Building Back Better: Fostering Community Resilient Dynamics beyond COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Case Study Merano

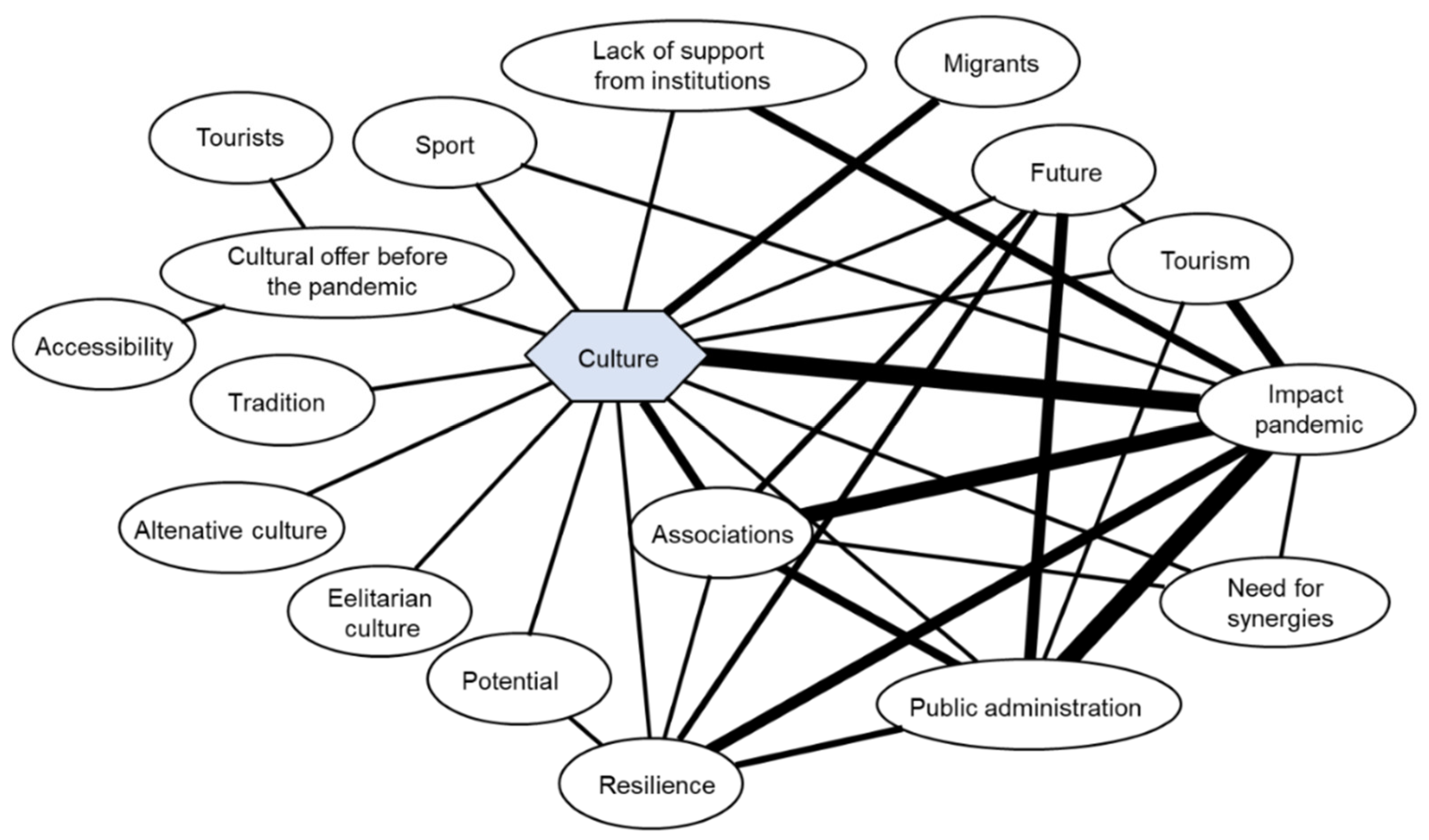

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cultural Dimension

I do believe that resilience can be promoted in certain areas. I believe that cultural work, as we try to implement it concretely in our daily work, can lead a society, people, individuals, and certain groups, to become more open, more liberal, more progressive overall, or even more educated by fundamentally dealing more with social issues.(Interviewee I)

The red carpet is rather laid out for the so-called high culture, […] such as the Merano Music Weeks, the Grape Festival, where […] a relatively folkloristic image of our city, with bands, shooting parades, etc. is shown, while subcultures, etc., have little place, because they are more associated with non-conformity, loudness and possibly drugs and other images.(Interviewee I)

If people don’t take a step towards cultural events, then cultural events have to take a step towards those people […], I hope this will also be a big lesson of this period, to re-evaluate common spaces like squares and parks. […] Let’s say that the world of art and culture is used to having to be flexible, and in my opinion they are the ones who, where it was possible to do something, reacted the best.(Interviewee C)

So now a survey has been carried out, a self-census of artists in South Tyrol, people are participating on a voluntary basis, to create an association that brings together the entire world of South Tyrolean culture. […] The cultural sector is very divided. That is, sculptors mind their own business, writers are another world. There is no union, no representation, at least to talk to the institutions, in order to defend the artist category in the general sense of the term. And so now there is this intent, and certainly there have been collaborations between associations that have helped each other.(Interviewee C)

I would like for the two groups to mix […], while maintaining their own identity. I am not saying that we should water down who we are, but that we should get to know and respect others, and possibly take advantage of the mutual enrichment that contact can bring.(Interviewee C)

3.2. Physical (Health) Dimension

We see more eating disorders, more depressive disorders with suicidal ideation and more social withdrawal and phobic aspects […]. Isolation is a very serious risk factor for mental health, perhaps the most serious.(Interviewee O)

In other words, we have children, families and society weaker than they used to be. Children tend to mature later and slower, but find themselves exposed to the adult world earlier […]. This leads to a weakening of the subject.(Interviewee O)

3.3. Economic Aspects

(There is) a strong drive towards the future, and a commitment to move forward and keep developing, which many people here possess, perhaps also because Merano is a tourist town, […] always accustomed to adapting and carrying on […], so the people have a lot of drive and enthusiasm.(Interviewee N)

3.4. Social Aspects

We have seen many associations become active and reinventing themselves. For example, some young people have been strongly and actively involved in food collection, home delivery, etc.(Interviewee D)

On an individual level, (should a future crisis arise) we should protect even the weakest people. The older, more fragile people. These should be behaviors that we should certainly recall immediately or teach to those who have not experienced this pandemic.(Interviewee H)

Merano lives in a process of continuous change […] due to the arrival of new people, which is a possible stressor and therefore resilience factor […]. (A society) builds resilience if subject to trauma, stress, change […].(Interviewee O)

Merano is predominantly a tourist town. And as to where one reinvests this budget, this opportunity that is created, that opens the issue of thinking about the city’s prospects. Where one decides to invest in terms of schools, culture, and the construction of spaces.(Interviewee O)

3.5. Institutional Dimension

The administrative machine is slow and heavy and should be made more adaptable and faster. It’s a great challenge. Those who find themselves in government have an enormous responsibility but also a wide margin for maneuver. You have tools, such as the government’s Dpcm (i.e., a new ministerial decree), that bypasses Parliament, overriding procedures that would otherwise take weeks, if not months to have results and effects.(Interviewee D)

I really hope that […] we won’t fall back into business as usual as an administration, but we’ll use the lessons we’ve learned from this, the money we’ve freed up, so that it goes towards a good long-term development, and I’m thinking first and foremost about the climate crisis, of course. We need to set priorities and concentrate on this much bigger and important issue. As a community, as an administration, as private individuals.(Interviewee F)

In our society it seems to me that they (i.e., young people and children) don’t have a say and instead they should, because they have the right and they could bring alternative solutions. It would be important and wonderful to involve them more, also in relation to institutions. It is easier to accept (political) choices if they are taken through participatory processes. You have to actually do it, not just on paper, because shared choices are also more defensible. The views of children and young people should never be forgotten in these processes.(Interviewee C)

3.6. Ecological Dimension

In the spring of 2020, there was this lockdown and then in summer you could go outdoors again. Never before have we really felt how important green spaces are and what quality of life they guarantee to the urban population.(Interviewee F)

These access points to the water have a completely different appeal across the generations and for all language groups, for foreign families. This is a point of attraction that transcends all language groups and population groups. Water is a huge magnet.(Interviewee F)

But I don’t see it that way, that we have a sort of mingling. I don’t really see that so much now. It would have to be initiated more.(Interviewee N)

On the one hand we need more green spaces and on the other hand we need high-quality green spaces.(Interviewee N)

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For more information on the relationship between individual and community resilience, see (Berkes and Ross 2013; Shilo et al. 2015). |

| 2 | See for example the annual classical music festival: https://www.meranofestival.com/en (accessed on 23 June 2022). |

| 3 | See for example a self-organized, multicultural no-profit culture club: https://ostwest.it/ (accessed on 23 June 2022). |

| 4 | See for example the artistic initiative “Improvviso”, with performances held in 2020 as presented in a local newspaper: https://www.buongiornosuedtirol.it/2020/07/improvviso-musik-und-theateraktionen-im-stadtzentrum-merans/ (accessed on 14 July 2021) |

| 5 | See local news article from March 2020 on the matter: https://www.rainews.it/tgr/tagesschau/articoli/2020/03/tag-Krankenhaus-Meran-Coronavirus-129abe89-33f8-41dd-a29d-4e164c29a8ba.html (accessed on 15 September 2021). |

| 6 | In South Tyrol, a declaration of linguistic affiliation is carried out by citizens at the age of 18. It serves statistical purposes and fosters the allocation of administrative positions by the respective language group. |

| 7 | See https://www.sdf.bz.it/2020/11/06/anna-bruzzese-ist-die-kommissarin-der-stadt-meran/ (accessed on 14 July 2022). |

| 8 | See for example https://www.suedtirolnews.it/politik/meran-bekommt-europaeischen-stadtbaumpreis-ecot-award-2022 (accessed on 23 June 2022). |

References

- Abdalla, Salma M., Shaffi Fazaludeen Koya, Margaret Jamieson, Monica Verma, Victoria Haldane, Anne-Sophie Jung, Sudhvir Singh, Anders Nordström, Thoraya Obaid, Helena Legido-Quigley, and et al. 2021. Investing in Trust and Community Resilience: Lessons from the Early Months of the First Digital Pandemic. BMJ 375: e067487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aerts, Raf, Naomi Vanlessen, and Olivier Honnay. 2021. Exposure to Green Spaces May Strengthen Resilience and Support Mental Health in the Face of the Covid-19 Pandemic. BMJ 373: n1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostino, Deborah, Michela Arnaboldi, and Antonio Lampis. 2020. Italian State Museums during the COVID-19 Crisis: From Onsite Closure to Online Openness. Museum Management and Curatorship 35: 362–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Farooq, Rashedur Chowdhury, Benjamin Siedler, and Wilson Odek. 2022. Building Community Resilience during COVID-19: Learning from Rural Bangladesh. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonge, Olakunle, Sehwah Sonkarlay, Wilfred Gwaikolo, Christine Fahim, Janice L. Cooper, and David H. Peters. 2019. Understanding the Role of Community Resilience in Addressing the Ebola Virus Disease Epidemic in Liberia: A Qualitative Study (Community Resilience in Liberia). Global Health Action 12: 1662682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTAT. 2020a. COVID-19: Impact on Mortality. ASTAT 66. Available online: https://astat.provincia.bz.it/it/news-pubblicazioni-info.asp?news_action=4&news_article_id=645277 (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- ASTAT. 2020b. COVID-19—Lockdown. ASTAT. Available online: https://astat.provinz.bz.it/de/aktuelles-publikationen-info.asp?news_action=4&news_article_id=641709 (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- ASTAT. 2020c. Population trends. ASTAT 30. Available online: https://astat.provinz.bz.it/de/aktuelles-publikationen-info.asp?news_action=4&news_article_id=640772 (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- ASTAT. 2021. COVID-19: Benessere, Comportamenti e Fiducia Dei Cittadini [COVID-19: Citizens’ Well-Being, Behaviour and Trust]. ASTAT. Available online: https://astat.provincia.bz.it/it/news-pubblicazioni-info.asp?news_action=4&news_article_id=654481 (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- ASTAT. 2022. Statistic Atlas. Available online: https://astat.provincia.bz.it/barometro/upload/statistikatlas/de/atlas.html#!wirt/fnv_fnv/fn_nacht (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Autonomous Province of Bolzano. 2021. Arbeitsmarktbericht Südtirol [Report on the Labor Market in the Province of Bolzano]; Labour Market Observation Office, Autonomous Province of Bolzano. Available online: https://www.provinz.bz.it/arbeit-wirtschaft/arbeit/statistik/arbeitsmarktberichte.asp (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Autonomous Province of Trento. 2020. “Report Indagine ‘Ri-emergere.’” Trentino Famiglia. November 23, 2020. Available online: https://www.trentinofamiglia.it/Documentazione/Pubblicazioni/2.23-Report-Indagine-Ri-emergere (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Barbash, Ian J., and Jeremy M. Kahn. 2021. Fostering Hospital Resilience—Lessons From COVID-19. JAMA 326: 693–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belitski, Maksim, Christina Guenther, Alexander S. Kritikos, and Roy Thurik. 2022. Economic Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Entrepreneurship and Small Businesses. Small Business Economics 58: 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, Fabio, and Kalliu Carvalho Couto. 2021. A Behavioral Perspective on Community Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Paraisópolis in São Paulo, Brazil. Sustainability 13: 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, Fikret, and Helen Ross. 2013. Community Resilience: Toward an Integrated Approach. Society & Natural Resources 26: 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buber, Renate, and Josef Zelger. 2000. GABEK II. Zur Qualitativen Forschung. On Qualitative Research. Innsbruck and Wien: Studienverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, Martin. 2021. The Italian Government Response to COVID-19 and the Making of a Prime Minister. Contemporary Italian Politics 13: 149–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamber of Commerce of Bolzano. 2021. Database. (Data Available on Request). Bolzano: Chamber of Commerce of Bolzano. [Google Scholar]

- Community Resilience Group. 2015. Community Resilience Planning Guide for Buildings and Infrastructure Systems: Volume II. NIST SP 1190v2. Gaithersburg: National Institute of Standards and Technology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, Diana. 2016. Fuzzy Boundaries Between Post-Disaster Phases: The Case of L’Aquila, Italy. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 7: 277–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Crosta, Adolfo, Rocco Palumbo, Daniela Marchetti, Irene Ceccato, Pasquale La Malva, Roberta Maiella, Mario Cipi, Paolo Roma, Nicola Mammarella, Maria Cristina Verrocchio, and et al. 2020. Individual Differences, Economic Stability, and Fear of Contagion as Risk Factors for PTSD Symptoms in the COVID-19 Emergency. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 567367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, Souvik, Payel Biswas, Ritwik Ghosh, Subhankar Chatterjee, Mahua Jana Dubey, Subham Chatterjee, Durjoy Lahiri, and Carl J. Lavie. 2020. Psychosocial Impact of COVID-19. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 14: 779–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, Ciro, Immacolata Di Napoli, Barbara Agueli, Leda Marino, Fortuna Procentese, and Caterina Arcidiacono. 2021. Well-Being and the COVID-19 Pandemic. European Psychologist 26: 285–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurac Research. 2021. Household Survey (Data Available on Request). Bolzano: Eurac Research. [Google Scholar]

- Field, Christopher B., Vicente R. Barros, David Jon Dokken, Katharine J. Mach, Michael D. Mastrandrea, and T. Eren Bilir. 2014. Climate Change 2014—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Regional Aspects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. Part A. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, Carl. 2006. Resilience: The Emergence of a Perspective for Social–Ecological Systems Analyses. 2006. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959378006000379?casa_token=WtCVBjcKkGkAAAAA:QTU_hs8uprnMlRbmcD7Mdzv9SWguiiymKGHPSEoP5-xwdbchk4GxCKv6pmpN4l4gOkQqZSzJmw (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Fransen, Jan, Daniela Ochoa Peralta, Francesca Vanelli, Jurian Edelenbos, and Beatriz Calzada Olvera. 2021. The Emergence of Urban Community Resilience Initiatives During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An International Exploratory Study. The European Journal of Development Research 34: 432–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frick, Ulrich, Miles Tallon, Karina Gotthardt, Matthias Seitz, and Katrin Rakoczy. 2021. Cultural Withdrawal during COVID-19 Lockdown: Impact in a Sample of 828 Artists and Recipients of Highbrow Culture in Germany. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, Nicola, Vivien Ellis, and Stephen Clift. 2019. Cultural Activities Linked to Lower Mortality. BMJ 367: l6774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goroshit, Shaul Kimhi Marina, and Yohanan Eshel. 2013. Demographic Variables as Antecedents of Israeli Community and National Resilience. Journal of Community Psychology 41: 631–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, Emily A., Kathy Black, Tine Buffel, and Jarmin Yeh. 2019. Community Gerontology: A Framework for Research, Policy, and Practice on Communities and Aging. The Gerontologist 59: 803–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnestad, Arve. 2006. Resilience in a Cross-Cultural Perspective: How Resilience Is Generated in Different Cultures. Journal of Intercultural Communication 11: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hynes, William, Benjamin Trump, Patrick Love, and Igor Linkov. 2020. Bouncing Forward: A Resilience Approach to Dealing with COVID-19 and Future Systemic Shocks. Environment Systems and Decisions 40: 174–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isetti, Giulia, Agnieszka Elzbieta Stawinoga, and Harald Pechlaner. 2021. Pastoral Care at the Time of Lockdown. An Exploratory Study of the Catholic Church in South Tyrol (Italy). Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 10: 355–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istat [Italian National Institute of Statistics]. 2022. Database. Available online: https://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=DCIS_POPSTRRES1 (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Jewett, Rae L., Sarah M. Mah, Nicholas Howell, and Mandi M. Larsen. 2021. Social Cohesion and Community Resilience During COVID-19 and Pandemics: A Rapid Scoping Review to Inform the United Nations Research Roadmap for COVID-19 Recovery. International Journal of Health Services 51: 325–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimhi, Shaul, Hadas Marciano, Yohanan Eshel, and Bruria Adini. 2020. Resilience and Demographic Characteristics Predicting Distress during the COVID-19 Crisis. Social Science & Medicine 265: 113389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, Laurence. J., Megha Sehdev, Rob Whitley, Stéphane F. Dandeneau, and Colette Isaac. 2009. Community Resilience: Models, Metaphors and Measures. Journal de La Santé Autochtone 5: 62–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kofler, Ingrid, and Anja Marcher. 2018. Inter-Organizational Networks of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SME) in the Field of Innovation: A Case Study of South Tyrol. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 30: 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliou, Maria, John W. van de Lindt, Therese P. McAllister, Bruce R. Ellingwood, Maria Dillard, and Harvey Cutler. 2020. State of the Research in Community Resilience: Progress and Challenges. Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure 5: 131–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowal, Marta, Tao Coll-Martín, Gözde Ikizer, Jesper Rasmussen, Kristina Eichel, Anna Studzińska, Karolina Koszałkowska, Maciej Karwowski, Arooj Najmussaqib, Daniel Pankowski, and et al. 2020. Who Is the Most Stressed during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Data From 26 Countries and Areas. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 12: 946–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, Wendy, and Cathy O’Mullan. 2016. Perceptions of Community Resilience After Natural Disaster in a Rural Australian Town. Journal of Community Psychology 44: 277–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magis, Kristen. 2010. Community Resilience: An Indicator of Social Sustainability. Society & Natural Resources 23: 401–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, Jenny, Alejandro Lara, and Mauricio Torres. 2018. Community Resilience in Response to the 2010 Tsunami in Chile: The Survival of a Small-Scale Fishing Community. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 33: 376–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2019. Building and Measuring Community Resilience: Actions for Communities and the Gulf Research Program. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, Fran H., Susan P. Stevens, Betty Pfefferbaum, Karen F. Wyche, and Rose L. Pfefferbaum. 2008. Community Resilience as a Metaphor, Theory, Set of Capacities, and Strategy for Disaster Readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology 41: 127–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odriozola-González, Paula, Álvaro Planchuelo-Gómez, María Jesús Irurtia, and Rodrigo de Luis-García. 2020. Psychological Symptoms of the Outbreak of the COVID-19 Confinement in Spain. Journal of Health Psychology 27: 1359105320967086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2020. Culture Shock: COVID-19 and the Cultural and Creative Sectors. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/culture-shock-covid-19-and-the-cultural-and-creative-sectors-08da9e0e/ (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Patel, Sonny S., M. Brooke Rogers, Richard Amlôt, and G. James Rubin. 2017. What Do We Mean by ‘Community Resilience’? A Systematic Literature Review of How It Is Defined in the Literature. PLoS Currents Disasters 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penkler, Michael, Ruth Müller, Martha Kenney, and Mark Hanson. 2020. Back to Normal? Building Community Resilience after COVID-19. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 8: 664–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, Betty J., Dori B. Reissman, Rose L. Pfefferbaum, Richard W. Klomp, and Robin H Gurwitch. 2007. Building Resilience to Mass Trauma Events. In Handbook of Injury and Violence Prevention. New York: Springer, pp. 347–58. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, Stephen. 2018. Factors Affecting the Speed and Quality of Post-Disaster Recovery and Resilience. In Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics in Memory of Ragnar Sigbjörnsson: Selected Topics. Edited by Rajesh Rupakhety and Símon Ólafsson. Geotechnical, Geological and Earthquake Engineering; Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 369–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Province of Bolzano. 2021. Civil Protection Agency. 2021. Available online: https://afbs.provinz.bz.it/upload/coronavirus/Corona.Data.Detail.csv (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Robertson, Tony, Paul Docherty, Fiona Millar, Andy Ruck, and Sandra Engstrom. 2021. Theory and Practice of Building Community Resilience to Extreme Events. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 59: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhanizadeh, Behzad, Sharareh Kermanshachi, and Thahomina Jahan Nipa. 2020. Exploratory Analysis of Barriers to Effective Post-Disaster Recovery. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 50: 101735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Saskia, Maria Ioannou, and Merle Parmak. 2018. Understanding the Three Levels of Resilience: Implications for Countering Extremism. Journal of Community Psychology 46: 669–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghin, Despina, Maria-Magdalena Lupchian, and Daniel Lucheș. 2022. Social Cohesion and Community Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Northern Romania. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, Karl, Stephan Barthel, Johan Colding, Gloria Macassa, and Matteo Giusti. 2020. Urban Nature as a Source of Resilience during Social Distancing Amidst the Coronavirus Pandemic. Available online: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:hig:diva-34273 (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Schmidt, Magdalene, Mauro Tomasi, and Paolo Viskanic. 2020. Der Grünplan von Meran [The Merano Green Plan]. Municipality of Merano. Available online: https://www.gemeinde.meran.bz.it/de/Gruenplan_der_Stadt_Meran_-_Entwurf_des_Endberichtes (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Sharifi, Ayyoob. 2016. A Critical Review of Selected Tools for Assessing Community Resilience—ScienceDirect. Ecological Indicators 69: 629–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shilo, Guy, Nadav Antebi, and Zohar Mor. 2015. Individual and Community Resilience Factors among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Queer and Questioning Youth and Adults in Israel. American Journal of Community Psychology 55: 215–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, Timothy F., Phillip Daffara, Kevin O’Toole, Julie Matthews, Dana C. Thomsen, Sohail Inayatullah, John Fien, and Michelle Graymore. 2011. A Method for Building Community Resilience to Climate Change in Emerging Coastal Cities. Futures, Alternative City Futures 43: 673–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sou, Gemma. 2019. Sustainable Resilience? Disaster Recovery and the Marginalization of Sociocultural Needs and Concerns. Progress in Development Studies 19: 144–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, Jane Jude Stansfield, Richard Amlôt, and Dale Weston. 2020. Sustaining and Strengthening Community Resilience throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond. Perspectives in Public Health 140: 305–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiernan, Anne, Lex Drennan, Johanna Nalau, Esther Onyango, Lochlan Morrissey, and Brendan Mackey. 2019. A Review of Themes in Disaster Resilience Literature and International Practice since 2012. Policy Design and Practice 2: 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubadji, Annie. 2021. Culture and Mental Health Resilience in Times of COVID-19. Journal of Population Economics 34: 1219–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNISDR. 2015. Proposed Updated Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction: A Technical Review. Available online: http://www.preventionweb.net/files/45462_backgoundpaperonterminologyaugust20.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Xu, Wenping, Lingli Xiang, David Proverbs, and Shu Xiong. 2021. The Influence of COVID-19 on Community Disaster Resilience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Robert K. 1994. Case Study Research. Design and Methods, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Yip, Wanfen, Lixia Ge, Andy Hau Yan Ho, Bee Hoon Heng, and Woan Shin Tan. 2021. Building Community Resilience beyond COVID-19: The Singapore Way. The Lancet Regional Health—Western Pacific 7: 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelger, Josef. 2000. Twelve Steps of GABEK WinRelan. In GABEK II Zur Qualitativen Forschung. Innsbruck-Wien: Studien Verlag, pp. 205–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zelger, Josef. 2019. Erforschung und Entwicklung von Communities: Handbuch zur Qualitativen Textanalyse und Wissensorganisation mit GABEK® [Researching and Developing Communities: Handbook for Qualitative Text Analysis and Knowledge Organisation with GABEK®]. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelger, Josef, and Andreas Oberprantacher. 2002. Processing of Verbal Data and Knowledge Representation by GABEK®-WinRelan®. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 3: 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Definition | Key Informants’ Expertise |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural | The cultural fabric of the city and its diversity, fruition of arts and engagement in cultural activities before and during the disaster (Tubadji 2021). | Representatives of the cultural sector (theater, music, arts, literature). |

| Physical | Healthcare delivery during the pandemic; quality of care for physical and mental health with a particular focus on how hospitals and retirement homes weathered the pandemic waves (Barbash and Kahn 2021; Yip et al. 2021). | Public healthcare staff representatives (hospitals and retirement homes). |

| Economic | The economic fabric of the city, the direct and indirect costs of the disaster and the future outlook on the economic development (Belitski et al. 2022). | Local economic representatives in Merano (shopholders, entrepreneurs, public facilitators). |

| Social | Social networks among groups and individuals within the community. This also includes political engagement, volunteerism, feeling of belonging before and during the disaster (Jewett et al. 2021; Saghin et al. 2022; South et al. 2020) | Leaders and activists of volunteer groups and associations. |

| Institutional | Trust in political and religious institutions, health services, and media, and their (perceived) ability to provide assistance to citizens in the emergency (Abdalla et al. 2021; Esposito et al. 2021; Saghin et al. 2022). | Representatives of local institutions and media. |

| Ecological | Perception and use (or lack thereof) of green spaces—parks and promenades—before and during the disaster (Aerts et al. 2021). | Responsible persons for green spaces in the city. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Isetti, G.; Ghirardello, L.; Walder, M. Building Back Better: Fostering Community Resilient Dynamics beyond COVID-19. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 397. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11090397

Isetti G, Ghirardello L, Walder M. Building Back Better: Fostering Community Resilient Dynamics beyond COVID-19. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(9):397. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11090397

Chicago/Turabian StyleIsetti, Giulia, Linda Ghirardello, and Maximilian Walder. 2022. "Building Back Better: Fostering Community Resilient Dynamics beyond COVID-19" Social Sciences 11, no. 9: 397. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11090397

APA StyleIsetti, G., Ghirardello, L., & Walder, M. (2022). Building Back Better: Fostering Community Resilient Dynamics beyond COVID-19. Social Sciences, 11(9), 397. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11090397