1. Background

A child is defined by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) as every human being who is below the age of 18. Additionally, almost all countries around the world have signed up to this convention in recognition of child rights. The UNCRC (1989) can be said to safeguard the rights of all children, including unaccompanied minors (UAMs), particularly in relation to Article 2 on non-discrimination. Arguably, therefore, such protection is broadly encompassed in mainstream public policy for all children and therefore applicable to UAMs in those country contexts. However, it would appear that in dealing with the protection needs of UAMs, European governments face the challenge of how to comply with their international and humanitarian obligations at a time when their overall concerns have shifted towards tougher immigration policies and stricter border control to curb unauthorised immigration (

Drammeh 2010;

Parusel 2017;

Todaro and Romano 2019;

Chase and Allsopp 2020). Although the processes of integration and mobility remain key challenges for nation-states, increasingly, we are witnessing the contradictions between liberal democratic espousals of freedom and equality and the reality of exclusionary immigration policies (

Bauder 2003;

Gill et al. 2013).

Children make up less than one-third of the global population, but according to the United Nations High Commissioner for refugees, they comprise half of all refugees (

UNHCR 2017). In 2019, there were a total of 672,935 new asylum seekers in Europe. Of these, one-third (202,945) were children (

UNHCR 2019). It is estimated that 42,500 migrant children were present in Greece as of December 31, 2019, up from 27,000 in December 2018. In Italy, on the other hand, there were a total of 6054 migrant children registered in different types of accommodation at the end of December 2019. This represents a 44% decrease compared to December 2018. This is said to be largely as a result of a decrease in sea arrivals, as well as adolescents reaching adulthood. Overall, however, since 2016, both Greece and Italy now serve not just as short-term transit countries, but as long-term host countries that seek to provide a range of services and support to UAMs (

Pechtelidis 2020).

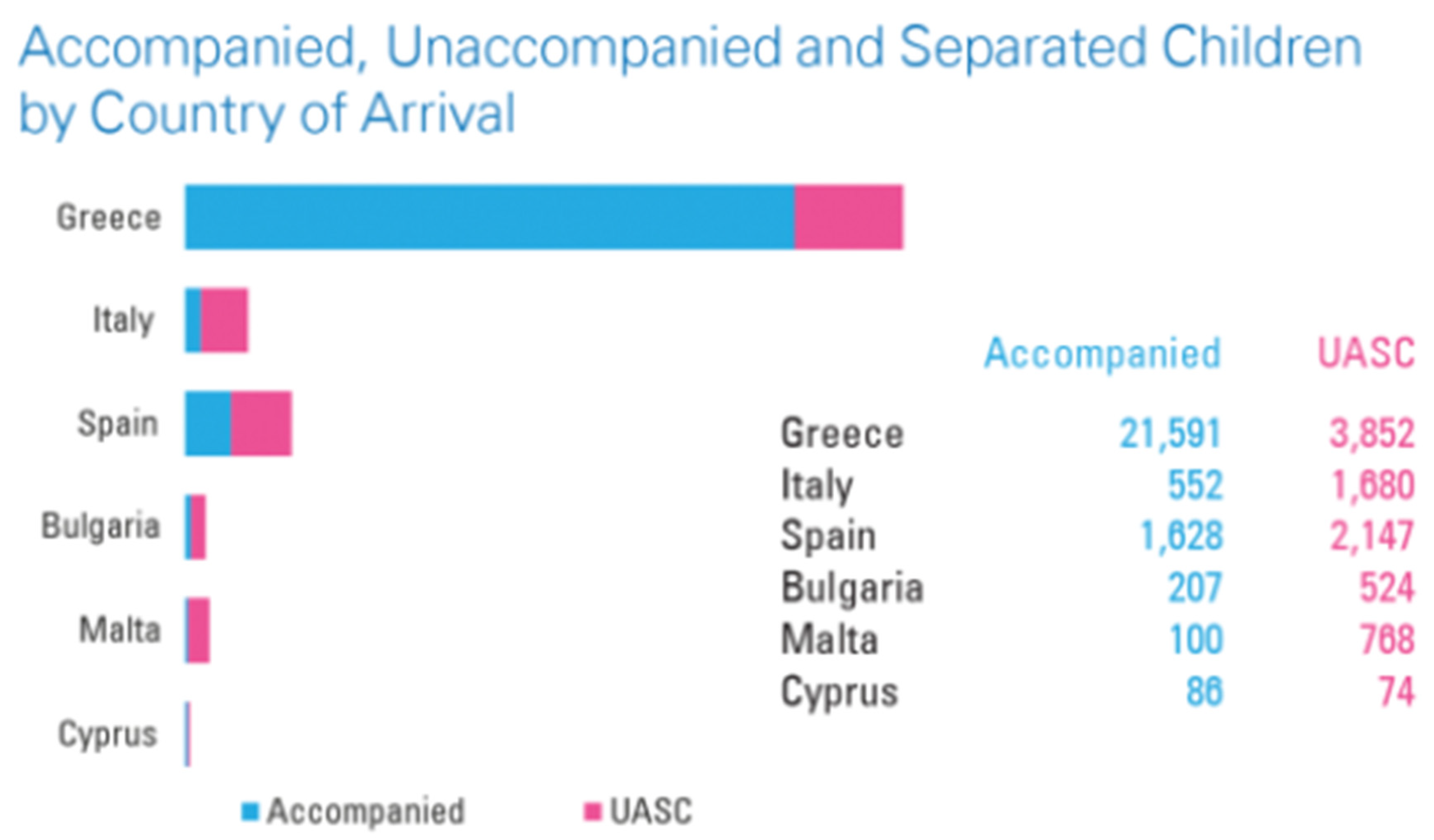

Figure 1 shows the number of accompanied, and unaccompanied and separated children by country of arrival between January and December 2019 (Source:

UNHCR 2019).

As shown in

Figure 1, the distribution of UAMs between the EU nations has been uneven. For instance, unlike in Greece, in Italy, most migrant children are UAMs. Moreover, it has been suggested that for every UAM who applies for asylum, there are many who do not submit such an application. For instance, in Italy and Spain together, the number of unaccompanied children who did not apply for asylum is said to have exceeded 10,000 in 2013 (

European Union 2014). The decline in the number of UAM applications for asylum could be attributed to a number of factors, including disillusionment with the process, wishing to continue with their onward journey, and forging ways to exist outside of the formal system and processes. Understandably, legal status and its association with access to provision have important implications for social work practice.

The plight of migrant children fleeing to the West has become an important subject for scholar activist research (

Hale 2008;

Chase and Allsopp 2020). Researchers have focused on a range of issues and concerns, including experiences of liminality, risk and insecurity, mental health, and family reunions (

Kohli 2011;

Chase 2013;

Allsopp et al. 2014). One of the key areas of concern remains that these children are falling between the gaps in national protection systems (

Feijen 2008), leading to an intensification of precarity. The notion of precarity is becoming increasingly common in discussions of UAMs. It generally refers to suggestions of a context of uncertainty, exploitation, restriction, and a status that is impermanent (

Chacko and Price 2020). Elsewhere,

Chase (

2016) has argued that it is with the UAM’s imminent transition to adulthood that precarity becomes particularly heightened through exposure to risk and adversity. Furthermore,

Chase (

2020, p. 440) invokes a Butlerian perspective to indicate the harmful effects of “politically-induced precariousness” which results in “real or symbolic violence” and a failure to afford adequate protections.

Arguably, the Kafkaesque nature of immigration laws which is causing much confusion, to the detriment of the well-being of UAMs, can be said to be at the heart of precarity. Jacqueline

Bhabha (

2014), an expert in international law, migration, and children’s rights, has identified the tensions which exist between asylum advocacy and human rights in a context where migration from the Global South is “viewed with heightened suspicion and hostility”. Nation-states invoke notions of citizenship to argue that these children are not of their concern. They point to the illegal methods used by these children and their parents and guardians to reach European countries. Indeed, the so-called “illegality” or “irregularity” can indeed be a response to restrictive immigration controls, and a process and/or migration strategy, rather than a defined “end-state” (

Jordan and Düvell 2002;

Bloch and Chimienti 2011).

2. Legal Obligations in the EU towards Unaccompanied Minors

Migration into and within European states is regulated by a combination of domestic, European, and international laws and/or conventions and agreements including the 1951 Refugee Convention, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989, Schengen Agreement, Amsterdam Treaty, Dublin Convention, and European Union’s Common European Asylum System (CEAS). Crucially, there are legal obligations on nation-states to safeguard the best interests of all UAMs.

Significantly, all EU states are signatories to the UNCRC 1989. Key affordances under the UNCRC 1989 therefore include non-discrimination, family reunification, protection from harm, and exploitation. Evidence suggests that children in migration are continuously exposed to risks such as violence (including in reception/transit centres), physical abuse, exploitation, sexual abuse, and trafficking for the purpose of sexual or other exploitation, and going missing or becoming separated from their families (

European Commission 2019). Children arrive in Europe with obvious signs of injury, trauma, and physical, sexual, and psychological abuse incurred on their journey to and in Europe. Arguably, and too often, their arrival on EU territory does not put an end to their problems because, even within the Member States, national standards and practices are not sufficient to ensure their rights and sometimes even contravene their protection needs. Without the principle of the “best interests of the child” really being taken into account, although this principle is guaranteed by the International Convention on the Rights of the Child (ICRD) and the Charter of Fundamental Rights (Article 24) and should take precedence over them being nationals of a third country, the experiences of UAMs in terms of age assessment procedures, reception conditions, the processing of files, and the formalities they have to face, vary from one Member State to another. For example, the return of unaccompanied and separated children should only be considered after it has been established in a full and fair procedure in line with international law that no international protection needs exist. The 1997 EU resolution on unaccompanied minors who are nationals of third countries outlines some important principles in regard to the return of separated children. In particular, it states that a child must not be returned when the return would be contrary to the 1951 Refugee Convention, the ECHR, the Convention against Torture, or the Convention on the Rights of the Child. It also states the important principle that a child may only be returned if adequate reception and care is available. There is increasing research evidence to show that nation states are becoming increasingly hostile towards so-called illegal and/or economic migrants including UAMs. As mentioned above, key concerns are highlighted by studies focus on issues around the detention of UAMs, family separation, trauma and mental health needs, belonging, agency and resilience (

Kohli 2011;

Chase 2013;

Allsopp et al. 2014;

Rania et al. 2018).

Schumacher et al. (

2019, p. 4) report that “even though detention of migrant children is considered to contradict the best interests of the child principle, it is still applied in a number of EU Member States”. With growing unease about immigration and a framework of nativist populism, the ever-changing immigration laws and neo-liberal policies are said to be resulting in widespread confusion and paralysis among policymakers and practitioners, to the detriment of UAMs (

Bhabha 2002,

2014,

2019;

Hammarberg 2010;

Humphris and Sigona 2019).

The reception system in force both in Italy and in Greece, is not always adapted to the specific needs of UAMs. Numerous reports attest to the irregular and critical conditions that characterise the reception of minors (

AGIA 2020;

Save the Children 2020;

Borderline Sicilia 2020;

Di Rosa et al. 2019;

Segatto et al. 2018). Crucially, the COVID-19 pandemic has intervened in this already precarious situation, generating a further reduction in the possibilities of minors to access rights and integration paths.

By drawing on some relevant literature, organisational reports and on field observations, in the sections below, we sketch out the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the context of the reception systems for UAMs in Italy and Greece, through an analysis of existing criticalities and of measures adopted as the social work response to UAMs during this COVID-19 health crisis.

3. Unaccompanied Minors in Italy

The COVID-19 pandemic is having a huge impact on everyone’s life, but even more so on the population that is already in conditions of precarity. Among the most vulnerable are UAMs whose rights are severely threatened by the pandemic. They have been deeply impacted by the emergency wave that, like a tsunami, has swept away the guarantees that the law reserves for them and the very fragile balance built in the territories over very long periods.

In Italy, on December 31, 2020, there were 7080 unaccompanied foreign minors in Italy. As of December 31, 2020, UAMs present in Italian reception system were mainly from Bangladesh (1558 minors), Tunisia (1084), Albania (972), Egypt (696) and Pakistan (574). The other most represented citizenships were Somali (309), Ivorian (244), Guinean (242), Afghan (178) and Kosovar (163) (

Ministry of Labour 2021). It is possible to observe critical points in the procedures, both with respect to minors already present in Italy and those who had just arrived.

In the case of newcomers, the procedure established during the pandemic has been to confine them in emergency structures for a quarantine period. In these facilities, separation between minors and adults was not guaranteed, and the length of stay often extended well beyond the period prescribed by health protocols. Additionally, these facilities are often not suitable for this type of prophylaxis and their overcrowding does not allow sanitary isolation to be properly observed. The climate inside these facilities has been, and at the time of writing, characterised by strong tensions that also lead to protests, expulsions, and interventions by the police responsible for guarding the facilities (

Borderline Sicilia 2020).

The critical issues identified in recent months also concern daily life in the centres for UAMs, where the precarious balance has been completely upset: administrative procedures and processes of social and labour insertion have been interrupted, and in many cases, completely stopped, schooling has been cancelled, and there have been sudden transfers and consequent uprooting.

In particular, the Italian Council for Refugees (

CIR 2020) note that:

The closure of schools has led to a suspension of integration paths for UAMs, such as training internships or preparation to the start of work paths—for which it was not possible to develop recovery methods, with a strong impact on children close to the age of 18;

The suspension of the activities of the Immigration Offices and the Territorial Commissions for the Recognition of Refugee Status have greatly affected access to the asylum procedure and the recognition of refugee status, especially in the case of minors who have come of age in the meantime;

Several Juvenile Courts have suspended the visits of third parties to the reception facilities, such as guardians and social workers, and suspended hearings for minors;

The suspension of family reunification procedures and the blocking of transfers have further extended a time frame made up of months of gruelling waiting, causing the voluntary removal of minors from the facilities in many cases.

3.1. Critical Issues in the Reception System during the Pandemic

Reception management in times of coronavirus has been affected by the climate of general disorientation that has been registered throughout the country, further aggravating a sector afflicted by a chronic lack of planning (

Di Rosa et al. 2019). The reception system in force in Italy is not always adapted to the specific needs of UAM Numerous reports and monitors attest to the irregular and critical conditions that characterise the reception of minors (

Save the Children 2020;

Borderline Sicilia 2020;

Di Rosa et al. 2019;

Segatto et al. 2018). The management of life inside the centres during the lockdown was extremely complicated: in many structures, confinement was carried out without the constant presence of operators, in the absence of clear explanations on what was happening, and on the measures adopted and to be adopted, generating discomfort among the minors. Finally, another finding concerns the difficulties that young people coming out of the centres encountered in their housing and socio-occupational integration (

Argento 2019).

Beyond the quarantine measures for migrants arriving by sea, put in place since February 2020, both the small facilities (hosting minors, both Italian and foreigners) and the SIPROIMI (Sistema di protezione per titolari di protezione internazionale e minori stranieri non accompagnati; reception centres dedicated to migrant minors), have not received univocal and specific directives on the management of the COVID-19 emergency. Additionally, in some centres, there is insufficient availability of personal protective equipment (PPE) such as face coverings, disposable gloves, and hand sanitiser to help prevent the spread of the COVID-19 virus (

INMP 2020). Some essential services for the protection of UAMs—such as cognitive interviews with qualified personnel, the appointment of a guardian and legal information—have been suspended in the absence of shared standards and in compliance with social distancing measures (

Pattaro 2018).

In the host facilities, the lockdown of the first wave lasted one month longer, a choice dictated by prudence. Irregular lessons limited social relationships, and suspended leisure activities have created discomfort and suffering for children of all nationalities (

Argento 2019). Staying closed for a long time has made post-traumatic disturbance phenomena re-emerge. Many, with due differences, have re-lived the trauma of Libyan imprisonment. The existential uncertainty has caused behavioural alterations and even psychosomatic reactions. The testimonies of many operators reported a marked increase in tensions within the structures, which involved minors who were often already exposed to highly traumatic situations (

Sanfelici et al. 2020).

With the second wave, the infections arrived, a new experience for which minors were unprepared. Some did not accept quarantine or transfer to COVID hotels because they were asymptomatic and did not accept that positivity is a danger. There were those who responded with denial, not accepting the result of the swab. Arguably, such suspicion and paranoia are also the results of past histories of violence and distrust of institutions. Restrictions on access to public services and to the offices in charge of carrying out reception procedures greatly penalises the process of integrating minors, making it very difficult for them to access their rights. In particular, these closures and delays are very risky for minors who are close to reaching 18 years of age, who risk not receiving proper protection in time (

AGIA 2020).

3.2. Guardianship

Three years ago, thanks to the approval of law 47/2017, the figure of the voluntary guardian was established as the legal representative and spokesperson for a UAM. Before that, their legal representation (mandatory for their status of minors) was entrusted to lawyers or local social workers, on which, however, an excessive number of protections accumulated, making their role only formal and preventing the creation and maintenance of a direct relationship between legal guardian and minor.

After the law of April 7, 2017, n. 47, guardianship embodies a new idea of legal protection, an expression of social parenting and active citizenship, as a tutor who offers not only legal representation but also relationship with the protected, listening to needs and problems, and offers support for their life project (

AGIA 2017). Voluntary guardians are private citizens willing to exercise the legal representation of a foreign minor who arrived in Italy without reference adults. Between 2017 and the end of 2019, there were over 3000 trained tutors, 450 in Sicily alone, the region that up to 2019 hosted about 40% of unaccompanied foreign minors in Italy.

The extraordinary conditions linked to the pandemic have severely limited the potential of this figure of the guardian. Primarily, because it has become difficult for guardians to meet the children outside the structures to listen to them without conditions. Although the Legislative Decree 18/2020 has provided that it must be ensured that the voluntary guardians are appointed, that they can take an oath (also through remote hearing methods, such as provided by the protocol proposed by the National Bar Council), and that they can get in touch with the minors hosted in facilities; it would seem that contacts with guardians during the pandemic were a very critical point due to the difficulty linked to the risk of contagion. The overcrowding of the centres, the impossibility for minors to go out to meet the guardians, and the impossibility of the guardians to go into the facility did not allow direct meetings in conditions of privacy. Secondly, some courts during the health emergency preferred to appoint lawyers with which they had greater speed and frequency of contact, instead of voluntary guardians external to the legal system and therefore more difficult to involve with security measures. This is leading to a return to a situation in which some lawyers have many active guardianships, while the guardians who are private citizens (regularly trained and in the list of the competent Juvenile Court) remain without active protections. This is to the disadvantage of the protected minor who would benefit from the one-to-one relationship that could more easily guarantee them a guardian who has no other protections in progress (

Save the Children 2020).

3.3. Implication for Social Work Intervention

In the emergency phase, social workers found themselves completely reviewing their relationship with users and interactions with colleagues. For example, with remote communication, full understanding can be less effective for the reception of migrants, and there are often cases of poor knowledge of Italian on the part of UAMs. For social workers, the challenges of remote working have become evident, which are leading to not just a physical distance but also emotional and social distance, resulting in feelings of abandonment on the part of UAMs. In the communities, social workers have become health advisors in raising awareness about the pandemic and in providing hygiene and sanitation guidelines. In addition, during this period, the operators have supported the minors in carrying out their school activities at a distance, sometimes trying to invent ad hoc solutions to remedy both the lack of adequate devices available to minors within the care facilities and the difficulties that low-schooled children have in following distance learning in a language that is foreign to them. Minors also suffer because the impossibility to go out, not even for their training activities, increases their anxiety about the future. These conditions of hardship and frustration increase workload and also affect the psycho-physical state not only of the children but also of the operators.

3.3.1. Family Reunions

Family reunification of UAMs with their adult family members present in other European countries raises serious concern, pursuant to Article 8 of the Dublin Regulation, which must take place within strict time limits. In a context such as the current one, these terms cannot, in any way, be complied with, both due to the overall slowdown of the asylum system and the impossibility of preparing the substantial documentation required to support this request. The preparation of this documentation requires a whole series of activities (including legal and social interviews, carried out by different professional figures), which cannot be carried out due to the measures related to the COVID-19 emergency. The absence of a suspension of time limits (for both initiation and transfer after notification which should be agreed between the different Dublin Units of the member countries) risks undermining a fundamental right, such as that of the family unit, as family reunification applications are severely impacted. The suspension of reunification practices can have an extremely negative impact on UAMs. Added to the measures of social isolation and containment of COVID 19, there is the risk of a serious psychological impact on UAMs.

3.3.2. Legal Status

For young people, the most difficult moments are administrative gaps. They await the arrival of an identity card and residence permit, essential tools for inclusion. Waiting for a positive opinion from the Foreign Minors Committee, if procedures are interrupted or suspended, as has happened in the health emergency, the psychological impact is strong. Particularly critical is the position of those minors who had presented an application for international protection which was rejected by the Territorial Commission when they came of age or after the age of eighteen (

ASGI 2020). One aspect that is worrying from the point of view of protection is that UAMs may not be guaranteed priority examination of asylum applications, despite the obvious vulnerability of the category. The formalisations of applications for international protection, although not suspended by the various Legislative Decrees, are in fact frozen at this time. When the applicant for protection is close to or after the age of 18, the suspension of the activities of the Territorial Commissions due to the COVID-19 emergency can dramatically reduce the chances of legality and integration.

3.3.3. Health Rights

Before 2017, UAMs had limited rights to access health services. Following the passing of Article 14, paragraph 1 of Law 47/17, registration of all UAMs became obligatory in the national health system (SSN), irrespective of their legal status. Registration with the NHS (National Health System) for UAMs may be requested “by the operator, even temporarily, with parental responsibility or by the person in charge of the first reception facility” (Article 14, paragraph 1 of Law 4717). This made the intervention of the social worker even more indispensable in this period of the COVID-19 emergency where longer times are recorded in the appointment of guardians. Given the complexity of the bureaucracy, minors awaiting the issue of a first residence permit may experience delay in obtaining their health card. This could result in only a partial access to healthcare, which could be detrimental to their health during this pandemic.

3.3.4. School Placement, Language Learning and Job Placement

The COVID-19 pandemic has abruptly interrupted training and language courses. It is taking longer to obtain the documents and enrol in Italian language lessons and frequent courses available in the Provincial Adult Education Centers (CPIA) of the Ministry of Education (

Di Rosa et al. 2019). Moreover, the lessons are not in-person but online, at least in most of the territories. Whilst the school can make some provision through distance learning, the same is not possible for training internships or those preparing to begin work paths (

Santagati and Colussi 2020). An important fact of reality must also be emphasised: online or distance learning, in its practical application, clashes with the digital devices actually available in the facilities and they are not within the reach of minors (

Pavesi and Valtolina 2020). This situation considerably delays the consolidation of their path of integration into the territory. For example, to be able to have long-term residence permits and to start work it is necessary to obtain a lower secondary school certificate. The health emergency has caused the abrupt interruption of the inclusion paths of unaccompanied foreign minors and new adults, because it is in fact impossible to guarantee the continuation of work placements (

Argento 2019), as well as professional training (generally conducted in restaurants, hotels, bars, and the tourism sector). Guardians and operators who follow unaccompanied minors are concerned about the consequences that the interruption of school, vocational training, and internships caused by the COVID-19 emergency may entail with respect to the conversion of the residence permit at the age of 18, and in general to the path of inclusion of the minors they are following.

4. Unaccompanied Minors in Greece

Greece continues to be one of the main routes into Europe for people fleeing conflict and poverty in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. The vast majority arrive on Aegean islands from the Turkish shores. Following a brief reference to current migration policy, this section sums up the situation of unaccompanied children and minors separated from their family, and outlines the responses and involvement of social workers to key needs, under the current conditions of resource constraints and the restrictive measures following the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Notably, resource constraints, as a result of the 2009 socio-economic crisis and its aftermath, the 2015–2016 refugee crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic need to be taken into consideration together to understand how the policies and practices surrounding UAMs in Greece have been shaped. The principal areas impacting UAMs during the pandemic include their daily life in the accommodation settings, processes of family reunion/relocation, guardianship, and schooling.

As of January 15, 2021, 24,000 migrant and refugee children and 4028 unaccompanied minors were residing in the country. The vast majority were boys (92.5%) between the ages of 14–18 (92%); mainly from Afghanistan (38%), Pakistan (22%) and Syria (13%). The rest mostly came from African countries such as Somalia and Eritrea (

NCSS 2021). However, Greece is not their desired destination; most UAMs aim to reach central and northern Europe. Thus, many UAMs avoid the initial registration procedures, hoping to find a non-conventional way to continue their trip.

Age assessment is approached in an interdisciplinary fashion, allowing the medical determination of age (dental, upper limb X-ray) only as a last resort. Assessment is primarily based on macroscopic features and an examination from a paediatrician, followed by a psychological and social assessment evaluating the person’s development in case the paediatrician cannot come to a safe conclusion (

Sarantou and Theodoropoulou 2019, p. 22). As in Italy and other countries such as Finland, Hungary, Malta, and Spain, UAM applications for asylum are prioritised and examined in a shorter time than those of adults (

France Terre d’Asile 2019, p. 10).

Since July 2019, the conservative government of Nea Dimokratia has developed a tough anti-immigration stance, which includes strategic targets for strict border surveillance, and discouraging arrivals. Significantly, the police affirm their role in seeking to prevent entry at the Evros land border, pushbacks, and the forced return of new arrivals from Turkish land and sea borders assisted by the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, also known as Frontex (

Léonard and Kaunert 2020). With authorisation and funding from the EU, the government enforced the land borders, continued the operation of the Close Reception and Identification Centres on the islands where all migrants who arrive there are detained, including UAMs over 15 years old, and closed the Open Accommodation Centers for the most vulnerable (disabled, pregnant women, elderly) in Leros and Lesvos (

Ministry of Migration and Asylum 2021). In 2020, the National Centre of Social Solidarity (NCSS), a statutory service responsible for social care, child protection and crisis intervention, ceased its operations for the protection of UAMs. This responsibility was transferred to the new Special Secretariat for the Protection of UAMs of the Ministry of Immigration that has little or no know-how on child protection (

Ministry of Migration and Asylum 2019).

Importantly, in a victory for children rights, the so-called protective custody, the horrific long-standing practice of detaining newly arrived UAMs in police stations across the country, sometimes for months with unrelated adults, has now been abolished by law (L.4760/11.12.2020). This practice had been widely condemned by human rights groups and social workers, and had also led to judgments against Greece by the European Court of Human Rights. The sense of relief was expressed by one of the social workers who worked in one of these inhumane environments: “I feel like I have been released from prison, myself!” (

Kallinikaki forthcoming).

4.1. Implications for Social Work Practice

Although children in Greece are protected explicitly by the Greek Constitution, the UNCRC’s 1989 Convention, and the EU directives, the lack of a national comprehensive child and family policy framework and foster care initiatives are evident in relation to UAMs (

Kallinikaki 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the fragmented and incoherent context for the UAMs residing in, or crossing, Greece (

Buchanan and Kallinikaki 2018).

Therefore, what is leading to a fragmented and incoherent framework of policy and practice? Essentially, there are two areas of concern. Firstly, the limitations and deficits of national and European migration policies and their implementation has prolonged or postponed legal relocations due to the closed borders of many EU countries (

Sandermann et al. 2017;

Sarantou and Theodoropoulou 2019). Secondly, the absence of a coherent framework for the establishment and operation of NGOs and services with a primary focus on UAMs results in short-term, partial targets and fragmented interventions of numerous NGOs, local authorities, municipalities and civil society activists (

Fili and Xythali 2018).

Social work practice attempts, in a variety of ways, to ensure appropriate settlement for the asylum-seeking children including the provision of a safe, supportive place to live, continuities with past relationships, customs and cultures, and opportunities to create new ones, access to purposeful education and training opportunities to move forward from troubling experiences, re-centre their lives, and find new purpose in everyday routines and activities (

Wade et al. 2005). Many social workers struggle for the improvement of inconsistent, untimely, discordant services, disproportionate with the real needs for safe accommodation and quick handling of cases regarding international protection (

Oikonomou 2020).

During the last five years, research on the strengths, limitations, and facilitators of social work practice with UAMs has grown in Greece. It has given voice to the professionals and to UAMs who cross and reside in Greece (

Theocharidou 2016;

Sarantou and Theodoropoulou 2019;

Oikonomou 2020). Firstly, social workers underlay the importance of being the person of reference for children living in a shelter, semi-independent living (SIL) accommodation, or safe zones in camps, listen to them (“How was your day?”), create trust bonds, and become familiar with their history, needs, interests, and priorities. Additionally, they inform them about basic rules and responsibilities in the place where they live, support them to start a new life, to be creative, to express wishes, reinforce the creation of networks in the school, the neighbourhood, and the community, ensure their regular access to online contact with separated parents, and conduct best interests assessments in relation to, and facilitate, reunification. Secondly, the UAMs can complain about the precarious conditions in entry points, the complex bureaucracy, and the uncertainty about the continuity of their trip, while they express hope and gratitude for the care and support they receive (ibid).

UAMs can leave the country legally only through relocation procedures, family reunification in EU countries, or repatriation; therefore, social workers make careful assessments in line with their individual circumstances and best interests, and the preparation arrangements, while the fragility of the next steps is apparent. They suggest a family member to come and collect the child, but when it is not possible, they usually accompany the UAM to the destination country.

The spread of the pandemic and the restrictive measures have impacted everyday life, wishes, behaviours, and hopes of both UAMs and practitioners. Significant challenges are taking place in the fields of accommodation, guardianship, healthcare, and schooling, as outlined below.

4.1.1. Accommodation

Although family-based care, shelters and semi-independent living (SIL) accommodation are widely accepted as the most appropriate accommodation forms for UAMs (

Schofield and Beek 2009;

Derluyn 2018), in Greece they are scarce. Short and long-term foster care remains underdeveloped (

Kallinikaki 2015). METAdrasi, the NGO with relevant responsibility, reports that since 2015 they have placed only 104 UAMs in foster families (

METAdrasi 2020). On January 15, 2021, there were 62 UAM shelters integrated in the national system of child protection with a capacity of 25–30 children each (53 operate on the mainland, 9 on islands) with a total of 1637 places, and 81 SIL apartments in the mainland for those aged between 15–18, with a total of 324 places. These seek to provide minors with housing, appropriate supervision, and access to a range of protection services (

NCSS 2021).

Social work plays an integral role in all different forms of accommodation, to safeguard the fundamental rights of the UAMs (UNCRC, Article 22). Social workers are either coordinators or staff members of shelters, SIL accommodation, or safe zones where they focus on ensuring safe and decent living conditions, and the familiarisation of UAMs to the Greek reality. Moreover, they also support UAMs with regular online contact and re-unification with their families in Europe. Additionally, the integration of school age UAMs in local public schools (L. 3386/2005) and of youth in educational activities, and vocational training programmes could be said to be their “standard” priority in close collaboration with the teaching staff and local communities. Social workers have to prepare this integration (the prerequisite vaccination, health report) and to pursue UAMs and their parents that school enrolment does not affect their reunification process, and to deal with anti-immigrant instances of some native parents. According to the Ministry of Education, during the academic year 2018–2019, a total of 12,480 students of refugee status were registered in Greek public schools. In 2019–2020, reception classes for those older than 13 years were operated in 304 gymnasiums and lyceums (L. 3736/8.10.2019). Teachers recognise their positive contribution in fulfilling the processes, and emphasise “the expertise of school social workers to the refugee children’s effective inclusion in the classrooms and the schools” (

Katsama and Bakirtzi 2020, p. 206).

Since the onset of the pandemic, the restrictive measures have changed everyday life in every accommodation space for UAMs and residential staff. Under the first strict lockdown in March 2020, all hosting places for refugees were placed in quarantine, operating with emergency staff. Disseminating information about the risks of the virus, advising UAMs to “stay at home”, to follow the rules of hygiene and the strict forbiddances became the main duties of social workers. During the second lockdown, since November 2020, UAMs were entitled to a one-hour walk in the community. Moreover, social workers’ working hours were extended on the weekends. They were for listening to and dealing with UAMs’ disappointment and anger for the isolation from their friends and schoolmates, the interruption of most art and creative activities provided by local volunteers within the hosting placements, and for the interruption of walks and activities in gyms, sport centres and youth clubs in the community. Many UAMs insist that the pandemic is an alibi of the government to keep key spaces closed, and indefinitely postpone the exam of their asylum applications and the processes of expected relocations. Expressions of nostalgia (the pain involved in the yearning for home) and worries for the health and conditions of birth families are also exacerbated. As a result, “periods of boredom are followed by outbursts of anger”, a key phrase of the narration of a social worker participant to our relevant ongoing research (

Kallinikaki forthcoming).

In times of the COVID-19 emergency in the health sector, UAMs’ proper, timely access to health services is of great concern, mostly for the treatment of these with mental health issues and chronic physical diseases. Although they are entitled to the Temporal Number of Insurance and Health of Refugees (after their initial registration), which provides access to public health services and appropriate accommodation, scheduling an appointment with a specific doctor is competitive target. Thus, the mediation of hospital social workers becomes essential (

Sklavou 2019).

Social workers aim to maintain a routine and sense of belonging for UAMs by supporting them to focus on individual self-care and cohabitation issues, on teamwork for learning their desired foreign language, for daily activities, and for fun. Most attractive is the collaboration for innovative music, video creations and cooking. They also undertake initiatives for the supplement of individual tablets, board games and books, and encourage UAMs to keep maintaining digital contacts with schoolmates, or peers in the neighbourhood, and the community (

Kallinikaki forthcoming).

Similar conditions take place for those aged 18–25, hosted under the Emergency Support to Integration & Accommodation (ESTIA) programme implemented by the UNHCR in collaboration with local authorities and NGOs, in semi-autonomous co-existence status in cities (

ESTIA 2021). However, activities towards functional social integration and independency supported through educational and vocational training programs, sports, artistic and recreational activities, have been postponed or partially offered through digital infrastructure.

4.1.2. Relocation and Family Reunion

Social workers’ workload increased due to the consequences of the measures against the spread of COVID-19 in the implementation of the immense measures of family reunion and relocation. Procedures are progressing extremely slowly, and discordant with the reality. Under the most recent relocation programme, the Commission Action Plan for Immediate Measures to Support Greece as of March 2020, was introduced by the Greek government in cooperation with 11 participating EU member states, the UNHCR, IOM, UNICEF and the European Asylum Support Office (EASO). It aims to relocate 1600 UAMs and separated children living in precarious conditions from the Aegean Islands, but until August 2020, only 49 children had been relocated to France, 25 to Portugal, and 24 to Finland (

UNHCR 2020).

4.2. Guardianship

Due to the pandemic, existing unjustified delays and long-term processes in the implementation of the new law introduced in 2018 for the guardianship of UAMs were further extended. The issuance of the foreseen Presidential Degrees entitling the specific terms of it remains expected (

Oikonomou 2020).

It will replace the first regulatory framework with the Public Prosecutor for Minors or the local Public Prosecutor considered as the temporary guardian and create a Supervisory Guardianship Board, responsible for ensuring legal protection for UAMs with respect to disabilities, religious beliefs and custody issues, and responsible for guaranteeing safe accommodation and evaluating the quality of services provided to them. The guardian should be selected from a Registry of Guardians created under the National Centre for Social Solidarity, having to meet the needs of at least 20 children each.

According to social workers’ narrations, older UAMs have positively embraced the digital tools to reach their guardian, lawyer, or asylum officer, who they already know from sessions they had before the pandemic. Contacts with newcomers are full of challenges, made under strict rules with fewer interviews, using masks, sitting behind protective screens, and dealing with a lack of proper digital infrastructures, and/or with technical interruptions of the session.

4.3. School, Vocational Training Integration

The well-being of the refugee children depends on school experiences (

Richman 1998); attending school has been identified as a stabilising feature in the unsettled lives of young refugees (

Matthews 2008). In the case of refugee children residing in or crossing Greece, this important issue has been introduced by Law 3386/2005, stipulating that “Exceptionally, with incomplete supporting documents, children and children of third country nationals may enrol in public schools”.

A common element of social work practice and part of the inter-professional solidarity is networking with health state services for prerequisites such as the completion of health reports and vaccinations, and with educational institutions, agencies, NGOs, and other partners to ensure the predictable and well-coordinated provision of non-formal education services, as well as promoting equitable access to formal education and training for refugees and migrants in Greece. However, many refugee children and their families, and UAMs perceive schooling and learning the Greek language as a proof of “registration” in the country and fail to enrol. They do not want to stay in Greece; they want to move to the prosperous northern Europe (

Buchanan and Kallinikaki 2018).

Children who stay in camps and safe zones attend schools operating within them, while few children have the opportunity to attend non-formal afternoon classes. A good example is the International School of Peace for children from Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, Kurdistan, and North Africa, founded in 2017 on the Island of Lesbos, near the capital, Mitilini. Here, teachers are refugees from within the camp, who each teach children from their own culture and ethnicity in the school. The school is coordinated by a group of Jewish and Arab volunteers from Israel, members of a socialist youth movement in Israel, “Hashomer Hatzair”, and operates five days a week, providing the children with safety, security and an adaptive learning experience (

Huss et al. 2020;

Ben Asher et al. 2020).

Under the COVID-19 emergency, social workers and guardians who support unaccompanied minors are concerned about the consequences of the interruption and temporal changes from face-to-face to digital teaching in schools, vocational training and internships caused by the pandemic. These changes disturb their basic routine, necessary for their cognitive–emotional development (

Kohli 2011), as well as for the present conditions of life and for their future.

Social workers deal with UAMs’ limited interest in following classes of the state secondary education, due to delays in the progress of their cases, the difficulties to attend the courses, mostly for those without any experience of schooling, and due to the refusal to learn Greek. Furthermore, the new complexity of their situations and prospects is associated with the poor Wi-Fi of many hosting places which disrupts face-to-face schooling (

Kallinikaki forthcoming). Additionally, they support their access to online language courses and any innovative actions such as key websites. For example, the COVID-19 refugees information website, which gives tips in six languages (

Attica Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Technical Working Group 2020), and the online creative writing workshops, voicing UAM’s thoughts and emotions of teenage refugee residents across Greece during the pandemic in a range of languages including Farsi, Arabic, French, Somali, and English (

Hellenic Theatre/Drama & Education Network 2020).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper has explored how the reception systems for UAMs in two gateway countries to Europe, namely, Italy and Greece, has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and how a tightening of the living conditions for minors hosted in these places has been seen (

Noury and Leone 2020).

Indeed, the EU bloc acts to restrict the flow of these children arriving from North Africa and the Middle East. In recent years, the number of children in facilities has varied according to the political, economic, and social conditions in the various countries of origin, as well as the various regulatory measures and international agreements that Europe has signed with certain countries. Arguably, these children’s rights are protected by global conventions and treaties, and at times, even by the domestic laws of nation states. However, through processes of Kafkaesque bureaucracy and inordinate delays, UAMs have experienced a steady erosion of their rights (

Bhabha 2014), and an intensification in precarity that, since February 2020, has been further exacerbated in multiple ways due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Both Italy and Greece have been impacted severely by the pandemic. As of January 18, 2021, there have been 82,554, and 5598 deaths, respectively. The healthcare system in both nations has been under severe strain. Both countries have experienced restrictive measures, including the introduction of non-essential movement, and the closure of educational establishments, leisure and hospitality services, and other sectors to curb the spread of the virus. Such restrictions have impacted everyday life with increasing evidence of negative outcomes including loneliness, mental health difficulties, inter-personal violence, educational and employment disadvantage, and poverty (

Bhatia 2020;

Bradbury-Jones and Isham 2020;

Caffo et al. 2020;

Cusinato et al. 2020;

Magklara et al. 2020).

Given the closure of regular life and activity, the situation for UAMs, whose lives were precarious and in limbo in pre-pandemic times, is now further exacerbated. The pre-existing vulnerabilities in the context of child well-being and immigration hurdles for UAMs are well documented in the literature (

Buchanan and Kallinikaki 2018;

Barn et al. 2020;

Chase and Allsopp 2020). Such precarity and liminality is further intensified in these pandemic times, with grave consequences for the well-being and the future status of UAMs.

Crucially, we can try to understand the reported UAM experiences and perceptions in the context of the processes of “real and symbolic violence” as UAMs inch towards adulthood and realise the implications of their precarity, the impossibility of family reunification, and possible deportations to situations of poverty, conflict, and further trauma (

Roth 2019;

Chase 2020). Indeed, processes of integration are marred by the closures of activities including language learning, education, training, and internships (

Giovannetti 2017;

Jiménez-Álvarez and Vacchiano 2011), resulting in a threat to UAMs’ vocational identity with regard to study and work (

Oppedal et al. 2017). Such a precarious context risks the worsening of emotional and behavioural problems (

Derluyn et al. 2008;

Thommensen et al. 2013), and presents a threat to the development of inclusivity, active citizenship, and a sense of belonging (

Rania et al. 2018).

Given the increasing immigration hostility in these and other EU countries and its interaction with cumbersome bureaucracy, and now the COVID-19 pandemic, Italy and Greece have, de facto, become host countries where there is an uncertain future for these minors. Worryingly, the pandemic restrictive measures and social workers’ difficulties in overcoming the halt to legal, educational, and vocational challenges exposes the weakening of the social and relational bond that is the basis of a successful integration path. This situation requires particular attention to certain key aspects, such as the right to health, education and training, hospitality, and the need to ensure the stability of UAMs’ legal status, which have all been put at risk by the ongoing health emergency. Social workers continue to seek to support UAMs, within a framework of the ethic of care, to address vulnerability and disadvantage for a group that is further trapped in precarious circumstances.

This paper has shone a light on some of the challenges faced by the social work profession. In addition to managing the emotional aspects of tensions of minors connected to the state of emergency, social workers have been charged with the responsibility of putting in place operational strategies to balance the unfavourable conditions that have negatively weighed on the perspective of the integration of minors, heavily penalised in their essential rights.

With the suspension of key services and amenities, and with a practical halt to the due process of immigration and asylum, social workers are facing a difficult challenge to prevent the deterioration of UAMs’ mental health and well-being. Indeed, social workers are reporting psychological difficulties among UAMs in accepting the restrictive pandemic measures. The reported “Libyan Syndrome” suggests that existing mistrust in immigration and welfare services is now particularly pronounced as UAMs struggle to reconcile previous traumatic experiences of a curtailment of freedom and autonomy within this new pandemic context (

López Peláez et al. 2020). Similar previous traumas were reported by social workers in Greece, where UAMs deny the reality of the pandemic.

It is hoped that the insights provided in this paper will go some way to help inform not only policy, practice, and provision, but also some guidance for future research to examine how societies must continue to exercise their duty to safeguard the well-being of marginalised groups in a crisis.