1. Introduction

One of the main challenges faced by the society of the twenty-first century is global warming, as expressed in the Sixth Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (

IPCC 2022). This report highlights the importance of adapting to this phenomenon due to its effects, such as the increase in temperature, the loss of climate comfort or the intensification and greater frequency of extreme weather phenomena (floods and droughts). Therefore, raising awareness and rigorously teaching about climate change is in everyone’s interest, but is of particular concern for the educational environment (

Jeong et al. 2021;

Masters 2020;

Nelles and Serrer 2020;

Verlie and Blom 2021), as, in part, the future of society depends on increasing our knowledge about this serious problem (

Borhaug 2021;

Ferrari et al. 2019;

Kurup et al. 2021;

Morote and Olcina 2021a). The latter authors consider that the challenge of addressing global warming and climate change in education (Social Sciences) should be focused on by including informed decision making in classroom practices.

Regarding the research problem addressed here (teaching and climate change), for decades, different authors (

Benejam 1997;

Fien 1992) have described the urgent need to discuss world problems in schools (including climate change issues) through the Didactics of Social Sciences, in its different scales. Furthermore, the content of climate change is among of the most controversial that must be explained in social science classes (

Ho and Seow 2015;

Morote et al. 2021b). Thus,

Benejam (

1997) explains that “training our students as citizens of a democratic and alternative system” (p. 47) is necessary, among other purposes, “to preserve and value the natural and cultural heritage that we have received as legacy” (p. 48). As many authors affirm, this is based on the inclusion of Relevant Social Problems (RSP) in social science classrooms, a methodology that comes from the Anglo-Saxon sphere (

Fien 1992;

Evans et al. 1996). Although in Francophone literature, as

López and Oller (

2019) explain, the same approach is described, it is called Socially Alive Issues (SAI) (

Legardez 2006;

Legardez and Simonneaux 2006;

Tutiaux-Guillón 2011). In Spain, this approach has also been incorporated from different research (

Benejam 1997;

García and Porlán 2000;

García and De Alba 2003;

Pagès and Santisteban 2011;

Pagès 2007;

López 2011;

Canals and González 2011;

Santisteban et al. 2014;

Díaz and Felices 2017).

With respect to the interest in teaching about climate change, some authors (

Morote and Olcina 2020,

2021a;

Rausell et al. 2021) have pointed out that education is one of the most important non-structural factors for adapting to and addressing this phenomenon. However, these researchers also indicate that it is one of the variables that is least frequently taken into account, with priority given to structural and political mitigation measures. The importance of climate change has also been indicated by different international bodies. In its Fifth Report (

IPCC 2014), the IPCC pointed out that education was one of the main actions necessary for adapting societies to this phenomenon. In addition, the United Nations (

UN 2015) identifies this variable “education” as one of the most important elements in mitigating the effects of climate change (Sustainable Development Goal nº13 “Climate action”). Similarly, the European Environmental Agency (

EEA 2017) indicated the importance of the vulnerability factor, highlighting education as a way to mitigate the effects of global warming. This issue has also been a point of interest with respect to educational laws, on both an international and a national (Spain) level (

Morote and Olcina 2021b). Hence, in Spain (the present study case), the Climate Change Act was published (May 2021), which, for the first time, included a section on teaching: Title VIII (“Education, Research and Innovation in the fight against climate change and energy transition”).

Initially, the issue of environmental and climate change constituted a controversial topic from a scientific point of view, as the extent to which human action altered the natural conditions of climate evolution was questioned (

Ho and Seow 2015). Currently, the majority of researchers back these facts with evidence (

Roussel and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles 2020) and it has now become a conceptual topic taught in the subjects of Geography and Social Sciences (

Morote and Olcina 2020,

2021a). In Spain, explanations for climate change carry more weight in the educational setting due to the requirement to address these topics in classrooms, as established both for Primary Education (Royal Decree 126/2014, 28 February; Social Sciences subject) and Secondary Education and the Baccalaureate (Royal Decree 1105/2014, 26 December; Geography subject).

Another issue to consider with respect to the teaching of climate change is the influence that the media has on both teachers’ and students’ understanding of the issue (

Morote et al. 2021a;

Wu and Otsuka 2021). One of the consequences of this is the dissemination of fake news and stereotypes that have arisen in the social representation of the youngest cohorts (

Ferrari et al. 2019). In fact,

Morote et al. (

2021a) have analysed how the information that the majority of trainee teachers receive is drawn from the Internet, television and social networks.

Kažys (

2018),

Brisman (

2018) and

Lutzke et al. (

2021) explain the danger that this could have in the case of information that is unreliable or lacks rigour, or when the news is false or manipulated. This fact (false information lacking in rigour) has even been transferred to the contents in Social Science textbooks, as confirmed by

Morote and Olcina (

2020), where there is: (1) a predominance of information with scientific errors; and (2) an excessive influence of the media and a catastrophic view of climate change. In the case of these resources (school textbooks), this problem is even more serious since, currently, in Social Sciences classes, they continue to be the main resource used (

Bel et al. 2019). This is also reflected in the social attitudes of future teachers with respect to this phenomenon, in which human action is viewed as the main cause and natural disasters its main effects (

Morote 2020). As this author explains, it is true that the majority of trainee teachers have received training on this subject matter, but only 13.4% of this training is based on academic studies. Therefore, as indicated by

Morote et al. (

2021a), the information received is similar to that presented by the media (86.2%) and constitutes a superfluous approach to the phenomenon, which fosters the creation of stereotypes.

In Spain, there is a consolidated line of study related to the teaching of climate change in the educational sphere (

Caride and Meira 2019;

Escoz-Roldan et al. 2020) and also in the field of the natural sciences (

Calixto 2015;

Domènech 2014). However, the same cannot be said for Social Science and/or Geography. It is true that these sciences have produced extensive literature on the teaching of climatology (

Martínez-Fernández and Olcina 2019;

Morote and Moltó 2017;

Sebastiá and Tonda 2018), but not on climate change, except for some recent publications. In this respect, over the last few years, recent studies have been carried out on the teaching of this phenomenon from three perspectives: (1) the social attitudes of trainee teachers (

Morote and Hernández 2020;

Morote and Moreno 2021;

Morote et al. 2021a); (2) the analysis of the contents of school textbooks (

Morote and Olcina 2020,

2021a); and (3) didactic proposals (

Morote and Olcina 2021b). In fact, the former president of the Spanish Association of Geography expressed the need for a greater dedication and interest in this subject matter similar to that of other scientific fields and on the international scene (

Olcina 2017). On an international level, many works have been published on the teaching of climate change, such as those in Central and North America (

McWhirter and Shealy 2018;

Li et al. 2021;

Sezen-Barrie and Marbach-Ad 2021), South America (

Da Rocha et al. 2020), Europe (

Jeong et al. 2021;

Kovacs et al. 2017;

Kurup et al. 2021), Africa (

Anyanwu and Le Grange 2017) and Asia and Oceania (

Ahmad and Numan 2015;

Li and Liu 2021;

Verlie and Blom 2021).

The objectives of this research are to analyse the following, using a case study of Primary Education (10–12 years old; third cycle), Secondary Education (12–16 years old) and Baccalaureate (17–18 years old) students of the Region of Valencia (Spain): (1) the main information channels through which students receive information on climate change; (2) the causes and consequences of this phenomenon that are identified by the students and whether these involve differences between these three educational levels; and (3) the main greenhouse gas that students believe is present in the atmosphere. With respect to the starting hypothesis, it was believed that the students would claim to receive information about this phenomenon mainly through audio-visual media (TV, Internet, social networks). Regarding the causes, it was expected that the students would respond that they are related to human action (mainly pollution), while the effects cited by the students were expected be the increase in temperature, sea level, glacier melting, etc. (second hypothesis). In terms of the main greenhouse gas present in the atmosphere, it was expected that the response of the majority of the students would be CO2 (third hypothesis). Significant differences were expected to be found between the three educational stages. The cognitive age of the students, a priori, was expected to influence the answers (fourth hypothesis). For this reason, we would expect the responses of the Baccalaureate students to be more elaborate and self-critical and with fewer errors in their content (for example, in relation to greenhouse gases). This study, therefore, will help to reveal the social attitudes of school children with respect to climate change and whether their understanding coincides with that of their teachers and with the information that is printed in their school textbooks. These latter considerations are addressed in the Discussion section.

4. Discussion

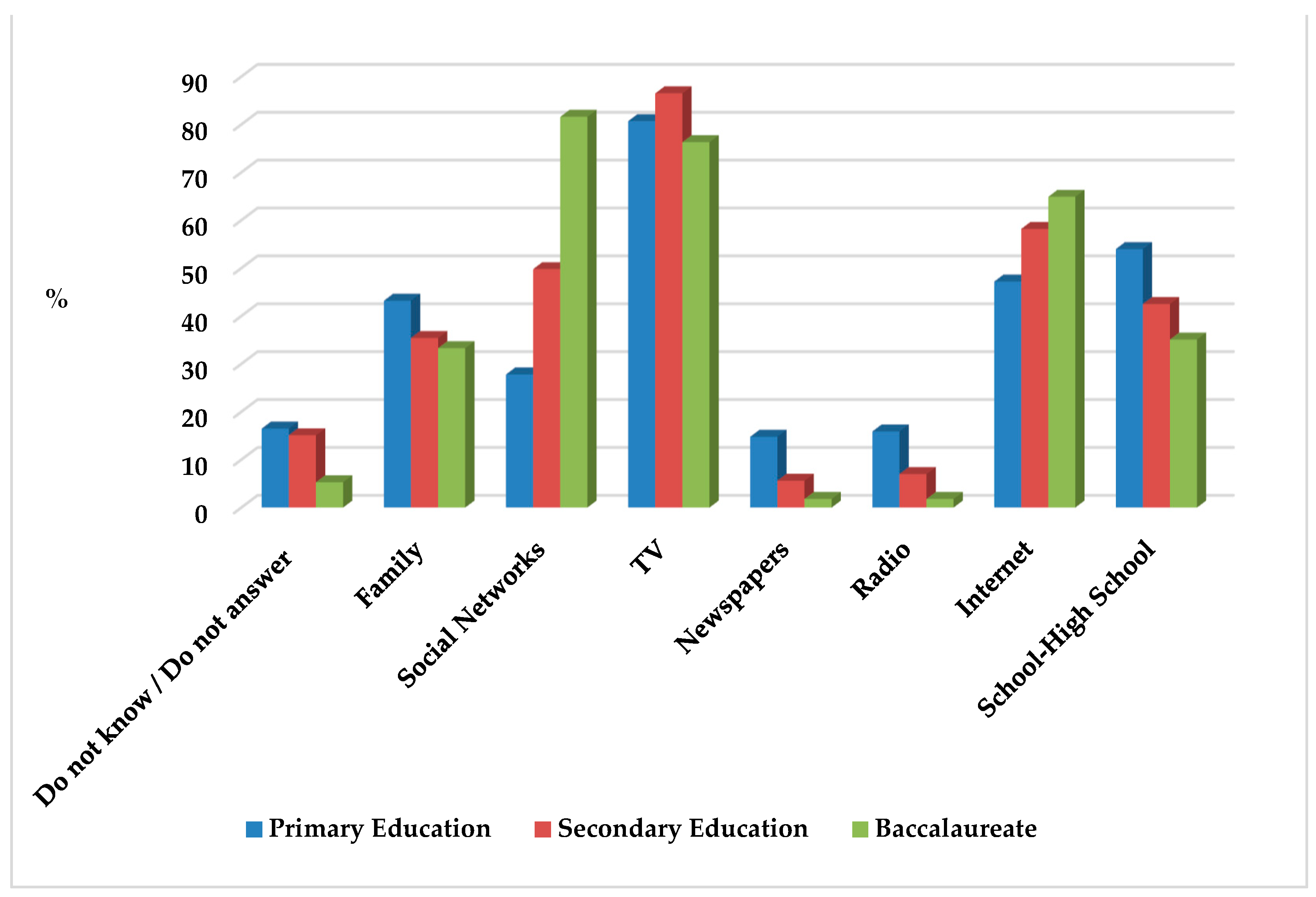

The results obtained in this study highlight the importance that social networks and digital media acquire as the ages of students increase with respect to information on climate change. The first hypothesis established that “students receive information about this phenomenon mainly through audio-visual media (TV, Internet, social networks)”. With respect to the media, this hypothesis was fulfilled. The response regarding “school centre” is only relevant in the Primary Education stage. In this respect, the responses related to school centres decreased from 54.0% in the primary stage to 42.5% in Secondary Sducation and to 35.1% in Baccalaureate. Meanwhile, social networks increased in relevance from 27.8% in Primary Education to 49.8% in Secondary Education and 81.6% in Baccalaureate. A similar trend can be observed for the responses related to the Internet: in Primary Education, it represented 47.2%, as opposed to 64.9% in Baccalaureate. Therefore, as students progress through the educational stages, the school centre loses its relevance and digital media gains in influence (TV, Internet and social networks), which entails risk.

Taking into account these results, we should ask whether the data obtained in this study coincide with the understanding of trainee teachers and the contents of school textbooks (the main resource used in Social Science classrooms) (

Bel et al. 2019). For example, in the study by

Morote (

2020), the data indicated that future Primary Education teachers receive this information mainly from digital media (68.2%), distributed as follows: social networks (28.7%), television (23.1%) and Internet (16.2%). The responses related to academic studies (university training) accounted for only 13.4%. Furthermore, according to

Morote et al. (

2021a), 86.2% of the information about climate change received by Primary Education trainee teachers is derived from the media. In another study on Secondary Education and Baccalaureate teachers (comparing University of Valencia, UV and Murcia, UMU, Spain), the percentages of information received from digital media were 67.7% (UV) and 54.2% (UMU) (

Morote and Moreno 2021). Furthermore, in Chile (University of Concepción), a predominance of the media (52.0%) was found in the social attitudes of students in three different academic fields (science and mathematics, biology and social education) (

Parra et al. 2013).

Therefore, the training of future teachers is based on digital media, which leads to a low level of development in generic and transversal competencies in these topics, as acknowledged by

Parra et al. (

2013). Other authors also indicate the risk that could ensue if the majority of this information is drawn from media, characterised by the consumption of untruthful information that sometimes lacks scientific rigour and is overly sensationalist (

Allen et al. 2018;

Brisman 2018;

Kažys 2018;

Lutzke et al. 2021).

Morote (

2020) explains that the media also provide truthful information, although the majority report information that lacks rigour in order to attract audiences, using false news and/or apocalyptic headlines. This author has also researched the perceptions of this type of news by trainee teachers. The results reveal that 56.2% agree that this type of news has a manipulative objective and/or presents false information: “highly agree” (25.3%) and “agree” (30.9%). However, there is a high percentage of participants who are “indifferent” to this type of news (29.5%). Other studies have also found that the training of active teachers is deficient. A study carried out by

Gallego and Castro (

2020) among university lecturers (Colombia) to identify the understanding acquired in the teacher training process regarding climate change reveals that there are gaps in this training. Specifically, trainee teachers have a vague idea about the scientific model of climate change and their preparation in this area is the fruit of the popularisation of the topic, which, in many cases, is obtained from television programmes and websites. Therefore, they contribute to the transmission of implicit theories of climate change and, moreover, conceptual errors which, due to their role as teachers, will be transmitted to the future generations.

This deficient training may lead teachers to use school textbooks excessively (

Morote and Souto 2020). This has been confirmed in subjects characterised by activities based on memorisation and the reproduction of content at a low cognitive level, as in the case of Geography (

Kidman 2018). Furthermore, this teaching resource also lacks scientific rigour (

Morote and Olcina 2020). This could mean that this topic is not taught in the classroom or is taught very loosely (

Olcina 2017). In relation to climate change, the most common mistakes include the almost complete absence of discussion of the human influence (vulnerability) when referring, for example, to natural hazards (

Morote and Olcina 2020). This is fundamental, as acknowledged in different reports on the effects of climate change (

IPCC 2022), since it is necessary to address the vulnerability factor to adapt to this phenomenon (

EEA 2017).

The second hypothesis (causes: “it is expected that the students will respond that they are related to human action –mainly pollution –”; consequences: “would be the increase in temperature, sea level, glacier melting, etc.”), was confirmed. The results revealed that the phenomenon of climate change is seen by students as an issue of “pollution” and an “increase in temperatures”. Furthermore, we observed that these responses became more important as the children grew older. This may have been due to the greater influence of digital information media (Internet, social networks, and TV) as the age of the students increased. In these media, there is a predominance of news identifying pollution as the cause and the increase in temperature as the effect.

Different studies carried out from the social attitudes of trainee teachers generated results similar to those of this study. For the case of Secondary Education teachers,

Morote and Moreno (

2021) indicate that the causes identified are human action (pollution, deforestation, and overexploitation of resources) and that the consequences are related to catastrophic effects (natural disasters). A similar result was obtained by

Escoz-Roldan et al. (

2020), who analysed the social attitudes of undergraduate students with respect to the risk of climate change and its relationship with water in three Spanish cities. In total, 85.0% of the respondents believed that climate change was “mainly due to human causes”. Furthermore, the study conducted in two secondary schools in the United Kingdom by

Kurup et al. (

2021) revealed a strong understanding of the causes and effects of global warming. This was corroborated, in turn, by

Chang and Pascua (

2016) for Asia, who found that students’ understanding of the causes of climate change was limited to the belief that the recorded changes are solely due to anthropogenic reasons. Gaps in training in terms of content can also be observed in students’ difficulty in establishing relationships between the different elements and processes that intervene in the climate change process beyond associating them with processes that they consider to be “good” or “bad”. In other words, they also lack the specific vocabulary to explain these processes. Furthermore,

Wu and Otsuka (

2021) found that, based on a sample of 657 Secondary Education students in Shanghai (China), erroneous concepts and a biased comprehension of climate change persist. The authors highlight the need to expand climate literacy and education from a conceptual and geographical perspective. If we compare this study with other works, the students always maintain the same discourse pattern: the greenhouse effect is harmful for society, it is caused by human action and global warming has disastrous effects (

Da Silva and Boveloni 2009).

These gaps are associated both with the sources from which the information is obtained (the media) and the school textbooks, in which there is a predominance of catastrophic messages and, often, images taken out of context (

Morote and Olcina 2020). Although this lack of scientific rigour is the dominant feature, it should also be noted that publications are emerging that address the current process of climate change simply and rigorously. An example is the study by

Nelles and Serrer (

2020) which, with abundant and clear graphic material, explains the different elements that comprise this complex process affecting the entire environment (the earth’s climate, climate change, oceans, extreme events, ecosystems and human beings).

Scharmacher-Schreiber and Stephanie (

2020), using a question–answer method (is the climate becoming warmer and warmer? Can a difference of one degree be felt?), have elaborated materials on climate change directed at basic educational levels.

Furthermore, in the training on natural risks as effects of climate change, it is important to focus on how these processes are perceived by children. As indicated by

Zhong et al. (

2021), in a study on disaster education and its impact on children’s perceptions of flooding in China, this enables us to explore its impact effectiveness and pathways. In turn, this furthers knowledge of the management of the consequences (effects) of climate change. In other words, it is important to know the effects of climate change and, using this knowledge, to implement actions aimed at managing these risks and to learn how society adapts through education, based on social representations and the perceptions of students.

The third hypothesis was also confirmed: with respect to the main greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, “it is expected that the response of the majority of the students will be CO

2”. The results generated from analysing the sources from which the children obtained their information on climate change or their causes and consequences were reiterated.

Chang and Pascua (

2016), through semi-structured interviews with secondary students from Singapore, found “that the students’ knowledge of climate change is composed of incomplete and incorrect elements” (p. 84). This was corroborated by analysing the role played by gases in the greenhouse effect. For example, the students considered that CFCs are the major greenhouse gases (19.7%); 6.6% even believed that “climate change is linked with tectonic activities (tsunami, earthquakes)”. Both of these assertions are incorrect. In the first case, this was because water vapour was not taken into account; there were even students who did not consider it as an element that affects climate change. Furthermore, an even more serious mistake was relating geological processes with atmospheric processes, as

Olcina (

2017) has observed in Secondary Education textbooks.

This conceptual confusion coincides with the results obtained in this study, where water vapour was an “unknown” element for the respondents. These results are similar to those obtained from analysing the contents of textbooks. For example, the aforementioned study by

Morote and Olcina (

2020) confirms that only three out of every ten books refer to water vapour as a greenhouse gas. However, none of the textbooks indicate that it is the principal greenhouse gas in the atmosphere. Nevertheless, this fact, as expressed by the authors, is not completely negative, as 33.3% of textbooks at least mention it. Moreover, it should be explained that CO

2 is the main greenhouse gas that is increasing due to anthropic reasons (0.04%), but its presence in the atmosphere continues to be much lower than that of water vapour (4.0%).

The fourth hypothesis established that “significant differences are expected to be found between the three educational stages. The cognitive age of the students, a priori, should influence the answers. For this reason, we would expect the responses of the Baccalaureate students to be more elaborate, self-critical and with less error in their content (for example, in relation to the greenhouse gases)”. This was partially confirmed. We can confirm that as the age of the students increased, the number of errors related to their responses on greenhouse gases also rose. In the case of the Baccalaureate stage, none of the students responded correctly. Again, the influence of the media could be the cause of this error.

Teaching the topic of climate change based on a holistic and integrated approach would constitute an opportunity to promote critical thought in society and among citizens. Only in this way will the current and future society be able to interpret its surrounding territory. In this respect, we can refer to the initiative in the United Kingdom that has recently incorporated teachers specialising in climate change into primary and secondary education centres (

Ecoinventos 2019). Furthermore, it is also worth highlighting case study analyses that examine studies on natural risks (

Aspin 2018), such as global warming (

Greenwood 2018), carried out for several decades by the Geographical Association (United Kingdom) in Primary Education. The acquisition of the competencies required to face challenges in the future should be one of the objectives of future teachers. This will enable them to understand people’s perspectives, social processes and human–environment interactions and to connect local and global geographical concepts. These concepts include climate change in terms of space, place, scale, physical and human processes, environmental and cultural diversity and interdependence (

Chang and Wi 2018). This would enable future teachers to educate a new generation of critical thinkers about climate change, supported by a good curriculum (

Kagawa and Selby 2012).

5. Conclusions

The research carried out revealed that school children mainly obtain their information from digital media (TV, Internet, and social networks). One element that is particularly noteworthy is the relevance of schools in these contents: it was found that as the students progressed through the educational stages, the information received from their schools become less relevant compared with information from the media. This is a risk for the critical-thinking training of citizens, due to the need to confirm information and news from false sources, or news that lacks scientific rigour (

Lutzke et al. 2021). Therefore, there is a risk that students take this information to be reliable. Furthermore, it is worth mentioning the work being carried out from the earliest educational stages (particularly primary education) in many schools and the importance given to “family” by these students. However, the relevance of digital media is also significant in very early ages (TV and Internet).

This research goes a step further and, taking into account previous studies, highlights that this knowledge on climate change is shared by trainee teachers and even the content included in school textbooks. Therefore, we are faced with a vicious circle, as the teacher has gaps in his or her training that are passed on to the student who, in turn, will do the same in the future. Taking these training deficiencies and the need to break this vicious circle into account, future research needs to continue using surveys, but also, in particular, to analyse what is really taught in classrooms. The main limitation of this study is that what and how teachers teach climate change in Social Science classes was not analysed. This constitutes a challenge for future research. To achieve this, it is necessary to interview active teachers. In this way, the whole of the educational sphere will be completed, including schools, training at university level and even the resources used in the classroom which, in the case of Social Sciences, continues to be predominant.

As educators, we should underline the importance of raising awareness among the youngest cohort about climate change. Undoubtedly, the education factor is one of the most important pillars for the present and future adaptation to this phenomenon and its associated risks. The accurate communication of climate change to society is a key element in mitigation and adaptation policies and, as argued by

Romero and Olcina (

2021), “the academic world and the public powers must continue transferring the greatest amount of information possible based on proven facts” (p. 329). Therefore, teacher training should be improved with: (1) an explanation of the main issues in climate change, based on information and data provided by different scientific studies and comparing it with, for example, news stories that appear in the media or even the information provided by school textbooks; and (2) the fostering of “IOL” proposals (“Imagination + Originality + Local”) (

Morote and Olcina 2021a). An improvement in training is required as teaching is a huge responsibility. Finally, there is a need, each day, to reinforce concepts that students find difficult to understand. Educators must be committed to implementing methodologies that continuously enhance teaching practices in order to ensure a sound geographical education, generating critically thinking citizens who know how to interpret the environment in which they live.