How Social Identity Affects Entrepreneurs’ Desire for Control

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1.1. The Social Identity of Entrepreneurs

2.1.2. Social Identity as Determinant of the Control–Value Tradeoff

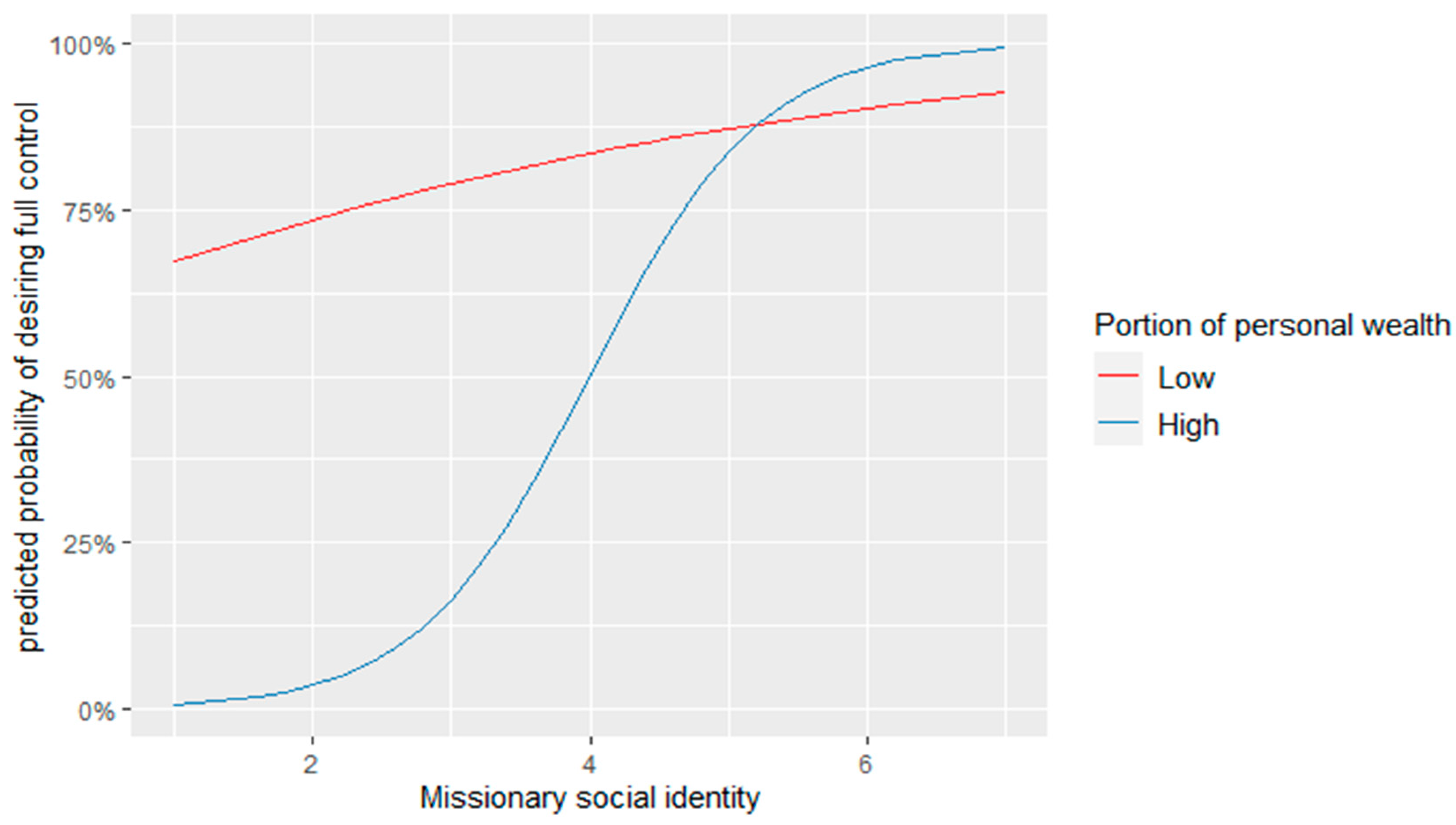

2.1.3. The Moderating Role of the Portion of Personal Wealth Willing to Invest

2.2. Results

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldrich, Howard E., and C. Marlene Fiol. 1994. Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry creation. Academy of Management Review 19: 645–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemany, Luisa, and Job J. Andreoli, eds. 2018. Entrepreneurial Finance: The Art and Science of Growing Ventures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alsos, Gry Agnete, Tommy Høyvarde Clausen, Ulla Hytti, and Sølvi Solvoll. 2016. Entrepreneurs’ social identity and the preference of causal and effectual behaviours in start-up processes. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 28: 234–58. [Google Scholar]

- Amit, Raphael, Kenneth MacCrimmon, Charlene Zietsma, and John MOesch. 2001. Does money matter?: Wealth attainment as the motive for initiating growth-oriented technology ventures. Journal of Business Venturing 16: 119–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, Christine, Diane Burton, and Charles O’Reilly. 2007. Early teams: The impact of team demography on VC financing and going public. Journal of Business Venturing 22: 147–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bitler, Marianne, Tobias Moskowitz, and Annette Vissing-Jørgensen. 2005. Testing agency theory with entrepreneur effort and wealth. The Journal of Finance 60: 539–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brändle, Leif, Elisabeth Berger, Stephan Golla, and Andreas Kuckertz. 2018. I am what I am-How nascent entrepreneurs’ social identity affects their entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Journal of Business Venturing Insights 9: 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brändle, Leif, Stephan Golla, and Andreas Kuckertz. 2019. How entrepreneurial orientation translates social identities into performance. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 25: 1433–51. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, Marilynn, and Wendi Gardner. 1996. Who is this “we”? Levels of collective identity and self representations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 71: 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, Candida, Patricia Greene, and Myra Hart. 2001. From initial idea to unique advantage: The entrepreneurial challenge of constructing a resource base. Academy of Management Perspectives 15: 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, Candida, Tatiana Manolova, and Linda Edelman. 2008. Properties of emerging organizations: An empirical test. Journal of Business Venturing 23: 547–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob, Patricia Cohen, Stephen West, and Leona Aiken. 2013. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, Massimo, and Luca Grilli. 2010. On growth drivers of high-tech start-ups: Exploring the role of founders’ human capital and venture capital. Journal of Business Venturing 25: 610–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Arnold, and William Dunkelberg. 1986. Entrepreneurship and paths to business ownership. Strategic Management Journal 7: 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Cruz, Marina Estra, Antonio Verdú Jover, and Jose Gómez Gras. 2018. Influence of the entrepreneur’s social identity on business performance through effectuation. European Research on Management and Business Economics 24: 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diestre, Luis, and Nandini Rajagopalan. 2012. Are all ‘sharks’ dangerous? new biotechnology ventures and partner selection in R&D alliances. Strategic Management Journal 33: 1115–34. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Evan, and Dean Shepherd. 2002. Self-employment as a career choice: Attitudes, entrepreneurial intentions, and utility maximization. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 26: 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen. 1989. Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review 14: 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2021. Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SME. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes/supporting-entrepreneurship/transfer-business (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Evans, David, and Boyan Jovanovic. 1989. An estimated model of entrepreneurial choice under liquidity constraints. Journal of Political Economy 97: 808–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattoum-Guedri, Asma, Frédéric Delmar, and Mike Wright. 2018. The best of both worlds: Can founder-CEOs overcome the rich versus king dilemma after IPO? Strategic Management Journal 39: 3382–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauchart, Emmanuelle, and Marc Gruber. 2011. Darwinians, communitarians, and missionaries: The role of founder identity in entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Journal 54: 935–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fauchart, Emmanuelle, Philipp Sieger, and Thomas Markus Zellweger. 2019. Founder social identity and the financial performance of new ventures. Academy of Management Proceedings 2019: 12833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, Nikolaus, Marc Gruber, Dietmar Harhoff, and Joachim Henkel. 2006. What you are is what you like—Similarity biases in venture capitalists’ evaluations of start-up teams. Journal of Business Venturing 21: 802–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garg, Sam, and Kathleen Eisenhardt. 2017. Unpacking the CEO–board relationship: How strategy making happens in entrepreneurial firms. Academy of Management Journal 60: 1828–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, Chris, Marfuga Iskandarova, and Robert Blackburn. 2020. Founders’ social identity and entrepreneurial self-efficacy amongst nascent entrepreneurs: A configurational perspective. Journal of Business Venturing Insights 13: e00160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, Thomas. 1998. The allocation of control rights in venture capital contracts. The Rand Journal of Economics 29: 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, Michael. 2020. Social Identity Theory. Contemporary Social Psychological Theories. Redwood City: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, Michael, and Deborah Terry. 2000. Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. Academy of Management Review 25: 121–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, Michael, Deborah Terry, and Katherine White. 1995. A tale of two theories: A critical comparison of identity theory with social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly 58: 255–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, Richard, and Bret Fund. 2012. Reassessing the practical and theoretical influence of entrepreneurship through acquisition. Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance 16: 29–56. [Google Scholar]

- Katila, Riitta, Jeff Rosenberger, and Kathleen Eisenhardt. 2008. Swimming with sharks: Technology ventures, defense mechanisms and corporate relationships. Administrative Science Quarterly 53: 295–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, Phillip, and Kyle Longest. 2014. You can’t leave your work behind: Employment experience and founding collaborations. Journal of Business Venturing 29: 785–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, Andrew P., Lindred L. Greer, and Bart De Jong. 2020. Start-up teams: A multidimensional conceptualization, integrative review of past research, and future research agenda. Academy of Management Annals 14: 231–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, Christian, Christian Lechner, and Frank Pelzel. 2020. Many roads lead to Rome: How human, social, and financial capital are related to new venture survival. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 44: 909–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuleman, Miguel, Kevin Amess, Mike Wright, and Louise Scholes. 2009. Agency, strategic entrepreneurship, and the performance of private equity–backed buyouts. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 33: 213–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, Danny, and Isabelle Le Breton-Miller. 2011. Governance, social identity, and entrepreneurial orientation in closely held public companies. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 35: 1051–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Nettra D., Marc Gruber, and Julia Binder. 2019. Painting with all the colors: The Value of Social Identity Theory for Understanding Social Entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Review 44: 213–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, Jeffrey, and Gerald Salancik. 1978. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. New York: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, Erin, and Ted Baker. 2014. It’s what you make of it: Founder identity and enacting strategic responses to adversity. Academy of Management Journal 57: 1406–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruef, Martin, Howard E. Aldrich, and Nancy M. Carter. 2003. The structure of founding teams: Homophily, strong ties, and isolation among US entrepreneurs. American Sociological Review 68: 195–222. [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford, Austin. 2021. Founder Social Identity as a Predictor of Customer and Competitor Orientation in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Ph.D. thesis, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing University of North Carolina, Charlotte, NC, USA; p. 28492806. [Google Scholar]

- Sapienza, Harry, Audrey Korsgaard, and Daniel Forbes. 2003. The Self-Determining Motive and Entrepreneurs’ Choice of Financing. In Cognitive Approaches to Entrepreneurship Research. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Schwienbacher, Armin. 2007. A theoretical analysis of optimal financing strategies for different types of capital-constrained entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing 22: 753–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwienbacher, Armin. 2008. Innovation and venture capital exits. The Economic Journal 118: 1888–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shane, Scott, and Sankaran Venkataraman. 2000. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review 25: 217–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shepherd, Dean, Trenton Williams, and Holger Patzelt. 2015. Thinking about entrepreneurial decision making: Review and research agenda. Journal of Management 41: 11–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieger, Philipp, Marc Gruber, Emmanuelle Fauchart, and Thomas Zellwegerd. 2016. Measuring the social identity of entrepreneurs: Scale development and international validation. Journal of Business Venturing 31: 542–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Souitaris, Vangelis, Stefania Zerbinati, Bo (Grace) Peng, and Dean Shepherd. 2020. Should I stay or should I go? Founder power and exit via initial public offering. Academy of Management Journal 63: 64–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, Jan E., and Peter J. Burke. 2000. Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly 63: 224–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stryker, Sheldon, and Richard T. Serpe. 1982. Commitment, Identity Salience, and Role Behavior: Theory and Research Example. In Personality, Roles, and Social Behavior. New York: Springer, pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, Henri, and John Turner. 1979. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Edited by S. Worchel and W. Austin. Monterey: Brooks/Cole Pub. Co., pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, Noam. 2003. Founder-CEO succession and the paradox of entrepreneurial success. Organization Science 14: 149–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, Noam. 2012. The Founder’s Dilemmas: Anticipating and Avoiding the Pitfalls that Can Sink a Startup. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, Noam. 2017. The throne vs. the kingdom: Founder control and value creation in startups. Strategic Management Journal 38: 255–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Mike, Robert E. Hoskisson, and Lowell W. Busenitz. 2001a. Firm rebirth: Buyouts as facilitators of strategic growth and entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Perspectives 15: 111–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Mike, Robert E. Hoskisson, Lowell W. Busenitz, and Jay Dial. 2001b. Finance and management buyouts: Agency versus entrepreneurship perspectives. Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance 3: 239–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wry, Tyler, and Jeffrey G. York. 2017. An identity-based approach to social enterprise. Academy of Management Review 42: 437–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wry, Tyler, J. Adam Cobb, and Howard E. Aldrich. 2013. More than a metaphor: Assessing the historical legacy of resource dependence and its contemporary promise as a theory of environmental complexity. The Academy of Management Annals 7: 441–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, Jeffrey G., Isobel O’Neil, and Saras D. Sarasvathy. 2016. Exploring environmental entrepreneurship: Identity coupling, venture goals, and stakeholder incentives. Journal of Management Studies 53: 695–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuzul, Tiona, and Mary Tripsas. 2020. Start-up inertia versus flexibility: The role of founder identity in a nascent industry. Administrative Science Quarterly 65: 395–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Desire for control | 0.14 | 0.34 | |||||||||||

| 2. Darwinian social identity | 5.62 | 0.60 | 0.12 | ||||||||||

| 3. Communitarian social identity | 3.95 | 1.24 | −0.02 | −0.12 | |||||||||

| 4. Missionary social identity | 4.34 | 1.29 | 0.09 | −0.05 | 0.57 | ||||||||

| 5. Age (ln) | 1.66 | 0.07 | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.08 | |||||||

| 6. Gender | 0.05 | 0.23 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.01 | ||||||

| 7. Educational level | 0.84 | 0.36 | −0.16 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.08 | −0.19 | −0.23 | |||||

| 8. Startup experience | 0.36 | 0.48 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| 9. Preferred size a | 2.26 | 0.82 | −0.18 | −0.08 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.18 | −0.15 | 0.05 | −0.07 | |||

| 10. Capital to invest a | 3.44 | 1.63 | 0.01 | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.02 | 0.18 | ||

| 11. Acquired venture | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.18 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.08 | 0.13 | −0.15 | −0.10 | −0.07 | 0.29 | 0.19 | |

| 12. Portion of personal wealth | 2.50 | 1.23 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.16 | −0.06 | −0.19 | −0.17 | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) |

| Darwinian social identity | 0.736 | −1.693 | |

| (0.590) | (1.466) | ||

| Communitarian social identity | −0.281 | 0.053 | |

| (0.343) | (0.893) | ||

| Missionary social identity | 0.747 * | −0.389 | |

| (0.367) | (0.870) | ||

| Darwinian social identity × Portion of personal wealth | 1.190 * | ||

| (0.607) | |||

| Communitarian social identity × Portion of personal wealth | −0.176 | ||

| (0.308) | |||

| Missionary social identity × Portion of personal wealth | 0.544 † | ||

| (0.298) | |||

| Age | −3.704 | −5.899 | −9.552 † |

| (4.324) | (4.801) | (5.414) | |

| Gender | −1.311 | −0.971 | −1.528 |

| (1.646) | (1.576) | (2.126) | |

| Educational level | −1.389 † | −1.184 | −1.482 |

| (0.797) | (0.890) | (0.981) | |

| Startup experience | −1.164 | −1.426 † | −1.573 † |

| (0.710) | (0.767) | (0.889) | |

| Acquired company | 1.829 * | 2.225 ** | 3.129 ** |

| (0.721) | (0.776) | (0.997) | |

| Portion of personal wealth | −0.260 | −0.199 | −0.472 |

| (0.274) | (0.280) | (0.343) | |

| Preferred size a | Included | Included | Included |

| Capital to invest a | Included | Included | Included |

| Constant | 8.324 | 11.215 | 19.180 * |

| (7.653) | (8.397) | (9.731) | |

| Pseudo R² (Nagelkerke) | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.53 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vanoorbeek, H.; Lecluyse, L. How Social Identity Affects Entrepreneurs’ Desire for Control. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11010007

Vanoorbeek H, Lecluyse L. How Social Identity Affects Entrepreneurs’ Desire for Control. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleVanoorbeek, Hans, and Laura Lecluyse. 2022. "How Social Identity Affects Entrepreneurs’ Desire for Control" Social Sciences 11, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11010007

APA StyleVanoorbeek, H., & Lecluyse, L. (2022). How Social Identity Affects Entrepreneurs’ Desire for Control. Social Sciences, 11(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11010007