Inquiry on Perceptions and Practices of Built Environment Professionals Regarding Regenerative and Circular Approaches

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of Circular and Regenerative Approaches in the Built Environment

“A circular economy is an industrial system that is restorative or regenerative by intention and design. It replaces the ‘end-of-life’ concept with restoration, shifts towards the use of renewable energy, eliminates the use of toxic chemicals, which impair reuse, and aims for the elimination of waste through the superior design of materials, products, systems, and, within this, business models”[13] p. 7.

1.2. Literature Review

- What is the perception and awareness of professionals regarding the application of circular economy and regenerative design concepts in the built environment?

- How do built environment professionals perceive existing sector practices and sustainability tools in the light of circular economy and regenerative design concepts?

- What changes should be implemented to move sector practices and tools towards a regenerative circularity for the built environment?

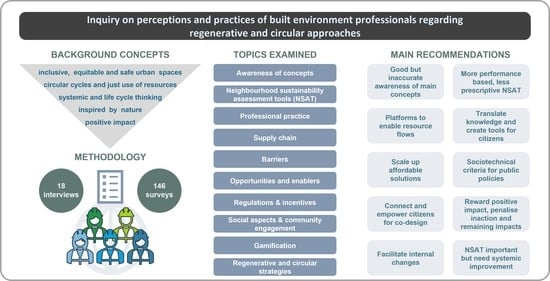

2. Materials and Methods

3. Survey and Interview Findings

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Awareness of Concepts

3.2.1. Circular Economy (CE)

3.2.2. Regenerative Design or Development (RD)

“I can’t adjectivize design. The only thing I can imagine is that when a good design is well done, it brings positive development, the entropy of the process increases in a positive way. It does not have characteristics that allow it to be exclusionary or pejorative or to bring harm to any category of people, environment, or other products. I can only think of regenerative design from this point of view. Regenerative is an adjective that I can’t classify.”(009.SUP_DES.BR)

3.2.3. Planetary Boundaries

3.3. Barriers

3.4. Professional Practice

3.4.1. Perception of Existing Tools

3.4.2. Supply Chain

3.5. Regulations and Incentives

Incentives

3.6. Social Aspects and Community Engagement

“When children are allowed to have full freedom of expression, the results can be really astounding, enjoyable and funny, which is just really refreshing in this field of work.”(003.DES.PT)

Gamification

“Playfulness is also a serious thing. To conduct playful work that generates pleasure, which is also intellectual and affective because you only laugh at things you understand, is a very sophisticated practice.”(005.ACA.BR)

3.7. Moving towards a RC4BE

3.7.1. Importance of Strategies

3.7.2. Opportunities and Enablers

- Working and studying from home will consolidate as an option (although to a lesser degree than during the pandemic) and demand for office spaces will decrease, thus resulting in less commuting, less pollution, and more time for non-work activities.

- Need to invest in and expand open and green spaces, as well as communal public facilities and infrastructure, when there is densification, with attention to cultural issues and public safety.

- Developers focus on short-term profit and regulators do not push design to improve communities.

- Quality of life strongly connected to maximum use of renewable energies and best management of resources.

- Regeneration is very context specific, with a diverse set of possibilities, as the “relationship between ecological functions and quality of life is very steep in a dense city”. Prescriptive approaches may not allow co-evolution.

- Regulations are expected to be tightened for carbon-intensive industries like construction.

- There is a feeling or urgency resulting from the combined set of “humanitarian crisis, health crisis (pandemic), environmental crisis (climate change) and economic crisis”.

3.7.3. Improving Tools

3.7.4. Top Actions to Promote RC4BE

3.7.5. Personal Inspirations

4. Discussions and Recommendations

Future Research Recommendations

- Investigating some of these issues more in-depth with larger samples in specific regions or sub-groups of BE professionals.

- Local opportunities for the implementation of digital platforms as enablers of resource exchange and industrial symbiosis, in line with the use of resources passports. Different pathways have been identified by [84,85]. One important aspect to consider is the access to standardised data that is reliable and comprehensible by different platforms. The development of a ‘Product Circularity Data Sheet’ as part of ISO’s family of standards for the circular economy may be a direction to guide practice [86].

- The use of serious games and other gamified methodologies as a support for participatory planning, awareness, and education process to scale up the application of regenerative and circular concepts in cities [87]. Here, besides traditional analogue approaches as cards and tabletop games, digital technologies may support immersion and visualisation of solutions and proposals for city planning [88].

- Specific enablers and conditions for the use of regenerative circularity in the built environment as a development catalyst in places with poor socioeconomic performance.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Resource Panel. The Weight of Cities: Resource Requirements of Future Urbanization; Full report; IRP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Cities and Biodiversity Outlook, Montreal. 2012. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/health/cbo-action-policy-en.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- McDonald, R.I.; Mansur, A.V.; Ascensão, F.; Colbert, M.; Crossman, K.; Elmqvist, T.; Gonzalez, A.; Güneralp, B.; Haase, D.; Hamann, M.; et al. Research gaps in knowledge of the impact of urban growth on biodiversity. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, K.C.; Dhakal, S.; Bigio, A.; Blanco, H.; Delgado, G.C.; Dewar, D.; Huang, L.; Inaba, A.; Kansal, A.; Lwasa, S.; et al. Human Settlements, Infrastructure and Spatial Planning. In Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Edenhofer, O., Pichs-Madruga, R., Sokona, Y., Farahani, E., Kadner, S., Seyboth, K., Adler, A., Baum, I., Brunner, S., Eickemeier, P., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 923–1000. ISBN 1107654815. [Google Scholar]

- Ulpiani, G. On the linkage between urban heat island and urban pollution island: Three-decade literature review towards a conceptual framework. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoornweg, D.; Hosseini, M.; Kennedy, C.; Behdadi, A. An urban approach to planetary boundaries. Ambio 2016, 45, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UN-DESA. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- Eames, M.; Dixon, T.; May, T.; Hunt, M. City futures: Exploring urban retrofit and sustainable transitions. Build. Res. Inf. 2013, 41, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Built Environment Declares. Built Environment Declares Climate and Biodiversity Emergency. Available online: https://builtenvironmentdeclares.com/ (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Reed, B. Shifting from ‘sustainability’ to regeneration. Build. Res. Inf. 2007, 35, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, C.; Brandon, P. An ecological worldview as basis for a regenerative sustainability paradigm for the built environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 109, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Calisto Friant, M.; Vermeulen, W.J.; Salomone, R. A typology of circular economy discourses: Navigating the diverse visions of a contested paradigm. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 161, 104917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition. Volume 1, United Kingdom. 2013. Available online: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/towards-the-circular-economy-vol-1-an-economic-and-business-rationale-for-an (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Lyle, J.T. Regenerative Design for Sustainable Development; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1994; ISBN 0-471-55582-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mang, P.; Haggard, B. Regenerative Development and Design: A Framework for Evolving Sustainability; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; ISBN 1118972864. [Google Scholar]

- Sala Benites, H.; Osmond, P.; Prasad, D. A neighbourhood-scale conceptual model towards regenerative circularity for the built environment. Sust. Dev. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala Benites, H.; Osmond, P.; Rossi, A.M.G. Developing Low-Carbon Communities with LEED-ND and Climate Tools and Policies in São Paulo, Brazil. J. Urban Plann. Dev. 2020, 146, 4019025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Dawodu, A.; Cheshmehzangi, A. Limitations in assessment methodologies of neighborhood sustainability assessment tools: A literature review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 67, 102739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, M.; Ibrahim, Y.; Mokhtar, H. Optimization of neighbourhood green rating for existing urban forms through mitigation strategies: A case study in Cairo, Egypt. In Proceedings of the 33rd PLEA International Conference, Design to Thrive, Edinburgh, UK, 2–5 July 2017; Brotas, L., Roaf, S., Nicol, F., Eds.; NCEUB: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1717–1724. [Google Scholar]

- Birkeland, J. Net-Positive Design and Sustainable Urban Development, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 9780367258566. [Google Scholar]

- International Living Future Institute. Living Community Challenge 1.2; ILFI: Seattle, WA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://living-future.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Living-Community-Challenge-1-2.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Center for Living Environments and Regeneration. LENSES Overview Guide: How to Create Livng Environments in Natural, Social and Economic Systems; CLEAR: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bioregional. One Planet Goals and Guidance for Communities and Destinations; Bioregional: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hes, D.; Stephan, A.; Moosavi, S. Evaluating the Practice and Outcomes of Applying Regenerative Development to a Large-Scale Project in Victoria, Australia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Forsberg, M.; de Souza, C.B. Implementing Regenerative Standards in Politically Green Nordic Social Welfare States: Can Sweden Adopt the Living Building Challenge? Sustainability 2021, 13, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, N.; Cordella, M.; Traverso, M.; Donatello, S. Level(s)—A common EU Framework of Core Sustainability Indicators for Office and Residential Buildings: Parts 1 and 2: Introduction to Level(s) and How it Works (Draft Beta v1.0); JCR Technical Reports; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hopff, B.; Nijhuis, S.; Verhoef, L.A. New Dimensions for Circularity on Campus—Framework for the Application of Circular Principles in Campus Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adams, K.T.; Osmani, M.; Thorpe, T.; Thornback, J. Circular economy in construction: Current awareness, challenges and enablers. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Waste Resour. Manag. 2017, 170, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qadir, J.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; George, C.T.; Rotimi, J.O. To improve the strategic decision making for effective governance of public-spend regenerative projects. In Proceedings of the 54th International Conference of the Architectural Science Association (ANZAScA), Auckland, New Zealand, 26–27 November 2020; Ghaffarianhoseini, A., Ed.; Architectural Science Association (ANZAScA): Auckland, New Zealand, 2020; pp. 1203–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Munaro, M.R.; Tavares, S.F.; Bragança, L. Towards circular and more sustainable buildings: A systematic literature review on the circular economy in the built environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayuti, N.A.; Sommer, B.; Ahmed-Kristensen, S. Bio-related Design Genres: A Survey on Familiarity and Potential Applications. In Interactivity and Game Creation; Brooks, A., Brooks, E.I., Jonathan, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 379–393. ISBN 978-3-030-73425-1. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, P.; Newman, P. Critical Connections: The Role of the Built Environment Sector in Delivering Green Cities and a Green Economy. Sustainability 2015, 7, 9417–9443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clegg, P. A practitioner’s view of the ‘Regenerative Paradigm’. Build. Res. Inf. 2012, 40, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cole, R.J.; Oliver, A.; Robinson, J. Regenerative design, socio-ecological systems and co-evolution. Build. Res. Inf. 2013, 41, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.; Persram, S. Code, Regulatory and Systemic Barriers Affecting Living Building Projects. Cascadia Region Green Building Council. 2009. Available online: https://living-future.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Code-Regulatory-Systemic-Barriers-Affecting-LB-Projects.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2019).

- Gibbons, L.V.; Pearthree, G.; Cloutier, S.A.; Ehlenz, M.M. The development, application, and refinement of a Regenerative Development Evaluation Tool and indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 108, 105698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, T.; Freitas, T.; Vandewoestijne, S. (Eds.) Nature-Based Solutions: State of the Art in EU-Funded Projects; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; ISBN 978-92-76-17334-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, V.; Barreira, A.P.; Loures, L.; Antunes, D.; Panagopoulos, T. Stakeholders’ Engagement on Nature-Based Solutions: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Pickett, A.C.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S. Neighborhood Physical Environments, Recreational Wellbeing, and Psychological Health. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 14, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanislav, A.; Chin, J.T. Evaluating livability and perceived values of sustainable neighborhood design: New Urbanism and original urban suburbs. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 47, 101517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen Zari, M. Devising Urban Biodiversity Habitat Provision Goals: Ecosystem Services Analysis. Forests 2019, 10, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Romanovska, L. Urban green infrastructure: Perspectives on life-cycle thinking for holistic assessments. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 294, 12011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressanelli, G.; Perona, M.; Saccani, N. Challenges in supply chain redesign for the Circular Economy: A literature review and a multiple case study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 7395–7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dewick, P.; Maytorena-Sanchez, E.; Winch, G. Regulation and regenerative eco-innovation: The case of extracted materials in the UK. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 160, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, K.; van Santen, R.; Kirchherr, J. Policies for transitioning towards a circular economy: Expectations from the European Union (EU). Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munthe-Kaas, P. Agonism and co-design of urban spaces. Urban Res. Pract. 2015, 26, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisonneuve, N.; Stevens, M.; Niessen, M.E.; Hanappe, P.; Steels, L. Citizen Noise Pollution Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 10th International Digital Government Research Conference, Puebla, Mexico, 17–20 May 2009; pp. 96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Coulson, S.; Woods, M.; Scott, M.; Hemment, D.; Balestrini, M. Stop the Noise! Enhancing Meaningfulness in Participatory Sensing with Community Level Indicators. In Proceedings of the 2018 on Designing Interactive Systems Conference 2018—DIS 18. the 2018, Hong Kong, China, 8–12 June 2018; Koskinen, I., Lim, Y., Cerratto-Pargman, T., Chow, K., Odom, W., Eds.; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1183–1192, ISBN 9781450351980. [Google Scholar]

- Eleta, I.; Galdon Clavell, G.; Righi, V.; Balestrini, M. The Promise of Participation and Decision-Making Power in Citizen Science. Citiz. Sci. Theory Pract. 2018, 4, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Talen, E. Do-it-Yourself Urbanism. J. Plan. Hist. 2015, 14, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevens, F.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Gorissen, L.; Loorbach, D. Urban Transition Labs: Co-creating transformative action for sustainable cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampatzidou, C.; Gugerell, K.; Constantinescu, T.; Devisch, O.; Jauschneg, M.; Berger, M. All Work and No Play? Facilitating Serious Games and Gamified Applications in Participatory Urban Planning and Governance. Urban Plan. 2018, 3, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, J.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; George, C.T.; Rotimi, J.O. To understand the systemic and contextual factors to improve the strategic decision making of regenerative projects. In Proceedings of the 54th International Conference of the Architectural Science Association (ANZAScA), Auckland, New Zealand, 26–27 November 2020; Ghaffarianhoseini, A., Ed.; Architectural Science Association (ANZAScA), 2020; pp. 1213–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Li, H.; Zuo, X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, L. A survey and analysis on public awareness and performance for promoting circular economy in China: A case study from Tianjin. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Chen, X.; Geng, Y.; Guo, X.; Lu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, C. Survey of officials’ awareness on circular economy development in China: Based on municipal and county level. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Langen, S.K.; Vassillo, C.; Ghisellini, P.; Restaino, D.; Passaro, R.; Ulgiati, S. Promoting circular economy transition: A study about perceptions and awareness by different stakeholders groups. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, 128166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debacker, W.; Manshoven, S. D1 Synthesis Report on State-of-the-Art Analysis: Key Barriers and Opportunities for Materials Passports and Reversible Building Design in the Current System. BAMB Project—Building as Material Banks. 2016. Available online: http://www.bamb2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/D1_Synthesis-report-on-State-of-the-art_20161129_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Mahpour, A. Prioritizing barriers to adopt circular economy in construction and demolition waste management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 134, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARUP; Ellen MacArthur Foundation. First Steps Towards a Circular Built Environment; ARUP: Austin, TX, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Circular Economy Action Plan. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/circular-economy/pdf/new_circular_economy_action_plan.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2020).

- MMA Chile. Hoja de Ruta Para un Chile Circular al 2040 [Roadmap for a Circular Chile by 2040). Ministerio de Medio Ambiente. 2021. Available online: https://economiacircular.mma.gob.cl/hoja-de-ruta/ (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Construye2025. Hoja de Ruta RCD: Economía Circular en Construcción 2035 [C&DW Roadmap: Circular Economy in Construction], Santiago, Chile. 2020. Available online: https://construye2025.cl/rcd/hoja-de-ruta/ (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Sala Benites, H.; Zegers Cádiz, C. Portafolio de Modelos de Negocios en Economía Circular para la Construcción. Informe Final de la Consultoría [Portfolio of Circular Economy Business Models in Construction. Final Consultancy Report]. Iniciativa de la Hoja de Ruta RCD y Economía Circular en Construcción, PEDN 35718-5, Santiago, Chile. 2021. Available online: https://construye2025.cl/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Portafolio-de-modelos%E2%80%A8-de-negocio-en-economia-circular-para-la-construccion-Informe-final-de-la-consultoria.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Soto, T.; Escrig, T.; Serrano-Lanzarote, B.; Matarredona Desantes, N. An Approach to Environmental Criteria in Public Procurement for the Renovation of Buildings in Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcu, C. Local experiences of urban sustainability: Researching Housing Market Renewal interventions in three English neighbourhoods. Prog. Plan. 2012, 78, 101–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berardi, U. Sustainability assessment of urban communities through rating systems. Env. Dev. Sustain. 2013, 15, 1573–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, M.; Li, C.; Molina, A.; Sturgeon, D. Crafting New Urban Assemblages and Steering Neighborhood Transition: Actors and Roles in Ecourban Neighborhood Development. J. Urban Res. 2016, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781483359045. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, A. How to Conduct Surveys: A Step-by-Step Guide, 6th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781483378480. [Google Scholar]

- Laterza, A. 1º Diagnóstico de Gênero na Arquitetura e Urbanismo: [1st Gender Diagnosis in Architecture and Urbanism]. CAU BR. 2020. Available online: https://www.caubr.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/DIAGN%C3%93STICO-%C3%ADntegra.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Oborn, P.; Walters, J. Planning for Climate Change and Rapid Urbanisation: Survey of the Built Environment Professions in the Commonwealth, Survey Results. 2020. Available online: https://issuu.com/comarchitect.org/docs/survey_of_the_built_environment_profesisons_in_the (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Singer, P. Introdução à Economia Solidária [Introduction to the Solidarity Economy], 1st ed.; Fundação Perseu Abramo: São Paulo, Brazil, 2002; ISBN 85-86469-51-3. [Google Scholar]

- Mang, P.; Reed, B. Designing from place: A regenerative framework and methodology. Build. Res. Inf. 2012, 40, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mang, P.; Reed, B. Regenerative development and design. In Encyclopedia of Sustainability Science and Technology; Meyers, R.A., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 8855–8879. ISBN 978-1-4419-0851-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S.I.; Lambin, E.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.W., III. The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind, 2nd ed.; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972; ISBN 0-87663-165-0. [Google Scholar]

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1603586740. [Google Scholar]

- Marco de la Madre Tierra y Desarrollo Integral para Vivir Bien [Framework of Mother Earth and Integral Development for Living Well]: Ley 300 [Law 300]; Gaceta Oficial del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia: La Paz, Bolivia, 2012.

- ISO. Connecting the Dots in a Circular Economy: A New ISO Technical Committee Just Formed. Available online: https://www.iso.org/news/ref2402.html (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- C40 Cities. Cities100: Salvador—Tax Rebate Incentivizes Building Green. Available online: https://www.c40.org/case_studies/cities100-salvador-tax-rebate-incentivizes-building-green (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- De Byl, P.; Hooper, J. Key Attributes of Engagement in a Gamified Learning Environment. In Proceedings of the 30th Ascilite Conference Proceedings. Electric Dreams, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia, 1–4 December 2013; Macquarie University: Sydney, Australia, 2013; pp. 221–230, ISBN 978-1-74138-403-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, S. Understanding Sustainability and the Australian Property Professions. J. Sustain. Real Estate 2016, 8, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, S.; Gruis, V.; Straub, A. Digitalization for a circular economy in the building industry: Multiple-case study of Dutch social housing organizations. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2022, 15, 200110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, S.; de Wolf, C.; Bocken, N. Circular Digital Built Environment: An Emerging Framework. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M.; Ayed, A.-C.; Wautelet, T. The Product Circularity Data Sheet—A Standardized Digital Fingerprint for Circular Economy Data about Products. Energies 2022, 15, 3397. [Google Scholar]

- Di Mascio, D.; Dalton, R. Using Serious Games to Establish a Dialogue Between Designers and Citizens in Participatory Design. In Serious Games and Edutainment Applications; Ma, M., Oikonomou, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 433–454. ISBN 978-3-319-51643-1. [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou, N.; Papallas, A.; Kostic, Z.; Nacke, L.E. Information Visualisation, Gamification and Immersive Technologies in Participatory Planning. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems—CHI ‘18; Extended Abstracts of the 2018 CHI Conference, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; Mandryk, R., Hancock, M., Perry, M., Cox, A., Eds.; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–4, ISBN 9781450356213. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchini, A.; Rossi, J.; Pellegrini, M. Overcoming the Main Barriers of Circular Economy Implementation through a New Visualization Tool for Circular Business Models. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carra, G.; Magdani, N. Circular Business Models for the Built Environment. 2017. Available online: https://www.arup.com/perspectives/publications/research/section/circular-business-models-for-the-built-environment (accessed on 20 December 2022).

| Topic | Comment | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Awareness | Good CE awareness in UK construction sector (3.3 on a 1–4 scale), but lack of in-depth or unified understanding of CE concepts among built environment stakeholders | [27,28,29,30] |

| Good awareness about bio-related concepts in design. On a 0–1 scale: 0.55 for ‘biophilia’, 0.61 for ‘biophilic design’, 0.79 for ‘bio-inspired design’, and 0.76 for ‘bio-design’. | [31] | |

| 85% of BE professionals in Australia have very high awareness of sustainability challenges and opportunities. Property professionals have inconsistent understanding and use of language. | [32] | |

| Professional practices | 25% of BE professionals prefer to step in with circular practices in low-risk projects. Pathways for CE uptake construction include circular design, new business models (e.g., performance-based contracts and products-as-services), through take-back schemes and material passports facilitating resource loops, and better system conditions through policies, market mechanisms, collaborations, finance, and pilot projects. | [33,34,35,36] |

| Cities still ignore the potential ecosystem services from nature-based solutions (NBS). Main NBS adopted include vegetation abundance and biodiversity, accessibility, naturalness, and wilderness areas, increase in fauna, features to facilitate social interactions, walkways, and water features. | [37,38] | |

| Ease of access to services (walkability) and neighbourhood appearance (attractiveness) seen as important enablers of wellbeing and recreation activities. | [39] | |

| Access to civic and public spaces and recreation facilities, local food production, walkable streets, and local schools are the most valued design elements in LEED-ND. | [40] | |

| Barriers and challenges | Barriers to regenerative solutions include defining boundaries of impacts (local vs. not local), encouraging sustainable lifestyles through design, increasing complexity of projects, constraints of highly urbanised contexts and retrofitting the existing building stock, predicting changes, shifting from site to neighbourhood, including future potentials, predicting performance, codes and regulatory limitations to innovative practices, lack of collective vision, conflicting goals, institutional constraints, implementation challenges, in-the-box-thinking, and broader socioeconomic challenges. | [33,34,35,36] |

| Large-scale regeneration of habitats that existed prior to any urban development taking place may also be a challenge in highly urbanised areas | [41] | |

| Barriers to urban green infrastructure (UGI): large variety of UGI solutions, and accounting for the full range of benefits and impacts, social benefits and costs, and monetised benefits, the dynamic nature of UGI, sensitivity to local conditions, and accounting for cumulative urban-scale impacts have been identified | [42] | |

| Regulations and standards | Fragmented and poorly designed regulatory environments. But changes in regulations without a more holistic approach may not be enough. | [35,43,44] |

| Standards for construction and materials mostly voluntary.CE experts in Europe expect stronger standards and norms for circular production, changes in taxes, expansion and facilitation of circular procurement, global databases and resource exchange platforms, awareness and innovation initiatives, and support for eco-industrial parks. | [45] | |

| Community engagement | Innovative participatory methods: co-design sessions, community engagement in the collection of data, such as air quality or noise through citizen science, “do-it-yourself” or tactical urbanism, urban transition labs, and gamified approaches. | [46,47,48,49,50,51,52] |

| Need to increase early participation of stakeholders in decision-making processes and place everyone on the same page at the start thorough, clear, and straightforward communication. | [53] |

| Interviewee Code * | Gender ** | Subsector | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 001.NGO.BR | F | NGOs or Civil Society | Brazil |

| 002.REG.BR | F | Regulator | Brazil |

| 003.DES.PT | M | Designer | Portugal |

| 004.SUS.BR | F | Sustainability consultant | Brazil |

| 005.ACA.BR | F | Academic | Brazil |

| 006.REG.BR | M | Regulator | Brazil |

| 007.SUP.NL | M | Sustainability consultant | Netherlands |

| 008.SUS.BR | F | Sustainability consultant | Brazil |

| 009.SUP_DES.BR | M | Supplier/Designer | Brazil |

| 010.SUP.AU | F | Supplier | Australia |

| 011.SUS.AU | F | Sustainability consultant | Australia |

| 012.SUS.NL | M | Sustainability consultant | Netherlands |

| 013.SUS.BO | F | Sustainability consultant | Bolivia |

| 014.SUP.BR.AU | M | Supplier | Brazil/Australia |

| 015.SUS.NL | M | Sustainability consultant | Netherlands |

| 016.SUP.BR | M | Supplier | Brazil |

| 017.PM.FI | F | Project manager | Finland |

| 018.REG.CL | F | Regulator | Chile |

| General Barriers | Barriers in the Existing Built Environment | |

|---|---|---|

| Economic and finance viability |

|

|

| Standards and regulations |

|

|

| Market and competition |

|

|

| Value chain management |

|

|

| Technology & knowledge |

|

|

| Product and urban conditions |

|

|

| Stakeholders’ behaviour and awareness |

|

|

| Governance andparticipation |

|

|

| Market and knowledge restrictions |

|

| Performance requirements |

|

| Incompleteness and inadequacy of tools |

|

| Flexibility and adaptability |

|

| Engagement and communication |

|

| New trends and current improvements |

|

| Standards and regulations |

|

| Market and competition |

|

| Value chain management |

|

| Technology & knowledge |

|

| Technology & knowledge |

|

| Governance |

|

| General Opportunities | |

|---|---|

| Economic and finance viability |

|

| Standards and regulations |

|

| Market and competition |

|

| Value chain management |

|

| Technology & knowledge |

|

| Product and urban conditions |

|

| Stakeholders’ behaviour and awareness |

|

| Governance and participation |

|

| Recommendations for Tools’ Improvement | |

|---|---|

| Performance requirements |

|

| Flexibility and adaptability |

|

| Engagement and communication |

|

| Priority Actions or Initiatives to Promote a RC4BE Approach | |

|---|---|

| Economic and finance viability |

|

| Standards and regulations |

|

| Market and competition |

|

| Value chain management |

|

| Technology & knowledge |

|

| Stakeholders’ behaviour and awareness |

|

| Governance and participation |

|

| Theme | Survey (Quanti) | Interview (Quali) | Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of concepts | X | X | There is an overall good understanding of most topics in both quantitative and qualitative. What becomes clear in qualitative is that, while there may be inaccuracies in definitions, there is a connection with their basic principles. |

| Barriers | X | X | There is a high perception of most of 22 topics being a barrier to some extent in quantitative. Out of those, 13 were spontaneously mentioned in some way in qualitative, agreeing with other literature findings. |

| Professional practice | X | Checking environmental information of solutions, projects with net zero aims, and sustainability certifications seem to be a more established practice, whereas on the opposite side, there is still space for the uptake of product certifications, platforms for solutions and recovered resources, circular design, LCA studies, post-occupancy assessment and supply chain engagement. | |

| Perception of tools | X | X | Despite being the second least important strategy identified (Figure 13), certification tools (LEED, AQUA, Green Star, BREEAM, etc.) are still seen as very or extremely important by 46% of survey respondents. They are also seen as the second least relevant barrier to a regenerative and circular approach, with only 34% seeing them as strong or very strong barriers (Figure 6). Many survey respondents mentioned the need to improve tools. Interviewees pointed out that, despite the improvement of some tools and new trends as linkages with ESG requirements for financing, they are generally unable to adequately address regenerative and circular concerns in the built environment. |

| Supply chain | X | X | 64% of quantitative respondents consider supply chain fragmentation a strong or very strong barrier (Figure 6), a perception that also surfaced in qualitative (Table 3). |

| Regulations and incentives | X | X | The survey reveals a general ignorance of local policies to promote or enforce circular or regenerative practices, and a high agreement about the need for more and better circular and regenerative regulations and financial incentives. The perception of a need to improve the current situation is mirrored in the qualitative responses, with specific concerns about poorly developed/enforced regulations or incentives. |

| Social aspects in planning | X | X | There’s widespread agreement, in the survey, that the built environment both impacts on and reflects existing social inequities and environmental injustice. This reflective surfaces in different qualitative responses, with a clear call to address these issues. There is a very clear difference between issues mentioned by interviewees in developing countries, more tied to inequality and lack of access to basic services, and those in more developed countries, where aspects of participation and healthy building materials stood out, but with mentions to affordability. |

| Community engagement | X | X | High level of agreement that all society groups need to be represented in the design of built environment, and a consensus that there should be a balanced bottom-up/top-down in decisions. Interviews revealed existing biases in the participation of only a few majority groups in public audiences and similar events, with a call for more proactive recruitment of the different societal groups, including children. Responses also showed the need for more engagement opportunities and the use of adequate methodologies, as well as the importance of finding a common purpose to unite community groups. |

| Gamification | X | X | In the survey, responses indicate an agreement about the use of gamified methodologies for participatory planning and co-design activities. Interviewees mentioned its importance to better engage people from all groups, convince practitioners about certain approaches, translate complex ideas, and support learning. |

| Importance of strategies | X | There is a high perception that most of the strategies or solutions are important, what could indicate a clear understanding that there is no single solution, but rather the need of a combined and multiple approach. | |

| Opportunities and enablers | X | X | The survey showed a perception that there will be improvements in how we use and design public open spaces and buildings. And while there was no mention to the COVID-19 pandemic, it appeared in the open-ended responses as one of the main reasons for the expected changes. Regarding opportunities and enablers to a regenerative and circular BE, interviewees also mentioned aspects related to the economy, policies, market offers, value chain, technology and knowledge, urban conditions, stakeholder behaviour, and governance. |

| Improving tools | X | Recommendations for the improvement of tools encompassed performance requirements, flexibility, and adaptability to respond to specific context/issues, and aspects of engagement and communication. | |

| Promoting RC4BE | X | Recommendations of priority initiatives to move towards regenerative and circular practices in the built environment are widespread among many different areas of action, such as: economy, policies, market offers, value chain, technology and knowledge, urban conditions, stakeholder behaviour, and governance. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sala Benites, H.; Osmond, P.; Prasad, D. Inquiry on Perceptions and Practices of Built Environment Professionals Regarding Regenerative and Circular Approaches. Buildings 2023, 13, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13010063

Sala Benites H, Osmond P, Prasad D. Inquiry on Perceptions and Practices of Built Environment Professionals Regarding Regenerative and Circular Approaches. Buildings. 2023; 13(1):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13010063

Chicago/Turabian StyleSala Benites, Henrique, Paul Osmond, and Deo Prasad. 2023. "Inquiry on Perceptions and Practices of Built Environment Professionals Regarding Regenerative and Circular Approaches" Buildings 13, no. 1: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13010063

APA StyleSala Benites, H., Osmond, P., & Prasad, D. (2023). Inquiry on Perceptions and Practices of Built Environment Professionals Regarding Regenerative and Circular Approaches. Buildings, 13(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13010063