Research on the Multi-Sensory Experience Design of Interior Spaces from the Perspective of Spatial Perception: A Case Study of Suzhou Coffee Roasting Factory

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To explore the relevant concepts, characteristics, and the subject–object relationships of spatial perception through case study analysis;

- To analyze how different sensory design elements (such as vision, hearing, touch, smell, and taste) collaborate within a spatial design to enhance the sensory experience;

- To propose a set of practical design methods and strategies for interior spatial perception, offering both theoretical support and methodological guidance for future design practices.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Concepts Related to Spatial Perception

2.2. Perceptual Phenomenology and Spatial Perception

2.3. Fundamental Characteristics of Spatial Perception

2.4. Factors of Spatial Perception

2.4.1. The Subject of Spatial Perception: Senses

2.4.2. The Object of Spatial Perception: Spatial Elements

2.5. Construction of Theoretical and Design Strategy

3. Methodology and Integrated Multi-Sensory Design Strategies

3.1. Methodology

3.1.1. Research Type and Theoretical Orientation

3.1.2. Case Selection and Rationale

- The cases are completed architectural or interior spaces of notable influence;

- The design features consciously integrate two or more sensory dimensions;

- The cases are closely related to interior spatial experience, encompassing cultural, commercial, or public spaces;

- They provide comparative value in terms of spatial strategies and perceptual design.

3.1.3. Research Framework

3.2. The Construction of Visual Perception

- Color as a means of conveying spatial emotion and scale differentiation;

- Light and shadow as fundamental elements in creating spatial depth and a sense of mystery;

- Enriching the spatial formal language to enhance the depth of visual perception.

3.2.1. Color as a Means of Conveying Spatial Emotion and Scale Differentiation

3.2.2. Light and Shadow as Fundamental Elements in Creating Spatial Depth and a Sense of Mystery

- Natural light as a key element in enhancing visual focal points within a space;

- Natural light as an element that enriches spatial depth and visual experience;

- Natural light as a means of creating spatial ambiance.

3.2.3. Enriching the Spatial Formal Language to Enhance the Depth of Visual Perception

3.3. Designing Auditory Perception (Carefully Crafted Soundscapes to Enhance Immersion)

- Soundscape design;

- Temporal control of sound;

- Contextual guidance through sound;

- Immersive sound interaction experience.

3.3.1. Soundscape Design

3.3.2. Temporal Control of Sound

3.3.3. Contextual Guidance Through Sound

3.3.4. Immersive Sound Interaction Experience

3.4. The Application of Tactile Perception

- Creation of direct tactile perception;

- Creation of indirect tactile perception.

3.4.1. Creation of Direct Tactile Perception

3.4.2. Creation of Indirect Tactile Perception

3.5. Integration of Olfactory and Gustatory Perception (Experiencing Space Through Scent)

- The selection of scent and the creation of emotions;

- The creation of memorable scent spaces.

3.5.1. The Selection of Scent and the Creation of Emotions

3.5.2. The Creation of Memorable Scent Spaces

4. Results: Conceptual Design Scheme

4.1. Project Background

4.2. Analysis of the Existing Factory Space

- Low spatial utilization: Large areas of the first floor remain vacant, reflecting a disconnect between land resource value and actual functional activation;

- Monotonous circulation: Vertical circulation is concentrated in two staircases located at either end of the building. The considerable floor height and limited lateral connectivity result in constrained movement and a lack of fluid spatial experience;

- Structural constraints on functional expansion: Production activities are fully concentrated on the second floor, where the use of heavy machinery imposes excessive loads on the floor slab, posing potential safety concerns;

- Absence of sensory spatial quality: The original design adopts a purely utilitarian logic, lacking the integration of key sensory dimensions such as lighting dynamics, acoustic quality, olfactory atmosphere, and tactile materials. The resulting spatial ambiance is emotionally disengaging and fails to provide an immersive experience.

4.3. Theme and Design Strategy

4.4. Spatial Structure and Circulation Organization

4.5. Application of Spatial Perception Design Strategies

4.5.1. Factory Entrance Area

4.5.2. Mezzanine Coffee-Making Experience Zone

4.5.3. Second-Floor Interactive Installation Experience Zone

4.5.4. Second-Floor Coffee Culture Exhibition Area

4.6. Virtual Reality Technology and 3D Modeling in Spatial Design

4.7. Comparative Analysis of Pre- and Post-Renovation Design

- Before renovation: The original site was a prototypical industrial facility with a spatial layout primarily driven by production efficiency. Circulation followed a rigid, linear, and enclosed pattern, with minimal access to natural light and no deliberate use of color or sensory-oriented design elements. The overall spatial atmosphere was utilitarian in nature, lacking emotional expression and offering limited opportunities for user engagement or affective resonance;

- After renovation: The redesigned space integrates multi-sensory strategies grounded in the spatial perception theory and phenomenology, creating a dynamic and immersive environment. These strategies include multi-layered spatial relationships that encourage exploration, a carefully curated lighting design that modulates the spatial atmosphere, and the creation of a soundscape that enhances emotional resonance. The use of tactile materials and textures, alongside scent-driven ambiance, further enriches the sensory experience. Overall, these interventions not only improved the functional flow of the space but also fostered deeper emotional engagement, offering users a more holistic, immersive, and emotionally resonant spatial experience.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

- This study, grounded in the phenomenological theory of perception, proposes a spatial perception design strategy centered around multi-sensory design. The theory of phenomenology of perception emphasizes the role of human sensory experiences in shaping an individual’s perception of the world [8]. In the context of architecture and interior design, while the existing research has explored the sensory dimensions of spatial perception [120], these studies often focus on the impact of a single sense. In contrast, this study proposes several key design strategies by considering multiple sensory elements, including light, color, form, sound, touch, and scent, to regulate the emotional ambiance of the space and enhance the customers’ sensory experience. These strategies include the following: (1) the construction of visual perception: regulating the emotional ambiance of space through color and light, enriching the spatial form language, and enhancing the depth of visual perception; (2) auditory perception design: soundscape design, the temporal control of sound, the contextual guidance of sound, and immersive sound interaction experience; (3) the application of tactile perception: the creation of direct and indirect tactile perception; and (4) the integration of olfactory and gustatory perception: the selection of scent and the creation of emotions, the creation of memorable scent spaces, etc. The existing research, such as Lee Keunhye’s study, has pointed out that the synergistic interaction of sensory elements significantly impacts emotional experience [1]. Building on this fact, this study further validates this idea, demonstrating how these sensory elements work together to create a spatial ambiance with emotional regulation capabilities. The combination of light, color, and form can regulate the visual effects of a space, while sound and scent enhance immersion and emotional connection, complementing the dimensions that visual perception alone cannot provide;

- According to the existing literature, spatial perception is not solely an experience of a single sense but is achieved through the interaction of multiple senses [121]. For example, Spence C. suggested that multi-sensory elements such as vision, hearing, and touch in interior design can significantly enhance the user’s spatial experience [16]. In this study, we illustrate the above-mentioned perspectives through a conceptual design case. In the spatial proposal for the Suzhou Coffee Roasting Factory, visual elements—such as dynamic lighting, material textures, color schemes, and the curved form of the coffee bean installations—are combined with auditory experiences (e.g., ambient music and the rhythmic sound of falling coffee beans) and tactile interactions (including material contrasts and immersive touch-based installations). Together, these elements create a rhythmic and dynamic spatial atmosphere. This practice validates the influence of strategies of visual, auditory, and tactile perceptions on customers in commercial spaces, as proposed by Spence C. (2014) [122]. It demonstrates that the design of spatial ambiance can effectively enhance customer experience and shopping behavior, guide emotional responses, and increase the sense of immersion in the space, thereby boosting purchasing intent. It should be noted that this project is a conceptual design, and the analysis is grounded in the theoretical integration of sensory strategies with spatial design principles rather than empirical user testing. Future studies could extend this work by incorporating user feedback and behavioral analytics to further assess the practical implications of multi-sensory strategies in built environments;

- In addition, this study also analyzes the importance of olfaction and gustation in interior spaces and proposes relevant design strategies, aligning with the findings of Madzharov, Block, and Morrin (2015), who noted that scent and taste can effectively enhance the sensory appeal of a space, thereby influencing customer preferences and purchasing power [123]. In this study, the use of coffee aromas and interactive coffee bean selection not only enhanced the olfactory experience of the space but also stimulated customers’ gustatory needs, thereby increasing their brand loyalty and the memorability of the space. In addition, this study analyzes how the selection of scent directly affects people’s emotions and memory. This is similar to the conclusion drawn by Ehrlichman et al. through their experiments, which suggests that when the emotions triggered by a scent align with the emotional content of a memory, the emotion can influence the content of the recalled memory [124].

5.2. Practical Implications

- This study emphasizes the role of color and lighting modulation in visual design in shaping the spatial ambiance. Designers should flexibly use color and lighting to adjust the emotional tone of a space based on the functional requirements of the space and the emotional needs of the target customers. For example, in leisure and cultural spaces, warm tones and soft lighting create a relaxed atmosphere, helping to regulate customers’ emotions. In contrast, in commercial retail spaces, cool tones and ample lighting contribute to a sense of energy and engagement, encouraging customer interaction and purchasing behavior. Therefore, designers should consider the functional needs of a space and the emotional needs of the customers, using flexible combinations of color and lighting to meet diverse emotional experiences;

- Sound design and soundscape management are crucial for enhancing the sense of immersion in a space. Through precise soundscape design, designers can significantly enhance the customer experience, particularly in public spaces, commercial environments, and cultural venues. Soundscape design should not merely involve the selection of background music but also consider the rhythm, volume, and contextual integration of sound. For example, in dining spaces, soft background music and natural sound effects can create a relaxed and comfortable dining atmosphere for customers. In retail spaces, the alignment of music with the brand image can evoke emotional resonance in customers, enhancing their sense of engagement and desire to purchase;

- The design of touch and scent has a significant impact on the emotional ambiance of a space. Although touch and scent are often regarded as secondary design elements, their role in enhancing spatial appeal and improving customer memory is becoming increasingly important. Designers should consider using different tactile experiences through material selection and spatial layout details to enhance the depth and affinity of a space. Meanwhile, scent design, especially fragrances that evoke emotional connections with customers, can significantly increase brand loyalty and the memorability of a space. In commercial spaces, scent design should be closely aligned with the brand image by selecting appropriate fragrances to enhance customers’ emotional experience and strengthen their emotional connection with the brand, thereby boosting their purchasing intent.

5.3. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions and Future Research

6.1. Conclusions

- Visual design (such as color, light and shadow, and spatial form language) effectively shapes the emotional ambiance of a space by regulating emotions and psychological expectations. We explore three key aspects: first, the perception of temperature, scale, and depth in color, where the combination of warm and cool tones and contrasts influences the emotional expression of the space; second, the intensity and direction of and color temperature variations in natural and artificial lighting, which significantly adjust the atmosphere of the space, enhancing its liveliness or tranquility; and finally, the spatial form language, contrast, variation, permeability, layering, sequence, and rhythm guide visual flow and enhance the spatial depth and dynamism through the layout and size differences in spatial elements, thereby deepening the emotional and psychological impact of the space;

- Auditory design (such as soundscapes, temporal control of sound, etc.) is crucial for the comfort and sense of immersion in a space. We explore four aspects: soundscape design, which creates an auditory environment that aligns with the spatial ambiance; the temporal control of sound, adjusting the duration of and variation in sound to optimize emotional rhythms; sound contextual guidance, using specific sound effects to elicit emotional responses; and immersive sound interaction, which enhances sensory experiences through interactions with the space via digital media technology;

- Tactile design (including direct and indirect touch) enriches the sensory experience of the space through variations in materials, temperatures, and textures. Direct touch stimulates sensory responses through contact with surface materials, while indirect touch influences users’ psychological perceptions through the overall layout of the spatial environment and material properties (such as temperature and humidity), enhancing their overall cognition and emotional connection to the space;

- Olfactory and gustatory design stimulates memory and emotional connections through scent, adding a deep emotional dimension to the space and enhancing users’ immersive experience and brand identity. Specific scents can evoke emotional responses tied to individuals or cultures, enhancing the uniqueness of the space. Gustatory design, in turn, strengthens the emotional connection between users and the space, particularly in dining and commercial environments.

6.2. Future Research

- Quantitative evaluation methods for multi-sensory design: Future research will aim to establish a more scientific framework for the quantitative evaluation of multi-sensory design. This may involve the use of biometric feedback, data analytics, and psychological experiments, such as electroencephalography (EEG), galvanic skin response (GSR), and eye-tracking technologies, to accurately assess the specific impacts of multi-sensory design on spatial perception. In addition, future studies will apply the proposed design strategies to built projects, conducting evaluations through user or visitor data collection methods such as behavioral observations, questionnaires, interviews, and onsite studies. These findings are expected to provide data-driven support for designers, enabling more informed and evidence-based decision making in the design process;

- Refined control of multi-sensory design: Future research should delve into how to fine-tune the intensity and combination of sensory stimuli such as vision, hearing, touch, smell, and taste to avoid discomfort caused by overstimulation while enhancing the personalization and precision of sensory design. By incorporating findings from physiology, psychology, and neuroscience, studies can explore the “thresholds” of sensory stimuli and the optimal combinations, thus providing more tailored sensory experiences for different spatial environments and user needs;

- In-depth study of cross-cultural and individual differences: Individual differences such as cultural background, age, gender, and social roles have a significant impact on spatial perception. Future research should explore how these differences shape sensory experiences and tailor spatial design solutions to meet the needs of various groups. Additionally, studies should examine how different cultures have varying preferences for spatial design elements (such as color, sound, and scent), providing guidance for spatial design in a globalized context;

- Intelligent and personalized spatial perception design: With the advancement of artificial intelligence (AI), big data, and sensing technologies, future research should focus on exploring how to achieve personalized and adaptive spatial design through intelligent systems. By analyzing user behavior data and emotional feedback, smart systems can be designed to dynamically adjust spatial sensory elements (such as lighting, sound, temperature, etc.), thereby enhancing the interactivity and immersion of the space;

- Fusion of virtual and physical spaces: The rise of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) technologies has opened new avenues for spatial perception research. Future studies can explore how to integrate sensory experiences in virtual spaces with those in physical spaces, achieving a seamless transition between the virtual and real and creating an immersive experience that bridges both realms. This includes enhancing the realism of sensory simulations, such as touch, smell, and taste, in virtual spaces as well as optimizing the interactive experience between virtual spaces and the physical environment.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, K. The Interior Experience of Architecture: An Emotional Connection between Space and the Body. Buildings 2022, 12, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imrie, R. Architects’ Conceptions of the Human Body. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2003, 21, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallese, V. Embodied simulation: From neurons to phenomenal experience. Phenomenol. Cogn. Sci. 2005, 4, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G. The neuroscience of body memory: From the self through the space to the others. Cortex 2018, 104, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkerman, C.; Lenggenhager, B. The Body and Cognition: The Relation Between Body Representations and Higher Level Cognitive and Social Processes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Durão, M.J. Embodied space: A sensorial approach to spatial experience. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, Huntsville, AL, USA, 24–26 February 2009; pp. 399–406. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, J.-L.; Grimault, N.; Hupé, J.-M.; Moore, B.C.; Pressnitzer, D. Multistability in perception: Binding sensory modalities, an overview. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2012, 367, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phenomenology of Perception; Humanities; Routledge: London, UK, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, T. The circularity of the embodied mind. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, W.; vom Lehn, D. Introduction: The Senses in Social Interaction; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Turley, L.W.; Milliman, R.E. Atmospheric effects on shopping behavior: A review of the experimental evidence. J. Bus. Res. 2000, 49, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallasmaa, J. The sixth sense: The meaning of atmosphere and mood. Archit. Des. 2016, 86, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiné, K.; Demers, C.M.; Potvin, A. Spatio-temporal promenades as representations of urban atmospheres. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 42, 674–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Zheng, X. Understanding how multi-sensory spatial experience influences atmosphere, affective city image and behavioural intention. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2021, 89, 106595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, D. Multisensory anthropology. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2019, 48, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. Senses of place: Architectural design for the multisensory mind. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2020, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiss, T. The Experience of Place: A New Way of Looking at and Dealing With our Radically Changing Cities and Countryside; Vintage; Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, G.; Thibaud, J.-P. The Aesthetics of Atmospheres; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Michon, R.; Chebat, J.-C.; Turley, L.W. Mall atmospherics: The interaction effects of the mall environment on shopping behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, D. The Sense of Space; Suny Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, J.A. The Oxford English Dictionary; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, P. The Philosophy of “Being” and “Non-being”: From Laozi’s Philosophy to Tangible and Intangible Assets; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 1996. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ching, F.D. Architecture: Form, Space, and Order; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kandinsky, W. Point and Line to Plane; Dover Publications: Garden City, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Mende, K. Designing with Light and Shadow; Images Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, L. Light: The Shape of Space: Designing with Space and Light; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Berkeley, G. A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge; JB Lippincott & Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1881. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. Design Psychology, 2nd ed.; Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House: Shanghai, Shanghai, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman, H.R. Sensation and Perception: An Integrated Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Neisser, U. Cognitive Psychology: Classic Edition; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. Being and Time; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, S.; Okdeh, N.; Roufayel, R.; Kovacic, H.; Sabatier, J.-M.; Fajloun, Z.; Abi Khattar, Z. Neuroarchitecture: How the Perception of Our Surroundings Impacts the Brain. Biology 2024, 13, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadham, J. The Philosophy of Perception: Phenomenology and Image Theory; Oxford University Press UK: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pallasmaa, J. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jencks, C. Dimensions. Space, Shape and Scale in Architecture; JSTOR; Architectural Record: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomer, K.C.; Moore, C.W.; Yudell, R.J.; Yudell, B. Body, Memory, and Architecture; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Parnas, J.; Sass, L.A. Varieties of ‘phenomenology’. In Philosophical Issues in Psychiatry: Explanation, Phenomenology and Nosology; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2008; pp. 239–278. [Google Scholar]

- Shusterman, R. Body Consciousness: A Philosophy of Mindfulness and Somaesthetics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier, P. How brains beware: Neural mechanisms of emotional attention. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005, 9, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, M.M.; Rose, G. The sensory experiencing of urban design: The role of walking and perceptual memory. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 3271–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.M.; Chakrabarti, D.; Karmakar, S. Emotion and interior space design: An ergonomic perspective. Work 2012, 41 (Suppl. S1), 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masali, M.; Schlacht, I.L.; Micheletti Cremasco, M. Man is the measure of all things. Rend. Lincei Sci. Fis. E Nat. 2019, 30, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbusier, L. The Modulor: A Harmonious Measure to the Human Scale Universally Applicable to Architecture and Mechanics; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1954; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D.; Nettleton, S.; Buse, C. Affecting care: Maggie’s centres and the orchestration of architectural atmospheres. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 240, 112563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, T. Light design and atmosphere. Vis. Commun. 2015, 14, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandik, P. Action-oriented representation. In Cognition and the Brain: The Philosophy and Neuroscience Movement; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 284–305. [Google Scholar]

- Frascari, M. A Heroic and Admirable Machine: The Theater of the Architecture of Carlo Scarpa, Architetto Veneto. Poet. Today 1989, 10, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. The World of Perception; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Cui, M.; Yang, Y.; Yang, P.; Xie, C.; Liu, D.; Yu, B.; Chen, Z. Knowledge graph-based image classification refinement. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 57678–57690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception: Classic Edition; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Blazhenkova, O.; Kozhevnikov, M. Visual-object ability: A new dimension of non-verbal intelligence. Cognition 2010, 117, 276–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaglarz, A. Perception of color in architecture and urban space. Buildings 2023, 13, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, R.M. The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kielian-Gilbert, M. Musical Bordering, Connecting Histories, Becoming Performative. Music Theory Spectr. 2011, 33, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, L.E. On colored-hearing synesthesia: Cross-modal translations of sensory dimensions. Psychol. Bull. 1975, 82, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, R.M. The Tuning of the World: Toward a Theory of Soundscape Design; Destiny Books: Rochester, VT, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Gallace, A.; Spence, C. The science of interpersonal touch: An overview. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010, 34, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallasmaa, J. An Architecture of the Seven Senses. In Architecture and Urbanism–sTokyo; A+U Publishing Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 1994; pp. 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mattens, F. Perception, body, and the sense of touch: Phenomenology and philosophy of mind. Husserl Stud. 2009, 25, 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.-L.; Velázquez, R.; Del-Valle-Soto, C.; Gutiérrez, S.; Varona, J.; Enríquez-Zarate, J. Active and passive haptic perception of shape: Passive haptics can support navigation. Electronics 2019, 8, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P. Concrete: The Vision of a New Architecture; McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, C.; Gallace, A. Multisensory design: Reaching out to touch the consumer. Psychol. Mark. 2011, 28, 267–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachelard, G. The Poetics of Space; Janson, M., Translator; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, C.; Piqueras-Fiszman, B. The Perfect Meal: The Multisensory Science of Food and Dining; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, H.A. An Introduction to Space Perception; Longmans, Green and Co.: London, UK, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- McMullan, R. Environmental Science in Building; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- DeKay, M.; Brown, G. Sun, Wind, and Light: Architectural Design Strategies; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aksugür, E. Effects of surface colors on walls under different light sources on the perceptual magnitude of space in a room. In Proceedings of the Color 77: Proceedings of the 3rd Congress of the International Color Association, Kyoto, Japan, 10–15 July 1977; pp. 388–391. [Google Scholar]

- Babin, B.J.; Hardesty, D.M.; Suter, T.A. Color and shopping intentions: The intervening effect of price fairness and perceived affect. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayetoglu, M.L.; Yildirim, K.; Akalin, A. The effects of color and light on indoor wayfinding and the evaluation of the perceived environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahnke, F.H. Color, Environment, and Human Response: An Interdisciplinary Understanding of Color and Its Use as a Beneficial Element in the Design of the Architectural Environment; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zumthor, P. Atmospheres: Architectural environments. surrounding objects. In Atmospheres; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Dewancker, B.J. The influence of Zen Buddhism and ink wash painting on Japanese gardens during the medieval Japan. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Tan, Z.; Sun, P. Research on Wind Environment Simulation in Five Types of “Gray Spaces” in Traditional Jiangnan Gardens, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumthor, P. Thinking Architecture; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Roos, A. Swiss Sensibility: The Culture of Architecture in Switzerland; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Treisman, A.M.; Garry, G. A feature-integration theory of attention. Cogn. Psychol. 1980, 12, 97–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, D.M. Modernity and the Hegemony of Vision; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, G.H. Color testing and the psychology of color. Am. J. Psychol. 1924, 35, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.D. Arousal properties of red versus green. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1966, 23, 947–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’andrade, R.; Egan, M. The colors of emotion 1. Am. Ethnol. 1974, 1, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; Maier, M.A. Color psychology: Effects of perceiving color on psychological functioning in humans. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagtvedt, H.; Brasel, S.A. Color saturation increases perceived product size. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 44, 396–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhme, G. Atmosphere. Open Philos. 2021, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, W.S.; Cleveland, W.S. A color-caused optical illusion on a statistical graph. Am. Stat. 1983, 37, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, C.; Muscio, A.; Siligardi, C.; Manfredini, T. Design of a cool color glaze for solar reflective tile application. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 11106–11116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M. Comparative studies on color preference in Japan and other Asian regions, with special emphasis on the preference for white. Color Res. Appl. 1996, 21, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manav, B. Color-emotion associations and color preferences: A case study for residences. Color Res. Appl. 2007, 32, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, P. An approach to phenomenological psychology: The contingencies of the lifeworld. J. Phe-Nomenological Psychol. 2003, 34, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalke, H.; Little, J.; Niemann, E.; Camgoz, N.; Steadman, G.; Hill, S.; Stott, L. Colour and lighting in hospital design. Opt. Laser Technol. 2006, 38, 343–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornsweet, T. Visual Perception; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Huff, W.S. Kahn and Yale. J. Archit. Educ. 1982, 35, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bellia, L.; Bisegna, F.; Spada, G. Lighting in indoor environments: Visual and non-visual effects of light sources with different spectral power distributions. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 1984–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C. A study of the emotional impact of interior lighting color in rural bed and breakfast space design. Buildings 2023, 13, 2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarter, R. The Space Within: Interior Experience as the Origin of Architecture; Reaktion Books: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hedfors, P. Site Soundscapes: Landscape Architecture in the Light of Sound; Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences: Uppsala, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bregman, A.S. Auditory Scene Analysis: The Perceptual Organization of Sound; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Blesser, B.; Salter, L.-R. Spaces Speak, Are You Listening: Experiencing Aural Architecture; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007; Volume 232. [Google Scholar]

- Robart, R.L.; Rosenblum, L.D. Hearing space: Identifying rooms by reflected sound. In Studies in Perception and Action VIII; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2023; pp. 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, M.M.; Lang, P.J. Affective reactions to acoustic stimuli. Psychophysiology 2000, 37, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, J.A. The value of natural sounds. J. Aesthetic Educ. 1999, 33, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augoyard, J.-F. Sonic Experience: A Guide to Everyday Sounds; McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann, M. Felt Time: The Psychology of How We Perceive Time; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kenwright, B. There’s more to sound than meets the ear: Sound in interactive environments. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 2020, 40, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Globa, A.; Beza, B.B.; Wang, R. Towards multi-sensory design: Placemaking through immersive environments–Evaluation of the approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 204, 117614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, M. The Senses of Touch: Haptics, Affects and Technologies; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Song, X.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, Y. Recent progress in biomimetic additive manufacturing technology: From materials to functional structures. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1706539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Tait, M.; Kang, J. Understanding smellscapes: Sense-making of smell-triggered emotions in place. Emot. Space Soc. 2020, 37, 100710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. A new multisensory approach to health and well-being. Essence 2003, 2, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, S.T.; Heuberger, E. Effects of a pleasant natural odor on mood: No influence of age. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 1934578X1601101033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrin, M.; Ratneshwar, S. Does it make sense to use scents to enhance brand memory? J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell, C.; Sell, C.S. The Chemistry of Fragrances: From Perfumer to Consumer; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Herz, R.S. Aromatherapy facts and fictions: A scientific analysis of olfactory effects on mood, physiology and behavior. Int. J. Neurosci. 2009, 119, 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerruish, E. Arranging sensations: Smell and taste in augmented and virtual reality. Senses Soc. 2019, 14, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Downes, J.J. Proust nose best: Odors are better cues of autobiographical memory. Mem. Cogn. 2002, 30, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, A.A. The Suzhou industrial park experiment: The case of China–Singapore governmental collaboration. J. Contemp. China 2004, 13, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masheck, J. Adolf Loos: The Art of Architecture; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.J. The theory of affordances: (1979). In The People, Place, and Space Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Herz, R.S.; Jonathan, W.S. A naturalistic study of autobiographical memories evoked by olfactory and visual cues: Testing the Proustian hypothesis. Am. J. Psychol. 2002, 115, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, N. Tactile sensation via spatial perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2003, 7, 285–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, M.R.; Haggard, P. Implicit body representations and the conscious body image. Acta Psychol. 2012, 141, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, C.; Puccinelli, N.M.; Grewal, D.; Roggeveen, A.L. Store atmospherics: A multisensory perspective. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 472–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madzharov, A.V.; Block, L.G.; Morrin, M. The cool scent of power: Effects of ambient scent on consumer preferences and choice behavior. J. Mark. 2015, 79, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlichman, H.; Halpern, J.N. Affect and memory: Effects of pleasant and unpleasant odors on retrieval of happy and unhappy memories. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 55, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theoretical Concept | Core Idea | Corresponding Design Expression |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Perception | Space is rendered experiential through bodily movements, spatial orientations, and perceptual thresholds. | Design of perceptual nodes through spatial scales, circulation paths, visual axis organization, and rhythmic transitions |

| Phenomenology of Perception | Space is perceived directly through the embodied experience. | Tactile qualities of materials and interface interactions; pre-reflective spatial cues (e.g., light and shadow variations and temperature differences); and slow-paced circulation and moments of pause |

| Five Senses Framework | Human experience of space is mediated by the interaction of the five senses. | The integration of five-sense design, sensory zoning with hierarchical organization, and the construction of cross-modal memory and emotional resonance |

| Affective Atmosphere Theory | Atmosphere is shaped through sensory modulation, forming an emotional field. | Design details involving the rhythm and temporal control of soundscapes, color temperature and light–dark contrast, scent diffusion and memory activation, and the emotional resonance of materials |

| Site | Role | Explicit Description | Photos (Source: Internet) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pantheon (the heart of Rome, Italy) | Natural light as a key element in enhancing the visual focal points within a space | The large circular opening at the top of the Pantheon serves as the sole source of natural light within the interior. The angle of light shifts in response to the sun’s movement, causing the focal point of illumination to change at different times of the day. This dynamic interaction between light and space effectively transforms the building into a functional sundial, offering a perceptual experience deeply connected to the passage of time. As light plays a pivotal role in visual focus within the space, it not only enhances the visual depth and spatial hierarchy but also amplifies the sanctity and solemnity of the Pantheon as a place of worship. |  |

| Photo source: The image has been authorized by the author Anso Lighting Design. | |||

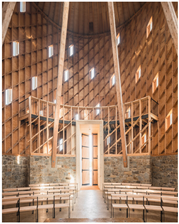

| Church of Our Lady of Nesvacilka (Nesvačilka-Těšany 664 54, Czech Republic) | Natural light as a key element in enhancing the visual focal points within a space | The light in the Church of Our Lady primarily enters through the side windows. The orientation and placement of these windows are carefully designed to ensure that sunlight illuminates specific areas at different times of the day, particularly the altar and religious icons. In this way, the light naturally focuses on these central religious elements, making them visually prominent and guiding the congregation’s attention towards these sacred objects. This design not only enhances the visual emphasis of the religious focal points but also strengthens the solemnity of the religious rituals, reinforcing the spiritual significance of the space. |  |

| Photo source: The image has been used with permission from the author, Ondřej Bouška, 2024. | |||

| Zhejiang Li shui Office Headquarters (top floor of office building in Li shui, Zhejiang) | Natural light as an element that enriches spatial depths and visual experiences | In the design of the Zhejiang Li shui Office Headquarters, the courtyard’s daylighting is achieved through a rotating louvered skylight, allowing natural light to filter through and cast dappled shadows across the space. This interplay of light contrasts with the traditional architectural elements of the old arcade, establishing a dialog between the past and the future. The design not only enriches the spatial layers but also enhances the visual experience, creating a dynamic connection between historical and contemporary architectural features. |  |

| Photo source: The image has been authorized by the author Xun Chang Design. | |||

| Chapel of Light (Ibaraki City, located on the outskirts of Osaka Castle) | Natural light as a means of creating spatial ambiance | In Tadao Ando’s design, light is not merely a functional source of illumination but a crucial element in shaping the spatial atmosphere. A horizontal cross-shaped slit is incorporated into the church’s front wall, allowing sunlight to filter through at specific times of the day. This light forms a cross-shaped pattern on the interior, symbolizing Christian faith and the arrival of divine light. The cross-shaped light serves as a symbol of sacred power, suggesting the presence and revelation of God, thus enhancing the church’s religious ambiance and the sense of ritual. |  |

| Photo source: The image has been authorized by the author Visual China. | |||

| Louis Kahn’s Exeter Library (Exeter, New Hampshire, USA) | Natural light as a means of creating spatial ambiance | Louis Kahn’s Exeter Library uses natural light to create a unique spatial atmosphere. Skylights in the roof direct light into the central hall, fostering a bright, serene environment that blends with nature. Large windows in the reading areas allow sunlight to filter in, creating a warm ambiance, while carefully designed shading elements prevent glare. As the light changes throughout the day, the library’s atmosphere evolves, with varying sunlight angles at different times, offering distinct esthetic and emotional experiences. |  |

| Photo source: The image has been authorized by the author Chris Peng. |

| Design Dimension | Before Renovation | After Renovation |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Layout | Linear and utilitarian | Multi-layered circulation with spatial rhythm |

| Lighting | Uniform artificial lighting | Integration of natural skylights, directed artificial lighting, and temporal variation |

| Acoustic Environment | Industrial noise or silence | Soundscape design and interactive sound |

| Material and Tactility | Exposed concrete and emulsion-painted wall | Warm natural materials combined with rose gold metal finishes and rich tactile interfaces |

| Scent and Taste Design | None; no olfactory or gustatory cues present | Coffee aroma diffusion, scent-zoned areas, and sensory–emotional pairing |

| Circulation and Accessibility | Vertical, disconnected movement limited to staircases | Horizontally connected, guided pathways enhancing spatial continuity |

| Emotional Atmosphere | Neutral, emotionally detached | Immersive, emotionally engaging with sensory layering |

| User Experience (Expected Impact) | Passive, functional use; low engagement | Active, exploratory, and memory-forming experiences |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, H.; Zhao, J.; Jin, C.; Zhu, N.; Chai, Y. Research on the Multi-Sensory Experience Design of Interior Spaces from the Perspective of Spatial Perception: A Case Study of Suzhou Coffee Roasting Factory. Buildings 2025, 15, 1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081393

Xu H, Zhao J, Jin C, Zhu N, Chai Y. Research on the Multi-Sensory Experience Design of Interior Spaces from the Perspective of Spatial Perception: A Case Study of Suzhou Coffee Roasting Factory. Buildings. 2025; 15(8):1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081393

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Haochen, Jinxiang Zhao, Changjiang Jin, Ning Zhu, and Ye Chai. 2025. "Research on the Multi-Sensory Experience Design of Interior Spaces from the Perspective of Spatial Perception: A Case Study of Suzhou Coffee Roasting Factory" Buildings 15, no. 8: 1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081393

APA StyleXu, H., Zhao, J., Jin, C., Zhu, N., & Chai, Y. (2025). Research on the Multi-Sensory Experience Design of Interior Spaces from the Perspective of Spatial Perception: A Case Study of Suzhou Coffee Roasting Factory. Buildings, 15(8), 1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081393