2.0 Society Convergences: Coexistence, Otherness, Communication and Edutainment †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What is required to bring the social phenomena of coexistence and otherness to the category of variables so they could be quantified and, consequently, be measurable?

- How can one effectively transform those concepts into measurable variables?

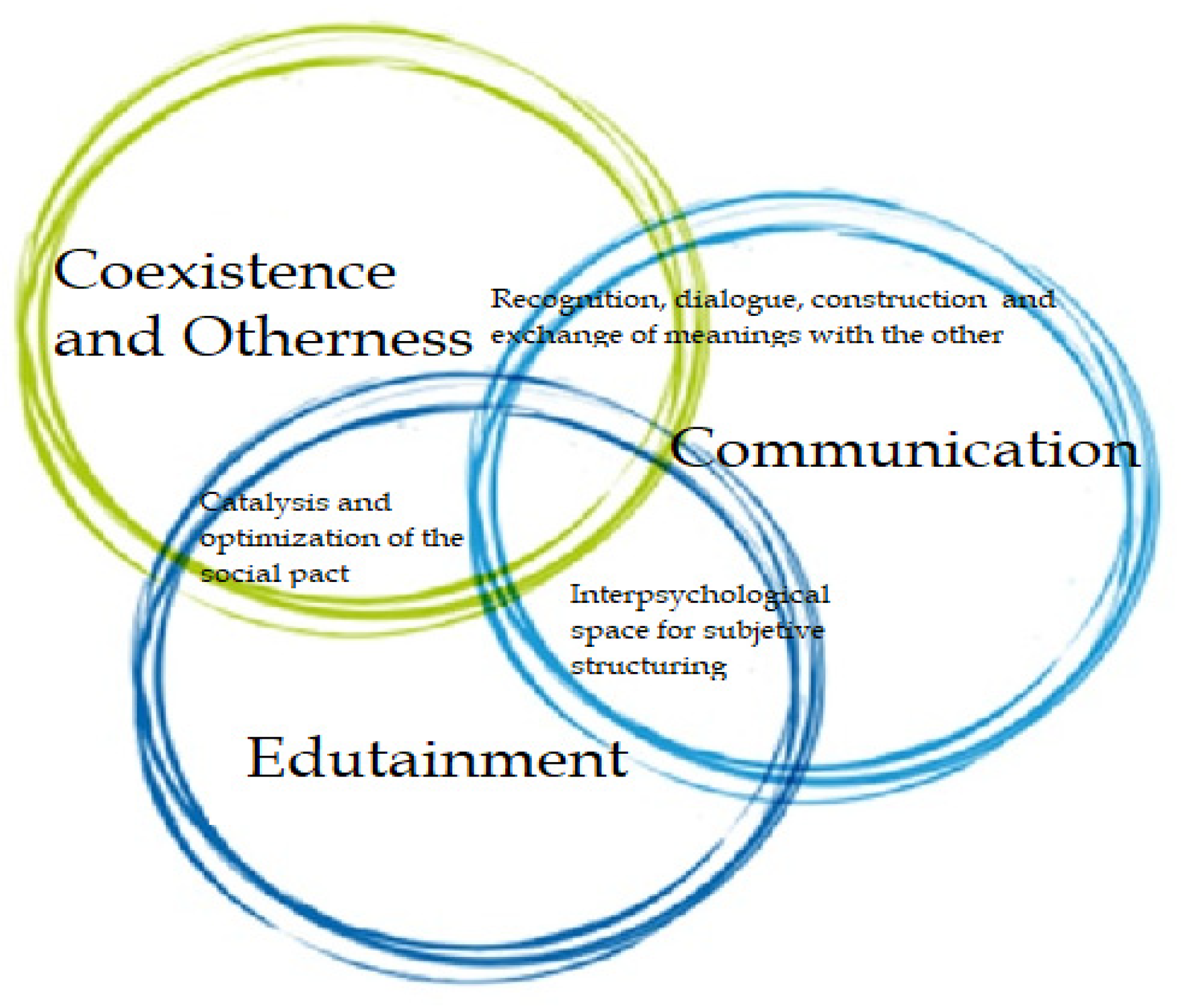

- Where lies the convergence between communication, edutainment, coexistence and otherness?

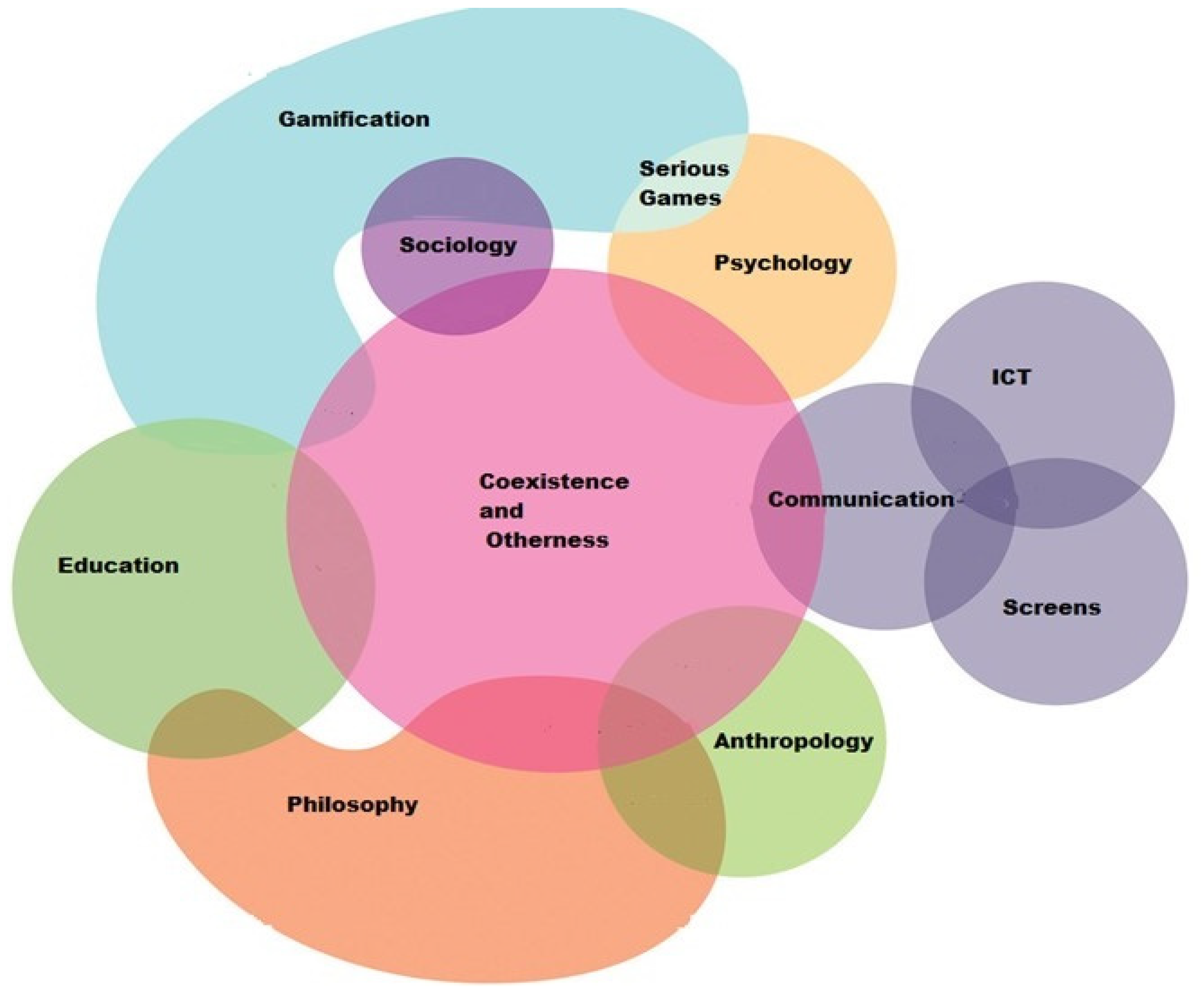

- Which disciplines are required to provide a sufficiently broad theoretical and conceptual background for the scientific basis of convergence between communication, edutainment, coexistence and otherness?

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Otherness and Coexistence

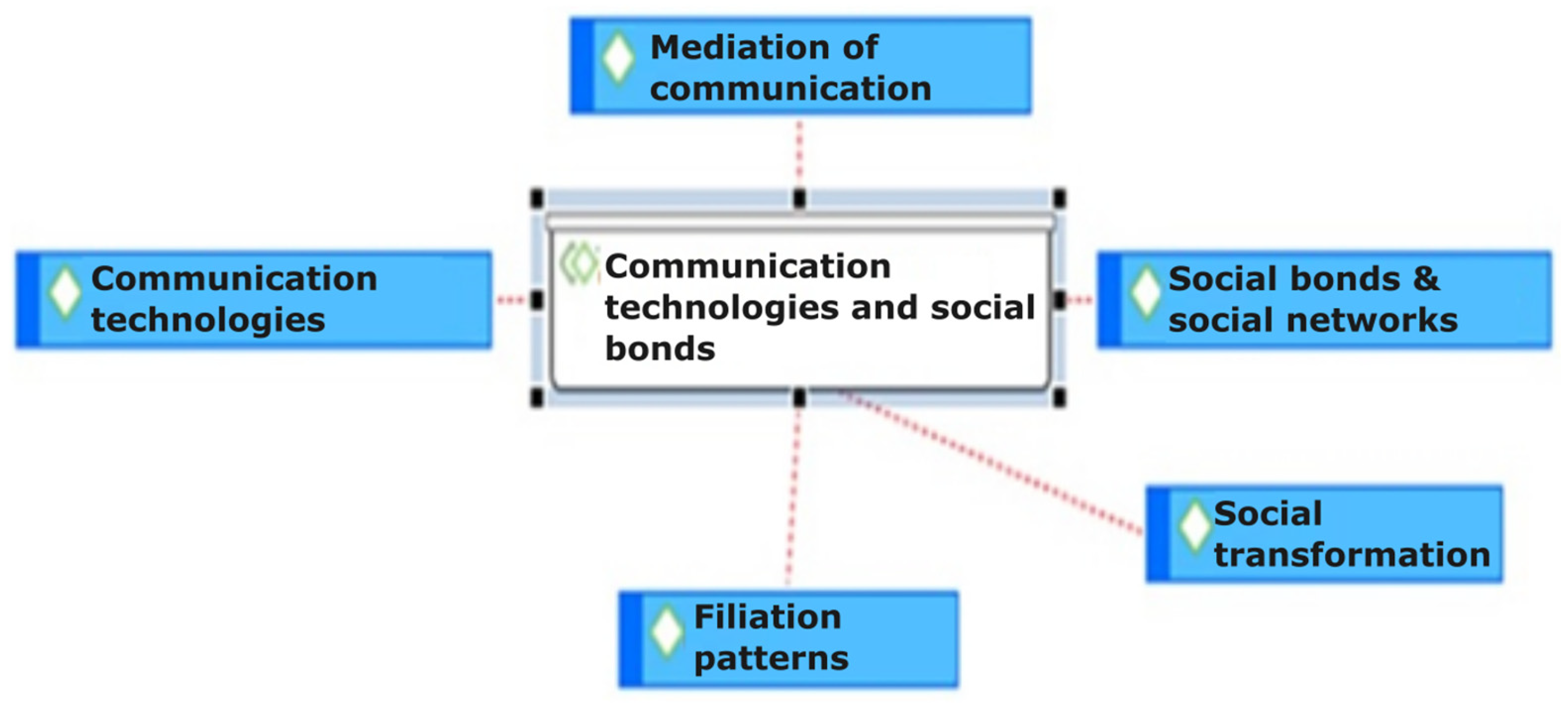

2.2. Technologies of Communication and the Social Bond: Mediation of Communication

2.3. Edutainment, Learning and the Transformation of Thought

2.4. The Influence of Edutainment in Emotion and Learning

2.5. Edutainment and Human Interaction

2.6. Serious Games and Theories of Motivation and Persuasion

The review of the different ways of approaching games makes it possible to distinguish between games for learning and serious games. The main differences between them are circumscribed in the management of motivation and fun in the games. Learning games are based on motivation and fun to facilitate educational processes. Serious games, on the other hand, require a particular theoretical foundation on which their structure is built and do not depend on fun, since motivation is handled from theories of persuasion.(p. 11)

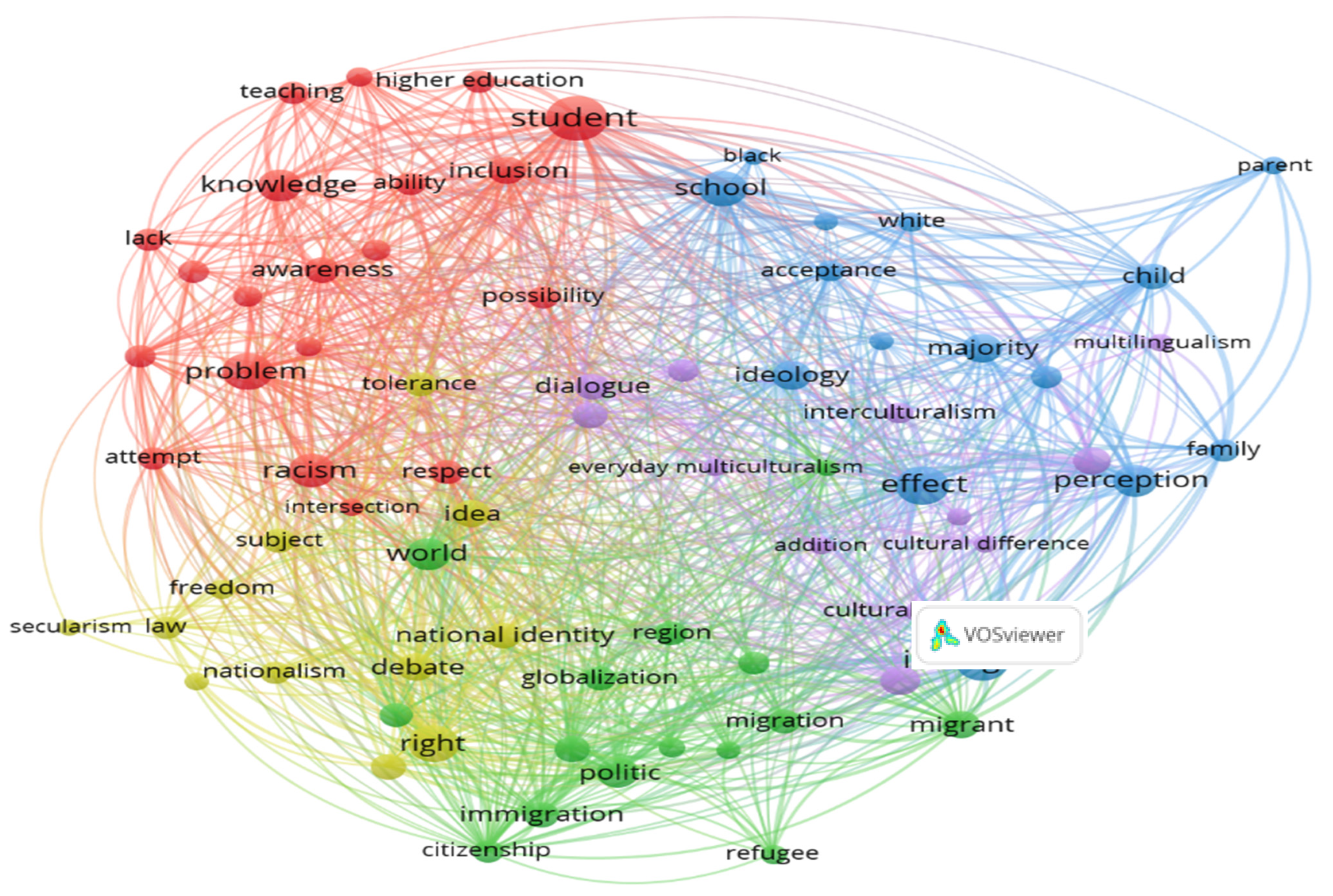

3. Method

Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Convergences of Technologies of Communication and the Social Bond: Mediation of Communication

4.2. Edutainment, Learning and the Transformation of Thought: Contribution of Education

4.3. The Influence of Edutainment in Emotion and Learning: Convergences from Psychology

4.4. Edutainment and Human Interaction: Convergences from Sociology and Psychology

4.5. Convergences: Serious Games and Theories of Motivation and Persuasion

4.6. Convergences of Edutainment and Coexistence: Background

4.7. Categories and Indicators of Coexistence and Otherness

4.8. Convergences

4.9. Convergences Rather Than Interdisciplinarity

4.10. Coexistence and Otherness Convergences from Communication and Edutainment (Serious Games)

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguaded Gómez, Ignacio, and Mary Carmen Caldeiro Pedreira. 2017. ¿Autonomía o subordinación mediática? La formación de la ciudadanía en el contexto comunicativo reciente. Diálogos de la Comunicación 93: 2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, Icek, and Martin Fishbein. 1980. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Alian, Sanaz, and Stephen Wood. 2019. Stranger adaptations: Public/private interfaces, adaptations, and ethnic diversity in Bankstown, Sydney. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 12: 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMarshedi, Alaa, Wills Gary, and Ranchhod Ashok. 2015. The Wheel of Sukr: A framework for gamifying diabetes self-management in Saudi Arabia. Procedia Computer Science 63: 475–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altheide, David. 2019. Media Worlds in the Postjournalism Era. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Noel. 2019. Competitive intervention, protracted conflict, and the global prevalence of civil war. International Studies Quarterly 63: 692–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bammer, Gabrielle. 2017. Should we discipline interdisciplinarity? Palgrave Communications 3: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 2003. Social cognitive theory for personal and social change by enabling media. In Entertainment-Education and Social Change. London: Routledge, pp. 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Barabas, Alicia. 2014. Multiculturalismo, pluralismo cultural e interculturalidad en el contexto de América Latina: La presencia de los pueblos originarios. Configurações. Revista de Sociología, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2006. Modernidad Líquida. Ed. Fondo de Cultura Económica. México: Mexican Government. [Google Scholar]

- Bayón, María Cristina, and Gonzalo Saraví. 2019. Presentación. Desigualdades: Subjetividad, otredad y convivencia social en Latinoamérica. Desacatos, 8–15. Available online: https://bit.ly/2Wpem0t (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Bekerman, Zvi. 2007. Rethinking Intergroup Encounters: Rescuing Praxis from Theory, Activity from Education, and Peace/Co-Existence from Identity and Culture. Journal of Peace Education 4: 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekus, Nelly. 2017. Constructed ‘Otherness’? Poland and the Geopolitics of Contested Belarusian Identity. Europe-Asia Studies 69: 242–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berelson, Bernard. 1952. Content Analysis in Communication Research. New York: Free Press, APA Psycnet. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, Patrik, and Elaine Doyle. 2017. Individualising gamification: An investigation of the impact of learning styles and personality traits on the efficacy of gamification using a prediction market. Computers & Education 106: 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, Carsten, Claßnitz Sabine, Selmanagic Andre, and Steinicke Martin. 2015. Developing and testing a mobile learning games framework. Electronic Journal of e-Learning 13: 151–66. [Google Scholar]

- Canaza-Choque, Franklin. 2018. La sociedad 2.0 y el espejismo de las redes sociales en la modernidad líquida. Crescendo 9: 221–47. [Google Scholar]

- Castaño, Lucía. 2015. Relaciones e interacciones parasociales en redes sociales digitales. Una revisión conceptual. Revista ICONO14 Revista Científica de Comunicación y Tecnologías Emergentes 13: 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaskin, Robert, Bong Joo Lee, and Surinder Jaswal, eds. 2019. Social Exclusion in Cross National Perspective: Actors, Actions, and Impacts from above and below. International Policy Exchange; Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, Thomas. 2012. A systematic literature review of empirical evidence on computer games and serious games. Computers & Education 59: 661–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova, Paula, Nila En Vigil, and Roberto Zariquiey. 2003. Ciudadanías Inconclusas: El Ejercicio de los Derechos en Sociedades Asimétricas. Lima: Corporación Alemana para el desarrollo. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, Robert. 1999. Communication theory as a field. En: Communication Theory, nº9. Washington, DC: International Communication Association. [Google Scholar]

- De-Marcos, Luis, Domínguez Adrian, Saenz-de-Navarrete Joseba, and Pagés Carmen. 2014. An empirical study comparing gamification and social networking on e-learning. Computers & Education 75: 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delzescaux, Sabine, and Frédéric Blondel. 2018. Aux confins de la Grande Dépendance: Le Polyhandicap, Entre Reconnaissance et Déni D’altérité. París: Eres. [Google Scholar]

- Deusdad, Blanca. 2009. Immigrants a les Escoles. Barcelona: Pagès Editors. [Google Scholar]

- Džinović, Vladimir. 2022. The Multiple Self: Between Sociality and Dominance. Journal of Constructivist Psychology 35: 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquirol, Josep. 2005. Uno Mismo y los Otros: De las Experiencias Existenciales a la Interculturalidad. Madrid: Herder Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Etxeberria, Xavier. 2003. La Ciudadanía de la Interculturalidad. Edited by Nick Vigil and Roberto Zariquiey. Ciudadanías Inconclusas: El Ejercicio de los Derechos en Sociedades Asimétricas. San Miguel: PUCP, GTZ. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, Sigmund. 1917. El tabú de la Virginidad. Obras Completas. Madrid: Editorial Biblioteca Nueva. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa, Juan Luis, and Carmen Pérez. 2018. Collective intelligence: A new model of business management in the big-data ecosystem. European Journal of Economics and Business Studies 4: 201–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frizzarin, Anna, Demo Heydrun, and De Boer Anke. 2022. Adolescents’ attitudes towards otherness: The development of an assessment instrument. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garreta, Jordi. 2004. El espejismo cultural. La escuela de Catalunya ante la diversidad cultural. Revista de Educación 333: 463–80. [Google Scholar]

- Giaccaglia, Mirta A., Ma. Laura Méndez, Alejandro Ramírez, Patricia Cabrera, Paola Barzola, Martín Maldonado, and Pablo Farneda. 2012. Razón moderna y otredad: La interculturalidad como respuesta. Ciencia, Docencia y Tecnología 44: 111–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez, Carlos. 2003. Pluralismo, Multiculturalismo e Interculturalidad. Propuesta de Clarificación y Apuntes Educativos Educación y Futuro: Revista de Investigación Aplicada y Experiencias Educativas nº8. Madrid: Editorial CES Don Bosco-EDEBË, pp. 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- González, Karina, and Francisco Blanco. 2008. Emociones con videojuegos: Incrementando la motivación para el aprendizaje. Teoría de la Educación. Educación y Cultura en la Sociedad de la Información 9: 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granic, Isabella, Lobel Adam, and Engels Rutger. 2014. The benefits of playing video games. The American Psychologist 69: 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Melanie, and Timothy Brock. 2000. The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 79: 701–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudiño-Bessone, Pablo. 2011. Comunidad de lo (im) político: Ser con la otredad. Andamios 8: 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gunesch, Konrad. 2004. Education for cosmopolitanism: Cosmopolitanism as a personal cultural identity model for and within international education. Journal of Research in International Education 3: 251–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttormsen, David. 2018. Advancing Otherness and Othering of the Cultural Other during “Intercultural Encounters” in Cross-Cultural Management Research. International Studies of Management & Organization 48: 314–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, Juho, and Lauri Keronen. 2017. Why do people play games? A meta-analysis. International Journal of Information Management 37: 125–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, Juho, Koivisto Jonna, and Sarsa Harri. 2014. Does gamification work?—A literature review of empirical studies on gamification. Paper presented at the 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, January 6–9; pp. 3025–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, Alexander, Catherine Haslam, Tegan Cruwys, Jolanda Jetten, Sara Bentley, Polli Fong, and Steffens Niklas. 2022. Social identity makes group-based social connection possible: Implications for loneliness and mental health. Current Opinion in Psychology 43: 161–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hense, Jan, Klevers Markus, Sailer Michael, Horenburg Tim, Mandl Heinz, and Günthner Willibald. 2013. Using gamification to enhance staff motivation in logistics. In International Simulation and Gaming Association Conference. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hercman, Adriana. 2016. El Otro, el Semejante, el Prójimo. Buenos Aires: Escuela Argentina de Psicoanálisis. [Google Scholar]

- Hinyard, Leslie, and Matthew Kreuter. 2007. Using narrative communication as a tool for health behavior change: A conceptual, theoretical, and empirical overview. Health Education & Behavior 34: 777–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igartua, Juan José. 2008. Identificación con los personajes y persuasión incidental a través de la ficción cinematográfica. Escritos de Psicología 2: 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igartua, Juan José, and Isabel Barrios. 2012. Changing real-world beliefs with controversial movies. Processes and mechanisms of narrative persuasion. Journal of Communication 62: 514–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igartua, Juan José, and Jair Veja. 2014. Processes and mechanisms of narrative persuasion in entertainment-education interventions through audiovisual fiction. The role of identification with characters. Paper presented at the TEEM’14. Second International Conference on Technological Ecosystem for Enhancing Multiculturality, Salamanca, Spain, October 1–3; pp. 311–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igartua, Juan José, Marañón-Lazcano Felipe, Sánchez-Nuevo Lucía, and Piñeiro-Naval Valeriano. 2021. Capítulo 6.2. El análisis de contenido y su aplicación a entornos web: Un caso empírico. Espejo de Monografías de Comunicación Social, 253–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagušt, Tomislav, Botički Ivica, and S. Hyo-Jeong So. 2018. Examining competitive, collaborative, and adaptive gamification in young learners’ math learning. Computers & Education 25: 444–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanbegloo, Ramin. 2022. Maxima Moralia: Meditations on the Otherness of the Other. London: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, Henry. 2008. Convergence Culture: La cultura de la Convergencia de los Medias de Comunicación. New York: Paidos. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Henry, Ford Sam, and Green Joshua. 2018. Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture. New York: New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jorba, Rafael. 2011. La mirada del Otro: Manifiesto por la Alteridad. Barcelona: RBA Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Kahne, Joseph, Middaugh Ellen, and Evans Chris. 2009. The Civic Potential of Video Games. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, Inmauel. 1994. En Filosofía de la Historia. Bogotá: Fondo de la Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Eric, and Yang Liu. 2019. Conceptualizing the Other in Intercultural Encounters: Review, Formulation, and Typology of the Other-Identity. Howard Journal of Communications 30: 446–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauff, Mathias, Marta Beneda, Stefania Paolini, Michał Bilewicz, Patrick Kotzur, Alexander W. O’Donnell, Clifford Stevenson, Ulrich Wagner Ulrich, and Oliver Christ. 2020. How do we get people into contact? Predictors of intergroup contact and drivers of contact seeking. Journal of Social Issues 77: 38–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, Shivani, Akbulut Bengi, Demaria Federico, and Gerber Julien. 2022. Alternatives to sustainable development: What can we learn from the pluriverse in practice? Sustainability Science 17: 1149–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klock, Ana Carolina, Eetu Wallius, and Hamari Hujo. 2021. Gamification in freight transportation: Extant corpus and future agenda. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 51: 685–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojeve, Alexandre. 1982. La Dialéctica del amo y del Esclavo en: Hegel. Buenos Aires: Ed. La Pléyade. [Google Scholar]

- Koivisto, Jonna, and Juho Hamari. 2014. Measuring flow in gamification: Dispositional flow scale-2. Computers in Human Behavior 40: 133–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivisto, Jonna, and Juho Hamari. 2019. The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification research. International Journal of Information Management 45: 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuter, Mattheuw, Melanie Green, Joseph Cappella, Michael Slater, Meg Wise, Doug Storey, Eddie Clark, Daniel O´keefe, Deborah Erwin, Katleen Holmes, and et al. 2007. Narrative communication in cáncer prevention and control: A framework to guide research and application. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 33: 221–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 1990. Metodología de Análisis de Contenido. Teoría y Práctica. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Kymlicka, Will. 2006. Fronteras Territoriales. Una Perspectiva Liberal Utilitarista. Madrid: Editorial Trotta. [Google Scholar]

- Lacan, Jacques. 1975. El Estadio del Espejo Como Formador de la Función del yo (Je) tal Como se nos Revela en la Experiencia Psicoanalítica. Floresta: Siglo XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Laín Entralgo, Pedro. 1967. Teoría y Realidad del Otro. Madrid: Colección Selecta Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Chang-Shing, Mei-Hui Wang, Ye-Ling Tsai, Wey-Shan Chang, Marek Reformat, Giovanni Acampora, and Naoyuki Kubota. 2020. FML-Based Reinforcement Learning Agent with Fuzzy Ontology for Human-Robot Cooperative Edutainment. International Journal of Uncertainty, Fuzziness and Knowledge-Based Systems 28: 1023–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévinas, Enmanuel, and Esther Cohen. 2000. La Huella del Otro. México City: Taurus. [Google Scholar]

- Lévy, Pierre. 2007. Cibercultura: La Cultura de la Sociedad Digital. Center Research in e-Society (CERe-S) y Anthropos Editorial. Mexico: Iztapalapa. [Google Scholar]

- Lipiński, Arthur. 2020. Constructing ‘the Others’ as a Populist Communication Strategy the Case of the ‘Refugee Crisis’ in Discourse in the Polish Press. In Populist Discourse in the Polish Media. Edited by Agnieszka Stępińska. Varsovia: Faculty of Political Science and Journalism, Adam Mickiewicz University. [Google Scholar]

- López, Valeriano. 1996. Estrecho Adventure. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9swVbKNPspA (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Luhmann, Niklas. 2018. Trust and Power. Cambridge: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Markovich, Dalya. 2018. Culture instead of politics: Negotiating ‘Otherness’ in intercultural educational activity. Intercultural Education 29: 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Barbero. 2000. La Ciudad Entre Medios y Miedos. En Arte y Ciudad. Editorial Facultad de Bellas Artes. Bogotá: Universidad Tadeo Lozano. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Chicón, Raquel, and Estefanía Muriedas Díez. 2019. Alteridad, etnicidad y racismo en la búsqueda de orígenes de personas adoptadas. El caso de España. Revista de Estudios Sociales, 115–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus, Cirit, Jabba Daladier, Erazo-Coronado Ana María, and Campis Rodrigo. 2021. From Gamification to Serious Games: Reinventing Learning Processes. In Pedagogy—Challenges, Recent Advances, New Perspectives, and Applications [Working Title]. London: IntechOpen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, Alfredo. 2021. The Use of The Role Playing Game (RPGAD) as a Mediator For Teaching/Learning about Coexistence Among Religious Diversity. Journal of Inclusive Educational Research 1: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mejía, German, and Felipe Londoño. 2011. Diseño de juegos para el cambio social. Kepes, 135–58. Available online: https://bit.ly/2VSwdN7 (accessed on 28 November 2019).

- Mendoza, Manuela. 2019. To mix or not to mix? Exploring the dispositions to otherness in schools. European Educational Research Journal 18: 426–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Métais, Fabrice, and Mario Villalobos. 2022. Levinas’ Otherness: An Ethical Dimension for Enactive Sociality. Topoi 41: 327–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monereo, Carles. 2007. Hacia un nuevo paradigma del aprendizaje estratégico: El papel de la mediación social, del self y de las emociones. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology 5: 497–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossiere, Geraldine. 2016. The intimate and the stranger: Approaching the “Muslim question” through the eyes of female converts to Islam. Critical Research on Religion 4: 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer-Gusé, Emily. 2008. Toward a theory of entertainment persuasion: Explaining the persuasive effects of entertainment-education messages. Communication Theory 18: 407–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrador, Pau, Antoni Vives-Riera, and Marcel Pich-Esteve. 2022. The Renewal of Festive Traditions in Mallorca: Ludic Empowerment and Cultural Transgressions. In Festival Cultures. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 227–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, Guillermo, Rebeca Padilla, D. Moreno González, Hugo Gabriel García, and Franco Darwin. 2011. La investigación de la recepción y sus audiencias. Hallazgos recientes y perspectivas. En Análisis de recepción en América Latina: Un recuento histórico con perspectiva a futuro. pp. 227–66. Available online: https://biblio.flacsoandes.edu.ec/libros/digital/49781.pdf.EdicionesCiespal.org (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- O’Sullivan, Patrick, and Caleb Carr. 2018. Comunicación masiva: Un modelo que salva la división interpersonal de masas. New Media & Society 20: 1161–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios Oviedo, Samuel. 2022. El ejercicio de la ciudadanía en la web 2.0: Presupuestos para la efectividad de la ciudadanía digital. Repositorio Universidad Libre. Available online: https://repository.unilibre.edu.co/handle/10901/20682 (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Pérez-Latre, Francisco. 2004. Ciudadanía, educación y estudios de comunicación. Comunicar 11: 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perosanz, Juan Jose. 2011. Mejor convencer entreteniendo: Comunicación para la salud y persuasión narrativa. Revista de Comunicación y Salud: RCyS 1: 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Petrucco, Corrado, and Daniele Agostini. 2016. Teaching Cultural Heritage using Mobile Augmented Reality. Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society 12: 115–28. [Google Scholar]

- Polhuijs, Zeger. 2018. Review: Zygmunt Bauman, Retrotopia. Theory, Culture & Society 35: 339–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, María, and Juan Jose Igartua Perosanz. 2014. Análisis de las interacciones entre personajes inmigrantes/extranjeros y nacionales/autóctonos en la ficción televisiva española. Disertaciones: Anuario Electrónico de Estudios en Comunicación Social 7: 136–59. [Google Scholar]

- Reguillo, Roxana. 2005. Nosotros, los otros y los miedos. Inseguridad (es), alteridad (es), desconfianza (s). In IV Jornadas de Sociología de la UNLP 23 al 25 de Noviembre de 2005 La Plata, Argentina. La Argentina de la Crisis: Desigualdad Social, Movimientos Sociales, Política e Instituciones. Buenos Aires: Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación, Departamento de Sociología. [Google Scholar]

- Reinemann, Carsten, Stanyer James, Aalberg Toril, Esser Frank, and Clais de Vreese. 2019. Comprehending and investigating populist communication from a comparative perspective. In Communicating Populism Comparing Actor Perceptions, Media Coverage, and Effects on Citizens in Europe. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin, Jeremy. 2000. La era del Acceso: La Revolución de la Nueva Economía. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Martín, Pescador José, and Fernández Pablo. 2006. Presentación. Interculturalismo, ciudadanía cosmopolita y educación intercultural. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 20: 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Rodríguez, Luis Miguel, Torres-Toukoumidis Angel, and Aguaded Ignacio. 2017. Ludificación y educación para la ciudadanía. Revisión de las experiencias significativas. Educar 53: 109–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Rodríguez, Luis Miguel, Sabina Civila, and Ignacio Aguaded. 2020. Otherness as a form of intersubjective social exclusion: Conceptual discussion from the current communicative scenario. Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society 19: 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundell, John. 2004. Strangers, citizens and outsiders: Otherness, multiculturalism and the cosmopolitan imaginary in mobile societies. Thesis Eleven 78: 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabido, Miguel. 2004. The Origins of Entertainment-Education. In LEA’s Communication Series. Entertainment-Education and Social Change: History, Research, and Practice. Edited by Arving Singhal, Michael Cody, Everett Rogers and Miguel Sabido. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Routledge, pp. 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Edwuard. 2015. The Myth of Clash of Civilizations. Disponible en Inglés en. Available online: http://www.mediaed.org/assets/products/404/transcript_404.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Sailer, Michael, Hense Jan, Mayr Sarah, and Mandl Heinz. 2017. How gamification motivates: An experimental study of the effects of specific game design elements on psychological need satisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior 69: 371–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, Sergio, Mannarini Terri, Avdi Evrinomi, Battaglia Fiorella, Cremaschi Marco, Fini Viviana, Forges Guglielmo, Kadianaki Irini, Krasteva Anna, Kullasepp Katrin, and et al. 2019. Globalization, demand of sense and enemization of the other: A psychocultural analysis of European societies’ sociopolitical crisis. Culture & Psychology 25: 345–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanvicén-Torné, Paquita, Fuentes Moren Concxa, and Molina-Luque Fidel. 2017. Ante la diversidad: ¿Qué Opinan y Sienten los Adolescentes? La Alteridad y la Interculturalidad a Examen. Revista Internacional de Sociología de la Educación 6: 26–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolari, Carlos. 2008. Hipermediaciones: Elementos para una Teoría de la Comunicación Digital Interactiva. Barcelona: Editorial Gedisa. [Google Scholar]

- Scolari, Carlos. 2009. On convergence(s) and rapprochement(s): Theoretical discussions, conceptual differences, and transformations in the media ecosystem. Signo y Pensamiento 28: 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Scolari, Carlos. 2013. Narrativa Transmedia. Cuando Todos los Medios Cuentan. Barcelona: Planeta. [Google Scholar]

- Sealy, Thomas. 2018. Multiculturalism, interculturalism, ‘multiculture’ and super-diversity: Of zombies, shadows and other ways of being. Ethnicities 18: 692–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenhav, Yehouda, and Yossi Yonah. 2005. What Is Multiculturalism? On the Politics of Identity in Israel. Tel Aviv: Bavel. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Skovgaard-Smith, Irene, Soekijad Maura, and Down Simón. 2020. The Other side of ‘us’: Alterity construction and identification work in the context of planned change. Human Relations 73: 1583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, Michael, and Donna Rouner. 2002. Entertainment-education and elaboration likelihood: Understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Communication Theory 12: 173–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shohat, Ella, and Robert Stam. 2003. Multiculturalism, Postcoloniality, and Transnational Media. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Chia-Hao, and Ching-Hsue Cheng. 2015. A mobile gamification learning system for improving the learning motivation and achievements. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 31: 268–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabbaa, Luma, Ang Chee, Siriaraya Panote, She Wan, and Prigerson Holly. 2021. A Reflection on Virtual Reality Design for Psychological, Cognitive and Behavioral Interventions: Design Needs, Opportunities and Challenges. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 37: 851–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, Tzvetan. 1991. Nosotros y los Otros: Reflexión Sobre la Diversidad Humana. Floresta: Siglo XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann, Eric, Ebersole Charles, Chartier Christopher Errington, Timothy Kidwell, Mallory Lai, Calvin Mc Carthy Randy, Riegelman Amy, Silberzahn Raphael, and Nosek Brian. 2019. Scientific utopia III: Crowdsourcing science. Perspectives on Psychological Science 14: 711–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Anker, Christien. 2010. Transnationalism and cosmopolitanism: Towards global citizenship? Journal of International Political Theory 6: 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Hove, Sybille. 2006. Between consensus and compromise: Acknowledging the negotiation dimension in participatory approaches. Land Use Policy 23: 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, Teun. 2019. Macrostructures: An Interdisciplinary Study of Global Structures in Discourse, Interaction, and Cognition. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Van Roy, Rob, and Bieke Zaman. 2018. Unravelling the ambivalent motivational power of gamification: A basic psychological needs perspective. International Journal of Human Computer Studie 127: 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, Lisa, Jacquez Farrah, Lindquist-Grantz Robin, Parsons Allison, and Melink Katie. 2017. Immigrants as research partners: A review of immigrants in community-based Participatory research. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 19: 1457–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesa, Mikko, J. Hamari Juho, Harviainen Tuomas, and Warmelink Harald. 2017. Computer games and organization studies. Organization Studies 38: 273–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, Cecilia, Álvarez Ibis, and Vaquera Elizabeth. 2016. Amistades Coétnicas e Interétnicas en la Adolescencia: Diferencias en Calidad, Conflicto y Resolución de Problemas. Educación XXI, [s.l.], v. 20, n. 1. Available online: https://bit.ly/3qTntV6 (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Watson, William, Mong Christopher, and Harris Constance. 2011. A case study of the in-class use of a video game for teaching high school history. Computers & Education 56: 466–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendorf, Jessica. 2016. Beyond Passive Entertainment: Evaluating the Role of Active Entertainment-Education in the Prevention of Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, David, Squire Kurt, Halverson Richard, and Gee James. 2005. Video games and the future of learning. Phi Delta Kappan 87: 104–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Liu, Xaioming Zheng, Xin Liu, Chang Lu, and John Schaubroeck. 2020. Abusive supervision, thwarted belongingness, and workplace safety: A group engagement perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology 105: 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Elaine, Miao Feng, and Xiyuan Liu. 2017. The Revolution of civic engagement: An exploratory network analysis of the Facebook groups of occupy Chicago. Information, Communication & Society 22: 267–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigler, Eduard, and Sandra Bishop-Josef. 2004. Play under siege: A historical overview. In Children’s Play: The Roots of Reading. Washington, DC: National Center for Infants, Toddlers and Families, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

| Database | Papers Account |

|---|---|

| Dialnet | 5 |

| Jstor | 36 |

| Redalyc | 11 |

| Sage | 9 |

| Scopus | 97 |

| Springer | 7 |

| Web of Science | 102 |

| Total | 267 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mateus De Oro, C.; Campis Carrillo, R.M.; Aguaded, I.; Jabba Molinares, D.; Erazo Coronado, A.M. 2.0 Society Convergences: Coexistence, Otherness, Communication and Edutainment. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100434

Mateus De Oro C, Campis Carrillo RM, Aguaded I, Jabba Molinares D, Erazo Coronado AM. 2.0 Society Convergences: Coexistence, Otherness, Communication and Edutainment. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(10):434. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100434

Chicago/Turabian StyleMateus De Oro, Cirit, Rodrigo Mario Campis Carrillo, Ignacio Aguaded, Daladier Jabba Molinares, and Ana María Erazo Coronado. 2022. "2.0 Society Convergences: Coexistence, Otherness, Communication and Edutainment" Social Sciences 11, no. 10: 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100434

APA StyleMateus De Oro, C., Campis Carrillo, R. M., Aguaded, I., Jabba Molinares, D., & Erazo Coronado, A. M. (2022). 2.0 Society Convergences: Coexistence, Otherness, Communication and Edutainment. Social Sciences, 11(10), 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100434