1. Introduction

The American criminal justice system experience is one tightly intertwined with money. Individuals involved in the system often find themselves at the mercy of multiple agencies requiring payment in the form of various monetary sanctions. Nationally, amounts can be charged for services such as using a public defender in 43 states, for room and board for jail and prison inmates in 41 states, and for electronic monitoring services in 49 states (

Shapiro 2014). These practices are expanding nationwide as well, both in the number of services that trigger fines and fees and, in the amounts associated with each type (

Menendez et al. 2019). This is not a new phenomenon but rather a tradition upon which the system was founded. Debtor’s prisons, early workhouses, and convict leasing systems are just a few examples of practices that laid the foundation for the financial exploitation of correctional clients seen in the modern era (

Hampson 2017). Still today, those found guilty by the court of committing a crime are often subjected to fees, punitive fines, or restitution—payment to victims for damaged or stolen property—in amounts that often outweigh what many are reasonably able to pay. One such avenue through which correctional clients experience these monetary obligations is community corrections, especially probation and parole. The current study will investigate the community corrections–financial sanctions nexus through the lens of recent policy developments in Massachusetts. We draw on surveys gathered from probation officers to illustrate how reforming financial sanctions policies can impact community supervision operations and possibly allay the injustices associated with this controversial tradition.

2. Background

While under community supervision, supervisees (e.g., persons on probation or parole) must adhere to system-imposed conditions, including stipulations about monies that must be paid. It is standard practice within community corrections across the U.S. to require supervisees to pay fees. These fees are different from fines or restitution in that they are costs supervisees must pay, usually monthly, for their probation or parole as well as other associated fees, such as for court, programming, drug testing, and electronic monitoring. Fines and restitution, on the other hand, are usually ordered for punitive or restorative purposes, respectively. Specifically, fines are often levied on supervisees as part of their original sentencing but sometimes also for infractions such as failed drug screens or an inability to meet other court-ordered requirements of supervision. These may be a one-time payment or recurring, but they differ from fees in that they are finite in nature. Revenue collected from fines and fees plays an integral role in the funding and operation of the institutions involved in their application. In fact, research has uncovered widespread expansion of fines and fees application in recent years in order to support continued revenue generation (

Fernandes et al. 2019). From personnel salaries to building maintenance costs to services offered to clients, the courts and community corrections agencies benefit greatly from the collection of fines and fees from supervisees.

While courts and agencies benefit, many supervisees are disadvantaged. Justice system clients are disproportionately more likely to come from economically strained backgrounds, experience poverty, and struggle to find and keep gainful employment (

Farrington 1995;

Western et al. 2001). Financial obligations have the potential to create a host of challenges that undermine rehabilitation, such as eroding rapport between the supervision officer and the client, adding to their financial hardships, and making it difficult to fulfill the conditions of their probation or parole (

Ruhland 2021). These are often exacerbated as additional fines and/or interest accrue

on top of original amounts owed when they go unpaid. Some supervisees may elect not to pay or be incapable of paying fines and fees within the confines of their lawful income. Those who fail to make timely payments sometimes avoid justice system actors (e.g., probation or parole officers, judges) for fear that they might receive additional sanctions or be arrested for nonpayment. These supervisees may elect to miss meetings with supervision officers or skip court appearances, further worsening their legal trouble (

Beckett and Harris 2011;

Ruhland 2021). Perhaps worse, those that cannot make payments may pursue illegal channels to increase income to ease the financial burden (

Ruhland 2021). In the event of nonpayment, some agencies file civil judgments, send delinquent payments to collection agencies, and even incarcerate supervisees for failure to pay fines or fees, which are responses that are antithetical to rehabilitation.

Many of the policies and practices surrounding fines and fees in community corrections are longstanding. Nevertheless, research investigating the effects of these policies is only recently gaining steam. Much of this recent literature points to increasingly troubling trends that call attention to the need for continued investigation and reform. In a study using a sample of adolescents,

Piquero and Jennings (

2017) found that the application of higher amounts of financial sanctions increased the likelihood of recidivism—reoffending—among their sample, pointing to the incongruence between rehabilitation and fines and fees, which is an assertion shared by other scholars recently (

Ruhland et al. 2021). This finding partially aligns with those from a recent study by

Ruhland et al. (

2020) who reported that higher amounts of fees (but not fines) were associated with a higher likelihood of probation revocation among a sample of adult probation clients. Concerningly, the authors also report that higher amounts of fees were assessed for unemployed probation clients, compared with those employed full time. Taken together, these findings suggest that fines and fees can have detrimental effects on justice system clients’ abilities to achieve successful outcomes.

This points to a larger issue of the legal debt and poverty nexus. Specifically, scholars have found that monetary sanctions can lead to poverty by reducing income and creating long-term debt (

Beckett and Harris 2011). Similarly worrying are racial disparities in the application of fines and fees and the associated consequences for nonpayment.

Martin et al. (

2018) have drawn connections between monetary sanctions and increases in social stratification along racial and socioeconomic lines. The authors also describe the potential consequences of lofty legal debts, which include suspension of driver’s licenses, damaged credit, restrictions on voting rights, and even incarceration, all which have the capacity—both solely and collectively—to further exacerbate legal involvement. In short, the recent body of literature surrounding monetary sanctions points to their complicated relationship with rehabilitative goals, their likelihood to be disproportionately applied to disadvantaged segments of the population, and their potential to create and intensify poverty and political disenfranchisement among those same segments. Some jurisdictions have taken note of these troubling discoveries and implemented policies to help ensure an equal application of justice.

In Massachusetts, nonpayment of fines and fees is something that, until recently, was dealt with quite harshly. Individuals who complied with all other court-ordered requirements except payment of outstanding fines and fees could be incarcerated for solely this reason. Called “fine time”, this practice drew an onslaught of criticism, which spurred elected officials to action, eventually leading to the passing of a pivotal criminal justice reform bill in 2018. As a result, fewer cases of nonpayment end in incarcerating correctional clients. Instead, financial waivers are granted when clients are unable to pay, effectively converting their fines and fees into community service or other suitable alternatives. On its face, this reform effort seems to be a great leap forward in the pursuit of a more just legal and correctional system. For community supervision, these changes give supervisees more options in dealing with expectations of the court and the supervision officers to which they report. Likewise, those officers have more tools for helping their clients avoid unnecessary legal complications while still enforcing conditions that hold supervisees accountable for their own rehabilitation.

3. The Current Study

Given the implications that reform efforts such as these have for community corrections practices, supervision officers’ amenability to embracing these reforms warrants further investigation. To that end, the goal of the current study is to examine supervision officers’ attitudes and behaviors regarding fines and fees practices amid criminal justice reform. In doing so, the current study relies specifically on Massachusetts as a case study for reforming such practices. We first chronicle the factors that prompted the reform bill before detailing the changes specified in the bill, with a special focus on those portions that impacted fines and fees practices. Then, we summarize the annual changes in Massachusetts probation and courts revenue and operating budgets as they relate to fines and fees. Then, drawing on survey data collected from a sample of Massachusetts probation officers in 2020 when the reform bill was in effect, we describe their reported attitudes and behaviors pertaining to fines and fees collection practices. Finally, we conclude by speculating the policy impacts on people on probation and the implications that Massachusetts reform may have for other states.

4. The Evolution of Massachusetts Fines and Fees Policies

4.1. Fine Time

In Massachusetts, “fine time” is a colloquial term given to the controversial practice of incarcerating defendants who, aside from having outstanding unpaid balances with the court, have no unresolved legal issues that would warrant such a response. In other words, Massachusetts courts were incarcerating individuals solely for their inability to pay court-ordered financial obligations on time. These financial obligations derive from a variety of sources, such as counsel fees associated with indigent defense, court costs, probation fees, victim/witness assessments, and default-related fees stemming from default warrant arrests (

Senate Committee on Post Audit and Oversight 2016). Their incarceration sentences were served at the rate of one day for every

$30 owed—a rate that had not been updated since 1987 (

Boston Bar Association 2017). This meant, for example, that an individual who owed the court

$300 would be sentenced to serve ten days in jail–with greater amounts yielding longer sentences–after which the owed balance would be fully resolved. This heavy-handed response to nonpayment was the direct embodiment of the drive to collect revenue from justice-involved people, seemingly at whatever cost. Fine time had the potential to be extremely disruptive to the lives of those affected and especially detrimental to the poorest of court clients. Although the practice presented obvious dangers to civil rights and liberties, it went relatively unnoticed for decades.

The troubling realities of fine time came to light when the Massachusetts Senate Committee on Post Audit and Oversight (hereafter SCPAO) launched its inquiry in 2015 into the policies surrounding financial sanctions levied by Massachusetts’s justice system. The inquiry and subsequent audit came amid a national awakening. Across the U.S., media outlets, vocal attorneys, other court personnel, and advocacy groups began speaking out about lofty court and correctional debts and the policies put in place to collect them. Massachusetts was not the only state in the nation to carry out something similar to fine time, and many pundits likened these policies to modern day debtor’s prisons (

Foster 2020;

Kurtz 2015;

Rappleye and Seville 2014). Along with these associations, there was a growing understanding of the disproportionately damaging implications of financial obligations when imposed on poorer individuals and people of color (

Shapiro 2014). Massachusetts-specific publications called attention to the disparate and inconsistent application of probation fees, waivers, and community service requirements (

Cutts 2016;

Sawyer 2016;

Wade 2016;

Office of State Auditor 2016). The consensus surrounding the state of fines and fees policies in the U.S. generally and Massachusetts specifically was that a recalibration was needed.

The SCPAO’s inquiry came initially as a result of these calls for a need for recalibration and then later became a driving force in the argument for its necessity. The committee was able to collect verifiably complete data from three Massachusetts counties—Essex, Plymouth, and Worcester—for all cases in which individuals were sentenced to fine time during 2015. This yielded a sample of 105 cases. The audit uncovered a handful of noteworthy trends. According to the resulting report, in all but 16% (17) of cases, the initial charge that brought the defendant before the court was relatively minor, with 40% (42) being brought initially on traffic violations of some kind (

Senate Committee on Post Audit and Oversight 2016). The sources of debt were investigated as well. It was found that in 70% (73) of the 105 cases, defendants were assessed administrative fees relating to warrant removals (

$50) and/or arrests (

$75). In half of cases (N = 53), defendants had incurred a

$150 fee for their court-assigned counsel. In 30% (31) of cases, clients owed court costs ranging from

$50 to

$500. Victim/witness assessments for

$50 or

$90 were ordered in over one-third of the cases. In 19% (20) of cases, probation fees were ordered in the amount of either

$65 or

$50 monthly. Total amounts owed ranged from

$30 to

$3,384, with over one-third (

n = 38) of cases owing more than

$500 and 10% (11) of cases owing more than

$1000 (

Senate Committee on Post Audit and Oversight 2016). Time ordered to be served for nonpayment ranged from one to 112 days in jail. Nearly half of the sample (

n = 48) was ordered to serve two weeks or more.

The committee’s report was illuminating in that it provided Massachusetts policymakers with evidence that not only was fine time utilized regularly, but it was also routinely triggered by administrative costs and fees. These costs and fees were not borne from the rehabilitative or restorative goals of the court and corrections systems but were instead anchored in the drive to collect revenue to supplement operating costs. In courts’ efforts to collect revenue, they were incarcerating defendants for stints that were arguably much longer than could be deemed reasonable, and they were abandoning the foundational motivations for their operation. Taking note of these troubling findings, Massachusetts officials worked to find a better way of addressing instances of nonpayment within the justice system.

4.2. The Reform Bill

The Office of Governor Charles Baker submitted legislation to the Massachusetts Senate and House of Representatives on 11th April 2017—about six months after the audit report was released. The accompanying letter written by Governor Baker said that the report showed “that the present system lacks adequate safeguards to protect individuals’ rights and leads to unjust outcomes” (

An Act Reforming Fine Time 2017, p. 1). To curtail these and other breaches of justices, the legislation included provisions addressing the Massachusetts criminal justice system broadly. Namely, the legislation proposed extending the procedural rights of juveniles in the justice system, creating a fairer and more equitable bail system, and establishing procedures for better record keeping, sharing, and oversight. It also outlined new mandatory sentencing for certain offenses, namely the manufacture and distribution of specific controlled substances. Additional sections proposed standardizing certain police-training efforts and limiting the unnecessary use of restrictive or solitary confinement within correctional facilities. More relevant to the scope of the current study, fine time policies would be altered to ensure that only those who willfully decide not to pay fines and fees would be subject to incarceration for solely that reason; those that cannot reasonably pay outstanding balances may petition to convert their fines and fees to community service hours. In addition, the legislation would increase the daily rate of jail incarceration for debt resolution from

$30 to

$90, still allowing for fine time (

An Act Reforming Fine Time 2017). Governor Baker’s proposed changes became part of a lengthy deliberation before it finally passed in April 2018—nearly a year after the original legislation was submitted to the House and Senate (

Young 2018). Despite extensive negotiations, the bill was passed with no opposition in the Senate, and with a 145-5 vote in the House. Governor Baker signed the bill into law on 13th April 2018 (

An Act Relative to Criminal Justice Reform 2018).

These developments were crucial in the state’s push for a fairer application of justice and brought some key changes to fines, fees, and restitution policies. For example, individuals who demonstrate their inability to pay money owed can no longer be incarcerated for solely this reason, provided it can be proven by a preponderance of the evidence that paying would cause substantial financial hardship for the person, their immediate family, or dependent children. Additionally, individuals cannot be incarcerated for nonpayment if they were not represented by counsel for the commitment proceeding unless counsel was waived. Notably, the bill expressly gives courts the right to consider alternatives to incarceration for nonpayment, such as community service. Courts are also now prohibited from committing any person under the age of 18 to a correctional facility for nonpayment, regardless of the person’s ability to pay. Those sent to correctional facilities for nonpayment are now able to petition the court for discharge, further distancing Massachusetts from its previous debtor’s prison similarities.

In addition to courts’ responses to nonpayment, certain sections also lay out stipulations for waiving financial obligations altogether. Regarding restitution, courts now have the right to grant complete remission from payment and can opt not to order restitution at all if the defendant is deemed indigent. As with restitution, administrative fees may now also be waived, including those associated with warrant recalls. Monthly probation and parole fees can be waived if the potential for financial hardship is established as well; the bill outlines provisions substituting these fees with community service hours not to exceed four hours per month. Certain stipulations were made regarding the timeline of assessment of probation and parole fees as well. For the first six months and first year following release from prison, monthly fees will not be assessed for probation and parole, respectively. Notably, all waivers only apply for as long as payment of fines, fees, and restitution would cause substantial hardship. Finally, in an effort to minimize instances of surprise incarceration, individuals who are assessed fines, fees, costs, or civil penalties must be informed that they risk being confined in the event of nonpayment.

4.3. Revenue

The changes to fines and fees policies within the reform bill represent strides toward a fairer justice system, but they might present some obvious implications for affected agencies. The courts and correctional systems within Massachusetts had been collecting payments from clients to help supplement operating budgets for many years. However, given that the recent reform bill limits the reach of collection policies, agencies may need to adapt to shifting revenue sources. The numbers suggest that this may be happening, even if the impacts are minimal. During the fiscal year 2016, Massachusetts courts collected

$20.2 million in probation fees. That number dropped to

$17.8 million during the fiscal year 2017,

$16.5 in 2018,

$13.8 in 2019, and

$10.6 in 2020 (

Massachusetts Court System 2016,

2017,

2018,

2019,

2020). During this five-year span, revenue collected through probation fees alone was cut nearly in half. To place these figures in context, probation fees represented about 3.2% of the courts’ total operating appropriation during 2016, eventually dropping to just 1.4% in 2020. Despite the net decrease in revenue raised through probation fees, total operating budgets increased from

$621.5 million to

$742.7 million during this time.

These numbers suggest some important patterns. Although the absolute change in revenue collected through probation fees represents a loss of millions of dollars, the amount is inconsequential when considered alongside the total operating budget of the Massachusetts Court System. In the face of such a relatively small decrease in one revenue stream, the court system is likely able to compensate by reallocating funds to cover the loss when crafting annual budgets. Possibly negating this point altogether is the fact that total operating allocation for the court system increased by over $120 million during these five years—over 12 times the amount lost through probation fees. This calls into question whether the impact of the reform on operating budgets was ever a concern of policymakers. Plummeting revenue from probation fees—even though it seemed to be decreasing before the bill was passed—possibly signals a true change in the way courts and associated personnel are operating. Namely, financial waivers are likely being applied in a much wider range of cases. In short, the reform bill seems to be taking hold and allowing courts the flexibility to adjust the way they handle financial sanctions.

4.4. The Probation Officer

Probation officers are gatekeepers between persons on probation and the court. Often, their assessment of the probation client and testimony before the court significantly impact the supervision experience. Given their unique influence in community supervision, it is critical to understand how they integrate and apply these policies pertaining to fines, fees, and waivers into their work. In light of this, the current study aims to assess the attitudes and perceptions of probation officers in Massachusetts pertaining to fines and fees. Furthermore, we wish to investigate the role that probation officers play in the application of financial waivers, including in what types of cases waivers are requested and granted in Massachusetts following the landmark reform. To address these pursuits, the current study offers a descriptive analysis of survey data gathered from a sample of Massachusetts probation officers in 2020.

5. Methods

5.1. Data

In September and October of 2020, the research team administered a research survey to Massachusetts probation officers with the goal of investigating the impacts of fines and fees in community corrections. The research team developed the survey instrument by consulting relevant literature and identifying key concepts to be measured. Using a master email list from the Massachusetts Probation Service, researchers invited officers to participate in the survey containing questions about their roles, experiences, and attitudes pertaining to fines and fees. Officers were eligible to participate if they supervised adult probation clients and worked for the district or superior court. Exactly 449 probation officers met these eligibility requirements and received three email invitations to complete the survey over the course of two weeks. The research team elicited and compiled the survey responses using Qualtrics. Of the 449 eligible probation officers, 185 submitted responses, yielding a response rate of 41%. Of the submitted questionnaires, 23 (12%) officers elected not to participate, and of the remaining 162, a further five (3%) offered no responses to any items on the questionnaire, and 36 (22%) only provided some responses, omitting data on key study measures. Ultimately, 121 (65%) returned questionnaires that were deemed suitable for inclusion in the final sample.

5.2. Measures

To address the posed research questions, we analyze two types of survey measures of relevance to the 2018 reform bill: (1) officers’ attitudes and perceptions of fines and fees operations and (2) officers’ actual actions concerning fines and fees practices.

5.2.1. Attitudes and Perceptions

Survey items pertaining to attitudes and perceptions asked officers to provide responses to Likert-type questions that gauged their attitudes toward goals and objectives placed on supervisees and their degree of agreement with a host of statements pertaining to fines, fees, and nonpayment of both. Additionally, respondents were asked to indicate the amount of emphasis that they, their supervisors, and their agency placed on fee collection. The responses to these measures, when taken together, inform our understanding of probation officers’ outlooks on the nature of their work and the conventional practices of probation services pertaining to financial obligations placed on their supervisees. These outlooks serve as lenses through which officers make discretionary decisions, further influencing how they might respond to changes in policy such as those brought forth in the recent Massachusetts reform bill.

5.2.2. Probation Officers’ Actions

The survey also included items that allowed for the assessment of officers’ actions pertaining to fines and fees. These items asked respondents to indicate which steps they or their agency took when handling cases of nonpayment by supervisees. This measure also included survey items that asked respondents about their use of assessments to determine supervisees’ ability to pay and the factors on which those assessments were based. Lastly, survey items that asked respondents how often they request financial waivers and how often those waivers are granted were included. These items provide insight into the role that probation officers have in the application of financial waivers and how their decisions within that role are made. This measure of respondents’ actions and the reported actions taken by their agency provide a way to assess how probation work is being carried out two years after the landmark reform bill was enacted.

5.3. Sample

Descriptive information about the sample is found in

Table 1. When asked how they identified, 44% responded that they identified as male and 50% responded that they identified as female. The sample was predominantly White, with 79% indicating as such. Black or African American respondents made up 7% of the sample, and just 3% responded that they were of other races. Only 5% of respondents indicated being of Hispanic ethnicity. Nearly all (96%) reported holding a 4-year degree, graduate degree, and/or professional degree. Among the sample, 70% reported being officers, 17% were supervisory officers, 8% were higher-level administrators, and 4% reported working in some other capacity within the Probation Service, such as a case specialist or an intermediary officer rank that was not captured by the other three categories. Few respondents reported having minimal experience within their role. Only 2% had less than six months of experience, and 4% had between six and 11 months. Most had quite a bit more experience within their role, with 12% reporting between one and three years, 28% had between three and five years, 18% had between five and ten years, 10% had between ten and 20 years, and 26% had over 20 years.

5.4. Analytic Plan

Data were exported to SPSS for analysis. Given the descriptive nature of the current study’s research questions, the analysis is comprised of univariate statistics. Frequency tables report the results of these analyses. Additionally, to illustrate salient patterns in the data, graphical representations are shown.

6. Findings

6.1. Officer Attitudes toward Fines and Fees

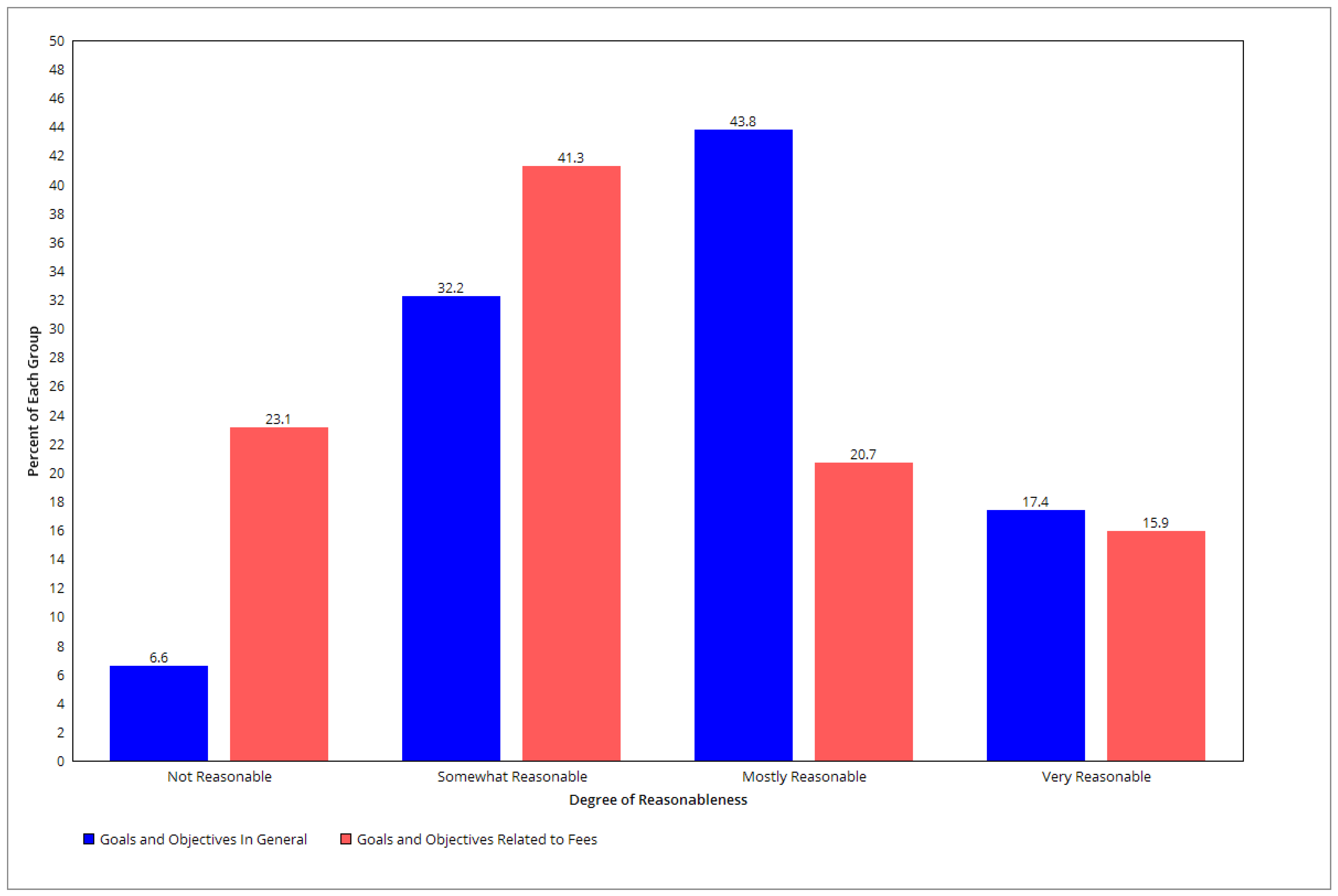

Officer attitudes toward fines and fees goals and objectives placed on supervisees are presented first. Overall, respondents seem pessimistic about supervisees’ ability to meet financial obligations while on probation. As shown in

Figure 1, officers were much more likely to indicate that goals and objectives relating to fees are not reasonable or only somewhat reasonable. Approximately 23% of respondents found these goals and objectives not reasonable, 41% found them somewhat reasonable, 21% found them mostly reasonable, and 16% found them very reasonable. For comparison and context, we included a measure that captures their views of supervision goals and objectives in general, in which officers reported being either mostly or somewhat reasonable. Regarding these general goals and objectives, just 7% found them not reasonable, 32% found them somewhat reasonable, 44% found them mostly reasonable, and 17% found them very reasonable. This suggests that officers find financial goals and objectives less reasonable, specifically, relative to goals and objectives pertaining to the supervision process more generally. Officers continue to struggle to reconcile with the financial expectations placed on their supervisees, even if they are indifferent about general expectations otherwise.

The current study seeks to assess probation officers’ attitudes and perceptions of fines and fees charged by their agency, which would theoretically impact the way they make discretionary decisions surrounding their clients’ financial obligations and sanctions in situations of nonpayment. The results of these items are found in

Table 2. In some cases, respondents appeared to agree that a gentler approach to fines and fees is ideal. Most respondents agreed or strongly agreed that fines and fees should be waived for very poor supervisees (78%) and that they are too high for most supervisees to afford to pay (63%). Similarly, most disagreed or strongly disagreed that fines and fees should accrue interest and late fees (91%), that they are perceived as fair and reasonable among supervisees (64%), that they should lead to supervision violations (62%), and that not paying them on time should extend the period of supervision until they are paid off (59%). However, despite general consensus about these sentiments, officers were more mixed in their attitudes about others. For example, officers most commonly strongly disagreed or disagreed that the amounts are fair to ask supervisees to pay, although only 43% indicated so. Similarly, officers most commonly strongly agreed or agreed when asked if fees negatively impacted family or friends of supervisees (40%), make it more difficult for supervisees to pay for their daily needs (47%), make it harder for supervisees to remain crime free (36%), and should lead to other sanctions when not paid on time (43%). In no instance did a majority of the sample strongly agree or agree with a punitive response to nonpayment. This finding suggests that most officers’ attitudes align with the recent policy reforms concerning financial sanctions.

Results pertaining to the amount of emphasis that respondents reported being placed on fee collection by themselves, their supervisors, and their agencies is found in

Figure 2. Overall, respondents tended to report placing only some emphasis on fee collection (55%). Only six (5%) reported placing a lot of emphasis on fee collection. In contrast, most officers reported their supervisors as placing a lot (25%) or a good amount (39%) of emphasis and their agency as placing some (42%) or a good amount (39%) of emphasis on fee collection. Together, these results highlight incongruence between officer emphasis and supervisor and agency emphasis on the importance of fee collection. This illustrates the relatively minor role that officers perceive fees play in the supervision process, strengthening the trend being set among respondents that lower intensity in the application and collection of fees is a favorable outcome for supervisees. This lends further support to the notion that officers agree with the impacts of the reform bill on the financial practices of courts and probation services.

6.2. Officer Actions Pertaining to Fines and Fees

6.2.1. Response to Nonpayment

Although individual officers may have attitudes congruent with the recent reform bill, sentiments may not always translate into actions. To better understand procedural practices, we examine a variety of officers’ self-reported responses in instances of nonpayment of fees by supervisees, which are displayed in

Table 3. The results indicate a strong compliance with the policy prioritization of non-punitive reactions to nonpayment. An overwhelming majority (85%) of respondents reported waiving fees or asking the court to waive fees in instances of nonpayment. This was the modal response. Nearly as unanimous was filing a violation (78%) and requiring community service (76%) for nonpayment. Most of the sample also indicated that they created or revised a payment plan with supervisees (66%) and extended the length of supervision (54%). By far, the least common actions taken were the most punitive of options: revoking supervision (7%) and sending unpaid fees to civil judgment (2%). Other reported actions include aiding with job searching (35%), creating a budget or providing a financial planning class (17%), and suggesting that supervisees seek help from family or friends (17%). A small group of respondents (7%) reported taking actions other than those found on the list, and 2% reported taking none of the listed actions in cases of nonpayment.

These responses provide insight into the methods used by officers and their agency in cases of nonpayment, which informs our understanding of how changes outlined in the reform bill are represented in probation and court services. The reported actions taken are in line with what the reform bill prescribes, with a heavy reliance on the use of financial waivers and the assignment of community service. Even filing probation violations, while initially punitive, is likely used by officers as a way to bring supervisees back before the court, where the end results may be waivers and/or community service requirements.

6.2.2. Use of Financial Waivers

Reactions to nonpayment are important considerations, but determining how those reactions come about is essential in understanding the role that officers play in the process. Officers provided information about their use of assessments to determine the ability of supervisees to pay required fees. The responses are compiled in

Table 4. Officers reported regularly conducting assessments with their supervisees. Most respondents reported conducting some type of assessment, with 54% indicating that they conduct formal assessments and 28% conducting informal assessments of some kind. A meaningful portion of the sample, 18% of respondents, reported conducting no assessment at all. Those that reported conducting some type of assessment were then asked to indicate the factors that are considered during the course of these assessments that help officers determine ability to pay. Employment status was almost unanimously considered, with 95% reporting using employment as a deciding factor. The number of children that supervisees had (86%), budget or ability to pay (79%), cost of living/housing (74%), and material possessions owned by supervisees (55%) were all factors reported by most respondents. Less frequently reported considerations were mental health/capacity (43%), employment history (41%), living conditions (27%), and physical well-being/fitness (27%). About one-fifth of the sample reported considering other factors not listed (22%).

The findings from survey items that asked about financial waivers specifically are found in

Figure 3. Most of the sample indicated that they request financial waivers with some regularity with 64%, or nearly two-thirds, reporting requesting waivers some of the time, and another 20% reporting requesting waivers most of the time. Only 8% reported requesting waivers almost never, and 8% indicated that they never request waivers. Of the 111 respondents that reported requesting waivers from the court, 61% said that their waivers were granted most of the time, 37% reported waivers were granted some of the time, and only 2% said that their waivers were almost never granted. There were no respondents that indicated that their waivers were never granted.

The responses to these survey items suggest certain consistencies among the role that officers within the sample play in the processes affected by the reform bill. First, officers appear to have a substantial amount of influence in whether their supervisees receive financial waivers. This is apparent by the amount that reported having their requested waivers granted either most or some of the time. Second, officers frequently conduct assessments to make determinations about supervisees’ ability to pay fees. Furthermore, and third, officers base these assessments on factors that might be pertinent in courts’ assessments of whether required payment might cause hardship to the supervisee or their immediate family, such as employment status and number of children. Therefore, the role that officers play is a significant one because their interactions with supervisees often shape whether situations of nonpayment result in waivers or fine time under the new laws put in place by the reform bill.

6.3. Supplemental Analyses

Analyses were also conducted to ascertain if the above-measured attitudes and behaviors varied by each respondent’s time within the role, since these responses might differ between more senior officers and officers with less experience—especially those hired after the reform bill was passed into law. The results of these analyses revealed no observable differences between the self-reported attitudes, fines and fees collection behaviors, or financial waiver behaviors of these different groups of officers. This suggests that the trends observed in the reported findings were not influenced by years of experience or temporal ordering of hire date relative to the passing of the reform bill.

7. Discussion

Community supervision clients are among the wide range of individuals who experience legally imposed financial obligations. These fines, fees, and restitution payments can have detrimental impacts on justice system clients’ paths to rehabilitation when the amounts rise to levels that are not feasible for some to pay. At times, courts have incarcerated clients for their inability to pay, further exacerbating legal involvement. As states and municipalities gain awareness of the harmful effects of these practices, the push for reform will become increasingly relevant. The current study sought to investigate a recent reform effort in Massachusetts that limited the application of such court actions and to assess the attitudes and practices of probation officers within the affected jurisdiction. In doing so, the study provides insight into Massachusetts fines and fees practices in the era of criminal justice reform.

A major takeaway from the study is the important role probation officers play in implementing policies and practices in line with the reform bill. Specifically, they report conducting assessments with their supervisees to determine their ability to pay fees, and they make recommendations that financial waivers be applied with regularity. These waivers are granted fairly often, indicating that the assessments being done are consistent with the reform bill’s provision that the courts have for determining whether requiring payment would create hardship for supervisees or their dependents. Furthermore, this relationship between probation officer recommendations and court decisions may point to a reliance by the court on probation officers to identify cases that would be eligible for financial waivers, although further research investigating the decision making of court personnel in these cases would be necessary before drawing such a conclusion. Officers also demonstrate congruence between their reported behaviors when dealing with clients and the associated attitudes that may drive this behavior.

Another conclusion is that officers do not support the most punitive of responses to nonpayment of fines and fees. Instead, they prefer to utilize waivers or find alternative ways of handling cases that will not exacerbate their supervisees’ legal involvement. The scope of the current study does not allow for a temporal assessment of whether these attitudes were brought by the passing of the reform bill, but it can be said that officers agree with the abolition of the wanton use of fine time in cases of nonpayment. Officers also report imposing community service for supervisees unable to resolve financial obligations on time, further providing evidence that their tendencies and actions align with the policy changes made by the reform bill. This, along with the first conclusion found in the results, suggests that probation officers, court personnel, and the legislation guiding each appear to be operating in sync. In short, the reform bill’s goal to relax legal expectations of financial sanctions seems to be reflected in practice, although we cannot definitively attribute this to the policy change absent of survey data from officers before 2018.

The reform bill has the potential to institute fairer practices within the community supervision and court operations in Massachusetts pertaining to the application, collection, and handling of nonpayment of financial obligations. Indeed, other states that still employ practices similar to fine time or that default to punitive reactions to nonpayment of legal debts may benefit from considering how reforms similar to those made in Massachusetts might create fairer court and correctional systems for their own justice system clients. However, Massachusetts’s reform bill is not infallible; certain implications within the bill’s language may potentially impede the equal application of the new policies. Namely, burdening clients with the responsibility to prove their inability to pay without hardship, using community service as the default substitute for payment, and allowing judges the discretion to accept or reject financial waivers all present opportunity for especially disadvantaged clients to be the most negatively impacted by the new court practices.

While the current study offered important insights into community corrections fines and fees practices amid criminal justice policy reform, it has limitations that should be considered. The degree to which officers’ self-reported attitudes and behaviors regarding fines and fees comport with actual practice is unknown and requires further investigation. An avenue for future research is to empirically assess the effects of the reform bill as they are actually carried out. This is especially important in measuring case outcomes affected by the reform bill (e.g., cases that are granted financial waivers or cases in which waivers were rejected and fine time was ordered), especially those related to clients’ race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status. Future research investigating these outcomes is needed to ascertain if the way the new laws are being applied in court represent an actual change in procedural operations or if the intended changes are negated or at least diminished within the discretionary portions of the process. Another limitation of the current study is its sole reliance on probation officer responses to the survey items. Much more can be learned by surveying court personnel and supervisees. Doing so would garner a more comprehensive understanding of how all stakeholders within community supervision view and interact with new policies affecting fines, fees, and restitution requirements in Massachusetts. The study data also had temporal limitations. Without having pre-reform responses to the same survey measures, it was impossible to determine if probation officer attitudes, perceptions, and actions have changed as a result of the reform. It is possible that officer responses would have been similar prior to the passing of the reform bill. Future research on policy changes in practices affecting legal financial obligations should attempt to obtain measures prior to and following the passing of new policies. A final limitation is the non-random nature of the sample, which may not be representative of all probation officers in Massachusetts. Since participation in the survey was voluntary, certain types of officers may have been more likely to submit responses, such as those with especially strong views of fines and fees policies. Officers with neutral or supportive attitudes toward punitive policies may have been less likely to participate, biasing the results toward less punitive responses.

Limitations notwithstanding, the current study measured Massachusetts probation officer attitudes and practices pertaining to fines and fees following the state’s reprioritization of its responses to legal debts. It was found that probation personnel outlooks align with policy changes such as these, and that they use their influential role in the system to seize new avenues to advocate for their supervisees. In doing so, they reportedly work to obtain financial relief for supervisees who need it most. This presents encouraging evidence in the case for the continued movement of justice system policies toward fairer financial expectations. Policymakers considering justice reforms similar to Massachusetts’s should view the likely support of probation personnel as a crucial component in the successful adoption of legislation in the pursuit of equal treatment of all justice system clients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and S.G.; methodology, M.S. and S.G.; software, M.S.; validation, M.S. and S.G.; formal analysis, M.S.; investigation, M.S and S.G.; resources, M.S. and S.G.; data curation, M.S. and S.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S. and S.G.; visualization, M.S.; supervision, S.G.; project administration, S.G.; funding acquisition, S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Data used in this study were obtained during data collection for the Community Corrections Fines and Fees (CCFF) study, funded by Arnold Ventures.

Data Availability Statement

Access to data used in this research is restricted via terms from the sponsor, Arnold Ventures, and the authors’ institutional review board.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- An Act Reforming Fine Time. S. bill 2050, 190th Commonwealth of Massachusetts General Court. 2017. Available online: https://malegislature.gov/Bills/190/S2050.Html (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- An Act Relative to Criminal Justice Reform. S. bill 2371, 190th Commonwealth of Massachusetts General Court. 2018. Available online: https://malegislature.gov/Bills/190/S2371 (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Beckett, Katherine, and Alexes Harris. 2011. On Cash and Conviction: Monetary Sanctions as Misguided Policy. Criminology and Public Policy 10: 509–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boston Bar Association. 2017. No Time to Wait: Recommendations for a Fair and Effective Criminal Justice System. Boston: Boston Bar Association. [Google Scholar]

- Cutts, Emily. 2016. Report: Probation Costs Fall Disproportionately on the Poorest. Daily Hampshire Gazette. December. Available online: https://www.gazettenet.com/Prison-Policy-Initiative-releases-new-report-on-real-cost-of-probation-6746353 (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Farrington, David P. 1995. The Development of Offending and Antisocial Behavior from Childhood: Key Findings from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 360: 929–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, April D., Michele Cadigan, Frank Edwards, and Alexes Harris. 2019. Monetary Sanctions: A Review of Revenue Generation, Legal Challenges, and Reform. Annual Review of Law and Social Science 15: 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, Lisa. 2020. The Price of Justice: Fines, Fees, and the Criminalization of Poverty in the United States. University of Miami Race and Social Justice Law Review 11: 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hampson, Christopher D. 2017. The New American Debtor’s Prisons. American Journal of Criminal Law 44: 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz, Walter. 2015. Pay or Stay: Incarceration of Minor Criminal Offenders for Nonpayment of Fines and Fees. Tennessee Bar Journal 51: 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Karin D., Bryan L. Sykes, Sarah Shannon, Frank Edwards, and Alexes Harris. 2018. Monetary Sanctions: Legal Financial Obligations in US Systems of Justice. Annual Review of Criminology 1: 471–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massachusetts Court System. 2016. Annual Report on the State of the Massachusetts Court System: FY2016. Boston: Massachusetts Court System. [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Court System. 2017. Annual Report on the State of the Massachusetts Court System: FY2017. Boston: Massachusetts Court System. [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Court System. 2018. Annual Report on the State of the Massachusetts Court System: FY2018. Boston: Massachusetts Court System. [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Court System. 2019. Annual Report on the State of the Massachusetts Court System: FY2019. Boston: Massachusetts Court System. [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Court System. 2020. Annual Report on the State of the Massachusetts Court System: FY2020. Boston: Massachusetts Court System. [Google Scholar]

- Menendez, Matthew, Michael F. Crowley, Lauren-Brooke Eisen, and Noah Atchison. 2019. The Steep Costs of Criminal Justice Fees and Fines: A Fiscal Analysis of Three States and Ten Counties. New York: Brennan Center for Justice, Available online: https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/2020-07/2019_10_Fees%26Fines_Final.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2021).

- Office of State Auditor. 2016. Audit Finds Disparities in Administration of Probation Supervision Fees in Massachusetts Courts [Press Release]. January 13. Available online: https://www.mass.gov/news/audit-finds-disparities-in-administration-of-probation-supervision-fees-in-massachusetts (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Piquero, Alex R., and Wesley. G. Jennings. 2017. Research Note: Justice System-Imposed Financial Penalties Increase the Likelihood of Recidivism in a Sample of Adolescent Offenders. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 15: 325–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappleye, Hannah, and Lisa Riordan Seville. 2014. The Return of the Debtors’ Prison: How a Small Alabama Town Turned Poverty into a Prison Sentence. The Nation 298: 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhland, Ebony. 2021. It’s All About the Money: An Exploration of Probation Fees. Corrections: Policy, Practice and Research 6: 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhland, Ebony, Bryan Holmes, and Amber Petkus. 2020. The Role of Fines and Fees on Probation Outcomes. Criminal Justice and Behavior 47: 1244–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhland, Ebony L., Amber A. Petkus, Nathan W. Link, Jordan M. Hyatt, Bryan Holmes, and Symone Pate. 2021. Monetary Sanctions in Community Corrections: Law, Policy, and their Alignment with Correctional Goals. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 37: 108–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, Wendy. 2016. Punishing Poverty: The High Cost of Probation Fees in Massachusetts. Prison Policy Initiative. Available online: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/probation/ma_report.html (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Senate Committee on Post Audit and Oversight. 2016. Fine Time Massachusetts: Judges, Poor People, and Debtors’ Prison in the 21st Century. Boston: Senate Committee on Post Audit and Oversight. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, Joseph. 2014. As Court Fees Rise, the Poor are Paying the Price. National Public Radio. May. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2014/05/19/312158516/increasing-court-fees-punish-the-poor (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Wade, Christian M. 2016. Low-Level Offenders Struggle to Cover Probation Fees. The Salem News. June. Available online: https://www.salemnews.com/news/state_news/low-level-offenders-struggle-to-cover-probation-fees/article_a877146c-f473-5f3f-b5e6-7dd617d8f611.html (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Western, Bruce, Jeffrey R. Kling, and David F. Weiman. 2001. Labor Market Consequences of Incarceration. Crime & Delinquency 47: 410–27. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Colin. 2018. Major Justice Reform Bill Clears Legislature. CommonWealth. April. Available online: https://commonwealthmagazine.org/criminal-justice/major-justice-reform-bill-clears-legislature/ (accessed on 27 May 2021).

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).