1. Introduction

Almost 70 years after the passage of the 1951 Refugee Convention and Hannah Arendt’s appeal for ‘the right to have rights’, humanitarian space for refugees/asylum seekers has dramatically narrowed in the global north as policies of preclusion, prevention, and externalization become standard practice in managing migration (

Arendt 1958;

Hyndman and Giles 2016). The principle of non-refoulement, the legal agreement that prohibits a signatory state from forcibly repatriating a refugee, is the conceptual pillar of international refugee law, to which the United States and 145 other countries are signatories. The United States has only recently followed its European Union and Australian counterparts in using a comprehensive strategy of administrative and legal measures to keep asylum seekers outside of its territory and target those who arrive with increased detention and rapid return to transit countries or regions of origin. Beginning with the Obama administration and intensifying under President Trump, the United States began pursuing bilateral agreements with source and transit countries to facilitate the interception and repatriation of potential asylum seekers. The Trump administration adopted mechanisms used by other countries in the global north to legally and physically exclude asylum seekers from the US in what several scholars refer to as spaces and policies of refugee exclusion (

Mountz 2011,

2020;

Hyndman and Giles 2011,

2016). Though President Trump’s public rhetoric focused on the construction of a border wall, subsequential executive orders targeted asylum seekers through increased jailing, prolonged detention, and the increased use of expedited deportation procedures (

National Immigrant Justice Center 2020).

In this paper, we draw on policy analysis, interviews, and participant observation to argue that three policies have redefined the US asylum system from one based on detention and deportation to expulsion and exclusion. These include the disingenuously named Migrant Protection Protocol (MPP) a.k.a. ‘Remain in Mexico’ policy; third-country agreements; and closing the border to asylum seekers under Title 42 during the COVID-19 pandemic. The ‘Remain in Mexico’ policy required that asylum seekers wait for their court hearing in Mexico after quickly being processed into the US’ immigration database. This resulted in a makeshift camp of asylum seekers on a plaza adjacent to the international bridge in Matamoros, Mexico that grew from several hundred people to a peak of 2500–3000 in January 2020. While the MPP camp formally exists on Mexican territory, it was created by the United States’ policies and is temporally bound by its asylum processing system. The MPP camp is not an extraterritorial zone of sovereignty abroad but is a precarious settlement that exists in a ‘space of exclusion’ (

Maillet et al. 2018).

A series of third-country agreements constitute another key shift to a US asylum policy defined by exclusion and expulsion of asylum seekers from US territory. While implementing the MPP policy (January 2018–March 2020), the United States pressured Central American countries to sign bilateral agreements that return asylum seekers to signatory countries in the region where they would be required to apply for asylum, blocking their access to asylum in the US. Asylum Cooperative Agreements (ACAs) relocate asylum seekers to places with similar security threats and human rights abuses as their countries of origin. COVID-19 provided the Trump administration a pretext to cement the US’ transition to an asylum system built on policies of expulsion and exclusion. On 20 March 2020, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) used an obscure health code to indefinitely suspend the processing of asylum claims in the name of protecting global health.

We then narrow in on the scale of MPP asylum seekers in Matamoros, Mexico to understand the spaces of waiting produced by these policies of exclusion, and how the ‘Remain in Mexico’ (MPP) and Title 42 (coronavirus exclusion) policies intersect to impact the asylum seekers’ camp and its residents. Our research reveals that COVID-19 and the related closing of the border to asylum seekers have shaped the MPP camp and its residents in unexpected ways. In-depth interviews with humanitarian and legal camp service providers reveal that COVID-19’s primary impacts on asylum seekers are not health impacts of the virus itself. Rather, we show how the US administration weaponized the pandemic to further dismantle the asylum process, leading to prolonged im/mobility that played out locally in the asylum seekers’ struggle to remain visible. We explore spatial practices of exclusion and im/mobility that produce the MPP camp in Matamoros as a way to understand how legal regimes of exclusion work, the spaces they produce, and how victims of this legal violence use im/mobility as acts of resiliency and contestation.

3. Methodology

This paper is the project of a collective research and writing project at Texas State University called the Latin American Mobility Project (LAMP). The first two authors are faculty members who supervise the LAMP lab, which comprises nine graduate students and three undergraduate students, all of whom contributed to this article’s data analysis and writing. From August 2020 to October 2020, the first two authors conducted semi-structured interviews via Zoom with 18 key informants who provide humanitarian, medical, legal, and religious services to the residents of the Matamoros camp. The 18 service providers are adult American citizens, 15 women and three men, most of whom live or work on the US–Mexico border. Twelve of the 18 interviewees are humanitarian service providers, four are lawyers, one is a nurse, and one is a nun. We used snowball sampling (

Stratford and Bradshaw 2016) to identify research participants based on the first author’s service-learning experiences. The experiences, survival strategies, and governance models of asylum seekers are the focus of a separate article; here we emphasize the experiences of service providers who powerfully link the evolution of the camp and its socioenvironmental dynamics with the changing political economic landscape of asylum in the United States during the pandemic. As such, the MPP asylum seekers’ camp in Matamoros is the unit of analysis of this paper, not individual asylum seekers or their households.

These interviews build on the two first authors’ extensive ethnographic research in refugee and migrant communities and in their sending countries. The first author has organized three student service-learning opportunities that resulted in opportunities for participant observation prior to interview-based research. Interviews lasted from one hour to an hour and a half via Zoom, and interviews were recorded and transcribed by LAMP lab members. We used semi-structured coding methods (

Cope 2016) to identify themes related to how policy changes to asylum law during the Trump administration affected asylum seekers at the Mexican border. We use pseudonyms for all interviewees to protect their privacy.

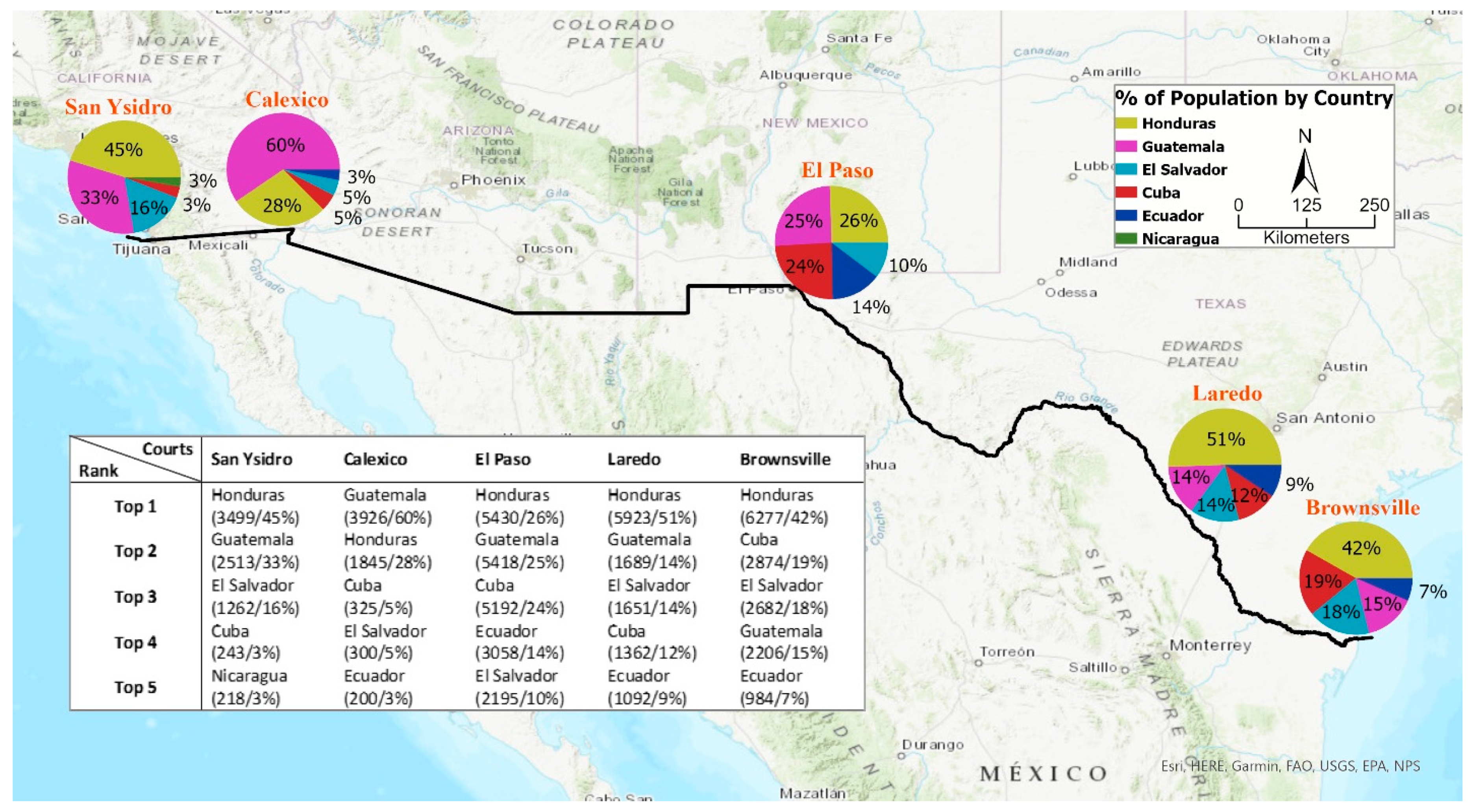

In addition to interviews, we analyze the TRAC Immigration database managed by Syracuse University, using descriptive statistics and ArcGIS to provide a quantitative overview of the MPP program and its geographies prior to narrowing in on the Matamoros asylum seeker camp (

Syracuse University 2020). Our lab also analyzed the accounts of organizations providing services to the camp on social media platforms to construct a chronology of COVID-19’s impacts on the camp. Lab members analyzed media content and constructed a timeline outline which we used to triangulate with interview data to understand the camp’s establishment and evolution.

5. Im/Mobility during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Matamoros Asylum Seeker’s Camp

Obscure health regulations were used to implement a final coup de grâce that has left tens of thousands of refugees stranded in extreme precarity in Mexico’s violent northern border cities. In this section, we focus on the spaces and im/mobilities these logics and policies of exclusion produce. The tactics of exclusion, intensified and cemented by Title 42, manifested in prolonging migrants’ asylum journey by creating additional spaces of im/mobility and waiting, negatively affecting their personal security and intensifying their struggle for visibility.

5.1. The Establishment of the MPP Camp

Near the international bridge that connects Brownsville, Texas and Matamoros, Mexico, asylum seekers formed a makeshift camp on the Mexican side of the border as they waited for entry to the US where they would be processed and eventually have their asylum cases heard in the immigration court tents on the other side of the Rio Grande (

Figure 3). When MPP began implementation in the Rio Grande Valley in July 2019, the relatively small groups of asylum seekers who had waited in the ‘metering’ process soon grew to hundreds and eventually thousands of migrants waiting for their turn to cross the bridge that serves as a port of entry to the United States. In the void created by policies of exclusion and neglect emerged an impressive humanitarian effort. The director of the Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley, Sister Ester, described the humanitarian response:

Initially, when the families were returned back to wait in Mexico, they stayed right there at the border… they just slept on the ground, a lot of people. People and groups from the United States started to see that this was happening, started to respond and take them tents, and water, and food. But it was a very disorganized response, because it was just out of the generosity here of different groups that started to form…

Chaos in Matamoros resulted from the sudden arrival of a population of thousands of migrants in situations of extreme precarity in a city already overwhelmed with its own ongoing issues of violent crime and poverty. The informality of the camp and the lack of a governmental response to the humanitarian crisis resulted in unsanitary conditions and increased crime and cartel activity in and around the plaza, the blocking of the main entrance into Matamoros, and international stigma that many Matamoros residents resented. In this US-manufactured space of exclusion (

Maillet et al. 2018), the Mexican National Institute of Immigration (INM) resisted non-profit and grassroots attempts to create more durable and permanent infrastructure for camp residents, such as sanitation, housing or Wi-Fi.

The Mexican authorities proposed several options of moving the camp or its residents elsewhere rather than formalizing the camp’s infrastructure or legal refugee recognition. To clear out the plaza, Mexican authorities offered to relocate residents to shelters away from the border, or alternatively across the levee near the bridge (

Figure 3).

In an act of resilience, the MPP migrants exploited their immobility, refusing to move. The MPP asylum seekers were wary of moving away from the bridge for many reasons. They had created a community in the plaza over several months that provided a sense of autonomy and protection in this open space. According to Sister Ester, “They developed a sense of community among themselves, a way of protecting themselves and helping each other out.” Moreover, they preferred to stay close to their intended destination, across the bridge, close to the court tents. According to volunteer Jessica Sandoval, influenced by distrust and a lack of clear information, MPP migrants also “came from places of trauma and have never been able to trust government officials.” Another volunteer, Tom Clarke, cited how camp residents were also aware of earlier instances in which asylum seekers got on buses provided by the Mexican government and did not fully understand where they were going, before being transported to Mexico’s southern border.

Visibility for MPP asylum seekers was inseparable from legal recognition; if they moved, camp residents feared the Mexican and US government would forget about their asylum claims. Sister Ester explained the viable fear of being forgotten: “Their only goal was to get the asylum process started. If they were to move further away it would be ‘out of sight out of mind’.” Volunteer Lucy Brown recalled her surprise at the asylum seekers’ strategic use of immobility:

They were thinking about the optics of the crisis. That really blew my mind. I thought, this was a no-brainer, of course they’ll go. They’re living out in the elements, primitive camping. But it was a resounding “No.” One woman told me—this is really the only leverage we have: our visibility. Later, when moving across to the levee, that was the same message I continued to get: “No, … The only leverage we have is that they don’t want us here in the plaza, and so that would be the only thing that would create pressure to ask the US to let us enter the US.

In January of 2020, the Mexican officials took the five existing portable toilets from the plaza and moved them across the levee. The Mexican federal government added 45 more portable toilets near the river to create an incentive for migrants to move from the plaza. Shortly thereafter, camp residents were informed of a planned relocation of the remaining resident in the plaza to the floodplain. According to attorney Ariana Blanco, “The plaza was cleaned out because people did not want to see an eyesore, so they moved them all up there”. Tom Clarke recounted that unlike the concrete floor of the well-lit plaza, “the entire camp now is in a floodplain. And it’s all mud”.

5.2. COVID-19 and Enclosure of the Camp

After both the United States and Mexico responded to the global coronavirus pandemic with lockdowns and closures, INM officials enclosed the relocated camp with fencing and concertina razor wire, with the stated intention of protecting residents from COVID-19 by regulating movement in and out of the camp. Coronavirus restrictions, the halting of US immigration processing, and the camp’s physical enclosure contained the spread of disease but also led to increased isolation, heightened surveillance of movement in and out of the camp by Mexican officials, and a dramatic reduction in the camp’s population.

The coronavirus pandemic further isolated the asylum seekers at the border and prolonged their wait as the US immigration courts were closed and court dates postponed indefinitely. At the camp itself, the INM restricted entry to the camp to current residents, disallowing entry for volunteers who were teaching classes for children and other services. In the words of Tom Clarke:

COVID shut everything down—we used to do fun things like art classes for the kids, photography classes, yoga classes, … two different church services. We had three different legal groups, providing different legal services and therapy. And we pretty much had to shut all of that down because it wasn’t essential. Our main focus just went straight to WASH (water, sanitation, and hygiene) and COVID.

Volunteer Lucy Brown lamented that “these restrictions have dramatically limited the presence of NGOs in the camp, which also has been detrimental for camp morale.”

The medical and humanitarian aid provided by Global Response Management (GRM), rather than the enclosure of the camp, was a leading factor contributing to the relative control of the virus among camp residents. GRM began working in the camp in October of 2019, months before the outbreak of COVID-19. Once relocated across the levee, volunteer engineers and paid resident workers played a key role in establishing WASH infrastructure at the camp as part of their strategy to combat the pandemic. This included building hand-washing stations and developing a drainage system for the camp. The organization also conducts medical COVID-19 testing while the organization Resource Center Matamoros (RCM) distributes supplies and oversees camp management. To contain the spread of the virus, a crew of four people made sure that there was always soap available at all 88 sinks and that every high-touch surface was decontaminated with bleach every hour. Registered nurse and GRM director Linda Simmonds attributed the successful containment of the COVID-19 to the work of GRM and limiting entrance to the camp to residents and medical personnel. “All of the cases that we’ve seen of COVID are really mild. We think that that’s because they’re living in an open-air environment where they’re not getting the concentrated viral loads that they would be if they were actually living in the community and houses. And so, ironically, their poor living conditions are keeping them from getting worse.”

The camp’s enclosure in the name of COVID-19 allowed Mexican INM to restrict entry to the camp to already existing residents and not allowing residents to return if they left for an extended period, effectively cutting off future camp expansion. Title 42 border closure, expedited processing of removal orders, and lack of legal and other resources under the coronavirus restrictions have also contributed to the dramatic decrease in the resident population. The camp’s enclosure combined with Title 42 rapid processing of removal orders resulted in a decline in the Matamoros MPP camp population. At its height in November 2019, an estimated 2500–3000 people lived in the camp centered around the plaza, as of December 2020, there were some 600 camp residents. Some had given up on the legal asylum process and found entry to the United States by other means, including crossing illegally with fees paid to drug cartels who control illicit crossing routes. According to attorney Lila Johnson, “All of the MPP hearings have been suspended over and over again for like six months and they’re realizing we’re not ever going to get a hearing.” Others, many of whom had been waiting for over a year in the camp, relocated elsewhere in Mexico or returned to their home countries.

Expulsion is expanding the scope of the humanitarian crisis at the border. New arrivals are now unable to petition for asylum and any migrant who attempts to cross is quickly processed and expelled. None of these migrants, whose numbers dramatically decreased due to the pandemic lockdown, were eligible to stay in either the MPP camp or in government shelters, creating a whole new class of homeless and vulnerable displaced people at the border. Those arriving after March 2020 were directed to a few overextended private shelters or, if they had funds, to overcrowded apartments and tenements in the city. Humanitarian groups whose primary focus had been helping asylum seekers who were processed through the US immigration system were now debating how to focus their resources and what to do with a growing number of migrants who arrive at the border and are immediately returned to Mexico.

5.3. Hurricane Hanna in the Camp

In late July 2020, Hurricane Hanna made landfall in south Texas as a category one hurricane, foregrounding MPP camp residents’ vulnerability and their use of im/mobility as agency. The hurricane brought over 15 inches of rain over two days and the Rio Grande quickly began to swell; the threat of a flood in the camp posed an imminent threat (

Harrison-Cripps 2020).

Hanna’s rain and wind combined with the very real possibility of the camp flooding and putting the asylum seekers in a life-threatening situation. Information circulated quickly among camp residents and service providers that city officials were considering releasing the floodgate upstream to prevent the city from flooding. In response, the INM began to coordinate with camp service providers to relocate the camp. The Catholic church volunteered a large soccer field near a church parking lot in Matamoros and authorities and non-profit workers began making arrangements to move people. Sister Ester recounted how “Mexico was ready to make the refugees get on the buses. The people didn’t want to leave. The [non-profit organization] was using the language ‘you must’, and ‘you have to’ evacuate…. we were told this was a critical situation in which lives were at risk.”

Asylum seekers resisted and ultimately refused to relocate. The asylum seekers resisted relocation despite flood danger for the same reasons they resisted relocation from the plaza to the floodplain—they wanted to remain together near the border. Many also did not trust Mexican authorities and feared that they would not be able to return. As community organizer Gabriel Alvarez explained, “People said, no, we are not moving until we see the river actually come up. They were scared that they were going to be moved and not going to be allowed back.”

While illustrating their precarity, this standoff over relocation also illustrates how asylum seekers exercised immobility as a strategy of resiliency and agency in a moment when they appeared to have none. This lack of trust, confusion about plans to open floodgates, and rumors of forced evacuation brought tensions to a breaking point between camp residents, Mexican officials, and camp service providers. Camp residents expressed collective anger that they had not been consulted about the attempted relocation and resented NGO cooperation with Mexican authorities in the proposed plan. In the aftermath, camp service providers agreed to always consult with the asylum seekers first regarding any plans and decisions they would make affecting the camp. The residents’ exercise of collective im/mobility, practices and power relations of decision making in the camp continue to shape the camp’s organization and governance today.

Rather than relocating, camp residents constructed makeshift rain gauges and used photography to systematically monitor the height of the river. Parts of the camp did flood, but not enough to force a relocation of its residents. Several residents moved tents or had to obtain new tents and materials to reconstruct what storm winds and water destroyed. GRM medical infrastructure also flooded, including the field hospital and two COVID-19 isolation areas. The flood waters turned the camp to mud and created additional sanitation and medical concerns. The GRM director explained, “What we’ve had an issue with right now is, since the flooding, we’re seeing a resurgence in waterborne illnesses and vector borne illnesses, or Dengue fever from mosquitoes. And seeing eye infection and skin infections from walking in floodwater and the gastrointestinal illnesses that come from that.” Apart from the health concerns from mosquitos, the flooded river drove snakes, rats, and other riverside animals into the camp. Describing the camp’s new floodplain location, Jessica Sandoval explained, “It’s wilderness what you see there. And so it is natural that there are rats living there, there are snakes. And because the water came up, the animals are trying to survive as well as our asylum seekers.”

5.4. Im/mobility and Increased Exposure to Organized Crime

Lost faith in their chances at asylum, combined with economic precarity caused by the pandemic, increased asylum seekers’ vulnerability to organized crime. US policies of exclusion further increased vulnerability of camp residents to organized crime by prolonging their wait in an area of high crime and cartel violence. For many years, deportation to the border region has meant extreme danger for migrants (

Slack 2019). One service provider described the migrants as a “honeypot” for drug trafficking organizations (DTOs), while another described asylum seekers as “fish in a fishbowl” that DTOs target for exploitation. DTOs control vast smuggling networks of drugs, people, and other illicit commodities along the borderlands and systematically kidnap, rape, torture, and kill vulnerable migrants as part of their daily operations. Crossing the river requires hiring smugglers who pay taxes to a cartel or work directly for cartels in the smuggling points they control (

Slack 2019). As such, when asylum seekers would leave the MPP camp and proceed to cross the river illegally, they were exposed to DTOs territories, smuggling routes, exploitation, and violence.

For nearly everyone choosing to remain in the camp, the pandemic has made their economic situation even more precarious. Prior to the pandemic, some camp residents received economic support from relatives or friends in the United States, which was diminished with the economic crisis resulting from the pandemic lockdown. Catholic Charities director Sister Ester and GRM director Linda Simmons discussed how organized crime exploits these precarities to recruit and employ destitute people in and outside the asylum seeker’s camp. “COVID makes people more vulnerable to organized crime, people have to go to work for cartels, or use organized crime to get across the river.” “Unfortunately, especially with COVID-19, we’re seeing recruitment amongst organized crime organization skyrocket, because when governments fail to provide basic resources to the people, they will go where they can get it, and most often, that’s organized crime.”

The option of remaining in the camp in Matamoros did not mean safety for the migrants. Several interviewees recounted the danger in the camp. Attorney Lila Johnson pointed out the lack of security, questioning “How are they going to protect themselves in a dome tent? …just zip it open.” She went on to highlight the risks for women and members of the LGBTQ+ community, stating that “women have been raped in the camp” and “a few trans folks have been brutally beaten up.” One solution MPP camp residents requested was to install lights in the camp for security because, in the words of Tom Clarke, “things happen in the dark.” Another community organizer, John Woods, linked the violence in the camp to the cartels. “They’re doing their business at night” when INM guards are not present. Scaling up from Matamoros to the MPP program and asylum seekers across the border, attorney Lila Johnson commented, “Almost 60,000 people are not allowed into the United States… It’s green pastures for the polleros (human smugglers). It’s green pastures for these low lying, low level cartels that operate in Matamoros, in Tijuana, Mexicali, and Nogales.”

6. Conclusions

“It’s an all-out war on asylum, coming from all angles”

(Tom Clarke, Matamoros MPP Camp Volunteer)

The novel coronavirus detracted media attention away from the humanitarian crisis unfolding on the US-Mexico border, yet the situation of asylum seekers was never more dire due to the dramatic reworking of the asylum system. Beginning in January 2018, the US shifted its exclusionary policies from a detention and deportation approach to one of denial and expulsion as it closed the southern US border to Spanish-speaking asylum seekers. We focused in particular on three key policies that constitute an ontological shift in the US asylum system: the Orwellian-named ‘Migrant Protection Policy’ (a.k.a ‘Remain in Mexico’), bilateral third-country agreements, and Title 42 and the space of exclusion created in Matamoros, Mexico. The United States tied asylum seekers to the border through its MPP program, converting Mexico’s northern border into an unfunded zone of detention outside of its sovereignty in what

Maillet et al. (

2018) call ‘inclusion through exclusion’. Following MPP, the US implemented policies directly aimed at excluding especially Central American asylum seekers, violating international principles of non-refoulement through third-party agreements to return to Northern Triangle countries that cannot protect their human rights. The COVID-19-related indefinite suspension of accepting and processing asylum cases altogether compounded asylum seekers’ immobility and heightened their vulnerability.

Focusing on the embodied consequences of these legal geographies and policies of asylum exclusion and expulsion exposes the increased precarity and vulnerability for the tens of thousands of people waiting for their asylum hearings along the US-Mexico border. The pandemic restrictions that closed the border to asylum seekers (Title 42) prolonged the wait indefinitely along the dangerous northern Mexican border in shelters, tenements, and asylum seeker camps. Narrowing in on the MPP asylum seeker camp in Matamoros, Mexico during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed how the US government weaponized the virus to cement the transition of the US asylum system to one of expulsion and exclusion.

The US’s legal policies of exclusion produced the MPP camp as a space of exception (

Agamben 2005) that led to heightened vulnerability for migrants waiting for their US court date in Matamoros, Mexico, leaving individual advocates and humanitarian groups to step in and fill the void of state or institutional service providers. The experiences of religious, legal, and social service providers to the MPP camp expose how these policies of exclusion interact with one another—MPP and Title 42 in particular—and specifically, how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the already precarious situation of asylum seekers in the MPP camp. This research reveals how power operates in these spaces of exclusion through practices of im/mobility exercised by a diversity of unequally positioned actors. Clearly, the Trump administration used COVID-19 to impose immobility upon asylum seekers in spaces of expulsion along the northern Mexican border. At the same time, we witness how asylum seekers as in the MPP camp collectively exercised their immobility as a strategy of political visibility and collective solidarity in pursuit of their asylum claims. When Mexican authorities wanted to move the camp from the plaza to the floodplain between the levee and the river, the asylum seekers resisted the move. Similarly, when Hurricane Hanna’s flood waters directly threatened the camp as the City of Matamoros considered releasing the dam to save the city, asylum seekers again refused to move.

While not romanticizing the constrained agency of asylum seekers, we acknowledge how they leveraged the collective solidarity and the immobility existing in the camp to render visible the violence and injustice of policies of exclusion. We analyze the camp as the material manifestation of the MPP policy, as well as a site and spatial strategy of resistance among asylum seekers who leveraged their collective power to contest their multifaceted precarity. MPP migrants were also active contributors to social media, using their cell phones and apps such as WhatsApp and Facebook to post pictures, videos and descriptions of the conditions in the camp to increase their visibility and to remind the wider public of the urgency of their situation and the need for a legislative solution.

At the same time, Mexican immigration and Matamoros city officials also employed COVID-19 as pretext to shape the evolution, permanence, and visibility of the camp. Thanks to the gallant, but constrained response by grassroots NGOs to the crisis in the MPP camp, the public health impacts of COVID-19 were limited; infection rates were similar to or lower than surrounding Matamoros and Brownsville populations. It took Hurricane Hanna, alongside the hypermobility of the virus, to remind us of non-human actors shaping the daily life, precarity, and agency of asylum seekers during the pandemic. As flood waters threatened the camp, residents chose to face the flood waters and encroaching vermin rather than lose their collective visibility that bears witness to the violence of the Trump administration’s dismantling of the US asylum system. The MPP program is a key example of the Trump administration’s transformation of the asylum system from a logic of detention to practices of expulsion. Title 42 dramatically deepened the temporal precarity of MPP asylum seekers as their cases became indefinitely suspended. The indefinite suspension of the asylum system following months or years of waiting eroded what little hope many asylum seekers had for pursuing legal channels into the United States.

The US’ steps towards dismantling its asylum system were part of a broader, global crisis wherein an increasing number of ‘survival migrants’ are fleeing political, economic, social, and environmental conditions in their home countries only to be met by increasingly restrictive legal environments. For decades, countries of the European Union and Australia have used spatial strategies such as interdiction, offshoring, return protocols, and readmission agreements to fundamentally undermine the obligations of international refugee law and the basic human rights it entails (

Maillet et al. 2018). These ‘spatial fixes’ reveal how human rights violations operate through and produce space. Such policies further punish asylum seekers—dehumanized as security threats in wealthy countries to which they appeal for, yet are unlikely to receive, safe harbor.