Abstract

Semi-outdoor learning spaces are becoming increasingly popular with both students and teachers at tropical universities; however, some of the seats are always vacant. This study focused on the selection of seating in semi-outdoor spaces in a university environment in Singapore. The methods included onsite measurements and a questionnaire to explore the factors that influence user seating preferences in terms of the physical environment, spatial perception, and the seating facilities. The study also explored factors that affect users’ lengths of stay in such spaces. It found that users attached a great importance to the thermal comfort of semi-outdoor spaces. They preferred sheltered seating and seats with views of the surrounding landscape. In addition, the study found that the higher the quality of seating facilities, the longer users spent on site. The results of this study may inform the design and layout of seating in semi-outdoor university learning spaces.

1. Introduction

Singapore, a tropical country, has a hot and humid climate. Focusing on tropical universities, this study demonstrates the benefits of improving thermal comfort by promoting the use of semi-outdoor spaces [1]. Research has suggested that students at tropical universities increasingly choose to study in library cafés, which are usually located in semi-outdoor spaces on campus [2]. Promoting diversity, openness, and sharing, semi-outdoor spaces have become an essential place in which students and teachers can communicate and rest [3].

The relationship between the physical environment and seat selection has received considerable scholarly attention. In terms of the lighting, Llinares [4] found correlations between lighting and students’ cognitive responses. Tunahan [5] found that daylight was the major determinant of students’ selection of desks. Lu [6] reported that access to shade was the most important environmental element that affected seating preference and behavior. As for thermal comfort, a very recent [7] study investigated the personalized comfort models in Singapore and found that air velocity is an important determinant. Chen [8] proposed that access to favorable thermal microclimate conditions can increase the usage frequency of seats. Lyu [9] proposed that thermal pleasure contributes to the restorative properties of workplace semi-outdoor environments, specifically in relation to attention restoration, stress recovery, and mood improvement. Ji [10] found that choosing appropriate underlay materials and increasing tree size, leaf area density, or planting density improved thermal comfort in semi-outdoor spaces.

Scholars have noticed that user spatial perception of seating affects their seat selection and length of stay. Gehl found that people preferred aisle seats that were semi-covered and offered good views [11]. Marcus [12] emphasized the importance of site boundaries and suggested that leisure seating should be placed in locations that are easily accessible and visible to users. Ohno [13] reported that the presence of other people in the same area was not always perceived negatively; indeed, it could even be positive as long as they stayed at a certain distance from the user. Several scholars have suggested that seating design should take user privacy into consideration [14,15]. Chen [16] found in a study of college cafeterias that people preferred to dine in locations near the main walkway, at the edges of small spaces, and with backing. Based on a questionnaire survey and regression analysis, Gou [17] found that in addition to privacy factors, an outdoor view was an important factor affecting seating preferences, concluding that a sky view and sunshade were positively correlated with occupancy rates. Chen [18] demonstrated the important role of window views in learning spaces.

At the beginning of the 21st century, scholars began to focus on the relationship between seating facilities and seating preferences [19,20]. Robson [21] suggested that occupants’ seating-related perceptions and behaviors are significantly influenced by the location and configuration of the seats they occupy. Waxman [22] found that people were more likely to spend time in clean, comfortable seating areas with a pleasant aroma. Yeh [23] stated that users value easy-to-clean furniture that can be easily moved and rearranged. Alpak [24] found that the provision of easily rearrangeable outdoor furniture made open spaces more attractive. In 2021, Xu [25] found that the accessibility of outdoor seating spaces and the quality of facilities increased the usage of seating spaces. Tadepalli [26] again emphasized the importance of movable furniture to facilitate adaptive behavior when the original space does not provide the airflow required for thermal comfort.

Based on a literature review, the authors found that studies of seating preferences have mostly been conducted in indoor spaces (offices, restaurants, libraries, etc.) or large-scale outdoor environments (parks, commercial streets, residential areas, etc.). Few studies have focused on seating preferences in semi-outdoor spaces on tropical campuses. However, semi-outdoor spaces play an important role in the tropics, so seating preferences in these spaces are highly significant and are affected by many factors. To fill this gap in the literature, the current study evaluated seating preferences in a semi-outdoor space at a tropical university based on user satisfaction and environmental parameters. This study aimed to explore the specific factors influencing people’s seating preference and provide feasible suggestions for designing seating in similar semi-outdoor spaces.

2. Study Design and Data Collection

2.1. Research Methodology

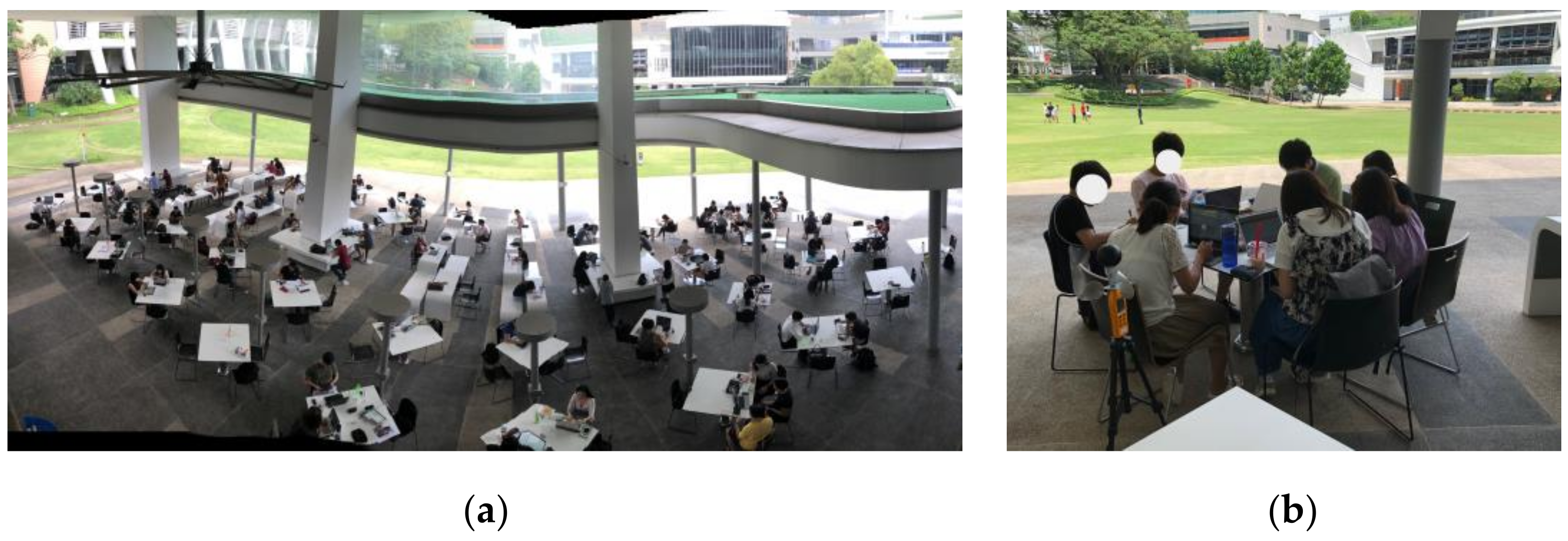

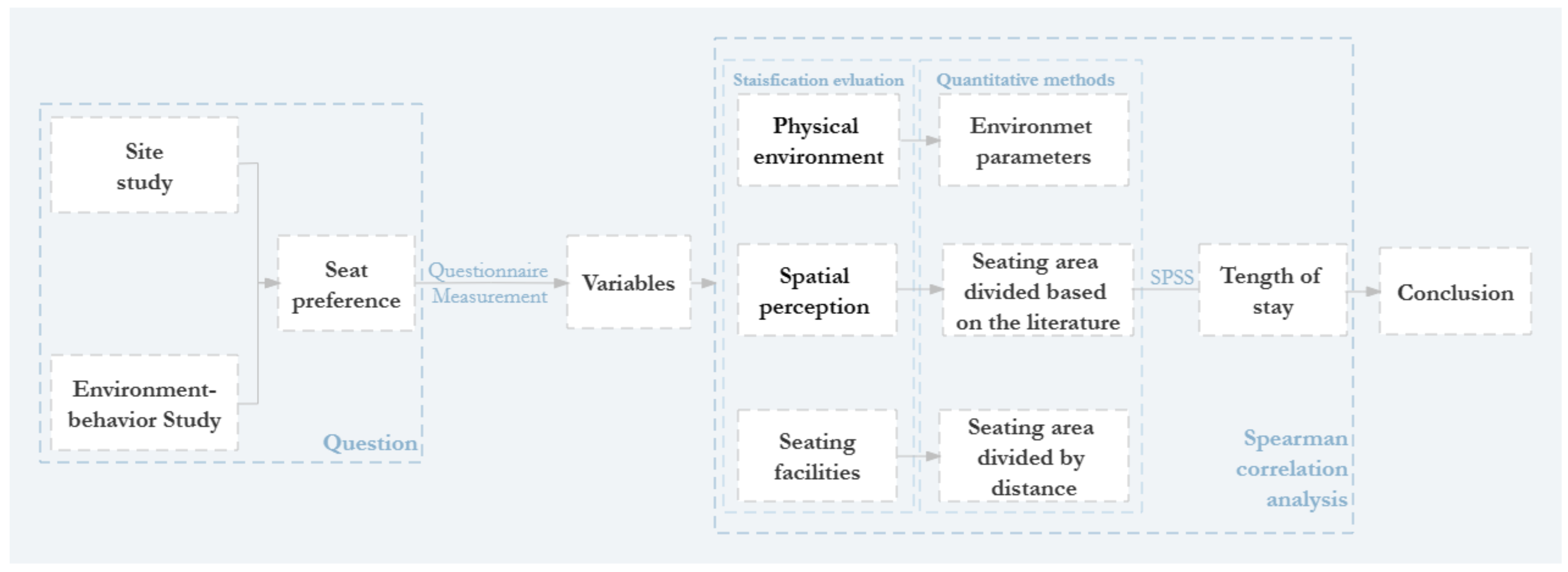

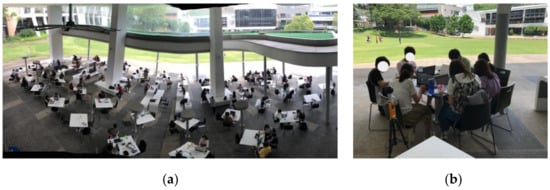

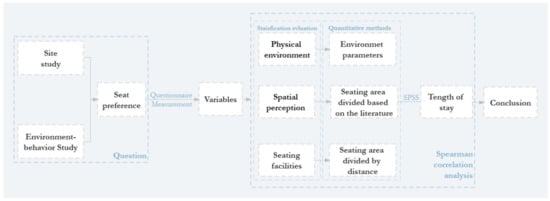

In this study, 202 questionnaire responses were collected on the first floor of the National University of Singapore (NUS) Education Resource Center (ERC) (Figure 1), of which 192 were valid. While each user was filling out the questionnaire, physical environment parameters were measured by an innovative handheld heat stress monitor, which can simultaneously measure temperature, humidity, globe bulb outdoor, wind speed, and WGBT outdoor data (Table 1). The location of the device was set within 0.5 m from the seat, and the height was 1.2 m. The data were processed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26. Based on the differences in site conditions, the data were analyzed in two ways, as follows. Method 1: a correlation analysis was performed between satisfaction with specific factors and length of stay. Method 2: when significant differences were observed between the elements of the site (e.g., physical environment and landscape view), the seats were quantified and assigned to hierarchical levels. The correlation between the quantified results and user satisfaction were analyzed by a Spearman correlation analysis to explore whether each factor was correlated with seating preference (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Status of the site: (a) aerial view of semi-outdoor space and (b) view from the site.

Table 1.

The details of the handheld heat stress monitor.

Figure 2.

The flow diagram of research design.

2.2. Research Subjects

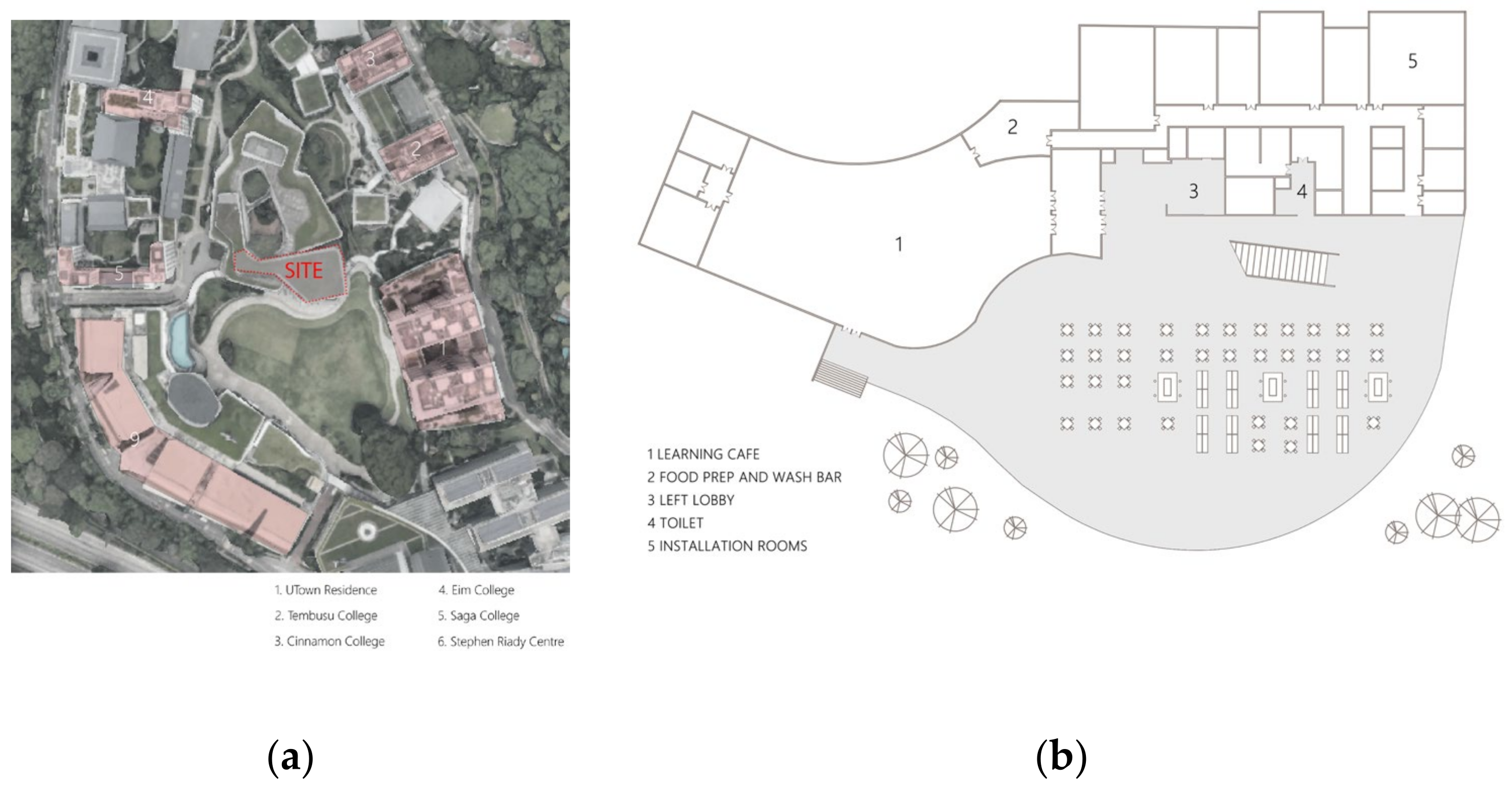

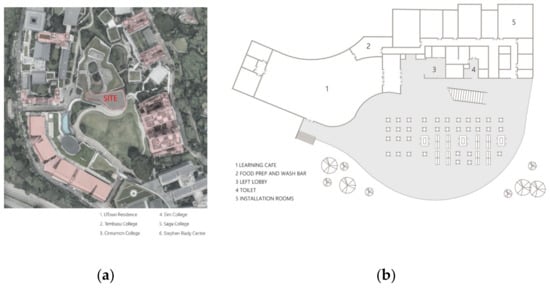

This study was conducted at the ERC in NUS University Town. The ERC is located in the teaching and dormitory area. Every day, many people pass through the ERC, which offers good accessibility. This study focused on a semi-outdoor space (Figure 3) on the east side of Starbucks on the first floor of the ERC, which has a green grassy terrace on its south side. From this space, users can view the whole green space and enjoy the natural landscape. The landscape on the south site is a lawn, with trees on the east and west sides. The north side of the semi-outdoor space comprises various ancillary service spaces: shops, bathrooms, stairs, etc. A total of 45 tables are placed inside the venue. Different seat forms can meet the various demands of study activities. Each seat is located in a different location in the semi-outdoor space, and there are differences in the surrounding facility packages and landscape views. Therefore, this space was a valuable setting for the current study.

Figure 3.

The location of the area: (a) the ERC general plan and (b) ERC ground floor plan.

The population of this survey comprised the users of seating inside the venue. The daily temperature range of Singapore has a minimum usually not falling below 23–25 °C during the night and maximum not rising above 31–33 °C during the day. According to one study, the thermal comfort of semi-outdoor spaces is highest at noon and in the afternoon [1], so the questionnaire survey was undertaken from 11:00 to 16:00 during the initial study period, i.e., on 6–8 August 2018, which were all weekdays. However, some of the seats were rarely occupied during the initial study period. Therefore, questionnaire data for the remaining seats were obtained on 29 August.

2.3. Questionnaire Design and Content

The study was based on the theory of environmental behavior research. The variables were selected based on this and the characteristics of the site. The questionnaire (Table 2) had the following three main parts. The first part collected basic information of the respondents, including gender, age, and education; the second part investigated their use of the seats, including their length of stay and factors affecting their seat selection from a psychological perspective; and the third part was a satisfaction evaluation, designed using the Likert scale. The survey respondents rated their satisfaction with the position they were sitting in at the time of the questionnaire, measured on a scale from “very dissatisfied” to “very satisfied”. The length of stay indicated the users’ place attachment, and the results of the questionnaires revealed the subjective evaluation of each factor.

Table 2.

Seating preference satisfaction questionnaire.

3. Data Analysis and Results

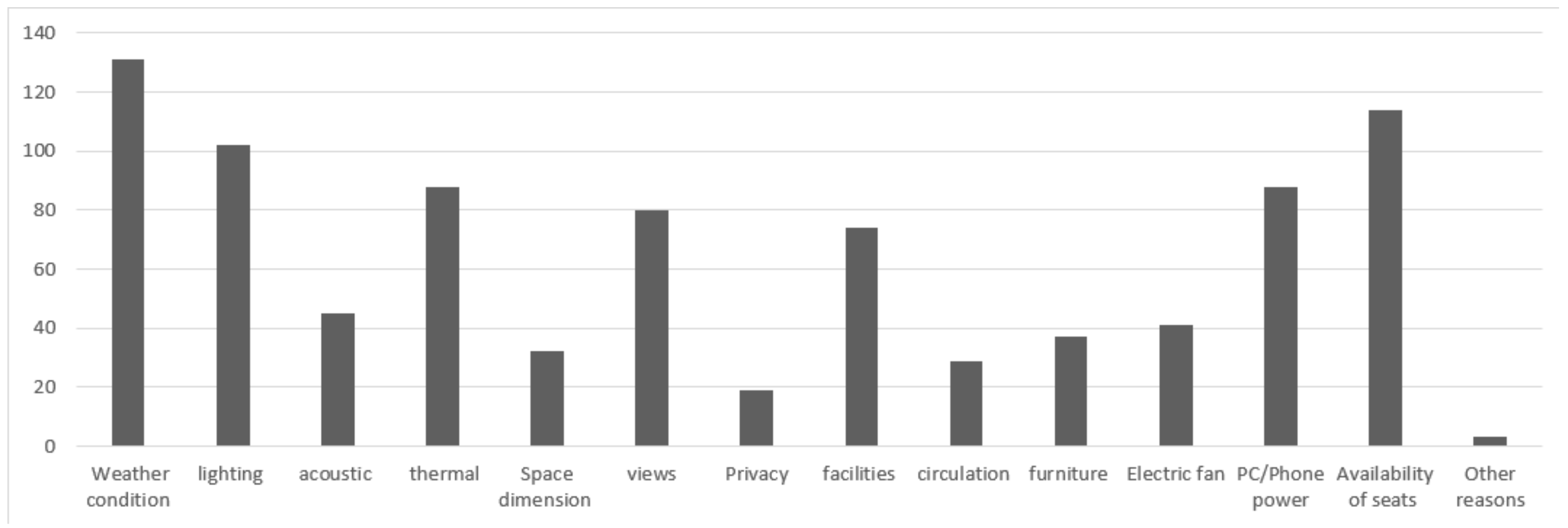

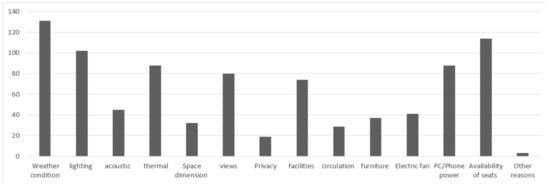

The questionnaire responses were collected from 97 women and 95 men, which represented a good gender balance. Half of them were undergraduate students (51%) and the other half were postgraduates and other users of the ERC. Therefore, the sample covered most of the people who used this space at the ERC. Users in the venue wear typical tropical clothing ensemble (briefs, shorts, open neck shirt with short sleeves, light socks, and sandals) or light summer clothing (briefs, long high weight trousers, open neck shirt with short sleeves, light socks, and shoes), which have a thermal resistance of 0.3–0.5 clo. [27]. The data showed that most of the users engaged in multiple activities here, mainly studying (99 visits) and communicating with others (81 visits). The length of stay was rather dispersed across users, with relative concentrations of one hour (22%) and two hours (25%). Regarding the factors affecting people’s seat selection, the study first analyzed the responses to the question “What influences your seat selection?“ (Figure 4). The majority of the respondents thought that weather factors and the availability of seats affected their seat selection, followed by lighting, the thermal environment, and power supply, which were closely followed by landscape and facilities. Some users also suggested that the crowdedness of the site and the cleanliness of the seats affected their seat selection. The most important factors reported by the respondents were divided into three categories: physical environment, spatial perception, and seating facilities. Next, the satisfaction scores for each element were analyzed.

Figure 4.

The number of people influenced by various factors affecting user seat selection.

3.1. Analysis of Physical Environment

As for the relationship between the physical environment and seat selection, this study found that the respondents prioritized aspects of the physical environment such as weather, temperature, and light when selecting seats. Of the 192 questionnaire respondents, 131 believed that the weather had a very important impact on their seat selection. However, a correlation analysis showed that the weather was not related to the users’ weather satisfaction (p = 0.231). Although the users were very concerned about the weather, as they had different preferences regarding weather conditions, this factor did not affect their seat selection behavior.

A total of 192 valid data were collected from the venue, and based on the statistical data description (Table 3), the highest dry bulb temperature recorded was 31.9 °C. The research was carried out on the hottest day, with the maximum temperature reaching 33 °C, which was higher than the maximum value of dry bulb temperature in the semi-outdoor space. This proved that semi-outdoor space provides a cooler environment for users. Moreover, the average temperature of the black ball inside the venue was 29.9 °C, with a temperature difference of 7.7 °C between the highest and lowest temperatures. The average value of WGBT is 26.3 °C, with a temperature difference of 3.3 °C between the highest and lowest temperatures. In terms of wind speed, the average wind speed was 1.249 m/s, with a difference of 6.9 m/s. As for humidity, the average value of relative humidity inside the site was 69.333%, with a range from 54.6% to 82%.

Table 3.

Summary of the environmental parameters.

Based on research on the indices of outdoor thermal comfort, in addition to basic parameters such as humidity, temperature, and wind speed, the wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) was selected as a thermal comfort index for semi-outdoor spaces in hot and humid climates in [28]. However, there was no correlation between user overall comfort and WBGT in this study (p = 0.442). The correlation between the thermal environment and user satisfaction indicated that the overall comfort felt by the participants was related to dry temperature (r = −0.168, p = 0.05), black ball surface temperature (r = −0.176, p = 0.05), and relative humidity (r = 0.179, p = 0.05). Users tended to choose seats in environments with a lower temperature and a higher humidity. There was no correlation between ventilation satisfaction and wind speed (p = 0.962). A possible explanation is that fans may affect users’ evaluation of ventilation satisfaction.

3.2. Analysis of Spatial Perception

Spatial perception was defined in this study as a user’s psychological perception of the space in which their seat is located during their use of the seat. According to prospect–refuge theory [29], factors that affect people’s choice of environment to stay in is whether the location is sheltered, offers an expansive view of its surroundings, maintains a proper distance from others, is convenient for communication, and cannot easily be disturbed. Based on this theory, this study divided the evaluation of spatial perception into three dimensions: (1) privacy (ensuring that one’s position is not easily observed by others); (2) accessibility (keeping a distance from others and ensuring that one is not easily disturbed); and (3) an open view of the surrounding landscape.

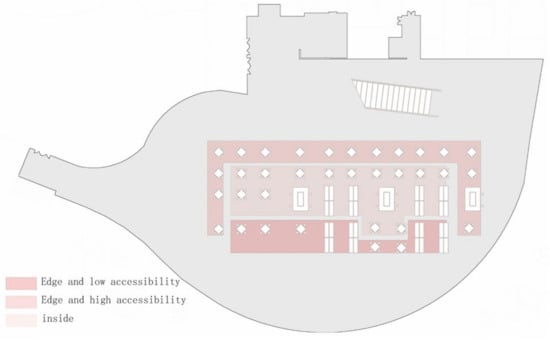

3.2.1. Privacy

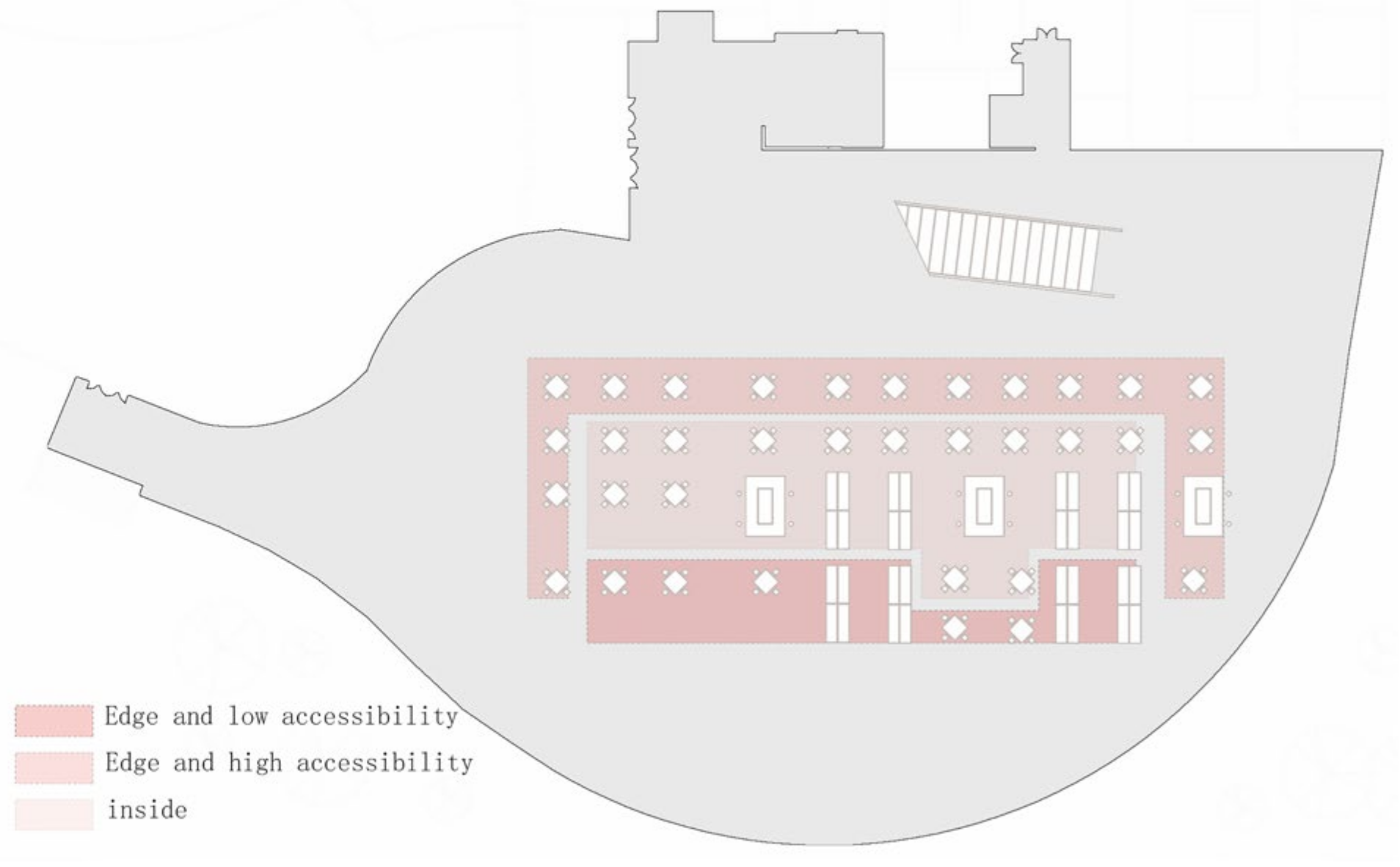

Based on prospect–refuge theory, this study further divided the locations of seats into three levels, namely “edge with low accessibility”, “edge with high accessibility”, and “inside” to evaluate people’s seat preferences based on the psychological factors of privacy (Figure 5). The correlation between location level and user satisfaction was significant (p < 0.05), indicating that privacy factors affected people’s seat selection behavior. In addition, the location level and length of stay were significantly correlated (p < 0.01), indicating that the more private the seat location, the longer the user remained in the seat.

Figure 5.

Diagram of privacy partition.

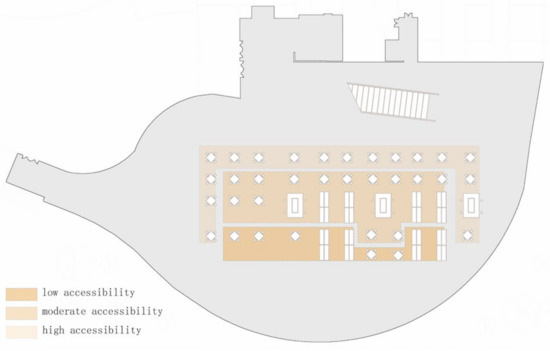

3.2.2. Accessibility to Circulation

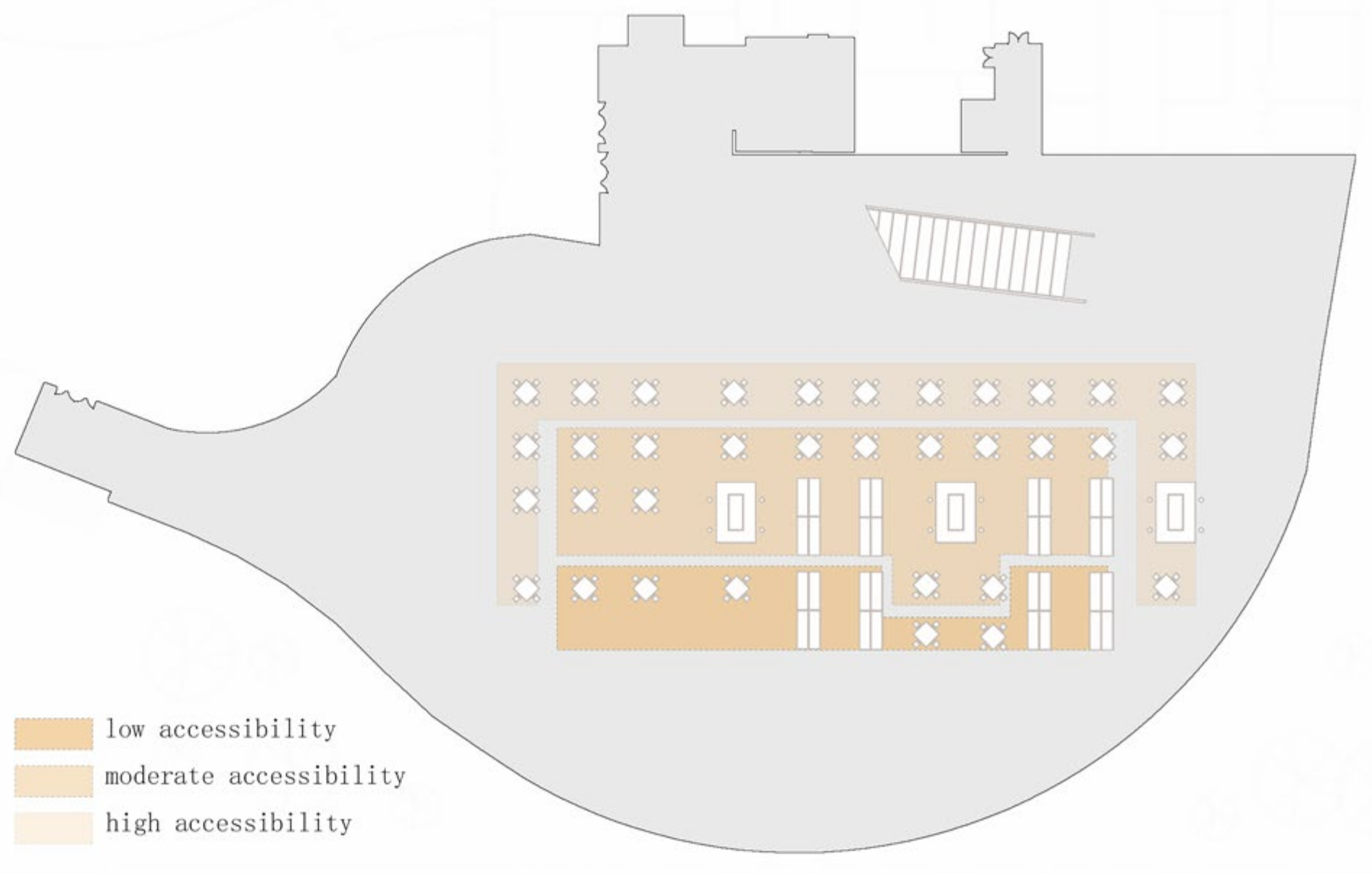

The study measured the accessibility of seats in the venue in three categories: “low accessibility”, “medium accessibility”, and “high accessibility” (Figure 6). The results showed that there was no significant correlation between accessibility satisfaction (p = 0.575) and people’s seating behavior (length of stay) (p = 0.683). This indicated that of several possible privacy factors, a sense of territory and boundaries have a greater impact on users when selecting seats.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of accessibility zoning.

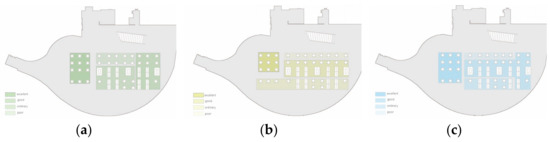

3.2.3. An Open View of the Surrounding Landscape

The site is open on three sides, and the view from each seat is very good. The respondents evaluated the site landscape using the Likert scale in three dimensions: green landscape, artificial landscape, and sky landscape. Satisfaction statistics were used to evaluate the partition of the landscape. The mode, median, inter-quartile rank, and frequency of “very satisfied” [30,31] were used to evaluate the satisfaction of the view in this study. These values were ranked in order of priority from highest to lowest.

According to the satisfaction values of the green landscape (Table 4), the median value was the same and the mode of Partition 1 was “7” (very satisfied), which was higher than other partitions. The inter-quartile rank indicated that the green landscape evaluation of Partition 4 scored lower than other partitions on the 25% level, evaluated as the worst landscape area. When comparing the percentage of “very satisfied”, it can be concluded that the percentage of Partition 2 is higher than Partition 3. The values of man-made landscape (Table 5) and sky landscape statistics (Table 6) can be evaluated in the same way.

Table 4.

Greening landscape data statistics.

Table 5.

Artificial landscape data statistics.

Table 6.

Sky landscape data statistics.

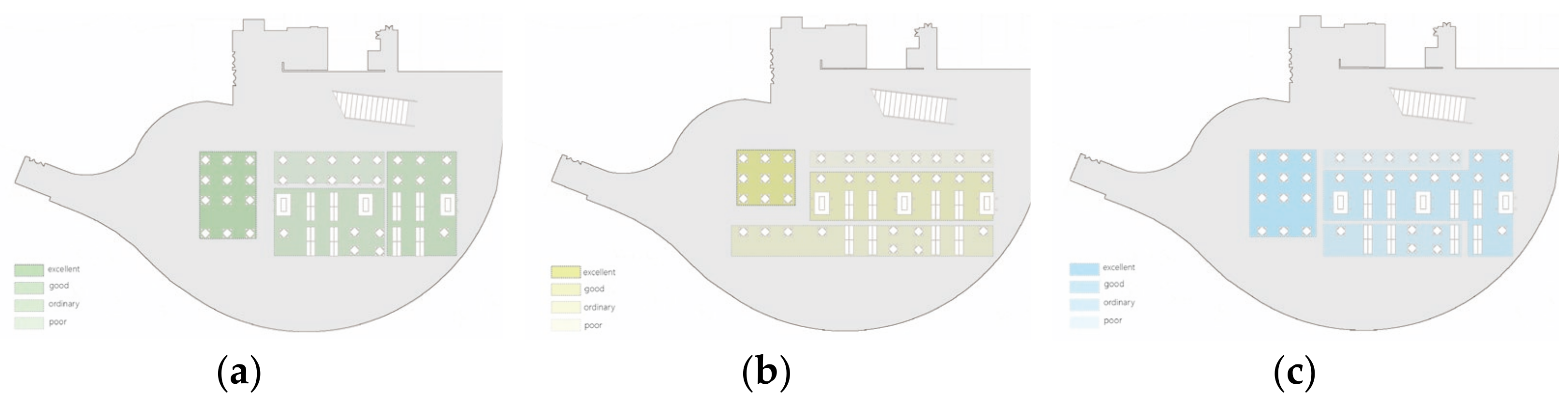

The study used the above methods to divide the area into four satisfaction levels to evaluate the views “excellent”, “good”, “ordinary”, and “poor”. A correlation analysis was conducted between the four view zones and the length of stay. The correlation analysis (Figure 7) revealed that among the three view elements, views of the sky and greenery are significantly correlated with the length of stay (p < 0.01), while an artificial view was not significantly correlated with the length of stay. It can be concluded that a better sky view and greenery view will encourage users to stay longer at the site.

Figure 7.

Diagram of seating partitions: (a) schematic diagram of green view zoning; (b) schematic diagram of man-made view zoning; and (c) schematic diagram of sky view zoning.

3.3. Analysis of Seating Facilities

The activities of users in semi-outdoor spaces are diverse, and spaces for sitting and relaxing should not only be composed of the seats themselves, but there should also be auxiliary facilities to serve the needs of all users of the site. To provide a comfortable and convenient learning and leisure environment for teachers and students, the semi-outdoor space of the ERC is set up with various site facilities in the following two main categories: ancillary facilities, such as bathrooms and catering, and furniture and equipment, such as tables, chairs, and fans.

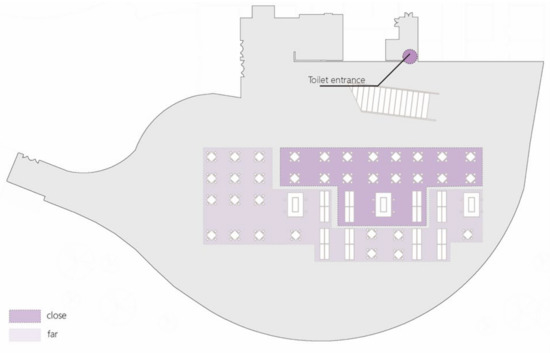

3.3.1. Ancillary Facilities

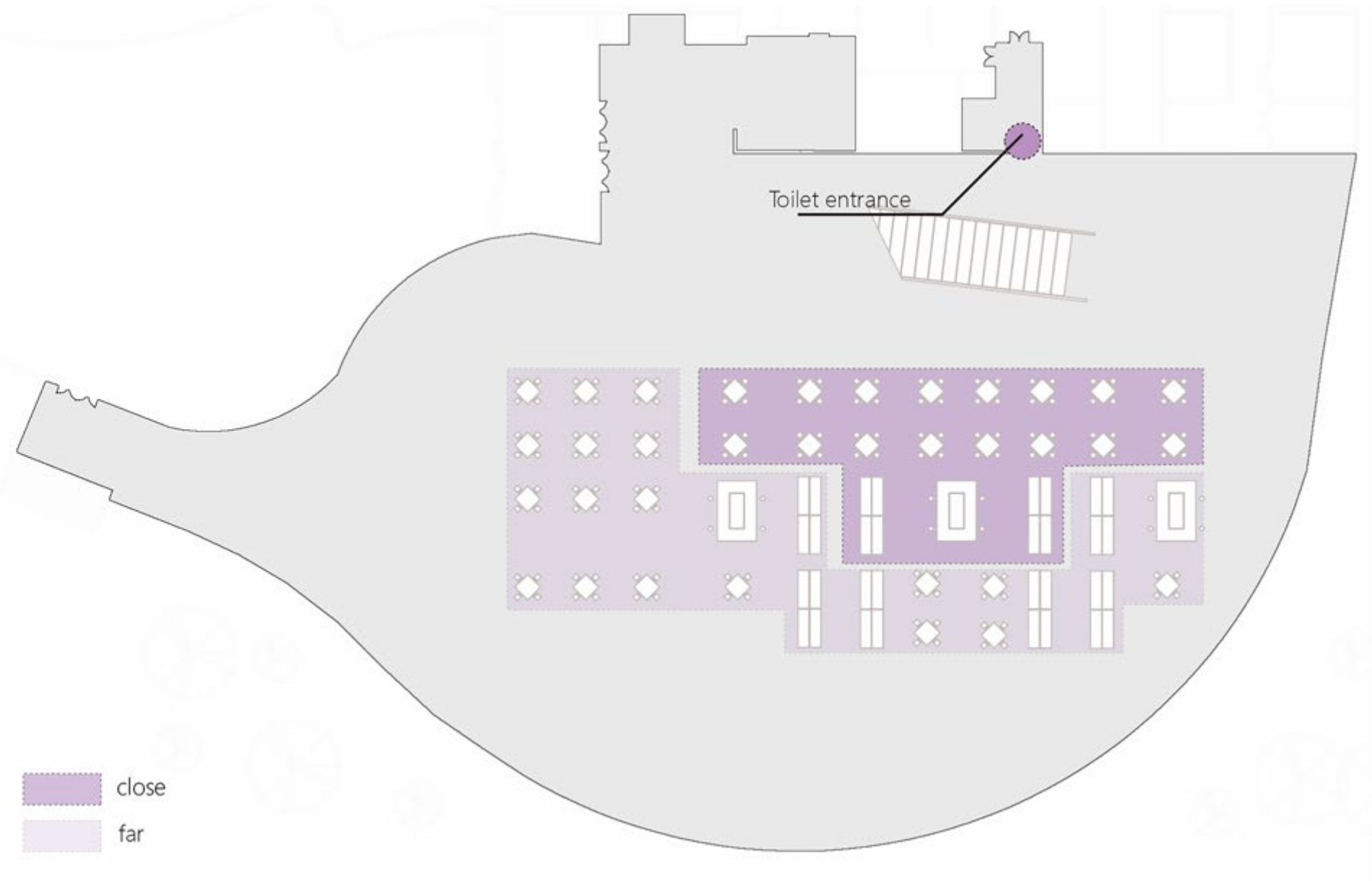

Bathroom: there is a bathroom on the north side of the site. The accessibility of all seats was categorized as “close to the bathroom (less than 20 m)” or “far from the bathroom (more than 20 m)” (Figure 8). A correlation analysis showed that bathroom satisfaction was positively correlated with actual bathroom accessibility (p < 0.05) and bathroom accessibility was positively correlated with the length of stay (p < 0.01). This indicates that bathroom access was an important factor determining the users’ selection of seats.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of bathroom accessibility zoning.

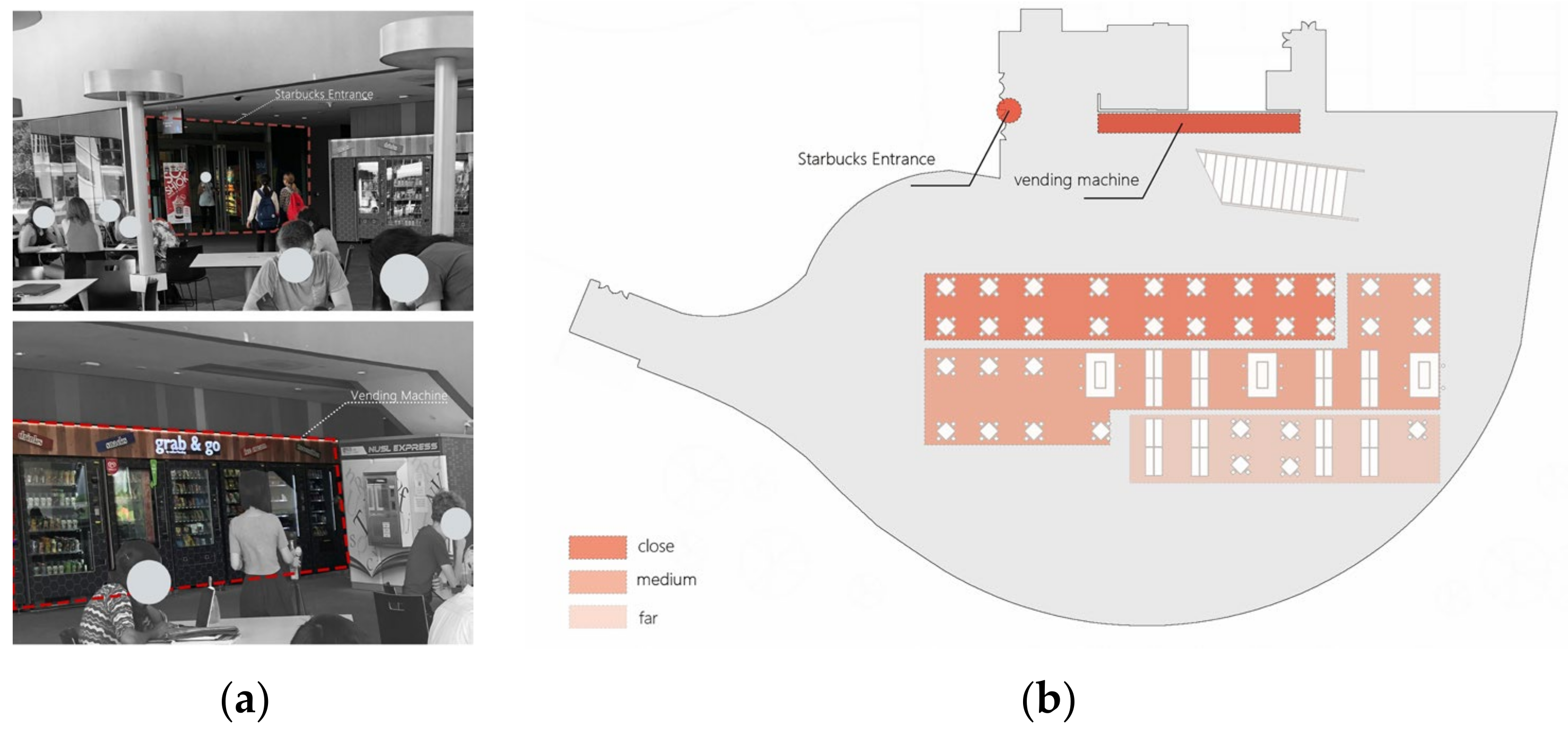

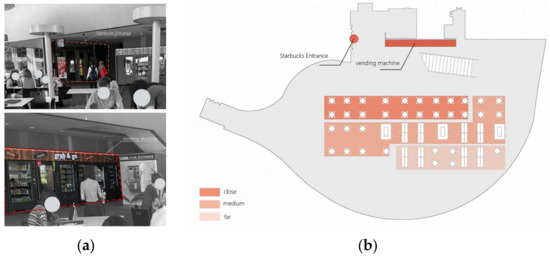

Food supply: The northwest side of the site has a Starbucks and the north side has a vending machine. The accessibility of dining options relative to the seating area was classified as follows: “close to dining area (less than 15 m)”, “medium distance from dining area (15–20 m)”, and “far from dining area (more than 25 m)” (Figure 9). A correlation analysis showed that users’ satisfaction with the accessibility of dining options was not correlated with the actual accessibility of dining facilities (p = 0.669) and was negatively correlated with the time of stay (p < 0.05). This indicates that food supply did not affect people’s choice of seats.

Figure 9.

Food location and seating division: (a) actual view of the food location and (b) schematic diagram of food accessibility zoning.

3.3.2. Furniture and Equipment

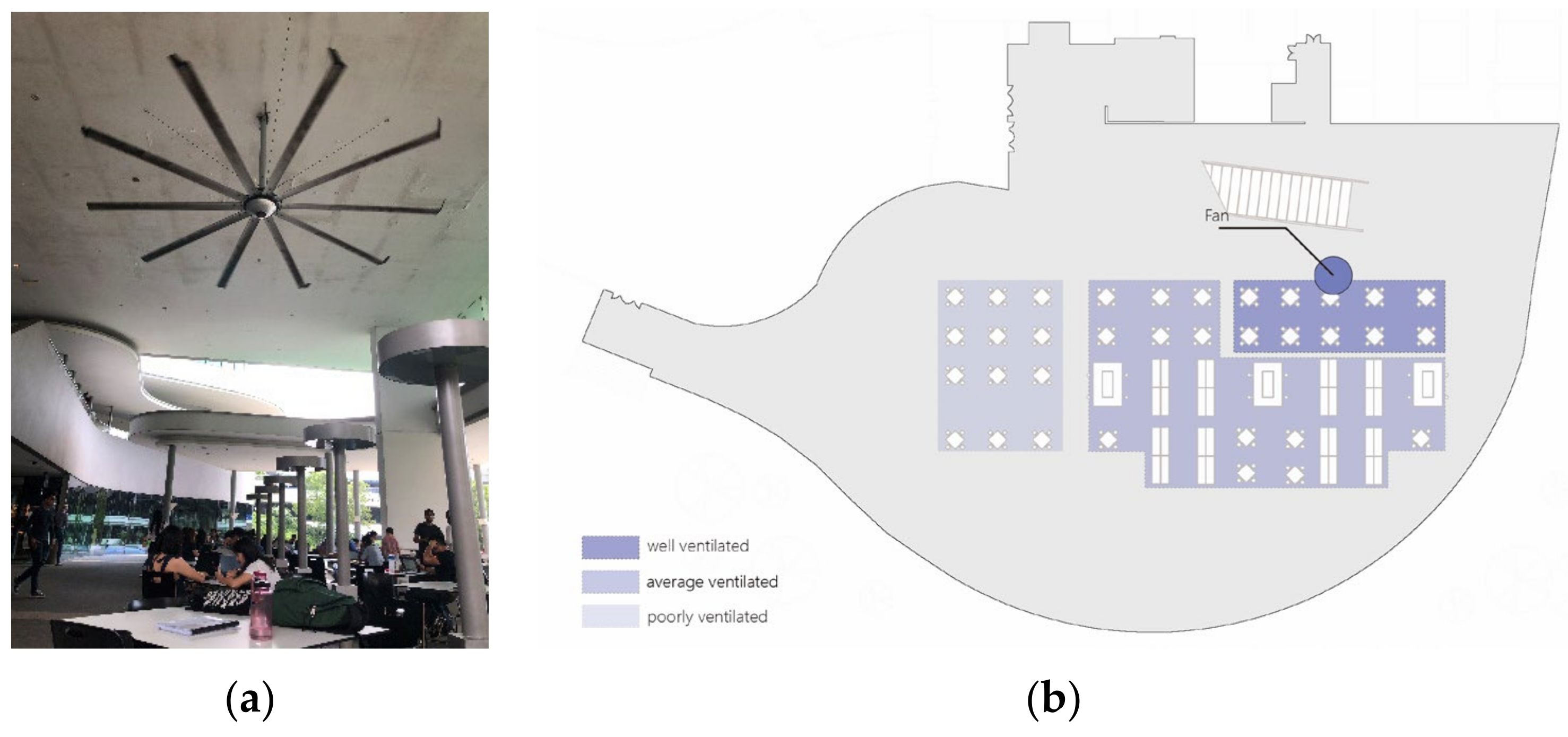

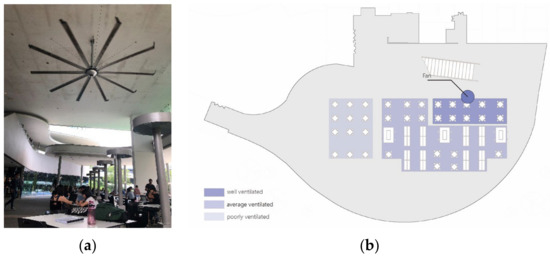

The semi-outdoor space in this study was provided with artificial lighting beside each seat and with power plugs near the table legs; two elements that were evenly distributed. The correlation between satisfaction with artificial lighting and power supply were significantly correlated with the length of stay (p < 0.05). In addition to some user-friendly details, the site has a partial ceiling and a large fan to improve the comfort of the semi-outdoor space (Figure 10). The study classified the location as “well ventilated”, “average ventilated”, and “poorly ventilated“ based on the distance from the fan. The analysis showed that ventilation satisfaction was positively correlated with the fan location (p < 0.01) and time of stay (p < 0.01). This indicates that people were more likely to choose seating and stay in seating near a fan.

Figure 10.

Fan location and seating division: (a) actual view of the fan location and (b) fan effect distribution diagram.

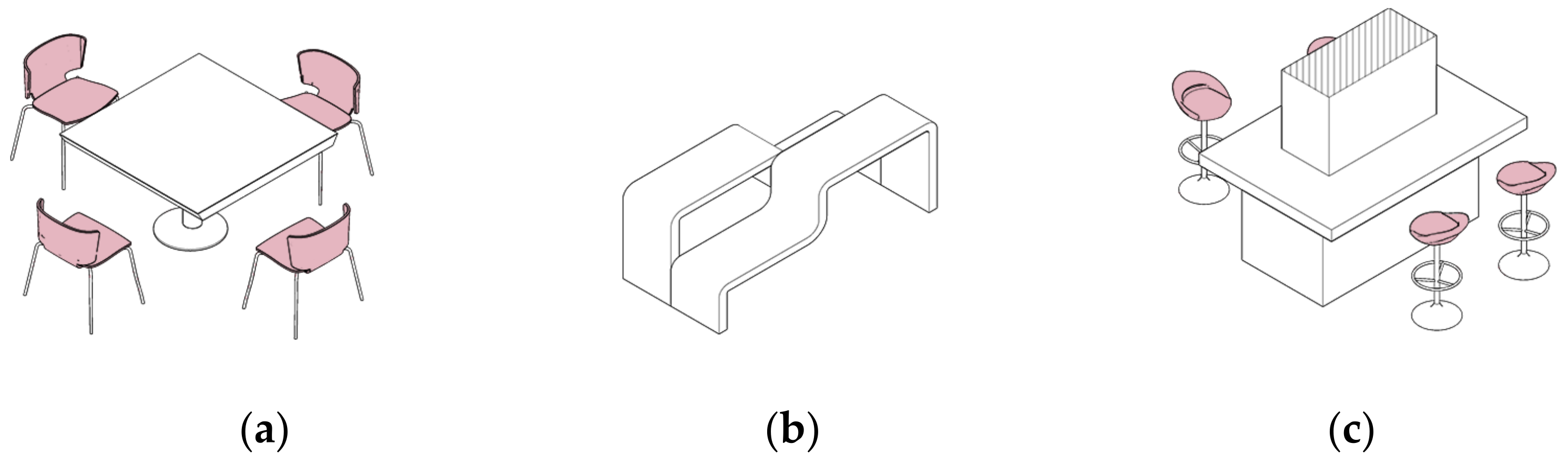

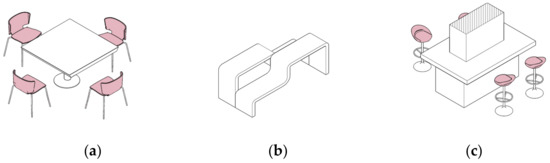

The site has three types of seats (Figure 11). The first type is more suitable for multi-person communication, and this type of seat is the most common in the site. The second form of seating is a combination of two identical curved chairs. This kind of seat generally accommodates two people, sitting in pairs, so that they do not interfere with each other; it is suitable for single people to study and rest. The third form is a seat set up around a pillar, making use of the pillars on the floor. With a high tabletop, users tend to stand around the table for reading and talking. The analysis concluded that users’ satisfaction with the furniture was correlated with the type of seats (p < 0.01). However, the type of seating was not correlated with the length of stay (p = 0.246). Interestingly, type 2 seats were particularly popular with users because they performed the function of both a table and a chair.

Figure 11.

Three types of seat axonometric drawings: (a) square table; (b) two curved tables and chairs; and (c) table and chairs formed around a column.

4. Discussion

4.1. Thermal Environment and Sitting Behavior

Users of an environment care about thermal comfort; a better thermal comfort can always attract more people. However, seat preference was rarely influenced by thermal comfort in this study, as there was little difference in thermal comfort within the same semi-outdoor space. Vegetation may substantially contribute to human thermal comfort [32]; thus, the ground floor of the ERC has a high ratio of green area nearby. In addition, the students preferred well-designed, naturally ventilated classrooms to air-conditioned classrooms [33]. The three-sided open space and variable height of the semi-outdoor space in this study created a better thermal environment that can help increase the productivity of students. The preference of occupants living in a hot and humid region for lower temperatures was proven in this study [34]. The authors believe a landscape water system could be also installed in this semi-outdoor space to accelerate the ventilation and cooling effect and increase the humidity of the air.

4.2. Users Tend to Choose a Sheltered Location on the Edge and Are More Satisfied with Seats with Views of the Natural Landscape

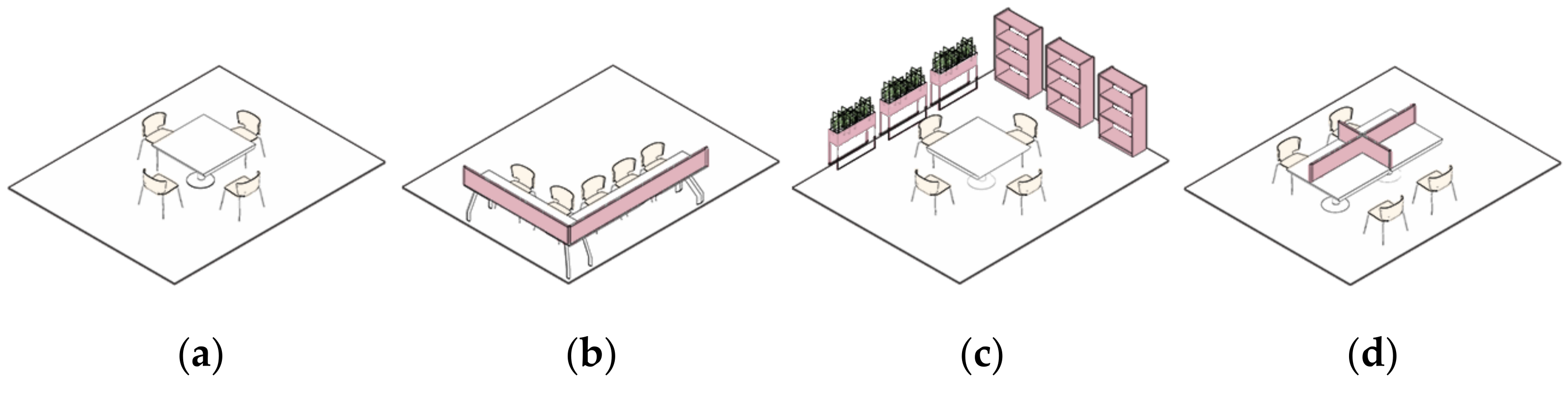

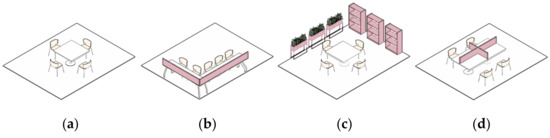

Among the spatial perception elements, privacy was the main consideration for users. This study demonstrates the adaptability of prospect–refuge theory to semi-outdoor spaces, as users tended to stay on the edge of the seating area, without an excessive flow of people. Such locations can ensure a sense of territory for each person, and such quiet spaces also make it easy to observe the surrounding environment. Therefore, seating design should avoid interference with the flow of people (Figure 12). An “L”- or “U”-shaped seat form is a good way to form a semi-private space at the edge for internal members to communicate. Potted plants, bookshelves, and other easily movable components could also limit eye contact to ensure better privacy. Interior seats were generally less attractive than those at the edge; the latter not only provide a better view and foster a more relaxed mood, but also improve the learning experience [35], mostly because interior seats are less sheltered and eye contact is more frequent. Interior design and renovation should balance the degree of footfall across seating areas as to improve the occupancy rate of seats in each area. Desktop dividers could also be added to meet users’ need for privacy [36].

Figure 12.

Strategy map to improve privacy: (a) original seats; (b) inward-facing L-shaped seats; (c) greenery to isolate the view; and (d) desktop partitions to isolate the view.

Comfortable (psychological or/and physical) seating areas with attractive scenes (which consist of other people and their activities and/or different kinds of landscapes) are preferred [37]. This study also found that when choosing seats, users were easily attracted by the surrounding greenery or sky view and preferred to sit closer to the natural landscape. Studies have proven that green landscapes have a healing effect and can enhance the learning efficiency of users. When designing semi-outdoor spaces, designers should create more openings to ensure that more seats enjoy a view of the sky as well as the greenery. Meanwhile, some greenery curtain wall planters could be set up inside the semi-outdoor space to enhance the green coverage rate.

4.3. Site Facilities Greatly Affect the Length of Stay

As for the site facilities, the study found that the accessibility of bathrooms, canteens, fans, power supplies, and lighting affected people’s length of stay. Therefore, when designing semi-outdoor spaces, it is necessary to provide such facilities. In addition, accessible and attractive furniture play a critical role in seat selection [38]. This study also found that users preferred a rich range of types of seats. When arranging seats, curved seats with a certain sense of personal space should be designed to not only ensure privacy but also to provide the possibility for internal communication. The users on the elevated floor were mainly students, and their main activities were learning and communication; therefore, it is necessary to design outdoor leisure tables and chairs that meet the physical and psychological needs of college students. Enhancing the pleasure and comfort of seating areas can reduce student tension and stress and increase the effectiveness of their learning and communication [39]. During the field research, some users raised the need for a greater number of seats, so in addition to the type of design, the number of seats should be considered in future designs.

Nowadays, most teachers and students study and work on laptops, so access to a power supply is very important during lengthy periods of study. The ERC provides a power plug under each table, which encourages users to stay for longer. However, some users suggested that they were unable to find a suitable power plug. The design of such details should also consider the diversity of user needs. The use of a fan and artificial lighting to regulate users’ thermal comfort and the lighting environment are essential components in the design of semi-outdoor spaces. Seating facilities can be designed to make up for the environmental effects that cannot be achieved by spatial design to provide the best sitting and resting experience for each seat.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary

This study explored the seating preferences of users of semi-outdoor learning spaces on a tropical university campus. It assessed the relative importance of factors affecting users’ seat selection in detail, and it explored the factors that influence users’ length of stay in such spaces. Focusing on informal learning spaces, the findings of this study extend the theoretical understanding and inform the design of covered seating and resting spaces.

5.2. Limitations

The study has the following limitations. (1) It focused on user assessment during the hot summer period, ignoring other seasons. (2) It explored seat selection in only one semi-outdoor space. Variables not considered in this study, such as the number of floors, may also affect users’ seat selection. While the study discussed various variables, a conjoint analysis, which was used in a previous study to assess architect priorities and preferences [40] could also be used to explore the phenomenon of preference. Therefore, more comparative studies of semi-outdoor spaces are needed to draw a more general conclusion. (3) In examining the physical environment, this study focused on the effects of thermal comfort on seating preferences; it did not consider other physical factors, such as lighting and sound. Future studies should include these important indicators. The measured parameters and the length of stay were used to indicate user seat preferences in this study, while occupancy patterns could also be an excellent index to value seat preference. Different approaches [41] and technologies [42,43] to identify it in a tropical climate are expected to be used in future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.T., S.S.Y.L. and L.Z.; data curation, B.J.; formal analysis, F.Z. and M.X.; funding acquisition, Y.T. and L.Z.; methodology, Y.T. and M.X.; software, F.Z.; supervision, Y.T., S.S.Y.L. and L.Z.; visualization, F.Z. and M.X.; writing—original draft, Y.T., F.Z. and M.X.; writing—review and editing, Y.T. and F.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no 52108018 and no 52008250), the General project of Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Committee (no 20200814153705001 and no 20200809155144), and the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (no ZDSYS20210623101534001).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the support from Center for Human-oriented Environment and Sustainable Design, Shenzhen University. Many thanks to Janet, Ryan Qing, Sean and Sharon for collecting the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acero, J.A.; Ruefenacht, L.A.; Koh, E.J.Y.; Tan, Y.S.; Norford, L.K. Measuring and Comparing Thermal Comfort in Outdoor and Semi-Outdoor Spaces in Tropical Singapore. Urban Clim. 2022, 42, 101122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Allard, B.; Lo, P.; Chiu, D.K.W.; See-To, E.W.K.; Bao, A.Z.R. The Role of the Library Café as a Learning Space: A Comparative Analysis of Three Universities. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 2019, 51, 823–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; He, J.; Tao, Y. A Study on Post-Occupancy Evaluation of Overhead Space in Universities from the Perspective of User Behavior: An Overhead Open Canteen of a University in Shenzhen. Archit. Tech. 2021, 27, 107–109. [Google Scholar]

- Llinares, C.; Castilla, N.; Luis Higuera-Trujillo, J. Do Attention and Memory Tasks Require the Same Lighting? A Study in University Classrooms. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izmir Tunahan, G.; Altamirano, H.; Unwin Teji, J. The Impact of Daylight Availability on Seat Selection. In Proceedings of the 2021 Illuminating Engineering Society (IES) Annual Conference, New York, NY, USA, 9–13 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, R.; Gen, H.; Li, Z.; Hu, Y. Research on Projection Occlusion Analysis and Optimization of Public Seat Layout—Taking Beijing Wangfujing Pedestrian Street as an Example. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 37, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekler, Z.D.; Lei, Y.; Peng, Y.; Miller, C.; Chong, A. A Hybrid Active Learning Framework for Personal Thermal Comfort Models. Build. Environ. 2023, 234, 110148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wei, L.; Huang, L. Research on the Elderly-Friendly Rest Areas in Urban Parks: A Case Study of Xiamen Zhongshan Park. J. Xiamen Univ. Technol. 2017, 25, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, K.; de Dear, R.; Brambilla, A.; Globa, A. Restorative Benefits of Semi-Outdoor Environments at the Workplace: Does the Thermal Realm Matter? Build. Environ. 2022, 222, 109355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, K.; Zhao, Y. Research on the Influence of Landscape Elements on the Thermal Comfort of Building Overhead in Lingnan Region. Urban. Archit. 2023, 20, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Yang, B. Design of Staying Space & Emergence of Public Life—The Study on Jan Gehl’s Theory for Public Space Design (Part 2). Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2012, 28, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, C.C.; Francis, C. People Places. Design Guidelines for Urban Open Space, 2nd ed.; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, R. Seat Preference in Public Squares and Distribution of the Surrounding People: An Examination of the Validity of Using Visual Simulation. In Proceedings of the 7th European Architectural Endoscopy Association Conference; CUMINCAD: Dortmund, Germany, 2006; pp. 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, F. Seat of Design in Open Space from the Perspective of Privacy. Decoration 2011, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, W. Humanistic design of seating environment in urban public space. Art Panorama. 2015, 07, 120–121. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L. Optimization of Canteen Space in University from the Perspective of Environmental Behavior. Urban. Archit. 2019, 16, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Z.; Khoshbakht, M.; Mahdoudi, B. The Impact of Outdoor Views on Students’ Seat Preference in Learning Environments. Buildings 2018, 8, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Yao, Y.; Li, S. Seating Preference in Learning & Working Spaces—Taking Li Wenzheng Library of Tsinghua University as an Example. Landsc. Archit. Acad. J. 2019, 05, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y. Research on public sitting facilities. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X. Study on the design of outdoor sitting facilities. Planner 2001, 01, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, S.K.A. A Review of Psychological and Cultural Effects on Seating Behavior and Their Application to Foodservice Settings. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2002, 5, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waxman, L. The Coffee Shop: Social and Physical Factors Influencing Place Attachment. J. Inter. Des. 2006, 31, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.-L.; Huang, C.-J. A Study on the Forms and User’s Behaviors of the Public Seats in National Taipei University of Technology. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 3, 2288–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpak, E.M.; Düzenli, T.; Mumcu, S. Raising Awareness of Seating Furniture Design in Landscape Architecture Education: Physical, Activity-Use and Meaning Dimensions. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2020, 30, 587–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Gao, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, J. Research on Campus Sitting Space: A Case Study of Nanjing Forestry University. Mod. Urban Res. 2021, 4, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadepalli, S.; Jayasree, T.; Lakshmi Visakha, V.; Chelliah, S. Influence of Ceiling Fan Induced Non-Uniform Thermal Environment on Thermal Comfort and Spatial Adaptation in Living Room Seat Layout. Build. Environ. 2021, 205, 108232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, M.; Gallo, C.; Sayigh, A.A.M. Architecture—Comfort and Energy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; ISBN 978-0-08-056060-1. [Google Scholar]

- Yaglou, C.P.; Minard, D. Control of Heat Casualties at Military Training Centers. AMA Arch. Ind. Health 1957, 16, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Appleton, J. The Experience of Landscape; John Wiley and Sons: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, S. Likert Scales: How to (Ab)Use Them. Med. Educ. 2004, 38, 1217–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalouch, C. A Pedagogical Approach to Integrate Parametric Thinking in Early Design Studios. Int. J. Archit. Res. 2018, 12, 162–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashua-Bar, L.; Pearlmutter, D.; Erell, E. The Influence of Trees and Grass on Outdoor Thermal Comfort in a Hot-Arid Environment. Int. J. Climatol. 2011, 31, 1498–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, S.; Kesavaperumal, T.; Noguchi, M. An Adaptive Thermal Comfort Model for Naturally Ventilated Classrooms of Technical Institutions in Madurai. Open House Int. 2021, 46, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzati, N.; Zaki, S.A.; Rijal, H.B.; Rey, J.A.A.; Hagishima, A.; Atikha, N. Investigation of Thermal Adaptation and Development of an Adaptive Model under Various Cooling Temperature Settings for Students’ Activity Rooms in a University Building in Malaysia. Buildings 2022, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Yuan, W.; Kong, F.; Xue, J. A Study of Library Window Seat Consumption and Learning Efficiency Based on the ABC Attitude Model and the Proposal of a Library Service Optimization Strategy. Buildings 2022, 12, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunahan, G.I.; Altamirano, H. Seating Behaviour of Students before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic: Findings from Occupancy Monitoring with PIR Sensors at the UCL Bartlett Library. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumcu, S.; Duzenli, T.; Özbilen, A. Prospect and Refuge as the Predictors of Preferences for Seating Areas. Sci. Res. Essays 2010, 5, 1223–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Psathiti, C.; Sailer, K. A Prospect-Refuge Approach to Seat Preference: Environmental Psychology and Spatial Layout. In Proceedings of the 11th International Space Syntax Symposium, Lisbon, Portugal, 3–7 July 2017; Volume 11, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Yuan, X.; Zhou, T.; Cai, Q.; Xu, J. Analysis of demand for informal learning space and design of leisure tables and chairs in university. J. Hubei Univ. Econ. 2022, 19, 113–116. [Google Scholar]

- Alalouch, C.; Aspinall, P.; Smith, H. Architects’ Priorities for Hospital-Ward Design Criteria: Application of Choice-Based Conjoint Analysis in Architectural Research. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2015, 32, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Tekler, Z.D.; Low, R.; Gunay, B.; Andersen, R.K.; Blessing, L. A Scalable Bluetooth Low Energy Approach to Identify Occupancy Patterns and Profiles in Office Spaces. Build. Environ. 2020, 171, 106681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekler, Z.D.; Chong, A. Occupancy Prediction Using Deep Learning Approaches across Multiple Space Types: A Minimum Sensing Strategy. Build. Environ. 2022, 226, 109689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Masood, M.K.; Soh, Y.C. A Fusion Framework for Occupancy Estimation in Office Buildings Based on Environmental Sensor Data. Energy Build. 2016, 133, 790–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).