The Contribution of Parental Factors to Adolescents’ Deviant Behaviour in South Africa: Evidence from Three Rural Communities in South Africa

Abstract

:1. Introduction

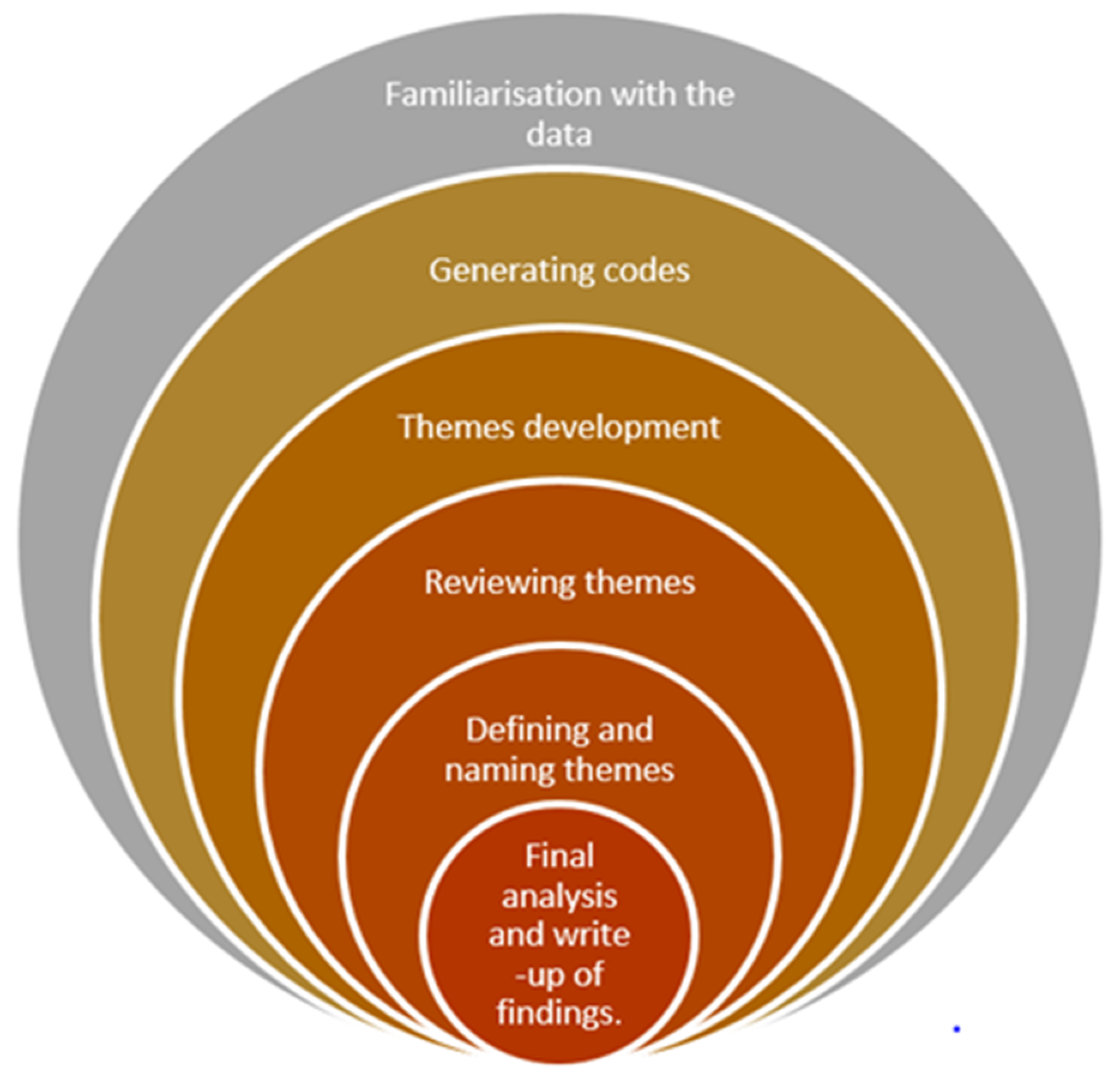

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Less Parental Supervision

Because that’s when the parents get their pay or whatever, their grants… and then from what I have seen is they will end up drinking and then the children (adolescents) don’t have supervision and the fights or stabbings and those kinds of things you usually see around about the end of the month.(Stakeholder 1)

… our children that are younger are involved in crime due to a lack of parent supervision…(Stakeholder 14)

… 12 years. I’ve never seen it myself but from working at the clinic and things like that, people talk so yes, because also usually at the end of the month there is less parental supervision and incidents involving children, has just increased…(Stakeholder 1)

3.2. Lack of Parental Support and Knowledge of Adolescents’ Behaviour

In our community, our people lack a sense of responsibility. Children leave school, they don’t finish matric… and the parents don’t feel like taking responsibility for them because many times the child would say they don’t feel like going to school then the parent would say now what am I supposed to do? The mother does not feel like taking the child every day to school, she prefers to sit in the sun so it basically comes back to the lack of support and responsibility, our people do not have that, so the parents rather allow the children to leave school.(Stakeholder 5)

Like drug abuse, lacking parent skills, they don’t know how to raise the children properly. The parents don’t have parenting skills because they use drugs and alcohol.(Stakeholder 6)

3.3. Absenteeism

Fathers are not involved, they just gave up. Mothers when they are on drugs, the grandparents are there. They are responsible to raise the kids. I mean when you’re almost 60 years of age, you don’t want to sit up with a child screaming, shouting and kicking because it’s not your time to raise a kid.(Stakeholder 8)

Our children just drop out of school and just stand in front of the shops loafing for R5 or whatever, some get involved in crime at that age. And our parents are absent like in, I’m here in the flesh but I’m absent. They are busy with their own stuff so the children are on their own actually and you are not aware of what is going on in the child’s life even. The drug problem is so huge in Lamberts Bay.(Stakeholder 14)

3.4. Lack of Parental Discipline

Parents are the biggest problems nowadays, they do not commit to discipline, they do not commit to any routine.(Stakeholder 4)

I won’t say all of them but there are some of the parents that don’t really worry when the child who is 12 or 13 years goes out of the house and comes in at any time of the night. Then they want to fight with the children, but then the children are already grown because, at 12 or 13 years they are already grown so then they want to discipline the children, which is too late because you must discipline the child from an early age.(Stakeholder 11)

3.5. Parents’ Lack of Concern and Knowledge of the Child’s Behaviour

… then you tell the parents that the child misbehaving in class, that parent will go to school, and the school manager and the school secretary, all the teachers are wrong, that child is never wrong.(Stakeholder 4)

Yes and then currently it’s our drug use, yes tik is taking over our community and children just don’t listen…, parents refuse to believe, they see some differences in the child and that their behaviour has changed but they are ignorant they just don’t want to ask or know if something is wrong.(Stakeholder 5)

We have a big problem with children that do not attend school… we have very few parents that do something about the case….our parents just don’t care...the parents don’t worry about their children. As I said, the child can do it if he or she wants to.(Stakeholder 6)

3.6. The Inability of Parents to Be Positive Role Models

…they don’t know about doing sports and stuff like what youngsters are supposed to do, so they drink from an early age so now they are continuing the cycle of the parents drinking and abusing the mother or the girlfriend or stuff like that. So the parents drink in front of their children, they drink and they do drugs and they fight with the children you see? Those are their role models, so they have negative role models in the community who they look up to and think this is the way you must be and you must act.(Male stakeholder, 32 years old, Lamberts Bay)

4. Discussion

5. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adler, Patricia, and Peter Adler. 2015. Constructions of Deviance: Social Power, Context, and Interaction. Belmont: Wadsworth, Vol. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Aute, Dorothy Anyango. 2019. Secure Parental Attachment and Deviant Behaviour among Secondary School Students in Homabay County-Kenya. Science Journal of Education 7: 127–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, Diana. 1978. Parental disciplinary patterns and social competence in children. Youth and Society 9: 239–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolu-Steve, Foluke N., and Mary O. Esere. 2017. Strategies for managing deviant behaviour among in-school adolescents as expressed by secondary school counsellors in Kwara State, Nigeria. Inkanyiso: Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 9: 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, Jeoffrey. L. 2015. National Institute on Drug Abuse, Brains and Behaviour. Available online: http://www.livestrong.com/disease_and_conditions (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1994. Ecological models of human development. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 2nd ed. Edited by Torsten Husen and T. Neville Postlethwaite. Oxford: Pergamon Press, vol. 3, pp. 1643–47. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, Nicole W. T. 2014. Low self-control and co-occurrence of gambling with substance use and delinquency among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Gambling Studies 30: 105–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chui, Wing Hong, and Heng Choon. Oliver Chan. 2013. Association between self-control and school bullying behaviours among Macanese adolescents. Child Abuse and Neglect 37: 237–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Criss, Michael M., Tammy K. Lee, Amanda Sheffield Morris, Lixian Cui, Cara D. Bosler, Karina M. Shreffler, and Jennifer S. Silk. 2015. Link between monitoring behaviour and adolescent adjustment: An analysis of direct and indirect effects. Journal of Child and Family Studies 24: 668–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crnic, Keith, and Emily Ross. 2017. Parenting stress and parental efficacy. In Parental Stress and Early Child Development. New York and Cham: Springer, pp. 263–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dada, Siphokaz. 2017. Own Analysis of the 2016 SACENDU Data on the Total Number of Patients Admitted for the Period January to December 2016: July–December 2016 (Research Brief). Cape Town: Medical Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, David L. 1985. The over-negativized conceptualization of deviance: A programmatic exploration. Deviant Behaviour 6: 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwairy, Marwan, and Mustafa Achoui. 2010. 2010 Parental control: A second cross-cultural research on parenting and psychological adjustment of children. Journal of Child and Family Studies 19: 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esere, Mary Ogechi. 2008. Effect of Sex Education Programme on at-risk sexual behaviour of school-going adolescents in Ilorin, Nigeria. African Health Sciences 8: 120–25. Available online: http://www.bioline.org.br/abstract?id=hs08026andlang=en (accessed on 4 June 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzese, Robert. J. 2015. The Sociology of Deviance. Springfield: Charles C Thomas Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Gault-Sherman, Martha. 2012. It’s a two-way street: The bidirectional relationship between parenting and delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 41: 121–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goode, Erich. 2007. Deviant Behaviour. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Goode, Erich. 2015. The sociology of deviance. In The Handbook of Deviance. West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Groenewald, Candince, Sinakekelwe Khumalo, and Zaynab Essack. 2018. Speaking through pictures: Canvassing adolescent risk behaviours in a semi-rural community in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. South African Journal of Child Health 1: s57–s62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwatimba, Leah, and Nanga Raymond Raselekoane. 2018. An evaluation of the effectiveness of diversion programmes in the rehabilitation of the youth and the promotion of juvenile justice in South Africa. Gender and Behaviour 16: 11168–81. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Charlene, Jullia. Melissa Scarpate, and Alexander T. Vazsonyi. 2020. Parental and kinship ties, and low self-control: Violence perpetration among rural African American adolescents from the Black Belt. Journal of Adolescence 85: 115–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herington, Matthew J., and Elske van de Fliert. 2018. Positive deviance in theory and practice: A conceptual review. Deviant Behaviour 39: 664–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, Travis. 1969. The Causes of Delinquency. Berkeley: The University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Idris, Olayinka. 2016. Causes of Deviant Behaviour among In-School Adolescents in Lagos. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Department of Educational Foundation, Lagos State University, Lagos, Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Garry. 2011. Deviance and social control. In Routledge Handbook of Deviant Behaviour. London: Routledge, pp. 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kempf-Leonard, Kimberly. 2019. The Status of Hirschi’s Social Control Theory after 50 Years. In Fifty Years of Causes of Delinquency, Volume 25: The Criminology of Travis Hirschi. London: Routledge, p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- Keogh-Clark, Francesca, Reid C. Whaley, Adam M. Leventhal, and Evan A. Krueger. 2021. Sex differences in the association between parental monitoring and substance use initiation among adolescents. Addictive Behaviours 122: 107024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kincaid, Carlye, Deborah J. Jones, Jessica Cuellar, and Michelle Gonzalez. 2011. Psychological control associated with youth adjustment and risky behaviour in African American single mother families. Journal of Child and Family Studies 20: 102–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntsche, Sandra, and Emmanuel Kuntsche. 2016. Parent-based interventions for preventing or reducing adolescent substance use—A systematic literature review. Clinical Psychology Review 45: 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lac, Andrew, and William D. Crano. 2009. Monitoring matters: Meta-analytic review reveals the reliable linkage of parental monitoring with adolescent marijuana use. Perspectives on Psychological Science 4: 578–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lac, Andrew, Jennifer B. Unger, Tatiana Basáñez, Anamara Ritt-Olson, Daniel W. Soto, and Lourdes Baezconde-Garbanati. 2011. Marijuana use among Latino adolescents: Gender differences in protective familial factors. Substance Use and Misuse 46: 644–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lam, Chun Bun, Susan M. McHale, and Ann C. Crouter. 2014. Time with peers from middle childhood to late adolescence: Developmental course and adjustment correlates. Child Development 85: 1677–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lau, Wilfred Wing-Fat, and Allan H. K. Yuen. 2013. Adolescents’ risky online behaviours: The influence of gender, religion, and parenting style. Computers in Human Behaviour 29: 2690–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, Sri. 2016. Psikologi Keluarga: Penanaman Nilai dan Penanaman Konflik dalam Keluarga. Kencana: Prenada Media. [Google Scholar]

- Lestiawati, I. Made. 2013. Pengaruh pola asuh orang tua terhadap kemampuan sosial anak usia 6–7 tahun. Jurnal Ilmiah Visi 8: 111–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Light, John M., Charlotte C. Greenan, Julie C. Rusby, Kimberley M. Nies, and Tom A. B. Snijders. 2013. Onset to first alcohol use in early adolescence: A network diffusion model. Journal of Research on Adolescence 23: 487–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louw, Dap, and Anet Elizabeth Louw. 2007. Child and Adolescent Development. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State. [Google Scholar]

- Loveline, Yaro, and Nformi Doris Jaja. 2020. Domestic Violence and the Development of Anti-Social Behaviours among Adolescent Students in the South West Region of Cameroon. Noble International Journal of Social Sciences Research 5: 114–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Yi-Fen, Yi-Chun Yu, Ling Ren, and Ineke Haen Marshall. 2013. Exploring the utility of self-control theory for risky behaviour and minor delinquency among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 29: 32–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machmud, Hadi. 2013. Pengaruh pola asuh dalam membentuk keterampilan sosial anak. Al-MUNZIR 6: 130–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, Christina, Sharon Lipperman-Kreda, Paul J. Gruenewald, Melina Bersamin, and Joel W. Grube. 2015. Adolescent drinking risks associated with specific drinking contexts. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 39: 1705–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marceau, Kristine, Nayantara Nair, Michelle L. Rogers, and Kristina M. Jackson. 2020. Lability in parent-and child-based sources of parental monitoring is differentially associated with adolescent substance use. Prevention Science 21: 568–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, Shanaaz, Naeemah Abrahams, Lorna J. Martin, Carl Lombard, and Rachel Jewkes. 2019. Homicide pattern among adolescents: A national epidemiological study of child homicide in South Africa. PLoS ONE 14: e0221415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchiri, Beatrice Wamuyu, and Monika M. L. Dos Santos. 2018. Family management risk and protective factors for adolescent substance use in South Africa. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy 13: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neiderhiser, Jenae M., Kristine Marceau, and David Reiss. 2013. Four factors for the initiation of substance use by young adulthood: A 10-year follow-up twin and sibling study of marital conflict, monitoring, siblings, and peers. Development and Psychopathology 25: 133–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odumuyiwa, E. Ade. 2001. A ’Religious’ but Criminal Society: Any Remedy? Ago Iwoye: Olabisi Onabanjo University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oni, Adesoji A. 2010. Peer group pressure as a determinant of adolescent social adjustment in nigerian schools. Journal of Educators and Education/Jurnal Pendidik dan Pendidikan 25: 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Parks, Alisha B. 2013. The Effects of Family Structure on Juvenile Delinquency. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Available online: http://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2279 (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Pyrooz, David. C., and Scott. H. Decker. 2012. Delinquent behaviour, violence and gang behaviour in China. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 292: 251–72. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, S. P., Shamagonam James, Ronel Sewpaul, Sibusiso Sifunda, Afzal Ellahebokus, Nilen S. Kambaran, and Riyadh G. 2011. Omardien. In Umthente Uhlaba Usamila: The 3rd South African National Youth Risk Behaviour Survey 2011. Cape Town: South African Medical Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- Robbiyah, Robbiyah, Diyan Ekasari, and Ramdhan Witarsa. 2018. Pengaruh Pola Asuh Ibu terhadap Kecerdasan Sosial Anak Usia Dini di TK Kenanga Kabupaten Bandung Barat. Jurnal Obsesi: Jurnal Pendidikan Anak Usia Dini 2: 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roubinov, Danielle S., and William Thomas Boyce. 2017. Parenting and SES: Relative values or enduring principles? Current Opinion in Psychology 15: 162–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubington, Earl, and Martin Weinberg. 2011. Deviance: The Interactionist Perspective. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rusby, Julie C., John M. Light, Ryann Crowley, and Erika Westling. 2018. Influence of parent–youth relationship, parental monitoring, and parent substance use on adolescent substance use onset. Journal of Family Psychology 32: 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, Allison M. 2000. Peer groups as a context for the socialisation of adolescents’ motivation, engagement, and achievement in school. Educational Psychologist 35: 101–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, Matthew R., and Karen M. T. Turner. 2018. The importance of parenting in influencing the lives of children. In Handbook of Parenting and Child Development across the Lifespan. Cham: Springer, pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Schreck, Christopher J., Eric A. Stewart, and Bonnie S. Fisher. 2006. Self-control, victimization, and their influence on risky lifestyles: A longitudinal analysis using panel data. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 22: 319–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stats SA. 2012. Statistical Release (Revised). Census 2011. Pretoria: Stats SA. [Google Scholar]

- Stats SA. 2019. Statistical Release: Mid-Year Population Estimates 2019. Pretoria: Stats SA. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Andrea L., Linda G. Becker, Alice M. Huber, and Richard F. Catalano. 2012. Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addictive Behaviours 37: 747–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suharsono, Joko Tri, Aris Fitriyani, and Arif Setyo Upoyo. 2009. Hubungan pola asuh orang tua terhadap kemampuan sosialisasi pada anak prasekolah di TK Pertiwi Purwokerto Utara. Jurnal Keperawatan Soedirman 4: 112–18. [Google Scholar]

- Suleiman, Jamiu. Mahmood. 2011. Causes and Remedies of Deviant Behaviour among Adolescents as Expressed by Teachers in Kwara State. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Department of Counsellor Education, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- Tharp, Andra Teten, and Rita K. Noonan. 2012. Associations between three characteristics of parent–youth relationships, youth substance use, and dating attitudes. Health Promotion Practice 13: 515–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. 2019. Adolescents Overview. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/adolescents/overview/ (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Wang, Ming-Te, Noona Kiuru, Jessica L. Degol, and Katariina Salmela-Aro. 2018. Friends, academic achievement, and school engagement during adolescence: A social network approach to peer influence and selection effects. Learning and Instruction 58: 148–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, Ashby Thomas, and Alison M. Yaeger. 2003. Family factors and adolescent substance use: Models and mechanisms. Current Directions in Psychological Science 12: 222–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolhuter, Charl. C., and Johannes. L. Van der Walt. 2020. Indiscipline in South African schools: The parental/community perspective. Koers: Bulletin for Christian Scholarship = Koers: Bulletin vir Christelike Wetenskap 85: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Participants (N = 23) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 8 | 34.8 |

| Female | 15 | 65.2 |

| Age | ||

| 20–29 | 4 | 17.4 |

| 30–39 | 10 | 43.5 |

| 40–49 | 4 | 17.4 |

| 50–59 | 4 | 17.4 |

| 60–69 | 1 | 4.3 |

| Education | ||

| High school | 2 | 8.7 |

| Completed matric | 11 | 47.8 |

| Diploma | 3 | 13 |

| Degree | 5 | 21.7 |

| Postgraduate | 2 | 8.7 |

| Profession | ||

| Health worker | 4 | 17.4 |

| Child and youth worker | 4 | 17.4 |

| Social worker | 7 | 30.4 |

| Police officer | 1 | 4.3 |

| General manager | 1 | 4.3 |

| Cleaner | 6 | 26.1 |

| Language | ||

| English | 2 | 8.7 |

| IsiXhosa | 17 | 73.9 |

| Afrikaans | 4 | 17.4 |

| Questions |

|---|

| 1. What are the most prominent challenges faced in this community? 2. What factors contribute to the challenges you have noted? 3. Describe the state of adolescents living in this community? 4. What kind of behaviours are adolescents in this community involved in? 5. What are the factors influencing adolescents’ behaviours? 6. What can be done to improve the well-being of adolescents in this community? |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rachel, C.; Roman, N.V.; Donga, G.T. The Contribution of Parental Factors to Adolescents’ Deviant Behaviour in South Africa: Evidence from Three Rural Communities in South Africa. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11040152

Rachel C, Roman NV, Donga GT. The Contribution of Parental Factors to Adolescents’ Deviant Behaviour in South Africa: Evidence from Three Rural Communities in South Africa. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(4):152. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11040152

Chicago/Turabian StyleRachel, Chinyakata, Nicolette Vanessa Roman, and Gift T. Donga. 2022. "The Contribution of Parental Factors to Adolescents’ Deviant Behaviour in South Africa: Evidence from Three Rural Communities in South Africa" Social Sciences 11, no. 4: 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11040152

APA StyleRachel, C., Roman, N. V., & Donga, G. T. (2022). The Contribution of Parental Factors to Adolescents’ Deviant Behaviour in South Africa: Evidence from Three Rural Communities in South Africa. Social Sciences, 11(4), 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11040152