Abstract

With the significant increase in global ageing and its derivative risks, governments and academic communities have been widely concerned with research on facilities of combined medical and nursing care for the elderly (FCMNCE). Using Citespace and VOSviewer bibliometric software, in this paper, we explore the evolutionary phases, hotspots, and trends in research on FCMNCE. First, the concept and connotation of FCMNCE are clarified. Secondly, based on a bibliometric analysis of the number of annual publications, disciplinary distribution, publication sources, and country distribution, we classify research on FCMNCE into four phases: the exploratory phase of influencing factors, the constructive phase of combined medical and nursing care patterns, the improvement phase of life quality, and the synergistic development phase of science and technology. Thirdly, based on a bibliometric analysis of keyword clustering, annual overlap, and burst keywords, the research hotspots of FCMNCE are identified. Finally, we predicts that future research on FCMNCE will be characterized by the trends of smart elderly facilities, smart medical services, and public health risks. Our conclusion can help researchers to understand the research status and development trends of FCMNCE and select future research directions based on their disciplinary background.

1. Introduction

With the significant increase in global ageing and its derivative risks, the United Nations (UN) and major international organisations have made “healthy ageing” one of the priorities in their sustainable development and strategic plans. The World Health Organization (WHO) has proposed “Healthy Ageing” [1]; “Long-term-care systems” [2]; and other concepts, goals, and strategies, resulting in an essential international consensus. Healthy ageing is “the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older age” [1]. Healthy ageing can prolong the remaining healthy life span of older adults and shorten the period of survival with illness or disability [3]. The combined medical and nursing care model can satisfy the medical and living needs of older people with various health conditions and is a critical strategy to achieve the goal of healthy ageing.

The combination of medical and health care is a sustainable social care model that effectively integrates “medical, recuperation and rehabilitation” [4,5]. It is often understood as the expansion and cooperation of services between elderly institutions and medical institutions. The term “medical” refers to the provision of integrated medical care services, including preventive health care, disease diagnosis and treatment, rehabilitation quotation markcare, and hospice care. The term “recuperation” refers to daily life care, psychological comfort, leisure, and entertainment. The term “rehabilitation” mainly covers rehabilitation guidance, functional exercise, and habilitation. The combined medical and nursing care model can be divided into three models: the cooperative alliance between nursing institutions and medical institutions, the transformation of medical institutions into “combined medical and nursing care” service institutions, and the addition of medical institutions to nursing institutions [6]. Early models of integrated care are called “integration of health care delivery” [7] and focus on health and social care to improve the continuity of care and the efficiency of the healthcare system. Multiple countries have developed various paths of practice and promotion according to cultural backgrounds and current social welfare systems (Table 1). The concept is mainly demand-driven and provides sustainable services that integrate medical care, rehabilitation and health care, daily care, and chronic disease management for those in need by organically integrating idle healthcare service resources with elderly care resources through varying degrees of integration [8,9,10]. In this paper, the combined medical and nursing care model is defined as a professional, comprehensive, efficient, and continuous care model for the needs of the elderly.

Table 1.

FCMNCE research-related policies.

In this stage, integration of health care is the starting point for achieving the goal of healthy ageing in countries worldwide, and various models of elder care have been developed. For example, in the United States, there are three existing models: the Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) [16,17], long-term acute care (LTAC), and long-term care hospital (LTCH). The UK has introduced the National Health Service (NHS) [15], Japan has introduced the Plan of Home-Based Nursing Care (PHBNC) and the corresponding insurance system [18], and Canada has introduced the Program of Research to Integrate Services for the Maintenance of Autonomy (PRISMA) model of ageing [19]. International organisations such as the United Nations (UN), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the World Bank (WB) have put forward a series of international consensus or principles. The primary policy documents of countries and international organisations worldwide are shown in Table 1.

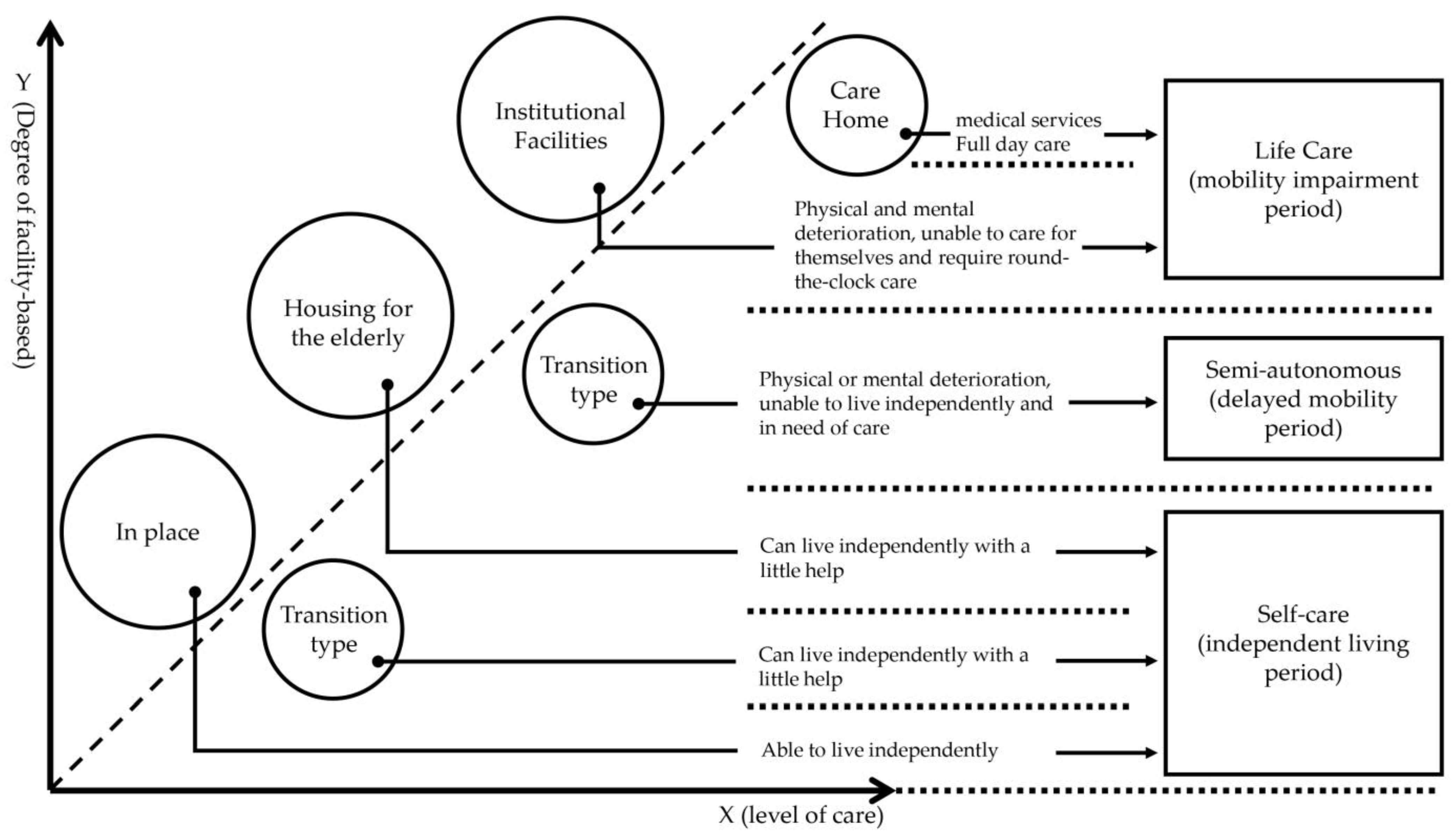

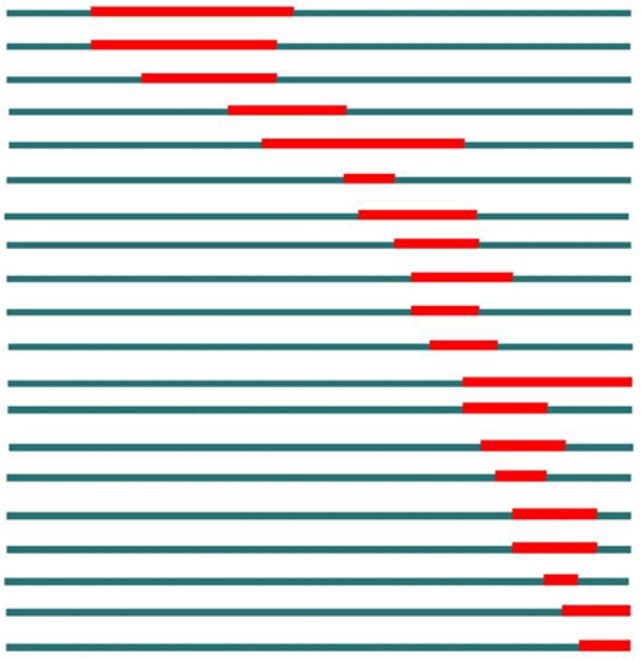

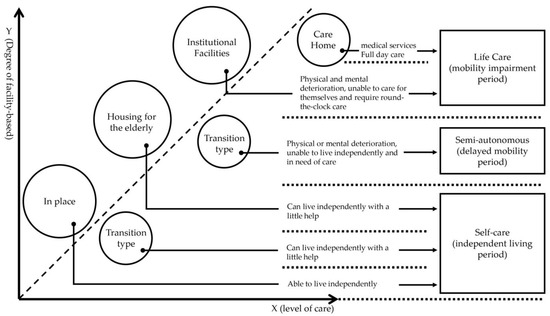

Facilities of combined medical and nursing care for the elderly (hereinafter referred to as FCMNCE) is the material carrier to run the combined medical and nursing care model for the elderly. Its service targets all elderly with various health conditions and in various life stages, and the service contents include disease prevention, health intervention, long-term care, and hospice care. Service carriers include families, communities, and institutions. Depending on the research field, FCMNCE research can be divided into research on theoretical systems, planning and architectural design, usage demand, functional configuration, and service guarantee (medical insurance) of FCMNCE. Referring to the conclusions of Li Bin’s comparative analysis of the type structure for facilities for the elderly in China and Japan [29], in this paper, we describe the type structure of FCMNCE in terms of in-place housing for the elderly and institutional facilities (as shown in Figure 1) and provide an overview of the architectural design research on elderly service facilities (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the type structure for FCMNCE.

Table 2.

Overview of research on the architectural design of service facilities for the elderly.

The medical, recuperation, and rehabilitation model is aimed at the self-caring elderly, older people with chronic diseases, and those with dementia and disability. The FCMNCE design needs to strike a balance between functionality, economy, safety, and quality, with a focus on medical, recuperation and rehabilitation long-term care needs; the physical and mental health of the elderly; comfortable spaces and functions; and timely and effective medical services. Therefore, the architectural design principles of FCMNCE should include (1) convenient location and a reasonable general layout, (2) convenient flow of care function areas and basic professional medical facilities, and (3) architectural space design that fits the physiology and psychology of the elderly.

In the context of increasing global ageing, FCMNCE research has become a current research hotspot in healthy ageing [41]. Despite numerous studies on the combined medical and healthcare model of ageing and service facilities for the elderly, no bibliometric-based FCMNCE research has been published to date. The terms TS = (combination of medical and health care OR medical and nursing combination) AND TS = (elder OR aged) AND TS = (service facility OR facilities) AND ALL = (Citespace OR VOSviewer) were searched in the Web of Science core database with the document type set as paper and language set as English. Although some relevant review studies have been published (110 publications), there is no literature involving the use of bibliometric software (e.g., Citespace OR VOSviewer) on integrated healthcare in elderly service facilities. The search date was October 6, 2022. Therefore, it is necessary to comb through the relevant literature on FCMNCE research to clarify its research characteristics and stages and discover its research lineage.

2. Methods

Bibliometric and visual analysis methods are commonly used in many disciplines to reveal networks of relationships, knowledge, and trends between disciplines [42]. However, the use of single bibliometric software has been reflected in existing studies as having functional shortcomings, and the results of analysis lack validation [43]. Citespace and VOSviewer are commonly used bibliometric mapping software programs with a high frequency of use and wide distribution [44]. Citespace can detect and visualise emerging trends and fundamental changes in the discipline and reflect research dynamics based on a time-varying mapping from the research frontier to the knowledge base [45]. VOSviewer visualises research results and has unique advantages in terms of clustering techniques and map presentation [46]. Therefore, in this study, we used a combination of Citespace and VOSviewer to conduct a scientific knowledge mapping analysis of the FCMNCE literature data to identify potential knowledge links between research results.

The WOS Core Database is an internationally recognised authoritative database with the most representative, cutting-edge, and thorough knowledge and concepts in international research [47]. Therefore, the WOS Core Database was selected as the data source for the present study. Firstly, we used the data analysis function of Web of Science (hereafter referred to as WOS) to determine the literature distribution characteristics of FCMNCE in terms of annual publication volume, subject distribution, publication source, and country distribution. Secondly, we used Citespace and VOSviewer bibliometric software to analyse the co-occurrence and clustering of keywords, co-citation, and temporal partitioning of the literature and to explore the development of FCMNCE and research hotspots by generating visual knowledge maps. Finally, based on the bibliometric analysis of keyword clustering, annual overlap, and keyword emergence, we predicted the development trends of FCMNCE research and proposed priority research recommendations accordingly.

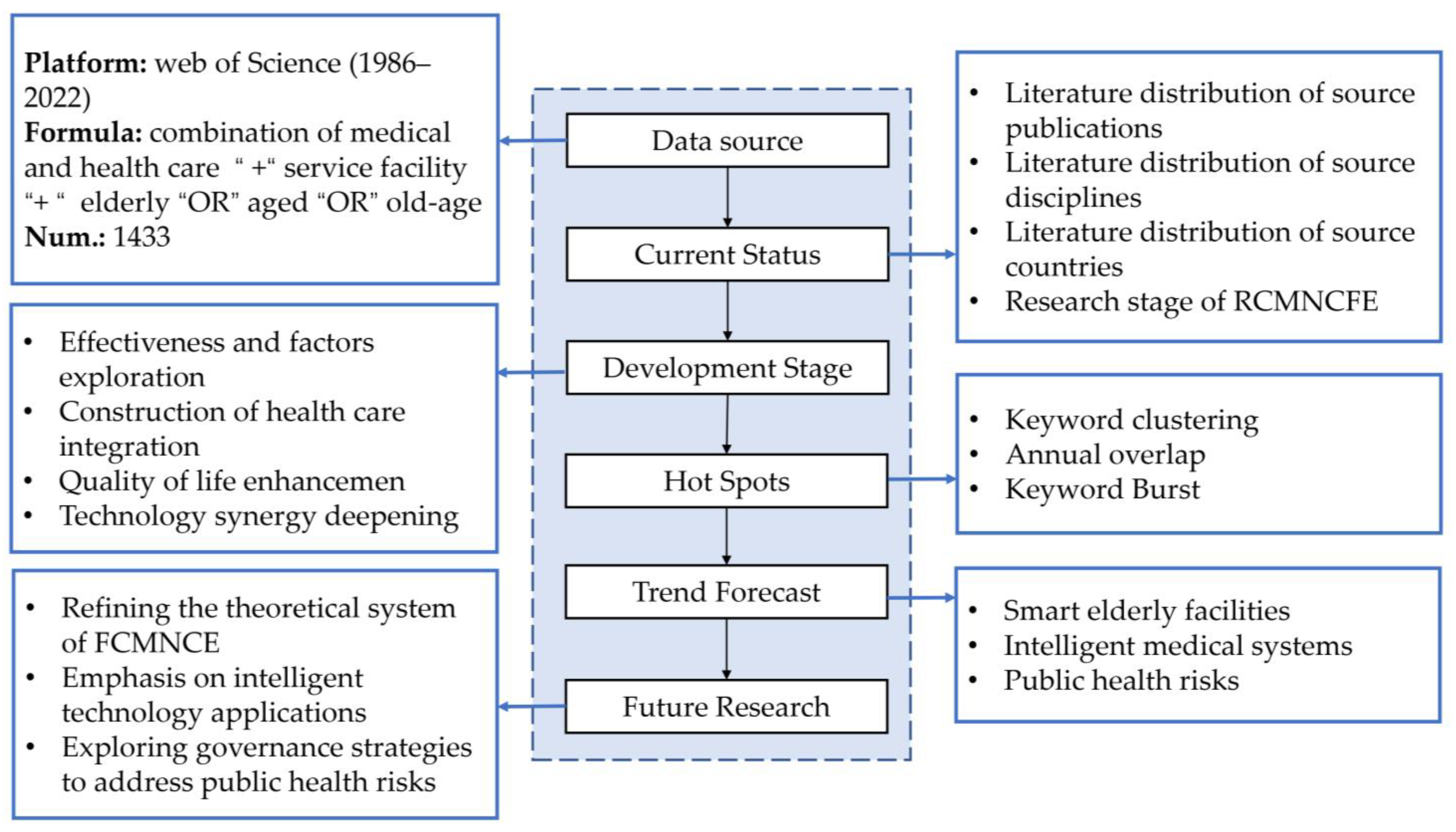

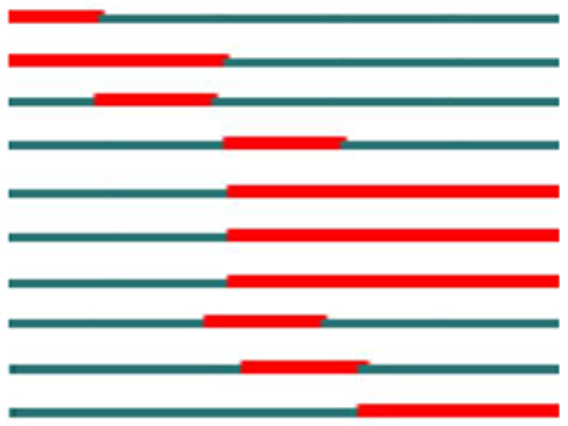

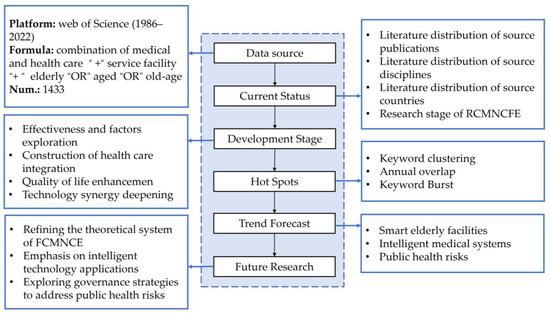

In this paper, the WOS core collection was used as the data source, with a search date of 6 October 2022 and a data range of all years (default 1975–2022). The papers were searched using “TOPIC” + “Document Type”, with “combination of medical and health care “, “elderly”, and “service facility” used as keywords for the search, and the language of the literature was limited to “ English” and “Article” type. The search was extended to include “combination of medical care”, “medical and nursing combination”, “old-age care service”, “medical care and elderly care”, “aged”, and “facilities” as search terms, taking into account differences in linguistic expressions. A total of 1433 literature publications were obtained in this search, among which the earliest appeared in 1986. The research framework of this study is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Outline of FCMNCE research design.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Literature Distribution

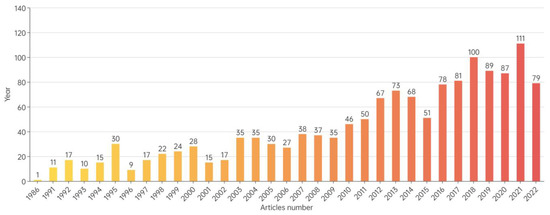

3.1.1. Annual Volume of Publications

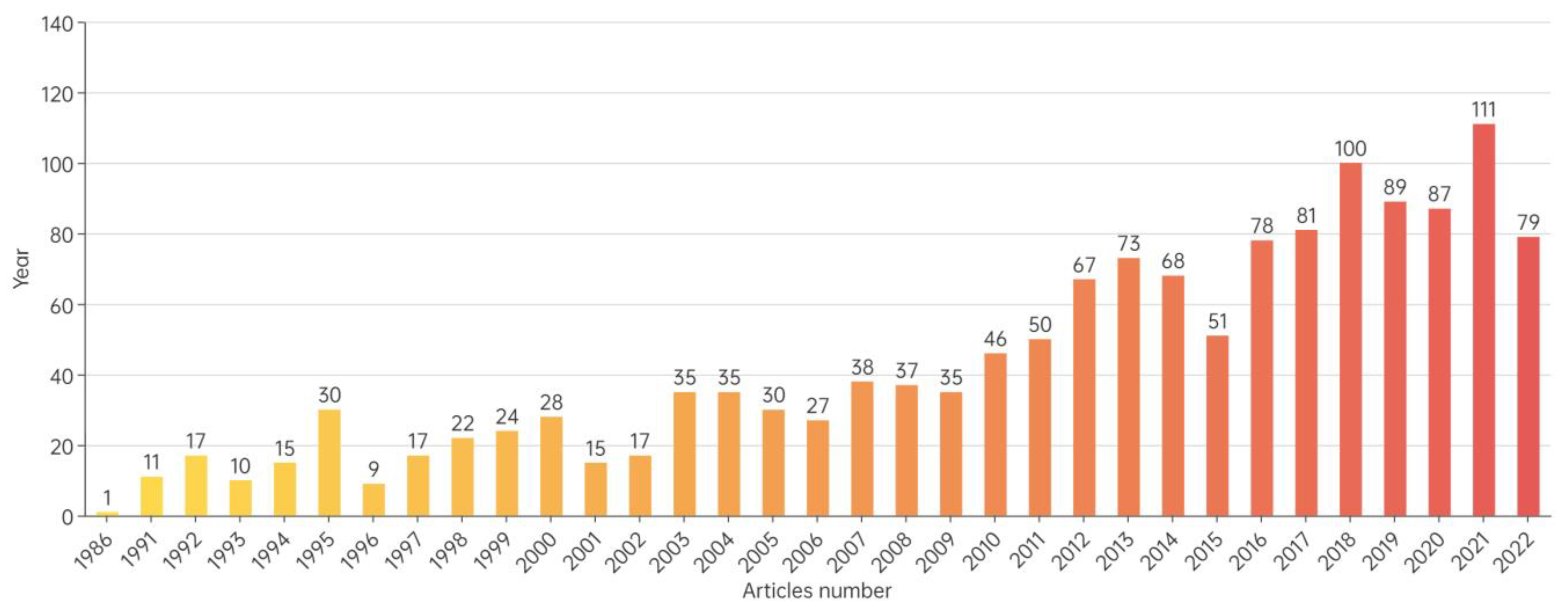

The volume of knowledge, disciplinary characteristics, and leading countries in the research field can be reflected by the variation in the volume of literature, the source disciplines, and the distribution of source countries [42,45]. The results of the WOS online analysis show a fluctuating upward trend in the overall volume of literature on FCMNCE research (Figure 3), with the annual number of publications remaining small until 2004 (fewer than 35 publications per year), indicating that FCMNCE research was still in the exploratory stage and had not yet received considerable attention. The period of 2014–2021 represents a primary developmental phase for FCMNCE, with approximately 46% (665 of 1433) of the articles published during this period. A total of 79 papers published have been published to date in 2022, with an estimated 120+ papers expected to be issued before the end of the year. The increased interest in FCMNCE research indicates that it is becoming a current hotspot in healthy ageing research and related fields.

Figure 3.

Number of FCMNCE research articles published from 1986 to 2022.

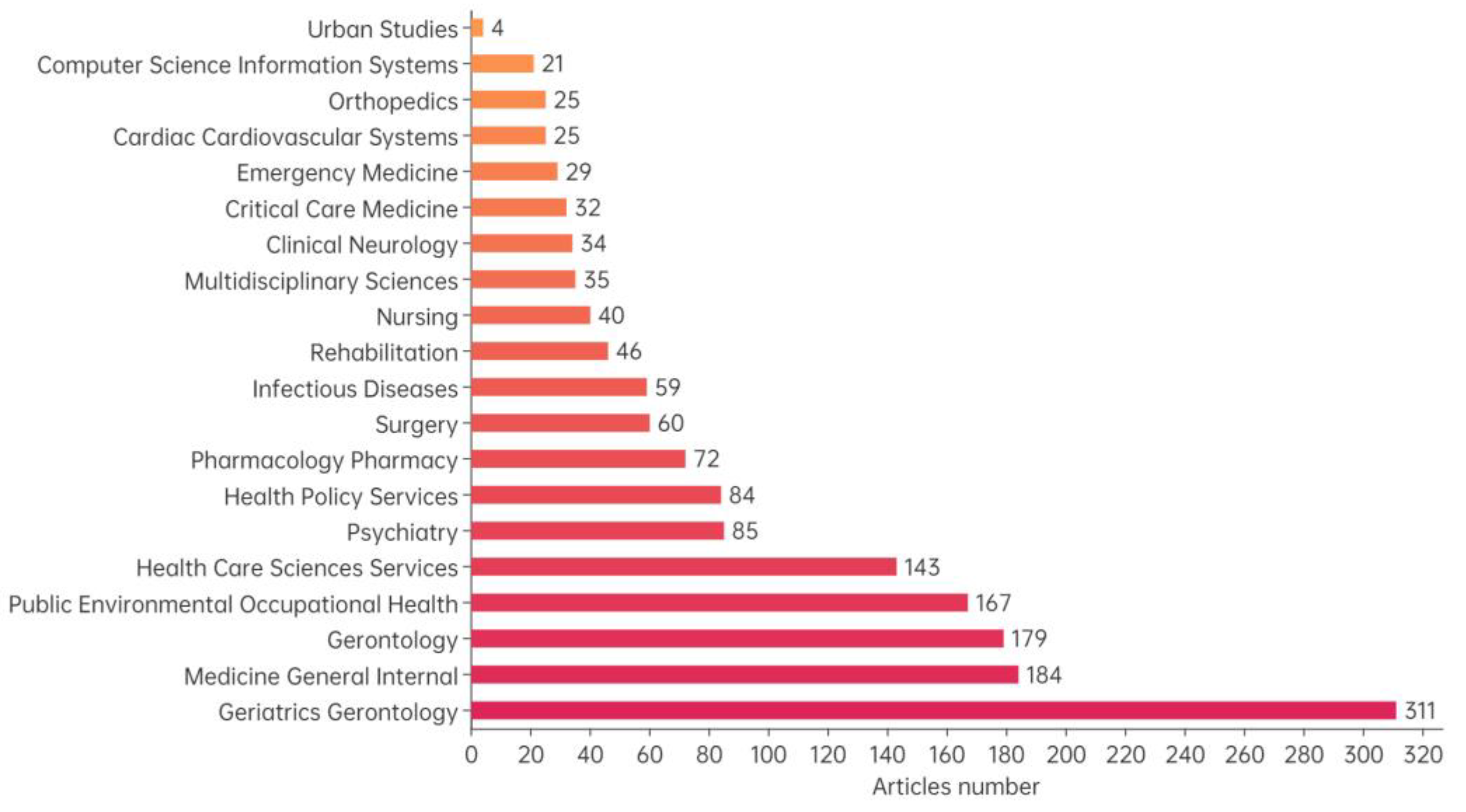

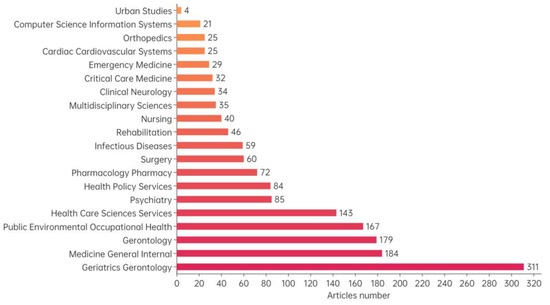

3.1.2. Disciplines of Literature Sources

In terms of the distribution of literature sources, FCMNCE studies are concentrated in the disciplines of geriatrics gerontology (21.7%), medicine general internal (12.84%), gerontology (12.49%), public environmental occupational health (11.65%), health care sciences services (9.98%), multidisciplinary sciences (2.44%), computer science multidisciplinary sciences (2.44%), computer science (1.47%) and urban studies (0.28%), reflecting the multidisciplinary character of FCMNCE research (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Distribution of FCMNCE research disciplines (top 20).

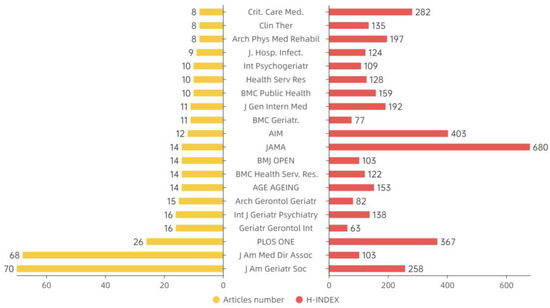

3.1.3. Literature Source Publications

In terms of literature sources, a total of 2472 publications were identified. The Journal of the American Geriatrics Society and the Journal of the American Medical Directors Association published the most research papers of FCMNCE, accounting for 4.89% and 4.75% of the total, respectively, with minimal difference in the proportion of publications published by other journals (Figure 5). The top 10 publications focus on ageing, health services, and public health.

Figure 5.

Source publications (abbreviated) and H index of FCMNCE research (top 20).

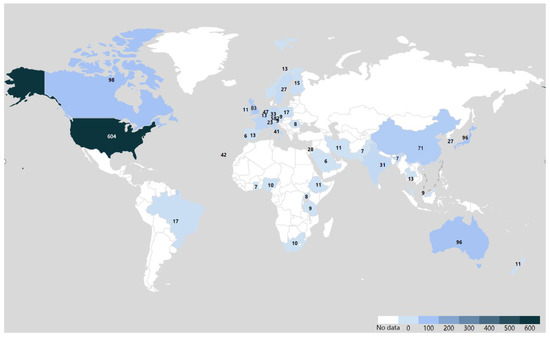

3.1.4. Countries of Literature Sources

Regarding the number publications per country (Figure 6), the top 5 countries accounted for 67.55% of the total number of FCMNCE research publications worldwide. The United States has contributed the most FCMNCE research publications (604 or 42.15%), followed by Canada (98 or 6.84%), Japan (98 or 6.84%), Australia (97 or 6.77%), and China (71 or 4.96%). The United States was the first country to conduct FCMNCE studies (1986). The US has more search results in the WOS core database than other countries, with an average of more than 10 articles per year since 1994 and more than 25 articles per year since 2011. In contrast, FCMNCE research started later in Canada (1991), Japan (1992), Australia (1991) and China (2002), and the average combined annual number of publications in these four countries was less than five before 2003. Since 2011, the average annual number of publications among these countries has exceeded 10. Since 2016, the combined number of publications in these four countries has increased significantly, exceeding 25, with a considerable potential for development.

Figure 6.

Distribution of FCMNCE research-issuing countries.

3.2. Development Phases of FCMNCE

Citespace mapping of keywords and highly cited literature temporal partitioning allow for the identification of FCMNCE research frontiers to predict research trends [42]. By combining the temporal distribution map of FCMNCE research keywords (Figure 7), the co-citation map of FCMNCE research literature (Figure 8), and the centrality and frequency of FCMNCE research high-frequency keywords. (Table 3), in this paper, we show that FCMNCE research has prominent stage aggregation characteristics manifested by a focus on various research themes, contents, and elements. Moreover, taking into account the influence of important government policies and international organisations at different times, our thesis divides FCMNCE research into four stages: exploration of influencing factors, the construction of medical and healthcare integration, quality of life enhancement, and deepening of scientific and technological synergy; herein, we review the main research results and characteristics of each stage. The bibliometric analysis software used to produce Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12 is shown in Table A1 of Appendix A.

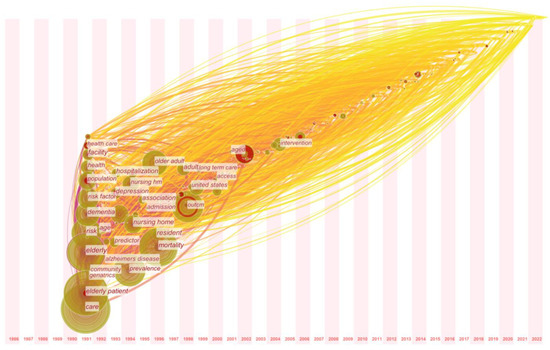

Figure 7.

Temporal distribution map of FCMNCE research keywords.

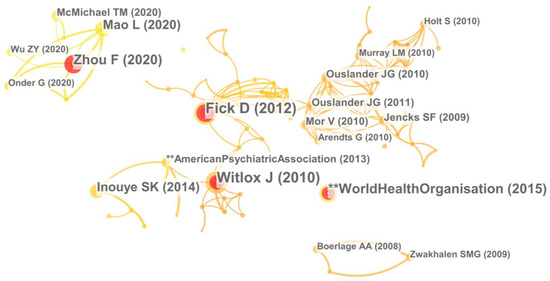

Figure 8.

Co-citation map of FCMNCE research literature.

Table 3.

Centrality and frequency of FCMNCE research high-frequency keywords.

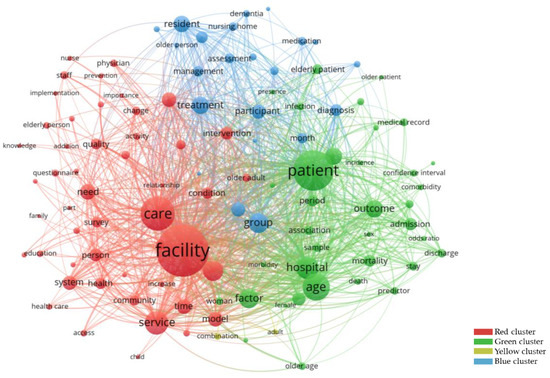

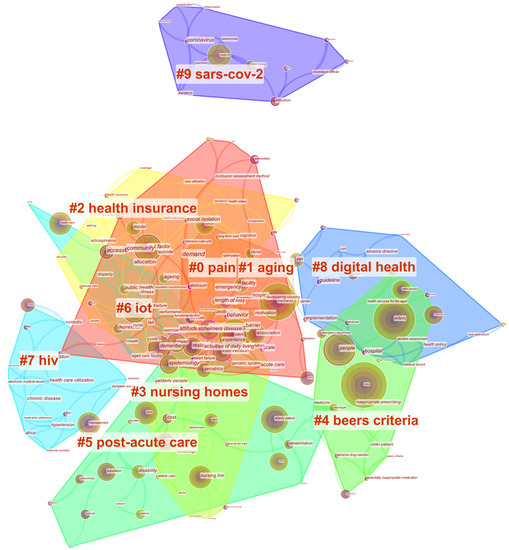

Figure 9.

FCMNCE research keyword co-occurrence network map.

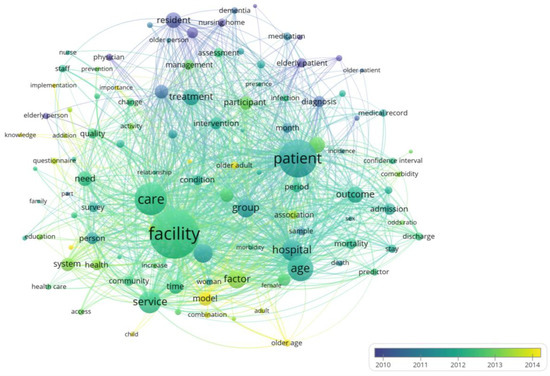

Figure 10.

FCMNCE research keyword annual overlap map.

Figure 11.

Cluster mapping of FCMNCE research keywords, 2018–2022.

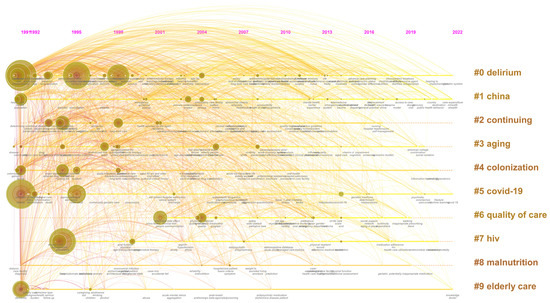

Figure 12.

FCMNCE research time-zoned axial map (top 10 categories).

Figure 7 shows the Temporal distribution map of FCMNCE research keywords, where each node represents a keyword, and the frequency of keyword occurrence positively correlates with the node size. The higher the frequency of the keyword, the larger the node. Connections between nodes indicate co-occurrence connections between keywords [48], and the bottom of the image indicates when the keyword first appeared. According to the co-occurrence frequency, the main keywords are care, elder patient, health, risk, and dementia. We categorised the keywords by time stage and added frequency and centrality information to obtain Table 3. Figure 8 shows the co-citation-partitioned mapping of the FCMNCE research literature, where the nodes represent literature citations in the core database and the connections represent the co-citation relationships between the nodes [49], with the strength of the co-citation relationships between the literature reflected by the node connections. Node size is proportional to the importance and novelty of the literature, with larger nodes indicating that the literature is essential in FCMNCE research.

3.2.1. The Exploratory Phase of Influencing Factors (1986–1995): Fragmented and Segmented Exploration

In this phase, national and institutional policies on senior care facilities were introduced, such as the UN Vienna International Plan of Action on Ageing (1982), the United Nations Principles for Older Persons (1991) and Proclamation of Ageing (1992), the NHS model (1993) promulgated by the UK, and the PACE plan for the elderly (1995) implemented by the US. These plans put forward some principles and recommendations for medical care, health care, and living for the elderly from various perspectives, which aroused the international community’s concern about service facilities for the elderly. The high-frequency keywords of FCMNCE research in this stage include care (200 times), mortality (156 times), prevalence (131 times), risk (122 times), risk factor (93 times), and health (69 times) (Table 3). Studies in this phase were divided into two main categories. The first is research on the FCMNCE care effect, which concerns the risk factor of care and the factors related to rehabilitation, where risk factor (0.12), risk (0.08), and mortality (0.08) had higher centrality and valued the safety of service facilities for the elderly. The second category of research during this phase is FCMNCE influencing factors, such as the cost of the facility [50] and expected healthiness, where care (0.09), health (0.06), and cost (0.06) have high centrality. Much of the early research focused on the effectiveness and influencing factors of service facilities for older people, with relatively less research on the health needs of older people.

In terms of the effectiveness of care in geriatric service facilities, it has been suggested that the establishment of geriatric service facilities can reduce healthcare costs for older adults [51], reduce the length of hospital stays [52,53], accelerate functional recovery [54], and improve medical and functional outcomes, among other effects. Torres et al. used a questionnaire to analyse the distribution of home care services in the urban elderly population and found that older, single, and disabled seniors needed more help with services [55]. Rockwood et al. used the example of care for older Canadian mental illness patients and found that innovations between services and long-term care facilities may reduce the need for long-term hospitalisation [52]. Potter found that comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) could increase LTC services for older adults, reducing healthcare costs [51]. It has also been suggested that care facilities increase the risk of malnutrition in older adults [56].

With respect to the influencing factors of elderly service facilities, scholars have analysed existing healthcare facilities for the elderly in terms of cost [50], financing [57], institutional [58], and disaster response [59]. Al-Shammari et al. studied the procedures and constraints of developing healthcare services for the elderly in Saudi Arabia and found that healthcare decision makers are increasingly aware of the cost of healthcare facilities for the elderly, staffing, and priority care recipients [50]. Silverman et al. analysed the response of long-term care for the elderly during climate disasters and provided a plan for other long-term care facilities to cope with climate disasters [60].

In the early stage of FCMNCE research, the core concepts and connotations of “combination of medical and health care” and “elderly service facilities” were not yet unified, and the research only focused on the effects and influencing factors of elderly service facilities. The overall number of publications was relatively small (only 5.86% of the total number of publications), mainly focusing on medical convenience, quality of care, and mortality risk influencing factors in elderly service facility studies. The discussion of combined medical and nursing care facilities had appeared, so this stage can be considered an exploratory phase of influencing factors of FCMNCE research. Although some international organisations and countries proposed policies on ageing during this stage, the overall research was still characterized by fragmented and segmented exploration in terms of the content of literature studies.

3.2.2. The Constructive Phase of Combined Medical and Nursing Care Pattern (1996–2004): Progressive Development and Functional Integration

In this phase, international consensus or national policies were proposed, such as the report Towards an international consensus on policy for long-term care of the ageing (2000), the MIPAA program (2000), Canada’s PRISMA care services (1995), and Japan’s PHBNC model (2000), all focusing on the need for long-term care of the elderly, as well as the quality of life of the elderly. During this stage, researchers realised the importance of elderly care facilities, prompting FCMNCE research to enter the constructive phase of combined medical and nursing care.

The high-frequency keywords included long-term care (70 times), epidemiology (47 times), and service (39 times) (Table 3), among which long-term care and epidemiology had a high centrality (both 0.03) and were the hotspots of research at the time. This phase of study focused on the physical health [61], mental health [62], and the spiritual needs of older adults [63]. Wu et al. found that the main psychological factors influencing older adults’ admission to nursing facilities were positive attitudes toward nursing homes and low independence needs [62]. Johnson et al. showed that alcohol abuse among the elderly might increase the frequency of care facility use [61]. Llewellyn-Jones et al. found that the provision of different levels of care could alleviate mental illness in older people, leading to the implementation of multifaceted shared care interventions for late-life depression. Otsuka et al. called for more appropriate and specialised institutional care interventions to enhance and improve social services for older adults with dementia [64].

Researchers have argued that the health problems of the elderly should be addressed through a combination of medical institutions and elderly care facilities [63]. Nursing care facilities, as a transition between home and hospital care, have been the focus of research in health care in the United States, Italy, the United Kingdom, and Japan [65,66]. Researchers have recognised the importance of long-term care, service, and intervention for medical and nursing care of the elderly. Elderly service facilities can safeguard the rehabilitation process and re-coping with the community life of the elderly [67]. The lack of service facilities for long-term care of the elderly can put additional pressure on emergency and long-term inpatient units for medical beds [65]. Ishizaki et al. analysed the establishment of geriatric intermediate care facilities in Japan (GICF) for nursing care and rehabilitation functions to help hospitalised older people resume their daily lives [66].

During this stage, scholars considered the importance of elderly care facilities and initially proposed combining medical and nursing care facilities. The amount of research literature published began to increase (14.1% of total publications), and the attention of the academic community continued to grow. The research contents and methods in this stage were further expanded, but no definite research on FCMNCE had yet emerged; therefore, this stage can be considered the constructive phase of combined medical and nursing care of FCMNCE research. During this stage, research focus began to shift to the mental health and spiritual needs of the elderly, expanded the service content, and treatment of long-term care in FCMNCE, reflecting the overall characteristics of progressive development and functional integration.

3.2.3. The Improvement Phase of Life Quality (2005–2013): Deepening Cognition and Expanding Methods

During this phase, the UN reports “World Economic and Social Survey (2007)” and “Follow-up to the Second World Assembly on Ageing (2010)” discussed the requirement to integrate ageing into the international development agenda and create an environment suitable for older people. These reports considered the disaggregation of factors such as gender, age, and disability of older adults as essential factors in assessing the health status of older adults. The high-frequency keywords in this phase included prevention (30 times), comorbidity (23 times), and home (21 times), among which the keywords prevention (0.02) and home (0.02) have a high centrality and are the focus of this phase of research. In terms of literature co-citations, during this phase of FCMNCE research, authors began to examine the role of FCMNCE with respect to the quality of life of the elderly, emphasising the connectedness of home and long-term care facilities in FCMNCE. Therefore, this phase constitutes the improvement phase of life quality for FCMNCE research.

Elder care also gradually shifted from the previous phase of research on the relationship between health care and nursing to palliative care [68] and end-of-life care [69], which improve the quality of life of the elderly and prevent and alleviate suffering. Lo et al. studied the divergence of the propensity of nursing facilities to choose palliative care and patients’ wishes [68]. Aaltonen et al. studied care facilities for 75,000 older adults and found that they play an essential role as the primary provider of primary health care and that future emphasis needs to be placed on professionalism in end-of-life patient care [69] and increased awareness training for long-term care of older adults [70].

Home care is a type of FCMNCE. Lim et al. argued that social and family support should be increased before an older person is admitted to a senior care facility, especially for older people with more extended hospital stays and functional loss [71]. Županić et al. analysed the relationship between community health care and home care and argued that community health service facilities should provide necessary assessment for home care with caregiver assistance [72]. Home care modalities for elderly patients with depression [73], elderly patients with stroke [74], and elderly patients with schizophrenia have also been studied [75].

During this period, the number of publications increased rapidly (28.12% of the total literature), and the number of co-citations increased significantly, indicating the rapid increase in research topics. Moreover, the theories and research methods of FCMNCE were improved, reflecting the characteristics of deepening cognition and expanding methods.

3.2.4. The Synergistic Development Phase of Science and Technology (2014 to Present): Multiperspective and Intelligent Development

In this phase, with the further intensification of international ageing, the WHO, ILO, WB, and other organisations continue to propose a series of action frameworks for long-term care and healthy ageing (Table 3), deepening the resource allocation for medical care-oriented elderly services. The main keywords in this stage are Medicare (12 times), meta-analysis (11 times), SARS-CoV-2 (9 times), coronavirus (7 times), and information technology (2 times). FCMNCE studies are diversified, and new technologies and the synergy of multiple perspectives are gradually considered. Research is now focused on both protection against the outbreak of epidemic viruses and the application of intelligent technologies.

Studies have found that mortality from COVID-19 increases with age [76], that older adults are at high risk of coronavirus disease, and that prevention of infection should be a top priority for public health professionals. The government could develop preventive mechanisms to deal with COVID-19 by providing professional training to medical personnel [76] and establishing emergency contacts [77]. Wang et al. found that age, income, occupation, chronic illness, and information technology acceptance affect the demand for healthcare services among older adults [78]. The effects of level-of-care needs [79] and mental illness [80] should be considered when developing long-term care strategies.

The era of big data has led to new technologies and models, such as image recognition [81], meta-analysis [82], and intelligent platforms [83], also being applied in FCMNCE research to build innovative ageing models. Feng introduced image processing technology to construct an intelligent ageing model using techniques such as positioning and monitoring to provide real-time feedback on the living conditions of the elderly [81]. Hussain et al. designed a health emergency service platform based on the medical service needs of the disabled elderly to provide timely medical services to the disabled elderly [83]. Lu et al. studied the effects of exposure to socially assistive robots for patients with dementia and found that pet-based robotic care can alleviate behavioural and psychological symptoms in patients with dementia [84]. Cesari et al. found that the development of FCMNCE needs to consider improvements in the efficiency of resource and information sharing from the perspective of the continuum of care and service synergy [85].

During this period, FCMNCE research has entered a rapid growth phase (51.92% of the overall literature), with the research scope and methods further expanded and the number of publications exhibiting explosive growth. Research on the development mode, improvement strategy, and technical means of FCMNCE has been carried out, reflecting a tendency toward the multiperspective and intellectual development of research; therefore, this stage be considered the synergistic development phase of science and technology of FCMNCE research.

3.3. Analysis of Research Hotspots

3.3.1. Distribution of Research Hotspots Based on Keyword Clustering

Literature keywords, as well as investigator refinement and summarisation of the primary content of articles and word frequency analysis of keywords, are often used in bibliometrics to reveal the distribution of research hotspots [42]. VOSviewer indicates the connection between each key node and research hotspots according to node size, colour and distance of connecting thickness, and density, which can intuitively reflect the relationship between each important node, topic, and keyword [86], generating a straightforward graphical keyword co-occurrence clustering map. Therefore, in this study, data were imported into VOSviewer for keyword co-occurrence analysis to represent the hotspot distribution of FCMNCE research. The minimum threshold of word frequency statistics was set to 60 in VOSviewer, and the top 110 high-frequency keywords were selected to generate a keyword co-occurrence network map (Figure 9) and annual overlap map (Figure 10) of FCMNCE studies.

In the keyword co-occurrence network view (Figure 9), the terms facility, patient, and care had the highest frequencies of 1046, 802, and 681, respectively, and stay, discharge, and skilled nursing facility had the highest relevance (4.75, 4.63, and 3.77, respectively) representing the central core concepts of FCMNCE research. Around these core concepts, other high-frequency keywords based on co-occurrence relationships present four main research clusters. (1) Red: clustered high-frequency words include care, population, need, home, and model, and research is related to elements such as health quality and development conditions. According to word frequency, the research objects focus on the service population, individual, and elderly population; the research mainly focuses on health, quality, and other topics; and the research methods involve information survey and activity access. (2) Green: studies that explore the disease conditions and treatment characteristics of FCMNCE. The high-frequency words are age, hospital, factor, and risk. According to word frequency, the research object involves the hospitalisation of various FCMNCE elements such as elderly patients, women, and morbidity response measures, mainly focusing on skilled nursing facilities and the role of the hospital. (3) Blue: studies exploring the care and diagnosis of various categories of patients. Its high-frequency words include patient, group, treatment, resident, and participant, with a main focus on the relationship between prevalence and long-term care and diagnosis. According to word frequency, research methods are mainly used for measurement, and research objects are mainly focused on resident and patient. (4) Yellow: studies of the combined form of medical and rehabilitation in FCMNCE.

The nodes and connecting lines shown in Figure 10 indicate the evolutionary characteristics of the time dimension of high-frequency words. Although FCMNCE research originated earlier, its high-frequency words mainly appeared after 2010. Before 2010, the high-frequency words included nursing home, resident, and diagnosis, indicating that early FCMNCE studies focused on the actual study of treatment outcomes and drug effects, with more focus on elderly care facilities. With the development of FCMNCE research, focus gradually shifted to gender, health care, mental state, and mental health research, such as education and survey. Since 2014, high-frequency words have become more diverse, with implementation and cross-sectional studies. New concepts and techniques are gradually being applied, and the development of FCMNCE research has been diversified.

Because bibliometric analysis is mainly based on the citation and reciprocity between historical literature and the literature data of recent years can only be reflected in the future period, the centrality of keywords from 2018 to the present (Table 3) is almost 0. The effect of the bibliometric results from 1986 to 2022 on the analysis of recent research hotspots was relatively reduced, and it does not provide complete feedback on the research hotspots in recent years. Therefore, we used the Log-likelihood ratio algorithm to perform keyword analysis on the top 10 research clusters for the period of 2018–2022 in order to grasp the latest research hotspots, as shown in Table 4 and Figure 11, where the base keyword clusters include pain, ageing, health insurance, nursing homes, Beers standard, and HIV. In the past 5 years, the research object of FCMNCE has been further expanded, and the influencing factors have been gradually expanded, with IoT and digital health gradually gaining attention, with a focus on influencing factors closely related to FCMNCE, such as acute care and new coronary pneumonia.

Table 4.

Keyword clustering of FCMNCE research in 2018–2022.

3.3.2. Evolution of Research Hotspots Based on Annual Overlap

The temporal partitioned mapping of keyword co-occurrences and literature co-citations using Citespace can contribute to further analysis of the evolutionary paths of research hotspots. For example, the timeview function, which enables visual analysis of evolutionary paths [45], can reveal the turning time nodes of research and the critical literature of the corresponding period to identify research frontiers [87]. In this study, we used Citespace’s keyword analysis, setting the time slice to 1 year, to analyse the keywords of FCMNCE research between 1986 and 2022 and generated time-zoned axes of research in different periods (Figure 12). The top 10 categories were #0 delirium, #1 China, #2 continuing, #3 ageing, #4 colonisation, #5 COVID-19 pandemic, #6 quality of care, #7 HIV, #8 malnutrition, and #9 elderly care. These include the COVID-19 pandemic, quality of care, HIV, and elderly care. Delirium and the COVID-19 pandemic were studied earlier, with greater importance and a stronger relationship with the rest of the categories, which are hot categories of research. The wide coverage of their keywords indicates that FCMNCE research focuses on geriatric diseases and has been influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic in recent years.

3.3.3. Identification of Research Hotspots Based on Burst Keyword Strength

Keyword burst detection can be used detect the frequency of keywords in research during a specific period, reflecting changes in research hotspots. These “burst” keywords are considered to have particular development potential and research value in this research period [28]. In the FCMNCE research from 1986 to 2022, 50 burst words were detected, and the 20 most frequent keywords were selected for study (Table 5). The research focus and hot areas of FCMNCE were differ significantly depending on the stage. Before 2006, there was less research on theoretical approaches and treatments for FCMNCE, with a main focus on facilities (e.g., nursing facilities, nursing homes, and communities) and diseases of the elderly. From 2006 to 2010, research was extended to rehabilitation, long-term care, and quality of life, with a gradual increase in focus on the service quality of FCMNCE. From 2011 to 2015, FCMNCE research focused increasingly on treatments, such as polypharmacy and emergency departments. From 2016 to the present, health care, the COVID-19 pandemic, meta-analysis, and other background and analysis methods have become popular topics.

Table 5.

Top 20 burst keywords for FCMNCE research, 1986–2022.

Therefore, we further analysed the keywords of the last 5 years (2018–2022) to provide accurate feedback on the research hotspots of FCMNCE in recent years. As shown in Table 6, coronavirus, primary care, ageing, and rehabilitation are the emerging research hotspots in recent years.

Table 6.

Burst keyword strength and timing of FCMNCE research in 2018–2022.

3.4. FCMNCE Research Trend Forecast

The bibliometric data on keyword clustering, annual overlap, and keyword emergent intensity for 1986–2022 are analysed in Section 3.3. In terms of keyword clustering, FCMNCE research has four research clusters focusing on the quality of health for older people, disease treatment, care and diagnosis, and postoperative treatment and rehabilitation. A total of 10 research hotspots emerged in the last five years, including pain, ageing, health insurance, Internet of Things, and digital health. In terms of annual overlap, 10 research hotspots in elderly care were identified, such as delirium, the COVID-19 pandemic, and quality of care. In terms of keyword prominence intensity, 10 emerging research hotspots, such as coronavirus, primary care, ageing, and rehabilitation, were found to have emerged in recent years. Combined with the findings presented in Section 3.3, we predict three research trends in future FCMNCE research: smart elderly facilities, smart medical services, and public health risks.

3.4.1. Research Trends in Smart Facilities for the Elderly

As shown in the bibliometric results presented in “3.3 Analysis of research hotspots”, the keywords telemedicine (2014), acceptability (2019), and information technology (2020), which appeared after 2014, have a high strength and indicate a focus on smart elderly facilities, representing a research trend of FCMNCE research in recent years.

The smart city concept and Internet technology have introduced new ideas with respect to the construction of elderly service facilities by providing convenient, timely, and diversified elderly care services on smart elderly care platforms [88]. The use of information technology in FCMNCE research has been approached [89] in terms of improving telecare [83], smart assistive devices [90], and socialisation [91], for example, by developing a health emergency service platform to provide timely medical services to the elderly with disabilities [63,69] and designing a smart geriatric care network platform to help the elderly overcome their loneliness [91]. Moreover, various intelligent robots dedicated to serving the elderly have emerged [92], such as companion and telepresence robots. In the future, FCMNCE research should focus on the development of national-level smart senior care platforms and interactive smart service facilities for the elderly.

3.4.2. Research Trends in Smart Medical Services

As demonstrated by the bibliometric results presented in “3.3 Research hotspot analysis”, the keywords that appeared after 2016, such as avoidable hospitalisation (2022), geriatric syndrome (2022), meta-analysis (2016), and e-health (2022), have a high strength, reflecting a focus on smart healthcare services, representing a research trend in recent years.

Virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and mixed reality (MR) technologies are introducing new research approaches to the field of smart health care by changing the ways in which people collaborate with real and virtual objects. In recent years, virtual and augmented reality have provided significant benefits to the healthcare industry [93], helping to detect early signs of schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s. X-reality (XR) technology is a comprehensive reality technology created through a combination of VR, AR, and MR, providing a new way to remotely monitor patient progress [94] and reduce the distance of care for the elderly [93]. XR builds virtual rehabilitation environments that are motivating, task-oriented, and controllable to facilitate patient recovery [95]. Future FCMNCE research should explore the combination of artificial intelligence, wearable sensors, gaming, augmented reality, and virtual reality to achieve real-time monitoring, remote interaction, and telemedicine for the elderly in a virtual area.

3.4.3. Research Trends in Public Health Risks

The bibliometric results presented in “Section 3.3 Analysis of research hotspots” show that the keywords coronavirus (2020), social isolation (2020), and public health (2020), which appeared after 2013, have a high strength, indicating concern for public health risks and representing a research trend in recent years.

Major public health events such as the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrate the importance of public health. Outbreaks test not only public health but also pose new challenges with respect to communication, treatment services, and frequency of use in healthcare facilities. Everitt et al. studied communication with patients during the COVID-19 pandemic and found that frequent use of digital communication and increased palliative treatment may improve the end-of-life experience of patients with the COVID-19 and reduce the risk of transmission [96]. The development of available palliative care counselling services is essential with respect to planning responses to events such as the COVID-19 pandemic [97].

The COVID-19 pandemic has made it possible to significantly reduce the frequency of use of healthcare facilities by the elderly. Future FCMNCE development can include lower-level medical institutions, such as pharmacies, physicians’ offices, and hospital outpatient clinics [98], to improve the ability of FCMNCE to address unexpected public health risks with respect to all aspects, representing a future trend of FCMNCE research.

4. Discussion

Based on the above analysis of the literature distribution characteristics, development stages, research hotspots, and trends in FCMNCE research, the following three aspects were identified with respect to future priority research contents.

- (1)

- Improving the theoretical system of FCMNCE research

The aim of healthy ageing is to develop and maintain the functions required for the healthy living of all older people. From the perspective of the life course of the elderly, the needs of the elderly for combined medical and nursing care services vary considerably according to their health status and self-care status, and many factors influence their demand for services. Positivism is the philosophical underpinning of modern scientific research [99]. Analysis of the WOS search results shows that researchers in various countries have produced numerous research results on FCMNCE since 1986 (1433 articles). However, most outcomes have adopted the interpretive case study paradigm (1390 articles), and there is a relative lack of research based on the positivist mathematical and statistical paradigm (only 43 articles). In future studies, research methods that combine qualitative and quantitative analysis can be explored [100] to more comprehensively perceive the dialectical relationship between the needs of the elderly and FCMNCE.

FCMNCE can also be integrated into the framework of higher system-level urban theories such as resilient cities, urban risk governance, and low-carbon cities, and systematic research can be conducted on the planning and architectural design strategies, assessment methods, management and maintenance models, staffing, service grading, funding, and legal protection of FCMNCE from the perspective of the overall city. In this way, the FCMNCE theoretical system can be progressively improved.

- (2)

- Emphasis on the application of intelligent technology in FCMNCE

The smart city is the ultimate form of the urban informatisation process, emphasising the promotion of urban development through the informatisation process and the extensive application of information technology to make the city connected, interconnected, and intelligent [101]. Through the integrated application of intelligent computing technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), cloud computing, big data, and spatial geographic information integration, key infrastructure components and services comprising cities such as urban management, education, health care, real estate, transportation, utilities, and public safety can be made more connected, efficient, and intelligent.

From the complex systems perspective, FCMNCE can be considered a class of medical subsystems of smart cities, whereby the high-speed interconnection of information and matter is the basis for operation. First, future FCMNCE research can explore the construction of a government-led national medical information service centre based on big data, cloud computing, and other information technologies. Such a centre can have composite functions, such as medical diagnosis, graded referral, health management, telemedicine, early warning monitoring, and public feedback announcement, analysing and sharing health data of the elderly between regions and institutions across the country. Second, future FCMNCE research can focus on intelligent terminals and their human–machine interaction, as well as the application of technical means such as Internet+ [102] and IoT [103]. The three types of intelligent terminals in institutions, communities, and homes can be used to realize the contents of daily medical care services for the elderly, such as telemedicine, daily monitoring, medication purchase, and information pushing, in order to meet the needs of the elderly groups in the three types of combined medical care models: institutional, community, and home care. In this way, telemedicine, daily monitoring, drug purchase, information push, and other daily medical care services for the elderly can be realised to meet the needs of the elderly population in institutions, communities, and homes.

- (3)

- Exploring the governance mechanisms, strategies, and technical tools of FCMNCE to address unexpected public health risks

In the Oxford Handbook of Public Health Practice, Pencheon et al. define “risk” as the probability that a particular adverse event or challenge will occur within a specified period [104]. “Risk governance” refers to the institutional structures and policy processes that guide and constrain the collective activities of a group, society, or the international community to regulate, reduce, or control risk issues [105]. With the background of the COVID-19 epidemic sweeping the world, how to deal with sudden urban public health risks, such as infectious diseases, public environmental pollution, and food safety, is expected to constitute critical research contents of FCMNCE in the future.

In follow-up study, first, a sustainable government-led healthcare service system for the elderly can be established and improved, and a risk governance mechanism for FCMNCE can be formed through the effective integration of urban healthcare resources. Secondly, the risk assessment system of FCMNCE can be explored, including the proposal of a risk assessment system and the development of grading standards for medical and nursing care. Thirdly, the FCMNCE regulatory model, which is government-based and supplemented by third-party institutions, can be improved, and we recommended that regulatory laws be enacted to improve the effectiveness of enforcement.

5. Conclusions

Based on a bibliometric analysis conducted with Citespace and VOSviewer, we analysed the literature distribution characteristics, development stages, research hotspots, and trends in FCMNCE research. Here, we present our research conclusions, with the aim of providing reference and guidance for theoretical research and practice of FCMNCE.

- (1)

- Literature distribution characteristics

We found that FCMNCE research shows a distinctive distribution of literature in four areas: “volume of publications”, “discipline distribution”, “publication sources”, and “country and time zone”. We observed a continuous increase in the number of publications and the degree of disciplinary integration, with a focus on ageing, health services, and public health elements, as well as a predominance of research findings from the USA, Canada, Japan, Australia, and China.

- (2)

- Research phases and characteristics

FCMNCE research can be divided into four phases: the exploration of influencing factors, the construction of combined medical and nursing care patterns, the enhancement of life quality, and the synergistic development of science and technology. In terms of literature and discipline distribution, research hotspots and priorities show four characteristics: “fragmented and segmented exploration”, “progressive development and functional integration”, “deepening cognition and expanding methods”, and “multiperspective and intelligent development”.

- (3)

- Research hotspots

According to the bibliometric analysis based on keyword clustering, annual overlap, and keyword emergence, the research hotspots of FCMNCE are “coronavirus”, “ageing”, “primary care”, “IoT”, and “digital health”.

- (4)

- Research trends

Through the analysis of literature distribution characteristics, research phases, and hotspots, we identified three trends in FCMNCE research: smart facilities for the elderly, smart medical services, and public health risks. We argue that future research priorities for FCMNCE should include the improvement of the theoretical system, a deepening of intelligent technology application methods, and development of governance strategies to deal with sudden public health risks.

With the continuous increase in the proportion of the elderly population aged 65 and older in all countries [106], FCMNCE is expected to evolve from initial market demand to a social problem, requiring effective integration, planning, and design of public social resources from a multidisciplinary perspective. The four analytical conclusions with respect to FCMNCE research presented in this paper are based on the bibliometric analysis method, which can help researchers from varied professional backgrounds to deeply understand its development context, research hotspots, and research trends and provide references and suggestions for subsequent research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation and writing, Z.C.; methodology and funding acquisition, Q.Y.; audit and data visualisation, N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Social Science Foundation of Beijing, China, under grant No. 18GLA002.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Nomenclature

| CGA | Comprehensive geriatric assessment |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| FCMNCE | Facilities of combined medical and nursing care for the elderly |

| GICF | Geriatric intermediate care facilities |

| ILO | International Labour Organization |

| IoT | The Internet of Things |

| MIPAA | The Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing |

| NHS | National Health Service |

| PACE | Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly |

| PHBNC | Plan of Home-Based Nursing Care |

| PRISMA | Program of Research to Integrate Services for the Maintenance of Aytonomy |

| SSD | Social Service Department |

| UN | United Nations |

| VOS | VOSviewer |

| WB | The World Bank |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WOS | Web of Science |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Bibliometric analysis softwares used to produce Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12.

| Figure 7 | Generated using Citespace software |

| Figure 8 | Generated using Citespace software |

| Figure 9 | Generated using VOSviewer software |

| Figure 10 | Generated using VOSviewer software |

| Figure 11 | Generated using Citespace software |

| Figure 12 | Generated using Citespace software |

References

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Towards an International Consensus on Policy for Long-Term Care of the Ageing; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, J.R.; Officer, A.M.; Cassels, A.K. The World Report on Ageing and Health. Gerontologist 2016, 56, S163–S166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chunyan, Y.; Hanwen, Z.; Mei, Y. Analysis on the Model of the Combination of Medical and Health Care from the Perspective of Aging. Russ. Fam. Dr. 2020, 24, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H. Research on the Supply and Demand of Long-Term Care for Disabled Elderly in Hohhot Under the Background of Combination of Medical Care and Nursing. Stud. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2022, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, G. Discussion on space type and adaptability development of medical and nursing combined facilities: Taking Beijing Area as an Example. J. Archit. 2018, S1, 29–33. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Integration of Health Care Delivery. Report of a WHO Study Group; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Grone, O.; Garcia-Barbero, M. Integrated Care: A Position Paper of the WHO European Office for Integrated Health Care Services. Int. J. Integr. Care 2001, 1, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodner, D.L.; Spreeuwenberg, C. Integrated Care: Meaning, Logic, Applications, and Implications—A Discussion Paper. Int. J. Integr. Care 2002, 2, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlee, F. Integrated Care Is What We All Want. BMJ 2012, 344, e3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirth, V.; Baskins, J.; Dever-Bumba, M. Program of All-Inclusive Care (PACE): Past, Present, and Future. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2009, 10, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, D.L.; Temkin-Greener, H.; Kunitz, S.; Mukamel, D.B. The Growing Pains of Integrated Health Care for the Elderly: Lessons from the Expansion of PACE. Milbank Q. 2004, 82, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trnobranski, P.H. Implementation of Community Care Policy in the United Kingdom: Will It Be Achieved? J. Adv. Nurs. 1995, 21, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawamura, K.; Nakashima, T.; Nakanishi, M. Provision of Individualized Care and Built Environment of Nursing Homes in Japan. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 56, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macadam, M. PRISMA: Program of Research to Integrate the Services for the Maintenance of Autonomy. A System-Level Integration Model in Quebec. Int. J. Integr. Care 2015, 15, e018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN. First World Assembly on Ageing, Vienna 1982. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/conferences/ageing/vienna1982 (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- United Nations. Principles for Older Persons; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Proclamation on Ageing; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dening, T.; Barapatre, C. Mental Health and the Ageing Population. Br. Menopause Soc. J. 2004, 10, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madrid Plan of Action and Its Implementation|United Nations for Ageing. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/ageing/madrid-plan-of-action-and-its-implementation.html (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- UN. Follow-Up to the 2nd World Assembly on Ageing. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/688656 (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/186463 (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 978-92-4-151350-0. [Google Scholar]

- Laura, A.; Umberto, C.; Valeria, E.; Isabel, V. Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Glinskaya, E.; Feng, Z. Options for Aged Care in China: Building an Efficient and Sustainable Aged Care System|Policy Commons. Available online: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1277245/options-for-aged-care-in-china/1865748/ (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- World Health Organization. Integrated Care for Older People: Guidelines on Community-Level Interventions to Manage Declines in Intrinsic Capacity; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-92-9061-900-0. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Decade of Healthy Ageing: Development of a Proposal for a Decade of Healthy Ageing 2020–2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Follow-Up to the International Year of Older Persons: 2nd World Assembly on Ageing. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/799864 (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Li, B.; Huang, L. Research on the Type System and Design Standards of Elderly Facilities. J. Archit. 2011, 12, 81–86. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Elers, P.; Hunter, I.; Whiddett, D.; Lockhart, C.; Guesgen, H.; Singh, A. User Requirements for Technology to Assist Aging in Place: Qualitative Study of Older People and Their Informal Support Networks. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e10741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, C.; Barnes, S.; Mckee, K.; Morgan, K.; Torrington, J.; Tregenza, P. Quality of Life and Building Design in Residential and Nursing Homes for Older People. Ageing Soc. 2004, 24, 941–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceros, J.C.; Pols, J.; Domènech, M. Where Is Grandma? Home Telecare, Good Aging and the Domestication of Later Life. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 93, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuboshima, Y.; McIntosh, J.; Thomas, G. The Design of Local-Authority Rental Housing for the Elderly That Improves Their Quality of Life. Buildings 2018, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.S.; Chung, J.H.; Kim, B.S.; Kim, J. A Study on Modular-Based Prototypes for the Elderly Housing. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2017, 23, 10440–10444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postindoz, Z.D.; Moosavi, M.S. Evaluation of Spatial Quality in Elderly Housing Facilities. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Li, Q. The Construction of Family-Oriented Living Units in Special Care Orphanages for the Elderly. J. Archit. 2010, 03, 46–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sumita, K.; Nakazawa, K.; Kawase, A. Long-Term Care Facilities and Migration of Elderly Households in an Aged Society: Empirical Analysis Based on Micro Data. J. Hous. Econ. 2021, 53, 101770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckenwiler, L. Displacement and Solidarity: An Ethic of Place-Making. Bioethics 2018, 32, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D.C.; Grey, T.; Kennelly, S.; O’Neill, D. Nursing Home Design and COVID-19: Balancing Infection Control, Quality of Life, and Resilience. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 1519–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eijkelenboom, A.; Verbeek, H.; Felix, E.; van Hoof, J. Architectural Factors Influencing the Sense of Home in Nursing Homes: An Operationalization for Practice. Front. Archit. Res. 2017, 6, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alders, P.; Schut, F.T. Trends in ageing and ageing-in-place and the future market for institutional care: Scenarios and policy implications. Health Econ. Policy Law 2019, 14, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Science Mapping: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Data Inf. Sci. 2017, 2, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, N.; Yao, Q.; Shen, Q. A Review of Human Settlement Research on Climate Change Response under Carbon-Oriented: Literature Characteristics, Progress and Trends. Buildings 2022, 12, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Yan, E.; Cui, M.; Hua, W. Examining the Usage, Citation, and Diffusion Patterns of Bibliometric Mapping Software: A Comparative Study of Three Tools. J. Informetr. 2018, 12, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. CiteSpace II: Detecting and Visualizing Emerging Trends and Transient Patterns in Scientific Literature. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2006, 57, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2009, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Koutra, S.; Zhang, J. Zero-Carbon Communities: Research Hotspots, Evolution, and Prospects. Buildings 2022, 12, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.W. Mapping Scientific Frontiers: The Quest for Knowledge Visualization. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2004, 55, 363–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, Y. Searching for Clinical Evidence in CiteSpace. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2005, 2005, 121–125. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shammari, S.A.; Felemban, F.M.; Jarallah, J.S.; Ali, E.-S.; Al-Bilali, S.A.; Hamad, J.M. Culturally Acceptable Health Care Services for Saudi’s Elderly Population: The Decision-Maker’s Perception. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 1995, 10, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, J.F. Comprehensive Geriatic Assessment in the Outpatient Setting: Population Characteristics and Factors Influencing Outcome. Exp. Gerontol. 1993, 28, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockwood, K.; Stolee, P.; Brahim, A. Outcomes of Admission to a Psychogeriatric Service. Can. J. Psychiatry 1991, 36, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, A.L.; Bygren, L.O. Efficacy of the Rehabilitation of Elderly Primary Health Care Patients After Short-Stay Hospital Treatment. Med. Care 1992, 30, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, E.; Lum, C.; Woo, J.; Or, K.; Kay, R.L. Outcomes of Elderly Stroke Patients. Stroke 1995, 26, 1616–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, H.A.; Kabir, Z.N.; Winblad, B. Distribution of Home Help Services in an Elderly Urban Population: Data from the Kungsholmen Project. Scand. J. Soc. Welf. 1995, 4, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstetter, J.E.; Holthausen, B.A.; Fitz, P.A. Malnutrition in the Institutionalized Older Adult. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1992, 92, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Reich, M.R. Health Care Financing for the Elderly in Japan. Soc. Sci. Med. 1993, 37, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soh, G. Medical Care for Institutionalised Elderly People in Singapore. Aust. J. Public Health 1992, 16, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States. Lessons Learned from Hurricane Andrew; U.S. G.P.O.: Washington, WA, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0-16-041020-8. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, M.A.; Weston, M.; Llorente, M.; Beber, C.; Tam, R. Lessons Learned from Hurricane Andrew: Recommendations for Care of the Elderly in Long-Term Care Facilities. South Med. J. 1995, 88, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, I. Alcohol Problems in Old Age: A Review of Recent Epidemiological Research. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2000, 15, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.M.S.; Tang, C.S.; Yan, E.C. Psychosocial Factors Associated With Acceptance of Old Age Home Placement: A Study of Elderly Chinese in Hong Kong. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2004, 23, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn-Jones, R.H.; Baikie, K.A.; Castell, S.; Andrews, C.L.; Baikie, A.; Pond, C.D.; Willcock, S.M.; Snowdon, J.; Tennant, C.C. How to Help Depressed Older People Living in Residential Care: A Multifaceted Shared-Care Intervention for Late-Life Depression. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2001, 13, 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, T. Current Status of and Challenges for Dementia in Japan. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1998, 52, S300–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, A.; Clinch, D.; Groarke, E.P. Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment in the Hospitalized Elderly. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1997, 12, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaki, T.; Kobayashi, Y.; Tamiya, N. The Role of Geriatric Intermediate Care Facilities in Long-Term Care for the Elderly in Japan. Health Policy 1998, 43, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloush-Kleinman, V.; Schneidman, M. System Flexibility in the Rehabilitation Process of Mentally Disabled Persons in a Hostel That Bridges between the Hospital and the Community. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2003, 40, 274–282. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, R.S.K.; Kwan, B.H.F.; Lau, K.P.K.; Kwan, C.W.M.; Lam, L.M.; Woo, J. The Needs, Current Knowledge, and Attitudes of Care Staff Toward the Implementation of Palliative Care in Old Age Homes. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2010, 27, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaltonen, M.; Forma, L.; Rissanen, P.; Raitanen, J.; Jylhä, M. Transitions in Health and Social Service System at the End of Life. Eur. J. Ageing 2010, 7, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, M.; Boaz, T.; Andel, R.; DeMuth, A. Predictors of Avoidable Hospitalizations Among Assisted Living Residents. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2012, 13, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, E.S. Predictors of Nursing Home Admission: A Social Work Perspective. Aust. Soc. Work 2009, 62, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Županić, M.; Kovačević, I.; Krikšić, V.; Županić, S. Everyday Needs and Activities of Geriatric Patients—Users of Home Care. Period. Biol. 2013, 115, 575–580. [Google Scholar]

- Houtjes, W.; van Meijel, B.; Deeg, D.J.H.; Beekman, A.T.F. Unmet Needs of Outpatients with Late-Life Depression; a Comparison of Patient, Staff and Carer Perceptions. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 134, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sandel, M.E.; Terdiman, J.; Armstrong, M.A.; Klatsky, A.; Camicia, M.; Sidney, S. Postacute Care and Ischemic Stroke Mortality: Findings From an Integrated Health Care System in Northern California. PMR 2011, 3, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, A.O.; Bartels, S.J.; Xie, H.; Peacock, W.J. Increased Risk of Nursing Home Admission Among Middle Aged and Older Adults With Schizophrenia. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 17, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska-Polańska, B.; Sarzyńska, K.; Pytel, A.; Izbiański, D.; Gaweł-Dąbrowska, D.; Knysz, B. Elderly Patient Care: A New Reality of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Aging Dis. 2021, 12, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopetti, M.; Santurro, A.; Tartaglia, R.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. Expanding Frontiers of Risk Management: Care Safety in Nursing Home during COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2021, 33, mzaa085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; An, X.; Li, G.; Xue, L.; Wu, X.; Gong, X. Situation of Integrated Eldercare Services with Medical Care in China. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 83, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-R.; Otsubo, T.; Imanaka, Y. The Effects of Dementia and Long-Term Care Services on the Deterioration of Care-needs Levels of the Elderly in Japan. Medicine 2015, 94, e525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexopoulos, P.; Novotni, A.; Novotni, G.; Vorvolakos, T.; Vratsista, A.; Konsta, A.; Kaprinis, S.; Konstantinou, A.; Bonotis, K.; Katirtzoglou, E.; et al. Old Age Mental Health Services in Southern Balkans: Features, Geospatial Distribution, Current Needs, and Future Perspectives. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, C. Research on Mathematical Model of Smart Service for the Elderly in Small- and Medium-Sized Cities Based on Image Processing. Sci. Program. 2021, 2021, e1023187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twiss, M.; Hilfiker, R.; Hinrichs, T.; de Bruin, E.D.; Rogan, S. Effectiveness of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions to Prevent Falls and Fall-Related Fractures in Older People Living in Residential Aged Care Facilities—A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis Protocol. Phys. Ther. Rev. 2019, 24, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Wenbi, R.; da Silva, A.L.; Nadher, M.; Mudhish, M. Health and Emergency-Care Platform for the Elderly and Disabled People in the Smart City. J. Syst. Softw. 2015, 110, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.-C.; Lan, S.-H.; Hsieh, Y.-P.; Lin, L.-Y.; Lan, S.-J.; Chen, J.-C. Effectiveness of Companion Robot Care for Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Innov. Aging 2021, 5, igab013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesari, M.; Sumi, Y.; Han, Z.A.; Perracini, M.; Jang, H.; Briggs, A.; Thiyagarajan, J.A.; Sadana, R.; Banerjee, A. Implementing Care for Healthy Ageing. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e007778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hu, Z.; Liu, S.; Tseng, H. Emerging Trends in Regenerative Medicine: A Scientometric Analysis in CiteSpace. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2012, 12, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Searching for Intellectual Turning Points: Progressive Knowledge Domain Visualization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101 (Suppl. S1), 5303–5310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, S. The Design of Caring Environments and the Quality of Life of Older People. Ageing Soc. 2002, 22, 775–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Construction for the Smart Old-Age Care in an Age of Longevity: A Literature Review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 632, 052042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaoui, M.; Lewkowicz, M. A LivingLab Approach to Involve Elderly in the Design of Smart TV Applications Offering Communication Services. In Online Communities and Social Computing; Ozok, A.A., Zaphiris, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 325–334. [Google Scholar]

- Bothorel, C.; Lohr, C.; Thépaut, A.; Bonnaud, F.; Cabasse, G. From Individual Communication to Social Networks: Evolution of a Technical Platform for the Elderly. In Toward Useful Services for Elderly and People with Disabilities; Abdulrazak, B., Giroux, S., Bouchard, B., Pigot, H., Mokhtari, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Shishehgar, M.; Kerr, D.; Blake, J. The Effectiveness of Various Robotic Technologies in Assisting Older Adults. Health Inform. J. 2019, 25, 892–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, T.A.; Dar, T.R.; Sofi, S. A Data-Centric Artificial Intelligent and Extended Reality Technology in Smart Healthcare Systems. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2022, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Market Research Reports & Consulting|Grand View Research, Inc. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/ (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Wurst, S. Extended Reality in Life Sciences and Healthcare. Available online: https://medium.datadriveninvestor.com/extended-reality-in-life-sciences-and-healthcare-3780d06f8cac (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Everitt, R.; Wong, A.K.; Wawryk, O.; Le, B.; Yoong, J.; Pisasale, M.; Mendis, R.; Philip, J. A Multi-Centre Study on Patients Dying from COVID-19: Communication between Clinicians, Patients and Their Families. Intern. Med. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.M.; Leedy, D.J.; Klafter, J.A.; Zhang, Y.; Secrest, K.M.; Osborn, T.R.; Cheng, R.K.; Judson, S.D.; Merel, S.E.; Mikacenic, C.; et al. Clinical Presentation, Complications, and Outcomes of Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients in an Academic Center with a Centralized Palliative Care Consult Service. Health Sci. Rep. 2021, 4, e423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, T.; Matsushima, M. The Ecology of Medical Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Japan: A Nationwide Survey. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 1211–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorland, B. Empiricism, Rationalism and Positivism in Library and Information Science. J. Doc. 2005, 61, 130–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C.; Teddlie, C.B. Mixed Methodology: Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-7619-0071-9. [Google Scholar]

- Albino, V.; Berardi, U.; Dangelico, R.M. Smart Cities: Definitions, Dimensions, Performance, and Initiatives. J. Urban Technol. 2015, 22, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatouillat, A.; Badr, Y.; Massot, B.; Sejdic, E. Internet of Medical Things: A Review of Recent Contributions Dealing With Cyber-Physical Systems in Medicine. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 3810–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanella, A.; Bui, N.; Castellani, A.; Vangelista, L.; Zorzi, M. Internet of Things for Smart Cities. IEEE Internet Things J. 2014, 1, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencheon, D.; Guest, C.; Melzer, D.; Muir Gray, J.; Korkodilos, M.; Wright, J.; Tiplady, P.; Gelletlie, R. Oxford Handbook of Public Health Practice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Renn, O.; Walker, K. Global Risk Governance: Concept and Practice Using the IRGC Framework; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 20 November 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).