Effect of Grouting, Concrete Cover, and Combined Reinforcement on Masonry Retaining Walls

Abstract

:1. Introduction

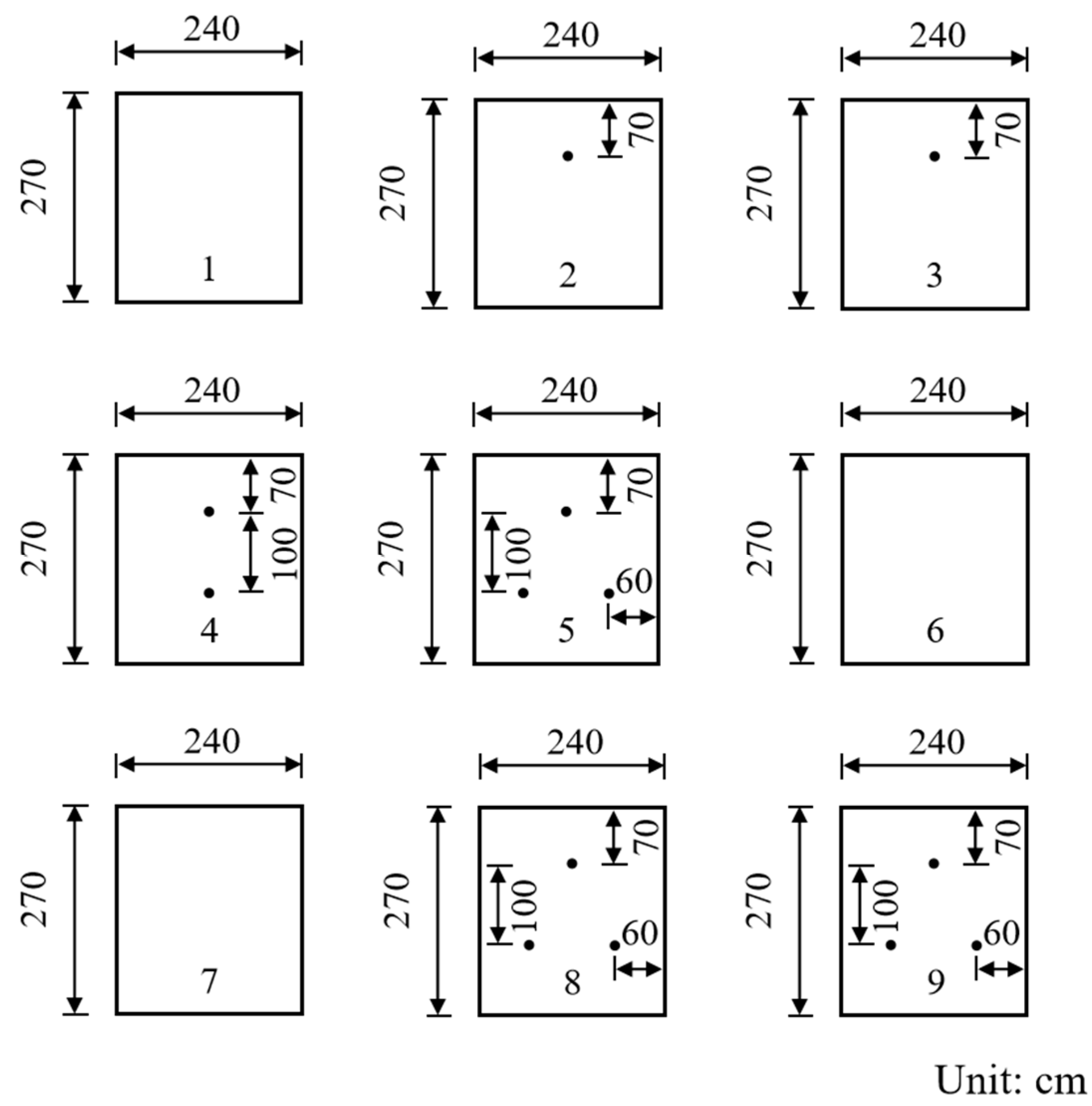

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

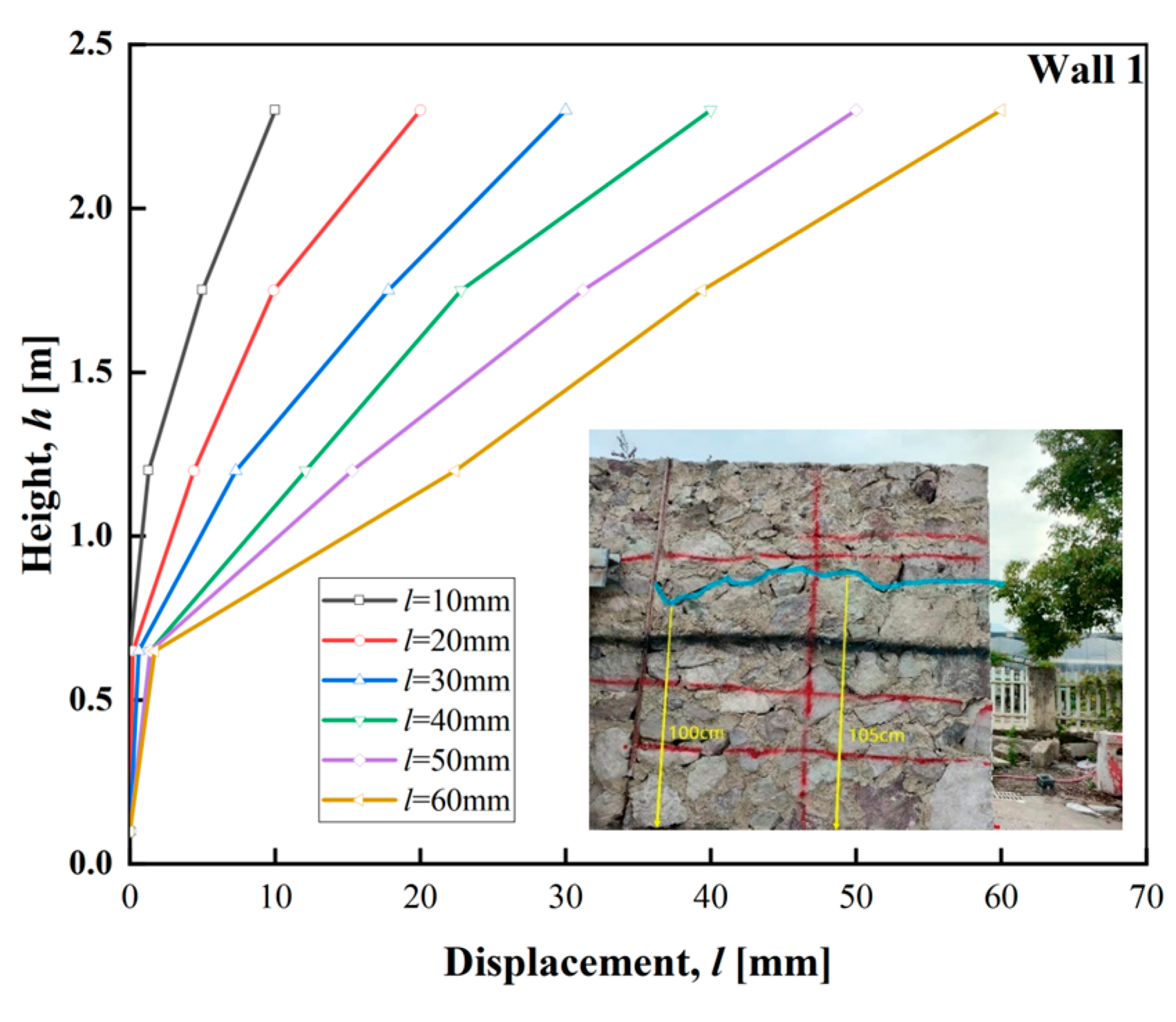

3.1. Unreinforced Retaining Walls

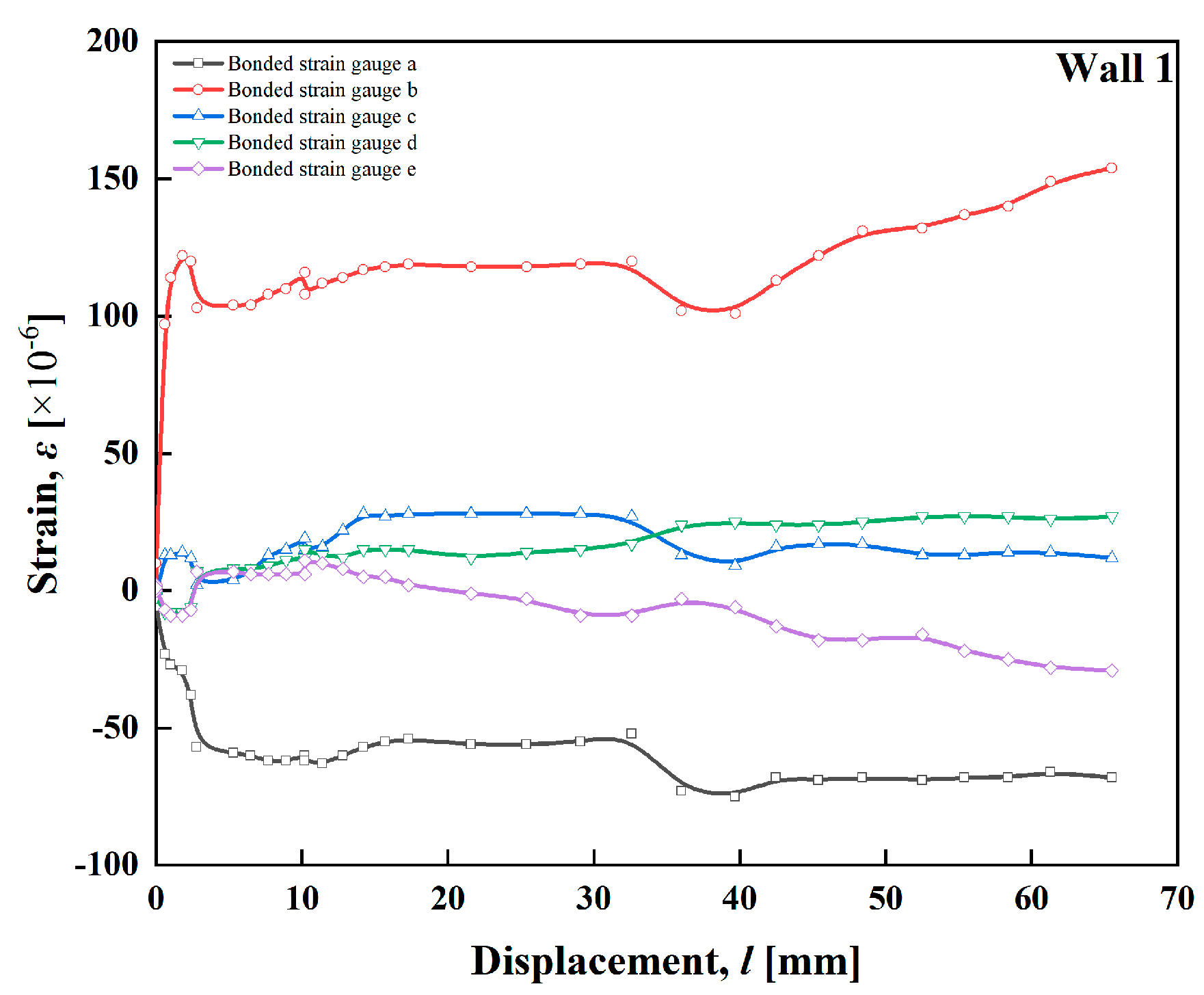

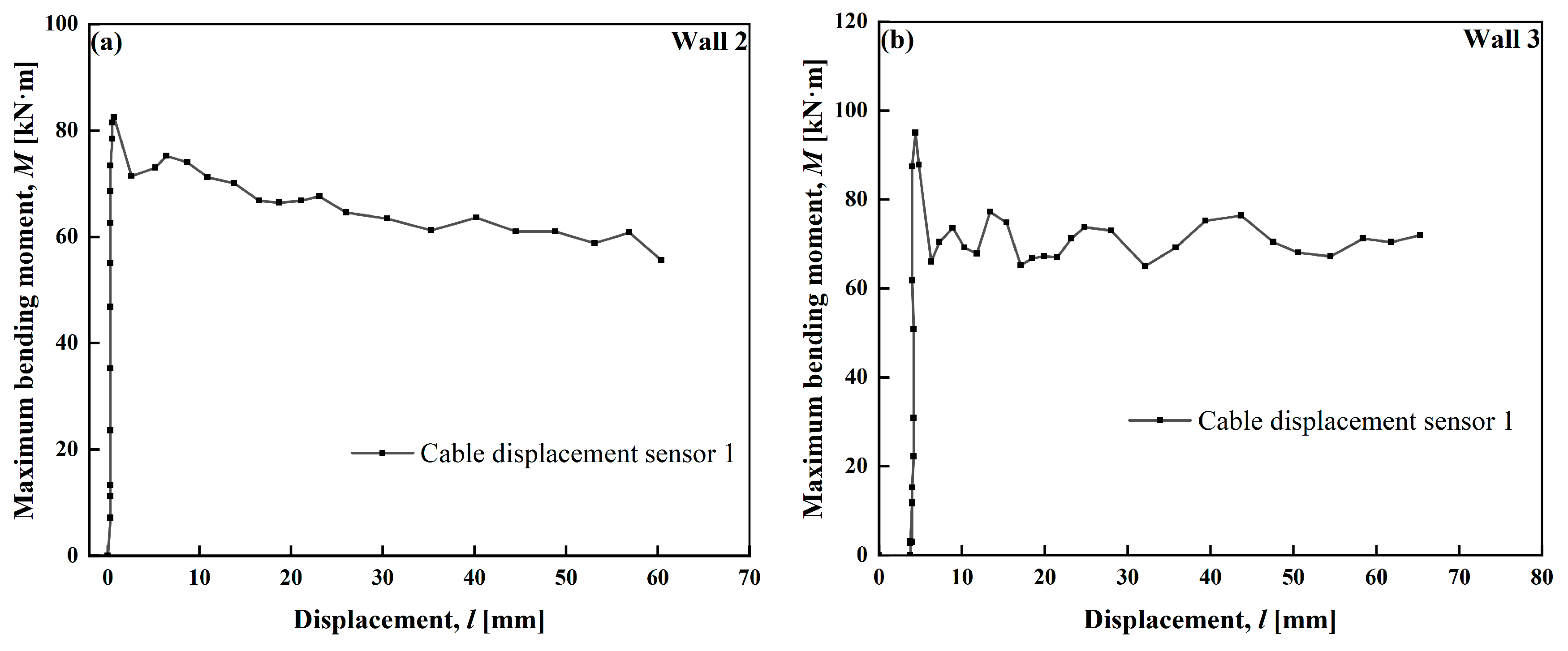

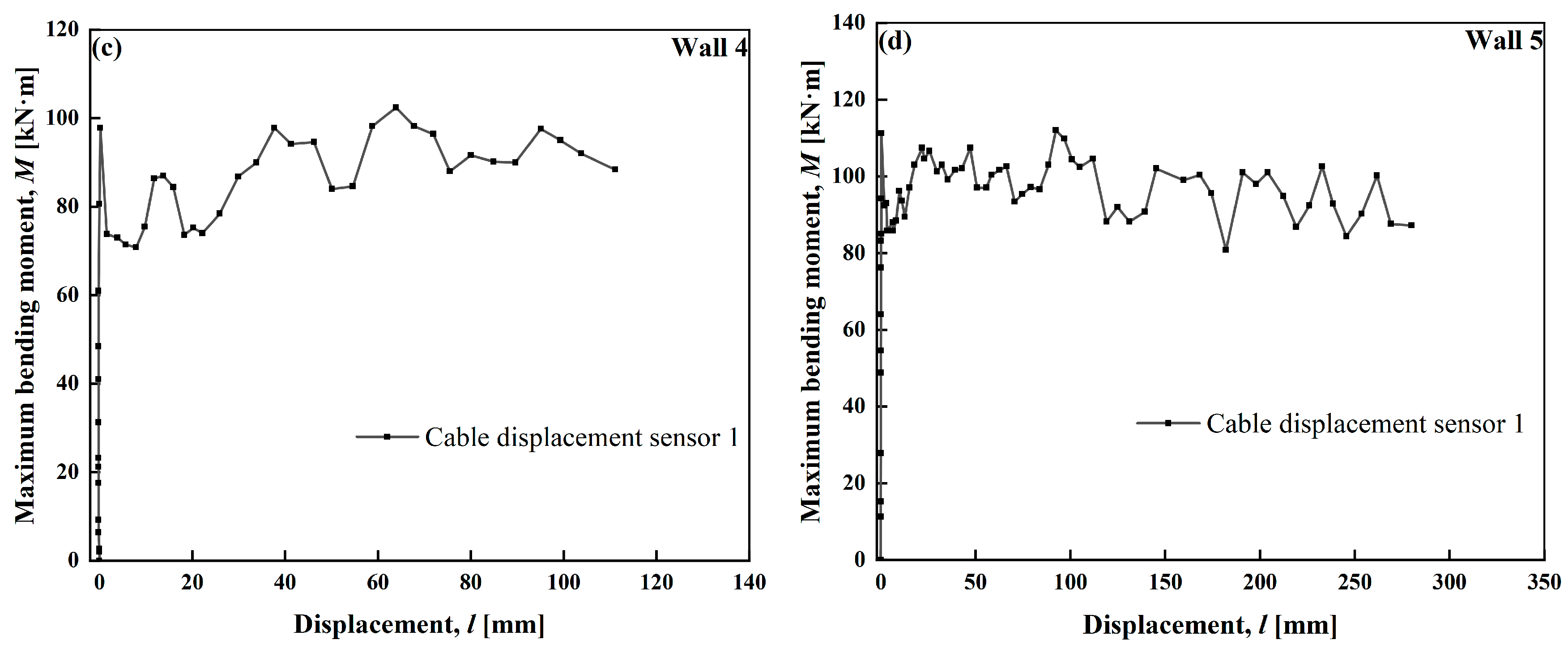

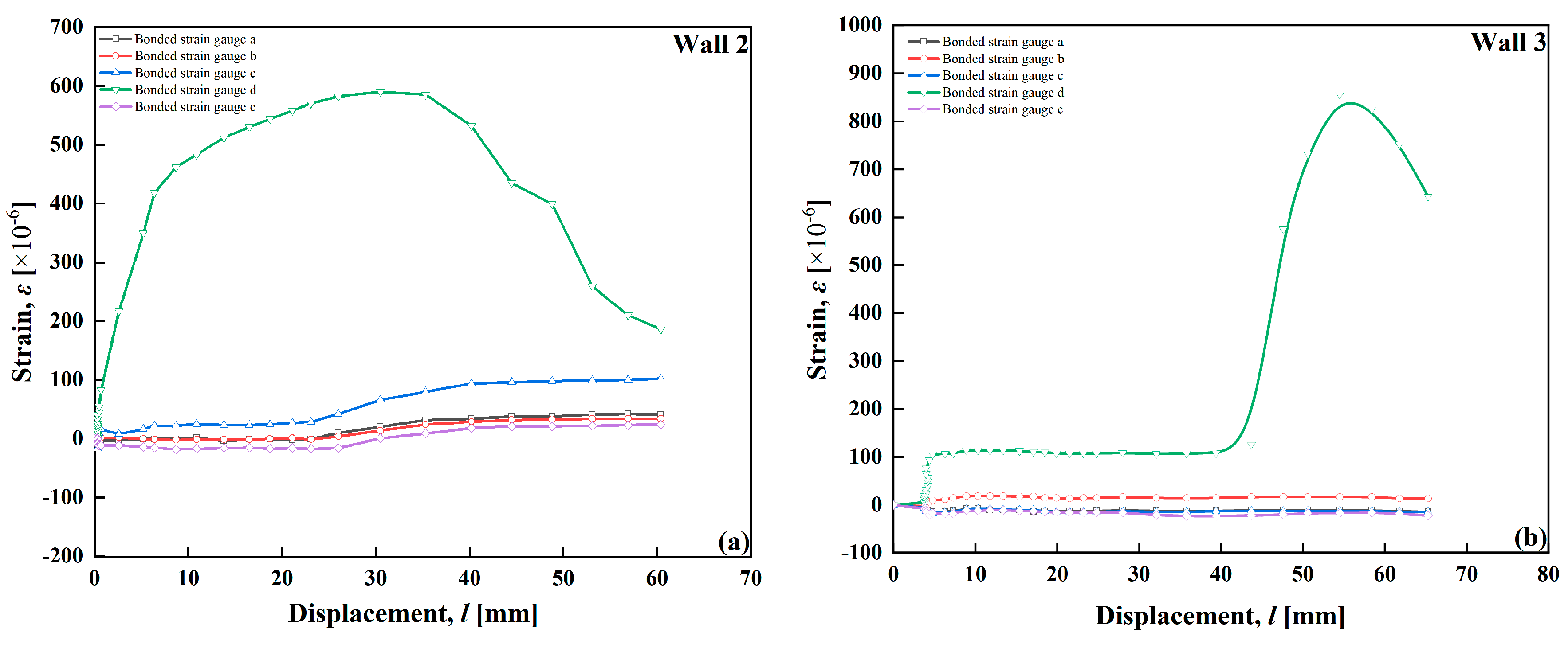

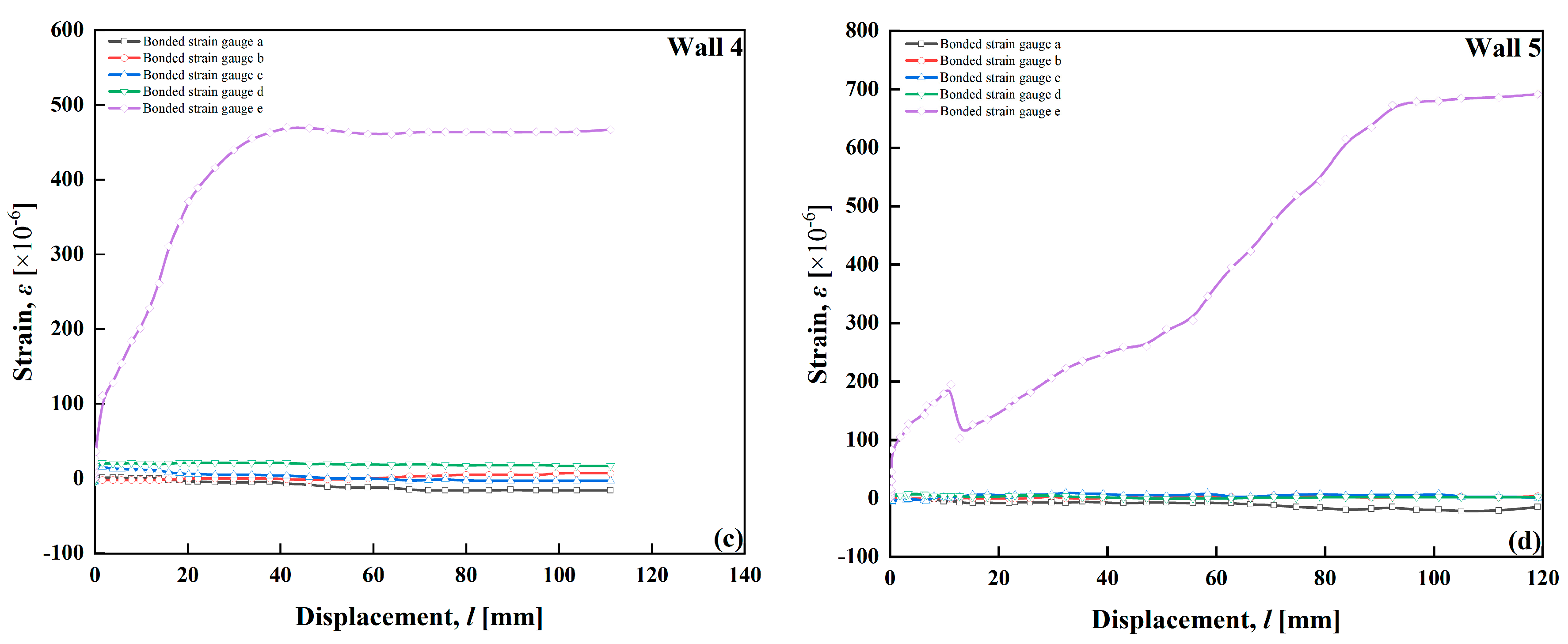

3.2. Grouted Reinforced Retaining Walls

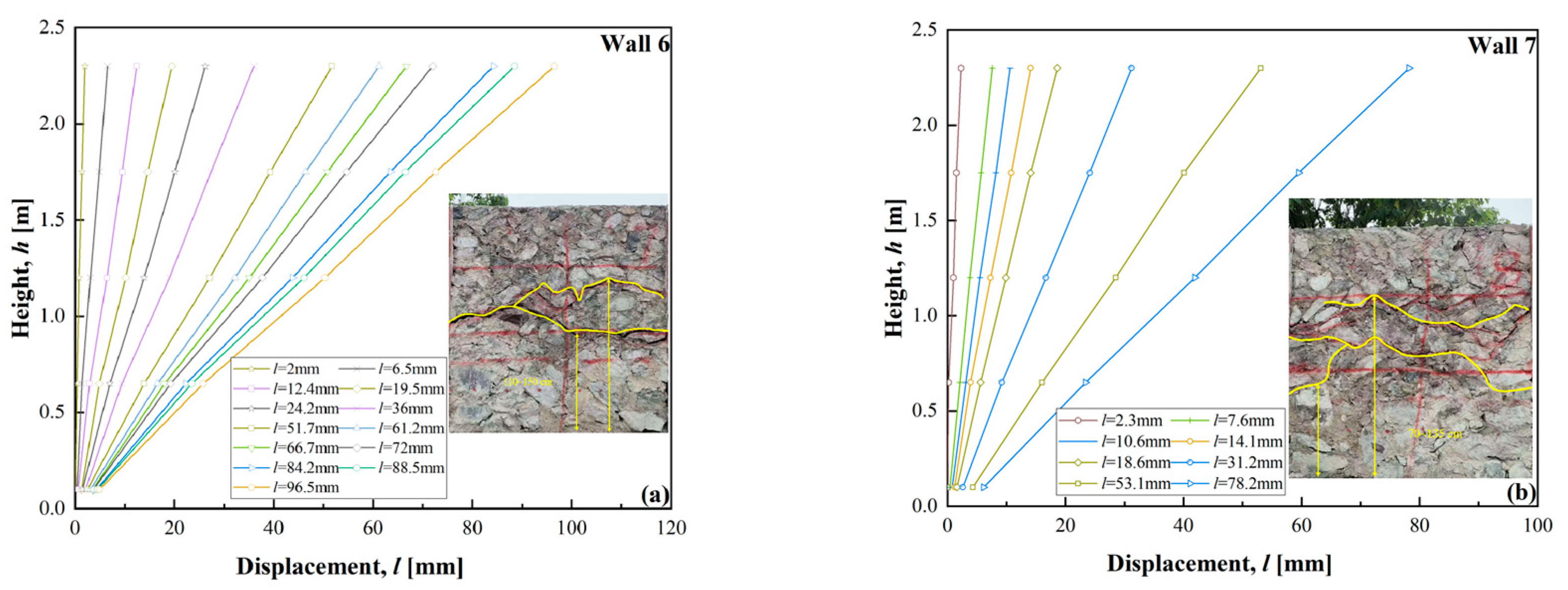

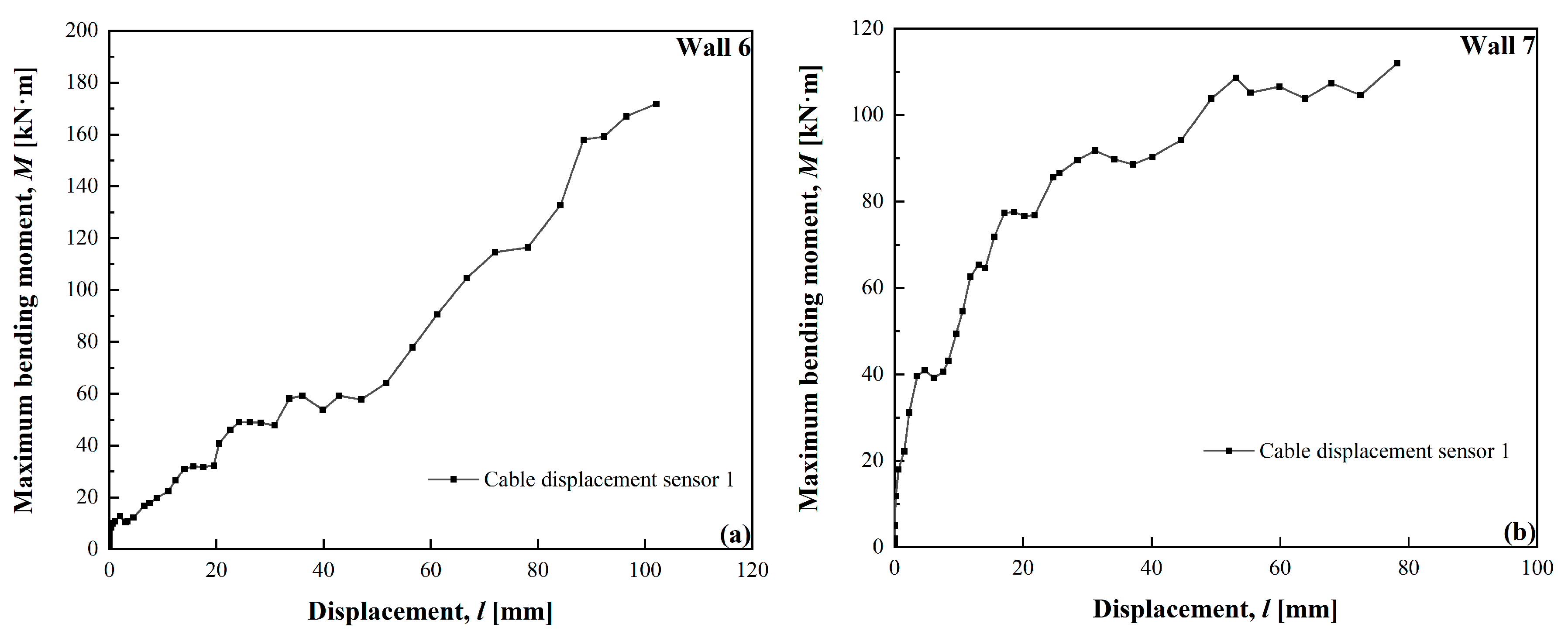

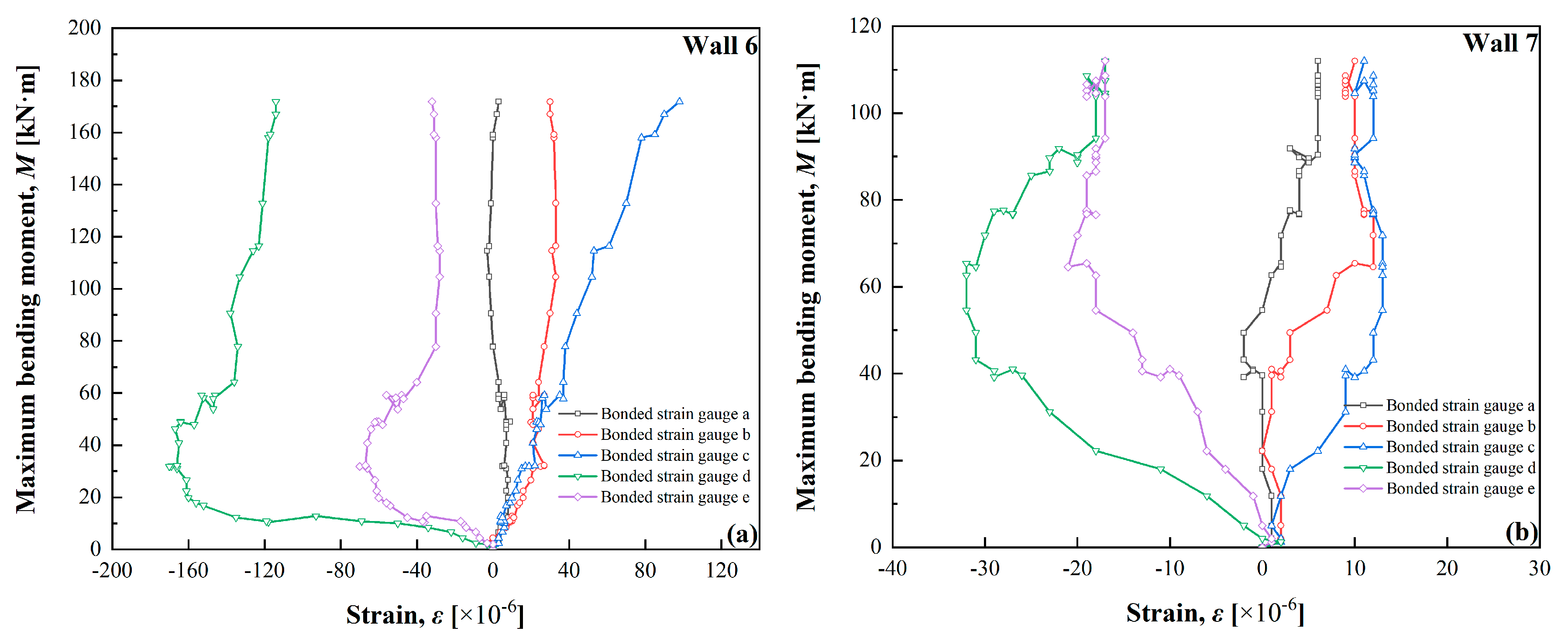

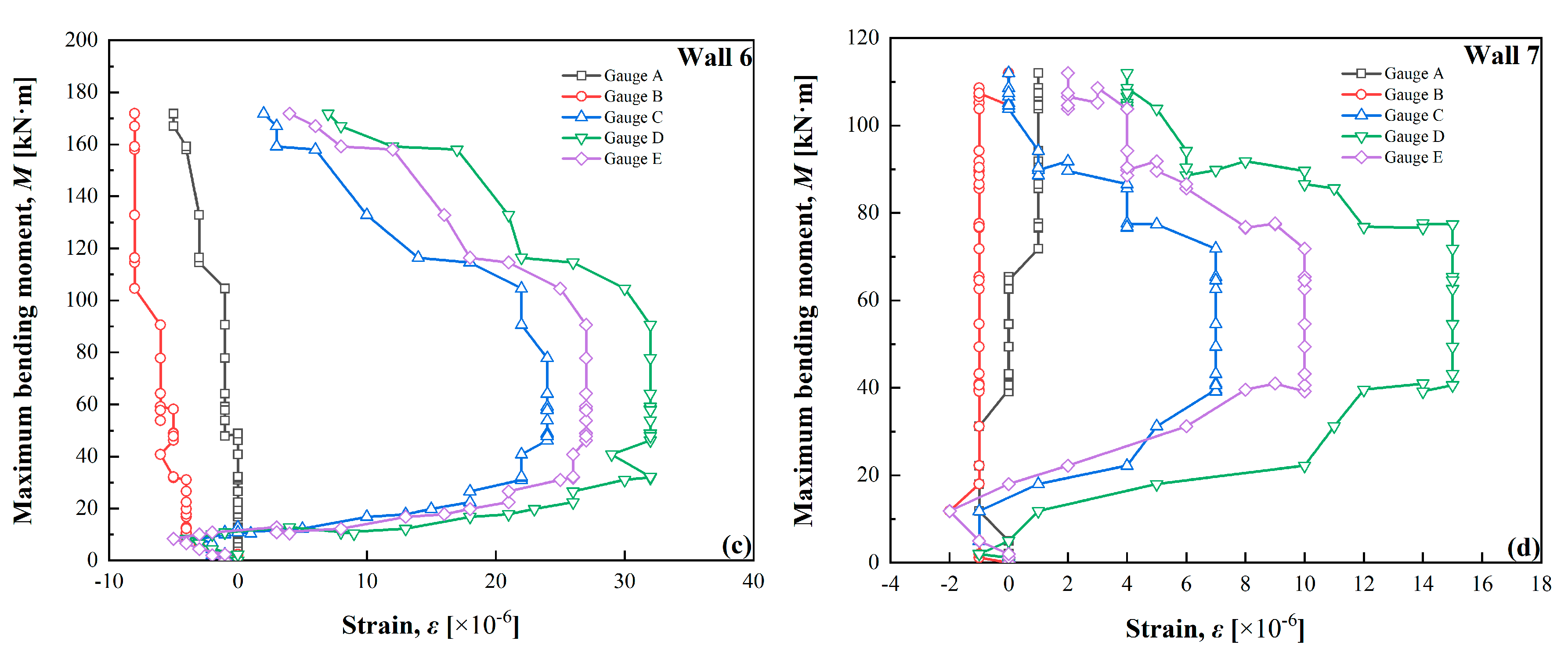

3.3. Reinforced Retaining Walls with Concrete Cover

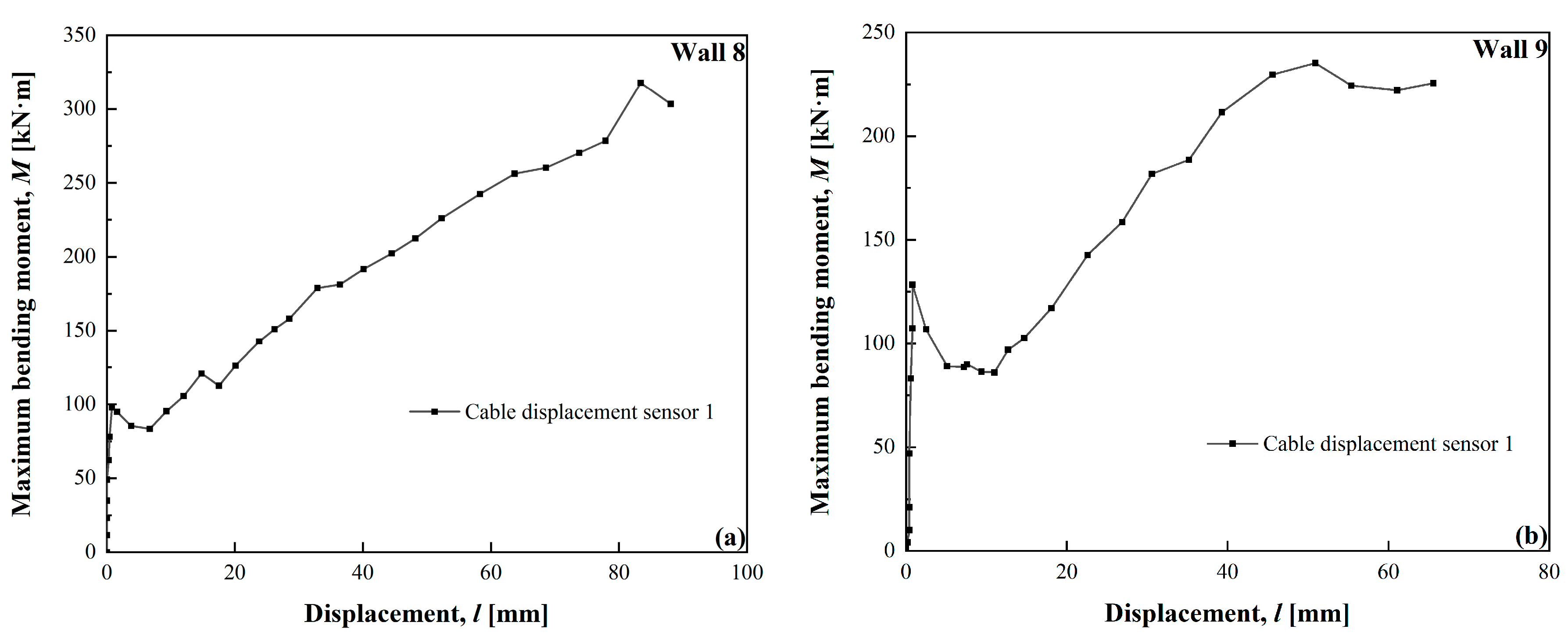

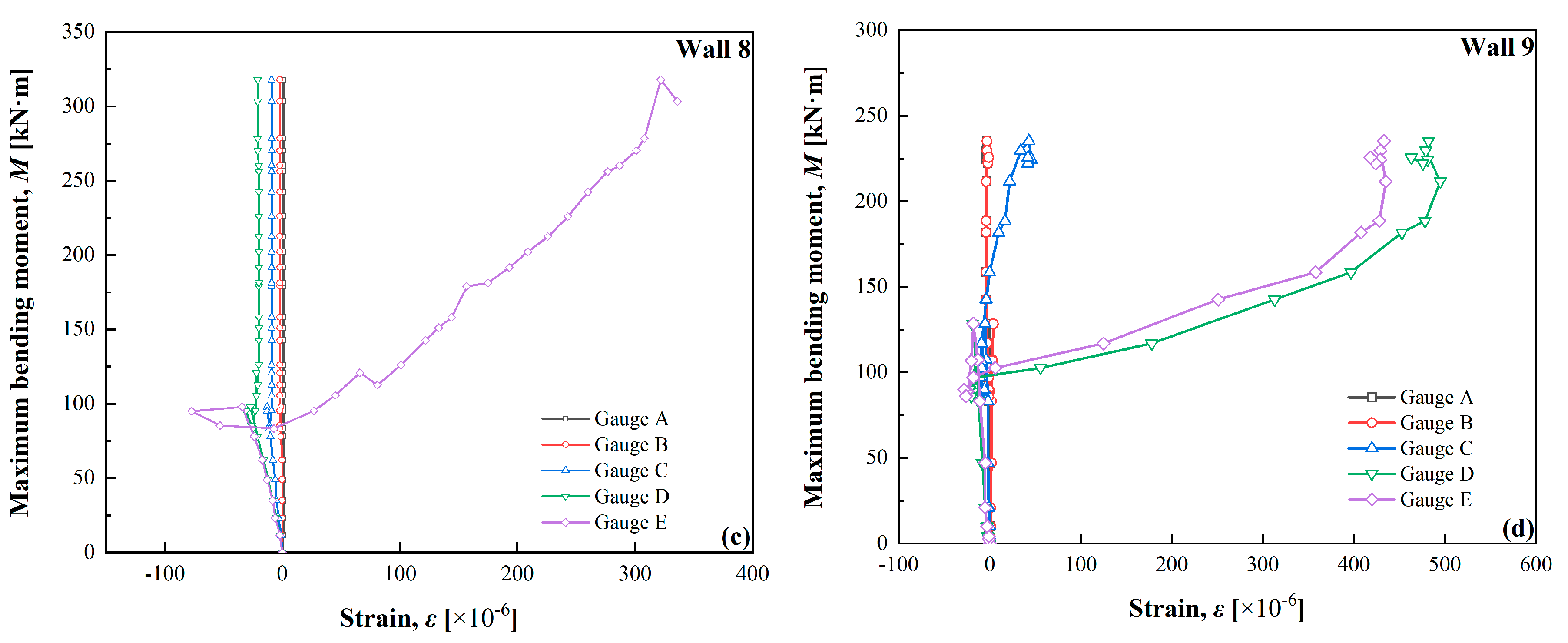

3.4. Composite Reinforced Retaining Wall

3.5. Cost and Construction Cycle

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, B.; Liu, H.L.; Ren, H.P. Basic Discussing on Constructive Faults of Mortar Masonry Retaining Wall and Their Prevention Measures. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 204, 3057–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, K.; Itoh, K.; Tana, T.; Suemasa, N.; Konami, T.; Taniyama, S. Centrifugal tilting tests on vertical reinforcement of the dry masonry retaining wall. In Natural Geo-Disasters and Resiliency; Springer: Singapore, 2024; Volume 445, pp. 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.Q.; Wang, X.F.; Gao, J.X. Stability analysis and reinforcement treatment of open pit slope. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 283, p. 012009. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, W.; Akhtar, S.; Hussain, A. Rehabilitation of concrete and masonry structures. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 2158, p. 020028. [Google Scholar]

- Fusade, L.; Orr, S.A.; Wood, C.; O’Dowd, M.; Viles, H. Drying response of lime-mortar joints in granite masonry after an intense rainfall and after repointing. Herit. Sci. 2019, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L.; Savoikar, P.P. Case study of successful repairs of retaining wall at curtorim goa using sustainable TGSB technology. In Structure and Construction Management: Conference Proceedings; Springer: Singapore, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 315–325. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.M.; Poeppel, A.R. Overcoming grouting difficulties during retaining wall stabilization. In Proceedings of the Grouting 2017: Jet Grouting, Diaphragm Walls, and Deep Mixing, Honolulu, HI, USA, 9–12 July 2017; Volume 289, pp. 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, D.; Sun, Y.; Kong, L. A study on the stability of reinforced tunnel faceusing horizontal pre-grouting. Processes 2023, 11, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Peng, F.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, D. Grouting for tunnel stability control and inadequate grouting section recognition: A case study of countermeasure of giant karst cave. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Wei, G.; Feng, F.; Zhu, J. Method of calculating the compensation for rectifying the horizontal displacement of existing tunnels by grouting. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J. Bridging the gap between engineering properties and grouting reinforcement mechanisms for loess in eastern China: Taking Jinan loess as an example. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2021, 80, 4125–4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Fang, Q.; Li, P.; Pan, R.; Zhu, X. Research on the water inrush mechanism and grouting reinforcement of a weathered trough in a submarine tunnel. Buildings 2024, 14, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, J.; Luo, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, D.; Yu, R.; Li, J. Bearing capacity of a concrete grouting pad on the working surface of a highway tunnel shaft. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, R.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, H. Groundwater runoff pattern and keyhole grouting method in deep mines. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2021, 80, 5743–5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, M.; Huali, P.; Huang, J.; Arshid, M.U.; Khan, Q.U.Z.; Guoqiang, O.; Ahmed, B. Seismic response comparison of various geogrid reinforced earth-retaining walls: Based on shaking table and 3D FE analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismael, B.; Lombardi, D. Evaluation of liquefaction potential for two sites due to the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake sequence. In On Significant Applications of Geophysical Methods: Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 237–241. [Google Scholar]

- Sano, K.; Sahare, A.; Itoh, K.; Tanaka, T.; Suemasa, N.; Konami, T.; Taniyama, S. Novel performance-based seismic reinforcement method for the dry masonry retaining wall located in an urban residential area. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2024, 53, 1935–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Guo, Z.; Liu, Z.; Ma, Z. Experimental study on flexural resistance of concrete layer attached to the outer wall of slurry retaining wall. Jiangxi Build. Mater. 2024, 2, 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- YS/T 5211-2018; Technical Specification for Grouting. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2018.

- GB 50003-2011; Code for Design of Masonry Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2011.

- GB 50010-2010; Code for Design of Concrete Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010.

| Wall Number | Remarks |

|---|---|

| 1 | Unreinforced |

| 2 | Grouted, 1 grouting hole |

| 3 | High-pressure grouting, 1 grouting hole |

| 4 | Grouted, 2 grouting holes |

| 5 | Grouted, 3 grouting holes |

| 6 | Covered with 10 cm thick C30 concrete layer |

| 7 | Covered with 20 cm thick C30 concrete layer |

| 8 | Covered with 10 cm thick C30 concrete layer, grouted, 3 grouting holes |

| 9 | Covered with 10 cm thick C30 concrete layer, grouted, 3 grouting holes with steel grouting pipes |

| Wall Number | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grouting volume | Upper hole | 0.90 | 1.25 | 0.65 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.50 |

| Lower hole | - | - | 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.65 | |

| Total | 0.90 | 1.25 | 1.30 | 1.15 | 1.25 | 1.15 | |

| Content of accelerating agent | Upper hole | 1.5% | 1.5% | 1.5% | 1.5% | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| Lower hole | - | - | 2.5% | 2.5% | 2.5% | 2.5% | |

| Project | Unit Price |

|---|---|

| Masonry retaining wall [CNY/m3] | 560 |

| Grouting [CNY/m3] | 790 |

| Drilling grouting hole [CNY/m] | 335 |

| Steel grouting pipe [CNY/m] | 100 |

| Steel mesh [CNY/kg] | 7.3 |

| Concrete [CNY/m3] | 650 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retaining wall [CNY] | 1456 | ||||||||

| Reinforcement [CNY] | - | 895.25 | 1171.75 | 1666.85 | 2003.95 | 759.5 | 935 | 2942.95 | 2863.95 |

| Total cost [CNY] | 1456 | 2351.25 | 2627.75 | 3122.85 | 3459.95 | 2215.5 | 2391 | 4398.95 | 4319.95 |

| Construction cycle [d] | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, W.; Zhu, C.; Shi, G.; Liu, Z.; Liu, C.; Du, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhuang, C.; Gu, H. Effect of Grouting, Concrete Cover, and Combined Reinforcement on Masonry Retaining Walls. Buildings 2025, 15, 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15030309

Cheng W, Zhu C, Shi G, Liu Z, Liu C, Du Y, Chen Y, Zhuang C, Gu H. Effect of Grouting, Concrete Cover, and Combined Reinforcement on Masonry Retaining Walls. Buildings. 2025; 15(3):309. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15030309

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Wei, Cong Zhu, Gongzuo Shi, Ze Liu, Cheng Liu, Yinguang Du, Yu Chen, Changchun Zhuang, and Hongqiang Gu. 2025. "Effect of Grouting, Concrete Cover, and Combined Reinforcement on Masonry Retaining Walls" Buildings 15, no. 3: 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15030309

APA StyleCheng, W., Zhu, C., Shi, G., Liu, Z., Liu, C., Du, Y., Chen, Y., Zhuang, C., & Gu, H. (2025). Effect of Grouting, Concrete Cover, and Combined Reinforcement on Masonry Retaining Walls. Buildings, 15(3), 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15030309