State Fragility, Social Contracts and the Role of Social Protection: Perspectives from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Linking Social Contracts, Different Conditions of State Fragility, and Popular Grievances

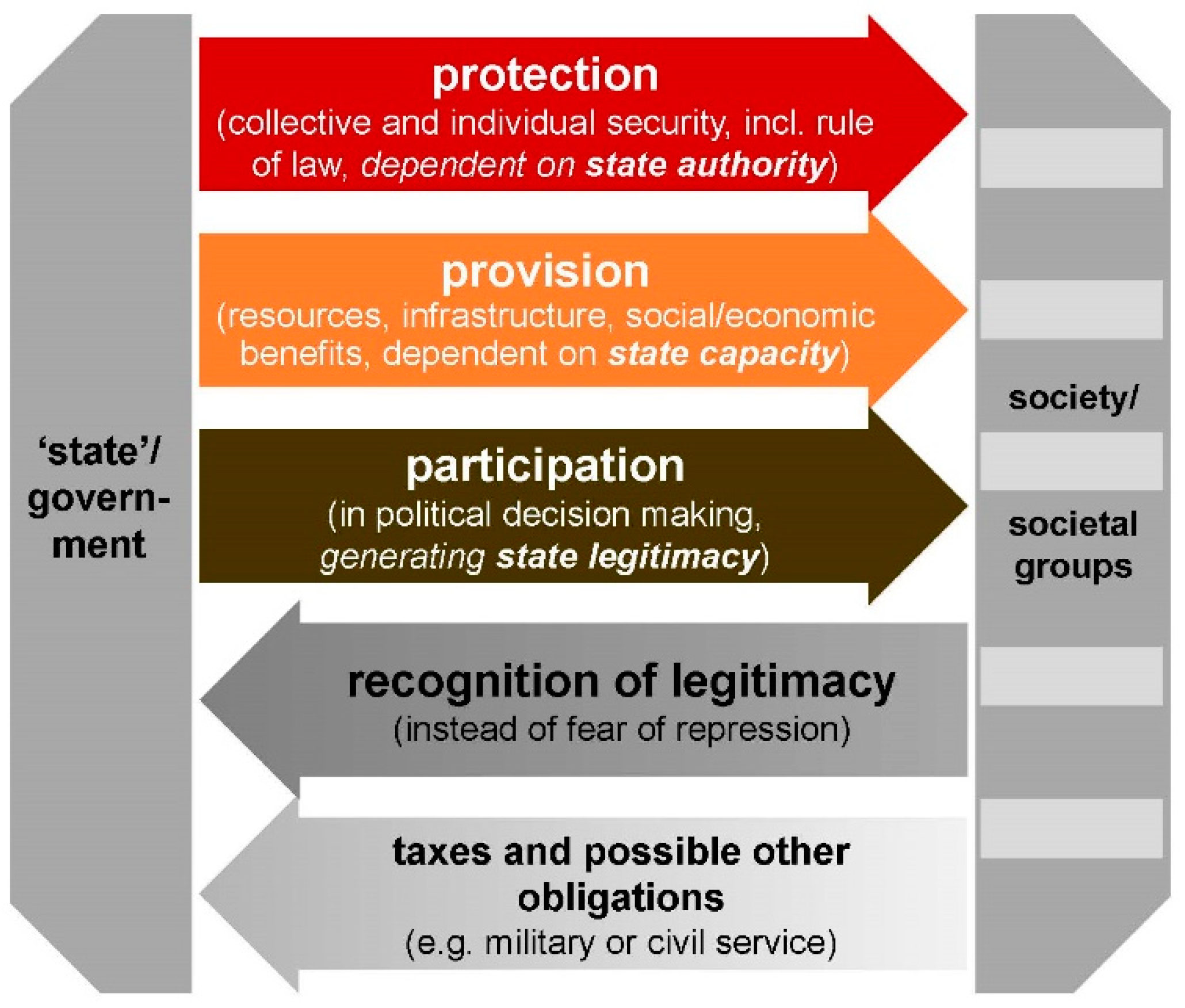

- Protection, including collective security against external threats and individual security against possible damage caused by criminal or politically motivated attacks;

- Provision of social and economic services such as access to land ware and other resources, infrastructure education, health, social protection, a good business climate, government procurement, and others; and

- Participation, that is, granting citizens a voice in political decision-making at different levels.

- accept the ruling authority of the government; and

- pay taxes or fulfil any other obligations (e.g., military service) in accordance with their ability to do so.

- Some governments fail in the delivery of protection (most often with respect to the individual security of citizens) because of a lack of authority (examples include El Salvador and Sri Lanka but no MENA countries);

- Some governments fail in the delivery of provision (e.g., infrastructure, laws to safeguard fair competition on markets or social protection) because of a lack of capacity (examples include Zambia and Burkina Faso but no MENA countries);

- Some governments fail in the delivery of participation (which holds for China but also for most MENA countries, such as Egypt, Morocco, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia); and

- Some governments fail in the delivery of all three Ps. They lack authority, capacity, and legitimacy (examples in MENA are Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Yemen). As a result, the countries suffer from frequent armed conflicts or even civil wars.

3. The Erosion of the Provisionist Social Contracts in the MENA Region after 1985

- Tunisia, commonly regarded as the only successful case of the Arab uprisings, has continued to strengthen the third P, participation—at least until summer 2021—yet reforms in terms of reprioritising the delivery of provision have stagnated so far (El-Haddad 2020; Mahmoud and Súilleabháin 2020). Economic difficulties have marred political achievements to a great degree (Chomiak 2021; Gallien and Werenfels 2019), thus leading to renewed protests.

- Jordan, Morocco, Iran, and the Gulf monarchies seem to be trying to preserve as much as possible of their old social contracts (Kinninmont 2017; Nazer 2005; Luciani 2017; Thompson 2018; Vidican Auktor and Loewe 2021). However, it is not yet clear whether “old” means the original populist–patrimonial social contracts of the 1950s–1970s, the dismantled unsocial social contracts of the 2000s, or a mix of both, such as in Jordan’s “tribal-state compact” (Yom 2020). In any case, protection ranges high on the agenda of these countries, whereas meaningful participation plays no role at all. The question is thus mainly what kind of provision the state is going to deliver in the future and to whom.

- Egypt has moved towards a protectionist contract where provision plays almost as little a role for government legitimisation as participation (Rutherford 2018). President Sisi portrays himself as the saviour of the country and the only alternative to the instability and chaos that countries such as Syria, Libya, and Yemen are witnessing and any other relevant political force, mainly the Muslim Brothers, would bring to Egypt as well. In this dictum, the delivery of protection is enough for a government to legitimise itself with the effect that the well-being of low-income households in Egypt continues to deteriorate (Ibrahim 2020; Sobhy 2021).

- Syria, Yemen, and Libya have descended into civil wars. Their governments have lost control over large parts of the territory with the effect that there is no nation-wide social contract and large parts of the population are not enjoying any of the three Ps anymore. In addition, the relations between the different (regional, religious, ethnic, socioeconomic) parts of society—which are the very important horizontal elements of any social contract—have been poisoned by mistrust and need to be restored in order to rebuild a new social contract (Furness and Trautner 2020). Thus, a new government needs to arbitrate in a fair manner between the former conflicting parties to promote its legitimacy. Social reconstruction will be more important than reconstruction of destroyed physical infrastructure (World Bank 2020).

4. Social Protection as a Cornerstone in Social Contracts

4.1. States Failing on the Delivery of Provision

- Commodity subsidies on energy, food, and water account for a high share of social policy spending in most MENA countries even though they primarily help the rich and not the poor. Many low-income earners cannot afford to purchase large amounts of subsidised commodities, even at the reduced prices (Loewe 2019). They own no cars or central heating (and hence do not buy petrol or heating oil), live in smaller homes than the rich, and have no swimming pools and often no showers (and hence consume less electricity and water). In 2010, MENA countries spent on average 6% of their gross domestic product (GDP) on subsidies, but the effects on poverty and inequality rates were negligible.8 Since then, most MENA countries have reduced subsidies but still spend substantial sums on them (Vidican Auktor and Loewe 2021).

- Direct social assistance schemes suffer from substantial administration costs—accounting for up to 86% of their total budgets (Loewe 2010a)—and from targeting errors as well. Hardly any of those programmes reach out to more than a third of the households belonging to the poorest income quintile of the population, whereas a majority of the beneficiaries (58% in Jordan, 60% in Egypt, 68% in Iraq) are not effectively poor. Therefore, these programmes reduce national poverty head-count rates by just 4% on average and the GINI coefficient by a mere one percentage point (Silva et al. 2012).

- Health costs and benefits are also unequally distributed across income groups. Most MENA governments allocate substantial shares of GDP on health (3% on average) but private households still pay large sums out of pocket—in 2017, on average 34% of all national health care costs.9 Low-income people thus often have difficulties accessing adequate health care.10 Differences in health care utilisation and achievement become obvious when comparing figures for citizens belonging to the lowest and the highest wealth quintile—for instance, under-5 mortality in Egypt (42 versus 19%), babies born in a health care facility in Sudan (9 versus 71%), 2-year-old children vaccinated against measles in Iraq (58 versus 88%), or professional medical attention to children under 5 with acute respiratory infections in Sudan (27 versus 63%) (Loewe forthcoming).

4.2. States Failing on the Delivery of Protection

- The results of a DIE research project conducted in 2015–2016 on cash transfer schemes in five fragile countries (Sierra Leone, Chad, DR Congo, Uganda, and Somalia) confirm that lack of state authority constitutes a challenge for the construction of efficient social protection schemes just as much as lack of state capacity. In Uganda, outbreaks of violence repeatedly challenged the operations of the cash transfer scheme under research, and in Chad, the state had to make additional efforts to safeguard security during the pay-out of benefits (Strupat et al. 2018). In Somalia, cash transfer projects co-operated therefore with local leaders and hawala agents (European Commission 2019).

- At the same time, the project found that social protection schemes have some, if limited, potential to strengthen state authority and thereby contribute to the delivery of protection. In Chad in particular, cash transfers have helped to reduce tensions between different societal groups and thereby have strengthened vertical trust in the government (ibid.).

- The government of Mali concentrated its efforts on building up a national cash transfer scheme in the southern part of the country, where it enjoyed higher authority. International non-governmental organisations (NGOs) therefore decided to set up local cash transfer schemes in the norther pat of the country. Over time, they adjusted the benefits and targeting criteria to those applied by the government in the South, resulting in the emergence of an effectively uniform, nation-wide programme (European Commission 2019).

4.3. States Failing on the Delivery of Participation

- The government of Iran continued to rely on provision but with a more egalitarian touch (see above).

- Morocco embarked a bit on participation. Reinvesting only parts of what it saved with subsidy reform to extend social health insurance coverage and social assistance spending, the government made huge efforts to (i) explain via extensive awareness campaigns why subsidy reform was inevitable, (ii) discuss with a large range of national NGOs how the reform could be shaped to harm the different groups of Moroccan society as little as possible, and (iii) inform the entire publication as early as possible of the results of the consultation process and the steps to be done over the years to come. However, these new ways of participation were not extended to other policy fields.In this and other instances, the main risk to real reform is that participatory opportunities concern only firmly circumscribed, often purely technical fields, or that sophisticated plans elaborated by commissions simply disappear into drawers (e.g., Zintl 2013, p. 202).

- Finally, Egypt has been relying more and more on the delivery of protection as the last and only remaining source of government legitimacy. The government cut down heavily on subsidy spending but used just a bit of what it saved for the extension of direct social transfer spending. It tightened repression much more and has been propagating the argument of being the only government able to effectively defend the individual and collective security of citizens. As warning examples, it points to Syria, Libya, Yemen, and Iraq, where governments lost their authority to armed opposition or rebel groups and no longer were able to provide full protection to the population (Vidican Auktor and Loewe 2021).

4.4. States Failing on the Delivery of All Three Ps

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | We use the term “Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region” in accordance with the widely-used definition by the World Bank, covering Algeria, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Malta, Morocco, Oman, the Palestinian Occupied Territories, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen, as well as—though rather implicitly—West Sahara. Some organisations would also include Mauritania, Somalia, Sudan, and/or Turkey. |

| 2 | Islamic governments are accountable for the provision of social aid to those in need, including non-Muslims. Social justice (cadāla iğtimāciyya) is a central goal of Islamic policy. This does not mean the complete leveling of income and wealth differences (equity of outcome), nor pure equity of opportunity. Islamic governments provide for social protection among others by imposing zakāt (a levy mainly on wealth) or through the awqāf (voluntary religious endowments). For these and other Islamic instruments of social protection, see Jawad and Eseed (2021); Loewe (2010a, pp. 68, 82); Tajmazinani and Mazinani (2021, pp. 28–31). |

| 3 | e.g., for the MENA region, Heydemann (2007); Kinninmont (2017); UNDP—United Nations Development Programme and AFESD—United Nations Development Programme and Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development (2002); Yousef (2004). |

| 4 | Grävingholt et al. (2015, p. 1284) defined state fragility also as “fragile statehood”, as it “is not so much the fragility of the state as such in a legal or even ontological sense as it is the state’s [lacking] ability to fulfil its basic functions.” |

| 5 | Egypt, for example, long had different power poles inside the government: the army, the president, the minister of finance, and the minister of labour. Likewise, society can be quite divided into social classes, ethnic groups, tribes and clans, religious communities, tribal groups, and other interest groups. |

| 6 | For instance, for some years several social contracts have existed in different parts of Syria (Furness and Trautner 2020). |

| 7 | “Guarantee safety of citizens” and “defend country against neighbouring countries” represented protection; “provide education, health and sanitation to all” and “create employment opportunities” represented provision; and “enable citizens to participate in political decisions” and “allow citizens to elect the government” represented participation. |

| 8 | Food subsidies in Egypt, for example, reduced income poverty rates by just a third in 2009, whereas energy subsidies reduced income poverty rates by less than a fifth in 2004, even though both programmes together consumed 8% of GDP at that time (Silva et al. 2012). |

| 9 | In 2017, private household contributions to total national health care spending amounted to 72% in Sudan, 58% in Iraq, 56% in Egypt, 54% in Morocco, and about 30% in Jordan, Bahrain, Lebanon, and Algeria (Loewe forthcoming). |

| 10 | For example, 46 and 45% of the women interviewed in Jordan (2018) and Egypt (2008), respectively, declared that they had difficulties financing urgently needed health care. The shares were even higher in the bottom wealth quintile (64% and 70%, respectively) (cited in Loewe forthcoming). |

| 11 | A comparatively low share of Egyptian respondents admitted to being dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with the al-Sisi government’s 3P delivery. We assume that this is partly due to a bias introduced by respondents’ mistrust and fear of government repression and does not mirror the de facto quality of government services. At the same time, Egyptians seem to be less critical and more loyal to the government in general even if they have no trust in it—something that Loewe and Albrecht (2021) call a “rallying behind the flag”-effect. |

| 12 |

References

- Abouzzohour, Yasmina. 2021. One Year of COVID-19 in the Middle East and North Africa: The Fate of the ‘Best Performers’. Washington: Brookings, Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/03/22/one-year-of-covid-19-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa-the-fate-of-the-best-performers/ (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Adato, Michelle. 2000. The Impact of PROGRESA on Community Social Relationships. Washington: International Food Policy Research Institute, Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/16015/files/mi00ad04.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Adato, Michelle, and Terry Roopnaraine. 2004. Sistema de Evaluación de la Red de Protección Social de Nicaragua: Un análisis social de la “Red de Protección Social” (RPS) en Nicaragua. Washington: International Food Policy Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhayer, Talip. 2021. Fragmentation and Grievances as Fuel for Violent Extremism: The Case of Abu Musa’ab Al-Zarqawi. Social Sciences 10: 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab Barometer. 2021. Survey Data. Princeton, NJ: Available online: https://www.arabbarometer.org/survey-data/ (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Attanasio, Orazio, Luca Pellerano, and Sandra P. Reyes. 2009. Building trust? Conditional cash transfer programmes and social capital. Fiscal Studies 30: 139–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attanasio, Orazio, Sandra Polania-Reyes, and Luca Pellerano. 2015. Building social capital: Conditional cash transfers and cooperation. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 118: 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoob, Mohammed. 1995. The Third World Security Predicament: State Making, Regional Conflict and the International System. Boulder: Lynne Rienner. [Google Scholar]

- Aytaç, Selim. 2014. Distributive Politics in a Multiparty System: The Conditional Cash Transfer Program in Turkey. Comparative Political Studies 47: 1211–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babajanian, Babken. 2012. Social Protection and Its Contribution to Social Cohesion and State-Building. Eschborn: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Available online: https://www.socialcohesion.info/fileadmin/user_upload/Social_Protection_and_its__Contribution_to_Social_Cohesion_GIZ.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Barakat, Zahraa, and Ali Fakih. 2021. Determinants of the Arab Spring Protests in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya: What Have We Learned? Social Sciences 10: 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastagli, Francesca, and Fiona Samuels. forthcoming. Cash transfers for Syrian refugees in Lebanon: Promoting social cohesion? European Journal for Development Research 34.

- Batley, Richard, and Claire Mcloughlin. 2010. Engagement with Non-State Service Providers in Fragile States: Reconciling State-Building and Service Delivery. Development Policy Review 28: 131–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigg, Morgan. 2008. The New Politics of Conflict Resolution: Responding to Difference. Rethinking Peace and Conflict Studies. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, Evie. 2013. State Fragility and Social Cohesion. GSDRC Helpdesk Research Report 1027. Birmingham: Governance and Social Development Resource Centre, University of Birmingham. [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn, Kathleen. 1996. Social spending and political support: The “lessons” of the national solidarity program in Mexico. Comparative Politics 28: 171–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchi, Francesco, Christoph Strupat, and Armin von Schiller. 2020. Social protection and revenue collection: How they can jointly contribute to strengthening social cohesion. International Social Security Review 73: 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoon, Brian. 2006. On Welfare and Terror: Social Welfare Policies and Political-Economic Roots of Terrorism. Journal of Conflict Resolution 50: 176–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, Samuel, Rachel Slater, and Richard Mallett. 2012. Social Protection and Basic Services in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Situations: A Global Review of the Evidence. Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium Working Paper 8. London: Overseas Development Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Cherrier, Cécile. 2021. The humanitarian–development nexus. In Handbook of Social Protection Systems. Edited by Esther Schüring and Markus Loewe. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Chomiak, Laryssa. 2021. Tunisian Democracy 10 Years after the Revolution: A Tale of Two Experiences. DIE Briefing Paper 6/2021. Bonn: German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE). [Google Scholar]

- Christou, William, and Karam Shaar. 2020. 2021 Budget Reveals the Depth of Syria’s Economic Woes. Atlantic Council Blog. Available online: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/2021-budget-reveals-the-depth-of-syrias-economic-woes/ (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- De Regt, Jacomina, Shruti Majumdar, and Janmejay Singh. 2013. Designing Community-Driven Development Operations in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Situations: Lessons from a Stocktaking. Washington: World Bank, Available online: https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/39236-doc-186._designing_community_driven_development_in_fragile_and_conflict_affected_situations.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Devarajan, Shanta, and Lili Mottaghi. 2015. Towards a New Social Contract. Washington: World Bank, Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/202171468299130698/Towards-a-new-social-contract (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Devereux, Stephen, and Rahel Sabates-Wheeler. 2004. Transformative Social Protection. IDS Working Paper 232. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies. [Google Scholar]

- El-Haddad, Amirah. 2020. Redefining the social contract in the wake of the Arab Spring: The experiences of Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia. World Development 127: 104774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hedeny, Amany. 2021. Islamic Dimensions of Egyptian Social Policy Productive Mechanisms or Mobilized Discourses? In Social Policy in the Islamic World. Edited by Ali Akbar Tajmazinani. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 241–61. [Google Scholar]

- ESCWA. 2017. Changes in Public Expenditure on Social Protection in Arab Countries. Beirut: United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3797212/files/E_ESCWA_SDD_2017_TECHNICALPAPER-14.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- EU. 2017. From the Ground Up: The Long Road to Social Protection in Somalia. Brussels: European Union, Available online: https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/articles/ground-long-road-social-protection-somalia (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- European Commission. 2019. Social Protection across the Humanitarian–Development Nexus: A Game Changer in Supporting People through Crises. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, David, Brian Holtemeyer, and Katrina Kosec. 2019. Cash transfers increase trust in local government. World Development 114: 138–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. 2014. The Economic Impacts of Cash Transfer Programmes in Sub-Saharan Africa. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Furness, Mark, and Bernhard Trautner. 2020. Reconstituting social contracts in conflict-affected MENA countries: Whither Iraq and Libya? World Development 135: 105085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallien, Max, and Isabelle Werenfels. 2019. Is Tunisia Really Democratising? Progress, Resistance, and an Uncertain Outlook. SWP Comment No. 13. Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, Available online: https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/comments/2019C13_gallien-wrf.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Garrote Sanchez, Daniel. 2018. Combating Corruption, a Necessary Step toward Improving Infrastructure. LCPS (Lebanese Center for Policy Studies) Policy Brief Number 32. Lebanon: Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, Available online: https://lcps-lebanon.org/publications/1540907457-policy_brief_32.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Gehrke, Esther, and Renate Hartwig. 2018. Productive effects of public works programs: What do we know? What should we know? World Development 107: 111–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grävingholt, Jörn, Sebastian Ziaja, and Merle Kreibaum. 2015. Disaggregating state fragility: A method to establish a multidimensional empirical typology. Third World Quarterly 36: 1281–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grotius, Hugo. 1625. De jure belli ac pacis (On the Law of War and Peace). Paris: Nicolaum Byon. [Google Scholar]

- Guhan, Sanjivi. 1994. Social security options for developing countries. International Labour Review 133: 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Gang. 2009. China’s local political budget cycles. American Journal of Political Science 53: 621–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, Yuval. 2011. Sapiens: A Brief History of Mankind. New York: Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Heydemann, Steven. 2007. Social pacts and the persistence of authoritarianism the Middle East. In Debating Arab Authoritarianism: Dynamics and Durability in Non-Democratic Regimes. Edited by Oliver Schlumberger. Stanford: University Press, pp. 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch, Raymond. 2020. The rise and decline of the populist social contract in the Arab world. World Development 129: 104661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, Albert. 1970. Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbes, Thomas. 1985. Leviathan. London: Penguin Books. First published 1651. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, Solava. 2020. The Dynamics of the Egyptian Social Contract: How the Political Changes affected the Poor. World Development 138: 105254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, Iffat. 2016. Conflict-Sensitive Cash Transfers. K4D Helpdesk Report 201. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies. [Google Scholar]

- IMF. 2014. Islamic Republic of Iran. Country Report 14/94. Washington: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Jawad, Rana, and Rana Eseed. 2021. Social Policy and the Islamic World in Comparative Perspective: Taking Stock, Moving Forward. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kinninmont, Jane. 2017. Vision 2030 and Saudi Arabia’s Social Contract: Austerity and Transformation. Research Paper. London: Chatham House, The Royal Institute of International Affairs, Available online: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2017-07-20-vision-2030-saudi-kinninmont.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Kivimäki, Timo. 2021. The Fragility-Grievances-Conflict Triangle in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA): An Exploration of the Correlative Associations. Social Sciences 10: 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, Gabriele. 2021. Effects of social protection interventions on social inclusion, social cohesion and nation building. In Handbook of Social Protection Systems. Edited by Esther Schüring and Markus Loewe. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 636–46. Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/downloadpdf/edcoll/9781839109102/9781839109102.00079.xml (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Krafft, Caroline, Ragui Assaad, and Mohamed Ali Marouani. 2021. The Impact of COVID-19 on Middle Eastern and North African Labor Markets: Glimmers of Progress but Persistent Problems for Vulnerable Workers a Year into the Pandemic. ERF Policy Brief No. 57. Cairo: Economic Research Forum (ERF). [Google Scholar]

- Krieg, Andreas. 2017. Socio-Political Order and Security in the Arab World: From Regime Security to Public Security. Cham: Palgrave McMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Larbi, Hedi. 2016. Rewriting the Arab Social Contract: Toward Inclusive Development and Politics in the Arab World. Cambridge: Harvard Kennedy School, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Simon, and Kay Sharp. 2015. Topic Guide: Anticipating and Responding to Shocks: Livelihoods and Humanitarian Responses; London: Overseas Development Institute. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08978e5274a27b20000bf/EoD_Topic_Guide_Shock_Nov_2015.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Locke, John. 2003. Two Treatises of Government. New Haven: Yale University Press. First published 1689. [Google Scholar]

- Loewe, Markus. 2010a. Soziale Sicherung in den arabischen Ländern: Determinanten, Defizite und Strategien für den informellen Sektor. Baden-Baden: Nomos. [Google Scholar]

- Loewe, Markus. 2010b. Die Diskrepanz zwischen wirtschaftlicher und menschlicher Entwicklung in der arabischen Welt. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 24: 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Loewe, Markus. 2019. Social protection schemes in the Middle East and North Africa: Not fair, not efficient, not effective. In Social Policy in the Middle East and North Africa: The New Social Protection Paradigm and Universal Coverage. Edited by Rana Jawad, Nicola Jones and Mahmood Messkoub. Cheltenham: Elgar, pp. 35–60. [Google Scholar]

- Loewe, Markus, and Holger Albrecht. 2021. The Social Contract in the Middle East and North Africa: What Do the People Want? Paper Presented at the Virtual 55th Annual Meeting of the Middle East Studies Association, Tucson, AZ, USA, November 29–December 3. [Google Scholar]

- Loewe, Markus, and Rana Jawad. 2018. Introducing social protection in the Middle East and North Africa: Prospects for a new social contract? International Social Security Review 71: 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewe, Markus, and Esther Schüring. 2021. Introduction to the Handbook of Social Protection Systems. In Handbook of Social Protection Systems. Edited by Esther Schüring and Markus Loewe. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Loewe, Markus, and Lars Westemeier. 2018. Social insurance reforms in Egypt: Needed, belated, flopped. In POMEPS Studies 31, Social Policy in the Middle East and North. Edited by POMEPS (Project on Middle East Political Science Africa). Washington: Elliott School of International Affairs, pp. 63–69. Available online: https://pomeps.org/social-insurance-reforms-in-egypt-needed-belated-flopped (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Loewe, Markus, Bernhard Trautner, and Tina Zintl. 2019. The Social Contract: An Analytical Tool for Countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) and Beyond. Briefing Paper 17/2019. Bonn: German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE). [Google Scholar]

- Loewe, Markus, Tina Zintl, Jörn Fritzenkötter, Verena Gantner, Regina Kaltenbach, and Lena Pohl. 2020. Community Effects of Cash-for-Work Programmes in Jordan: Supporting Social Cohesion, More Equitable Gender Roles and Local Economic Development in Contexts of Flight and Migration. DIE Study 103. Bonn: German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE). [Google Scholar]

- Loewe, Markus, Tina Zintl, and Annabelle Houdret. 2021. The social contract as a tool of analysis. Introductory chapter to a special issue ‘In quest of a new social contract: How to reconcile stability and development in the Middle East and North Africa?’. World Development 145: 104982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewe, Markus. forthcoming. Social protection for better health in the Middle East and North Africa. In Oxford Handbook of Social Protection in the Global South. Edited by A. Ben Brik. Oxford: University Press, Submitted for publication.

- Luciani, Giacomo. 2016. On the economic causes of the Arab Spring and its possible developments. In Oil States in the New Middle East: Uprisings and Stability. Edited by Kjetil Selvik and Bjørn Olav Utvik. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 188–204. [Google Scholar]

- Luciani, Giacomo. 2017. Introduction: In search of economic policies to stabilise democratic transitions. In Combining Economic and Political Development: The Experience of MENA. International Development Policy Series 7. Geneva: Graduate Institute Publications, Boston: Brill-Nijhoff, Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/poldev/2262 (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Machado, Anna C., Charlotte Bio, Fábio Veras Soares, and Rafael Guerreiro Osorio. 2018. Overview of Non-Contributory Social Protection Programmes in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region through a Child and Equity Lens. Brazil: International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, Youssef, and Andrea Ó Súilleabháin. 2020. Improvising Peace: Towards New Social Contracts in Tunisia. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 14: 101–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallet, Richard, and Rachel Slater. 2013. Funds for Peace? Examining the Transformative Potential of Social Funds. Stability: International Journal of Security & Development 2: 49. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, Abraham H. 1943. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review 50: 370–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matzke, Torsten. 2012. Das Ende des Post-Populismus: Soziale und ökonomische Entwicklungstrends im “Arabischen Frühling”. Bürger im Staat 62: 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- McCandless, Erin. forthcoming. The Social Contract—Social Cohesion Relationship: Emerging Evidence from Tunisia, Yemen, Zimbabwe and South Africa. Bonn: German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), mimeo.

- MMoH. 2018. La Couverture Médicale de Base au Maroc: Bilan D’étapes et Perspectives; Rabat: Moroccan Ministry of Health. Available online: https://www.sante.gov.ma/Documents/2018/04/presentation%20JMS%202018.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Moghadam, Valentine. 2013. What is democracy? Promises and perils of the Arab Spring. Current Sociology 61: 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molyneux, Maxine, Nicola Jones, and Fiona Samuels. 2016. Can cash transfer programmes have “transformative” effects? Journal of Development Studies 52: 1087–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mostafavi-Dehzooei, Mohammad, Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, and Masoumeh Heshmatpour. 2020. Cash transfers, food consumption, and nutrition of the poor in Iran. Paper Presented at the 26th Annual Conference of the Economic Research Forum, Cairo, Egypt, June 23–September 30. [Google Scholar]

- Muggah, Robert, Timothy Sisk, Eugenia Piza-Lopez, Jago Salmon, and Patrick Keuleers. 2012. Governance for Peace: Securing the Social Contract. New York: United Nations Development Programme. [Google Scholar]

- Nazer, Fahad. 2005. Time for a Saudi ‘‘New Deal”. Yale Global Online. Available online: https://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/time-saudi-new-deal (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- OECD—Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2009. Concepts and dilemmas of state-building in fragile situations: From fragility to resilience. OECD Journal on Development 9: 61–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogharanduku, Victor. 2017. Violent Extremism and Grievance in Sub-Saharan Africa. Peace Review 29: 207–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovadiya, Mirey, Adea Kryeziu, Syeda Masood, and Eric Zapatero. 2015. Social Protection in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Countries: Trends and Challenges. Washington: World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Pavanello, Sara, Carol Watson, W. Onyango-Ouma, and Paul Bukuluki. 2016. Effects of Cash Transfers on Community Interactions: Emerging Evidence. Journal of Development Studies 52: 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raavad, Annie Julia. 2013. Social Welfare Policy: A Panacea for Peace? A Political Economy Analysis of the Role of Social Welfare Policy in Nepal’s Conflict and Peace-Building Process. London: London School of Economics and Political Science, Available online: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/159534/WP137.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Razzaz, Omar. 2013. The Treacherous Path towards a New Arab Social Contract. Beirut: Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs, American University of Beirut, Available online: https://www.aub.edu.lb/ifi/Documents/public_policy/other/20131110_omar_razzaz_paper.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Reeg, Caroline. 2017. Public Works Programmes in Crisis and Post-Conflict States. Lessons Learned in Sierra Leone and Yemen. Bonn: German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), mimeo. [Google Scholar]

- Revkin, Mara Redlich, and Ariel Ahram. 2020. Perspectives on the rebel social contract: Exit, voice, and loyalty in the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. World Development 132: 104981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 1762. Du Contrat Social ou Principes du Droit Politique. Amsterdam. Available online: http://classiques.uqac.ca/classiques/Rousseau_jj/contrat_social/Contrat_social.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Rutherford, Bruce. 2018. Egypt’s new authoritarianism under al-Sisi. The Middle East Journal 72: 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidin, Mohd Irwan Syazli. 2018. Rethinking the ‘Arab Spring’: The Root Causes of the Tunisian Jasmine Revolution and Egyptian January 25 Revolution. International Journal of Islamic Thought 13: 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi-Isfahani, Djavad, Bryce Wilson Stucki, and Joshua Deutschmann. 2015. The reform of energy subsidies in Iran: The role of cash transfers. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 51: 1144–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafik, Minouche. 2021. What We Owe Each Other. Princeton: University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Joana, Victoria Levin, and Matteo Morgandi. 2012. The Way Forward for Social Safety Nets in the Middle East and North Africa. MENA Development Report 73835. Washington: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Sobhy, Hania. 2021. The Lived Social Contract in Schools: From protection to the production of hegemony. World Development 137: 104986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strupat, Christoph, Daniel Nowack, and Julia Leininger. 2018. Cash Transfers in Fragile States. Bonn: German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Mimeo. [Google Scholar]

- Tajmazinani, Ali Akbar, and Zahra Mahdavi Mazinani. 2021. Foundations of social policy and welfare in Islam. In Social Policy in the Islamic World. Edited by Ali Akbar Tajmazinani. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Taydas, Zeynep, and Dursun Peksen. 2012. Can States buy peace? Social welfare spending and civil conflicts. Journal of Peace Research 49: 273–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, Mark. 2018. The Saudi ‘‘social contract’ under strain: Employment and housing. POMEPS Studies 31: 75–80. Available online: https://pomeps.org/the-saudi-social-contract-under-strain-employment-and-housing (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- UNDP—United Nations Development Programme, and AFESD—Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development, eds. 2002. Creating Opportunities for Future Generations. Arab Human Development Report 2002. New York: United Nations Development Programme. [Google Scholar]

- UN-ESCWA, and University of St. Andrews. 2020. Syria at War: Eight Years On; Beirut: United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/syria-war-eight-years (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Valli, Elsa, Amber Peterman, and Melissa Hidrobo. 2019. Economic Transfers and Social Cohesion in a Refugee-Hosting Setting. The Journal of Development Studies 55: 128–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Ginneken, Wouter. 2005. Managing Risk and Minimising Vulnerability: The Role of Social Protection in Pro-Poor Growth. A Paper Produced for the DAC-POVNET Task Team on Risk, Vulnerability and Pro-poor Growth. Geneva: International Labour Organization, Available online: http://www.oit.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---soc_sec/documents/publication/wcms_secsoc_1510.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Vidican Auktor, Georgeta, and Markus Loewe. 2021. Subsidy Reforms in the Middle East and North Africa: Strategic Options and Their Consequences for the Social Contract. German Development Institute. Available online: https://www.die-gdi.de/discussion-paper/article/subsidy-reforms-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa-strategic-options-and-their-consequences-for-the-social-contract/ (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Winckler, Onn. 2013. The “Arab Spring”: Socioeconomic Aspects. Washington: Middle East Policy Council, vol. 20, Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/mepo.12047 (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- World Bank. 2004. Unlocking the Employment Potential in the Middle East and North Africa: Toward a New Social Contract. Washington: World Bank, Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/343121468753030506/pdf/288150PAPER0Unlocking0employment.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- World Bank. 2016. West Bank and Gaza: Public Expenditure Review of the Palestinian Authority. Towards Enhanced Public Finance Management and Improved Fiscal Sustainability. Washington: World Bank, Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/320891473688227759/pdf/ACS18454-REVISED-FINAL-PER-SEPTEMBER-2016-FOR-PUBLIC-DISCLOSURE-PDF.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- World Bank. 2020. Building for Peace: Reconstruction for Security, Sustainable Peace, and Equity in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Yom, Sean. 2020. Bread, Fear and Coalition Politics in Jordan. In Economic Shocks and Authoritarian Stability: Duration, Financial Control, and Institutions. Edited by Victor C. Shih. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 210–35. [Google Scholar]

- Younis, Nour, Mira Rahm, Fadi Bitar, and Mariam Arabi. 2021. COVID-19 in the MENA Region: Facts and Findings. The Journal Infection in Developing Countries 15: 342–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, Tarik M. 2004. Development, growth and policy: Reform in the Middle East and North Africa since 1950. Journal of Economic Perspectives 18: 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zepeda, Eduardo, and Diana Alarcón. 2010. Employment guarantee and conditional cash transfers programs for poverty reduction. Paper presented at the UNDP’s Ten Years of War against Poverty Conference, Manchester, UK, September 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zintl, Tina. 2013. Syria’s Authoritarian Upgrading, 2000–2010: Bashar al-Asad’s Promotion of Foreign-Educated Returnees as Transnational Agents of Change. Ph.D. thesis, University of St Andrews, St Andrews, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Zintl, Tina, and Markus Loewe. forthcoming. More than the sum of its parts: Donor-sponsored Cash-for-Work Programmes and social cohesion in Jordanian communities hosting Syrian refugees. European Journal for Development Research 34.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loewe, M.; Zintl, T. State Fragility, Social Contracts and the Role of Social Protection: Perspectives from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120447

Loewe M, Zintl T. State Fragility, Social Contracts and the Role of Social Protection: Perspectives from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(12):447. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120447

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoewe, Markus, and Tina Zintl. 2021. "State Fragility, Social Contracts and the Role of Social Protection: Perspectives from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region" Social Sciences 10, no. 12: 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120447

APA StyleLoewe, M., & Zintl, T. (2021). State Fragility, Social Contracts and the Role of Social Protection: Perspectives from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region. Social Sciences, 10(12), 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120447