A Study on the Spatial Pattern of Traditional Villages from the Perspective of Courtyard House Distribution

Abstract

:1. Introduction

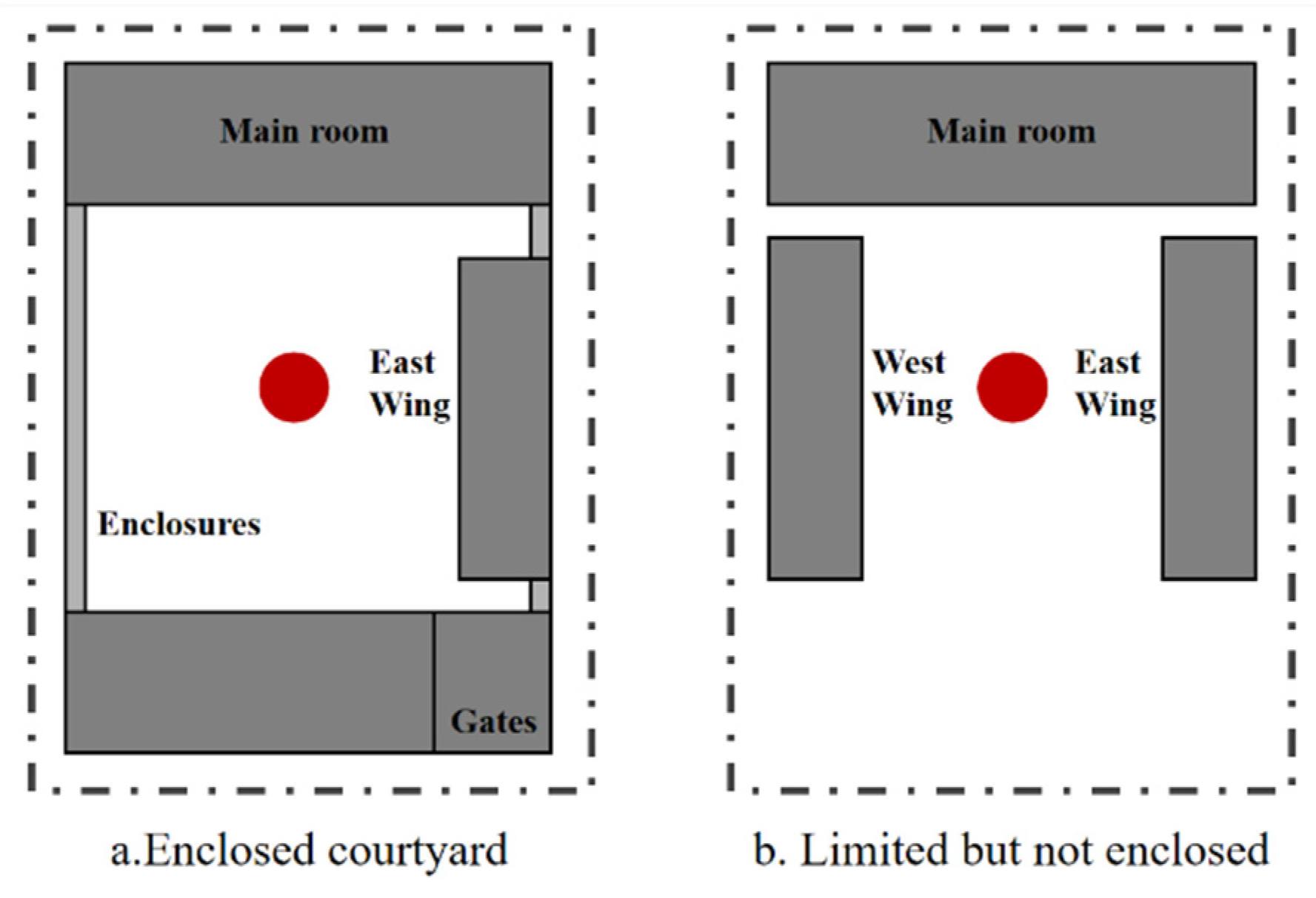

2. Courtyard House: The Smallest Rural Social Unit

2.1. Definition of a Courtyard House

2.2. Courtyard Houses and Rural Order

3. Materials and Methods

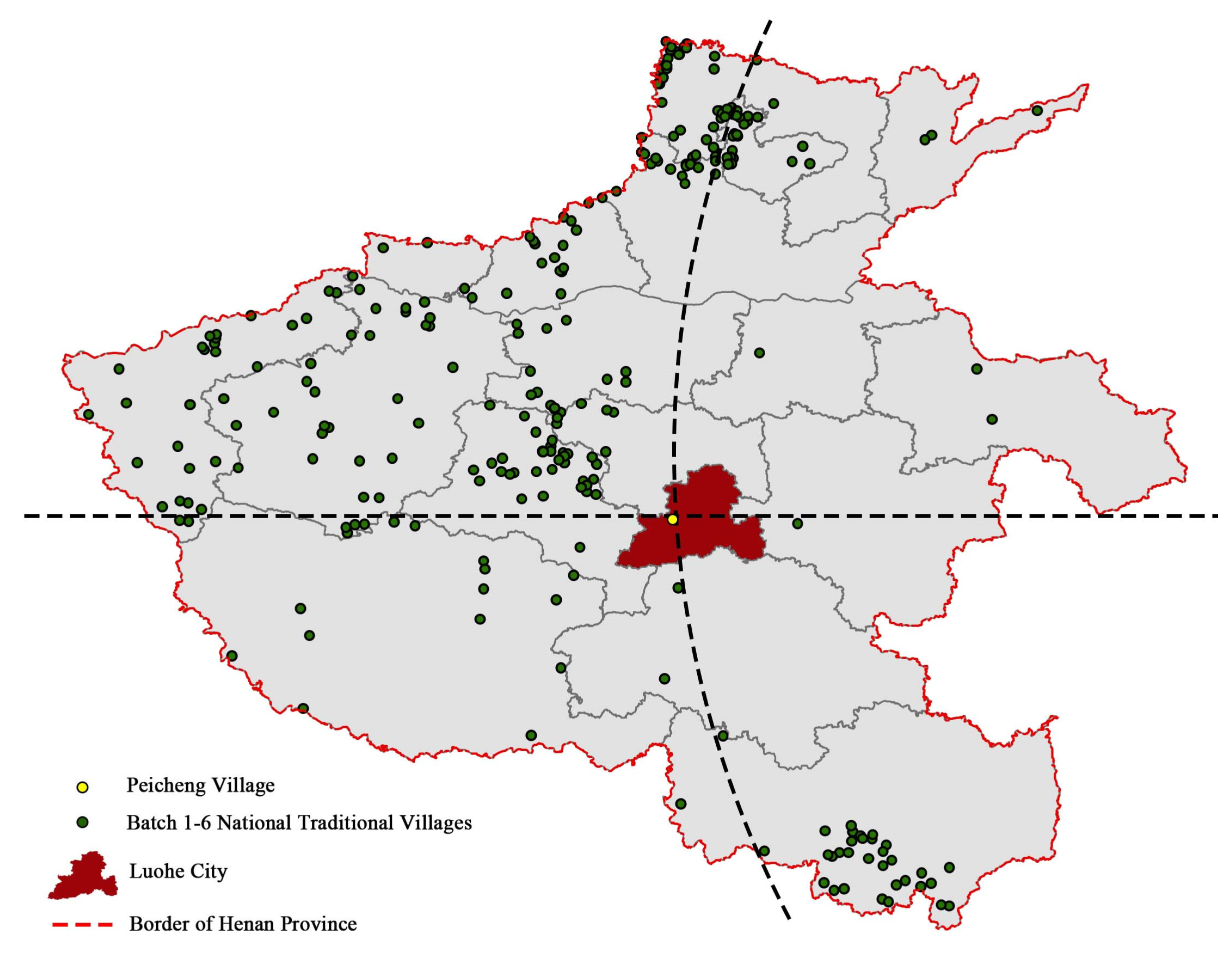

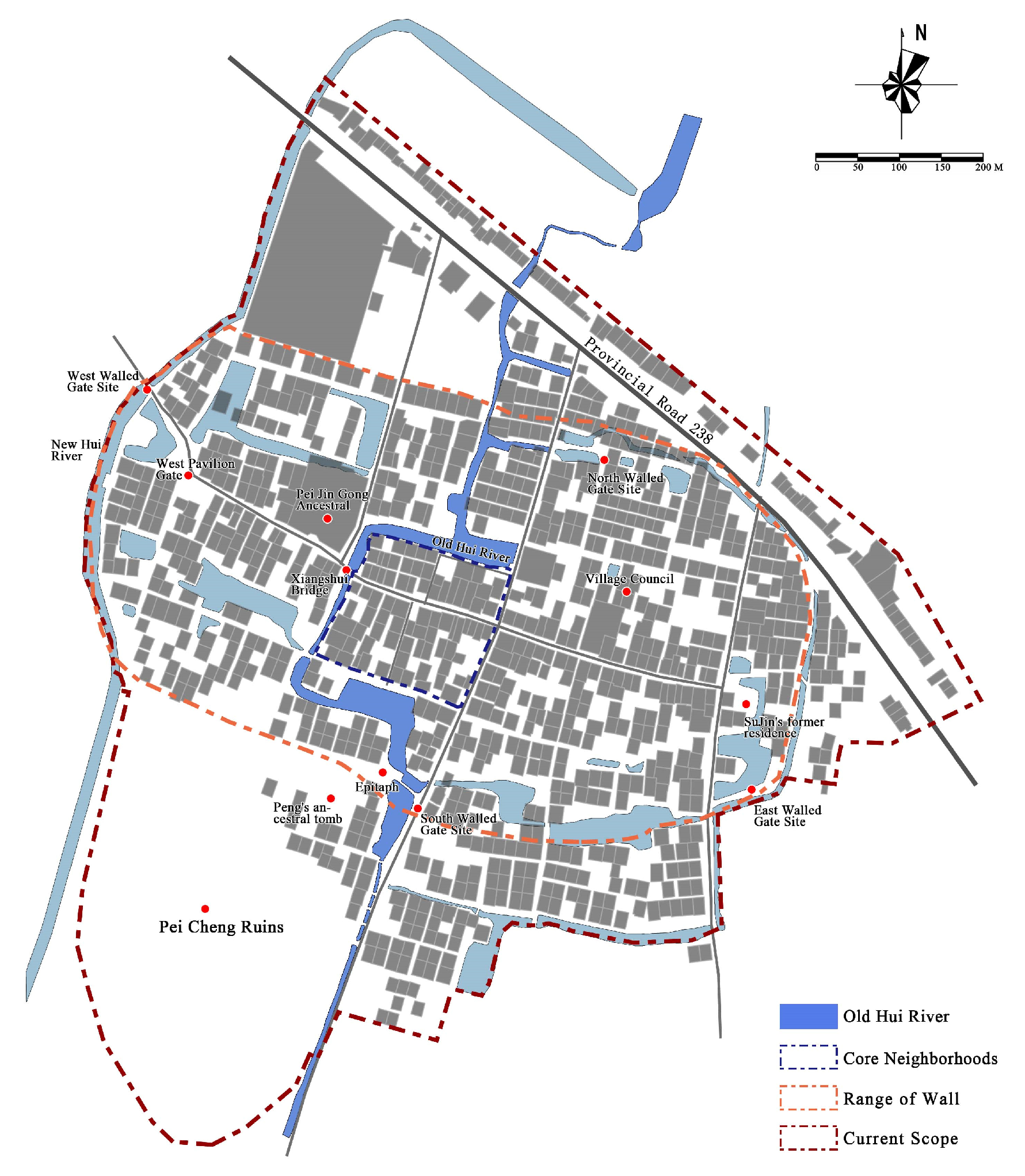

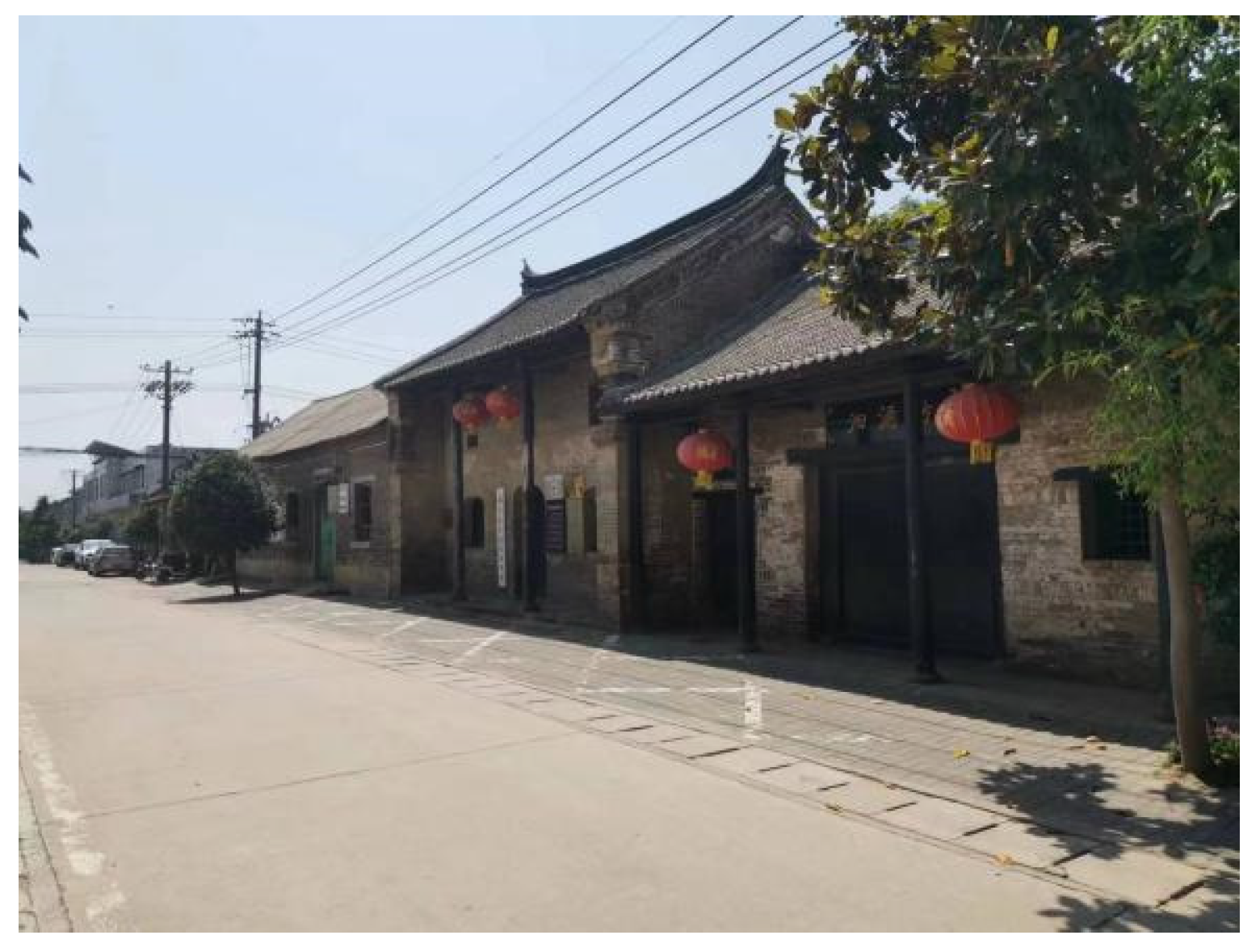

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Research Methods

3.2.1. Research in the Literature and in Ancient Books

3.2.2. Map Analysis

3.2.3. Quantitative Model Assistance Method

Standard Deviation Ellipse Analysis

Kernel Density Analysis

Space Syntax

4. Results

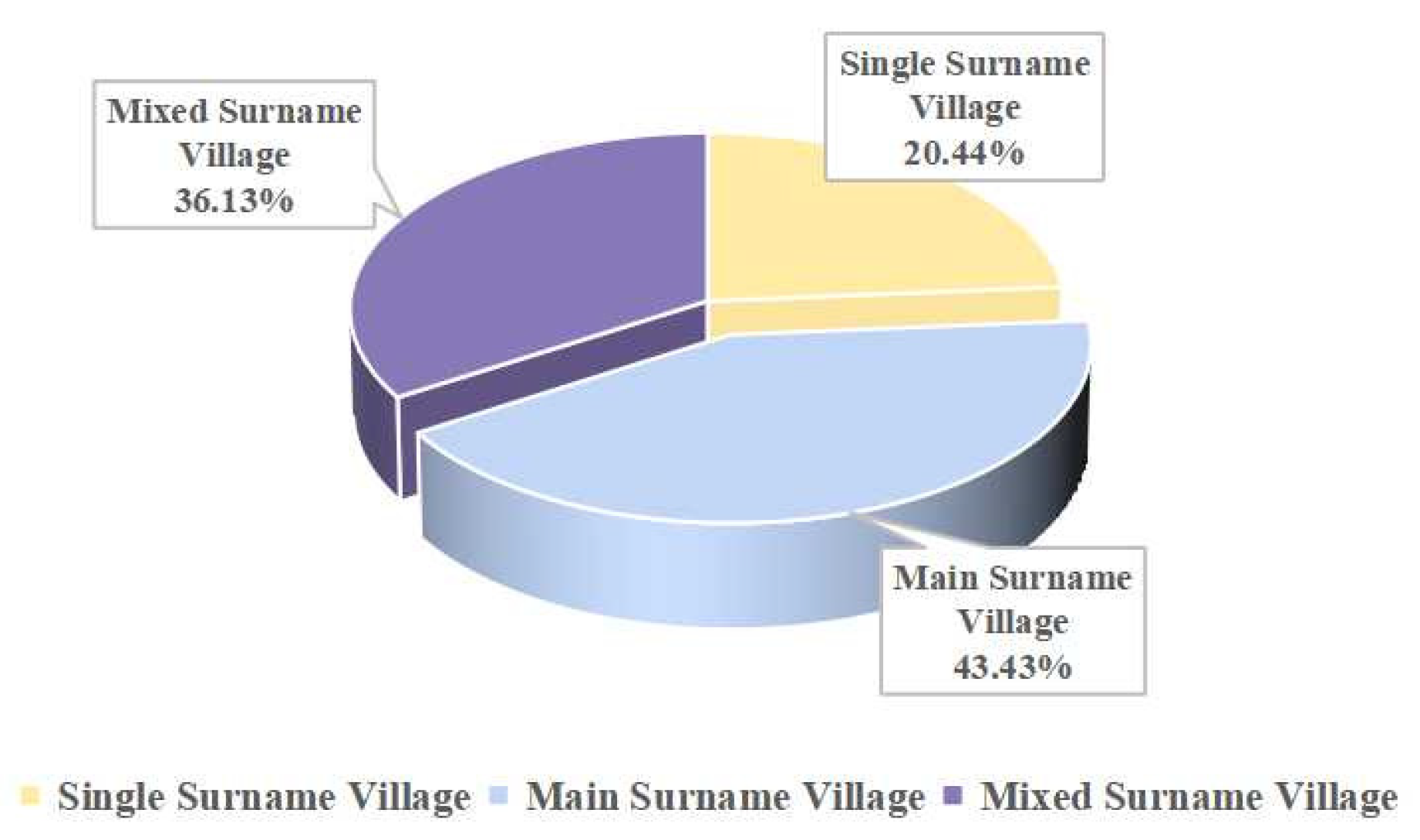

4.1. Characteristics of Clan Courtyard House Patch Aggregation and Differentiation

4.1.1. Overall House “Ring-Axis” Distribution

- (1)

- According to the standard deviation ellipse calculation, there is no obvious directionality in the overall distribution of courtyard houses in Pei Cheng Village, and thus, it is more evenly distributed in all directions, with Cross Street as the centre. The elliptical long axis is 328.051 m in length, and the short axis is 281.223 m in length, with an oblateness of 0.142. The difference between the long and short axes is not significant, and the shape is nearly circular, with the long axis being relatively long and coinciding with the east–west main street, originating from the historic period when the wall was built in an elliptical shape, like the back of a tortoise, and slightly longer in the east–west direction than in the north–south direction. The centre of the ellipse derived from the quantitative analysis overlaps highly with Cross Street centre, indicating that the overall village courtyard houses are distributed in all directions, with Cross Street as the centre.

- (2)

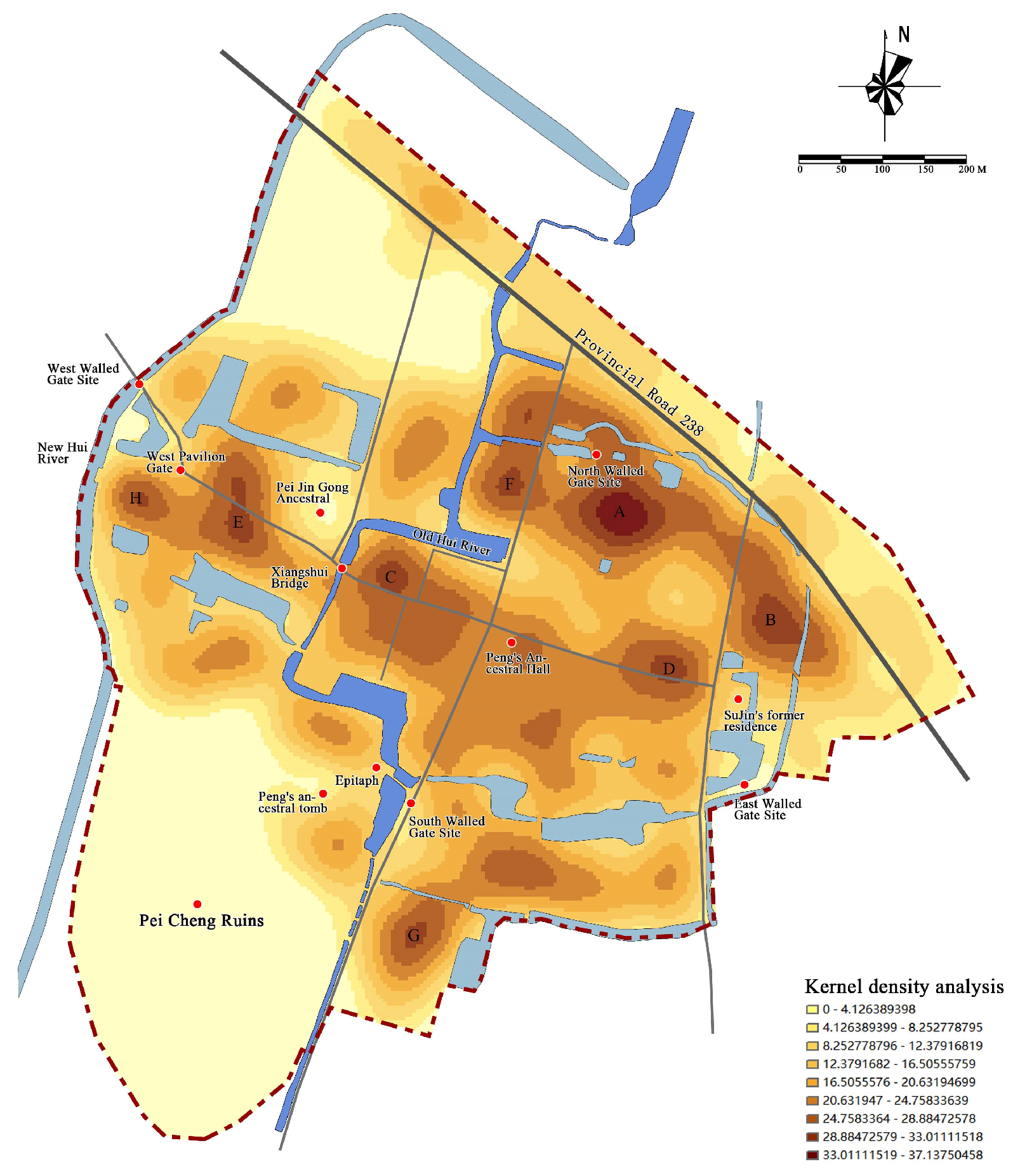

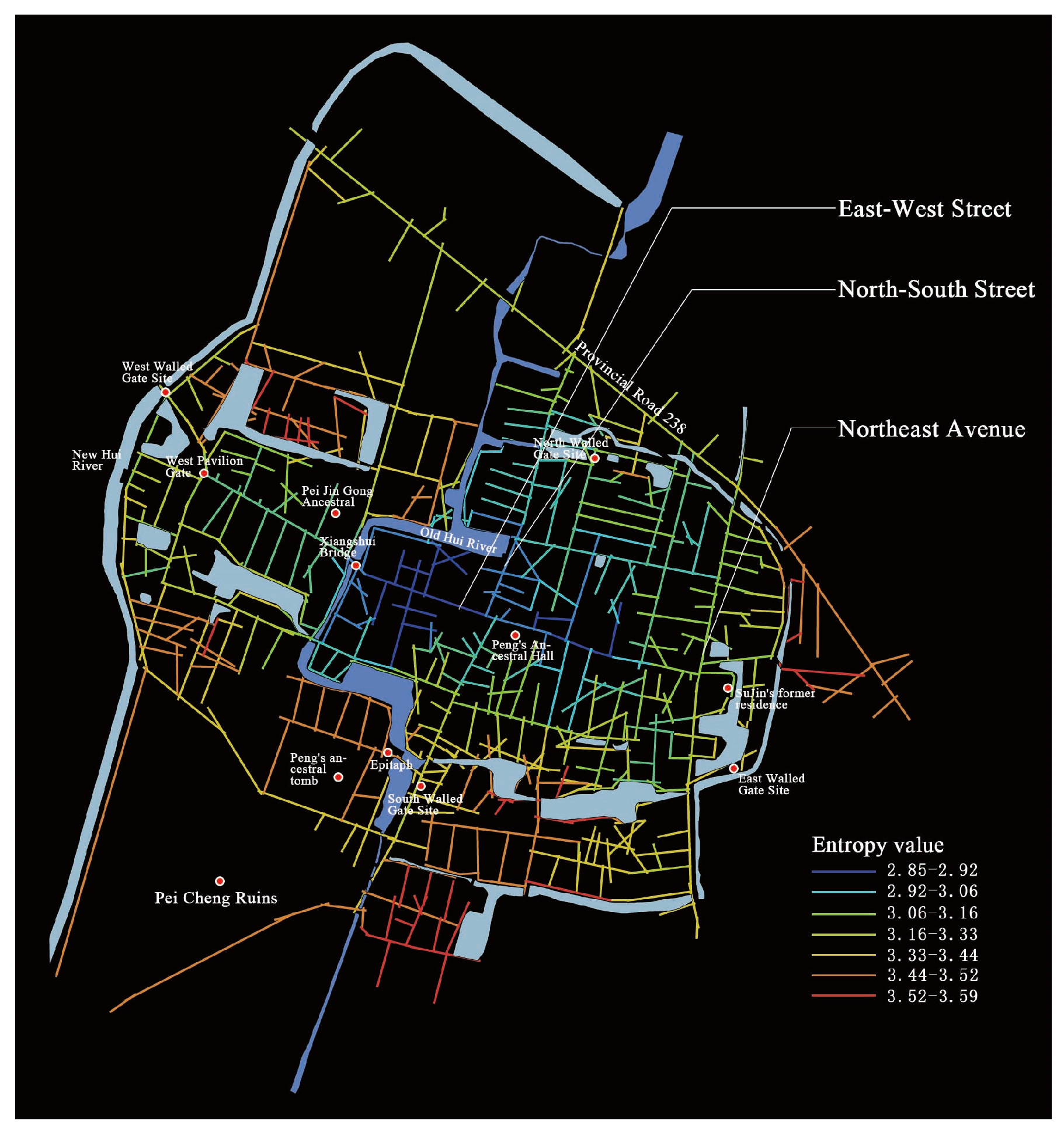

- According to the kernel density analysis results, the whole cluster of rural courtyard houses shows a pattern of “a ring and an axis, bounded by water”. As for the ring and the axis, the areas of high aggregation are concentrated on the inner side of the original ring trench in the north of the village, forming a circular distribution feature along the wall of the fortress, and at the same time, forming a high-aggregation axis for the distribution of village courtyard houses along east–west Street. The river is the boundary: the Old Hui River is the density-dividing line between the courtyard house patches, with a low density of courtyard houses on the west side of the river and a high density of courtyard houses on the east side. In the old days, due to the constraints of the river barrier, there was only one bridge connecting the two sides of the river at the intersection of east–west Street and the Old Hui River, and a large area of wetland to the southwest of the village was not suitable for construction, so the distribution of courtyard houses on the west side of the village is still sparse and scattered.

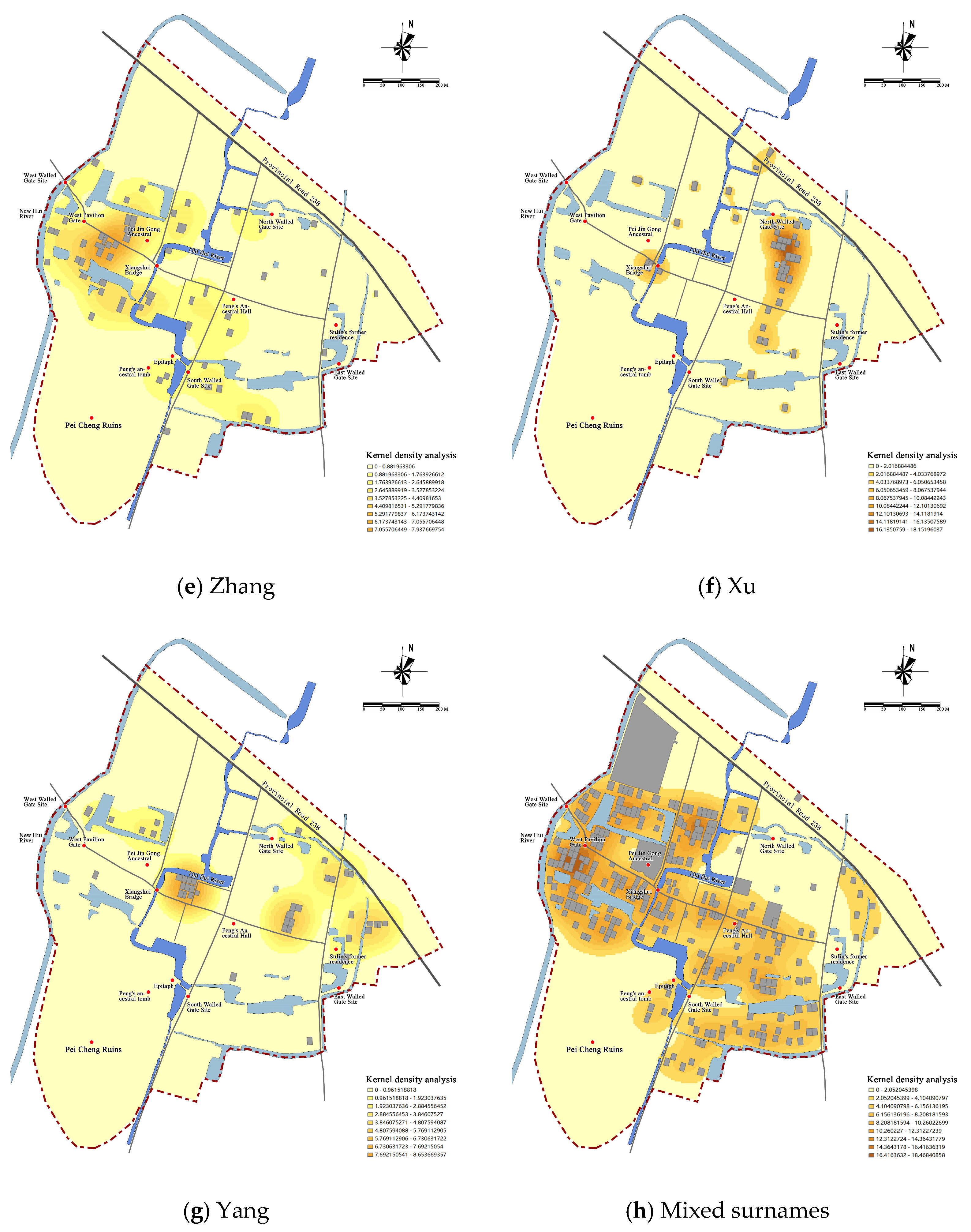

4.1.2. Clan House Aggregation and Differentiation

- (1)

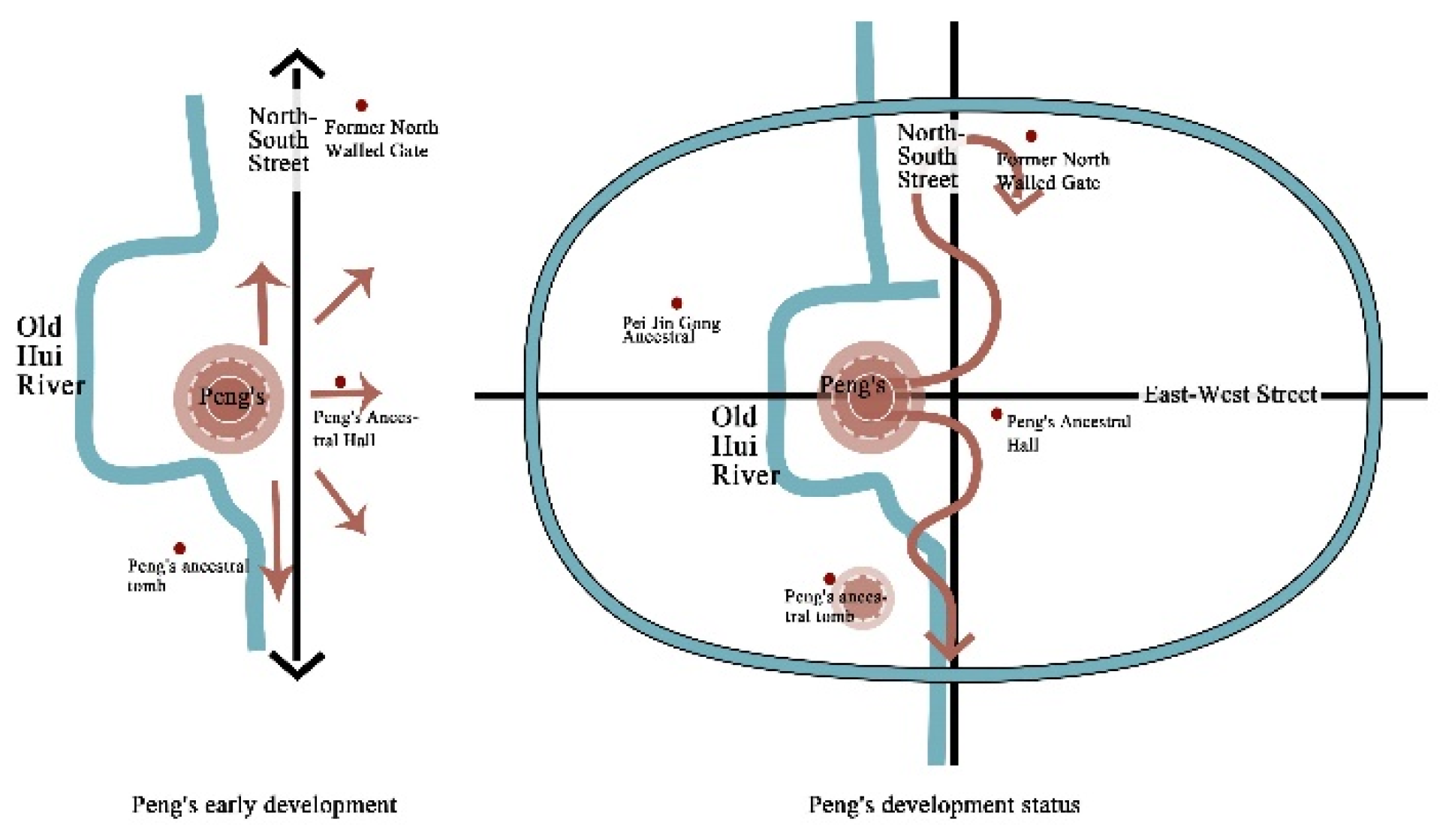

- Main surname—The Peng clan courtyard houses are distributed in a continuous axis, dominating the main spatial structure of the rural village.

- (a)

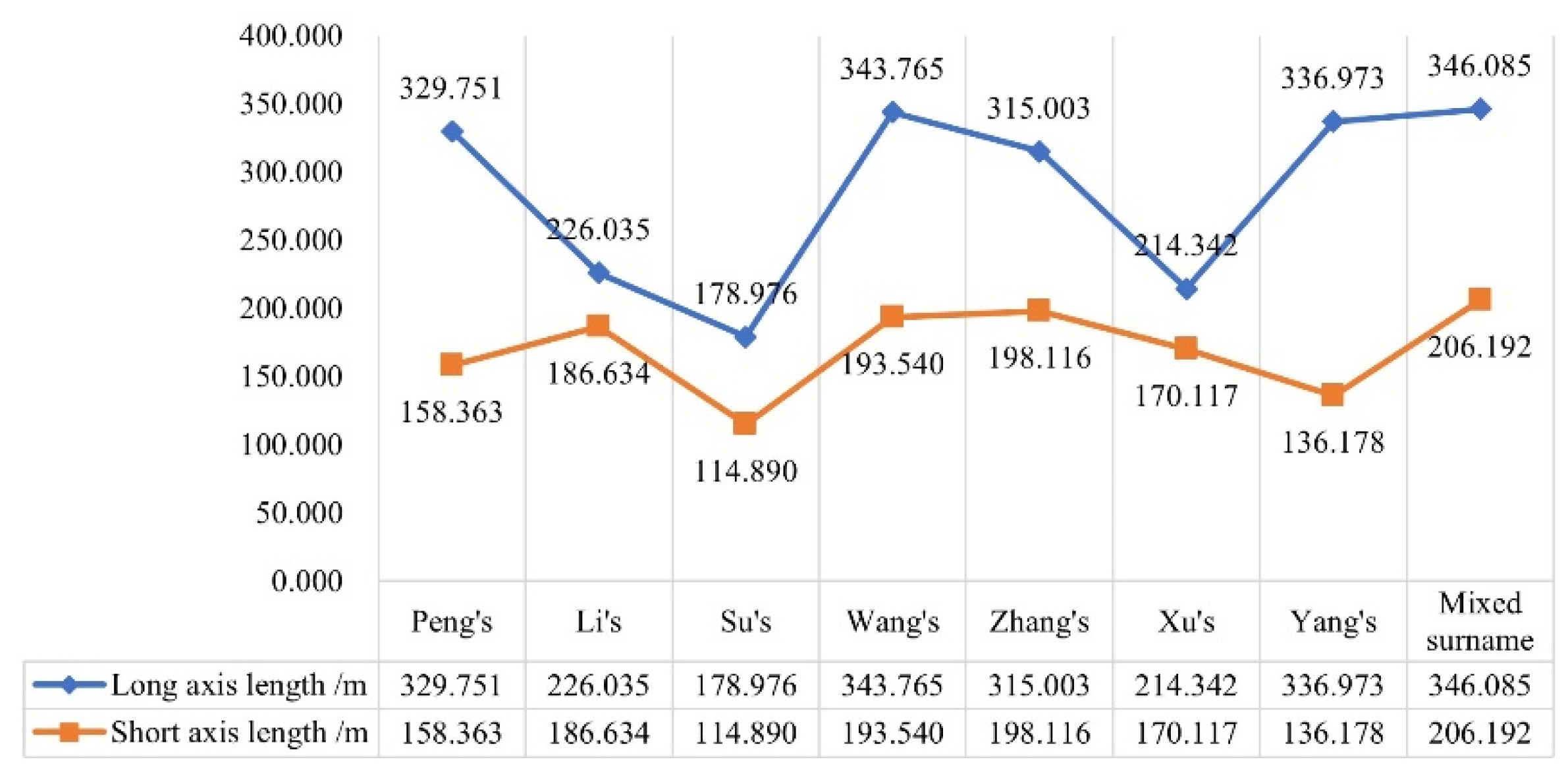

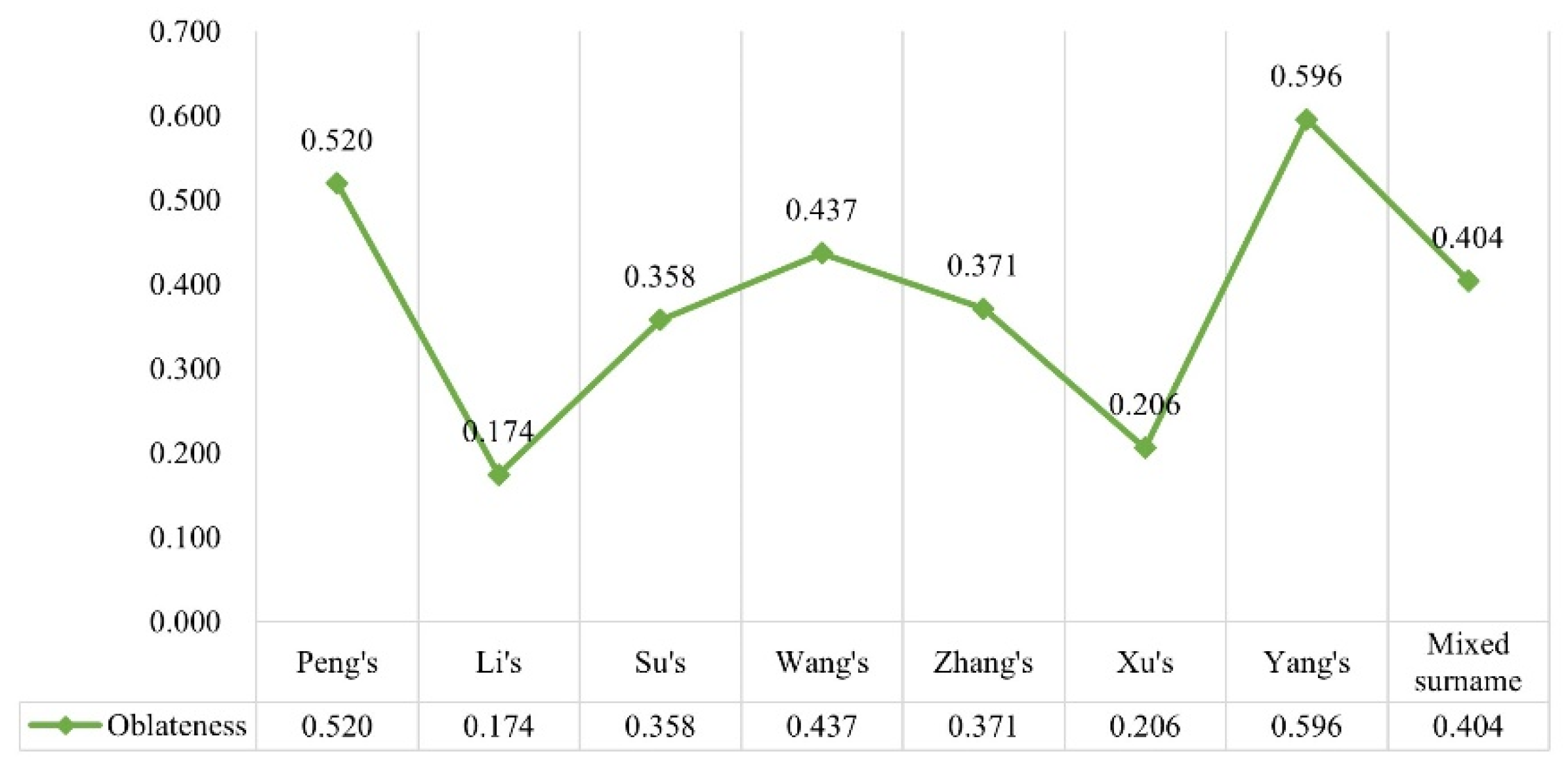

- The results of the standard deviation ellipse calculation are as follows: the Peng family courtyard house is axially oriented through the north and south of the village, with strong centrality. The standard deviation elliptical oblateness of the distribution of the patches of the Peng family’s courtyard house is 0.520, ranking second in the data (as shown in Figure 21). The oblateness is larger, indicating that the distribution of courtyard houses has significant directionality, and the long axis of the ellipse almost coincides with north–south Street, indicating that the distribution direction of its courtyard houses is a south–north distribution. The short semiaxis of the ellipse indicates the distribution range and centripetal tendency of the courtyard houses, and the length of the short axis of Peng’s standard deviation ellipse is 158.363 m (as shown in Figure 20), which is second in the village family data. The centre of the ellipse basically falls in the centre of the village across the street and near the Peng ancestral hall (Figure 18a), showing that the Peng family occupies the centre of the village and takes the village centre, and that the Peng ancestral hall serves as the interclan core for distribution and presents a strong centripetal tendency.

- (b)

- From the results of the kernel density analysis, the Peng family courtyard houses have an “east of the river distribution, and are highly aggregated”. On the one hand, the vast majority of the Peng family courtyard houses are distributed on the east side of the Old Hui River, and only a small part of the south of the village crosses the Old Hui River and is distributed around the Peng family’s ancestral tomb. On the other hand, the Peng courtyard houses run north and south through the village and form several clusters in the area near the former North Walled Gate at the north end of North–South Street and at the Peng ancestral graves at the south end. After liberation, the Peng clan moved out of the core neighbourhood area where they lived at the beginning of the settlement, and the Peng courtyard houses in the core neighbourhood have been replaced by mixed surname-associated courtyard houses one after another. Only the scattered presence of Peng clansmen remains in the core neighbourhood, and this is the reason why the distribution of Peng courtyard houses is physically centred at the Cross Street intersection, but no high aggregation point is formed here (Figure 22 and Figure 23). Moreover, the kernel density maximum value of the Peng family is the highest within the village (26.34), and thus, it is higher than the kernel density maximum value of other family courtyard house distributions, forming a high-density area on the north side of the village. The high maximum value indicates that the courtyard house distribution is more clustered and distributed relatively closer under the control of a strong clan bloodline (Figure 22).

| Main Surname—Peng | ||

|---|---|---|

| Standard deviation ellipse | Spatial distribution centre | The elliptical centre is close to the village centre (the centre of Cross Street) and the family ancestral hall, and the physical centre coincides with the spiritual centre of the family. |

| Directional trends | High values of oblateness (0.52), obvious directionality, and a south–north distribution. | |

| Degree of centripetal tendency | Short axis length (158.363 m), strong degree of centripetal tendency. | |

| Kernel density | Degree of aggregation | East of the river distribution, highly aggregated. |

- (2)

- Secondary surname—The distribution of the courtyard houses of the Li and Su families is in a staggered pattern, strengthening the main nodes in rural areas.

- (a)

- The results of the standard deviation ellipse calculation are as follows: the overall directionality and centripetal tendency of the distribution of the Li courtyard houses is not strong, while the overall directionality of the distribution of the Su courtyard houses is significant, and the centripetal tendency is strong. The standard deviation ellipse oblateness for the Li houses is 0.174, with a small oblateness (as shown in Figure 21). According to the standard deviation ellipse measurement and the distribution of courtyard houses, it can be seen that the overall distribution direction of the Li courtyard houses is not strong but more distributed along both sides of Northeast Avenue. The Su standard deviation ellipse oblateness is 0.358, the oblateness is relatively large (as shown in Figure 21), and the long axis of the ellipse overlaps with Northeast Avenue, showing a south–north distribution. The values of the short axis for the Li and Su houses are 186.634 m and 114.890 m, respectively. The short semiaxis for the Li houses is longer, and the short semiaxis for the Su houses is the shortest among several major clans in the village, indicating that the centripetal tendency of the Li family is not obvious, and that the Su family has a strong centripetal tendency. The physical centre of the Su standard deviation ellipse falls near Su Jin’s former residence, and the strong centripetal tendency associated with the Su family stems from the fact that there is a building with the spirit of the Su family. Although the Li family has grown, there are no obvious Li family spiritual ritual structures in the village, leading to a small number of Li courtyard houses scattered in the village away from the high aggregation point of the Li family. After liberation, the two families tended to extend outwards; in one direction, the expansion was through the wall of the fortress to the east, and in the other direction, the expansion was laid out along provincial road 238.

- (b)

- From the degree of aggregation, it can be observed that the Li and Su families are clustered in a point-like pattern, with staggered distribution. Although the overall distribution of the Li courtyard houses lacks a strong centripetal tendency, there are obvious gathering areas, and both the Li and Su families are distributed in the village east end near Northeast Avenue on both sides, with a scattered distribution aggregation state. The Li family has the highest nuclear density of 23.73, ranking second in the village, with densely distributed residential areas, while the Su family has a lower kernel density maximum value (14.49), with a looser distribution and multiple point-like aggregation areas. Since the Su and Li families moved into the village, their intermarriages have continued to intertwine with each other, ultimately forming a trend of interconnected development (Figure 22 and Figure 24).

| Secondary Surnames—Li, Su | ||

|---|---|---|

| Standard deviation ellipse | Spatial distribution centre | The absence of obvious representations of the elliptical centre of the Li family; the Su family elliptical centre is in close proximity to Su Jin’s former residence, and the physical centre coincides with the family’s spiritual centre. |

| Directional trends | The low value of oblateness for the Li family (0.174), with an insignificant directional distribution; the value of oblateness for the Su family is high (0.358), and the direction of distribution is obvious, along both sides of Northeast Avenue. | |

| Degree of centripetal tendency | High value for the Li family’s short axis length (186.634 m), which is not strongly centripetal; low value for the Su family’s short axis length (114.890 m), strong degree of centripetal tendency. | |

| Kernel density | Degree of aggregation | Li and Su point aggregation, interwoven distribution. |

- (3)

- The distribution of courtyard houses belonging to other secondary surname clans is characterized by scattered clusters and flexibility.

| Other Secondary Surnames—Wang, Zhang, Xu, Yang, etc. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Standard deviation ellipse | Spatial distribution centre | No apparent representation of the elliptical centre. |

| Directional trends | The oblateness values (0.206–0.596), distribution direction is obvious. | |

| Degree of centripetal tendency | Short axis length (136.178–198.116 m), not strongly centripetal. | |

| Kernel density | Degree of aggregation | Flexible location, weak aggregation ability. |

- (4)

- Mixed surname family courtyard house distribution is scattered into pieces.

- (a)

- The calculation results of the standard deviation ellipse: The mixed surname family courtyard houses of are distributed in the general direction of “southeast–northwest”, but the centripetal nature is poor. The standard deviation elliptical oblateness for the mixed family names is 0.404, and the distribution of courtyard houses shows a certain directionality (as shown in Figure 21), with the two large families of Li and Su occupying the northeast region and the Pei Cheng ruins and wetlands in the southwest region of the village, so they can only compete for the distribution of vacant plots in the village, and finally present a “southeast–northwest” direction distribution. The length of the short axis of the ellipse for families with mixed surnames is 206.192 m, which is the longest of the short axis of the standard deviation ellipse for each surname (as shown in Figure 20), indicating that its centripetal nature is the weakest compared to that of other families with stronger clan power because families with mixed surnames have chosen to build on some of the remaining flat and liveable plots within the village, with fewer ties between surnames and more freedom in choosing the site.

- (b)

- From the results of the kernel density analysis, the degree of clustering for the mixed surname families courtyard house distribution is low (Figure 22) and scattered into pieces. Most of the mixed surname family courtyard houses are distributed in the area west of the Old Hui River and the area outside the wall in the south of the village. The overall layout is scattered, the average degree of clustering is low, there is no obvious spatial structure relationship, and there is a lack of internal order control and connection. In the early days of village construction, there was only a Xiangshui Bridge on the Old Hui River that connected the east and west of the village. The river barrier led to more families who came here for development or had weaker power gathering on the east side of the river. After the demolition of the wall, the surrounding trenches were gradually buried, and the people made developments towards the south outside of the wall. There was less communication among the families of mixed surnames, and the correlations among them were very weak, without forming a strong cluster.

| Mixed Surname | ||

|---|---|---|

| Standard deviation ellipse | Spatial distribution centre | No apparent representation of the elliptical centre. |

| Directional trends | Oblateness value (0.404), with a “southeast–northwest” distribution. | |

| Degree of centripetal tendency | Highest value of short axis length (206.192 m), not strongly centripetal. | |

| Kernel density | Degree of aggregation | Low degree of agglomeration, patchy and scattered distribution. |

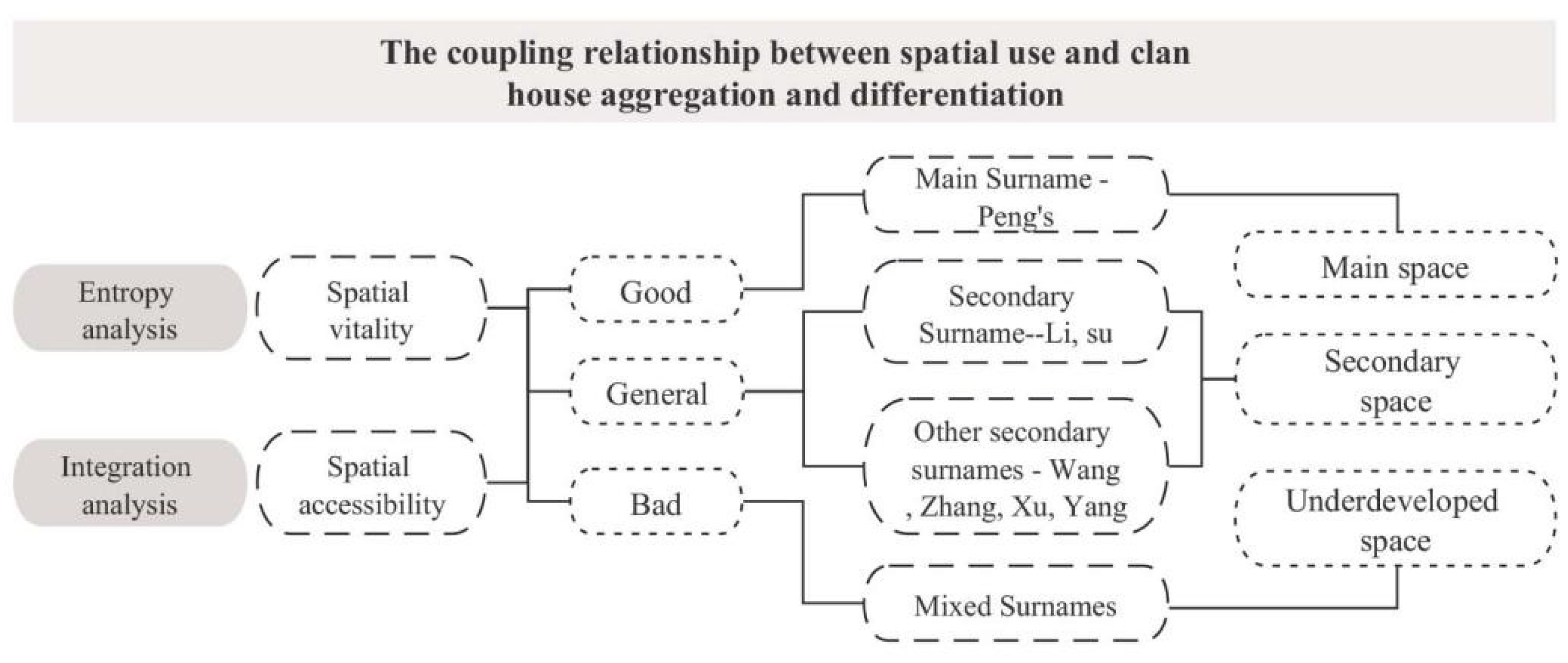

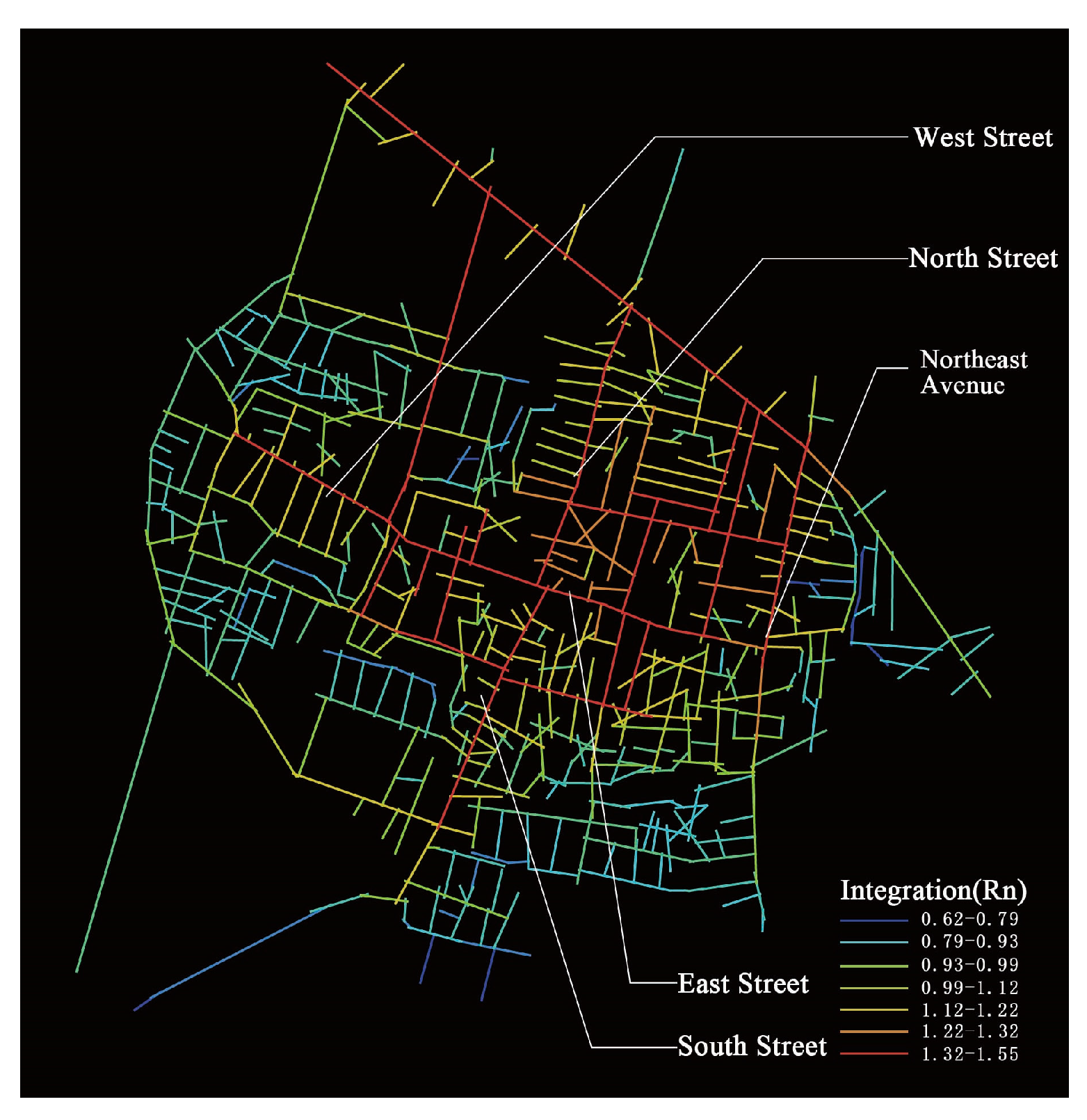

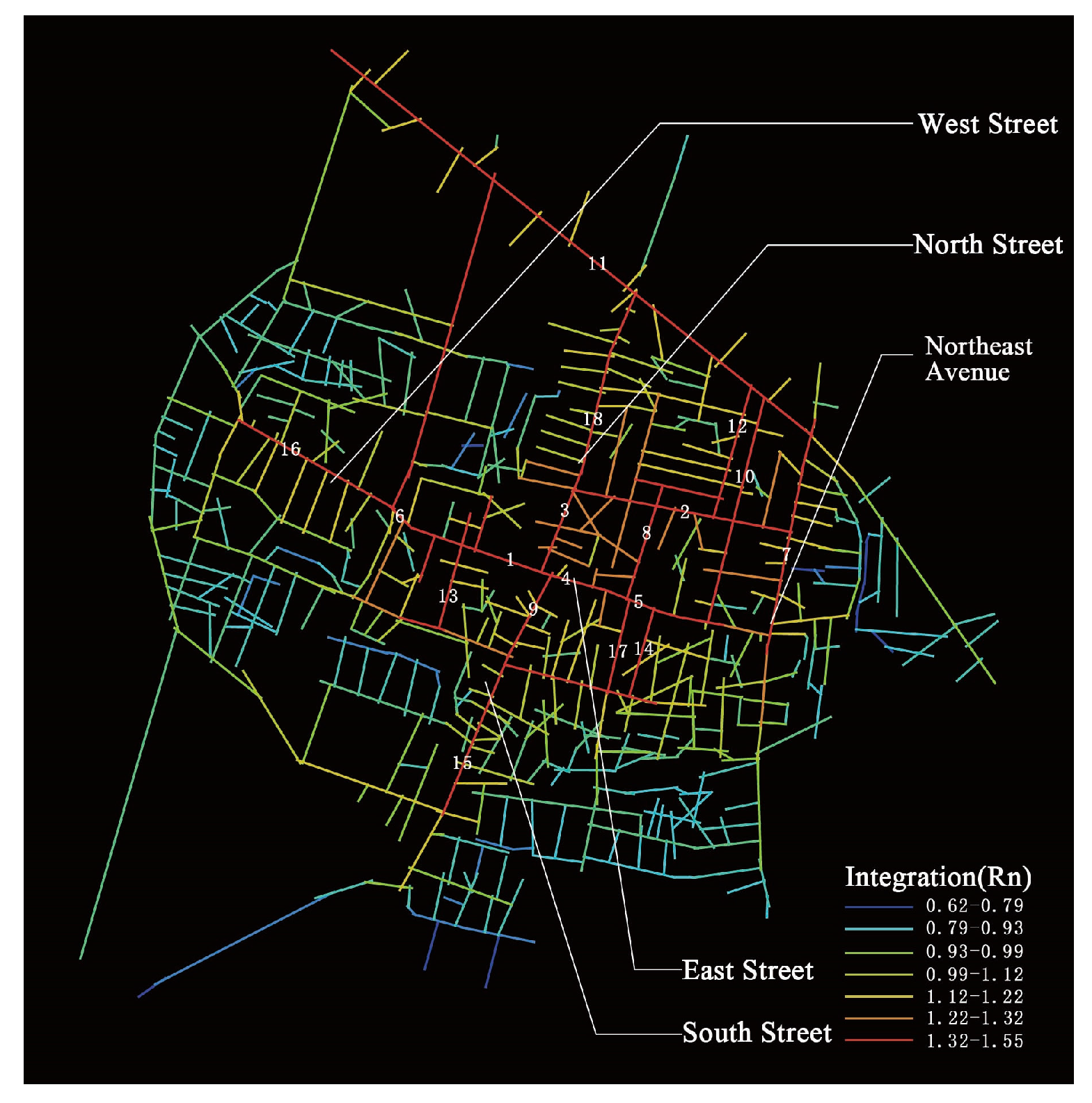

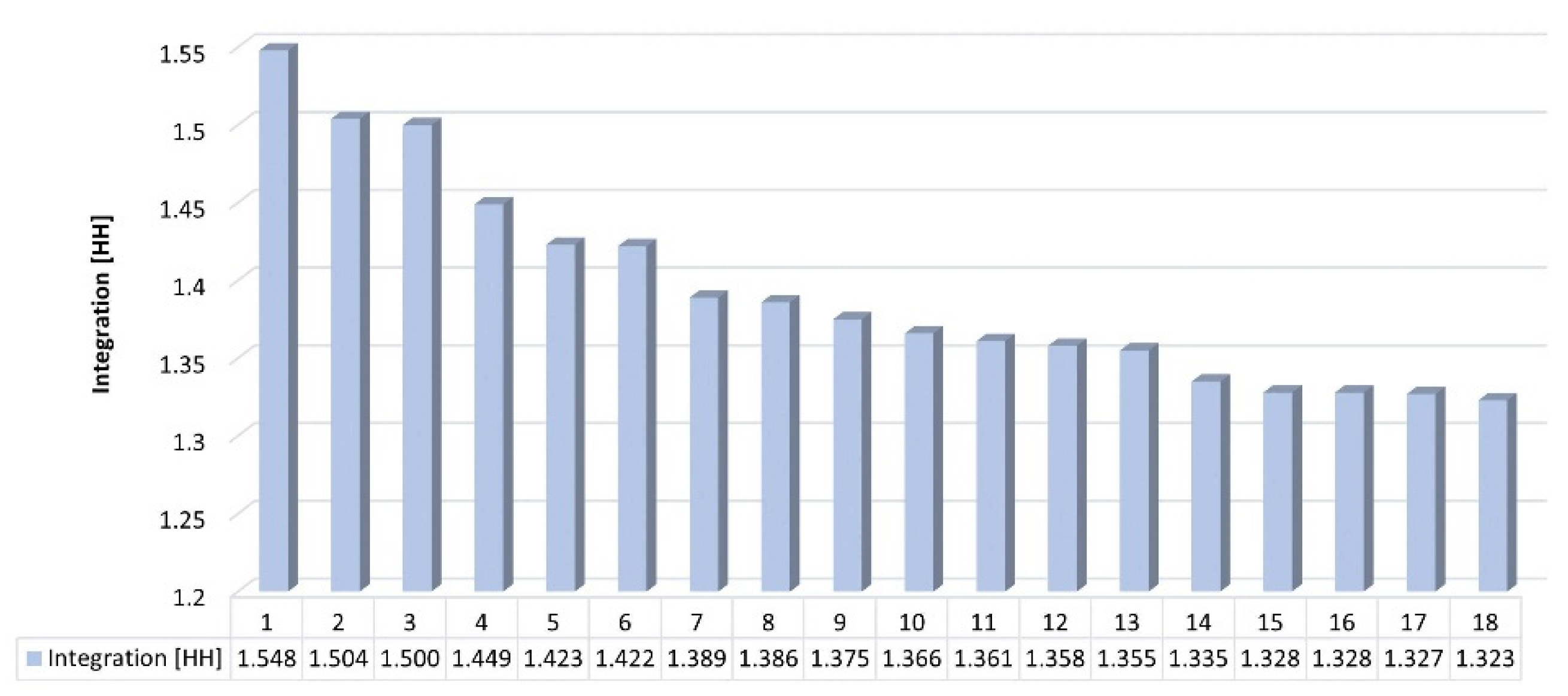

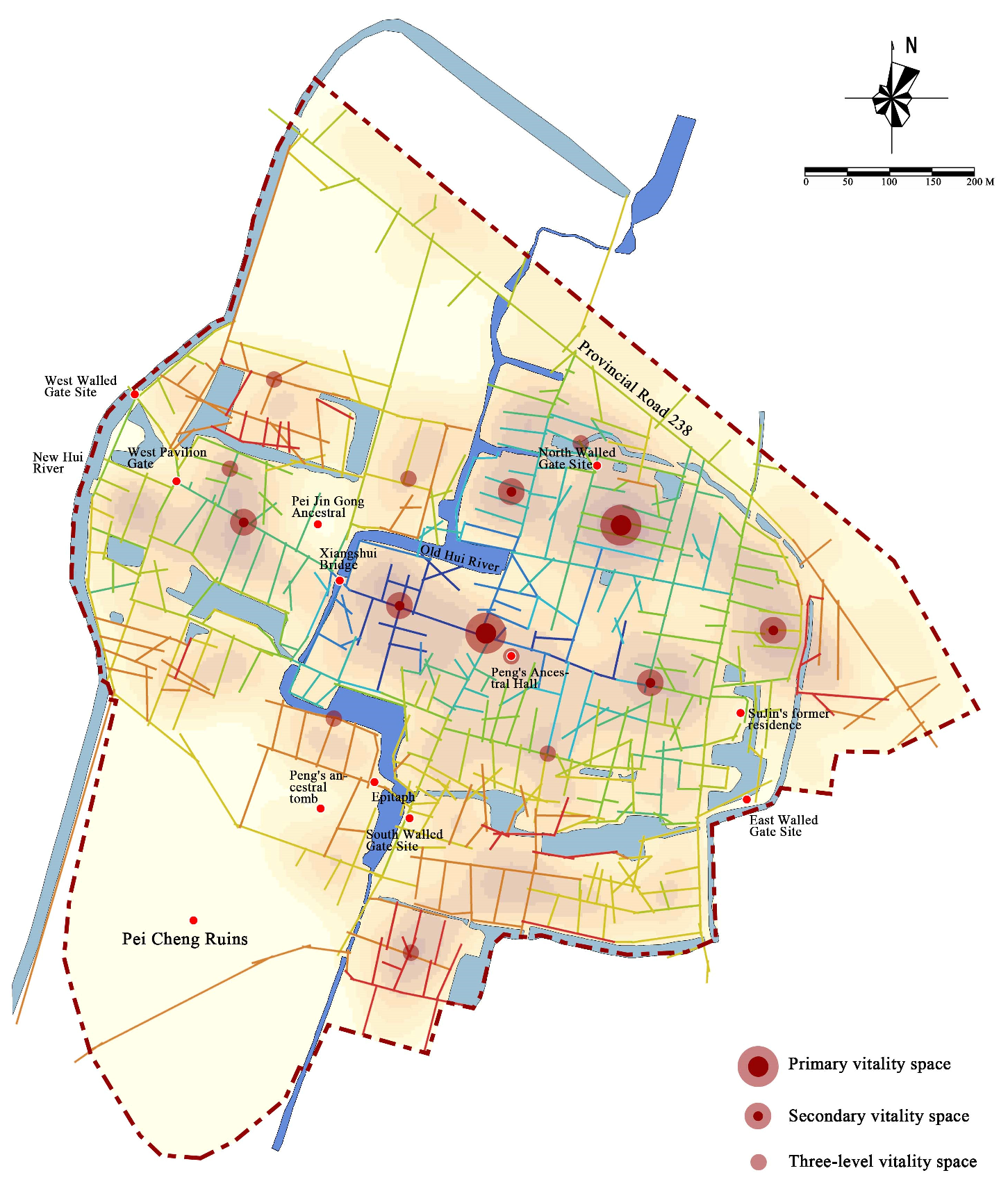

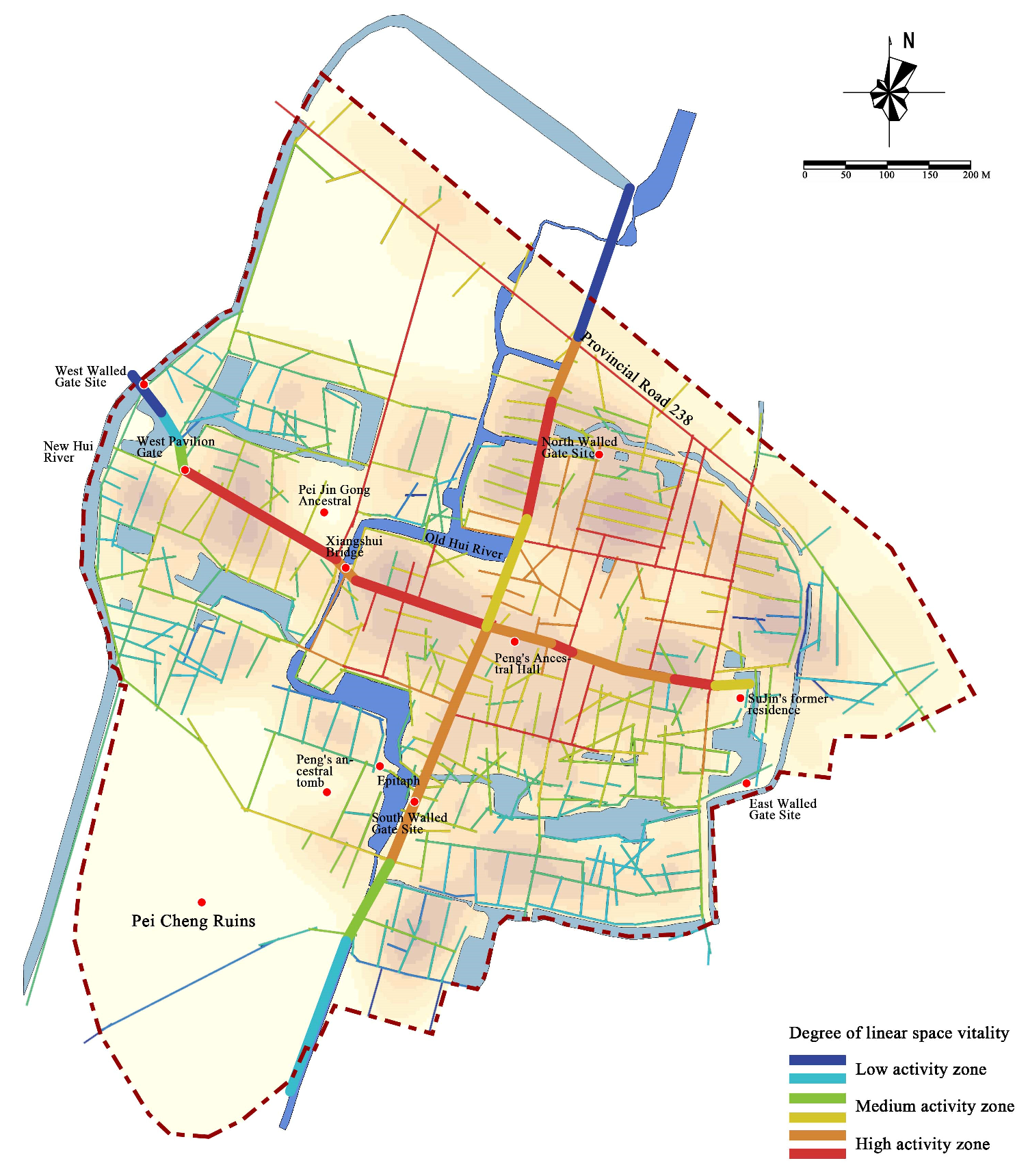

4.2. The Joint Relationship between Spatial Use and Clan Courtyard House Aggregation and Differentiation

4.2.1. Spatial Vitality and Distribution of Clan Courtyard Houses

4.2.2. Space Access and Clan Courtyard Houses Distribution

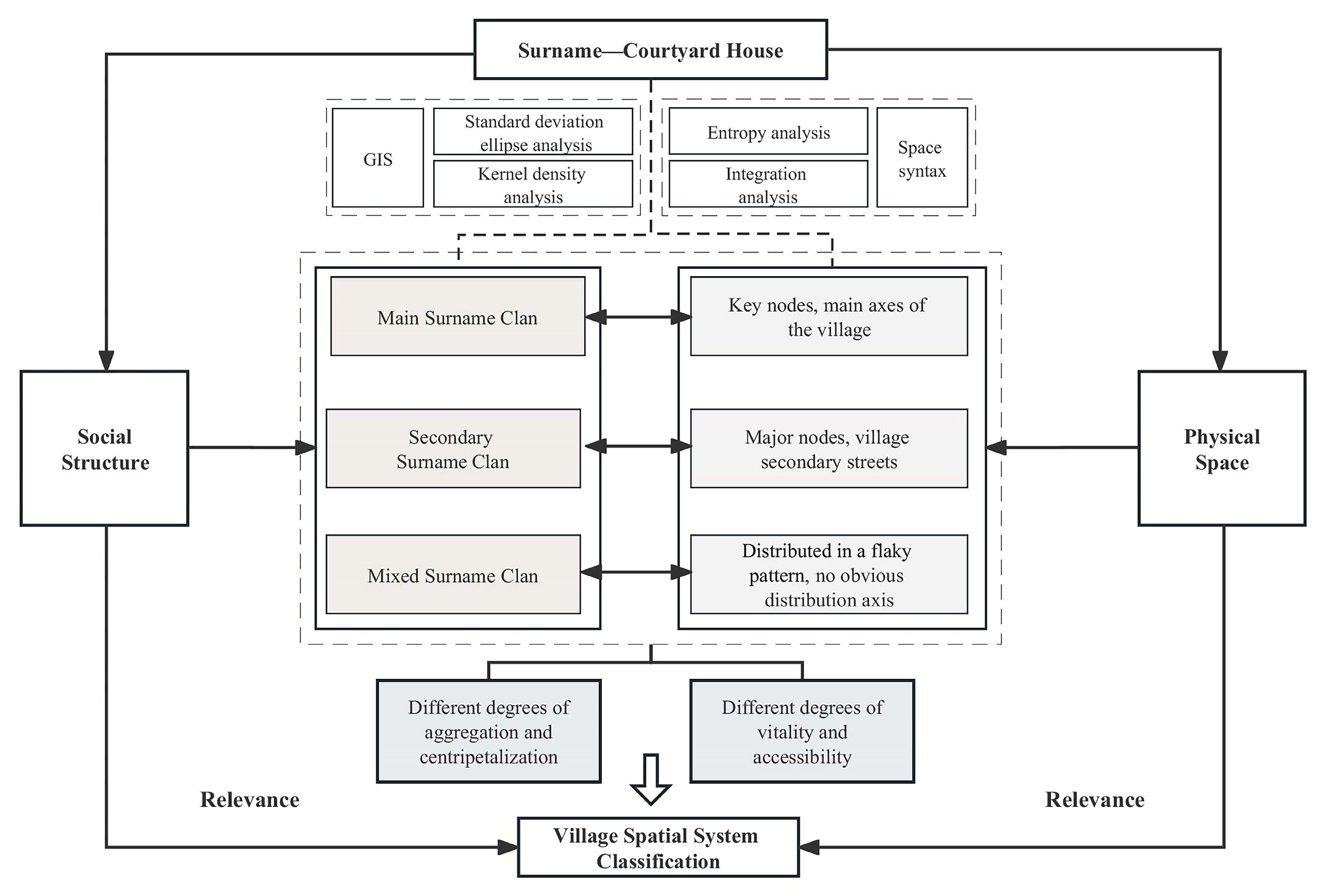

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Aggregation and centripetal tendency: The aggregation and divergence of primary and secondary surname clan courtyard houses in rural areas have a joint correlation with the spatial development structure of rural areas and the formation of key nodes. This is mainly reflected in the interconnection of the centripetal tendency, degree of aggregation, and high aggregation points of the courtyard houses. The main family name clan has an obvious spiritual core space, a strong centripetal tendency, and courtyard houses that easily produce high aggregation points that can form a series of tandem points dominating the main spatial structure of the rural area; in contrast, the courtyard houses have weak centripetal tendency, a relatively loose degree of aggregation, and a lack of cohesion.

- (2)

- Vitality and accessibility: The distribution of the primary and secondary surname clan courtyard houses in rural areas corresponds to the distribution of vitality points and the accessibility of space in rural areas. It is mainly reflected that the main family with the main surname will consciously choose the place with good space at the early stage of development and occupy the core space of the village, corresponding to the main space of village development; the secondary surname family is distributed on both sides of the main space road of the village with high accessibility, corresponding to the secondary space of village development; the mixed surname family is in the poor area of village development, corresponding to the underdeveloped space of the village.

- (3)

- Spatial system classification

7. Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tao, J.; Chen, H.; Xiao, D. Influences of the Natural Environment on Traditional Settlement Patterns: A Case Study of Hakka Traditional Settlements in Eastern Guangdong Province. J. Asian Arch. Build. Eng. 2017, 16, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fang, Q.; Li, Z. Cultural ecology cognition and heritage value of Huizhou traditional villages. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Strobl, J.; Min, Q.; Tan, M.; Cheng, F. Visualizing the cultural landscape gene of traditional settlements in China: A semiotic perspective. Herit. Sci. 2021, 9, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Zhang, X.; Ma, J.; Jia, Y. Cultural relationship between rural soundscape and space in Hmong villages in Guizhou. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Huang, B.; Deng, C.; Wan, Q.; Zhang, L.; Fei, Z.; Li, H. Rural settlement restructuring based on analysis of the peasant household symbiotic system at village level: A Case Study of Fengsi Village in Chongqing, China. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Fu, X.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, H. Representation, measurement and attribution of spatial order of traditional villages in southern Hunan. Geogr. Res. 2021, 40, 2722–2742. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Baimu, S.; Tong, J.; Wang, W. Geometric spatial structure of traditional Tibetan settlements of Degger County, China: A case study of four villages. Front. Arch. Res. 2018, 7, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Pu, F. Clustered and dispersed: Exploring the morphological evolution of traditional villages based on cellular automaton. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Shi, C.; Li, L. Study of the differences in the space order of traditional rural settlements. J. Asian Arch. Build. Eng. 2022, 22, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Tang, X.; Ren, Y.; Wang, Y. Research on the Spatial Pattern Characteristics of the Taihu Lake “Dock Village” Based on Microclimate: A Case Study of Tangli Village. Sustainability 2019, 11, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, H.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X. Evolution and transformation mechanism of the spatial structure of rural settlements from the perspective of long-term economic and social change: A case study of the Sunan region, China. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 93, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Wang, H.; Huang, A.; Xu, Y.; Lu, L.; Ji, Z. Identification and spatial-temporal evolution of rural “production-living-ecological” space from the perspective of villagers’ behavior—A case study of Ertai Town, Zhangjiakou City. Land Use Policy 2021, 106, 105457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xie, W.; Li, H. The spatial evolution process, characteristics and driving factors of traditional villages from the perspective of the cultural ecosystem: A case study of Chengkan Village. Habitat Int. 2020, 104, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Lv, Q. Multi-dimensional hollowing characteristics of traditional villages and its influence mechanism based on the micro-scale: A case study of Dongcun Village in Suzhou, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hathloul, S.; Edadan, N. Evolution of settlement pattern in Saudi Arabia: A historical analysis. Habitat Int. 1993, 17, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Song, K.; Pu, F. Laws and Trends of the Evolution of Traditional Villages in Plane Pattern. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, G.; Cai, Y. Correlation Between Spatial Structure and Familial Society of Wuyan Ancient Village, Huangyan District of Zhejiang Province. Planners 2020, 36, 58–64. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; He, Y. Adaptive Changes of Traditional Handicraft Villages under the Rule of Consanguinity Community: A Case Study of Xizhuang Village in Xinjiang County, Shanxi Province. City Plan. Rev. 2021, 45, 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Gu, Y. Revisiting the spatial form of traditional villages in Chaoshan, China. Open House Int. 2020, 45, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. The Development of Clan and Village in Jinzhong Area since Ming and Qing Dynasties. Master’s Thesis, Shanxi University, Taiyuan, China, 2017. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Q.; Xu, J.; Wei, Y. Clan in Transition: Societal Changes of Villages in China from the Perspective of Water Pollution. Sustainability 2018, 10, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, X.; Yuan, Z. Understanding the socio-cultural resilience of rural areas through the intergenerational relationship in transitional China: Case studies from Guangdong. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 97, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, B.; Joosten, M.; Richthofen, A.V.; Rupp, F. Land-allocation and clan-formation in modern residential developments in Oman. City Territ. Archit. 2018, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, Y.; Sun, L. A Study on the Courtyard Unit of Traditional Settlements Based on Clan Structure as Exemplified in Zoumatang Village, Ningbo. Archit. J. 2017, 02, 90–95. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. A study of the settlement space based on the clan of the main surname—Taking the ancient town of Futian in Ji’an City, Jiangxi Province as an example. Cult. Relics South. China 2019, 01, 274–283. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Q.; Zeng, W. A Study on the Conservation of Traditional Villages Based on the Perspective of “Social-Spatial” Linkages: The Case of Xin Zhang Yu Village in Ningbo; China Society of Urban Planning: Chengdu, China, 2020; pp. 227–242. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Henneberry, S.R.; Ni, J.; Radmehr, R.; Wei, C. Socio-cultural roots of rural settlement dispersion in Sichuan Basin: The perspective of Chinese lineage. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duly, C. The Houses of Mankind; Thames and Hudson: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Waterson, R. The Living House: An Anthropology of Architecture in South East Asia; Thames & Hudson: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Öztank, N. An Investigation of Traditional Turkish Wooden Houses. J. Asian Arch. Build. Eng. 2010, 9, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zhou, J.; Deng, Y. Heritage values of ancient vernacular residences in traditional villages in Western Hunan, China: Spatial patterns and influencing factors. Build. Environ. 2021, 188, 107473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C.; Ishikawa, S.; Silverstein, M. A Pattern Language: Towns, Building and Construction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Mehaffy, M.W.; Kryazheva, Y.; Rudd, A.; Salingaros, N.A. A New Pattern Language for Growing Regions: Places, Networks, Processes; Sustasis Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D. Introduction to Chinese Housing; Baihua Wenyi Publishing House: Tianjin, China, 2004; p. 31. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.H. Three Hakka Villages in Meixian County; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2007. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S.; Fujiyama, M.; Ishida, T. Spatial characteristics analysis of Eaves Gallery along the street in China: Take Hubei, Bashu, Jiangzhe areas as examples. J. Asian Arch. Build. Eng. 2019, 18, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fang, K.; Chen, L.; Furuya, N. The influence of atrium types on the consciousness of shared space in amalgamated traditional dwellings—A case study on traditional dwellings in Quanzhou City, Fujian Province, China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2019, 18, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Yu, M. Research on the Correlation Between Family Society and Courtyard House Space in Traditional Town Settlements: A Case Study of Shangshudi Historical and Cultural District in Taining, Fujian Province. J. Hum. Settl. West China 2022, 37, 132–138. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Yunitsyna, A.; Shtepani, E. Investigating the socio-spatial relations of the built environment using the Space Syntax analysis—A case study of Tirana City. Cities 2023, 133, 104147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faragó, T. Kinship in rural Hungary during the eighteenth century: The findings of a case study. Hist. Fam. 1998, 3, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keene, J.R.; Batson, C.D. Under One Roof: A Review of Research on Intergenerational Coresidence and Multigenerational Households in the United States. Sociol. Compass 2010, 4, 642–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalet, J. Where does guanxi come from? Bao, shu, and renqing in Chinese connections. Asian J. Soc. Sci. 2021, 49, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Jia, Z.; Wang, N.; Fang, M. Sustainable Mountain Village Construction Adapted to Livelihood, Topography, and Hydrology: A Case of Dong Villages in Southeast Guizhou, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, D. The Research of Traditional Villages’ Spatial Form in the Central Plains. Ph.D. Dissertation, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2015. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X. Research on Evolution and Integration Srategies of Traditional Villages’ Texture Based on the Clan’ s Structure. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2015. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism; Gerth, H.H., Ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Durie, B. Clans, Families and Kinship Structures in Scotland—An Essay. Genealogy 2022, 6, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Yuan, Y. Multi-dimensionality and the totality of rural spatial restructuring from the perspective of the rural space system: A case study of traditional villages in the ancient Huizhou region, China. Habitat Int. 2019, 94, 102062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Wei, F.; Pu, J.; Zhang, X.; Weng, Q. Spatial-temporal evolution of typical rural settlements in northern Jiangsu Province: A case study of Donghai County. J. China Agric. Univ. 2023, 28, 208–222. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Jia, Y.; Lv, L.; Xu, X. Tourismification of Historic Cities: Spatio-temporal Process, Function Transformation and Correlation Coordination Based on A Case Study of Tianshui Historic City. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2021, 41, 1371–1379. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Stasch, R. Afterword: Village space and the experience of difference and hierarchy between normative orders. Crit. Anthropol. 2017, 37, 440–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Dai, Y.; Lin, S.; Ye, H. Clan culture and family ownership concentration: Evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2021, 70, 101692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Wu, Q.; Li, C.; Lo, T.; Chen, F. Spatial social interaction: An explanatory framework of urban space vitality and its preliminary verification. Cities 2022, 121, 103487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Han, X.; He, J.; Jung, T. Measuring residents’ perceptions of city streets to inform better street planning through deep learning and space syntax. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 190, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Yan, J.; Yang, X. The Research on Activities of Underground Commercial Space of Rail Transit Station Based on Coordinated Development: Analysis of Underground Commercial Space of Jinhui Squara in Tianjin. Mod. Urban Res. 2016, 08, 100–105. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Ju, S.; Wang, W.; Su, H.; Wang, L. Intergenerational and gender differences in satisfaction of farmers with rural public space: Insights from traditional village in Northwest China. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 146, 102770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Lin, K.; Gu, H.; Liao, C.; Liu, S.; Ou, Q. Spatio-Temporal Evolution of Shawan Ancient Town in Guangzhou from the Perspective of Spatial Syntax. Trop. Geogr. 2020, 40, 970–980. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Centre X Coordinate | Centre Y Coordinate | Long Axis Length/m | Short Axis Length/m | Oblateness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peng | 2436.051 | 889.163 | 329.751 | 158.363 | 0.520 |

| Li | 2438.180 | 889.223 | 226.035 | 186.634 | 0.174 |

| Su | 2438.826 | 889.563 | 178.976 | 114.890 | 0.358 |

| Wang | 2435.045 | 889.183 | 343.765 | 193.540 | 0.437 |

| Zhang | 2434.456 | 889.631 | 315.003 | 198.116 | 0.371 |

| Xu | 2436.988 | 890.006 | 214.342 | 170.117 | 0.206 |

| Yang | 2437.073 | 889.867 | 336.973 | 136.178 | 0.596 |

| Mixed surname | 2434.876 | 889.580 | 346.085 | 206.192 | 0.404 |

| Clan | Aggregation Tendency | Centripetal Tendency | Rural Distribution Area and Spatial Structure | Key Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peng | Strong | Stronger | Development along the north–south axis of the village | Cross Street centre, the Peng’s Old Ancestral Hall |

| Li | Stronger | Weaker | Two families are staggered in the east side of the village near Northeast Avenue | None |

| Su | Stronger | Stronger | Su Jin’s former residence | |

| Wang, Zhang, Xu, and other secondary surnames | Weak | Weak | Mostly forming small clusters along East–West Street of the village | None |

| Mixed surnames | Very weak | Very weak | No obvious directionality, in the shape of a patch | West side of the Old Hui River, outside the fortress wall |

| Clan | Vitality | Reachability | Village Space Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Surname—Peng | Strong | Strong | Primary space |

| Secondary Surnames—Li, Su | Weaker | Strong | Secondary space |

| Other secondary surnames—Wang, Zhang, Xu, etc. | Stronger | Weaker | Secondary space |

| Mixed surnames | Weak | Weak | Underdeveloped space |

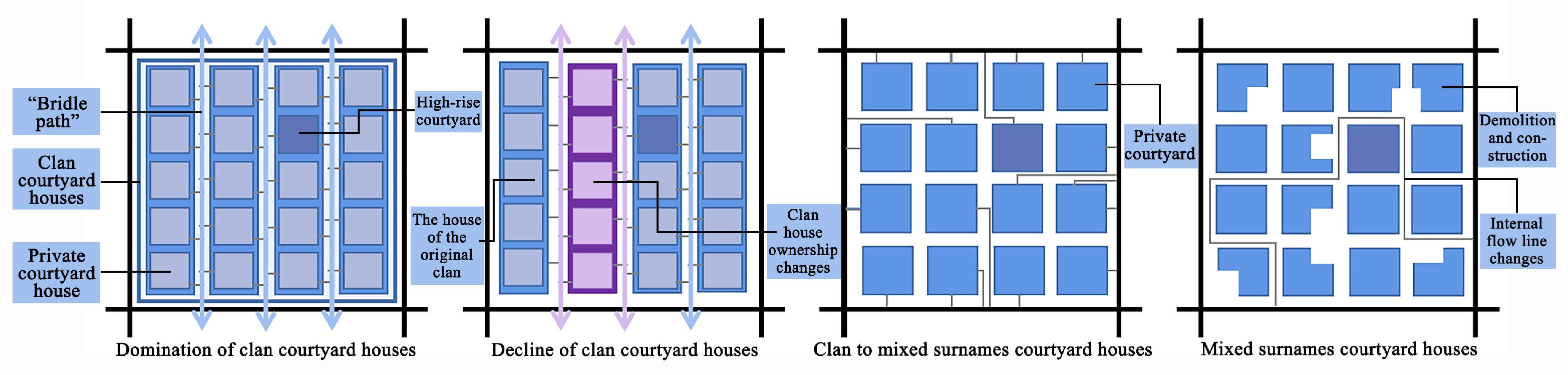

| Time | Trait | Surname | Spatial Pattern | Degree of Aggregation | Centripetal Tendency | Clan Characteristics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage one | Ming—Qing middle period | Domination of clan courtyard houses | Peng | Clan courtyard house + “horse path” | Strong | Strong (high-rise courtyard) | One name, one family |

| Stage two | Middle Qing Dynasty—late Qing Dynasty | Decline of clan courtyard houses | Peng, Su, and Li | Clan courtyard house | Stronger | Strong, three centres | Primary and secondary family names, strong clan |

| Stage three | Republic of China— before the founding of the People’s Republic of China | Clan to mixed surname courtyard houses | Peng, Su, Li, and He | Private courtyard house | Weak | Weak | There are many surnames, and the clan character is weakened |

| Stage four | After the founding of the People’s Republic of China | Mixed surname courtyard houses | Mixed surnames | Private courtyard house; separate export | Weak | Weak | Mixed surname, clan nature is not strong |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, D.; Shi, Z.; Cheng, M. A Study on the Spatial Pattern of Traditional Villages from the Perspective of Courtyard House Distribution. Buildings 2023, 13, 1913. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13081913

Zhang D, Shi Z, Cheng M. A Study on the Spatial Pattern of Traditional Villages from the Perspective of Courtyard House Distribution. Buildings. 2023; 13(8):1913. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13081913

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Dong, Zixuan Shi, and Mingyang Cheng. 2023. "A Study on the Spatial Pattern of Traditional Villages from the Perspective of Courtyard House Distribution" Buildings 13, no. 8: 1913. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13081913