The Employment Ecosystem of Bizkaia as an Emerging Common in the Face of the Impact of COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Emerging Employment Commons in Bizkaia: A Cooperative Ecosystem Linked to a Singular Territory

4. Results

4.1. Priority Groups Based on COVID-19 Impact

On whom to focus actions and who should be prioritized depends on whether we are looking to make a quick impact that allows for rapid recovery, or if we want to help those who are going to have it the hardest and leave the rest to the market’s pace.(CLU_5)

Acting with prudence and contrasted data, referring to groups that have actually lost their jobs. This will require obtaining reliable data from those that have it, the Basque Employment Service—Lanbide.(AP_9)

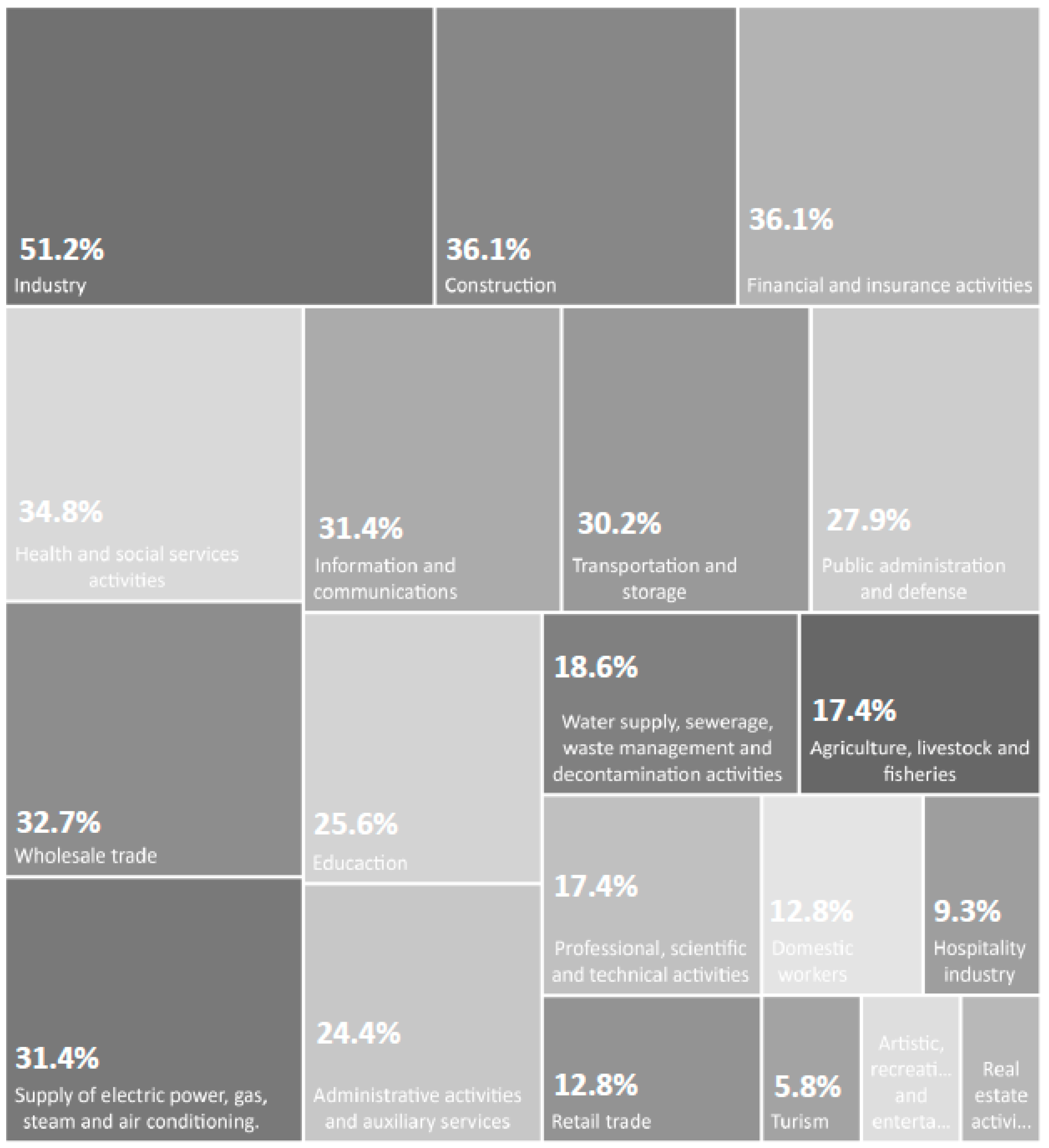

4.2. Sectors of Activity That Are Currently the Most Affected

4.3. Sectors of Activity That Are Expected to Recover First

4.4. Comparison between Sectors Considered to Be the Most Adversely Affected in Terms of Those Expected to Recover First

The most hard-hit, those that are very small limited companies with one or two freelancers or personnel they are responsible for and investments in real estate, materials... As of now there is no aid for these types of companies.(ASE_2)

4.5. Looking for the Common Good: Prioritizing the Most Vulnerable, a Policy Proposal from and to the Ecosystem

- Maintaining employment: on the basis of how close the impact was, Bizkaia’s employment ecosystem deemed it a priority to implement economic measures aimed at sustaining Bizkaia’s workers’ labor conditions. To do this, they proposed a diverse set of mechanisms that could contribute to this goal.They indicated that any economic measure that could enable companies to keep their workers on until normal activity resumed was vital for the survival of the largest possible swath of the ecosystem. Through knowledge drawn closest to the impact withstood, the entities consulted indicated that purchasing power, with particular attention paid to the most vulnerable groups (AP_20), would allow for the reactivation of all other activities in the short term (AP_3). Among other assistance, they proposed implementing specific aid to maintain contracts, support the self-employed, and/or temporarily cover a portion of Social Security contributions, etc.In terms of the impact on activities geared towards the ecosystem’s essential sustainment, also of particular interest are mentions of implementing measures aimed at promoting reconciliation between reproductive and productive work, as well as caretaker and professional activities. In these measures, the gender dimension is fundamental. Also, in the words of the Instituto de la Mujer y para la Igualdad de Oportunidades (2020, p. 6) “the traditional role of caretakers being assigned to women grants them a degree of presence when it comes to responding to the illness, which must be taken into account when addressing the crisis. Ignoring gender’s impact on the social and economic consequences will worsen inequality”. In other words, women are on the front line of the caretaker response. According to the Labor Force Survey (LFS), 66% of healthcare personnel are women. Within the ecosystemic dynamic, underlying care and women’s highly relevant role when it comes to mitigating the pandemic’s impact are noted as a necessary line of future research that directly results from this study.

- Encouraging and stimulating employment: in addition to previously existing ecosystem support, the consulted entities also believed that gradually implementing economic measures aimed at encouraging hiring unemployed individuals and boosting employment was a determining factor (AP_2, CON_1, AP_22): (1) Both those that were found to be in said situation before, and (2) those that fell into this situation due to the impact of the crisis. Both are priority groups. The former to avoid intensifying their prior situation of vulnerability (AP_20) and the latter to attempt to solve their situation before it became chronic (CLU_5). As such, Bizkaia’s employment ecosystem recognized that when faced with an impact like that of COVID-19, opting for a defensive position was not sufficient, and adopting a proactive attitude for its empowerment and future sustainability was also essential.Flexibility and increased aid for hiring through mechanisms like contracting bonuses are considered to be useful mechanics for this objective. In the entities’ own words, this would promote measures that encourage hiring personnel (AP_1, EM_3). Facilitating the hiring of personnel necessary to relaunch affected activities (AP_9). Specifically, taking aim at SMEs and the self-employed through hiring aid, even if work is temporary or part-time (TS_17). Adapting pre-existing programs such as Lanberri to the current circumstances is also considered to be a possibility for evaluation in order to offer targeted responses for hiring individuals from vulnerable groups (TS_9).Likewise, they consider the creation of a transitional subsidized employment space involving all agents as a possible measure (EM_9). They see the proposal to create a common, shared space as a way of advancing towards greater cooperation and tangible relations between the agents that make up the ecosystem: this is one way of moving towards the commoning of Bizkaia’s employment ecosystem through the paradigm used in this article.

- Support before and during employment: the entities consulted once again show their intent to protect the most vulnerable groups in particular. As such, they indicate that the ecosystem on the whole would become more robust if (1) comprehensive employment plans were implemented to provide job training, orientation, and support opportunities (TS_3); and (2) plans were implemented that included telephone and telematic support, orientation, and assistance services so that vulnerable and excluded individuals can return to “normality” along with their personalized inclusion plans (TS_1, EM_6). In both cases, they agree on the importance of defining these plans in agreement and direct, constant contact with all entities that make up the ecosystem (AP_11, TS_12). Facilitating access for individuals in search of work, or improving their current conditions at companies in order to produce “training experience” and “contact” networks (EM_7). Once again, the importance of a territory like Bizkaia having an ecosystem capable of establishing reticular dynamics of mutual recognition and collaboration emerges. This is an approach to the logic of the Employment Commons in which Bizkaia Provincial Council, as the ecosystem’s main public component, could play a convergent, catalyzing role.

- Challenge-oriented employment training: Bizkaia’s employment ecosystem highlights the importance of implementing programs that combine training and subsequent hiring. This would be a conventional proposal if not for its particular focus on the specific orientation that these training programs must include. From the perspective of the Commons, they indicate that training programs being focused on solving the real challenges faced is a determining factor for the ecosystem to be truly capable of better responding to possible future shocks. To do this, they point to the necessity of said programs’ own design having greater interaction with and incorporation of the ecosystem’s real needs (TS_12). It is the opinion of some entities that the continued assessment of the conditions being produced in the ecosystem, and subsequent continued re-design of re-qualification programs, is one of the cornerstones to achieving greater collective resilience (EM_11). In this work, and due to their intricate knowledge of the day-to-day reality experienced by the entities that make up the ecosystem, they highlight the relevant role that local programs aimed at strategic and driving sectors could play (TS_4).Lastly, with training, they also make special mention of the protection and particular support that the most vulnerable segments must receive. As the most fragile link on which the entire ecosystem’s well-being depends, they consider it entirely necessary to (1) guarantee family income so they can address and recuperate their work training plans, and (2) support work-life balance so that women are at the same starting point when it comes to being involved in work training processes (TS_12).

- Other favorable measures for the ecosystem on the whole, and advancement towards creating an Employment Common:In addition to measures specific to the area of employment described above, when it comes to creating a more robust and resilient ecosystem that is attentive to diversity, meaning an Employment Common, the entities point to other complementary measures that would be useful to move forward with in the following areas (Table 2).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. List of Surveyed Entities

| Code | Sector | Entity | Position |

| AP_1 | Public Administration_City Council | Ayuntamiento De Balmaseda | Manager |

| AP_10 | Public Administration_City Council | Urduñederra (Ayto Orduña) | Technitian |

| AP_11 | Public Administration_City Council | Bermeoko Udala | Directorate |

| AP_12 | Public Administration_Develpoment Agency | Forlan, Agencia Desarrollo Local De Muskiz | Manager |

| AP_13 | Public Administration_City Council | Ayto Karrantza | Manager |

| AP_14 | Public Administration_City Council | Ayuntamiento Sestao | Manager |

| AP_15 | Public Administration_City Council | Ayuntamiento De Ermua | Manager |

| AP_16 | Public Administration_Employment Center | Meatzaldeko Behargintza, S.L. | Manager |

| AP_17 | Public Administration_Develpoment Agency | Egaz Txorierri | Directorate |

| AP_18 | Public Administration_City Council | Ayuntamiento De Arrigorriaga | Technitian |

| AP_19 | Public Administration_City Council | Ayuntamiento De Zalla | Manager |

| AP_2 | Publica Administration_Municipal Associtation | Mancomunidad De La Merindad De Durango | Directorate |

| AP_20 | Rural Development Agency | Adr Gorbeialde | Directorate |

| AP_21 | Rural Development Agency | ADR Enkarterrialde | Technitian |

| AP_22 | Rural Development Agency | Urremendi Landa Garapen Elkartea | Manager |

| AP_3 | Public Administration_City Council | Ayuntamiento De Erandio | Technitian |

| AP_4 | Public Administration_City Council | Ayuntamiento De Erandio | Technitian |

| AP_5 | Public Administration_Develpoment Agency | Leartibai Garapen Agentzia | Technitian |

| AP_6 | Public Administration_Employment Center | Behargintza Leioa | Directorate |

| AP_7 | Public Administration_City Council | Ayuntamiento Valle De Trápaga-Trapagaran | Technitian |

| AP_8 | Public Administration_City Council | Ayuntamiento De Ermua | Technitian |

| AP_9 | Public Administration_City Council | Ayuntamiento De Portugalete | Directorate |

| ASE_1 | Association_Business | Nekatur | Directorate |

| ASE_2 | Association_Business | AKTIBA, Asociación De Empresas De Turismo Activo De Euskadi | Directorate |

| ASE_3 | Association_Business | Aed | Technitian |

| ASE_4 | Association_Business | Asle | Technitian |

| ASE_5 | Association_Business | Asociación De Hostelería De Bizkaia | Manager |

| ASE_6 | Association_Business | Gremio De Pasteleria De Bizkaia | Directorate |

| ASE_7 | Association_Business | Asociacion Vizcaina De Excavadores | Manager |

| ASE_8 | Association_Business | Fundación Laboral De La Construcción País Vasco | Manager |

| ASO_1 | Association_Oficial College | Colegio Oficial De Químicos E Ingenieros Químicos | Manager |

| ASO_2 | Association_public private | Enkartur | Manager |

| CF_1 | Learning Center_Vocational Trainning | C.F. Somorrostro | Manager |

| CF_2 | Learning Center_Vocational Trainning | Ikaslan | Manager |

| CF_3 | Learning Center_Vocational Trainning | Centro Formativo Otxarkoaga | Manager |

| CF_4 | Learning Center_Vocational Trainning | Centro San Viator | Manager |

| CF_5 | Learning Center_Vocational Trainning | Hetel | Directorate |

| CLU_1 | Cluster_Business | Asociación Cluster De Energía | Directorate |

| CLU_2 | Cluster_Business | Asociación De Fundidores Del País Vasco Y Navarra | Technitian |

| CLU_3 | Cluster_Business | Gaia | Directorate |

| CLU_4 | Cluster_Business | Aclima | Directorate |

| CLU_5 | Cluster_Business | ACICAE—Cluster Automoción De Euskadi | Directorate |

| CON_1 | Business Confederation | Cebek | Directorate |

| CU_1 | Learning Center_University | Upv/Ehu | Technitian |

| CU_2 | Learning Center_University | Universidad De Deusto | Directorate |

| DS_1 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| DS_2 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| DS_3 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| DS_4 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| DS_5 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| DS_6 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| DS_7 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| DS_8 | Unknown | Unknown | Technitian |

| DS_9 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| EM_1 | Business | HETEL (Hetelenpresa) | Manager |

| EM_10 | Business | Velatia SL | Directorate |

| EM_11 | Business | Petronor | Directorate |

| EM_2 | Business | Fundación Lantegi Batuak | Technitian |

| EM_3 | Business | Talleres Gallarreta Lantegiak, S.L. | Manager |

| EM_4 | Business | Maier S.Coop. | Manager |

| EM_5 | Business | Bidagin, Sl | Directorate |

| EM_6 | Business | Taller Usoa Lantegia.S.A.U | Manager |

| EM_7 | Business | Peñascal Kooperatiba | Manager |

| EM_8 | Business | Galletas Artiach | Manager |

| EM_9 | Business | Petronor Sa | Technitian |

| SD_1 | Trade union | Ccoo Empleo | Manager |

| TS_1 | Social sector | Gaztaroa Sartu Kooperatiba Elkartea | Directorate |

| TS_10 | Social sector | Askabide | Directorate |

| TS_11 | Social sector | Fundacion Ede Fundazioa | Manager |

| TS_12 | Social sector | Asoc. ETORKINEKIN BAT, Por La Inclusión Social Elkartea | Manager |

| TS_13 | Social sector | Asociacion Sortarazi | Manager |

| TS_14 | Social sector | Red Social Koopera | Manager |

| TS_15 | Social sector | Apnabi Empleo Autismo Bizkaia | Directorate |

| TS_16 | Social sector | Cáritas Bizkaia | Unknown |

| TS_17 | Social sector | Fundación Claret Sozial Fondoa | Manager |

| TS_18 | Social sector | Fundación Integrando | Directorate |

| TS_19 | Social sector | Caritas Diocesana De Bilbao | Unknown |

| TS_2 | Social sector | Zabaltzen Sartu Koop Elk | Directorate |

| TS_20 | Social sector | Ftsi | Manager |

| TS_3 | Social sector | Ede Fundazioa | Manager |

| TS_4 | Social sector | Asociacion TENDEL | Directorate |

| TS_5 | Social sector | Nevipen Ijito Elkartea | Directorate |

| TS_6 | Social sector | Elkarbanatuz | Manager |

| TS_7 | Social sector | Asociación Berriztu | Technitian |

| TS_8 | Social sector | Fundación Etorkintza | Manager |

| TS_9 | Social sector | Fundación Gizakia | Manager |

| 1 | Each party surveyed was assigned a code (e.g., TS_18). Whenever a code of this type appears in the text, it indicates the ideas and assertions of a specific entity (the complete list of codes and entities can be consulted in Appendix A). |

References

- Ahedo, Manu. 2006. Business systems and cluster policies in the Basque Country and Catalonia (1990–2004). European Urban and Regional Studies 13: 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Arnaldi, Simone, Francesca Boscolo, and Julia Stamm. 2010. Living the digital revolution—Explorations into the futures of the European Society. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 18: 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atutxa, Ekhi, Imanol Zubero, and Iñigo Calvo-Sotomayor. 2020. Scalability of low carbon energy communities in spain: An empiric approach from the renewed commons paradigm. Energies 13: 5054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atutxa Ordeñana, Ekhi, Imanol Zubero Beascoechea, and Iñigo Calvo-Sotomayor. 2020. El paradigma de lo común y la gestión de la energía en España: Oportunidades para la convergencia entre diferentes. Scripta Nova Revista Electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, Nicolás. 2014. Unas políticas de lo cultural. Kult-ur 1: 101–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beck, Ulrich. 2006. Cosmopolitan Vision. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boas, Taylor, Thad Dunning, and Jennifer Bussell. 2005. Will the digital revolution revolutionize development? Drawing together the debate. Studies in Comparative International Development 40: 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bogdan, Robert, and Sari K. Biklen. 2006. Qualitative Research in Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Bollier, David, and Silke Helfrich, eds. 2014. The Wealth of the Commons: A World beyond Market and State. Amherst: Levellers Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boutiller, Sophie, and Beatriz Castilla-Ramos. 2012. La precarización del mercado de trabajo: Análisis desde Europa y América Latina y el Caribe. Papeles Poblac 18: 239–70. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, Stephen, Charles F. Kennel, and David G. Victor. 2015. Planetary vital signs. Nature Climate Change 5: 969–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, Kath. 2005. Snowball sampling: Using social networks to research non-heterosexual women. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice 8: 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, Alan, and Emma Bell. 2007. Business Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, John, and Leigh Glover. 2002. A common future or towards a future commons: Globalization and sustainable development since UNCED. International Review for Environmental Strategies 3: 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Calle, Ángel, Rubén Suriñach, and Conchi Piñeiro. 2017. Comunes y economías para la sostenibilidad de la vida. In Rebeldías en común: Sobre comunales, nuevos comunes y economías cooperativas. Madrid: Ecologistas en acción. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo-Sotomayor, Iñigo, Ekhi Atutxa, and Ricardo Aguado. 2020. Who is afraid of population aging? Myths, challenges and an open question from the civil economy perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Sotomayor, Iñigo, Jon Paul Laka, and Ricardo Aguado. 2019. Workforce ageing and labour productivity in Europe. Sustainability 11: 5851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carter, Nancy, Denise Bryant-Lukosius, Alba Dicenso, Jennifer Blythe, and Alan J. Neville. 2014. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum 41: 545–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlberg, Lincoln, and Eugenia Siapera. 2007. Radical Democracy and the Internet. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Elola, Aitziber, Jesús M. Valdaliso, Santiago M. López, and Mari Jose Aranguren. 2012. Cluster Life Cycles, Path Dependency and Regional Economic Development: Insights from a Meta-Study on Basque Clusters. European Planning Studies 20: 257–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eustat-Instituto Vasco de Estadística. 2020. Anuario estadístico vasco. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Gobierno Vasco. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, Frank W., and Johan Schot. 2007. Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Research Policy 36: 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, Ian, and Mike Mariathasan. 2014. The Butterfly Defect. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin, Ian, and Robert Muggah. 2020. The Conversation. Available online: https://theconversation.com/the-world-before-this-coronavirus-and-after-cannot-be-the-same-134905 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Guest, Greg, Arwen Bunce, and Laura Johnson. 2006. How Many Interviews Are Enough? An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods 18: 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, David. 2012. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson, Richard. 2018. Digital Revolution. Nature 563: S131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto de la Mujer y para la Igualdad de Oportunidades. 2020. La perspectiva de género, esencial en la respuesta a la COVID-19. Madrid: Ministerio de Igualdad. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Office. 2011. Global Employment Trends 2011. Geneva: ILO. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Naomi. 2001. Reclaiming the Commons. New Left Review 9: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Laclau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe. 2014. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Lucarelli, Stefano, and Carlo Vercellone. 2014. The thesis of cognitive capitalism. New research perspectives. An introduction. Knowledge Cultures 1: 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Max-Neef, Manfred A. 1993. Desarrollo a escala humana: Conceptos, aplicaciones y algunas reflexiones. Barcelona: Icaria. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato, Mariana. 2021. Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism. London: Penguin Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, Walter. 2002. Historias Locales/Diseños Globales. Colonialidad, Conocimientos Subalternos y Pensamiento Fronterizo. Madrid: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, Edgar. 2008. On Complexity. Cresskill: Hampton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, Janice M. 1994. Designing funded qualitative research. In Handbook for Qualitative Research. Edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln. Los Angeles: Sage, pp. 220–35. [Google Scholar]

- OIT Americas. 2020. Tendencias mundiales del empleo juvenil 2020. Ginebra: OIT. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, Elinor. 2015. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 2002. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett, Kate, and Richard Wilkinson. 2010. The Spirit Level: Why Equality Is Better for Everyone. London: Penguin Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Ramonet, Ignacio. 2011. El nuevo ‘sistema-mundo. Valencia: Le Monde diplomatique en español. [Google Scholar]

- Rasul, Imran. 2020. The Economics of Viral Outbreaks. AEA Papers and Proceedings 110: 265–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riechman, Jorge. 2004. Gente que no quiere viajar a marte: Ensayo sobre ecología, ética y autolimitación. Madrid: Catarata. [Google Scholar]

- Ripple, William J., Christopher Wolf, Thomas M. Newsome, Phoebe Barnard, and William R. Moomaw. 2019. World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency to cite this version: World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency. Bioscience 70: 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbauer, P. M. 2008. Triangulation. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. Edited by L. M. Given. Newbury Park: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Katherine F., Michael Goldberg, Samantha Rosenthal, Lynn Carlson, Jane Chen, Cici Chen, and Sohini Ramachandran. 2014. Global rise in human infectious disease outbreaks. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 11: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffen, Will, Johan Rockström, Katherine Richardson, Timothy M. Lenton, Carl Folke, Diana Liverman, Colin P. Summerhayes, Anthony D. Barnosky, Sarah E. Cornell, Michel Crucifix, and et al. 2018. Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115: 8252–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Subirats, Joan. 2011. Otra sociedad, ¿otra política? De “no nos representan” a la democracia de lo común. Barcelona: Icaria. [Google Scholar]

- Taleb, Nassim Nicholas. 2007. The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, Antonio. 2007. Desarrollo endógeno. Teorías y políticas de desarrollo territorial, Investigaciones Regionales. Journal of Regional Research 11: 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco, Roberto. 2000. La descentralización de la política industrial española: 1980–2000. Econ Industries 335: 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Vercellone, Carlo, and Alfonso Giuliani. 2019. Common and commons in the contradictory dynamics between knowledge-based economy and cognitive capitalism. In Cognitive Capitalism, Welfare and Labour: The Commonfare Hypothesis. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef, Peter C., Thijs L. J. Broekhuizen, Yakov Bart, Abhi Bhattacharya, John Qi Dong, Nicolai Fabian, and Michael Haenlein. 2021. Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. Journal of Business Research 122: 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieviorka, Michel. 2020. Sis reflexions sobre la pandèmia. Idees: Revista de temes contemporanis 51: 13. [Google Scholar]

- Wucker, Michele. 2016. The Gray Rhino: How to Recognize and Act on the Obvious Dangers We Ignore. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

| Sub-Groups Including Individuals Found to Be in Precarious Employment Situations Beforehand | Cross-Cutting Conditions That Intensify Vulnerability |

|---|---|

| Individuals with limited term and part-time contracts | Women, particularly domestic workers and caretakers |

| Long-term unemployed individuals in a situation of chronic unemployment | Individuals over the age of 45, as well as those nearing retirement |

| Individuals with limited term and part-time contracts | Younger individuals with little work experience or recent graduates. |

| Individuals with low qualifications | Single-parent families |

| The self-employed and employees of previously weakened micro-SMEs | Migrants |

| Individuals that have recently started new business projects | Dependants |

| Measures

(Compilation Based on the Information Collected from Our Fieldwork) |

|---|

| Creating support teams for emotional and psychological recovery. |

| Promoting spaces of reflection and debate to think about new economic development models.

A tractor project made up of local benchmark spaces for open innovation where organizations, individuals, institutions, and communities can collaborate on the development of innovative product approaches, service provision, business models, and consumption that contributes to a social and circular economy (CLU_4). As an example, they suggest the suitability of a project connected to responsible consumption and food waste recovery that is capable of demonstrating that this transition towards a more sustainable and social economy can be done, that it is efficient, and that it is viable. A project of this type could become a beacon for the appearance of new projects and initiatives (CLU_4). |

| Measures aimed at encouraging employment in sustainable sectors: biodiversity, clean energy, caregiving, etc. |

| Promoting retail and local service and product consumption. |

| Implementing a universal basic income. |

| Ensuring basic needs (housing and food) for the entire population through meal allowances, rent payments, and deferred mortgage payments. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Atutxa, E.; Calvo-Sotomayor, I.; Laespada, T. The Employment Ecosystem of Bizkaia as an Emerging Common in the Face of the Impact of COVID-19. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 407. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10110407

Atutxa E, Calvo-Sotomayor I, Laespada T. The Employment Ecosystem of Bizkaia as an Emerging Common in the Face of the Impact of COVID-19. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(11):407. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10110407

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtutxa, Ekhi, Iñigo Calvo-Sotomayor, and Teresa Laespada. 2021. "The Employment Ecosystem of Bizkaia as an Emerging Common in the Face of the Impact of COVID-19" Social Sciences 10, no. 11: 407. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10110407

APA StyleAtutxa, E., Calvo-Sotomayor, I., & Laespada, T. (2021). The Employment Ecosystem of Bizkaia as an Emerging Common in the Face of the Impact of COVID-19. Social Sciences, 10(11), 407. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10110407