Abstract

A well-designed learning environment is crucial for enhancing both the physical and mental health of students, which in turn improves their learning outcomes. However, many classrooms in China, particularly in rural areas, were constructed and designed several decades ago, so it is essential to redesign these learning spaces to align with the requirements of 21st Century education. This study aims to develop the stimulation, individuality, and naturalness (SIN) theoretical framework for identifying the learning environment of current classroom by examining the full range of sensory effects experienced by individuals. This study conducted qualitative interviews with 72 students and 18 class teachers to explore major issues with their existing learning spaces in four primary schools in Shandong Province of China. The results show that high temperatures and poor air quality are frequently raised by respondents, which directly impact students’ learning experience. This finding confirms naturalness likely underpins human comfort. Teachers and students felt that the classroom should be improved from the aspects of crowded space, imperceptible decoration, congestion and monotonous layouts. The study emphasised the important factors that designers and policymakers should consider to promote a comfortable, efficient, and healthy learning environment.

1. Introduction

Incorporating user assessments into the design process could enhance the outcomes of teaching. The perspectives of users influence the practical use of teaching spaces, thereby contributing to improvements in school atmosphere. In turn, teachers and students can advocate a pedagogical imperative to establish learning environments that enhance students’ comprehension [1]. Since students spend most of their time in learning spaces, particularly classrooms at school, obtaining their opinions would provide significant insights into their vulnerability and mental adaptability [2,3]. The school physical environment has a significant impact on students’ health, well-being, and academic performance. First, it is crucial that the fundamental natural environmental components are maintained within reasonable limits, as human bodies react instinctively to the presence of natural and healthful materials in their surroundings. Secondly, individualisation refers to how the needs of specific groups of students are satisfied in the classroom. Cultivating a sense of ownership among students is facilitated when they feel a connection to their classroom environment [4]. Third, the level of excitement and vibrancy in the classroom relates to the stimulation principle, which includes two parameters: colour and complexity. For example, room colour affects physiology and emotions, potentially leading to mood swings that might affect productivity [5]. Different spatial characteristics and elements influence students’ learning behaviours, enhancing learning diversity and interest while involving the educational attributes of teaching space. By positively affecting students’ emotions, these elements promote learning and cultivate a strong emotional connection between teachers and students [6]. Pedagogical frameworks [7,8,9] influence teaching and learning practices, activities, and behaviours rather than simply serving as containers for learning activities [10]. In Finland, Niemi et al. [11] found that active classroom designs significantly enhance student performance and engagement in learning.

In England, Cardellino and Woolner [12] investigated a case of an open school that solved the particular noise problem through the participation of users in the design process. This is a common issue met by open schools in Australia [13] and New Zealand [14] as well. However, some stakeholders feel that incorporating user participation and experience in the design practice is a waste of time [15]. Additionally, there is a contradiction between the real practice of stakeholder involvement and the rhetoric of inclusion [16]. In fact, an uncomfortable classroom can cause numerous disciplinary issues and negatively impact learning effectiveness [17]. Neglecting student input leads to several issues, such as overcrowded spaces [18,19], the operation of large classes, declining space quality [20] and reduced activity space, all of which impact teaching quality and the physical and mental health of students [18,21]. Classroom elements such as noise, lighting, poor air quality, temperature [22], uncomfortable furniture [23], colour and decoration [24] can overwhelm young children’s developing ability to maintain task goals and resist distractions, making it extremely challenging to stay focused in these environments [25]. Many studies focus on indoor environmental quality (IEQ) [22], layout [22], furniture [23] and colour [24,26,27], as well as their impact on student engagement, attention and learning performance. However, the integration of these elements in the design of school physical environments has been relatively limited in previous studies, particularly regarding students’ perceptions and emotions. Although user participation is important in design practice, their perspectives and opinions have been under-represented in classroom design practices, particularly in China.

The research findings on the school physical environment are summarised in Table 1 [28,29,30], highlighting the physical elements of space that affect user reaction. Major school physical design principles include naturalness, individuality, and stimulation, as listed in Table 1. Pressly and Heesacker [31] and Evans and McCoy [32] conducted research on interior design elements and their impact on human health, identifying spatial physical design attributes that meet basic user needs [31,32]. These principles can also be applied to other places, such as community housing for the elderly [33]. Promoting a higher level of human-centered design in the classroom involves considering learning space design to enhance learning and meet user needs. While many researchers have systematically examined specific aspects of the school environment and their effects on performance [34,35], limited attempts have been made to synthesize and summarize this accumulated evidence coherently. The relationship between users’ needs and learning spaces remains unclear, with many unanswered questions [36]. There appears to be no single study devoted to understanding the impacts of different features of school buildings, such as architectural design, aesthetic qualities, spatial and physical features, interior layout and furniture, and external spaces, on users, including patterns of learning outcomes, needs, preferences, expectations, emotions, and behaviours.

Table 1.

Summary of main design elements.

In China, the Ministry of Education (MOE) released the “Modernisation of Chinese Education 2035” and the “Education Blue Book: China’s Education Development Report (2020)” in 2020. These documents outlined the post-2020 goal to improve the effective utilisation of educational resources and improve education quality. By 2035, the aim is to achieve the comprehensive modernisation of education and establish a modern education system nationwide. Schools strengthen students’ practical, cooperation, and innovation abilities, clarify core quality requirements for student development, and establish innovative approaches to talent training. They seek to cultivate students’ innovative spirit and practical skills through heuristic, exploratory, participatory, and cooperative teaching methods, as well as through flexible teaching organization models like class systems and elective systems [62]. However, the school design in China remains traditional [21], which limits the development of new skills and innovative talent among students [10,11,23].

This study aims to develop the stimulation, individualisation, and naturalness (SIN) model to offer a contextualised and comparative perspective on users’ experiences in different school physical environment in China. It addresses two research questions: (1) What are the key design factors in classroom design? (2) What are the practical challenges of current learning spaces, as perceived by users? This study covers crucial viewpoints that should be considered throughout the design phase. The developed guideline can be applied in other schools across China to improve classroom design, and assist designers in creating high-quality learning space that cater to 21st Century learning styles and users’ needs. Ultimately, this study provides supportive environments that facilitate effective learning.

2. Literature Review

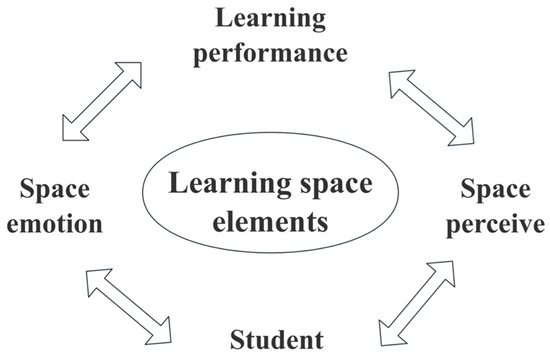

The design of classrooms impacts the learning of primary school students. Psychology, neuroscience, brain science, and environmental psychology researchers proved that primary school students’ perception of the spatial environment greatly impacts their cognitive development [63,64]. In the UK, multilevel modeling was utilised to separate the impact of physical design from the characteristics of 3766 students across 153 classrooms in 27 primary schools. This analysis revealed that classroom design and layout accounted for up to 16% through analyses of student achievement, classroom physical environment and design characteristics [20,65]. Haverinen-Shaughnessy and Shaughnessy [66] found that maintaining adequate ventilation and thermal comfort in the classroom can improve students’ test scores, based on research from 140 fifth-grade classes in 70 elementary school districts in the south-western United States. The finding is supported by Korsavi and Montazami [22]. Adeyemi and Lasisi [67] found that there was a significant improvement in the students’ academic performance after the intervention of ergonomic furniture among students of tertiary institutions in Northwest Nigeria. Llinares, Higuera-Trujillo [24] found that cool colours are effective in improving memory and attention performance after assessing 160 participants, using 12 warm colours and 12 cool colours in a virtual classroom. In accordance with these studies, other research also found the physical space characteristics affect students’ behaviour and self-esteem [68], cognitive and affective domains [69], and learning progress [20]. Figure 1 shows the relationship between learning space and students’ learning, demonstrating that favorable space elements positively influence students’ spatial perception and emotions, which in turn improves their learning performance. However, interior spaces in primary schools often face challenges related to noise, air quality [70], ventilation [71], and furniture. In addition, other issues such as overloading, large class sizes, and decreased activity spaces affect teaching quality as well as the physical and mental health of students in China [21].

Figure 1.

The relationship of learning space with student performance from the literature.

Barrett et al. [20] proposed the SIN model, established based on an in-depth exploration of the brain’s implicit systems performed by Rolls [72]. This model encapsulates a person’s holistic perception of space, formed by the integration of various influences processed by the brain and senses. This model applies neuroscientific theories on how the human brain processes information and involves the following design principles and factors [20] as stated in Table 1: (1) naturalness—light, sound, temperature, air quality, and natural view; (2) individualisation—ownership and flexibility; and (3) stimulation—complexity and colour. This study adopted the approach outlined by Zeisel et al. [73] and Barrett et al. [20], constructing an environment–behaviour factors model based on existing literature. The SIN model was informed by preparatory surveys of pupils [28] and teachers [29], post-occupancy evaluations of schools [74], and the Chinese Code for Design of School GB 5099-2011 [75]. Design guidelines for primary and secondary schools in China strictly follow the Code for Design of School GB 5099-2011, which includes specific requirements for window size, ventilation frequency, and room height. This study modified and refined design parameters and factors by integrating the environment–behaviour factors model with the specific provisions set out in the code and relevant literature, based on SIN design principles. Table 1 summarises the main design elements extracted from the literature and the Code for Design of School GB 5099-2011.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

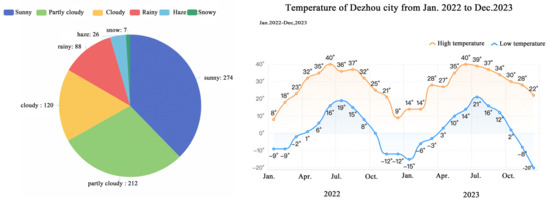

All surveyed schools are located in Shandong Province, China. Shandong has a warm temperate monsoon climate characterized by hot and rainy summers, cold and dry winters, and four distinct seasons. Precipitation is concentrated in summer, with relatively shorter spring and autumn seasons than winter and summer seasons. According to the data from the Dezhou Meteorological Bureau [76], the average annual temperatures over the past two years ranged from 11 to 14 °C, with temperatures ranging from −20 °C in January to 40 °C in June. The total annual precipitation averaged 883.2 mm. Figure 2 depicts the weather distribution and temperature in Shandong from June 2022 to December 2023. These climatic conditions affect the temperature, lighting, windows direction, and air quality in schools. The optimal classroom temperature normally ranges from 20 to 22 °C, which helps students maintain optimal attention and cognitive function [77]. Temperatures above 25 °C can cause physical discomfort, such as headaches, excessive sweating and dehydration, leading to decreased concentration and cognitive abilities in students, which in turn affects academic performance [77] and lowers learning efficiency [65]. In contrast, cold environments of below 18 °C can also cause discomfort and thus be distracting [66]. The classroom temperature is adjusted according to the season and weather conditions [66], and one should ensure that the temperature in the classroom is kept within the appropriate range of 20–22 °C, using air conditioning or heating equipment as necessary [77].

Figure 2.

Weather distribution map and temperature of Dezhou city in Shandong province, China. Source: https://www.tianqi24.com/dezhou/history.html (access in 10 January 2024).

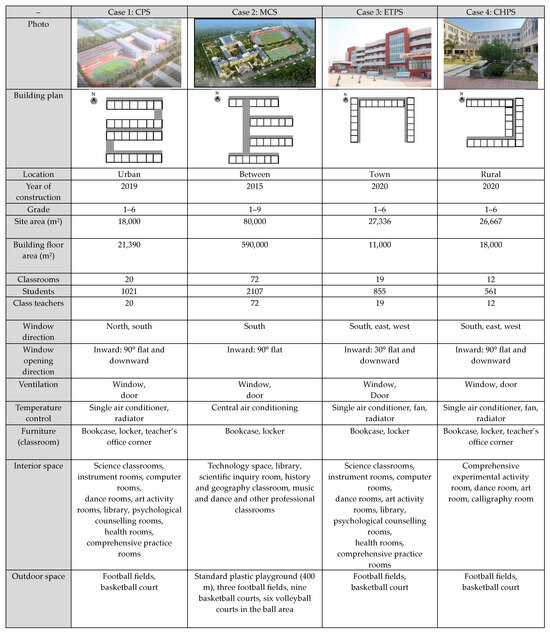

Dezhou City, located in Shandong Province, had 1049 primary schools as of the end of 2023. The Shandong Province Department of Education performed the Shandong Province Public Opinion Survey Center to investigate students’ learning time, sleep time, and homework in 2013. The result show that Dezhou City had the worst implementation of quality education in primary schools and the heaviest school load [78]. To address these issues, this study focused on primary schools located in urban, rural–urban, town, and village areas within the city. These locations were selected due to the significant disparities in compulsory education [79] and school resource quality [80] between urban and rural areas. Four primary schools in Dezhou City were selected as case studies to ensure diversity and richness of data. Figure 3 presents the appearances and layouts of these four schools.

Figure 3.

The appearance and layout of the College primary school (CPS), Mingcheng school (MCS), Ertun primary school (ETPS) and Chunhui primary school (CHPS) in Shandong, China.

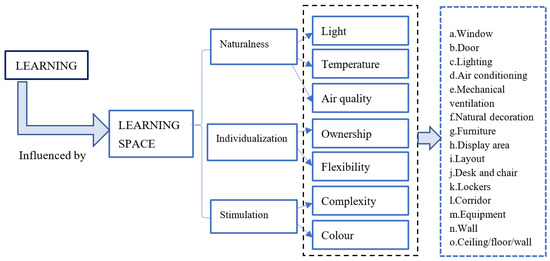

3.2. Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework is shown as Figure 4 of this paper, derived from the SIN model. Learning space issues were identified using observation and group interviews. Focus group interviews can be defined as ‘using a semi structured group session, moderated by a group leader, held in an informal setting, with the purpose of collecting information on a designated topic’ [81]. The selected schools were studied in a similar manner: on-site observations and group interviews with teachers and students, followed by informal interviews with the principals to explore more complex feelings, beliefs, and attitudes.

Figure 4.

The conceptual framework of this study.

The design elements influencing the learning environment were identified using a comprehensive literature review (Table 1). Some aspects of the survey questions were informed by more general user surveys, such as building use studies [82]. Barrett and Zhang’s [29] teacher questionnaire, along with the student questionnaire [28], served as crucial references for this study. The observation parameters consisted of 15 design elements and interview questions comprising nine classroom parameters (Table 1). The interview questions were reviewed by two educational experts, who clarified some confusing questions. After piloting the questionnaire at the first school, respondents found the questionnaire clear and easy to complete. Therefore, only minor enhancements were made before distributing the questionnaire to all four schools.

3.3. Participants

The sample included 18 class teachers, each with more than 2 years of teaching experience and 72 students in Grades 3–5, aged between 7 and 11 years old. The respondents were familiar with the school physical environment and provided accurate answers based on their perceptions or experience. Table 2 presents the basic characteristics of the schools and the number of participants.

Table 2.

Case or school profiles.

3.4. Thematic Analysis

The interview findings have been summarised using thematic analysis [83]. The group interviews were recorded and transcribed. All recordings were converted to text, which was edited and sorted, individually numbered, and imported into NVivo as internal data. For example, data No. 202309-S-1 indicate that the interview time was September 2023 and that the interviewees were students. The group interview data were analysed manually using Braun and Clarke’s [83] six-step thematic analysis approach.

4. Results

Although the Chinese government has invested substantial funds in constructing new schools, many issues persist regarding the use of these newly built schools, which were designed according to the Code for Design of School GB 5099-2011. The student and teachers’ data analysis was organised around the four themes of holistic impressions (HI), space components (SC), colour and pattern (CAP), and furniture and accessories (FAA), along with their sub-themes, shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

The themes and sub-themes of this study.

4.1. Holistic Impressions (HI)

Holistic Impressions (HI) referred to individuals’ first impressions when using and perceiving space. The HI contained three sub-themes of monotonous layout, congested space, and uncomfortable physical environment.

4.1.1. Monotonous Layout

The classroom serves as the primary learning space for students in school, requiring a layout that prioritizes comfort. Although the Code specifies the classroom size and corridor width, it lacks specific guidance on classroom and corridor arrangements. Therefore, corridor-connected classrooms often only meet basic teaching requirements. According to the Code, buildings should not exceed four floors. Consequently, practical usage dictates that students change classrooms annually to accommodate new Grade 1 students each year, with school administrators considering student mobility. Younger grades are typically located on lower floors, and older grades on high floors. The users mentioned that:

“The corridor has very little functionality, mainly just walking through it.”(Case 4: T-P1, 2023)

“There are very few places for children to move… Students have too little time to run and jump. If the corridor were wider, the decoration would not be important… there is no place for students to engage activities between classes; they almost always stay in the classroom, however, the classroom is crowded.”(Case 1: T-P4, 2023)

4.1.2. Congested Space

The four schools had crowded classrooms and limited activity spaces. Primary schools are designed for 45-student classes based on the Code, but in practice, each class accommodates 50 to 60 students. The high number of students and limited spaces lead to insufficient storage and activity spaces. In the classrooms, students primarily remain seated in their chairs, with insufficient room for activities. The participants mentioned that:

“I think the first problem is the space, it is too small and crowded, there is no place for students to put things.”(Case 1: T-P1, 2023)

“The oppressive feeling comes from the crowded environment. There is no space at the back of the classroom and no place for activities in the classroom. The main problem now is crowding, though not excessively so.”(Case 2: SG1P1, 2023)

The current space limits effective interaction and small-group collaboration. Accommodating a large number of students in a limited space makes it difficult for them to engage deeply in collaborative learning activities with their peers. One user observed that:

“Group cooperative learning involves discussions in front of or between the tables, with four students in each group. The seats are fixed and cannot be moved. When we need to discuss, we quickly turn to face each other, and the chair design is not very conducive to this.”(Case 3: SG1P2, 2023)

4.1.3. Uncomfortable Physical Environment

According to Code 4.3.3, regular classrooms should receive at least two hours of daylight exposure during the winter so that students receive sufficient natural light. However, users encountered glare issues when staying in their classrooms. The users provided the following statements:

“Some classrooms close the curtains and turn on the lights during the daytime… This is problematic, classroom should be use transparent curtains that reduce glare without blocking the light.”(Case 1: T-P3, 2023)

“Sometimes when the sunlight is strong, we need to close the curtains and turn on the light because we can’t see the all-in-one interactive machine clearly.”(Case 2: SG2P2, 2023)

The four schools experience notable temperature variations between summer and winter, heating during the winter and cooling during the summer. The interviews revealed high temperatures within the school during the summer. One user stated that:

“Some classrooms have air conditioning, but not in our building. It gets very hot in the summer, making it impossible to have classes on the top floor. The poor ventilation causes students to feel restless.”(Case 1: T-P1, 2023)

Due to the consistent temperature maintenance in both summer and winter, the duration of window ventilation was significantly decreased, leading to deteriorating air quality in classrooms crowded with many students. Two users stated:

“Classroom windows are equipped with inward-opening components, but they are often broken. Inward-opening windows are not very effective for ventilation. The only way to ventilate is through the crack.”(Case 1: T-P2, 2023)

“It’s a bit hot in the summer, and the air quality is not so good because the windows cannot be kept open for long periods. In order to keep the temperature low, the classroom keeps the windows or doors closed.”(Case 2: SG1P3, 2023)

4.2. Space Components (SC)

Under the space components (SC), the sub-themes included unsafe windows and floors and offset tile walls. Most teachers and students expressed concerns related to these aspects of the learning space.

4.2.1. Unsafe Windows and Floors

The teachers and students identified windows as a major component, as they affect lighting, ventilation, and temperature. They repeatedly mentioned safety concerns related to inward-opening windows, which encroach upon students’ learning space, and have rigid corners and edges that pose an injury risk to students. The users stated that:

“The windows open inwards most of the time. It’s a safety issue when it’s flat. Students always be hurt by the corner and hard edge.”(Case 2: T-P4, 2023)

“The design of the school window is indeed a problem. The kid might hit their head when looking outside through the window.”(Case 1: T-P1, 2023)

Some teachers also mentioned that the classroom floors were tiled and quite hard, expressing concern about students potentially falling. One of the teachers mentioned that:

“Do not dare to let students to engage activities between classes. The tile floor makes it unsafe for them to run, as we are afraid of falling. Children love to move, and head teachers are worried about the safety issues.”(Case 2: T-P3, 2023)

4.2.2. Offset Tile Walls

All four classroom walls have tiled wainscoting extending to a height of at least 1.2 m. This feature effectively prevents wall-dirtying issues. Nevertheless, some teachers affixed students’ work directly to the walls, resulting to cleaning challenges. Furthermore, each classroom has a designated area on the rear wall for displaying student artwork. In one school, both sides of the classroom contained designated display areas. The hallways of all four schools have exhibition walls, with one school combining display cabinets, seating, and exhibition areas in the corridors.

“It is difficult to remove glue from the tile, and cleaning the tiles in each new classroom is very troublesome. It takes a week to clean them. I actually think the display area is quite large.”(Case 2: T-P3, 2023)

4.3. Colour and Pattern (CAP)

Colour and pattern (CAP) play a significant role in creating an inviting and stimulating learning environment. Sub-themes include monochromatic colours, understated decorations, and contrasting tile walls. Colour and decoration impact students’ cognitive performance, behavior, and engagement. Brightly colored or patterned feature walls can capture attention and create focal points, while elements like plants and nature-themed decorations can alleviate stress and enhance concentration. Classrooms that are attractively decorated but not overly stimulating can encourage positive behavior and boost student engagement.

4.3.1. Monochromatic Colour

Some students felt that the classroom walls were plain and wished for the addition of patterns and colour on the wall, as well as ceiling patterns. This is shown by the responses from two of the students, as follows:

“The suspended ceiling is currently white, but it can be decorated with the feeling of starry sky. When you look up, you can see the sky, which makes people feel relaxed and close to nature.”(Case 1: SG1P6, 2023)

“The ceiling features white clouds and blue sky, which gives people the feeling that they are outdoors and close to nature.”(Case 1: SG2P4, 2023)

There are differences in opinion between Grade 3 and Grade 5 students regarding the monochromatic colour scheme of the classroom. Grade 5 students mentioned that excessive patterns could be distracting, while Grade 3 students preferred classrooms with patterns and vibrant colours.

“If there is a pattern on the roof, it may attract attention during class, especially for students who often do not pay attention”(Case 2: SG1P4, 2023)

4.3.2. Unremarkable Decoration

Classroom decorations, such as celebrity calligraphy and class agreements, are ineffective if they are beyond the students’ cognitive abilities or fail to capture their interest. Students prefer viewing their peers’ works and their own drawings or handicrafts. Simultaneously, small classroom decorations can give students a sense of belonging to the school, creating a warm and comfortable feeling. Some respondents have stated that:

“The daily norms of primary and secondary schools are not easily perceived because the text is too small.”(Case 2: SG3P2, 2023)

“In fact, students sometimes may not understand the words posted in the classroom because they are designed by an advertising company. The classroom should feature more decorations that children can understand, maybe they like something close to their interests”(Case 1: T-P4, 2023)

“There are my handmade works and painting on the exhibition wall at the back of the classroom.”(Case 1: SG2P2, 2023)

4.4. Furniture and Accessories (FAA)

Furniture and accessories (FAA) encompass two sub-themes: ill-fitting furniture and challenging décor. Ill-fitting furniture refers to chairs and desks that do not adequately accommodate students’ varying sizes and ergonomic needs, potentially leading to discomfort and health issues. Challenging décor includes accent pieces that are overly stimulating, distracting, or mismatched with the intended learning space, which can hinder students’ abilities to concentrate and engage actively in class activities.

4.5. Discussion

The findings offer insight into the perspectives of students and teachers concerning the learning spaces in Dezhou City, summarised in Table 4. The sub-themes that either supported or hindered student learning, as well as commonalities in viewpoints among students and teachers within each dimension, were discussed. Since all four schools were located in the same area and constructed according to the same Code for Design of School (GB 5099-2011), a more comprehensive evaluation by the users who utilise the facilities was preferable. It was proposed that the significant variations in user opinions related to specific elements of their schools could guide how this evaluation should be conducted.

Table 4.

Thematic group interview findings.

Regarding the dimension of naturalness, significant challenges such as congestion, a monotonous layout, and an uncomfortable physical environment relating to thermal comfort and glare have been raised. These physical space factors significantly influence students’ learning experience and outcomes. The results reveal various issues based on the users’ overall perspectives of current learning spaces. First, congested space lead to increased off-task behavior and decreased on-task behavior [19]. Second, monotonous layouts hinder the use of diverse learning methods [84,85]. Third, high temperatures during summer are frequently raised as a concern by teachers and students. Additionally, poor air quality in classrooms persists during both summer and winter seasons, with ventilation time failing to meet code requirements. Teachers and students have pointed out that high temperatures in summer directly impact students learning, consistent with findings by Barrett and Davies [20] and Higgs and Crisp [86], who noted that naturalness plays a crucial role in human comfort. Teachers and students have observed crowded classrooms, which were not previously mentioned in the literature, possibly exacerbated by the high population in China.

From an individualisation perspective, displaying students’ work and enhancing personal space improve their ownership [58]. Students express a strong preference for seeing their own work displayed in the classroom, which enhances their confidence and fosters a sense of belonging [58,87]. However, classroom design often neglects individualisation. Both teachers and students believe that classrooms lack flexibility, with students seated in fixed position every day. Desks and chairs are not movable during group collaborative learning. Another significant issue is ill-fitting furniture, aligning with numerous research results highlighting micro-ergonomics issues, such as the mismatch between the students’ body dimensions and their desks and chairs [53,54].

In the stimulation dimension, colour is a major issue for students, although teachers did not mention it. Students mentioned that classroom colours were monotonous, and they preferred patterns that were close to natural elements, which is supported by previous research [88,89,90]. Many students expressed dissatisfaction with the colour of the classroom, and some even described the classroom as a “giant magnolia prison”. Several students specifically mentioned a preference for patterns featuring green trees or plants, or the blue sky and white clouds, which made them feel as though they were surrounded by an outdoor environment. This finding is consistent with previous research by Meng and Zhang [90], indicating students’ desire and fondness for nature elements. Some students mentioned that green colours could protect their eyes, as parents and teachers hoped that students could experience reduced myopia and alleviated eye fatigue as a result of watching green patterns [88,89]. Nonetheless, teachers in this study did not find the colour of the spaces to be a major issue, which is supported by Pile [91].

Congestion, a monotonous layout, and unremarkable decoration have not been described previously. Another notable finding is that most students expressed a strong desire for natural factors such as plants or natural patterns. Some teachers even kept turtles in classroom corners to improve student engagement in learning. Additionally, students hoped to display their own works, fostering a sense of responsibility as the students felt they own the classroom [4]. This finding suggests that a sense of belonging to school is associated with better overall well-being and outcomes related to academic achievement [92,93].

5. Conclusions

This study enhanced the understanding of current issues met in learning spaces by integrating data collected from both students and teachers working within the same context. Empirically, this study identified physical space-related issues. Beyond those already identified in the literature, this study revealed new issues related to the specific characteristics of classroom sizes and geographical locations in China. Overall, four themes were identified within these two groups: holistic impressions (HI), space components (SC), colour and pattern (CAP), and furniture and accessories (FAA). These themes encompassed nine sub-themes: space congestion, monotonous layout, unsafe windows and floors, offset tile walls, monochromatic colour, unremarkable decoration, ill-fitting furniture, and challenging decor.

Due to the relatively small sample size and single location of this study, more studies can be extended to other settings or areas. Furthermore, positions, experiences, and backgrounds inevitably influenced the qualitative data analysis. Nonetheless, the study team engaged in collaborative discussions during the analysis to refine and validate the themes, supported by quotes that strengthen the interpretation. Lastly, the experiences in this study were self-reported, thus subject to the limitations of self-report data. Despite these limitations, collecting different viewpoints within the same setting contributes to a deeper understanding of learning spaces in China.

Numerous studies have identified crucial design elements to ensure that buildings are suitable for students. This study makes a significant contribution to the literature by addressing comprehensive issues affecting users in large class sizes, which have not been fully explored previously. This study highlighted crucial factors that designers and policymakers should consider when promoting a comfortable, efficient, and healthy learning environment for students.

Future research should increase the sample size in various areas and provide more comprehensive references to enhance existing guidelines for designers and school leaders. This will aid in improving the design of on-site learning spaces, as student-centered learning methods offer clear benefits. Utilizing evaluation tools to assess the interior environment of learning spaces and developing design guidelines with detailed requirements for furniture, decoration, and color is essential. A pleasant, warm, and flexible learning environment is crucial for promoting user well-being and performance. Specifically, attractive colors and images, ergonomic furniture, adequate acoustics, thermal comfort, ventilation, and natural lighting are important features that school designers should prioritize.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F. and R.S.; methodology, R.S.; formal analysis, R.S.; investigation, R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S.; supervision, M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study has been approved by the Jawatankuasa Etika Penyelidikan Manusia Universiti Sains Malaysia (JEPeM-USM). The code is USM/JEPeM/PP/23020167 (protocol code USM/JEPeM/PP/23020167 and date of approval 23 June 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available by contacting the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Ministry of Higher Education of Malaysia (MoE) in particular the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) (FRGS/1/2020/SSI02/USM/02/3) for funding the main study on spatial enhancement. The local authority has played a crucial role in carrying out extremely useful tasks that make it easier to interact with the schools and obtain data. We would like to thank the leaders, teachers, students and parents of the four schools for their support, which allowed the research to proceed smoothly. Heartfelt thanks to anyone who provided help, support or constructive comments on this study. Thank you also to everyone else who has contributed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Deemer, S. Classroom goal orientation in high school classrooms: Revealing links between teacher beliefs and classroom environments. Educ. Res. 2004, 46, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiteri, J. Young Children’s Experiences in Nature as a Precursor to Achieving Sustainability. In Quality Education; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, N.M.; Evans, G.W. Nearby Nature: A Buffer of Life Stress among Rural Children. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVries, R.; Zan, B. Moral Classrooms, Moral Children: Creating a Constructivist Atmosphere in Early Education; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; Volume 47. [Google Scholar]

- Küller, R.; Mikellides, B.; Janssens, J. Color, arousal, and performance—A comparison of three experiments. Color Res. Appl. Endorsed by Inter-Soc. Color Counc. Colour Group (Great Br.) Can. Soc. Color Color Sci. Assoc. Jpn. Dutch Soc. Study Color Swed. Colour Cent. Found. Colour Soc. Aust. Cent. Français De La Coul. 2009, 34, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oblinger, D. Learning Spaces; Educause: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; Volume 444. [Google Scholar]

- Monahan, T. Built pedagogies & technology practices: Designing for participatory learning. In Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 28 November–1 December 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Monahan, T. Flexible Space & Built Pedagogy: Emerging IT Embodiments. 2002. Available online: https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/concern/articles/37720p826 (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Monahan, T. Globalization, Technological Change, and Public Education; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland, B.S.; Soccio, P. Evaluating the Pedagogical Effectiveness of Learning Spaces. 2015. Available online: https://anzasca.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/049_Cleveland_Soccio_ASA2015.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Niemi, K.; Minkkinen, J.; Poikkeus, A.-M. Opening up learning environments: Liking school among students in reformed learning spaces. Educ. Rev. 2022, 76, 1191–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardellino, P.; Woolner, P. Designing for transformation—A case study of open learning spaces and educational change. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2019, 28, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, D.; Morrison, C. Re/assembling ‘innovative’ learning environments: Affective practice and its politics. Educ. Philos. Theory 2017, 49, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smardon, D.; Charteris, J.; Nelson, E. Shifts to Learning Eco-Systems: Principals’ and Teachers’ Perceptions of Innovative Learning Environments. N. Z. J. Teach. Work 2015, 12, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S. Review of Education Capital. 2011. Available online: https://www.thegovernor.org.uk/freedownloads/managingresources/James%20review%20of%20education%20capital%202011.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Evans, R.; Holt, L. Young people’s participation in school design: Exploring diversity and power in a UK governmental policy case-study. In Diverse Spaces of Childhood and Youth; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016; pp. 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Che Ahmad, C.N.; Shaharim, S.A.; Abdullah, M.F.N.L. Teacher-Student Interactions, Learning Commitment, Learning Environment and Their Relationship with Student Learning Comfort. J. Turk. Sci. Educ. 2017, 14, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennell, P. Teaching too little to too many: Teaching loads and class size in secondary schools in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2022, 94, 102651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatchford, P.; Bassett, P.; Brown, P. Examining the effect of class size on classroom engagement and teacher–pupil interaction: Differences in relation to pupil prior attainment and primary vs. secondary schools. Learn. Instr. 2011, 21, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P.; Davies, F.; Zhang, Y.; Barrett, L. The impact of classroom design on pupils’ learning: Final results of a holistic, multi-level analysis. Build. Environ. 2015, 89, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, G. Research on space potential excavating of existing primary school under the base of schooling demand forecasting model—A case study in new urban districts. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 101871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsavi, S.S.; Montazami, A.; Mumovic, D. The impact of indoor environment quality (IEQ) on school children’s overall comfort in the UK; a regression approach. Build. Environ. 2020, 185, 107309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkey, L.; Leggett, V.; Anslow, C.; Ackley, A. The Use of Furniture in a Student-Centred Primary School Learning Environment. N. Z. J. Educ. Stud. 2021, 56, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llinares, C.; Higuera-Trujillo, J.L.; Serra, J. Cold and warm coloured classrooms. Effects on students’ attention and memory measured through psychological and neurophysiological responses. Build. Environ. 2021, 196, 107726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.V.; Godwin, K.E.; Seltman, H. Visual Environment, Attention Allocation, and Learning in Young Children: When Too Much of a Good Thing May Be Bad. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, K. The Impact Ofcolor on Learning.; Perkins & Will, NeoCON.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, K.; Cagatay, K.; Ayalp, N. Effect of wall colour on the perception of classrooms. Indoor Built Environ. 2015, 24, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P.; Zhang, Y.; Barrett, L. A child’s eye view of primary school built environments. Intell. Build. Int. 2011, 3, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P.; Zhang, Y. Teachers’ views on the designs of their primary schools. Intell. Build. Int. 2012, 4, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P.; Davies, F.; Zhang, Y.; Barrett, L. The Holistic Impact of Classroom Spaces on Learning in Specific Subjects. Environ. Behav. 2016, 49, 425–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressly, P.K.; Heesacker, M. The physical environment and counseling: A review of theory and research. J. Couns. Dev. 2001, 79, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.W.; McCoy, J.M. When buildings don’t work: The role of architecture in human health. J. Environ. Psychol. 1998, 18, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornara, F.; Manca, S. Healthy residential environments for the elderly. In Handbook of Environmental Psychology and Quality of Life Research. International Handbooks of Quality-of-Life; Springer: Cham, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 441–465. [Google Scholar]

- Kidger, J.; Araya, R.; Donovan, J.; Gunnell, D. The Effect of the School Environment on the Emotional Health of Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2012, 129, 925–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellucci, H.I.; Arezes, P.M.; Molenbroek, J.F.M.; de Bruin, R.; Viviani, C. The influence of school furniture on students’ performance and physical responses: Results of a systematic review. Ergonomics 2017, 60, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leijon, M.; Nordmo, I.; Tieva, Å.; Troelsen, R. Formal learning spaces in Higher Education—A systematic review. Teach. High. Educ. 2022, 29, 1460–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C.K. Effects of school design on student outcomes. J. Educ. Adm. 2009, 47, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heschong, L.; Wright, R.; Okura, S. Daylighting Impacts on Human Performance in School. J. Illum. Eng. Soc. 2013, 31, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, R.M.; Nichole Maesano, C.; Christoffersen, J.; Mandin, C.; Csobod, E.; de Oliveira Fernandes, E.; Annesi-Maesano, I.; Consortium, S. Daylight and School Performance in European. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loisos, G. Daylighting in Schools; Heschong Mahone Group: St. Oakland, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Winterbottom, M.; Wilkins, A. Lighting and discomfort in the classroom. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radun, J.; Lindberg, M.; Lahti, A.; Veermans, M.; Alakoivu, R.; Hongisto, V. Pupils’ experience of noise in two acoustically different classrooms. Facilities 2023, 41, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brill, L.C.; Wang, L.M. Higher Sound Levels in K-12 Classrooms Correlate to Lower Math Achievement Scores. Front. Built Environ. 2021, 7, 688395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wargocki, P.; Wyon, D.P.; Matysiak, B.; Irgens, S. The Effects of Classroom Air Temperature and Outdoor Air Supply Rate on Performance of School Work by Children. 2005. Available online: https://orbit.dtu.dk/en/publications/the-effects-of-classroom-air-temperature-and-outdoor-air-supply-r (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Coley, D.A.; Greeves, R.; Saxby, B.K. The Effect of Low Ventilation Rates on the Cognitive Function of a Primary School Class. Int. J. Vent. 2007, 6, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakó-Biró, Z.; Clements-Croome, D.J.; Kochhar, N.; Awbi, H.B.; Williams, M.J. Ventilation rates in schools and pupils’ performance. Build. Environ. 2012, 48, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, E.F.; Major, C.H. Student Engagement Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- van Griethuijsen, R.A.L.F.; van Eijck, M.W.; Haste, H.; den Brok, P.J.; Skinner, N.C.; Mansour, N.; Savran Gencer, A.; BouJaoude, S. Global Patterns in Students’ Views of Science and Interest in Science. Res. Sci. Educ. 2015, 45, 581–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Sullivan, W.C. Impact of views to school landscapes on recovery from stress and mental fatigue. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 148, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Benkowitz, D.; Hellinger, F. Associations between the naturalness of window and interior classroom views, subjective well-being of primary school children and their performance in an attention and concentration test. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Igarashi, M.; Namekawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological and psychological relaxing effects of visual stimulation with foliage plants in high school students. Physiol. Psychol. Relaxing Eff. Vis. Stimul. Foliage Plants High Sch. Stud. 2014, 28, 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- van den Bogerd, N.; Coosje Dijkstra, S.; Koole, S.L.; Seidell, J.C.; de Vries, R.; Maas, J. Nature in the indoor and outdoor study environment and secondary and tertiary education students’ well-being, academic outcomes, and possible mediating pathways: A systematic review with recommendations for science and practice. Health Place 2020, 66, 102403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.W.Y.; Wong, T.K.S. Anthropometric evaluation for primary school furniture design. Ergonomics 2007, 50, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouvali, M.; Boudolos, K. Match between school furniture dimensions and children’s anthropometry. Appl. Ergon. 2006, 37, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podrekar, N.; Kastelic, K.; Sarabon, N. Teachers’ Perspective on Strategies to Reduce Sedentary Behavior in Educational Institutions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, M.S.; LeBlanc, A.G.; Kho, M.E.; Saunders, T.J.; Larouche, R.; Colley, R.C.; Goldfield, G.; Gorber, S.C. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Xu, F. Association of Sedentary Behavior and Depression among College Students Majoring in Design. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killeen, J.P.; Evans, G.W.; Danko, S. The Role Of Permanent Student Artwork In Students’ Sense Of Ownership In An Elementary School. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijapur, D.; Candido, C.; Göçer, Ö.; Wyver, S. A Ten-Year Review of Primary School Flexible Learning Environments: Interior Design and IEQ Performance. Buildings 2021, 11, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumi, R.; Conway, C.M.; Limayem, M.; Goyal, S. Learning in Color: How Color and Affect Influence Learning Outcomes. Prof. Commun. IEEE Trans. 2013, 56, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, E.; Chandler, P.; Sweller, J. Assimilating complex information. Learn. Instr. 2002, 12, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiyong, Z. Confidence and Reflection: The Education Management of Four Provinces and Cities in China from the Perspective of PISA2018. 2019. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/moe_2082/zl_2019n/2019_zl94/201912/t20191204_410712.html (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Lackney, J.A. Educational Facilities: The Impact and Role of the Physical Environment of the School on Teaching, Learning and Educational Outcomes; ERIC: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Halfon, N.; Shulman, E.; Hochstein, M. Brain Development in Early Childhood. Building Community Systems for Young Children; ERIC: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, P.; Zhang, Y.; Moffat, J.; Kobbacy, K. A holistic, multi-level analysis identifying the impact of classroom design on pupils’ learning. Build. Environ. 2013, 59, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverinen-Shaughnessy, U.; Shaughnessy, R.J. Effects of Classroom Ventilation Rate and Temperature on Students’ Test Scores. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, A.J.; Lasisi, O.I.; Ojile, P.; Abdulkadir, M. The effect of furniture intervention on the occurrence of musculoskeletal disorders and academic performance of students in North-West Nigeria. Work 2020, 65, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarudin, N. Faktor Persekitaran Sosial Dan Hubungannya Dengan Pembentukan Jati Diri (Social Environmental Factors and Their Relation to Identity Formation). J. Hadhari Spec. Ed. 2012, 4, 155–172. [Google Scholar]

- Che Ahmad, C.N.; Osman, K.; Halim, L. The establishment of physical aspects of science laboratory environment inventory (PSLEI). J. Turk. Sci. Educ. 2014, 11, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galičič, A.; Rožanec, J.; Kukec, A.; Carli, T.; Medved, S.; Eržen, I. Identification of Indoor Air Quality Factors in Slovenian Schools: National Cross-Sectional Study. Processes 2023, 11, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsavi, S.S.; Montazami, A.; Mumovic, D. Indoor air quality (IAQ) in naturally-ventilated primary schools in the UK: Occupant-related factors. Build. Environ. 2020, 180, 106992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolls, E.T. Emotion Explained; Affective Science: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zeisel, J.; Silverstein, N.M.; Hyde, J.; Levkoff, S.; Lawton, M.P.; Holmes, W. Environmental Correlates to Behavioral Health Outcomes in Alzheimer’s Special Care Units. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 697–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Barrett, P. Findings from a post-occupancy evaluation in the UK primary schools sector. Facilities 2010, 28, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50099-2011; Code for Design of School. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development: Beijing, China, 2010.

- Bureau, D.M. Monthly Temperature Statistics of Dezhou throughout the Year. 2024. Available online: https://www.tianqi24.com/dezhou/history.html (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Wargocki, P.; Wyon, D.P. Providing better thermal and air quality conditions in school classrooms would be cost-effective. Build. Environ. 2013, 59, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- News, S. Shandong Primary and Middle School Students Study Load Survey: Dezhou Heze Primary School Students the Most Tired. 2013. Available online: https://dezhou.dzwww.com/focus/201311/t20131127_9251959.htm (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Xiaohua, Z.; Suhong, Y.; Yuyou, Q. Aspiring for Education with Fairness and Quality:Factors Affecting the Urban-Rural Quality Gap of Compulsory Education and the Balancing Strategies in the New Era. Tsinghua J. Educ. 2018, 39, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Yongkun, F.; Xhihui, W. A Research Report on Balanced Development of Rural and Urban Education Resource in China. Educ. Res. 2014, 35, 32–44+83. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, M.A. The group effect in focus groups—Planning, implementing, and interpreting focus group research. Crit. Issues Qual. Res. Methods 1994, 225, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Leaman, A.; Bordass, B. Are users more tolerant of ‘green’ buildings? Build. Res. Inf. 2007, 35, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J.; Everatt, J.; Subramaniam, Y.D.B.; Ma, T. Perceptions About Innovative and Traditional Learning Spaces: Teachers and Students in New Zealand Primary Schools. N. Z. J. Educ. Stud. 2023, 58, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpytma, C.; Szpytma, M. School architecture for primary education in a post-socialist country: A case study of Poland. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2022, 52, 519–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, J.; Crisp, G.; Letts, W. Education for Employability (Volume 1): The Employability Agenda; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gultekin, M.; Özenç İra, G. Pedagogy-driven Design Fundamentals of 21st-Century Primary Schools’ Physical Learning Environments. J. Educ. Future 2022, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, L.E. Home and school density effects on elementary school children: The role of spatial density. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 566–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, C.; Grosvenor, I. The School I’d Like: Children and Young People’s Reflections on an Education for the 21st Century; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, M. Effects of school indoor visual environment on children’s health outcomes: A systematic review. Health Place 2023, 83, 103021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pile, J.F. Color in Interior Design; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahi, A.; Panahipour, S.; Akhavan Tafti, M.; Allen, K.A. Academic hardiness as a mediator for the relationship between school belonging and academic stress. Psychol. Sch. 2020, 57, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G.; Allen, K.-A.; Ryan, T. Exploring the Impacts of School Belonging on Youth Wellbeing and Mental Health among Turkish Adolescents. Child Indic. Res. 2020, 13, 1619–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).