Developing Process for Selecting Research Techniques in Urban Planning and Urban Design with a PRISMA-Compliant Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

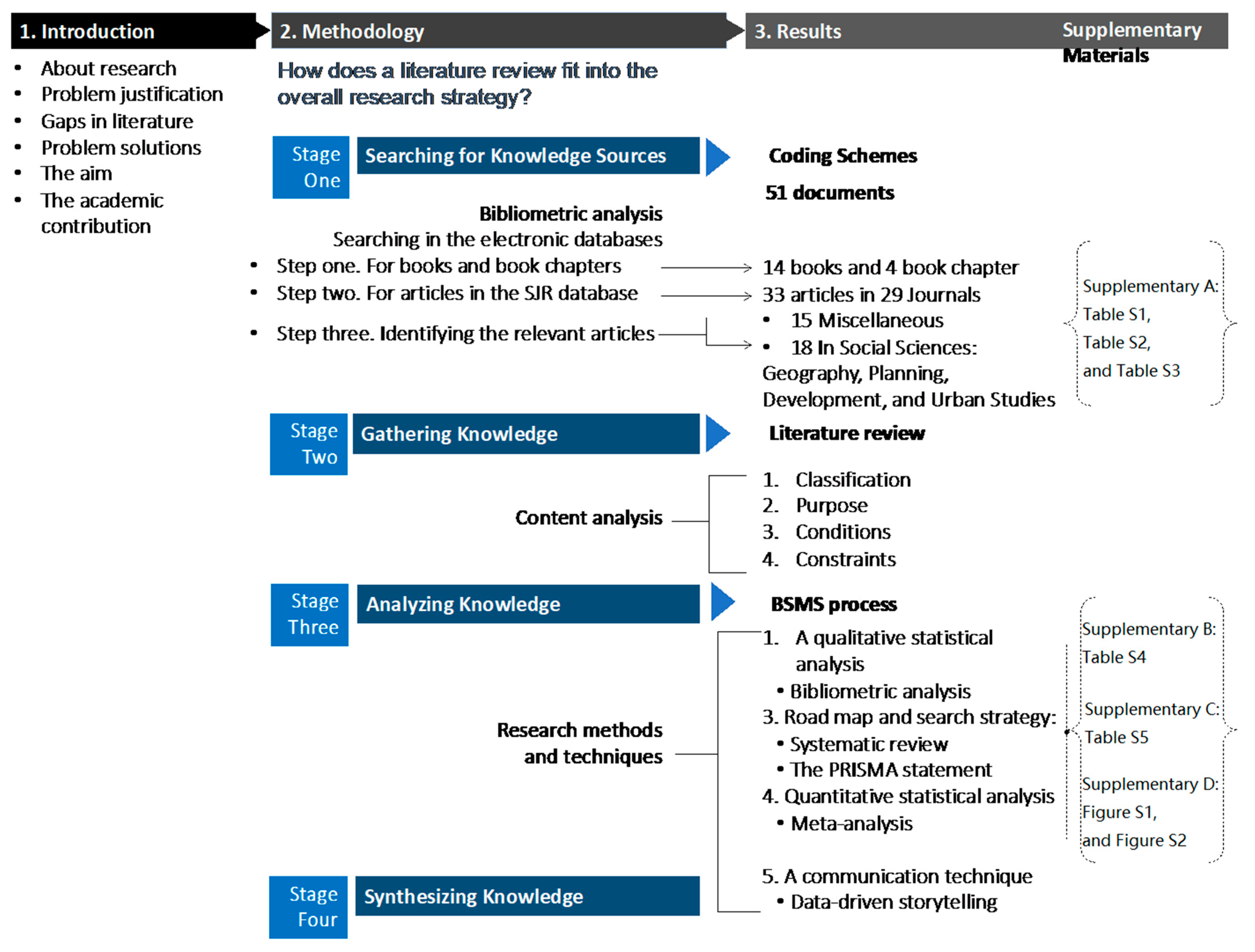

2. Materials and Methods

3. Literature Review

4. Results

4.1. Stage One: Searching for Sources

- Fifteen manuscripts on management control and information systems (Amirbagheri et al. 2019) earth, atmospheric and planetary sciences (Liu and Niyogi 2019), public health (medicine and nursing) (Amirbagheri et al. 2019; Fleming et al. 2014; Garfield 2006; Kastner et al. 2012; Liberati et al. 2009; Moher et al. 2009; Page et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2021), research methods (Arksey and O’Malley 2005; Wiles et al. 2011), and physics (Hirsch 2010); and

- Eighteen manuscripts of social sciences, including geography, planning, development, and urban studies, which are distributed as follows: city planning (AlKhaled et al. 2020; Kwon and Silva 2020; McLeod and Schapper 2020; Navarro-Ligero et al. 2019; Xiao and Watson 2019; Zitcer 2017), urban planning (Chapain and Sagot-Duvauroux 2020; Francini et al. 2021; Özogul and Tasan-Kok 2020; Verweij and Trell 2019; Lim et al. 2019; Pelorosso 2020; Smith et al. 2021; Tarachucky et al. 2021), and urban planning and urban design (Dastjerdi et al. 2021).

4.2. Stage Two: Knowledge Gathering and Content Analysis

4.3. Stage Three: Analyzing Knowledge-Research Methods and Techniques

4.4. Stage Four: Knowledge Synthesis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abusaada, Hisham, and Abeer Elshater. 2020. Addressing the new pragmatically methods in urban design discipline. In Encyclopedia of Organizational Knowledge, Administration, and Technologies. Edited by Mehdi Khosrow-Pour. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 1196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, Hisham, and Abeer Elshater. 2021a. Competitiveness, distinctiveness and singularity in urban design: A systematic review and framework for smart cities. Sustainable Cities and Society 68: 102782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, Hisham, and Abeer Elshater. 2021b. Building sustainable habitats for free-roaming cats in public spaces: A systematic literature review. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abusaada, Hisham, and Abeer Elshater. 2021c. COVID-19 and “the trinity of boredom” in public spaces: Urban form, social distancing and digital transformation. International Journal of Architectural Research: ArchNet-IJAR 16: 172–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, Hisham, and Abeer Elshater. 2022. Notes on developing research review in urban planning and urban design based on PRISMA statement. Social Sciences 11: 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlKhaled, Saud, Paul Coseo, Anthony Brazel, Chingwen Cheng, and David Sailor. 2020. Between aspiration and actuality: A systematic review of morphological heat mitigation strategies in hot urban deserts. Urban Climate 31: 100570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirbagheri, Keivan, Ana Núñez-Carballosa, Laura Guitart-Tarrés, and José M. Merigó. 2019. Research on green supply chain: A bibliometric analysis. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 21: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O’Malley. 2005. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ball, Rafael. 2017. An Introduction to Bibliometrics: New Development and Trends. Zuerich: Chandos Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, Ana, Liezel Frick, Karri Holley, Marvi Remmik, Jakob Tesch, and Gerlese Âkerlind. 2015. The doctorate as an original contribution to knowledge: Considering relationships between originality, creativity, and innovation. Frontline Learning Research 3: 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, Paula, Linda Ng Fat, Leandro M. T. Garcia, Anne Dorothee Slovic, Nikolas Thomopoulos, Thiago Herick de Sa, Pedro Morais, and Jennifer S. Mindell. 2019. Social consequences and mental health outcomes of living in high-rise residential buildings and the influence of planning, urban design and architectural decisions: A systematic review. Cities 93: 263–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, Angela, Gemma Cherry, and Rumona Dickson, eds. 2014. Doing a Systematic Review: A Student’s Guide. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Casanave, Christine Pearson, and Yongyan Li. 2015. Novices’ struggles with conceptual and theoretical framing in writing dissertations and papers for publication. Publications 3: 104–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chapain, Caroline, and Dominique Sagot-Duvauroux. 2020. Cultural and creative clusters—A systematic literature review and a renewed research agenda. Urban Research & Practice 13: 300–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Der-Thanq Victor, Yu-Mei Wang, and Wei Ching Lee. 2016. Challenges confronting beginning researchers in conducting literature reviews. Studies in Continuing Education 38: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocchia, A. 2014. Smart and digital city: A systematic literature review. In Smart City: How to Create Public and Economic Value with High Technology in Urban Space. Edited by R. P. Dameri and C. Rosenthal-Sabroux. Cham: Springer, pp. 13–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastjerdi, Masoud Shafiei, Azadeh Lak, Ali Ghaffari, and Ayyoob Sharifi. 2021. A conceptual framework for resilient place assessment based on spatial resilience approach: An integrative review. Urban Climate 36: 100794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodgson, Joan E. 2020. Quality in research: Asking the right question. Journal of Human Lactation 36: 105–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, Carl, Shima Hamidi, and Reid Ewing. 2020. Validity and reliability. In Basic Quantitative Research Methods for Urban Planners. New York: Routledge, pp. 88–106. [Google Scholar]

- Elshater, Abeer, and Hisham Abusaada. 2022a. From uniqueness to singularity through city prestige. Urban Design and Planning (ICE) 175: 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshater, Abeer, and Hisham Abusaada. 2022b. People’s absence from public places: Academic research in the post-covid-19 era. Urban Geography 43: 1268–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, Reid, and Keunhyun Park, eds. 2020. Basic Quantitative Research Methods for Urban Planners. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, Padhraig S., Despina Koletsi, and Nikolaos Pandis. 2014. Blinded by PRISMA: Are systematic reviewers focusing on PRISMA and ignoring other guidelines? PLoS ONE 9: e96407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francini, Mauro, Lucia Chieffallo, Annunziata Palermo, and Maria Francesca Viapiana. 2021. Systematic Literature review on smart mobility: A framework for future “quantitative” developments. Journal of Planning Literature 36: 283–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, Eugene. 2006. The history and meaning of the journal impact factor. JAMA Journal of the American Medical Association 295: 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, David, Sandy Oliver, and James Thomas. 2017. An Introduction to Systematic Reviews. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Gusenbauer, Michael, and Neal R. Haddaway. 2020. Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed and 26 other resources. Research Synthesis Methods 11: 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ham-Baloyi, Wilmaten, and Portia Jordan. 2016. Systematic review as a research method in post-graduate nursing education. Health SA Gesondheid 21: 120–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harris, Patrick, Ben Harris-Roxas, Jason Prior, Nicky Morrison, Erica McIntyre, Jane Frawley, Jon Adams, Whitney Bevan, Fiona Haigh, Evan Freeman, and et al. 2022. Respiratory pandemics, urban planning and design: A multidisciplinary rapid review of the literature. Cities 127: 103767. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heiberger, Richard M., and Erich Neuwirth. 2009. One-Way ANOVA. In R Through Excel. New York: Springer, pp. 165–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Julian P. T., James Thomas, Jacqueline Chandler, Miranda Cumpston, Tianjing Li, Matthew J. Page, and Vivian A. Welch, eds. 2019. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. London: The Cochrane Collaboration and John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, Jorge E. 2010. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output that takes into account the effect of multiple coauthorship. Scientometrics 85: 741–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hughes, Sara. 2015. A meta-analysis of urban climate change adaptation planning in the U.S. Urban Climate 14: 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastner, Monika, Andrea C. Tricco, Charlene Soobiah, Erin Lillie, Laure Perrier, Tanya Horsley, Vivian Welch, Elise Cogo, Jesmin Antony, and Sharon E. Straus. 2012. What is the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to conduct a review? Protocol for a scoping review. BMC Medical Research Methodology 12: 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khan, Khalid, Regina Kunz, Jos Kleijnen, and Gerd Antes. 2011. Systematic Reviews to Support Evidence-Based Medicine. London: CRC Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Heeseo Rain, and Elisabete A. Silva. 2020. Mapping the landscape of behavioral theories: Systematic literature review. Journal of Planning Literature 35: 161–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leedy, Paul D., and Jeanne Ellis Ormrod. 2018. Practical Research: Planning and Design. New York: Pearson Education, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, Alessandro, Douglas G. Altman, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Cynthia Mulrow, Peter C. Gøtzsche, John P. A. Ioannidis, Mike Clarke, Philip J. Devereaux, Jos Kleijnen, and David Moher. 2009. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine 6: e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Yirang, Jurian Edelenbos, and Alberto Gianoli. 2019. Identifying the results of smart city development: Findings from systematic literature review. Cities 95: 102397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Xu. 2018. Interviewing elites: Methodological issues confronting a novice. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 17: 1609406918770323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Jie, and Dev Niyogi. 2019. Meta-analysis of urbanization impact on rainfall modification. Scientific Reports 9: 7301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- MacCallum, Diana, Courtney Babb, and Carey Curtis. 2019. Doing Research in Urban and Regional Planning: Lessons in Practical Methods. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, Sam, and Jake H. M. Schapper. 2020. Understanding quality in planning consultancy: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Planning Education and Research. Online First. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, David, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Andrea C. Tricco, Margaret Sampson, and Douglas G. Altman. 2007. Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews. PLoS Medicine 4: e78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Douglas G. Altman, and PRISMA Group. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 339: b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Navarro-Ligero, Miguel L., Julio A. Soria-Lara, and Luis Miguel Valenzuela-Montes. 2019. A heuristic approach for exploring uncertainties in transport planning research. Planning Theory & Practice 20: 537–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, Kimberly A. 2016. The Content Analysis Guidebook. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Noordzij, Marlies, Carmine Zoccali, Friedo W. Dekker, and Kitty J. Jager. 2011. Adding up the evidence: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Nephron Clinical Practice 119: 310–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özogul, Sara, and Tuna Tasan-Kok. 2020. One and the same? A systematic literature review of residential property investor types. Journal of Planning Literature 35: 475–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 10: 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelorosso, Raffaele. 2020. Modeling and urban planning: A systematic review of performance-based approaches. Sustainable Cities and Society 52: 101867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, Jennie, Helen Roberts, Amanda Sowden, Mark Petticrew, Lisa Arai, Mark Rodgers, Nicky Britten, Katrina Roen, and Steven Duffy. 2006. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Bailrigg: Lancaster University. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purssell, Edward, and Niall McCrae. 2020. How to Perform a Systematic Literature Review: A Guide for Healthcare Researchers, Practitioners and Students. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, Margarete, Julie Barroso, and Corrine I Voils. 2007. Using qualitative metasummary to synthesize qualitative and quantitative descriptive findings. Research in Nursing & Health 30: 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sandercock, Leonie. 2003. Out of the closet: The importance of stories and storytelling in planning practice. Planning Theory & Practice 4: 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandercock, Leonie, and Giovanni Attili, eds. 2010. Multimedia Explorations in Urban Policy and Planning: Beyond the Flatlands. London and New York: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Niamh, Michail Georgiou, Abby C. King, Zoë Tieges, Stephen Webb, and Sebastien Chastin. 2021. Urban blue spaces and human health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative studies. Cities 119: 103413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoker, ByPhilip, Guang Tian, and Ja Young Kim. 2020. Analysis of variance (ANOVA). In Basic Quantitative Research Methods for Urban Planners. New York: Routledge, pp. 197–219. [Google Scholar]

- Tarachucky, Laryssa, Jamile Sabatini-Marques, Tan Yigitcanlar, Maria José Baldessar, and Surabhi Pancholi. 2021. Mapping hybrid cities through location-based technologies: A systematic review of the literature. Cities 116: 103296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throgmorton, James A. 1996. Planning as Persuasive Storytelling: The Rhetorical Construction of Chicago’s Electric Future (New Practices of Inquiry). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thrun, Michael Christoph. 2018. Projection-Based Clustering through Self-Organization and Swarm Intelligence. Cham and Wiesbaden: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, Roberto, and Alberto Baccini. 2016. Handbook of Bibliometric Indicators: Quantitative Tools for Studying and Evaluating Research. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, Sarah J. 2020. Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck, Nees, and Ludo Waltman. 2010. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 48: 523–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Verweij, Stefan, and Elen-Maarja Trell. 2019. Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) in spatial planning research and related disciplines: A systematic literature review of applications. Journal of Planning Literature 34: 300–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wiles, Rose, Graham Crow, and Helen Pain. 2011. Innovation in qualitative research methods: A narrative review. Qualitative Research 11: 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiao, Yu, and Maria Watson. 2019. Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. Journal of Planning Education and Research 39: 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Ru, Chun-Qing Zhang, and Ryan E. Rhodes. 2021. The pathways linking objectively-measured greenspace exposure and mental health: A systematic review of observational studies. Environmental Research 198: 111233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitcer, Andrew. 2017. Planning as persuaded storytelling: The role of genre in planners’ narratives. Planning Theory and Practice 18: 583–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| “bibliometric”, “content analyses”, “methods”, “research methods”, “qualitative, research techniques” | “ANOVA”, “validity”, “reliability”, “clustering”, “knowledge” | “systematic literature review”, “systematic review” | “urban design”, “urban planning”, “planning”, “design” |

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| “bibliometric”, “content analyses”, “bibliometric approach” | “PRISMA” | “literature review”, “systematic review”, “scoping review”, “meta-analysis”, “systematic meta-analysis” | “quantitative”, “qualitative”, “planning”, “design”, “impact factor” |

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| “bibliometric”, “content analysis”, “literature review”, “systematic review”, “scoping review”, “meta-analysis”, “snowball sampling” | “planning”, “planner”, “urban design”, “urban planning” | “quantitative”, “qualitative”, “comparative analysis”, “impact factor” | “knowledge”, “storytelling”, “narrative”, “synthesis”, |

| Stages | Steps | Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| First. Identifying the gaps in theoretical research |

| Snowball sampling |

| Second. Available resources (Logical query) |

| The green supply chain Using VOSviewer |

| Third. Coding scheme (Inclusion criteria) |

| The methodological filter |

| Fourth. Group formation (Exclusion criteria) |

| Content analysis |

| Fifth. Synthesis of results |

| Narrative review |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elshater, A.; Abusaada, H. Developing Process for Selecting Research Techniques in Urban Planning and Urban Design with a PRISMA-Compliant Review. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100471

Elshater A, Abusaada H. Developing Process for Selecting Research Techniques in Urban Planning and Urban Design with a PRISMA-Compliant Review. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(10):471. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100471

Chicago/Turabian StyleElshater, Abeer, and Hisham Abusaada. 2022. "Developing Process for Selecting Research Techniques in Urban Planning and Urban Design with a PRISMA-Compliant Review" Social Sciences 11, no. 10: 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100471

APA StyleElshater, A., & Abusaada, H. (2022). Developing Process for Selecting Research Techniques in Urban Planning and Urban Design with a PRISMA-Compliant Review. Social Sciences, 11(10), 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100471