Abstract

Values are guiding constructs of social action that connote some actions as desirable, undesirable, acceptable, and unacceptable, containing a normative moral/ethical component, and constituting a guide for actions, attitudes, and objectives for which the human being strives. The role of religion in the development of moral and ideal behaviors is a subject of concern and object of theoretical and empirical debate in various sciences. Analyzing sociodemographic and religious variables, the present work aimed to understand the contribution of religious variables to the explanation of Schwartz’s human values and to identify an explanatory model of second-order values, i.e., self-transcendence, conservation, self-promotion, and openness to change. This study was carried out with a representative sample of the Portuguese population, consisting of 1270 participants from the European Social Survey (ESS), Round 8. Benevolence (as human motivational value) and self-transcendence (as a second-order value) were found to be the most prevalent human values among respondents, with the female gender being the one with the greatest religious identity, the highest frequency of religious practices, and valuing self-transcendence and conservation the most. Older participants had a more frequent practice and a higher religious identity than younger ones, with age negatively correlating with conservation and positively with openness to change. It was concluded that age, religious identity, and an item of religious practice contribute to explain 13.9% of the conservation variance. It was also found that age and religious practice are the variables that significantly contribute to explain 12.2% of the variance of openness to change. Despite the associations between psychological variables (values) and religious ones, it can be concluded that religious variables contribute very moderately to explain human values. The results obtained in this study raised some important issues, namely, if these weakly related themes, i.e., religiosity and human values, are the expression of people belief without belonging.

1. Introduction

Values have an intangible nature. Their study is a complex issue because they are not observable or able to be measured and because they are often mixed with other psychosocial phenomena and present historical and cultural variability in relation to content (Araújo et al. 2020). Thus, the term value can connote a wide variety of meanings and different interpretations (Ives and Kidwell 2019). Values play a central role in the lives of individuals and cultures/societies and can be characterized either at the individual or group level, i.e., members of a society, organizations, religious groups. Collective/social values, also known as cultural values, represent the objectives that members of a society are encouraged to adhere to and pursue in order to justify their actions (Sagiv et al. 2017). In turn, individual values, also named personal values, are the principles that rule our lives, guiding, conditioning, and directing behaviors, actions, and attitudes.

Throughout human history and evolution, religion has been found to be one of the most important and comprehensive social institutions, touching and shaping virtually all spheres of culture and society (Ives and Kidwell 2019; Nascimento et al. 2017), providing people with frames of reference for the organization of life in general, whether individual or group, through its mysteries, and existential and metaphysical questions about the absolute beginnings, and ultimate ends (Nascimento and Roazzi 2017).

Religiosity and values play a crucial role in the history of human civilization, since the past until today, religious differences based on values substantially contribute to social conflicts (Musek 2017). Thus, the search for values related to religion is a relevant task in psychology and other social sciences (Leite et al. 2020). These two constructs are correlated; however, it is not clear whether this is because certain values predispose someone to become and remain religious or if religious people are more likely to adopt these values (Chan et al. 2020). It is well known that the religious groups that individuals join and the extent of their religiosity are important aspects both in personal and social identity (Sagiv et al. 2017). It can be concluded that religiosity and values are intrinsically related in all aspects of human life).

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Human Values

Each of us has numerous values, which differ in the degree of importance that each person attributes to them (Schwartz 2012). Values can be defined as beliefs, but they are beliefs inextricably linked to emotion, not to strict, objective ideas. They are motivational constructions, i.e., desirable objectives in specific situations (Granjo and Peixoto 2013; Schwartz 2012). Thus, when we think of religious values, we refer to what people strive to achieve (Cieciuch et al. 2016), transcending specific actions and situations; that is, they are broad objectives that are relevant in various situations. They have an abstract nature, which makes it possible to distinguish them from norms and attitudes (Sagiv et al. 2017). For Schwartz (2012), values are defined as objective and transitional, desirable and of variable importance, which serve as a conductor guide in people’s lives (Pantaléon et al. 2019). The priorities of each individual start from their individual differences and are significantly related to real behaviors, i.e., pro-social, antisocial, environmental, political, consumer, and intellectual behaviors (Schwartz and Bardi 2002). Pantaléon et al. (2019) show that the more people are altruistic, the more importance they attach to self-transcendence and the less importance to self-promotion. On the other hand, the more self-directed they are, the more importance they attach to self-promotion and the less importance they attach to self-transcendence. Values are constituted as central elements of culture, whatever it may be and underlie the socialization of new generations in an explicit or implicit way (Cieciuch and Schwartz 2017). Values are considered to be relatively stable personal attributes, which are largely fixed when adulthood is reached and quite resistant to change (Hofstede 2001; Rokeach 1973; Schwartz and Bardi 2002), since changing the values of a person would imply changing the core of their identity (Sagiv et al. 2017). Therefore, it can be stated that values are by definition the beliefs that serve as guiding principles of life (Musek 2017). Together with appropriate behavioral intentions, values can have a profound impact in daily and life decisions, as well as in routine. However, daily experiences are those that massively testify to the importance of religious differences in values and values’ orientations. In some cases, the value system can serve as an ideological basis for serious forms of intolerance, prejudice, discrimination, and violence in society, as well as leading to religious terrorism, which is notorious in the contemporary world (Leite et al. 2019; Musek 2017).

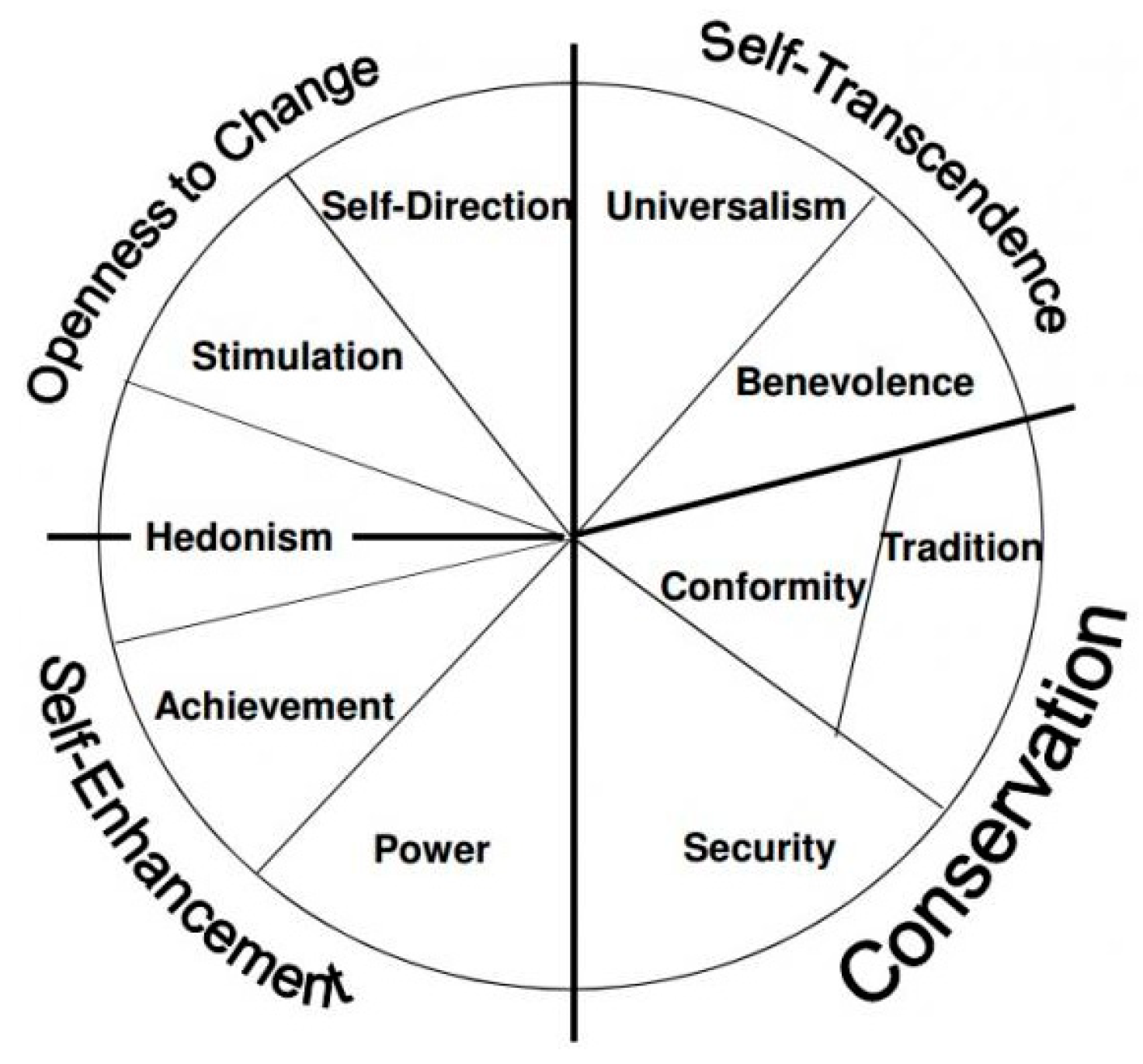

The model of values proposed by Schwartz (2012) is predominantly found in psychological research. Schwartz (1992) first defined values as trans-situational, desirable, transcendent, and of varying importance objectives, that served as guiding principles in the life of a person or a group (Ariza-Montes et al. 2017). In total, he proposed a circular organization of 10 types of motivational values common to individuals and transversal to the cultural context (Bilsky 2009; Maio 2016), which came from three universal requirements of the human condition: the needs of individuals as biological organisms, requirements for coordinated social interaction, and the groups’ need for survival and well-being (Sagiv et al. 2017; Schwartz 2012).

The 10 motivational values can be organized in a two-dimensional structure, composed of four fundamental orientations—second-order values (Figure 1). In turn, these four orientations are organized in two basic and bipolar conceptual dimensions/axes. A first axis reflects the conflict between the acceptance of others as equals and the concern with their well-being versus the pursuit of individual success and dominance over others, in which a set of values such as self-transcendence (universalism, benevolence) and values of self-promotion (power and achievement) are included (Sagiv et al. 2017; Schwartz 2012). The second axis reflects the conflict between the desire for intellectual autonomy, freedom of action and orientation for change versus obedience, the preservation of traditional practices, and the protection of stability, where the values of openness to change are included (hedonism, stimulation, and self-direction), and conservation values (conformity, tradition, and security) (Sagiv et al. 2017; Schwartz 2012). Crossing these two axiological axes of second-order values with the general classification of basic human values, it is possible to state that the first axis concerns ethical values, and the second practical values (Cieciuch et al. 2016; Francescato et al. 2017; Granjo and Peixoto 2013). Later, in 1992, Schwartz delimited a new instrument, the Schwartz’s Values Scale (SVS), based on the Rokeach Value Survey (RVS) (Rokeach 1973), developing a more differentiated response to assess the items of individual values. Schwartz developed another measure to study the values, the Schwartz’s value profile “Portrait Values Questionnaire” (PVQ) (Davidov et al. 2008; Schwartz 2012). The PVQ was designed to measure the same 10 basic value orientations, measured by the SVS. However, it was developed with the purpose of being applied to children from 11 years old, people with a low level of education, and the elderly, as well as to verify if the theory of values was valid, regardless of the instrument used. The PVQ presented interviewees with a more specific and less cognitive task than the search for previous values. Accordingly, SVS derived from versions prior to the PVQ (Schwartz 2003; Schwartz 2011) and was used to assess/study people’s value systems, based on human motivations that promote the satisfaction of needs. SVS has been used in the Portuguese population, in the scope of the project of the study of values at European level, the European Survey Values (Davidov et al. 2008; Schwartz 2011; Vala et al. 2006; Vala et al. 2010).

Figure 1.

Schwartz motivational values. From Schwartz (2012).

2.2. Association between Religiosity and Schwartz’s Values

Religion is constituted as a cultural, social, and historical phenomenon, developing from the experiences of life in community. Accordingly, religious beliefs and customs markedly influence the formation of moral, social, and even political and economic value systems (Kørup et al. 2020; Santos et al. 2012). Theoretically, values and religion are understood to be considerably related in various ways (Chan et al. 2020; Ives and Kidwell 2019; Musek 2017), in different cultural and religious groups (Saroglou et al. 2004). This association between values and religion can be established in two different ways: directly or indirectly. The association is designated as direct, when the transmission of religion occurs through socialization, namely within the family context, being considered as part of a more global transmission of values (Oman 2018). In turn, it is called an indirect association when individual differences, whether the characteristics are different from others as well as the specific personality, predispose individuals to be, remain, or become religious (Beckford 2019).

This theme was the subject of study by philosophers, sociologists, and political theorists, such as, for example, Marx (1964) who saw religion as the opium of the masses, being the source of the motivation for change in society, and who suggested that religious people tend to value humility and obedience and to devalue independence and power. Religious people tend to be more conservative in their political attitudes (Devos et al. 2002) and therefore are less involved in risky behavior, which means that they have a certain tendency, oriented towards security (Chan et al. 2020). They tend to favor values that promote the conservation of the social and individual order (tradition, conformity and, to a lesser extent, security) and, conversely, not to value the values that promote openness to change (stimulation, self-direction). They also favor values that allow limited self-transcendence (benevolence, but not universalism), and devalue hedonism and, to a lesser extent, values that promote self-promotion (power, achievement) (Saroglou et al. 2004). It is notorious that religion influences the priority of values and consequently the political choice. Thus, individuals associated with some religions tend to be more committed to the values of conservation (conformity, tradition, security), i.e., values that express order, self-restraint, and commitment to the customs and ideas of traditional culture, are positively related to religious commitment (Schwartz and Huismans 1995). This finding is consistent across countries with different economic, cultural, and religious characteristics (Saroglou et al. 2004). These conservation values are also correlated by preference for right-wing and conservative ideologies, in different cultural contexts and political systems (Aspelund et al. 2013; Caprara et al. 2017).

Regarding different religious denominations (Christians, Jews, and Muslims), the literature found that religiosity was considerably associated with low hedonism, stimulation, and self-direction, and highly associated with conformity and tradition. In turn, benevolence and security had a high association. The same cannot be stated for universalism, power, and achievement, which had a low association. Among these Christian, Jewish, and Muslim groups, there were also some cultural similarities in the way they ordered values as priorities according to religion, i.e., the similarity between Jews and Catholics was very high, as well as between Muslims and Catholics (Papastylianou and Lampridis 2016; Roccas 2005). In another study, carried out by Musek (2017) with six different religious denominations (Orthodox, Buddhist, Hindu, Jew, Muslim, and Catholic), differences were found, and the Orthodox group were those that presented higher scores in values of universalism, benevolence, conformity, and tradition, which was also the group in which friends had more prominence in their life; they also presented the lowest scores in hedonism. The Buddhist group emphasized the importance of politics and autonomy; however, the values of achievement, stimulation, and self-direction were small. The Hindu group presented little security, and also attributed little importance to the family, but it was the group that presented greater stimulation. The Jewish group was the one with the highest rankings in values of power, and attributed a very low importance to friends, leisure, and work. In turn, the Muslim group was the one with the highest values in security, achievement, and hedonism, but it had little autonomy. The Catholic group had higher scores on self-direction values and attached great importance to leisure and work.

Durkheim (1964) claimed that Catholics, in comparison with Protestants, were more likely to emphasize values such as respect for tradition and community ties, while Protestants were more likely to give priority to autonomy and freedom. Despite the recognition that different religions have a lot in common in their basic value systems, the adversities between the numerous adherents and groups of different religious denominations are still accentuated (Musek 2017), and there may be differences in values even among individuals within the same religious community (Woodhead 2017). In monotheistic religions, the pattern of correlation between religiosity and values appears consistently, i.e., people committed to religious groups attach greater importance to values that express avoidance of uncertainty and less importance to values that express hedonistic desires and independence (Roccas 2005).

The magnitude of the effects between this association between religion and human values seemed to depend on the socioeconomic development of the countries in question. It has been proven that the more developed the country was, the less positive the association between values and religiosity, namely in conservation values (conformity, tradition, and security), contrary to the values of universalism, achievement, and self-direction, which presented a less negative association (Chan et al. 2020). With regard to benevolence, this was more positive, and power was more negative in more developed countries. As for the values of hedonism, there were no influences of socioeconomic development in the association between values and religiosity. It is also possible to establish a comparison between Mediterranean countries and Western countries, with the presence of religiosity in the former reflecting higher conservation values (conformity, tradition, and security), when compared to the latter (Chan et al. 2020). In turn, Western countries presented lower values in hedonism and openness to change (hedonism, stimulation, and self-direction). As for benevolence, power, and achievement, no differences were observed (Saroglou et al. 2004).

It is found that the literature is useful in associating Schwartz’s religion and values, but no study has attempted to understand how religiosity contributed to the explanation of Schwartz’s human values and to identify an explanatory model of second-order values, i.e., self-transcendence, conservation, self-promotion, and openness to change.

3. Methods

3.1. Objectives

Using socio-demographic and religious variables, the general objective of this study is to understand the contribution of religious variables to the explanation of Schwartz’s human values in a representative sample of the Portuguese population. Specific objectives include relating the sample to religious and psychological variables (Schwartz’s values); and to identify an explanatory model of the second-order values of Schwartz (self-transcendence, conservation, self-promotion, and openness to change).

The following hypotheses were considered:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Older and female participants are expected to have higher self-transcendence and conservation values than younger and male participants. In turn, the latter are expected to present the highest order values self-promotion and openness to change;

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

It is expected that there are significant associations between religious variables and Schwartz’s values;

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

it is expected that age, religious identity, and religious practice explain the second-order variables of Schwartz, i.e., conservation and openness to change.

The present research is a transversal one, with a descriptive-correlational design, intending to explore the associations between variables with a view to describing them (Ribeiro 2007). The data was obtained from the European Social Survey (ESS), Round 8 (European Social Survey Round 8 Data 2016).

3.2. Sample

The characteristics of the sample originating from the Round 8 of ESS (European Social Survey Round 8 Data 2016) are presented in Table 1. The sample is comprised of 1270 participants, mostly female, with a mean age of 52 years old and a mean of 10 years of education, most of them being active (workers, students, and housewives). Most of the sample has no children, and lives at home and in medium-sized cities. The main source of income is work for the majority of the sample, most of it being able to meet its financial commitments.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample (N = 1270).

3.3. Procedures

This study did not require prior authorizations because data used are public. However, the Scientific Council of the Catholic University of Portugal commented on the relevance of the study, having agreed with it. To answer the research question “Does religiosity contribute to explain Schwartz’s values?”, several items of the ESS, Round 8 (European Social Survey Round 8 Data 2016), were selected.

3.4. Measures

3.4.1. European Social Survey (ESS)

ESS is a transnational academic survey that measures the attitudes, beliefs, and behavior patterns of different populations in more than thirty countries. The ESS sample design in Portugal excludes the Azores and Madeira and locations with fewer than 10 houses. The samples are representative of all individuals who are at least 15 years of age or older, have no upper age limit, and are residents of the country under study (Europeansocialsurvey.org 2019).

3.4.2. Sociodemographic Questions

Aiming to characterize the sample, the information obtained through the application of the ESS Round 8 in 2016 (European Social Survey Round 8 Data 2016) considered significant for the present study was used: gender, age, education, work activity, co-residence of parents and children, typology of the place of residence, main source of income, and feeling about income.

Gender is assessed in a nominal variable where 1 applies to men and 2 to women. The age variable (scalar) is represented by the number of complete years of age. The question “How many years of education have you finished?” (scalar variable) is answered with a number that corresponds to the rounding to the whole number immediately afterwards. In the question “Which of the following situations apply best to what you did in the last 7 days?” (nominal variable), the response modality was dichotomized into active (workers, students, and housewives), corresponding to category 1 the responses of type 1 and 2, and inactive (unemployed, retired, sick, and others) corresponding to category 2, aggregating all other response modalities. The variable “Have you ever had children of yours, adopted children or foster children or children of a partner living with you?” (nominal variable) had as possible answers 1 or 2, where 1 refers to the affirmative answer and 2 indicates the negative answer. In the question “What is the phrase that best describes the place where you live?” (nominal variable), answer 1 corresponds to “a big city”, 2 to “suburbs or surroundings of a big city”, 3 to “a village or a small town”, 4 to “a village”, and 5 to “a farm or house in the country”. This variable was also recategorized, adding categories 1 and 2 in 1 (large cities and surroundings), 3 and 4 in 2 (medium cities and towns), and 5 started to correspond to 3 (countryside). In the item “What is the main source of income for people living in this house?” (nominal variable), the possible answers were dichotomized, with 1 corresponding to “wage” and all the others combined in category 2. The item “Which of the following descriptions is closer to what you feel about the current income of people living in this house?” (nominal type) corresponds to answers between 1 and 5, where 1 corresponds to “allows to pay the expenses”; 2 to “allows to live in comfort”; 3 to “it is difficult to live”; 4 to “it is very difficult to live”; and 5 to “does not answer”.

3.4.3. Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ)

PVQ derives from previous versions of the SVS (Schwartz 2003; Schwartz and Bardi 2002) and is used to assess/study people’s value systems, based on human motivations that promote the satisfaction of needs. PVQ has been used in the Portuguese population, as part of the project to study values at European level, the European Survey Values (Davidov et al. 2008; Schwartz 2011; Vala et al. 2006; Vala et al. 2010). It consists of 21 items that describe the preferences related to the values, so each participant is asked to explain how these preferences coincide with theirs (from 1 = it has nothing to do with me to 6 = exactly like me). Each item consists of two descriptive phrases, one refers to the importance given to a specific value and the other to a complementary feeling related to the same value. According to the Schwartz’s model, human values are grouped into 10 motivational values—universalism, benevolence, conformity, tradition, security, power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, and self-direction, grouped, then, into four dimensions of a second-order: self-transcendence (universalism and benevolence); conservation (conformity, tradition, and security); self-promotion (power and achievement); and openness to change (hedonism, stimulation, and self-direction). These four dimensions are further organized into two bipolar axes, one opposing values of self-transcendence and self-promotion and another opposing values of openness to change to values of conservation. No item should be used in isolation to represent any value.

Corroborating its cross-cultural validity, more than 150,000 people from representative samples from 32 countries have already responded to this scale, according to Schwartz (2011). Its internal consistency is on average 0.56, varying between 0.36 (tradition value) and 0.70 (achievement value). Considering the four dimensions of the second order, based on sample data from the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, Schwartz (2003) presents values for internal consistency ranging from 0.74 for self-transcendence and 0.81 for self-promotion (Granjo and Peixoto 2013).

3.4.4. Items Related to Religion

Three questions related to the participants’ religiosity were used, using Likert-type response scales. The first question “How religious are you?”, aims to measure the participants’ religiosity, with possible answers ranging from 0 “Not at all religious” to 10 “Very religious”. The second question, “How often do you attend religious services, in addition to special occasions?”, can be answered by participants between 1 “Every day” to 7 “Never”. Finally, the last question, “How many times do you pray apart from religious cults?”, can be answered between 1 “Every day” to 7 “Never”.

3.5. Statistics

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences IBM SPSS Statistics 25 was used to analyze the data. Mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum, skewness and kurtosis descriptive statistical analyses, reliability analyses, through Cronbach’s Alpha, difference analysis (Student’s t-test and ANOVA), correlation analysis (Pearson’s r and Spearman’s rho), and regression analysis, i.e., multiple linear regression (MLR), were performed.

At first, MLR was carried out with socio-demographic variables that were significantly related to the dependent variable in a first model, and religious variables in a second model. In the second MLR, only those variables that contributed significantly to explain the dependent variables were retained.

The normal distribution of the sample was ensured by the values of skewness (|Skw| < 3) and kurtosis (|Krt| < 10) (Marôco 2010). Considering the sample size (N = 1270), parametric tests were used. Despite the sample size and given the ordinal nature of some variables, non-parametric tests were also applied (Pestana and Gageiro 2014). This study assumed a value of p < 0.05 as the significance value for the four hypothesis test results.

4. Results

The descriptive statistics of Schwartz’s scale of motivational values and second order allows to conclude that item 18 “It is important to be loyal and dedicated to friends and close people”, presents the lowest average of all items, which means that is the item answered by most of the respondents. On the contrary, item 2 “It is important to be rich, to have money and expensive things” is the one with the highest average, being the one less reported by the participants. The “Not like me” answer modality is the most chosen of all modalities in item 2, meaning that for 53.2% of the respondents it is not important to have a lot of money and expensive things. The “Not like me” answer modality is also the least chosen in item 18, meaning that more than 70% of the respondents consider themselves to be loyal and dedicated people to the nearest ones.

Respecting the description of the subscales of motivational values and second-order values, benevolence presents itself with a lower average value registered, in contrast to power. Regarding second-order values, self-transcendence appears as the dimension with the lowest average, meaning that it is the highest-order value that is most represented in the sample. Concerning the reliability of these dimensions, the values of alpha of Cronbach in motivational values range between 0.25 (power) and 0.69 (benevolence), the remaining values being as follows: achievement (0.67); hedonism (0.64); universalism and stimulation (0.60); security (0.55); conformity (0.51); self-direction (0.46); and tradition (0.38). Regarding the reliability of the highest-order values, they range between self-promotion (0.54) and self-transcendence (0.74), presenting openness to change (0.70) and conservation (0.65) intermediate values.

Some subscales of the motivational and second-order values scale have very low internal consistency values. As verified by the authors of the scale, on average, in the samples of several studies, power is the item with the lowest Cronbach’s alpha value. In this study, benevolence has the highest value, while the authors of the original version (Granjo and Peixoto 2013; Schwartz 2011) recorded the highest value in achievement.

The descriptive statistics of the items related to religion allows to verify that in relation to the question “How religious are you?”, responses focus on options between 5 and 8 (with 5 including 268 respondents and 8 including 156). The response modalities “Less frequently” and “Never” are the most frequent responses in relation to the question “How often do you attend religious services, in addition to special occasions?”. With regard to the question “How many times do you pray apart from religious cults?”, the answers focus on “Every day” and “Never”, according to Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of religion items (N = 1270).

It was found that the female gender (M = 6.20; SD = 2.75) has a higher religious identity (t (1266) = −9.632; p < 0.010) than the male gender (M = 4.66; SD = 2.89). Moreover, the female gender (M = 4.73; SD = 1.76) has a higher frequency of religious celebrations (t (1191, 857) = 7.253; p < 0.010) than the male gender (M = 5.43; SD = 1.63). In addition, the female gender (M = 2.83; SD = 2.29) prays more (t (1078, 728) = 13.084; p < 0.010) than the male gender (M = 4.62; SD = 2.49). Age correlates positively with religious identity (r = 0.310; p < 0.010) and negatively with the number of times the person prays (r = −0.368; p < 0.010) and the number of times the person attends religious celebrations (r = −0.260; p < 0.010), i.e., older participants have a more frequent religious practice than younger ones, as well as a greater religious identity than these.

The correlations between religious variables oscillate between r = 0.580 (p < 0.001) and r = 0.645 (p < 0.001), which explains the absence of multicollinearity. If it is above 0.8, there is multicollinearity (Kumar 1975).

Concerning the correlations between the dimensions of the PVQ (first- and second-order values) and the sociodemographic variables, highlighting the highest correlations, it was verified, in relation to the first order variables, that conformity correlates significantly, negatively with age (r = −0.205) and positively with the number of years of education (r = 0.300). These results mean that the older respondents have higher conformity values since on the scale of the values, lower value responses translate higher scores (1 = “much like me” and 6 = “nothing like me”). Similarly, respondents with more years of education show less conformity. Tradition also correlates significantly and positively with education (r = 0.273), i.e., the higher the education, the lower the scores in tradition. Achievement is positively correlated with age (r = 0.210). Thus, the older the respondents, the lower the achievement value is reported. Hedonism and stimulation correlate significantly and positively with age (r = 0.311; r = 0.324), meaning that respondents of higher ages show lower results in these dimensions. In addition, stimulation is negatively correlated with education (r = −0.211), meaning that higher education corresponds to greater stimulation.

In relation to second-order variables, and to partially respond to H1 (older participants are expected to have higher self-transcendence and conservation values than younger participants), Pearson’s correlation was calculated and it was found that conservation correlates negatively with age (r = −0.220), confirming H1, and with work activity (rs = −0.220) and positively with education (r = 0.322). Thus, conservation is shown to be greater in respondents at an older age and also greater in inactive ones, when compared to those active in labor terms, being lower when education is higher. On the other hand, openness to change is positively correlated with age (r = 0.342) and work activity (rs = 0.210) and negatively with education (r = −0.253). In this case, older and more active respondents show less openness to change and those with more education express greater openness to change. However, age does not correlate with self-transcendence (r = 0.044).

Responding to the second part of H1 (female participants are expected to have higher self-transcendence and conservation values than male participants and in turn, the latter are expected to present the highest order values self-promotion and openness to change), the Student’s t-test was used. In Table 3, the gender differences in relation to second-order values are presented. There are no differences in relation to self-promotion; the female gender values self-transcendence and conservation more than the male gender and males value openness to change more than females.

Table 3.

Differences in the means of second-order dimensions in relation to gender.

To answer H2 (it is expected that there are significant associations between religious variables and Schwartz’s values), Spearman’s correlation was determined and it was verified that the religious identity “How religious are you?” correlates above r = 0.200, significantly and negatively with conformity, tradition, and conservation. These results mean that respondents who express more religiosity subscribe to higher values in conformity, tradition, and conservation (Table 4). Regarding religious practice “How often do you attend religious services, in addition to special occasions?” and “How many times do you pray apart from religious cults?” correlate above r = 0.200, significantly and positively with conformity, tradition, and conservation. These results mean that respondents who show less religious practice subscribe to lower values in conformity, tradition, and conservation (Table 4).

Table 4.

Spearman rho correlations between religion, motivational values, and second-order values.

Self-promotion showed no correlation with religious items; therefore, it was not possible to find a model that could explain it (Table 4). The correlations between self-transcendence and religious variables were very low and, therefore, when trying to estimate an explanatory model, the results were not acceptable (Table 4).

Intending to answer H3 (it is expected that age, religious identity, and religious practice explain the second-order variables of Schwartz, i.e., conservation and openness to change), MLR analysis was carried out with a view to knowing the sociodemographic and independent variables that explain conservation. In the two MLR for the second-order dimensions conservation and openness to change (Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8), all sociodemographic variables were included in a first model and, in a second model, all three religious variables. Most of the sociodemographic variables were not found to be significant (Table 5 and Table 7), and the models presented in Table 6 and Table 8 include only those variables that were found to be significant in explaining the variance of the dependent variables. In the first MLR of conservation, the variable children living at home did not enter the regression model because it did not correlate significantly with the dependent variable conservation (Table 5). In this first MLR, the second model found was significant (F(13, 639) = 10.435; p < 0.001; Adjusted R2 = 0.158), however, many of the independent variables did not significantly contribute to the model. As the non-significant variables were removed from the model, by decreasing order of non-significance, it was found that age, religious identity, and an item of religious practice “How many times do you pray apart from religious cults?” are those that significantly contribute to explain 13.9% of the variance of the second-order dimension conservation (Table 6). The second model of this MLR was found to be significant (F(3, 1229) = 67.279; p < 0.001; Adjusted R2 = 0.139).

Table 5.

Multiple linear regression 1: Contribution to the explanation of the second-order dimension conservation.

Table 6.

Multiple linear regression 2: Contribution to the explanation of the second-order dimension conservation.

Table 7.

Multiple linear regression 1: Contribution to the explanation of the second-order dimension openness to change.

Table 8.

Multiple linear regression 2: Contribution to second-order dimension openness to change.

In order to answer H3, MLR analysis was carried out aiming to know the sociodemographic and independent variables that explain the openness to change. The procedures carried out for the MLR described above were repeated for openness to change. In the first MLR of openness to change, the variable children living at home did not enter the regression model because it did not correlate significantly with the dependent openness to change variable (Table 7). In this first MLR, the second model found was significant (F(13, 644) = 5.960; p < 0.001; adjusted R2 = 0.089), however, many of the independent variables did not significantly contribute to the model. As the non-significant variables were removed from the model, by decreasing order of non-significance, it was found that age and religious practice, “How often do you attend religious services, in addition to special occasions?”, are those that significantly contribute to explain 12.2% of the variance of the second-order dimension openness to change (Table 8). The second model of this MLR was found to be significant (F(2, 1240) = 87.650; p < 0.001; adjusted R2 = 0.122).

5. Discussion

Using socio-demographic information, human values, and religious variables from the ESS database, Round 8 (European Social Survey Round 8 Data 2016), this study intended to understand the contribution of religious variables to the explanation of Schwartz’s human values in the Portuguese population. The specific objectives included relating the sample to religious and psychological variables (Schwartz’s values) and to identify an explanatory model of the second-order values of Schwartz (self-transcendence, conservation, self-promotion, and openness to change).

The female gender has a higher religious identity than the male gender. Furthermore, the female gender presents a frequency of religious celebrations which is more assiduous than the male gender. Moreover, the female gender prays more than the male. Age correlates positively with religious identity and negatively with the number of times a person prays and the number of times attending religious celebrations, i.e., older participants have a more frequent religious practice than younger ones and a greater religious identity than younger ones. These results corroborate studies previously carried out in this domain, such as the ones carried out by Heelas et al. (2005) and Trzebiatowska and Bruce (2013), which prove that the female gender is more involved and interested in institutional religion and spirituality than the male gender. Trzebiatowska and Bruce (2012) confirmed that women in Western nations attend church more, pray more daily, are baptized and confirmed, read scriptures, report religious experiences, watch religious TV programs, express greater belief in God, believe in the afterlife, and describe religion as personally important, when compared to men. In addition, and according to Heelas et al. (2005) and Trzebiatowska and Bruce (2013), participation in holistic spiritual activities, and non-materialistic beliefs, in the United Kingdom, are more prevalent in women than in men. In fact, female individuals are more religious and believers than male ones (Luria and Katz 2019).

As for the importance attributed to religiosity and spirituality among different age groups, the study by Robinson et al. (2019), carried out in 3 different countries, United Kingdom, France, and Germany, shows that the group of older individuals presents greater religiosity than younger participants. Moreover, the study by Khukhlaev et al. (2018), carried out with young Russians from 3 different religious groups, Orthodox Christians, Buddhists, and Muslims, demonstrates the same when considering that believing individuals are often represented by the older generations. Believers are also more committed to values. According to Amado and Diniz (2017) and Leite et al. (2020), age is positively correlated with the importance attributed to religion and its practice.

In terms of gender, differences were found in relation to second-order values. The female gender values self-transcendence, in agreement with Francescato et al. (2017) and conservation, which is corroborated by Lönnqvist et al. (2018), stating that becoming a parent changes the values of women, but not men, and new mothers’ value priorities shift towards conservation over openness to change. The male gender values openness to change more, since there are no differences regarding self-promotion.

With respect to H1 (older and female participants are expected to have higher self-transcendence and conservation values than younger and male participants, and in turn, the latter are expected to present the highest order values self-promotion and openness to change), it was found that age negatively correlates with conservation, confirming H1, and positively with openness to change. However, age does not correlate with self-transcendence. The literature is not consensual with these results. Schwartz (2003) demonstrated that age has strong positive correlations with conservation values (conformity, tradition, and security), weak positive correlations with self-transcendence (universalism and benevolence) and negative correlations with hedonism, stimulation (values that belong to the openness to change), and realization (this value belongs to self-promotion). With regard to age, and as the study by Knafo and Schwartz (2009) demonstrates, several studies carried out with populations from different countries all come to demonstrate that older people value values related to conservation and self-transcendence more. In turn, young people value more values of self-promotion and openness to change. In terms of gender, and with regard to second-order values, men prioritize values of self-promotion, opposite to the results in this study, where no differences were found in relation to gender in this value, and openness to change, consensual to the obtained results, while women value more values of self-transcendence, confirming the results of this study. However, in relation to conservation, the literature points out that among women and men, this value differs less, although the female gender, in contrast to the male gender, favors tradition and security a little more (Schwartz 2012).

Concerning H2 (it is expected that there are significant associations between religious variables and Schwartz’s values), it was found that religious identity, “How religious are you?”, correlates significantly and negatively with conformity, tradition, and conservation. These results mean that respondents who express more religiosity subscribe to higher values in conformity, tradition, and conservation. With reference to religious practice “How often do you attend religious services, in addition to special occasions?”, it correlates significantly and positively with conformity, tradition, and conservation. These results suggest that respondents who show less religious practice identify less with the values of conformity, tradition, and conservation. Schwartz and Huismans (1995) found that religiosity of individuals with Orthodox Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish religion, correlates positively with the values of tradition, conformity, and security, and negatively with values of power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, and self-direction. Other studies in this area, such as the one by Saroglou et al. (2004), showed that religiosity was highly associated with conservation values, and was little related to self-directed values, i.e., religious people tend to favor values that promote perseverance of the social and individual order (conformity, tradition, and, to a lesser extent, security), and on the other hand, they dislike values that promote openness to change.

In regard to H3 (it is expected that age, religious identity, and religious practice explain the second-order variables of Schwartz, i.e., conservation and openness to change), it was found that age, religious identity, and an item of religious practice, “How many times do you pray apart from religious cults?”, are those that significantly contribute to explaining 13.9% of the variance of the second-order conservation dimension. That is, being older, assuming a high religious identity, and praying outside religious cults explain the value of second-order conservation. It is also found that age and religious practice, “How often do you attend religious services, in addition to special occasions?”, are those that significantly contribute to explaining 12.2% of the variance of the second-order dimension openness to change, i.e., the openness to change is explained by a younger age and the low or no frequency of religious services. Saroglou et al. (2004) showed that religious people highly classify the values that promote self-transcendence and conservation. In turn, Pereira (2019) claim that the religious system correlates with second-order values of conservation. Schwartz (2012) found that the religiousness index of adolescents from the main Western religious groups, i.e., Roman Catholics, Protestants, Eastern Orthodox, Muslims, Jews, correlate positively with conservation values. In addition, a study by Saroglou and Muñoz-García (2008) found that the values explained 22% of the variance of religiosity and 12% of the variance of spirituality.

6. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to understand the contribution of religious variables to the explanation of Schwartz’s human values in a representative sample of the Portuguese population. Specific objectives included correlating the sample to religious and psychological variables (Schwartz’s values) and identifying an explanatory model of the second-order values of Schwartz (self-transcendence, conservation, self-promotion, and openness to change). Older and female participants were expected to present higher self-transcendence and conservation values than younger and male participants, which was confirmed. In turn, the latter were expected to present the highest order values self-promotion and openness to change, which was also confirmed.

It was also expected that there would be significant associations between religious variables and Schwartz’s values, which was partially confirmed, i.e., respondents who express more religiosity subscribe to higher values in conformity, tradition, and conservation and respondents who show less religious practice subscribe to lower values in conformity, tradition, and conservation. However, very low correlations were found between religious and self-transcendence variables and no significant correlations were found between religious and self-promotion variables. Finally, it was expected that age, religious identity, and religious practice would explain the second-order variables of Schwartz, i.e., conservation and openness to change, which was confirmed. Age contributed to explaining the variances of the two second-order variables; one item related to religious practice contributed to explain conservation and one item about religious practice and another item about religious identity contributed to explain openness to change.

In summary, these results seem to suggest some autonomy of human motivational values and second-order values in relation to religiosity (identity and practice). In fact, most Portuguese consider themselves to be a religious person, however, their religiosity seems to have little impact on their human values. This can be, in part, somewhat related with Grace Davie’s (1990) thesis, i.e., the traditional relationship between human values and religiosity is experiencing a transformation. However, this transformation does not mean that an evident secularization is happening. On the contrary, people believe without belonging, which is a result of a significant religious pluralism that is increasing all over the world and, particularly, in Europe. Alongside, these results agree with Oliver Roy’s (2014) thesis, advocating a pure religion and a separation between religion and culture. According to this author, since religion was not concerned with society, then there is no more a quest for synthesis or integration of religion and culture. In order to achieve a more comprehensive explanation, future research should further explore this relation between religiosity and human values using different religious questions, e.g., religious beliefs and representations, other than the religious identity and the religious practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C. and Â.L., data analysis, A.C. and Â.L. and writing, A.C., H.F.P.eS., M.A.P.D. and Â.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amado, Nuno, and António M. Diniz. 2017. Strength of Religious Faith in the Portuguese Catholic Elderly. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 39: 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, Rafaella de C. R., Magdalena Bobowik, Roosevelt Vilar, James H. Liu, Homero Gil de Zuñiga, Larissa Kus-Harbord, Nadezhda Lebedeva, and Valdiney V. Gouveia. 2020. Human values and ideological beliefs as predictors of attitudes toward immigrants across 20 countries: The country-level moderating role of threat. European Journal of Social Psychology 50: 534–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Montes, Antonio, Pilar Tirado-Valencia, and Vicente Fernández-Rodríguez. 2017. Human values and volunteering: A study on elderly people. Intangible Capital 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspelund, Anna, Marjaana Lindeman, and Markku Verkasalo. 2013. Political Conservatism and Left-Right Orientation in 28 Eastern and Western European Countries. Political Psychology 34: 409–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckford, James A. 2019. Religion and Advanced Industrial Society. London: Routledge, vol. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Bilsky, Wolfgang. 2009. A estrutura de valores: Sua estabilidade para além de instrumentos, teorias, idade e culturas [The structure of values: Its stability across instruments, theories, age, and cultures]. RAM, Revista de Administração Mackenzie 10: 12–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, Gian Vittorio, Michele Vecchione, Shalom H. Schwartz, Harald Schoen, Paul G. Bain, Jo Silvester, Jan Cieciuch, Vassilis Pavlopoulos, Gabriel Bianchi, Hasan Kirmanoglu, and et al. 2017. Basic Values, Ideological Self-Placement, and Voting: A Cross-Cultural Study. Cross-Cultural Research 51: 388–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Stephanie W. Y., Wilfred W. F. Lau, C. Harry Hui, Esther Y. Y. Lau, and Shu-fai Cheung. 2020. Causal relationship between religiosity and value priorities: Cross-sectional and longitudinal investigations. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 12: 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieciuch, Jan, and Shalom H. Schwartz. 2017. Values and the Human Being. In The Oxford Handbook of the Human Essence. Edited by Martijn van Zomeren and John F. Dovidio. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cieciuch, Jan, Eldad Davidov, and René Algesheimer. 2016. The Stability and Change of Value Structure and Priorities in Childhood: A Longitudinal Study. Social Development 25: 503–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidov, Eldad, Peter Schmidt, and Shalom H. Schwartz. 2008. Bringing Values Back In: The Adequacy of the European Social Survey to Measure Values in 20 Countries. Public Opinion Quarterly 72: 420–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davie, Grace. 1990. Believing without belonging: Is this the future of religion in Britain. Social Compass 37: 455–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devos, Thierry, Dario Spini, and Shalom H. Schwartz. 2002. Conflicts among human values and trust in institutions. British Journal of Social Psychology 41: 481–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, Emile. 1964. Essays on Sociology and Philosophy. New York: Harper & Row, vol. 1151. [Google Scholar]

- European Social Survey Round 8 Data. 2016. Data File Edition 2.1. NSD—Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Norway—Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC. Available online: https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/data/conditions_of_use.html (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Europeansocialsurvey.org. 2019. European Social Survey (ESS). Available online: https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/about/structure_and_governance.html (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Francescato, Donata, Minou E. Mebane, and Michele Vecchione. 2017. Gender differences in personal values of national and local Italian politicians, activists and voters. International Journal of Psychology 52: 406–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granjo, Manuel, and Francisco Peixoto. 2013. Contributo para o estudo da Escala de Valores Humanos de Schwartz em professores [Contribution to the study of the Schwartz Human Values Scale in teachers]. Laboratório de Psicologia 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heelas, Paul, Linda Woodhead, Benjamin Seel, Bronislaw Szerszynski, and Karin Tusting. 2005. The Spiritual Revolution: Why Religion is Giving Way to Spirituality. Oxford: Blackwell Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, Geert. 2001. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations. Sauzend Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ives, Christopher D., and Jeremy Kidwell. 2019. Religion and social values for sustainability. Sustainability Science 14: 1355–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khukhlaev, Oleg Y., Valeria A. Shorokhova, Elena A. Grishina, and Olga S. Pavlova. 2018. Values and Religious Identity of Russian Students from Different Religions. In Changing Values and Identities in the Post-Communist World. Cham: Springer, pp. 175–89. [Google Scholar]

- Knafo, Ariel, and Shalom H. Schwartz. 2009. Accounting for Parent–Child Value Congruence: Theoretical Considerations and Empirical Evidence. In Cultural Transmission. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 240–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kørup, Alex Kappel, Jens Søndergaard, René dePont Christensen, Connie Thurøe Nielsen, Giancarlo Lucchetti, Parameshwaran Ramakrishnan, Klaus Baumann, Eunmi Lee, Eckhard Frick, Arndt Büssing, and et al. 2020. Religious Values in Clinical Practice are Here to Stay. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 188–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Krishna. 1975. Multicollinearity in regression analysis. Review of Economics and Statistics 67: 365–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, Ângela, Ana Ramires, Maria Alzira Pimenta Dinis, and Hélder Fernando Pedrosa e Sousa. 2019. Who Is Concerned about Terrorist Attacks? A Religious Profile. Social Sciences 8: 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, Ângela, Diogo Guedes Vidal, Maria Alzira Pimenta Dinis, Hélder Fernando Pedrosa e Sousa, and Paulo Dias. 2020. The Relevance of God to Religious Believers and Non-Believers. Religions 11: 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönnqvist, Jan-Erik, Sointu Leikas, and Markku Verkasalo. 2018. Value change in men and women entering parenthood: New mothers’ value priorities shift towards Conservation values. Personality and Individual Differences 120: 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luria, Ela, and Yaacov J. Katz. 2019. Parent–child transmission of religious and secular values in Israel. Journal of Beliefs & Values 41: 458–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maio, Gregory R. 2016. The Psychology of Human Values. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Marôco, João. 2010. Análise de Equações Estruturais: Fundamentos Teóricos, Software & Aplicações [Structural Equation Analysis: Theoretical Foundations, Software & Applications]. Lisboa: ReportNumber, Lda. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl. 1964. Karl Marx: Early Writings. Penguin: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Musek, Janek. 2017. Values Related to the Religious Adherence. Psihologijske Teme 26: 451–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, Alexsandro Medeiros do, and Antonio Roazzi. 2017. Religiosidade e o desenvolvimento da autoconsciência em universitários [Religiosity and the development of self-awareness in university students]. Arquivos Brasileiros de Psicologia 69: 121–37. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, Alexsandro Medeiros do, Rafael Amorim de Paula, and Antonio Roazzi. 2017. Autoconsciência, religiosidade e depressão na formação presbiteral em seminaristas católicos: Um estudo ex-post-facto [Self-awareness, religiosity and depression in priestly formation in catholic seminarians: An ex-post-facto study]. Gerais, Revista Interinstitucional de Psicologia 10: 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Oman, Doug. 2018. Why Religion and Spirituality Matter for Public Health: Evidence, Implications, and Resources. Cham: Springer, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Pantaléon, Nathalie, Christine Chataigné, Christine Bonardi, and Thierry Long. 2019. Human values priorities: Effects of self-centredness and age. Journal of Beliefs & Values 40: 172–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastylianou, Dona, and Efthymios Lampridis. 2016. Social values priorities and orientation towards individualism and collectivism of Greek university students. Journal of Beliefs & Values 37: 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Inês Filipa Godinho Machado. 2019. É a Religiosidade Protetora da Ansiedade Face à Morte nos Adultos na Meia-Idade e nos Idosos? [It Is the Protective Religiosity of Anxiety in the Face of Death in Middle-Aged Adults and the Elderly?]. Évora: Universidade de Évora. [Google Scholar]

- Pestana, Maria Helena, and João Nunes Gageiro. 2014. Análise de Dados para Ciências Sociais: A Complementaridade do SPSS [Data Analysis for Social Sciences: The Complementarity of SPSS]. Lisboa: Edições Sílabo. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, José Luís Pais. 2007. Metodologia de Investigação em Psicologia e Saúde [Research Methodology in Psychology and Health]. Lisboa: Livpsic-Psicologia. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Oliver C., Karina Hanson, Guy Hayward, and David Lorimer. 2019. Age and Cultural Gender Equality as Moderators of the Gender Difference in the Importance of Religion and Spirituality: Comparing the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 58: 301–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccas, Sonia. 2005. Religion and Value Systems. Journal of Social Issues 61: 747–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokeach, Milton. 1973. The Nature of Human Values. Washington: Free press. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, Olivier. 2014. Holy Ignorance: When Religion and Culture Part Ways. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sagiv, Lilach, Sonia Roccas, Jan Cieciuch, and Shalom H. Schwartz. 2017. Personal values in human life. Nature Human Behaviour 1: 630–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, Walberto Silva dos, Valeschka Martins Guerra, Jorge Artur Peçanha de Miranda Coelho, Valdiney Veloso Gouveia, and Luana Elayne Cunha de Souza. 2012. A influência dos valores humanos no compromisso religioso [The influence of human values on religious commitment]. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa 28: 285–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, Vassilis, and Antonio Muñoz-García. 2008. Individual Differences in Religion and Spirituality: An Issue of Personality Traits and/or Values. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 47: 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, Vassilis, Vanessa Delpierre, and Rebecca Dernelle. 2004. Values and religiosity: A meta-analysis of studies using Schwartz’s model. Personality and Individual Differences 37: 721–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 1992. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 25: 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 2003. A proposal for measuring value orientations across nations. Questionnaire Package of the European Social Survey. pp. 259–319. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312444842_A_proposal_for_measuring_value_orientations_across_nations (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 2011. Studying Values: Personal Adventure, Future Directions. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 42: 307–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 2012. An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Psychology and Culture Article 11: 12–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Shalom H., and Anat Bardi. 2002. Influences of Adaptation to Communist Rule on Value Priorities in Eastern Europe. Political Psychology 18: 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Shalom H., and Sipke Huismans. 1995. Value Priorities and Religiosity in Four Western Religions. Social Psychology Quarterly 58: 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzebiatowska, Marta, and Steve Bruce. 2012. Why are Women More Religious than Men? Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trzebiatowska, Marta, and Steve Bruce. 2013. ‘It’s all for girls’: Re-visiting the gender gap in New Age spiritualities. Studia Religiologica 46: 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vala, Jorge, Anália Torres, and Alice Ramos. 2006. Inquérito Social Europeu–Resultados Globais [European Social Survey—Global Results]. Lisboa: Instituto de Ciências Sociais. [Google Scholar]

- Vala, Jorge, Anália Torres, Alice Ramos, and Susana Lavado. 2010. Inquérito Social Europeu–Resultados Globais Comparativos [European Social Survey—Overall Comparative Results]. Lisboa: Instituto de Ciências Sociais. [Google Scholar]

- Woodhead, Linda. 2017. The rise of ‘no religion’ in Britain: The emergence of a new cultural majority. In British Academy Lectures, 2015–16: British Academy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).