Can Community-Based Social Protection Interventions Improve the Wellbeing of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in the United Kingdom? A Systematic Qualitative Meta-Aggregation Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Research Aims

3. Inclusion Criteria

3.1. Population

3.2. Intervention

- Semi formal—delivered by formally established and legally recognized non-state institutions and organizations. Examples included trade unions; faith- or community-based organizations; local or national non-governmental organizations; bilateral or multilateral donors.

- Informal—originating from personal relationships such as family, friends, and peers (based on Devereux 2019).

3.3. Comparison and Outcome

3.4. Study Type

4. Methods

4.1. Search Strategy

- (Refugee OR “asylum seek*” OR “forced migra*” OR “forced displa*” OR “without legal status” OR “illegal immigrant” OR “seek* asylum”) AND

- Qualitative AND

- (Voluntary OR volunteer OR occupation* OR “take part” OR involve*) AND

- (Wellbeing OR well-being OR “well being” OR happiness OR identity OR belong* OR integrat* OR “mental health” OR empower* OR welfare OR resilience OR community OR “community-based” OR “community based” OR drop-in OR “sanctuary network” OR “city of sanctuary” OR church OR local OR informal OR “social protection”) AND

- (Publication year > 1999) AND

- (Affiliate country—United Kingdom) AND

- (Language—English)

4.2. Databases

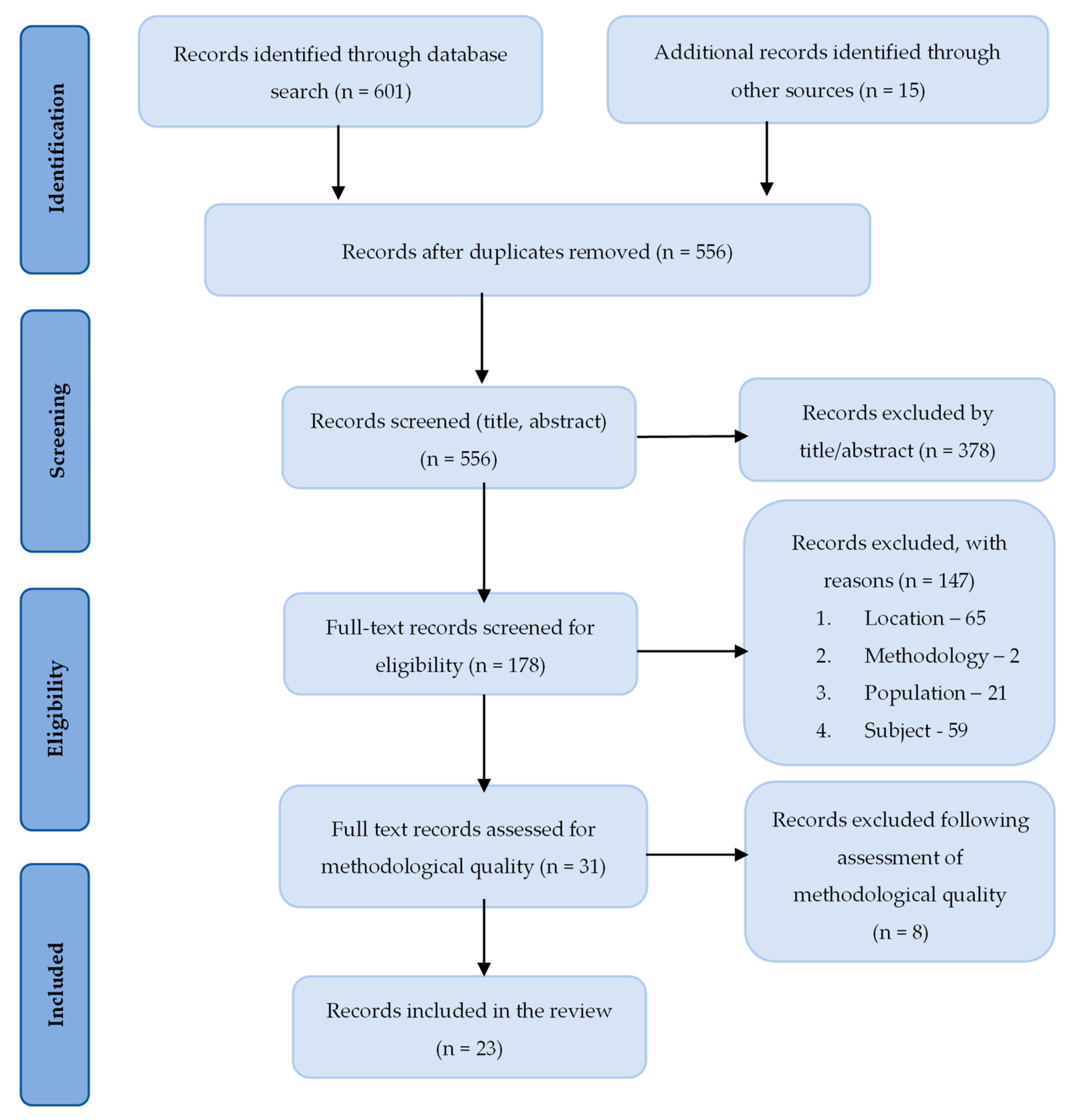

4.3. Selection of Studies

4.4. Methodological Quality Appraisal

4.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

- ‘Extraction of all findings from all studies with an accompanying illustration […] for each finding.

- Developing categories for findings with at least two findings per category.

- Developing one or more synthesized findings of at least two categories’.

- ‘Unequivocal (findings accompanied by an illustration that is beyond reasonable doubt and; therefore not open to challenge)

- Equivocal (findings accompanied by an illustration lacking clear association with it and therefore open to challenge)

- Unsupported (findings are not supported by the data)’ (Lockwood et al. 2015)

4.6. Conceptual Framework for Categorization and Synthesized Findings

5. Results

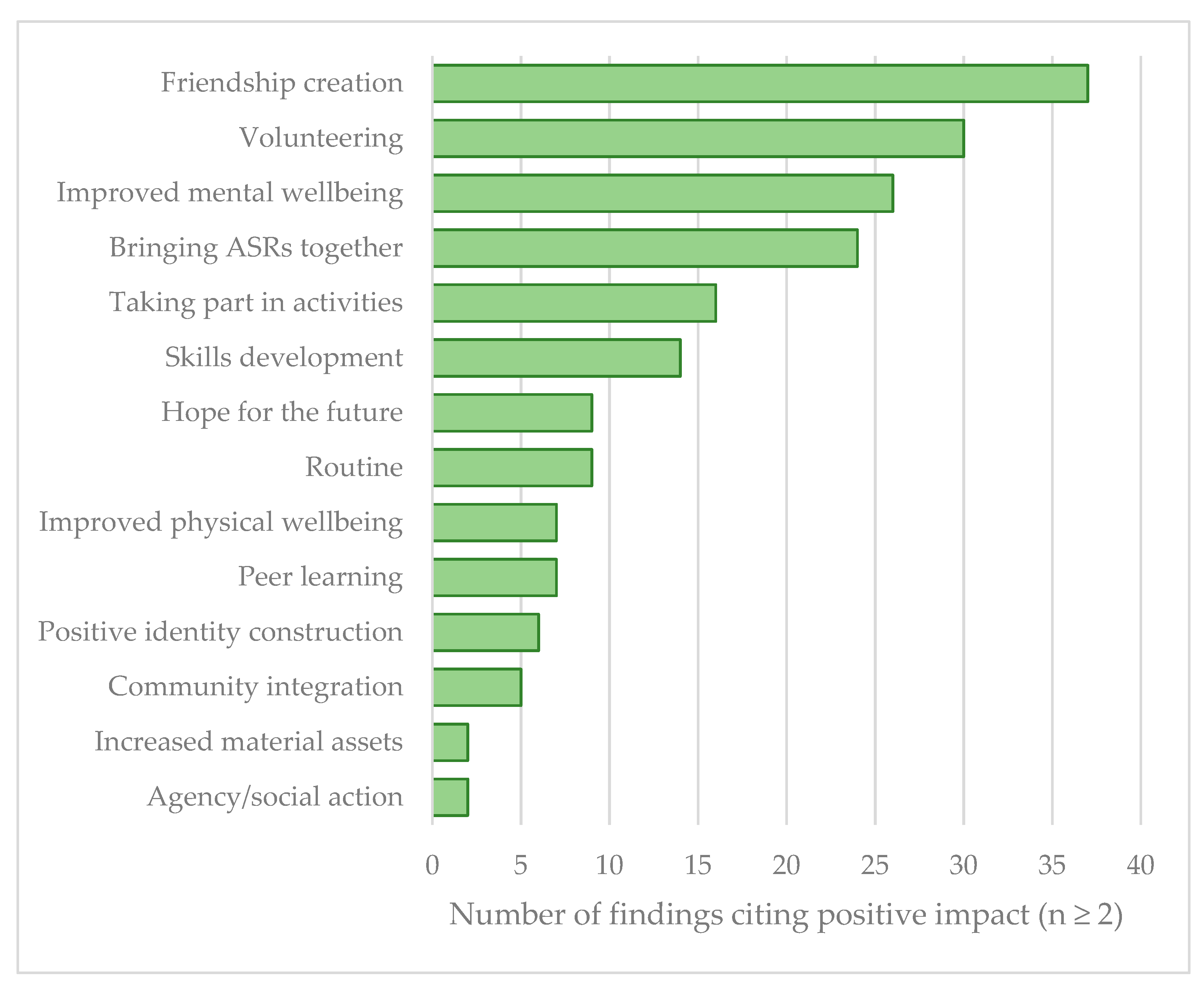

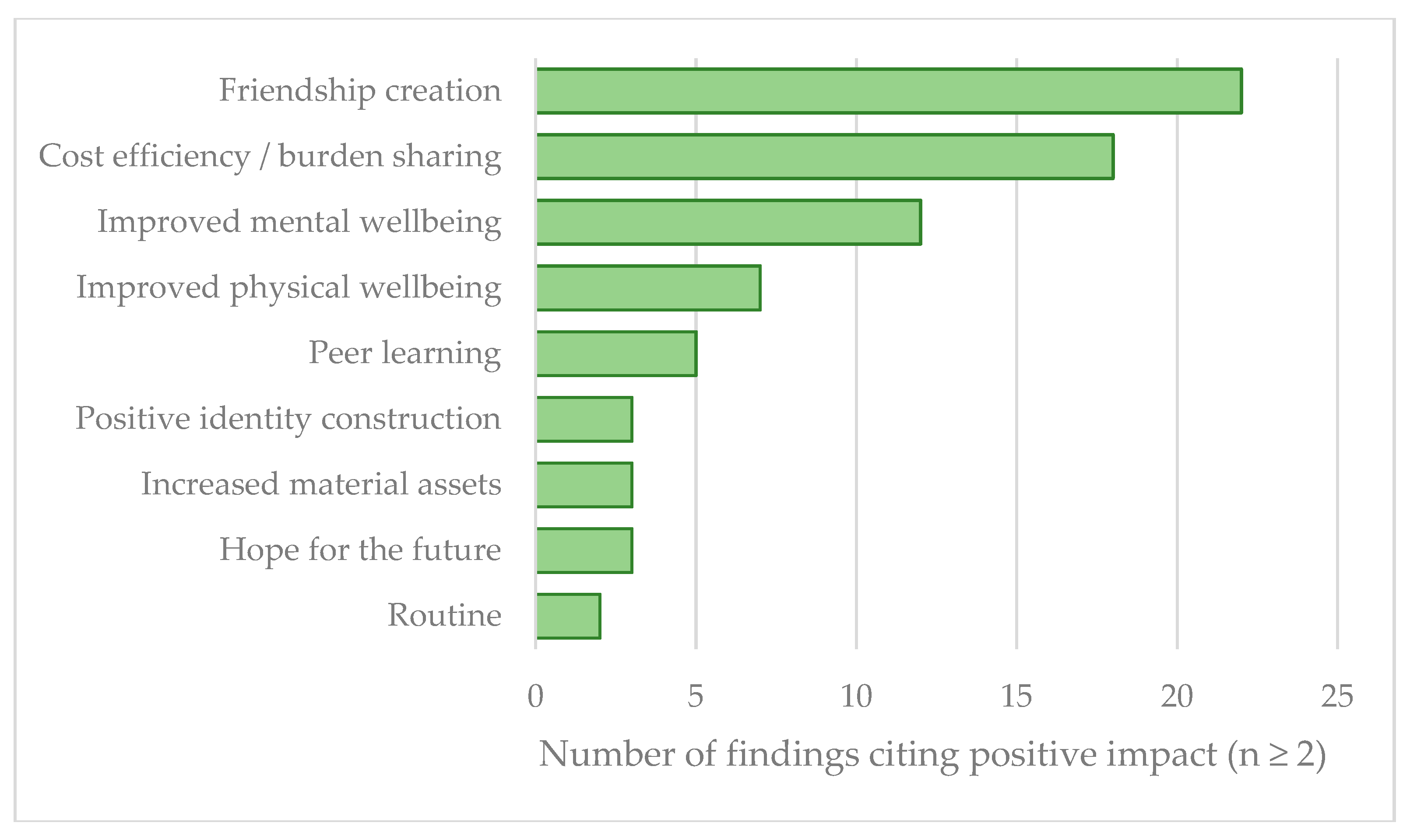

5.1. Synthesized Finding One: The Positive Impact of Volunteering

‘You lose your skills, we are lucky because we have our Karibu [RTSO], I can use the computer, I can use the email, I can read [documents], so it keeps me a bit up doing this voluntary work. Imagine if I did stay 6 years doing nothing, today I would not even be able to even write a letter…’(H, Congolese refugee) (Rosenburg 2008, p. 118)

‘I came in 2002, introduced to the organization by (Education Worker). I helped with Albanian classes, volunteered with them. I have done training, worked in the office. I really found my confidence. I’ve been inspired by them, especially (the Project Manager)’.(SU33, Female, age unknown) (Kellow 2010, p. 112)

‘I like to do volunteering well because I need to build my experience. I need to build my skills, so I’m happy to meet people, talk to them, and then after that, I know how, I have this experience if I get job.(Francine 25–29)’ (Yap et al. 2010, p. 162)

‘It’s easier to talk to somebody who’s been through that process…most of my clients tend to move towards me because I’ve got first-hand experience of going through the system’.(Savannah, Sudanese woman working for a voluntary BME organization) (Hunt 2008, p. 287)

‘People like me when I said to them my status and I am volunteering eh, support me and happy, because you want to work not to stay at home’.(Mohammed 392–4) (Yap et al. 2010, p. 163)

‘British people, they don’t like lazy. So, if you are lazy, you sit, you eat, they don’t like, you need to do it as well. If you are doing good thing, if you hard worker, you are very confident with them, they like you’.(Francine 627–635) (Yap et al. 2010)

‘Mustafa: Through [The Talking Shop] I do some voluntary job, some gardening job and I think that is a small thing to make Sheffield better […] if you have got a home you like your house to be a good house. Sheffield is like house, places like this make you feel like it is house, everyone we are living in the city and you have to do something to make your city better’.(Mustafa interview 2007 in Darling 2011)

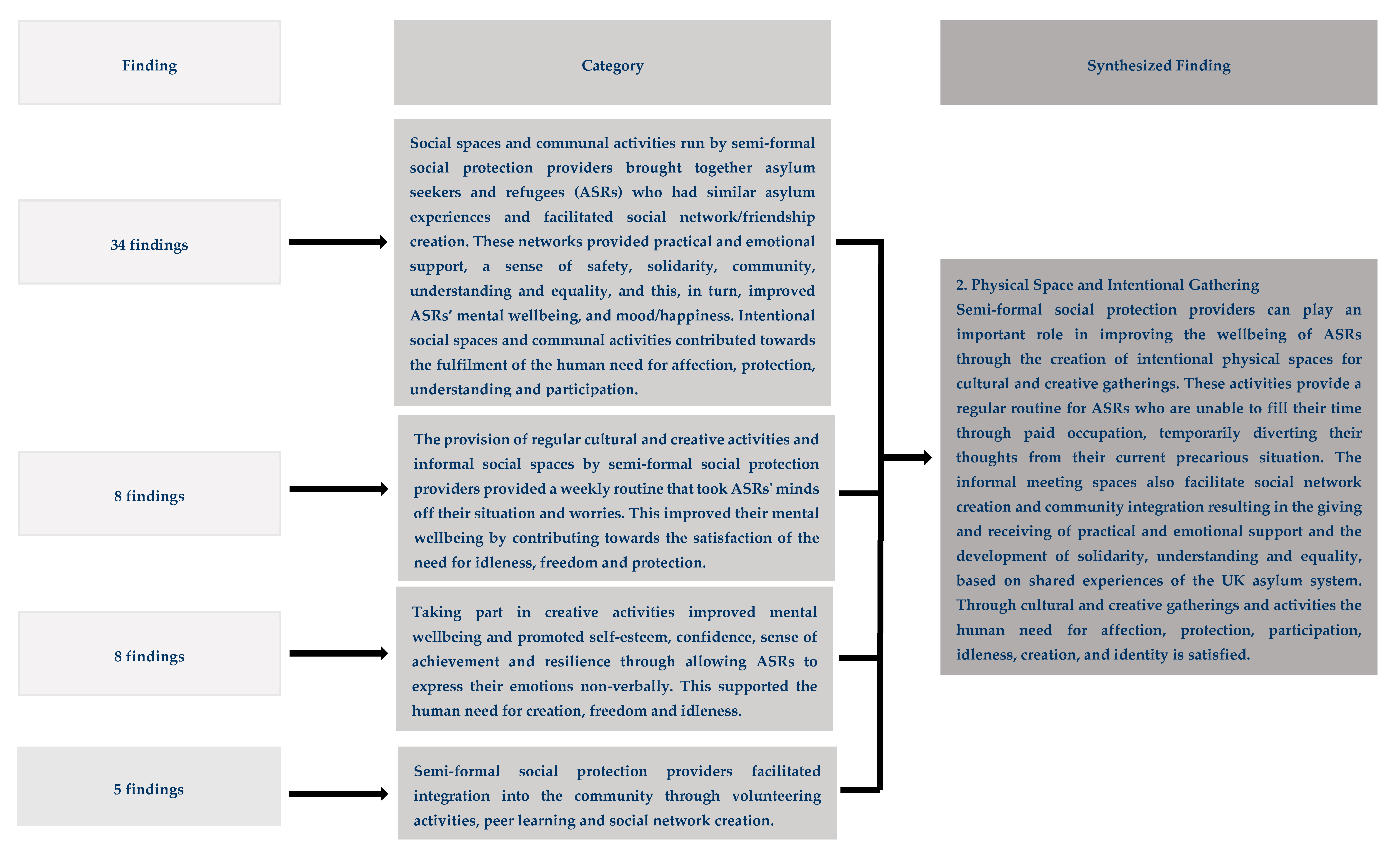

5.2. Synthesized Finding Two: Physical Space and Intentional Gathering

‘I used to come here every day of my life: Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday… because I don’t have anywhere to go, so I just come here, and I attached myself to the groups, we met, we talk, we… then I’ve gone to knit, I’ve gone to do computer, reading, many things I learnt here, so I just like it’.(Unnamed) (Clini et al. 2019, p. 6)

‘Just even to come out of your house and find someone giving you a hug, just loving you, it is really important because you are on your own. These groups help in a way because you meet different people, different cases. A few of them you might access to share your life with them…You get that togetherness. You get that hope to say we are many, we are receiving help, we are learning, it’s all about that. You are not alone’.(Participant 9) (Thompson 2017, p. 52)

‘[…] One thing you have to bear in mind is that I am not working, and I am not studying, you know, so it was the only thing that I would look forward to because it was something to do, otherwise I would just be at home, doing nothing, you know, feeling very sorry for myself, getting upset all the time […]’(Unnamed) (Clini et al. 2019, p. 6)

‘I like this group because when you come here you [do] not think too much (Jessica)’.

‘It is more of expressing, more of letting go, it’s like getting a spirit out of you, and you don’t have necessarily have to tell someone ‘I’ve done this because of that and that, and this’, you know. Because sometimes you just don’t find the voice to talk about it and, I, as a person am really shy and, you know, I feel easily embarrassed, you know. […] So… that’s why I’m into arts, yes I’m doing arts really’.(Unnamed) (Clini et al. 2019, p. 7)

‘If you’re in a situation where you’ve been completely isolated from people for a while and you just don’t know who to trust, or to be around people, it’s one of those spaces where you can get to meet people, socialise, and actually make friends. […] And these friendships do last. A life-time, because you understand what the person has gone through, you don’t have to explain a lot, you know, they just know that you’ve been through something terrible. […]’(Unnamed) (ibid., p. 6)

‘I went for my first time to mix with other refugees and asylum seekers…women especially…it started to draw me out…a bit more confidence, yes, that I had lost’.(Unnamed) (Burchett and Matheson 2010, p. 89)

‘[…] It’s a distraction from immigration and we know we are all going through it, but we don’t have to talk about it. There are other things going on in life, and we talked about, for example in the art group, the works we produced and what we could do, what we could achieve and get inspired by each other’s work’.(Unnamed) (Clini et al. 2019, p. 6)

[Author’s fieldnote including quotation] ‘’Nobody understands you as well as they do’. This was echoed by an interviewee from Afghanistan who said, ‘English people do not know about challenges that refugees face. But the Afghani community can help’.’(Unnamed) (Flug and Hussein 2019, p. 13)

‘[…] It gives me immense happiness to attend the national celebrations of Afghanistan to be in cultural events which remind me of my youth and the good days in Afghanistan. It makes me happy […](H16) (Atfield et al. 2007, p. 41)

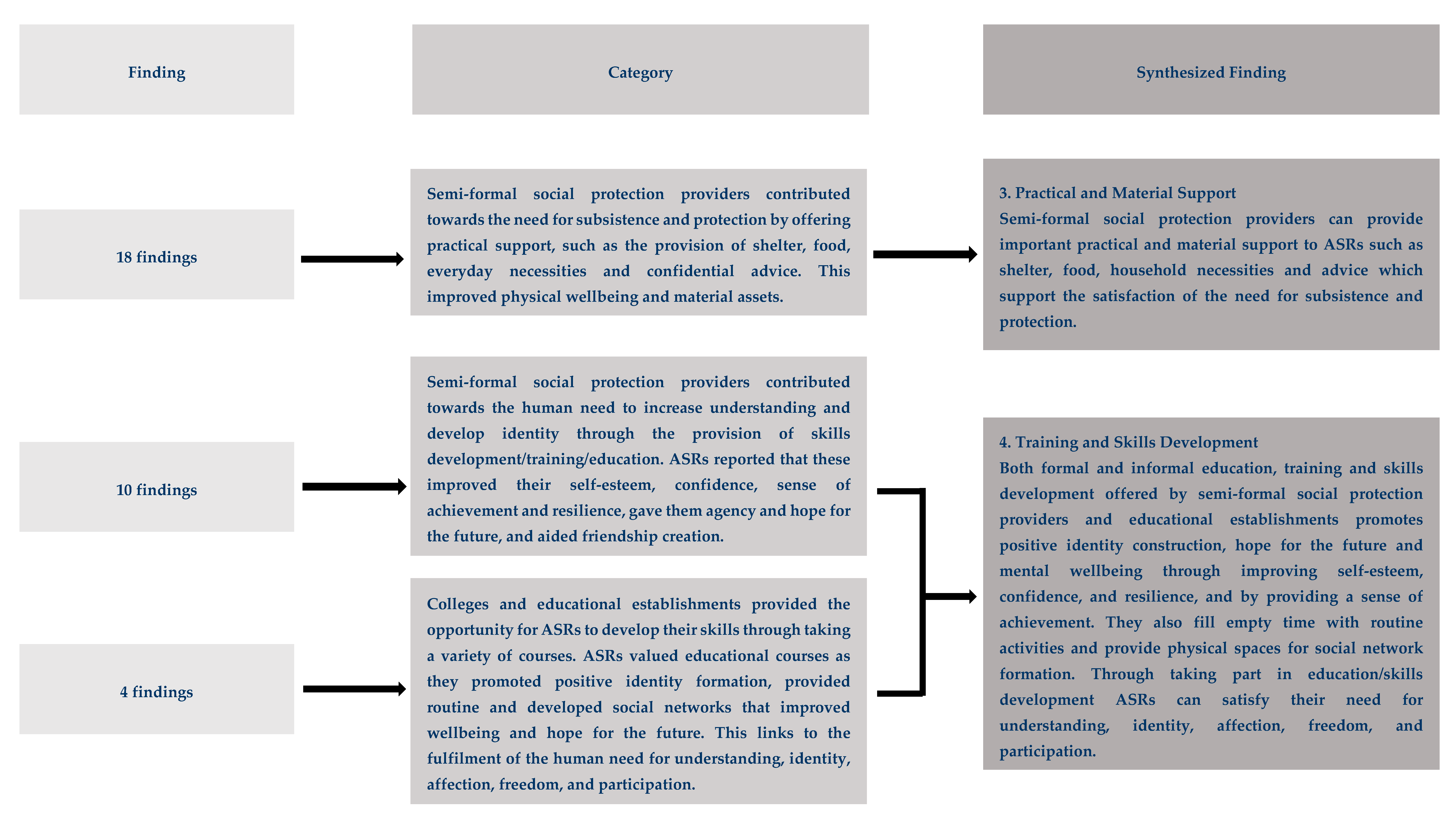

5.3. Synthesized Finding Three: Practical and Material Support

‘I lived 5 years without support. I depended on these local organisations to survive’.(Zena) (Cuthill et al. 2013, p. 12)

‘If these organisations weren’t there, I may have died because the government doesn’t give you any support and we are not allowed to work in this country and we don’t have a place to stay. […]’.(Gibrel) (Cuthill et al. 2013)

‘I’ve got a new flat and got plenty of stuff from here. […] I haven’t got enough money to spend for the kitchen stuff and for example more clothing’.(M7) (Spring et al. 2019, p. 40)

5.4. Synthesized Finding Four: Training and Skills Development

‘When you are in this situation it feels like life has, in a way, stopped. And you can’t do anything to change it. But by doing all this activity you feel, or I felt…it was like, you know, that I was learning something in my life, rather than just waiting. […] For instance, if I go for a job somewhere, where you have to write what skills you have, so I could include all of this. I mean I don’t have a certificate or, like, proper qualifications, but I’ve all those skills, so I feel like, it is, in a way, impressive? Because you feel like, you know, rather than just waiting and not doing anything, you have been learning’.(Unnamed) (Clini et al. 2019, pp. 5–6)

[Author fieldnote] ‘One woman proudly told me how she loved learning and sought out hard courses that she didn’t yet understand but wanted to. In fact, she was hoping to study physics next. She had recently completed her GCSEs and remarked how she always made friends wherever she went, even if she was over thirty years older than the rest of the students!’

‘I learn too many things. For example, if you just sit at home, you get crazy, you know, twenty-four hour a day without nothing. You go college, you just make yourself busy, you know, and you make some friends’.(H8) (Atfield et al. 2007, p. 42)

‘I’m very stressed, I’m always crying as well, I don’t get sleep. But when I start college, I become bigger, better, better. Now, thanks to God, everything’s well and I love my school’.(Unnamed) (Wenning 2018, p. 115)

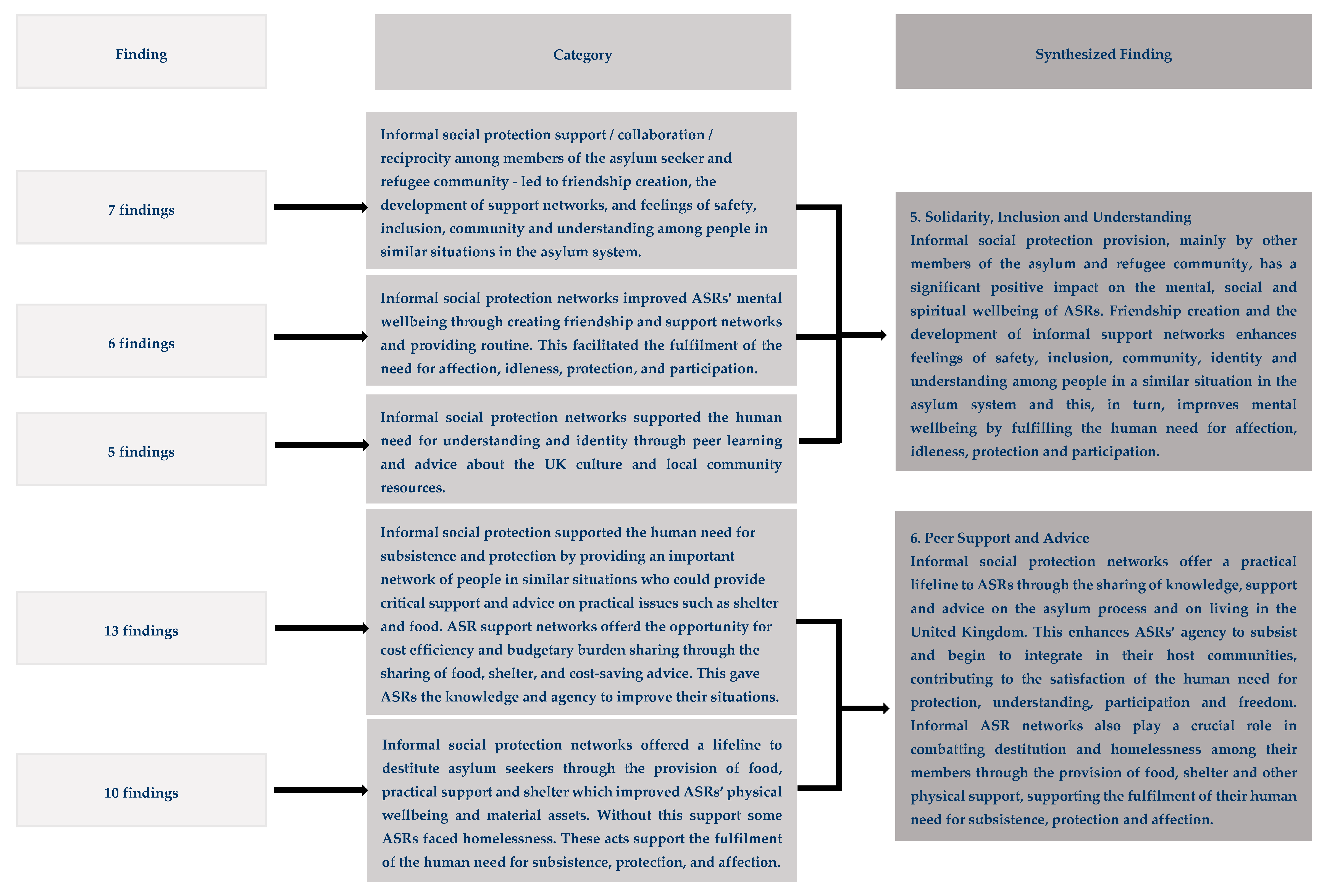

5.5. Synthesized Finding Five: Solidarity, Inclusion and Understanding

‘I arrived in at Heathrow…… I didn’t know anybody or anything; I didn’t even know where the UK was on the map. The only person I could talk to was the interpreter at the Home Office, but he wasn’t friendly. After a few days in the hostel I just needed someone to talk to. I found Albert; he had been in the UK for a few months. We talked and talked. I started to realise that I wasn’t alone, he had similar experiences’.(Pascal, Male 25) (Murray 2015, p. 161)

‘My first day in the hostel was upsetting. I stayed in my room and cried. I knew nothing of where my family was and I knew nothing of my new surroundings. I was the only African in my hostel. The second night a Kurd from Iraq took me by the hand and led me to another room. In the room were other Kurds eating a meal. They gave me food and made me feel welcome. I became friends with one of the Kurds who spoke French as he had lived in Lebanon’.(Serge, Male 29) (Murray 2015)

[Author’s fieldnote including quotation] ‘Being a refused asylum seeker effectively made her homeless. Yet she became close with some church members who invited her to stay with them in Newcastle. Because there was no other alternative available at the time, she accepted the offer. She was now a very active member in that church. ’I thank God for those people,’ she told me, ‘because also they push me to do things that I would not usually do, like standing in front of people, or even like giving an announcement, I would never do that but she [friend she lives with] just pushes me like, ‘Go, do it!’’.

5.6. Synthesized Finding Six: Peer Support and Advice

‘I became friends with a Somali man who was much older than me. We communicated in Swahili. He treated me like his younger brother. He took me to the local college to register for English classes. He also took me to his solicitor so that I could get legal help. We spent most of our time together, and I made a lot of friends through him. Life became easier as I now had friends to talk to and I felt more confident living in the hostel’.(Ibis, Male 22) (Murray 2015, p. 162)

‘The community helps me. I get counselling from them I get advices and financial help’.(Congolese woman, 28) (Goodson and Phillimore 2006, p. 8)

‘Serge [asylum seeker] is very busy but I think that it gives him something to do. He is always calling people and arranging when we can meet as a group. If someone has a problem he always knows someone who can help’.(Dada, Female 28) (Murray 2015, p. 178)

[Author fieldnote including quotation] ‘His closest friend, and someone he considered as part of his family, was a man around his age who took him into his home and looked after him. This man fed him and even gave him a room of his own. This bond between them has given Yasir new hope. ‘That’s my family. And when you see good people and help you and that, look after you, you feel like there’s good people in this world. It’s not the people [who are bad but] the system’.’

‘Destitution is a culturally sensitive issue. Pride and tradition mean you can’t leave people to sleep on the streets. You’re obliged to help them’.(Representative, Nuba Mountains Welfare Association) (Lewis 2007, p. 25)

‘When I was in Bradford I received notice from the Home Office that my application had been turned down. I didn’t know what to do, I contacted a friend in Ilford. They invited me to stay with them. I was there for nearly two years, staying on people’s floors […]’(Joseph, Male 40) (Murray 2015, p. 233)

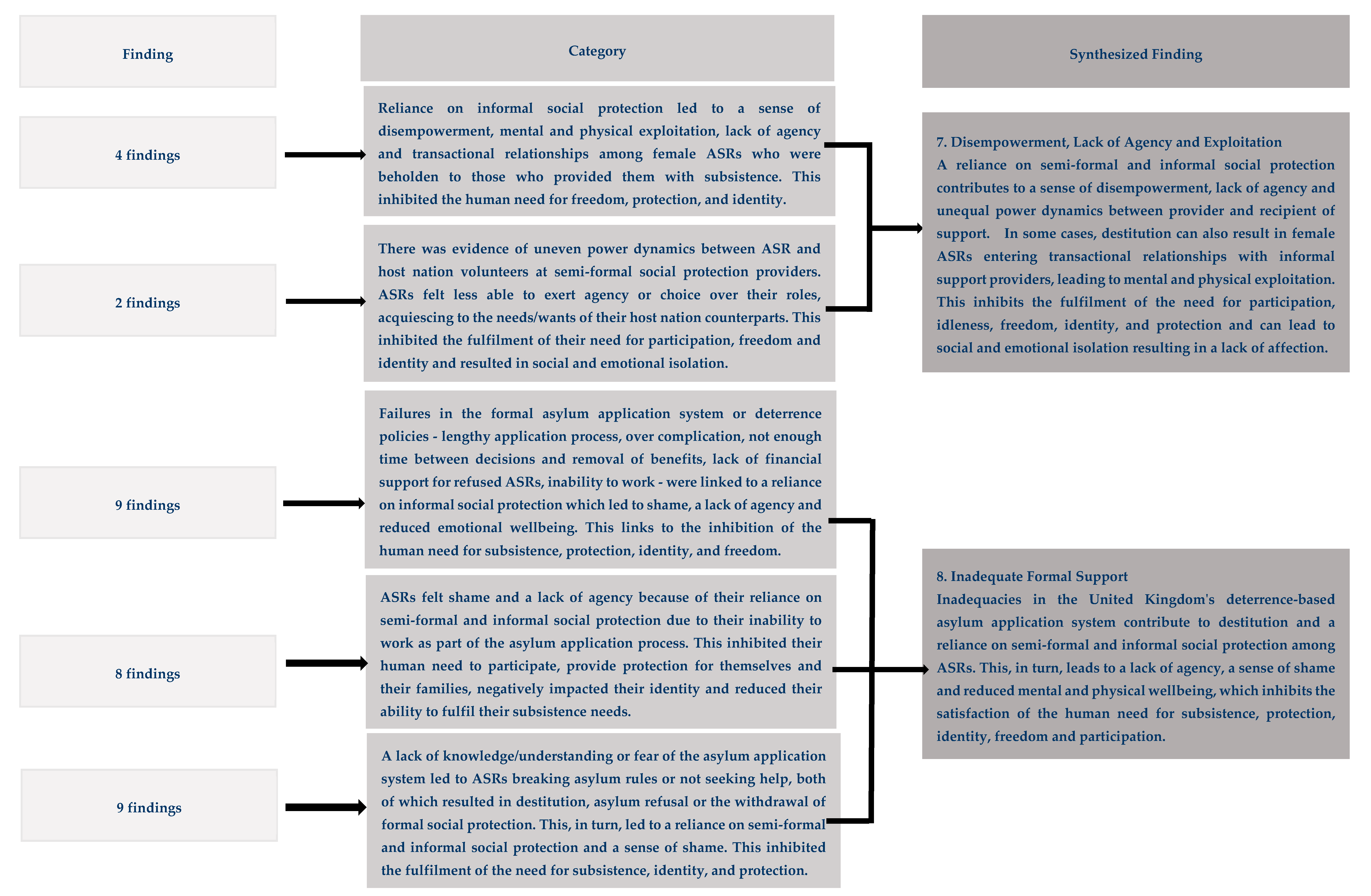

5.7. Synthesized Finding Seven: Disempowerment, Lack of Agency and Exploitation

[Author fieldnote] ‘[…] I go over to the kitchen to get a cup of tea. After a brief chat with Ilya and Shariq I reach the counter to see not Akan, but two elderly ladies stationed there. They ask me politely if I want tea or coffee […] I turn to look around the room for Akan and note that he’s sat talking with a few other men at a round table, none of them have a drink (Research diary, 27 April 2007). Following this incident I attended The Talking Shop on Friday, where Akan was back to his usual routine, and his usual place. While he arranged some saucers I asked him why he was not doing the teas on Wednesday, he told me that the two ladies were there when he arrived, that they were volunteers from the church and that he did not feel that he could say anything about the tea making being his ‘role’. After this Akan stopped making the teas on Wednesday as the two ladies became a regular fixture, and after a while stopped attending on Wednesdays altogether, his role had been taken, his position of brief and fragile ownership had shifted in the face of two volunteers who also wanted to ‘give something back’’.

[Fieldnote] ‘Magda lives in NASS accommodation without paying rent, despite her asylum claim being refused, since developing a sexual relationship with the property’s owner. He is an old man, by whom she feels neither threatened nor coerced. She has two other boyfriends, both local residents though not originally from the UK, who provide Magda with her other needs, such as clothing and money. […]’

[Fieldnote] ‘Djany faced destitution after her claim was refused and she was told to leave her NASS accommodation, leaving all her belongings behind apart from her toothbrush. She had nowhere to go, so routinely spent evenings in pubs, looking for a man to take her home that night, just so she could have a place to stay. […]’

5.8. Synthesized Finding Eight: Inadequate Formal Support

‘Our culture is to work…not to sit back and let someone else to feed you. It has destroyed my life, waiting for others to feed me. I have always worked, since I was a young man, I have worked’.(Osman) (Cuthill et al. 2013, p. 13)

‘I have an ARC card which I take to the Post Office to get my money. A couple of times it hasn’t worked. I called my support officer who said it will take a few days to get it sorted out. I once had to wait three weeks! The support officer has said that there is nothing he can do to help until the money comes through. He told me to ask my friends to help until things were sorted out’.(Claude, Male 26) (Murray 2015, p. 230)

‘Most of them don’t go to find advice because they’re scared, there is no trust. […] I went once, to Refugee Action to get help, but when they asked me about my address, I was scared, and gave them the wrong address, and after that I didn’t go back to them’.(Unnamed) (Crawley et al. 2011, p. 31)

[Discussion about a Food Bank] ‘It is a feeling of death […] Believe me it felt so awful that my legs were shaking […] They were very kind people and smiling all the time but still you feel terrible. We refugees like me and you were not poor people in our countries, we just had to escape from death to survive. But you don’t believe how terrible I felt, standing in the queue in coldness for a bag of food’.(Hossain, Iranian, M) (Mayblin et al. 2020, p. 114)

‘I have saved all my mail but I don’t understand what it says. I went to the Refugee Centre once so they could translate the document for me. I waited nearly all morning to see someone. I felt embarrassed and never went back. There were so many letters that I just gave up after a while, I never opened them and put them in a cupboard’.(Dax, Female 30) (Murray 2015, p. 245)

6. Findings

7. Implications for Practice, Policy and Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Asylum seekers can apply to work if they have been waiting over 12 months for an initial decision, through no fault of their own, and only if the applicant can take up a skilled position listed in the UK’s shortage occupation list. Voluntary work is also permitted. There are no statistics available on numbers of asylum seekers working at this time. |

| 2 | ‘[A]dult asylum seekers who are ‘appeal rights exhausted’ and people categorized by the Home Office as ‘immigration offenders’’ are banned from undetaking formal study (Right to Remain 2018). For higher education puposes, asylum seekers are classed as international students. |

| 3 | Accurate funding cut figures for asylum and refugee voluntary service providers are not available at this time. However, research has suggested an annual reduction figure of 7.7% for all voluntary and community sector income from central and local government in the period 2015–2016. |

References

- Atfield, Gaby, Kavita Brahmbhatt, and Therese O-Toole. 2007. Refugees Experiences of Integration. Hong Kong: Refugee Council. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, Linda, Sin Yi Cheung, and Jenny Phillimore. 2016. The Asylum-Integration Paradox: Comparing Asylum Support Systems and Refugee Integration in The Netherlands and the UK. International Migration 54: 118–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaam, Marie-Clare, Carol Kingdon, Gill Thomson, Kenneth Finlayson, and Soo Downe. 2016. ‘We make them feel special’: The experiences of voluntary sector workers supporting asylum seeking and refugee women during pregnancy and early motherhood. Midwifery 34: 133–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhatia, Monish. 2015. Turning Asylum Seekers into ‘Dangerous Criminals’: Experiences of the Criminal Justice System of those Seeking Sanctuary. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 4: 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bishop, Ruth, and Elizabeth Purcell. 2013. The value of an allotment group for refugees. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 76: 264–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchett, Nicole, and Ruth Matheson. 2010. The need for belonging: The impact of restrictions on working on the well-being of an asylum seeker. Journal of Occupational Science 17: 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, Mary, and A. Azim El Hassan. 2003. Between NASS and a Hard Place. London: The Housing Association Charitable Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Clini, Clelia, Linda J. M. Thomson, and Helen J. Chatterjee. 2019. Assessing the impact of artistic and cultural activities on the health and well-being of forcibly displaced people using participatory action research. BMJ Open 9: e025465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CoS. 2020. City of Sanctuary UK. Available online: https://cityofsanctuary.org/ (accessed on 22 November 2020).

- Crawley, Heaven, Joanna Hemmings, and Neil Price. 2011. Coping with Destitution: Survival and Livelihood Strategies of Refused Asylum Seekers Living in the UK. Swansea: Oxfam. [Google Scholar]

- Cuthill, Fiona. 2017. Repositioning of ‘self’: Social recognition as a path to resilience for destitute asylum seekers in the United Kingdom. Social Theory & Health 15: 117–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cuthill, Fiona, Omer Siddiq Abdalla, and Khalid Bashir. 2013. Between Destitution and a Hard Place: Finding Strength to Survive Refusal from the Asylum System: A Case Study from North-East England. Sunderland: U.O. Sunderland. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren, Goran, and Margaret Whitehead. 2015. European Strategies for Tackling Social Inequalities in Health: Levelling Up, Part 2. World Health. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Darling, Jonathan. 2010. A city of sanctuary: The relational re-imagining of Sheffields asylum politics. Transactions-Institute of British Geographers 35: 125–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, Jonathan. 2011. Giving space: Care, generosity and belonging in a UK asylum drop-in centre. Geoforum 42: 408–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, Stephen. 2019. Comprehensive Social Protection: Understanding the Roles of Formal, Semi-Formal, Informal and Private Providers 2019 GW4 Social Protection Sandpit Event, University of Bath, UK. Brighton: Centre for Social Protection, Institute of Development Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Fell, Benedict, and Peter Fell. 2013. Welfare across Borders: A Social Work Process with Adult Asylum Seekers. The British Journal of Social Work 44: 1322–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, Suzanne, Glen Bramley, Janice Blenkinsopp, Sarah Johnsen, Mandy Littlewood, Gina Netto, Filip Sosenko, and Beth Watts. 2015. Destitution in the UK: An Interim Report. York: Rowntree Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Flug, Matthias, and Jason Hussein. 2019. Integration in the Shadow of Austerity—Refugees in Newcastle upon Tyne. Social Sciences 8: 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goodson, Lisa Jane, and Jenny Phillimore. 2006. Social Capital and Integration: The Importance of Social Relationships and Social Space to Refugee Women. The International Journal Diversity in Organisations, Communities and Nations 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannes, Karim, and Craig Lockwood. 2011. Pragmatism as the philosophical foundation for the Joanna Briggs meta-aggregative approach to qualitative evidence synthesis. Journal of Advanced Nursing 67: 1632–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, Lisa. 2008. Women Asylum Seekers and Refugees: Opportunities, Constraints and the Role of Agency. Social Policy and Society: A Journal of the Social Policy Association 7: 281–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kellow, Alexa. 2010. Refugee Community Organisations: A Social Capital Analysis. Ph.D. thesis, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Hannah. 2007. Destitution in Leeds. J.R.C. Trust. Available online: www.jrct.org.uk (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Linton, Myles-Jay, Paul Dieppe, and Antonieta Medina-Lara. 2016. Review of 99 self-report measures for assessing well-being in adults: Exploring dimensions of well-being and developments over time. BMJ Open 6: e010641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, Craig, Zachery Munn, and Kylie Porritt. 2015. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13: 179–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, Abraham H. 1970. Motivation and Personality, 2nd ed. New York and London: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Max-Neef, Manfred A. 1991. Human Scale Development: Conception, Application and Further Reflections. New York and London: The Apex Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mayblin, Lucy. 2014. Asylum, welfare and work: Reflections on research in asylum and refugee studies. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 34: 375–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayblin, L., and P. James. 2019. Asylum and refugee support in the UK: Civil society filling the gaps? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45: 375–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mayblin, Lucy, Mustafa Wake, and Mohsen Kazemi. 2020. Necropolitics and the Slow Violence of the Everyday: Asylum Seeker Welfare in the Postcolonial Present. Sociology 54: 107–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McDonald, Iain, and Peter Billings. 2007. The Treatment of Asylum Seekers in the UK. The Journal of Social Welfare & Family Law 29: 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, Joann. 2007. ‘Joining the BBC (British Bottom Cleaners)’: Zimbabwean Migrants and the UK Care Industry. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 33: 801–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, Morrison, Andra Julie Polisena, Don Husereau, Kristen Moulton, Michelle Clark, Michelle Fiander, Monika Mierzwinski-Urban, Tammy Clifford, Brian Hutton, and Danielle Rabb. 2012. The effect of English-language restriction on systematic review-based meta-analyses: A systematic review of empirical studies. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 28: 138–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, Fraser. 2015. Sent to Coventry: The Role Played by Social Networks in the Settlement of Dispersed Congolese Asylum Seekers. Ph.D. thesis, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Navacchi, Mandy, and Craig Lockwood. 2020. Perceptions and experiences of nurses involved in quality-improvement processes in acute healthcare facilities: A qualitative systematic review protocol. JBI Evidence Synthesis 18: 2038–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, Martha C. 2011. The Central Capabilities. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, pp. 17–45. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2009. Promoting Pro-Poor Growth: Employment. O. Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/greengrowth/green-development/43514554.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Parker, Sam. 2015. ‘Unwanted Invaders’: The Representation of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the UK and Australian Print Media, eSharp 23. Cardiff: Cardiff University. [Google Scholar]

- Pettitt, Jo. 2013. The Right to Rehabilitation for Survivors of Torture in the UK. London: Freedom from Torture. [Google Scholar]

- Price, Jonathan. 2016. Meeting the Challenge: Voluntary Sector Services for Destitute Migrant Children and Families. Oxford, UK. Available online: https://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/PR-2016-Meeting_the_Challenge.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Refugee Council. 2020. Number of People Waiting more than Six Months for Their Asylum Claim to Be Processed Surges by 68%. London: Refugee Council, Available online: https://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/latest/news/number-of-people-waiting-more-than-six-months-for-their-asylum-claim-to-be-processed-surges-by-68/ (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Refugee Council. 2004. Hungry and Homeless: The Impact of the Withdrawal of State Support on Asylum Seekers, Refugee Communities and the Voluntary Sector. London: Refugee Council. [Google Scholar]

- Right to Remain. 2018. Home Office Drops Study Ban for Under-18s and Some Adults. London: Right to Remain, Available online: https://righttoremain.org.uk/new-immigration-provisions-are-resulting-in-sudden-study-bans/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Robeyns, Ingrid, and Morten Fibieger Byskov. 2020. The Capability Approach. Stanford University. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2020/entries/capability-approach/ (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Rosenburg, Alexandra. 2008. The Integration of Dispersed Asylum Seekers in Glasgow. Ph.D. thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, Carol D. 1989. Happiness Is Everything, or Is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57: 1069–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rylko-Bauer, Barbara, and Paul Farmer. 2016. Structural Violence, Poverty, and Social Suffering. In The Oxford Handbook of the Social Science of Poverty. Edited by David Brady and Linda Murton. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Amartya. 1985. Commodities and Capabilities. Amsterdam: North-Holland. [Google Scholar]

- Seppala, Emma, Timothy Rossomando, and James Doty. 2013. Social Connection and Compassion: Important Predictors of Health and Wellbeing. Social Research: An International Quarterly 80: 411–30. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Phillip B., and Manfred A. Max-Neef. 2011. Economics Unmasked: From Power and Greed to Compassion and the Common Good. Cambridge: Green Books. [Google Scholar]

- Spring, Hannah C., Fiona KHowlett, Claire Connor, Ashiton Alderson, Joe Antcliff, Kimberley Dutton, Olivia Gray, Emily Hirst, Zebe Jabeen, Myra Jamil, and et al. 2019. The value and meaning of a community drop-in service for asylum seekers and refugees. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care 15: 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturge, Georgina. 2019. Asylum Statistics. London: House of Commons Library. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Chris. 2017. Developing our Knowledge of Resilience: The Experiences of Adults Seeking Asylum. Ph.D. thesis, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK. [Google Scholar]

- UN. 2015a. Policy integration in government in pursuit of the sustainable development goals. Paper presented at Expert Group Meeting, New York, NY, USA, January 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- UN. 2015b. Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In A/RES/70/1. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Peter William. 2019. Migration to the UK: Asylum and Resettled Refugees. Oxford: The Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Wenning, Briamme. 2018. ‘Most of the Days is Really, Really Good’: Narratives of Well-Being and Happiness among Asylum Seekers and Refugees in the UK and the Gambia. Ph.D. thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Yap, Su Yin, Angela Byrne, and Sarah Davidson. 2010. From Refugee to Good Citizen: A Discourse Analysis of Volunteering. Journal of Refugee Studies 24: 157–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Peer-Reviewed Databases | Grey Literature Database (Theses, Dissertations, Government and Third-Sector Reports) |

|---|---|

| Scopus | British Library: Social Welfare Centre for the Analysis of Social Exclusion OpenGrey (theses only) Refugee Studies Centre, Oxford University |

| International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS) | |

| JSTOR | |

| Web of Science: all databases | |

| EBSCO Open Dissertations | |

| EThOS | |

| APA PsycNET | |

| PTSDpubs | |

| Ovid—(Social Policy and Practice) | |

| Third Sector Research Centre (TSRC) | |

| Campbell Systematic Reviews | |

| Cochrane Library | |

| EPPI-Centre Knowledge Library |

| Human Need | Examples |

|---|---|

| Subsistence | Food, shelter, work, physical health, procreation |

| Protection | Family, work, social protection, health care |

| Affection | Friendships, intimacy, togetherness, family, self-esteem, tolerance |

| Understanding | Study, communication, curiosity, critical conscience |

| Participation | Rights, work, responsibilities, affiliation, interaction |

| Idleness | Imagination, free time, relaxation, peace of mind |

| Creation | Skills, design, passion, determination, autonomy, inventiveness |

| Identity | Sense of belonging, language, customs, integration, social rhythms |

| Freedom | Equal rights, choice, autonomy, self-esteem, self-determination, tolerance |

| Human Needs | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsistence | Protection | Affection | Understanding | Participation | Idleness | Creation | Identity | Freedom | ||

| Synthesized Findings | ||||||||||

| 1 | Semi-formal SP: The Positive Impact of Volunteering | Satisfier | Satisfier | Satisfier | Satisfier | Satisfier | Satisfier | |||

| 2 | Semi-formal SP: Physical Space and Intentional Gathering | Satisfier | Satisfier | Satisfier | Satisfier | Satisfier | Satisfier | |||

| 3 | Semi-formal SP: Practical and Material Support | Satisfier | Satisfier | |||||||

| 4 | Semi-formal SP: Training and Skills Development | Satisfier | Satisfier | Satisfier | Satisfier | Satisfier | ||||

| 5 | Informal SP: Solidarity, Inclusion and Understanding | Satisfier | Satisfier | Satisfier | Satisfier | |||||

| 6 | Informal SP: Peer Support and Advice | Satisfier | Satisfier | Satisfier | Satisfier | Satisfier | ||||

| Human Needs | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsistence | Protection | Affection | Understanding | Participation | Idleness | Creation | Identity | Freedom | ||

| Synthesized Findings | ||||||||||

| 7 | Inadequate Formal Social Protection | Inhibitor/Destroyer | Inhibitor/Destroyer | Inhibitor/Destroyer | Inhibitor/Destroyer | Inhibitor/Destroyer | ||||

| 8 | Disempowerment, Lack of Agency and Exploitation | Inhibitor/Destroyer | Inhibitor/Destroyer | Inhibitor/Destroyer | Inhibitor/Destroyer | Inhibitor/Destroyer | Inhibitor/Destroyer | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

James, M.L. Can Community-Based Social Protection Interventions Improve the Wellbeing of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in the United Kingdom? A Systematic Qualitative Meta-Aggregation Review. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10060194

James ML. Can Community-Based Social Protection Interventions Improve the Wellbeing of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in the United Kingdom? A Systematic Qualitative Meta-Aggregation Review. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(6):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10060194

Chicago/Turabian StyleJames, Michelle L. 2021. "Can Community-Based Social Protection Interventions Improve the Wellbeing of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in the United Kingdom? A Systematic Qualitative Meta-Aggregation Review" Social Sciences 10, no. 6: 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10060194

APA StyleJames, M. L. (2021). Can Community-Based Social Protection Interventions Improve the Wellbeing of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in the United Kingdom? A Systematic Qualitative Meta-Aggregation Review. Social Sciences, 10(6), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10060194