Abstract

(1) Background: Chinese citizens using entertainment education (EE) strategies on social media have played a pivotal role in responding to the COVID-19 crisis, especially when facing insufficient government support. Thus, this research aims to study the adoption of EE strategies on social media by Chinese citizens and its affordance for crisis responses. (2) Methods: We implemented a qualitative case study by analyzing the vlog series Wuhan Diary 2020 on Sina Weibo to examine the characteristics of the EE strategies used by Chinese citizens, with special attention to citizen participation. (3) Results: The initial phases of the lockdown saw substantial public attention garnered by this approach. The incorporation of solidarity and empathy proved essential for effective communication during the period of crisis response, evident from positive audience feedback and its widespread diffusion. However, a decrease in attention concurrent with the end of the lockdown has also been noticed. (4) Conclusions: The social value and affordance of EE strategies employed by citizens in the short term was confirmed. However, the decline of attention in the post-crisis period indicates the uncertainty of the long-term impact of this approach. This phenomenon also underscores the ambivalence of social media due to the limitations imposed by digital capitalism.

1. Introduction

The immense crisis in all dimensions generated by the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted human society in many ways, ranging from the everyday life of each individual to each country and the global community (Fuchs 2021). Prevention protocols, such as the lockdowns during the first wave, resulted in the intensive use of social media (Tsao et al. 2021; Wong et al. 2021), which formed an essential part of communicative practices during this period. Meanwhile, for the same reason, excessive information on social media, mixing both helpful information and disinformation, has led to the perplexing situation of an infodemic (Wang and Marí 2021; Yusha’u and Servaes 2021), which renders it urgent that more effort be made towards finding efficient solutions to communicate with people.

In an urgent situation, the participation of citizens, such as those in the voluntary sector (Thiery et al. 2021), is also crucial. As Díaz-Bordenave (1981, p. 18) states, it is not only necessary to ask how to communicate, but also “what for and what to communicate” in a given context. Related contributions have been evidenced in previous studies, which signals the possibilities for this sector as part of the civil emergency-response system for aid (Lai et al. 2019; Tang et al. 2021). In this pandemic, the change in the information-acquiring habits of people from legacy media to social media is also critical to bear in mind, which indicates the greater possibility for citizen participation in crisis responses in the digital space. Thus, the objective of this research is to observe the adoption of entertainment content as a form of educational and communicative strategy, as well as the affordance and potential for crisis responses and the improvement of various literacies among the general public as shown by a case study. Specifically, it aims to (a) identify the actions of Chinese citizens on social media in the established geographic area and period; (b) study the characteristics of the aforementioned strategy in their actions; and (c) explore the influence this strategy has on the public and its potential to respond to future crises.

From a theoretical standpoint, this research lies within the framework of health communication, which is a branch of communication for development (Dutta 2008, 2017a, 2017b, pp. 45–59; Kreps et al. 2003; Servaes 2002). Health communication exists within the framework of communication for social change, emphasizing the role of engaged citizens and organizations such as NGOs and social movements. There is great potential for the academic and practical growth of communication for social change in the field of health communication (Kreps et al. 2003; Servaes 2002; Thompson et al. 2011; Marí 2020).

During the early phases of the COVID-19 crisis, when we were confronted with various obstacles with few resources, health communication demonstrated how health inequalities are linked to structural inequality, as outlined in Dutta’s culture-centered approach (CCA) (Dutta 2008, 2017a, 2017b, pp. 45–59; 2020; Kreps et al. 2003). In capitalist societies, communicative inequality is linked to structural inequality, emphasizing the importance of educational initiatives that aim to transform not only individual and group behaviors, but also social norms, institutions, and structures through a cultural lens (Dutta 2004, 2008, 2017a, 2017b, pp. 45–59; Dutta and Jamil 2013), rather than relying solely on technology (Gumucio-Dagron 2001). In this sense, culture refers to the dynamic interaction of common meanings and situations that develop shared values, beliefs, and practices in everyday life. Structures, on the other hand, refer to the patterns of distribution of social, material, political, and economic resources that impact health and well-being (Dutta and Basu 2008; Sastry et al. 2019).

After the onset of the digital age, entertainment education (EE) “as the timeless art of storytelling” (Singhal and Rogers 2012) continues to be used as a tool to increase knowledge, shape or change attitudes, convert personal behaviors, and even shift social norms (Yue et al. 2019) in diverse forms, including posts, podcasts, and short videos. In line with this, we agree with Khalid and Ahmed (2014) that “EE is an amalgamation of design and technique where education is woven into the narrative of entertainment in order to usher in change among the target audiences” (p. 70). In turn, what is sought from the perspective of EE is a directed social change (Khalid and Ahmed 2014; Singhal et al. 2003; Lutkenhaus et al. 2020).

When considering U.S. scholars’ perspective, we focus on social media as a subject traversed in a digital context, and by considering that the cases analyzed come from such platforms, we can delve into more specific analyses. The notion of social change by various authors is intricately related to the need for audience engagement, the change in desired behaviors, and the anticipation of localized effects individually or collectively (Khalid and Ahmed 2014). Additionally, as Singhal et al. (2003) articulate, “EE is the process of purposely designing and implementing a media message to both entertain and educate, in order to increase audience members knowledge about and education issue, create favorable attitudes, shift social norms, and change overt behavior” (p. 5). As illustrated in previous studies, the strategies of EE are characterized by an affective approach, employing media and platforms integrated in their daily routine (Lutkenhaus et al. 2020). In line with this, we mention that the role of influencers can be compared with the figure of the “opinion leader” in relation to the transmission of knowledge and the change in behavior.

According to current research, the present media ecology, which is defined by digitalization and social media, has a strong relationship with the new digital-native generation (Aran-Ramspott et al. 2018). Online educational information, particularly on social media, may be both enjoyable and hilarious, attracting viewers and influencing public perception, particularly among children and teenagers (Onuora et al. 2021). This opens the possibility for EE to adapt to the new digital context during the pandemic through the utilization of diverse communication channels. Furthermore, the use of “transmedia storytelling” (Jenkins 2006) serves as a tool within EE, which seeks to appropriate various platforms in a digital space that allow for the expanding of the universe of new content creation in harmony with the current digital landscape and linguistic diversity. This concept serves us instrumentally when thinking of content creation across different platforms with transmedia, to ensure its educational value. In terms of health education, social media platforms have a considerable effect on health-related behavior in the short and long term (Hunter et al. 2019). This dynamic may be extended to other sectors of education, as exposure to educational information online can have a major influence on others around the user (Fletcher et al. 2011; Latkin and Knowlton 2015; Macdonald-Wallis et al. 2012; Sawka et al. 2013).

In this study, we focus on China’s experience and the contributions of Chinese citizens to the communicative level during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is not only because the pandemic first appeared in Wuhan in December 2019, but also because of what China accomplished in managing the perplexing situation of lockdown during the first wave, when society was experiencing a tremendous social panic with no alternative solutions, such as vaccinations. The subsequent Zero-COVID policy was also covered by Western media like Bloomberg and the Wall Street Journal,1 describing China’s experience with COVID-19 to the world.

Moreover, it is noteworthy that Western perceptions of China often carry a negative connotation, primarily due to the government’s internet censorship and restrictions on free speech among users (Guo 2015; Peng 2005). However, scholars have also emphasized how the internet can empower users regarding democratic participation through the adoption of digital technologies (Hu 2018; Peng 2005). This empowerment is pivotal in portraying a diverse image of China, moving beyond the realm of stereotypes.

Given the rapid advancements in internet technology and the substantial presence of mobile internet users in China, the country’s social media landscape has witnessed exponential growth. This surge in digital connectivity has had a profound impact on both news dissemination and social interaction. Previous research (Chen and Huang 2020; Wang and Marí 2021; Zhang 2021) has highlighted the constructive role that appropriate social media use can play in addressing challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Therefore, further studies of the experiences and practices of Chinese citizens during the COVID-19 crisis hold significance not only for China but also for the global community, particularly in the context of potential future crises of a similar nature.

Based on the research objective of this case study, the questions it explores are:

- (a)

- In the context of China, what is the diffusion tendency of the studied case?

- (b)

- What are the EE initiatives contributed by Chinese citizens and what are the characteristics of the communicative strategy mobilized on social media in the studied case to respond to the COVID-19 crisis?

- (c)

- What is the feedback from the audience to these citizens’ EE initiatives?

2. Materials and Methods

In this research, we implemented a qualitative case study, enabling the possibility of conducting the research in a real context with detailed variations based on an inductive process and a replication logic (Stake 1995; Thomas 2021; Yin 2014).

According to Eisenhardt (1989), case studies give a replicative logic, which is a noteworthy addition of this study approach. Case studies, as pointed out by Snow and Trom (2002), have three key characteristics: (a) the investigation and analysis of a specific instance or variation in a bounded social phenomenon, (b) the generation of a detailed “think” elaboration of the phenomenon under study, and (c) the use and triangulation of multiple methods or procedures, including qualitative techniques, to investigate the phenomenon.

Critical thinking is essential, especially in relation to the idea of “dense descriptions” proposed by anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1973). This method aids in the identification of underlying meanings and conceptual frameworks that frame observations and facts in ethnographic study. Furthermore, the study incorporates digital ethnography (Pink et al. 2016), which highlights a non-technocentric approach and focuses on the social factors present in digital environments rather than merely on the technological tools employed. Following the concepts of researcher Martín-Barbero (1993), this study stresses mediation above media.

In regard to the study object, we selected a series of vlogs named Wuhan Diary 2020 that recorded real life during the lockdown of the city of Wuhan. Accordingly, the period to be studied was defined from the first product in this series in 2020 to the last in 2022, which represents thirty-three episodes in total in the form of vlogs. The vlogs demonstrate many moments of people in Wuhan showing solidarity and support and saving each other after the lockdown was implemented. It was documented by the digital travel creator Lin Wenhua, with the ID “Zhīzhū hóu miànbāo" [sic] on Sina Weibo. This vlog was chosen due to its impact and massive diffusion, as well as the attention this production has drawn from the Chinese official media.

Sina Weibo is a Twitter-like mainstream social media platform in China. We chose Sina Weibo among the Chinese social media platforms, due to (a) its popularity among Chinese citizens, (b) its openness to the public in terms of content access, and (c) its massive use for communication and solidarity actions during the pandemic. Given the complexity and severity of the situation at the time, as well as Wuhan’s status as the initial epicenter of COVID-19, people’s acts of solidarity and participation in the pandemic response though social media platforms were critical, particularly during the city’s lockdown. These actions are valuable not just for the current pandemic, but also for future crises, as an educational tool for social solidarity acts involving citizen engagement in response to a crisis.

This creator had no impact before this pandemic and the first release of this production about the coronavirus and its impact on people, which was followed by over four million and fifty-five thousand users. Due to the impact of his production and his voluntary contributions to the city during the lockdown, he was named one of the “Top 100 Weibo Video Creators of Year 2020”2 by the platform, being seen as an example of a citizen engaging in the fight against COVID-19.

Regarding the analysis process, we first observed the number of views of each episode, in order to record the diffusion tendency of the vlog series and determine which node drew more attention and visibility from the audience. In step two, we studied the content of each episode and extracted the themes addressed in the vlog series. The purpose of this step was to analyze the issues raised by the creator as a common citizen in the first person. In each video, we observed the characteristics of the EE strategy adopted by the creator, which include the narratives, content forms, social-media-post strategy, and social values, in order to explore the affordance of the EE strategy for citizens during the crisis response and the remedying of various information gaps among the general public during the COVID-19 health crisis. Any observation in relation to citizen participation and solidarity communication was given particular attention, which included the opinions of citizens or interactions with and/or between citizens in the video.

In the last step, we examined the feedback from the audience, which included the likes, reposts, and interactions in the comment section. This formed another essential part of the analysis, exploring the affordance of such practices for citizens. Specifically, the comments in the episodes with over one million views were analyzed. The communicative dynamics described above were fundamental to transmitting information and generating massive discourse in the context of COVID-19, since the youth sector of society was able to see deficiencies in the transmission of official information, interpret it, and retransmit it in a more friendly way to sectors that had been excluded from such interpretations (Navarro-Nicoletti and Wang 2022).

3. Results

The discovered findings are articulated in three aspects: the diffusion tendency of the studied case, the characteristics of the communicative strategy, and feedback from the audience.

3.1. Diffusion Tendency

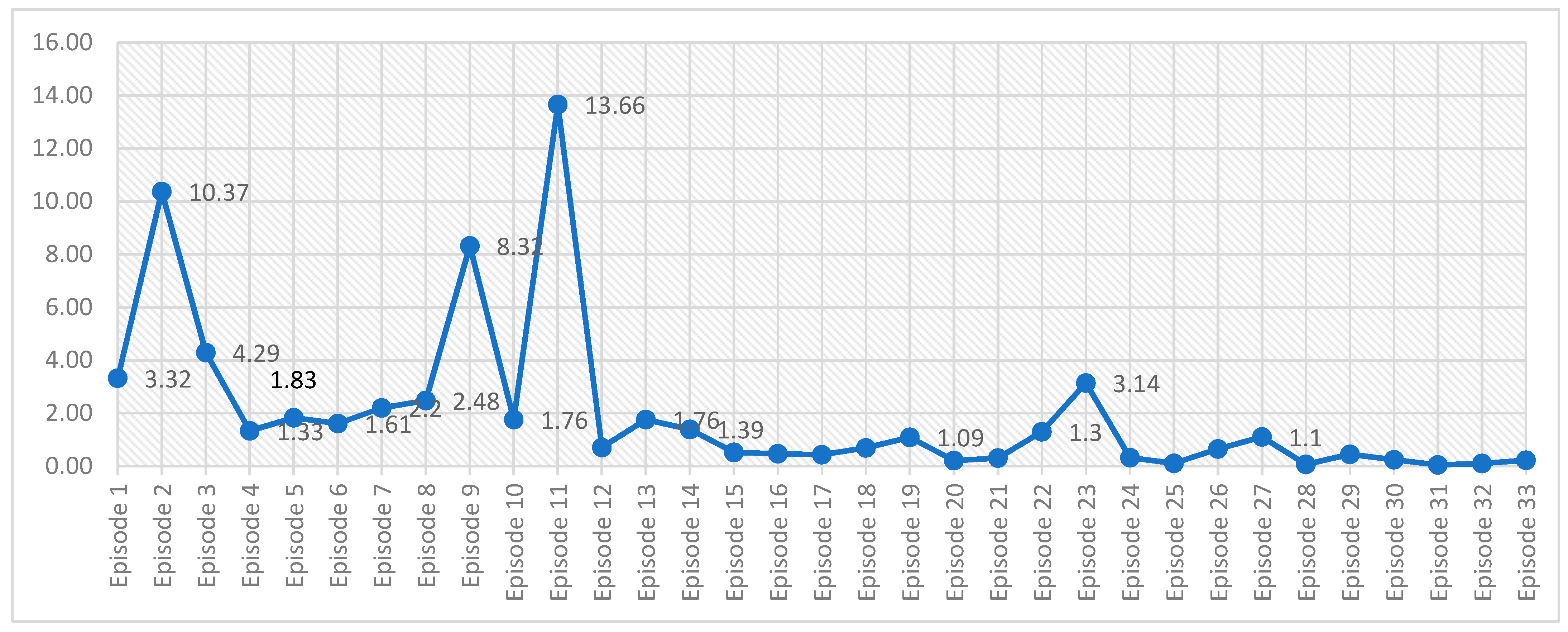

In order to control the further spread of the coronavirus, Wuhan, the “epicenter” of the pandemic at the time, began strict lockdown controls on 23 January 2020. On April 8, Wuhan was reopened when the first wave of COVID-19 in China reached an end. After that, with the popularization of the vaccine, the pandemic prevention and control entered a period of normalization. Due to the repeated epidemics in many places and the high cost of the pandemic control system in the infected areas, the government announced the beginning of a “dynamic Zero-COVID” pandemic-prevention mode. The diffusion tendency of the vlog series is demonstrated in Chart 1 below.

Chart 1.

Diffusion tendency and data of episodes with over one million views.

Among the thirty-three episodes of the vlog series, seventeen of them have been viewed over one million times. Episode (EP) 1 to EP18 were produced during the lockdown during the first wave. As shown in Chart 1, episodes during the lockdown apparently gained much more public attention than the dynamic Zero-COVID phase.

Moreover, during the lockdown phase, a stronger drift in the number of views was observed, along with an unstable and complex situation regarding transmission and changes in the prevention strategy. EP2, EP9, and EP11 are the top three most-viewed episodes, which covered an interview with a medical staff-member helping with her commute (EP2, 10.37 million views), actions and interviews with volunteer organizations from the third sector (EP9 8.32 million views), and the creator himself as medicine-delivery volunteer and what he had witnessed in regard to the deficiency of governance, and the obstacles and conflicts caused by prevention and control policies during the lockdown (EP11, 13.66 million views).

EP2 was produced on the second day of the lockdown, when the public attention was focused on the development of the epidemic. Other than his volunteer action, the creator also mentioned three voices from the public on the internet, which touched on the emotional breakdown of medical staff due to deaths and the lack of medical human resources, a call for aid to all social sectors, and one blaming the Chinese government, which gained 29 thousand reposts and 78 thousand likes, and resonated with viewers, who left 5490 comments.

In EP9, there was also a mother who made a great sacrifice to volunteer logistic and transporting aid, for whom appreciation is given voice directly by the creator in his post, in which he calls her “the most beautiful volunteer mother” while addressing contributions from grassroots citizens. Similar to EP2, her spirit of sacrifice and action received not only emotional resonance but also care from the viewers, with 3036 comments, 3628 reposts, and 33 thousand likes. Among the comments, some viewers posted that they were recommended this vlog by their friend or family overseas, such as in the United States.

In EP11, a girl crying for the loss of her father because of the unreasonable parting and limitation imposed by the prevention protocol communicated her enormous grief to the creator and viewers, which evoked a feeling of heartbreak and empathy for her, appreciation for the sacrifices of medical staff and volunteers, and advocacy for solidarity on a large scale, with calls for love and hope in overcoming COVID-19 among the 13 thousand comments, with 48 thousand reposts, and 113 thousand likes.

When the dynamic Zero-COVID phase was entered, and more normalized prevention measures were adopted along with improved control of the situation based on the enormous sacrifice of the lockdown, the number of views declined sharply, reflecting a steady tendency. A peak is displayed only for EP23, which is a review episode of interviews with two Wuhan citizens, recalling the details of their own experiences of the completed lockdown. This hints at a tendency for public attention to decline after the passing of a crisis, and a possible association between public attention and specific details or moments of the crisis, such the lockdown.

3.2. EE Initiatives by Chinese Citizens and Characteristics of the Communicative Strategy

3.2.1. EE Initiatives by Chinese Citizens

In the vlog series, the creator includes interviews with different social groups. In the interviews featured on the vlog, the two questions that the creator asked the most is “why do you do this?” and “Do not you feel scared?”, in order to directly and objectively demonstrate the public opinion by amplifying their voice and by interacting with diverse social groups without subjective interpretation.

In the studied case, with special focus on the content related to citizen participation, an interpretive content-analysis technique is used for the processing of relevant data from the production (Martín 1955; Piñuel-Raigada 2002). The extracted themes that the creator covered in the whole vlog series are given in the list below, determined after reviewing the content of the videos:

- -

- General information updates, including situations and everyday life, misinformation debunking, city views during the lockdown, and construction of hospitals for receiving affected cases and memorial moments of the COVID-19 victims in Wuhan.

- -

- Exposure of deficiencies in policies, bureaucratic obstacles, and difficulties caused for citizens, and the conflict between citizens and working staff and/or volunteers for these reasons.

- -

- Diffusion and interpretation of policies and health knowledge.

- -

- Solidarity advocacy in action, including solidarity action by citizens and NGOs and the demonstration of workflows, and animal protection.

From the observation of all content and covered in the vlog series, the social groups that were engaged include the following:

- -

- Medical workers.

- -

- Grassroots workers, including delivery workers, hairdressers, trunk drivers, and logistic workers.

- -

- The third sector and volunteers, including local NGOs and ordinary citizen volunteers.

- -

- Expats in Wuhan.

- -

- Experts.

- -

- Marginalized groups in Wuhan, including homeless people, migrant workers from other regions, and vulnerable groups, including COVID-19-affected patients, patients with other diseases, elderly people, and children.

- -

- Home pets and stray animals.

3.2.2. Content Forms and Narratives

The vlog series was published as regular Weibo posts with text content and video material. The text content included the personal comments of the creator and his activity in the corresponding episode. In each episode, the creator tackled different social themes other than his own volunteer action, which was the essential characteristic with social value of the EE strategy in this vlog series, and which will be addressed in more detail in the following section.

Like other content on social media, the studied case also applied hashtags to maximize the visibility of the videos, with the keywords Wuhan, Lockdown, and Cheer up Wuhan: #Wuhan Lockdown# #Wuhan vlog# #Wuhan Diary# #Lockdown Diary# #Wuhan cheer up# [sic]. The use of hashtags not only helps to drive traffic to content and boost views, likes, and shares, but they also function as slogans to enhance the identity of the users in a health crisis and promote solidarity and aid actions among the people.

In relation to the narrative in the studied case, it is not only a work of storytelling from the creator’s subjective perspective of life in lockdown, but also a documentary and dialog with people from all walks of life during this period, used to objectively demonstrate public opinion. The creator also used metaphors to describe the behavior of not wearing masks as “naked running” (EP1), using a sense of humor based in Chinese culture to communicate the risk of such behavior to the audience. The social influence of various digital actors, as in this case, collaborates the theory of EE as providing a more fluent approach to the audience in practice (Lutkenhaus et al. 2020).

In regard to the content form, in this case, the form of a video diary with interviews with people in Wuhan is adopted, to transmit updated information on the situation, personal observations and sentiments, moments of solidarity between people in Wuhan, and points of view of different social groups. An episode of interview audio based on the sharing of real experiences by two Wuhan citizens is also included as a review of the finished lockdown period of Wuhan, with the intention of storing the memory of this period of the COVID-19 pandemic in the form of oral history.

Solidarity, advocacy, and empathy are the main tones of the whole vlog series. The creator sensitized the viewers to actual aid actions from both his own perspective and from other citizens in the video, in order to convey more positive energy and hope to the public in the face of the coronavirus and the social panic and anxiety that came hand-in-hand with it, as aforementioned. For instance, the creator and other citizens continually advocate for solidarity and hope in their volunteer actions, including commuting, providing accommodation, offering a daily care service to medical staff (EP2, 3, 10), providing a medicine and daily supply delivery (EP3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 16, 18) and pet-care aid (EP3), volunteering help to the vulnerable (EP7), hosting memorial events for the COVID-19 victims (EP19, 20), and volunteering support to Wuhan city in the form of music performances (EP29, 31). More positive comments (EP19, 20), such as “tears bursting out” and “appreciation to the contributions from our people”, are found in the comments than contradictory and irrelevant comments, which resonated with the sad, touching, and grateful feelings and emotions the videos carried.

3.2.3. Social Values and Affordance of EE Strategies for Citizens

Based on the summarized social topics and groups that the creator addressed in his personal observations, the social values and affordance for citizens of EE strategies have been observed. To avoid disputes and misleading information, the creator stated in EP7 that the production only represents his personal observations, with the intention of bringing a different perspective and understanding of the covered events, as more and more media outlets engaged in pandemic coverage. In addition, he also committed to being responsible for the authenticity of the facts in his production.

Prevention-policy interpretation, health-knowledge popularization, and misinformation debunking were also important to help guarantee information quality as well as prevent the potential risk of misunderstanding and misinformation during the crisis response. During the lockdown of Wuhan, the creator was one of the volunteers in medicine-delivery teams (EP8, 11). Most of the medicine was Kaletra, an antiviral medicine mentioned in the fourth and fifth editions of the treatment protocol issued by the National Health Commission of China. Communicating with the public through his voluntary actions and explaining complicated medical protocols in simple language are also efficient methods of educating people with different levels of health literacy. The details of aid operations have also been partially recorded in the vlog, which is critical in relation to the transparency of the organization of solidarity by third parties. Such communication contributes to calming the public and to reducing negative emotions such as social panic and anxiety.

Empowerment of Ordinary Citizens

Not only the efforts of medical workers and the third sector, but also those of ordinary people, such as grassroots workers and volunteers (EP2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 18), were given a significant focus, which highlighted the importance of citizen participation in the crisis response during the COVID-19 lockdown.

It is also significant that, in EP18, among the solidarity-aid actions, a donation of female sanitary products to female medical workers was given exposure, which is meaningful as it called public attention to women, who made a contribution equally great as that of men, yet who also have special requirements and the possibility of facing gender inequality in their work.

The importance and function of the third party and citizens’ participation in the crisis response have also been confirmed by volunteers in the vlog. They provided evidence through direct statements in the interviews with the creator. For instance, the supplementary function of the third sector in the government relieves the burden of the public system so it can operate better in crisis responses. This draws our attention to the fact that such a sense of responsibility and solidarity originates by itself. More observations also point to the significance of flexibility and the high efficiency of self-organization in operations during a crisis response, compared to the shortfalls of governmental workflow and bureaucratic procedures.

Visibility and Inclusion of Different Social Groups

Another noticeable finding among the results is that other social groups, like expats (EP14); the vulnerable, such as elderly people and patients (both COVID-19 and non-COVID) (EP6, 7, 18); and marginalized groups (EP15), were specially covered in this vlog series.

In addition to showing the perspective of foreigners who had lived in Wuhan for years on the updated situation of the lockdown, the conditions of their everyday life, and how they felt, the vlog showed expats expressing great support for the prevention policies and appreciation for the care and aid from citizens in Wuhan when interviewed by the creator in the videos. Such action forms a critical way of achieving anti-misinformation and debunking, as well as the importance of the selection of information sources they are diffused.

Coincidentally, one of the expats interviewed in Wuhan is also an expert on animal behavior and welfare at a university in Wuhan. It is significant that she communicated with the general public using her personal experience as one of the residents of Wuhan, instead of as an expert with an official background giving instructions. Adopting a horizontal communicative mode enhances the acceptance of the messages by the general public in a crisis response.

With regard to marginalized groups, it is crucial to deliver information on serious social issues such as social inequality and the digital divide that are intertwined with this pandemic, both at the healthcare level and communicative level, by means of giving them more exposure and attention, as in the studied case. This provides an opportunity for the general public to learn the vulnerable conditions of these “invisible” people; meanwhile, the power of the solidarity of the citizens is mobilized in order to guarantee the basic needs of marginalized groups while they wait for governmental aid due to the low efficiency of the bureaucratic workflow.

Intriguingly, the number of views for this episode is less than 0.5 million, compared to other episodes featuring actions of solidarity and care for other social groups. Furthermore, we found that in the description of the content of this episode, the creator also mentioned that the original EP15 was deleted by Sina Weibo and this post was a second version, with a clearer ending regarding the social topic addressed. Based on this observation, it is suspected that the original episode might have been highly diffused, too. However, due to censorship, it has been deleted, for an unclear reason that could not be discovered. Thus, the second version was not an unknown topic for the audience, and the level of attention and diffusion it gained was low.

Critiques of the Deficiency of Governmental Works

Another observation that cannot be neglected is the critiques of the bureaucracy and the irresponsibility of governmental staff from the perspective of the citizens (EP18), and the conflicts between the citizens and community workers and volunteers because of the prevention policies in place during the lockdown (EP13, 16). For example, one of the interviewees in EP18 strongly questioned the avoidance of duty of some governmental staff who were responsible for issuing travel passes, as they were not willing to bear the risks of possible transmission via any type of transportation. In EP16, a traveler who was on her way back to her home in Wuhan experienced difficulties when she had to communicate with officials when getting off the train and going home, due to the corruption that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic.

China is a typical “relationship” society. In other words, nepotism and connections play an important role. This social character sometimes affects public administrative work and produces obstacles for citizens due to the dereliction of duty of the relevant public servants. In urgent and complex situations such as public health crises, exposure by citizens is crucial in ensuring the supervision of governmental work as one of the necessary functions to maintain the operation of society when such issues arise, and pressures officials to fulfill their duty to the citizens. On the other hand, this helps to dispel rumors if they are not true, and personnel are fulfilling their duty well (EP16). In this sense, social media and EE strategies, such as that employed in this case study, provide a valuable function, by constructing a channel for citizens to expose irresponsible behavior in regard to the supervision of governmental work in the crisis response.

3.3. Feedback from the Audience

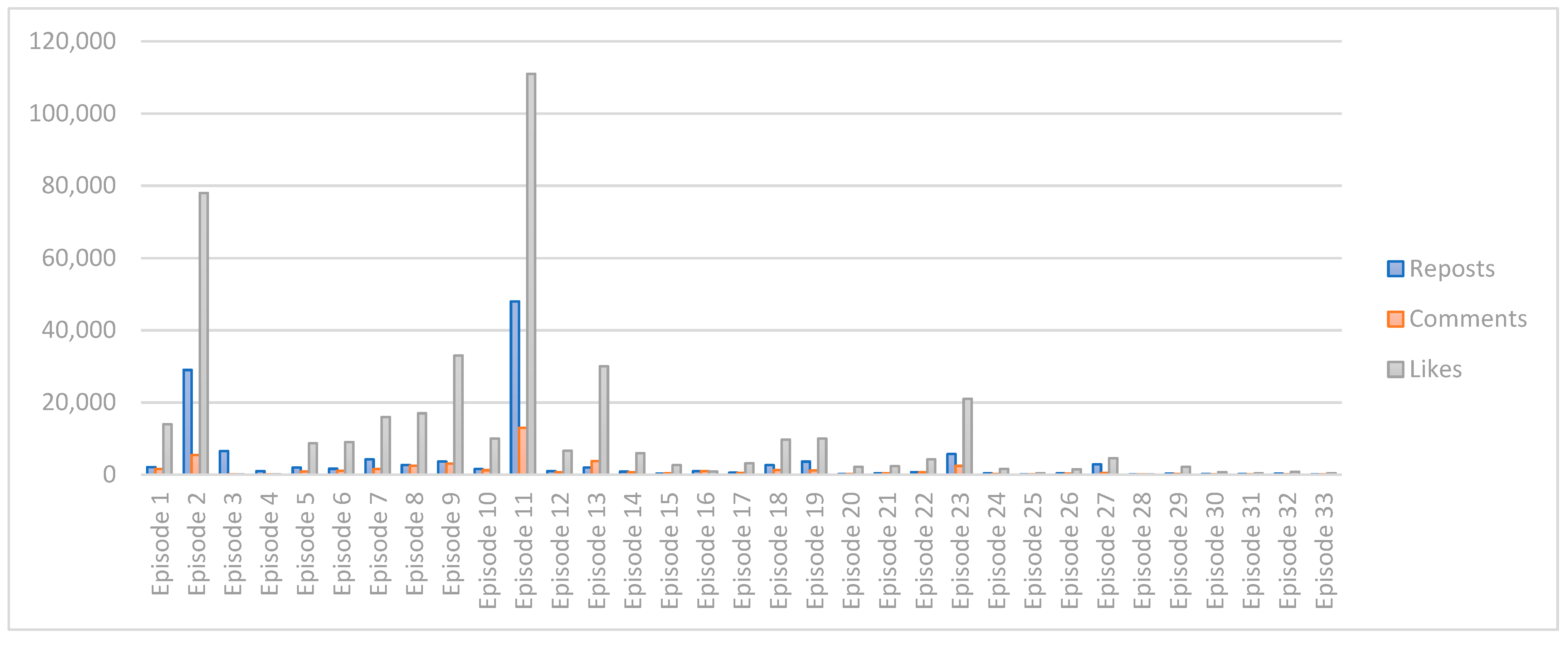

Echoing the diffusion of the vlog, the feedback from the audience indicates a similar tendency. Details of reposts, comments, and likes of each episode are shown in Chart 2 below. For example, because of an interview with frontline medical staff, the second episode gained more than ten times the number of retweets of the first. As we mentioned in Section 3.1, EP11 is the most emotional of the series, according to the creator. This episode produced the most impact and raised the highest engagement among all episodes. Users commented on its wild diffusion at the international level among Chinese nationals residing overseas who use both Chinese and Western social media, which provoked strong emotional resonance and further diffusion.

Chart 2.

Feedback from audience: Reposts, comments, and likes from Weibo users.

Viewers’ obvious affection for the vlogs, the vlog’s reception amongst ordinary people, and solidarity advocacy like the “Cheer up Wuhan” initiative are noticeable in the comments, as well as a confirmation of the effectiveness of the strategy adopted in the case studied. Also noticed in the comments is the active role of grassroots organizations, which emphasizes the importance of citizen participation at the center of the crisis response to this pandemic. In addition to the affection and confirmation of the adopted strategy, an effect with regard to debunking and fact checking misinformation was detected, too. For example, as the following comments selected from the “Hot Comments” area in the posts show:

User 1 25 January 2020 03:36: This kind of moment, video, especially after professional editing of the video, is really a hundred times more powerful than the text. The vloggers act quickly, take out all your aerial camera and car recorder. After you carefully edited the video more effective than the news agency. You are all independent journalists.(EP2)

User 2 31 January 2020 07:29: What be seen the most is the greatness of the “ordinary”.(EP6)

The critique of governmental work and public administration is one of the crucial findings in the comments, echoing the content of the videos. This hints at the great value of citizens empowering themselves though social media and participating in public discussion to apply pressure to authorities, in order to remedy their dereliction of duty and deficiencies. Avoiding censorship by coding sensitive words has also been noticed in comments criticizing the irresponsible attitude and behavior of the government. For example, users adopted the Latin-letter abbreviation “wh” to represent the pronunciation of the possibly sensitive word “Wuhan”, and “zf” for “zhengfu”, which means “government” in Chinese, in the discourse.

User 3: 24 April 2020 07:29 This brings out another aspect of the man-made problem that has been exposed, wh local zf at all levels of warning is not timely, they behave like ostriches with their heads buried in the sand. They did not investigate, adopt, or even condemn the warnings given by Dr. Li Wenliang and others, and then put the blame on a police officer. (EP23).

Nevertheless, the ambivalence of using such an EE strategy on social media has been observed. There are users who suspected the creator of garnering visibility for himself out of self-interest instead of using it for public benefit. The entertaining nature and logic of the “attention economy” generated by the digital capitalism of social media increases visibility, which inevitably turns communication into a utilitarian tool to gain profit and gratify self-interest instead of enabling it to be used as a transformative instrument.

Moreover, we noticed some comments from users suspecting the creator of standing with the official media, while on the other hand worries regarding the malicious intent of the content were also detected. This reveals an intriguing diversity of public opinion on the stance of the official media, international media, and the creator’s media.

User 4 26 January 2020 01:07: Did you take these videos and post them online with the prior consent of the doctors? Why does it look like candid photos? Are you using them for self-selling? The act may look noble, but if the purpose is not pure and the means is not right, it is still wrong! (EP3).

User 5 1 March 2020 20:41: To be honest why do you want to keep attacking the “international media”? There are countless international media, and to be honest the early reports like NYT, CNN have looked at the fact that many patients in Wuhan could not be hospitalized, huh? Traffic paralysis and humanitarian crisis are also a fact, the elder couple walking miles to see a doctor also appeared in your vlogs, which is also a fact. I do not understand how you can still whitewash the situation when you are a first-hand witness. (EP14).

4. Discussion

In a nutshell, the significant public attention and the noticeably positive feedback and engagement from users on Sina Weibo indicates the affordance of this EE strategy for the response to the COVID-19 pandemic crisis and efforts in terms of citizen participation in the beginning of the first Wuhan lockdown, when the situation was complex and emergent and full of social panic and anxiety. Nevertheless, a decline in the attention and engagement of users was observed when the prevention and control measures became normalized during this time. This phenomenon explains, too, why such a strategy serves better in the short term, and that the attention depends on the limit of communication through social media. Namely, the adopted EE strategy—in this case, citizen participation in a crisis response—proved its effectiveness in the short term in light of the urgency of the situation and the public attention in the context of the pandemic. However, the implementation and maintenance of such an approach in the long term during the post-crisis period is yet to be investigated.

As the notion of communication for social change emphasizes, the active role of citizens and their organization is essential to promote social changes at a macro level in regard to the norms, institutions, and structures that regulate social behavior (Wang and Marí 2021). Considering the enormous population base of China and its internet users, as well as the development of digital infrastructures,3 there is great potential for citizens to initiate actions and movements though the internet—such as on Sina Weibo, one of the biggest platforms in China. Sina Weibo has a total of 584 million monthly active users and an average of 253 million daily active users as of September 2022.4 Among the most popular topics in 2022,5 Key Opinion Leaders (KOL) engages a 53.3% share of Sina Weibo users, and News and Society engages 68.07%. In the studied case, the engagement of the creator and users at multiple levels is evidenced. By participating in the discussion, sharing opinions in the comment area, and disseminating the post to their own contacts, a considerable outreach is facilitated (Wang and Marí 2021). Most importantly, such an initiative is appropriated by citizens, instead of those with a background in official parties or institutions. It also helps to reduce the resistance to the political and the institutional impacts for more effective communication in crisis response.

With the concept of CCA (Dutta 2008, 2017b, 2020) borne in mind, structural inequality should be understood as intertwined with health inequality. It even significantly affects health inequality in the case of COVID-19 pandemic. The studied case, produced by a citizen of Wuhan, is undoubtedly a window onto the public recorded with his camera. Through this window, the real living conditions of the people in Wuhan under the impact of COVID-19 can be glimpsed by the public all over the world. This has constructed an important channel for the public to connect and give more attention to marginalized social groups, such as the marginalized groups whose suffering was filmed in EP15, migrant workers who became homeless and had to live in the subway due to the impact of the epidemic and prevention and control policies. Bearing in mind communication for social change (Servaes 2002; Marí 2020), health forms an essential sector of social development (Wang and Marí 2021); it necessitates one to think and act from a more macro level of social norms and structure and shared values, beliefs, and practices in everyday life, rather than staying at the micro level of changes in personal behavior.

The general proposal of EE interventions contributes to a process directed towards social change, which occurs at various levels of society (Khalid and Ahmed 2014). In addition to providing more ways to encourage actions of solidarity, it also functions as a screen that displays the shortages of governmental work and bureaucracy, as well as the tension and conflicts between the aforementioned factors and citizens, which are critical to bear in mind in order to promote social transformation.

A documentary vlog from a diversified and people-centered perspective, covering figures from a local volunteer to the expats in Wuhan, endows such an EE strategy with more flexibility and heightens its efficiency for citizens during a crisis-response period. We would like to give our definition of EE here, considering the diversified forms and styles of user-generated content and the empowered participation of citizens as prosumers in the digital age. We propose that EE is not only the timeless art of storytelling and a technique to change the behaviors of a targeted audience, but also a channel supported by social media platforms that allows everyone to share educational messages in an alternative and dialogic model instead of a unidirectional model or through up–down diffusion.

As shown in the description of EP7, the creator’s original intention in producing this vlog of the lockdown in Wuhan was to convey positive energy and solidarity, as well as eliminate social panic. It can be observed and proved in the feedback from the viewers that he always consciously restrained the emotions conveyed in the videos. The interviewees are very supportive of him, agreeing that the moments and solidarity actions occurring in this tough period are worth being recorded, in order to not forget them. Considering this example, as well as examples of solidarity actions in other episodes, this vlog series is rather serious content for an entertainment platform. Regarding the complex situation during the lockdown, which was full of uncertainty, the studied case contains great value insofar as it communicated with the public and promoted social engagement rather than being entertaining. Numerous comments were observed displaying peer advocacy in following the prevention measures and kind reminders to the creator to protect himself very well with masks and disinfection products. This has other important implications for health communication with citizens playing active roles. Thus, we believe that the proposed dynamic of EE functions well.

Aside from the perspective of transmedia storytelling and alternative education, we also noticed comments expressing that the writers learned about this vlog series from their schoolteachers, as they were required to write reviews of the studied case for writing training. They felt touched after watching it and encouraged Wuhan to stay cheerful and have faith. Based on this detail, there is bright side, too, for the proper adoption of EE strategies to promote diversity in education and help students inform their critical thinking with the social values contained therein.

In addition to recording perspective of ordinary citizens, such an initiative has the power to heal others and empower more people to reach a higher level of participation, which to some extent is where the social value of Wuhan Diary 2020 lies. When individual experiences are intertwined tightly with current events, the “commons” are able to step into the center of the transformative process of society. This also forms another essential part of education for the general public and of social mobilization regarding empathy and sensibilization via citizen participation.

In this sense, the affordance of the EE strategy of citizen participation in a crisis response has been evidenced and confirmed in this case. It is undeniable that everything recorded in this vlog series is only one perspective among many diverse social groups, and does not represent all of the people of Wuhan. However, there is no doubt that such records are encouraged, and need to be seen.

The COVID-19 pandemic has left a profound collective memory in the hearts of people all over the world. In the current information society, the Internet, especially social media, provides the necessary technical support to empower ordinary people to construct their discourse and make their voice heard. Everyone can use their own observations, thoughts, and expressions to tell their own stories through the camera. Although not all people participate, information related to the pandemic was recorded on the Internet and formed the collective memory of each group. In the case of this study, there are many symbols that contribute to this memory of COVID-19, such as the visual impact of the city being empty due to lockdown, the pedestrians in a hurry, the lone delivery persons, the people mourning the death of Dr. Li Wenliang, the medical workers on the front line, the construction moments of the two famous “built-in-ten-days” hospitals, the public Memorial Day for the deceased in the beginning of the pandemic, and the creator’s summary and anniversary review of lockdown life in Wuhan. Therefore, this case study can serve as an inspiration for future academic research and practice in the area of crisis response.

Last but not least, another point that should not be neglected is the ambivalence of adopting such EE strategies on social media, due to the limitations imposed by digital capitalism.

Social media contains the possibility of incubating social movements to promote transformation in the digital space. However, to win visibility for a message in the first place among an ocean of information, it needs to be sufficiently self-presenting. As we can see, based on the diffusion tendency, the visibility was reduced when the situation became milder and less emergent. The public attention declined accordingly. In other words, there is the risk of falling into the trap of an “attention economy”, which is framed in digital capitalism. In the social media ecology, digital capitalism constructs a panopticon and asserts hegemony based on people’s desire to be visible, enticing people with entertainment and emotion. Thus, people voluntarily surrender power and freedom to this hegemony. However, emotion is quick and temporary. Communication turns into a kind of competition for attention. From this perspective, consumerism is a medium and instrument serving people’s desire for visibility and the aforementioned hegemony, rather than a reason for it. Engaging in the consumption of entertainment is effortless, and emotions can be easily provoked. Consequently, people turn to a more utilitarian and fragmented process of communication. That is to say, strategies employed through social media are still trapped in this logic generated by digital capitalism.

Furthermore, as has been pointed out in the description by the creator of the Weibo post EP15, when the exposure of serious social issues affecting the vulnerable encounters censorship from officials in the digital space, what we should do and where we shall be led in the exploration of these digital instruments and means of digital communication remains questions for us to think about.

In regard to the aforementioned notions of EE and communication for social change, the importance of seeking solutions for confronting fake news and improving the literacy of the general public has been pointed out in our observations. For exceptional situations, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, it is logical to think of exceptional solutions. Alternative communication (Simpson-Grinberg 1986), for example, invites us to transcend stereotypes and create or work on more tangible realities and our collective consciousness. However, above all, we are invited to appropriate our own environment, generating, in turn, new narratives and content in various spaces (Jenkins 2006). For example, in the studied case, both the creator and the viewers shared COVID-19-related health messages in the videos or commented in the role of an ordinary citizen, instead of speaking in the voice of an official or expert giving orders to other people, which is very useful in reducing the distance from other users and the resistance to the information compared to that shown to information coming from officials or those with a background of expertise (Wang and Marí 2021). Outside of this case, some science creators on social media employ a similar strategy, and are also worth studying from this perspective. The message sender, instead of lecturing, shares the educational message though a channel or platform of entertainment, in an equal position with the audience but endorsed by professional knowledge, using a humorous narrative or other forms of content so the messages are received more easily and better.

There is a potential for alternative education to benefit from such logic, taking social media as an example, using the transmedia content encountered in everyday life combined with entertainment and attention-drawing methods. Nevertheless, this approach is ambiguous, due to the commercial logic of digital capitalism. We should be aware of what we are dealing with and not fall into the utilitarian trap of data traffic–capital conversion brought about by these practices, which forms another important task both in the academic field of communication research and in the practices of our everyday life as communicators.

In addition, the endorsement of professional knowledge also can be a limit for EE, as this requires either the content generator be equipped with the relevant knowledge or scientific references, or for there to be cooperation between the content generator and professionals. It is not easy for every content generator to manage both the art of storytelling and professional scientific knowledge. Besides this, considering the aforementioned logic of the attention economy, EE also runs the risk of downplaying the rigor of the educational content or misguiding the audience in order to reach attain visibility and attract more attention. Even though EE can be an effective communicative strategy to apply, it should be used thoughtfully in order not to distort facts or present misinformation.

EE should also not be over-relied upon, as this method of attracting can contribute to shortening attention spans and reducing the engagement of users with complex material and systematic deep learning. In such knowledge-sharing strategies as the one studied here from the COVID crisis, viewers can absorb messages quickly, yet stay at a superficial level of knowledge rather than engaging in active learning or systematic deep learning of the specific knowledge. For the same reason, excessive use of entertainment and superficial learning runs the risk of reducing critical thinking, which needs to be formed though an active learning process. Considering the aforementioned limits, we should be careful to use EE appropriately, and more studies are needed to explore its potential and adoption in both communication and education.

5. Conclusions

In this studied case, the contribution of Chinese citizens through social media to the crisis response has been evidenced through the lens of the creator of the analyzed vlog series. Both the different social groups covered by the creator and the use of this content on Sina Weibo have demonstrated a strong sentiment of solidarity and the acknowledgement of actions, such as volunteer aid and operations, as a form of self-organizing.

With reference to the public opinions of different roles among citizens, solidarity actions generated by citizen participation have been emphasized. The affordance of the EE strategy of citizen participation in the crisis response has been confirmed in this case by the feedback of the audience. It is undeniable that everything recorded in this vlog series is only one perspective among many diverse social groups and is not representative of the lives of all people in Wuhan. However, there is no doubt that such records are encouraged, and need to be seen as valuable and educational examples that can help in achieving solidarity and empathy in future crisis responses.

Meanwhile, through the lens of the people, the potential for effective communication with the public and help in combatting disinformation in crises has been observed from the positive feedback and the widespread diffusion. Social media can serve as a channel through which to diffuse content and enable interactions between users and authors related to anti-disinformation, in order to enhance the efficiency of the diffusion of useful messages in a crisis response, while also helping to educate the general public to improve their health literacy.

However, a decrease in attention for the later productions, along with the ending of the lockdown, has also been noticed, which implies the uncertainty of the long-term impact of this approach in contrast to during the development of the pandemic, as the health crisis has gradually been brought under control and become milder in the post-crisis period. It also hints at an ambivalence of social media and digital communication due to the limitations imposed by digital capitalism. Namely, even though the affordance of EE strategies of citizen participation though social media has been proved, the risk of falling into the logic of the attention economy still remains an obstacle to be solved and should be borne in mind. The exploration of such solutions is full of challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W.; methodology, Y.W.; validation, F.N.N.; formal analysis, Y.W.; investigation, Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W.; writing—review and editing, F.N.N.; visualization, Y.W.; supervision, Y.W. and F.N.N.; project administration, Y.W.; funding acquisition, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is carried out in the framework of the research project of the Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI), “Comunicación Solidaria Digital. Análisis de los imaginarios, los discursos y las prácticas comunicativas de las ONGD en el horizonte de la Agenda 2030” (PID2019-106632GB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) IP: Víctor Manuel Marí Sáez.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The transcriptions in English of the interviews in the video content can be referred to the generated English captions of the same videos uploaded by the author to his channel @punkcity110 on Youtube.com. This data can be found here: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLhddqgmqzoy-dlLOfuQYFHhziVgAeohbP (accessed on 18 September 2023). The data of analyzed case are collected from the posts of the video list “Wuhan Lockdown” on the Twitter-like Chinese social media platform Sina Weibo. A link to the Weibo account of the creator can be found here: https://weibo.com/u/1722782045?tabtype=newVideo&first_cursor=4463963360092005&layerid=4463963360092005 (accessed on 18 September 2023). The stored data of the videos with over one million views and their one hundred comments in Hot Comments can be found here: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1nUYbLPFs8aLx2YVkkbNVGwzTjGxt_i9m?usp=sharing (accessed on 18 September 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The news reports can be retrieved in the following links: (a) https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-02-08/what-china-s-covid-zero-policy-means-for-world-supply-chains-and-inflation#xj4y7vzkg (accessed on 18 September 2023). (b) https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-zero-covid-policy-holds-lessons-for-other-nations-11645033130 (accessed on 18 September 2023). |

| 2 | The reference of the nomination can be retrieved in the thank-you post to Sina Weibo of the creator. https://weibo.com/1722782045/Jr6oJ8wIb (accessed on 18 September 2023). |

| 3 | 46th Statistical Report on Internet Development in China. China Internet Network Information Center. https://cnnic.com.cn/IDR/ReportDownloads/202012/P0202012015300234116 (accessed on 18 September 2023). |

| 4 | Weibo Reports Second Quarter 2022 Unaudited Financial Results, data retrieved in Statista. http://ir.weibo.com/news-releases/news-release-details/weibo-reports-second-quarter-2022-unaudited-financial-results (accessed on 18 September 2023). |

| 5 | Popular topics on Weibo in China as of June 2022, data retrieved in Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1326779/china-popular-topics-on-weibo/ (accessed on 18 September 2023). |

References

- Aran-Ramspott, Sue, Maddalena Fedele, and Anna Tarragó. 2018. Funciones sociales de los Youtubers y su influencia en la preadolescencia. Comunicar 57: 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Xiaocenniang, and Yong Huang. 2020. Characteristics and Implications of Cyber Risk Communication during the COVID-19. Journalism Communication 23: 4–6. Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&filename=YWCB202023002 (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Díaz-Bordenave, Juan. 1981. Democratización de la comunicación: Teoría y práctica. Revista latinoamericana de comunicación Chasqui 1: 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, Mohan J. 2004. Poverty, structural barriers, and health: A Santali narrative of health communication. Qualitative Health Research 14: 1107–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, Mohan J. 2008. Communicating Health: A Culture-Centered Approach. Canbridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, Mohan J. 2017a. Migration and Health in the Construction Industry: Culturally Centering Voices of Bangladeshi Workers in Singapore. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14: 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, Mohan J. 2017b. Negotiating health on dirty jobs: Culture-centered constructions of health among migrant construction workers in Singapore. In Culture, Migration, and Health Communication in a Global Context. Edited by Mao Yuping and Ahmed Rukhsana. New York: Routledge, pp. 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, Mohan J. 2020. COVID-19, authoritarian neoliberalism, and precarious migrant work in Singapore: Structural violence and communicative inequality. Frontiers in Communication 5: 560919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, Mohan J., and Ambar Basu. 2008. Meanings of health: Interrogating structure and culture. Health communication 23: 560–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, Mohan J., and Raihan Jamil. 2013. Health at the margins of migration: Culture-centered co-constructions among Bangladeshi immigrants. Health Communication 28: 170–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. 1989. Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review 14: 532–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, Adam, Chris Bonell, and Annik Sorhaindo. 2011. You are what your friends eat: Systematic review of social network analyses of young people’s eating behaviours and body-weight. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 65: 548–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, Christian. 2021. Communicating COVID-19: Everyday Life, Digital Capitalism, and Conspiracy Theories in Pandemic Times. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gumucio-Dagron, Alfonso. 2001. Comunicación para la salud: El reto de la participación. Agujero Negro. Available online: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/38106590/Comunicacion_para_la_Salud__Gumucio_-libre.pdf?1436189727=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DComunicacion_para_la_salud_el_reto_de_la.pdf&Expires=1695432484&Signature=X5-8B0xKXq8-zr98xlDpSXzN (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Guo, Shaohua. 2015. Ruled by attention: A case study of professional digital attention agents at Sina.com and the Chinese blogosphere. International Journal of Cultural Studies 19: 407–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Yong. 2018. Twenty Years of China’s Internet: The Yearning for Freedom, the Call for Trust. Beijing News. October 25, pp. B4–5. Available online: http://huyong.blog.caixin.com/archives/191279 (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Hunter, Ruth F., Kayla de la Haye, Jennifer M. Murray, Jennifer Badham, Thomas W. Valente, Mike Clarke, and Frank Kee. 2019. Social network interventions for health behaviours and outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine 16: e1002890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, Malik, and Aaliya Ahmed. 2014. Entertainment-education media strategies for social change: Opportunities and emerging trends. Review of Journalism and Mass Communication 2: 69–89. Available online: http://rjmcnet.com/journals/rjmc/Vol_2_No_1_June_2014/5.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Kreps, Gary L., Ellen W. Bonaguro, and Jim L. Query Jr. 2003. The history and development of the field of health communication. Russian Journal of Communication 10: 12–20. Available online: http://www.russcomm.ru/eng/rca_biblio/k/kreps.shtml (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Lai, Chih-Hui, Bing She, and Xinyue Ye. 2019. Unpacking the Network Processes and Outcomes of Online and Offline Humanitarian Collaboration. Communication Research 46: 88–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latkin, Carl A., and Amy R. Knowlton. 2015. Social network assessments and interventions for health behavior change: A critical review. Behavioral Medicine 41: 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutkenhaus, Roel, Jeroen Jansz, and Martine Bouman. 2020. Toward spreadable entertainment-education: Leveraging social influence in online networks. Health Promotion International 35: 1241–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald-Wallis, Kyle, Russell Jago, and Jonathan A. Sterne. 2012. Social network analysis of childhood and youth physical activity: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 43: 636–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marí, Víctor M. 2020. Institutionalization and implosion of Communication for Development and Social Change in Spain: A case study. In Handbook of Communication for Development and Social Change. Edited by Servaes Jan. Singapore: Springer, pp. 1311–23. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, Manuel. 1955. El Análisis de contenido en la investigación sobre comunicación. Periodística 8: 67–74. Available online: https://dadun.unav.edu/handle/10171/37522 (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Martín-Barbero, Jesús. 1993. Communication, Culture and Hegemony: From Media to Mediation. Texas: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Nicoletti, Felipe, and Yiheng Wang. 2022. Educación transmedia y Educomunicación/Eduentretenimiento en contexto de pandemia de COVID-19. In Retos y experiencias de la renovación pedagógica y lainnovación en las ciencias sociales. Edited by Carlos S. Rodríguez and Miguel A. Martín López. Madrid: Dykinson S.L., pp. 280–97. [Google Scholar]

- Onuora, Chijioke, Nelson Torti Obasi, Gregory H. Ezeah, and Verlumun C. Gever. 2021. Effect of dramatized health messages: Modelling predictors of the impact of COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons on health behaviour of social media users in Nigeria. International Sociology 36: 124–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Lan. 2005. Convergence and Separation of Power- Internet in Changes. Youth Journalist 3: 17–19. Available online: http://www.cqvip.com/QK/82782X/200503/15153545.html (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Pink, Sarah, Heather Horst, John Postill, Larissa Hjorth, Tania Lewis, and Jo Tacchi. 2016. Digital Ethnography: Principles and Practice. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Piñuel-Raigada, José L. 2002. Epistemología, metodología y técnicas del análisis de contenido. Estudios de Sociolingüística 3: 1–42. Available online: https://www.ucm.es/data/cont/docs/268-2013-07-29-Pinuel_Raigada_AnalisisContenido_2002_EstudiosSociolinguisticaUVigo.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Sastry, Shaunak, Megan Stephenson, Patrick Dillon, and Andrew Carter. 2019. A meta-theoretical systematic review of the culture-centered approach to health communication: Toward a re-fined, “nested” model. Communication Theory 31: 380–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawka, Keri J., Gavin R. McCormack, Alberto Nettel-Aguirre, Penelope Hawe, and Patricia K. Doyle-Baker. 2013. Friendship networks and physical activity and sedentary behavior among youth: A systematized review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 10: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servaes, Jan. 2002. Approaches to Development Communication. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson-Grinberg, Máximo. 1986. Comunicación alternativa y cambio social en América Latina. México: Premia. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal, Arvind, and Everett Rogers. 2012. Entertainment-education: A communication Strategy for Social Change. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal, Arvind, Michael J. Cody, Everett M. Rogers, and Miguel Sabido, eds. 2003. Entertainment-Education and Social Change: History, Research, and Practice, 1st ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, David A., and Darry Trom. 2002. The case study and the study of social movements. In Methods of Social Movement Research. Edited by Bert Klandermans and Suzanne Staggenborg. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, vol. 16, pp. 146–72. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, Robert. E. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Si-yu, Yan-hua Hao, and Xiao-qian Cui. 2021. Participation in volunteer emergency service and its influencing factors during COVID-19 epidemic among the public in China: An online survey. Chinese Journal of Public Health 37: 1113–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiery, Harriet, Joanne Cook, Jon Burchell, Erica Ballantyne, Fiona Walkley, and Jennifer McNeill. 2021. ‘Never more needed ‘yet never more stretched: Reflections on the role of the voluntary sector during the COVID-19 pandemic. Voluntary Sector Review 12: 459–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Garry. 2021. How to Do Your Case Study, 3rd ed. New Delhi: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Teresa L., Roxanne Parrott, and Jon F. Nussbaum, eds. 2011. The Routledge Handbook of Health Communication, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tsao, Shu-Feng, Helen Chen, Therese Tisseverasinghe, Yang Yang, Lianghua Li, and Zahid A. Butt. 2021. What social media told us in the time of COVID-19: A scoping review. The Lancet Digital Health 3: e175–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yiheng, and Víctor M. Marí. 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic in China and the entertainment education as communicative strategy against the misinformation. In Cosmovisión de la comunicación en redes sociales en la era postdigital. Edited by Javier Sierra Sánchez and Almudena Barrientos. Madrid: McGraw-Hill, pp. 675–98. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Adrian, Serene Ho, Olusegun Olusanya, Marta Velia Antonini, and David Lyness. 2021. The use of social media and online communications in times of pandemic COVID-19. Journal of the Intensive Care Society 22: 255–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Robert K. 2014. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Zhiying, Hua Wang, and Arvind Singhal. 2019. Using television drama as entertainment-education to tackle domestic violence in China. Journal of Development Communication 30: 30–44. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11250/2638905 (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Yusha’u, Muhammad J., and Jan Servaes, eds. 2021. Communication for sustainable development in the age of COVID-19. In The Palgrave Handbook of International Communication and Sustainable Development. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Huiling. 2021. El papel irremplazable de los nuevos medios de comunicación de China en respuesta al COVID-19. Historia y Comunicación Social 26: 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).