1. Introduction

Second homes have their origins in ancient societies [

1], and their meaning has evolved in different regions and cultures. In many countries, people buy second homes to reach geographic and cultural attractions that are not available in their primary residential areas. Main drivers that push people to have a second home include seeking diverse nature such as wanting to be in natural surroundings, looking for an authentic lifestyle in the countryside, or those who want to relax and take a walk by the sea/lake excursion places [

2]. Second homes are used by many people, not just the elite, as vacation and weekend getaways in Scandinavian countries, probably due to widespread prosperity and the abundance of space [

3]. Similarly, second homes in high-altitude areas are still used by many people in countries such as Turkey as a part of their culture to escape the hot weather during the summer months. Thus, second homes have increasingly gained an international dimension due to globalization and the blurring of borders between countries [

4].

Partly because of wealth and plenty of space, many Nordic people have a second home in the countryside (Finnish ‘mökki’, Swedish ‘stuga’, Norwegian ‘hytte’, Danish ‘sommerhus’). In the Scandinavian region, for example, many people continue to use the second homes inherited from their ancestors as an expression of their identity [

5]. One of the common features of Nordic second homes is their internationalization as a result of the European integration process, where Norway, Sweden, and Finland have become mutually attractive second home markets for their closest European Union member states such as Germany [

6]. Largely, but not exclusively, a middle-class phenomenon, second homes come in several varieties, and are inhabited during holidays and the occasional weekend. The important formal research of Wolfe [

7] on summer cottage owners and residents in Ontario in the early 50s was a classic study of second home migration. Similar studies of summer domestic travel to second homes were also conducted in Scandinavia at the same time (e.g., [

8,

9,

10]). Scandinavia already had a strong tradition in second home development, and after World War II, there was a boom in cottage construction, especially in coastal and mountainous areas [

11].

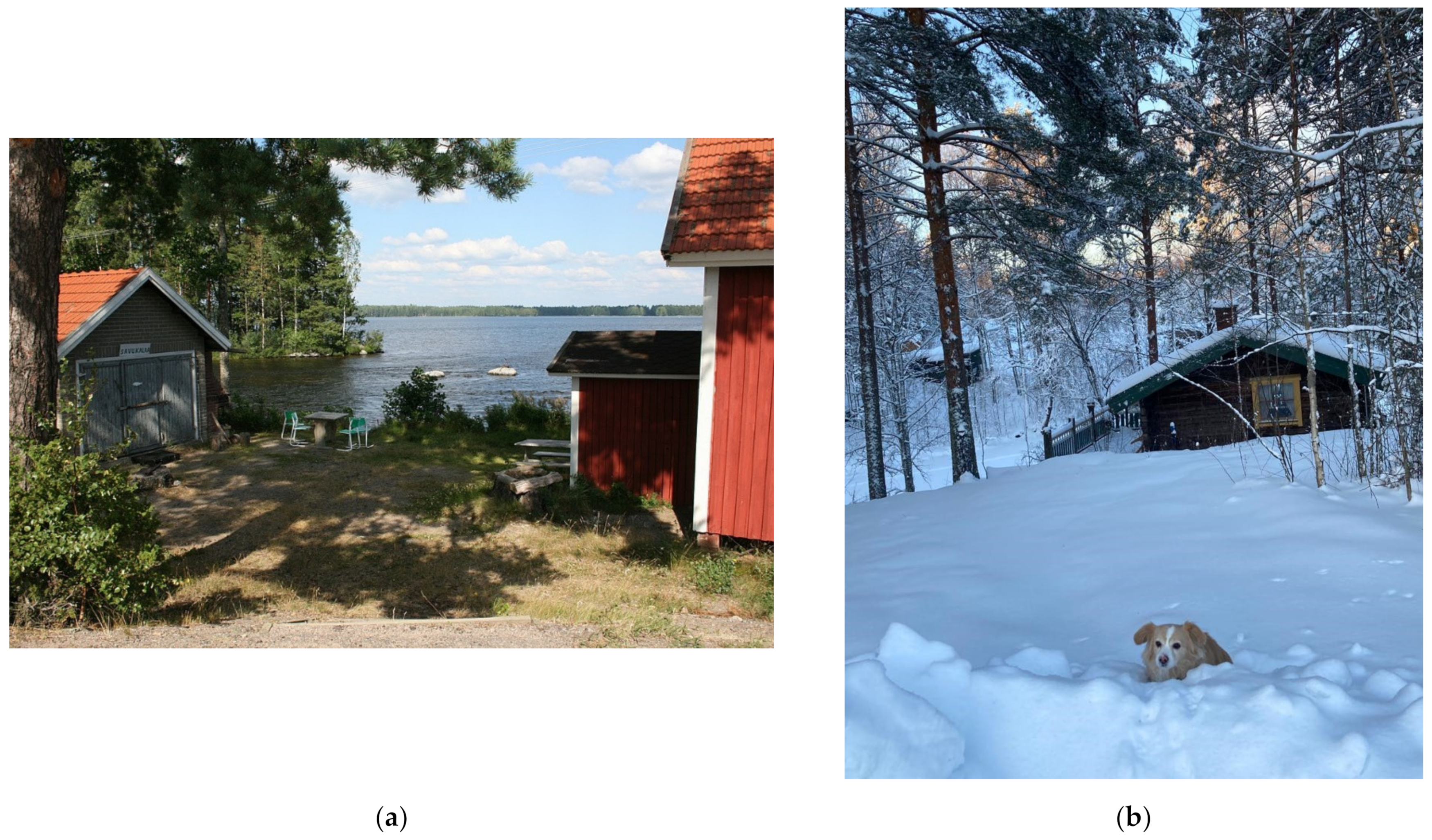

Overall, the northern lifestyle is strongly tied to nature and to the changing seasons of the year, where summer is short and awaited [

12]. For Finns, an ideal way to spend these months is by a lake, surrounded by nature, at their cottage and sauna (see

Figure 1) [

13]. A lakeside cottage is a cliché of Finnish culture and an essential part of the Finnish national landscape. Moreover, the cottage is based on the same basic traditions of the Finnish way of life [

14]. Culturally, the cottage has been considered appropriate for Finns, in a country where nature and rural life are valued [

15]. The purpose of the cottage for many is the balance it offers to urban life, whether it is the relaxing effect of the cottage setting or rural nostalgia [

16].

‘Cottage’ is the closest translation to the Finnish word ‘mökki’, which is widely applied in colloquial and official contexts and has strong cultural value to Finns. The term entails a variety of meanings from a luxurious villa to a humble shack. Statistics Finland [

17] defines ‘cottage’ as a residential building used as a holiday or leisure residence and built permanently on its site (see

Figure 2). This definition does not include holiday homes serving business purposes, buildings in holiday villages, or allotment garden cottages. The term summer cottage is common in Finnish and is broadly understood, though literally it refers only to seasonal residences used during the summer months and is often associated with modest occupancy. In addition, terms such as holiday home are used, particularly in more formal contexts, and these terms are not function-independent concepts but refer to their use in leisure and holidays.

Additionally, the second home or second residence is a common and current concept that does not as a term limit the use of the home exclusively for leisure or a particular time of the year. The secondary residence is increasingly used as a parallel term for the cottage. Second homes and secondary housing are referred to in studies of leisure housing and the media, but often with varying definitions [

18,

19]. The second home can be understood as an additional residence alongside the primary home. However, in this paper, the term second home or residence is used to refer to the especially well-equipped year-round cottage. According to the report on Rural Housing Systems and structures in Norway, Sweden, and Finland, countries generally show an active pattern when it comes to the use of assessment; Finland reports second homes being used an average of 75 days, Sweden 71 days, and Norway 47 days per year [

20]. However, there are main regional differences in the frequency of use for second homes. The standard of the second home is of great significance, such as whether it can be used year-round and where it is located. The vast majority of second homes, over 80%, in all three countries are purposeful. In addition, there is a link between housing sparseness and the degree to which formerly permanent residences are converted to second homes. For example, in Norway, more than half of second homes in the rural policy area were formerly permanent residences, which indicates that it is more usual for permanent homes to be second homes in rural areas where the overall demand for housing is weak [

20].

In Finland, second homes play an important role in displaying the country’s cultural landscape [

21], reflecting the importance of outdoor recreation and ‘traditional’ activities [

22]. Research has shown that second homes are highly valued by a large segment of Finnish society [

23]. In addition, the second home for rural municipalities plays an important role in the local economy and has significant business potential in Finland [

18]. Second homes and tourism potential are an established part of leisure in many countries and have also long been the subject of academic research [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Overall, as in the case of Finland, the cross-border and international second housing is a worldwide phenomenon and is growing in popularity as people seek more desirable environments than ever before [

31]. Moreover, in the Finnish and international context, it was emphasized that second homes are not only an important part of people’s leisure pursuits but also all life cycles and lifestyles [

32,

33].

Urbanization and concentration trends have been changing, and the importance of residential properties and housing conditions has increased significantly during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic [

34,

35]. In the post-pandemic environment, people have started to prefer low-density urban housing and new communities rather than high-density urban centers [

36]. In this sense, this pandemic is the latest social problem to affect the meaning of the ‘second home’ concept, and in its early stages, second homeowners considered them as an escape from urban areas where the virus was spreading faster [

37]. Soon after the outbreak of the pandemic and the closure of schools, offices, shops, and restaurants, people began to flee to their second homes as a safer and more meaningful place of isolation. Therefore, second home use has been extended from leisure and tourism purposes to ‘protection from pandemics’ and ‘a place for privileged remote work’ [

38]. The influx of the urban population to their second homes in Russia and Turkey, the UK, and France highlight the importance of second homes as lower risk locations away from places of infection and for self-isolation [

39,

40,

41]. Additionally, during the COVID-19 pandemic, as many national borders were closed and/or regulated, the main emphasis focused on domestic travel and tourism. Second homes have become a more important form of domestic tourism in many countries, especially Scandinavia, Southern Europe, Russia, North America, Australia, and New Zealand, where a significant proportion of people have had access to a second home, often in rural areas, during the pandemic [

42]. Moreover, outdoor spaces such as gardens and balconies attached to residences may have encouraged leisure activities, e.g., gardening, which was useful for well-being during the pandemic [

43,

44,

45]. Therefore, these critical changes in lifestyle and new demands increase the importance of research on cottage phenomena.

In this study, a cottage or holiday home refers to a residence separate from the primary residence that is mainly used for recreation and apart from the dense urban structure unless stated otherwise. The terms do not take into account the size of the building, the level of equipment, or the extent of use in different seasons, and do not limit the use of the dwelling purely for holidays or leisure [

46]. Typically, a cottage is a waterfront building for recreational use in a forest landscape. In Finland, cottages are usually located outside of towns and rural centers and do not form a single residential area [

47].

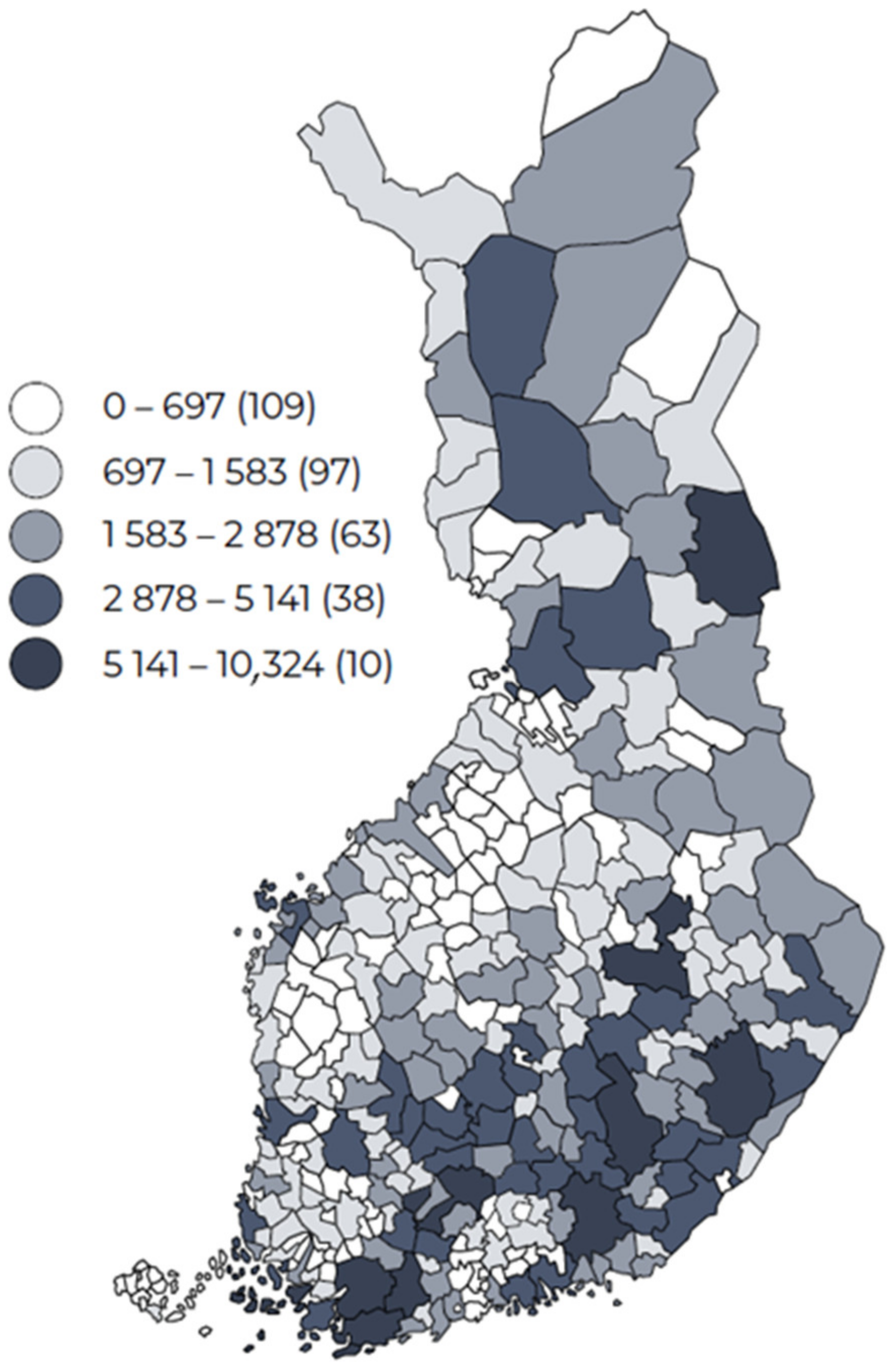

The construction of summer villas in Finland began in the 19th century, but in the early years of Finland’s independence, villa living was only possible for a select few [

14]. In those days, there were about 3000 villas in Finland. These early ancestors of cottages were primarily located near towns and cities but began to spread to the countryside and the coastlines. As the industrialization of cities grew, holiday homes offered an escape to fresh air and nature. Spending time at the cottage became a pastime for the entire population in the 1950s and the number of cottages began to grow rapidly. The 1980s were the peak years of cottage construction. As seen in

Figure 3, by the end of 2018 there were over half a million cottages in Finland [

17,

23,

24]. The distribution of these cottages by municipalities is presented in

Figure 4 [

48]. The Finnish cottage culture as we know it today is quite a recent phenomenon.

Around half of the population in Finland visit a cottage regularly [

3]. Owners of summer cottages are only one part of this wide variety of cottage users. For example, children and grandchildren often use the family cottage, and it is estimated that over 80,000 people belong to a household that owns a summer residence [

46]. According to the Cottage Barometer [

48], around three million Finns visit a cottage at least once a year. Although the acquisition of cottages is somewhat linked to an upper socioeconomic status and higher income [

19], Finnish cottage life is still a nationwide phenomenon.

The size, equipment level, and popularity of winter use of cottages are increasing, and their ownership is shifting to the new generation [

49] (see also Discussion). In addition, global megatrends such as the sharing economy, flexible working, and increasing environmental awareness due to climate change are also affecting Finnish cottage culture [

30]. Shoreline construction restrictions and new wastewater regulations are current topics among Finnish cottage owners [

50]. However, although the interest in cottages does not seem to be decreasing, the Finnish cottage is evolving with the changing trends and new generations. Without considering these changing needs and demands, inherited traditional cottages in Finnish forests are especially at risk of decay.

In terms of materials, wood has always been the most important building material for cottages and its popularity shows no signs of waning [

51]. Nearly all cottage buildings are wooden and newly constructed holiday homes are practically all wood, 70% of which are log buildings (see

Figure 5) in Finland [

52]. Wood is perceived as a natural and warm material that sits beautifully in the Finnish forest landscape [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57]. Wooden buildings are also ecological [

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68]. Other advantages of log construction include breathability, moisture balance, allergy friendliness, and aesthetics [

69].

As mentioned earlier, the literature is terminologically based on the second home and mostly focuses on issues such as governance, development, community, mobility, and tourism. To date, the literature lacks a comprehensive understanding of the cottage phenomenon, which is of great cultural and economic importance for Finland, from the point of view of experts [

46]. This gap may be partly due to the fact that an intimate and everyday summer cottage is already considered a matter of course [

70,

71].

Among the prominent studies, Overvåg [

72] discussed the connection between second homes and urban growth in the Oslo area in the Norwegian context. The analysis showed that second homes and urban growth are linked to some extent in Oslo, but government regulations potentially prevented a stronger link. Finally, the study highlighted that urban growth is only one factor influencing the location of second homes owned by Oslo residents, with current land scarcity and changes in demand being additional variables. Müller et al. [

73] examined the relationships between holidaymakers and the Swedish countryside through a survey among Swedish holiday homeowners. Responses from the survey showed that today’s leisure accommodation establishments do not intend to settle permanently in a holiday home. On the other hand, there were good reasons to believe that residential use will increase, suggesting that the boundaries between second homes and permanent housing will eventually blur. Hiltunen and Rehunen [

46] focused on the leisure-oriented mobile lifestyle between the urban home and rural second home in Finland, one of the world’s leading countries in terms of second home ownership and tourism through GIS data, questionnaire survey results, and national statistics. They concluded that societal changes, including megatrends such as urbanization, modernization, rural restructuring, and demographic change, impacted second place home tourism, distribution, and mobility. Moreover, historical events and political decision making at different levels of government have an effect on second home tourism. Rinne et al. [

71] analyzed the management of second homes in terms of public participation by using three future-oriented focus group interviews focusing on three Finnish cottage-rich locations. They concluded that the stereotype of traditional cottage owners is more and more concomitant, restructured, and challenged by the heterogeneous and diverse second home users. Their influence on local planning and decision making was channeled through a combination of formal and informal participation. The Finnish Environment Institute’s report [

18] scrutinized the perceptions of citizens and municipalities on the state and development of second home tourism. The report highlighted that second homes play a central role both in leisure mobility and in rural Finland, and the Finnish municipal authorities usually perceived second homes as a positive contributor to the local economies. The Routledge Handbook of Second Home Tourism and Mobilities [

74] provided an overview of different disciplinary and methodological approaches to second homes while simultaneously providing a broad geographical reach by exploring governance, development, community, and mobile second homes. On the other hand, there are numerous studies on the COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on second home ownership and tourism (e.g., [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

75,

76,

77]). Among the prominent studies, Zoğal et al. [

37] reviewed the epistemological evolution of the term ‘second homes’ due to the pandemic, as well as to reveal possible short-, mid- and long-term effects that could place second homes at the center of tourist activity and of the tourist rental market profitability. They found that in the early stages of the pandemic, second homes migrated from crowded cities to low-density areas, and a potential change in tourist preferences could place second homes at the center of tourist activity as soon as travel restrictions ease, which could intensify existing housing commodification processes by reinforcing housing platforms. Pitkänen et al. [

42] scrutinized the safety of second homes during the pandemic in different geographical contexts such as Finland, Sweden, Russia, and Canada. They found that although second-home cultures and contexts are different, people all around the world sought ‘escape’ and safety in their second home during the pandemic. Bieger et al. [

78], examined the interrelations between COVID-19 and second home prices in Switzerland as an empirical insight. The results showed that there has been a significant price increase for second homes—especially compared to apartments—after the start of the pandemic, and prices, even in certain second-class destinations, have risen significantly during the pandemic. In addition to the aforementioned literature, information is needed about the cottage and its development prospects as the economic and cultural impacts of the cottage are significant. The architecture and technical solutions of the cottages also have a major impact on the sustainability of cottage life in Finland and the condition and survival of the cottage stock.

The purpose of the study is to recognize the key changes affecting the architecture and use of Finnish cottages in order to support the continuity of the cottage culture, which is essential for the vitality of rural municipalities, regional development, national culture, and the well-being of individuals in Finland. The objective is to gain a broader understanding of the cottages’ current state and the associated changes thereto. This entailed engaging with multiple professional groups, such as municipal authorities (zoning planners, building control authorities) as well as real estate agents and representatives of cottage manufacturing companies, in order to understand the contemporary consumers’ demands, as well as to gain input from public officials on the same topic but from a different stakeholder perspective. In doing so, the study identifies main themes, i.e., the cottage buyers, characteristics of the dream cottage, diversified cottage, regulation of cottages in municipalities, and challenges in the regulation of cottages, affecting the cottage phenomenon in Finland. Additionally, the paper draws attention to cottages as a part of the current architectural debate, in which modest cottage construction is generally excluded. The work is not limited to the cottage buildings but also focuses on the surrounding environment, typically including, e.g., complementary buildings, docks, and wells.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: First, an explanation of the materials and methods used in the study is provided. This is followed by the results and discussion. Finally, the conclusions of the study are presented along with the prospects of cottage culture and recommendations for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was carried out through a literature review including international peer-reviewed journals, statistical data, and research projects (as noted in the literature review part in the Introduction and discussed in detail in the Discussion Section on the differences and similarities of our work with other research projects), supported by Häkkänen’s study [

47], as well as interviews with representatives of different relevant sectors, including city planners, building inspectors, real estate agents, and cottage suppliers.

In this research, semi-structured interviews (see

Appendix A) were applied as they facilitated interaction between the interviewer and the interviewee and allowed for considering themes that arose spontaneously during the interview process [

79]. In particular, the interviews were carried out by email and by telephone, as these methods enabled gathering of comprehensively concise information (qualitative data) across Finland. The emailed questions allowed the interviewees to respond flexibly according to their schedules and the email also provided for an opportunity to interview via telephone, if this was preferred by the interviewee. The results of the interviews and the identity of the interviewees were kept anonymous and confidential.

The interviewees were selected from the websites of municipalities and companies according to their occupation and location. The aim was to gain different perspectives on the current state of cottages in Finland, so the interviewees were chosen from four occupational groups: city planners, building inspectors, real estate agents, and cottage suppliers. Interview candidates were selected on the assumption that they would have experience and knowledge about the research topic as representatives of the rich municipality, real estate company, or cottage manufacturer. Real estate agents were selected from companies operating in Finland providing leisure residences. Additionally, here the emphasis was on selecting companies operating in different parts of Finland. The interviewed cottage suppliers were selected from among the largest suppliers in Finland and the interviewees were mostly chief executive officers or sales managers. The interviewees were not asked to provide any personal information other than their positions and anonymity was promised.

The questionnaires were formulated based on the research question of the study. The questions were composed separately for the four groups of professionals (city planners, building inspectors, real estate agents, and cottage suppliers) to gain knowledge from the respondents’ own areas of expertise. Interview questions were prepared separately for each professional category, considering their knowledge and experience in matters related to the cottage. Nevertheless, the questions were related to mutual themes, just from different perspectives. The questionnaire was identical within the groups, which allowed for comparison. The purpose of the questions was to be responder-friendly by narrowing down the topic sufficiently, but without leading on the interviewees. Some of the questions introduced themes to support the interviewee(s) in answering. However, the themes were introduced neutrally to not cause any bias in the answers. Depending on the category, 4–6 questions were asked (see

Appendix A). The interview requests highlighted the value of submitting an answer, even a short one, as the variety and number of answers were more important than the comprehensiveness of a single answer.

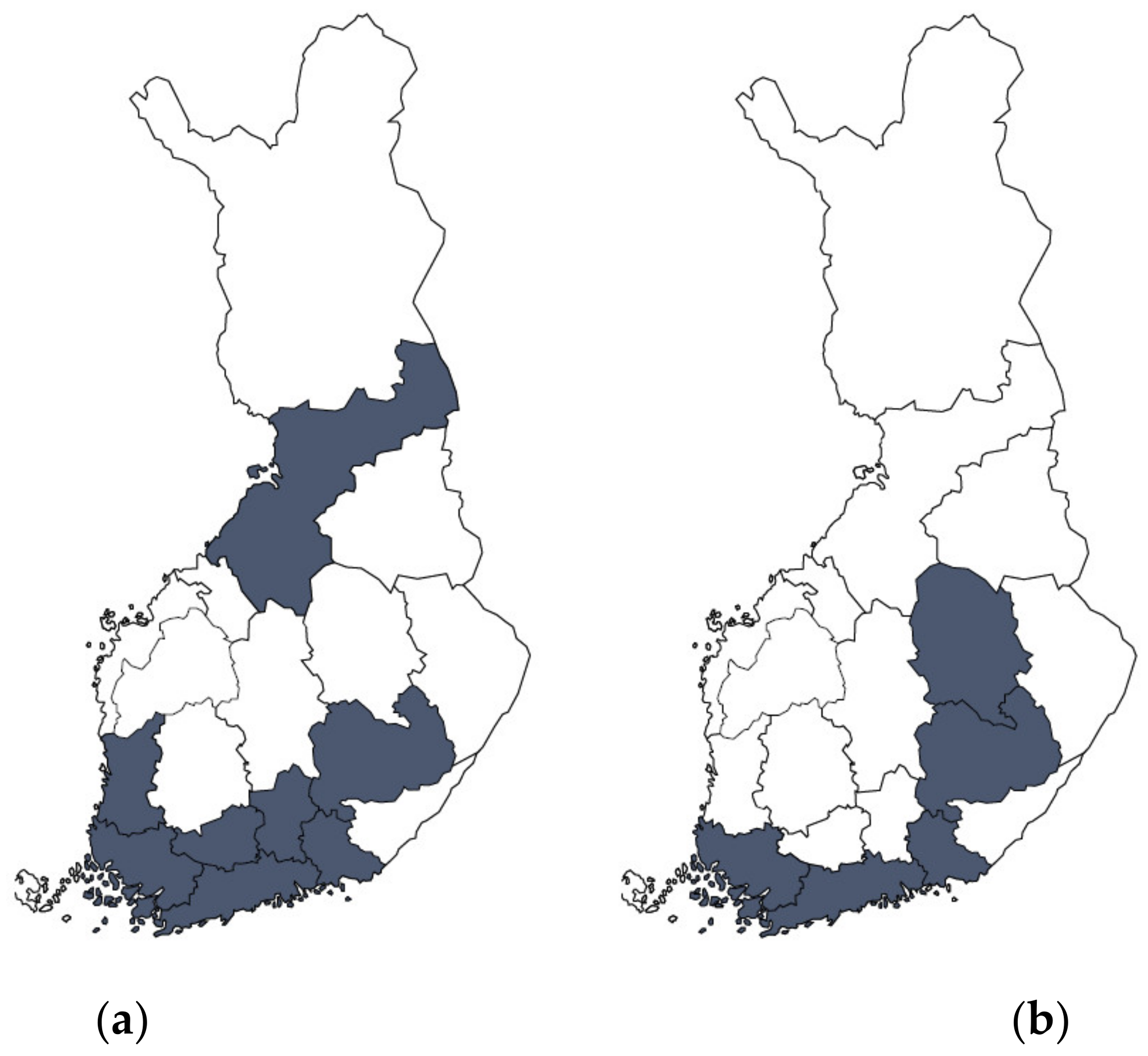

Each interviewee category was sent 11–13 interview requests, which totaled at 46 (see

Table 1). The requests provided a brief overview of the thesis topic and requested for the addressee to answer the enclosed questions. The addressees were encouraged to answer the questions by emphasizing the benefits of their answers to their profession and the importance of their answers. The initially sent interview requests were scarcely answered, however, a successful follow-up message was sent within two weeks, which was largely successful. A further reminder was also sent to the remaining non-responders. The final response rate was 67%. Two different persons were in charge of a municipality’s planning and, as such, their answers were utilized as complementing each other and counted as a single answer. In total, 31 sets of answers were received, six of which were phone interviews. A few email replies were supplemented with attachments.

The selected municipalities were among the most cottage-rich municipalities of Finland and the selection process also emphasized the importance of selecting municipalities from different parts of Finland (see

Figure 6). The interview request and questions were sent to the planning and building control authorities of the eleven selected municipalities and, primarily, the respondents were city planning architects and building inspectors. Responses were received from the zoning divisions of eight municipalities (response rate: 73%) and the building control authorities of six municipalities (response rate: 55%). The real estate agencies were arbitrarily selected from among the companies that operated in Finland and provided leisure residences. The emphasis here was also to select companies operating in different parts of Finland. The questions were answered by ten companies (response rate: 77%) and the interviewees were mainly real estate agents in management positions of the respective company. The surveyed cottage suppliers were selected from among the largest cottage suppliers in Finland. Responses were received from seven companies and the response rate was thus 64%.

In this study, the authors analyzed the data. The sample was manageable, so the analysis was conducted manually by going through and categorizing the answers. Classification of the obtained data is an important part of the analysis [

80]. The answers were grouped under the identified recurring themes: cottage buyers, characteristics of the dream cottage, diversified cottage, regulation of cottages in municipalities, and challenges in the regulation of cottages. The results of the interviews with real estate agents and cottage suppliers were presented within the scope of the first three themes, while the results of the interviews with the municipal authorities (zoning and building inspection) were primarily gathered under the last two themes. The questions created naturally led respondents to address specific topics, but the above-mentioned themes emerged frequently, even in answers to questions on different topics. The main themes, addressee, and main purpose of the interview questions are shown in

Table 2.

3. Results

As stated in the previous section, the results of the interviews were divided into themes that provide for a thorough image of the current state of leisure housing and of the housing trends. The presented themes occurred in multiple contexts in the interviews, irrespective of whether the respective question dealt with the specific theme, or who was the interviewee. However, how the theme occurred varied based on the interviewee. The interview results are presented based on the following categories: cottage buyers, characteristics of the dream cottage, diversified cottage, regulation of cottages in municipalities, and challenges in the regulation of cottages as seen in

Table 2.

3.1. Cottage Buyers

Based on the answers of both the real estate agencies and cottage suppliers, the largest age group of cottage buyers was around 50 years old on average. Moreover, the interviews displayed the cottage buyers’ values, such as an appreciation for convenience and green values. In the context of this category, the attitude(s) of the cottage buyers concerning the construction regulation relating to cottages is assessed.

3.1.1. Buyer Groups

The interviewees’ answers highlighted two main groups of cottage buyers; those looking for a new cottage and those looking for an old one. The largest age group was middle-aged adults, approximately 50 years old. According to the interviewees, this was due to the fact that on average, persons of that age cohort have a stable financial situation and they have more free time, partly due to their upcoming retirement. Another larger group of buyers consisted of families with children, where the adults were 35–40 years old. Notably, two interviewees identified an additional large buyer group, which consists of families with older children. Moreover, according to the results, cottage buyers were often connected by the fact that they had paid all, or most of, their loans concerning their primary home. Furthermore, in particular, the responses of the cottage suppliers emphasized that the financial situation of the customers was stable. One interviewee also highlighted the possible decline in the trend of owning a cottage and mentioned renting as a modern option for many.

3.1.2. Preference for Easy and Ready

In particular, in the interviews with real estate agents, it was emphasized that the cottage buyers appreciated ‘easy’ and ‘ready’ solutions in many respects. Moreover, according to the real estate agencies, the largest demand in the cottage markets would seem to be for the new or already renovated cottages. However, as one of the interviewed real estate agents noted, a property area in need of a renovation may be considered if the location is particularly pleasant, or if the price is low enough.

This phenomenon also occurred when the equipment level of the cottage was considered. The list of amenities requested by the cottage buyers indicated that a similar level of equipment to the primary home is expected from a cottage. The comprehensive package deals of the cottage suppliers who delivered readymade cottages would seem to appeal to those who would like to receive readymade cottages easily and effortlessly. When the real estate agencies were asked what plans the cottage buyers had for their cottages in the future, not only did the cottage buyers often indicate that they wished to renovate the property, but also that they would like to avoid making small renovations and alterations constantly. Moreover, the cottage buyers’ responses highlighted the appreciation for easy maintenance of the property.

Despite these wishes for one-off renovations, the interviews also displayed different perspectives regarding the maintenance and renovation of the property. According to one real estate agent, younger families often searched for a property that may be in need of renovation, as this allowed for the families to renovate the property to their liking at a lower cost. However, this might be caused by the fact that younger families may not have the funds to buy a readymade property, and, as such, they would rather make the renovations themselves.

In conclusion, it would seem that regardless of the equipment level or the intended use of the cottage, the average cottage buyer would seem to prefer properties that do not need to be renovated. However, a particularly inexpensive or well-located property may prove an exception to the rule. Lastly, the interviews highlighted the cottage buyers’ preferences for easy maintenance and effortlessness.

3.1.3. Green Values

To clarify the values and opinions of cottage buyers, the real estate agencies and cottage suppliers were asked if their customers had considered environmental issues regarding the purchase of a cottage. The responses varied, which may be due in part to the ambiguity of the term ‘environmental issue’. The answers of the real estate agents indicated that cottage buyers considered environmental issues relating to purchasing a cottage from the perspective of the cleanliness of the surrounding nature, especially the water system, but not so much from the perspective of, e.g., their or their cottage’s use of energy. Many responses emphasized the buyers’ interest in water purity, domestic wastewater systems, and waste management.

It was also possible that the interpretation of the question reflects the preconception of the environmental friendliness of maintaining a cottage. In contrast, the cottage suppliers’ discussions with cottage buyers revealed that the environmental issues were understood to refer to the structure of the cottage and the associated technical solutions. For instance, a log structure was often automatically associated with being environmentally friendly. Accordingly, an interviewee noted that the concern or interest towards environmental issues is more prevalent in the category of residential houses and properties, where a log house has become a viable option. Another interviewee remarked that the interest in environmental issues is also associated with the potential reduction in maintenance costs resulting from environmentally friendly solutions. However, the responses indicated that in general, environmental issues are of particular interest to buyers ordering new cottages.

While some research results show that younger generations place less value on the environmental friendliness of going to and maintaining the cottage, the assumption was that Finns have an increased interest in eco-friendly cottages. In general, the interview results conveyed that environmental values are of interest to cottage buyers and users, but, nevertheless, they are not on peoples’ priority list, or the values are not associated with peoples’ actions. The real estate agencies and cottage suppliers did not mention their clients’ environmental values, or requests relating to the values before the agencies and suppliers were specifically asked about this.

However, there was one exception where the interviewee mentioned, while being asked about the cottage buyers’ life situation, that families’ environmental considerations were increasing and that instead of spending holidays abroad, the families may look for a rural atmosphere from Finland. A few responses also suggested that if asked, cottage buyers tend to indicate that they are concerned about environmental matters, but, in practice, other things were given priority when purchasing a cottage.

3.1.4. Buyers’ Attitudes towards Regulations

According to the interviews, cottage buyers were mainly positively concerned about the current wastewater regulations, as the following excerpt demonstrates: ‘Wastewater regulations are discussed with almost every customer. People are responsible and want their actions to contribute to the well-being of their immediate environment. However, the costs relating to alteration works are very worrying. But the renovation work, the costs are very worrying.’

Two of the interviewed real estate agents noted the cottage buyers’ concerns about the costs relating to compliance with the wastewater regulations, albeit their attitudes were positive in general towards the regulations. A real estate agent also noted that the costs relating to compliance with wastewater regulations are a bit exaggerated. In discussing the wastewater management systems, the previously occurred cottage buyers’ appreciation for the completeness of the property is shown by the following statement: ‘Some [environmental issues] are of interest. Of course, it would be good if the wastewater regulation-compliant wastewater system solutions would be already in place.’

In discussions with the real estate agencies and cottage suppliers, the regulations concerning shoreline development were commented on significantly fewer times than the wastewater matters. Few of the interviewees stated that different regulations and varying interpretations among different municipalities are challenging. According to some responses, the shoreline development regulations became relevant only when the subject of a sale is a plot of land or when the plot has a cottage of which replacement is under consideration. Furthermore, according to a real estate agent, the building control authorities received inquiries as to how one could circumvent the shoreline development regulations, which have become stricter.

3.2. Characteristics of the Dream Cottage

The interviews focused on the desired characteristics of the cottages/holiday houses, particularly in terms of location, architecture, equipment level, winter habitability, and condition.

3.2.1. Location

When the real estate agencies were asked what kind of cottages the highest demand on the market was for, 80% of the interviewees replied that the cottage’s distance from home and services are the determining factors. Namely, services should be located within 30 min from the cottage and the duration of the trip from home to the cottage should be within the range of less than an hour to a maximum of three hours, according to the real estate agencies. It can be assumed that this assessment is influenced by the real estate agents’ operating area. Most interviewees represent real estate agencies operating nationwide.

Furthermore, the interviews relating to location emphasized the importance of having their shoreline and noted that there is not as much demand for the so-called dryland cottages as there is for those with their shoreline. In total, 80% of real estate agents stated that either their clients require that the property they are buying should have a shoreline or at least that the cottages with a shoreline have a higher demand.

A real estate agent stated in an interview that more cottages with a shoreline are being sold each year, as the cottage sales in general increase by about one percent per year. However, according to the same interviewee, still, about a third of the cottages sold do not have their shoreline.

3.2.2. Architecture

Estimates of what size cottages were most in demand or what size new cottages were ordered varied widely. Not all interviewees gave information about the size of the cottages. In general, cottage suppliers and real estate agents estimated the floor area of purchased cottages to be approximately 70 m². Both groups of experts emphasized the importance of the number of bedrooms matching the buyer’s needs. The floor areas of cottages ordered from cottage suppliers specializing in prefabricated log cabins were smaller compared to most answers. One of these suppliers stated that buyers wanted cottages the size of a ‘spacious one bedroom-apartment’, approximately 45–50 m², and the most popular models from the other cottage supplier were only the size of 25 m² and 50 m².

From an architectural point of view, cottage suppliers highlighted that buyers especially hope for contemporary style cottages, large windows, open spaces, and extensive terraces. More than 40% of respondents mentioned pent roofs as the preferred option for current cottage buyers.

Respectively, almost one-third of the interviewed real estate agents mentioned large windows, preferably with lake views (see

Figure 7), as desirable cottage features. In addition to contemporary style cottages, the more traditional style cottages were found to have buyers.

The cottage suppliers were asked which of their cottage models were the most popular. The assumption behind the question was that there might be some more popular models that, if necessary, buyers would then further modify to suit their needs. However, the responses reflected how wide the possibilities were for companies to modify their predesigned cottage models to meet clients’ wishes and even offer unique designs. The companies that responded to the interviews primarily specialized in log construction. All these companies have predesigned collections, but many also offer individually designed buildings from start to finish.

Even so, three-quarters of the interviewed cottage suppliers were able to list some of their more popular cottage models. These mentioned cottage models have a lot in common, for instance, vast covered or open terraces and large windows and even glass walls. Most models had gable roofs, but the more modern designs were typically distinguished by pent roofs or some other asymmetrical roof shape. The floor plans of these popular models were often based on an open concept central living space and kitchen to which other rooms were open. As for the exterior, buyers were often drawn to minimalistic architecture with a touch of tradition, for example, a gable roof or wide window frames. A modern look might be especially sought after when building a new cottage, but when buying an older cottage, a more traditional style of architecture can also be seen as a viable option as it reflects the age of the building.

Although there was a wide range of predesigned cottages to choose from, the most popular models described by cottage suppliers were surprisingly similar, especially regarding the exterior architecture. Nevertheless, buyers still wanted to ‘leave their mark’ on off-the-shelf cottage models. In some interviews, it was found that only minor changes, such as the placement and dimensions of windows and doors, were sufficient to satisfy buyers.

3.2.3. Equipment Level

The interviews clearly showed that well-equipped cottages are in high demand, and some interviewees also stated in their response that they have recognized this as an increasing trend.

Real estate agents specifically highlighted the importance of running water and indoor toilets to buyers. Cottage suppliers also described in demand cottages as highly equipped and even comparable to the equipment level of primary homes. In some interviews, it was found that the cottages were even better equipped than most permanent homes. According to the responses, electricity was practically considered self-evident in cottages even though the concept of off-grid cottages is not unfamiliar to Finns.

About one-third of real estate agents stated that the lack of electricity reduces the number of interested buyers or that the buyer plans to order an electrical connection immediately. Nevertheless, one real estate agent noted that some settle for solar power and a generator if this hybrid system is a cheaper option than ordering a new electrical connection. The source of energy was, therefore, more a matter of cost rather than environmental values.

3.2.4. Year-Round Use

The increase in the year-round use of cottages was a clear theme in the interviews. Up to 70% of the interviewed real estate agents stated that cottages that are also suitable for wintertime visits are most in demand in the cottage market.

Even though cottages’ winter suitability was not addressed directly in some interviews, the described high equipment level can be interpreted as allowing year-round use in many cases. When asked what buyers desire from their new cottage, over 70% of interviewees representing cottage suppliers mentioned winter use or year-round heating as a criterion. One interviewee perceptively stated that rather than winter use being the main requirement, the most important criterion is how the features of the cottage hold up to the buyers’ visions of their desired cottage life.

3.2.5. Condition of the Cottage

Each one of the interviewed real estate agents stated the poor condition or old age of a cottage as factors that lowered the value of the property and reduced the number of interested buyers. Moreover, nearly a third of these real estate agents pointed out that cottages built in the 1970s are especially problematic for sales.

In their responses concerning the condition of cottages, two estate agents specifically mentioned the quality of indoor air, as a musty smell is easily associated with neglected and uncared for cottages. In addition to the building’s poor condition, properties in need of renovation were often mentioned to deter interested buyers.

Therefore, according to the interviews, buyers were mainly reluctant to renovate old cottages. The cost of remodeling might be difficult to accurately estimate, and convenience and effortlessness were valued. Other factors that were mentioned as reducing the cottage’s value or interested buyers included location and site-related things such as a missing road to the property, the proximity of neighbors, and an unkempt yard. The lack of shoreline discussed above dampens interest, but there was also less demand for island cottages.

3.3. Diversified Cottage

The real estate agents interviewed highlighted the popularity of winter use of cottages but also acknowledged the demand for other types of cottages. One interviewee noted the demand for so-called three-season cottages, which are left unused only during the coldest winter months, and for solely summer cottages with fewer amenities, favored by budget or environmentally conscious cottage owners.

An interviewee representing a major real estate agency highlighted that the cottage market is polarized, with second homes with washing machines at one end and traditional cottages with no running water at the other end. Another interviewee from a real estate agency that operates widely in Finland stated that apart from electricity, other amenities may not even be wanted. One interviewee went even further and implied that even cottages without electricity can be sought after as a new trend and a more ecological option. Given the amount of poorly equipped simple cottages in Finland, this was a welcome trend.

Linked to the diversification of cottages, the popularity of cottages combined with holiday resorts and activities was mentioned in the interviews. Despite the continued popularity of waterfront cottages, dryland cottages were seen as a viable option when they were in resorts offering services and recreational activities.

Only one real estate agent and two representatives of cottage suppliers expressed buyers’ wishes regarding the suitability of a holiday home for permanent residence. The issue of permanent residence in cottages was a clear theme in the discussions with the authorities. In addition to changes in the intended use of cottage buildings, two planning authorities mentioned tourism as an important planning and development issue related to cottages in their municipalities. The demand for tourism was recognized, but there were many difficulties for its development.

In general, opinions about the popularity of cottages varied. One real estate agent pointed out that interest in cottages has plummeted over the years and another that the sale of holiday homes has completely collapsed from previous years. Then again, a third real estate agent emphasized that Finns have a strong cottage culture, and the sales of holiday homes keep on growing and even talked about the ‘new era of cottages’. This demonstrated how even experts in the same field may have distinctly contrasting opinions.

3.4. Regulation of Cottages in Municipalities

When asked about the attitude of municipal zoning to the construction of cottages on shorelines, both cautious and more direct answers were received. Many city planners confined themselves to discussing the shore planning system and the current situation, without further commenting on the municipality’s stance on waterfront construction. However, the high degree of detailed shore plans in the municipalities, which was apparent from the answers, indicated that the recreational use of shores is promoted.

Interview data confirmed that the development of municipal shorelines was highly controlled, as several planners stated that nearly all shore areas were covered by either local shore master plans or local detailed plans. About 40% of the interviewed planners underlined that the municipality favor waterfront construction if certain conditions are met. It should be noted that municipalities specifically rich in cottages were selected for the interviews, and therefore it can be assumed that these municipalities understand the value of secondary homeowners for the municipality’s financial situation and the provision of services.

Despite the high degree of zoned shore areas, the interviews also revealed that there is pressure to develop these already zoned shorelines and to also plan for recreational living inland as the shoreline fills up. In one interview, it was stated that although a lot of areas have been zoned for the controlled construction of holiday homes, a lot are still unconstructed due to the reluctance of landowners to sell these decreasing waterfront plots. The situation could be similar in other interviewed municipalities as the zoning degree does not directly relate to the amount of construction.

According to the interviewed building control authorities, the inquiries regarding holiday homes were commonly related to building rights, wastewater treatment, and possibilities for permanent residence. In addition, questions regarding building codes, the required shoreline setback area, energy efficiency, and the addition of amenities were common.

One-third of the interviewed building control authorities reported that questions about cottage energy regulations were often asked. Compliance with the minimum energy efficiency requirements for a building needs to be demonstrated by calculations. Only two building control authorities found that inquiries and permit applications regarding holiday homes had decreased in the 2010s compared to the beginning of the millennium.

3.5. Challenges in the Regulation of Cottages

Answers regarding the municipality’s stance on cottages increasingly evolving towards permanent residence-like buildings were mostly similarly vague as with the question about land use and development along shores. In more explicit responses, the attitudes of planning authorities were cautiously favorable or even positive regarding the matter. One planner explained that they welcome the conversion of cottages to permanent residences in rural areas, but there were some issues just on the outskirts of areas covered by detailed plans as the interests of second home residents and permanent residents or the city do not always coincide. In another interview, it was strongly stated that the municipality does not support the change in the intended use of holiday homes to permanent homes. However, almost every answer related to the topic stated that changes in the use of cottages to permanent residences are possible if the necessary conditions are met. Similarly, when the interviewed building control authorities were asked about challenges associated with recreational housing, emphasis was placed on issues related to changes in use.

In interviews with municipalities’ zoning divisions, almost all respondents felt like there was a need to revise current zoning plans for recreational homes. This was mainly due to the too limited building rights in the old shore plans, which was mentioned by half of the interviewed planners.

In addition, building control authorities addressed other challenges with cottages. It was noteworthy that the wishes of cottage owners and buyers did not always align with current municipal regulations. For example, a building inspector from an especially cottage-rich municipality stated that there is a demand for flush toilets in cottages, but zoning plans and regulations prevent them. Wastewater regulations were also reiterated as a challenge by building control authorities. One interviewee noted that the wastewater treatment guidelines in existing zoning plans do not fully comply with the new, even somewhat looser, wastewater regulations. However, revising the existing local master plans was seen as a long and arduous process.

4. Discussion

Main highlights from the study of the main themes of the current state of the Finnish cottage phenomenon include:

- (a)

Cottage buyers were mostly in their 50s and wealthy. Particular attention was paid to convenience, readymade solutions, and effortless maintenance. Environmental issues were of interest to buyers, but not so much in terms of usability and nature around the cottage and the ecology of the cottage. Buyers’ attitudes towards wastewater regulations showed an interest in protecting their cottage’s environment and water system.

- (b)

The high level of equipment required for cottages and suitability for winter use were important issues for cottage buyers, and well-equipped cottages often met buyers’ needs.

- (c)

Location was the critical parameter in choosing a cottage, confirming the overwhelming popularity of holiday houses. Although a modern and simple style was generally preferred in cottage architecture, there was also a demand for different alternatives in this regard. The cottage’s poor condition was often an obstacle to its sale, in conjunction with buyers’ predestined reluctance to undertake the troublesome renovations.

- (d)

Diversification of today’s cottages was among the prominent themes. Despite the continued popularity of waterfront cottages, inland cottages were also seen as a possible alternative when they offered other advantages, e.g., were in resorts offering services and recreational activities. Although an increasing proportion of Finland’s cottages were well-equipped holiday homes fit for year-round use, the humble summer cottage was still current. The cottage in Finland is a widespread and diverse phenomenon and experts had varying views on the direction of its popularity.

- (e)

The municipalities’ attitudes towards shoreline development regarding recreational housing were reserved but cautiously positive if certain conditions were met. Building rights, wastewater treatment, and permanent living at cottages were also important considerations. In general, although buyers’ needs were very uniform, the municipalities’ attitudes and practices towards cottages differed in different municipalities.

- (f)

Under certain conditions, changes in the intended use of cottages to permanent residences were possible. Meeting some user needs faced regulatory hurdles, such as the need for watered toilets in summer cottages.

The findings of this study regarding the profiles, expectations, demands of cottage buyers, and views of municipal authorities confirmed some of the results reported in other studies and surveys, such as the economic stability of cottage buyers, buyers’ positive attitude towards wastewater regulations, buyers’ expectations for easy and ready-to-use solutions, and the size and location of the cottage as deciding factors (e.g., Hiltunen and Rehunen [

46], Overvåg [

72], Müller et al. [

73]).

Although it is not possible to comprehensively compare the Finnish cottage phenomenon with practice in other countries due to the lack of the literature in terms of expert views, as in Finland, the concept of the second home is an important phenomenon in many countries such as Canada, other Nordic countries, New Zealand, Australia, Spain, and Switzerland. For example, in Canada, second homes occupy prominent places in the Canadian spirit and Canadian landscape, and second homes are described as places of solitude, family, silence, and rest [

42]. Most notably, they are places to ‘escape’ from the everyday lives of Canada. As mentioned before, second homes are part of Scandinavian heritage in Denmark, Norway, Sweden as well as Finland [

3]. The importance of second homes in Scandinavian countries has sparked a debate about how important they are to tourism, and many issues are still high on the research agenda [

81]. Similarly, historically, second homes have been an integral part of New Zealand lifestyles, and they have important implications for environmental, economic, and social planning due to their location, importance for tourism, and various design and usage features. [

82]. In Australia, second homes form an important part of both ownership and lifestyle cultures, though these are less explored [

83]. Increased leisure time, greater prosperity, increased mobility, and income growth are some of the factors explaining the increase in second home demand in Spain over several decades [

28]. Similarly, Switzerland has traditionally strong second homeownership as well as second home market [

78].

In interviews, cottage buyers were reported to be mostly in their 50s and wealthy. However, according to the Homes beyond Homes Study (HbH Study) survey of 4000 Finnish multiple dwelling and second home users with a 30% response rate in 2012, the average age of second homeowners was 60, while users were a generation younger, an average of 40 [

46]. While the age of ownership seems to decrease over time, this may also indicate that younger urban generations may show less interest in country house living and prefer other leisure activities.

On the other hand, similar to our findings, the HbH Study showed that the total gross income level of second home and user households was typically above the Finnish national average [

33]. The issue with economically stable cottage buyers can be attributed to the fact that an increase in economic growth, household disposable income, and family well-being can lead to increased interest in second-home investment and purchase [

46]. This feature can characterize second households in all Scandinavian countries [

20].

The responses indicated that along with the overall increase in the standard of living, the standard of equipment in second homes continues to rise. Cottage buyers were satisfied with the ‘easy’ and ‘ready-to-use’ solution and the cottages with a similar level of equipment to a regular house. In addition, running water and closed toilets stood out as the demands of the buyers. The electrical connection in the cottage was also usually specified as a requirement of the buyers. Similarly, a comparative study [

73] conducted among Swedish second homeowners drew attention to the importance of having the same equipment level of a second house as a permanent house. The equipment standard affects the use of the second home and affects the number of visits and length of stay; in other words, more modern amenities and facilities are used in the second home [

46]. On the other hand, our finding on the demand for electrical connection in the cottage resembled the finding in the HbH Study [

46], where most of the second homes (87%) were electrically wired.

Environmental issues were considered interesting in responses to green values, but the tendency of buyers was primarily based on the cleanliness of nature and especially the water surrounding the cottage, and not, for example, on the direct use of one’s own or the cottage’s energy. This can be attributed to the findings of the HbH Study [

46], where only 14% of second homeowners used renewable energy such as solar and wind.

According to the interviews, the buyers were mainly positively concerned about current wastewater regulations and the regulations in force played an important role in the development of the cottages. Similarly, Norwegian research on second homes and urban growth in the Oslo area by Overvåg [

72] indicated that the spatial development of the second home is influenced by building regulations and environmental planning guidelines.

In terms of location, the distance from the cottage and services to the cottage were deciding factors for buyers, and there was greater demand for waterfront cottages. This can be associated with the fact that the lakeside location is a cliché of cottage culture and an essential part of the Finnish national landscape. These findings confirmed the findings of Shellito’s study [

84]: here, second home locations depended on the distance from large and small urban centers, and accessibility by local roads, and the availability of natural areas and bodies of water, played the most dominant roles in second home distribution. Similarly, Overvåg [

72] highlighted the impact of the establishment of roads and transport networks, the location of comfort-rich zones, and the availability of nearby entertainment venues on the distribution of second homes. On the other hand, in the Finnish Lakeland case, Pitkänen [

85] showed that rural roots, kinship, and cottage heritage influence second home locations and distribution. Müller [

28,

86] pointed out that there are highly attractive areas and ‘hot spots’ for second home buyers over long distances, such as mountain and coastal areas.

Estimates of what size cottages were most in demand or what size new cottages were ordered varied widely, but, overall, cottage suppliers and real estate agents’ estimates of the area of purchased cottages were around 70 m² and the size of a ‘spacious one bedroom-apartment’ approximately 45–50 m². These areas were confirmed by the work of Hiltunen and Rehunen [

46], where the average floor area in the second house was 66 m² (mean) and typically 50 m² (median).

Regarding challenges in the regulation of cottages, the sewerage and wastewater regulations were reported as problematic issues and it was evaluated that the regulation on the dimensioning of shore construction should be updated. Similarly, in the survey study on second home tourism in Finland by Adamiak et al. [

18], it was highlighted that changes in the forms and structures of second homes and life necessitate the revision of existing governance mechanisms, especially in terms of spatial planning and construction.

It is worth mentioning here that, as in many other countries [

87], the Finnish property market has been significantly affected by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic since March 2020 [

88]. According to Finnish National Land Survey statistics [

89], the number of cottages changing hands in the first four months of 2021 was about 50 percent higher, with the average price of cottages more than 20 percent higher than in 2020. Moreover, the average time to sell a single-family home, which was 120 days across the country, dropped from 100 a year or two ago to 80 days in 2021 [

90]. Similarly, in Switzerland, after the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, there has been a significant price increase in second homes—especially compared to apartments [

72].

5. Conclusions

This paper aimed to support the continuity of Finland’s cottage culture, which is essential for the vitality of rural municipalities, regional development, national culture, and the well-being of individuals, by shedding light on the current state of the Finnish cottage through the perspectives of experts in terms of the expectations and demands of cottage buyers and views of municipal authorities. In doing so, this study sought to identify main themes, i.e., cottage buyers, characteristics of the dream cottage, diversified cottage, regulation of cottages in municipalities, and challenges in the regulation of cottages, affecting the cottage phenomenon in Finland.

Our findings have important policy or regulatory implications for the housing and rental market dynamics. In particular, it will provide key stakeholders in the construction industry, architects, engineers, and other control mechanisms with an insight into design and implementation approaches to user needs. Similarly, considering the demands of cottage buyers and the views of municipal professionals, new designs, and retrofits for existing cottages, the cottage market will, in particular, seek more satisfactory solutions to not only buyers’ requests, but also to regulatory and legal obligations required by the relevant authorities in local planning and decision making.

As a result, the preservation of cottage culture in Finland largely depends on finding easy and cost-effective solutions for the younger generation to modify the cottage stock to meet their requirements and hopes for cottage life. The cottage supply’s variety and its inclusiveness must be maintained in the future so that as many people as possible can acquire, lease, or use the kind of cottage they like.

There is a need for studies presenting concrete design solutions that consider these modern-day demands for cottages described in this study and could benefit the preservation of the cottage stock, and the culturally and economically important cottage culture. The empirical findings of the study showed that cottages’ potential users can play a critical role in local planning and decision-making processes.

Possible topics for further research include the refurbishment of old cottages and improving their eco-efficiency, the potential of uninhabited cottages and rural buildings, the expansion and development of cottages for multi-generational use as well as the challenges associated with inherited cottages, and opportunities for different cottage rental and co-ownership concepts.

In a country with over half a million cottages, the cottage phenomenon should be a better part of the current architectural debate and completed projects should inspire what is to come. Moreover, more research is necessary to better understand the dynamics between different types of cottage users and administrative practices, which can help to manage cottages more constructively and to avoid unnecessary conflict in densely populated areas. As with other building types, cottages must withstand time and represent technically and aesthetically high-quality architecture.

Given the lifestyle that has changed dramatically with housing conditions and the increasing importance of outdoor use due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the boom in demand for the cottage-like lifestyle seems very realistic. This might be the main reason for a significant price increase, especially for second homes compared to apartments in Finland, after the onset of the COVID-19 crisis. In addition, considering the growing interest of buyers for their garden properties and their readiness to move further from city centers, the epidemic has also fueled people’s urge to experience nature, as in the case of families with children aiming to connect with nature through a garden or an affordable leisure house. As a result, job-related reasons such as working from home and prolonged time of using a second home can make year-round cottage demand much higher than it was before the pandemic, which may particularly affect the dynamics of the Finnish cottage market (e.g., more demand for houses with larger gardens stemming from the desire to experience more of nature).