Work–Family Articulation Policies in Portugal and Gender Equality: Advances and Challenges

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Welfare State, Work–Family Articulation and Gender Equality: A Summary of the Theoretical Debate

3. Information Sources and Research Methods

4. Setting the Context: Women and Men in the Labour Market

5. The Evolution of Work–Family Articulation Policies in Portugal

6. The Political Process Underlying Policy Development (1976–2009)

6.1. Parliamentary Debates

I’m a father, but I find this article quite unfortunate and I’m afraid it may even be ridiculous (…). Article 68 should remain as it is, referring only to “motherhood”, highlighting a positive discrimination towards mothers (…). Not establishing any exclusiveness for mothers regarding education, which implicitly leaves the field open to the action of fathers, but nothing more than that (Plenary Meeting on 29/04/1982).

6.2. The Key Political Actors’ Views on the Core Legislative Changes and on the Major Policy Players

- Theme 1—State, equality and the work–family articulation,

- Theme 2—Fragilities/obstacles to equality and/or their articulation,

- Theme 3—Emblematic measures, and

- Theme 4—Political processes.

I think the attitude of the Portuguese State is fairly significant in regard to this issue and extraordinarily progressive, (…) when I arrived in Parliament (…) I had the opportunity to come into contact with my peers from many other European commissions and realised that Portugal was frankly quite advanced, especially when taking into consideration the fact that we are such a recent democracy.—AR17_W

I genuinely think that it has not been among the purposes of any Government, transversally, to give visibility to equality, or parity.—AR8_M

Perhaps at the turn of the 1980s to the 1990s, and especially in the 1990s, this issue began to enjoy greater visibility, and, in the first decade of this century, it has been a matter of some concern, if not identical to, at least in the same range as other concerns when we talk about social policies.—AR10_M

(…) it was not our accession to the EEC that led to changes in our internal legislation in this area. The legislation was already there: we did it before, and we did not change anything in the internal legislation in order to comply. We had everything, because the law was already there. The rules were already there, and, when we joined, we already had them.—ARC4_W

In most of these matters, the European Union has led the way. I think one of the fringe benefits of Portugal’s accession to the European Community, was that it forced us to think about these laws and to make an effort. But then this also fails if it is not genuine (…), I still don’t believe that Portugal is genuine.—AR19W

Portugal has merely met European demands and then only barely so, because the legal transpositions have always been deficient.—ARS14W

Pre-school measures were adopted to facilitate articulation, with great anger being displayed by some representatives of the Ministry of Education, who at the time thought that “this is a problem of education, it has nothing to do with women”. (…) These measures are less highly valued when they are linked to the sharing of responsibilities.—ARC_4W

(…) we all know that women have more difficulty reconciling work with family life, it is well documented, that women have more hours of unpaid work than men (…).—S2W

I heard the story of a woman who was asked in a job interview “Are you planning on getting married soon?”, and she really was about to get married. Her answer was “that’s part of my private life, but I promise you this, if I get married, I won’t get any dumber”. They found her funny and hired her, and then she got married a few months later. Now, these things keep happening.—C1_M

I usually say, in short, as an enforcer of the law, because I am a fully-fledged lawyer, that I don’t have so many complaints about the legislation, I have complaints about its effective application (…).—S5_M

I believe that the 2009 (parental) leave underlines the maturity of the evolution that has taken place in our leaves in terms of promoting reconciliation, and it also highlights a very balanced logic (…) that has to do with the rights of the mother and father, but also the child’s interest. (…)—AR11_M

It is a fundamental measure from the point of view of the principle of equal opportunities in education, but it is also a most valuable measure from the point of view of reconciliation, of course. And because it has become mandatory, it therefore also forces parents to learn a little about a certain organisation of the schooling, socialisation, learning, sociability, etc., of their children.—AR17_M

There is a father and there is a mother, there is no parent, and that discredits the participation of the father, and the mother, right? So, why do we have to be so concerned about parenthood? Parenthood at the level of the European Community is something completely different; it is an exceptional support in specific situations.—S18W

Now we have some new, modern things, which are the equality awards, the Gender Equality Action Plans (…), but these Plans, awards and other similar initiatives should be designed to give greater importance to actions that go beyond the simple requirements of the law. So, there’s no point in making a big fuss about Plans or prizes for fulfilling what’s in the law (…), are we rewarding what is a legal obligation?—S7W

Dr. Leonor Beleza served on the Equality Committee at the beginning, and she was the catalyst behind a significant change in the Civil Code. I will not say that she didn’t have, let’s say, a role in the first changes that occurred, which involved the establishment of the woman’s powers and responsibilities in the family relationship.—S5_M

(…) I think Maria do Céu (Cunha Rêgo) is a person to whom we owe a lot in terms of equality, but really a lot. She brought us equality and reconciliation. She exerted the most influence in the reform of the whole policy of equality and reconciliation. (…) All the legislation that came out at that time had her contribution (…). Firstly, as president of CITE, then, as Secretary of State, she was an absolutely exceptional person. (…) it was she who introduced the mandatory father’s leave (…).—C12_M

I have to say that I had many struggles with Guterres, but in one regard he was reliable, (…) he took these policies very seriously. And it was undoubtedly his Government that worked the most, because he wanted to make a difference, he wanted to leave that mark, which he personally valued very highly. And I know he did, I’ve said it several times.—ARS14_M

(…) the Socialist Party played an extremely important role in equality issues, even for the people who were there, the women that the party had, in fact, and for the policies they developed during the period they were in government. The majority of the equality legislation came from the PS.—C12_W

(…) I would say this is a subject that starts from the left of the PSD, I mean from the PSD with some contradictions, but with some very important protagonists, in various dimensions (…). I think that, in Portugal, it is difficult for the cause of gender equality (…) to be interpreted to the right of the PSD, which is the party where it is possible to find every position defended.—AR15_M

7. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aboim, Sofia. 2010. Género, família e mudança em Portugal. In A Vida Familiar no Masculino: Negociando Velhas e Novas Masculinidades. Coordinated by Karin Wall, Sofia Aboim and Vanessa Cunha. Lisboa: CITE, pp. 39–66. [Google Scholar]

- Addabbo, Tindara, Amélia Bastos, Sara Falcão Casaca, Nata Duvvury, and Áine Ní Léime. 2015. Gender and labour in times of austerity: Ireland, Italy and Portugal in a comparative perspective. International Labour Review 154: 449–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addis, Elisabetta. 2003. Unpaid and paid caring work in the reform of welfare states. In Unpaid Work and the Economy: A Gender Analysis of the Standards of Living. Edited by Antonela Picchio. London: Routledge, pp. 189–223. [Google Scholar]

- Arcanjo, Manuela. 2006. Ideal (and Real) Types of Welfare States (WP 15/2006/DE/CISEP). Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.5/2616 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Arcanjo, Manuela. 2011. Welfare state regimes and reforms: A classification of ten European countries between 1990 and 2006. Social Policy and Society 10: 139–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettio, Francesca, and Janneke Plantenga. 2004. Comparing Care Regimes in Europe. Feminist Economics 10: 85–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Casaca, Sara Falcão. 2012. Mercado do trabalho, flexibilidade e relações de género: Tendências recentes. In Mudanças Laborais e Relações de Género, Novos Vetores de Desigualdade. Coordinated by Sara Falcão Casaca. Lisboa: Fundação Económicas e Editora Almedina, pp. 9–50. [Google Scholar]

- Casaca, Sara Falcão, and Sónia Damião. 2011. Gender (in)equality in the labour market and the Southern European welfare states. In Gender and Well-Being: The Role of Institutions. Edited by Elisabetta Addis, Paloma de Villota, Florence Degavre and John Eriksen. London: Ashgate, pp. 183–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chaney, Paul. 2012. Critical Actors vs. Critical Mass: The Substantive Representation of Women in the Scottish Parliament. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 14: 441–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, Sara, and Mona Lena Krook. 2008. Critical mass theory and women’s political representation. Political Studies 56: 725–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CITE. 2019. Relatório Sobre o Progresso da Igualdade Entre Mulheres e Homens no Trabalho, no Emprego e na Formação Profissional; Lisboa: CITE. Available online: http://cite.gov.pt/pt/destaques/complementosDestqs2/Relatorio%202018%20Lei%2010.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Coelho, Lina, and Virgínia Ferreira. 2018. Segregação sexual do emprego em Portugal no último quarto de século—Agravamento ou abrandamento? e-cadernos CES 29: 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Correia, Rita B., and Vanessa Cunha. 2020. Observatório das Famílias e das Políticas de Família - Relatório 2018. Lisboa: Observatórios do Instituto de Ciências Sociais da Universidade de Lisboa, Available online: https://www.ics.ulisboa.pt/flipping/ofap2020/ (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Crompton, Rosemary, Suzan Lewis, and Clare Lyonette. 2007. Women, Men, Work and Family in Europe. London: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, Vanessa, and Susana Atalaia. 2019. The gender(ed) division of labour in Europe: Patterns of practices in 18 EU countries. Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas 90: 113–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, Vanessa, Susana Atalaia, and Karin Wall. 2017. Policy Brief II—Homens e Licenças Parentais: Legal Framework, Attitudes and Practices; Lisboa: ICS/CITE. Available online: http://cite.gov.pt/asstscite/images/papelhomens/Policy_Brief_II_Men_and_Parental_Leaves_Legal_framework.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Dahlerup, Drude. 1988. From a Small to a Large Minority: Women in Scandinavian Politics. Scandinavian Political Studies 11: 275–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, Anna, and Karin Wall. 2015. Leave Policies in Southern Europe: Continuities and changes. Community, Work & Family 18: 218–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta. 1999. Social Foundations of Postindustrial Economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. 2020. Labour Force Survey. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/lfs/data/database (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- Ferreira, Virgínia. 2014. Employment and Austerity: Changing welfare and gender regimes in Portugal. In Women and Austerity: The Economic Crisis and the Future for Gender Equality. Organised by Maria Karamessini and Jill J. Rubery. New York: Routledge, pp. 207–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera, Maurizio. 1996. The ‘southern’ model of welfare state in social Europe. Journal of European Social Policy 6: 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, Nancy. 1997. Justice Interruptus: Critical Reflections on the “Postsocialist” Condition. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- GEP/MTSSS. 2011. Carta Social—Rede de Serviços e Equipamentos 2010. Lisboa: GEP/MTSSS, Available online: http://www.cartasocial.pt/pdf/csocial2010.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- GEP/MTSSS. 2019. Carta Social—Rede de Serviços e Equipamentos 2018. Lisboa: GEP/MTSSS, Available online: http://www.cartasocial.pt/pdf/csocial2018.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- Gornick, Janet C., and Marcia K. Meyers. 2009. Gender Equality: Transforming Family Divisions of Labour. New York: Verso Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, Abigail, and Susan Milner. 2009. Editorial: Work–life Balance: A Matter of Choice? Gender, Work & Organization 16: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE. n.d. Inquérito Permanente ao Emprego; Lisboa: INE.

- Kamerman, Sheila B., and Peter Moss. 2009. The Politics of Parental Leave Policies: Children, Parenting, Gender and the Labour Market. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karamessini, Maria, and Jill J. Rubery. 2014. Women and Austerity: The Economic Crisis and the Future for Gender Equality. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Korpi, Walter. 2000. Faces of Inequality: Gender, Class, and Patterns of Inequalities in Different Types of Welfare States. Social Politics 7: 127–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krook, Mona Lena, and Fiona Mackay. 2011. Introduction: Gender, Politics, and Institutions. In Gender, Politics and Institutions—Toward a Feminist Institutionalism. Edited by Mona Lena Krook and Fiona Mackay. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Leitão, Mafalda, Rita Correia, Vanessa Cunha, and Liliane Moser. 2019. Observatório das Famílias e das Políticas de Família—Relatório 2016–2017. Lisboa: Observatórios do Instituto de Ciências Sociais da Universidade de Lisboa, Available online: https://www.ics.ulisboa.pt/flipping/ofap2019/ (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Lewis, Jane. 1992. Gender and the Development of Welfare Regimes. Journal of European Social Policy 2: 159–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Jane. 2002. Gender and Welfare State Change. European Societies 4: 331–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Suzan, and Cary L. Cooper. 2005. Work–Life Integration. Case Studies of Organisational Change. Chichester: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Jane, Mary Campbell, and Carmen Huerta. 2008. Patterns of Paid and Unpaid Work in Western Europe: Gender, Commodification, Preferences and the Implications for Policy. Journal of European Social Policy 18: 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, Henning, and Hannah Zagel. 2016. Family Policy in Comparative Perspective: The Concepts and Measurement of Familization and Defamilization. Journal of European Social Policy 26: 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marques, Susana Ramalho. 2017. Estado de bem-estar e igualdade de género: O desenvolvimento das políticas de articulação trabalho-família em Portugal no período 1976–2009. Ph.D. thesis, ISEG-Lisbon, Lisboa, Portugal. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.5/13432 (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- McLaughlin, Eithne, and Carolina Glendinning. 1994. Paying for care in Europe: Is there a feminist approach? In Cross-National Research Papers. Edited by Linda Hantrais and Steen Mangen. Leicestershire: European Research Centre, Loughborough University of Technology, European Research Centre, pp. 52–69. [Google Scholar]

- Metelo, Carina, Elisabete Mateus, João Gonçalves, José Miguel Nogueira, Maria Clara Guterres, and Rui Nicola. 2010. O Papel da Rede de Serviços e Equipamentos Sociais. Sociedade e Trabalho 41: 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, Rosa. 2010. Genealogia da lei da igualdade no trabalho e no emprego desde finais do Estado Novo. In A Igualdade de Mulheres e Homens no Trabalho e no Emprego em Portugal—Políticas e Circunstâncias. Organized by Virgínia Ferreira. Lisboa: CITE, pp. 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, Rosa, and Liliana Domingos. 2013. O sentido do direito à conciliação: Vida profissional, familiar e pessoal numa autarquia. Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas 73: 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, Julia S., Ann Shola Orloff, and Sheila Shaver. 1999. States, Markets, Families: Gender, Liberalism, and Social Policy in Australia, Canada, Great Britain and the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Orloff, Ann Shola. 1993. Gender and Social Rights of Citizenship: The Comparative Analysis of Gender Relations and Welfare States. American Sociological Review 58: 303–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orloff, Ann Shola. 2009. Gendering the comparative analysis of welfare states: An unfinished agenda. Sociological Theory 27: 317–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partido Social Democrata, and Centro Democrático Social-Partido Popular. 2002. Programa do XV Governo Constitucional. Lisboa: PSD e CDS/PP. [Google Scholar]

- Perista, Heloísa, and Margarida Chagas Lopes. 1999. A Licença de Paternidade: Um Direito Novo para a Promoção da Igualdade; Lisboa: DEPP/MTS.

- Perista, Heloísa, Ana Cardoso, Ana Brázia, Manuel Abrantes, and Pedro Perista. 2016. Os Usos do Tempo de Homens e de Mulheres em Portugal; Lisboa: CESIS and CITE. Available online: http://cite.gov.pt/asstscite/downloads/publics/INUT_livro_digital.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Ramalho, Maria do Rosário Palma. 2010. Direito do Trabalho, Parte II—Situações Laborais Individuais. Coimbra: Almedina. [Google Scholar]

- Rêgo, Maria do Céu da Cunha. 2007. A paridade como estratégia para a democracia. In Género, Diversidade e Cidadania. Coordinated by Fernanda Henriques. Lisboa: Edições Colibri/CIDEHUS-UE, pp. 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rêgo, Maria do Céu da Cunha. 2010. A construção da igualdade de homens e mulheres no trabalho e no emprego na lei portuguesa. In A Igualdade e Mulheres e Homens no Trabalho e no Emprego em Portugal: Políticas e Circunstâncias. Organized by Virgínia Ferreira. Lisboa: CITE, pp. 57–98. [Google Scholar]

- Rêgo, Maria do Céu da Cunha. 2012. Políticas de igualdade de género na União Europeia e em Portugal: Influências e incoerências. ex æquo 25: 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, Pedro Adão. 2002. O modelo de welfare da Europa do Sul: Reflexões sobre a utilidade do conceito. Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas 38: 25–59. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, Anália, Francisco Vieira da Silva, Teresa Líbano Monteiro, and Miguel Cabrita. 2005. Homens e Mulheres entre Família e Trabalho. Lisboa: CITE. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, Anália, Paula Campos Pinto, Dália Costa, Bernardo Coelho, Diana Maciel, Tânia Reigadinha, and Ellen Theodoro. 2018. Género e idades da vida: Educação, trabalho, família e condições de vida em Portugal e na Europa. Lisboa: FFMS, Available online: https://www.ffms.pt/FileDownload/b138c0a0-b31a-4ce9-a00d-d54a801a69a4/caderno-genero-e-idades-da-vida (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Wall, Karin. 2007. Leave policy models and the articulation of work and family in Europe: A comparative perspective. In International Review of Leave Policies and Related Research 2007. Edited by Peter Moss and Karin Wall. London: Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform, pp. 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, Karin. 2010. Os homens e a política de família. In A Vida Familiar no Masculino: Negociando Velhas e Novas Masculinidades. Edited by Karin Wall, Sofia Aboim and Vanessa Cunha. Lisboa: CITE, pp. 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, Karin, and Anna Escobedo. 2009. Portugal and Spain: Two pathways in Southern Europe. In The Politics of Parental Leave Policies. Edited by Sheila Kamerman and Peter Moss. Bristol: Policy Press, pp. 207–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, Karin, and Anna Escobedo. 2013. Parental Leave policies, gender equity and family well being in Europe: A comparative perspective. In Family Well-Being: European Perspectives. Edited by Almudena Moreno Mínguez. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 103–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, Karin, Sofia Aboim, and Mafalda Leitão. 2011. Observatório das Famílias e das Políticas de Família—Relatório 2010. Lisboa: Observatórios do Instituto de Ciências Sociais da Universidade de Lisboa, Available online: https://repositorio.ul.pt/bitstream/10451/20327/1/ICS_KWall_SAboim_MLeitao_ObservatorioFamilias_WORN.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Wall, Karin, Sofia Aboim, Mafalda Leitão, and Sofia Marinho. 2012. Observatório das Famílias e das Políticas de Família—Relatório 2011. Lisboa: Observatórios do Instituto de Ciências Sociais da Universidade de Lisboa. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, Karin, Susana Atalaia, Mafalda Leitão, and Sofia Marinho. 2013. Observatório das Famílias e das Políticas de Família—Relatório 2012. Lisboa: Observatórios do Instituto de Ciências Sociais da Universidade de Lisboa, Available online: https://repositorio.ul.pt/bitstream/10451/23188/1/ICS_KWall_SAtalaia_MLeitao_SMarinho_Observatorio_RN.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2020).

- Wall, Karin, Vanessa Cunha, Susana Atalaia, Leonor Rodrigues, Rita Correia, Sónia Vladimira Correia, and Rodrigo Rosa. 2016. Livro Branco—Homens e Igualdade de Género em Portugal; Lisboa: CITE. Available online: http://cite.gov.pt/asstscite/images/papelhomens/Livro_Branco_Homens_Igualdade_G.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2020).

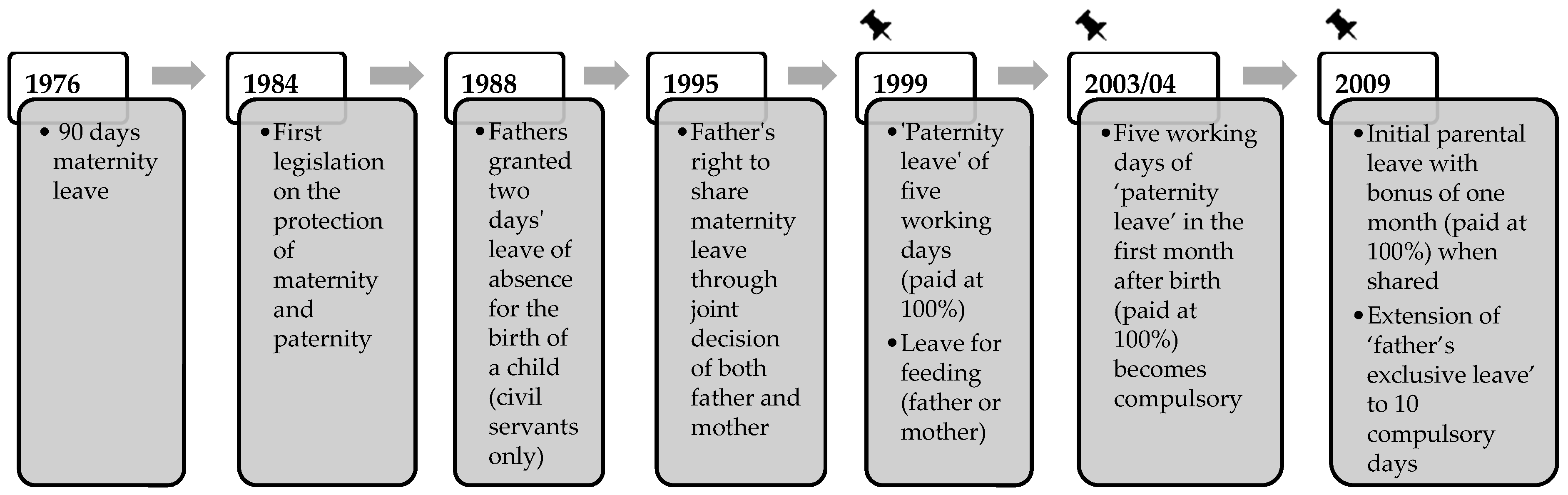

Major landmarks in leave policy developments in Portugal (Escobedo and Wall 2015).

Major landmarks in leave policy developments in Portugal (Escobedo and Wall 2015).

Major landmarks in leave policy developments in Portugal (Escobedo and Wall 2015).

Major landmarks in leave policy developments in Portugal (Escobedo and Wall 2015).

| Year | Type of Legislation/Policy | Contribution to Work–Family Articulation (Summarised) |

|---|---|---|

| 1976 | Constitutional Law | Principle of equality (Article 13) |

| Parental leave policies | 90 days of maternity leave (Decree-Law no. 112/76, of 7 February) | |

| 1979 | Social services and equipment | Equal opportunities and equal treatment of women and men in work and employment. Creation of Commission for Equality in Work and Employment—CITE (Decree-Law no. 392/79, of 20 September) |

| 1982 | Constitutional Law | Equivalence of paternity to maternity (1st Revision, Article 68) |

| 1984 | Parental leave policies | First legislation on the protection of maternity and paternity. (Law no. 4/84, of 5 April) |

| 1988 | Parental leave policies | Introduction of father’s two days’ leave of absence for birth (civil servants only) (Decree-Law no. 497/88, of 30 December) |

| 1995 | Parental leave policies | Increase in maternity leave to 98 days; introduction of father’s right to share maternity leave by joint decision of both father and mother (Law no. 17/95 of 9 June, amending Law no. 4/84, of 5 April) |

| 1997 | Constitutional Law | Right to organise work in order to enable work–family articulation (4th Revision, Article 59) |

| Parental leave policies | Introduction of a special subsidised leave (for father or mother) to assist handicapped or chronically ill child (Law no. 102/97, of 13 September (amending Law no. 4/84, of 5 April) | |

| Social services and equipment | Establishing the juridical framework for pre-school education (Law no. 5/97 of 10 February, [Framework Law for pre-school education]) | |

| 1998 | Parental leave policies | Increase in maternity leave to 120 days in year 2000 (Law no. 18/98 of 28 April, amending Law no. 4/84, of 5 April) |

| National Action Plans | Directive 17—Reconciling professional and family life (National Action Plan for Employment 1998) | |

| 1999 | Parental leave policies | Introduction of (optional) ‘paternity leave’ of five working days in the first month after birth (at 100%); introduction of leave for feeding—two hours per day (father or mother) (Law no. 142/99, of 31 August, amending Law no. 4/84, of 5 April) |

| 2003/04 | Parental leave policies | Five working days’ ‘paternity leave’ in the first month after birth (at 100%) becomes compulsory (Law no. 99/2003 of 27 August and Law no. 25/2004, of 29 July [CT and respective regulations]) |

| National Action Plans | Sector area 1 with the subfield of “Reconciliation of professional with family and personal life” (National Action Plan for Employment 2003–2006) | |

| 2004 | Constitutional Law | Attributing responsibility to the State for promoting work–family articulation through sectoral policies (6th Revision, Article 67) |

| 2006 | Social services and equipment | Launch of PARES (Order no. 426/2006, of 2 May) |

| 2007 | National Action Plans | Area 2 (subfield)—Reconciling professional, family and personal life (National Action Plan for Employment 2007–2010) |

| 2009 | Parental leave policies | Introduction of “initial parental leave with bonus” of one month (paid at 100%) when parents share the leave. Extension of ‘father’s exclusive leave’ to 10 compulsory days (Law no. 7/2009, of 12 February [revision of CT] and Decree-Law no. 91/2009, of 9 April) |

| 2015 | Parental leave policies | Extension of ‘father’s exclusive leave’ to 15 compulsory days; introduction of the possibility for both parents to take initial parental leave at the same time, for up to 15 days, between the fourth and fifth month (Law no.120/2015, of 1 September [revision of CT]) |

| 2019 | Parental leave policies | Extension of ‘father’s exclusive leave’ to 20 compulsory days (Law no.90/2019, of 4 September [revision of CT]) |

| Party/Body | n | Sex | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | ||

| Socialist Party (PS) | 9 | 7 | 2 |

| Portuguese Communist Party (PCP) | 2 | 2 | - |

| Social Democratic Party (PSD) | 2 | 2 | - |

| Trade Union Confederation (UGT) | 3 | 3 | - |

| National Trade Union Confederation (CGTP-IN) | 3 | 3 | - |

| Commission for the Female Condition/Commission for Equality and the Rights of Women/Commission for Citizenship and Gender Equality (CCF/CIDM/CIG) | 3 | 3 | - |

| Commission for Equality in Work and Employment (CITE) | 3 | 3 | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marques, S.R.; Casaca, S.F.; Arcanjo, M. Work–Family Articulation Policies in Portugal and Gender Equality: Advances and Challenges. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10040119

Marques SR, Casaca SF, Arcanjo M. Work–Family Articulation Policies in Portugal and Gender Equality: Advances and Challenges. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(4):119. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10040119

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarques, Susana Ramalho, Sara Falcão Casaca, and Manuela Arcanjo. 2021. "Work–Family Articulation Policies in Portugal and Gender Equality: Advances and Challenges" Social Sciences 10, no. 4: 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10040119

APA StyleMarques, S. R., Casaca, S. F., & Arcanjo, M. (2021). Work–Family Articulation Policies in Portugal and Gender Equality: Advances and Challenges. Social Sciences, 10(4), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10040119