1. Introduction: Results of the Analysis of Currently Available Housing Forms for Seniors in Poland

Poland is still in the group of countries where the ratio of the 65+ seniors to the overall working population is relatively low from a European perspective (46.3%, whereas the average European ratio is 53.9%, data as at 2017). Nevertheless, radical decisions need to be made today in a variety of areas to better prepare for the unavoidable consequences of the demographic changes [

1]. According to analysts, well-designed housing not only supports sustainable development and stimulates good citizenship but also is able to generate social, economic and environmental benefits [

2]. The price of a good design package is low—roughly 1% of the costs generated during the lifetime of the building. Yet, it may have an enormous impact on the lives of the residents, owners and the whole community [

3].

Despite the fact that the economic costs of the ageing society are at present at a low ratio level [

1], the situation may soon change dynamically. As follows from the population data of the Central Statistical Office (GUS), in 2000, seniors (women aged 60+ and men aged 65+) represented 23% of the population of Poland. According to the forecasts, this percentage will increase to 37% in 2050 (

Figure 1). Demographic changes are an indisputable fact. The percentage of elderly over 80 is around 4.2% in Poland (the European average is 5.5%) and is going up. Thus, the number of seniors is and will be increasing. A longer lifespan, however, does not equate to longer physical or mental fitness. According to the OECD data of 2017, after reaching the age of 65, an average Pole enjoys good health only for 8 years [

4]. In the early 1950s, the average human life expectancy was 47 years. At present it is over 65 years. In 2050, human life will last an average of 75 years. In 1950, approximately 200 million people aged 60 and over lived in the world. There are over 500 million of them at present, and estimates say there will be 1.2 billion by 2025. The prospect of such a large increase in the population of elderly people must arouse in those responsible for the functioning of societies the need to prepare for this phenomenon (Aging of Polish society and its effects, Bureau of Analysis and Documentation, Team of Analysis and Thematic Studies, Publishing House of the Chancellery of the Senate, Warsaw 2011). At the moment, when designing solutions for people with special needs, seniors in particular, one should take into account the features and predispositions of those who are young at present, but who will soon get old, proposing modern design solutions for the “future self”. Nowadays, the use of technology (Internet, computers and mobile phones) is becoming increasingly common, so the aspect of cyber exclusion, so characteristic of aging societies, will soon disappear among seniors in the near future. Hence, new technologies should be more often used in designing accessibility for seniors. The currently functioning solutions are very fragmented, dedicated to specific dysfunctions and not covering a design based on the philosophy of the products and the surroundings; thus, one needs products that serve a broad spectrum of recipients, both now and in the future, without the need for further adaptations, redesigning or adjusting to changing conditions. A multi-functionality approach to find solutions, integrating various problems at the stage of designing, is an innovative way that, in addition to an innovative look at the process itself, will result in the future in translating into specific economic dimensions for further investments, allowing for a quick, standardized audit of public space to allow introducing the ready-made, modular solutions.

Therefore, it can be easily assumed that, on average, any Polish citizen aged 73 has to deal with some health issues and needs assistance. The needs of the elderly are highly varied and depend on their physical and mental condition. New needs have been identified, including proper nutrition, regular physical exercises and regular screening examinations [

5]. Therefore, an appropriately organised healthcare system and an adequately designed and regular social education of the seniors and their family members are becoming more and more important. It is obvious that the need for accessibility and inclusion is a universal need, regardless of age. As the share of the 65+ age group in the overall population is increasing, more attention should be paid to their housing environment. Appropriately designed housing forms and spaces for seniors can effectively influence the quality of their lives and their feeling of safety. The results of research studies clearly indicate that a better quality of apartments leads to lower rates of hospitalisation, in addition to the obviously improved life standard. This has an economic impact on the whole society [

6].

The guidelines for designing inclusive spaces ought to be determined by a whole spectrum of the features of old age, including deteriorating perceptive and cognitive abilities, and worsening motor skills. Space may really support healthy ageing by helping the elderly compensate for their deteriorating physical and mental condition.

Persons with dysfunctions are excluded in spite of their actual potential. Disability can be understood as a deprivation of a person’s potential or ability to function because of space barriers and difficulties resulting from specific dysfunctions or from social limitations in a discriminatory or stigmatising environment [

7]. It is essential that social policy should emphasise the necessity of equal treatment of all citizens regardless of their disability, as well as the promotion of social and professional activities, and it should prohibit discrimination [

8]. The design of space is just as important: the space around us ought to be designed so as to offer every person equal opportunities of development and give them a chance to be self-sufficient in their daily activities.

In Poland there are several institutional and non-institutional forms of housing (

Figure 2). At present, the most popular housing option among the elderly and their families that for various reasons are unable to provide care for their elders is a State-Run Nursing Home (DPS) (most of such homes provide care for the elderly on a 24 h, 7 days a week basis, although there are also the community-based day care centres (DDPS)). The largest group that requires assisted living are the seniors and they represent a large majority of persons living in State-Run Nursing Homes [

8]. It must be remembered that the persons referred to the State-Run Nursing Homes require permanent care and assistance in daily activities but not medical treatment at a hospital department [

9,

10,

11]. Another important issue is the availability of nursing services and the condition of the infrastructure. Demand for nursing services in State-Run Nursing Homes substantially exceeds the supply. The majority of the nursing homes are situated in old buildings, originally built for a different function, and are now only adapted to the nursing function. The demand for nursing care is so high that in some big cities the seniors must wait even up to two years for admission to a State-Run Nursing Home [

12]. This leaves no doubt that new, efficient and durable solutions must be sought, not only to meet the current demand but also the forecasted demands and the needs of the seniors of the future.

An alternative solution offered is the so-called community-based care (SDPS). This solution consists of the provision of regular care services by a social worker, or if necessary, also the community nurse, in the place of residence of the elderly person. Community-based care is a good solution considering the fact that the senior can continue to enjoy living in his/her own apartment. This makes the seniors feel more independent. The fact that a senior may feel independent in his/her own flat is one of the key aspects of life satisfaction felt by the seniors, even if it might deviate significantly from the concept of independence from the perspective of a younger person. As quite rightly observed by Cieślak, Cielak and Bolz, “the scientific research and current trends in the elderly care indicate that the best way to ensure good health condition of the elderly is to ensure that they have the options of independent functioning in dignity” [

13]. It must, however, be remembered that in case of persons whose options for independent living are limited, this solution will not be fully sufficient because the visits by social workers are of limited duration and must be supplemented with care provided by family members.

Seniors who require permanent medical services and hospitalisation are admitted to their respective health care centres (ZOL), where, apart from assisted living services, they are also provided with medical treatment. As in the case of the State-Run Nursing Homes, organisation of the aforementioned healthcare centres is insufficient to satisfy the demand. The waiting list is very long, and patients are admitted to rooms that they must share even with as many as four other elderly people. Daily Healthcare Facilities (DDOM) are a fairly recent form of the institutional care system in Poland. Such facilities were first opened in Poland in 2016 within the framework of the pilot programme of the Ministry of Health [

14]. Owing to the programme, co-financed from the European Social Fund, 53 such facilities have been opened all over the country. The main task of such facilities is to provide post-hospitalisation care and rehabilitation to seniors over 65 and to educate the elderly and their family members on how to continue independent rehabilitation at home. Daily Healthcare Facilities (DDOM) are mainly dedicated to seniors who require temporary medical care, rehabilitation and continuation of treatment but not necessarily hospitalisation in hospitals or continuous care in healthcare centres (ZOLs). This form of elderly care has been designed to support the currently operating and highly volume-overloaded system, to take over some of its tasks and to facilitate the procedure of setting up new support centres. Daily Healthcare Facilities represent an intermediate stage of elderly care between community-based day care centres (DDPS) and health care centres (ZOLs). On the one hand, they provide daily therapy sessions (for a minimum of 8 h), and on the other hand, they are also provided with proper medical back-office facilities and can offer rehabilitation if needed. Regarding services, these facilities are fully equipped to ensure medical assistance, and in particular, there is always at least one physician, one nurse and one caregiver present. Daily Healthcare Facilities are also required to provide the assistance of physiotherapists and physicians of various specialities. Taking into account the fact that these facilities are planned to care for small groups of elders (10–15 persons), it should be stated that this form of institutional care is well-designed to properly address the current needs with regard to the national eldercare policy.

Moreover, it should be noted that the above-listed forms of institutional care (DPS, DDPS, community-based care services (SDPS), sheltered accommodation and Daily Healthcare Facilities (DDOM)) have their non-institutional equivalents (private eldercare provided by a wide range of entities). The non-institutional care varies depending on the scope of services or place and form of their provision; however, it is much more expensive.

Another solution dedicated to a similar target group (persons not requiring medical assistance on a daily basis but requiring assisted living) is the so-called sheltered accommodation [

15] (there are also sheltered training dwellings).

In accordance with the legal provisions, sheltered accommodation is dedicated to at least three persons of limited abilities to fulfil their daily care needs. Such accommodation comprises bedsits (single or double) and common areas (such as a kitchen, halls, toilet and bathroom). The apartment, adjusted with its dimensions to the needs of the disabled persons, shall also accommodate a caregiver, who assists the disabled with performing daily routine activities. The advantage of this solution is the comfort of living of the disabled as well as lower costs incurred by the municipality for the eldercare of this type, which is also easy to organise. In the apartment, the seniors may not only enjoy the benefits of assisted living, but they also have a chance of social interaction. Despite the fact that sheltered accommodation is a cost-saving solution, it is still rather rarely used. What is important here, is that sheltered accommodation is much more affordable than other options. Service and utility charges and costs of minor repairs borne by the residents of sheltered accommodation are much lower than the costs of the State-Run Nursing Home care; at the same time, it is much easier to organise assistance for the elderly, as the municipal authorities manage their own the social housing assets [

7].

Another form is the co-housing idea, i.e., apartments specially designed and adapted to the needs of the senior users and provided with a shared space. The target group this solution is addressed to is composed of seniors who do not need 24 h care but need to have easy access to medical and commercial services or to recreation and relaxation options. Apartments constructed under such co-housing schemes are designed to have all functional amenities required to ensure a safe and comfortable old age. The apartments’ dimensions, their locations and quick access to medical services facilitate and extend the relatively independent living of the elderly. In particular, functional adaptation entails a well-functioning local community, which can ensure the feeling of support to the seniors. The so-described policy not only contributes to the improvement of the life comfort of the seniors but will also constitute a relief for other forms of elderly care.

2. Methodology

Based on an analysis of the current system of elderly care and the forecasted increase in demand for senior housing options that can support the independent living and well-being of seniors, a diagnostic poll was conducted to identify the expectations and the awareness of the preferable housing forms for the seniors of the future. The poll “Housing expectations of the future seniors on the basis of the example of the inhabitants of Poland” was conducted in 2020. A total of 674 respondents took part in this online opinion poll (

Figure 3). The criteria concerning age and education were uniform for the entire group of respondents. The expectations of young people aged 18 to 24, currently studying in Poznań, were researched with the use of this poll method. The group size of female respondents was almost identical to the size of the male respondents’ group (333—women, 341—men). The poll was organised to gain a general assessment of the housing forms for the elderly, to develop a detailed diagnosis of the preferred characteristics of the housing facilities, and thus to create (to the highest possible degree of precision) a model place for the elderly that would ensure them optimum living conditions. Furthermore, the poll aimed to survey the young people of today regarding their preferred housing for the future, when they are at an old age. The poll was divided into three topic sections.

Within the first section, the respondents were asked to grade from 1 to 5 (1 being the lowest grade, 5 being the highest grade) the various forms of eldercare currently available in their place of residence. The poll listed the following forms of eldercare to be assessed by the respondents: State-Run Nursing Home (DPS), community-based day care centres (DDPS), Daily Healthcare Facilities (DDOM), private caregiver in the place of residence, co-housing for the elderly and own apartment in the previous place of residence.

The second section was designed to assess to what degree the respondents were ready (or were not ready at all) to select a particular form of housing for the elderly in the future.

In the last section, the respondents were asked to assess the importance of relevant amenities in their place of residence in view of being the seniors of the future; e.g., a living space adapted to the needs of the disabled, a registered nurse on call 24 h a day, 7 days a week (with Nurse Next Door), 24 h online medical consultations and 24 h online consultations with a psychologist. The respondents could also choose the services that they deemed essential near their place of residence—e.g., a pharmacy, a grocer, a bank, etc.—and assess the importance of access to recreation and sports areas and to the Internet.

3. Results

In the first section of the poll, the respondents were to grade from 1 to 5 the housing forms for the elderly available in Poland (

Figure 4). The options “private caregiver in the place of residence” and “own apartment in the previous place of residence” scored the highest grades (total average 4.06). This only confirms strong “ageing in place” preferences and the willingness to live in one’s own apartment for as long as possible. The typical forms of institutional eldercare scored the lowest grade, i.e., “State-Run Nursing Home (DPS)” and “community-based day care centres (DDPS)” (total average below 3). Such results are to a large extent justified by the negative image of institutional forms of eldercare in the public awareness in Poland. The assessment results show a correlation with the respondents’ gender in view of the preferred form of the housing for seniors. It has been found that men generally assigned lower grades to institutional forms of eldercare than women. The largest opinion difference was observed in the assessment of the co-housing option for the elderly. Female respondents graded it much higher than men. This may be explained by anthropological differences between the sexes, where men wish to dominate and have a strong need for autonomy, whereas women are more willing to make concessions and to live in a community [

16].

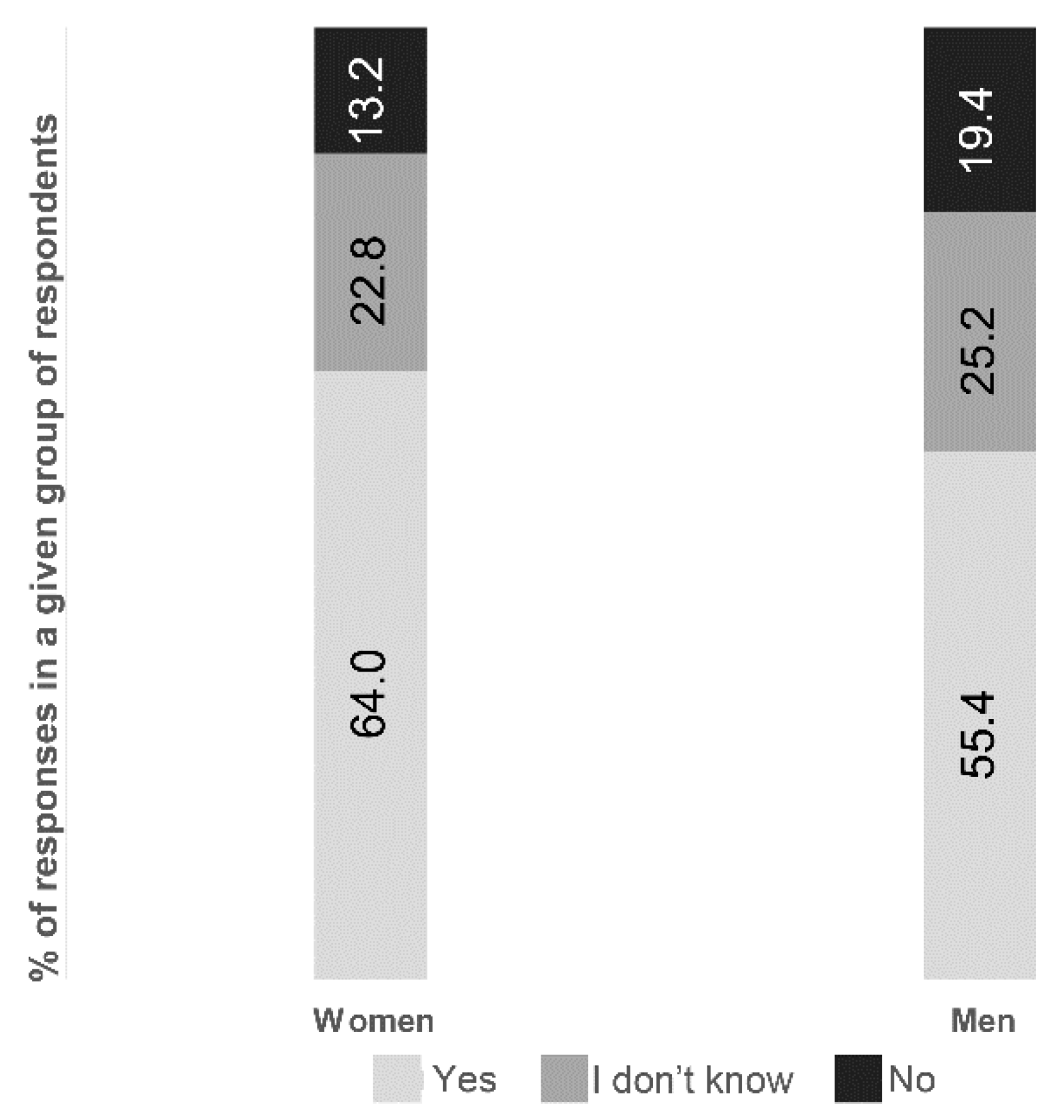

In the second part of the poll, the respondents declared whether in the future they would be interested in a given form of housing for the elderly (

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9). The majority of respondents declared that they would be considering the respective adaptation of their own apartment to the needs of the elderly or the option of living with family members. At the same time, the majority of the respondents clearly declared that they did not want to live in a State-Run Nursing Home or to attend a community-based day care centre.

The co-housing option received largely different scores, depending on the gender of the respondents. The gender-dependant assessment only confirms the already made observations that women are more open to this form of housing than men. It should be also noted that this form of housing for the seniors (co-housing) scored the highest number of “I do not know” responses. This may stem from poor recognition of this form of eldercare but also from the fact that young people do not think about their old age as yet and usually do not have any definite opinions regarding their future housing when they become old. The last part of the poll was dedicated to the evaluation of respective amenities for the seniors in their place of residence (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). Of all the possible amenities, “space adjusted to the needs of the disabled” received the highest score and was followed by the “accessibility of services” option. These results clearly show there is a strong social need to keep fit for as long as possible. The option of online medical consultations in the place of residence also scored a high grade (4—the best result). What is interesting, this option was rated higher by women than by men (average assessment of all the female respondents and all the male respondents aged from 18 to 24 was 4.01 and 3.71, respectively). The respondents also thought the following were the least important for them: “access to the Internet” and “online consultations with a psychologist” (the lowest score).

Having analysed the poll results per gender criterion, it may be noted that the amenities highly ranked by women are assessed much lower by men. Additionally, it is clear that certain options are better ranked the older the respondents become. The older we are, the higher we rate the respective options.

4. Discussion

In view of the rapid rate of ageing of societies in Europe and the necessity to provide these future seniors with housing options that would support their independent and unassisted living, it is important to study the housing expectations of today’s young adults. Based on the answers provided by the respondents, we have been able to reach several conclusions.

The results confirm that today’s young prefer those housing solutions that would enable them to keep living in their own apartment, despite their disabilities (the respondents generally declared that at an old age they wanted to share accommodation with their family members or to move to an apartment adapted to the needs of the disabled; a caregiver in the place of residence was also highly assessed). Furthermore, amenities such as “accessibility of services” or “recreation and relaxation space” ranked high, which means that, regardless of age and gender, we all wish to remain independent and active for as long as possible. These observations may, thus, constitute the grounds for the planning of housing standards (without any particular dedication to respective groups) in compliance with the principles of universal design, adapted to the needs of all the users, not only regarding the building plan itself but also with regard to the immediate vicinity. Application of the right standards shall definitely represent a competitive advantage of the housing constructed in compliance therewith.

It may be further concluded from the poll that there is a correlation between the senior housing preferences and gender. The research has shown that women assign more importance to living conditions and amenities. Therefore, the solutions proposed for seniors should mainly address the preferences of women and their needs, especially as their lifespan is longer. It follows from research that men much more often negatively assess the eldercare co-housing options than women.

It is estimated that in 2060, 33% of all Poles will reach the age of 60+. At the same time, it should be noted that the gender structure will be largely dominated by women, in particular at an advanced age; i.e., those over 85. Other countries, e.g., Great Britain, show a similar gender asymmetry in their social structure. It was in Great Britain where the demand for accommodation adapted to the needs of elderly women that lived alone underlined the conception of a co-housing option dedicated to women over 50, associated with the Older Women’s Co-Housing (OWCH) group. The complex contained 25 private apartments constructed on a T letter plan, around a common garden. The women took part in designing the natural features and layout of the complex arrangement, where the prevailing assumption was the plan of shared amenities fostering the feeling of community spirit.

The British studies show that co-housing is not a niche form of housing as may be inferred from its image, and co-habitation is not dedicated to niche users [

3]. Moreover, the studies clearly show that social isolation significantly contributes to the deterioration of health in senior groups and largely affects their well-being and quality of life [

17]. The co-housing accommodation option is a chance for the elderly to enjoy their old age in the company of other people and social inclusion.

Depending on age, the housing space is differently assessed. It may be stated that the older we are, the more importance we attach to the amenities proposed to us. This correlation may result either from a good health condition when we are young, or from the lack of awareness of the changes that await us when we are old and ignorance of the available options in response to such changes. Thus, the young generation should be properly educated and persuaded to participate in activities that they can share with the seniors.

5. Conclusions

At present, there is a range of various forms of housing dedicated to seniors that can be perceived as a response to the new and varied needs and preferences of the elderly of the future [

18]. Well-designed residential buildings should not only support sustainable development and civic participation but should also render social, economic and environmental benefits. They may represent a significant value for a country such as Poland, where institutional forms of eldercare are of low quality and rank low in social opinion polls. As per the data presented in the national report made in Great Britain [

19] on the challenges posed by the demographic changes, the low quality of housing for the elderly causes high costs for the National Health Service—2.5 billion pounds sterling a year. Housing improvement is viewed by the British as a chance for reducing medical service demand, and for creating conditions that might extend the working age of the seniors.

Despite the fact that new housing options are becoming available for seniors, nevertheless, the preference of ageing in place (one’s own apartment) continues to prevail. The results of similar studies made in Poland and abroad confirm the above tendency. The studies made by Dudek-Mańkowska unambiguously indicate that for many people, the chance to live in the safety of their own home is a top priority; for that reason, the state authorities in Poland should concentrate on such modification of their physical environment so it would be friendlier and more responsive to the ageing process and, at the same time, improve the access of the elderly to alternative forms of transport, make available medical services that are provided in the place of residence and ensure availability of online shopping deliveries or home deliveries of medicines. The costs of hospitalisation keep rising. Globally, the highest costs of hospitalisation are generated by patients aged 65 plus (some 40%), followed by patients aged from 45 to 64 (27%) and those aged between 20 and 44 (20%). Less than (10%) of the cost is generated by patients aged 20 and less [

20]. Based on the prevailing trend of ageing societies, the costs of healthcare are expected to keep growing steadily, simply because the chances that a person will have to go to hospital grow higher with the person’s age. Taking into account the growing scale of healthcare requirements and expenses, the current systemic solutions ought to be verified: they ought to focus more on prophylaxis and on counteracting disability and diseases.

It is essential to use new, innovative technologies in designing space for the elderly. When discussing how to adapt spaces to facilitate good health condition for its users, and taking into account the rate of ageing, we ought to have a closer look at the different characteristics of the new seniors, especially their new abilities—in particular those connected with advanced information technology. A comparison of the commonness of the skills to use information technology showed that the elderly remains far behind the younger members of society. On the other hand, incredible changes have been observed in that age group for some years. In a 2018 Deloitte study in the USA, a sample of 4530 adult Americans were studied to diagnose their adaptive abilities to use advanced telemedicine technology for treatment and rehabilitation purposes (“Consumers are on board with virtual health options. Can the health care system deliver?”). The participants were divided into age groups because age is a significant factor affecting the use of new technologies. They found: “In the senior population, the year-to-year percentage of computer users has been growing: during the last 3 months of 2018, 31.7% of people aged 65–74 were able to use a computer, which means an increase by 2.5 pp a year. Although a growing number of people in that age group is using a computer on a regular basis (i.e., at least once a week), the percentage of regular computer users among that age group is lower than that among the younger participants. In 2018, one-third of the participants aged 65–74 used the Internet and 29.8% of such participants did so on a regular basis”. Both the results of the Deloitte study and information from the Central Statistical Office in Poland (GUS) indicate that the society of the near future will generally be an information society. This means that the ability to use mobile devices, to get access to the Internet or use information will be common spread also in the 65+ age group. Most probably, the aspect of cyber exclusion will be statistically insignificant. Therefore, the assumption that new e-technologies will be used on a common basis in the future ought to be incorporated into the architectural design of spaces for the new seniors. In particular, it ought to be envisaged in designs of healthcare spaces for the growing ageing societies because, by that time, the current access limitations will have ceased to matter at all [

21].

It is important to educate, in the next years, not only the young people but the society in general about the consequences of global ageing, which require an update of the forecasted needs of seniors in the future, with regard to both their type and volume. Architects and urban planners shall be jointly responsible with other professional groups for developing new solutions to the problem. This process may be effectively facilitated with high social awareness and participation.

The constantly changing offer of newer and newer housing options must be well-adjusted to the cultural, social and economic conditions. It is, thus, fully substantiated to currently analyse the housing needs of the seniors of the future in order to be able to accurately define the needs of the ageing generations and to develop solutions that shall ensure them the comfort and safety of ageing in place (of residence).

Moreover, the aging of societies poses new challenges for the assessment of factors determining the quality of life in cities [

22,

23,

24].

Research indicates many other aspects that are crucial for the quality of life of seniors in cities. In the literature, the following are mentioned: “Functional and social mix, space flexibility, green design, renewable energies, circular economy criteria, and continuative maintenance are the correct strategies for boosting the social revitalization and for improving fairness, safety, architectural quality, human comfort, energy efficiency, and sustainability in this public housing neighborhood” [

25].

The strong link between climate change and urbanization has been confirmed in the literature [

26,

27,

28,

29]. The impact of climate change on the quality of life had already been noted in the 1970s [

30]. However, climate-related issues are still poorly considered in quality-of-life assessments [

31,

32,

33].

Political conditions and social support are key factors in the transformation of housing issues for the elderly. Legal tools should be as accessible as the space of a flat or a city. Perhaps, further study of older people’s representation in the local government is needed. Moreover, it is required to ensure that their voices are audible and to know whether they speak on behalf of their generation. On a wider level, research is also needed to determine how the current epidemic situation of COVID-19 has affected the trends related to the perception and spatial needs of future seniors. Therefore, it is recommended to repeat the research in the present context and to juxtapose the research results.