Determinants of the Self-Efficacy of Prospective Teachers in Using Drama Activities for Kindergarten: A Sample from the Arab Region

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What are the perceptions of prospective kindergarten teachers regarding their ability to manage and execute drama activities?

- Is there a relationship between prospective teachers’ attitudes toward the teaching profession, communication skills, and self-efficacy in using drama activities for kindergarten?

- What are the risks of using drama activities for kindergarten children in Jordan as perceived by prospective teachers?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. The Multi-Dimensional Self-Efficacy Belief Scale (Tezer et al. 2019)

2.2.2. The Attitude toward Teaching Profession Scale (Ustuner 2006)

2.2.3. The Communication Skills Inventory (Ersanli and Balci 1998)

2.3. Translation

2.4. Participants

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Reports on Study Variables

3.2. Determinants of Self-Efficacy

3.3. Perceived Risks of Using Drama Activities for Kindergarten Children in Jordan

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Implications

Implications in Light of COVID-19

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aksoy, Pinar. 2019. Drama in preschool education from theoretical processes to practice examples in preschool education. In Theory and Practice in Social Sciences. Sofia: St. Kliment Ohridski University Press, p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Akyol, Tugce, Deniz Kahriman-Pamuk, and Ridvan Elmas. 2018. Drama in Education for Sustainable Development: Preservice Preschool Teachers on Stage. Journal of Education and Learning 7: 102–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alkhateeb, Haitham. 2013. Attitudes towards teaching profession of education students in Qatar. Innovative Teaching 2: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khayat, Amjad. 2019. Using Drama in Education: Exploring the Views of Social Sciences Teachers in Salt Directorate of Education. Dirasat: Human and Social Sciences 46: 575–89. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khayat, Amjad, and Ramzi Haroun. 2017. The efficiency of a training program based on dramatic activities in the development of social skills among students of drama and theatre in education course. Dirasat, Educational Sciences 47: 20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khayat, Amjad, Ayoub Al Khatib, and Amal Al-Rousan. 2022. Attitudes towards Teaching Profession among Prospective Kindergarten Teachers in Jordan: Association with Communication Skills, Self-Esteem, and Interest in Teaching. Curriculum and Teaching. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khayat, Amjad, Raed Al-Kreimeen, and Majed Al-Khayat. 2013. Preferred learning styles in kindergarten students by the viewpoint of their mothers’ and teachers’. Journal of Education and Practice 4: 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Arac, Ismet. 2018. Communication skills of students in fine arts departments of education faculties. Educational Research and Reviews 13: 688–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, Albert. 1977. Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, Albert. 1995. Self-Efficacy in Changing Societies. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, Albert. 2002. Social Cognitive Theory in Cultural Context. Applied Psychology: An International Review 51: 269–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, Afaf. 2022. The effects of digital drama-based instruction on developing receptive and expressive language among kindergarten children. International Journal of Instruction 16: 103–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassok, Daphna, Scott Latham, and Anna Rorem. 2016. Is kindergarten the new first grade? AERA Open 1: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhargava, Anupama, and Moak Pathy. 2014. Attitude of student teachers towards teaching profession. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education 15: 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Citak Tunc, Gulseren, and Hilal Yavas. 2022. The impact of using creative drama in the delivery of Body Safety Training Programs for preschool children on preventing sexual abuse in Turkey. Psychology in the Schools 59: 915–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadandı, İbrahim, Ayşe Kalyon, and Hikmet Yazıcı. 2016. Teacher self-efficacy beliefs, concerns and attitudes towards teaching profession of faculty of education and pedagogical formation students. Bayburt Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi 11: 253–69. [Google Scholar]

- Eliöz, Murat. 2016. Communication Skills and Learning in Impaired Individuals. Universal Journal of Educational Research 4: 2589–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eren, Emil. 2006. Organizational Behaviour and Management Psychology. Istanbul: Beta Publishing Distribution. [Google Scholar]

- Ersanli, Karakoyun, and Sim Balci. 1998. Developing a communication skills Inventory. Turkish Psychological Counseling and Guidance Journal 2: 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, Shaundawna. 2021. Effects of faculty and staff connectedness on student self-efficacy. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 21: 58–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güleç, Selma, and Burcu Macan. 2014. The effects of drama-supported cooperative learning method on the development of pre-school children’s communication skills. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 136: 532–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, Rais, and Yuyun Elizabeth Patras. 2022. Improving Teacher Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) through Servant Leadership, Justice and Self-efficacy: Indonesian Teacher Perspective. Pedagonal: Jurnal Ilmiah Pendidikan 6: 180–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, Jessica A., and Edward A. Miller. 2020. Addressing the consequences of school closure due to COVID-19 on children’s physical and mental well-being. World Medical & Health Policy 12: 300–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, Anna, Ping-Kuen Cheung, Simon Wong, and Mavis He. 2011. How effective is a drama-enhanced curriculum doing to increase the creativity of preschool children and their teachers. The Journal of Drama and Theatre Education in Asia 2: 21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kanadlı, Sedat. 2017. Prospective teachers’ professional self-efficacy beliefs in terms of their perceived autonomy support and attitudes towards the teaching profession: A mixed methods study. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice 17: 1847–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, Ken, and Scott Maxwell. 2003. Sample size for multiple regression: Obtaining regression coefficients that are accurate, not simply significant. Psychological Methods 8: 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Komarraju, Meera, Sergey Musulkin, and Gargi Bhattacharya. 2010. Role of student–faculty interactions in developing college students’ academic self-concept, motivation, and achievement. Journal of College Student Development 51: 332–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Parul, Neha Kumar, and Hiram Ting. 2021. An impact of content delivery, equity, support and self-efficacy on student’s learning during the COVID-19. Current Psychology, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehtonen, Anna, Eva Österlind, and Tuija Viirret. 2020. Drama in education for sustainability: Becoming connected through embodiment. International Journal of Education & the Arts 21: 19. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Hao, Yunhuo Cui, and Ming Ming Chiu. 2018. The relationship between teacher support and students’ academic emotions: A meta analysis. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marín Murcia, José Pedro, and María José Martínez Ruiz-Funes. 2020. Froebel and the teaching of botany: The garden in the Kindergarten Model School of Madrid. Paedagogica Historica 56: 200–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill-Franzen, Anne. 2006. Kindergarten Literacy: Matching Assessment and Instruction. New York: Scholastic. [Google Scholar]

- Namdar, Oguz, and Ozgur Salih Kaya. 2019. Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Perceptions and Attitudes towards Using Creative Drama. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi (H. U. Journal of Education) 34: 901–14. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, Peter, and Mermúdez Estellés. 2021. Shot of love: The art of care in schools post disaster. Pastoral Care in Education 39: 209–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, Huseyin, Mehmet Dalli, Erkan Bingol, Sabri Can Metin, and Duygu Yarali. 2014. Examining the relationship between the communication skills and self-efficacy levels of physical education teacher candidates. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 152: 440–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perren, Sonja, Sandra Herrmann, Irina Iljuschin, Doris Frei, Carolin Körner, and Fabio Sticca. 2017. Child-centred educational practice in different early education settings: Associations with professionals’ attitudes, self-efficacy, and professional background. Early Childhood Research 38: 137–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quacquarelli Symonds. 2020. The Impact of the Coronavirus on Global Higher Education. Available online: http://info.qs.com/rs/335-VIN-535/images/The-Impact-of-the-Coronavirus-on-GlobalHigher-Education.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Schunk, Dale. 2014. The Theory of Learning: An Educational View. Ankara: Nobel. [Google Scholar]

- Tezci, Erdoga, and Ali Rıza Terzi. 2010. An examination on the attitudes towards teaching profession of the students of secondary school branch teacher training programs. e-Journal of New World Sciences Academy 5: 367–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tezer, Murat, Sebnem Guldal Kan, and Cizem Bas. 2019. Determination of Multi-Dimensional Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Prospective Teachers towards Creative Drama Activities. International Journal of Instruction 12: 783–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tok, Sukran. 2011. Pre-service primary education teachers’ changing attitudes towards teaching: A longitudinal study. European Journal of Teacher Education 34: 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombak, Aysem. 2014. Importance of drama in pre-school education. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 143: 372–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tschannen-Moran, Megan, and Anita Woolfolk Hoy. 2001. Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education 17: 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umuzdaş, Serpil, Akanda Doğan, and Mehmet Serkan Umuzdaş. 2019. Impact of Musical Creative Drama Education on Self-Confidence of Preschool Children. Journal of Education and Training Studies 7: 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ustuner, Murat. 2006. Reliability and validity of the Attitude Scale Towards Teaching Profession. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice 12: 109–27. [Google Scholar]

- Viner, Russell M., Simon J. Russell, Helen Croker, Jessica Packer, Joseph Ward, Claire Stansfield, Oliver Mytton, Chris Bonell, and Robert Booy. 2020. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: A rapid systematic review. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 4: 397–404. [Google Scholar]

- Walag, Angelo Mark, Maria Teresa Mabaylan Fajardo, Prosibeth Bacarrisas, and Faith Guimary. 2022. A canonical correlation analysis of Filipino science teachers’ scientific literacy and science teaching efficacy. International Journal of Instruction 15: 249–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, Kristin, Claudia Leeger-Aschmann, Nico Monn, Thomas Radtke, Loura Ott, Cornelia Rebholz, and Susi Kriemler. 2017. Interventions to promote fundamental movement skills in childcare and kindergarten: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine 47: 2045–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2005. Process of Translation and Adaptation of Instruments. Available online: https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/ (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Yasar, Münevver Can, and Neriman Aral. 2012. Drama education on the creative thinking skills of 61–72 months old pre-school children. US-China Education Review 6: 568–77. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, Isa. 2021. A Study on the Effect of Instructors’ Communication Skills on the Professional Attitudes and Self-Efficacy of Student Teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching: International Research and Pedagogy 47: 605–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, Müge. 2020. Training program for gaining cultural elements with drama and art activities: My culture, my identity. Marmara Üniversitesi Atatürk Eğitim Fakültesi Eğitim Bilimleri Dergisi 52: 505–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale/Subscale | (M ± SD) | Q1 | Median | Q3 | Data Range | Possible Range | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

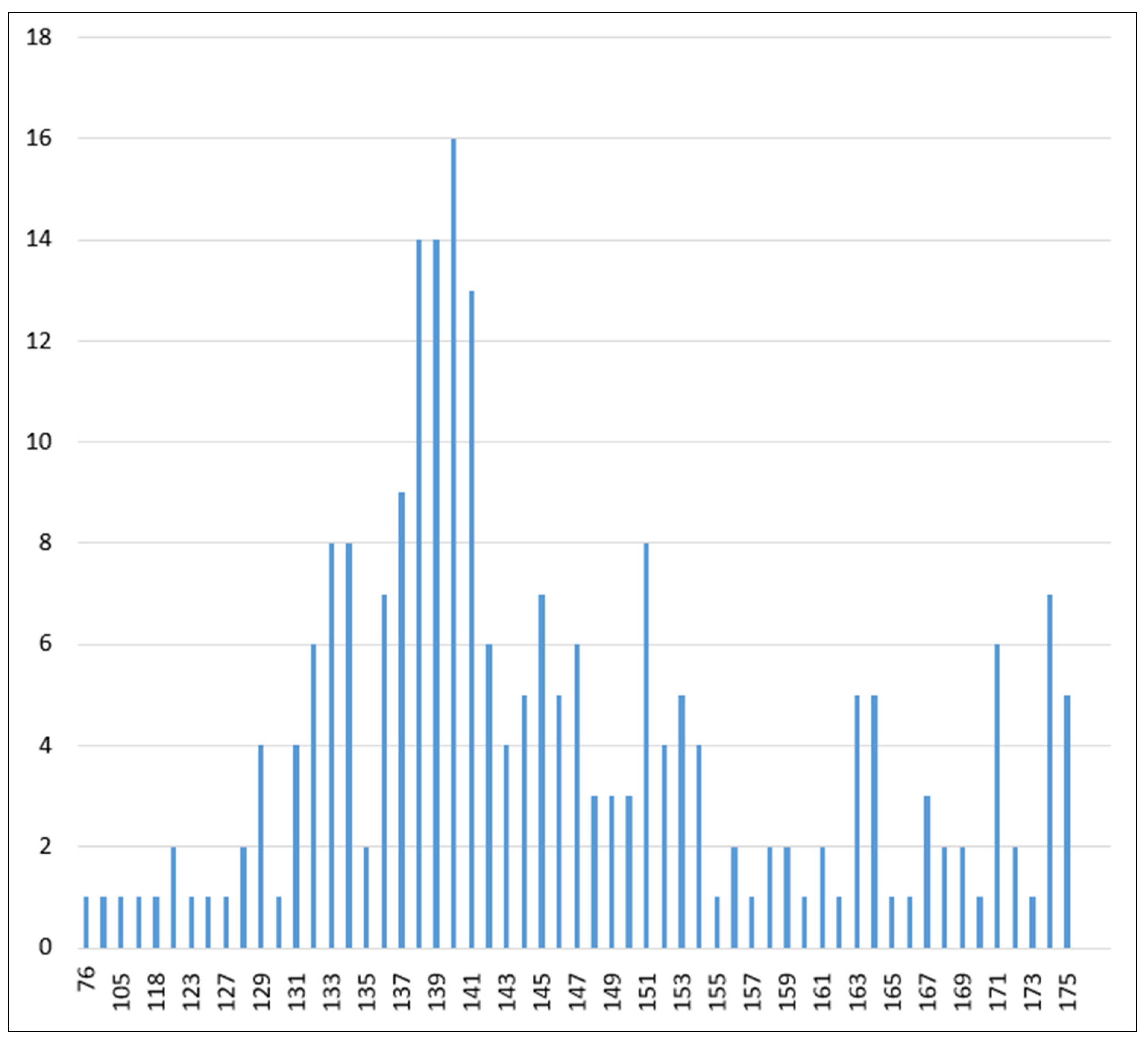

| The Multi-Dimensional Self-Efficacy Belief Scale | 145.47 ± 14.75 | 137 | 141 | 153 | 76–175 | 35–175 | 0.956 |

| Classroom management and communication | 63.18 ± 6.51 | 59 | 61.5 | 68 | 35–75 | 15–75 | 0.912 |

| Learning–teaching process and evaluation | 57.14 ± 6.44 | 54 | 56 | 60 | 26–70 | 14–70 | 0.900 |

| Planning | 25.14 ± 2.91 | 23.75 | 24 | 27.25 | 14–30 | 6–30 | 0.857 |

| The Attitude Toward the Teaching Profession Scale | 130.43 ± 14.35 | 123 | 131 | 141 | 64–170 | 34–170 | 0.893 |

| Communication Skills Inventory | 170.87 ± 16.78 | 161 | 170 | 179 | 125–225 | 45–225 | 0.855 |

| Variable | B | SE | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High school track | 0.098 | 0.610 | 1.731 | 0.085 |

| Years of study | 0.037 | 1.050 | 0.622 | 0.534 |

| GPA | −0.111 | 1.069 | 1.954 | 0.052 |

| Drama training | −0.055 | 1.774 | −0.912 | 0.363 |

| Attitudes toward teaching | 0.396 | 0.062 | 6.515 | 0.000 |

| Communication skills | 0.213 | 0.053 | 3.543 | 0.000 |

| R2 = 0.299 | F for change in R2 = 16.109 | DF = (6, 227) | p < 0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Khayat, A.; Abdulhaq, B. Determinants of the Self-Efficacy of Prospective Teachers in Using Drama Activities for Kindergarten: A Sample from the Arab Region. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12010043

Al-Khayat A, Abdulhaq B. Determinants of the Self-Efficacy of Prospective Teachers in Using Drama Activities for Kindergarten: A Sample from the Arab Region. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Khayat, Amjad, and Bayan Abdulhaq. 2023. "Determinants of the Self-Efficacy of Prospective Teachers in Using Drama Activities for Kindergarten: A Sample from the Arab Region" Social Sciences 12, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12010043

APA StyleAl-Khayat, A., & Abdulhaq, B. (2023). Determinants of the Self-Efficacy of Prospective Teachers in Using Drama Activities for Kindergarten: A Sample from the Arab Region. Social Sciences, 12(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12010043