1. Introduction

The formation of commercial streets is a product of socio-economic development and cultural fusion, while the spatial pattern and social structure of historical commercial streets authentically reflect the historical evolution of cities [

1]. Studies related to scene experience have transitioned through a process from spatial materialization to emotional empowerment and cultural identity, delving into discussions and explorations of the spirit of place, continuity of memory, and a sense of locality. Since the 1976 UNESCO recommendations regarding the conservation and contemporary role of historic areas, the restoration of historical contexts has garnered significant attention, with cultural activation becoming a major focus [

2] and attracting widespread interest [

3]. In 2015, regulations by the Guangdong Provincial Government emphasized the importance of preserving heritage resources for economic transition and cultural uniqueness, specifically highlighting the key role of Beijing Road commercial street in this aspect [

4]. Despite policy support and societal efforts, contradictions still exist between urban renewal and cultural heritage preservation [

5]. These challenges include balancing traditional and modern functionalities [

6], protecting and assessing the value of intangible heritage [

7], coordinating commercial development with cultural conservation, and managing the needs of tourists while ensuring the quality of life for residents. Currently, the revitalization of historical streets faces challenges of cultural loss and a decline in homogenization trends [

8]. In fact, these contradictions reflect an over-pursuit of consumerist cultural experiences and a diminishing of place identity and cultural belonging, leading to a gradual weakening of regional cultural context and a loss of value recognition [

9].

Historical commercial streets bear the memory and culture of cities; their material traces witness the transformation of culture. These districts not only observe the changes in society and culture but also serve as windows to understand past social and cultural dynamics, with their static and dynamic elements acting as mediums to display past societal landscapes. In terms of research on scene perception experience, scholars have made significant progress.

Boumezoued et al. [

10] and Degen and Rose [

11] contend that tactile, auditory, and visual elements in material culture are vital for understanding historical sites, especially the role of sound in reconstructing memories. On an individual level, the perception of history is subjective and unique. Addressing these differences, McDonnell et al. [

12] emphasized the role of cultural resonance, suggesting that a shared cultural background can strengthen an individual’s connection with the environment. Tally [

13] proposed three approaches to experiencing historical narratives: (1) Directly perceiving the physical environment, aiding individuals in establishing a basic understanding and emotional connection with the place; (2) Reconstructing the authenticity of historical scenes, enhancing the spiritual and social value of locations through emotional and identity symbolism; (3) Personal re-enactment of historical narratives, a process influenced by individual experiences, knowledge, and cultural background.

On the other hand, Orianne and Eustache [

14] pointed out that individual identity often intertwines with collective memory and the spirit of place, perpetuated through historical narratives and cultural activities. Heersmink [

15] emphasized the resonance of individual and collective memories as critical to cultural identity, offering a sense of historical continuity and cultural belonging. Karimi et al. [

16] analyzed the multidimensional construction process of individual identification with historical commercial streets, considering it an outcome of the interaction between cultural traditions and social interactions. They also noted significant differences in the formation of a sense of identity among various age groups, genders, or cultural backgrounds, highlighting the complexity and diversity of cultural identity and deepening our understanding of the interaction between social–cultural elements and individual cognition.

Related studies have focused on the role of multi-sensory experiences in the interpretation of cultural heritage, integrating perceptual psychology with cultural geography. The interaction between material and intangible culture has been incorporated as an influencing factor in cultural scene perception, leading to two topics of discussion: (1) how material cultural heritage through sensory narratives affects individual cognition and emotional experience; (2) the function of intangible cultural heritage in constructing social memory and identity. Although some scholars have explored the inheritance and transformation of intangible heritage in historical commercial streets, there is still a lack of comprehensive research, particularly in empirically assessing how authenticity, theatricality, and legitimacy of scene perception collectively impact individual experiences.

This study aims to analyze the scene perception experience of historical commercial streets and its impact on cultural memory and identity. Compared to other local cultural landscapes, Beijing Road pedestrian street in Guangzhou is particularly exemplary in combining traditional maintenance with modern commercial activities, which is evident in the mismatch between cultural restoration and modern commercial demands. Some ancient buildings have been converted into retail stores or restaurants, with interior renovations not matching historical styles and damaging the original historical atmosphere. This phenomenon has raised public concerns about scene authenticity, leading to a separation of material and intangible cultural attributes, representing not only a physical loss but also a disruption of cultural continuity. Therefore, this paper holds significant research value and social relevance.

2. Methodology

2.1. Site Overview

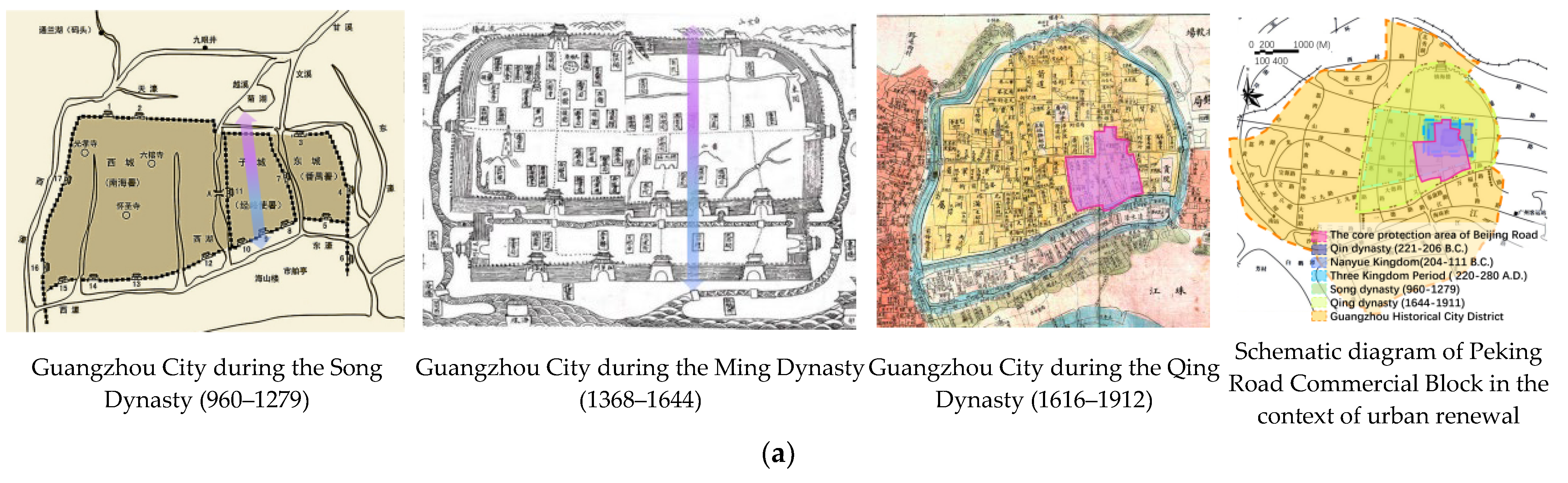

Beijing Road, a historical and cultural pedestrian street, is one of the 26 designated historical and cultural districts located in the Yuexiu District of Guangzhou. This street has served as the unaltered and uninterrupted traditional central axis of Guangzhou for over two thousand years, epitomizing the political and cultural center of Lingnan and marking the origin of the Maritime Silk Road. In September 2017, the Beijing Road Cultural Tourism Area was honored as a World Outstanding Tourist Destination. By December 2018, it was selected as one of the first national pilot projects for pedestrian street renovation and enhancement. In April 2020, it was included in the scope of protection for Guangdong Province’s historical and cultural districts. Subsequently, in July 2021, it was acclaimed as a “National Model Pedestrian Street”.

As a commercial area rich in history, it not only preserves the city’s historical memory but also serves as a pivotal region for urban cultural heritage. Following the implementation of protective policies such as the “Guangzhou Historical and Cultural City Protection Plan” and the “2021–2035 Guangdong Province Historical and Cultural Street District Guangzhou City Beijing Road Historical and Cultural Street District Protection Plan”, a core protection area of 13.68 hectares and a construction control area of 8.49 hectares were delineated (

Figure 1). The district houses four national key cultural relics protection units and five provincial-level cultural relics protection units, retaining multiple significant historical sites.

2.2. Advantages of Applying Scene Theory to Historical, Commercial, and Cultural Streets

The concept of ‘scene’ initially originated in the fields of drama and film and later developed in cognitive psychology. Using CiteSpace, a timeline cluster diagram of key terms in scene theory was created, focusing on cultural policy, macro urban development recommendations, urban cultural space creation, and cultural consumption. In

Figure 2a, nodes on the timeline indicate the citation history and frequency of literature, with the change in color representing the passage of time and the thickness of the nodes indicating citation frequency.

Barker [

17] conducted early studies on the influence of real scenes on behavior. In 1959, Peacock [

18] introduced drama theory into sociological analysis. Additionally, Gibson [

19] proposed the concept of ‘situational perception,’ emphasizing the guiding role of the environment on behavior, laying the foundation for scene theory. With the advancement of electronic media technology, Meyrowitz [

20] studied the social ‘scene’ structure. The urban transformation led Silver [

21] to clearly define scene theory, positing that human behavior is formed in specific environments and influenced by material attributes and social meanings.

Scene theory has been widely applied in the study of scene perception in historical and cultural streets, gaining continuous attention since 1996 (

Figure 2b). Research topics have expanded from cultural heritage preservation to value reconstruction, cultural tourism, and urban renewal. The figure illustrates a timeline cluster diagram of keywords related to historical streets. Recent focal points include human capital, emerging industries, changes in consumption structures, and meeting real needs. Chinese scholars typically use the scene theory framework to analyze cultural policies and spatial resources, proposing developmental recommendations. Nevertheless, audience-centric development research for historical commercial areas remains relatively scarce.

2.3. Research Method

Given the complexity of factors influencing the cultural experience of scene perception, this study is an integrative research effort combining focus group interviews, points of interest (POI) data analysis, and the analytical hierarchy process (AHP). The focus group interview method, a qualitative research technique, involves guiding a specific group of individuals to discuss a particular topic for data collection [

10]. This method facilitates the revelation of underlying group norms and cultural dynamics through encouraging interaction and discussion among participants, thereby offering profound insights into understanding the perception of cultural experiences within a scene. AHP, proposed in the 1970s by American operations researcher Saaty [

22], is a multi-objective decision analysis method that combines qualitative and quantitative analyses. It constructs a multi-level analytical structural model to determine the weight of components at different levels, making decision problems quantifiable. The basic idea of hierarchical analysis is a systematic approach of decomposition followed by synthesis. Analyzing a problem involves breaking it down into different levels of components, forming a multi-level analytical structure model, and ultimately resolving the relative weight of the lowest level components in relation to the highest level. This method is now widely applied in urban spaces and cultural heritage fields [

23,

24].

2.4. Questionnaire Design and Evaluation Modeling

This study employed focus group discussions to construct secondary indicators for the survey questionnaire. We invited seven expert scholars, three females and four males, who aligned with the research direction and possessed in-depth knowledge about Beijing Road. The discussion revolved around three primary indicators of scene theory: authenticity, theatricality, and legitimacy, focusing on the historic commercial district of Beijing Road.

Authenticity refers to the originality of entities, closely linked with identity recognition. It emphasizes the strong connection between regional identity and cultural identification. This dimension involves tourists’ perception and evaluation of the historical and cultural values of the commercial district, reflecting the preservation and inheritance of regional characteristics and cultural heritage. Theatricality focuses on the impact of the spatial environment on individual perception and emotion, including interactivity of aesthetics, attractiveness, and experience. In the context of historic commercial districts, theatricality manifests through the integration of commercial activities and cultural exhibitions and the significant role of spatial design and artistic expression in creating appeal and enhancing the visitor experience. This element underscores dynamic components in the scene, such as street art, festive events, and interactive experiences, and how these collectively enhance the overall visitor experience. Legitimacy involves the equity of socio-economic factors in spatial distribution, focusing on the inclusiveness and participation of different social groups within the commercial district. It concerns the equality of capital and power spaces and the role of public policy and market forces in forming and maintaining this equality. The discussion on legitimacy highlights the role of commercial districts as social interaction spaces aimed at fostering community involvement, business diversity, and economic sustainability while ensuring equitable access and utilization of space by different social groups.

Initially, basic site information was provided to the experts, encouraging open discussions on factors influencing scene perception experience. Subsequently, these viewpoints and factors were explored in-depth to better understand the nature and mechanisms affecting the scene perception experience, thereby clarifying the specific dimensions of secondary indicators. This led to the identification of 3–5 tertiary indicators under each secondary indicator, with experts invited to score and rank these using the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) method. Finally, based on the weighted importance of each indicator layer, a scene perception measurement model framework (

Figure 3) and evaluation system (

Table 1) were constructed.

For the various indicators listed in

Table 1, this study employed a 1–9 scale method for evaluation (

Table 2), resulting in the judgment matrix

.

can be calculated using Equation (1), while

can be derived from Equation (2). The evaluation indices of the seven experts were assigned values, averaged, and rounded to ensure fair and objective results. Our aim was to calculate the characteristic vector

, which corresponds to the largest eigenvalue

of the judgment matrix

, representing the weight distribution of the indicators. Subsequently, each column of the judgment matrix

was normalized using Equation (3) to obtain

. Following this,

was summarized using Equation (4) to derive

. The next step involved standardizing

through Equation (5) to produce

. Finally, the largest eigenvalue

of the judgment matrix

was calculated using Equation (6).

In Equations (1) and (2),

denotes any element within the matrix,

represents the number of rows,

stands for the number of columns, and

signifies the order of the matrix. Consequently,

symbolizes the element

located in row

and column

of the

order matrix

.

In the Equation (3), the elements of matrix H are normalized column-wise using the sum-product method, resulting in

.

denotes the summation symbol.

represents the summation starting from 1 and continuing up to

.

In the Equation (4),

represents the value obtained after normalizing all elements in the column.

In Equation (5),

represents the eigenvector.

In Equation (6),

represents the judgment matrix,

is the maximum eigenvalue of

,

denotes the order of

, and

is the eigenvector. Within

,

signifies the

-th element of vector

.

In Equation (7),

represents the consistency index. When

is less than 0.1, the judgment matrix is considered to have consistency; otherwise, adjustments are required.

In Equation (8), represents the consistency ratio, while denotes the average value of the consistency index, which is related to the order of the judgment matrix.

After determining the weight values of each layer of indicators, it is necessary to conduct a consistency test on the judgment matrix . The consistency index is calculated using Equation (7). Given that different scales have varying random consistency indices, the consistency ratio , an indicator for evaluating consistency, is calculated using Equation (8), where represents the random consistency index. Regarding the consistency ratio, generally, when = 0, it is considered that the judgment matrix is consistent; if < 0.1, then can be regarded as a completely consistent matrix; if > 0.1, then the judgment matrix is deemed inconsistent. When the judgment matrix has satisfactory consistency, is slightly larger than the matrix order , while the other eigenvalues are close to zero. Finally, based on this, a hierarchical total ranking, comprehensive evaluation, and graded study of each evaluation element are conducted.

2.5. Questionnaire Distribution Process

The distribution of the survey took place between March and May 2022. On weekdays, data collection occurred from 7 pm to 9 pm, while on holidays, it extended from 2 pm to 8 pm, aligning with peak periods for sightseeing and shopping. The respondents included visiting tourists, local residents, and individuals employed in the area (

Figure 4). The survey primarily focused on the impact of various factors on the on-scene experience, including historical sites, traditional architecture, time-honored brands, intangible cultural heritage, digital experiences, night economy, and cultural–creative spaces. For elderly tourists experiencing difficulties understanding the questionnaire, survey personnel provided one-on-one assistance to explain and complete data collection to ensure its authenticity.

5. Discussion

Descriptive analysis indicates that visitors have moderate overall satisfaction with Beijing Road, with scores for each perception element being medium, suggesting that the overall experience of the historical street needs enhancement (mean scores of each perception element range between 2.6 and 3.5, i.e., between ‘average’ and ‘relatively satisfied’). Among different perception dimensions, visitors are more satisfied with policy protection (3.20) but rate traditional foods lower (2.69), indicating an inadequate experience of regional characteristics. The attractiveness of cultural activities scores relatively high (3.19), while the functionality score of the shopping experience and commercial services is lower (2.96), indicating a need for improvement in commercial services. The regression analysis reveals that culture, regionality, aesthetics, attractiveness, functionality, and autonomy collectively form the perceptual evaluative dimensions of a cultural scene. Beyond fulfilling basic functional needs, aesthetics (with a coefficient of 0.770) and cultural perception (0.707) substantially contribute, signifying their decisive role in enhancing the overall quality of visitors’ scene perception.

In the dimension of authenticity, heritage sites and time-honored brand foods emerge as key elements, underscoring the importance placed on historical and cultural heritage [

29]. While historical and cultural characteristics of the district, intangible cultural heritage projects, and festive activities play a role in augmenting perceptual experience [

30], further integration and deepening of these elements are necessary. In the theatricality dimension, the street environment and the cultural creation of art are identified as primary factors, reflecting an emphasis on artistic forms and environmental ambiance [

31]. The visual effects and popular elements of social media, though secondary, play a specific role in enhancing experiences. In the legitimacy dimension, the diversity of commerce and public services is found to be crucial in shaping experiential perceptions, being pivotal in building consumer trust [

32]. Recreational dining, entertainment, public services, and community participation, while secondary, contribute to enhancing a sense of community belonging and cultural identity.

Previous studies have delved into the perceptions of authenticity, theatricality, and legitimacy among users regarding historic commercial districts. This paper employs Gaode Map to extract point of interest (POI) data from Beijing Road pedestrian street, categorizing these data into several hierarchical levels: major categories, subcategories, and minor classifications. Upon amalgamating similar categories, a total of seven major categories and twenty-six subcategories were identified. For instance, the category closely related to local residents’ daily life, namely the residential and living POIs, encompasses four subcategories: residential complexes, beauty and hair salons, everyday shopping, and living services. Additionally, under the major category of Cultural Tourism, the data include subcategories such as heritage sites, historical buildings, hotel apartments, and related services. The statistical analysis of these categorized elements aids in pinpointing the critical factors that influence the experiential aspects of the street scene (

Figure 11). On Guangzhou’s Beijing Road commercial pedestrian street, shopping (47%) and dining (21%) are most popular, primarily located in main streets and major malls. Life service categories comprise 12% of POIs, with beauty and hairdressing being the most (46% of life services). Though historical sightseeing and cultural education facilities account for only 2% and 3%, respectively, their distribution is even. Overall, this commercial area is dominated by shopping, dining, and entertainment, with fewer historical and educational facilities.

Additionally, the survey respondents were predominantly young and highly educated, with 72.5% being students and employed individuals, slightly more of whom were women. In light of previous research findings, this demographic distribution reflects several phenomena: (1) young, educated individuals have heightened expectations regarding the cultural and aesthetic experiences in historic commercial districts; (2) women are more sensitive to the aesthetic and cultural elements of commercial pedestrian streets, potentially demanding higher standards for cultural and artistic experiences; (3) tourists with diverse socio-economic backgrounds have varying expectations for the functionality and diversity of commercial pedestrian streets, highlighting both challenges and opportunities in meeting the needs of different consumer groups.

By constructing a framework model of scene experience authenticity, theatricality, and legitimacy, this study enriches the research content of scene theory. It validates the applicability and effectiveness of the model using Guangzhou’s Beijing Road commercial pedestrian street as a case study. Compared to the study by Hassadee et al. [

33], this paper highlights the dominant role of cultural relics and traditional foods in the perception of historical continuity, embodying the specific manifestation of individual and group cultural identity construction, thereby responding to their viewpoint. Regarding the role of cultural memory, this paper aligns with the findings of Özdemir [

34], acknowledging the critical role of cultural memory resonance in forming cultural identity and revealing the importance of cultural activities in enhancing group cultural belonging.

Research by Sussman et al. [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39] explored pedestrians’ unconscious responses to street information from a visual attention perspective, underscoring the critical role of environmental visual elements in urban spatial perception. They noted that pedestrians’ unconscious responses are primarily manifested in the following ways: (1) visual capture by environmental cues, such as how the colors, signage, and facades of streets capture pedestrians’ visual attention; (2) cognitive processing of visual information, which involves how pedestrians interpret and internalize visual information in the street environment, forming perceptions and memories; (3) the interaction between visual elements and behavior, namely how visual elements influence pedestrians’ actions and route choices.

Although this study did not directly measure pedestrians’ visual attention during their experience, the findings echo those of Sussman et al. In terms of authenticity perception, the lower evaluation of traditional foods and creative arts in the Beijing Road area may partly be due to a lack or deficiency in the visual narration of these elements. The visual design of the street, including architectural façades, color use, and signage, is crucial in enhancing visitors’ perception of historical and cultural heritage. Regarding theatricality perception, the central role of art and cultural landscapes on Beijing Road is vital for visitors’ theatrical experience, and the visual presentation of these elements likely affects their overall perception. Therefore, strengthening the visual narrative through vibrant colors, attractive storefront designs, and environmental art may enhance visitors’ theatrical experience. Lastly, in the legitimacy perception dimension, the diversified commercial formats and policy safeguards on Beijing Road, as key factors influencing the legitimacy of the experience, can be reinforced through visual language.

While this paper detailedly analyzes factors such as cultural, regional, and aesthetic influences on-scene experience, their impact may vary across groups. Additionally, relying on feedback from visitors during shopping peak hours may not comprehensively reflect all visitors’ perception experiences. Future research should extend the data collection period to include different seasons, holidays, and special events for a more comprehensive dataset. Further, subdividing respondent groups could explore perceptual differences among tourists of varying ages, cultural backgrounds, educational levels, and nationalities.

6. Conclusions

Our findings are as follows: (1) visitors rate Beijing Road’s traditional cuisine, cultural creative arts, and Lingnan’s intangible cultural heritage lower; (2) most visitors affirm policy protection measures, yet the lack of perception of local characteristics reveals inadequate communication of local cultural features in visitor experiences; (3) although Beijing Road’s cultural activities are attractive, satisfaction with the functionality of commercial services and shopping experiences is low; (4) historical relics and traditional cuisine are leading factors, highlighting public attention to cultural heritage, but the role of historical cultural features and festival activities is relatively marginalized; (5) in the theatricality dimension, the district’s environment and cultural arts are core elements of visitors’ experience, emphasizing the importance of environment ambiance and artistic creation in creating visitor perception, yet modern visual and trendy elements contribute less; (6) in the legitimacy dimension, diversified business formats and policy support are major factors influencing scene experience, reflecting the role of market diversity and public services in building consumer trust.

This study suggests that the landscape design of historical and cultural streets should prioritize the experiential preferences of visitors to promote cultural identity and historical continuity.

Simultaneously, the synergy between business diversity and policy orientation should be strategically emphasized to form a business ecosystem supporting sustainable development. Future commercial street designs should integrate digital media with the physical environment, taking into account how digital technology reshapes consumer behavior and the key role of visual narratives in shaping brand identity and marketing strategies.

Given the inspiration of Sussman et al.’s study [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39], in the next study, our team will try to introduce a measure of visual attention to explore the inter-relationship between environmental information and pedestrians’ visual perceptual experience in historic commercial pedestrian streets.