Abstract

The traditional folk houses in Pengcheng Town preserve the architectural style of the southern part of Hebei Province and integrate local living customs and cultural traditions. These folk houses reflect the deep cultural origins of Pengcheng and the Cizhou Kiln. “Wang’s Old House” is the largest and tallest building among numerous residential settlements in Pengcheng Town. It is not only the residence of the Wang family but also the epitome of Cizhou Kiln culture. Taking “Wang’s Old House” in Pengcheng Town as an example of a location in the process of restoration, this paper uses field investigation, oral history methods, and digital technology, combined with an analysis of the overall architectural style of Handan folk houses, oral historical materials, and existing architectural sites, to carry out detailed research and prediction on the plane layout, facade modeling, construction structure, and decorative details of Wang’s Old House, in order to restore the original appearance of Wang’s Old House. This study provides valuable information on and experience in restoring traditional dwellings in the vicinity of Cizhou Kiln, so that we can have a deeper understanding of traditional dwellings’ historical and cultural connotations.

1. Introduction

With its rich cultural heritage and distinctive regional characteristics, the Cizhou Kiln has become a significant focal point for studying architecture and culture. Historic urban sites and traditional houses are the most important evidence for past lifestyles [1]. Traditional dwellings, serving as material embodiments of local cultural essence, have gradually revealed their incompatibility with contemporary developmental needs due to the passage of time and societal evolution [2]. Modern culture and society exert a profound influence on traditional cities and architecture [3]. During the process of urbanization, numerous traditional dwellings encapsulating historical memories and cultural values have vanished, placing their unique historical and cultural significance at risk of being forgotten. Previously, research on Cizhou Kiln architecture has primarily focused on four categories: production buildings, commercial buildings, residential buildings, and sacrificial buildings. These architectural types evolved in response to cultural advancements [4]. Among the residential buildings, a detailed investigation and analysis have been carried out regarding the dwellings of kiln workers, exemplified by the Zhangjialou village. However, systematic exploration of kiln owners’ living quarters has not been adequately addressed [4]. “Wang’s Old House” in Pengcheng Town stands as a representative example of such residences; however, it is now challenging to discern its original form. In domestic and international studies, extensive discussions have been made on the restoration of architectural heritage [5,6,7,8]. There are diverse viewpoints on the architectural restoration, and, meanwhile, it is proposed to carry out architectural restoration by means of digitalization [9,10,11,12]. This thesis is based on the current situation of “Wang’s Old House”; we aim to restore the house using scientific methods in order to recreate its architectural appearance and to thoroughly investigate and showcase its unique architectural style and cultural attributes. This endeavor is of substantial importance for the comprehension and understanding of Cizhou Kiln culture and its related social structures.

Oral history, as a contemporary movement, possesses its own history that spans numerous centuries. The practitioners of the modern oral history movement assert that prior to the emergence of written language, all history was oral [13]. Oral history is founded upon oral documentation, among which folk tales and legends are merely one kind. Songs and interviews, both formal and informal, are forms of oral documentation [14]. Oral history in architecture research constitutes a diversified field with at least half a century of history [15]. The utilization of oral history methods in research and writing [16], employing semi-structured interview techniques, enables people to consult their memories in an open format [17]. It can be defined as a deliberate and historically significant dialogue between two individuals regarding specific aspects of the past that are intentionally recorded [18]. Oral history methods play a crucial role in architectural scenarios, form restoration, and other aspects [19]. To mitigate the limited availability of resources for and historical records of traditional architecture in many rural places, one needs to use the oral history method [20]. Through interviews with craftsmen and current occupants of buildings, oral history can provide profound insight into the traditional appearance of structures and their cultural significance. In the process of restoring traditional houses, various factors such as the identity, background, economic status, living habits, and cultural beliefs of owners significantly influence construction practices. However, since most builders of these traditional houses have passed away, obtaining first-hand information directly poses considerable challenges. Nevertheless, current occupants and descendants often possess valuable insights into both the form and function of these homes.

Taking “Wang’s Old House” as a case study in our research on the restoration of traditional residences of the Cizhou Kiln, we conducted interviews with Wang Xinmin, Wang Zhiguo, and Wang Jieying, descendants of the Wang family, and seven current residents (Wang Xinmin, who formerly held the position of the director of Fengfeng Commercial Bureau, has long been devoted to the publicity of Cizhou Kiln culture. “Wang’s Old House” was his former abode, namely the ancestral home. Wang Jieying has been constantly concerned about Cizhou Kiln culture for a long time. Wang Zhiguo and Wang Jieying are a married couple, and Wang Zhiguo and Wang Xinmin are brothers. All three have published articles on the “Microscopic Fengfeng” official account, dedicated to the publicity and promotion of Cizhou Kiln culture. Moreover, they all have had the experience of living in the old residence of the Wang family and have retained memories of the courtyard space). Drawing upon their memories of their family heritage and experiences associated with the old house allowed them to provide us with rich historical narratives concerning its architectural styles and familial context. The recollections shared by these individuals not only compensate for gaps found in written records or visual documentation but also offer invaluable references that enhance our understanding during the restoration of “Wang’s Old House”.

2. The Porcelain Industry in Pengcheng: The Origins of Residential Architecture of the Cizhou Kiln in Pengcheng Town

The Pengcheng porcelain industry has undergone gradual development since the Yuan Dynasty. After centuries of evolution, by the 1970s and 1980s, Pengcheng porcelain gained international acclaim and became synonymous with the Cizhou Kiln [21]. Constructed in the late Qing Dynasty, “Wang’s Old House” has withstood a century of wind and rain; it still partially retains its former splendor and bears witness to the entire trajectory of the Pengcheng porcelain industry, from prosperity to transformation.

The rulers of the Yuan Dynasty placed significant emphasis on the development of handicrafts, encouraging craftsmen from the Central Plains to engage in production activities. This initiative laid a solid foundation for enhancing the ceramic skills of workers at the Cizhou Kiln. Furthermore, the large-scale population migration during the Ming Dynasty introduced abundant human resources and facilitated diverse cultural intermingling within Pengcheng [22,23]. Thanks to its advantageous geographical location, abundant natural resources, and supportive social policies, Pengcheng Town emerged as the central firing area for Cizhou wares during the Ming Dynasty. The thriving kiln industry not only fostered the prosperity of the porcelain sector but also attracted numerous artisans who settled in this region. Their presence contributed to an increase in residential construction within Pengcheng Town. According to records from Magnet County, a catastrophic earthquake struck Pengcheng Town in the 10th year of Daoguang during the Qing Dynasty (1830), resulting in the near-complete destruction of all houses. During the post-disaster reconstruction process, newcomers who relocated from outside the region significantly influenced local construction techniques. These individuals utilized concepts from the architectural style of Beijing’s and Shanxi’s grand courtyards. Residents adeptly repurposed discarded cage helmets, integrating them with bricks and stones to create regional architecture with distinct local features [24]. The residential settlements that developed around the Cizhou Kiln exhibit a layout design, architectural structure, and selection of building materials that profoundly reflect the unique regional cultural connotations and distinctive characteristics of their respective eras.

3. Background and Current Status of “Wang’s Old House”

3.1. The Background of the Porcelain Industry

The porcelain industry in Pengcheng Town experienced significant prosperity, leading to the emergence of a group of merchants who dominated both the production and capital markets associated with the Cizhou Kiln in this region. Historical records indicate that the Wang family was among the first of ten kiln owners during the late Qing Dynasty and early Republic of China. Prior to the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, they were recognized as the wealthiest family in Pengcheng, with their porcelain products inscribed with “Fuyuan Wang family made” [25]. The ancient kiln sites of Futian and Yandian, preserved within Pengcheng Town, were part of the “Wangjiayao” in Fuyuanli before the Second Sino-Japanese War. The “Wang Family Old Residence” stands as the largest and most architecturally significant traditional dwelling currently extant in Pengcheng Town, showcasing distinctive characteristics. This residence not only served as a home for the Wang family but also represents a microcosm of that era, serving as a testament to the prosperity of Pengcheng.

3.2. Complex Historical Changes in the Building

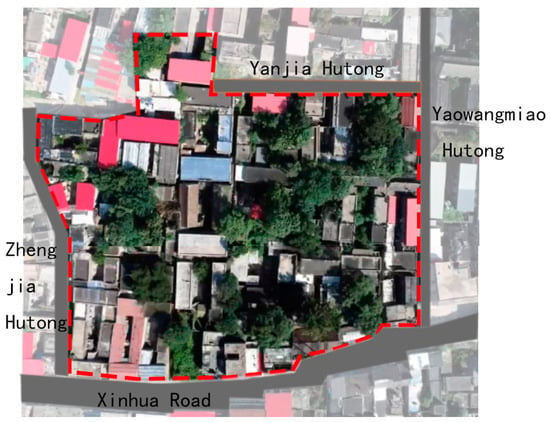

“Wang’s Old House” was constructed in 1830 during the Daoguang period of the Qing Dynasty and is situated in Pengcheng Town, Fengfeng Mining District, Handan City. This town is renowned for its profound historical heritage and abundant cultural resources, possessing significant historical value and tourist appeal. The mansion is located to the north of Wenchang Pavilion. To its east lies Yaowangmiao Hutong, while Zhengjia Hutong borders it on the west. To the north is Yanjia Hutong, with Xinhua Road to the south. The overall layout of “Wang’s Old House” is rectangular, featuring a bulge at its northwest corner. It measures approximately 110 m from east to west and 70 m from north to south, encompassing an area exceeding 8000 square meters (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Since 1945, ownership of “Wang’s Old House” has transitioned from private hands to public ownership. In recent years, due to government efforts aimed at exploring and preserving the culture associated with the Cizhou Kiln—alongside active collaboration with the descendants of the Wang family—the mansion has regained prominence within Pengcheng Town. It has re-entered public consciousness as a vital window into showcasing the region’s history and culture.

Figure 1.

Location of “Wang’s Old House”.

Figure 2.

General layout of “Wang’s Old House”.

3.3. Serious Damage to Building Form and Structural Details

In recent years, the ongoing process of urbanization has led to spontaneous modifications of “Wang’s Old House”, a traditional residence, primarily driven by human factors. These alterations have resulted in significant damage to the structure. Portions of the property have been demolished, reconstructed, or expanded upon, thereby introducing modern living requirements and architectural styles that threaten the original value of this traditional house. These residences’ original form and layout have been irrevocably altered; single-family homes have been converted into multi-family units, while courtyards that once served as inward-facing private spaces have been transformed into open and shared external areas [26]. Additionally, the original green-tiled double-slope roofs have been replaced with flat roofs, and various detailed decorative elements have suffered varying degrees of deterioration. Although these renovated traditional houses may fulfill contemporary living needs, disparities among residents’ lifestyle requirements, aesthetic preferences, and economic capabilities result in renovations characterized by randomness and individualization. This variability has ultimately impacted the overall aesthetic coherence of the buildings [27].

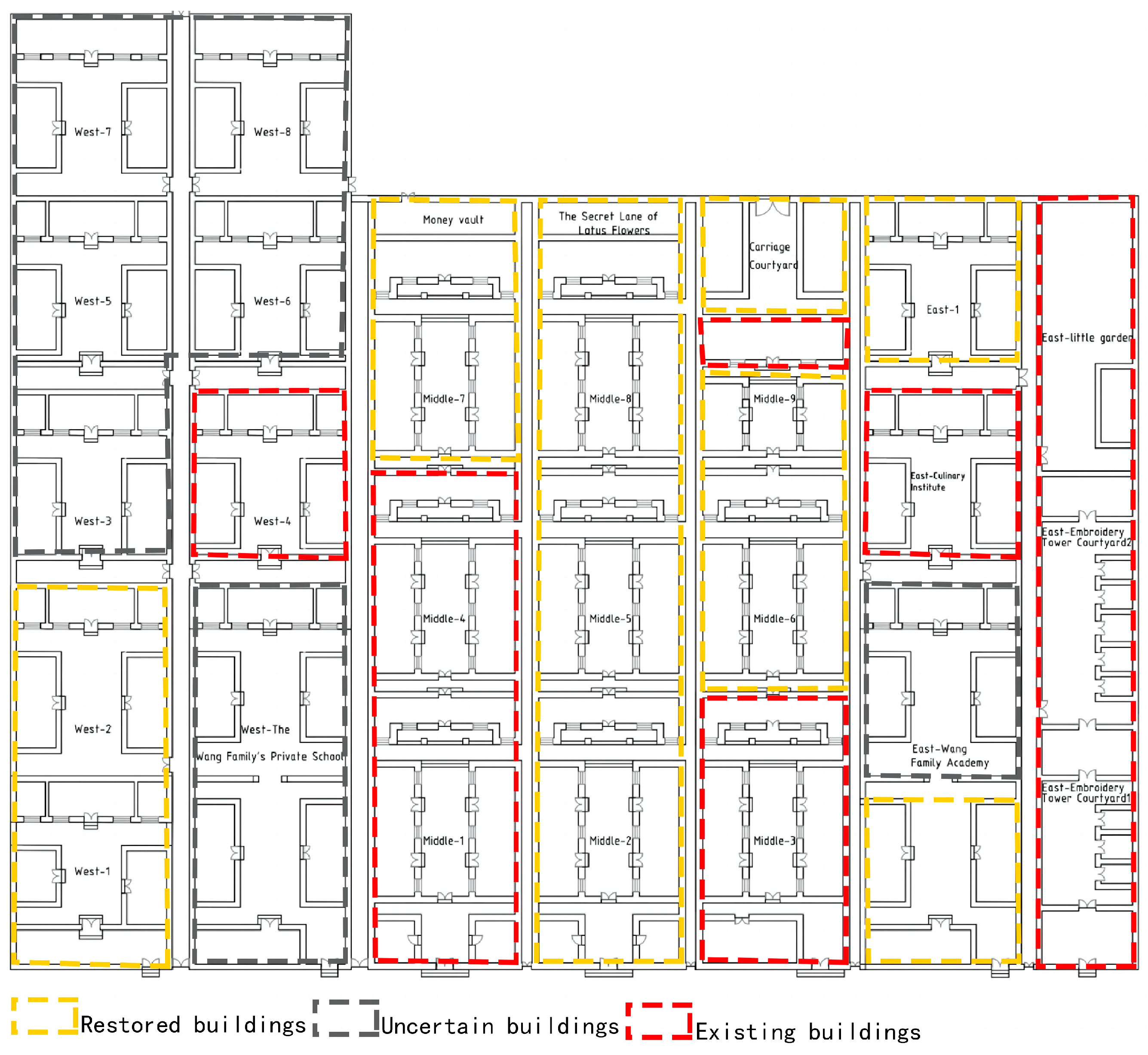

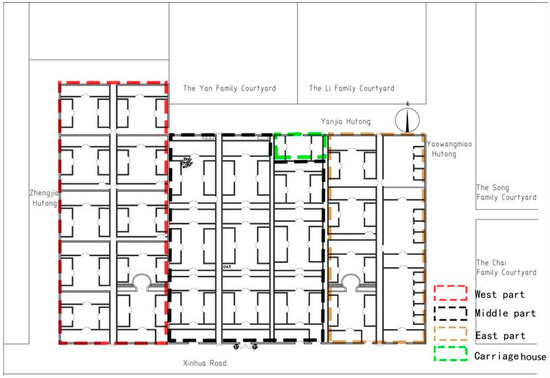

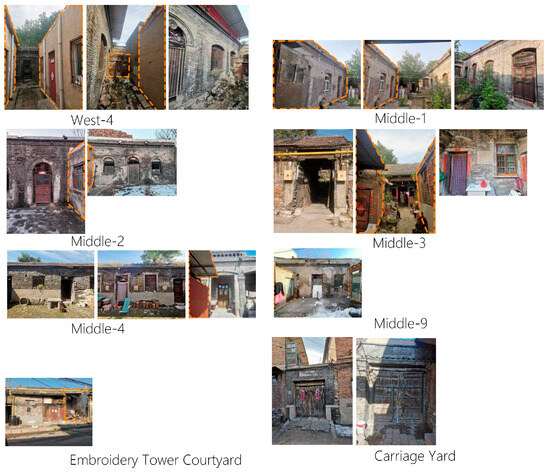

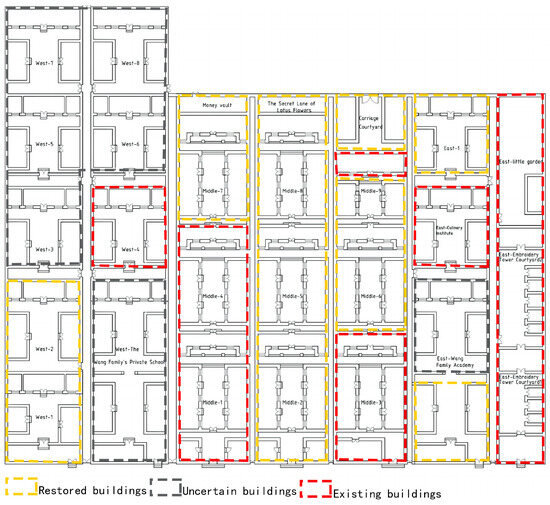

“Wang’s Old House” is categorized into four distinct sections: the west wing, the central area, the east wing, and the carriage house. This classification is based on the schematic diagram provided by the descendants of the Wang family (Figure 3). During field research, comprehensive mapping and photographic documentation of the existing mansion were conducted (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Layout diagram of “Wang’s Old House”.

Figure 4.

Current condition of “Wang’s Old House”. (The orange parts are newly built structures.).

4. Oral Practices in the Restoration of “Wang’s Old House”

4.1. Restoration of the Architectural Form of “Wang’s Old House”

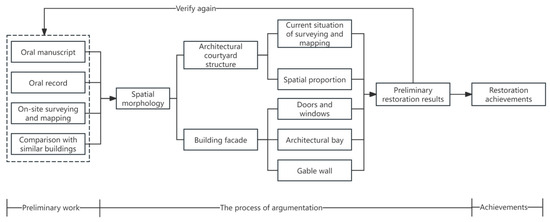

The spatial configuration of a house is intricately linked to its living culture, serving not only as a residence for its inhabitants but also as a significant site for management activities. The information regarding the restoration of “Wang’s Old House” has been derived from an aggregation of data concerning the general characteristics of traditional houses in Handan, oral accounts from occupants and users of these traditional dwellings, and field mapping research conducted by the author. These data and materials need to corroborate each other before the building can be speculated and restored (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Reconstructed structure diagram.

4.1.1. Restoration of the General Building Plan

Comprehensive interviews with residents garnered valuable insights, and the survey data were meticulously recorded and analyzed in detail [28].

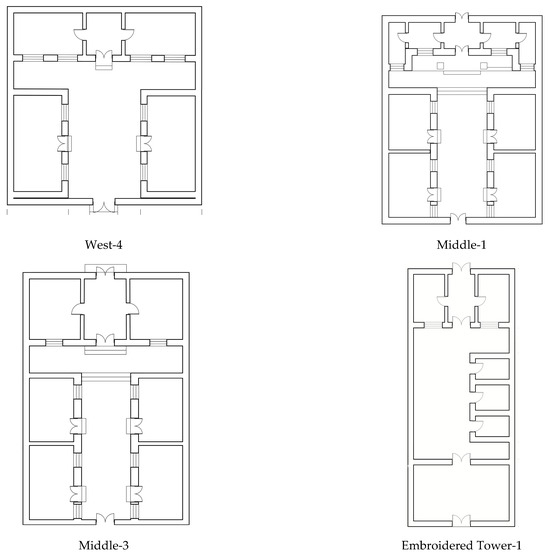

During the on-site investigation, the preservation status of the three architectural complexes located in the eastern, central, and western sections of “Wang’s Old House” was assessed. Each complex contains buildings that are relatively well-preserved. Specifically, these include the west-4 courtyard, middle-1 courtyard, middle-4 courtyard, middle-3 courtyard, east-silk room 1 courtyard, east-silk room 2 courtyard, and east-kitchen courtyard. In the western complex, some structures retain their original complete walls and spatial layouts; however, most have been newly constructed with spatial forms that lack a connection to the original layout. Consequently, this area has suffered a loss of integrity. In contrast, within the central complex—specifically in the middle-8 and middle-6 courtyards—the original positions of side rooms can be clearly identified through existing walls. Nevertheless, the spatial relationships among other buildings appear disordered. Notably problematic are the middle-2 and middle-5 courtyards; their architectural styles and spatial scales diverge from those of surrounding original structures to such an extent that it is challenging to ascertain whether any original buildings were present. The eastern complex exhibits a relatively high degree of spatial recognition. Most buildings effectively demonstrate their original wall positions and possess spaces that could potentially be restored. However, for certain structures within this complex, there exists insufficient evidence to substantiate their spatial configurations, rendering it impossible to determine whether they reflect an authentic layout from earlier periods (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The existing floor plan of “Wang’s Old House”.

According to the oral accounts provided by Wang’s descendants, “the layout of the residence is designed such that the central courtyard serves as the core of the master’s dwelling; on the east side lies the Embroidery Tower Courtyard; to the west is situated the West Crossing Courtyard, while adjacent to the north is the Carriage Courtyard”. In the field mapping, the horse road between different parts and some of the architectural ruins that have been preserved until now can be observed. Aisles interconnect these areas and are skillfully separated by pinched gates. Based on this information, it can be reasonably inferred that “Wang’s Old House” was structurally divided into four distinct areas using these aisles: namely, the western area (the Western Crossing Courtyard), the eastern area (the Embroidery Tower Courtyard), the central area (the Middle Yard of the Owner’s Residence), and, finally, in the northern section, the Carriage Yard.

The layout of the western building complex exhibits a chaotic characteristic. Only one courtyard retains its original site, and only a small portion of the original wall positions can be discerned. Most of the buildings have vanished after a century of transformations, supplanted by new construction complexes (Figure 7). According to oral histories from descendants of the Wang family, “the west-spanning courtyard comprises eight compounds, including a private school and the living quarters of the butler and the accountant. A horse road bisects the courtyard into eastern and western sections, each compound oriented towards this thoroughfare”. However, these layout features are challenging to identify in contemporary reality.

Figure 7.

Current status map of buildings in the western region.

Comprehensive research was conducted on the relatively well-preserved west-4 courtyard to gain a deeper understanding of historical architectural styles. The layout of west-4 exemplifies a typical triple courtyard design. The inner courtyard measures approximately 5 m in width (east–west) and 10 m in length (north–south). The distance between the main house and its adjoining compartments is maintained at 2 m. This configuration promotes spatial transparency and ensures privacy for its occupants. The main house extends 13 m from east to west and spans 4 m from north to south, featuring five rooms, contributing to its spaciousness and dignified appearance. The side house measure 8 m in length (north–south) and 4 m in width (east–west), mirroring the main house’s five-room arrangement; together, they constitute the core space of the courtyard. The layout of the entire courtyard is symmetrical. There is a gate on the south side, connecting the courtyard and the walkway. The descendants of the Wang family have also highlighted the distinctive arrangement of the private school. According to their description, this private school comprises two courtyards; the first includes reversely-set house and side houses, separated from the second courtyard by a wall. The second courtyard contains a main house as well as east and west side houses, exhibiting a layout that closely resembles that of a butler’s compound. The granary and storehouse located at the northernmost side can only provide information regarding the position of the courtyard gate, while the configuration of the buildings cannot be ascertained through intuitive methods. In the western area, it is not feasible to directly identify which original structures have been preserved to this day based on aerial photographs and their external appearances. The current condition of these buildings diverges from the floor plan of the Wang family’s ancestral residence provided by its descendants, resulting in a lack of direct evidence for restoring such spaces. The overall restoration process is conducted by integrating on-site survey data, drone aerial imagery, oral historical accounts, and analogies with similar structures; however, there remains a need for further enhancement in terms of restoration fidelity.

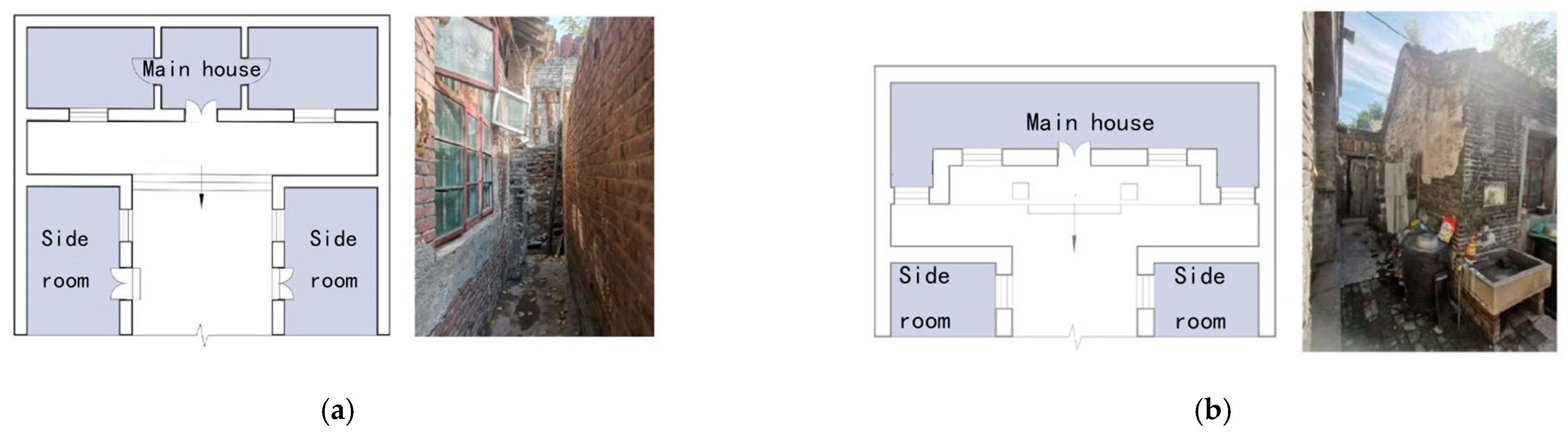

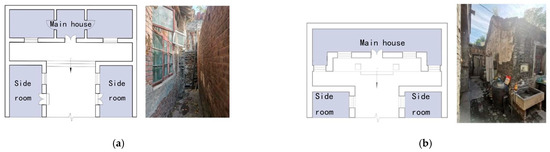

“In the center, there are three groups of nine gates that connect, with horse paths linking each group and gates separating them. The structural design of these three groups of nine-gate phases is fundamentally similar; however, notable differences exist”. A descendant of the Wang family also described that “the eastern group of nine-gate inter-photography features the Xunmen at its easternmost point”. Among these courtyards, middle-3 and middle-1 are relatively well-preserved. The courtyard of middle-1 has a width of 4 m and a depth of 11 m from north to south. Before entering the main house, one must ascend three steps to reach a platform, followed by two additional steps to access the main house. The dimensions of the main house measure approximately 12 m in length (east–west) and 5 m in width (north–south), featuring a lobby at its center with rooms arranged on either side. Each side house extends 11 m in length (north–south) and 4 m in width (east–west) (Figure 8b). This layout design, referred to as “liangshuaixiu”, adeptly accommodates local natural conditions and effectively fulfills residents’ practical needs—representing an exemplary fusion of traditional architectural wisdom with modern living requirements [29,30]. The north corridor of middle-3 is not in the form of “liangshuaixiu” (Figure 8a).

Figure 8.

The planar positional relationship between the main house and the wing rooms: (a) the main room’s platform projects and connects with the side rooms; (b) the main house and the side rooms are separated to form a passageway.

Through aerial images captured by drones, it was observed that the central building complex features a three-entrance courtyard layout. The No. 1 and No. 4 courtyards consist of existing buildings, while the No. 7 courtyard to their north retains the original positions of the building walls, allowing for a rough inference of the original building layout. The No. 3 courtyard also contains existing building, and its northern counterpart has remnants of what was once the main house within that courtyard. The original wall positions of rooms on both the east and west sides are still discernible. The buildings in other areas of the central part exhibit a rather disordered arrangement. It is challenging to ascertain the construction timeline and courtyard layout solely from aerial photographs and visual appearances. The current condition of the existing structures diverges from the floor plan of “Wang’s Old House”, as provided by their descendants. There is a lack of direct evidence to substantiate the restoration of such spaces; however, insights into the courtyard space and layout in other regions can be inferred and reconstructed based on the remaining buildings (Figure 9). Utilizing data gathered from on-site surveys, drone-captured aerial images, oral history accounts, and comparisons with similar edifices, it can be deduced that the original configuration was likely a three-entrance courtyard.

Figure 9.

Current status map of buildings in the middle region.

The image distinctly illustrates the functional zoning in the eastern area, which is divided into two sections by a horse path (Figure 10). According to oral accounts from the descendants of the Wang family, “The eastern part comprises the kitchen yard, embroidery building, Wang family study, and back garden. The embroidery building on the east side is a two-story structure featuring high windows on its facade”. Aerial images captured by drone reveal that the existing site of the eastern kitchen yard within the western building complex retains original layout characteristics of both adjacent north and south courtyards. During field surveys, it was observed that the embroidery building complex follows a partial two-courtyard layout: on the southern side of the first courtyard lies a back house, while to its east stands a small five-bay room. The courtyard itself measures 4 m in width (east–west) and 11 m in length (north–south). Upon passing through the first hall into the second courtyard, one finds a three-bay room situated on its eastern side alongside an arrangement for main living quarters. Some buildings have undergone alterations in their spatial configurations due to subsequent additions and renovations; thus, their current state diverges from floor plans provided by Wang family descendants regarding their ancestral residence. There exists insufficient direct evidence to substantiate restoration efforts for these spaces. By comprehensively employing research methodologies—including field survey data, aerial imagery, and oral histories—to cross-verify findings with one another, we construct a spatial restoration model for the eastern courtyard of the Wang family’s old residence.

Figure 10.

Current status map of buildings in the east region.

The Carriage Courtyard, on the central east side of the nine gates, is an independent and enclosed space specifically designated for stabling horses and parking vehicles. The entrance to this yard opens towards Yanjia Hutong, with a door measuring approximately 3 m in width. The stone threshold is level with the ground; however, due to years of horse-drawn carriages passing in and out, distinct rutted traces have been left on the surface before the entrance. All buildings within this courtyard have been demolished, leaving only the courtyard door as a remnant of its historical significance.

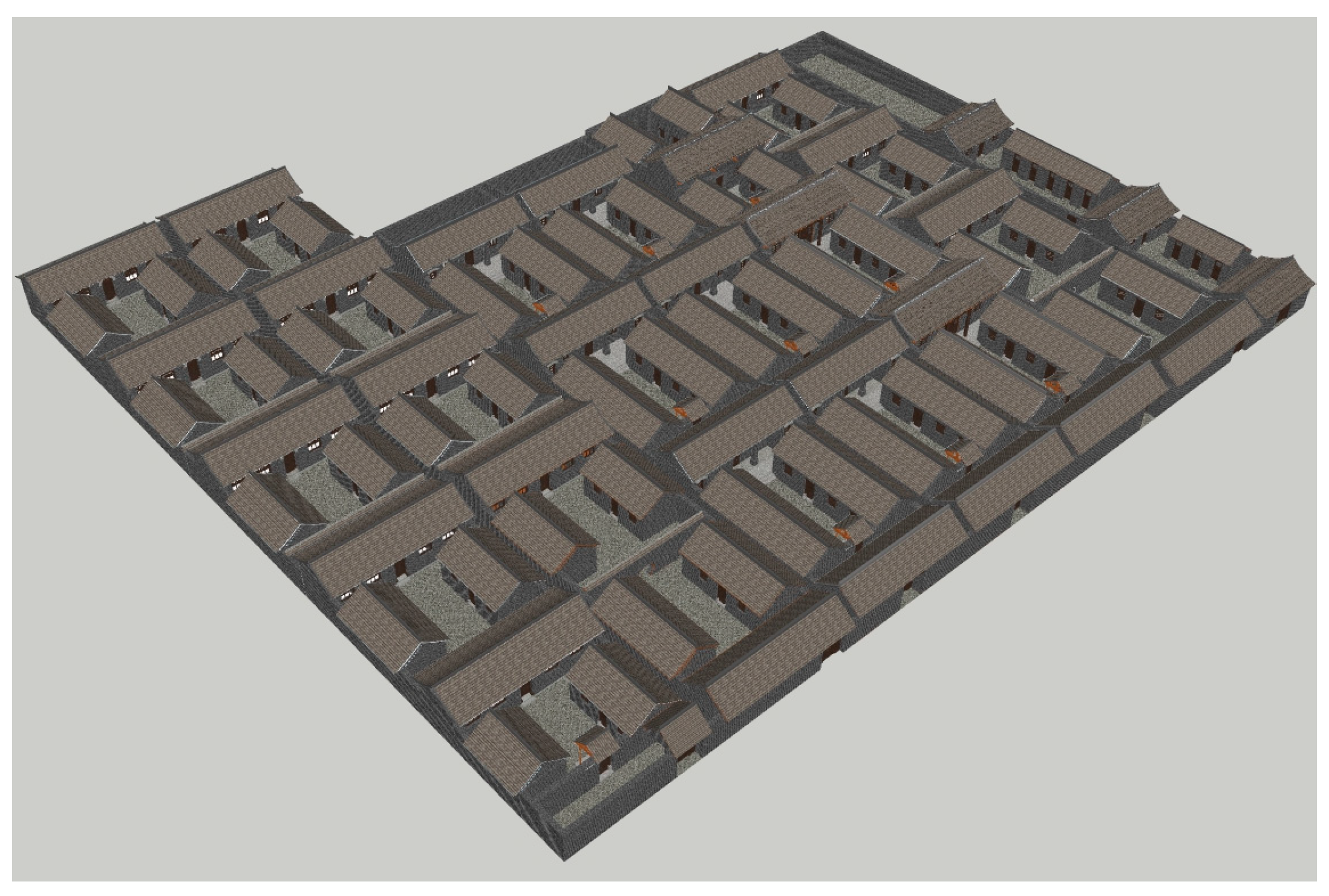

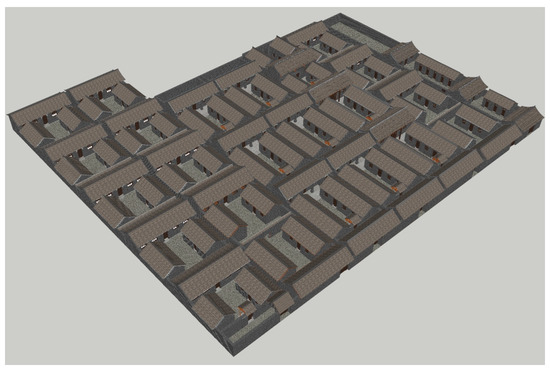

The restored overall plan and the restoration model of “Wang’s Old House” are presented, respectively, in Figure 11 and Figure 12.

Figure 11.

The restored original floor plan of “Wang’s Old House”.

Figure 12.

Restoration model of “Wang’s Old House”.

The overall layout of “Wang’s Old House” is characterized by rigor and order, with a clear demarcation of functional zones. This design not only fosters a pleasant living environment but also underscores the prominent status of the homeowner. These traditional houses, distinguished by their solemn and straightforward appearance, adhere to the principle of symmetrical layout along the central axis. They emphasize the aesthetic value of “moderation” and highlight the harmonious symbiosis among the buildings, natural surroundings, and occupants. Furthermore, these structures represent an ideal integration of “benevolence” and “etiquette” [31]. In every detail, they meticulously delineate differences in rank and status while conveying profound cultural connotations [32].

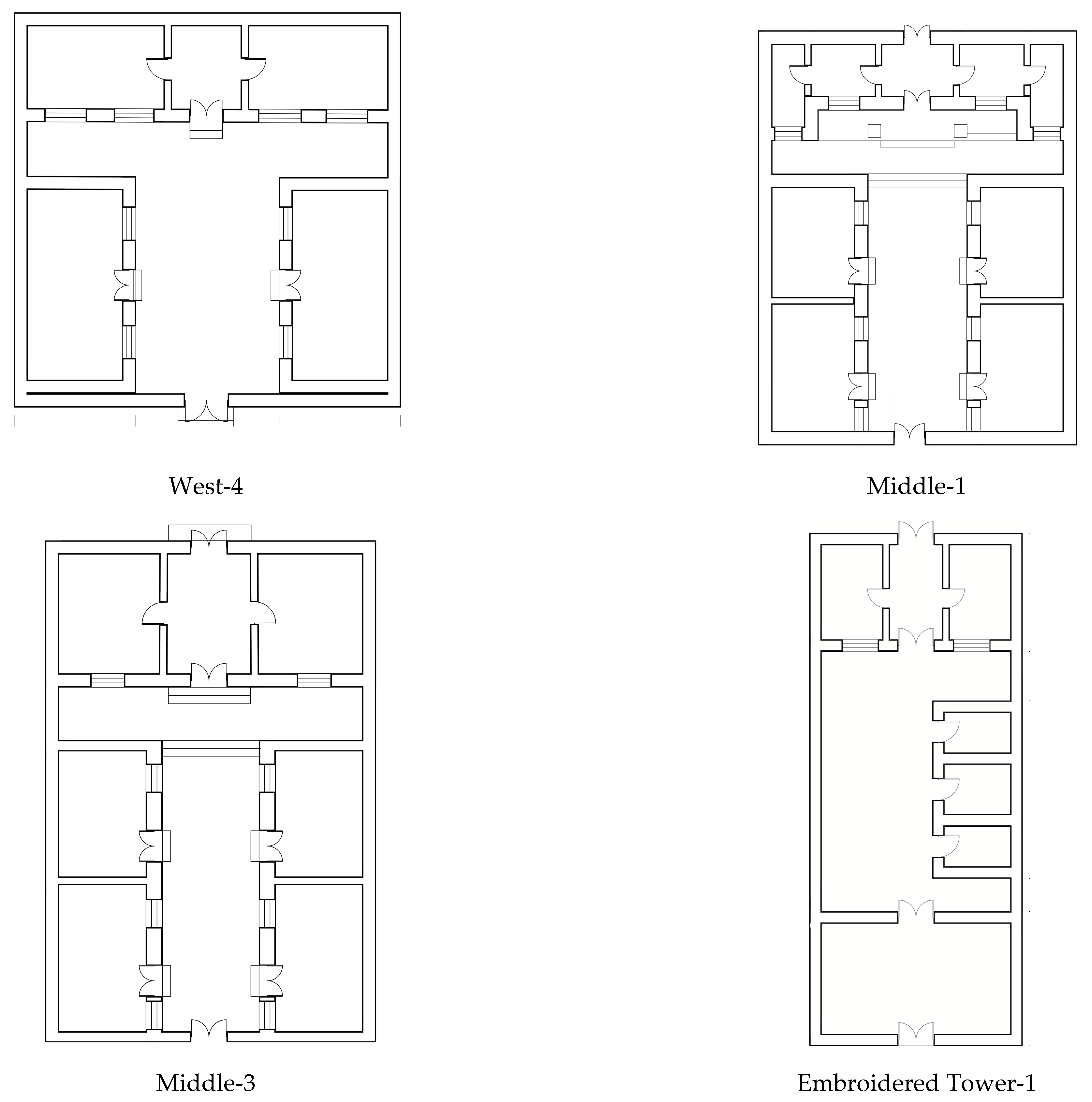

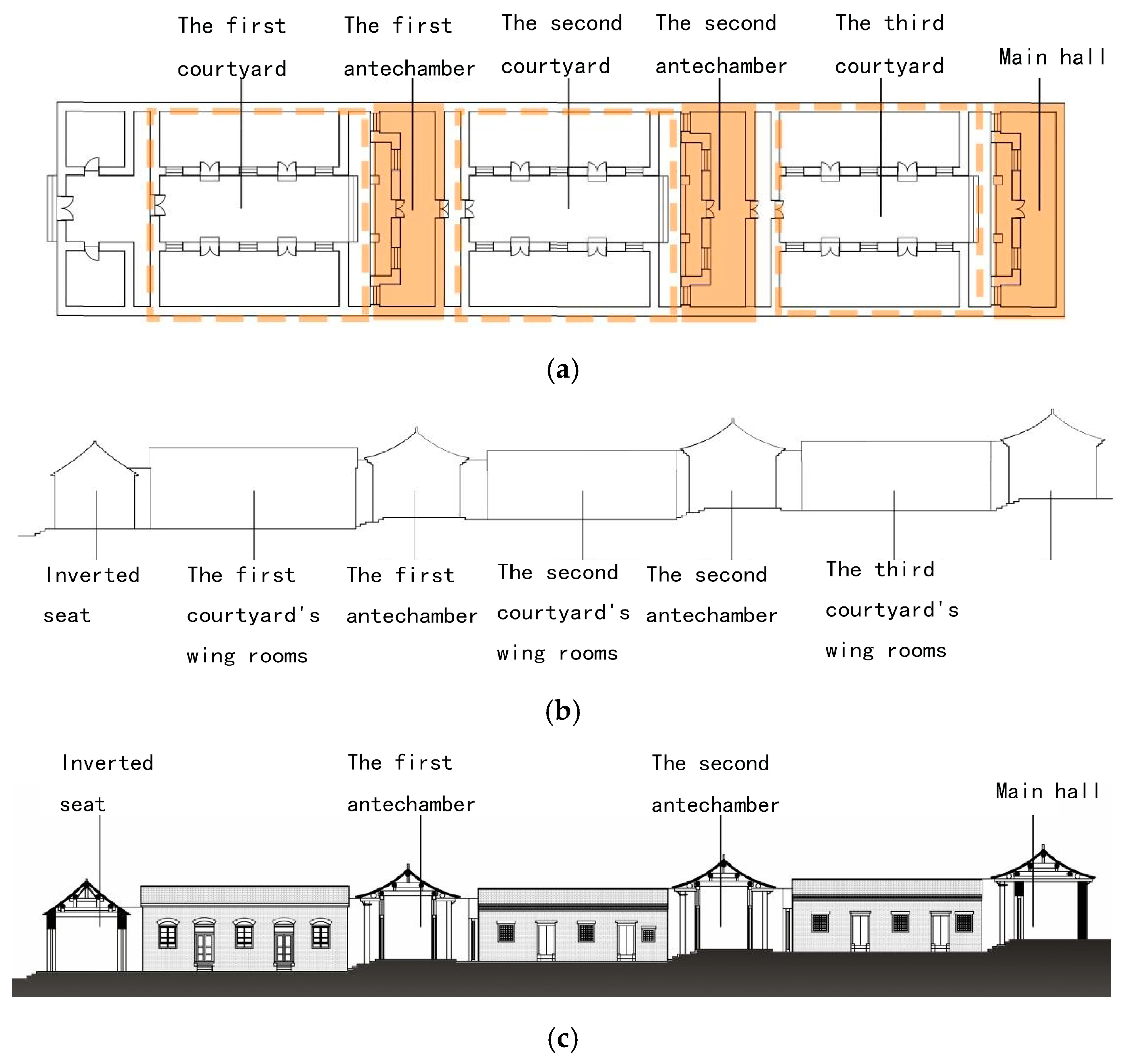

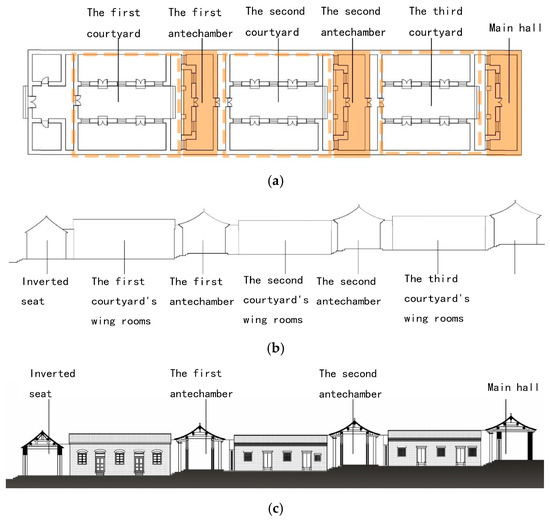

4.1.2. Typical Courtyard Layout Restoration

There was a ballad in Pengcheng during that time which stated: “The master of the Wang family kiln was so grand that nine doors were adjacent to each other in a rich and noble house”. In interviews with descendants of the Wang family, specifically Wang Jieying and Wang Zhiguo, it was mentioned that “in the middle courtyard of “Wang’s Old House”, there are nine doors leading into the courtyard; this is where the master of the Wang family resided”. Based on field research conducted by the author at existing buildings on the original site, some insights into the layout of “Wang’s Old House” have been gleaned.

According to the oral accounts of the descendants of the Wang family, “The middle group has an outer gate at the southern end adjacent to the street. Upon passing through this outer gate, one enters a foyer area. Within this foyer, an inner gate can be observed directly opposite the outer gate. After traversing this inner door, one gains access to the first inner courtyard”. Thus, on the southern side of the initial entry courtyard, two gates—the outer and inner gates—are arranged in alignment.

The inner courtyard is organized with a side house on the east and west sides, featuring three symmetrical rooms on the left and right sides. On the north side, there are three tiers of stone steps leading to a 3 m-wide platform, from which two stone steps descend into the first hall. The front porch of the main hall is supported by four pillars, with a wooden lattice wind door positioned centrally. Additionally, the fourth door is located on the north side of the first hall. Regarding the design of both the north and south doors of the hall, research confirms that its layout not only aligns with oral accounts provided by descendants of the Wang family but also reflects architectural characteristics typical of traditional dwellings in the Handan area.

The second inner courtyard is entered from the first hall through the gate of the second courtyard. The descendants of the Wang family mentioned that “The layout of the second inner courtyard mirrors that of the first courtyard; similarly, the second hall resembles the first hall. Exiting from the second hall leads to the third courtyard. The main house is on the northern side of this third inner courtyard, notably the tallest structure within the entire Jiumenxiangzhao Courtyard. At its center lies a space designated for family reunions and meetings, flanked on both sides by living areas: to the east reside the grandparents, while to the west reside the parents”. As a central residence within this familial setting, the main house symbolizes its role as head of the household. It reflects domestic life’s inherent separation of priorities and hierarchical order [33]. The door of the main house in the third inner courtyard is the ninth door. This architectural design effectively addresses family members’ practical living needs; however, it conveys profound social and cultural messages regarding clearly defined roles and status distinctions within familial structures. The prominence of this main house further underscores traditional ethical values emphasizing respect for hierarchy—particularly highlighting differences between elder and younger generations (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Typical courtyard layout restoration drawing. (a) Jiumenxiangzhao layout diagram. (b) Building outline. (c) Section drawing.

The three groups of nine-door phase control structures are fundamentally similar yet exhibit notable differences. An interview with the descendants of the Wang family revealed: “On the eastern side of the courtyard featuring the three groups of nine doors, there is a group of door halls located at the far eastern end known as “Xunmen”. This particular door stands tall and imposing; its frame measures one foot in width, while each of the two large sweeping doors is four inches thick and quite heavy. The door axle is directly inserted into a round mortar groove within the stone paving”.

The architectural layout of the courtyard house not only embodies the aesthetic principles of traditional Chinese architecture but is also, on a deeper level, significantly influenced by Confucianism. The emphasis on propriety and order inherent in Confucian thought is manifested in the design of the traditional courtyard house. The arrangement of rooms adheres to the Confucian ritual system. It exhibits a hierarchical structure that reflects family members’ identity and status while simultaneously shaping interpersonal relationships and daily lifestyles [27].

It is widely acknowledged that different cultures manifest themselves through distinct internal forms [34]. Each door and room in the Jiumenxiangzhao Courtyard carries profound cultural significance; collectively, they create a harmonious and orderly living environment rich with Confucian cultural heritage [35].

Most preserved buildings have undergone renovations, with many roof structures obscured by suspended ceilings; only a few retain their original appearance. These structures employ a raised beam system, wherein inverted seats and compartments depend on brick walls for load-bearing support. Wooden beams and purlins are positioned atop these walls, featuring forked handles at the ridge purlins to provide additional support, while rafters are covered with tiles. The hall section integrates a dual load-bearing system comprising brick and wood: beams are erected on columns, and arches rest upon these beams to sustain the rafters and roof. In the courtyard of the nine gates, steps ascend gradually from south to north—a design that symbolizes family prosperity while effectively facilitating rainwater drainage (Figure 13).

4.2. Rehabilitation of Building Facades

Based on the architectural typologies and characteristics of traditional houses in the south of Hebei Province, this study integrates oral history data with field research findings to provide a comprehensive speculation and reconstruction of the architectural façade of “Wang’s Old House”. This analysis encompasses the main house, side house, and reversely set house while considering roof structure, roof design, wall patterns, and details about doors and windows. Through an in-depth exploration and reproduction of these architectural components, this paper aims to restore the historical appearance and distinctive features of “Wang’s Old House”.

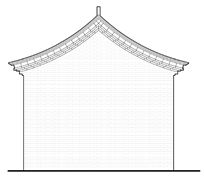

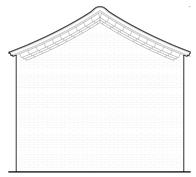

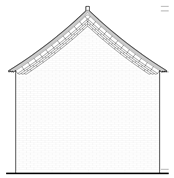

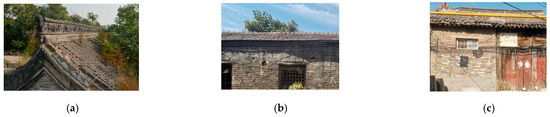

4.2.1. Roof

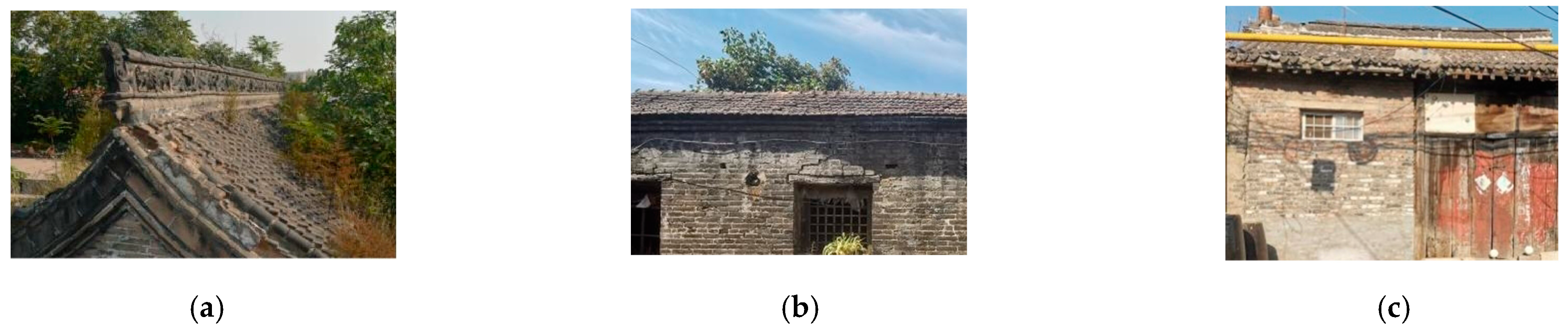

Described by the descendants of Wang’s family, “the roofs of the buildings in the mansion are double-slope roofs”. Based on this description and field research photographs (Figure 14), the original buildings are presumed to have had complex double-slope roofs. The main house and reversely set house are adorned with flower-ridged kissing beasts standing at a height of 2 m. In contrast, the roof of the compartment house also exhibits a complex double-slope design but reaches a height of only 1.5 m; its roof and ridge are covered with green tiles. The eaves incorporate tiles and water drops to protect against moisture-related damage to rafters and to serve an aesthetic purpose.

Figure 14.

Roof form: (a) the roof of main rooms; (b) the roof of side rooms; (c) the roof of reversely-set house.

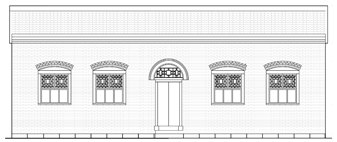

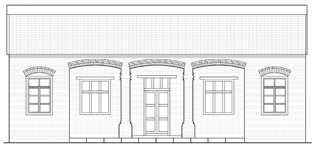

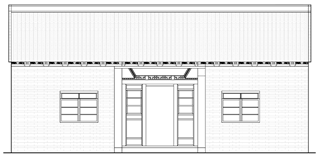

4.2.2. Front Elevation of Building

The exterior walls of the building are constructed from green bricks with a thickness of 600 mm, which not only endows the structure with significant load-bearing capacity but also enhances its fire resistance. The selection of green bricks enables “Wang’s Old House” to maintain a warm living environment during winter while remaining cool in summer. At the junction between the façade wall and the roof of “Wang’s Old House”, a distinctive variation in masonry technique is employed, creating an apparent boundary between these two elements. The main house at the center of “Wang’s Old House” is elevated on a significant bluestone step, whereas the western main house rests upon a substantial bluestone foundation. The façade features heavier materials arranged from top to bottom; this design adheres to architectural principles and fosters a visually reassuring sense of security (Table 1).

Table 1.

Elevation drawing of the building’s front façade.

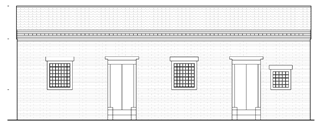

4.2.3. Gable Wall

The gable wall’s design is notably intricate, constructed from robust green bricks. Its summit is adorned with a zigzag pattern resembling mountain flowers, which adds a touch of exquisite detail [36]. Within this section of the gable wall, an ingenious brick sculpture is embedded on one side. This feature not only facilitates ventilation and air exchange but also enhances the overall aesthetic appeal of the design (Table 2).

Table 2.

Elevation of the gable wall.

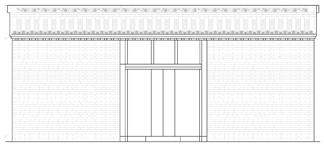

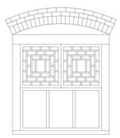

4.2.4. Doors and Windows

The design of the windows and doors adheres to aesthetic principles of balance and symmetry, employing a centered layout that harmoniously integrates with and enhances the overall aesthetics of the building (Table 3). The dimensions of the windows and doors are carefully calibrated to ensure optimal natural lighting and ventilation, thereby further elevating the structure’s aesthetic value. The role of the frame, as a significant component in partition construction, transcends traditional functionality. The partition is an inclusive element within the overall architectural framework, typically avoiding an emphasis on intricate carvings or decorations. Integral to this partition structure, window frames facilitate natural light entry, promote indoor air circulation, and showcase decorative carving artistry. The selection of materials for window and door frames—characterized by high strength and enduring durability—emerges as a superior choice for crafting aesthetically pleasing window and door structures. In an era in which glass materials were not widely utilized, these windows were innovatively constructed using small wooden partitions and rice paper treated with oil to enhance light transmission. This design was not only visually appealing but also embodied practical wisdom, primarily serving to shield against windy conditions while effectively minimizing wind impact; additionally, exterior mortar prevented snow accumulation on the window surfaces, thus safeguarding the structural integrity of the windows [37].

Table 3.

The windows and doors of “Wang’s Old House”.

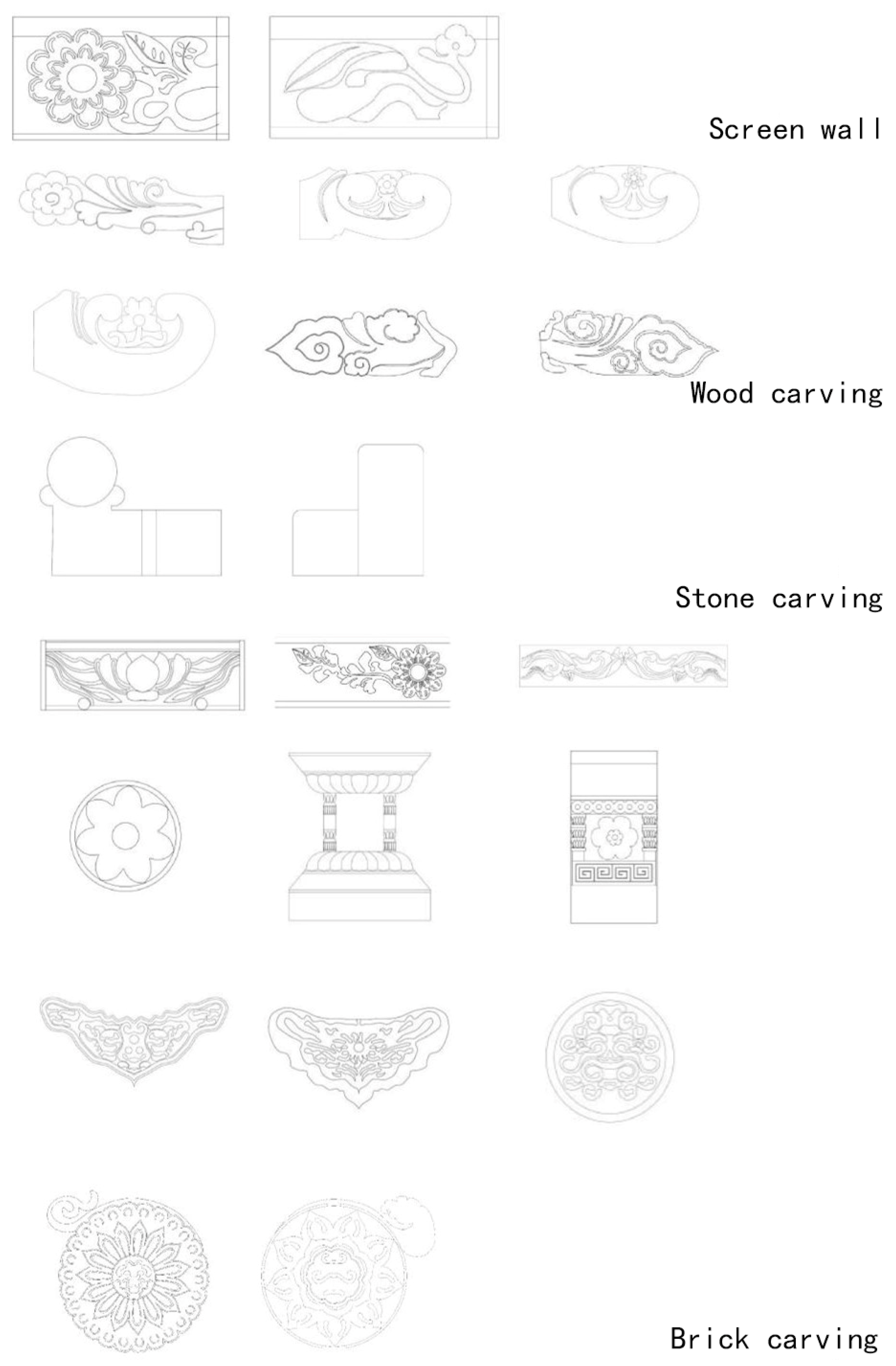

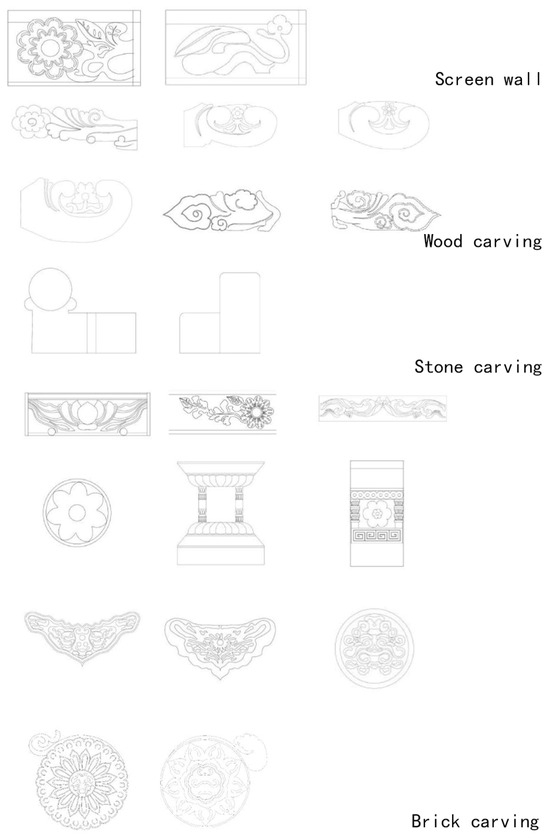

4.3. Architectural Decoration Detail Atlas Record

The themes of residential decorations profoundly reflect individuals’ daily lifestyles, production activities, customs, religious beliefs, and aesthetic orientations [38]. These elements serve not only as manifestations of personal or collective emotions and values but also as representations of the level of social productivity and cultural perspectives characteristic of specific historical periods. Essentially, they constitute a phenomenon imbued with rich cultural connotations. “Wang’s Old House”, a structure steeped in historical significance, is adorned with diverse decorative elements that not only emphasize the unique charm of traditional residential architectural art but also convey to the world the cultural essence and artisanal wisdom from bygone eras through meticulous attention to detail (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Decorative images.

The wall at the entrance of an ancient residential compound is referred to as the “hidden” (or “shadow”) wall on the inside, while the exterior portion is called the “wall”. Collectively, these elements are known as the shadow wall. Over a long history of transformation, the shadow wall has evolved into a platform for showcasing the culture and folklore of various ethnic groups and regions in North China. It illustrates the historical style and characteristics of individual households or families and reflects broader regional attributes in terms of economic, cultural, political, and architectural developments during specific periods. In traditional residential houses in the south Hebei area, shadow walls are predominantly found in courtyards. Through intricate decoration and diverse carving techniques, these walls soften the entrance area and serve as an internal barrier that delineates the physical space of entry. Additionally, their external avoidance function creates a semi-open virtual space. This harmonious interplay between real and virtual spaces seamlessly integrates the interior and exterior elements of the residences, facilitating a smooth transition within spatial dimensions [39]. When constructing shadow walls, individuals often emphasize the spiritual pursuits and cultural connotations associated with them. The most prominent manifestation of this is the reflection of social status. In a strictly hierarchical feudal society, the construction of a shadow wall necessitates substantial human and material resources. When situated within a compound, the specifications for building such walls can serve as an immediate indicator of the owner’s social standing, as well as their beliefs and aspirations. For instance, the Wang family was recognized as the wealthiest in Pengcheng during the period in question, and their establishment of “Wang’s Old House” functioned not only as a residence but also as a symbol of status. Furthermore, shadow walls fulfill various psychological needs for the owners of compounds at multiple levels. Beyond providing security and privacy to courtyard spaces, these walls act as visual barriers that align with geomantic principles aimed at concealing wind while gathering qi (vital energy). This design ensures that outsiders cannot easily penetrate or overlook the spatial structure of the courtyard at first glance [40]. The shadow wall employs metaphorical representations of objects through techniques such as brick carving and other decorative methods. Incorporating symbolic elements gives the mansion’s owner a sense of spiritual support and belonging on a deeper level and underscores the significance of their position within the estate [41].

The wood-carving art style of the late Qing Dynasty exhibits significant changes when compared to that of the Ming Dynasty and early Qing Dynasty. It departs from the simplicity of the Ming era and does not adhere to the intricate finesse seen in early Qing craftsmanship; instead, it presents a more patterned and decorative unique style [42]. In “Wang’s Old House”, wood carving is extensively utilized, as is evident in various elements ranging from the façade decoration of the main entrance to the façade above the hall, as well as in the delicate frames surrounding doors and windows. These features incorporate diverse patterned elements such as cloud motifs, geometric shapes, nets, and floral designs. The artisans skillfully create an assortment of decorative motifs by expertly carving indentations into wooden panels. As one of China’s earliest developed traditional wood-carving techniques, line carving is particularly prevalent in ornamental details and small residential structures [43]. This technique showcases a high level of craftsmanship and imparts an air of ancient elegance to these buildings [44].

Stone carvings are often regarded as a symbolic representation of wealth and capital accumulation, owing to the rarity of the material and the intricate, costly processes involved in their creation. Additionally, stone carving serves as a significant decorative element within the Wang family’s ancestral home. Components such as the upper horse and hugging drum stone exhibit technical excellence with their smooth carving lines. These elements fulfill practical functions and embody a humanized design concept through their soft and delicate contours. As one of the primary carving techniques found within the manor, the art of stone carving naturally reflects the artistic characteristics inherent in local traditional craftsmanship against the rich cultural backdrop of stone-carving artistry [45].

Brick-carving art, a prevalent technique in the decoration of residential buildings, is comprehensively and brilliantly showcased in the Wang family residence. The brick-carving patterns embody rich auspicious symbolism and imbue the building with profound cultural connotations and deep historical heritage [46]. In “Wang’s Old House”, the use of brick-carving decoration is particularly prominent, adorning various details of the roof, including elements such as ridges, drips, and tiles. The drip is a ubiquitous architectural component skillfully integrated into the eaves and tiles at the front. This feature not only effectively facilitates water drainage and protects the structural integrity of the building from rainwater erosion, but also enhances its elegance through unique decorative characteristics [47]. Since the Tang and Song dynasties, drips have frequently been employed alongside tiles to embellish roofs of high-grade buildings, thereby becoming a striking visual element [48]. In “Wang’s Old House”, the drip features a triangular curved-edge pointed design, upon which an exquisite lotus pattern is intricately carved. This showcases the craftsman’s skill and symbolizes purity and elegance. The architectural elements known as eave tiles consist of front and back components; the rear section comprises tube tiles closely aligned with the eaves, referred to as “danghou”. In contrast, the front is exposed and serves as a focal point for decoration, often adorned with complex patterns or meaningful inscriptions, termed “danglian”. On the roof of “Wang’s Old House”, the design of round tiles is particularly refined. These tiles exhibit a symmetrical distribution of lotus patterns alongside floral and foliar motifs, featuring realistic depictions such as lion head designs [49]. Although it may be challenging to discern specific details within the lotus pattern, its symmetrical beauty remains striking. The lion head tile displays a lifelike style: its eyes appear fierce and wide open, complemented by a pronounced nose and an agape mouth framed by thick gnarled whiskers. The roofing structure of “Wang’s Old House” exhibits remarkable neatness; gray tiles create an aesthetically pleasing sloped roof reminiscent of human form. Notably, the lotus flower patterns on the ridge bricks are exceptionally detailed and vivid, while animated kissing animals at both ends enhance this visual appeal.

It is noteworthy that “Wang’s Old House” stands out due to its distinctive decorative design, which skillfully integrates traditional craft elements—specifically “longkui”. The “longkui” is a specialized container used during ceramic firing. Its primary function is to prevent kiln slag and ash from compromising the quality of ceramics, thereby enhancing the success rate of firing and ensuring that the appearance of the ceramics remains flawless. The design of a “longkui” is contingent upon the dimensions of the ceramic ware; typically, in Cizhou ware, it takes on a cylindrical shape with one side open and the other featuring an “eye” [50]. Although “longkui” are not used for wall construction, they serve as significant decorative elements and symbols of psychological support. They profoundly reflect residents’ respect for and inheritance of traditional culture [51,52]. As an integrated entity encompassing architectural functionality, architectural decoration represents a harmonious blend of structure and art and a comprehensive exhibition of technology intertwined with artistic expression.

5. Discussion

The old residence of the Wang family holds certain historical, artistic, and scientific values. It profoundly reflects the common living customs, beliefs, and aesthetics of the potters in Pengcheng and showcases the application of natural resources and construction materials. The two-sleeve floor plan optimizes the use of space; the axial and longitudinal layout with nine doors facing each other demonstrates the wealth and status of the potters during that period [53]. The carved patterns on the doors, windows, and wall decorations are symbols of good luck and wealth, representing people’s yearning for a better life. The decoration is firmly rooted in the local cultural background, conveys the inherent rich emotional depth of this culture, and simultaneously reveals a profound concern and respect for the natural environment. The reasonable site selection and layout of the building, along with the use of local stone and wood, reduce costs and promote harmonious coexistence with nature. The entire residence retains rich historical memories and is also a witness to the continuation and evolution of Cizhou kiln culture since the late Qing Dynasty.

During the field research, the remaining courtyard ruins were surveyed and mapped, and the unpreserved parts were speculated. There is a gap between the overall plan and the original layout. In the methodology of oral history, the subjectivity of the interviewer and the dialects of the interviewees may introduce errors in the restoration process, exerting an influence on the restoration of buildings.

During the process of architectural restoration, local folk customs and traditions ought to be respected, and sufficient research and preparation should be conducted for existing buildings. Oral history is not genuine history. We should recognize the new orientations that oral history brings to us, but also identify the shortcomings of the methods. In this article, oral historical materials and mapping outcomes are integrated, and the inference results are presented with an objective and meticulous attitude. In the future architectural restoration, it is of significant importance to employ digital approaches and utilize digital technologies for information preservation and cultural dissemination.

6. Conclusions

This paper takes “Wang’s Old House” as a case study and employs a research approach based on oral history. Through the collection, organization, and in-depth analysis of the obtained oral materials, in conjunction with the field survey data of “Wang’s Old House” old residence and the studies on the dwellings in Handan, this paper infers the unique layout structure of “Wang’s Old House” characterized by “nine gates facing each other” and the original floor plan of the courtyard.

In the original handicraft settlement, the author conducts the excavation of the typical spatial settlement of the original Cizhou Kiln kiln-owner villages. “Wang’s Old House”, as a typical representative of the kiln-owner dwellings in the Cizhou Kiln, is a historical reflection of the material heritage in the same time and space. As a kiln-owner residence, “Wang’s Old House” not only encompasses the courtyard where the owner resided in the middle but also includes the courtyard where the steward and the shopkeeper lived in the west and the carriage and horse courtyard in the north, fully manifesting the owner’s commercial background. In the construction of individual buildings, low-tech construction methods are utilized, local large bluestones and blue bricks are adopted, and “longkui” are employed for roof drainage and underground drainage. “Longkui” not only represent the rational utilization of local materials but also demonstrate the unique architectural style of the characteristic cultural elements in the Cizhou Kiln area and even reflect the kiln-owners’ faith and worship of the kiln god. The oral materials of the descendants of the Wang Family and the layout plan of the residence provided by them are mutually verified with the on-site investigation of the residence ruins, restoring the original layout of the residence and enriching the related research on Cizhou Kiln studies.

This research holds considerable significance. Throughout the restoration process, we are committed to respecting historical facts while preserving its original appearance and distinctive features. Additionally, this study also offers new methods for the protection and continuation of traditional dwellings in the Cizhou Kiln area, thereby promoting the heritage protection and cultural development related to the traditions of the Cizhou Kiln.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.W. and Y.M.; methodology, Y.M. and R.W; software, R.W.; validation, R.W. and Y.M.; investigation, R.W.; resources, Y.M.; data curation, R.W.; writing—original draft preparation, R.W.; writing—review and editing, R.W.; visualization, R.W.; supervision, Y.M.; project administration, Y.M.; funding acquisition, R.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- İpekoğlu, B. An architectural evaluation method for conservation of traditional dwellings. Build. Environ. 2006, 41, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henna, K.; Mani, M.J. Transitions in traditional dwellings. Curr. Sci. 2022, 122, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, S.L.; Nasar, Z.A.J. Urban identity in the holy cities of Iraq: Analysis of architectural design trends in the city of Karbala. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2020, 14, 210–222. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Chen, W.; Yang, M. Study on the protection of settlements and tangible cultural heritage along the Fukouxing from the perspective of cultural route. J. Landsc. Res. 2021, 13, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonara, G.J. An Italian contribution to architectural restoration. Front. Archit. Res. 2012, 1, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons-Valladares, O.; Nikolic, J.J. Sustainable design, construction, refurbishment and restoration of architecture: A review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olga, P.; Timothy, G.; Svetlana, G.J.A. Restored layers: Reconstruction of historical sites and restoration of architectural heritage: The experience of the United States and Russia (case study of St. Petersburg). Archit. Eng. 2020, 5, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kasapoğlu, M.; Çakıcı, F.Z. Restoration in the discipline of architecture: A bibliometric analysis of research trends since 2000. Gazi Univ. J. Sci. Part B Art Humanit. Des. Plan. 2023, 11, 751–770. [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua, M.G.; Caroti, G.; Piemonte, A.; Ruschi, P.; Tenchini, L. 3D survey techniques for the architectutal restoration: The case of St. Agata in Pisa. ISPRS—Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, 42, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacci, G.; Bertolini, F.; Bevilacqua, M.; Caroti, G.; Martínez-Espejo Zaragoza, I.; Martino, M.; Piemonte, A.J. HBIM methodologies for the architectural restoration. The case of the ex-church of San Quirico all’Olivo in Lucca, Tuscany. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, 42, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Sun, X.; Ali, N.; Zhou, Q.J. Digital documentation and conservation of architectural heritage information: An application in modern Chinese architecture. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusaporci, S. The representation of architectural heritage in the digital age. In Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology, 3rd ed.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2015; pp. 4195–4205. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpless, R. The history of oral history. In Theories and Applications, Red; Charlton, T.L., Myers, L.E., Sharpless, R., Eds.; AltaMira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2008; pp. 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hoopes, J. Oral History: An Introduction for Students; UNC Press Books: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Block, K.P. The New Oral History of Architecture: Review Essay. Oral Hist. Rev. 2020, 47, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, D.A. Doing Oral History; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ernstson, H.; Nilsson, D. Towards situated histories of heterogenous infrastructures: Oral history as method and meaning. Geoforum 2022, 134, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shopes, L. Oral history. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 451–465. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, P. The Role of “Oral History” Method in the Study of Vernacular Architecture: The Interview with Chen Hongyou. New Archit. 2022, 201, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ardhyanto, A.; Dewancker, B.; Tsai, Y.L.; Heryana, R.E. Memory recollection and oral history: A study of vernacular architecture transformation of the past. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 3435–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, A. The City of Blue and White: Chinese Porcelain and the Early Modern World; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, L.S. Beyond the Western Pass: Emotions and Songs of Separation in Northern China; The Ohio State University: Columbus, OH, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, C.C.; Lee, R.D. Famine, revolt, and the dynastic cycle: Population dynamics in historic China. J. Popul. Econ. 1994, 7, 351–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, C.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.J. Investigation Analysis and Protection Strategy of Wenchang Pavilion in Pengcheng. J. Landsc. Res. 2020, 12, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Studies on Ancient Chinese Ceramics; Forbidden City Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2010; Volume 16, pp. 273–280. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Fang, K.; Chen, L.; Furuya, N. The influence of atrium types on the consciousness of shared space in amalgamated traditional dwellings—A case study on traditional dwellings in Quanzhou City, Fujian Province, China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2019, 18, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wang, X.; Fang, K.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Furuya, N. The transformation of the bright-dark space in Chinese traditional dwellings. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 2768–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-F.; Chiou, S.-C. Research on the Sustainable Development of Traditional Dwellings. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Shang, B.J. The Impact of Geomorphological Factors on The Distribution of Typical Dwellings in Northern China. Rev. Int. De Contam. Ambient. 2019, 35, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, B.; Yang, Q.; Peng, F.; Liang, L.; Wu, S.; Xu, F.J. Evolutionary mechanism of vernacular architecture in the context of urbanization: Evidence from southern Hebei, China. Habitat Int. 2023, 137, 102814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N. The Interitance and Transformation of Traditional Huizhou Elements into New Forms: Redesigning Lu Village. 2014. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/45634 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Wu, X.; Zhao, Y.J. The concept of ritual in Confucian thought and its implications for social order. Trans-Form-Acao 2024, 47, e02400331. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, F.; Wang, J.P. Analysis of Shanxi Traditional Local-Style Dwellings. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 477–478, 1148–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapaport, A.J. House Form and Culture; Premtice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Yang, T. Landed and Rooted: A Comparative Study of Traditional Hakka Dwellings (Tulous and Weilong Houses) Based on the Methodology of Space Syntax. Buildings 2023, 13, 2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Hu, H.; Miao, L.; Zhou, B. Analysis on the forms and regional characteristics of the traditional dwellings in mountainous central Shandong Province. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 81, 012129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F. Chinese Climate and Vernacular Dwellings. Buildings 2013, 3, 143–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, F.J. Research on the architectural decoration of traditional Chinese vernacular dwellings. J. Archit. Conserv. 2019, 25, 136–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, R.G. China’s Living Houses: Folk Beliefs, Symbols, and Household Ornamentation; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.W. The Design and Research of the Display Space Wall Based on The Screen Wall. Master’s Thesis, North China University of Technology, Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.Y.; Dong, W.; Zhou, B.; Li, S. Analysis of Regional Characteristics for Chinese Traditional Dwelling. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 357–360, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Wang, J.P.J.A.M.R. Analysis on the Decoration of Traditional Dwellings in Shanxi Province-Taking Dwellings in Ding Village of Xiangfen County as an Example. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 634, 2761–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiderman, C.; Johnston, W. The Beginner’s Handbook of Woodcarving: With Project Patterns for Line Carving, Relief Carving, Carving in the Round, and Bird Carving; Courier Corporation: North Chelmsford, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.; Li, L.; Gao, Y.; Liu, N.; Cheng, L. Expressing the Spatial Concepts of Interior Spaces in Residential Buildings of Huizhou, China: Narrative Methods of Wood-Carving Imagery. Buildings 2024, 14, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, X.J. Study on Carving Art of DangShi Manor in Suide County, Shaanxi, China. Asian Cult. Hist. 2012, 4, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cao, Z.; Mustafa, M.B. A Study of Ornamental Craftsmanship in Doors and Windows of Hui-Style Architecture: The Huizhou Three Carvings (Brick, Stone, and Wood Carvings). Buildings 2023, 13, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, R.G. Chinese Houses: The Architectural Heritage of a Nation; Tuttle Publishing: Rutland, VT, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, E.; Rand, P. Architectural Detailing: Function, Constructibility, Aesthetics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, X.; Huang, Y.J. Study on Traditional Chinese Architecture. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 575, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.M.; Guan, J. Research on the Cage Helmet Culture of Cizhou Kiln. Ceram. Stud. 2020, 35, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.H.; Yan, H.; Yang, C.H.; Ma, Y.J. Investigation and Analysis of the Kiln Structures (Lungui) in the Cizhou Kiln Site (Pengcheng Town). Anhui Archit. 2018, 24, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.L. The Lóng Kuī Wall on Péngchéng Street—A Witness to Ancient Cizhou Kilns. Arch. World 2006, 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.H.; Jiang, L.C. Analysis on the Plane Space Structure of Handan Traditional Houses: Taking Xujia Manor in Boyan Village as an Example. Archit. Cult. 2021, 248–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).