The literature also discusses of a prolific lack of organisations’ support for training and career progression [8,18,48,52]. 81% of participants in Baker and French’s [55] research state that organisations expect individuals to take responsibility for their career development. While this is a fact for both men and women, the impact on women seems more significant. This correlates with other studies, which result in lower organisational commitment from women and a tendency to inter-organisation mobility [7,52]. Sunindijo and Kamardeen [19] found that less supportive organisational climate led to poor relationships with their supervisors, creating a vicious downwards cycle. To many women in construction, there is a sense of being in the boys’ club, as selection and career progression are based on relationships and professional networks [8,16,18,53]. Formal and informal networks and sponsorships to career progression is enabling for men, who are aware and “routinely negotiate their power networks” for opportunities [8] (p. 22), while women cannot gain the same benefit from these networks, 60% of participants in Baker and French’s [55] research felt excluded from what Galea et al. refer to as “power networks” [8], or informal referral systems [16]. Other studies highlight the same problem [18], leading to the conclusion that although instrumental networks are significant to career advancement, they are of limited impact to women [7].

The presence of mentors is highlighted as motivational to encourage professional growth, however its effectiveness is affected by gendered issues. First, 56.9% of women participating in Bryce et al. [54] study disagreed with the presence of a role model or mentor in the study. Francis [7] and Rosa et al. [53] also show that mentor support is, oddly, poorly ranked by female participants. Francis [7] suggests an emphasis on the value of mentoring to career support rather than based on empirical evidence, while mentors not necessarily support career advancement, but rather retention of women in the industry. Nonetheless, mentorship programs are still suggested as effective strategies for women in both professional [8,52,53] and trades work [46]. Indeed, Holdsworth et al. [18] highlight the importance of mentorship, and more so of female mentors.

This is particularly relevant in the support of women’s wellbeing considering the inappropriate behavioural problems they experience. In that area, participants in the Holdsworth et al. [18] study report on the dismissal or discredit of tradeswomen’s complaints about behavioural issues, whereas men seem to be protected by their own on-site empowering network. Additionally, 60% of participants experienced lack of support from co-workers, supervisors or teachers, organisations and representatives of worker rights and wellbeing [18]. The lack of support or sanction of inadequate behaviour by supervisors and external organisations leave women in a vulnerable position, especially the new and junior workers with little on-site power [18].

Holdsworth et al. [18] show that women tend to seek alternative forms of support. Participants placed emphasis on the importance of supportive co-workers and the sense of being part of a team, which seem to dilute prejudice as others see their acceptance [18]. Family and friendship networks further allowed women to “ignore the noise” and “spend time with people who care” [18] (p. 74). The clear sense of empowerment received from other women was highlighted [18]. Women in trades developed groups and networks to connect with other women.

3.3.3. Participation

It was in this connection with other women in independent networks that the support factors intersect with more active stances of participation or engagement. There was only one mention regarding participation in the revised literature. In Holdsworth et al. [18] (p. 85), the discussion on support gains a different tone, about how “membership and engagement with these groups connected the participant with other women working in trades and enabled them to share experiences, seek feedback and advice, as well as give back to the industry by helping others”, while also overcoming the sense of isolation in the industry. It is evident in the comments by participants that the active engagement in women’s network for trades, sharing of experiences, knowledge and advice, and the sense of contribution is effectively empowering to women in construction, although of limited attention in the literature.

3.4. Relational: Power Over

3.4.1. Control

Factors related to the concept of “power over” were not referenced significantly in the literature, with greater attention given to leadership, and isolated comments under the other factors of commitment and challenge and control. Nonetheless, Holdsworth et al. [18] identified two control factors that can increase women’s power over their social environments. First, women reported on sense of responsibility of being the only female in a team and establishing a good reputation for others to follow. Another participant also discussed her commitment to lead by example and “very slowly and tactfully changing the way men perceive me or women in general… reprogramming the way men think” (p. 59). Other subtle strategies adopted by women in taking greater control over behavioural patterns are through “ignoring”, “acting professionally” and “establishing behavioural boundaries” by “holding your ground” (p. 70). In these comments, there is a subtle and active stance of control over behaviour and change to power dynamics at the individual level. In contrast, inappropriate behaviour from other women is seen as perpetuating stereotypes, making it “harder for the rest of us [women] who do an incredibly good job to garner any respect” (pp. 59–60).

Second, to further challenge power patterns, it is important for male co-workers to more directly “challenge” and “stand up” for what is right, taking control of “the power that men have on-site over women” (p. 67). This is a form of support, but in a stance of control and power ‘over’, rather than ‘with’. Female participants discussed the frustration they feel about unchallenged inappropriate behaviour, which is explained as coming from a place of fear of showing weakness of being “excluded from “in” the group” (p. 69). Another way of reading the limited stance of challenge from other males to the gendered power relation is the potential lack of commitment to gender equality.

3.4.2. Commitment

Commitment to change comes from the recognition of and responsibility for the problem of gender equality in construction. The concept of commitment was of attention in Lingard and Lin [52] but was applied to understand influences to women’s level of organisational commitment. It would be also helpful to understand what influences commitment to gender equality. Participants in Salignac et al. [56] indicate that a greater appreciation for the cause is backed by justifications, making sense of it from a social and business perspective. Differently, however, Galea et al. [16] show that men tend to associate gender issues with being a women’s problem rather than taking responsibility for this power imbalance in construction, limiting the implementation of effective initiatives. Another contributor to commitment is empathy. Participants in Holdsworth et al. [18] discuss that the awareness of unchanged gendered issues in the industry, together with “the desire to enable others who felt isolated in their work to connect” (p. 84), triggered the decision to start informal networks, which eventually developed into more formal supportive organisations.

3.4.3. Leadership

Of the three factors under the dimension of relational power over, there is a consensus that leadership is fundamental in triggering changes to gendered power dynamics in construction: “if a change in culture is to continue to evolve to ensure equality for all women, senior management and leadership in all organisations within the industry must be proactive and accountable in demonstrating and guiding what is acceptable” [18] (p. 102). Other studies also point to the fundamental role of leadership [7,47,51,55]. They hold that leaders are not defined by the ones on the top, but those who are proactive in making changes [56]. However, research shows that such leadership role and cascading process is still very weak [56], which is evident through issues of “lack of accountability and duty of care” and a “demonstrable failure of moral will” to punish inappropriate or illegal behaviour from those in power [18] (p. 104). A step forward is that those in operational roles with power and status (company and project leaders) need to ‘own’ and take responsibility for gender equality [8]; thus, showing genuine commitment.

There is the question of whether women in leadership roles have a more significant impact. Findings from many of the studies demonstrate that this would be the case [7,18,51]. Salignac et al. [56] point out that, overall, participants in their research have shown an inherent concern for gender equality; however, the awareness and urgency to change is different for male and female leaders, with the later showing greater understanding and promptness to act. Therefore, there is a need to have more women in top leadership roles [56]. Nonetheless, Holdsworth et al. [18] point out that women in leadership is not a guarantee of changes, and there are cases where women in leading roles, within educational and industry environments, have assumed stances mirroring the predominant culture of the industry.

3.5. Environmental

3.5.1. Organisational Practice

The environmental factors of (dis)empowerment have been largely debated in the literature, with attention to how these overrule and define barriers to personal and relational empowerment. The factor of organisational practice is frequently mentioned in being limitative to the attraction, retention and progress of women in construction. It includes rigid workplace practices of devotion to long-hours and inflexibility to alternative work arrangements. It also includes unequal processes of appointment and promotion, all of which, while detrimental to both genders, tend to be of greater disadvantage to women.

Workplace practice of long hours, presenteeism, and indeed devotion to the work is a significant issue in the industry [55]. Most of the participants in Bryce et al. [54] study reported working overtime, mostly 55–65 hours per week. Commitment to long working hours is highlighted in the literature as one of the biggest issues with work practice in construction [8,54]. It affects women differently than men, with the former experiencing a greater compromise of work–life balance [8,16], and career and family choice [8,16,18,50,53,54,56]. A total of 71.8% of participants in Bryce et al.’s [54] study agreed that starting a family is an impediment to their career and has a significant impact on women’s mental health and wellbeing [52]. Rigid work practices are the cause of stress and mental health problems in both men and women, generating a high degree of anxiety, acute stress, and depression [19]. In general, construction work practices are being fundamentally questioned; however, flexible work initiatives have not been incorporated as practice, and are dependent on individuals’ strategic relationships [8].

The impact that the above rigid work conditions have to the retention of women in construction also arises from the fact that commitment is balanced by fairness [52]. Recruitment and promotion are discussed as not based on capacity but assumption of capacity and the power of informal network [16]. The reported commonly biased recruitment and promotional processes make it more difficult for women to follow and progress in their passion for a career in construction. From a managerial perspective, some of the participants in Galea et al. [16] study describes that the pressure to contract more women makes it an obligation, and it should be based in merit. Franci’s [7] study showed a correlation between a decrease in career aspiration with increased exposure to the construction industry. Indeed, participants in Galea et al. [16] study reflected that “the pressure and time you’d need to give to the company” do not inspire women to obtain managerial roles (pp. 1222–1223), highlighting the environmental impacts in redefining personal interests.

Workplace hierarchy, “systems in which individuals in an organisation are ranked according to their relative status and authority”, is another aspect of organisational practice adding to or heightening gender issues [18] (p. 93). Women are usually stereotyped with roles and trades of lower value in the chain. However, change and growth in hierarchy can happen when women’s skills and aptitude are demonstrated, as well as strong work ethics and to be able to work with their male counterparts [18]. Nonetheless, paternalistic character of such hierarchy is evident by the limited numbers of women sitting at the top [56,57]. Not only that, but of the multitude of sub-contractors and organisations involved in construction project work, hierarchical dynamics become even more complex, within which gendered issues become difficult to be reported, approached and resolved [18].

3.5.2. Policies and Regulations

There are other forms of exclusion (e.g., lack of appropriate facilities and types of PPE for women) in the construction workplace practice in Australia [8,18,46,52]. These practices and systems that permeate the construction industry in Australia exist due to the failure of established policies and regulations [16,55,56,58].

Galea et al. [51] argue that equally important to policies are companies’ stated values, and the alignment of both is a form of “policy robustness”. This is because the values of the company are explained as its DNA and therefore of greater impact in guiding actions. The mixed messages between policy and company value becomes an impediment to policy implementation [51]. Women continue to experience issues with reporting on psychological safety climate, despite organisations and regulations in place [18]. French and Strachan [58] show that a limited number of more successful organisations in their gender equality policy took a rather active approach to policy, assigning responsibilities, setting specific targets, and establishing a clear implementation strategy, also discussed in Galea et al. [8]. This, to some extent, also points to the presence of leadership and commitment to overcoming gender issues in construction.

3.5.3. Culture

Culture is defined by a predominant value system, both feeding and fed by tendentious behaviour and attitudes, which then becomes endemic and, therefore, characteristic to the industry. It is a consensus among the studies that the construction industry is defined by a culture of masculinity, validated by the physical demands of the work, the use of heavy tools, and the tough environment of sites, among other features [16,18,49,50]. The culture of the industry influences organisations’ practice. While regulations and policies can quickly change an organisations’ practice, they may play a very small role in changing the culture. The concept of masculinity is not negative or demoralising of the industry. However, an excessive sense of masculine empowerment imbues individuals and groups with extreme sexism, aggression, and heightened competitiveness, leading them to diminish or overpower the opposite sex and question their capabilities for the work.

The potential positivity for women fitting into the construction industry is conditioned by other subcultures of heightened masculinity. The culture of presenteeism, enacted upon by practices of shaming [54], while detrimental to both women and men’s wellbeing, becomes an issue of women’s retention due to motherhood and needed work–life balance [8]. The culture of silence perpetuates unacceptable forms of overpowering behaviour by others not calling it out lack of accountability [18]. There is also the “subtle” culture of denial and resistance to gender equality hidden in construction companies affecting the successful implementation of policy [8]. The superficial incorporation of policies and strategies for gender equality create other unintended difficulties for women. As Pringle and Winning [49] have asserted, the challenge women face to work in construction “has less to do with negotiating a hostile culture than with the ways they are positioned in a relatively friendly culture” (p. 5). There is an inherent and less evident cultural resistance to gender equality in the construction industry, creating unbalanced power dynamics.

Francis’ study found a positive correlation between women’s career advancement and women’s presence in Australian companies, “indicating the less masculine the company, the more women advance” [7] (p. 269). However, this is still of minor influence in changing the culture of the industry, as numbers are still minimal, especially in managerial roles [54,56,57]. Women are prevented from “ownership” of the workplace and “relegated to the margins” [49] (p. 227). As Oo et al. [47] highlight, the industry’s culture is indeed perceived as one of the greatest barriers to women’s presence in the construction industry. There is, in this, a vicious cycle where the rotation is defined by a masculine culture, and the potential change through women accessing levels of power is subtly denied. Therefore, as Pringle and Winning [59] suggest, “a key question is whether men will be able to let go of forms of masculinity based on their celebration of strength and toughness and denial of women’s competencies”. It might involve a larger reappraisal of the gender issue, celebrating diversity, and indeed a review of power dynamics.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper presents the findings from the systematic and thematic analysis of the literature on women in the Australian construction industry using a women’s empowerment framework. The intention was to shed a different light to an issue which has been of lengthy concern and has remained largely unresolved. The reinterpretation of findings and discussions from the empowerment framework highlight important factors in the processes of changing the power dynamics of women in construction. Integrating findings related to some factors under the same empowerment dimension, seven key points are identified and summarized below as major conclusions from this study. It is worth mentioning that although these seven key points are discussed under the three dimensions (personal, relational and environmental), some of them are interlinked and can be referred to from more than one dimension. These conclusions are also made in terms of the way forward to empower women and address the long-standing gender issue in construction.

4.1. Personal Dimension

In general, personal factors are highlighted by Francis [7] and Rosa et al. [53] as determinants of women’s career success and advancement in the construction industry. Oo et al. [47] also asserted that while the industry’s culture has an impact on women’s decision to leave the industry, personal factors are determinants. However, the analysis of the literature shows that this is the least researched area, revealing an important research gap. The following three conclusions from the personal dimension of the empowerment framework are identified to empower women.

Conclusion 1: Focus on the pleasures of work and resilience building.

The findings in this research indicate that there are some differences as to what drives women to undertake a career in trades (interest and passion) and professional roles in construction (salary, skills, family, interest) [46,48,50], and that a career even in professional role remains stigmatised by many high school girls. For those who decide to undertake a career in the industry, a stance of proactivity and assertion to take such still unusual paths are important positions of inner strength, also defining their retention and career progression [4,7,8,46,49]. The most recent study by Turner et al. [60] indicates women who are successful in construction had high levels of resilience despite little to no support from their workplace. Many other studies highlighted that attitude and behavioural stances of focusing on the job and the pleasure of work, rather than gendered issues, help emancipate women from gender norms, becoming an empowering characteristic from within, for women’s success in the industry [8,46,49,50,53]. An international study [59] also pointed out the importance of running self-esteem workshops for women to learn to face and handle conflicts in predominantly male workspaces, so an overall work enjoyment can be better achieved. In fact, a study in Sweden reported that women in construction have learnt that they need to “be able to either laugh at or ignore some of the jokes that men may tell at work” [61] (p. 5) and they become “less sensitive to male dominance and discrimination” [61] (p. 5).

Conclusion 2: Capacity building based on skill and knowledge.

In addition to the above, skills acquired through different forms of social capital, awareness of possibilities and challenges of the industry, as well as a sense of autonomy that builds from that, allow women to navigate their way through career development. While the previous item indicates the importance of “emotional empowerment”, this item highlights the equal importance of capacity building based on skill and knowledge for women to develop a successful career in construction.

Technology advancement and wider adoption of construction machineries and digital tools provide a more equal opportunity to men and women as physical strength is much less required in construction, which means women can build the same capacity as men via intellectual means to adapt to the modern construction industry. Currently, no gender research in Australian construction industry has explored the opportunities and challenges that this new industry trend places on the gender issue. However, there are international studies [59,62] that pointed out that technology advancement and the recent Construction 4.0 could exacerbate current gender divisions and inequalities as maintaining technological skill levels in line with industry progress also presents challenges to women. Perrenoud et al. [22] study in the U.S. also found that men generally attended work-related training programs more often than women. Naoum et al.’s [63] survey in the UK indicated that both men and women think work training and outreach programs to schools are one of the most crucial initiatives to retain women in construction. Therefore, how to acquire, update and maintain new knowledge and skills are key to women’s capacity-building in the construction industry.

Technology advancement also brings changes on the industry’s culture, and its impact on women empowerment will be discussed in the environmental dimension.

Conclusion 3: Taking initiative to seek support.

Actively finding alternative strategies, including taking initiative to seek supportive networks, is help women to succeed in the construction industry. This conclusion is drawn in conjunction with the relational and environmental dimension discussed below, which indicates that the construction industry is becoming increasingly accepting and supportive of women [18]. Most of the international studies also reported that although the culture in construction is persistently male, a positive shift in attitudes and a supportive environment is taking place [58,61,62,63]. As such, women’s empowerment can be achieved by taking personal initiative to fully utilise the positive and supportive environment around them, while overcoming other long-standing relational and environmental barriers. Hegatty’s [58] investigation in New Zealand also pointed out that women should intentionally regulate their behaviours to successfully seize opportunities and manage social challenges in construction.

4.2. Relational Dimension

Relational factors of empowerment, and more so those that are built on ‘power with’, thus dependent on non-active external factors, such as others’ attitudes and behaviour and support, have been largely discussed in the literature. More active stances of participation, control and commitment are significantly overlooked in the literature. What are the views of those women who participate more actively in networks and groups? What are the perceived changes by those who take stances of even subtle control and how can that be reinforced? Is commitment to gender equality in the industry and by others in greater position of power lacking? The latter has been answered to some extent but nonetheless received limited attention despite its significance in enabling empowerment. Only a few references looked at leadership, especially when it relates to leadership at different levels of an organisation. In summary, further two key conclusions are made to empower women from the relational dimension of the empowerment framework.

Conclusion 4: Explicit recognition and awards, and establishment of leadership role model.

Others’ attitudes towards women in construction influence women’s decisions to take on a career in the industry (parental influence), their educational and workplace experience (peers and co-workers), and their retention and career progression (supervisors and managers). Although some recent literature reveals women generally have positive experiences with male colleagues [18,47], throughout women’s different career development phases, both in professional roles and in trades, but more so in the latter, there seems to be a persisting attitude of discrimination. The potential for women’s empowerment in the grounds of common respect is to some extent deterred by a persisting underlying belief that women are not fit for the job [8,16,18,49]. Very often, having more women in the industry is a sense of obligation, rather than being recognised as a larger issue [51]. In a most recent Australian study [63] and an international study [64], countering negative stereotypes is identified as an important aspect of increasing women’s recruitment. Women’s empowerment, in this regard, can be enhanced by explicit recognition, appropriate measures to award women’s achievement in the industry to change other’s attitudes.

This is also closely related to the “power over” factor of leadership. Women’s rather occasional leadership opportunity is illustrative of men’s attitudes towards gender capability in construction. Leadership plays a significant role in triggering changes. Given its fundamental importance, as a way through which different attitudes can be role modelled, it is an area deserving greater attention, particularly in the identified lack of commitment or accountability from those in at the top. Researchers in New Zealand [59] also showed that women in construction are motivated to seek opportunities to move into leadership roles, and employers should provide greater social support for women working in the industry. In another regard, for those leaders throughout different levels of an organization, it could be suggested that the tipping point in such power imbalance lies not only in changing others’ attitudes but one within women themselves, to shift others’ views and ingrained values, taking ‘subtle’ control over gendered relations.

Conclusion 5: Active participation in women’s network and support from other women.

The support factor of empowerment was discussed extensively in the literature. While girls receive great encouragement and support to take construction courses, decreasing support and narrowing pathway are reported after they enter the industry. Clearly there is a lack of support for training and career progression, and the sense of being in the boys’ club causing much less and weak professional network for women which is usually important to career progression.

It is found that the sense of empowerment can be obtained from groups and networks developed with other women [18]. This is consistent with Perrenoud et al.’s [22] study in the U.S., which reported that women rated relationships with coworkers as a more positive influence on retaining them in the industry compared to men. Participation factor is bought in, linking with the support factor—women can be empowered by actively participate in women’s own network in the industry. Women’s support to each other, both for their wellbeing and for career advancement, the sharing of experiences and knowledge, can greatly empower themselves.

This conclusion is also consistent with Point 3 above from the personal dimension.

4.3. Environmental Dimension

As mentioned previously, the environmental dimension of the empowerment framework has been researched and reported most frequently in the literature—in the context of all its three factors of culture, organisational practice, and policies and regulations. The construction industry is infamous for its long working hours, inflexibility to alternative work arrangements and high pressure. While this is detrimental to both genders, it tends to be of greater disadvantage to women. Gender equality policies and regulations are widely established in the Australian construction industry. However, there is a subtle culture of denial and resistance to gender equality affecting the successful implementation of policies and regulations [8]. Based on these commonly agreed facts, two key points are identified to empower women from the environmental dimension of the empowerment framework.

Conclusion 6: Take advantages of the culture change caused by technology advancement.

While the rigid work culture and condition of the construction industry is hard to change, recent developments in technology do provide more opportunities for more flexible work patterns, e.g., remote monitoring of the construction site, utilising more automated construction machineries, etc. This aspect has been largely ignored by the existing research on gender equality in Australia, but has been reported in other international literature related to gender issues in construction [3,58] Even if men try not to let go of masculinity in their dominance of the construction industry, technology advancement will force them to accept the fact that much less physical and masculine work is required in the industry. The technology-induced game-changing environment benefits both men and women. However, women will gain more power from it, which will lead to a more balanced power dynamics in the construction industry.

Conclusion 7: More active approach in policy implementation.

Despite the well-established gender equality policies and regulations, there is, however, still a significant percentage of women who had negative experience on extreme levels. In terms of policy implementation, according to French and Strachan [58] and Galea et al. [8], limited number of organisations have been more successful in their gender equality policy as they take an active approach by assigning responsibilities and setting specific targets. This should be more widely adopted to ensure a positive environment for women’s empowerment in the construction industry. International studies in other countries such as New Zealand [58] and the U.S [62] also drew similar conclusions, emphasising the importance of employers to sustain a diverse workforce by consistently implementing gender-related policies.

While factors under the environmental dimension have been exhaustively studied in the revised references, it is in the realm of the interface of this dimension with the other relational and personal dimensions that new strategies can be redefined to improve women’s empowerment in construction.

Overall, the above seven conclusions drawn from the personal, relational and environmental dimensions of women’s empowerment framework provided key areas for both the industry and women themselves to develop. The major contribution of this study is it goes beyond the usual gender research in construction on providing external support to women, and emphasises on empowering women themselves with the positive interaction with the external environment. The points raised have been significant areas of change to greater women’s empowerment in construction, which have been largely overlooked in previous research. Male-dominated industries such as construction have historically suffered from loss of talent by limiting the participation of minority groups in general. Take arts as an example, which was once a highly masculine terrain, in a time when much freedom was taken from women. A project by Jane Fortune, the founder of Advancing Women Artists (AWA), is uncovering many hidden and forgotten artwork by nuns and other women, showing much of the lost talent at the time of the Renaissance [64]. Much has changed since then, by women who felt strongly about practicing art, breaking social and cultural norms, which implied in the unveiling of so many female talents. A similar trend in the future is still to unveil for women in construction, through women’s own empowerment, and with lessons learned from other industries.

This paper is one of the pioneer studies in applying the empowerment framework to provide a solution to the long-standing research question on how to effectively attract and retain women in construction. The seven conclusions are drawn mainly based on relevant literature on the Australian construction industry. While some most recent international studies are examined to support and supplement the research findings, a more extensive and systematic study on international literature can be conducted, with categorisation of the countries’ economic, political and culture, to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the gender issue, and propose more practical solutions to empower women in construction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C.W., E.M. and R.Y.S.; Formal analysis, E.M.; Funding acquisition, C.C.W. and R.Y.S.; Investigation, C.C.W., E.M. and R.Y.S.; Methodology, C.C.W., E.M. and R.Y.S.; Project administration, C.C.W.; Resources, C.C.W. and R.Y.S.; Supervision, C.C.W. and R.Y.S.; Writing—original draft, E.M.; Writing—review and editing, C.C.W. and R.Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Chartered Institute of Buildings (CIOB) Australasia’s small research grant 2020–2021.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Australian Industry and Skills Committee. Industries/Construction. Overview. Resources/National Industry Insights Report. Available online: https://www.aisc.net.au/resources/national-industry-insights-report (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- The Government of Victoria. Safe and Strong: A Victorian Gender Equality Strategy. 2016. Available online: https://www.bing.com/search?q=victoria+state+government&form=ANNTH1&refig=252bffb335354f7a95908c41e58a5bb7&sp=1&qs=LS&pq=victoria+state+&sk=PRES1&sc=8-15&cvid=252bffb335354f7a95908c41e58a5bb7 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Wright, T. Gender and Sexuality in Male-Dominated Occupations: Women Working in Construction and Transport; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Carnemolla, P. Girls’ Perception of the Construction Industry” Building a Picture of Who Isn’t Interested in a Career in Construction and Why. NAWIC IWD Scholarship Report 2019. Available online: https://www.nawic.com.au/NAWIC/Documents/Philippa_doc.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- Dainty, A.R.; Lingard, H. Indirect discrimination in construction organizations and the impact on women’s careers. J. Manag. Eng. 2006, 22, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielden, S.L.; Davidson, M.J.; Gale, A.W.; Davey, C.L. Women in construction: The untapped resource. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2000, 18, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, V. What influences professional women’s career advancement in construction? Constr. Manag. Econ. 2017, 35, 254–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, N.; Powell, A.; Loosemore, M.; Chappell, L. Demolishing Gender Structures; UNSW: Sydney, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, A.W. Women in non-traditional occupations. Women Manag. Rev. 1994, 9, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, D.; Wulff, E.; Bamberry, L.; Krivokapic-Skoko, B.; Jenkins, S. Negotiating gender in the male-dominated skilled trades: A systematic literature review. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2020, 38, 894–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.; Barnard, A. The experience of women in male-dominated occupations: A constructivist grounded theory inquiry. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2013, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Menches, C.L.; Abraham, D.M. Women in construction—Tapping the untapped resource to meet future demands. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2007, 133, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morello, A.; Issa, R.R.; Franz, B. Exploratory study of recruitment and retention of women in the construction industry. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2018, 112, 04018001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsdotter, G.; Randevåg, L. Doing masculinities in construction project management. Gend. Manag. 2016, 31, 134–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrall, L. Organizational cultures: Obstacles to women in the UK construction industry. J. Psychol. Issues Organ. Cult. 2012, 2, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]