Analyzing the Evolution of a Rural Construction Community in China from the Perspective of Cultural Landscape

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Explanation of Core Concepts

1.1.1. Concept Explanation of Rural Construction Community

1.1.2. Perspective of Rural Construction Community

1.2. History and Background

1.3. Research Questions and Aims

2. Theory and Method

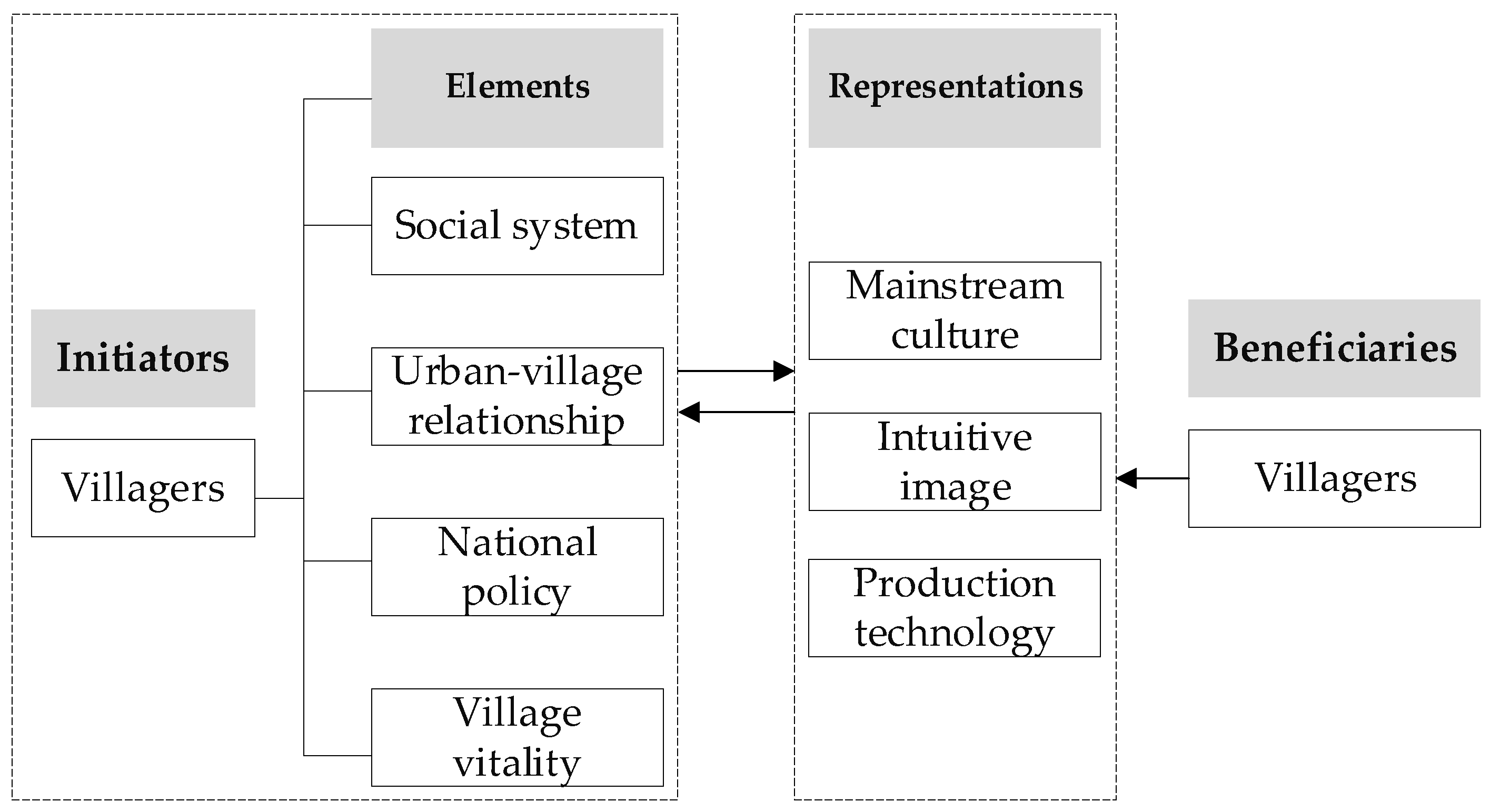

2.1. Formation Mechanism of Rural Construction Community

2.1.1. Literature Review

- (1)

- The social and cultural foundation of rural construction community

- (2)

- Sustainability, policy frameworks for rural area

2.1.2. Rural Community Construction Process and Village Activities

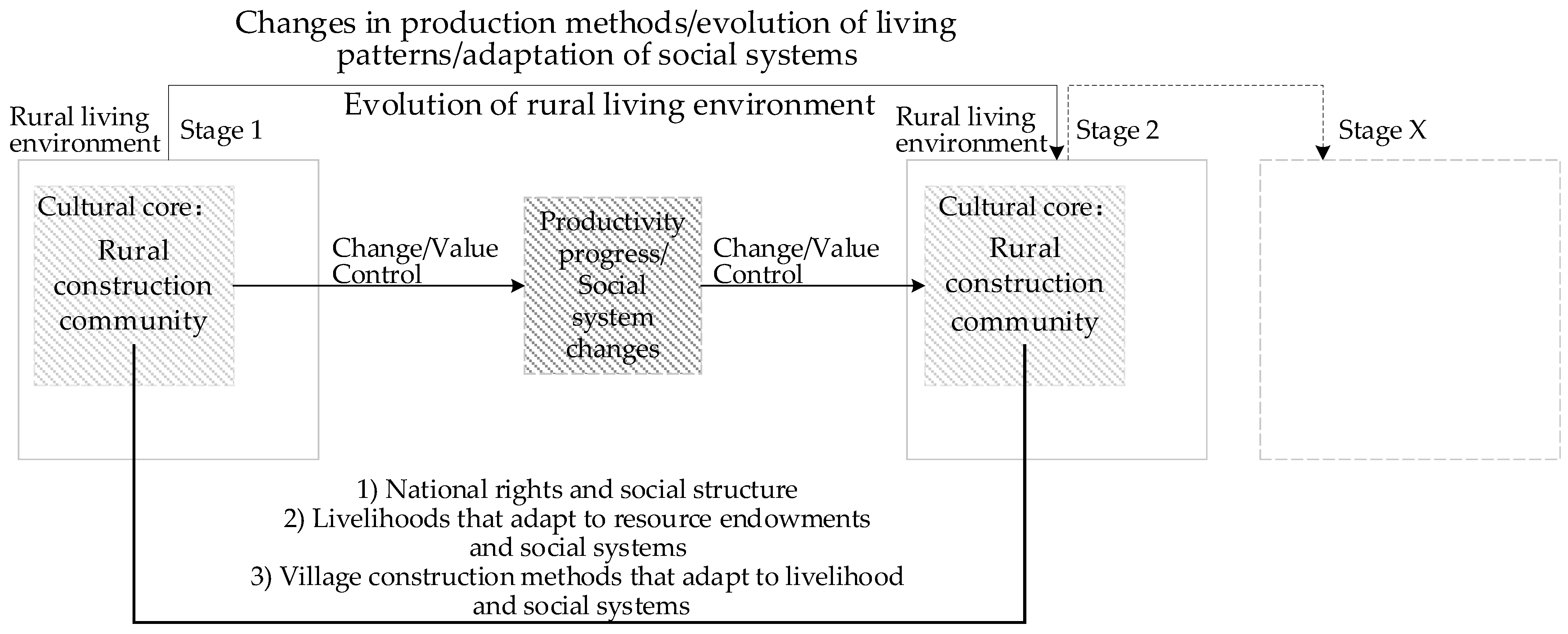

2.2. Different Stages in the Evolution of Rural Construction Community

2.3. Analysis Method and Steps

2.3.1. Evolution Process of Rural Construction Community

2.3.2. Analysis of the Coupling of ‘Ecology-Institution-Livelihood’ within the Rural Community Construction

2.3.3. Content Framework of This Article

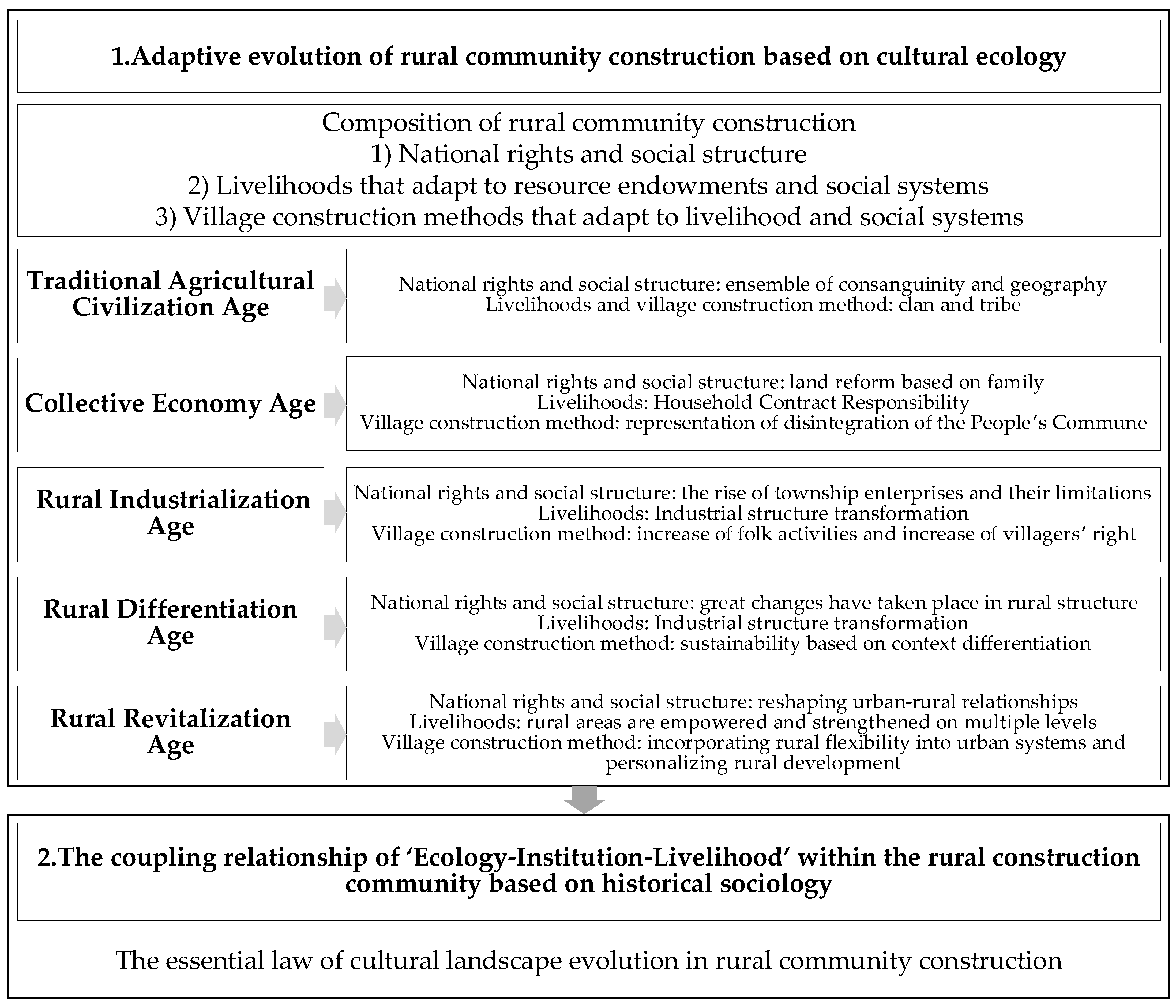

3. Adaptive Evolution of Rural Community Construction Based on Cultural Ecology

3.1. Traditional Agricultural Civilization Age: Before 1949

3.1.1. National Rights and Social Structure: Ensemble of Consanguinity and Geography

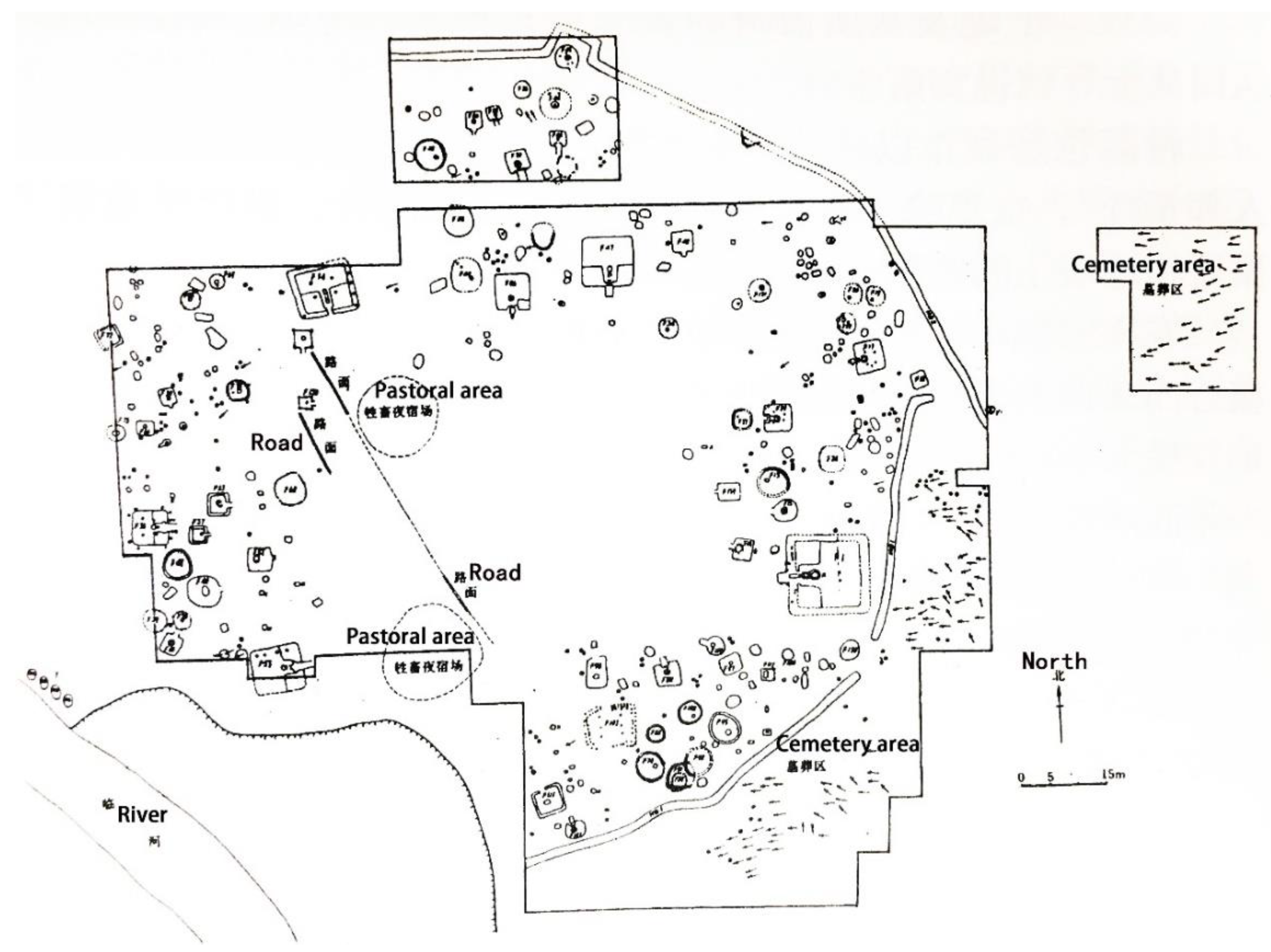

3.1.2. Livelihoods and Village Construction Method: Clan and Tribe

3.2. Collective Civilization Age: After the Land Reform in 1949–Around 1990

3.2.1. National Rights and Social Structure: Land Reform Anchored in Family

3.2.2. Livelihoods: Household Contract Responsibility

3.2.3. Village Construction Method: Manifestation of Disintegration of the People’s Commune

3.3. Rural Industrialization Age: 1990–2010

3.3.1. National Rights and Social Structure: Emergence and Constraints of Township Enterprises

3.3.2. Livelihoods: Industrial Structure Transformation

3.3.3. Village Construction Method: Rise in Folk Activities and Villagers’ Rights

3.4. Rural Differentiation Age: 2010–2017

3.4.1. National Rights and Social Structure: Profound Changes in Rural Dynamics

3.4.2. Livelihoods: Industrial Structure Transformation

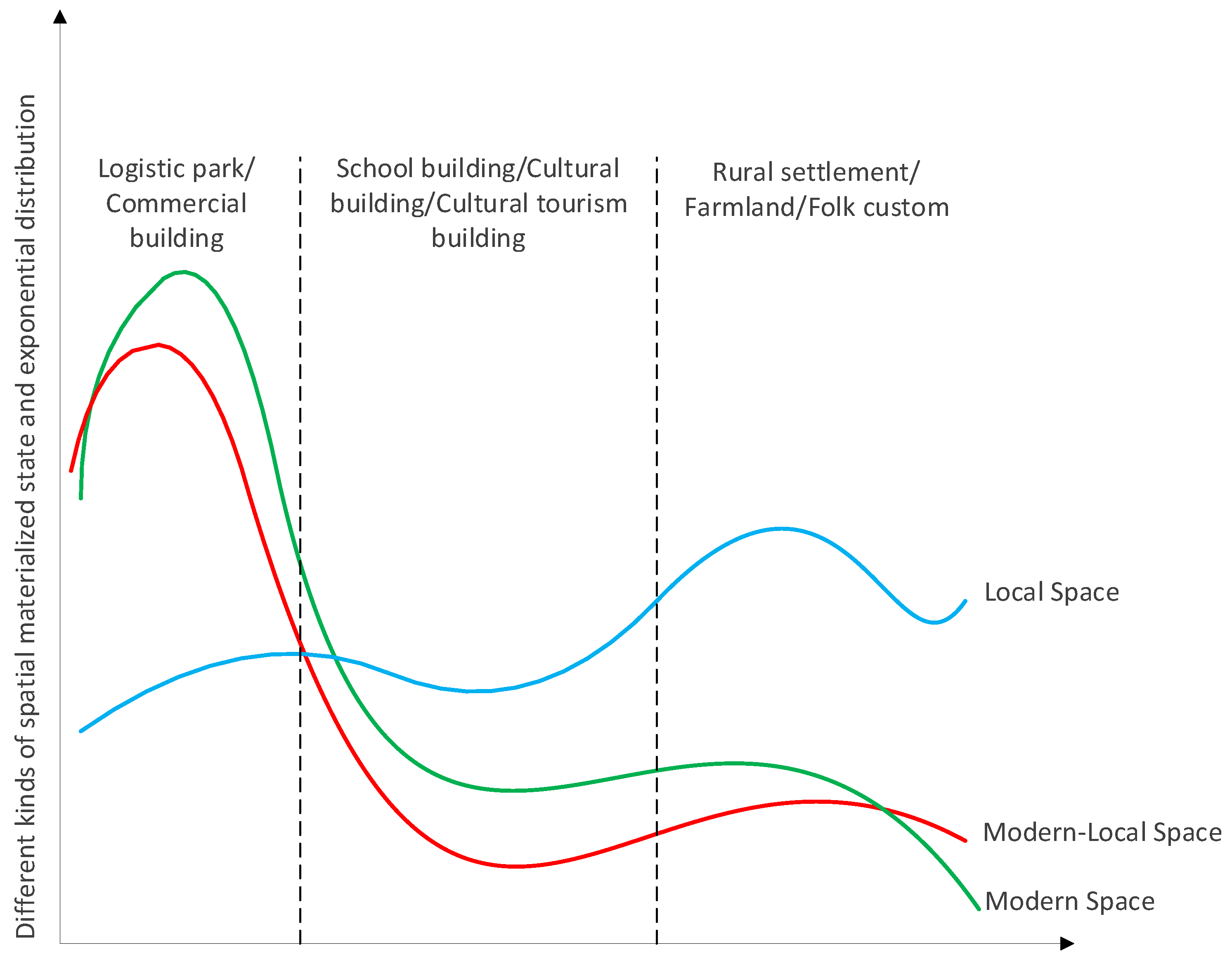

3.4.3. Village Construction Method: Emphasizing Sustainability through Contextual Differentiation

3.5. Rural Revitalization Age: After 2017

3.5.1. National Rights and Social Structure: Reshaping Urban–Rural Relationships

3.5.2. Livelihoods: Rural Areas Are Empowered and Strengthened on Multiple Levels

3.5.3. Village Construction Method: Incorporating Rural Flexibility into Urban Systems and Personalizing Rural Development

4. The Coupling Relationship of Ecology–Institution–Livelihood within the Rural Construction Community Based on Historical Sociology

4.1. The Process of Coupling Transformation

4.2. Comparison of Rural Cultural Landscape in 5 Stages

4.3. Who Holds the Primary Role in Rural Construction Development?

“In the survey conducted in She County, nearly every residential compound features a chrysanthemum dryer, despite the fact that these individual household straw-burning practices may fall short of meeting environmental standards (Figure 13). Chinese peasants inherently possess a dedication that compels them, even within legal constraints, to resourcefully manifest their aspirations. Although such construction practices are less prevalent in today’s rural China, they stand as evidence that the essence of rural society remains unaltered”—as quoted by the author.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.1.1. Forming an Interpretation of Rural Areas Based on Constructing a Community

5.1.2. Systematic Understanding of Rural Construction Community

5.1.3. Challenges and Limitations

5.2. Conclusions

5.2.1. The Element Composition and Evolutionary Changes in Village Construction

- (1)

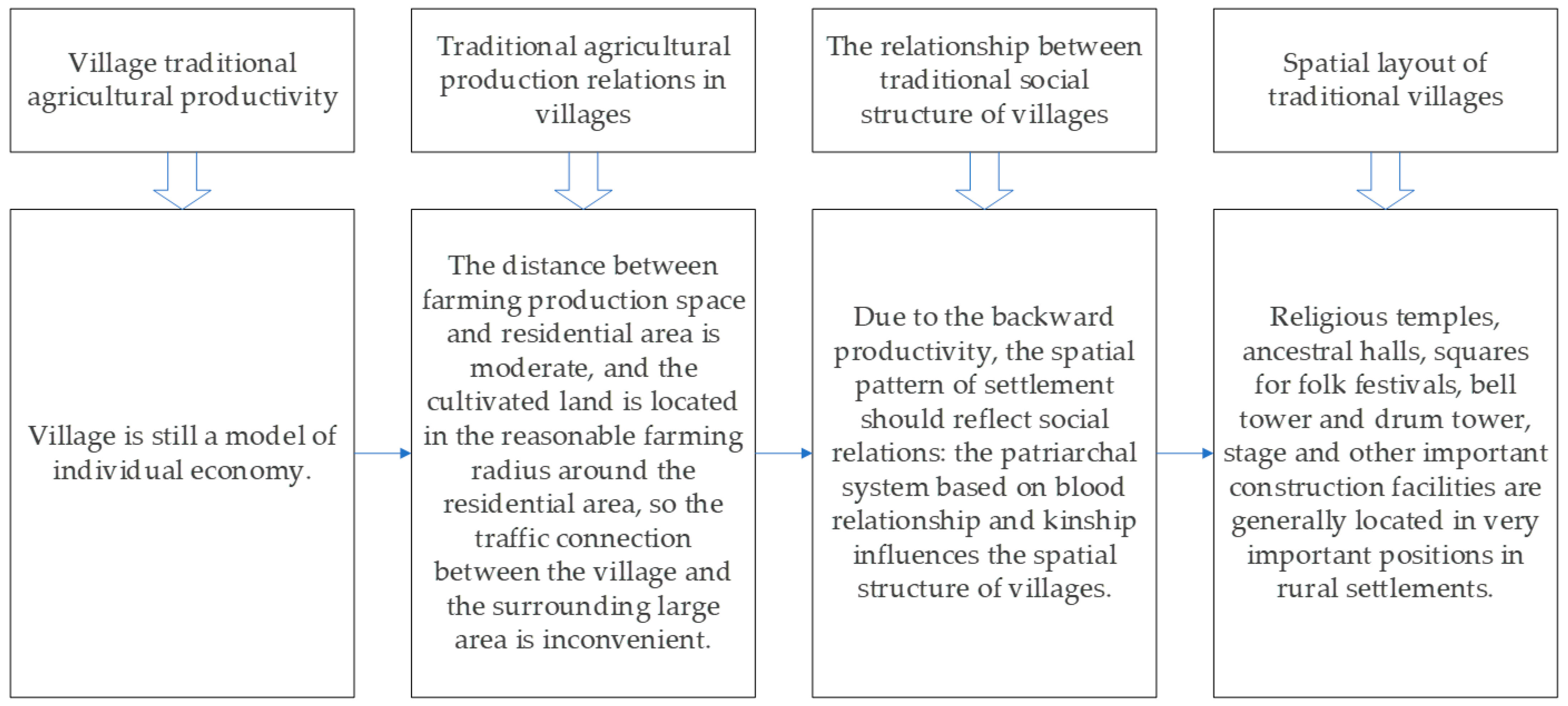

- Due to fundamental productivity limitations like transportation, villages during farming periods often find themselves constrained, primarily focusing on agricultural pursuits. Consequently, the arrangement and structure of villages reflect the features aligned with the traditional level of agricultural productivity: an inherent organic amalgamation of production and daily life, fostering a harmonious symbiotic relationship between humanity and the land (Figure 14).

- (2)

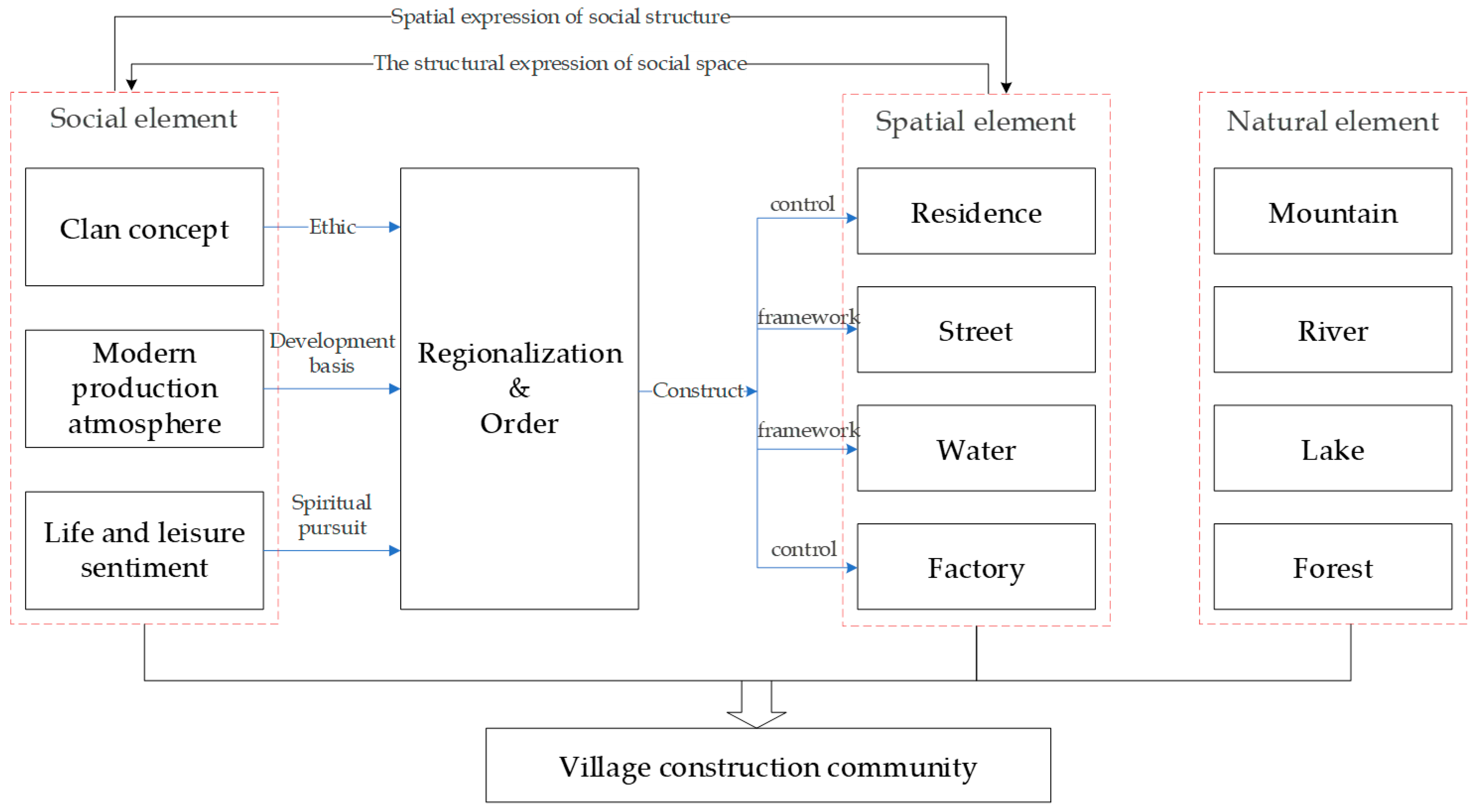

- Post-liberation, the construction of village communities signifies a fusion between natural elements and human intervention. During this phase, villages have notably distanced themselves from their reliance solely on land, diverging from the traditional agricultural village development trajectory. Presently, village construction and advancement predominantly hinge upon commercial gains. Consequently, villages exhibit a blend of characteristics, encompassing ancient patriarchal clan concepts, a modern production ambiance, as well as sentiments pertaining to life and leisure. The spatial components within a production-oriented village community directly influence and are influenced by the operation of social relations, significantly impacting the fabric of social dynamics. Elements such as residences, thoroughfares, water systems, ancestral halls, and workshops within the village community serve as conduits for expressing social relations, collectively constituting the elements that shape the socialized space within village community, thereby upholding rural social order.

- (3)

- Beyond 2017, while many villages encounter decline, certain rural construction communities exhibit increased resilience and adaptability. A resilient rural construction community embodies the concurrent presence of diverse stakeholders, functioning as carriers within the regional system space, thereby establishing a sustainable competitive framework. Specific functions gradually evolve toward specialization, generating synergy with other functions. This specialized advantageous function ultimately epitomizes the core competitiveness within the regional system. Within this developmental framework of competition and coexistence, the emphasis is not on alienation or detachment but rather signifies a village structure brimming with enhanced vitality (Table 4).

5.2.2. Considering the Rural Construction Community as an Unforeseen Entity

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; Qiao, L.; Wang, Q.; Dávid, K. Towards the evaluation of rural livability in China: Theoretical framework and empirical case study. Habitat Int. 2020, 105, 102241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Long, H.; Cui, W. Community-based rural residential land consolidation and allocation can help to revitalize hollowed villages in traditional agricultural areas of China: Evidence from Dancheng County, Henan Province. Land Use Policy 2014, 39, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Introduction to land use and rural sustainability in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hu, Y. Finding Community Structure and Evaluating Hub Road Section in Urban Traffic Network. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 96, 1494–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barraket, J.; Eversole, R.; Luke, B.; Barth, S. Resourcefulness of locally-oriented social enterprises: Implications for rural community development. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 70, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, A.; Atterton, J. Exploring the contribution of rural enterprises to local resilience. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 40, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Avtar, R.; Raj, R.; Minh, H.V.T. Village Level Provisioning Ecosystem Services and Their Values to Local Communities in the Peri-Urban Areas of Manila, The Philippines. Land 2019, 8, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primdahl, J.; Eetvelde, V.V.; Pinto-Correia, T. Rural Landscapes—Challenges and Solutions to Landscape Governance. Land 2020, 9, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, S.-L. Peasant Life in China; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, D. “Community Justice”, Ancestral Rights, and Lynching in Rural Bolivia; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kumpulainen, K.; Soini, K. How Do Community Development Activities Affect the Construction of Rural Places? A Case Study from Finland. Sociol Rural. 2019, 59, 294–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahraki, S.Z.; Hosseini, A.; Sauri, D.; Hussaini, F. Fringe more than context: Perceived quality of life in informal settlements in a developing country: The case of Kabul, Afghanistan. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 63, 102494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shucksmith, M. Disintegrated Rural Development? Neo-endogenous Rural Development, Planning and Place-Shaping in Diffused Power Contexts. Sociol Rural. 2010, 50, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasstrøm, M.; Normann, R. The role of local government in rural communities: Culture-based development strategies. Local Gov. Stud. 2019, 45, 848–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinnie, E.; Fischer, A. The Trouble with Community: How ‘Sense of Community’ Influences Participation in Formal, Community-Led Organisations and Rural Governance; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sabet, N.S.; Khaksar, S. The performance of local government, social capital and participation of villagers in sustainable rural development. Soc. Sci. J. 2020, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, J.H. Theory of Culture Change; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E. The Division of Labor in Society (1893); Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 37–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tada, M. Language and imagined Gesellschaft: Mile Durkheim’s civil-linguistic nationalism and the consequences of universal human ideals. Theory Soc. 2020, 49, 597–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffel, V. A History of Civilizations; Penguin Pr.: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ratzel, F.; Stehlin, S.A. Sketches of Urban and Cultural Life in North America; Rutgers University Press: New Beunswick, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Font, C.; Padró, R.; Cattaneo, C.; Marull, J.; Farré, M. How farmers shape cultural landscapes. Dealing with information in farm systems (Vallès County, Catalonia, 1860). Ecol. Indic. 2020, 112, 106104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cháirez-Garza, J.F. BR Ambedkar, Franz Boas and the Rejection of Racial Theories of Untouchability. South Asia J. South Asian Stud. 2018, 41, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfield, R. Peasant society and culture: An anthropological approach to civilization. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1956, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Frankfurter, D. The Great, the Little, and the Authoritative Tradition in Magic of the Ancient World. Archiv. Relig. 2015, 16, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radcliffe-Brown, A.R.; Kuper, A. The Social Anthropology of Radcliffe-Brown; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kvartiuk, V.; Curtiss, J. Participatory rural development without participation: Insights from Ukraine. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 69, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.; Stedman, R.C. Understanding Local Environmental Concern: The Importance of Place: Local Environmental Concern and Place. Rural Sociol. 2018, 84, 93–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Qin, S.; Nisar, N.; Zhang, Q.; Tong, T.; Wang, L. Does rural industrial integration improve agricultural productivity? Implications for sustainable food production. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1191024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Razzaq, A.; Qin, J.; Feng, Z.; Ye, F.; Xiao, M. Does the Expansion of Farmers’ Operation Scale Improve the Efficiency of Agricultural Production in China? Implications for Environmental Sustainability. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 918060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpar, H.; Zhang, A.; Razzaq, A.; Mehmood, K.; Pirzado, M.B.; Hu, W. Agricultural Land Abandonment and Farmers’ Perceptions of Land Use Change in the Indus Plains of Pakistan: A Case Study of Sindh Province. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Riper, C.J.; Foelske, L.; Kuwayama, S.D.; Keller, R.; Johnson, D. Understanding the role of local knowledge in the spatial dynamics of social values expressed by stakeholders. Appl. Geogr. 2020, 123, 102279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duara, P. Sovereignty and Authenticity; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Akbari, M.; Bahrami-Rad, D.; Kimbrough, E.O. Kinship, fractionalization and corruption. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2019, 166, 493–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chen, M.; Zhou, L.; Liang, X.; Wang, W. Identifying the Spatiotemporal Patterns of Traditional Villages in China: A Multiscale Perspective. Land 2020, 9, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Pu, F. Spatial Cognitive Modeling of the Site Selection for Traditional Rural Settlements: A Case Study of Kengzi Village, Southern China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 5020026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, W. Assessing the impact of population, income and technology on energy consumption and industrial pollutant emissions in China. Appl. Energy 2015, 155, 904–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Structure and Change in Economic History; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.L.H. Spatial distribution characteristics and optimized reconstruction analysis of China’s rural settlements during the process of rapid urbanization. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Du, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X. Effect Mechanisms of Peasant Relocation Decision-making Behaviours in the Process of Rural Spatial Restructuring: The case of Hotan region, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 63, 102429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, P. Rural Land Use Change Driven by Informal Industrialization: Evidence from Fengzhuang Village in China. Land 2020, 9, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Institutional interaction and decision making in China’s rural development. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 76, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xiong, X. China’s rural institutions and governance since the beginning of the rural reform. China Econ. J. 2018, 11, 259–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh-Dilley, M. Religious Fragmentation, Social Disintegration? Social Networks and Evangelical Protestantism in Rural Andean Bolivia. Qual. Sociol. 2019, 42, 499–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Hu, Y. Emotional Labour in a Translocal Context: Rural Migrant Workers in China’s Service Sector. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2020, 23, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Song, Y. Unraveling land system vulnerability to rapid urbanization: An indicator-based vulnerability assessment for Wuhan, China. Environ. Res. 2022, 211, 112981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisaga, I.; Parikh, P.; Loggia, C. Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Urban Farming in South African Low-Income Settlements: A Case Study in Durban. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, E.; Brown, D. ‘It’s the sea and the beach more than anything for me’: Local surfer’s and the construction of community and communitas in a rural Cornish seaside village. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 59, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ka-Yin, L.A.; Anthony, A.R. Naturalizing people, ethnicizing landscape: Promoting tourism in China’s rural periphery. Asian Geogr. 2018, 35, 177–196. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, S.; Heijman, W.; Zhu, X.; Qiao, D.; Lu, Q. Income Groups, Social Capital, and Collective Action on Small-Scale Irrigation Facilities: A Multigroup Analysis Based on a Structural Equation Model. Rural Sociol. 2016, 83, 882–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, R. Local history as productive nostalgia? Change, continuity and sense of place in rural England. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2016, 18, 466–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R. Rural Development; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

| Migration Mode | Households | Number of Left-Behind Elderly Households | Number of Elderly Households Moving with Their Children |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Flow | 83 (68.6%) | 83 | 0 |

| Family Flow | 26 (21.5%) | 26 | 0 |

| Family Migration | 12 (9.9%) | 7 | 5 |

| Evaluation Factor | Rural | Urban |

|---|---|---|

| Type of productivity | Unification (regional short-term economic behavior) | Diversification (long-term economic activity) |

| The industrial structure | Single/messy/basically zero | System/maturity |

| Cultural resources | Primitive ecology/facing capital plunder | Industrialization/active variation |

| Independence | Easily siphoned by the city | Relatively independent |

| Ecological resources | Ecologically sensitive and fragile | Relatively high bearing capacity |

| Welfare rights | Negative benefits | Positive benefits |

| Comparison Factors | Traditional Civilization Age | Collective Civilization Age | Rural Industrialization Age | Rural Differentiation Age | Rural Revitalization Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formation process | Social system | Primitive society and feudal society | Socialist system | Socialist system | Socialist system | Socialist system |

| Urban–village relationship | Agrarian society with no cities | Urban–rural dual system | Urban–rural integration | Post-urban–rural integration | Urban–rural integration | |

| National policy | Small-scale peasant economy | Planned economic system, give priority to cities | Market economy, Partial rural industrialization | Market economy, urban and rural equality | Market economy, rural revitalization | |

| Village vitality | High | High | High to low | Low/high | Low to high | |

| Sustainable representations | Village image | Unified local style | Unified local style | Modern style begins to appear | Style alienation | Mixture of modern and native |

| Village activities | Various life and production activities for locals | Various life and production activities for locals | Invasion of urban functions | The decline in rural areas and the sharp decrease in rural activities | Differentiated development and planning | |

| Index Layer | Village Construction Community in the Past | Flexible Village Construction Community in the New Era |

|---|---|---|

| Development goals of villages | Pursuing agglomeration development and scale economy | Pursuing the comprehensive development and functional development scope of villages and towns |

| Structure of villages | Vertical structure: the leading and supporting relationship between leading role and others | Parallel relationship: the dominant functions are parallel and cooperative with other functions, and multiple functions are symbiotic and have flexible cooperative relationship |

| The connotation of village and town construction community | Dominant industry/material characteristics | Implicit experience/structural features |

| Driving force of development | From top to bottom, government intervention | From bottom to top, market driven |

| The main body composition of community | The subjects show subordination, less competition and cooperation | There are two kinds of relations between different subjects: competition and coordination |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ren, K.; Wu, T. Analyzing the Evolution of a Rural Construction Community in China from the Perspective of Cultural Landscape. Buildings 2024, 14, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14010097

Ren K, Wu T. Analyzing the Evolution of a Rural Construction Community in China from the Perspective of Cultural Landscape. Buildings. 2024; 14(1):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14010097

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Kai, and Tiehong Wu. 2024. "Analyzing the Evolution of a Rural Construction Community in China from the Perspective of Cultural Landscape" Buildings 14, no. 1: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14010097

APA StyleRen, K., & Wu, T. (2024). Analyzing the Evolution of a Rural Construction Community in China from the Perspective of Cultural Landscape. Buildings, 14(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14010097