Abstract

This study examines the correlations between urban environmental satisfaction, neighborhood relations, and livability. Previous studies on livability have insufficiently dealt with urban environments and neighborhood relations and have failed to conduct an integrated analysis that considers the causal relationships between these factors. To fill these knowledge gaps, this study includes urban environmental satisfaction and neighborhood relations as factors affecting livability. Moreover, this study verified the mediating effect of neighborhood relations between urban environmental satisfaction and livability. Online surveys were carried out with 750 residents in Seoul, South Korea, and the structural equation model (SEM) was employed. The results indicated that a higher level of urban environmental satisfaction affected livability positively. In particular, the accessibility had the greatest effect on livability. In addition, neighborhood relations had a mediating effect on the pleasantness and safety of urban environments. Today, many developing countries are undergoing rapid urbanization, as Seoul has experienced in the past. However, this can cause a number of simultaneous side effects, which lower livability. Furthermore, this leads to population decline which might hinder urban sustainability. Therefore, this study suggests important policy implications for achieving urban sustainability by improving livability.

1. Introduction

Rapid economic growth and urbanization have been witnessed in numerous metropolitan areas in recent decades. Though rapid urban development can have positive socio-economic consequences such as urban infrastructure improvements, it can also lead to increased rates of crime, air pollution, and traffic congestion (Ouyang et al. 2017; Zhan et al. 2018; Zhang and Gao 2008). As a result, residents in urban areas may move to suburban areas, and this decline in a city’s population can present several problems. For example, population decline corresponds to lower local tax revenue sources, which may worsen financial health. Moreover, residents themselves become monitors for crime. Thus, a smaller residential population would increase the likelihood of crime (Kim and Kwon 2009). If these problems persist, they can negatively impact a city’s long-term sustainability. Therefore, local governments need to increase livability to maintain population. Based on the above discussions, this study seeks to identify the factors influencing urban livability.

Previous studies on livability are mainly concerned with economic factors (Easterlin et al. 2012; Okulicz-Kozaryn 2011). They have argued that increasing regional employment opportunities can have a positive impact on urban satisfaction. However, non-economic factors that may affect livability vary widely. In particular, urban environments and neighborhoods that residents encounter every day can have significant influence on the quality of life. Some studies have examined the relationship between these two variables and livability, but not many (Marans 2003; Mouratidis 2018; Zhan et al. 2018). Moreover, studies on local satisfaction have considered urban environments and neighborhood relations as important variables (Anton and Lawrence 2014; Özkan and Yilmaz 2019). Considering that local satisfaction is closely related to livability, it can be expected that urban environments and neighborhoods will have a significant impact on livability. Therefore, this study considered urban environmental satisfaction and neighborhood relations as factors affecting livability.

In addition, studies on urban walkability or urban planning that focus on anchor facilities such as cultural theaters have examined the causal relationships between urban environments and neighborhood relations (Clopton and Finch 2011; Jun and Hur 2015; Wood et al. 2008). Specifically, the improvement of urban environments should be prioritized in a way that increases the accessibility to urban facilities and encourages residents to interact with one another. Considering that the factor of neighborhood relations has been identified as a significant influence on livability (Marans 2003; Mouratidis 2018; Zhan et al. 2018), this study suggests that neighborhood relations may act as a mediator between urban environments and livability.

To fill the gaps in the existing literature, this study presents the following research questions: (1) How do urban environmental satisfaction and neighborhood relations affect livability? (2) Do neighborhood relations have a mediating effect between urban environmental satisfaction and livability? In this study, urban environment satisfaction was divided into the sub-components of accessibility, pleasantness, and safety, and analysis was conducted using the structural equation model (SEM).

This study contributes to urban sustainability research in the following ways: First, it examines the priorities among the sub-components of urban environments for livability, which can provide a rationale for determining the resource distribution of urban environment improvement projects. Second, this research assesses the role of non-physical factors, such as neighborhood relations (i.e., interaction among residents). For example, it verifies the direct effects of neighborhood relations on livability and the mediating effect between urban environmental satisfaction and livability. Ultimately, this study presents policy implications for efforts to increase urban livability by validating the relationships between the variables of urban environmental satisfaction, neighborhood relations, and livability.

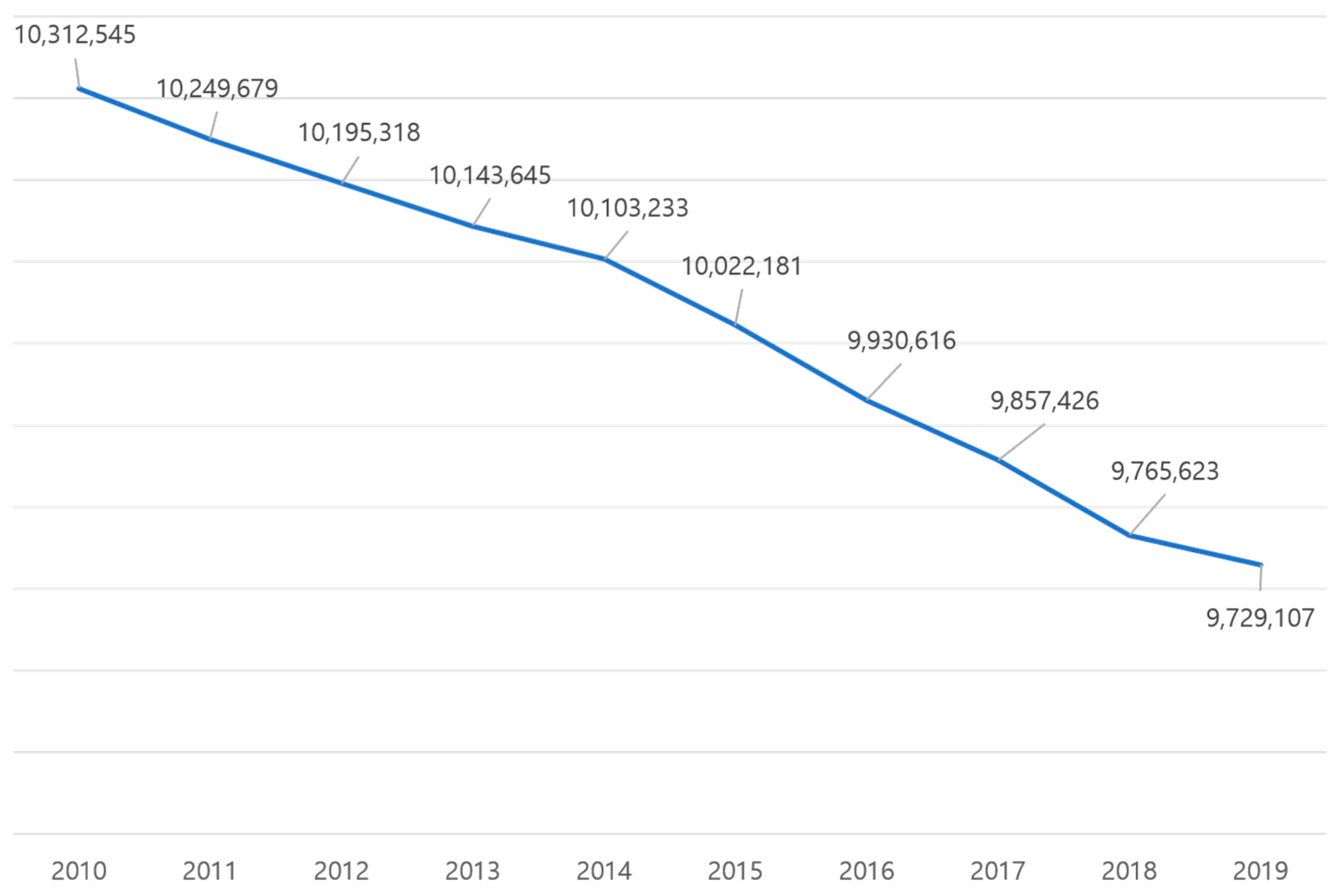

Concurrently, this research provides an empirical analysis of Seoul, South Korea. Seoul is a representative city that has experienced rapid urbanization and is becoming a role model for many developing countries. However, Seoul’s population has continued to decline over the last decade, making it a suitable focus for this study. Looking at Seoul could have important implications for many developing countries that could experience a similar urbanization process.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Livability and Its Importance

Livability is considered an indicator of quality of life and the subjective well-being of urban dwellers (Badland et al. 2014; Norouzian-Maleki et al. 2015). There is no clearly agreed upon definition of livability, and it can be interpreted in a very complex and diverse way (Ruth and Franklin 2014). For example, Timmer and Seymoar (2006) described livability as residents’ perceived quality of life. Furthermore, livability was defined as a living criterion for residents in an area (Okulicz-Kozaryn 2011) or the suitability of a certain location for human living (Merriam-Webster 2017). More specifically, some researchers explained that livability refers to how an area meets the necessary requirements (Newman 1999). That is, every human being tends to meet their needs and interests primarily within their residential area. If one can satisfy one’s needs and desires within their region, they will want to continue to live in that area (Lee et al. 2004). Therefore, in this study, livability is intended to define sustainability for human living.

Livability can contribute to both personal and local aspects. First, on the personal side, livability means securing housing stability, which in turn could lead to an increase in one’s quality of life (Mouratidis 2018, 2020). Then, from a regional perspective, it is important to prevent problems that may arise from a decline in the population. Specifically, if an area experiences a decline in its number of residents, its local tax revenues may decrease, possibly worsening the city’s financial health. In addition, residents themselves serve as monitors for crime. Thus, population decline would lead to a higher crime risk (Kim and Kwon 2009). Therefore, increasing livability in the region is a very important policy task.

On the other hand, the increase in livability by improving the urban environment is being witnessed in many cities in Europe and the United States. For example, New York in the United States and Bilbao in Spain are among the most representative cities that have grown again through the improvement of the urban environment (Furman and Kroeger 2013; Patterson 2020). Of course, some studies have considered urban environments and neighborhood relations as factors influencing the quality of life or local satisfaction (Anton and Lawrence 2014; Fornara et al. 2010; Özkan and Yilmaz 2019). This suggests the possibility that urban environments and neighborhood relations may also have a positive impact on livability. However, not many studies have directly verified the relationship between these variables and livability. Therefore, this study focuses on the relationship between the following variables: urban environments, neighborhood relations, and livability.

2.2. Urban Environmental Satisfaction and Livability

Urban environments comprise an integration of physical conditions in which an individual lives and routinely comes into contact in a particular area (Moon et al. 2018). This will have a significant impact on residential life by inducing a response of satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Urban environments can be divided into various sub-components, and the level of satisfaction, and by extension livability, felt by residents may vary depending on each component (Özkan and Yilmaz 2019). In this study, the components of the urban environments were divided into accessibility, pleasantness, and safety. These three components are important criteria considered by international organizations such as the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in assessing the quality of residential environments (OECD 2011).

2.2.1. Accessibility

Accessibility can be discussed at various levels. However, this study defined accessibility as physical facilities in the community. Residents will be satisfied with their community if there are various facilities that are easily accessible. In many studies, the satisfaction level with accessibility has been cited as an important factor in enhancing livability (Mohit et al. 2010; Olsson et al. 2013; Tao et al. 2014). For example, De Vos and Witlox (2017) explained that the higher the accessibility to facilities such as shopping centers, public institutions, and cultural facilities is, the higher the livability.

2.2.2. Pleasantness

Pleasantness refers to satisfaction with the natural environment in the region. According to many recent studies, the importance of the natural environment has been increasing (Badland et al. 2014; Buys and Miller 2012; Rehdanz and Maddison 2008). These studies argued that natural environments can substantially affect residents’ quality of life by providing them rest areas. Therefore, the higher the residents’ satisfaction level with the existence and use of green parks in the region, the higher the region’s livability. Specifically, Ujang et al. (2015) conducted an interview with the users of green parks to confirm that the level of satisfaction with the use of green parks is an important factor in urban satisfaction.

2.2.3. Safety

Safety means how safe it is from accidents, such as natural disasters or fires, and crimes. It is promoted as one of the important factors that make up urban environments. Many studies assert that satisfaction with urban environments is closely related to crime rates or accident rates (De Vos and Witlox 2017; Ibem and Aduwo 2013; Marans and Stimson 2011; Martínez et al. 2015). For example, Buys and Miller (2012) found that safety was an important factor in residential satisfaction in cities with high population density (e.g., in Brisbane, Australia).

Based on the above discussions, this study postulates that higher satisfaction levels with urban environments yield increased livability. Therefore, this study hypothesizes the following:

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

Satisfaction with sub-components of urban environments (a) accessibility; (b) pleasantness; and (c) safety will have a positive impact on livability.

2.3. Mediating Effect of Neighborhood Relations

Social relations within neighborhoods have been identified as an important factor of urban satisfaction. For example, Lewicka (2011) explained that social capital based on neighborhood relations can have a positive effect on building community attachment. Recent studies have identified residents’ trust in their neighborhoods, number of friends, and social interactions as factors that can measure neighborhood relations (Kamalipour et al. 2012; Nicholas et al. 2009; Nunkoo and Gursoy 2012; Özkan and Yilmaz 2019).

Previous studies suggest the possibility of a mediator between urban environments and livability. They have shown that the status of neighborhood relations is a dependent variable that is influenced by urban environmental satisfaction and at the same time an independent variable that directly affects livability. If each of these relationships is empirically validated, neighborhood relations can have a mediating effect between urban environmental satisfaction and livability. The following discusses these relationships in detail.

2.3.1. The Relationship between Urban Environmental Satisfaction and Neighborhood Relations

Some studies explain that urban environments play an important role as a meeting place or contact point for residents. For example, residents can take a break and enjoy urban life with their neighbors in a park or a café, recreational activities that increase interaction between residents (Cho and Lee 2017; Frank et al. 2010). Moreover, studies on the walkability emphasize that urban environments that promote walking activities further strengthen neighborhood relations (Jun and Hur 2015; Joung 2014). For example, safer urban environments would increase residents’ walking activities, which would help increase their frequency of contact. Recent urban planning initiatives that prioritize anchor facilities also reflect the foundational relationship between urban environments and social relationships (Clopton and Finch 2011; Ma 2017 Seifried and Clopton 2013). According to these assessments, the higher the satisfaction level of urban environments, the better its neighborhood relations.

2.3.2. The Relationship between Neighborhood Relations and Livability

Many studies on urban satisfaction refer to social capital based on relationships among neighbors as an important factor on livability. They stress that community ties or social activities can positively affect the level of satisfaction with the region (Lewicka 2011; Özkan and Yilmaz 2019). For example, Özkan and Yilmaz (2019) measured social ties through formal and informal social activities and interactions between residents, which were shown to have a positive effect on urban satisfaction. In this regard, Lewicka (2011) explained that social capital or social bonding makes “0regions” more “meaningful places” for residents, which also has a positive impact on residents’ attachment to their homes and communities.

Combining these discussions, it can be expected that neighborhood relations may have a mediating effect between urban environmental satisfaction and livability. Thus, this study hypothesizes the following:

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

Neighborhood relations will have a mediating effect on urban environmental satisfaction in terms of (a) accessibility, (b) pleasantness, (c) safety and livability.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area: Seoul

In this study, Seoul was selected as a specific area for study. Seoul was once the most populous city in Korea through the urbanization process (Joo 2020). However, the number of residents has continued to decline in recent years (see Figure 1). Therefore, conducting this study on Seoul utilizes the results in a practical way. Many developing countries are currently experiencing rapid urbanization as Seoul underwent in the past. The findings of this research are expected to provide important implications for those cities.

Figure 1.

Population changes in Seoul (Source: 2010–2019 Population Census by Statistics Korea n.d.).

3.2. Data Collection

This study collected data through an online survey of Seoul residents via Embrain’s panels. Specifically, the survey was conducted by sending an email to panels with a link to participate in the survey. In addition, respondents were randomly extracted with no specific conditions. Thirty people per district were chosen equally for the study in order to minimize errors depending on regional characteristics. Consequently, a total of 750 samples were collected from all 25 districts in Seoul. The sample characteristics are as follows (see Table 1): First, the sex ratio between males (42.7%) and females (57.3%) was close, and their ages ranged from 20 to 68. Moreover, the length of residence in Seoul ranged from a period of less than one year to more than 15 years. This study intended to include samples of various characteristics.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

3.3. Measurements

Survey questions were developed and revised based on a review of previous studies. Items were rated using a five-point Likert scale. Moreover, each respondent was required to respond to the items with reference to their respective autonomous district.

First, urban environmental satisfaction was rated in terms of accessibility, pleasantness, and safety (Kamalipour et al. 2012; Özkan and Yilmaz 2019; Ujang et al. 2015). Accessibility was measured by the satisfaction level of the accessibility to public institutions, cultural facilities, commercial facilities, and medical institutions. At this time, the means of access or distance is not important. It depends on individual recognition. For example, some people may think it is close to a 15 min drive, while others may perceive it as close to a 15 min walk. Pleasantness was measured in terms of satisfaction with green parks and the surrounding natural environment. Safety was measured in terms of safety from natural disasters, crime, and deteriorated facilities that can cause accidents to users. Then, on the basis of previous studies, the section regarding neighborhood relations consisted of questions about the reliability of relationships among neighbors and the frequency/quality of their social interactions (Kamalipour et al. 2012; Nicholas et al. 2009; Nunkoo and Gursoy 2012; Özkan and Yilmaz 2019). Finally, livability was highly relevant to the intention to reside in their regions continuously (Lee et al. 2004; Merriam-Webster 2017). More specifically, livability included both whether to continue to reside in the current residential area generally or with a more positive outlook even if given the opportunity to leave the area.

3.4. Analytic Method

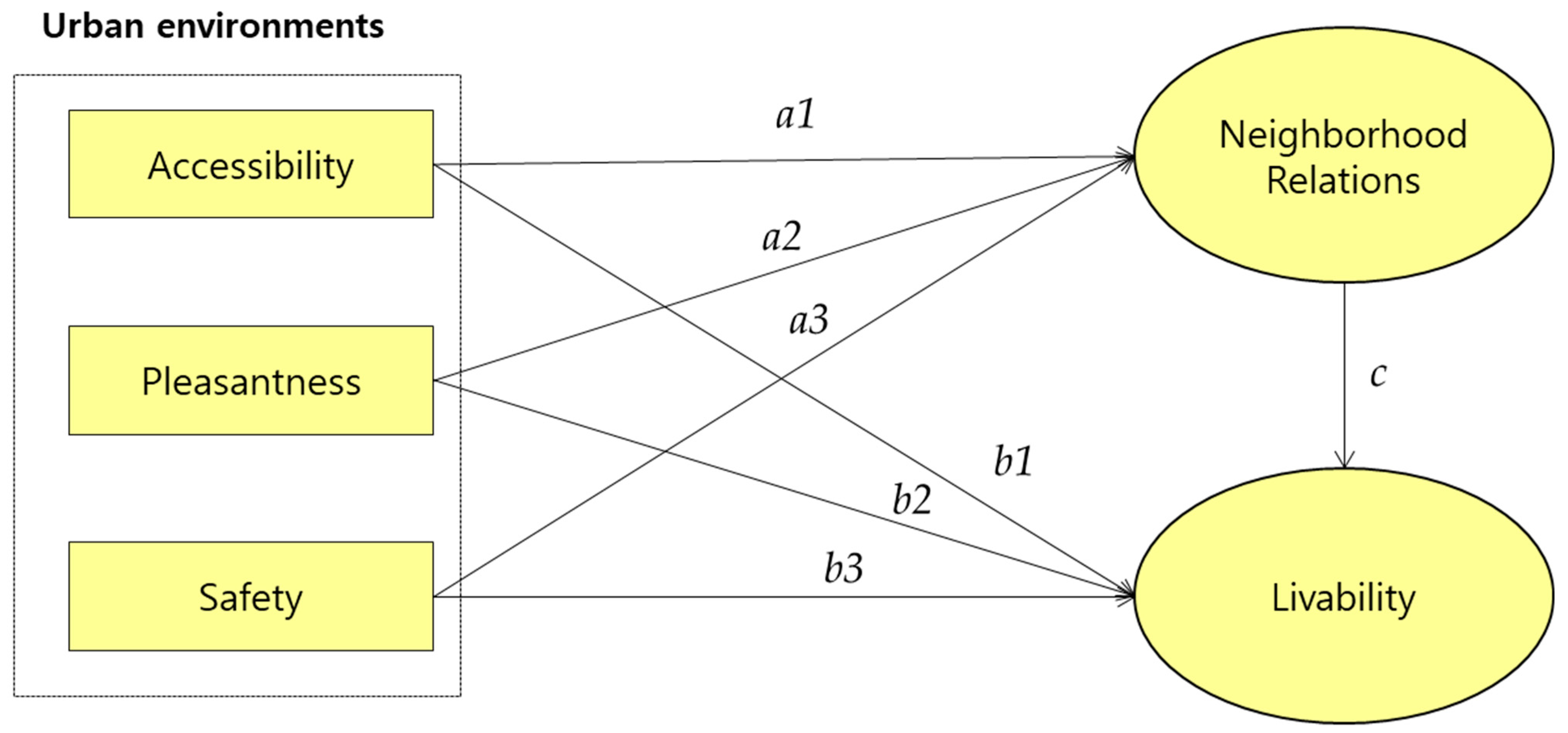

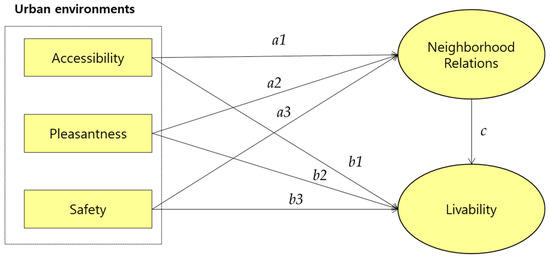

The analysis was carried out in accordance with the following procedures: First, the internal validity of measurements was examined through exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and reliability analysis. Second, descriptive and correlation analyses between factors were conducted. Third, an SEM analysis was performed for hypothesis testing. The SEM shall be a rule to only use continuous variables (Bae 2017). Therefore, unlike a regression model, it does not include categorical control variables such as sex or occupation in the model. However, the SEM has advantages in verifying robustness between measurements and factors, and complex relationships between factors (Bae 2017). In this study, accessibility, pleasantness, and safety, which are sub-components of urban environmental satisfaction, were organized as exogenous variables, while neighborhood relations were classified as a mediator, and livability was considered an endogenous variable (see Figure 2). All analyses were conducted through SPSS 24.0 and AMOS 24.0.

Figure 2.

Research model.

On the other hand, the SEM can determine the direct and indirect effects on the dependent variable. At this time, indirect effects can be calculated by the mediator. In addition, these two effects can be summed up to determine total effects. The equation for the effect of each factor on livability is as follows:

Total effect of accessibility = b1 (Direct effect) + a1*c (Indirect effect)

Total effect of pleasantness = b2 (Direct effect) + a2*c (Indirect effect)

Total effect of safety = b3 (Direct effect) + a3*c (Indirect effect)

Total effect of pleasantness = b2 (Direct effect) + a2*c (Indirect effect)

Total effect of safety = b3 (Direct effect) + a3*c (Indirect effect)

4. Results

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Reliability Analysis

To verify the validity and reliability of measurements, the EFA and reliability analysis were conducted (see Table 2). The principal component factor analysis and varimax rotation were applied to the EFA. A total of five factors informed the total of 16 questions, with three exogenous variables, one mediator, and one endogenous variable. For each, the factor loadings were found to be more than 0.5 and the eigenvalues were also greater than 1, confirming that the measurements’ ability to explain individual factors was reasonable. In addition, a Cronbach α value of 0.7 or higher is considered acceptable (Lee and Lim 2017). In this study, all factors met more than 0.7.

Table 2.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and reliability analysis.

4.2. Descriptive and Correlation Analyses

Table 3 shows the results of the descriptive and correlation analyses between factors. First, accessibility was the highest among the sub-components of urban environmental satisfaction with 3.59 points, while pleasantness and safety were similar at 3.3 points. Neighborhood relations, on the other hand, had the lowest score of 2.76. Livability was moderate at 3.29. In addition, there was a statistically significant positive correlation between all factors at the 99% confidence level. In this regard, if the correlation coefficient is too high (over 0.7), it is difficult to identify the causal relationship between the factors exactly (Lee and Lim 2017). However, the correlation coefficient of all factors was less than 0.6.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and correlations between factors.

4.3. Structural Equation Model (SEM)

In this study, an SEM analysis was conducted by establishing a path relationship between factors for hypothesis testing. Prior to the specific discussion, the model fit was identified (see Table 4). As a result, all indicators have been verified to have adequate levels. The results of the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is presented in Appendix B.

Table 4.

Model fit.

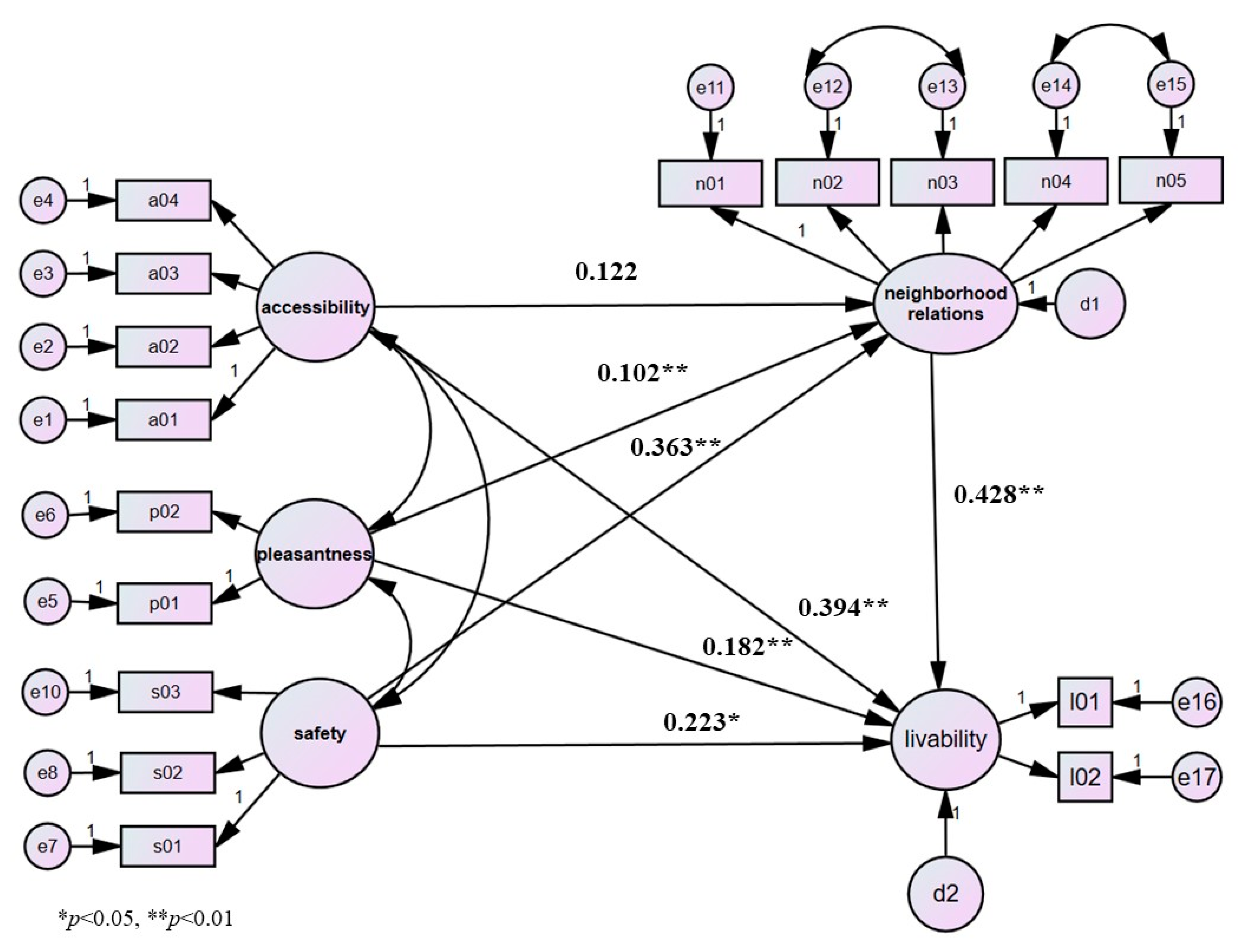

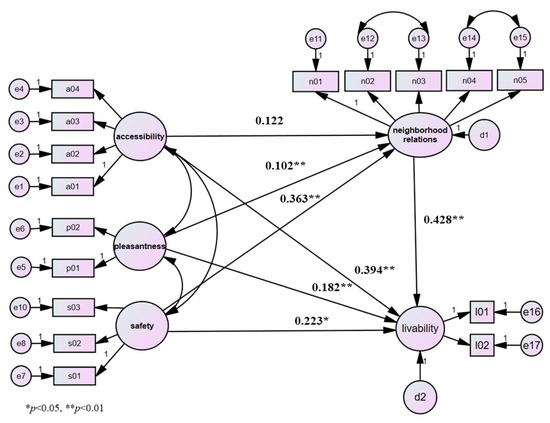

Then, we are interested in the specific result of SEM (see Figure 3). To test Hypothesis 1, this study proposed that as urban environmental satisfaction increases, livability increases. The results show that accessibility (B = 0.394, p < 0.01), pleasantness (B = 0.182, p < 0.01), and safety (B = 0.223, p < 0.05) were all found to have positive effects on livability. In more detail, the influence of accessibility was proven to be the greatest over other components.

Figure 3.

Structural equation model (SEM) (1) a01~a04, p01~p02, s01~s03, n01~n05, l01~l02: measurements; (2) e1~e17: measurement error; (3) d1~d2: structural error.

To test Hypothesis 2, this study examined whether neighborhood relations mediated the relationship between urban environmental satisfaction (i.e., accessibility, pleasantness, and safety) and livability. If the path of urban environmental satisfaction and neighborhood relations is significant, and the relationship between neighborhood relations and livability is also significant in SEM, we can regard neighborhood relations as having a mediating effect. First, it was observed that NE (B = 0.102, p < 0.01) and SE (B = 0.303, p < 0.01) have a positive impact on neighborhood relations. Then, neighborhood relations (B = 0.428, p < 0.01) were found to have a positive effect on livability. Based on these findings, the factor of neighborhood relations was proven to have a significant mediating effect between pleasantness and safety among urban environmental satisfaction and livability.

Meanwhile, this study determined a direct, indirect, and total effect on livability according to the relationship between factors (see Table 5). At that time, the total effect was based on the sum of the direct and indirect effect. Moreover, the Sobel test was conducted to verify the statistical significance of the indirect effect by the mediator. As a result, in the relationship between pleasantness, safety, and livability, the mediating effect of neighborhood relations was verified to be significant. However, the mediating effect of neighborhood relations between accessibility and livability was not statistically significant. Therefore, the only direct effect was applied in calculating the total effect of accessibility to livability.

Table 5.

Direct effect, indirect effect, and total effect.

Consequently, comparing the total effect of each factor on livability, the effect of accessibility was found to be the greatest. In addition, the indirect effect of neighborhood relations has been proven to be the greatest between safety and livability. This means that higher satisfaction with neighborhood relations can further increase the influence of safety on livability.

4.4. Discussion

The above results have several implications for the relationships between urban environmental satisfaction, neighborhood relations, and livability.

First, urban environmental satisfaction was found to have a positive effect on livability. This means that the higher the satisfaction with urban environments, the higher the livability. Previous studies have also shown the same relationship between these variables (Badland et al. 2014; Buys and Miller 2012; De Vos and Witlox 2017; Ibem and Aduwo 2013; Marans and Stimson 2011; Martínez et al. 2015; Tao et al. 2014). More specifically, the accessibility was found to have the greatest impact on the sub-components of urban environments. One of the reasons why many people move from rural areas to urban areas is because of the accessibility to various facilities in their community. It increases the convenience of their life (Zhan et al. 2018). Similarly, Lewicka (2011) explained that the presence of various accessible facilities in the region is an important factor for local satisfaction. Özkan and Yilmaz (2019) also found that these facilities have a significant impact on the accessibility to open space. In particular, accessibility to public transportation or convenience facilities is considered important in choosing housing in Korea. For example, Park and Lee (2015) explained that commuting conditions and convenience facilities such as commercial stores and medical institutions were relatively important for residents in the Seoul metropolitan area. Based on the above discussion, accessibility should be the focus when increasing livability through the improvement of urban environments. Specifically, residents’ primary intention is to meet their needs within their respective residential areas (Lee et al. 2004; Lee 2020). Seoul has more companies than other regions (Joo 2020). For residents, therefore, public transportation access (e.g., subway stations) for commuting will significantly influence livability. After all, it will be necessary to continuously focus on the infrastructure necessary for residents to ensure access to urban facilities and to make efforts to check and improve upon the level of accessibility.

Second, the variable of neighborhood relations was found to have a significant mediating effect between pleasantness, safety, and livability. First, satisfaction with green parks increases the frequency of contact between neighbors, which in turn has a positive effect on improving relations (Cho and Lee 2017; Frank et al. 2010), and thus on increasing local satisfaction. Thus, safety is one of the important factors in assessing the quality of walk-friendly environments (Wood et al. 2008). Therefore, the study on a community’s walkability explained that a safe environment affects the promotion of walking activities, thereby promoting increased interactions between residents (Lund 2002; Jun and Hur 2015). These results are different from existing studies in that the relationships between variables were analyzed in an integrated approach, proving that the path relationship between “urban environment satisfaction → neighborhood relations → livability” is statistically significant, although it is partial. Therefore, the effect of urban environmental satisfaction on livability is further increased when the variable of neighborhood relations was a mediating factor. Meanwhile, distrust among neighborhoods is increasing as infectious diseases such as MERS and COVID-19 spread around the community. This is one of the major threats to the safety of the community. In this study, the role of neighborhood relations between safety and livability was found to be relatively important. Depending on these findings, it can be seen that the role of neighborhood relations in increasing the livability is very considerable. In particular, “urban regeneration”, which is currently underway in many domestic cities (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport 2018), is different in that it also considers urban qualitative development as opposed to urban redevelopment, which has only pursued quantitative development in the past (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport 2018; Seoul Metropolitan Government 2015). In other words, qualitative developments such as the integration and revitalization of local communities are important in urban regeneration, further increasing the demand for better neighborhood relations. Therefore, it is necessary to continue to support the “Village Community Project” currently underway in the Seoul Metropolitan Government (Seoul Metropolitan Government 2013). The Village Community Project aims to rebulid the relationship between residents and activate the local community. It began in 2012, and more than 130,000 residents (2015) participate in community groups (Seoul Community Support Centre Homepage: seoul.org (accessed on 23 November 2020).

5. Conclusions

This study examined the relationship between urban environmental satisfaction, neighborhood relations, and livability. Previous studies of livability have been insufficient in dealing with urban environments and neighborhood relations, and there have been limits to the integrated analysis of these variables. To fill these gaps, this study empirically verified the impact of urban environmental satisfaction on livability and the mediating effect of neighborhood relations on this dynamic by conducting a survey of Seoul residents.

This study contributed the following: First, the priorities of urban environmental factors for increasing livability were derived. In particular, the accessibility to urban facilities was found to be the most important. Second, the examination of the social factor was carried out in the various aspects. Specifically, neighborhood relations have been found to play a significant role in livability.

On the other hand, while Seoul is a representative city that experienced rapid urbanization, the city’s population is currently in constant decline. Therefore, the Seoul Metropolitan Government’s urban regeneration projects also present the population decline as a policy task. Many developing countries are today pursuing rapid urbanization like Seoul did in the past, and they may need to brace for a similar population decline following the urbanization process. In this regard, dealing with Seoul as a study case could provide important implications for those countries.

There are also limitations to this study. First, there was a somewhat lack of discussion about each component of the urban environments. For example, this study understood that accessibility is for physical facilities in communities. However, the accessibility will also be applicable for other parts such as green parks. Second, this study did not consider air pollution or noise as influential factors in livability (Szopińska 2019). These factors are critical to residential satisfaction. Future studies will need to include them. Third, discussions about differences in demographic groups will be needed. This study focused on the examination of relationships between factors through SEM. Therefore, the analysis based on demographic characteristics was not included. However, it will provide meaningful results for livability. Finally, in this study, due to the nature of the online survey, the younger generation was somewhat overrepresented. Given the growing number of elderly people in Korea today as well as around the world, it is likely that in the future, sophisticated sample design and data collection will be needed to secure better representative samples of older populations for more accurate analyses.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because of privacy considerations.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank the editors and the reviewers for their constructive comments that helped improve the current paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Descriptive Statistics of Variables.

Table A1.

Descriptive Statistics of Variables.

| Factors | Variables | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accessibility | Satisfaction with accessibility to commercial facilities | 3.66 | ±1.018 |

| Satisfaction with accessibility to medical institutions | 3.57 | ±0.945 | |

| Satisfaction with accessibility to cultural facilities | 3.42 | ±1.057 | |

| Satisfaction with accessibility to public institutions | 3.69 | ±0.856 | |

| Pleasantness | Satisfaction with using green parks | 3.33 | ±1.034 |

| Satisfaction with natural environment | 3.30 | ±1.032 | |

| Safety | Safety from natural disasters | 3.50 | ±0.880 |

| Safety from risk factors such as crime | 3.33 | ±0.924 | |

| Safety from deteriorated facilities | 3.34 | ±0.847 | |

| Neighborhood relations | Helping community residents often | 2.72 | ±0.827 |

| Getting help from community residents often | 2.65 | ±0.832 | |

| Knowing many community residents | 2.83 | ±1.092 | |

| Having residents for talking comfortably | 2.65 | ±1.057 | |

| Trust in residents | 2.94 | ±0.808 | |

| Livability | (Even if I have a chance to move somewhere else), I am willing to reside in our community continuously | 3.49 | ±0.959 |

| (In general), I am willing to reside in our community continuously | 3.09 | ±1.071 |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis.

Table A2.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis.

| Items | Standard Coefficient | S. E | C.R | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a01 | ← | Accessibility | 0.563 | - | - | - |

| a02 | ← | 0.732 | 0.118 | 13.649 | ** | |

| a03 | ← | 0.742 | 0.114 | 13.730 | ** | |

| a04 | ← | 0.705 | 0.103 | 13.389 | ** | |

| p01 | ← | Pleasantness | 0.865 | - | - | - |

| p02 | ← | 0.940 | 0.045 | 24.368 | ** | |

| s01 | ← | Safety | 0.658 | - | - | - |

| s02 | ← | 0.746 | 0.074 | 16.194 | ** | |

| s03 | ← | 0.777 | 0.069 | 16.580 | ** | |

| n01 | ← | Neighborhood relations | 0.757 | - | - | - |

| n02 | ← | 0.695 | 0.060 | 15.797 | ** | |

| n03 | ← | 0.756 | 0.060 | 17.091 | ** | |

| n04 | ← | 0.653 | 0.075 | 15.532 | ** | |

| n05 | ← | 0.619 | 0.073 | 14.728 | ** | |

| l01 | ← | Livability | 0.808 | - | - | - |

| l02 | ← | 0.831 | 0.058 | 19.665 | ** | |

** p < 0.01.

References

- Anton, Chris E., and Carmen Lawrence. 2014. Home is where the heart is: The effect of place of residence on place attachment and community participation. Journal of Environmental Psychology 40: 451–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badland, Hannah, Carolyn Whitzman, Melanie Lowe, Melanie Davern, Lu Aye, Iain Butterworth, Dominique Hes, and Billie Giles-Corti. 2014. Urban liveability: Emerging lessons from Australia for exploring the potential for indicators to measure the social determinants of health. Social Science & Medicine 111: 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Byung-Ryul. 2017. Structural Equation Modeling with Amos 24. Seoul: Chungram Publishing. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Buys, Laurie, and Evonne Miller. 2012. Residential satisfaction in inner urban higher-density Brisbane, Australia: Role of dwelling design, neighbourhood and neighbours. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 55: 319–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Hyemin, and Sugie Lee. 2017. A study on the effects of neighborhood environmental characteristics on the level of the social capital: Focused on the mediating effect of walking activity. Journal of Korea Planning Association 52: 111–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clopton, Aaron Walter, and Bryan L. Finch. 2011. Re-conceptualizing social anchors in community development: Utilizing social anchor theory to create social capital’s third dimension. Community Development 42: 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, Jonas, and Frank Witlox. 2017. Travel satisfaction revisited. On the pivotal role of travel satisfaction in conceptualising a travel behaviour process. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 106: 364–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, Richard A., Robson Morgan, Malgorzata Switek, and Fei Wang. 2012. China’s life satisfaction, 1990–2010. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109: 9775–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornara, Ferdinando, Marino Bonaiuto, and Mirilla Bonnes. 2010. Cross-validation of abbreviated perceived residential environment quality (PREQ) and neighborhood attachment (NA) indicators. Environment and Behavior 42: 171–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, Lawrence, Jacqueline Kerr, Dori Rosenberg, and Abby King. 2010. Health aging and where you live: Community design relationship with physical activity and body weight in older Americans. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 7: S82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, Andrew, and Ernie Kroeger. 2013. The highline as an experience: Comparing the value of a constructed artifact to the more ephemeral guided walk. The International Journal of Critical Cultural Studies 10: 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibem, Eziyi Offia, and Egidario B. Aduwo. 2013. Assessment of residential satisfaction in public housing in Ogun State, Nigeria. Habitat International 40: 163–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Yu-Min. 2020. Megacity Seoul: Urbanization and the Development of Modern South Korea. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Joung, You Jin. 2014. An Empirical Analysis on the Importance of Neighborhood Relations and Spatial Characteristics: Focused on the Family Life Cycle. Ph.D. thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

- Jun, Hee-Jung, and Misun Hur. 2015. The relationship between walkability and neighborhood social environment: The importance of physical and perceived walkability. Applied Geography 62: 115–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalipour, Hesam, Armin Jeddi Yeganeh, and Mehran Alalhesabi. 2012. Predictors of place attachment in urban residential environments: A residential complex case study. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 35: 459–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jae-Ik, and Jin-Hwi Kwon. 2009. The Effects of the Inner City Decline on Living Conditions and Land Use: The Case of Daegu Metropolitan City. Housing Studies Review 17: 95–115. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Haksic, and Ji Hoon Lim. 2017. SPSS 24 Manual. Seoul: JypHyunJae Publishing Co. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Hee Chang, Hee-Bong Park, and Woo Il Jung. 2004. An analysis on the factors to affect the settlement consciousness of in habitants. The Korean Association for Policy Studies 13: 147–67. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Kyung-Young. 2020. Factors Influencing the Community Livability among the Younger Working-Age Population in Small and Medium Sized Cities: Focusing on Public Service Satisfaction, Local Government Trust, and Regional Differences. Ph.D. thesis, Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul, Korea. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka, Maria. 2011. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? Journal of Environmental Psychology 31: 207–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, Hollie. 2002. Pedestrian environments and sense of community. Journal of Planning Education and Research 21: 301–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Kangrae. 2017. The Hit List of Local Cities. Seoul: Kaemagowon Publishing Co. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Marans, Robert W. 2003. Understanding environmental quality through quality of life studies: The 2001 DAS and its use of subjective and objective indicators. Landscape and Urban Planning 65: 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marans, Robert, and Robert J. Stimson. 2011. Investigating Quality of Urban Life Theory, Methods, and Empirical Research. Social indicators research series; New York and Dordrecht: Springer, vol. 45, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Lina, John Short, and Marianella Ortíz. 2015. Citizen satisfaction with public goods and government services in the global urban south: A case study of Cali, Colombia. Habitat International 49: 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam-Webster. 2017. Livability. Available online: http://www.merriam-webster.com (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. 2018. Guideline for Urban Regeneration New-Deal Projects. Sejong: Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Mohit, Mohammad Abdul, Mansor Ibrahim, and Young Razidah Rashid. 2010. Assessment of residential satisfaction in newly designed public low-cost housing in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Habitat International 34: 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Ha-Ni, Choul-Gyun Chai, and Na-Kyoung Song. 2018. Analysis of the effect of perceived neighborhood physical environment on mental health. Seoul Studies 19: 87–103. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

- Mouratidis, Kostas. 2018. Built environment and social well-being: How does urban form affect social life and personal relationships? Cities 74: 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, Kostas. 2020. Commute satisfaction, neighborhood satisfaction, and housing satisfaction as predictors of subjective well-being and indicators of urban livability. Travel Behaviour and Society 21: 265–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, Peter W. G. 1999. Sustainability and cities: Extending the metabolism model. Landscape and Urban Planning 44: 219–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, Lorraine Nadia, Brijesh Thapa, and Yong Jae Ko. 2009. Residents’ Perspectives of a World Heritage Site: The Pitons Management Area St. Lucia. Annals of Tourism Research 36: 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzian-Maleki, Saeid, Simon Bell, Seyed-Bagher Hosseini, and Mohsen Faizi. 2015. Developing and testing a framework for the assessment of neighbourhood liveability in two contrasting countries: Iran and Estonia. Ecological Indicators 48: 263–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, Robin, and Dogan Gursoy. 2012. Residents’ support for tourism. An Identity Perspective. Annals of Tourism Research 39: 243–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2011. OECD Framework for Measuring Well-Being and Progress. Measuring Well-Being and Progress. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Okulicz-Kozaryn, Adam. 2011. City life: Rankings (livability) versus perceptions (satisfaction). Social Indicators Research 110: 433–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, Lars E., Tommy Gärling, Dick Ettema, Margareta Friman, and Satoshi Fujii. 2015. Happiness and satisfaction with work commute. Social Indicators Research 111: 255–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Wei, Boyi Wang, Li Tian, and Xinyi Niu. 2017. Spatial deprivation of urban public services in migrant enclaves under the context of a rapidly urbanizing China: An evaluation based on suburban Shanghai. Cities 60: 436–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, Doruk Görkem, and Serap Yilmaz. 2019. The effects of physical and social attributes of place on place attachment: A case study on Trabzon urban squares. Archnet-IJAR 13: 133–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Kyungjun, and Seongwoo Lee. 2015. Determinants of housing expenditure in Seoul Metropolitan area, 2006–2014: Application of multi-level model. The Korea Spatial Planning Review 87: 33–48. (In Korean). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, Matt. 2020. Revitalization, transformation and the ‘Bilbao effect’: Testing the local area impact of iconic architectural developments in North America, 2000–2009. European Planning Studies. Published Online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehdanz, Katrin, and David Maddison. 2008. Local environmental quality and life-satisfaction in Germany. Ecological Economics 64: 787–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth, Matthias, and Rachel S. Franklin. 2014. Livability for all? Conceptual limits and practical implications. Applied Geography 49: 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifried, Chad, and Aaron W. Clopton. 2013. An alternative view of public subsidy and sport facilities through social anchor theory. City, Culture and Society 4: 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. 2013. 2013 Village Community Project [White Paper]; Seoul: Seoul Metropolitan Government. Available online: http://opengov.seoul.go.kr/paper/1101154 (accessed on 23 November 2020). (In Korean)

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. 2015. A Strategy of Urban Regeneration 2025 [White Paper]; Seoul: Seoul Metropolitan Government. Available online: https://uri.seoul.go.kr/surc/archive/policyView.do?bbs_master_seq=POLICY&bbs_seq=511 (accessed on 23 November 2020). (In Korean).

- Statistics Korea. n.d. 2010–2019 Population Census. Available online: https://kosis.kr/index/index.do (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Szopińska, Kinga. 2019. Sustainable urban transport and the level of road noise: A case study of the city of Bydgoszcz. Geomatics and Environmental Engineering 13: 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Li, Francis K.W. Wong, and Eddie C.M. Hui. 2014. Residential satisfaction of migrant workers in China: A case study of Shenzhen. Habitat International 42: 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmer, Vanessa, and Nola-Kate Seymoar. 2006. The Livable City. Vancouver Working Group Discussion Paper, the World Urban Forum 2006. Vancouver: UN Habitat–International Centre for Sustainable Cities. [Google Scholar]

- Ujang, Norsidah, Amine Moulay, and Khalilah Zakariya. 2015. Sense of well-being indicators: Attachment to public parks in Putrajaya, Malaysia. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 202: 487–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Lisa, Tya Shannon, Max Bulsara, Terri Pikora, Gavin McCormack, and Billie Giles-Corti. 2008. The anatomy of the safe and social suburb: An exploratory study of the built environment, social capital and residents’ perceptions of safety. Health and Place 14: 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Dongsheng, Mei-Po Kwan, Wenzhong Zhang, Jie Fan, Jianhui Yu, and Yunxiao Dang. 2018. Assessment and determinants of satisfaction with urban livability in China. Cities 79: 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Wenzhong, and Xiaolu Gao. 2008. Spatial differentiations of traffic satisfaction and its policy implications in Beijing. Habitat International 32: 437–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).