Fluid Grey: A Co-Living Design for Young and Old Based on the Fluidity of Grey Space Hierarchies to Retain Regional Spatial Characteristics

Abstract

1. Introduction

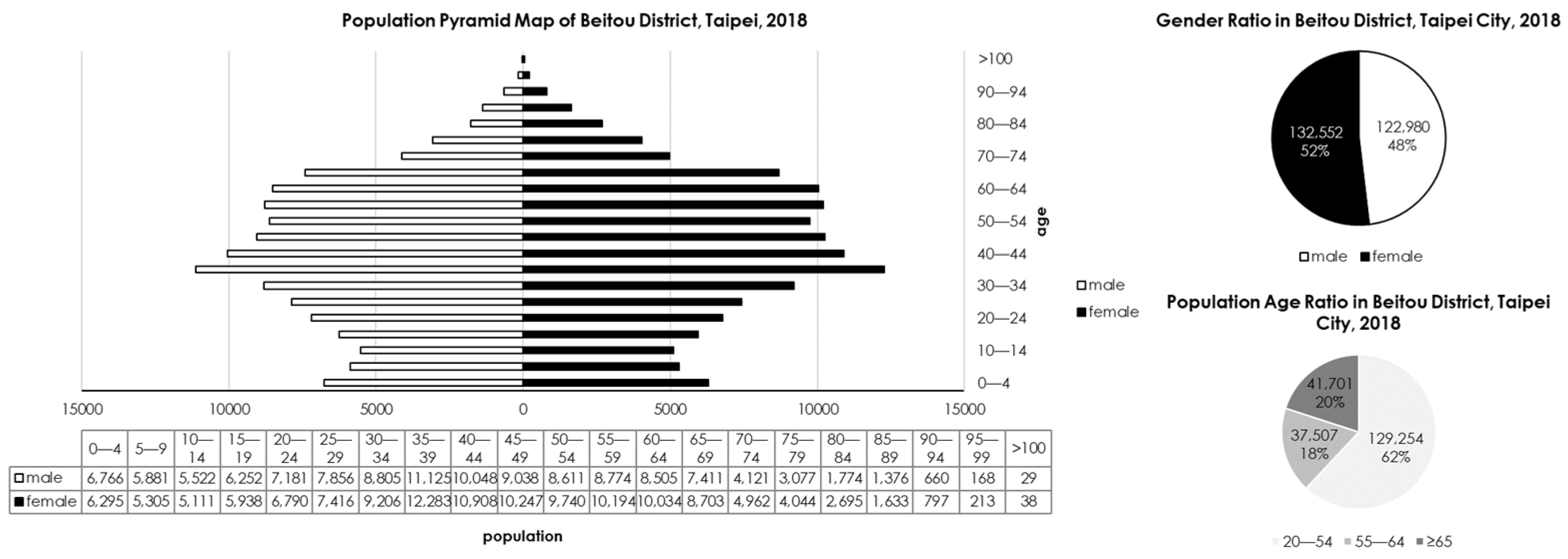

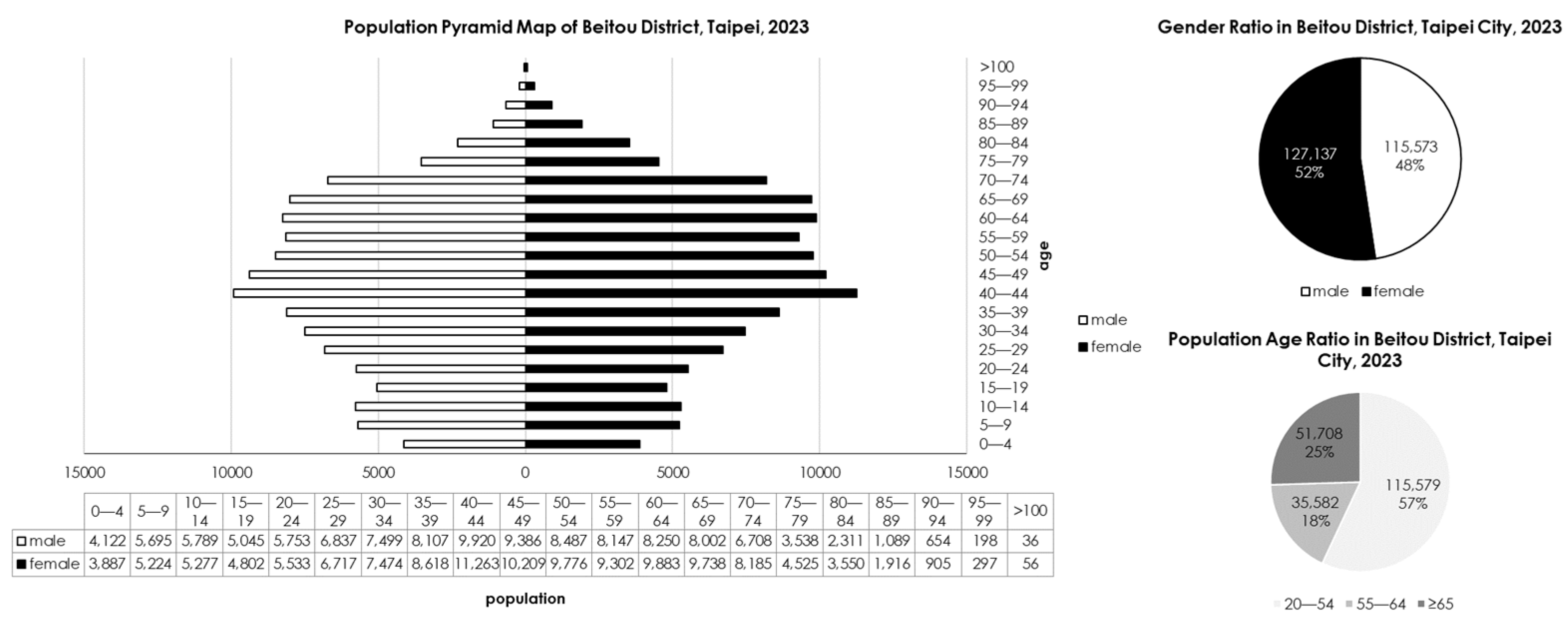

1.1. Background Analysis of Ageing Society and Social Housing

1.2. Grey Space Theory

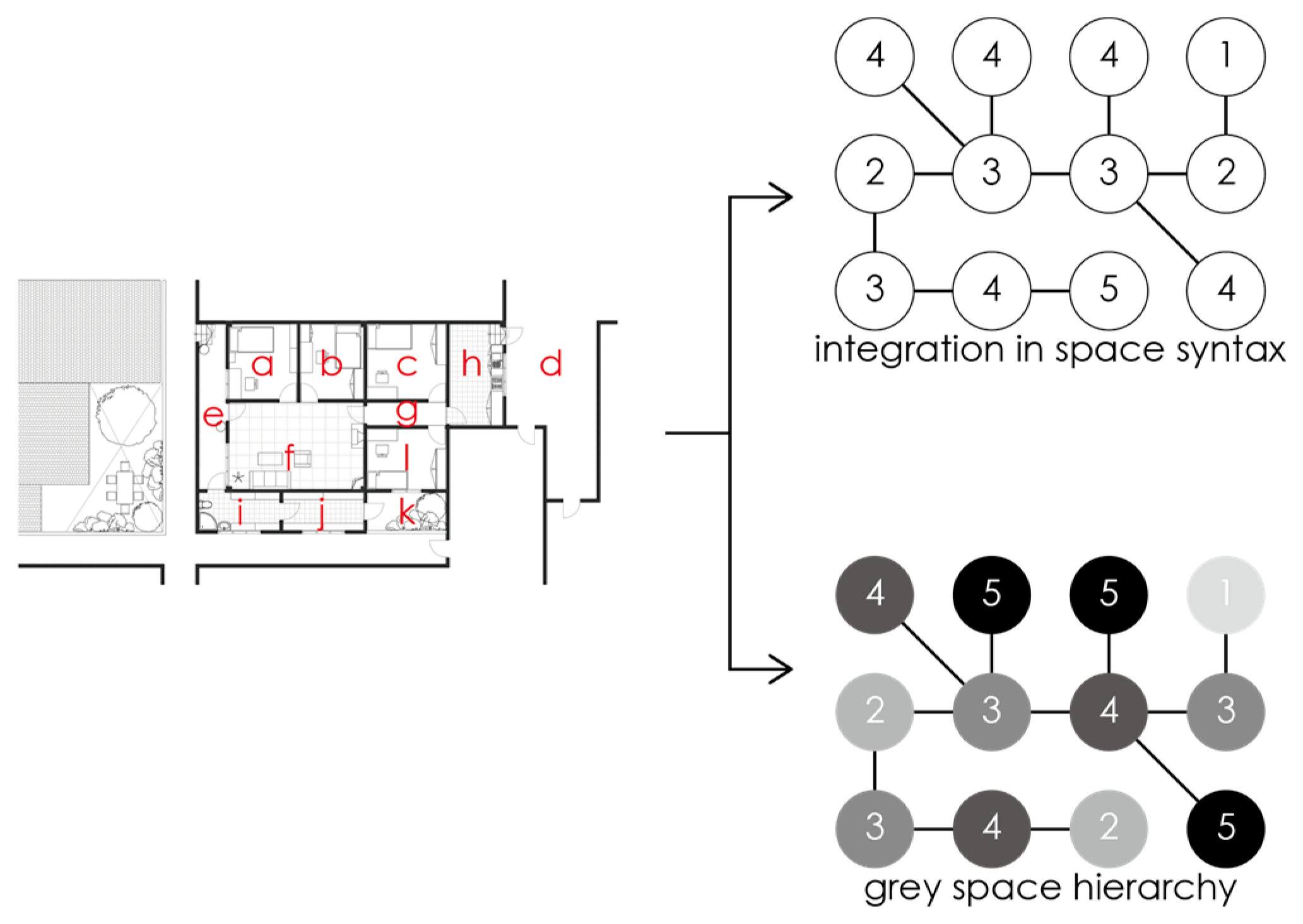

1.2.1. Grey Space Hierarchy

1.2.2. Fluidity of Grey Space

1.2.3. Grey Space and Regional Characteristics

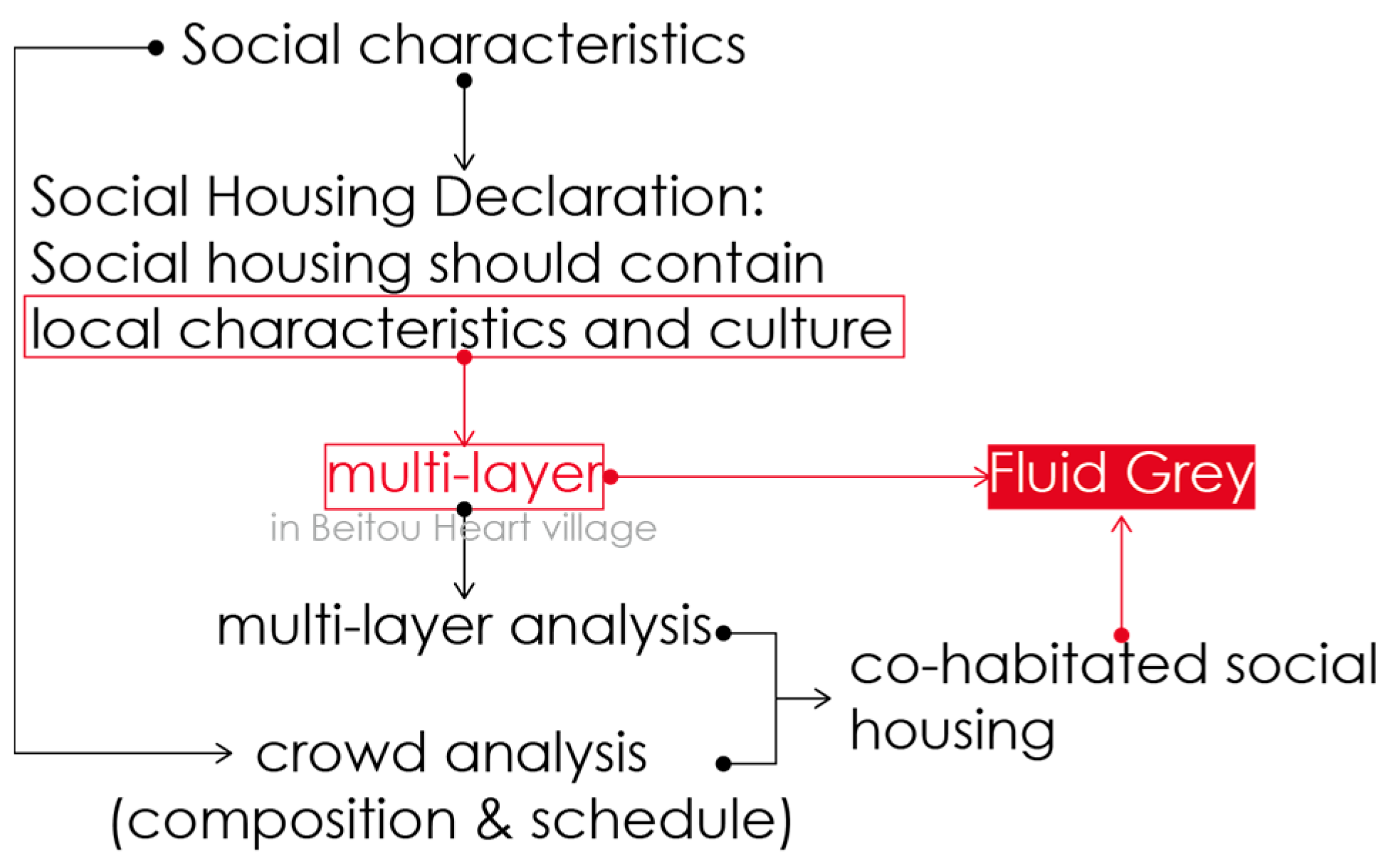

2. Materials and Methods

- (1)

- Grey Space Hierarchy, Fluidity, and Connection with Regional Characteristics: Based on the theories and practices of grey space, fluidity, and localization in the history of architecture, we qualitatively analyze and define the concept and division method of grey space hierarchy;

- (2)

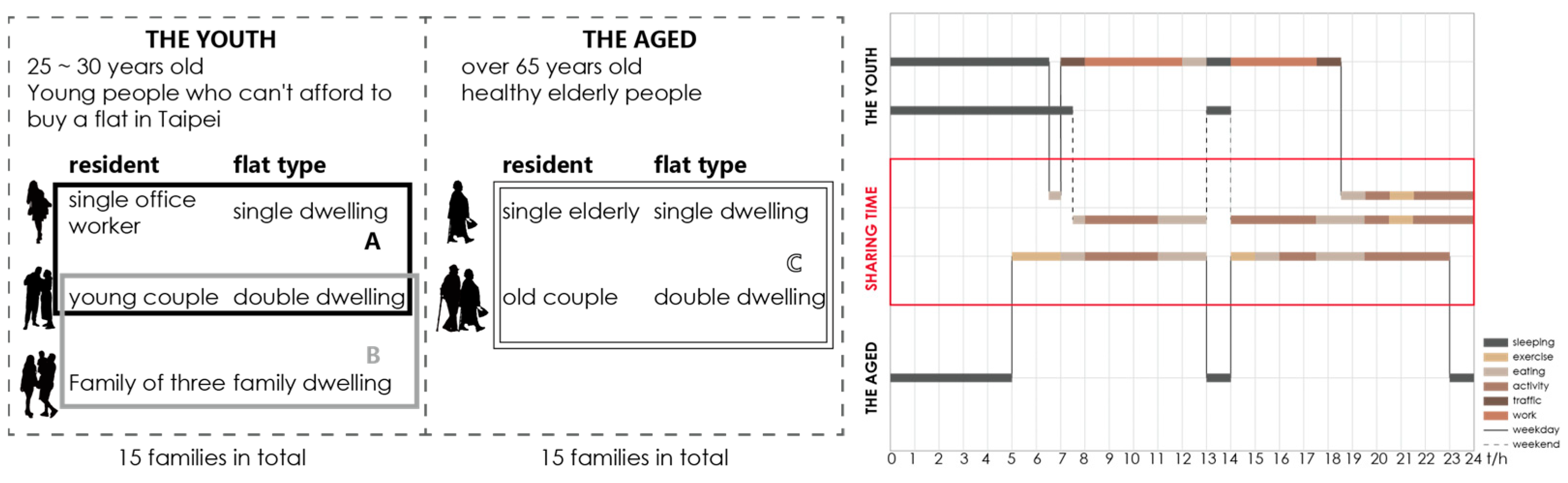

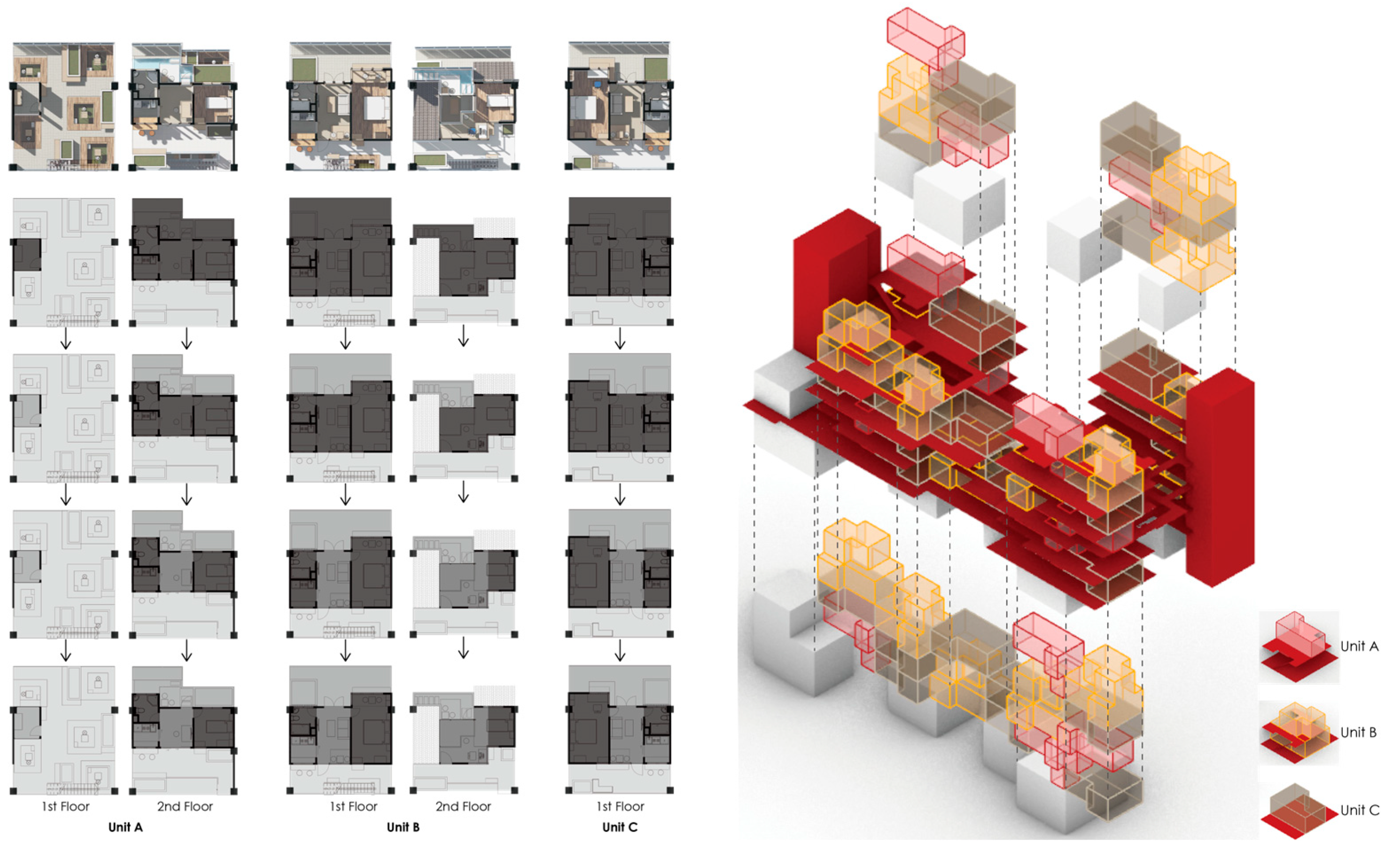

- Design Application: Summarizing the grey space hierarchy and fluidity of Beitou Heart Village, we analyze the population composition of Beitou District and design residential units and social housing in a bottom-up process, so that the fluidity of grey space has scalability.

2.1. Grey Space Hierarchy, Fluidity and Connection with Regional Characteristics

2.2. Design Application

3. Results

3.1. Grey Space Hierarchy, Fluidity and Connection with Regional Characteristics

3.2. Design Application

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- World Health Organization. Health at a Glance: Asia/Pacific 2022 Measuring Progress towards Universal Health Coverage: Measuring Progress towards Universal Health Coverage; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- National Development Council. Aging. 2023. Available online: https://www.ndc.gov.tw/Content_List.aspx?n=2688C8F5935982DC (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Li, Y. Six Cities and Counties in Taiwan Have Entered a Super-Aged Society, with People Aged 65 and above Accounting for 20% of the Total Population. Public Television Service News Network. 2024. Available online: https://news.pts.org.tw/article/683774 (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Global Views Research. 2017 Survey on the Transformation Power of Chinese Youth in Four Regions. 2017. Available online: https://gvsrc.cwgv.com.tw/articles/index/14767/9 (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Zheng, L.; Li, Q. Living conditions and institutional care needs of the elderly in Taiwan. Land Public Gov. Q. 2019, 7, 70–81. Available online: https://www.airitilibrary.com/Article/Detail/P20150327001-201903-201903190019-201903190019-70-81 (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Department of Statistics, Ministry of Health and Welfare. Report of the Senior Citizen Condition Survey 2022. 2024. Available online: https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/lp-5095-113.html (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Taipei City Government. Housing Justice 2.0.; Department of Land Administration, Taipei City Government: Taipei City, Taiwan, 2019. Available online: https://epaper.land.gov.taipei/Book/upload/637135760529919424/index.html (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Wang, S.; Yang, S. Research on the Integration of Social Housing and Symbiotic Community Care Space Environment; Architecture and Building Research Institute, Ministry of the Interior, R.O.C. (TAIWAN): Taipei City, Taiwan, 2022. Available online: https://www.abri.gov.tw/News_Content_Table.aspx?n=807&s=277502 (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Executive Yuan. Ethnic Group. 2024. Available online: https://www.ey.gov.tw/state/99B2E89521FC31E1/2820610c-e97f-4d33-aa1e-e7b15222e45a (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Li, R. Research on the Renewal of Military Villages in Taiwan in Conjunction with Urban Development; Taiwan Institute of Urban Planning: Taipei City, Taiwan, 1988; Available online: https://tm.ncl.edu.tw/article?u=022_109_000065 (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Beitou Heart Village. Available online: https://www.beitouheartvillage.taipei (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Kurokawa, K. The Philosophy of Symbiosis; Academy Editions: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Trancik, R. Finding Lost Space: Theories of Urban Design; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rites of Zhou·Kao Gong Ji·Craftsman. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaogongji#cite_note-pare-1 (accessed on 13 May 2024).

- Verstegen, I.; Ceen, A. (Eds.) Giambattista Nolli and Rome: Mapping the City before and after the Pianta Grande; Studium Urbis: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sitte, C. The Art of Building Cities: City Building According to Its Artistic Fundamentals; Ravenio Books: Dublin, Ireland, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.; Venturi, I.; Izenour, S. Learning from Las Vegas; Art, Architecture and Engineering Library: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, O. Defensible Space: Crime Prevention through Urban Design; Collier Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, C.; Koetter, F. Collage City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.J. The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception: Classic Edition; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett, R. The Uses of Disorder; Vintage: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, G. Foucault; Folds; Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House: Amersham, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, G. The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque; U of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, G. Folds, Bodies & Blobs: Collected Essays; La Lettre volée: Uccle, Belgium, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, G. (Ed.) Folding in Architecture; Academy Editions: London, UK, 1993; Volume 102. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett, R.; Sendra, P. Designing Disorder: Experiments and Disruptions in the City; Verso Books: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzberger, H. Lessons for Students in Architecture; 010 Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, S. Field conditions. Archit. Des. 1996, 66, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Dovey, K.; Pafka, E. What is walkability? The urban DMA. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D. (Ed.) History of Ancient Chinese Architecture; China Architecture Industry Press: Beijing, China, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sekino, T. Essentials of Japanese Architectural History; Tongji University Press: Shanghai, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, R. Emerging Urbanity: Global Urban Projects in the Asia Pacific Rim; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maki, F. The city and inner space. Ekistics 1979, 46, 328–334. [Google Scholar]

- Maki, F. Nurturing Dreams: Collected Essays on Architecture and the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kosinski, J. Passing by: Selected Essays, 1962–1991; Grove Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Van Nes, A.; Yamu, C. Introduction to Space Syntax in Urban Studies; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; p. 250. [Google Scholar]

- Tzonis, A.; Lefaivre, L. The grid and the pathway. In Times of Creative Destruction; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, K. Toward a critical regionalism: Six points for an architecture of resistance. In Postmodernism; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016; pp. 268–280. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon, E.N. Design of Cities: Revised Edition; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1976; pp. 85–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hilberseimer, L. Groszstadt Architektur; Hoffmann: Reading, PA, USA, 1978; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B. Specifically architectural theory: A partial account of the ascent from building as cultural transmission to architecture as theoretical concretion. Harv. Archit. Rev. 1993, 9, 8–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B. Space Is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture; Space Syntax: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Urban Development, Taipei City Government. Application for Taipei City Topographic Map Digital File. Taipei City Government Citizen Service Platform. Available online: https://service.gov.taipei/Case/ApplyWay/201907250045 (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Household Registration Offices. Population Pyramid of the District; Household Registration Offices: Taipei City, Taiwan, 2019. Available online: https://bthr.gov.taipei/News.aspx?n=01EB2EE6FD368FA9&sms=0E6E4C19DA8B3727 (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Turhan, C.; Özbey, M.F.; Çeter, A.E.; Akkurt, G.G. A novel data-driven model for the effect of mood state on thermal sensation. Buildings 2023, 13, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiao, F.; Li, A.; Ma, T.; Xu, K.; Zhang, H.; Yan, R.; Fang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, D. Graph neural network-based spatio-temporal indoor environment prediction and optimal control for central air-conditioning systems. Build. Environ. 2023, 242, 110600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderzhon, J.W.; Hughes, D.; Judd, S.; Kiyota, E.; Wijnties, M. Design for Aging: International Case Studies of Building and Program; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Demirkan, H. Housing for the aging population. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2007, 4, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qiu, Y.; Lai, I.-C. Fluid Grey: A Co-Living Design for Young and Old Based on the Fluidity of Grey Space Hierarchies to Retain Regional Spatial Characteristics. Buildings 2024, 14, 2042. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14072042

Qiu Y, Lai I-C. Fluid Grey: A Co-Living Design for Young and Old Based on the Fluidity of Grey Space Hierarchies to Retain Regional Spatial Characteristics. Buildings. 2024; 14(7):2042. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14072042

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiu, Yayan, and Ih-Cheng Lai. 2024. "Fluid Grey: A Co-Living Design for Young and Old Based on the Fluidity of Grey Space Hierarchies to Retain Regional Spatial Characteristics" Buildings 14, no. 7: 2042. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14072042

APA StyleQiu, Y., & Lai, I.-C. (2024). Fluid Grey: A Co-Living Design for Young and Old Based on the Fluidity of Grey Space Hierarchies to Retain Regional Spatial Characteristics. Buildings, 14(7), 2042. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14072042