1. Introduction

In the ancient world, myths and rituals around urban institutions, walls, gates, and public spaces conveyed a sense of security for citizens, setting them up with a knowable universe (

Rykwert 1988). In the neoliberal present, cities have become realms of “urban ecological security” (

Hodson and Marvin 2010, p. 194) under the threat of climate collapse. Accompanied by apocalyptic narratives in scientific reports, media, and films (

Harper 2020, p. 56), cities around the world have implemented strategies for mitigation and adaptation to “secure their ecological and material reproduction” (

Hodson and Marvin 2010, p. 194). Among other solutions, urban planners have integrated green infrastructures into the urban landscape, including parks and ecological corridors, to restore floodplains, mitigate the urban heat island effect, and improve coastal resiliency (

EPA 2016;

European Union et al. 2011). Geographer Earl T. Harper argues these large-scale projects often capitalize on collective anxieties about environmental collapse. The author maintains that, under narratives of emergency and apocalyptic futures, specific urban interventions that would be difficult or take longer to realize under ordinary circumstances might become feasible. According to Harper, “The disaster serves to reinvigorate flows of capital by providing an ‘ideological tabula rasa’ upon which to install new ideas” (

Harper 2020, p. 59). Research has also demonstrated that climate-change-driven urban interventions can have adverse effects (

Anguelovski et al. 2019;

Shokry et al. 2020;

Thomas and Warner 2019): on the one hand, they may cause displacement of vulnerable populations and trigger gentrification processes; on the other hand, techno-driven approaches risk dismissing the sociocultural consequences of urban interventions.

As an entry point to these dynamics, we analyze the East Side Coastal Resiliency (ESCR) Project in New York, which has become controversial ground for opposing interests and perspectives, creating a divide between the city government and local communities. In 2012, Hurricane Sandy devastated New York City, killing 44 people and destroying entire neighborhoods. The storm caused approximately

$19 billion in damages (

Letzter 2016). New York City received

$3 billion in relief from the federal government and initiated a process to assess climate change vulnerabilities (

DuPuis and Greenberg 2019). In 2013, the Hurricane Sandy Task Force of the US Department of Housing and Urban Development launched “Rebuild by Design,” an architecture competition to design a portfolio of climate-change-related mitigation projects to prevent flooding while safeguarding public waterfront access. Ten architecture teams presented their plans for building a more resilient Sandy-affected region, and seven of them resulted in winners. The Danish architecture firm BIG-Bjarke Ingels Group designed the Lower Manhattan resiliency plan, also called The BIG “U” for its U shape that runs from East 25th Street south to the Lower East Side of Manhattan, encompassing the Seaport and the Financial District. More than 110,000 New Yorkers live in the area, including approximately 28,000 residents in the low-income housing complexes of the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), the largest public housing authority in North America (

Michaels 2021).

After years of participatory planning projects by local communities before (2004–2013) and during (2013–2015) the development of The BIG “U”, in October 2018, the Mayor De Blasio administration presented a new project for the ESCR Project, the stretch of The BIG “U” running from 25th Street south to Montgomery Street. The project significantly departed from all existing proposals. New York City’s technicians and consultants justified the changes with technical motivations. However, this new plan has not gained the approval of the broader community affected by it. After the deliberation, some community members mobilized to denounce the project as ecocidal, gentrifying, and impacting the underrepresented populations living along the East River. Although managing to delay its construction, these mobilizations have not succeeded in stopping it. Nevertheless, they have raised public awareness around New York City’s lack of transparency and accountability and the environmental injustice the project might engender. Using on-the-ground field research and primary and secondary sources, we assess the social complexities of design for climate change in dense urban settings, where different perspectives, forms of expertise, technical constraints, and rights are involved.

2. Materials and Methods

In this research, we applied mixed methods, including archival and ethnographic fieldwork, and visual analysis. This approach, we argue, is critical to analyzing urban design in the context of the climate change emergency and the need for people’s participation to avoid reproducing social and physical vulnerability.

We studied official documentation such as technical reports, design project presentations, newspapers, pamphlets, and social media releases by governmental institutions (New York City Departments of Parks and Recreation, Design and Construction, and Environmental Protection), community and political groups (OUR Waterfront, Blueway), architecture firms (BIG, OMA, PennDesign), and certain activist organizations (East River Park Action, 1000people1000trees, Friends of East River Park, East River Alliance, Sixth Street Center). We supplemented these archives with qualitative fieldwork, interviews with the aforementioned activist groups, the analysis of everyday spatial practice, and participant observations in key construction sites along the New York East River Park—officially called John V. Lindsay East River Park.

The combination of these methods responds to the recent call for more ethnography in urban and regional studies and geography (

Koster 2020;

Thieme et al. 2017). Ethnographic fieldwork allows scholars to grasp the multi-temporality of urban planning as residents’ temporal frames differ from those of planners and their projects (

Abram and Weszkalnys 2013;

Miraftab 2017). Waiting and uncertainty are often central in people’s temporal experience of urban planning (

Koster 2020). Second, we used open-ended interviews with specific groups of activists to reconstruct the years of participatory planning processes concerning the East Side Waterfront. Rather than sample-based logic, we drew on logical inference (

Small 2009) to identify the main factors influencing knowledge, lives, and imagination around climate urbanism in the neoliberal present.

Beyond this introduction and the methods section, this article contains four different sections and a conclusion.

Section 3 starts with an overview of recent literature tackling design for climate change and its connection to questions of climate justice—procedural (equity in urban decision-making processes) and distributive (assessing vulnerability by climate urbanism). In

Section 4, we run a comparative analysis of urban projects elaborated on by New Yorkers and the New York City government addressing the East Side Waterfront since 2009. We studied the projects’ features, variety of interests involved, and forms of knowledge and communication mobilized. After the 2012 Hurricane Sandy, these projects started to explicitly address climate change. They include two community plans (a “People’s Plan” and the “East River Blueway Plan”), The BIG “U”, and the ESCR Project. As stated before, the latter, currently under construction, has caused civil dissent because it diverges from previous projects and neglects the voices of many local communities. In

Section 5, we analyzed the various claims by certain activist groups through ethnographic methods (on-site and virtual).

Section 6 presents the main stakes of the ESCR Project based on the evidence and filter of urban theories of participatory planning, climate urbanism, and environmental justice. In conclusion, we reflect on the implications of green infrastructure and democratic urban planning in the comparative study of design for climate change and its entanglement with climate justice in urban settings.

3. Designing for Climate Change

Cities are points of egress to the world’s ecosystems: despite occupying only 3% of the planet’s land area, they are responsible for 60–80% of our energy consumption and 75% of our carbon footprint (

UN-HABITAT 2019;

IPCC 2022). They have become vulnerable spots where urbanization processes and environmental changes are intertwined. As a relatively new field of action, climate adaptation and mitigation strategies are still being developed by urban planners (

IPCC 2007), often acting in contexts where roles, procedures, and responsibilities within the process, especially by city authorities, are unclear. Conceived under states of emergency, the resulting projects may only focus on the physical features of the urban fabric while neglecting broader social, cultural, and political aspects. These interventions risk advancing techno-fixes to punctual problems rather than more comprehensive approaches to urban ecosystems that would ensure long-term sustainability. “Sustainability”, itself, some scholars argue, has become a convenient signifier to “avoiding environmental catastrophe” (

Harper 2020, p. 60). As sustainable agendas generate less opposition from those interested in a more ecologically friendly life (

Harper 2020), they may contribute to removing urban interventions under climate change from political debates.

In this regard, we maintain that it is critical to address large-scale urban projects driven by climate change by analyzing them through the filter of climate justice—here, referred to as both the impact of interventions on local communities and ecosystems, and democratic decision-making processes. Research has shown that climate change mitigation and adaptation policies and projects cause the displacement of vulnerable populations (

Harper 2020;

Dooling and Simon 2016;

Gemenne et al. 2014). This dynamic is often referred to as climate or ecological gentrification (

Harper 2020) and its related forms, including “eco-gentrification”, “green gentrification”, and “environmental gentrification”.

Thomas and Warner explain that adaptation and mitigation projects can also result in the redistribution of climate change threats. Evidence suggests that adaptation and vulnerability are related since adaptive responses may increase vulnerable populations. This is because perceptions of and responses to climate change vulnerability are not neutral, as they are based on existing systems of inequality (

Thomas and Warner 2019). The authors state that the “systemic [re]production of differential vulnerability to climate change” (

Thomas and Warner 2019, p. 56) results from policies and programs intended to protect wealthy and politically connected populations in both the Global North and Global South. Within this context, public participation in urban projects could benefit decision-making processes in various ways (

Uittenbroek et al. 2019)—including establishing acceptance and support of the decision, incorporating local knowledge and expertise, and creating social learning opportunities. Most of all, participatory vulnerability assessment would ensure the inclusion of the voices of underrepresented vulnerable populations (

Wilk et al. 2018;

Pringle and Conway 2012;

Pfefferbaum et al. 2015;

Van Aalst et al. 2008).

In the New York case, participatory planning sessions were run until the city government changed the project’s direction in 2018 in a way that significantly differed from the communities’ decisions. Some residents have welcomed the project, nonetheless, fearing for their lives and assets in an uncertain future. Others reacted with outrage because they considered that many years of community engagement in the design process were neglected without justification or explanation. We discuss their claim in the section “Dissent” after providing an overview of the different phases of the design process.

4. Comparative Analysis of New York East Side Waterfront Projects (2004–Present)

4.1. Community Projects (2004–2013)

Between 2004 and 2013, before the “Rebuild by Design” competition, waterfront planning produced various visions for the Lower East Side. The plans developed by the communities were consistent in the results: participants asked for better connections to the waterfront, more open green space, low- or no-cost recreational amenities, better access to community services and public space, and an extension of the river upland along connecting streets. Among these projects, OUR Waterfront, a coalition of community-based organizations and tenant associations representing Lower East Side residents and Chinatown residents, released “A People’s Plan” in 2009.

1 4.1.1. A People’s Plan (2009)

The People’s Plan (

Figure 1) responded to Mayor Bloomberg’s 2008 plan to develop valuable waterfront land through the East River Esplanade Plan, promoted through the city government’s official economic development not-for-profit organization, the New York City Economic Development Corporation. OUR Waterfront claimed that the plan had not included community inputs or needs via participatory planning. For example, the plans for the park at Pier 42 seemed too high-end and focused on attracting tourists. Additionally, a few community spaces initially planned for pavilions below the Franklin D. Roosevelt East River (FDR) Drive, the highway running adjacent and parallel to the river, were eliminated.

OUR Waterfront focused on documenting the concerns of most low-income working-class residents within rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods. More than 1000 people from local communities were involved in the plan’s development. The coalition conducted 800 surveys, various workshop sessions with 150 participants, and a town hall meeting with 80 participants. The community wanted to prioritize free and low-cost services and retail businesses that would “reflect and will preserve the rich cultural diversity of the surrounding neighborhoods” and “improve the health and quality of life of residents” (

OUR Waterfront Coalition 2009, pp. 26–27). With the assistance of the Pratt Center for Community Development, OUR Waterfront prepared three different options for piers 35, 36, and 42, located in front of the subsidized or rent-regulated housing where most of the communities involved in the planning live. They researched funding sources for each option, including federal, state, and city resources and the revenue generated by prospective small businesses.

Besides developing capital and operating budgets, the coalition proposed models for management and governance. Through financial analysis, business planning, and review of the New York City Economic Development Corporation contracts and financial information, the coalition calculated that the corporation’s plan would cost $85,968,631 more than the People’s Plan. The corporation, New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, and state-city alliance Lower Manhattan Development Corporation responded to OUR Waterfront. In partnership, they developed the Master Plan for Pier 42, eight acres of formerly industrial waterfront land bridging the East River Park with Two Bridges/Chinatown, through community outreach. The Master Plan was completed in 2014, providing a long-term vision for the transformation of the pier, and the construction began in 2021. This plan has been incorporated into the ESCR Project.

4.1.2. East River Blueway Plan (2013)

In the wake of Hurricane Sandy, former Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer, State Assembly member Brian Kavanaugh, and the New York State Department of State’s Division of Coastal Resources commissioned “The East River Blueway Plan”. The plan was presented as a model of civic engagement. Blueway engaged the Dutch engineering firm ARCADIS, responsible for flood planning in the Netherlands; and flood protection, green infrastructure, and salt marshes for wave reduction in post-Katrina New Orleans. The plan included natural beaches and other recreational amenities along the shoreline and wetlands to clean stormwater runoff (

Figure 2). Specifically, it envisioned five different areas of intervention (

WXY Studio 2013).

First, the Blueway Crossing and Flood Barrier footbridge would span the FDR Drive at East 14th Street to improve pedestrian access and protect the Con Ed power station from future floodwaters. Second, Brooklyn Bridge Beach would grant public access to fishing areas, swimming beaches, kayak launches, and educational areas connected by bikeways. Third, the Corlears Hook Bridge would be a newly planted bridge reconnecting Corlears Hook Park and East River Park, currently disconnected. Fourth, the Esplanade Freshwater Wetlands would catch and cleanse stormwater runoff from FDR Drive, which presently discharges directly into the river. Fifth, the Stuyvesant Cove Boat Launch would be a floating dock adjacent to Solar One, an all-native species park, and the first stand-alone solar-powered building designed to be the first phase of a Solar Two pier engineered to rise and fall with the tide. Finally, the Blueway Plan proposed to transform the roof of the Skyport Garage, located at East 23rd Street, into a garden with space for food vendors. The revenue generated by these vendors could help fund the maintenance of Stuyvesant Cove. The East River Blueway Plan was developed in partnership with the Community Boards responsible for the East River Side and the Lower East Side Ecology Center. The promoters said more than 40 other community-based organizations offered suggestions and feedback.

4.2. The BIG “U” (2013–2018)

According to BIG, The BIG “U” should be the outcome of a community-driven design. The Danish team decided to incorporate residents’ ideas into a comprehensive flood protection system that would enable the Lower East Side to become physically and socially resilient. To better understand the local needs, the BIG team examined different community projects elaborated since 2004, including “A People’s Plan” and the “East River Blueway Plan”. The architects also collaborated with 26 community groups on the Lower East Side through workshops to discuss the merits of BIG’s different prototype solutions (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). The selected options were incorporated into BIG’s design proposal to create large-scale protective infrastructure while ensuring meaningful community engagement (what the architects call “social infrastructure”). The designed social infrastructure would offer places for recreational activity. Additionally, a grassy, reinforced hill adjacent to FDR Drive would act as a flood barrier and protect the NYCHA low-income housing complexes, ensuring that the poor would not be left behind. The architects intended to merge ”‘Robert Moses’ hard infrastructure with ‘Jane Jacobs’ locally based, community-driven sensitivity” (

BIG 2013, p. 9).

The BIG “U” followed the waterlogged Dutch model that secured continuity of waterfront access to the community through three landscaped elements for three different compartments: the Battery Berm for the area between Battery Park and Brooklyn Bridge, the BIG Bench for the Two Bridges/Chinatown communities, and the Bridging Berm for East River Park. The Battery Berm was an elevated path for the public to protect the Financial District and transportation infrastructure. The BIG Bench consisted of a continuous 4’ high protective element underneath the elevated FDR Drive, including flip-down barriers and deployable walls and gates that created spaces for socializing, tai chi, skateboarding, and a pool. Finally, the Bridging Berm was raised 14 feet along the FDR Drive, providing areas and piers for fishing and swimming and accommodating existing structures, bike lanes, and sports fields. Through a “reverse aquarium”, visitors could observe tidal variations and sea-level rise. Each element would have a flood-protection zone separated from the others and addressing different community needs, each on its time, size, and investment scale. This strategy would accommodate decisions in different timeframes, compatible with changes in regulations and design requirements in response to climate change.

4.3. The New ESCR Project (2018–Present)

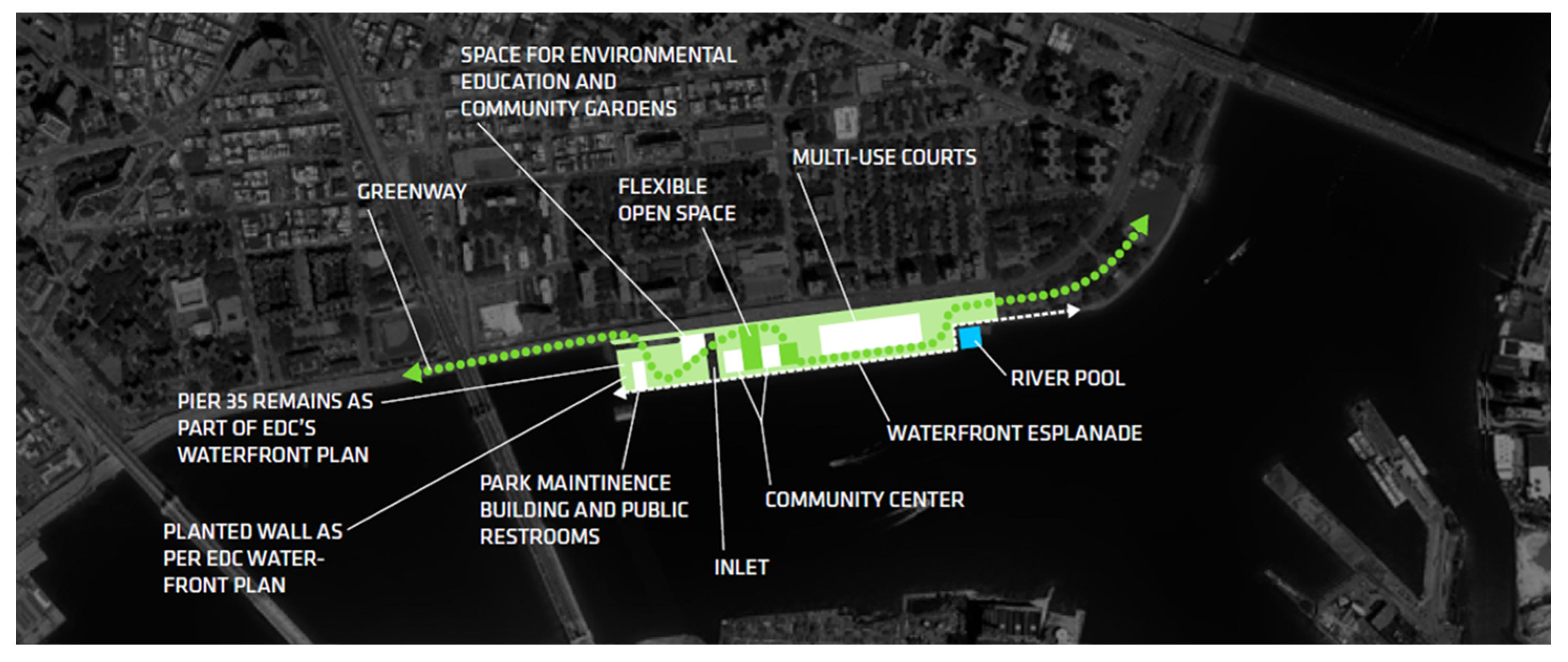

In 2018, the city government announced that The BIG “U” would change course from a system of berms and deployable floodgates along the FDR Drive. Instead, it would involve the demolition, elevation of landfill, and reconstruction on a concrete cap of the existing 60-acre East River Park, set up in 1939 by Robert Moses, to protect the park and the surrounding community from sea level rise and storm surge (

Figure 5). The park would be raised 8 to 10 feet and feature new recreational facilities and 1800 replaced trees of more than 50 species suited to survive occasional saltwater floods.

The city government maintained that radical change to the project was necessary to develop an engineering solution more ambitious than The BIG “U”. Engineers agreed that burying the flood wall under the park and raising the entire park above it would provide the best flood barrier and reduce maintenance costs. This increased efficiency was due, according to the city engineers, to the previously underestimated presence of underground Con Edison transmission lines, 100-plus-year-old water mains, and insufficient sewer capacity.

The New York City Department of Design and Construction, the Mayor’s Office of Resiliency, and the Department of Parks and Recreation led the project team. Other agency partners included the Department of Transportation, the Department of Environmental Protection, the Department of City Planning, and the New York City Economic Development Corporation.

The AKRF-KSE Joint Venture developed the project’s design––from the initial concept of The BIG “U” through to the final design––the environmental review and the permits. This team includes coastal and waterfront engineering experts, urban design, landscape architecture, stormwater management, and community engagement. The NYC Department of Design and Construction selected the HNTB/LiRo Joint Venture as the Program Management/Construction Management consultant. HNTB/LiR’s services include program and project management support, construction management and construction inspection services, management of multi-disciplined professional and technical staff, design oversight and reviews, community engagement, documentation and reporting, scheduling, program status and progress monitoring, cost analysis, construction administration, value engineering, constructability analysis, contract purchasing, and project controls (

NYC 2018b).

Since 2018, many project versions have been layered on top of one another. Disentangling the multi-layered complexity of the design process that ensued is not the aim of this article. However, it is essential to state that if BIG had incorporated the many projects into its preliminary study, the city government, some residents claim, did not explicitly compare the new plan to The BIG “U”, thus making it challenging to find continuities and differences.

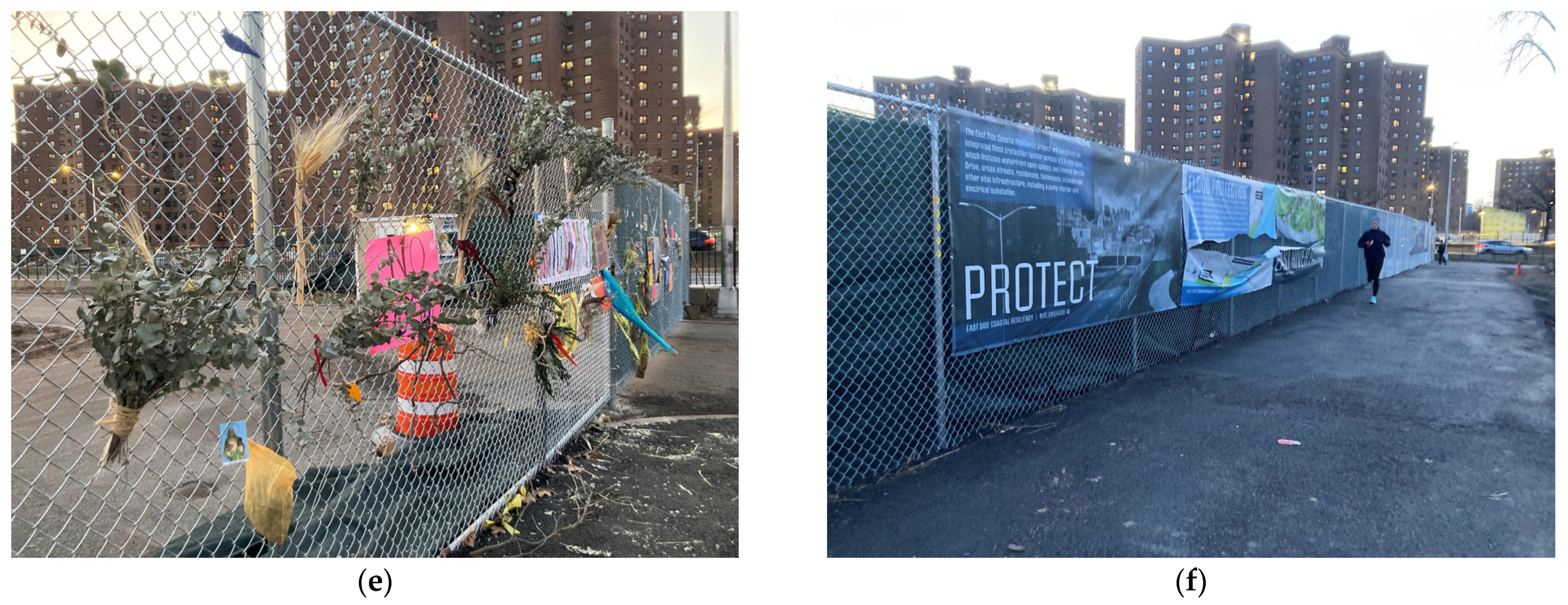

5. Dissent

In 2019, in opposition to the demolition of East River Park, a group of residents formed the nonprofit organization East River Park Action. The members presented a set of demands that included “a plan that provides flood control with minimal destruction of existing parkland and biodiversity … constructed in an environmentally forward-thinking manner that will give us a resilient coastline to help absorb storm surges” (

East River Park Action 2019). The group is actively trying to stop or slow the plan through legal action. East River Park Action has supported the Lower East Side residents and delivered 9000 petitions to City Hall opposing the redevelopment plan in November 2019. The petition included 2000 residents of the NYCHA’s complexes of Lillian Wald, Jacob Riis, and Baruch Houses (

Herman 2019). In February 2020, lawyer Arthur Schwartz from Advocates for Justice filed a lawsuit by 90 plaintiffs on behalf of East River Park Action, opposing the redevelopment of the park because it is hazardous to the environment and health of residents. The Appellate Division, First Department dismissed the lawsuit. The activists then brought the case to the New York Court of Appeals and obtained a restraining order from Judge Rowan Wilson that temporarily halted the construction (

DeGregory 2021). However, the groups denounced that the city government kept cutting trees against the order (

Chang 2021;

Feldman 2021a,

2021b).

The activist organizations, including East River Park Action, 1000people1000trees, Friends of East River Park, East River Alliance, and Sixth Street Center, base their claims on a starting point that the park is currently a daily destination for minority populations in New York (Asian Americans, Latinx, and Afro-Americans). Most of them live in the NYCHA low-income housing projects along FDR Drive (

Figure 6). Additionally, many Asian Americans fish along the river despite being polluted with chemicals.

2 The New York Environmental Justice Interagency Working Group (EGIWJ) designated the Lower East Side as an “environmental justice neighborhood” defined by Local Law 64 § 3-1001 as “[a] low-income community located in the city or a minority community located in the city” (

EGIWJ 2021, p. 7). According to the “New York City’s Environmental Justice for All Report Scope of Work”, the city government should analyze “existing climate risk and run vulnerability assessments, especially those with a focus on human health, safety, and social vulnerability” (

EGIWJ 2021, p. 18).

East River Park is in one of the poorer neighborhoods in the city with less tree cover, across the FDR from city housing projects. The older trees filter pollution and noise from the FDR Drive and provide shade during the summer. According to the interviewed activists, the killing of the existing trees and ecosystems directly impacts vulnerable local communities. Furthermore, the Lower East Side is among the hottest New York City neighborhoods in the summer, and NYCHA residents lack air conditioning. East River Park is a place where they can find solace in the scorching summer days. Heat is the number one climate-related cause of death in New York (

Calma 2021), mainly affecting New Yorkers of color (

Figure 7a).

What follows are the central claims advanced by certain activist groups.

5.1. Lack of Transparency and Accountability

Despite building on community engagement goals, the city government’s project substantially differs from previous approaches. According to specific groups of activists, it was created without any consultation or communication with community stakeholders. Residents continued to provide feedback, but it was rarely incorporated into the plan due to technical rationales. Officials of the city government, however, insisted that the process remained participatory since residents continued to attend and provide feedback at city-organized hearings and meetings (

Araos 2021).

However, even Damaris Reyes, leader of LES Ready—the organization most involved in the original participatory process—and supporter of the new ESCR project, was critical of the city government’s lack of communication and accountability. Specifically, in a public interview, Reyes said, “Right before the plan went into the city’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP), everything stopped. Everyone went quiet. And in September they came out with a totally different plan, and everyone went crazy” (

Araos 2021, p. 17). Additionally, the councilwoman representing Community District 3, Carlina Rivera, and Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer both withdrew their support for the plan for the first few months (

Araos 2021). Sociologist Malcolm Araos, who conducted in-depth research on the participatory planning process before and after 2018, stated that the public expressed negative comments (e.g., see the public comments submitted to the project’s Environmental Review Statement (

NYC Parks and Budget Office 2019). Nearly every participant in the process deemed the city’s plan change undermined the project’s legitimacy (

Araos 2021).

According to the local Sixth Street Community Center, “Resiliency planning must address the root causes of the climate crisis, and it must address the inequitable effects that such plans may have on our most vulnerable, indigenous, Black, communities of color” (quoted in

Furioso 2021). The center contends that the city’s plan maintains the automobile expressway, destroys over 1000 trees, and fails to address the root cause of climate change.

There are also concerns about the increased project costs. The activists recently mobilized to denounce the private sector pushing the city government to increase the budget from

$765 million for The BIG “U” to

$1.5 billion for the ESCR Project while failing to provide detailed analyses on why the cost increase was necessary. They denounced the connection between De Blasio and developers even after the City Conflicts of Interest Board told him to stop because he violated ethics laws (July 2014). For example, in 2017, De Blasio reinstated the 421-A tax exemption plan, renamed the Affordable New York Housing Program. By doing this, he incentivized development without affordable housing, driving gentrification housing (

Keil 2022).

5.2. Public Health

Environmental and public health advocates have expressed serious concerns about the ESCR Project’s potential negative impacts. Residents fear that extensive and prolonged construction spanning the entire project area will impact air quality through soil drifting off the million tons of dirt that will be used to raise the park. The estimated deadline for the construction works for Project Area I (between Montgomery St. and East 15th St) is 2023 but it could be longer. This would worsen asthma cases and particulate matter PM2.5-attributable hospitalization of the residents (

Figure 7b) while also exposing them to noise pollution.

Park defenders from 1000people1000trees stated:

“[T]here are dangerously high levels of contaminants, like lead, in the park. More recent tests have been done; however, the New York City Department of Design and Construction has refused to make them public, and community members have received no response from FOIL [the Freedom of Information Law allows the public to request records from local government agencies]”.

“These dust clouds we see often blowing into our communities [from the construction site], where people live and open area of the park. The contractors are not using basic mitigation methods that can reduce harmful particulate matter, which we especially need because the Department of Design and Construction’s, the City agency carrying out this land grab, own soil report from 2019 says there are high levels of lead and other contaminants in the soil”.

Another primary concern for affected communities is the accessibility of open spaces. East River Park Action objected to the requirement that East River Park must be closed for a minimum of three years, which would result in preventing the public from enjoying the active and passive recreation opportunities that are currently available. For decades, NYCHA residents have been using the park for strolling, running, playing various sports, organizing barbecues and parties, and celebrating major US holidays. As Jasmine Sanchez, NYCHA resident and community organizer stated:

“My family was not a rich family. We did not have the opportunity to travel to places to escape the hustle and bustle of New York City. For the 4th of July, there would always be the fireworks show that we would be able to see from the FDR Drive, so we were there every single year as kids, watching the fireworks, having a barbecue with our neighborhoods and our family, and that was a tie when we would convene as a social network without worrying about not being about to afford anything”.

Howard Brandstein, Executive Director of Sixth Street Community Center, added:

“The community plan was to transform the FDR Drive into a massive transit corridor with clean electric buses and light rail to serve the NYCHA resident far from the subway. That would be a sensible plan for our community”.

The average daily travel on the FDR Drive from the Brooklyn Bridge to East Houston Street in 2019 was 136,000 vehicles per day. Emissions from car traffic along the FDR Drive were 604 metric tons of carbon dioxide daily (220,500 a year). The city would need to plant 10 million trees to offset the yearly carbon emission from the FDR Drive—it would cover an area the size of the Bronx (

Foundation for Renewable Energy and Environment 2021).

5.3. Gentrification, Erasure of Community Memory, and Ecocide

Certain activist groups denounce that the focus on storm surge protection rather than climate justice dislocates the lived experience of the populations impacted. For example, creating selected leisure activities targeting middle-high classes—the park will lose six of eight ballfields and gain 10 tennis courts—might change the configuration of the park’s publics. “Ten years could pass without a completed park”, stated a park defender from 1000people1000trees (interview 2 April 2022), and that would affect at least one generation of athletes in Little League Baseball and Softball, the world’s largest organized youth sports program. To the activists, this dynamic mirrors forms of gentrification through waterfront redevelopment that already occurred in Brooklyn.

East River Park Action also raised concerns that key built features will be compromised despite community opposition. The city government is dismantling 1.4 miles of gardens and fields, an amphitheater, historic buildings, and playgrounds, including

$3 million worth of recent park amenities—including a new soccer field and the running track. For the activists, the ESCR Project fails to commemorate or preserve the park’s history. For example, the historic 1941 amphitheater hosted many artists, including salsa dancer Willie Colon and rapper KRS-One. Joseph Papp, founder of Shakespeare in the Park and the Public Theater, staged “Julius Caesar” there in 1956 (

NYC Department of Parks & Recreation 2022). Most notably, the site was the site of a massacre of approximately 40 individuals of the Wecquaesgeek tribe in February of 1643 (

Cummings-Lambert 2021;

Myles 2021).

Indigenous people have been at the front line of East River Park’s defense (

Myles 2022). Dancer and activist Emily Johnson of the Yup’ik Nation wrote:

“The civil rights and sovereignty of Indigenous peoples will be recognized in relation to land. Power imbalance and extraction will not be the default relationship in our working lives. Theft of, and abuses on, and lack of recognition of Indigenous land, and water, and life will not be tolerated”.

To the Indigenous people, the demolition of the existing park is the result of centuries of colonial settler violence on Indigenous land. On 9 March 2022, at a press conference by 1000People1000Tress, Emily Johnson said:

“Take a moment to register the settler colonial and capitalist mindsets and value systems that continue and have for hundreds of years harmed and killed land, humans and more than human kin right on this spot…Let’s be clear that ESCR is ecocide, and ESCR is a land grab. What is happening here? Deforestation of Manhattan, violence to our more-than-human kin and to our communities, lack of transparency and oversight, lack of any mitigation for the harmful effects of uncovered toxic soil blowing daily into our neighborhoods. While the FDR runs freely, while new towers for wealthier neighborhoods have been pushed through in all the adjacent neighborhoods. We all here know that floodwalls are shortsighted…We all know that fighting water doesn’t work. That soft-edged, rematriating lands, that healthy soil with deep fruits and wetlands is real resiliency. We all here know that community is real resiliency”.

Finally, due to the demolition of green spaces throughout the project area, residents fear that eradicating 1000 mature trees and biodiverse natural habitats will lead to detrimental effects on local flora and fauna and that the new trees planned to be planted will take decades to provide shade, oxygen, or relief to the local community. Park defenders from 1000people1000trees and East River Park Action stated:

“This park will never come back to what it is now. It is unlikely that 1000 80-year-old trees will ever thrive here again after the city kills them. With increased frequency of severe weather events caused by climate change the chances that saplings will survive is much lower, that is why killing 1000 trees can never be the solution. Ecocide can never be a solution. That’s why this is a land grab and not a flood plan”.

(Park defender from 1000people1000trees, interviewed on 5 August 2022)

6. Discussion

6.1. Participatory Planning

Like all planning problems, planning for climate change is what planner Horst Rittel defined as a “wicked problem”. Wicked problems are challenging because any solution causes other issues and affects various actors differently. As Rittel reminded us, solving wicked problems requires considerable time and the participation of multiple forms of expertise. In a wicked problem, knowledge and ignorance are distributed among all participants:

“There is a symmetry of ignorance among those who participate because nobody knows better by virtue of his degrees or his status. There are no experts (which is irritating for experts), and if experts there are, they are only experts in guiding the process of dealing with a wicked problem, but not for the subject matter of the problem”.

The symmetry of ignorance and the need to include different forms of expertise is evident in climate-change-related urban projects, where the stakes (ecological, economic, cultural) are high. Scholars have analyzed the benefits of participatory planning in climate urbanism (

Stewart and Sinclair 2007), calling for participatory assessments of the vulnerable populations affected by the projects. However, depending on how it is run, participatory planning can be used for effectiveness or manipulation. We, here, analyze three critical components of climate urbanism in New York as a wicked problem.

First, concerning the city government’s claims related to participatory planning, certain activist groups have denounced that the ESCR Project neglects the community’s requests to create connections to the waterfront, instead screening the FDR Drive through a berm; and introduces low- or no-cost recreation amenities. For its part, the city government maintains that the project is grounded in a community engagement program since it originated from The Big “U” and incorporated areas designed with the community (e.g., Pier 42). Furthermore, the ESCR Project got consensus from most of the residents’ representatives, and the Community Advisory Group has coordinated and monitored community concerns and needs during the construction phase. Notwithstanding this seemingly community-driven process, there is a stark disagreement between the city government and specific communities.

Second, concerning the effective use of participatory planning, Sherry R. Arnstein reminded us that participating in a process is one thing, but having the power to influence the outcome is another. Using examples from federal programs (e.g., urban renewal, anti-poverty, and Model Cities), Arnstein studied the “significant gradations of citizen participation” (

Arnstein 2019, p. 25). A thorough understanding of these different grades helps understand the ambivalent responses of governments facing grassroots requests. These grades go from the manipulation of citizens to citizens’ control. Drawing on Arnstein’s ladder,

Glucker et al. (

2013) added nine requirements for effective public participation, which they classified into three categories: normative, substantive, and instrumental. The New York case would suggest that the city government has been using participatory planning as instrumental while dismissing the community projects and The BIG “U” that still represented many voices, including those of the experts and the most vulnerable communities, the East River. Different objectives require diverse participatory processes. We maintain that, after having substantially changed, the ESCR Project should have gone through additional community workshops before being realized. These further consultations might have ensured the highest degree of citizens’ control over the project.

Third, there is also dissensus

between communities. We maintain that, by emphasizing the “community” as a homogenous site where development can take place, the community-driven design claimed by the city government has turned the focus away from other scales of repressive structures (

Mohan and Stokke 2000;

Hickey and Mohan 2005)—including race, ethnicity, gender, class, age, and physical ability. On this theme, according to Araos:

Another result was a bitter conflict among neighborhood residents—between those who valued a flawed plan that would still provide flood protection, and those who rejected the city’s new decision-making style and the wholesale destruction of the park.

(p. 28)

[T]he more affluent and white groups purported to speak for the entire relevant community. In the case of the ESCR, older activists in market housing claimed to speak for the entire LES, and claimed that it was in the interests of the entire community to reject the plan. If people disagreed and supported the plan, like public housing representatives did, these people had been manipulated by the city, at least in the eyes of activists.

(p. 29)

What seems to emerge is that many low-income residents of color are afraid of another Hurricane Sandy pro the new ESCR project, and white middle-class residents are against it. The latter denounced that the city manipulated the rest of the residents, many of whom were not aware of the destruction of the current park. Thus, it can be argued that the participatory planning process ended up being manipulative in the sense used by Arnstein. The lack of transparency about the demolition of the existing park, for example, would corroborate that. Additionally, the city did not run a vulnerability assessment that would have clarified all these issues.

Finally, scholars have argued that adaptation planning processes like disaster risk reduction and public health intervention should consider vulnerability as a form of “rights-based justice” (

Adger 2006, p. 277)—the right to live in a safe environment as a universal human right. However, in climate urbanism, there seems to be a diffuse oversimplification of vulnerability into a manageable idea of resilience that dismisses “residents’ values, needs, and experiences” (

Camponeschi 2021, p. 78). While the Rebuild by Design project incorporated social vulnerability, the ESCR Project mirrors the city government’s technocratic approach, minimizing a comprehensive definition and vulnerability assessment and ignoring questions of climate justice (

Smith and Stirling 2010). By dismissing the outcomes of community planning to focus on techno-solutions only, the city government has deployed what Camponeschi calls an “infrastructure-first approach” (

Camponeschi 2021, p. 82).

6.2. Accountability

The US Department of Housing and Urban Development brief for the Rebuild by Design competition had instructed project teams to set new standards for participation through an iterative process of public engagement, emphasizing the need to pay particular attention to “underserved populations” (

Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force 2013, p. 10). All parties had acclaimed the Rebuild by Design project by BIG as a model of community-driven planning that would counter the previous pattern of post-disaster gentrification, including post-Katrina New Orleans and -9/11 (

DuPuis and Greenberg 2019). According to

DuPuis and Greenberg (

2019), the Rebuild by Design project would demonstrate that green infrastructure conceived by world-class designers does not necessarily trigger gentrification and displacement of the poor.

Henk Ovink, the Dutch Special Envoy for International Water Affairs who joined the American recovery effort, presented Rebuild by Design as a model to “bridge the gap between social and physical vulnerabilities” (

Dutch Water Sector 2014). As a co-leader of the BIG Team, Dutch architect and urbanist Matthijs Bouw believed BIG’s project represented a new type of project since it emphasized community engagement and participation in infrastructure planning, a field traditionally dominated by engineers. Scholars examined how BIG’s participatory planning workshops led to this objective through a “new ecology of experts and the public” (

Collier et al. 2016, p. 4).

However, in 2018 the city government conducted a “Value Engineering Study”—a revision of the project aimed at optimizing functional aspects at a lower cost (

NYC 2018c). Since then, the new course of the project has followed a techno-rationality approach driven by engineers that might cause vulnerability, disrupt ecosystems, and trigger gentrification.

6.2.1. Representations

Upon analyzing the project presentations in the archive of the “2018 Design Presentations” (

NYC 2018d) of the ESCR Project, the city government adopted a discontinuity of communication between March 2018 and October 2018. In October 2018, the city government presented the revised version of the ESCR Project to the CB3 Parks Committee by showing a section cut of the landfill upon which the new park would be built. However, from the section, the intention to demolish the existing park to make room for the new one was not clear (

NYC 2018e). Especially unclear was the section cut included in the document for the Interactive Community Engagement Meeting on December 10 (

Figure 8). Compared to realistic 3D representations, which can be easily interpreted independently of expertise, non-experts often find it difficult to understand the real-world implications of a design project because the sections are technical representations. Arguably, the revised course of the ESCR Project was presented in a non-reflexive way as a necessary option based on improved constructability, park resiliency, and a reduced schedule.

Furthermore, no document shared with the community and archived in the “Design Archive” between October 2018 and January 2020—when the Public Commission favorably voted for the project—clearly illustrates the need for massive demolitions. Instead, the demolitions appear in a presentation uploaded in the “2020 Construction Archive” (

NYC 2020), presented to the Parks Committee in January 2020, four days before the project approval by the New York City Design Public Commission (

Figure 9).

However, during the BIG workshops, the community preference was to not see a barrier between the park and the river but instead have direct access to the river. If any uplifting occurred, it should be done by expanding the existing park further to the back on top of FDR Drive through an elevated platform (

Figure 10). This long-term scenario proposed by BIG and selected by the communities would also grant the possibility of shielding the heavy traffic and pollution on the highway. Notwithstanding this, starting in October 2018, the city government presented the project’s updates to the Parks and Land Use Committees, and the Community Boards 3 and 6 of the Lower East Side—advising on land use and zoning, the city government budget, and municipal service delivery.

Noteworthy is that BIG is not mentioned in the revised ESCR Project presentations. This would suggest that the architecture firm was not involved in implementing the project. However, in an ArcDR3 lecture (

xLAB 2021), Jeremy Alain Siegel, one of the two BIG “U” project leaders, presented the renderings of the ESCR elevated park. Despite referring to participatory planning workshops with the communities, he did not discuss the transformation of the original project into the new one, which ignores many of the community’s initial concerns. Unfortunately, this disconnection between design intentions and the reality of realized projects does little to clarify the subordination of architecture practice to economic and political power and interests.

6.2.2. Communications

In 2019, an independent reviewer of the ESRC Project recommended transparency of the processes and involvement of the community (

Deltares 2019). Three years later, in March 2021, the city government released a Value Engineering Study in which journalist Michaela Keil wrote, “Any piece of information that offers discussion on changes from the BIG U/Blueway plan to ESCR is blacked out. Other sections are blurred so that the legibility of the text was compromised” (

Keil 2022, p. 16)”. After the project was announced, a group of Senators, Congresspeople, State Senators, and a State Assemblyman stated that, “after years of working with the community on the previous plan, this unexpected change raises numerous questions about the process by which the city government selected this new proposal and its process for gathering and incorporating public feedback” (

Hoylman 2019). The

Architect’s Newspaper reported a “general discontent” (

Smithson 2022). Conversely developers, such as the engineering/construction firms Jacobs and Hazen and Sawyer and AKRF, spoke positively about the project. Notwithstanding the value engineering, the project costs increased to

$1.45 billion, and only two construction companies bid on the project bringing the budget to

$1.75 billion.

While De Blasio was evasive about the budgeting questions, in July 2021, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer reviewed the integrity, accountability, and fiscal compliance process. While De Blasio evaded questions about the budget, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer reviewed the integrity, accountability, and budgetary compliance process. Singer raised two issues: whether all construction companies involved in the contract had submitted New York City’s disclosure forms and whether minority and women-owned businesses (MWBEs) would be given greater representation in subcontracting—30% instead of 16% (

Feldman 2021a,

2021b). Having passed the 30-day review, the project had to return to the Department of Design and Construction to fix any unresolved issues. However, in August 2021, the city government overruled the Comptroller’s decision. By December 2019, the project received approvals from the New York City Council and the Community Boards 3 and 6.

This ambiguous behavior of the then mayor, De Blasio, regarding a project that might affect vulnerable communities came as a surprise after he had been a defender of the poor since the beginning of his mandate. In his first speech declaring his candidacy, de Blasio argued that, “the government must be the protector of neighborhoods and must guard the people from the enormous power of the moneyed interests.” To do this, he recognized the role of neighborhood groups, including those devastated by Sandy: “Average New Yorkers who simply refuse to allow their community’s voices to be stifled. It’s their spirit that I intend to sweep into City Hall. A spirit that shouts that all boroughs were created equal and that all our residents matter!” (quoted in

Walker 2013).

6.3. Ecocide and the Loss of Urbanity

The biggest claim of certain activist groups, especially 1000people1000trees, is that the ESCR Project is ecocidal. The group firmly opposes the New York remove-and-replace policy for the existing age-old trees instead of a maintain-and-augment one (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). The New York City Urban Forest Agenda (

NYC Urban Forest Task Force 2021) offers two regulatory recommendations for trees on public land:

Encourage canopy expansion through tree protection and enhanced tree replacement requirements on more city-owned properties, and

Include a tree and/or canopy impact analysis during development projects.

However, the first recommendation does not specify how to get tree protection. First, “[e]nhanced tree replacement requirements on more city-owned properties would certainly help reduce the impact of elective tree removals—but reducing the removals themselves would have a greater impact” (

Swett 2022). The second recommendation requires running a canopy impact analysis

during rather than

before the project. However, the post continues: “For regulations to have any teeth in protecting trees, they must require developers, public agencies, and even utilities to accommodate existing trees into their plans” (

Swett 2022).

One of the city government’s rationales for the new ESCR project was that the existing tree species would not have survived incursions from salt water. Sarah Neilson, chief of policy and long-range planning for the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, stated, “They were planted in 1939, and a lot of these trees, their life span is 80 or 100 years, so they’re already kind of starting to falter” (quoted in

Hotakainen 2021). After Sandy, the city government demolished 250 trees that died from saltwater inundation. However, most of the existing trees survived Hurricane Sandy.

On this matter, journalist

Hotakainen (

2021) wrote:

“Amy Berkov, an ecologist at City College of New York who has lived in the East Village since 1979, disputed this, saying the city’s own data showed that 92 percent of the trees were targeted for design reasons, not because of their condition. Her students even measured the diameter of a sampling of trees for a class project and found they had grown by an average of more than 2 inches since 2015”.

Although park defenders from East River Park Action and 1000people1000trees do not talk specifically about it, the Rights of Nature means recognizing that ecosystems and natural communities are not merely property that can be owned. Instead, they are entities with an independent and inalienable right to exist and flourish—non-human agents’ tacit rights (

Variath 2021). Scholars have argued that nature-based solutions represent promising options to protect, manage, and restore natural lands for additional climate mitigation (

Cook-Patton et al. 2021). Instead, by demolishing the existing park, the city government destroys not only ecosystems but also urbanity.

Erasures and reinscriptions of the built environment, like the case of the ESCR Project, can have, as Tony Fry argues,

defuturing effects (

Fry 2020). This means that these top-down interventions, legacies of modernist planning, might contribute to the systemic conditions of structured unsustainability that eliminate possible futures. As human beings are always human-beings-in-place, the destruction of the existing East River Park impacts the meanings, memories, and practices of embodied identities at the core of urbanity (

Seamon 2018). Although the timeframe of an urban intervention may be officially presented as a linear process toward a certain desirable future, the experienced reality for the residents directly affected by it is often one of a long process of discomfort, uncertainty, and repeated setbacks (

Koster 2020) that entirely disrupts the quotidian and contributes to a significant loss of urbanity.

6.4. Gentrification

Logan and Molotch (

2012) have analyzed how even progressive city administrations are influenced by an urban “growth machine” driven by economic and environmental crises increasing inequality in capitalist systems. Semi-privatized forms of infrastructure are tied to market-rate housing developments, contributing to what scholars now refer to as a “green growth machine” or a “resilience growth machine” (

Gould and Lewis 2016). This prioritizes the exchange value of space over the needs of non-wealthy citizens (

Logan and Molotch 2007). Even if there is broad political support from the larger urban polity, projects that do not benefit elite groups will fail (

Logan and Molotch 2007). Consequently, residents are particularly concerned about the lack of inclusion in the redevelopment plans for their communities (

Bullard and Wright 2012).

According to

Gould and Lewis (

2016), neighborhoods with solid community organizations experience less displacement in green gentrification. They manage to ask for projects that are green enough for the neighborhood but not so much that they attract higher-income residents (

Curran and Hamilton 2017). This had been the case with Rebuild by Design. Nevertheless, along the East River, new developments have been recently approved (

Figure 13). These include the luxury housing projects of Essex Crossing/Seward Park by the New York City Economic Development Corporation and the 847-foot-high One Manhattan Square by Extell Development Company. Other planned towers are a 1013-foot-tall tower at 247 Cherry Street by JDS Development Group, two 60-plus-story towers at 260 South Street by the Chetrit Group, and a 62-story, 724-foot rental building at 259 Clinton Street by Starrett Development (

Colman 2022).

Furthermore, under the Permanent Affordability Commitment Together (PACT), the New York City Housing Authority has leased some of its public housing developments in New York to private companies for 99 years. It has privatized the management of the buildings since 2016 (

Adler 2013). According to

Human Rights Watch (

2022), PACT conversions result in residents losing key protections and may have contributed to more evictions in two housing complexes. There is also an unrealized land lease project supporting market-rate residential construction on open space in public housing sites to pay for needed improvements to subsidized units—including the Lower East Side Alfred E. Smith Houses. The infill plan, former City Comptroller John Liu stated, “is similar to upzonings in Brooklyn [zoning changes to allow for more dense use] and will yield a similar crop of lookalike luxury buildings that benefit developers while displacing existing populations” (quoted in

Adler 2013). Although it was not the cause of the aforementioned gentrification dynamics, the ESCR Project may further trigger them. As the NYC High Line project has demonstrated, providing green amenities might increase local property values and result in environmental gentrification (

Black and Richards 2010;

Immergluck and Balan 2018).

7. Conclusions

Under the current threat of climate collapse, urban planners have dealt with the complexities of design for climate change. In this article, we analyzed the case of the East River Side Resiliency (ESCR) Project in New York, which has raised contradictory reactions by local communities. The sudden change to the 2013 Rebuild by Design project introduced by New York City in 2018 raises questions of democratic participatory planning and government’s accountability in climate urbanism and procedures to ensure climate justice for the affected vulnerable population.

In this article, we first offered a review of the current debates around climate urbanism that, we argue, cannot be analyzed apart from climate justice, which recognizes the disproportionate impacts of climate change on specific communities, primarily low-income and ethnic minorities. We compared the various design projects of the East River Side Waterfront, including years of participatory planning processes (2004–2013), the Rebuild by Design project (2013–2018), and the new ESCR Project (2018–present), currently under execution. We then studied the discontent arising around this new project and the claims advanced by certain groups of activists. We concluded that the interruption of communication between New York City and the communities caused suspicions by certain local groups. One of the major issues is that, by not running a vulnerability assessment, the city government did not evaluate the impact of demolishing the existing East River Side on the local populations and existing centennial ecosystems.

We finally examined the significance of historical green infrastructure in the constitutions of urban identities and how the erasure of such spaces might cause a loss of urbanity. As there are different temporalities between residents’ everyday lives and linear engineering approaches, there is also a temporal clash between the time required for democratic city-making and the climate collapse emergency. As architecture critic of

The New York Times Michael Kimmelman stated, “Some environmentalists argue that climate change is a crisis simply too big and fast-moving for the snail’s pace of participatory democracy” (

Kimmelman 2021). We argue that this emergency is sometimes taken as justification to advance techno-solutions that neglect sociocultural aspects in redesigning green urban infrastructures. Finally, by analyzing the current trends in real estate development along the East River Side, we maintain that New York might follow gentrification patterns triggered by climate urbanism that are evident in other urban contexts under the neoliberal present.

Besides adding new data and analysis to the debate around the ESCR project and climate urbanism, this article offers a methodological approach to how to conduct climate urban planning by considering various elements and interests––including social vulnerability, ecosystems demand, and local communities’ needs.