Exploring UTAUT Model in Mobile 4.5G Service: Moderating Social–Economic Effects of Gender and Awareness

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Problem’s Background

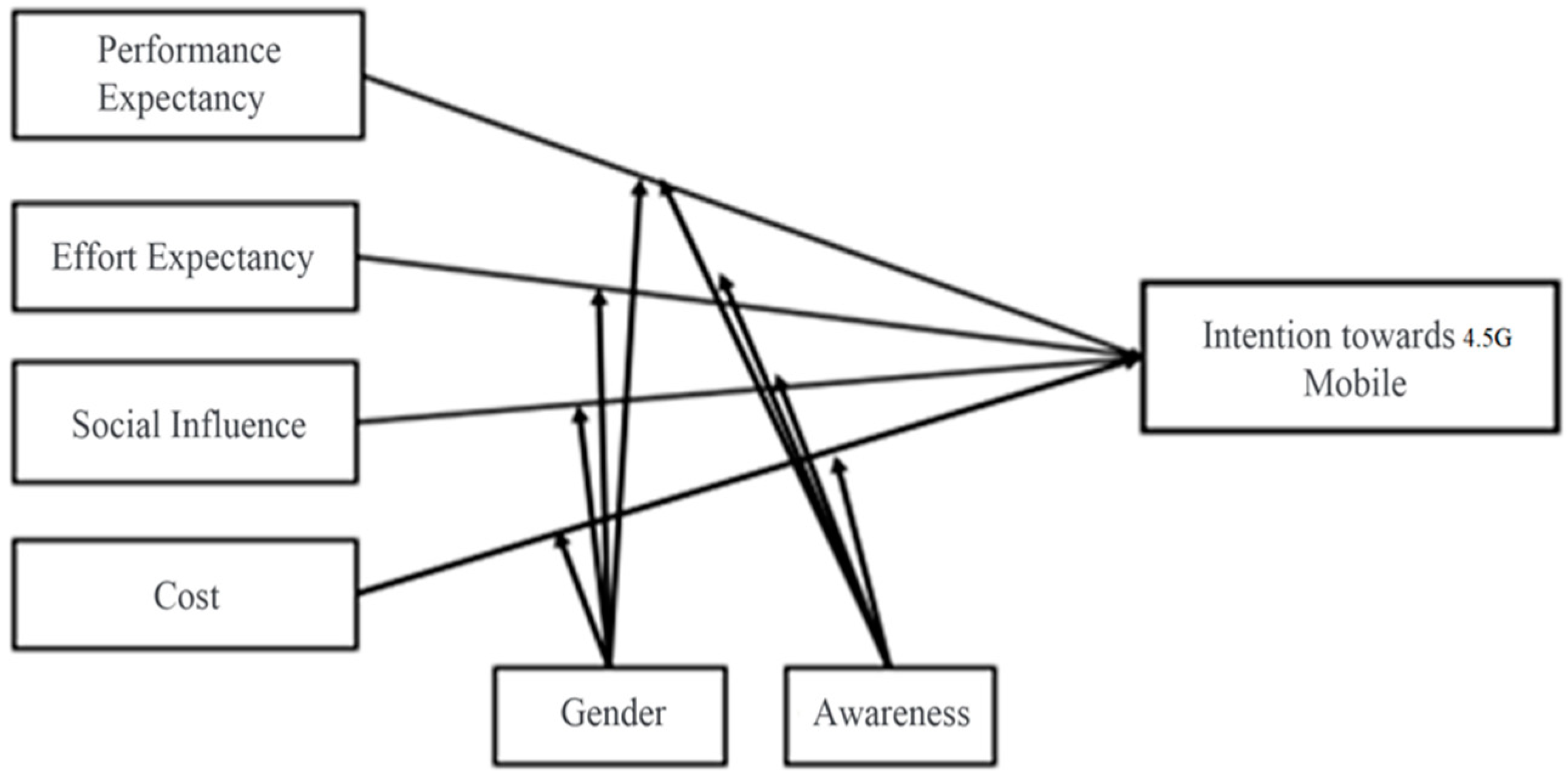

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cost

2.2. Moderating Effects of Awareness and Gender

2.3. Methodology

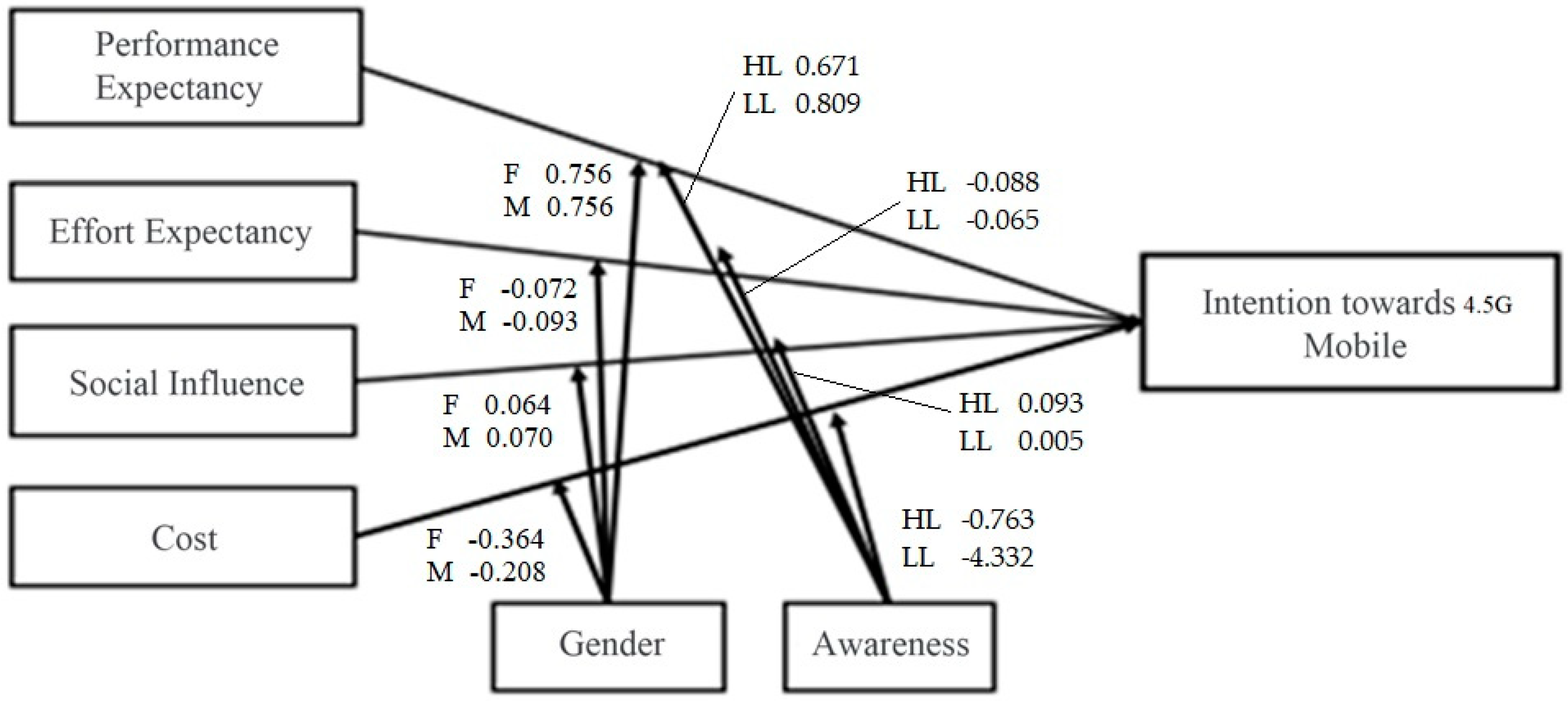

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Implications and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abubakar, Faruq Muhammad, and Hartini B. Ahmad. 2013. The Moderating Effect of Technology Awareness on the Relationship between UTAUT Constructs and Behavioural Intention to Use Technology: A Conceptual Paper. Australian Journal of Business and Management Research 3: 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, Icek, and Martin Fishbein. 1980. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour. Hoboken: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, Icek. 2006. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 32: 665–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dalahmeh, Main, Imran Sarihasan, and Krisztina Dajnoki. 2021. The Influence of Gender and Educational Attainment Differences on International Migrants’ Occupational Status in OECD Countries. Economies 9: 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghazi, Saud S., Amirrudin Kamsin, Mohammed Amin Almaiah, Seng Yue Wong, and Liyana Shuib. 2021. For Sustainable Application of Mobile Learning: An Extended UTAUT Model to Examine the Effect of Technical Factors on the Usage of Mobile Devices as a Learning Tool. Sustainability 13: 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Jaehyung, Alexey Mikhaylov, and Sang-Uk Jung. 2021. A Linear Programming Approach for Robust Network Revenue Management in the Airline Industry. Journal of Air Transport Management 91: 101979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, Izaskun, and Belen Iraizoz. 2020. Effect of the Great Crisis on Sectoral Female Employment in Europe: A Structural Decomposition Analysis. Economies 8: 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barykin, Sergey Yevgenievich, Andrey Aleksandrovich Bochkarev, Evgeny Dobronravin, and Mikhailovich Sergeev. 2021a. The Place and Role of Digital Twin in Supply Chain Management. Academy of Strategic Management Journal 20: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Barykin, Sergey Yevgenievich, Irina Vasilievna Kapustina, Sergey Mikhailovich Sergeev, Olga Vladimirovna Kalinina, Viktoriia Valerievna Vilken, Elena de la Poza, Yuri Yevgenievich Putikhin, and Lydia Vitalievna Volkova. 2021b. Developing the Physical Distribution Digital Twin Model within the Trade Network. Academy of Strategic Management Journal 20: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bigné, Enrique, Carla Ruiz, and Silvia Sanz. 2007. Key Drivers of Mobile Commerce Adoption. An Exploratory Study of Spanish Mobile Users. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 2: 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye, Kwabena G. 2015. Factors Influencing Mobile Data Service (MDS) Continuance Intention: An Empirical Study. Computers in Human Behavior 50: 125–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Chiao Chen. 2013. Library Mobile Applications in University Libraries. Library Hi Tech 31: 478–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Yu Shan, Tsai Fang Yu, Chin Feng Huang, Chien Yu, and Chin Cheh Yu. 2011. The Comparison of Three Major Occupations for User Acceptance of Information Technology: Applying the UTAUT Model. IBusiness 3: 147–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Alain Yee Loong, Felix T.S. Chan, and Keng Boon Ooi. 2012. Predicting Consumer Decisions to Adopt Mobile Commerce: Cross Country Empirical Examination between China and Malaysia. Decision Support Systems 53: 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, Pedro, Lineu Barretto Filgueiras Neto, Pablo Muñoz-Gallego, and Tommi Laukkanen. 2010. Mobile Banking Rollout in Emerging Markets: Evidence from Brazil. Edited by Heikki Karjaluoto. International Journal of Bank Marketing 28: 342–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, Yesodha, NANCY Sebastina, and Srimath Kanchana. 2011. A Study on Customer Awareness, Opinion, Reasons for Opting Mobile Banking. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research 1: 218–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, John Qi, and Xiaoya Zhang. 2011. Gender Differences in Adoption of Information Systems: New Findings from China. Computers in Human Behavior 27: 384–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faqih, Khaled M. S., and Mohammed-Issa Riad Mousa Jaradat. 2015. Assessing the Moderating Effect of Gender Differences and Individualism-Collectivism at Individual-Level on the Adoption of Mobile Commerce Technology: TAM3 Perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 22: 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Yong. 2015. Moderating Effects of Gender in the Acceptance of Mobile SNS Based on UTAUT Model. International Journal of Smart Home 9: 203–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F. 2009. Multivariate Data Analysis. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Li-Hsing, Chang-Liang Hung, and Hui-Chun Chen. 2013. Using Theoretical Models to Examine the Acceptance Behavior of Mobile Phone Messaging to Enhance Parent–Teacher Interactions. Computers & Education 61: 105–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, Syed Far Abid, Mohammad Nurunnabi, Khalid Hussain, and Swapan Kumar Saha. 2019. Effects of Variety-Seeking Intention by Mobile Phone Usage on University Students’ Academic Performance. Cogent Education 6: 1574692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, Bilal, Singha Chaveesuk, and Wornchanok Chaiyasoonthorn. 2021. MOOCs adoption in higher education: A management perspective. Polish Journal of Management Studies 23: 239–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khechine, Hager, Sawsen Lakhal, Daniel Pascot, and Alphonse Bytha. 2014. UTAUT Model for Blended Learning: The Role of Gender and Age in the Intention to Use Webinars. Interdisciplinary Journal of E-Skills and Lifelong Learning 10: 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbrough, Amanda M., Rosanna E. Guadagno, Nicole L. Muscanell, and Janeann Dill. 2013. Gender Differences in Mediated Communication: Women Connect More than Do Men. Computers in Human Behavior 29: 896–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, Rex B. 2015. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Sandeep. 2013. The Role of Moderating Factors of 3G User Acceptance Technology in Shimla. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 64: 53–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, Ying Feng, and Shieh Neng Yen. 2009. Towards an Understanding of the Behavioral Intention to Use 3G Mobile Value-Added Services. Computers in Human Behavior 25: 103–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, Lai-Ying, Keng-Boon Ooi, Alain Yee-Loong Chong, and Binshan Lin. 2013. Modeling the Stimulators of the Behavioral Intention to Use Mobile Entertainment: Does Gender Really Matter? Computers in Human Behavior 29: 2109–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lip-Sam, Thi, and Lim Hock-Eam. 2011. Estimating the Determinants of B2B E-Commerce Adoption among Small & Medium Enterprises. International Journal of Business and Society 12: 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Jun, Ying Liu, Hui Li, Dingjun Li, and Pei-Luen Patrick Rau. 2009. Acceptance of Mobile Entertainment by Chinese Rural People. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 5615: 335–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Nicolás, Carolina, Francisco J. Molina-Castillo, and Harry Bouwman. 2008. An Assessment of Advanced Mobile Services Acceptance: Contributions from TAM and Diffusion Theory Models. Information & Management 45: 359–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megdadi, Younes, and Talal Taher Nusair. 2011. Shopping Consumer Attitudes toward Mobile Marketing: A Case Study among Jordanian User’s. International Journal of Marketing Studies 3: 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhaylov, Alexey Yu. 2021. Development of Friedrich von Hayek’s Theory of Private Money and Economic Implications for Digital Currencies. Terra Economicus 19: 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, Fionn, and André Heck. 2012. Multivariate Data Analysis. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media, vol. 131. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, Nitin, Vikas Nath, and Nancy Goel. 2014. A Study of Adoption Behaviour of Mobile Banking Services by Indian Consumers. International Journal of Research in Engineering & Technology 2: 2347–4599. [Google Scholar]

- Nysveen, Herbjørn, Per E. Pedersen, and Helge Thorbjørnsen. 2005. Intentions to Use Mobile Services: Antecedents and Cross-Service Comparisons. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 33: 330–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, Shintaro, and Felipe Mendez. 2013. Exploring Convenience in Mobile Commerce: Moderating Effects of Gender. Computers in Human Behavior 29: 1234–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, Ala’a. 2011. Determinants of E-Gov Adopt in Kuwait: The Case of the Traffic Violation E-Payment System (TVEPS). Paper presented at the Second Kuwait Conference on e-Services and e-Systems, Kuwait City, Kuwait, April 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna, Rpir, Jmhm Upulwehera, Bdtn Senarath, Gaknj Abeyrathne, Psk Rajapakshe, Jmsb Jayasundara, Ems Ekanayake, and Sisira Kumara Naradda Gamage. 2021. Factors Determining the Competitive Strategic Positions of the SMEs in Asian Developing Nations: Case Study of SMEs in the Agricultural Sector in Sri Lanka. Economies 9: 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, Hernan E, and Rosa E. Rios. 2010. The Moderating Effect of Gender in the Adoption of Mobile Banking. Edited by Heikki Karjaluoto. International Journal of Bank Marketing 28: 328–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Quan, Hao Cao, and Jianxin You. 2010. Factors Influencing the Adoption of Mobile Service in China: An Integration of TAM. Journal of Computers 5: 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velmurugan, Manivannan Senthil, and Masa Sakthi Velmurugan. 2013. Consumers’ Awareness, Perceived Ease of Use toward Information Technology Adoption in 3G Mobile Phones’ Usages in India. Asian Journal of Marketing 8: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Velmurugan, Manivannan Senthil, and Masa Sakthi Velmurugan. 2014. Consumer Behaviour toward Information Technology Adoption on 3G Mobile Phone Usage in India. Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce 19: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, Viswanath, Michael G. Morris, Gordon B. Davis, and Fred D. Davis. 2003. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly 27: 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, Viswanath, and Michael G. Morris. 2000. Why Don’t Men Ever Stop to Ask for Directions? Gender, Social Influence, and Their Role in Technology Acceptance and Usage Behavior. MIS Quarterly 24: 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Calvin, Ronnie Cheung, and Geoffrey Qiping Shen. 2012. Recycling Attitude and Behaviour in University Campus: A Case Study in Hong Kong. Edited by Xiaoling Zhang. Facilities 30: 630–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wereda, Wioletta, and Jacek Woźniak. 2019. Building Relationships with Customer 4.0 in the Era of Marketing 4.0: The Case Study of Innovative Enterprises in Poland. Social Sciences 8: 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Jen Her, and Shu Ching Wang. 2005. What Drives Mobile Commerce? An Empirical Evaluation of the Revised Technology Acceptance Model. Information and Management 42: 719–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadykin, Vladimir, Sergey Barykin, Vladimir Badenko, Nikolai Bolshakov, Elena de la Poza, and Alexander Fedotov. 2021. Global Challenges of Digital Transformation of Markets: Collaboration and Digital Assets. Sustainability 13: 10619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Kenneth C. C. 2005. Exploring Factors Affecting the Adoption of Mobile Commerce in Singapore. Telematics and Informatics 22: 257–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqub, Jameelah, Hassan Bello, Idris Adenuga, and Musibao Ogundeji. 2013. The Cashless Policy in Nigeria: Prospects and Challenges. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 3: 200–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yol, Sert, Alexander Serenko, and Ofir Turel. 2006. Moderating Roles of User Demographics in the American Customer Satisfaction Model within the Context of Mobile Services. Paper presented at the 12th Americas Conference on Information Systems, Acapulco, Mexico, August 4–6, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Ming, Martin Dresner, and Robert J. Windle. 2008. Online Reputation Systems: Design and Strategic Practices. Decision Support Systems 44: 785–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NFI | CFI | IFI | TLI | RMSEA | NPAR | CMIN | DF | p | CMIN/DF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.943 | 0.9520 | 0.910 | 0.945 | 0.050 | 91 | 1818.837 | 286 | 0.000 | 6.360 |

| Construct | No Item | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance expectancy | 4 | 0.62 | 0.87 |

| Effort expectancy | 5 | 0.70 | 0.92 |

| Social influence | 5 | 0.58 | 0.87 |

| Cost | 3 | 0.54 | 0.78 |

| Intention | 7 | 0.59 | 0.92 |

| Construct | Effort Expectancy | Social Influence | Cost | Intention | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effort expectancy | 1 | ||||

| Social influence | 0.408 | 1 | |||

| Cost | 0.376 | 0.425 | 1 | ||

| Intention | 0.010 | 0.432 | 0.235 | 1 | |

| Performance expectancy | 0.117 | 0.432 | 0.347 | 0.796 | 1 |

| MODEL | CMIN | DF | CMIN/DF | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | NFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Default model | 1986.074 | 287 | 6.920 | 939 | 0.947 | 0.053 | 0.938 |

| Unstandardized Estimated | SE | CR | Standardized Estimated | p | R2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BI4G | <--- | PE | 0.732 | 0.028 | 26.462 | 0.772 | *** | 0.64 |

| BI4G | <--- | EF | −0.084 | 0.013 | −5.492 | −0.109 | *** | |

| BI4G | <--- | SI | 0.066 | 0.018 | 3.636 | 0.086 | *** | |

| BI4G | <--- | CST | −0.254 | 0.269 | −0.947 | −0.023 | 0.344 |

| Construct | B | Beta | p | CR Differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social influence | ||||

| Female | 0.064 | 0.081 | 0.008 | 2.662 |

| Male | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.013 | 2.471 |

| Performance expectancy | ||||

| Female | 0.756 | 0.765 | *** | 17.925 |

| Male | 0.756 | 0.778 | *** | 17.576 |

| Effort expectancy | ||||

| Female | −0.072 | −0.094 | *** | −3.775 |

| Male | −0.093 | −0.131 | *** | −4.120 |

| Cost | ||||

| Female | −0.364 | −0.019 | 0.578 | −0.556 |

| Male | −0.208 | −0.025 | 0.489 | −0.691 |

| Construct | B | Beta | p | CR for Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social influence | ||||

| High level | 0.093 | 0.13 | *** | 4.175 |

| Low level | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.872 | 0.161 |

| Performance expectancy | ||||

| High level | 0.671 | 0.72 | *** | 17.925 |

| Low level | 0.809 | 0.76 | *** | 16.379 |

| Effort expectancy | ||||

| High level | −0.088 | −0.162 | *** | −5.590 |

| Low level | −0.065 | −0.069 | 0.025 | −2.236 |

| Cost | ||||

| High level | −0.763 | −0.027 | 0.593 | −0.535 |

| Low level | −4.332 | −0.064 | 0.811 | −0.239 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daniali, S.M.; Barykin, S.E.; Zendehdel, M.; Kalinina, O.V.; Kulibanova, V.V.; Teor, T.R.; Ilyina, I.A.; Alekseeva, N.S.; Lisin, A.; Moiseev, N.; et al. Exploring UTAUT Model in Mobile 4.5G Service: Moderating Social–Economic Effects of Gender and Awareness. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11050187

Daniali SM, Barykin SE, Zendehdel M, Kalinina OV, Kulibanova VV, Teor TR, Ilyina IA, Alekseeva NS, Lisin A, Moiseev N, et al. Exploring UTAUT Model in Mobile 4.5G Service: Moderating Social–Economic Effects of Gender and Awareness. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(5):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11050187

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaniali, Sara Mehrab, Sergey Evgenievich Barykin, Marzieh Zendehdel, Olga Vladimirovna Kalinina, Valeriia Vadimovna Kulibanova, Tatiana Robertovna Teor, Irina Anatolyevna Ilyina, Natalia Sergeevna Alekseeva, Anton Lisin, Nikita Moiseev, and et al. 2022. "Exploring UTAUT Model in Mobile 4.5G Service: Moderating Social–Economic Effects of Gender and Awareness" Social Sciences 11, no. 5: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11050187

APA StyleDaniali, S. M., Barykin, S. E., Zendehdel, M., Kalinina, O. V., Kulibanova, V. V., Teor, T. R., Ilyina, I. A., Alekseeva, N. S., Lisin, A., Moiseev, N., & Senjyu, T. (2022). Exploring UTAUT Model in Mobile 4.5G Service: Moderating Social–Economic Effects of Gender and Awareness. Social Sciences, 11(5), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11050187