1. Introduction

Research on school bullying among preschoolers and primary school grades is still very scarce (

Machimbarrena and Garaigordobil 2018). Bullying is currently regarded as a complex group phenomenon in which the aggressor’s or aggressors’ main goal is to achieve a certain position of power within the group. Accordingly, the analysis of group dynamics is taken to be a key issue for fully understanding the phenomenon since it is the group which assigns each member´s status. For that reason, group members need to witness or be somehow informed of the acts of aggression carried out. In short, violent behaviour is a means towards the end of achieving greater power and status (

Menesini and Salmivalli 2017). Other contextual variables have been documented to play a key role in understanding these specific types of peer conflicts, such as teachers´ relationships with their students (

Donat et al. 2018).

Much is already known about this phenomenon, such as the existence of different roles (

Salmivalli et al. 1996), the places and contexts where this kind of aggression is most likely to occur (

Ombudsman-UNICEF 2000,

2007), and the truly dramatic consequences it might entail, especially for the victims (

Garaigordobil et al. 2014). Such consequences are even more worrying bearing in mind the prevalence of estimates indicating that between 5 and 20% of schoolchildren, depending on the study, may be victims of school bullying (

Machimbarrena and Garaigordobil 2018).

One outcome of this considerable research effort has been significant progress in understanding and preventing bullying at school (

Menesini and Salmivalli 2017). Nevertheless, two particular areas have received far less attention in current research.

First, there has been little in-depth analysis of this kind of aggressive behaviour during preschool and the first years of primary school (

Huitsing and Monks 2018). There are some important differences between the bullying pattern of aggression displayed by younger students compared to adolescents, namely the victim´s role tends to be quite unstable and peripheral roles, such as assistants, reinforcers, and defenders, are harder to identify. This suggests that peer victimisation is more dyadic and less of a group process among younger children than it is among older students (

Monks et al. 2021). Likewise, the bully victim role seems to be more common (

Alsaker 2018), and other-sex aggression might be more frequent, since groups of peers at an early age are not so sex segregated compared to adolescents (

Rose and Smith 2018). Despite this, there are also important similarities between preschool and adolescent bullying dynamics, such us victims show a low status and boys tend to display more direct forms of aggression than girls (

Monks and Smith 2010). Finally, similar to adolescents, whether the aggressor´s status is high or low is still a pending issue to be disentangled, which probably depends on complex contextual variables (

Huitsing and Monks 2018).

As a result, there is no consensus on the crucial issue as to whether or not it is technically appropriate to refer to these acts of aggression specifically as “bullying” per se in connection with these early school years. At the time of writing, there are two quite distinct views on this point. Some authors argue that the term “bullying” is not strictly applicable and that it is better to conceptualize these acts as “unjustified aggression” (

Monks 2012). Others, on the contrary, maintain the stance that the term can be used in its full sense in relation to those age groups (

Alsaker 2018).

Secondly, less attention has been paid to the analysis of the meanings attached to this phenomenon or to the social network in which these negative behaviours take place. One exception to this trend is the research of

Huitsing and Monks (

2018) who interviewed 177 students from 5 to 9 years old and concluded that aggressors in early childhood are less selective in their choices than in adolescence, as preschool victims tend to be dominant and secure. Furthermore, a same-sex defenders’ pattern of behaviours was found.

Similarly,

Monks et al. (

2021), in an observational study of 56 children aged four to five years old, have also documented that sex differences were observed in types of aggression displayed by children, with boys more likely to than girls to be physically aggressive. Likewise, children were less likely to be aggressive with other-sex peers and were most likely to be victimised by children of the same sex as them.

In line with this methodology,

Almeida et al. (

2001) and

Del Barrio et al. (

2003) interviewed 120 subjects between the ages of 9 and 15 by means of a narrative tool, SCAN-bullying. The SCAN presents 10 images portraying a prototypical story of bullying in which a group of schoolchildren perpetrate different acts of aggression (physical aggression, blackmail, damage to personal belongings, etc.) against another schoolmate. Two of this study’s most significant findings were (i) the high frequency with which the respondents used the term bullying to refer to these kinds of aggressive acts and (ii) the attribution of feelings to the bullies and the victims, respectively, of delight and pride, or of sadness, shame, and fear. On the other hand,

Menesini et al. (

2003) used the same tool with 179 subjects between the ages of 9 and 13 and concluded that in comparison with victims and witnesses, bullies experienced higher levels of indifference or pride before the various acts of aggression suffered by the victim. These, among other works of research, provide an opportunity to carry out detailed analysis of how students understand this kind of negative experience among peers.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

The sample was composed of 120 subjects aged between 5.44 and 9.58 years old (mean: 7.27; SD: 1.15), from kindergarten to third grade. All of these schoolchildren were middle class and native Spanish speakers, as they were all born in Spain, though their parents had different backgrounds, namely 76.7% (n = 92) of students were from Spain, 15.8% (n = 19) from Romania, 1.7% (n = 2) from Poland, 1.7% (n = 2) from the Dominican Republic, and 4.2% (n = 5) from other countries. They were all recruited from three public mainstream schools in a midsize town (200,000 inhabitants) located in the east part of the Community of Madrid. Among those students whose guardians provided active consent to participate in the study, simple affix, random stratified sampling was carried out. This resulted in 30 children being interviewed in each of the four school grades with an equal number of boys and girls in each year group.

3.2. Instruments

The study used SCAN-bullying as previously reported by

Almeida et al. (

2001) and

Del Barrio et al. (

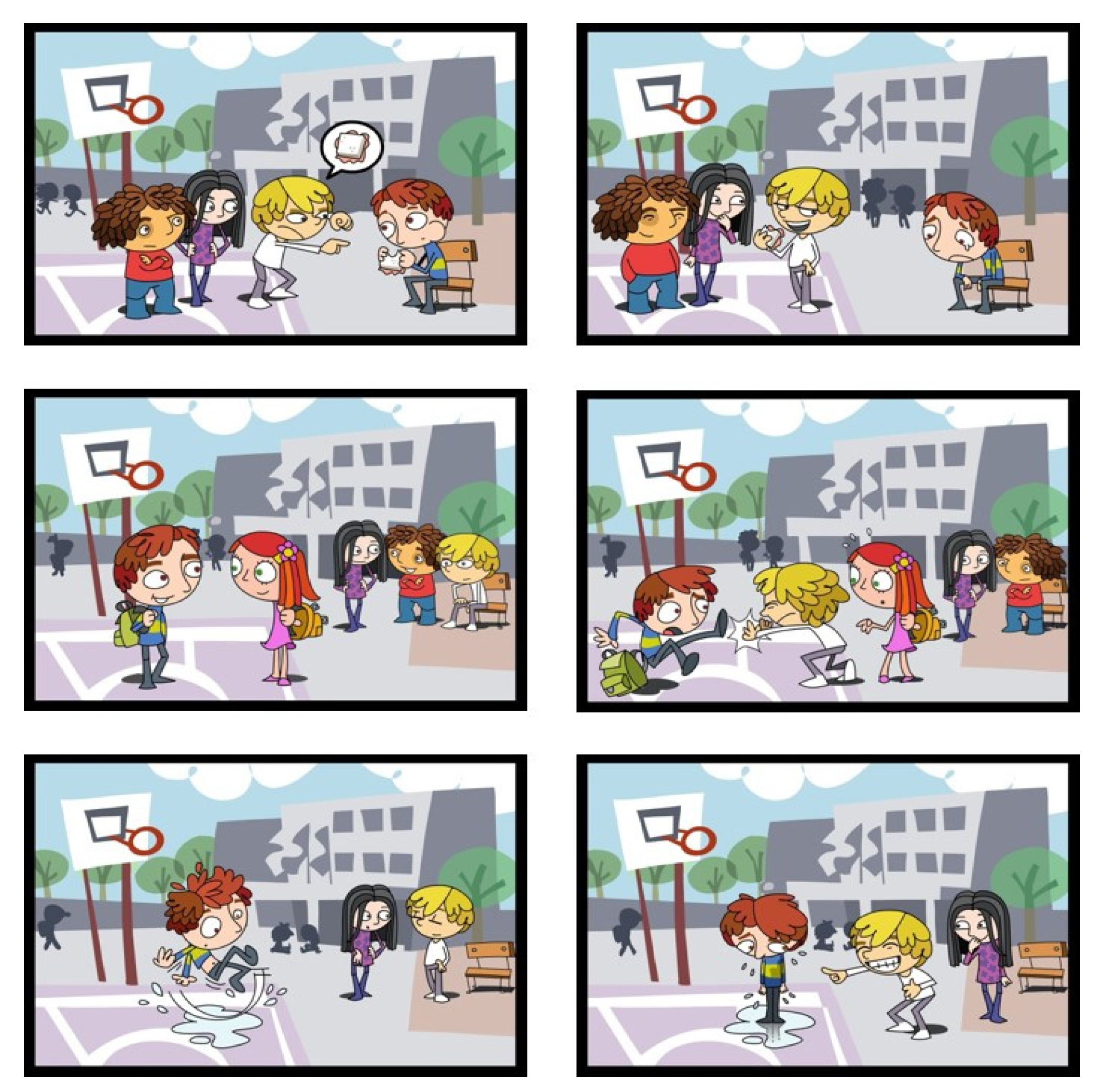

2003), but with adaptations appropriate to the developmental features of the current sample. The adjustments made were as follows: the physical appearance of the characters was made appropriate to schoolchildren of kindergarten and primary school age and the faces were made easy to distinguish. The cartoons were also coloured, and the different scenes of abuse were depicted in comic strip format (

Figure 1). Two sets of cartoons were designed: in one, the main characters (victim and bully) were boys, in the other, girls. One or other of the sets was used according to whether the interviewee was male or female in order to increase identification with the story depicted.

The complete set of pictures was composed of five comic strips, each comprising two 12 × 7.5-cm panels depicting different kinds of abuse; these were direct and indirect social exclusion, direct or indirect physical abuse, blackmailing, and making fun. At the start of the story, a single vignette showed the victim lining up with the other children—the bully, the assistants, and the bystanders—looking on.

Vocabulary and grammatical adjustments were also made to the semistructured interview used in the original study, that is, language was kept simple to make it easier for the age groups to understand the conversation, while taking care at all times to maintain the meaning of the original questions. Each interview took 15 ± 2 min approximately.

3.3. Design and Procedure

A pilot study was carried out to check whether the changes made to the original SCAN-bullying, the questions as selected, and their phrasing were suited to the sample’s developmental characteristics. To that end, a total of 13 subjects were interviewed, as follows: three from kindergarten (2 boys and 1 girl), four from 1st grade (2 boys and 2 girls), four from 2nd grade (2 boys and 2 girls), and two from 3rd grade (2 boys). We checked that the comprehension of the pictures, the questions asked, and the interest aroused by the tool were shown to be adequate for the purposes of the research.

Secondly, the headteacher of each school was contacted by the research team and informed of the research goals and proposed methodology. Once they had agreed to participate, the school sent out a letter notifying parents and requesting their active consent. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki: informed consent, right to information, protection of personal data, guarantees of confidentiality, nondiscrimination, no charge, and the possibility of abandoning the study in any of its phases.

The schoolchildren were all interviewed individually in a separate room on school premises. All interviews were carried out by the first author, a professional with an MD in Psychology and a degree in Special Education, with more than 10 years of experience working with students of this age in a mainstream school. The schoolchildren’s own permission was sought to make audio recordings of the conversations, which always commenced with the interviewer introducing himself and explaining his interest in knowing how the children do in their school. The examiner then showed the pictures one at a time by laying them on a table. If the child had a query about any picture, s/he could ask the interviewer, who would reply as neutrally as possible to avoid bias in their responses. Once all the pictures had been shown, the interview began, following a pre-established order of questions with adaptations as necessary to help it flow as naturally as possible.

3.4. Data Analysis

Once the 120 interviews forming part of the actual research had been completed, each interview was transcribed literally, and the answers were classified into preliminary categories on the basis of previous reports by

Almeida et al. (

2001) and

Del Barrio et al. (

2003). Then, the responses were reclassified in order to improve the first classification, thereby creating a group of exhaustive and mutually exclusive categories. For the second classification, 20% of the interviews were chosen at random from each year and for each gender for analysis by a second expert; high levels of agreement between first and second experts (Kappa coefficient between 0.63 and 1) were obtained. For hypothesis checking, the chi-square proportion test was used, with

p values below 0.05 being regarded as statistically significant.

4. Results

We set out the results obtained for these five questions: (a) whether schoolchildren at these ages recognise the distinctive elements of peer abuse, (b) what they think causes it, (c) whether they think peer abuse is the outcome of previous conflicts between victim and aggressor, (d) what emotions schoolchildren attribute to victim and aggressors, and (e) what coping strategy they would use to resolve a case of school bullying if they were the victims.

4.1. Type of Aggression

In order to define the type of aggression the schoolchildren perceived in the story depicted, they were asked: “What would you say is happening in this story? What’s the matter with these children?” When classifying the responses, the whole of the interview was taken into account to see whether reference was made to such distinguishing features of peer abuse as power imbalance, reiteration, and intention. The analysis showed that 94.2% of the interviewees identified the scenes as prototypical situations of bullying. In contrast, the answers of 5.8% of the schoolchildren contained no simultaneous references to the three distinguishing features, so their responses were included in the category one-off acts of aggression.

No significant differences (

p = 0.697) were found as a function of gender, but significant differences were found (

p = 0.017) as a function of school grade, with interviewees from kindergarten giving more responses classified as

one-off aggressions than the other three groups as we can see in

Figure 2.

4.2. Causes of Bullying

To analyse the reasons the subjects suggested to account for this kind of conflict, they were asked, “Why do you think these things happen at school?” A total of 37.5% answered that the bullies were to blame for these acts of aggression; the bullies were described as bad pupils who had fun hitting other children. This response was included in the category bullies’ personality. A total of 21.7% said that the bullies did not have a good relationship with the victim, a response included in the category chemistry, and 22.5% gave only vague, uninformative answers or freely admitted that they were unaware of the motives. Other significantly less frequent answers were that the victim was a new pupil at the school (2.5%) or had low self-esteem (2.5%), a response included in the category victim’s personality. When the replies were analysed as a function of the gender and grade variables, no statistically significant differences were found (p = 0.399 and p = 0.119, respectively), although as far as grade is concerned, some interesting but nonsignificant tendencies were noticed.

Figure 3 shows that more than half of the kindergarten children’s responses explaining these kinds of conflicts fell within the

bullies’ personality category; that is, the bullies are naughty and enjoy hitting other children. In contrast, the main reason according to the 2nd grade children was that the bullies did not have a good relationship with the victim, a response in the

chemistry category.

4.3. Existence of Antecedents

When asked, “Do you think these children get on like this now because something might have happened between them in the past?”, 53.9% of the children answered that something had happened between the victim and the bully, while 34.7% did not think so; 8.7% claimed not to know the answer (

No answer/Do not know category). There were no significant differences as a function of grade (

p = 0.116), but there were for gender (

p = 0.003), as can be seen in

Figure 4, with girls (69%) being more disposed than boys (38.6%) to believe there had been some previous conflict between the victim and the aggressors.

Among the 53.9% of the children who responded affirmatively to the existence of antecedents, the most commonly stated reasons were that there had been some previous confrontation, with no mention of its direction, that is to say, no mention of who—victim or bully—was believed to have started the confrontation. More specifically, 33.9% of the children gave this reply, 27.4% suggested that the victim had previously bullied the bullies, and 11.3% answered that something had gone on previously between victim and bullies, but they could not specify what; a response included in the category No answer/Do not know. Other significantly less frequent responses were that the victim and the bullies were not friends (3.2%), that there had been some previous rivalry between them (3.2%), or simply that they were previously on bad terms (1.6%). Finally, 19.4% gave ambiguous, uninformative answers.

When the replies were analysed as a function of gender or school grade, no statistically significant differences were found (

p = 0.277 and

p = 0.092, respectively), but once again, some tendencies were noticed. By looking at

Figure 5, in comparative terms, first grade schoolchildren showed a greater tendency (61.5%) to mention the existence of some previous conflict, albeit with no indication of direction, than those from the other three grades. In contrast, at 40%, third grade children were most likely to answer that the victim had done something previously to annoy the bullies. Finally, kindergarten children gave the more frequent

ambiguous answers.

4.4. Emotional Attributions

When pointing at the victim, the children were asked, “How do you think this boy/girl feels?” A total of 85.4% answered sad. Other emotions mentioned, though far less frequently, were angry with the bullies (3.4%), upset (1.7%), humiliated (1.7%), or lonely (1.7%). To the question “Why do you think s/he feels that way?”, 74% replied that it was because of being bullied, followed at a great distance by other answers such as s/he cannot play (13%) or s/he has no friends (4.3%).

In answer the question (pointing at the victim) “How would you feel if what was happening to the boy/girl happened to you?”, 82.5% said they would feel the same, that is, sad, followed at a great distance by other emotions such as angry with the bullies (3.4%), upset (0.9%), disappointed (0.9%), hurt (0.9%), guilty (0.9%), frustrated (0.9%), or ungrateful (0.9%). When accounting for those emotional states, 75.1% said they would feel that way because of being bullied, 12.9% because they could not play, and 5.2% because they would have no friends.

In answer to the question (pointing at the bullies) “How do you think these children feel?”, 72% said they felt happy and 15.3% that they were angry with the victim. Other emotions mentioned much less frequently were guilty (1.7%), angry with themselves (0.8%), or satisfied (0.8%), among others. When accounting for the bullies’ emotions, 51.3% of the children alluded to their bullying of the victim, 15.5% said they felt that way because they could play, and another 5.2% said it was because they had friends.

Finally, when asked “How would you feel if you treated one of your schoolmates that way”?—in other words, if they took the role of the bully—56.6% answered sad, 17.1% guilty, 17.1% happy, and 4.3% angry with themselves. Other feelings mentioned far less frequently were hurt (0.9%), gutted (0.9%), or angry with the victim (0.9%), among others. When they had to express the reasons accounting for their feelings in the role of the bullies, 75.9% of the children referred to their bullying to the victim, 5.2% said it was because they do not let the victim play, and 3.4% because they would lose friends.

When the different answers were analysed as a function of gender, no statistically significant differences were found for any of the questions (

p = 0.637), but for “How would you feel if you treated one of your schoolmates that way”, there were for school grade, particularly in relation to the reasons given by the children to explain their emotions when putting themselves in the victim’s place (

p = 0.047).

Figure 6 shows that kindergarten children made most mention of the reason

they would not be able to play or

No answer/Do not know. For their part, the third grade schoolchildren answered that

they would have no friends with significantly greater frequency than the other grades.

4.5. Coping Strategies

As for the question (pointing to the victim) “What would you do if what is happening to this boy/girl happened to you?”, 53.8% of the children answered that they would tell the teacher, 13.4% would speak directly to the bullies to try to come to an understanding (reply category: assertiveness), 11.8% would confront the bullies, and 6.7% would make friends with other children (category: alternative friendships). Much less frequent answers were avoiding the bullies (3.4), ignore them (3.4%), or forgive them (2.5%).

When the answers were analysed from the point of view of gender, we found no statistically significant differences (

p = 0.254), although some interesting but nonsignificant observations were detected.

Figure 7 shows that the solution involving telling the teacher what had happened was more frequent, though not significantly, among boys (66.1%) than girls (41.7%). Additionally, the girls proposed a wider range of solution strategies than the boys.

No statistically significant differences were found for grade (

p = 0.133), although some interesting but statistically nonsignificant observations were detected, namely (a) that the first grade schoolchildren were those who most opted for

telling the teacher and (b)

assertiveness was found to increase gradually from grade to grade before falling back in third grade. These two tendencies can be clearly seen in

Figure 8.

No statistically significant differences were found for grade (p = 0.133), although some interesting but statistically nonsignificant observations were detected, namely (a) that the first grade schoolchildren were those who most opted for telling the teacher and (b) assertiveness was found to increase gradually from grade to grade until falling back in third grade.

5. Discussion

Results show that most students from 5 to 9 years old were able to identify the scenes depicted by the adapted SCAN-bullying as a bullying conflict, although kindergarten students were less able to categorize the scenes this way. This is partially consistent with our first hypothesis, which stated that most students would classify the scenes as bullying behaviours.

We are inclined to think that preschoolers have more difficulties interpreting the scenes depicted as bullying behaviours mainly due to their short experiences in school contexts, but specially because of their socio-cognitive developments which impact on their social understanding. Five-year-old students’ abilities to construct mental representations of the world in general and of social relationships in particular are still very limited. They have just started to use first order theory of mind representations, a cognitive ability that normally flourishes at the age of 4–5 years and allows human beings to understand the mental states of others (

Berger 2020). Moreover, in order to have a deep understanding of bullying as a group process, far more complex representations are needed in order to consider other peers´ intentions, motives, and states of mind. We think there is one key additional cognitive ability still missing in five-year-old children that might account for our results: a second order theory of mind, which allows children to understand mental representations about other peers´ mental representations; in other words,

I think that Mary thinks that Jane knows that… This cognitive ability is a key skill needed to deeply understand bullying, which is an attempt to gain social status within the peer group (

Monks et al. 2021), as it allows bullies to understand the impact on the bystanders´ feelings and thoughts about the victims’ feelings and thoughts while being bullied. When a bully is victimizing a classmate, he or she is sending a subtle message to the other classmates, letting them know who is in charge. A second order theory of mind, which is achieved around six years of age, is a key component for this indirect, complex, and extraordinarily symbolic form of communication.

Additionally, an interpretation of this kind might also account for additional features of preschoolers’ and early primary school students´ social networks when compared with those of older students. It is well established that friendship groups and dominance hierarchies are less stable at these early ages. Consequently, the nature and extent of peer victimization do not involve the wider peer group as has been described for adolescents, with peripheral roles, such as assistants, reinforcers, and defenders, being hard to identify (

Monks and Smith 2010). In other words, bullying aggressions tend to be more dyadic than in middle childhood and adolescence. Likewise, these young students are not as sex segregated as in older ages (

Rose and Smith 2018); whether or not this has an impact in terms of the same-sex or other-sex orientated patterns of aggression shown is still unclear (

Monks et al. 2021).

Likewise, the main causation to understand these kinds of peer conflicts was that bullies enjoy hurting others, or they pick on somebody with whom they do not have a good relationship with. In relation with what we have called the

existence of antecedents, more than 50% of the interviewees, especially among girls, thought that there had been a previous confrontation between the victim and the bully. The fact that girls tend to think in this manner more often than boys is noteworthy. In other words, girls find it hard to understand that some peers can pick on other classmates with no apparent reason. This result can be, at least, partially explained by the fact that girls tend to be more prosocial than boys. It is well documented that when talking about bullying roles, girls tend to be overrepresented among defenders (

Monks and Smith 2010). Moreover, girls engage less in rough-and-tumble play, competitive activities, and physical aggressions than boys; likewise, conversation and disclosure are more common among girls (

Rose and Smith 2018). This difference in typical behaviours in social situations may lead girls to look for other reasons to account for this type of aggression.

Nearly 85% of students can recognize the victims´ emotions of sadness, and 74% of them would feel the same way if they were undergoing a similar situation. When justifying their emotions, although kindergarteners and third graders provided statistically significantly different answers from each other, namely, I could not play and I had no friends, respectively, we are inclined to think that both responses underlie the same thought: loneliness. Furthermore, they would feel sad or guilty if they treated a schoolmate in such a manner: in other words, if he or she were to bully a schoolmate. This can be interpreted as a further confirmation that peers from a very early age can understand bullying and its severe negative consequences. These results all together confirm our second hypothesis, as we predicted that most students would sympathize with the victim and condemn the bullies.

As a main coping strategy, it has been documented that more than 50% of the students of our sample, if they suffered from being bullied, would report it to their schoolteachers. This result confirms our third hypothesis, as we stated that most students would ask for help from their schoolteachers if they underwent bullying. However, we must admit that we expected a higher proportion of students to mention this alternative. Bearing in mind the young age of the students who have been interviewed in our study, we have reported a surprisingly wide variety of coping strategies, such as talking directly to the bullies to try to address the conflict, confronting them, or looking for alternative friendships, among others.

The reported data are consistent with those obtained by other research available.

Almeida et al. (

2001) found that most students could recognize the victim´s feeling of sadness and suffering and consequently could sympathize with him/her and condemn the aggressor´s behaviour. These results are coherent with developmental psychology which shows that, at the early age of three, children are able to perceive harm done to other persons (

Clemente-Estevan et al. 2013). Therefore, the first implication of our study for education is this early recognition should be exploited as a first step towards promoting awareness among preschool and school children towards providing them with effective strategies of prevention and for dealing with it efficiently.

As for the reasons which lead a pupil or group of children to use this sort of violence against others, our results are also equivalent to those obtained by

Del Barrio et al. (

2003), whose interviewees attributed the cause of bullying: (a) to characteristics of the bullies—who enjoy hurting others—or (b) to characteristics of the victim—who possesses some physical or psychological characteristic which makes them easy targets. These data can be interpreted as showing that, in the opinion of the schoolchildren, responsibility for aggressive conduct lies exclusively either with the bully or with the victim. Although it has been documented that, for instance, overweight and obese students tend to be overrepresented both among the victims and aggressors (

Lv et al. 2020), it is also well established that there are a number of contextual variables which play an active role in the genesis of this peer aggression (

Donat et al. 2018). Consequently, a second practical implication could be that intervention schemes should make it plain that peer aggression has a marked contextual component, the upshot of which is that ultimately all children are potential victims. Whether or not they become victims can depend, for example, on the role played by the bystanders. An approach of this kind would enhance the awareness of schoolchildren and of the whole educational community, thereby achieving the prosocial intervention of the previously passive bystanders in the event of any hypothetical bullying situation (

Van der Ploega et al. 2017).

Regarding the

existence of antecedents, our finding is consistent with

Del Barrio et al. (

2003), who found that most of their students thought that these specific kinds of peer conflicts are

by-products of previous confrontations among victims and bullies. It must be emphasized that this reasoning, which views bullying behaviours as the outcome of actions carried out by the victim against the bullies, could lead the bystanders to hold victims responsible for the aggressions inflicted on them. If this belief is widespread, it is much harder to turn bystanders into active defenders.

The fact that the students of our sample feel moved with the victims´ feelings concurs with the results found by

Romera et al. (

2015) and

Del Barrio et al. (

2003). These results are consistent with data available from developmental psychology in that this kind of peer aggression, which entails a violation of moral norms, is normally experienced with great emotional intensity, a fact which acts as a powerful inhibitor of such transgressive behaviour (

Clemente-Estevan et al. 2013). Consequently, the children’s responses should be viewed positively for two reasons. First, they show that potential bystanders are on hand who sympathize with the victim’s plight and condemn the bullies’ acts; this could be a key factor in the development of any intervention program, whose goal is to turn passive bystanders into active defenders (

Van der Ploega et al. 2017). Second, as

Fitzpatrick and Bussey (

2018) found in a sample of secondary schoolchildren, those with a higher degree of moral disengagement were more likely to get involved in the bullying of peers. Furthermore, it has been documented that moral engagement mediated the relationship between bullying and school climate, so that the better the school climate is, the less frequently bullying conflicts exist (

Yang et al. 2020). Fortunately, our results show that the students of our sample display high levels of moral engagement.

In relation with the coping strategies, our finding is equivalent to that of

Cerda et al. (

2012) for Chilean children between the ages of 4 and 6 years, but contrary to that of

Del Barrio et al. (

2003), who detected that this coping strategy decreased as children grew older. The latter result could be read as indicating a developmental trend since peers are known to attain great importance and to eclipse adults as preferred interlocutors (

Jenkins et al. 2018). Nevertheless, some research suggests that other factors may be involved, such as, for instance, children’s belief that teachers do not really know what is going on or simply turn a blind eye to problems (

Ombudsman-UNICEF 2007). There can be no doubt that one of the key factors that has been found to contribute to a significant reduction in this sort of conduct is outright rejection on the part of teachers. In line with this last idea are the results obtained by

Donat et al. (

2018) who have documented that the more the students felt treated justly by their teachers and the more positively the students evaluated their teachers´ classroom management, the less bullying behaviour they reported.

With respect to the coping strategy of confronting the bullies, it is worth pointing out that any prevention program should give explicit consideration to the various options available to children and appraise them critically so that the children can distinguish between appropriate and inappropriate strategies.

6. Conclusions

In summary, we conclude that bullying prevention programs should start as early as preschool age. Any prevention program at this early age should pay particular attention to several issues. Firstly, it is important to stress that bullying has a strong contextual component and that anyone could be a victim under the right circumstances. By stressing this idea, we can dissuade students from viewing bullying as a remote phenomenon that only happens to others. In other words, children should be persuaded to think: next time this could happen to me. Likewise, by promoting this awareness, and given that students feel moved by the victim’s suffering, we should try to provide strategies to turn those bystanders into defenders by providing students with appropriate skills, such us avoiding reinforcing the bully, giving comfort to the victims, or even reporting to teachers (

Monks et al. 2021). Another third idea to include, especially with younger children, is that bullying is not only physical aggression, but isolating or preventing other peers from playing, as kids with no friends are far more predisposed to be bullied (

Salmivalli and Peets 2018). Finally, over the course of our interviews, we have detected some inadequate bullying coping strategies, such as confrontations with the bully. It was actually the second most common response among our students. In this sense, any prevention scheme mut clearly differentiate what coping strategies are right and effective from those which are undesirable and often could, in fact, worsen the conflict.

Likewise, in view of these results presented here and in other similar studies (

Almeida et al. 2001;

Del Barrio et al. 2003;

Menesini et al. 2003) showing considerable similarities in the mental representations of preschool, primary, and secondary schoolchildren, our theoretical position lies between the two contrasting stances described earlier in the introduction section. On the one hand, we believe that it is possible to identify forms of conduct and associated meanings which are strikingly similar in form and content to those found during adolescence, while acknowledging the fact that key aspects make them worthy of genuine consideration.

For this reason, we are inclined to call these early manifestations of the phenomenon

as proto-bullying behaviours, a term which stresses the developmental continuity detected at preschool age and among adolescents, without

confounding the two age groups. This theoretical positioning would be consistent with

Huitsing and Monks (

2018) and

Monks et al. (

2021), when they acknowledge that peer victimization among preschoolers seems to differ qualitatively from what is observed among older children, in the sense that aggressors tend to be less selective with their victims and aggression is often not unidirectional, more dyadic, and less of a group process, so that other peripheral roles, such as assistant, reinforcer, or defender, are much harder to observe.

Consequently, this latter reasoning brings us to coin the term bullying spectrum behaviours to denote the wide range of aggressive conduct between peers that can be detected throughout the different stages of schooling; not only does it emphasize the developmental continuity of its different manifestations, but it also favours a genuine consideration of each in terms of the development stage at which it occurs. Nevertheless, without any hesitation, a lot more work is required during early school years to deepen the knowledge of how such children think; that knowledge may provide important keys for understanding and preventing bullying.