Evaluating the Impact of Housing Interior Design on Elderly Independence and Activity: A Thematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

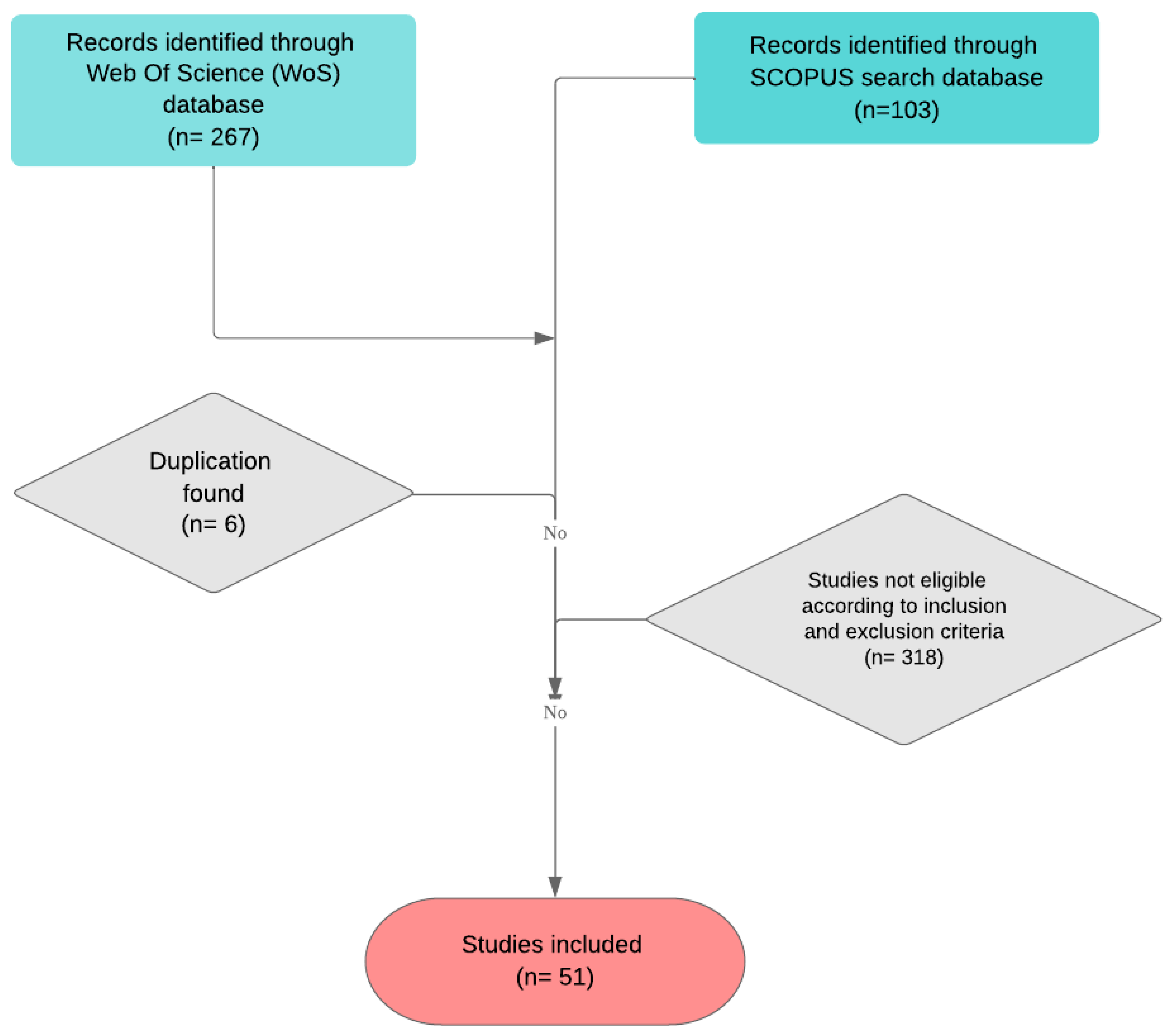

2. Materials and Methods

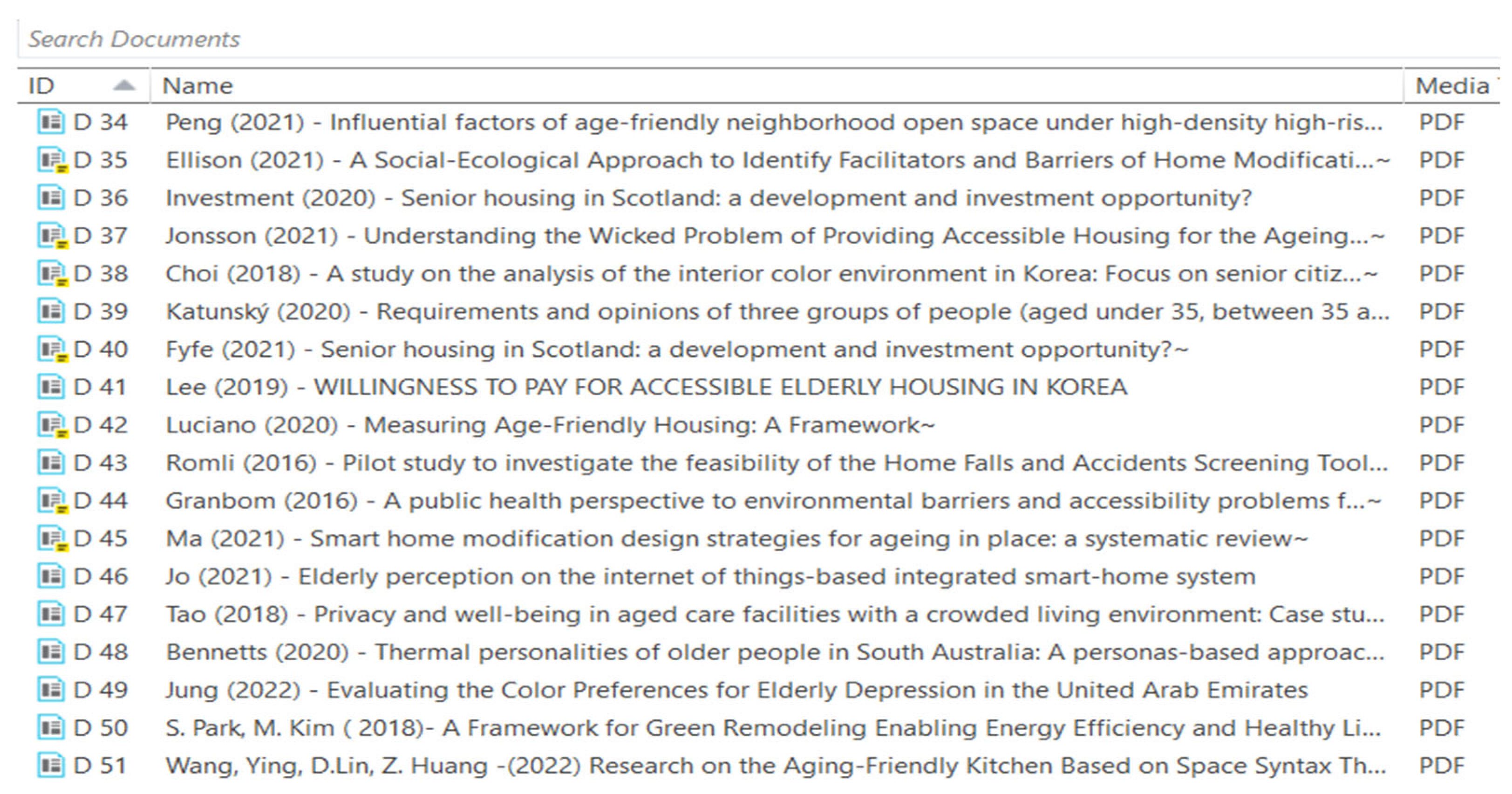

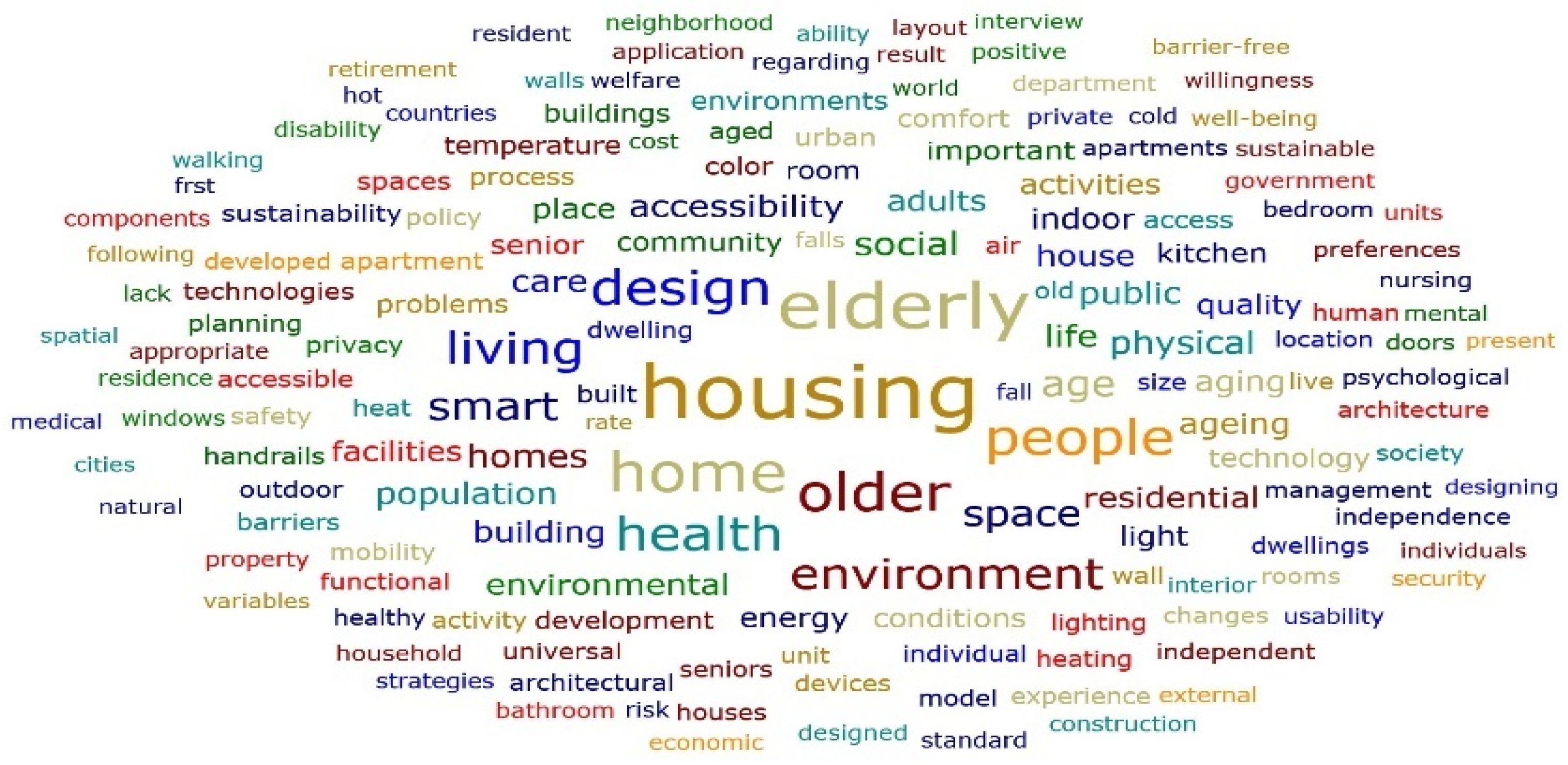

3. Results

4. Quantitative Results

5. Qualitative Results

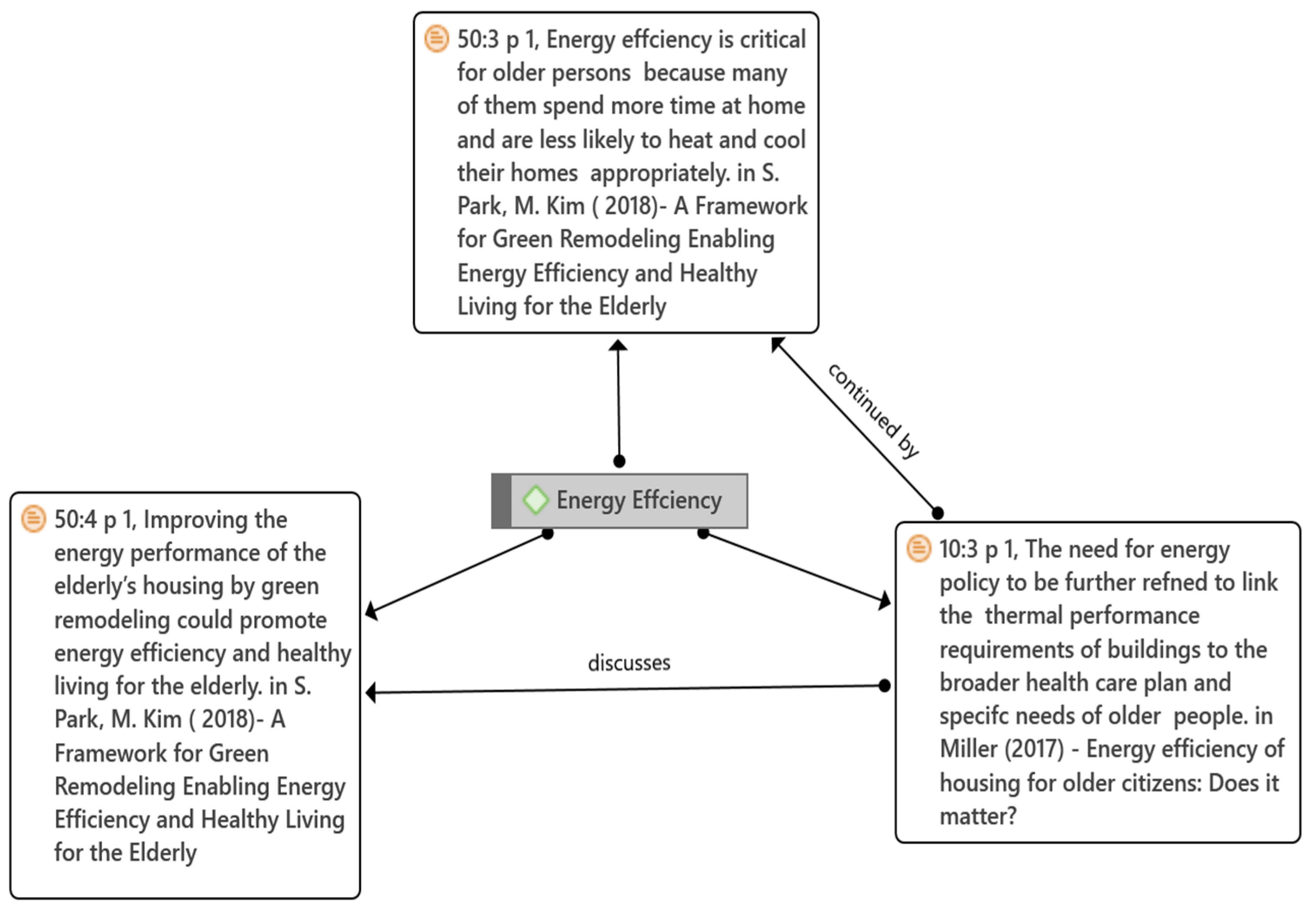

6. Theme 1: Energy Efficiency

7. Theme 2: Architectural Features

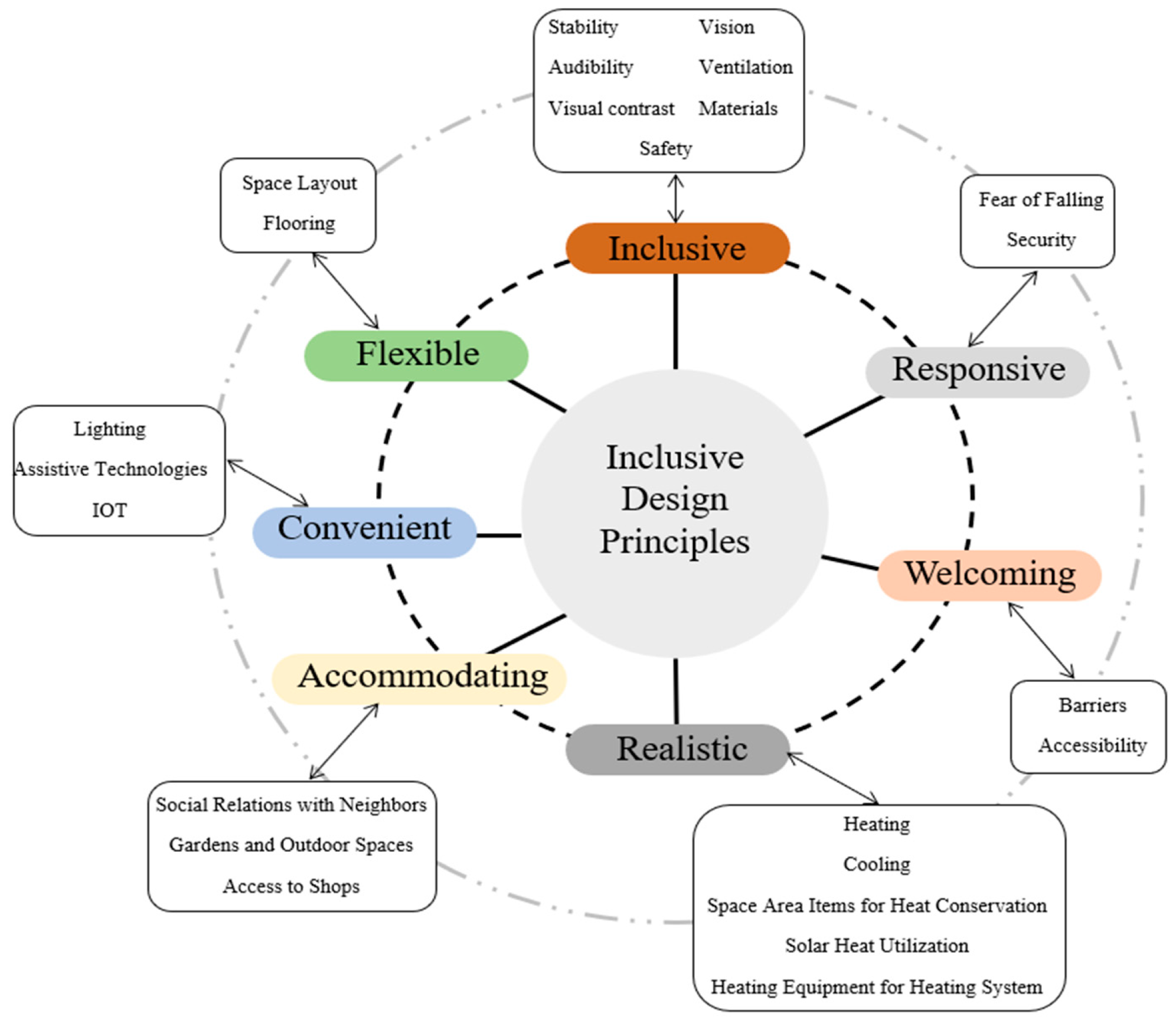

- Space management (space planning and distance);

- Building services (electricity, bathroom, lighting, indoor air, and noise);

- Supporting facilities (windows and doors, decoration, non-slip floors, safety and security, and accessibility).

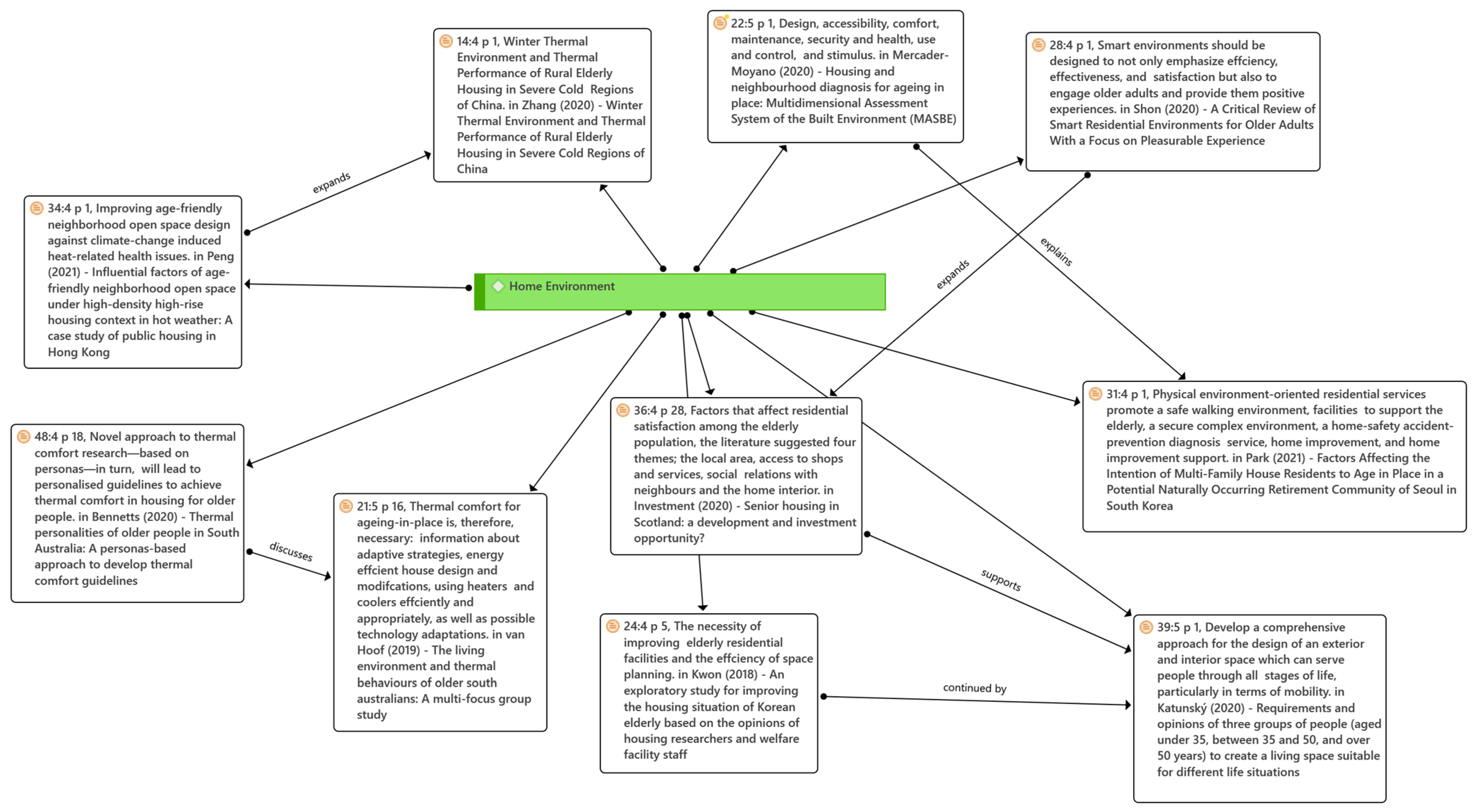

8. Theme 3: Home Environment

9. Discussion

- Architectural features—sub-theme; interior design factors —For basic architectural knowledge of the elderly users, a new practice of elderly house design needs to be developed considering physical aspects (vision, audibility, and stability), psychological aspects (fear of falling, security, safety), and design aspects (accessibility, barriers, flooring, colour, lighting, spaces, and layout, privacy) in interior design for elderly people’s houses;

- Home environment—sub-theme; society and social sustainability—More studies focused on providing a policy that encourages assistive technologies, IoT, gardens and outdoor spaces, local areas, access to shops, social relations with neighbours, environmental cues, and well-being in elderly people’s houses;

- Energy efficiency—sub-theme; energy consumption—Focusing on simulating energy efficiency (heating, cooling, lighting, detailed elements, technology for heat conservation, solar heat utilisation, and detailed plans of the heating system).

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Housing and Health Guidelines; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; p. 149. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550376 (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- Jonsson, O.; Frögren, J.; Haak, M.; Slaug, B.; Iwarsson, S.; Capasso, L.; D’Alessandro, D. Understanding the wicked problem of providing accessible housing for the ageing population in Sweden. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnea, A.; Zairul, M. Housing design studies in Saudi Arabia: A thematic review. J. Constr. Dev. Cities 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.B.; Gottschalk, G. What makes older people consider moving house and what makes them move? House Theory Soc. 2007, 23, 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsamy-Iranah, S.D.; Maguire, M.; Peace, S.; Pooneeth, V. Older adults’ perspectives on transitions in the kitchen. J. Aging Environ. 2021, 35, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engineer, A.; Sternberg, E.M.; Najafi, B. Designing interiors to mitigate physical and cognitive deficits related to aging and to promote longevity in older adults: A review. Gerontology 2018, 64, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afacan, Y. Extending the importance–performance analysis (IPA) approach to Turkish elderly people’s self-rated home accessibility. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2019, 34, 619–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katunský, D.; Brausch, C.; Purcz, P.; Katunská, J.; Bullová, I. Requirements and opinions of three groups of people (aged under 35, between 35 and 50, and over 50 years) to create a living space suitable for different life situations. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 83, 106385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herssens, J.; Nijs, M.; Froyen, H. Inclusive housing (Lab) for all: A home for research, demonstration and information on Universal Design (UD). Assist. Technol. Res. Ser. 2014, 35, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfgang, P.; Korydon, S.H. Universal Desigh Handbook; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-07-162923-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchin, M.; Heylighen, A. Just design. Des. Stud. 2018, 54, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, A.; Pascale, F.; Polverino, F.; Pooley, A. Measuring age-friendly housing: A framework. Sustainability 2020, 12, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zairul, M.; Azli, M.; Azlan, A. Defying tradition or maintaining the status quo? Moving towards a new hybrid architecture studio education to support blended learning post-COVID-19. Archnet IJAR 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zairul, M. A thematic review on student-centred learning in the studio education. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zairul, M. The recent trends on prefabricated buildings with circular economy (CE) approach. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 4, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zairul, M. Opening the pandora’s box of issues in the Industrialised Building System (IBS) in Malaysia: A thematic review. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2021, 25, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.Y.; Yu, J.; Chow, H. Impact of indoor facilities management on the quality of life of the elderly in public housing. Facilities 2016, 34, 564–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romli, M.H.; Mackenzie, L.; Lovarini, M.; Tan, M.P. Pilot study to investigate the feasibility of the Home Falls and Accidents Screening Tool (HOME FAST) to identify older Malaysian people at risk of falls. BMJ Open 2016, 6, 12048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.Y.; Famakin, I.O.; Olomolaiye, P. Effect of facilities management components on the quality of life of Chinese elderly in care and attention homes. Facilities 2017, 35, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuboshima, Y.; McIntosh, J.; Thomas, G. The design of local-authority rental housing for the elderly that improves their quality of life. Buildings 2018, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granbom, M.; Iwarsson, S.; Kylberg, M.; Pettersson, C.; Slaug, B. A public health perspective to environmental barriers and accessibility problems for senior citizens living in ordinary housing. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, D.; Huang, Z. Research on the aging-friendly kitchen based on space syntax theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Lau, S.S.Y.; Gou, Z.; Fu, J.; Jiang, B.; Chen, X. Privacy and well-being in aged care facilities with a crowded living environment: Case study of Hong Kong care and attention homes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Yoshino, H.; Xie, J.; Mao, Z.; Rui, J.; Zhang, J. Winter thermal environment and thermal performance of rural elderly housing in severe cold regions of China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Maing, M. Influential factors of age-friendly neighborhood open space under high-density high-rise housing context in hot weather: A case study of public housing in Hong Kong. Cities 2021, 115, 103231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Q.; Liu, H. Application of artificial intelligence computing in the universal design of aging and healthy housing. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 4576397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercader-Moyano, P.; Flores-García, M.; Serrano-Jiménez, A. Housing and neighbourhood diagnosis for ageing in place: Multidimensional Assessment System of the Built Environment (MASBE). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 62, 102422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawlak, A.; Matuszewska, M.; Skorka, A. Housing expectations of future seniors based on an example of the inhabitants of Poland. Buildings 2021, 11, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, K.; Mikolajczak, E. Senior housing universal design as a development factor of sustainable-oriented economy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Oyegoke, A.S.; Sun, M. Adaptations for aging at home in the UK: An evaluation of current practice. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2019, 32, 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Yoo, S.E. Willingness to pay for accessible elderly housing in Korea. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2020, 24, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.; Kim, D.; Kim, J. An exploratory study for improving the housing situation of Korean elderly based on the opinions of housing researchers and welfare facility staff. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2018, 16, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shon, S.; Gu, N.; Kwon, H.J.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, L.N. A critical review of smart residential environments for older adults with a focus on pleasurable experience. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, E.; De Haan, H.; Vaandrager, L.; Koelen, M. Beyond thresholds: The everyday lived experience of the house by older people. J. Hous. Elder. 2015, 29, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lektip, C.; Rattananupong, T.; Sirisuk, K.O.; Suttanon, P.; Jiamjarasrangsi, W. Adaptation and Evaluation of Home Fall Risk Assessment Tools for the Elderly in Thailand. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2020, 51, 65–76. Available online: https://journal.seameotropmednetwork.org/index.php/jtropmed/article/view/112 (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Ahrentzen, S.; Tural, E. The role of building design and interiors in ageing actively at home. Build. Res. Inf. 2015, 43, 582–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granbom, M.; Slaug, B.; Löfqvist, C.; Oswald, F.; Iwarsson, S. Community relocation in very old age: Changes in housing accessibility. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2016, 70, 16147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossokina, I.V.; Arentze, T.A.; van Gameren, D.; van den Heuvel, D. Best living concepts for elderly homeowners: Combining a stated choice experiment with architectural design. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2019, 35, 847–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, M. A framework for green remodeling enabling energy efficiency and healthy living for the elderly. Energies 2018, 11, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, B.; Markvart, J.; Kessel, L.; Argyraki, A.; Johnsen, K. Can sleep quality and wellbeing be improved by changing the indoor lighting in the homes of healthy, elderly citizens? Chronobiol. Int. 2015, 32, 1049–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.; Vine, D.; Amin, Z. Energy efficiency of housing for older citizens: Does it matter? Energy Policy 2016, 101, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.W.Y.; Fung, I.W.H.; Tsang, Y.T.; Chan, L. Development of a universal design-based guide for handrails: An empirical study for Hong Kong elderly. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Jimenez, M.L.; Antonio, V.-Y. Key elements for a new Spanish legal and architectural design of adequate housing for seniors in a pandemic time. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S. Redesigning Domesticity Creating Homes. Archit. Des. 2014, 84, 80–87. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ad.1732 (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Van Hoof, J.; Bennetts, H.; Hansen, A.; Kazak, J.K.; Soebarto, V. The living environment and thermal behaviours of older south australians: A multi-focus group study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thordardottir, B.; Fänge, A.M.; Chiatti, C.; Ekstam, L. Participation in everyday life before and after a housing adaptation. J. Hous. Elder. 2018, 33, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Chung, J.H.; Kim, J. Study on Developing the Assisting Program for Customized Housing Design for the Elderly. Research Gate. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308119760_Study_on_developing_the_assisting_program_for_customized_housing_design_for_the_elderly (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Tsuchiya-Ito, R.; Iwarsson, S.; Slaug, B. Environmental challenges in the home for ageing societies: A comparison of Sweden and Japan. J. Cross. Cult. Gerontol. 2019, 34, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Allweil, Y. Towards non-ageist housing and caring in old age. Urban Plan. 2020, 5, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, H.; Nazari, J.; Choobineh, A.; Morowatisharifabad, M.A.; Jafarabadi, M.A. Identifying Barriers and Problems of Physical Environment in Older Adults’ Homes: An Ergonomic Approach. Work 2021, 70, 1289–1303. Available online: https://content.iospress.com/articles/work/wor210765 (accessed on 18 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Ham, S.; Cho, H.; Lee, H.; Lee, G. Prototype Development of Responsive Kinetic Façade Control System for the Elderly Based on Ambient Assisted Living. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2019, 62, 273–285. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00038628.2019.1614902 (accessed on 18 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-A.A.; Choi, B. Factors affecting the intention of multi-family house residents to age in place in a potential naturally occurring retirement community of Seoul in South Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borelli, E.; Paolini, G.; Antoniazzi, F.; Barbiroli, M.; Benassi, F.; Chesani, F.; Chiari, L.; Fantini, M.; Fuschini, F.; Galassi, A.; et al. HABITAT: An IoT solution for independent elderly. Sensors 2019, 19, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkan, H.; Olguntuerk, N. A priority-based ‘design for all’ approach to guide home designers for independent living. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2013, 57, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, C.; Struckmeyer, L.; Kazem-Zadeh, M.; Campbell, N.; Ahrentzen, S.; Classen, S. A social-ecological approach to identify facilitators and barriers of home modifications. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fyfe, A.; Hutchison, N. Senior housing in Scotland: A development and investment opportunity? J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2020, 39, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Lee, H.; Park, H. A Study on the Analysis of the Interior Color Environment in Korea: Focus on Senior Citizen Centers in Korea. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2018, 13, 7857–7864. Available online: https://medwelljournals.com/abstract/?doi=jeasci.2018.7857.7864 (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Ma, C.; Guerra-Santin, O.; Mohammadi, M. Smart home modification design strategies for ageing in place: A systematic review. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2021, 37, 625–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, T.H.; Ma, J.H.; Cha, S.H. Elderly perception on the internet of things-based integrated smart-home system. Sensors 2021, 21, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennetts, H.; Martins, L.A.; van Hoof, J.; Soebarto, V. Thermal personalities of older people in South Australia: A personas-based approach to develop thermal comfort guidelines. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukhobodskiy, A.A.; Zaitcev, A.; Pogarskaia, T.; Colantuono, G. RED WoLF hybrid storage system: Comparison of CO2 and price targets. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toosi, H.A.; Del Pero, C.; Leonforte, F.; Lavagna, M.; Aste, N. Machine learning for performance prediction in smart buildings: Photovoltaic self-consumption and life cycle cost optimization. Appl. Energy 2023, 334, 120648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Koo, B.; Park, B.; Ahn, Y.H. The development of an energy-efficient remodeling framework in South Korea. Habitat Int. 2016, 53, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, N. Heating, Cooling, Lighting: Sustainable Design Methods for Architects, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 9781118582428. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, E.; Cummings, L.; Sixsmith, A.; Sixsmith, J. Impacts of home modifications on aging-in-place. J. Hous. Elder. 2011, 25, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromp, N.; Hekkert, P. Assessing methods for effect-driven design: Evaluation of a social design method. Des. Stud. 2016, 43, 24–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Abdelaziz Mahmoud, N.S.; El Samanoudy, G.; Al Qassimi, N. Evaluating the color preferences for elderly depression in the United Arab Emirates. Buildings 2022, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.; Buffel, T. Aging in place and the places of aging: A longitudinal study. J. Aging Stud. 2020, 54, 100870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, J.A.; Hernandez, S.C. Universal design, design for aging in place, and habilitative design in residential environments. In Health and Well-Being for Interior Architecture; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 137–147. ISBN 9781315464411. [Google Scholar]

- Stichler, J.F. Design considerations for aging populations. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2013, 6, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, H. The Principles of Inclusive Design; (They Include You). 2006. Available online: www.cabe.org.uk (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- Morgan, A.S.; Dale, H.B.; Lee, W.E.; Edwards, P.J. Deaths of cyclists in London: Trends from 1992 to 2006. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World Population Prospects 2022 Summary of Results; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Steps | Description |

|---|---|

| Formulating the research questions | The research question is defined and functions as a road map for the following steps. Its relevant components are specified and will influence search tactics. Research questions are broadly defined to allow coverage breadth. |

| Article screening | Identifying pertinent studies and deciding on a search location, terms to use, sources to search, time span, and language are components of this stage. Comprehensiveness and breadth are essential when searching for articles. Sources comprise electronic databases, reference lists, hand-searching of significant publications, and organisations and conferences. Search breadth and search practicalities are both vital. The results desired by the author will be yielded by the correct keywords. |

| Article filtering | Study selection uses inclusion and exclusion criteria. The criteria are defined by the research question and study aim, in addition to new knowledge gained by reading the papers. In order to ensure the correct selection of articles, they will be filtered and inserted into Mendeley for further refinement and a final round of filtering. |

| Cleaning and finalising selected articles | Article metadata will be double-checked in Mendeley to ensure that only relevant articles are chosen for the analysis process. |

| Data extraction and synthesis | A thematic analysis process is utilised to develop themes based on extensive reading on the subject. The themes are chosen for consistency by the iterative evaluation of similarities and differences in the publications examined. The data will be entered into ATLAS.ti software, which will extract the data for thematic review. Quantitative data used to analyse the numerical portions are taken from general bibliometric information. In the qualitative study of the subsequent topic analysis, the thematic review uses a similar coding strategy. This step is considered as fragmenting and decreasing data and, to some extent, distorting the dialectic relationship between reading text and writing. |

| Web of Science | elderly house design OR aging house design AND elderly house AND elderly interior design studies (All Fields) and English (Languages) and Open Access and 2022 or 2021 or 2020 or 2019 or 2018 or 2017 or 2016 or 2015 or 2014 or 2013 (Publication Years) and Articles (Document Types) | 267 results |

| Scopus | elderly AND house AND design OR aging AND house AND design AND elderly AND house AND elderly AND interior AND design AND studies AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBSTAGE, “final”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (OA, “all”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2022) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2021) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2020) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2019) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2018) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2017) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2016) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2015) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2014) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2013)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (SRCTYPE, “j”)) | 103 results |

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Architectural Science Review | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 2 |

| BMC Public Health | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| BMJ Open | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Building Research & Information | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Buildings | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Cities | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | |

| Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Energies | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Energy Policy | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Environmental Impact Assessment Review | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Facilities | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 2 |

| Frontiers in Psychology | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| International Journal of Strategic Property Management | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| Journal of Aging & Social Policy | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| Journal of Aging and Environment | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| Journal of Asian Architecture and Building | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| Journal of Housing and the Built Environment | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | 1 | - | 3 |

| Journal of Housing For the Elderly | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 2 |

| Journal of Property Investment & Finance | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | 2 |

| Sustainability | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | - | 6 |

| Sustainable Cities and Society | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| The American Journal of Occupational | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| The Journal of Biological and Medical Rhythm Research | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Urban Planning | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Architectural Design | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| The Online Journal of New Horizons in Education | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| National Centre for Biotechnology Information | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Sensors | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 2 |

| Totals | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 12 | 3 | 51 |

| Reference | Energy Efficiency | Home Design | Home Environment |

|---|---|---|---|

| [5] | √ | ||

| [34] | √ | ||

| [35] | √ | ||

| [36] | √ | ||

| [30] | √ | ||

| [37] | √ | ||

| [38] | √ | ||

| [39] | √ | ||

| [29] | √ | ||

| [40] | √ | ||

| [41] | √ | ||

| [19] | √ | ||

| [20] | √ | ||

| [17] | √ | ||

| [24] | √ | ||

| [42] | √ | ||

| [28] | √ | ||

| [43] | √ | ||

| [26] | √ | ||

| [44] | √ | ||

| [45] | √ | ||

| [27] | √ | ||

| [46] | √ | ||

| [32] | √ | ||

| [47] | √ | ||

| [48] | √ | ||

| [49] | √ | ||

| [33] | √ | ||

| [50] | √ | ||

| [51] | √ | ||

| [52] | √ | ||

| [53] | √ | ||

| [54] | √ | ||

| [25] | √ | ||

| [55] | √ | ||

| [56] | √ | ||

| [2] | √ | ||

| [57] | √ | ||

| [8] | √ | ||

| [56] | √ | ||

| [31] | √ | ||

| [12] | √ | ||

| [18] | √ | ||

| [21] | √ | ||

| [58] | √ | ||

| [59] | √ | ||

| [23] | √ | ||

| [60] | √ | ||

| [59] | √ | ||

| [22] | √ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mnea, A.; Zairul, M. Evaluating the Impact of Housing Interior Design on Elderly Independence and Activity: A Thematic Review. Buildings 2023, 13, 1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13041099

Mnea A, Zairul M. Evaluating the Impact of Housing Interior Design on Elderly Independence and Activity: A Thematic Review. Buildings. 2023; 13(4):1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13041099

Chicago/Turabian StyleMnea, Aysha, and Mohd Zairul. 2023. "Evaluating the Impact of Housing Interior Design on Elderly Independence and Activity: A Thematic Review" Buildings 13, no. 4: 1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13041099

APA StyleMnea, A., & Zairul, M. (2023). Evaluating the Impact of Housing Interior Design on Elderly Independence and Activity: A Thematic Review. Buildings, 13(4), 1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13041099