The Role of Sports Facilities in the Regeneration of Green Areas of Cities in Historial View: The Case Study of Great Forest Stadium in Debrecen, Hungary

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

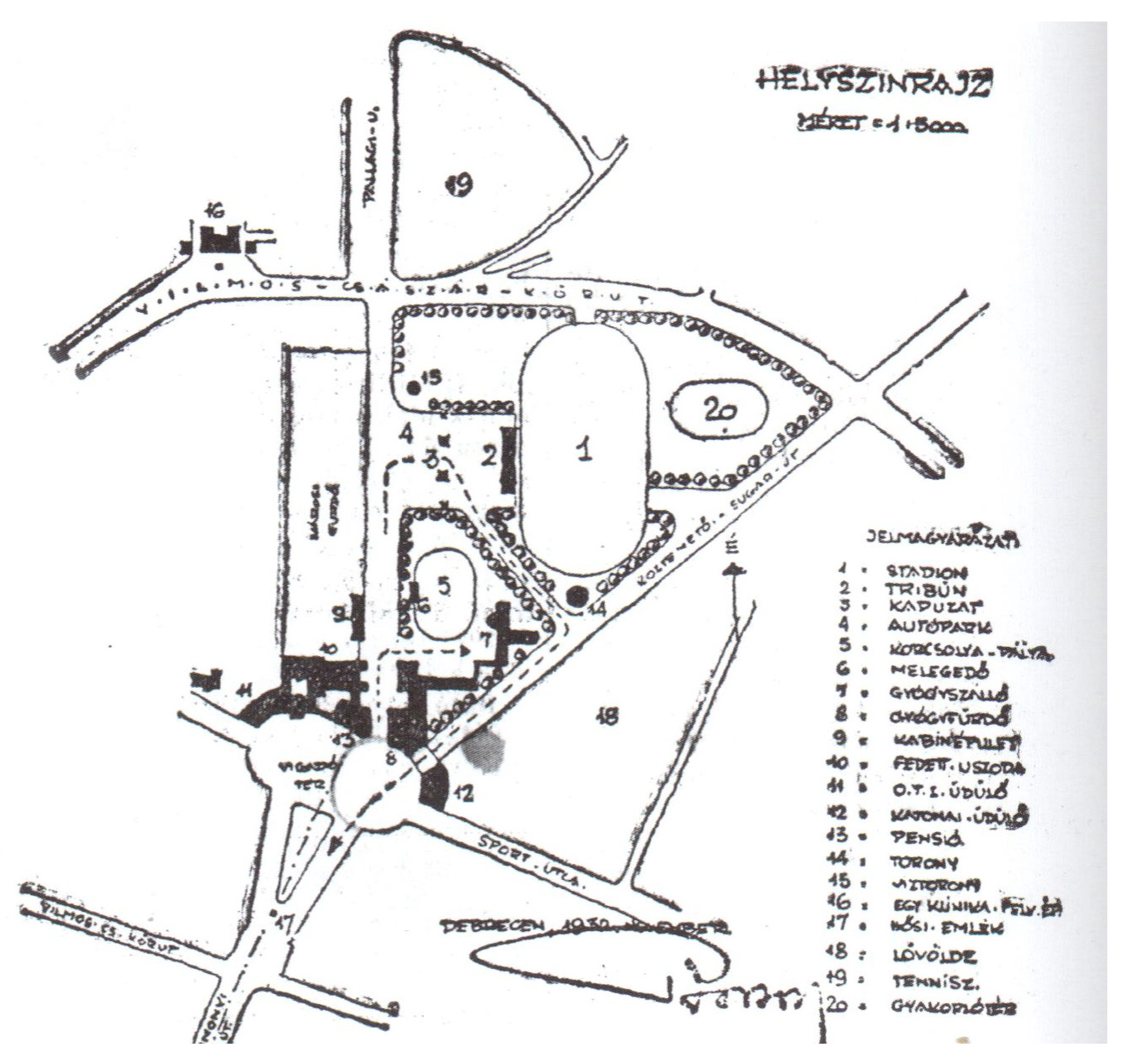

3.1. Developments in the 20th Century

3.2. Most Important Factors of Necessity of Regeneration

3.3. Investment of Great Forest Stadium and Its Impacts in the 2010s

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- -

- Regeneration of Great Forest Stadium has played an important role in the development of the district in two periods, but with some differences. On the on hand, the construction of a stadium in the 1930s was the flagship project for the development of an essentially undeveloped area. This was followed by subsequent developments which, in line with the urban plan, were to some extent linked to sport. On the other hand, in the 21st century the new stadium was built on an already developed site and played a very important role in the renewal of the entire neighbourhood of the city, but in this case, more emphasis has been placed on creating conditions for general recreation/entertainment.

- -

- In terms of the characteristics of the investments triggered by the construction of the stadium, the predominance of public development is discernible. The whole regeneration project was financed by the state budget, while most of the related investments were financed by the European Union.

- -

- Residents were generally positive about the improvements made and considered that the investment has become an important element of the city’s image.

- -

- If we look at further directions of the research, two areas can be mentioned: analysis

- -

- of the multifunctional nature of the Great Forest Stadium as a sports facility; what other activities can be offered in addition to sports.

- -

- Analysis of the impact of sports-related developments on neighbourhoods in other Hungarian/Central European cities: are there any effects? If not, what are the reasons for them; and if so, what are they?

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; Luk, Y.M. Impacts of the 4th East Asian games on residents’ participation in leisure sports and physical activities–the case of Macau, China. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2011, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuen, B. Sport and urban development in Singapore. Cities 2008, 25, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, G.; Zjang, J.J. Sports and urban development: An introduction. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2021, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C. A level playing field? Sports stadium infrastructure and urban development in the United Kingdom. Environ. Plan. A 2001, 33, 845–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Moya, F. Coping with shrinkage: Rebranding post-industrial Manchester. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2015, 15, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendafilova, S.; Waller, S.N.; Daniell, R.B.; McClendon, J. “Motor City” rebound? Sport as a catalyst to reviving downtown Detroit: A case study. City Cult. Soc. 2012, 3, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, L.E. A wider role for sport: Community sports hubs and urban regeneration. Sport Soc. 2016, 19, 1537–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornley, A. Urban regeneration and sports stadia. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2002, 10, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. The development of „Sports-City” zones and their potential values as toursim resources for urban areas. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2010, 18, 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Pitts, A. A brief historical review of Olympic urbanization. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2006, 23, 1232–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma, G.; Pénzes, J.; Molnár, E. Spatial development of sports facilities in Hungarian cities of county rank. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2016, 31, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mark, P.; Geoff, W. “It’s just a Trojan horse for gentrification”: Austerity and stadium-led regeneration. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2018, 10, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Georgantas, E.; Lekakis, N. The politics of urban regeneration in Liverpool and Everton FC’s alternate new stadium-project plans. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2021, 8, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X. The Question of Legacy and and the 2008 Olympic games: An Exploration of the Post-Games Utilisation of Olympic Sport Venues in Beijing. Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Boukas, N.; Ziakas, V.; Boustras, G. Olympic legacy and cultural tourism: Exploring the facets of Athens’ Olympic heritage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 19, 203–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W. A winter sport mega-event and its aftermath: A critical review of post-Olympic PyeongChang. Local Econ. 2019, 34, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barghchi, M.; Omar, D.; Aman, M.S. Sports Facilities Development and Urban Generation. J. Soc. Sci. 2009, 5, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, T. The political economy of sports facility location: An end-of-the century review and assessment. Marquette Sports Law J. 2000, 10, 361–382. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, S.L. Sports Facilities: From Multipurpose Stadia to Mixed Use Developments. In Proceedings of the American Real Estate Society Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 11–14 April 2007. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, N.; Berger, I.E.; Hernandez, T.; Parent, M.M.; Seguin, B. Urban sportscapes: An environmental deterministic perspective on the management of youth sport participation. Sport Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, E.C.; Westerbeek, H.; Liu, D.; Emery, P.; Turner, P. Managing Sport Facilities and Major Events; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ladu, M.; Balletto, G.; Borruso, G. Sport and the city, between urban regeneration and sustainable development. TeMA-J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2019, 12, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jámbor, V.E.; Vedrédi, K. On the edge of new public spaces–city centre renewal and exclusion in Kaposvár, Hungary. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2016, 65, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, T.H.; Comer, J.C. Changing Intra-Urban Location Patterns of Major League Sports Facilities. Prof. Geogr. 2000, 52, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, L.E. Sport and economic regeneration: A winning combination? Sport Soc. 2010, 13, 1438–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carrière, J.P.; Demazière, C. Urban planning and flagship development projects: Lessons from Expo 98, Lisbon. Plan. Pract. Res. 2002, 17, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodach, C. Beyond Bilbao: Rethinking flagship cultural development and planning in three California cities. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2010, 29, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smyth, H. Marketing the City: The Role of Flagship Developments in Urban Regeneration; E & FN Spon: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Spina, L.D. Cultural Heritage: A Hybrid Framework for Ranking Adaptive Reuse Strategies. Buildings 2021, 11, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieczka, M.; Wowrzeczka, B. Art in Post-Industrial Facilities—Strategies of Adaptive Reuse for Art Exhibition Function in Poland. Buildings 2021, 11, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajó, I. The construction of the sports park and stadium of the free royal city of Debrecen. Debr. Képes Kal. 1934, 34, 142–143. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Sápi, L. Settlement and Building History of Debrecen; Déri Múzeum Baráti Köre: Debrecen, Hungary, 1972. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Rácz, Z. Borsos József; Tiszántúli Református Egyházkerületi Gyűjtemények: Budapest, Hungary, 2015. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Niklai, A. City and Urban Development–Long Term Development Plan of Debrecen; Debrecen Megyei Jogú Városi Tanácsa VB: Debrecen, Hungary, 1962. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Archi-Comp. Development Programme Proposal of Great Forest; Debrecen, Hungary, 1966. in manuscript. (In Hungarian)

- Grieve, J.; Sherry, E. Community benefits of major sport facilities: The Darebin International Sports Centre. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramio, J.L.; Buraimo, B.; Campos, C. From modern to postmodern: The Development of Football Stadia in Europe. Sport Soc. 2008, 11, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1965 | 1985 | 1997 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| City centre (downtown) | 24 (42.1) | 38 (38.8) | 58 (51.3) |

| Within the city | 28 (49.1) | 31 (31.6) | 26 (23.0) |

| Edge of the city/Suburbs | 5 (8.8) | 29 (29.6) | 29 (25.7) |

| Total | 57 (100.0) | 98 (100.0) | 113 (100.0) |

| City Centre | Within the City | Suburbs/Edge of the City | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Great Britain | 1 | 6 | 1 |

| Spain | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Italy | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Portugal | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Other countries | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Total | 2 | 11 | 20 |

| Importance of the Stadium | Success of the Renovation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| one of the most important elements of the development of the Great Forest | 34.5 | a successful project, which has become one of the key symbols of the city | 42.2 |

| should be mentioned as an important element of the development of the Great Forest, but not the most important one | 49.1 | a successful project, but only one among several elements contributing to the city’s image | 42.2 |

| an average element of the development of the Great Forest | 12.0 | a project of average quality | 6.0 |

| did not play a role in the development of the Great Forest | 4.4 | a fundamentally faulty project | 9.6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kozma, G.; Radics, Z.; Teperics, K. The Role of Sports Facilities in the Regeneration of Green Areas of Cities in Historial View: The Case Study of Great Forest Stadium in Debrecen, Hungary. Buildings 2022, 12, 714. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12060714

Kozma G, Radics Z, Teperics K. The Role of Sports Facilities in the Regeneration of Green Areas of Cities in Historial View: The Case Study of Great Forest Stadium in Debrecen, Hungary. Buildings. 2022; 12(6):714. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12060714

Chicago/Turabian StyleKozma, Gábor, Zsolt Radics, and Károly Teperics. 2022. "The Role of Sports Facilities in the Regeneration of Green Areas of Cities in Historial View: The Case Study of Great Forest Stadium in Debrecen, Hungary" Buildings 12, no. 6: 714. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12060714