Abstract

Background: This study aimed to explore the relationship between architectural home design and mental health in older adults living independently in rural Chiang Mai. Methods: A purposive sample of seniors from San Kamphaeng District, living independently, were selected. Participants were assessed using tools like the MSPSS, OI-21, RULS-6, RI-9, PSQI, and a custom Home and Community Environment Satisfaction Scale. Statistical analysis examined correlations between home design, mental health, and satisfaction. Results: The study involved 83 participants (72.3% female, mean age 70.2 ± 6.16). Anxiety (3.51 ± 3.44) and depression (2.69 ± 3.19) levels were low, with minimal loneliness (10.02 ± 3.92). Social support was moderate (63.11 ± 15.69), and resilience was strong (38.42 ± 6.43). Nearly half of the participants (48.2%) had poor sleep quality. Architectural features influenced mental health, with larger yard spaces improving social support, while gardens had a negative correlation due to maintenance. Single-story homes with accessible layouts and south/east-facing living rooms improved mental health. Larger doors were linked to poorer sleep quality. Conclusions: Positive architectural designs, including accessible bedrooms and favorable orientations, enhance mental health for the elderly, supporting aging in place.

1. Introduction

A significant increase in older adults is being seen worldwide [1]: A WHO study predicts that the percentage of older people worldwide will be 12% by 2030 and 16% by 2050. By 2030, there will be 1.4 billion people aged 60 or older [2]. A report by the WHO reveals that the South-East Asia region is witnessing a rapid aging process. In 2017, 9.8% of people were 60 or older, but by 2030, that number is projected to increase to 13.7% and 20.3%. Thailand is one of the fastest-aging countries in the world, with the proportion of people aged 60 and over expected to rise from 13% in 2010 to 33% by 2040 [3]. Currently, most of the elderly in Thailand live in rural areas. There are approximately 5 million (59.89%) Thai elderly people living in non-municipal areas representing rural areas [4].

The WHO has introduced “healthy aging” with the growing aged population. This term refers to maintaining the functional capacity needed for well-being in old age. Healthy aging applies to everyone and aims to create opportunities for individuals to live according to their values. The goal of this process is to optimize functional ability. An individual’s functional ability is determined by their intrinsic capacity, their surrounding environment, and their interactions within that environment.

Environments, including homes, communities, and broader society, significantly shape what older individuals can do and achieve. The environment that people live in affects healthy aging by influencing opportunities, choices, behavior, and the overall experience of older individuals [2]. Environments are linked to the concept of “Aging in Place” (AIP), which addresses the challenges associated with population aging [5]. AIP originated from the understanding that older adults have a preference for maintaining their independence in their own homes [6]. Regardless of age, money, or ability, AIP is the capacity to live safely, independently, and happily in one’s own home and neighborhood [7]. A report from the US highlighted the four main obstacles identified at the first International Conference on Rural Aging that affect aging in place: health, caregiving, housing, and transportation [6]; of these challenges, health emerges as the primary concern in the context of aging in place. Beyond simply being free of disease or physical limits, health can be described as a state of overall physical, mental, and social well-being [2].

When it comes to the mental health of older adults, numerous challenges, such as depression [8], anxiety [8], and loneliness [9] are major mental health concerns among the old; on the contrary, resilience [10,11] and perceived social support are crucial for older adults to effectively cope with various types of stressful life events and other adversities in a positive manner.

Research conducted worldwide has demonstrated the significant impact of home design. These studies show that home design significantly affects mental health. For example, a study in Malaysia found that older adults’ mental health is greatly influenced by their perceptions of environmental quality and accessibility [12]. Similarly, a study conducted in London suggested that certain aspects of the built environment are associated with poorer mental health outcomes [13]. Previous studies have also established a connection between home design and mental health. A survey in the UK found a correlation between residing in poorly maintained houses and experiencing negative mental health outcomes [14]. In Shanghai, China, a study indicated that the housing environment significantly affected depressive symptoms [15]. Additionally, a study on bathing customs in Japan found that providing older individuals with a safe bathroom could significantly lower their risk of experiencing anger, anxiety, and depression [16]. It was discovered that housing characteristics, such as having proper air conditioning, were highly related to sleep quality [17]. Moreover, individuals who were unhappy with their overall home conditions reported increased degrees of loneliness, making housing satisfaction the most important predictor of loneliness [18]. Despite these findings, which are primarily focused on urban settings, research on rural contexts is still lacking. Older people in rural locations may experience unique challenges because of their unique dwelling structures, limited access to infrastructure, and stronger emotional ties to their houses.

As mentioned earlier, the design of one’s home has a significant impact on the mental well-being of older adults worldwide. However, the concept of “home” holds even greater significance among the elderly in Thailand. A study conducted in Thailand revealed that the time that older people spend at home is 80% to 90% [19]. Although global urbanization is increasing, Thailand’s rural population has decreased from 38 million to 34 million between 2010 and 2021, but it still makes up 48% of the total population [20]. A study in Northern Thailand found that in rural areas, “home” includes not only a dwelling but also work and shared spaces [21]. This suggests that the attachment and influence of “home” among elderly individuals in rural Thailand can be even more profound.

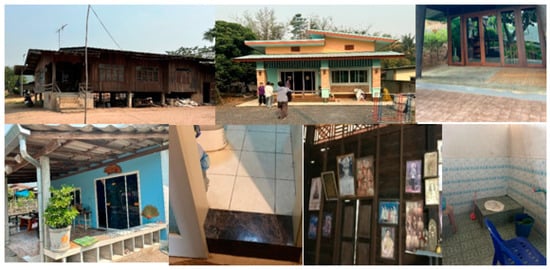

In Thailand, dwellings in rural areas differ from those in urban areas. Climate, culture, and religion all have an impact on northern Thai traditional homes, which have the following traits: First, to prevent humidity and vermin and to encourage air circulation, traditional Thai homes are normally constructed on elevated platforms, which are 1–2 m above the ground [22]. Second, steeply sloping roofs are a feature of traditional Thai homes to increase ventilation and drainage [23]. Large windows, open floor plans to improve ventilation are common design elements that are appropriate for the hot and muggy weather. Nevertheless, the main building materials are eco-friendly, locally obtained materials that are well suited to the tropical climate, such as teak wood, bamboo, and palm leaves [22]. Lastly, to facilitate community living, traditional Thai homes usually feature open floor plans with fewer clearly defined room boundaries [22]. Terraces and courtyards are vital living areas for entertaining and cooking. A collection of images in Figure 1 shows typical elements of traditional Thai homes. They exhibit the typical floor plan, raised construction, open interior space, sloped roof design, and use of traditional building materials.

Figure 1.

Pictures of traditional Thai houses.

According to research, home design has an impact on the mental health of older people worldwide. However, there is not much research that concentrate on aging-in-place home designs in rural Thailand. It is necessary to research the housing needs of elderly people in rural Thailand to support them. This study investigates the effects of home design on the mental health of senior citizens in rural Thailand. Enhancing dwelling designs to better assist their mental health is the aim.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reaearch Area and Data Collection

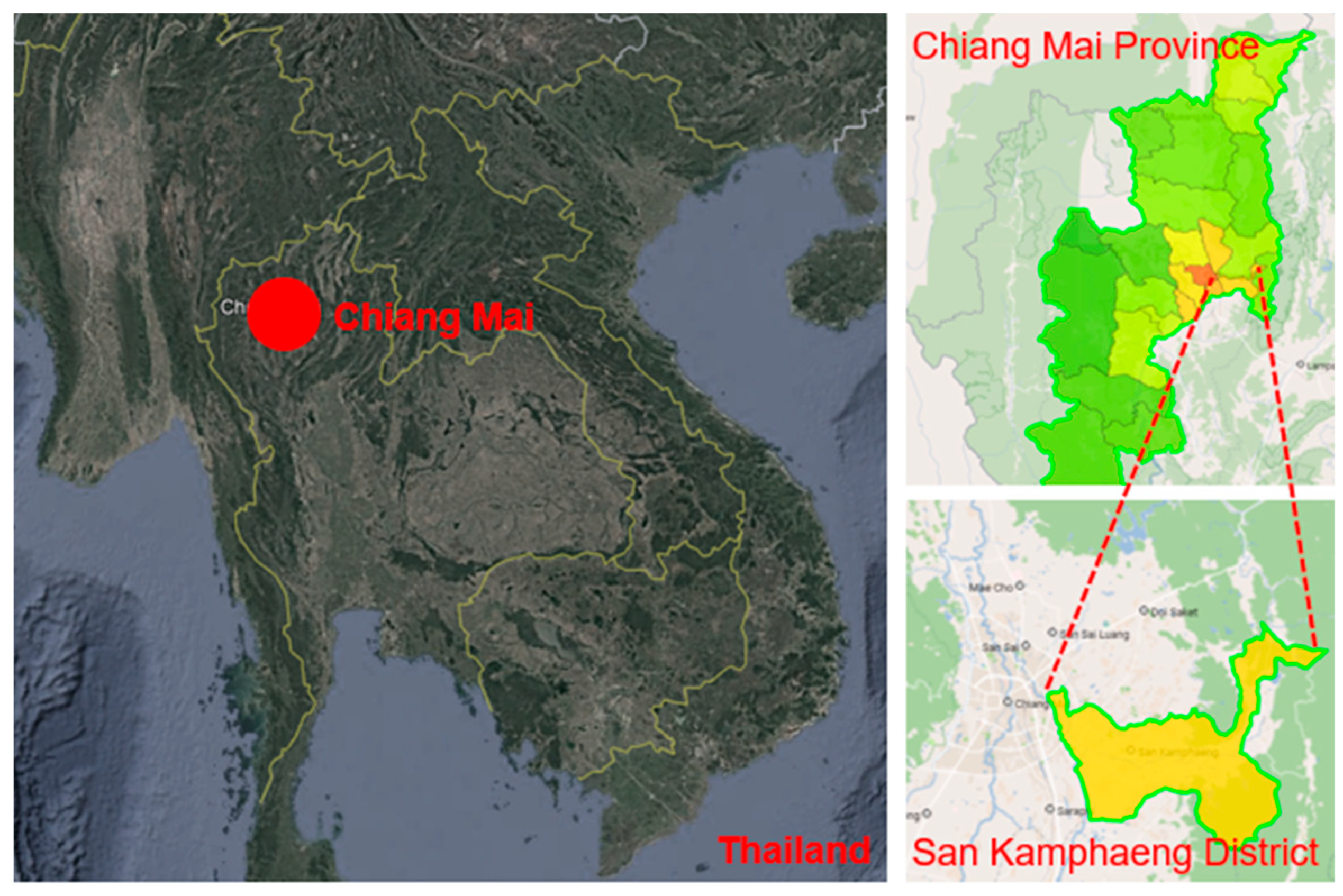

This study used a cross-sectional survey to examine the correlation between home design and mental health outcomes among older adults living in ChiangMai. All samples were collected on site in Ontai and Rongwuadang of San Kamphaeng district, Chiangmai province, Thailand, from March to May 2024. During the data collection process, two community volunteers helped us contact volunteer participants. The author, one general research assistant, and two Thai-speaking research assistants, guided by the volunteers, visited the participants’ homes to measure the houses and assist participants in filling out the questionnaires. Figure 2 is a map [24] of the research area.

Figure 2.

Map of research area.

2.2. Sample Size

The sample size was calculated with the odds ratio of 3.47 collected from the previous research about the association between housing environment and depressive symptoms among older adults [15]; convert the odds ratio 3.47 to r with excel; calculate sample size with correlation and achieve the sample size of 72; the final sample size is 80 older adults (from 72 + 72 × 10%).

Correlation sample size calculation: Total sample size required to determine whether a correlation coefficient differs from zero.

Type I error rateα (two-tailed) = 0.05,

Type II error rate β = 0.20

r = 0.3244

Standard normal deviate for α = Zα = 1.9600.

Standard normal deviate for β = Zβ = 0.8416. C = 0.5 × ln[(Ur)/(1−r)] = 0.3366.

Total sample size N = [(Zα+ Zβ)/C]2 + 3 = 72.

10% were added to the calculated result, 72 × (1 + 10%) = 80

We included Thai individuals aged 60 or older who could communicate in Thai and lived independently in rural Chiang Mai, without children or individuals under 60 in the household, and with a Barthel Index score of 12 or higher indicating self-sufficiency. Only one participant per household was included if multiple individuals met the criteria. Exclusion criteria included individuals diagnosed with dementia or schizophrenia, as well as those with uncorrected hearing or visual impairments.

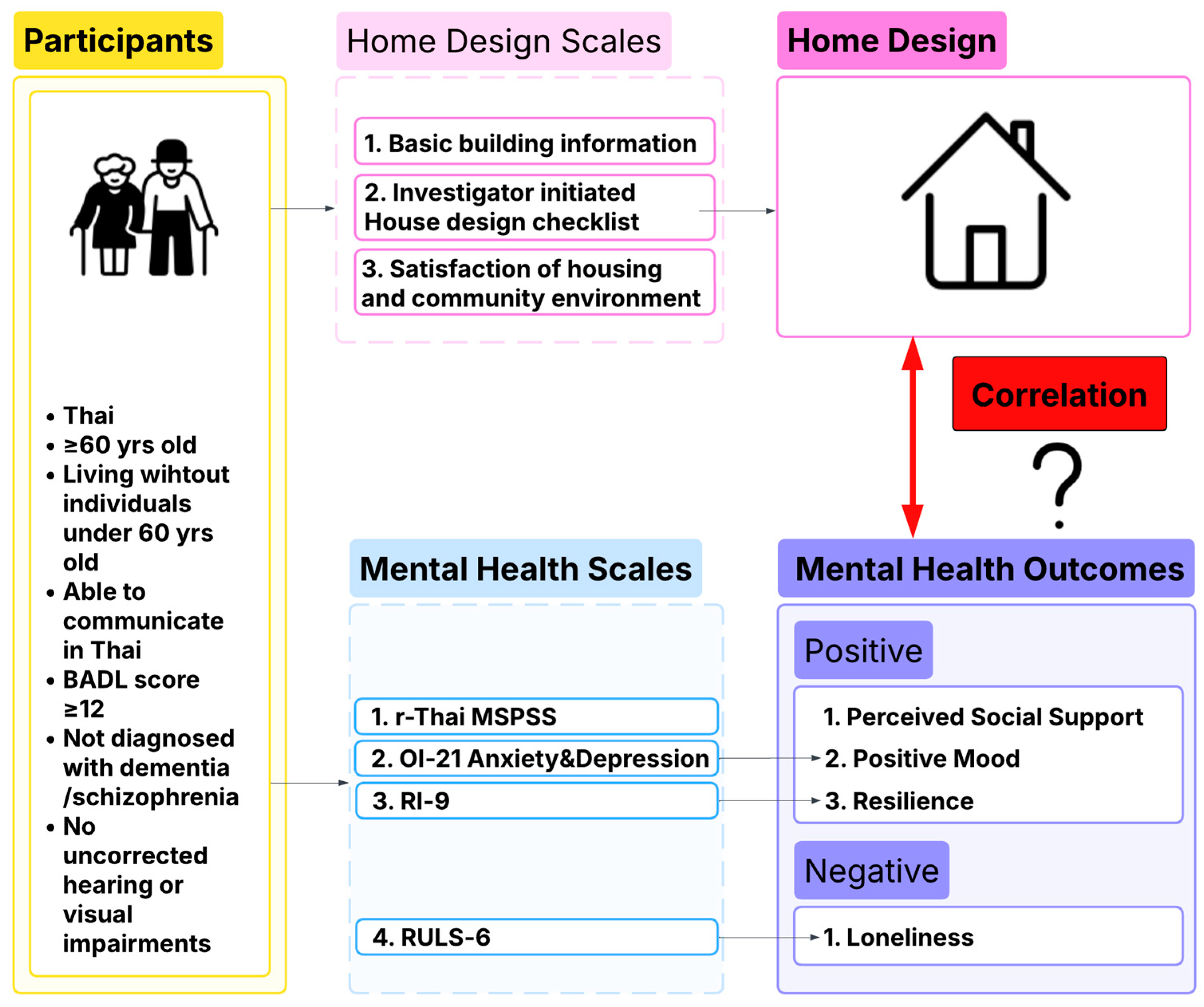

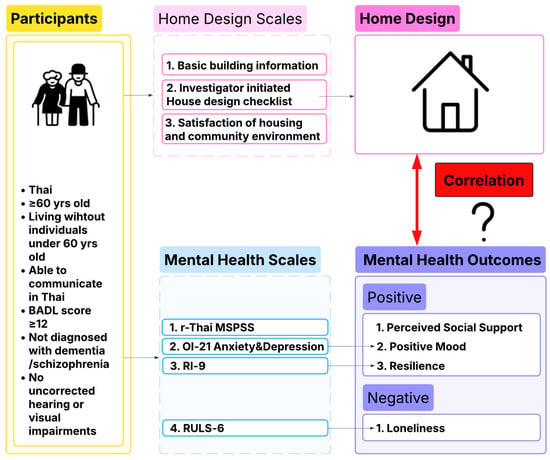

2.3. Research Framework

Figure 3 presents the framework of this study, illustrating the participants, mental health scales, architectural home design assessment tools, and the aspects they measure. Finally, the results of the architectural home design assessments and mental health measurements are compared in order to identify potential correlations between the evaluated architectural features and the mental health status of the surveyed older adults.

Figure 3.

Research framework.

2.4. Demographic Data of Participants

Demographic data of participants were collected including gender, marital status, income level, age, income resource, living arrangement, educational level etc.

2.5. Satisfaction of Housing and Community Environment

There are two sections in this questionnaire, one is to measure the satisfaction of the community environment, another is about housing satisfaction. Participants will obtain 1 score when they tick the “yes”; the total score is 11 in the housing satisfaction part, and 12 in the community satisfaction part. The higher the score, the higher the satisfaction level indicated. This questionnaire was developed by the investigator and was tested for content validity by 3 experts: geriatrician, architect, and occupational therapist, and was tested for reliability with 20 elderly people, with Cronbach’s alpha over 0.7.

2.6. Basic Building Information

Basic information about the house was collected: age, total area, yard area, ceiling height, wall color of living room, number of stories, structure type, and house type. This is developed by the investigator and will be tested for content validity by 3 experts: a geriatrician, an architect, and an occupational therapist.

2.7. Investigator Initiated Housing Design Checklist

This questionnaire is generated from a “universal design standard” and two design guidelines for housing for the old: “Guidelines for a suitable and safe environment for the elderly” [25], and “Managing an environment suitable for the elderly” [26]. They are both about the detailed design attributes for setting up an environment suitable for daily life that does not cause harm to the elderly, which covers housing and public places.

Houses are separated into the living room, bedroom, bathroom, kitchen, and entry in these three documents, and each area is subject to restrictions about comfort, accessibility, and safety. Additionally, two evaluation aspects—“whether there are plants” and “whether the yard is fenced”—have been added to the descriptions because suburban homes in Thailand normally have a yard. There are 36 items in total. After collecting the data, the result will be checked for whether the result fits the design guidelines. This is developed by the investigator and content validity will be tested by 3 experts: geriatrician, architect, and an occupational therapist.

2.8. (Revised) Thai Version of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (r-Thai MSPSS)

MSPSS [27,28] is a 12-item measurement to find out one’s perceived level of social support. This scale consists of twelve items with a scale ranging from 1 point, meaning ‘very strongly disagree’, to 7 points, meaning ‘very strongly agree’. A higher total score indicates higher perceived social support. The internal consistency of this measure is satisfied. In the student group, α was 0.91 overall, with 0.91 for significant others, 0.83 for family, and 0.86 for friends. In the clinical group, the overall Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87, 0.84 for significant others, 0.85 for family, and 0.74 for friends.

2.9. Outcome Inventory-21(OI-21)

Outcome Inventory-21 [29] a self-rating tool designed to measure anxiety, depression, somatization, and interpersonal difficulties (Eng–Thai version). The final OI, which had 21 items. The questionnaire consists of 21 items: There are six (item 3, 7, 9, 11, 15, and 20) in the anxiety subscale and five (item 2, 5, 14, 18, and 21) in the depression subscale. With a five-point Likert scale that ranges from 1 (never) to 5 (almost usually), participants score their experiences. Higher scores indicate a higher level of symptoms. The OI-21 demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties. The overall Cronbach’s alpha for the OI-21 was 0.92. The subscales also exhibited good internal consistency, with α values of 0.83 for anxiety and 0.83 for depression. In this research, only the anxiety sub-scale and depression sub-scale will be included.

2.10. 9-Item Resilience Inventory (RI-9)

RI-9 [30] was designed to test how much an individual is likely to recover well after facing setbacks or problems (Eng–Thai version). This measure consists of 9 five-Likert choices, resulting in scores ranging from 9 to 45. The response format consists of five options, where “1” indicates that the statement “does not describe me at all” and “5” indicates that it “describes my feeling very well”. Generally, a higher score indicates better resilience. The person’s reliability was found to be 0.86, while the item reliability was 0.93. Additionally, α coefficient was 0.90, indicating high internal consistency.

2.11. 6-Item Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale (RULS-6)

RULS-6 [31,32] is a self-rating tool of six items that assess the level of loneliness of individuals. The total score ranges from 6 to 24. Higher scores indicate a higher level of loneliness. This questionnaire exhibits promising psychometric properties and can be utilized in both non-clinical and clinical samples. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients range from 0.80 to 0.88, revealing a good internal consistency.

3. Results

This section is divided by subheadings. It provides a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

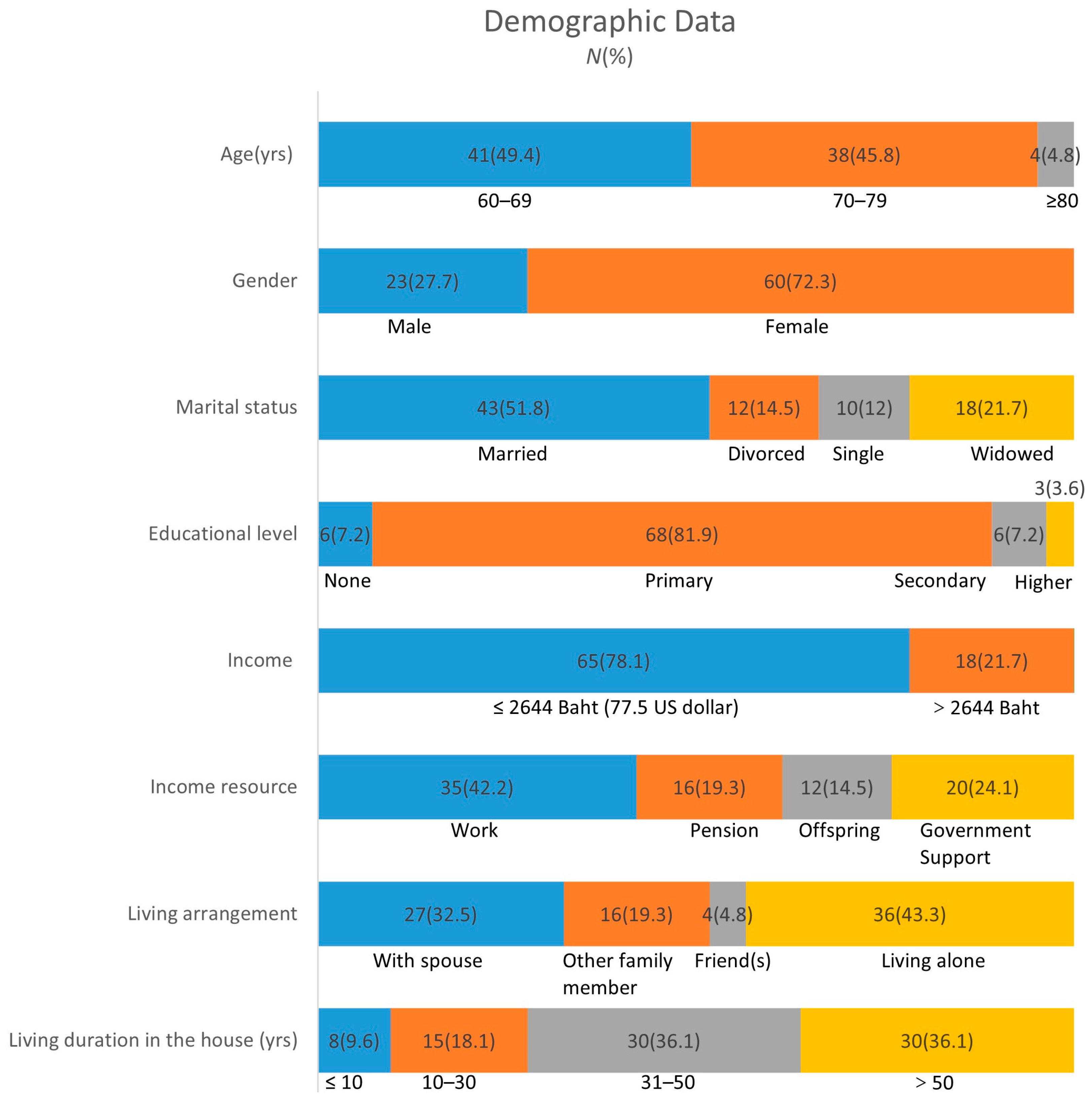

3.1. Socio-Demographic Analysis

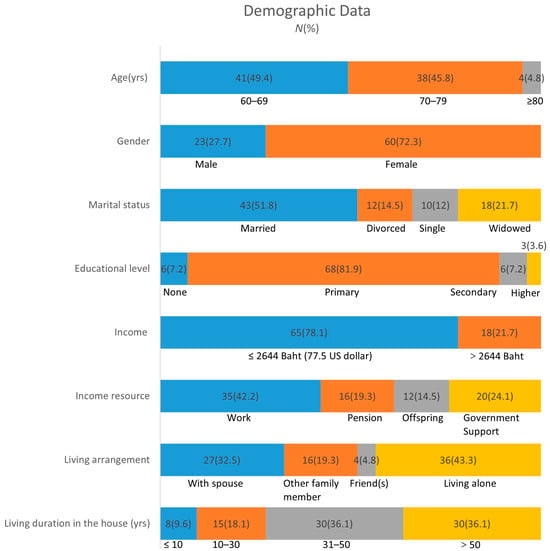

The average age of participants was 70.2 (±6.16) years, mostly 60–79 (95.2%), female (72.3%), married (51.8%), mostly received primary education (81.9%), with the majority of them earning an income lower than the poverty line of Thailand (78.1%), 42.2% of them earning an income from work; 19.3% of them are receiving a pension and the rest are receiving support from the government (24.1%) or support for children (14.5%); most of them were living alone (43.3%), followed by living with a spouse (32.5%), living with other family members (19.3), and living with friends (4.8%); most of them had lived in the house for less than or just 10 years (42.2%), followed by more than 50 years (24.1%), 10 to 30 years (19.3%), and 30 to 50 years (14.5%), as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Demographic data.

3.2. Basic Building Information Analyses

Among the houses measured, most were 31 to 50 years (33.0%), followed by 11 to 30 years (27.7%), less than or just 10 years (14.9), and over 50 years (12.8); most of them were 51 to 100 square meters (36.1%), followed by 101 to 150 square meters (25.3%), less than or just 50 square meters (19.3%), and over 150 square meters (19.3%); 34.9% of the houses had a yard with over 500 square meters, followed by 101 to 300 square meters (31.3%), less than or just 100 square meters (19.3%), and 301 to 500 square meters (14.5%); the majority of them were single floor houses (71.1%), most were modern or mix style houses (67.5%); most of them were the only house on the yard (55.4%); the story height of the most houses were over 2.6 m (77.1%); and most of the interior walls were finished (69.9%), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic building information.

3.3. Mean and Standard Deviation of Mental Health Outcomes

Among the participants in this study, the mean anxiety score was 3.51 (±3.44), and the mean depression score was 2.69 (±3.19), indicating relatively low levels of anxiety and depression. The mean loneliness score was 10.02 (±3.92), lower than the 13.64 reported in a study of long-term care facilities in Thailand [33]. The participants also reported a high level of perceived social support, with a mean score of 63.11 (±15.69), which is higher than the moderate level observed in another study conducted in government-run nursing homes in upper-northern Thailand [34]. The mean resilience score was 38.42 (±6.43). See Table 2.

Table 2.

Mental Health Outcome.

3.4. Spearman’s Rank Correlation Between Architectural Home Design and Mental Health Outcomes

All statistical correlations reported in this section were computed using Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient (ρ) due to non-normal distribution of the data.

Spearman’s rank correlation between architectural home design and mental health outcomes showed that the community satisfaction score, house satisfaction score, number of stories, living room orientation south or east, bedroom location, mirror in bedroom for self-care, toilet floor and wall color, toilet wall and sanitary color, toilet type, yard with garden/plant had significant correlations with the mental health outcomes investigated.

Among these items, a larger yard area was positively related with perceived social support, while a yard with garden or plant were negatively correlated with perceived social support; houses with more than one story and different toilet walls and sanitary colors were positively correlated with higher anxiety, while living room orientation south or east, bedroom located on the first floor, toilet on a different floor, and wall color were negatively correlated with anxiety; community satisfaction, house satisfaction, houses with more than one story were positively correlated with depression; house satisfaction score, houses with more than one story, toilet with a different toilet wall and sanitary color were positively correlated with loneliness, while living room orientation south or east was negatively with loneliness; houses with more than one story were negatively correlated with resilience, while bedroom located on the first floor was positively correlated with resilience. See Table 3. Also to provide readers with a more intuitive understanding of the rural Thai houses included in the study and the points discussed in Table 3, Figure 5 shows pictures of some of the houses been surveyed. They respectively illustrate traditional Thai houses, modern Thai houses, visual contrast at the entrance, resting conner at the entrance, visual contrast of the toilet, home decorations showing the owner’s identity or belief, and the squat toilet type.

Table 3.

Spearman’s rank correlation between architectural home design and mental health outcomes.

Figure 5.

Pictures of researched houses.

4. Discussion

4.1. Positive Architectural House Designs for Aging in Place and Positive Mental Health Outcomes

4.1.1. Perceived Social Support

Positive architectural house designs for aging in place were associated with perceived social support. Spearman’s correlation analysis revealed the presence of a yard with plants or a garden was negatively correlated with perceived social support (ρ = −0.267, p < 0.05). This result may not fully align with some earlier studies, as gardening is often associated with better well-being [35]. Yards offer a physical space that encourages family and community interaction, which can promote emotional connectedness and perceived social support. Research suggests that a lack of social interaction and support networks can lead to a sense of lower social support [36]. However, as people age, physical capabilities often decline, making it difficult for garden maintenance [37]. Most of the yards we surveyed have gardens and plants; unlike the well-maintained gardens typically found in cities, most are overgrown with grass and poorly maintained. Therefore, too much gardening work can create physical stress and limit the time older people can spend on social activities.

4.1.2. Lower Anxiety

Anxiety was linked to certain architectural elements. While living in a multi-story home showed a significant positive correlation with higher anxiety (ρ = 0.221, p < 0.05), single-story homes showed a significant positive correlation with lower anxiety. Similarly, having a bedroom on the first level was found to be related to lower anxiety (ρ= −0.238, p < 0.05). This could be because single-story homes eliminate the need for stairs and lower the risk of falls [38], reduce the anxiety of elderly individuals concerning going up and down stairs. This result aligns with a previous study which shows that viewing from the middle floor showed remarkably high negative mood states such as tension-anxiety (4.71 ± 0.9) than views from the lower floor (2.33 ± 0.71) [39]. Previous research reviews that provide older adults with independent living spaces, such as a first-floor bedroom, can help them reduce the stress of losing independency and enhance their sense of self-worth and dignity [40].

Anxiety was associated with having a bedroom on the first floor (ρ = −0.238, p < 0.05), making it easier to access and lessening the physical strain of daily life.

Living room orientation facing south or east also showed a strong correlation with lower anxiety (ρ= −0.345, p < 0.01), supporting the previous finding that south-facing rooms receive 28% more daylight, correlating with 1.9-point reductions in GAD-7 scores [41]. Exposure to natural light helps regulate biological rhythms, reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety, and improve mental health. The orientation of buildings directly affects the amount of sunlight, thus influencing the mood of the residents [42].

Toilet design was found to have significant impact anxiety.Different wall/sanitary colors increased anxiety (ρ = 0.280, p < 0.05), while different floor/wall colors decreased anxiety (ρ = −0.231, p < 0.05). High visual contrast may contribute to sensory overload, which can heighten anxiety levels in older adults [43]. As people age, their visual and spatial perception abilities may decline. When the wall and floor of a bathroom are the same color, the space may appear narrower and more enclosed, making it difficult to distinguish between the walls and the floor clearly. This can cause elderly individuals to have a blurred perception of space, increasing the risk of falls or disorientation, which in turn affects their sense of safety and mood [42].

4.1.3. Lower Depression

To our surprise, this research found that community satisfaction (ρ = −0.284, p < 0.01) and house satisfaction levels (ρ = −0.349, p < 0.01) were correlated with higher depression. Many elderly individuals may choose to show surface-level satisfaction with their current situation due to their inability to cope with life’s challenges. This avoidance attitude may mask their anxiety, depression, or feelings of loneliness [44]. The satisfaction elderly individuals have with their environment may mask their stress with social isolation and loneliness, leading to mental health issues. High satisfaction is often accompanied by a decrease in social activities, which increases feelings of loneliness [45], and higher depression.

The result also shows that living in multi-floored houses was correlated with higher depression (ρ = 0.266, p < 0.05), which means living in single-floored houses was correlated with lower depression. The relationship between housing characteristics and depression is complex and influenced by various factors. The available research does not support a direct positive correlation between living in single-story houses and lower depression [46,47]. However, as stated above, single-story homes reduce the risk of falls [38], reduce the stress of elderly individuals about going up and down stairs, and enhance their sense of self-worth and dignity [40].

4.1.4. Resilience

The study found that houses with more than one story were negatively correlated with resilience (ρ = −0.226, p < 0.05), while living in single-floored houses were positively correlated with resilience. Nevertheless, bedrooms on the first floor were positively correlated with resilience (ρ = 0.229, p < 0.05). Giving older people independent living areas, like a bedroom on the first level, might improve their sense of self-worth and relieve the strain of moving up and down the floor [40]. Single-story homes reduce physical stress and fall risk for senior citizens by eliminating the need to climb and descend steps. This indirectly increases psychological resilience by improving their sense of security and self-assurance [48]. Additionally, single-story homes make everyday tasks (such as getting to the kitchen and bathroom) easier, which lessens stress and difficulties for those with mobility impairments. Increased independence contributes to higher levels of self-efficacy, which in turn boosts psychological resilience [42].

4.2. Negative Architectural House Designs for Aging in Place and Negative Mental Health Outcomes

House satisfaction was significantly positively correlated with loneliness (ρ = 0.282, p < 0.01), supporting the idea that surface satisfaction may conceal feelings of isolation [44], High satisfaction may be accompanied by a reduction in social activities, thereby increasing feelings of loneliness [45].

Having a toilet wall/sanitary color contrast (ρ = 0.260, p < 0.05) and living in a multi-story home (ρ = 0.236, p < 0.05) were also significantly related with loneliness, perhaps as a result of sensory discomfort and confusion in poorly planned rooms. Aging can impair visual and spatial perception, making it hard to distinguish between walls and floors of the same color in bathrooms. This may create a confined feeling, blur spatial awareness, and increase the risk of falls or confusion, affecting mood and safety [42]. Single-story housing reduces the risk of falls [38], offers significant advantages for seniors by providing a safer, more accessible living environment that supports aging in place [38], while multi-story housing poses a higher risk of increased loneliness for older adults [49,50].

On the contrary, living room orientation in the south or east was negatively correlated with loneliness (ρ = −0.244, p < 0.05). In some Eastern cultures, the emphasis on orientation in Feng Shui (such as “facing south while sitting north”) not only influences architectural design but also positively impacts residents’ mental health. Favorable orientations considered auspicious can enhance psychological stability and satisfaction, especially in cultures that prioritize family harmony, thereby reducing feelings of loneliness and psychological stress [51]. Also, the orientation of buildings directly affects the amount of sunlight, thus influencing the mood of the residents [42].

5. Conclusions

This study looked at the connection between aging-in-place architectural home designs and mental health outcomes, highlighting the ways in which particular design elements can either enhance psychological benefits or have negative impacts. According to the study, specific architectural features are essential for improving older individuals’ mental health, especially when it comes to social support, anxiety, depression, and resilience.

Key findings indicate that poorly maintained gardens may increase physical stress and decrease social time of older people. Conversely, single-story homes have been demonstrated to be positively related to elderly people’s sense of safety and dignity while lowering anxiety and depression by doing away with stairs, which can be dangerous. Because natural light has a favorable impact on mood and mental health, the placement of living areas—such as living rooms facing south or east—is also quite important.

Moreover, the relationship between housing satisfaction and mental health is more complex than we initially predicted. This study reveals that depression and the satisfaction level towards the house are positively correlated. High levels of satisfaction with one’s living space sometimes conceals more profound emotions of social isolation and loneliness.

Single-story homes with bedrooms on the first floor were found to promote a higher sense of self-efficacy and independence, which in turn helped older people develop psychological resilience. This emphasizes how crucial it is to build homes that meet the mobility requirements of elderly people so they can continue to feel in charge of their living areas.

Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the design of sanitary fixtures is related to psychological resilience, and the color scheme of the bathroom is linked to anxiety. This reminds designers of the need to focus more on senior-friendly bathroom design in the future.

Last but not least, the research conclusions show that positive architectural design aims to create environments that lessen older people’s physical and psychological barriers, in addition to creating beautiful settings. These designs highlight the need for more deliberate, inclusive housing policies to support aging populations by reducing the consequences of aging, as well as improving mental health.

According to a health professional’s perspective, the architect in charge of the home’s design should also assess how older people’s living circumstances may impact mental health concerns. It is advised that accessibility, simplicity that encourages independence, and interaction be given top priority in future architectural designs. Further insight into how design might enhance the mental health and general quality of life for aging populations can also be gained by comprehending cultural context, such as the significance of building orientation in particular cultures. These findings have important inspirations for architects, legislators, and medical practitioners, encouraging them to take into account the tremendous influence that home design has on mental health outcomes and the aging process.

6. Limitations

Compared to questionnaire-based approaches, this experiment offers greater objectivity by ensuring data accuracy through direct supervision and on-site collecting. Additionally, researchers offer guidance on risky architectural elements.

Nevertheless, the study has limitations: A limitation of this study is the relatively small sample sizes, which may affect the generalizability of the results to larger populations. Future research with larger, more representative samples is needed to confirm and expand upon these findings.

Additionally, most of the surveys were completed with the help of a research assistant because most participants had lower educational levels or preferred to have the assistant read the questionnaire to them. It is customary in Thai culture to refrain from expressing unfavorable feelings in front of others [52]. As a result, experimental findings may be more optimistic than reality. Finally, Chiang Mai’s rural areas were the study’s location. Because of this, the results might not be as applicable in other cultural or geographic contexts. We intend to extend the study in the future to cover a larger geographic area, which may improve the results’ generalizability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L., P.L., N.W. and J.G.; methodology, B.L., P.L., N.W., J.G. and V.L.; investigation, B.L., P.L. and J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, B.L. and P.L., writing—review and editing, P.L., N.W., J.G., V.L. and J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of ethical committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Thailand (research ID: 0622, study code FAM-2566-0622, 5 February 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Tinakon Wongpakaran, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University for helping along with the paper writing process. Also, thanks also to Adchara Prommaban, researcher of Aging and Aging Palliative Care Research cluster, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University who assisted me with ethical approval and data analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIP | Aging in Place |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| MSPSS | Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support |

| PSQI | Pittsburgh sleep quality index |

| RULS-6 | 6-item Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale |

| RI-9 | 9-item Resilience Inventory |

| OI-21 | Outcome Inventory-21 |

| USD | US dollar |

| p-value | Probability value |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| Exp(B) | the exponentiation of the coefficient (B), or Odds Ratio |

| v.s. | Linear dichroism |

References

- Jarutach, T. Housing Conditions and Improvement Guidelines for the Elderly Living in Urban Areas: Case Studies of Four Bangkok’s Districts. J. Environ. Des. Plan. 2020, 18, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. National Programmes for Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: A Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lorthanavanich, D. Population Ageing in Thailand; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thepparp, R. Age-Friendly Communities Development in Northern Thailand: Hua-Ngum’s Experience and Implementation in Other Sub-Districts. Ph.D. Thesis, Japan College of Social Work, Graduate School of Social Welfare, Tokyo, Japan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.J. Understanding Aging in Place: Home and Community Features, Perceived Age-Friendliness of Community, and Intention Toward Aging in Place. Gerontologist 2021, 62, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dye, C.J. Advice from Rural Elders: What it Takes to Age in Place. Educ. Gerontol. 2011, 37, 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, J.; Chong, L.S.; Bundele, A.; Wei Lim, Y. Co-Designing Technology for Aging in Place: A Systematic Review. Gerontologist 2020, 61, e395–e409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luppa, M.; Sikorski, C.; Luck, T.; Ehreke, L.; Konnopka, A.; Wiese, B.; Weyerer, S.; Konig, H.H.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Age- and gender-specific prevalence of depression in latest-life—Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 136, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Victor, C.R. The prevalence of and risk factors for loneliness among older people in China. Ageing Soc. 2008, 28, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aléx, L.; Lundman, B. Lack of Resilience Among Very Old Men and Women: A Qualitative Gender Analysis. Res. Theory Nurs. Pr. 2011, 25, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmore, D.L.; Brown, L.M.; Cook, J.M. Resilience in older adults. In Resilience and Mental Health: Challenges Across the Lifespan; Litz, B.T., Charney, D., Friedman, M.J., Southwick, S.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, T.H. Perceived Environmental Attributes: Their Impact on Older Adults’ Mental Health in Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weich, S.; Blanchard, M.; Prince, M.; Burton, E.; Erens, B.; Sproston, K. Mental health and the built environment: Cross-sectional survey of individual and contextual risk factors for depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 180, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pevalin, D.J.; Reeves, A.; Baker, E.; Bentley, R. The impact of persistent poor housing conditions on mental health: A longitudinal population-based study. Prev. Med. 2017, 105, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cui, P.Y.; Pan, Y.Y.; Li, Y.X.; Waili, N.; Li, Y. Association between housing environment and depressive symptoms among older people: A multidimensional assessment. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, Y.; Hayasaka, S.; Kurihara, S.; Nakamura, Y. Physical and Mental Effects of Bathing: A Randomized Intervention Study. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 2018, 9521086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandberg, J.C.; Talton, J.W.; Quandt, S.A.; Chen, H.; Weir, M.; Doumani, W.R.; Chatterjee, A.B.; Arcury, T.A. Association between housing quality and individual health characteristics on sleep quality among Latino farmworkers. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2014, 16, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, S.; Brusilovskiy, E.; Townley, G.; McCormick, B.; Thomas, E.C.; Snethen, G.; Salzer, M.S. Housing and loneliness among individuals with serious mental illnesses. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2023, 69, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wannawong, J. Promotion of Home and Environment Modifications by Fourth Year Occupational Therapy Students for Older people in the Family. Bachelor’s Thesis, CMU, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Share of Rural Population from the Total Population in Thailand from 2012 to 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1107971/thailand-share-of-rural-population/ (accessed on 8 October 2023).

- Oranratmanee, R. Re-utilizing Space: Accommodating Tourists in Homestay Houses in Northern Thailand. J. Archit./Plan. Res. Stud. 2011, 8, 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Tachaudomdach, S.; Kaochim, T.; Sinthuboon, K. Knowledge, Preparedness, and Practices of Lanna People for Earthquake-Resistant Housing in Active Fault Zones of Northern Thailand. J. Res. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Oh, H.; Ju, S. The Characteristic of Decoration in Central Thai Traditional House. Korean Inst. Inter. Des. J. 2011, 20, 200–207. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.citypopulation.de/en/thailand/admin/50__chiang_mai/ (accessed on 8 October 2023).

- Office of the Promotion and Protection of the Elderly Office of Welfare Promotion and Protection of Children Y, the Underprivileged and Elderly. Guidelines for a Suitable and Safe Environment for the Elderly; Office of the Promotion and Protection of the Elderly Office of Welfare Promotion and Protection of Children Y, the Underprivileged and Elderly: Bangkok, Thailand, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Environmental Health DoHMoPH. Managing an Environment Suitable for the Elderly; Bureau of Environmental Health, Department of Health Ministry of Public Health: Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2015.

- Wongpakaran, T.; Wongpakaran, N.; Ruktrakul, R. Reliability and Validity of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS): Thai Version. Clin. Pr. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2011, 7, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpakaran, T.; Wongpakaran, N.; Sirirak, T.; Arunpongpaisal, S.; Zimet, G. Confirmatory factor analysis of the revised version of the Thai multidimensional scale of perceived social support among the elderly with depression. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 1143–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T.; Kövi, Z. Development and validation of 21-item outcome inventory (OI-21). Heliyon 2022, 8, e09682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpakaran, T.; Yang, T.; Varnado, P.; Siriai, Y.; Mirnics, Z.; Kövi, Z.; Wongpakaran, N. The development and validation of a new resilience inventory based on inner strength. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T.; Pinyopornpanish, M.; Simcharoen, S.; Suradom, C.; Varnado, P.; Kuntawong, P. Development and validation of a 6-item Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale (RULS-6) using Rasch analysis. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, D.W. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Pers. Assess. 1996, 66, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe Myint, K.; DeMaranville, J.; Wongpakaran, T.; Peisah, C.; Arunrasameesopa, S.; Wongpakaran, N. Meditation Moderates the Relationship between Insecure Attachment and Loneliness: A Study of Long-Term Care Residents in Thailand. Medicina 2024, 60, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puttamat, R.; Chintanawat, R.; Pothiban, L. Social Support for and Psychological Wellbeing of Older People in Nursing Homes. J. Thail. Nurs. Midwifery Counc. 2020, 35, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg, A.E.; van Winsum-Westra, M.; de Vries, S.; van Dillen, S.M.E. Allotment gardening and health: A comparative survey among allotment gardeners and their neighbors without an allotment. Environ. Health 2010, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkman, L.F.; Syme, S.L. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1979, 109, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, C.; Gatrell, A.; Bingley, A. ‘Cultivating health’: Therapeutic landscapes and older people in northern England. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 58, 1781–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabors, E.; Renfro, M.; Pynoos, J.; Szanton, S.; Sanford, J.; Stark, S. Innovations in Home Modification Research: The State of the Art. Innov. Aging 2019, 3, S635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.M.; Kang, M.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y.J.; Choi, H.; Lee, J. Psychological and Physiological Responses to Different Views through a Window in Apartment Complexes. J. People Plants Environ. 2021, 24, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnea, A.; Zairul, M. Evaluating the Impact of Housing Interior Design on Elderly Independence and Activity: A Thematic Review. Buildings 2023, 13, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landon, A.C.; Woosnam, K.M.; Kyle, G.T.; Keith, S.J. Psychological Needs Satisfaction and Attachment to Natural Landscapes. Environ. Behav. 2020, 53, 661–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. Environmental Psychology: Principles and Practice; Optimal Books: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshkowitz, M.; Whiton, K.; Albert, S.M.; Alessi, C.; Bruni, O.; DonCarlos, L.; Hazen, N.; Herman, J.; Katz, E.S.; Kheirandish-Gozal, L.; et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: Methodology and results summary. Sleep. Health 2015, 1, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.W.; Patterson, T.L.; Grant, I. Avoidant coping predicts psychological disturbance in the elderly. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1990, 178, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, C.R.; Bowling, A. A longitudinal analysis of loneliness among older people in Great Britain. J. Psychol. 2012, 146, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y. Heterogeneity in the trajectories of depressive symptoms among elderly adults in rural China: The role of housing characteristics. Health Place 2020, 66, 102449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rautio, N.; Filatova, S.; Lehtiniemi, H.; Miettunen, J. Living environment and its relationship to depressive mood: A systematic review. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2018, 64, 103–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.W. The built environment and mental health. J. Urban. Health 2003, 80, 536–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, H.W.; Iwarsson, S.; Oswald, F. Aging well and the environment: Toward an integrative model and research agenda for the future. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharlach, A.E.; Lehning, A.J. Ageing-friendly communities and social inclusion in the United States of America. Ageing Soc. 2013, 33, 110–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, M.; Ng, S. The art and science of Feng Shui—A study on architects’ perception. Build. Environ. 2005, 40, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komolsevin, R. Effective intercultural communication: Research contributions from Thailand. J. Asian Pac. Commun. 2010, 20, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).