Engineers and Social Responsibility: Influence of Social Work Experience, Hope and Empathic Concern on Social Entrepreneurship Intentions among Graduate Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

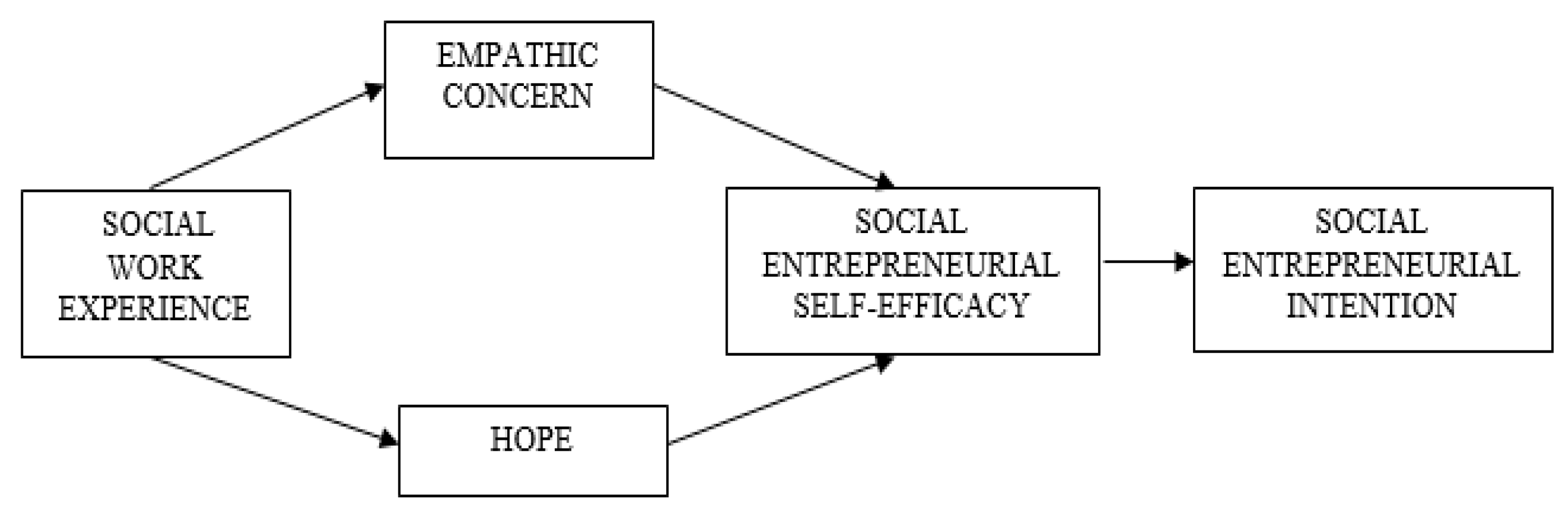

- To assess the influence of Social Work Experience/exposure on Hope and Empathic Concern.

- To examine the effect of Empathic Concern and Hope on Social Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and subsequently on SEI.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Engineers, Entrepreneurship, and Society: The Indian Context

2.2. Social Entrepreneurship: Theoretical Background

2.3. Social Work Experience

2.4. Empathic Concern

2.5. Hope

2.6. Social Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (S-ESE)

2.7. Social Entrepreneurial Intention (SEI)

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Influence of Social Work Experience (SWE) on Empathic Concern (EC)

3.2. Influence of Social Work Experience (SWE) on Hope

3.3. Influence of Empathic Concern (EC) on Social Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (S-ESE)

3.4. Influence of Hope on S-ESE

3.5. Influence of Social Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (S-ESE) on SEI

3.6. The Conceptual Model

4. Method

4.1. Data Collection

4.2. Research Design

5. Results

5.1. Common Method Bias and Multi-Collinearity Test

5.2. Measurement Model Analysis

5.3. Structural Model Analysis

6. Discussion

7. Implications

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Practical Implications

8. Limitations and Future Scope

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adamson, Matt, and Jini L. Roby. 2011. Parental Loss and Hope among Orphaned Children in South Africa: A Pilot Study. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies 22: 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, Icek. 1981. Influencing Attitudes and Behavior. Contemporary Psychology: A Journal of Reviews 26: 964–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, Icek. 1991. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50: 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qudah, Anas Ali, Manaf Al-Okaily, and Hamza Alqudah. 2022. The relationship between Social Entrepreneurship and sustainable development from economic growth perspective: 15 ‘RCEP’ countries. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 12: 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, Shahzad, Kamal Munir, and Tricia Gregg. 2012. Impact at the “Bottom of the Pyramid”: The Role of Social Capital in Capability Development and Community Empowerment. Journal of Management Studies 49: 813–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmat, Fara, Ahmed Shahriar Ferdous, and Paul Couchman. 2015. Understanding the Dynamics between Social Entrepreneurship and Inclusive Growth in Subsistence Marketplaces. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing 34: 252–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacq, Sophie, and Elisa Alt. 2018. Feeling capable and valued: A pro-social perspective on the link between Empathy and Social Entrepreneurial Intentions. Journal of Business Venturing 33: 333–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacq, Sophie, and Frank Janssen. 2011. The multiple faces of Social Entrepreneurship: A review of definitional issues based on geographical and thematic criteria. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 23: 373–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1977. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review 84: 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddy, Jennifer, Patrick O’Leary, Ming-Sum Tsui, Chui-Man Pak, and Duu-Chiang Wang. 2018. Inspiring hope through social work practice. International Social Work 61: 587–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Council. 2016. Social Value Economy A Survey of the Social Enterprise Landscape in India. Available online: https://www.britishcouncil.in/sites/default/files/british_council_se_landscape_in_india_-_report.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Cardella, Giuseppina Maria, Brizeida Raquel Hernández-Sánchez, Alcides Almeida Monteiro, and José Carlos Sánchez-García. 2021. Social Entrepreneurship research: Intellectual structures and future perspectives. Sustainability 13: 7532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, Jon, and Jennifer Sequeira. 2007. Prior family business exposure as intergenerational influence and entrepreneurial intent: A Theory of Planned Behavior approach. Journal of Business Research 60: 1090–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, Arindam, Mudang Tagiya, and Shyamalee Sinha. 2021. Techno-entrepreneurship in India Through a Strategic Lens. In Research in Intelligent and Computing in Engineering. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. Edited by Kumar Raghvendra, Quang Nguyen Ho, Kumar Solanki, Vijender Cardona, Manuel Pattnaik and Prasant Kumar. Singapore: Springer, vol. 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlosta, Simone, Holger Patzelt, Sabine B. Klein, and Christian Dormann. 2010. Parental role models and the decision to become self-employed: The moderating effect of personality. Small Business Economics 38: 121–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Nia, and Satyajit Majumdar. 2014. Social Entrepreneurship as an essentially contested concept: Opening a new avenue for systematic future research. Journal of Business Venturing 29: 363–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Jeonghwan, Kihwan Kim, Rob Marjerison, Bok Gyo Jeong, Sookyoung Lee, and Valerie Vaccaro. 2021. The effects of morality and positivity on social entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Stephen, and Damian Grace. 1994. Engineers and social responsibility: An obligation to do good. IEEE Technology and Society Magazine 13: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comunian, Anna Laura, and Uwe Gielen. 1995. Moral Reasoning and Prosocial Action in Italian Culture. The Journal of Social Psychology 135: 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, Patricia, and Marcus Ho. 2010. How Opportunities Develop in Social Entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 34: 635–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Sandoval, Marco, José Carlos Vázquez-Parra, and Patricia Esther Alonso-Galicia. 2022. Student Perception of Competencies and Skills for Social Entrepreneurship in Complex Environments: An Approach with Mexican University Students. Social Sciences 11: 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacin, Tina, Peter Dacin, and Paul Tracey. 2011. Social Entrepreneurship: A Critique and Future Directions. Organization Science 22: 1203–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, Punita Bhatt, and Robert Gailey. 2012. Empowering Women Through Social Entrepreneurship: Case Study of a Women’s Cooperative in India. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36: 569–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Mark H., Kyle V. Mitchell, Jennifer A. Hall, Jennifer Lothert, Tyra Snapp, and Marnee Meyer. 1999. Empathy, Expectations, and Situational Preferences: Personality Influences on the Decision to Participate in Volunteer Helping Behaviors. Journal of Personality 67: 469–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giunta, Laura, Nancy Eisenberg, Anne Kupfer, Patrizia Steca, Carlo Tramontano, and Gian Caprara. 2010. Assessing Perceived Empathic and Social Self-Efficacy Across Countries. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 26: 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade. 2021. Annual Report 2021–22. Available online: https://dpiit.gov.in/sites/default/files/IPP_ANNUAL_REPORT_ENGLISH.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- Duggleby, Wendy, and Karen Wright. 2009. Transforming Hope: How Elderly Patients Live with Hope. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research 41: 204–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, Abhishek, and Jay Weerawardena. 2018. Conceptualizing and operationalizing the Social Entrepreneurship construct. Journal of Business Research 86: 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, Nancy, Richard Fabes, Paul Miller, Jim Fultz, Rita Shell, Robin Mathy, and Ray Reno. 1989. Relation of sympathy and personal distress to pro-social behavior: A multimethod study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57: 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, Karl, and Magnus Englander. 2017. Empathy in social work. Journal of Social Work Education 53: 607–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, Kati. 2012. Social entrepreneurs and their personality. In Social Entrepreneurship and Social Business. Wiesbaden: Gabler Verlag, pp. 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, David B., and Maximilian Kubota. 2015. Hope, self-efficacy, optimism, and academic achievement: Distinguishing constructs and levels of specificity in predicting college grade-point average. Learning and Individual Differences 37: 210–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimmons, Jason R., and Evan J. Douglas. 2011. Interaction between feasibility and desirability in the formation of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing 26: 431–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 382–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, Florian, and Dietmar Grichnik. 2013. Social Entrepreneurial Intention Formation of Corporate Volunteers. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 4: 153–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froiland, John Mark, and Frank C. Worrell. 2016. Parental autonomy support, community feeling and student expectations as contributors to later achievement among adolescents. Educational Psychology 37: 261–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, Abel, and María Soledad Ramírez-Montoya. 2021. Social Entrepreneurship education: Changemaker training at the university. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning 11: 1236–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghatak, Arpita, Swagato Chatterjee, and Bhaskar Bhowmick. 2020. Intention towards digital Social Entrepreneurship: An integrated model. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeno, Elizabeth J., Laura Ting, and Kevin Wade. 2018. Predicting empathy in helping professionals: Comparison of social work and nursing students. Social Work Education 37: 173–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph, Tomas M. Hult, Christian Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2021. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Randolph, and Jack Lulich. 2021. University Strategic Plans: What they Say about Innovation. Innovative Higher Education 46: 261–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugan, Gørill, Britt Karin Utvaer, and Unni Karin Moksnes. 2013. The Herth Hope Index—A Psychometric Study among Cognitively Intact Nursing Home Patients. Journal of Nursing Measurement 21: 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockerts, Kai. 2017. Determinants of Social Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 41: 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, Md. Uzzal, Md. Shamsul Arefin, and Vimolwan Yukongdi. 2021. Personality traits, social self-efficacy, social support, and social entrepreneurial intention: The moderating role of gender. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, Sue. 2007. Exploring Hope: Its Meaning for Adults Living with Depression and for Social Work Practice. Australian e-journal for the Advancement of Mental Health 6: 186–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, Teemu, Seppo Luoto, and Erno T. Tornikoski. 2010. Influence of work history on entrepreneurial intentions in ‘prime age’ and ‘third age’: A preliminary study. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 28: 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrath, Sara H., O’Edward H. Brien, and Courtney Hsing. 2010. Changes in Dispositional Empathy in American College Students Over Time: A Meta-Analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review 15: 180–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, Norris F., and Deborah V. Brazeal. 1994. Entrepreneurial Potential and Potential Entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 18: 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, Norris F., Michael D. Reilly, and Alan L. Carsrud. 2000. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing 15: 411–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, Philipp. 2020. Can there be only one? An empirical comparison of four models on social entrepreneurial intention formation. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 16: 641–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kytle, Jackson, and Albert Bandura. 1978. Social Learning Theory. Contemporary Sociology 7: 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Voon-Hsien, Keng-Boon Ooi, Alain Yee-Loong Chong, and Binshan Lin. 2013. A structural analysis of greening the supplier, environmental performance and competitive advantage. Production Planning and Control 26: 116–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Voon-Hsien, Keng-Boon Ooi, Alain Yee-Loong Chong, and Christopher Seow. 2014. Creating technological innovation via green supply chain management: An empirical analysis. Expert Systems with Applications 41: 6983–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, Francisco, and Yi-Wen Chen. 2009. Development and Cross-Cultural Application of a Specific Instrument to Measure Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 33: 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, Francisco, Juan Carlos Rodríguez-Cohard, and José M. Rueda-Cantuche. 2010. Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels: A role for education. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 7: 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, Johanna, and Ignasi Martí. 2006. Social Entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business 41: 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, Johanna, and Ernesto Noboa. 2006. Social Entrepreneurship: How Intentions to Create a Social Venture are Formed. In Social Entrepreneurship. Edited by Johanna Mair, Jeffrey Robinson and Kai Hockerts. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan, pp. 121–35. [Google Scholar]

- McClure, Kevin R. 2015. Exploring Curricular Transformation to Promote Innovation and Entrepreneurship: An Institutional Case Study. Innovative Higher Education 40: 429–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Toyah, Curtis Wesley, and Denise Williams. 2012. Educating the Minds of Caring Hearts: Comparing the Views of Practitioners and Educators on the Importance of Social Entrepreneurship Competencies. Academy of Management Learning & Education 11: 349–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises. 2020. Government of India, Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, Annual Report 2019–20. Available online: https://msme.gov.in/sites/default/files/FINAL_MSME_ENGLISH_AR_2019-20.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- NIDHI-Entrepreneur-in-Residence Program. 2022. Entrepreneurs supported under NIDHI EIR Program. Available online: http://www.nidhi-eir.in/eirs.php (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Niezink, Lidewij W., Frans W. Siero, Pieternel Dijkstra, Abraham P. Buunk, and Dick P. H. Barelds. 2012. Empathic concern: Distinguishing between tenderness and sympathy. Motivation and Emotion 36: 544–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Science & Technology Entrepreneurship Development Board. 2022. List of DST-NIDHI Technology Business Incubators (TBI). Available online: https://www.nstedb.com/List-NSTEDB-TBIs.htm (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- O’Sullivan, Geraldine. 2011. The relationship between hope, eustress, self-efficacy, and life satisfaction among undergraduates. Social Indicators Research 101: 155–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachura, Aneta. 2021. Modelling of Cross-Organisational Cooperation for Social Entrepreneurship. Social Sciences 10: 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, Cristian, Ionel Bostan, Ioan-Bogdan Robu, Andrei Maxim, and Laura Diaconu Maxim. 2016. An Analysis of the Determinants of Entrepreneurial Intentions among Students: A Romanian Case Study. Sustainability 8: 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambe, Patient, and Takawira Munyaradzi Ndofirepi. 2019. Explaining Social Entrepreneurial Intentions among College Students in Zimbabwe. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 12: 175–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selznick, Benjamin S., Laura S. Dahl, Ethan Youngerman, and Matthew J. Mayhew. 2022. Equitably Linking Integrative Learning and Students’ Innovation Capacities. Innovative Higher Education 47: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, Ferudun, and Onur Erdogan. 2015. Academic optimism, hope and zest for work as predictors of teacher self-efficacy and perceived success. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice 15: 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapero, Albert, and Lisa Sokol. 1982. Social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship. Edited by Calvin A. Kent, Donald L. Sexton and Karl H. Vesper. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, pp. 72–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Lalit. 2015. A review of the role of HEI’s in developing academic entrepreneurship. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 7: 168–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, Mandy Siew Chen, Joshua Edward Galloway, Hazel Melanie Ramos, and Michael James Mustafa. 2021. University’s support for entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of entrepreneurial climate. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Partap. 2012. Social Entrepreneurship: A Growing Trend in Indian Economy. International Journal of Innovations in Engineering and Technology 1: 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C. Rick. 1995. Conceptualising, Measuring, and Nurturing Hope. Journal of Counseling and Development 73: 355–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C. Richard. 2002. TARGET ARTICLE: Hope Theory: Rainbows in the Mind. Psychological Inquiry 13: 249–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, Charles R., Cheri Harris, John R. Anderson, Sharon A. Holleran, Lori M. Irving, Sandra T. Sigmon, Lauren Yoshinobu, June Gibb, Charyle Langelle, and Pat Harney. 1991. The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual differences measure of Hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 60: 570–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, Selwyn, and G. Mettilda Bhuvaneswari. 2016. Reflective ability, empathy, and emotional intelligence in undergraduate social work students: A cross-sectional study from India. Social Work Education 35: 560–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirzaker, Rebecca, Laura Galloway, Jatta Muhonen, and Dimitris Christopoulos. 2021. The drivers of Social Entrepreneurship: Agency, context, compassion and opportunism. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 27: 1381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanepoel, Sonia, Petrus Botha, and Rose-Rusty Innes. 2015. Organizational behaviour: Exploring the relationship between ethical climate, self-efficacy and hope. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR) 31: 1419–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tams, Svenja, and Judi Marshall. 2010. Responsible careers: Systemic reflexivity in shifting landscapes. Human Relations 64: 109–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, Simon, Stephen McKay, Jenny Phillimore, and Nina Teasdale. 2011. Exploring gender and Social Entrepreneurship: Women’s leadership, employment and participation in the third sector and social enterprises. Voluntary Sector Review 2: 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thong, James Y. 2001. Resource constraints and information systems implementation in Singaporean small businesses. Omega 29: 143–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, Preeti, Anil K. Bhat, and Jyoti Tikoria. 2017. The role of emotional intelligence and self-efficacy on social entrepreneurial attitudes and social entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 8: 165–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás, José Manuel, Melchor Gutiérrez, Sylvia Georgieva, and Miosotis Hernández. 2019. The effects of self-efficacy, Hope, and engagement on the academic achievement of secondary education in the Dominican Republic. Psychology in the Schools 57: 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, Paul, and Owen Jarvis. 2007. Toward a Theory of Social Venture Franchising. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 31: 667–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnage, Barbara F., Young Joon Hong, Andre P. Stevenson, and Beverly Edwards. 2012. Social work students’ perceptions of themselves and others: Self-esteem, empathy, and forgiveness. Journal of Social Service Research 38: 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, Sumaiya, Fazeelat Masood, and Mubashir Ali Khan. 2021. Impact of empathy, perceived social impact, social worth and social network on the social entrepreneurial intention in socio-economic projects. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 14: 65–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, Viswanath, James Y. L. Thong, and Xin Xu. 2012. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Quarterly 36: 157–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, Tuomo E., Kati Vasalampi, Noona Kiuru, Marja-Kristiina Lerkkanen, and Anna-Maija Poikkeus. 2019. The Role of Perceived Social Support as a Contributor to the Successful Transition from Primary to Lower Secondary School. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 64: 967–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Jiun-Hao, Chi-Cheng Chang, Shu-Nung Yao, and Chaoyun Liang. 2015. The contribution of self-efficacy to the relationship between personality traits and entrepreneurial Intention. Higher Education 72: 209–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardena, Jay, and Gillian Sullivan Mort. 2006. Investigating Social Entrepreneurship: A multidimensional model. Journal of World Business 41: 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yitshaki, Ronit, and Fredric Kropp. 2016. The role of social entrepreneurs’ compassion and identity in shaping opportunity recognition. Academy of Management Proceedings 2016: 12650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, Amna, Peng Xiaobao, Muhammad Athar Nadeem, Shamsa Kanwal, Abdul Hameed Pitafi, Gui Qiong, and Duan Yuzhen. 2021. Impact of positivity and empathy on social entrepreneurial intention: The moderating role of perceived social support. Journal of Public Affairs 21: e2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahn-Waxler, Carolyn, and Marian Radke-Yarrow. 1990. The origins of empathic Concern. Motivation and Emotion 14: 107–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, Shaker A., Eric Gedajlovic, Donald O. Neubaum, and Joel M. Shulman. 2009. A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search processes and ethical challenges. Journal of Business Venturing 24: 519–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Zhaocheng Elly, and Benson Honig. 2016. How Should Entrepreneurship Be Taught to Students with Diverse Experience? A Set of Conceptual Models of Entrepreneurship Education. In Models of Start-Up Thinking and Action: Theoretical, Empirical and Pedagogical Approaches (Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence and Growth 18). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 237–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Hao, Scott E. Seibert, and Gerald E. Hills. 2005. The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy in the Development of Entrepreneurial Intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology 90: 1265–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Xinshu, John G. Lynch, and Qimei Chen. 2010. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. Journal of Consumer Research 37: 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, Salman, Muhammad Athar Nadeem, Muhammad Kaleem Khan, Muhammad Azfar Anwar, Muhammad B. Iqbal, and Fahad Asmi. 2021. Opportunity recognition behavior and readiness of youth for Social Entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Research Journal 11: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Number of Responses | |

| Male | 136 | |

| Female | 107 | |

| Year of study | Number of responses | |

| 3rd year | 81 | |

| 4th year | 162 | |

| Specialization | Number of responses | |

| Electronics engineering | 40 | |

| Mechanical engineering | 38 | |

| Computer science engineering/IT | 32 | |

| Aeronautical/Aerospace engineering | 30 | |

| Chemical engineering | 18 | |

| Electrical engineering | 16 | |

| Civil engineering | 15 | |

| Industrial/Production engineering | 10 | |

| Automobile engineering | 09 | |

| Biotechnology | 07 | |

| Instrumentation technology | 07 | |

| Biomedical engineering | 06 | |

| Mechatronics engineering | 04 | |

| Metallurgy | 03 | |

| Polymer technology | 03 | |

| Print and media | 03 | |

| Food technology | 02 | |

| Region/State-Wise Responses | ||

| Region | State/Union Territory | No. of Responses |

| North India (55) | Delhi NCT | 24 |

| Haryana | 10 | |

| Madhya Pradesh | 07 | |

| Uttar Pradesh | 12 | |

| Uttarakhand | 02 | |

| South India (75) | Andhra Pradesh | 11 |

| Karnataka | 40 | |

| Kerala | 08 | |

| Tamil Nadu | 10 | |

| Telangana | 06 | |

| East India (36) | Bihar | 15 |

| Chhatisgarh | 04 | |

| Jharkhand | 06 | |

| Odisha | 02 | |

| West Bengal | 09 | |

| West India (77) | Goa | 06 |

| Gujarat | 12 | |

| Maharashtra | 58 | |

| Rajasthan | 01 | |

| Item Code | Item Description | Outer Loadings |

|---|---|---|

| Empathic Concern | ||

| EC1 | When I see someone less fortunate being taken advantage of, I feel protective toward them. | 0.818 |

| EC2 | I often have concerned feelings for people less fortunate than me. | 0.841 |

| EC3 | I would describe myself as a compassionate person. | 0.689 |

| EC4 | Seeing socially disadvantaged people triggers an emotional response in me. | 0.765 |

| EC5 | I try to imagine what socially disadvantaged people go through. | 0.727 |

| Hope | ||

| HS1 | I can think of many ways to get the things in life that are important to me. | 0.710 |

| HS2 | Even when others get discouraged, I know I can find a way to solve the problem. | 0.576 |

| HS3 | My past experiences have prepared me well for my future. | 0.807 |

| HS4 | I consider myself successful for my age. | 0.727 |

| HS5 | I meet the goals that I set for myself. | 0.751 |

| Social Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy | ||

| ESE1 | I can easily identify new opportunities for helping social causes. | 0.739 |

| ESE2 | I believe that I can think creatively to benefit others. | 0.766 |

| ESE3 | I can effectively market an idea for a social cause or enterprise. | 0.699 |

| ESE4 | I want my contribution to the society to have a social impact. | 0.693 |

| ESE5 | I am comfortable working in a team/with a team committed to a particular cause. | 0.695 |

| ESE6 | I am committed to helping people. | 0.748 |

| ESE7 | I can successfully identify social problems. | 0.728 |

| Social Work Experience | ||

| SWE1 | I have some experience working with social causes. | 0.909 |

| SWE2 | I often volunteer at social organisations. | 0.905 |

| SWE3 | I have worked with social organisations in the past. | 0.816 |

| SWE4 | I have a fair bit of knowledge about how social organisations function/operate. | 0.832 |

| SWE5 | I am actively involved in student clubs/organisations involved in social causes. | 0.831 |

| Social Entrepreneurial Intention | ||

| SEI1 | I can effectively apply my skills to make a difference in reducing social inequality. | 0.741 |

| SEI2 | In the future, I can apply my work experience to help social enterprises address social issues. | 0.771 |

| SEI3 | I will make every effort to use my acumen to bring about social change. | 0.809 |

| SEI4 | I am determined to have a direct social impact through my work in the future. | 0.797 |

| SEI5 | I have considered working for a social enterprise. | 0.724 |

| SEI6 | I see myself establishing a social enterprise at some stage in the future. | 0.788 |

| Latent Variable | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empathic Concern | 0.827 | 0.879 | 0.593 |

| Hope | 0.766 | 0.840 | 0.516 |

| SE Intention | 0.865 | 0.898 | 0.596 |

| SE Self-Efficacy | 0.849 | 0.885 | 0.525 |

| Social Work Experience | 0.911 | 0.934 | 0.739 |

| Latent Variable | Empathic Concern | Hope | SE Intention | SE Self-Efficacy | Social Work Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empathic Concern | 0.770 | ||||

| Hope | 0.323 | 0.718 | |||

| SE Intention | 0.411 | 0.407 | 0.772 | ||

| SE Self-Efficacy | 0.622 | 0.595 | 0.581 | 0.725 | |

| Social Work Experience | 0.322 | 0.520 | 0.437 | 0.575 | 0.860 |

| Latent Variable | Empathic Concern | Hope | SE Intention | SE Self-Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hope | 0.410 | |||

| SE Intention | 0.476 | 0.483 | ||

| SE Self-Efficacy | 0.738 | 0.725 | 0.668 | |

| Social Work Experience | 0.358 | 0.582 | 0.491 | 0.640 |

| Hypothesized Relationship | β-Values | T Statistics | Hypothesis Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Work Experience -> Empathic Concern | 0.322 * | 4.786 | Supported |

| Social Work Experience -> Hope | 0.520 * | 11.288 | Supported |

| Empathic Concern -> SE Self-Efficacy | 0.480 * | 7.749 | Supported |

| Hope -> SE Self-Efficacy | 0.440 * | 9.223 | Supported |

| SE Self-Efficacy -> SE Intention | 0.581 * | 13.902 | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lingappa, A.K.; Kamath, A.; Mathew, A.O. Engineers and Social Responsibility: Influence of Social Work Experience, Hope and Empathic Concern on Social Entrepreneurship Intentions among Graduate Students. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 430. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100430

Lingappa AK, Kamath A, Mathew AO. Engineers and Social Responsibility: Influence of Social Work Experience, Hope and Empathic Concern on Social Entrepreneurship Intentions among Graduate Students. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(10):430. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100430

Chicago/Turabian StyleLingappa, Anasuya K., Aditi Kamath, and Asish Oommen Mathew. 2022. "Engineers and Social Responsibility: Influence of Social Work Experience, Hope and Empathic Concern on Social Entrepreneurship Intentions among Graduate Students" Social Sciences 11, no. 10: 430. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100430