‘Seizing the Window of Strategic Opportunity’: A Study of China’s Macro–Strategic Narrative since the 21st Century

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Concepts and Analytical Framework

2.1. Concept of Strategic Narrative

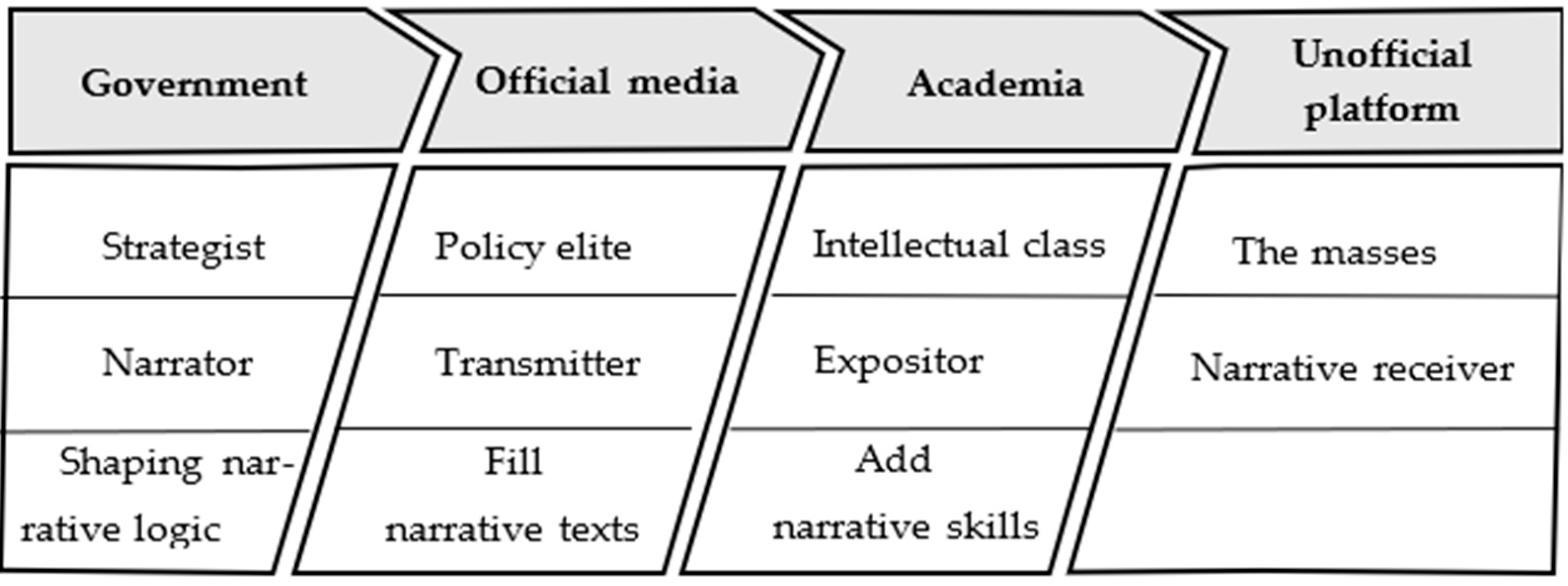

2.2. Narrative Participants and Production Process

2.3. Mechanisms of the ‘Strategic Opportunity Period’ Narrative

3. Temporal Logic and Textual Analysis

3.1. Stage 1 (2002–2011)

‘Looking at the overall situation, the first two decades of the twenty-first century, for China, is an important strategic opportunity period that must be grasped tightly and can make a big difference. … We need to focus our efforts in the first two decades of this century, to comprehensively in the first two decades of this century, we must focus our efforts on building a higher level of well-off society that will benefit more than one billion people’.

‘The world today is undergoing extensive and profound changes, and contemporary China is undergoing extensive and profound changes. The opportunities are unprecedented and the challenges are unprecedented, and the opportunities outweigh the challenges’ (Hu 2007); ‘judging the international and domestic situation, China’s development is still at an important strategic opportunity period where we can make great achievements, facing both rare historical opportunities and many foreseeable and unforeseeable risks and challenges’.(Hu 2011)

‘During this decade, we have seized and used the important strategic opportunity period for China’s development, overcome a series of major challenges. As we enter the new stage of the new century, the international situation is changing and the competition for comprehensive national power is unprecedentedly fierce, we are deepening reform and opening up, taking our accession to the World Trade Organization as an opportunity to turn pressure into motivation, turning challenges into opportunities’.(Hu 2012)

3.2. Stage 2 (2012–2017)

‘Based on the basic features of China’s development environment in the 13th Five-Year Plan period, China’s development is still in a period of important strategic opportunities, but also faces many contradictions overlapping and serious challenges of increasing risks and hidden dangers. We should accurately grasp the profound changes in the connotation of the strategic opportunity period, deal with various risks and challenges more effectively, continue to focus our efforts on getting things done’.(Xi 2015)

3.3. Stage 3 (2017–Present)

‘… According to the profound and complex changes in the development environment faced by our country, the current and future period, China’s development is still in an important strategic opportunity period, but there are new developments in both opportunities and challenges … we need to enhance awareness of opportunities and risks, based on national conditions, maintain strategic determination, do our own business, understand and grasp the laws of development, establish bottom-line thinking … good at nurturing opportunities in crises, opening up situations in changes, seize the opportunity to deal with the challenge’.

4. Empirical Research

4.1. Analysis of Narrative Quantity

4.2. Analysis of Narrative Keywords

5. Discussion: Narrative Philosophy and Dilemmas

5.1. Philosophical Basis of ‘Strategic Opportunity Period’ Narrative

5.2. ‘Strategic Opportunity’ Narratives: Dilemmas and Challenges

6. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allison, Graham. 2017. Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’ Trap? Boston: Houghton Mifflin, pp. 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Amitav, Acharya. 2014. The End of American World Order. Cambridge: Polity Press, pp. 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Berenskoetter, Felix. 2014. Parameters of a national biography. European Journal of International Relations 20: 262–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, Anne-marie. 2009. Mass persuasion as a means of legitimation and China’s popular authoritarianism. American Behavioral Scientist 53: 434–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, Kenneth. 1955. A Grammar of Motives. New York: George Braziller, pp. 12–106. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Kenneth. 1969. A Rhetoric of Motives. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Dejun. 2021. Strategic Narratives in Great Power Competition: The Sino-US Diplomatic Discourse Game and Its Narrative Script. World Economics and Politics 5: 51–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Dejun. 2022. Historical Memory and the Narrative Construction in the South China Sea. The Journal of South China Sea Studies 8: 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Yungyung. 2021. The Post-Pandemic World: Between Constitutionalized and Authoritarian Orders-China’s Narrative-Power Play in the Pandemic Era. Journal of Chinese Political Science 26: 27–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Chaomei, and Min Song. 2019. Visualizing a field of research: A methodology of systematic scientometric reviews. PLoS ONE 14: e0223994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Dingding, and Jianwei Wang. 2011. Lying Low No More? China’s New Thinking on the Tao Guang Yang Hui Strategy. China: An International Journal 9: 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Xiaoping. 1993. Selected Writings of Deng Xiaoping. Beijing: People’s Publishing House, vol. 3, p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- DiPalma, Giuseppe. 1991. Legitimacy from the top to civil society: Politico-cultural change in Eastern Europe. World Politics 44: 49–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Zongxian. 2018. Challenges of ‘anti-globalization’ and opportunities of new globalization. Journal of International Trade 1: 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Fukuyama. 2020. The Pandemic and Political Order. Foreign Affairs 99: 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Jianhua. 2012. A Study of China’s Maritime Political Strategy in the South China Sea—On China’s Role in the South China Sea Dispute. Pacific Journal 20: 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagström, Linus, and Karl Gustafsson. 2019. Narrative power: How storytelling shapes East Asian international politics. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 32: 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, Xing, and Yang Zhou. 2021. Contributing China’s power to UN peacekeeping operations. In Ministry of Defence of PRC. Available online: http://www.mod.gov.cn/action/2021-11/02/content_4898311.htm (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Hu, Jintao. 2007. Full text of Hu Jintao’s report at 17th party congress. China Daily. October 24. Available online: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2007-10/24/content_6204564.htm (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Hu, Jintao. 2011. Full text of Communique of the Fifth Plenum of the 17th CPC Central Committee. People’s Daily. October 18. Available online: http://english.cpc.people.com.cn/66102/7169801.html (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Hu, Jintao. 2012. Full text of Hu Jintao’s report at 18th party congress. People’s Daily. November 19. Available online: http://en.people.cn/102774/8024779.html (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Ikenberry, John. 2020. The End of Liberal International Order? In USA, China and Europe. Edited by Mario Teló and Didier Vivers. Brussels: Academe royal de Belgium, pp. 28–79. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, Jabin T. 2020. ‘To tell China’s story well’: China’s international messaging during the COVID-19 pandemic. China Report 56: 374–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Zeimn. 1999. Jiang Zemin’s speech at Cambridge University: China will never claim hegemony. Sina. October 23. Available online: https://news.sina.com.cn/china/1999-10-23/24792.html (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Jiang, Zemin. 2002. Full text of Jiang Zemin’s Report at 16th Party Congress. Chinadaily. November 8. Available online: http://language.chinadaily.com.cn/2013-11/26/content_17132209.htm (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Jones, Micheal D., and Mark K. McBeth. 2010. A narrative policy framework: Clear enough to be wrong? Policy Studies Journal 38: 329–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Jie, and Hongmei Xu. 2014. Values Reflected in the American and British News Reports on Xinjiang Issues. Journal of Xinjiang University (Philosophy and Social Sciences) 42: 152–6. [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo, Ervin. 1991. The Age of Bifurcation: Understanding the Changing World. London: Gordon & Breach Science Pub, pp. 2–93. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Ning. 2017. The Power of Strategic Narratives: The Communicative Dynamics of Chinese Nationalism and Foreign Relations. In Forging the World: Strategic Narratives and International Relations. Edited by A. Miskimmon, B. O’ Loughlin and L. Roselle. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 110–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lind, Jennifer M. 2020. Narratives and International Reconciliation. Journal of Global Security Studies 5: 229–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Yameng. 2004. The Quest for Symbols of Power—Reflections on Western Rhetorical Thought. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company, pp. 220–21. [Google Scholar]

- Louie, Vivian, and Anahí Viladrich. 2021. ‘Divide, Divert, & Conquer’ Deconstructing the Presidential Framing of White Supremacy in the COVID-19 Era. Social Sciences 10: 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, Honghua. 2020. Expanding and Creating China’s Strategic Opportunities amid the Once-in-a-Century Changes. Journal of Tongji University 31: 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Miskimmon, Alister, Ben O’loughlin, and Laura Roselle. 2013. Strategic Narratives. In Communication Power and the New World Order. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 4–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nye, Joseph S. 2014. The information revolution and soft power. Current History 113: 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Yaqing. 2021. Transformation of the world order: From hegemony to inclusive multilateralism. Asia-Pacific Security and Maritime Affairs 2: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiushi net. 2020. Communique of 5th Plenary Session of 19th CPC Central Committee Released. October 30. Available online: https://en.qstheory.cn/2020-10/30/c_558230.htm (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Schmitt, Olivier. 2018. When are strategic narratives effective? The shaping of political discourse through the interaction between political myths and strategic narratives. Contemporary Security Policy 39: 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, Gunter, and Björn Alpermann. 2019. Studying the Chinese Policy Process in the Era of ‘Top-Level Design’: The Contribution of ‘Political Steering’ Theory. Journal of Chinese Political Science 24: 199–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, Alexander, and Anatoly Tsvyk. 2021. The Approach to the Chinese Diplomatic Discourse. Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences 14: 565–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Hengtan. 2015. The Analects and the Confucian View of Timing and the Biblical View of Timing. Study of Christianity 18: 228–43. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, Jinping. 2015. Xi Jinping’s Speech at the 2015 Military Parade. Chinadaily. Available online: http://language.chinadaily.com.cn/2015-09/03/content_21783129.htm (accessed on 21 July 2022).

- Xi, Jinping. 2018. Xi attended the BRICs business forum and delivered an important speech. People’s daily. July 26. Available online: http://en.people.cn/n3/2018/0726/c90000-9484762.html (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Xi, Jinping. 2021. Xiplomacy: China never seeks hegemony on journey to national rejuvenation. Xinhua. Available online: http://www.news.cn/english/2021-09/30/c_1310220043.htm (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Xinhua net. 2012. Zhang Hua refutes claims that China has escalated tensions between China and the Philippines over Huangyan Island. In Xinhua. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2012-04/24/content_2121026.htm (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Xinhua net. 2014. Xi Jinping Attends Central Foreign Affairs Work Conference and Delivers Important Speech. November 29. Available online: http://news.xinhuanet.com/ttgg/2014/11/29/c_1113457723.htm (accessed on 16 July 2022).

- Xinhua net. 2015. Communiqué of the Fifth Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. October 30. Available online: http://www.beijingreview.com.cn/wenjian/201510/t20151030_800041567_1.html (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Xu, Jian. 2014. Reconceptualizing the strategic opportunity period. China International Studies 2: 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Yilong. 2020. Analysis of China’s ‘Three Circles Theory’ and the Strategic Opportunity Period. Theory Journal 1: 105–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Jinghan. 2017. Does Europe Matter? The Role of Europe in Chinese Narratives of ‘One Belt One Road’ and ‘New Type of Great Power Relations’. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 55: 1162–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Jinghan, Yuefan Xiao, and Shaun Breslin. 2015. Securing China’s Core Interests: The State of Debate in China. International Affairs 91: 245–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Feng. 2015. Chinese Hegemony: Grand Strategy and International Institutions in East Asian History. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 12–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Qingmin, and Yi Edward Yang. 2020. Bridging Chinese Foreign Policy Studies and Foreign Policy Analysis: Towards a Research Agenda for Mutual Gains. Journal of Chinese Political Science 25: 663–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yifei. 2019. New Technological Camouflage of Cold War Thought: Comments on How Artificial Intelligence Will Reshape the Global Order by Nicholas Wright. Contemporary American Review 3: 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yifei. 2020. Analysis of the ‘unprecedented changes of the century’. International Economic Review, 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yunhan, and Jan Orbie. 2021. Strategic narratives in China’s climate policy: Analysing three phases in China’s discourse coalition. The Pacific Review 34: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Juncheng. 2016. The transformation of ideological narratives in social transformation. Seeker, 124–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Yang. 2013. An analysis on commentary frame in Chinese and Filipino media’s coverage on the Huangyan Island dispute. Journalism & Communication 20: 33–49. [Google Scholar]

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time period | 2002–2011 | 2012–2017 | 2018–present |

| Leadership | Hu Jintao | Xi Jinping | Xi Jinping |

| International system narratives | An era of peace and development | An era of opportunities and challenges | An era of unprecedented change |

| Self-identity narratives | A participant in the international system | A builder and maintainer of systemic order | A reformer of the old order |

| Main targets of strategic narrative | Economic empowerment | Enhancing international status | Rise peacefully |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, W. ‘Seizing the Window of Strategic Opportunity’: A Study of China’s Macro–Strategic Narrative since the 21st Century. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100461

Song W. ‘Seizing the Window of Strategic Opportunity’: A Study of China’s Macro–Strategic Narrative since the 21st Century. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(10):461. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100461

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Wenlong. 2022. "‘Seizing the Window of Strategic Opportunity’: A Study of China’s Macro–Strategic Narrative since the 21st Century" Social Sciences 11, no. 10: 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100461

APA StyleSong, W. (2022). ‘Seizing the Window of Strategic Opportunity’: A Study of China’s Macro–Strategic Narrative since the 21st Century. Social Sciences, 11(10), 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100461