Educational Trajectories and Outcomes of Multiracial College Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Multiracial Populations

2.2. Racial Disparities in Higher Education

Trends in College Enrollment and Degree Attainment

2.3. Multiracial People, White Supremacy, and Higher Education

Multiracial Experiences of Higher Education

2.4. Toward a More Complete Understanding of Multiracial Student Pathways and Outcomes under White Supremacy

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Datasets

3.2. Variables and Analyses

4. Results

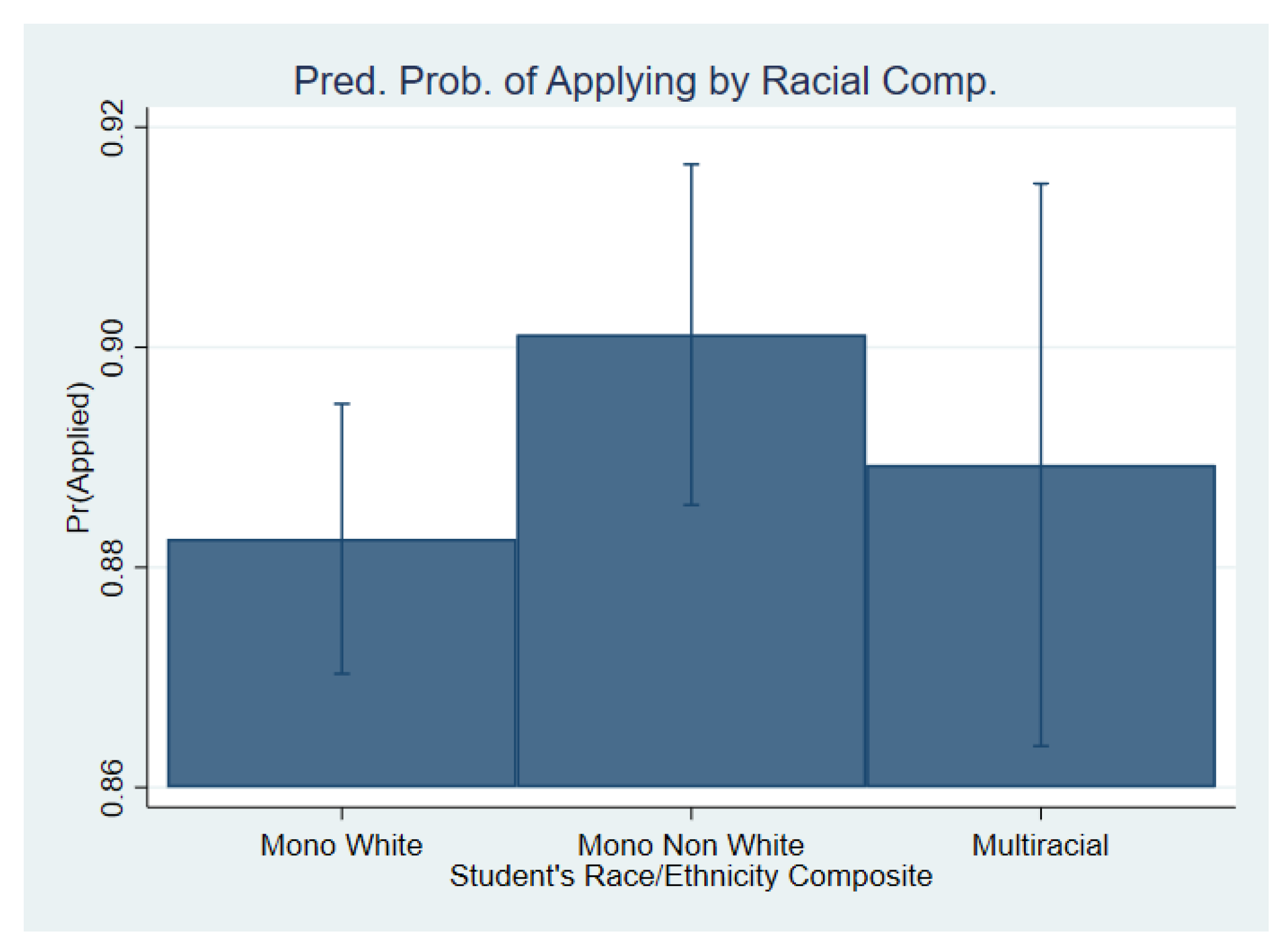

4.1. Logistic Regressions of College Application, Choice, and Enrollment

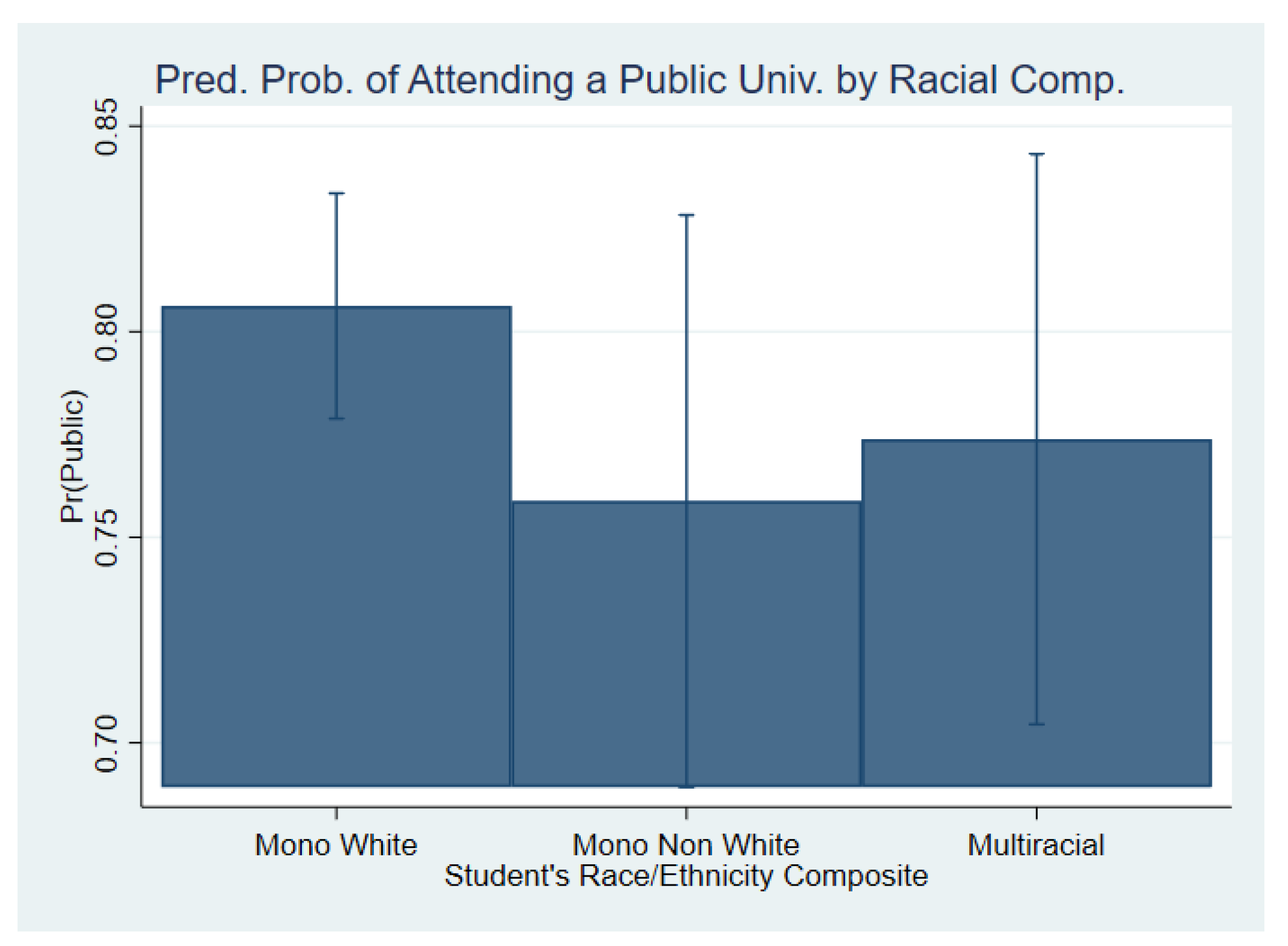

4.2. Logistic Regressions of College Characteristics

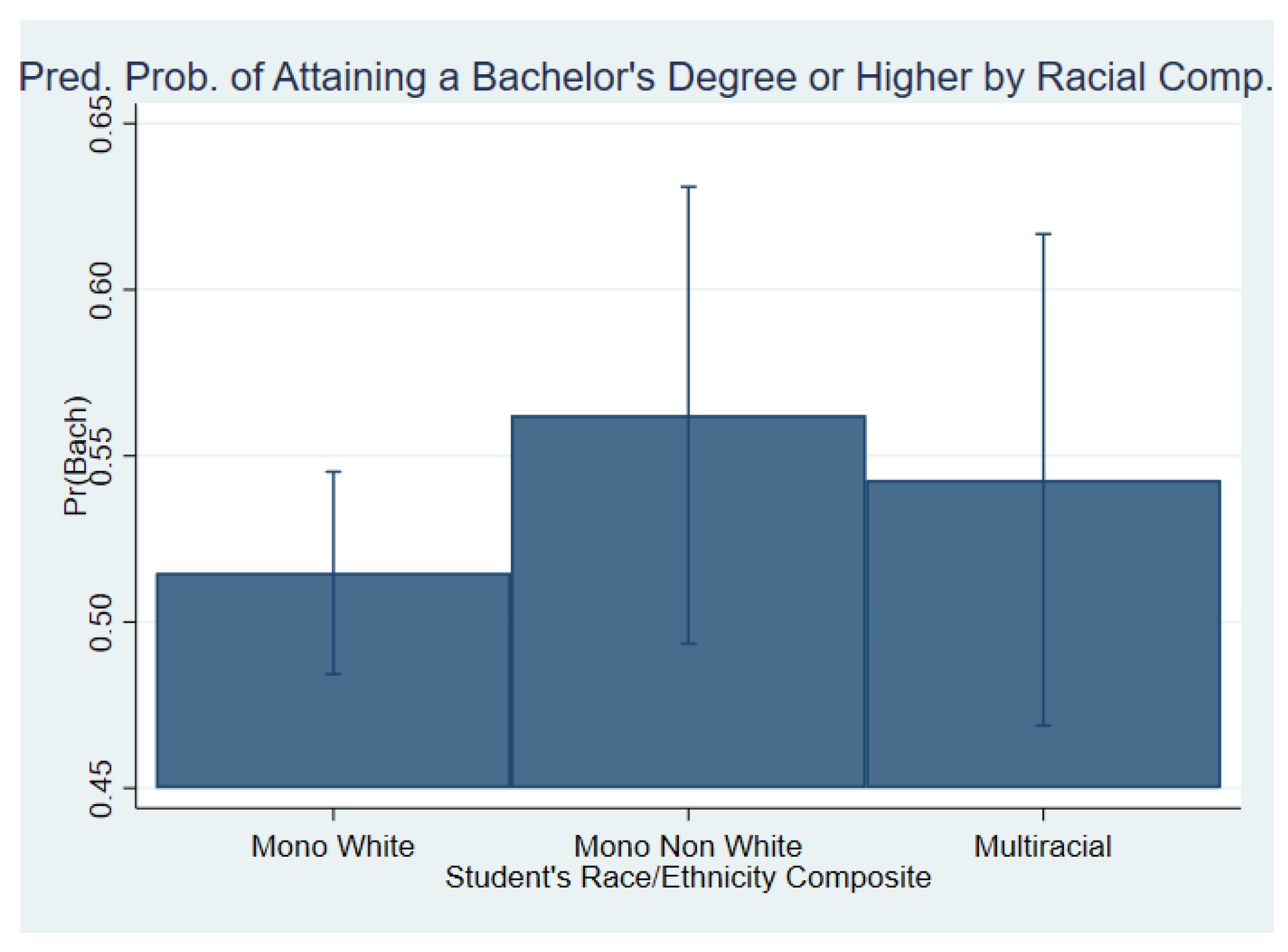

4.3. Multinomial Regression for Degree Attainment

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Limitations and Avenues for Further Study

5.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Application | Enrollment |

|---|---|---|

| Race (monoracial white) | ||

| Mono Non White | 1.213 | 1.329 |

| (0.153) | (0.194) | |

| Multiracial | 1.069 | 0.723 * |

| (0.151) | (0.108) | |

| Female | 1.286 *** | 1.204 ** |

| (0.075) | (0.081) | |

| Income (none) | ||

| $1000 or less | 0.946 | 1.131 |

| (0.378) | (0.511) | |

| $1001–$5000 | 1.482 | 0.806 |

| (0.564) | (0.340) | |

| $5001–$10,000 | 0.993 | 1.103 |

| (0.366) | (0.465) | |

| $10,001–$15,000 | 1.266 | 0.908 |

| (0.450) | (0.365) | |

| $15,001–$20,000 | 1.567 | 1.018 |

| (0.554) | (0.408) | |

| $20,001–$25,000 | 1.490 | 1.057 |

| (0.523) | (0.421) | |

| $25,001–$35,000 | 1.884 | 1.318 |

| (0.650) | (0.517) | |

| $35,001–$50,000 | 2.208 * | 1.483 |

| (0.757) | (0.579) | |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 2.373 * | 2.104 |

| (0.816) | (0.829) | |

| $75,001–$100,000 | 4.020 *** | 3.036 ** |

| (1.419) | (1.234) | |

| $100,001–$200,000 | 4.731 *** | 4.919 *** |

| (1.724) | (2.160) | |

| $200,001 or more | 10.723 *** | 28.613 ** |

| (5.357) | (30.810) | |

| GPA | 3.570 *** | 2.781 *** |

| (0.152) | (0.127) | |

| Mother w/degree | 1.507 *** | 1.842 *** |

| (0.135) | (0.225) | |

| Father w/degree | 1.607 *** | 1.981 *** |

| (0.130) | (0.214) | |

| Parent Race (monoracial white) | ||

| Monoracial Non-White | 1.367 * | 1.274 |

| (0.173) | (0.183) | |

| Multiracial | 1.023 | 1.256 |

| (0.242) | (0.347) | |

| Log Likelihood | −3957.215 | −3182.246 |

| chi2 | 2008.974 | 1331.490 |

| Variable | Public vs. Private | For vs. Not for Profit | Two vs. Four Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race (monoracial white) | |||

| Mono Non White | 0.866 | 0.645 | 0.912 |

| (0.105) | (0.176) | (0.113) | |

| Multiracial | 0.782 | 0.942 | 1.091 |

| (0.107) | (0.278) | (0.158) | |

| Female | 1.059 | 1.075 | 0.797 *** |

| (0.056) | (0.123) | (0.044) | |

| Income (none) | |||

| $1000 or less | 2.137 | 1.325 | 0.612 |

| (1.267) | (1.678) | (0.338) | |

| $1001–$5000 | 1.513 | 2.343 | 0.756 |

| (0.748) | (2.596) | (0.374) | |

| $5001–$10,000 | 1.719 | 1.829 | 0.940 |

| (0.838) | (2.025) | (0.456) | |

| $10,001–$15,000 | 1.462 | 2.627 | 0.839 |

| (0.665) | (2.789) | (0.390) | |

| $15,001–$20,000 | 1.286 | 2.977 | 1.078 |

| (0.578) | (3.146) | (0.498) | |

| $20,001–$25,000 | 1.879 | 2.231 | 0.744 |

| (0.840) | (2.361) | (0.340) | |

| $25,001–$35,000 | 1.508 | 2.720 | 0.926 |

| (0.655) | (2.839) | (0.416) | |

| $35,001–$50,000 | 1.590 | 2.142 | 1.011 |

| (0.686) | (2.233) | (0.452) | |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 1.577 | 1.605 | 1.220 |

| (0.679) | (1.677) | (0.545) | |

| $75,001–$100,000 | 1.467 | 1.816 | 1.567 |

| (0.634) | (1.905) | (0.703) | |

| $100,001–$200,000 | 1.361 | 0.933 | 1.986 |

| (0.590) | (0.997) | (0.897) | |

| $200,001 or more | 0.861 | 1.274 | 3.405 * |

| (0.381) | (1.431) | (1.632) | |

| GPA | 0.735 *** | 0.375 *** | 4.181 *** |

| (0.033) | (0.031) | (0.198) | |

| Mother w/degree | 0.820 ** | 0.728 * | 1.497 *** |

| (0.051) | (0.117) | (0.099) | |

| Father w/degree | 0.781 *** | 0.646 ** | 1.706 *** |

| (0.048) | (0.097) | (0.108) | |

| Parent Race (monoracial white) | |||

| Mono Non White | 1.249 | 1.022 | 1.354 * |

| (0.155) | (0.272) | (0.171) | |

| Multiracial | 0.879 | 1.151 | 0.903 |

| (0.191) | (0.527) | (0.205) | |

| Friend Race (monoracial white) | |||

| Mono Non White | 1.159 | 1.459 * | 0.951 |

| (0.091) | (0.243) | (0.075) | |

| Multiracial | 0.803 | 0.995 | 1.317 |

| (0.137) | (0.412) | (0.253) | |

| Log Likelihood | −4418.622 | −1300.840 | −4236.000 |

| chi2 | 243.137 | 272.124 | 1959.173 |

| Variable | Associates vs. Less Than Associates | Bachelors vs. Less Than Associates | Bachelors vs. Associates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race (monoracial white) | |||

| Mono Non White | 0.804 | 1.244 | 0.838 |

| (0.151) | (0.234) | (0.168) | |

| Multiracial | 0.788 | 1.269 | 1.178 |

| (0.167) | (0.269) | (0.267) | |

| Female | 1.403 *** | 0.713 *** | 1.191 * |

| (0.115) | (0.058) | (0.103) | |

| Income | |||

| None | 0.626 | 1.598 | 0.612 |

| (0.463) | (1.183) | (0.482) | |

| $1000 or less | 1.911 * | 0.523 * | 2.747 * |

| (0.615) | (0.168) | (1.169) | |

| $1001–$5000 | 0.509 | 1.966 | 0.525 |

| (0.204) | (0.789) | (0.227) | |

| $5001–$10,000 | 0.521 | 1.919 | 0.654 |

| (0.186) | (0.686) | (0.254) | |

| $10,001–$15,000 | 0.722 | 1.384 | 1.144 |

| (0.166) | (0.318) | (0.295) | |

| $15,001–$20,000 | 0.757 | 1.322 | 0.871 |

| (0.165) | (0.289) | (0.210) | |

| $20,001–$25,000 | 0.625 * | 1.601 * | 0.750 |

| (0.134) | (0.342) | (0.174) | |

| $25,001–$35,000 | 0.987 | 1.014 | 1.140 |

| (0.141) | (0.145) | (0.178) | |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 1.476 *** | 0.678 *** | 1.083 |

| (0.174) | (0.080) | (0.135) | |

| $75,001–$100,000 | 1.283 | 0.779 | 0.683 ** |

| (0.183) | (0.111) | (0.100) | |

| $100,001–$200,000 | 1.066 | 0.938 | 0.457 *** |

| (0.186) | (0.164) | (0.080) | |

| $200,001 or more | 0.831 | 1.203 | 0.230 *** |

| (0.309) | (0.446) | (0.083) | |

| GPA | 2.060 *** | 0.486 *** | 0.241 *** |

| (0.132) | (0.031) | (0.017) | |

| Mother w/degree | 0.993 | 1.007 | 0.643 *** |

| (0.108) | (0.109) | (0.070) | |

| Father w/degree | 1.069 | 0.936 | 0.542 *** |

| (0.110) | (0.096) | (0.056) | |

| Parent’s Race (monoracial white) | |||

| Mono Non White | 1.120 | 0.893 | 0.885 |

| (0.211) | (0.168) | (0.178) | |

| Multiracial | 0.553 | 1.808 | 0.543 |

| (0.240) | (0.785) | (0.245) | |

| Friend’s Race (monoracial white) | |||

| Mono Non White | 0.932 | 1.073 | 1.036 |

| (0.112) | (0.129) | (0.131) | |

| Multiracial | 0.824 | 1.213 | 0.740 |

| (0.262) | (0.385) | (0.242) | |

| Log Likelihood | −7002.310 | −7002.310 | −7002.310 |

| chi2 | 4903.338 | 4903.338 | 4903.338 |

Appendix B

| Variable | Public vs. Private | Two vs. Four Year |

|---|---|---|

| Race (monoracial white) | ||

| Mono Non White | 0.756 (0.200) | 2.609 *** (0.643) |

| Multiracial | 0.822 (0.189) | 1.315 (0.288) |

| Female | 0.912 (0.085) | 0.710 *** (0.063) |

| Income | 0.997 *** (0.001) | 1.006 *** (0.001) |

| GPA | 0.752 *** (0.056) | 3.631 *** (0.264) |

| Parent w/degree | 0.948 (0.091) | 1.753 *** (0.170) |

| Parent Race (monoracial white) | ||

| Mono Non White | 1.315 (0.340) | 0.628 (0.149) |

| Multiracial | 2.006 (0.854) | 0.419 ** (0.130) |

| Log Likelihood | −1528.822 | −1626.094 |

| chi2 | 43.095 | 564.954 |

| Variable | Bachelors Degree |

|---|---|

| Race (monoracial white) | |

| Mono Non White | 1.211 (0.228) |

| Multiracial | 1.119 (0.191) |

| Female | 0.923 (0.066) |

| Income | 1.011 *** (0.001) |

| GPA | 6.964 *** (0.444) |

| Parent w/degree | 1.931 *** (0.151) |

| Parent Race (monoracial white) | 1.328 (0.245) |

| Mono Non White | 0.702 (0.181) |

| Multiracial | 1.211 (0.228) |

| Log Likelihood | −2509.578 |

| chi2 | 1943.550 |

References

- Adelman, Clifford. 2006. The Toolbox Revisited: Paths to Degree Completion from High School through College; Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

- Allen, Walter. 1992. The Color of Success: African-American College Student Outcomes at Predominantly White and Historically Black Public Colleges and Universities. Harvard Educational Review 62: 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, Sigal, and Marta Tienda. 2005. Assessing the ‘Mismatch’ Hypothesis: Differences inCollege Graduation Rates by Institutional Selectivity. Sociology of Education 78: 294–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, Elizabeth A., and Laura T. Hamilton. 2013. Paying for the Party: How College Maintains Inequality. Harvard: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, William G., Derek Bok, and Glenn C. Loury. 2016. The Shape of the River: Long-Term Consequences of Considering Race in College and University Admissions. Princeton: Princeton University Press, Available online: Muse.jhu.edu/book/45834 (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Bratter, Jenifer L. 2018. Multiracial Identification and Racial Gaps: A Work in Progress. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 677: 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratter, Jenifer L., and Bridget K. Gorman. 2011. Does Multiracial Matter? A Study of Racial Disparities in Self-Rated Health. Demography 48: 127–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratter, Jenifer L., and Rachel Tolbert Kimbro. 2013. Multiracial Children and Poverty: Evidence From the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study of Kindergartners. Family Relations 62: 175–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratter, Jenifer L., and Sarah Damaske. 2013. Poverty at a racial crossroads: Poverty among multiracial children of single mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family 75: 486–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsma, David L. 2005. Interracial Families and the Racial Identification of Mixed-Race Children: Evidence from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study. Social Forces 84: 1131–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Mary E., Jenifer L. Bratter, and Wendy D. Roth. 2016. Measuring the Diverging Components of Race: An Introduction. American Behavioral Scientist 60: 381–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campion, Karis. 2019. ‘You Think You’re Black?’ Exploring Black Mixed-Race Experiences of Black Rejection. Ethnic and Racial Studies 42: 196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carnevale, Anthony P., and Jeff Strohl. 2010. How Increasing College Access is Increasing Inequality, and what to do About it. In Rewarding Strivers. New York: The Century Foundation Press. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Kate H., and Nancy E. Reichman. 2019. The health of biracial children in two-parent families in the United States. Demographic Research 41: 197–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, Kate H., and Rachel E. Goldberg. 2021. Multiracial Children’s Experiences of Family Instability. Journal of Marriage and Family 83: 627–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, Kristen A. 2020. Biracial Identity Development at Historically White and Historically Black Colleges and Universities. Sociology of Education 93: 238–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelo, Linda, and Ray Franke. 2016. Social Mobility and Reproduction for Whom? College Readiness and First-Year Retention. American Educational Research Journal 53: 1588–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Sycarah, Jennifer L. Reynolds, Wei Wen Hsu, Jessica Barnes, and Kenneth Tyler. 2014. Examining Multiracial Youth in Context: Ethnic Identity Development and Mental Health Outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 43: 1688–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gasser, Heather S. 2002. Portraits of Individuality: A Qualitative Study of Multiracial College Students. Journal of Student Affairs 11: 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Goldrick-Rab, Sara. 2006. Following Their Every Move: An Investigation of Social-Class Differences in College Pathways. Sociology of Education 79: 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullickson, Aaron. 2016. Essential Measures: Ancestry, Race, and Social Difference. American Behavioral Scientist 60: 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullickson, Aaron, and Ann Morning. 2011. Choosing Race: Multiracial Ancestry and Identification. Social Science Research 40: 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Jessica C. 2017. Multiracial College Students’ Experiences with Multiracial Microaggressions. Race, Ethnicity, and Education 20: 429–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harris, Kathleen Mullan, Carolyn Tucker Halpern, Eric A. Whitsel, Jon M. Hussey, Ley A. Killeya-Jones, Joyce Tabor, and Sarah C. Dean. 2019. Cohort Profile: The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). International Journal of Epidemiology 48: 1415–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, Charles, Richard Alba, and Reynolds Farley. 2000. The Meaning and Measurement Of Race in the U.S. Census: Glimpses into the Future. Demography 37: 381–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hout, Michael. 2012. Social and Economic Returns to College Education in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology 38: 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ishitani, Terry T. 2006. Studying Attrition and Degree Completion Behavior Among First-Generation College Students in the United States. The Journal of Higher Education 77: 861–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, Anthony A. 2019. The Privileged Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Anthony. 2019. ‘I can turn it on when I need to’: Pre-college Integration, Culture, and Peer Academic Engagement among Black and Latino/a Engineering Students. Sociology of Education 92: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Lee, Jeanett Castellanos, and Darnell Cole. 2002. Examining the Ethnic Minority Student Experience at Predominantly White Institutions: A Case Study. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 1: 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Shamus. 2010. Privilege: The Making of an Adolescent Elite at St. Paul’s School. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau, Annette. 2015. Cultural Knowledge and Social Inequality. American Sociological Review 80: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leonhardt, David. 2005. The College Dropout Boom. The New York Times, May 24. [Google Scholar]

- Mettler, Suzanne. 2014. Degrees of Inequality: How the Politics of Higher Education Sabotaged the American Dream. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Museus, Samuel D., Susan A. Lambe Sariñana, April L. Yee, and Thomas E. Robinson. 2016. A Qualitative Analysis of Multiracial Students’ Experiences with Prejudice and Discrimination in College. Journal of College Student Development 57: 680–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, Casey, and Marc Johnston. 2008. The space in between: Issues for multiracial student organization and advising. New Directions for Student Services 2008: 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Zhenchao, Sampson Lee Blair, and Stacey D. Ruf. 2001. Asian American Interracial and Interethnic Marriages: Differences by Education and Nativity. International Migration Review 35: 557–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, Kristen A. 2000. Patterns of situational identity among biracial and multiracial college students. Review of Higher Education 23: 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, Lauren A. 2012. Diversity within Reach: Recruitment versus Hiring in Elite Firms. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 639: 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, James E., Regina Deil-Amen, and Ann E. Person. 2006. After Admission: From College Access to College Success. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Morest, Vanessa. 2013. From Access to Opportunity: The Evolving Social Roles of Communiy Colleges. The American Sociologist 44: 319–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuber, Jenny M. 2015. Pulled in or Pushed Out? How Organizational Factors Shape the Social and Extra-Curricular Experiences of First-Generation Students. In College Students’ Experiences of Power and Marginality: Sharing Spaces and Negotiating Differences. Edited by Elizabeth M. Lee and Chaise LaDousa. New York: Routledge, pp. 118–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tabb, Karen M., Christopher R. Larrison, Shinwoo Choi, and Hsiang Huang. 2016. Disparities in Health Services Use Among Multiracial American Young Adults. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 18: 1462–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Commerce, Census Bureau, Current Population Survey (CPS), October Supplement, 2010 through 2019. 2020, See Digest of Education Statistics 2020, Table 302.20. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d20/tables/dt20_302.20.asp (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), Winter 2016–17, Graduation Rates Component. 2017, See Digest of Education Statistics 2017, Table 326.10. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d20/tables/dt20_326.10.asp (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), Spring 2001, Spring 2011, and Spring 2019, Fall Enrollment Component. 2019, See Digest of Education Statistics 2019, Table 306.10. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_306.10.asp (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Wilbur, Tabitha G., and Vincent J. Roscigno. 2016. First-Generation Disadvantage and College Enrollment/Completion. Socius 2: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoo, Hyung Chol, Kelly F. Jackson, Rudy P. Guevarra, Matthew J. Miller, and Blair Harrington. 2016. Construction and Initial Validation of the Multiracial Experiences Measure (MEM). Journal of Counseling Psychology 63: 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variables | ELS | Add Health |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (S.D.) or % | Mean (S.D.) or % | |

| Respondent’s Race | ||

| Monoracial White | 56.95 | 62.93 |

| Monoracial Non-White | 38.22 | 31.60 |

| Multiracial | 4.82 | 5.46 |

| Female | 50.21 | 50.52 |

| GPA | 2.70 (0.78) | 2.56 (0.84) |

| Parent’s Race | ||

| Monoracial White | 62.63 | 64.47 |

| Monoracial Non-White | 35.90 | 33.02 |

| Multiracial | 1.47 | 2.52 |

| Mother w/College Degree | 27.37 | N/A |

| Father w/College Degree | 31.92 | N/A |

| Parent w/College Degree | N/A | 22.98 |

| n | 13,285 | 9752 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mitchell, S.; Warren, E. Educational Trajectories and Outcomes of Multiracial College Students. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11030101

Mitchell S, Warren E. Educational Trajectories and Outcomes of Multiracial College Students. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(3):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11030101

Chicago/Turabian StyleMitchell, Sam, and Evangeline Warren. 2022. "Educational Trajectories and Outcomes of Multiracial College Students" Social Sciences 11, no. 3: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11030101

APA StyleMitchell, S., & Warren, E. (2022). Educational Trajectories and Outcomes of Multiracial College Students. Social Sciences, 11(3), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11030101