1. Introduction

At the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 20th century, the recognition of Jews as entitled to equality and citizenship rights included efforts within the community to integrate into their societies as citizens. As a result, they have become politically and culturally active in the wider European civil society, expressing their new energies in architecture. Presently, Europe is facing the problem of a huge and very visible Jewish cultural heritage, requiring rehabilitation, maintenance and valorization. This is particularly evident in Central–Eastern countries, where the Jewish minority represents a minimal fraction of the population. However, It is worth noting that Jewish communities were very strong, rich, prosperous and well organized before World War II.

The Jewish heritage of different countries is an immense treasure of humanity. Spread over the centuries, through many states of the world, Jews have managed, in a short time, to build a material heritage of great importance, value and beauty [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This was mainly because they dealt extensively with trade, traveled long distances, assimilated knowledge in various fields, learned from other peoples, were literate and made progress inside the adoptive societies where they lived. They often bought valuable properties and real estate in the central parts of the localities and built houses, places of worship, shops, ritual baths and other specific constructions.

At the end of the war, the number of Jews in Europe reduced significantly. Indeed, more than 6 million people of Jewish nationality died without guilt in Nazi camps [

5]. Many of the survivors went to other lands (Israel, the USA and so on). The war affected their constructions; the religious ones were destroyed or desecrated or received improper destinations. Few have retained their role and purpose [

6]. In some villages, only the cemeteries and the memories of some older people, who have direct information from those times, remain to date. Their experience needs to be taken over and passed on to new generations.

Currently, there are “88 synagogues in Romania, and only 43 functions as such… one third (34) of the total number of synagogues are historical and/or architectural monuments… Of the over 720 localities where there are Jewish Cemeteries, only in 148 of them we can still find Jewish communities” [

7]. The newest synagogue was built in Sighetu Marmatiei, Maramures County, inaugurated in 2021—the only one built-in post-war Europe. However, the architectural testimonies of Jews can be found in many other cities in Romania [

8,

9,

10]. In Oradea, the first Jews were mentioned in 1489. The maximum number was recorded in 1941, 21,333 people, which accounted for 22.95% of the total population. Only 3313 Jews remained in the city by September 1945. In 1992, only 294 were registered, representing 0.13% of the population [

11]. The city has a rich and diversified cultural heritage, consisting of religious monuments (synagogues, cemeteries) and buildings of great beauty (houses, palaces). The vast majority of them are listed on the list of historical monuments, both as attractive elements locally and nationally or even internationally [

2].

Therefore, the built Jewish heritage must be preserved in situ to maintain its original appearance and functionality, considering that the Municipality of Oradea is one of the most famous destinations in Eastern Europe for cultural tourism based on these heritage monuments [

12,

13]. At the same time, the palaces built by the city’s Jewish community between the 19th and 20th centuries are true local symbols, creating a bridge between the past and the present, being of indisputable value to the local community. Thus, Jewish heritage must be preserved, capitalized on and promoted as soon as possible before they are completely destroyed, especially where the number of inhabitants of Jewish nationality is low and cannot solve the numerous and urgent cases in localities [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Based on the accelerated development of computer processing power and computational algorithms, new methods have been identified by which cultural heritage can be documented, preserved and promoted [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. These technologies identify terrestrial laser scanning (TLS), which can render in a three-dimensional format both at the point clouds and the textured surfaces of the target objects [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. There are several advantages and disadvantages in the field of cultural heritage conservation through digital technologies such as TLS. The preservation and reflection of memory, history and tradition can be altered by creating virtual cultural repositories at the level at which a real museum can make it through its functions and means. In contrast, virtual museums and digital reconstructions of cultural artifacts help to protect, preserve and promote [

29]. Three-dimensional digitization of material cultural heritage (domain: Historical buildings, monuments and archaeological sites) is a multidimensional process that depends on the nature of the subject of the digitization and the purpose for which it is performed [

20,

30]. The documentation process in 3D models and basic plans is successfully used in territorial planning, tourism, conservation, restoration, etc. [

20,

31,

32]. All these innovative techniques work together to create a virtual reality, easily accessible, complete and complex, facilitating the protection of data obtained through digital storage for later use, which should not be neglected for responsible custody [

18,

33].

1.1. Jews of Oradea and the Belle Époque

Oradea, one of the most cosmopolitan cities in Romania, as the heir and successor of a Jewish community whose special coordinates placed it until the interwar period, is among the most important in this part of Europe. It is not easy to condense the general picture of the constructive effort of the Oradea Jewish community at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, a period marked by the activity of Jewish architects, builders and engineers or by the personality of some Jewish sponsors, but also of some great patrons, in the context of clear testimonies, evoking the Jewish contribution on the urban, cultural, intellectual and industrial development of the city, as well as the potential for capitalization in the current conditions. Oradea was once the most important and active Jewish community in Hungary (the largest after Budapest) and, after the Great Union, the most important and active Jewish community in Romania, witnessing the major impact of Jewish culture on the main aspects of society, the development of urban life, but especially on architecture [

34]. A valuable Jewish heritage must be protected and passed on to future generations in memory of the sacrifice of about 25,000 Jews in and around Oradea, deported and exterminated in the Auschwitz-Birkenau camps in May 1944. The drama of the Jewish community in Oradea was spent during the Horthy occupation (September 1940–October 1944), when the largest ghetto in Hungary operated in the city, after the one in Budapest [

35].

The Jewish quarter of Oradea does not have such a tumultuous past as Kazimierz. However, it maintains a specific unitary character over a much larger area. With the emancipation of the Jews, it spread to almost the entire historic center, to the city limits of the nineteenth century. A dramatic presence now materializes all this great past by absence. Thus, the lack of funds has stagnated rehabilitation/restoration or functional conversion [

36,

37]. There are still many Jewish buildings in an advanced state of degradation, which require essential interventions. The first step was taken by foreigners who studied our past and urged us to open our eyes to our values. Thus, through Fredric Bedoire’s book, The Jewish Contribution to Modern Architecture, Oradea’s fame had the chance to make its way around the world again after almost a century of oblivion [

38]. Bedoire, in his study of the contribution of Jews to the development of modern architecture from 1830 to 1930, includes Oradea in the chapter “

The Promised City”, along with Łódź, New York and Chicago, observing that it is perhaps the clearest European example of urban culture. The city is known for the active role of the large Jewish community in its economic and cultural development.

Due to its geographical location and rich historical and political experience, the city has witnessed sediments of various cultural influences, which have been manifested over time through architectural language and built heritage. As Philip Bohlman observes, “

As a border town with a cosmopolitan vocation and extensive rail connections, Großwardein [Oradea-Mare] flourished because of its cultural diversity and became one of the metropolises where Jews, from the East and from the West, they met”. It was, in fact, a city at the “

crossroads of many nations” [

39]. As a cosmopolitan “metropolis”, Oradea had a large Jewish community, which gradually became very important in the economic and social life of the city evident in the built fund. The most spectacular buildings constructed during the Belle Époque period were owned by large Jewish merchants, industrialists, bankers, entrepreneurs or intellectuals. To these are added many cultural, cosmopolitan aspects of the city, such as names of people, places, shops and cafes, titles of books and fashion magazines, various cultural trends and sequences of everyday urban life.

Many important Jewish architects and builders made remarkable contributions to the enrichment of Oradea’s built heritage; some of them worked in other important cities of the Austro–Hungarian Empire, including Vienna and Budapest. Along with them, the names of the Jewish financiers, to whom many of the most representative buildings of the city are due, should be listed. Their approach was punctuated by the evolution of architecture, from the discreet ambiance of the neoclassical, the exuberant eclectic to the “new” architecture of Art Nouveau, which unquestionably marked the image of Oradea and its specific features, a process reported objectively, to the context of the evolution of architecture in Central Europe. Thus, most of the buildings erected in Oradea at the beginning of the twentieth century bear the imprint of the Viennese Secession on the Hungarian chain and are due to the initiatives of the richest inhabitants, merchants, intellectuals, bankers, entrepreneurs and industrialists, mostly Jews, among which we distinguish, however: Emil Adorján, Imre Darvas, Arnold Füchsl, Mór Füchsl, Ede Kurländer, Adolf Moskovits, Miksa Moskovits, Jakab Schwarz, Adolf Sonnenfeld, Miklos Stern, Sándor Ullmann, Lajos Weiszlovits and L. Houses, villas, institutions, buildings or synagogues are not the only material heritage built by the Jews of Oradea. They also prospered through industry and industrial activity in Oradea through the diversity of production fields. The multitude of Jewish enterprises and Jewish entrepreneurs marked the urban and social development of the city at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries [

2].

Local or foreign architects, builders and craftsmen (mostly Jews) have created real works of art, which only prove the artistic and cultural connection of Oradea with the space of Central and Western Europe. In this sense, Bedoire remarked: “The purpose of the buildings in Oradea was not to expose entrepreneurs or families individually but to beautify the city and give it a place in the new world” [

38]. At present, a responsible and balanced intervention could qualify Oradea in the top of important cities in Europe in terms of Jewish heritage and cultural events that could take place. Indeed, Romania is already listed, along with Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic, on the tourism map profile. Under these conditions, developing a tourism system focused on capitalizing on the Jewish cultural heritage would make significant material contributions to the preservation and maintenance of local heritage. One solution would be to popularize Oradea’s image as a center of Jewish interest where, paradoxically, the vibrant Jewish life of yesterday still pulsates strongly through all the fibers of the city. For example, one of the little-known houses from an architectural and patrimonial point of view is the house where Eva Heyman lived with her parents. This 13-year-old child plays the role of symbol for the city of Oradea.

1.2. The Lost and Found Journal

The Holocaust literature has reached a thematic supersaturation [

40]. This hypothesis is also reinforced by the study of Éric Conan and Henry Rousso on the stages of awareness of certain limited events [

41,

42], such as the Holocaust, beginning with (1) a form of oblivion (1944–1955), followed by (2) the consolidation of the discourse, (3) its demystification and, last but not least, (4) the formation of an obsession with this discourse. Beyond a seemingly sterile categorization, this staging of the Holocaust discourse explains forgetting/ignoring a little girl’s diary, Éva Heyman, nicknamed in the literature (as it exists) as “Anna Frank of Transylvania”. Éva Heyman, a well-educated thirteen-year-old girl from a wealthy Jewish family with liberal visions, wrote a diary in Oradea during the Holocaust. We already know from the first pages that he comes from a rich family of Hungarianized Jews. In the pages of the diary, Éva wrote about her personal feelings; petty idylls with boys; carefully noted her relationship with her family; and described the constant fear of Nazi officers, deportation and the gloomy future [

43]. Éva Heyman was deported to Auschwitz, her last record being on the day of the deportation of Jews from Oradea. Her mother, a Holocaust survivor (on the famous golden train), returned to Budapest, where she retrieved the girl’s diary and published it. The volume was originally published by Eva’s mother, Ági, in 1948, after which she committed suicide following depression. It is interesting to note how, in the Hungarian version, Ági Zsolt appeared as the author, and the title is

My Daughter, Éva [

38], as if the text were a creation of her mother. In 1964, the text was translated into Hebrew by Yehuda Márton under the title

Yomanah shel Evah Hayman. From the Hebrew version, the English translation was published in 1974, entitled

The Diary of Eva Heyman, and a second edition appeared in 1988, entitled

The Diary of Eva Heyman: Child of the Holocaust. In 1991 a volume appeared in the Romanian space, prefaced by Oliver Lustig [

43], and in 2013 in French, under the title

J’ai vécu si peu [

44]. We can already see how the diary is timidly edited, with the Romanian edition being almost inaccessible to the public.

By using Instagram Stories, the technology entrepreneurs Mati and Maya Kochavi created a visual diary based on the short life of Eva Heyman to raise awareness of the Holocaust among the new generation and attracted 300 million video views and 1.2 million followers, demonstrating that social networks are the best way to reach the younger generation. The 70 short videos of the film shot with cell phones in Ukraine about Eva’s experiences were posted on Instagram for 24 h with the frequency established by the rules of the game of this social network. From her moments of joy to the arrival of the German tanks, through the confinement, deportation and murder of the Hungarian Jews. All told and shared in the most up-to-date audiovisual language. The account, based on the audiovisual reproduction of her personal diary, was activated on May 2019, coinciding with the start of Yom Hashoah (Holocaust Remembrance Day) and was endorsed even by Israel Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who declared on Twitter that “Every day, episode by episode, the great tragedy of our people is essentially exposed through the story of one girl”.

Eva Heyman’s diary fell into a separate category of Holocaust literature [

45]. Jacob Boas framed this text in an anthology dedicated to children who, during the Holocaust, recorded their personal experiences in a diary. It is noteworthy that all of them died, and their texts went through many adventures to be recovered and published. The diary is fascinating in two ways. First of all, we witness the reflection of a large phenomenon, such as the Holocaust, from the perspective of a pre-adolescent. On the other hand, the little story of the little girl, her personal feelings and the impulses that determine her to write such a text give us a monster of what she understands from the family space from a psychological point of view. An approach from two perspectives would be useful precisely in order to be able to capitalize on the text pertinently: the psychological one and the contextual one. This is the reason why diaries are so extraordinary. Compared to other testimonies, memoirs or novels, diaries reveal the immediate thoughts, fears and wishes of the person writing them. They, therefore, represent the most personal and intimate accounts of someone’s life.

The “Tikva” Association from Oradea, through various actions carried out with the help of volunteers, made the tragedy of Éva known to the general public. Among the most important achievements of the association was the erection of a statue of the girl in Oradea, in Nicolae Bălecescu Park, the place from where 3000 Jews were deported to Auschwitz every day between 24 May and 3 June 1944. In addition, the death trains left, the statue symbolized all the children from Oradea and Bihor who died in the Holocaust, and the association organized a traveling exhibition. Furthermore, it included the case of the child in educational materials dedicated to the Holocaust.

1.3. The Study Object—Heyman House

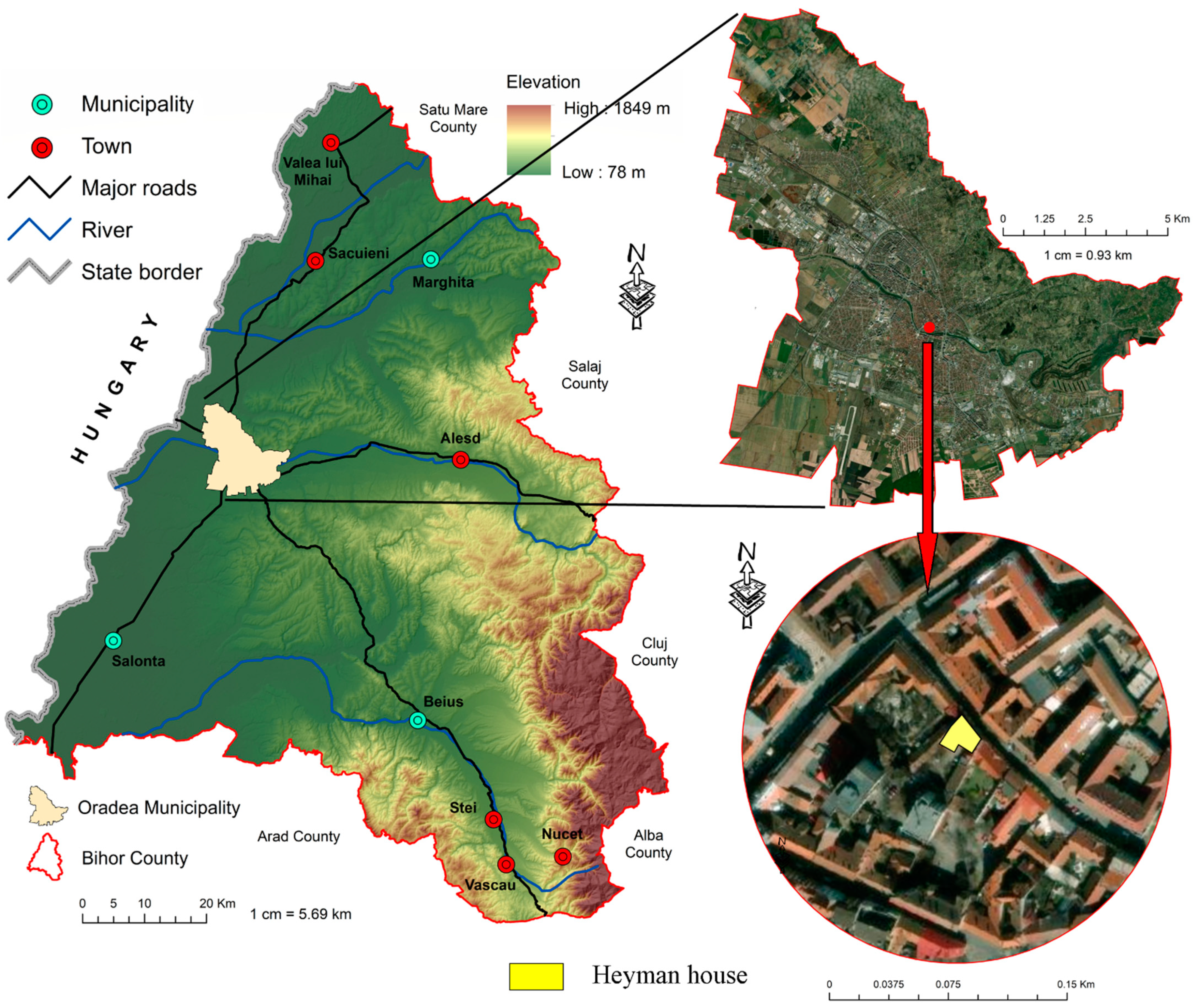

Heyman House is located in the center of Oradea, inside the so-called “Oradea Historical Center” Urban Ensemble, on Aurel Lazăr Street 3, next to other objectives on the List of Historic Monument Buildings in Oradea, such as Dr. Aurel Lazăr House, Darvas la Roche House or the Oradea State Theater (

Figure 1). Considering the central location and the fact that the history of the construction is very little known, most tourists and even the inhabitants of the city pass without noticing and discovering it. The house is a bigger building with a common courtyard and a staircase that climbs up to the top floor. Currently, the house encloses commercial space and offices on the ground floor. The upper floors were sold privately and are used as living apartments.

The memory of the place, now lost, involves the Veiszlovits family, well-known Jews from Oradea between 1890 and 1944. The property on Aurel Lazar Street, no. 3 and Republicii Street no. 3 were bought by Adolf Veiszlovits (1831–1907) and bequeathed, in 1910, to Iosif Heyman’s widow, Luiza, born Veiszlowits (1871–1944), Adolf’s daughter. The two properties communicated with each other on Republicii Street no. 3 sheltering the house and company of Adolf Veiszlowits. Inside the plot on Republicii Street no. 3 was the old summer theatre, a wooden construction, which became a cinema in 1927. Although initially, on Aurel Lazar Street no. 3, there was no construction on the street, there is a stable inside. Engineer–architect Bela Heyman was the owner of the Heyman cinema, located on the plot on Republicii Street no. 3 (where today there is a block of flats and a commercial building with a floor).

The house on Aurel Lazar Street no. 3 (

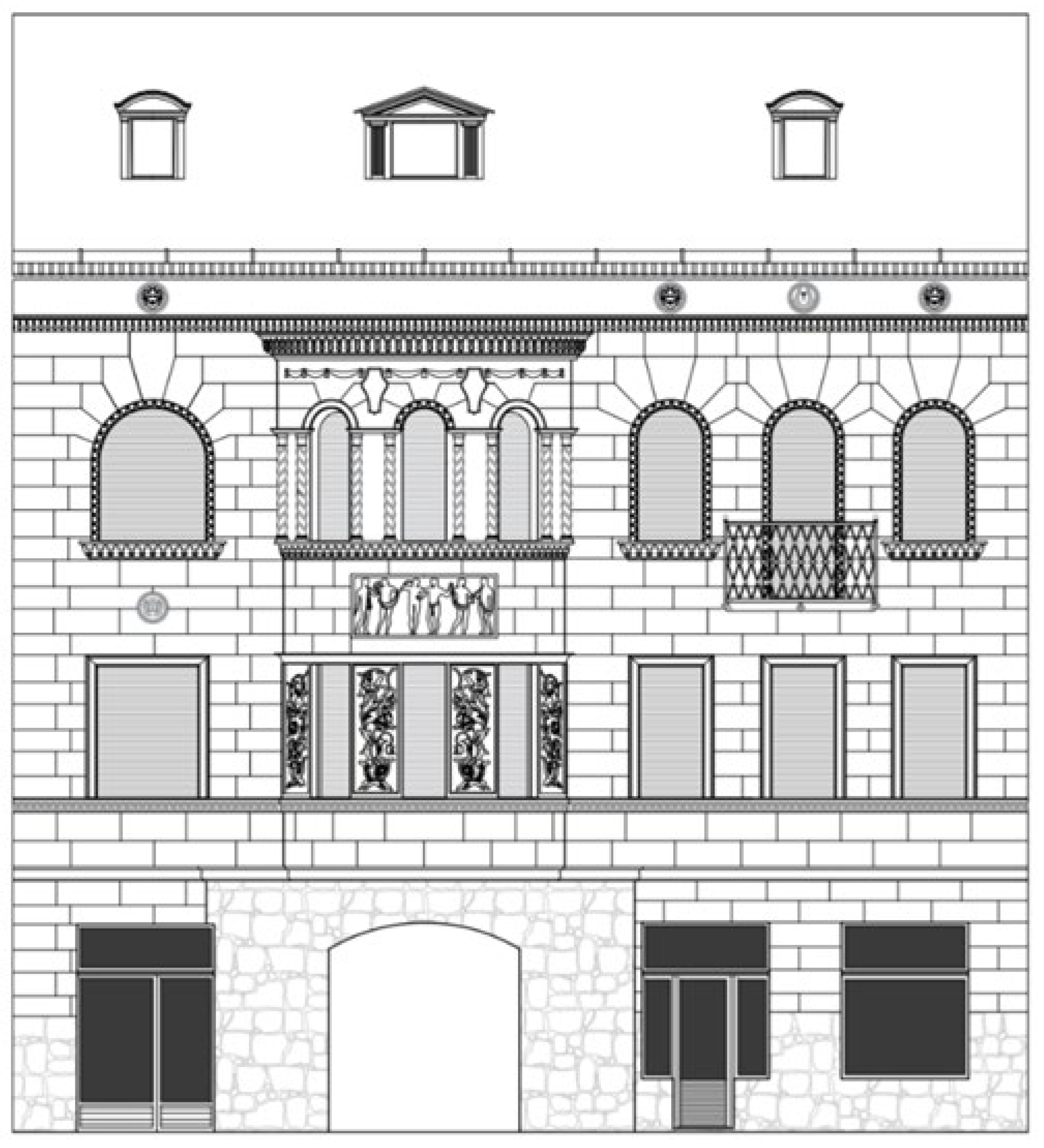

Figure 1) was built in 1928 (according to the year inscribed on a facade from the courtyard). Here lived Bela Heyman on the second floor, and his sister Lili Moldovan, on the first floor. Eva Heyman and her mother, Agnes Racz, lived in this house until 1935, when their parents divorced. The building has a balanced, elegant facade with refined ornamental elements, neo-classical and neo-renaissance. The bas-relief with human figures, the panels with floral elements on the main bay window, the window frames and the cornices that mark horizontally are noticeable. There is a metal element at the corner formed by the pipe and the eaves, with curvilinear shapes, which constitutes the monogram HB (Heyman Bela). The facade from the courtyard is equally interesting. It is distinguished by the general composition, the hardware of the parapets of the balconies and doors and the carpentry of the windows and doors. The interior has been treated with the same care and is distinguished by details and finishes. The architect is believed to have been Frigyes Spiegel or Bela Heyman.

Starting from the architectural gem represented by the Heyman House, this paper used three-dimensional laser scanning (TLS) and cartographic method to document the building to prevent further damage due to material vulnerability, climatic conditions and harmful human action. The data in digital format thus obtained were processed and analyzed in dedicated programs to obtain expressive results for determining the current state of conservation and the solutions needed to be adopted to improve its condition. The 3D models thus created were uploaded on an interactive platform through which users can navigate and interact with the object through various available filters, resulting in a real-time simulation designed to meet their knowledge needs [

46,

47]. This approach can represent a pilot project to obtain digital materials of the material cultural heritage in general and the Jewish one, in particular, from Oradea Municipality, all this leading to responsible custody of the monuments.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology used for documenting the building took into account both the obtaining of 2D and 3D visual information and the extraction of quantitative and qualitative data related to different characteristics of the building. Three main stages were adopted to achieve this goal depending on the results provided: 1. Realization of the 2D model of the facade by the cartographic method; 2. Realization and interpretation of the 3D model of the facade by terrestrial laser scanning (TLS); 3. Online publication of the 3D model.

2.1. Realization of the 2D Model of the Facade by the Cartographic Method

In order to achieve the two-dimensional model of the facade, we took into account field measurements with the total station Spectra Precision Focus 8 in order to georeference the object based on the target points applied to the building. These determinations resulted in the size and contour of the facade and its gaps.

The vectorization of the elements related to the facade of the building was made on orthogonal photographs taken from the field, thus eliminating perspective errors. The very high resolution of the photos purchased with the Pentax K20D camera was the basis for obtaining very good results. This was performed by taking photos from different angles of the analyzed facade and from different positions so that as many details of the facade as possible could be taken. The images thus obtained were entered into Adobe Photoshop 2020, where they were processed in terms of lens correction, correction of geometric distortions and chromatic aberrations.

Furthermore, they facilitated the most detailed distinction of all the elements. The measurements were processed in the Toposys 7.0 software. This program offers the possibility of processing the geodetic network, performing calculations and adjusting the data packet. In the last phase, the facade survey. The final model of the analyzed object was made in the commercial software AutoCAD 2022.

The Spectra Precision Focus 8 total station and Pentax K20D camera were chosen due to the fact that they are complementary, portable and easy-to-use instruments while capturing and rendering with high fidelity the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of heritage buildings. At the same time, these tools are some of the most used for recording work that requires high accuracy. The computer programs used to create the final model were chosen in such a way as to leave the possibility of adjusting and correcting the measurements taken from the field, as well as having numerous features for 2D and 3D design.

2.2. Realization and Interpretation of the 3D Model of the Façade by Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS)

The terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) of the building facade was performed with the Leica C10 Scanner, a device that has an accuracy of ±4 mm. This device has the advantage of offering a fast and high-quality scan, and the built-in Smart X-Mirror video camera has the ability to capture and reproduce the texture of the scene faithfully.

For a complete and accurate capture of the target object, the scan was performed from three different stations: the building’s center, left and right. In order to merge the resulting three-point clouds, several three target points were placed directly on the scanned surface when purchasing the field photos. Target points were placed so as to be visible to the scanner used, and their position was accurately determined from any of the three scan points.

The three TLS point clouds on the Heyman House facade were introduced for processing in Leica Cyclone software. This is a software specialized in the processing of point clouds, which offers a wide set of options for processing the results obtained after laser scanning in fields such as engineering, construction or topography.

The first action taken in this software was to georeference point clouds in a local coordinate system to be further analyzed using different computational algorithms. At the same time, the relationship between the three scanning stations was established here through a procedure called scan registration. The procedure aims to unite the three clouds of resulting points and render them in the form of a single compact entity. This action is automatic, based only on the measurement results of the distance from each scanning station to the control points located on the facade.

The integrated point cloud was further introduced into AutoCAD 2022 2D and 3D processing software developed and marketed by Autodesk Revit. The analyses performed in this program were aimed at generating a continuous mesh surface based on the point cloud obtained, as well as the arrangement of the texture over it. Furthermore, the stage of making the 3D model is important in obtaining a model suitable for interactive visualization and the analyses necessary for the restoration–conservation processes (

Figure 2).

The results were evaluated in CloudCompare v2.12 alpha to determine characteristics such as density, roughness, and surface variation, which practically shows the degree of accuracy of the point clouds and, therefore, suitability for interactive viewing. In addition, point clouds were also examined to determine with great accuracy the aspects related to physical characteristics: Height, width, length and verticality.

2.3. Online Publication of the 3D Model

The complete and interactive presentation of the models made was chosen for publication within the Atis cloud platform. This platform is a free one that aims to manage and capitalize on three-dimensional data resulting from laser scanning and photogrammetry. It is easy to manage by the content creator and easy to access by visitors. The quality of the models and the performance of the running mode is also very high.

The webpage is based on a unique approach to other platforms for interactive viewing of three-dimensional models, allowing the user to view the data presented interactively and change the perspective on the scene and the viewing mode. Thus, the user can view the model in “3D ships” format or in scan format, access each scanning station separately and view the results obtained from that point in many ways, from RGB to polygonal model and intensity fashion. Nevertheless, one of the most important options of Atis is based on offering the possibility to perform different measurements directly on the three-dimensional model published in the cloud quickly and easily.

4. Conclusions

The need to digitize the building to preserve and promote the elements of Jewish material heritage is of real applicability to solidify the ethnic identity in Oradea in particular and Romania in general. For such former or present multi-ethnic sites, the management of the Jewish heritage can thus contribute to a better understanding of the complexity of niche tourism and heritage-based tourism [

8,

55,

56]. The working methodology approach is a simple one, from the implementation point of view, being at the same time very fast in execution compared to the classic documentation methods. The disadvantages stem from the fact that the software and the necessary equipment are quite expensive.

A key component in this paper is the metric survey of a building of true historical and architectural value together with documentation, study and valorization. The spatial documentation of Heyman House is of the highest importance. It offers an accurate record of the site and provides a comprehensive base dataset by which site managers and conservators can monitor it and perform necessary restoration work to ensure its physical integrity. Three-dimensional models of buildings can be used by engineers and architects, scientists and historians. In urban cultural heritage, the 3D model is useful for documentation, visualization and reconstruction purposes. Thus, the work methodology aims at offering practical possibilities for the implementation of the evaluation–conservation–promotion trinomial. The way of obtaining the data in digital format allows the analysis and determination of the degraded areas of the monument (evaluation), on the basis of which the policies necessary to protect the monument (conservation) can be drawn up, and the publication of the models leads to a better knowledge of history building (promotion).

Heyman House 3D model is nothing less than a documentary of a historical monument. It can be further used for scientific research to preserve the site’s memory, and it can give access—either digitally or in printed form—to a physical structure that cannot otherwise be seen. Any detail preserved in an intelligible and reproducible form can support a reconstruction effort (if necessary) of this monument. Virtual models can be shared worldwide through the internet and easily stored in a digital format or printed with a 3D printer. The 3D model can support different groups of people who are involved or interested in the topic of Oradea Jewish urban cultural heritage and Eva Heyman’s story, such as local, regional or national government institutions, Oradea municipality; scientists, local inhabitants and other individuals with interest in architecture and the urban heritage.

At the same time, such representations could capitalize on the existing Jewish heritage and history by integrating Oradea into a specialized tourism circuit and developing a cultural tourism profile. This representation can increase the attractiveness of the monument, considering that 3D representations are recognized as having an increased impact on potential tourists, causing them to also visit physically after experiencing the virtual visit. At the same time, virtual representations can help make the monument accessible for people with mobility impairments or can have educational purposes for children and teenagers.